Worldwide production of whey, a byproduct of the cheese industry, is estimated to be about 180–190 × 106 t/year (Baldasso et al. Reference Baldasso, Barros and Tessaro2011) and the daily production of cheese whey can be up to several million liters by larger cheese plants (Guimaraes et al. Reference Guimaraes, Teixeira and Domingues2010). Cheese whey contains about 50% of the milk solids (whey proteins, inorganic salt, lactose and vitamins) and its proteins are rich in sulfur-containing amino acids (Fox et al. Reference Fox, Guinee, Cogan and Mcsweeney2000). Generally, 80–90 l of whey are generated from 100 l of milk during soft cheese manufacturing. Hence, a cheap method of whey conservation which can impart a significant role in profitability is required.

Pakistan is the 2nd largest buffalo milk producer in the world, however, its transformation into cheese of any kind is limited although increasing (Amir et al. Reference Amir, Moiz and Baig2014). Small quantities of cheese whey are converted into powder but the greater part is currently a waste product. The transformation of the surplus whey into Ricotta cheese would be a useful solution, especially as the use of membranes for the segregation of whey ingredients is expensive.

Ricotta is an Italian type cheese with a soft texture and high moisture (Modler & Emmons, Reference Modler and Emmons2001) grainy and creamy white in appearance (Silvi et al. Reference Silvi, Verdenelli, Orpianesi and Cresci2011). Due to these properties it can be used as an ingredient in cheesecake, pasta, pizza, sandwiches (Del Nobile et al. Reference Del Nobile, Conte, Incoronato and Panza2009), spread, dips, dressing (Cha et al. Reference Cha, Loh and Nellenback2006), dairy fermented beverages (Masson et al. Reference Masson, Rosenthal, Calado, Deliza and Tashima2011), wiped dairy desserts, cream cheese and confectioner fillings (Fox et al. Reference Fox, Guinee, Cogan and Mcsweeney2000; Silvi et al. Reference Silvi, Verdenelli, Orpianesi and Cresci2011).

Traditionally the Ricotta cheese is made from whey produced from ovine, caprine and bovine milk (Mucchetti et al. Reference Mucchetti, Carminati and Pirisi2002) or a mixture of whey and milk in the ratio of 9 : 1. First of all, the pH of whey or mixture is reduced to pH 5·9 to 6·5 (Pizzillo et al. Reference Pizzillo, Claps, Cifuni, Fedele and Rubino2005; Stanciuc et al. Reference Stanciuc, Dumitraşcu, Ardelean and Rapeanu2010) before heating to 85–90 °C for 20 min with food grade acids (lactic, citric) for maximum coagulation of whey proteins (Modler & Emmons, Reference Modler and Emmons2001; Sahul & Das, Reference Sahul and Das2009). The curd produced is placed in the perforated molds and left to drain for 4–6 h at a temperature of 80 °C (Fox et al. Reference Fox, Guinee, Cogan and Mcsweeney2000) before packaging. The temperature, pH, calcium contents and total solids affect the whey protein denaturation during the heating process. The major protein of whey, β-lactoglobulin (β-Lg) precipitates rapidly at high temperature (70–120 °C) at neutral (pH 8) pH, while the α-lactalbumin (α-La) precipitates and aggregates better at pH (3·5–5·5) and lower temperature (50–65 °C). The heat denaturation stability ranges of different milk proteins are in the order α- La > bovine serum albumin (BSA) > Immunoglobulin (Ig) > β- Lg (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Tolkach and Kulozik2006; Fernandez et al. Reference Fernandez, Menendez, Riera and Alvarez2011). The denaturation level of β- Lg is increased by heating in higher concentration of calcium and at high pH values (O'Kennedy & John, Reference O'Kennedy and John2009).

Ricotta cheese is not yet being produced in Pakistan as dairies are not well aware of its processing conditions. Several characteristics of Ricotta cheese have been studied extensively by previous researchers (Pizzillo et al. Reference Pizzillo, Claps, Cifuni, Fedele and Rubino2005; El-sheikh et al. Reference El-Sheikh, Farrag and Zaghloul2010; Stanciuc et al. Reference Stanciuc, Dumitraşcu, Ardelean and Rapeanu2010), but none of them studied the combined effect of pH, temperature and calcium chloride on different characteristics (moisture, fat, protein, NPN, total solids, lactose. ash, pH, acidity) of Ricotta cheese and its yield. Buffalo milk is widely used for fermented milk products (cheese, yogurt), heat desiccated and acid-coagulated products (casein and caseinate), fluid milk supply, dairy whitener and ice cream due to its high solids and casein content and large casein micelle size (Dalmasso et al. Reference Dalmasso, Civera, Neve and Bottero2011). Therefore, the aim of the current research work was to optimize the processing conditions (pH, temperature and calcium chloride) for the higher yield of Ricotta cheese from buffalo whey by using Response Surface Methodology (RSM).

Materials and methods

Procurement of buffalo milk and whey

Buffalo milk was obtained from the dairy farm of University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, Pakistan and Buffalo cheese whey was procured from ‘Nurpur Dairy’, Bhalwal, Pakistan.

Plan of research work

The research work was conducted in two phases.

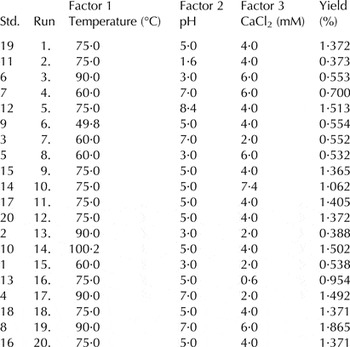

Phase-1: optimization of processing conditions

To determine the effect of heating temperatures 60–90 °C (Honga & Creamer, Reference Honga and Creamer2002; Anema & Li, Reference Anema and Li2003), pH 3–7 (Anema & Li, Reference Anema and Li2003; Bordenave-Juchereau et al. Reference Bordenave-Juchereau, Almeida, Jean-Marie and Frederic2005; O'Kennedy & John, Reference O'Kennedy and John2009) and 2–6 mm concentration of CaCl2 (O'Kennedy & John, Reference O'Kennedy and John2009) on the yield/recovery of milk constituents from whey, Central Composite Design was used to formulate the experiments (Table 1). Firstly the pH of each sample was adjusted using either 0·1 N NaOH or 10% (w/v) citric acid. After that CaCl2 was added and heated to the required temperature without agitation for 20 min. The curd whey mixture was filtered on cheese cloth to drain the whey for 6 h. The recovery of milk constituents, in the form of yield (%) was calculated as:

Table 1. Central Composite Design (CCD) of processing conditions applied on the whey with yield (%) as response

The data obtained from 20 experiments was used to optimize the conditions for maximum yield through response surface methodology (RSM) neglecting the effects with a statistical significance lower than 95% confidence level the RF was related to the factors by using a general quadratic equation (Aktas et al. Reference Aktas, Boyacı, Mutlu and Tanyolac2006):

$$Y = a_0 + \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^n a_i x_i + \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^n a_{ii} x_i ^2 + \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^{n - 1} \mathop \sum \limits_{\,j = i + 1}^n a_{ij} x_{i\;} x_{\,j\;} $$

$$Y = a_0 + \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^n a_i x_i + \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^n a_{ii} x_i ^2 + \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^{n - 1} \mathop \sum \limits_{\,j = i + 1}^n a_{ij} x_{i\;} x_{\,j\;} $$

Y was predicted response and a 0 was the constant coefficient, n is number of factors, x i and x j were the non-coded variables a i , a ii and a ij . are the first-order, quadratic, and interaction effects respectively; i and j are the index numbers for factor. R 2 coefficient was determined to assay the quality of the polynomial model, whereas its statistical significance was checked by the F-test.

Phase-Π: influence of optimized processing conditions on physicochemical attributes of Ricotta cheese

The combinations of three conditions from Table 1 (90 °C, pH 7, CaCl2 6 mm; 100 °C, pH 5, CaCl2 4 mm and 75 °C, pH 8·4, Cl2 4 mm) having the highest yields were selected for the production of Ricotta cheese (Pizzillo et al. Reference Pizzillo, Claps, Cifuni, Fedele and Rubino2005) from a mixture of whey and buffalo skim milk (9 : 1). Each experiment was performed in duplicate. The cheese samples were vacuum packed and evaluated every 15 d for various physicochemical characteristics during storage of 60 d at 4 ± 2 °C.

The buffalo skim milk, cheddar cheese whey, a blend of whey with buffalo skim milk and Ricotta cheese were analysed for pH (Ong et al. Reference Ong, Dagastine, Kentish and Gras2007), acidity (method No. 947·05: AOAC, 2012), moisture by drying method, fat (Gerber method of Marshall, Reference Marshall1993), total protein (Kjeldahl method No. 991·20: AOAC, 2012), non-protein nitrogen (method No. 20-4: IDF, 2001), lactose (method No. 930·28: AOAC, 2012), ash (method No. 945·46: AOAC, 2012) and total solids (method No. 990·19, AOAC, 2012) after some modifications in the preparation of samples. Analyses of all parameters were carried out in triplicate. Results obtained were analysed statistically using Analysis of Variance Technique (ANOVA). Means were compared at 0·05 level of significance using Least Significance Difference (LSD) test as described by Steel et al. (Reference Steel, Torrie and Dickey1997).

Results and discussion

Effects of processing conditions (Temperature, pH and CaCl2) on yield/recovery of milk constituents

The impact of pH, CaCl2 concentration and temperature on the recovery/yield of milk constituents obtained from twenty experiments is presented in Table 1.

The effect of all factors on yield was calculated as follows:

$${\eqalign{{\rm Yield} =& -{\rm 2} \!\cdot\! {\rm 279} + 0 \!\cdot\! 0{\rm 66T}-0 \!\cdot\! {\rm 12}0{\rm P}-0 \!\cdot\! {\rm 171C} \cr &+ {\rm 9} \!\cdot\! {\rm 31} \times {\rm 1}0^{ - {\rm 3}} {\rm TP} + {\rm 1} \!\cdot\! {\rm 65} \times {\rm 1}0^{ - {\rm 3}} {\rm TC} \cr &+ 0 \!\cdot\! 0{\rm 11PC}-{\rm 6} \!\cdot\! {\rm 8}0{\rm 3} \times {\rm 1}0^{ - {\rm 4}} {\rm T}^{\rm 2} -0 \!\cdot\! 0{\rm 46P}^{\rm 2} \cr &-0 \!\cdot\! 0{\rm 4}0{\rm C}^{\rm 2}}} $$

$${\eqalign{{\rm Yield} =& -{\rm 2} \!\cdot\! {\rm 279} + 0 \!\cdot\! 0{\rm 66T}-0 \!\cdot\! {\rm 12}0{\rm P}-0 \!\cdot\! {\rm 171C} \cr &+ {\rm 9} \!\cdot\! {\rm 31} \times {\rm 1}0^{ - {\rm 3}} {\rm TP} + {\rm 1} \!\cdot\! {\rm 65} \times {\rm 1}0^{ - {\rm 3}} {\rm TC} \cr &+ 0 \!\cdot\! 0{\rm 11PC}-{\rm 6} \!\cdot\! {\rm 8}0{\rm 3} \times {\rm 1}0^{ - {\rm 4}} {\rm T}^{\rm 2} -0 \!\cdot\! 0{\rm 46P}^{\rm 2} \cr &-0 \!\cdot\! 0{\rm 4}0{\rm C}^{\rm 2}}} $$

The effect of all the parameters was found statistically significant at 95% confidence level. Graphical presentation of predicted vs. actual values of Ricotta cheese yield is shown in Fig. 1. The values predicted by the model vs. the observed data show a reliable correlation, especially considering the large ranges of factors. Minimum variations between predicted and observed values were observed by the model.

Fig. 1. Predicted vs. actual values of the response function production.

Figure 2a–c represented the effects of factors on yield/recovery of milk constituents in curd formation. Figure 2a indicated the strong response surface dependence on both pH and temperature. Both factors affected the yield which varied from 0·73 to 1·91% with an increase in pH 3·0 to 7·0 respectively at the same temperature (90 °C), however, when pH increased from 3·0 to 7·0 at low temperature 60 °C, they showed almost the same response of yield (0·81%). The yield/recovery of milk constituents mainly depends on the denaturation and aggregation of whey proteins during processing. β-Lg and α-La are about 50 and 20% of the total whey protein content. β-Lg exists in dimer form at neutral pH (Jovanovic et al. Reference Jovanovic, Miroljub and Ognjen2005). It contains two disulfide bonds and one free thiol (-SH) group in its structure (O'Kennedy & John, Reference O'Kennedy and John2009; Nicolai et al. Reference Nicolai, Britten and Schmitt2011). The aggregation of whey proteins at higher temperature is mainly due to the denaturation and interaction of free –SH group with the S–S bond of cystine-containing proteins such as β-Lg, κ-casein, α-La, and BSA (Considine et al. Reference Considine, Patel, Singh and Creamer2005). The complexes formed between them are known as coaggregates (Jovanovic et al. Reference Jovanovic, Miroljub and Ognjen2005). Whey proteins denaturation is initiated at 65 °C, but intensity increases as the temperature is elevated above 80 °C at pH 6·7 (Ruegg et al. Reference Ruegg, Moor and Blanc1977). The findings of Heni et al. (Reference Heni, Nidhi and Hilton2014) also supported the present results. They stated that intensity of reactions increases at temperatures above 85 °C and pH greater than 6. The isoelectric points of β-Lg and α -La are around pH 5·2 and pH 4·5–4·8 respectively The higher gelation could be due to higher isoelectric pH (5·2) of β-Lg which initiates isoelectric precipitation/aggregation at high pH than that observed with caseins (pH 4·6; Almecija et al. Reference Almecija, Ibanez, Guadix and Guadix2007).

Fig. 2. Response surface as a function of pH and temperature (a), as a function of CaCl2 and temperature (b) and as a function of CaCl2 and pH (c).

The present investigation showed that not only the higher temperature help to coagulate the whey proteins, but their combination with pH and CaCl2 concentration are more effective. The highest yield was recorded for 90 °C at pH 7 and 6 mM CaCl2 then for 100 °C at pH 5 and CaCl2 4 mm. Figure 2b showed the effect of temperature and CaCl2 on yield. Both factors affected the yield, but temperature had more effect. Yield increased from 0·80 to 1·22% as temperature increased from 60 to 90 °C respectively at same CaCl2 2·0 mm concentration. Figure 2c presented the yield dependence on pH vs. CaCl2. It is obvious that pH affected the yield more strongly as compared to CaCl2. It can also be predicted from Fig. 2c that the yield increased from 0·70 to 1·27% with the increase in pH from 3·0 to 7·0 keeping the concentration of CaCl2 constant at 2·0 mm.

Denaturation and aggregation of whey proteins at higher temperature is further elevated in the presence of calcium-ions, which facilitate the process of aggregation. The reason of higher yield could be due to unfolding of β-Lg followed by aggregation due to change in pH (Kawamura et al. Reference Kawamura, Mayuzumi, Nakamura, Koizumi, Kimura and Nishiya1993; Macleod et al. Reference Macleod, Fedio and Ozimek1995) and calcium chloride (De Wit & Klarenbeek, Reference De Wit and Klarenbeek1984; Mulvihill & Kinsella, Reference Mulvihill and Kinsella1988; Barbut & Foegeding, Reference Barbut and Foegeding1993). The calcium chloride addition decreases the pH and increases the ionic calcium concentration, which in combination with whey proteins causes structural changes during heat treatment that lead to milk coagulation (Omoarukhe et al. Reference Omoarukhe, On-Nom, Grandison and Lewis2010; Ramasubramanian et al. Reference Ramasubramanian, Arcy, Deeth and Eustina2014). Ju & Kilara (Reference Ju and Kilara1998) and Nguyen et al. (Reference Nguyen, Nicolai, Chassenieux, Schmitt and Bovetto2016) also reported that the addition of CaCl2 before heating greatly affected the gelation process of whey proteins. The presence of calcium ions increases the intermolecular linkage of anionic molecules due to the 27 carboxyl group in the β-Lg molecule (Phan-Xuan et al. Reference Phan-Xuan, Durand, Nicolai, Donato, Schmitt and Bovetto2014) and formation of protein-Ca-protein complexes. These results suggest that adding CaCl2 neutralized negative charges on the whey protein particle surface, permitting the intermolecular cross-linking and aggregation (Remondetto & Subirade, Reference Remondetto and Subirade2003). The large number of aggregates formed are micro-sized at 65–85 °C (Ni et al. Reference Ni, Lijie, Lei, Yali, Peng and Li2015).

Denatured whey proteins also aggregate due to the decrease in net charge on the proteins, which causes less repulsion. Moreover, heated whey proteins form a firm gel network because they are very sensitive to aggregation due to the presence of calcium ions during heating (Simons et al. Reference Simons, Kosters, Visschers and de Jongh2002). O'Kennedy & John (Reference O'Kennedy and John2009) showed that heating β-Lg at 78 °C for 10 min in the presence of calcium (5 mm) significantly increased the level of aggregated proteins at most pH values (5–7). In the present investigation the higher yield was noticed at both higher (7 and 8·4) and lower pH (5) values due to difference in calcium concentration and temperature.

The presentation of data in the form of 3-D surface graphs also revealed that all the three factors affected the yield of Ricotta cheese. Temperature and pH have a strong effect as compared to CaCl2. Ricotta cheese yield increased at higher temperature, pH and CaCl2. It is obvious from the results that these factors affect whey protein denaturation, precipitation and aggregation. Other factors which affect gel formation include high pressure (physically induced), enzymes (Aguilera & Rademacher, Reference Aguilera, Rademacher and Yada2004), molecular size, charge, composition of amino acids and their sequence, conformation, hydrophilic and hydrophobic ratio, rigidity and flexibility properties of whey proteins (De Wit, Reference De Wit1998). The change in electric charge on protein can also influence the aggregation and gel formation. The electric charge on the surface of β-Lg at a neutral pH of milk is around −8 mV. Heating at 85 °C increased the charge −46 to −30 mV at 0·10–5·0% concentration of WPI respectively (Honary & Zahir, Reference Honary and Zahir2013). The increase in charge can enhance the calcium binding affinity of protein which would require less calcium to induce aggregation. A study shows that methylated β-Lg (IEP from 5·2 to 6) exhibited more aggregation kinetics at pH 7·2 as compared to the non-modified β-Lg (IEP 5·2) during heating (Ni et al. Reference Ni, Lijie, Lei, Yali, Peng and Li2015).

The obtained results shown in the model ensured a good fitting of the observed data. RSM showed that the best processing condition optimized by the model should be 90 °C, pH 7 and 5 mm CaCl2. The yield obtained from three batches following these conditions showed a negligible difference in yield (1·84%) than the observed conditions followed in the experiments number 19 (1·87% yield). So, the three best (RC1: 90 °C, pH 7, CaCl2 6 mm, RC2: 100 °C, pH 5, CaCl2 4 mm and RC3: 75 °C, pH 8·4, CaCl2 4 mm) observed conditions were exploited for the production of Ricotta cheese in Phase-Π from a mixture of whey and buffalo skim milk (9 : 1). The physico-chemical analysis is shown in Table 2. The addition of milk to whey is common in Ricotta cheese making, which can also influence the yield and other quality attributes of Ricotta cheese when prepared under the optimized conditions of the present investigation.

Table 2. Physicochemical analysis of cheese whey, skim milk and their blend

Mean values of three replicates ± se

Physicochemical analysis of Ricotta cheese prepared from buffalo cheese whey and skim milk

The difference in yield and physicochemical characteristics of three Ricotta cheese are presented in Fig. 3, while the changes during storage are shown in Table 3. The Ricotta cheese yield has been estimated by several researchers who report that it depends on the percentages of milk added and their fat contents. A blend of 75% whey and 25% milk produces a yield of 11·3–11·8% (Modler, Reference Modler1995). Weatherup (Reference Weatherup1986) used a mixture of 80% (v/v) Cheddar whey with 20% (v/v) buffalo milk and precipitating at 87 °C after acidification to pH 5–6 with citric or acetic acid and recorded 12% (w/v). Ricotta cheese prepared from whey and skimmed milk showed a lower yield (Caro et al. Reference Caro, Soto, Franco, Meza-Nieto, Alfaro-Rodrıguez and Mateo2011). In the present experiment, the highest yield was recorded for RC1 (7·52%) as compared to RC2 and RC3 as shown in Fig. 3. The yield of Ricotta cheese of present finding was lower as compared to other scientists because they used high quantity of milk and milk fat for the production of Ricotta cheese.

Fig. 3. Mean values of yield and physicochemical analysis of Ricotta cheese. RC1 = Temperature 90 °C, pH 7, CaCl2 6 mm, RC2 = Temperature 75 °C, pH 8·4, CaCl2 4 mm, RC3 = Temperature 100 °C, pH 5, CaCl2 4 mm.

Table 3. Changes in physicochemical characteristics of Ricotta cheese varieties during storage

The values given are the means of various Ricotta cheese values (n = 3) ± se Within a block, values within row or column having different letters differ significantly, P < 0·05 or better

It is obvious that pH, acidity, protein and NPN analyzed for the three Ricotta cheese samples significantly (P < 0·01) differed from each other (Fig. 3), while during storage, a significant (P < 0·01) difference was also noticed in pH, acidity and NPN (Table 3). It is clear from Table 3 that mean values of pH of all samples decreased (0·94) and acidity increased (0·66%) significantly (P < 0·01) during 60 d of storage. The decrease in pH and increase in acidity during storage may be attributed to the increase in lactic acid due to growth of lactic acid bacterial culture, lactose utilization and hydrolysis of fat (Rotaru et al. Reference Rotaru, Mocanu, Uliescu and Andronoiu2008; Sulieman et al. Reference Sulieman, Eljack and Salih2012). These changes are attributed to enzymatic activities from indigenous and external microbial sources, which convert the lactose to lactic acid (Rejikumar & Devi, Reference Rejikumar and Devi2001). It has been detected through various studies that heat processing of whey affects the activity of β-galactosidase. At 55 to 75 °C, β -galactosidase activity decreased slightly, while heating whey to 85 °C for 30 min increased the rate of hydrolysis significantly (Rytkonen et al. Reference Rytkonen, Karttunen, Karttunen, Valkonen, Jenmalm, Alatossava, Bjorksten and Kokkonen2002), which could be the reason for hydrolysis of lactose into lactic acid.

The moisture content of RC1 Ricotta cheese was lower than the other two treatments (Fig. 3) which could be due to the higher temperature of processing and denaturation which ultimately decreased the moisture of Ricotta cheese. Among the three samples of Ricotta cheese, RC2 had lower and RC3 showed the higher fat content (Fig. 3). The difference in fat contents within Ricotta samples could be the difference in processing conditions during preparation of cheese. Pintado et al. (Reference Pintado, Lopes da Silva and Malcata1996) stated that fat content of whey cheese is affected by heating time, temperature, and the addition of milk either positively or negatively, and Pereira et al. (Reference Pereira, Merino, Jones and Singh2006) reported that increase in heating rate leads to a greater retention of fat. Protein contents was significantly (P < 0·01) different in all samples of Ricotta cheese. RC1 contained higher protein than others which could be due to higher denaturation of whey proteins at higher temperature and CaCl2 concentration, hence the decrease in protein during storage was non-significant (P > 0·05; data not shown), presumably due to lower proteolysis by lactic acid bacteria (Nour El Daim & El Zubeir, Reference Nour El Daim and El Zubeir2007; Rotaru et al. Reference Rotaru, Mocanu, Uliescu and Andronoiu2008).

The lowest NPN content was found in RC2, while no significant difference existed between RC1 and RC3. Temperature affected the denaturation of whey proteins. RC2 was processed at high temperature (100 °C) due to which its NPN% was high. Discharge of NPN increased by heating at 100 °C and increased more at elevated temperature (120–140 °C) due to cleavage of peptide bonds at high temperature (Mohammed et al. Reference Mohammed, Ryoya and Shunrokuro1985). The NPN of cheese is mainly composed of small peptides of 2 and 20 residues and free amino acids which increase significantly (P < 0·05) during ripening (El Galiou et al. Reference El Galiou, Zantar, Bakkali and Laglaou2013). Lactic acid bacteria and other enzymes are principal agents for the production of NPN in cheese (Fox & McSweeney, Reference Fox and McSweeney1996). The significant (P < 0·05) increase in NPN during storage might be due to pH values above 4·6, which promote the activity of peptidases in cheese during storage (Sheehan et al. Reference Sheehan, Patel, Drake and McSweeney2009).

The lactose content of RC1 was the lowest (4·4%), while the very minute difference was noticed in RC2 (5·0%) and RC3 (5·1%). Lactose concentration of all Ricotta cheese samples decreased non-significantly (P > 0·05) during 60 d storage (data not shown). Decreasing trend in lactose content during storage could be due to the production of lactic acid at refrigerated temperature (Rejikumar & Devi, Reference Rejikumar and Devi2001). There was a minor difference in the ash (%) of all samples (Fig. 3). Ash had also non-significant (P > 0·05) effect during storage (data not shown). RC1 had higher total solids (20·5%) and RC3 lower (16·7%) which could be due to degradation of total protein and decrease in fat content during storage period (Nour El Daim & El Zubeir, Reference Nour El Daim and El Zubeir2007).

Conclusions

The objective of the current research work was to optimize the processing conditions (pH, temperatures and calcium chloride) to increase the yield of Ricotta cheese from buffalo whey by using Central Composite Design (CCD) and Response Surface Methodology (RSM). Ricotta cheese prepared at 90 °C, pH 7·0 and CaCl2 6·0 mm showed the highest yield. The production of Ricotta cheese could increase the profitability of the local cheese industry in Pakistan following these optimized processing conditions.