When milk is heated above about 70°C, the whey proteins denature. Denaturation of β-lactoglobulin exposes a free thiol group that is usually buried within the protein structure, and this exposed thiol group can initiate a series of thiol–disulphide exchange reactions of the denatured β-lactoglobulin with κ-casein (κ-CN) or with other denatured whey proteins (Lowe et al. Reference Lowe, Anema, Bienvenue, Boland, Creamer and Jimenez-Flores2004). It is now generally accepted that, when milk is heated at pH values between 6·5 and 7·1, there is a pH-dependent distribution of the disulphide-bonded complexes of denatured whey proteins and κ-CN between the serum and colloidal phases (Anema & Li, Reference Anema and Li2003; Vasbinder & de Kruif, Reference Vasbinder and de Kruif2003; Donato & Dalgleish, Reference Donato and Dalgleish2006; Anema, Reference Anema2007; Donato et al. Reference Donato, Guyomarc'h, Amiot and Dalgleish2007).

However, there is still some debate over the sequence of events in the interaction reactions between the denatured whey proteins and κ-CN. Some reports suggest that κ-CN dissociates from the micelles early in the heating process and that the denatured whey proteins preferentially interact with the serum-phase κ-CN (Anema & Li, Reference Anema and Li2000; Anema, Reference Anema2007). This proposal is supported by the observation that significant dissociation of κ-CN can occur at temperatures below those at which the denaturation of whey proteins occurs (Anema & Klostermeyer, Reference Anema and Klostermeyer1997). In addition, significant dissociation of κ-CN occurs in systems that have been depleted of whey proteins (Anema & Li, Reference Anema and Li2000). The high ratio of denatured whey protein to κ-CN in the serum phase regardless of the pH at heating or the level of dissociated κ-CN may also suggest a preferential serum-phase reaction between the denatured whey proteins and κ-CN (Guyomarc'h et al. Reference Guyomarc'h, Law and Dalgleish2003; Donato & Dalgleish, Reference Donato and Dalgleish2006; Anema, Reference Anema2007).

Other reports suggest that, on heating milk, the denatured whey proteins first interact with κ-CN on the casein micelle surface, and that the whey protein−κ-CN complex subsequently dissociates from the casein micelles (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Donato and Dalgleish2005; Donato & Dalgleish, Reference Donato and Dalgleish2006; Donato et al. Reference Donato, Guyomarc'h, Amiot and Dalgleish2007). This proposal is supported by the observation that the addition of sodium caseinate to milk at its natural pH prior to heat treatment did not increase the level of serum-phase complexes between denatured whey proteins and κ-CN (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Donato and Dalgleish2005). A very recent study showed that, when κ-CN was added to milk prior to heat treatment, soluble κ-CN−denatured whey protein aggregates were formed, as determined by size exclusion chromatography (SEC; Donato et al. Reference Donato, Guyomarc'h, Amiot and Dalgleish2007). The SEC difference profiles between the sera from unheated and heated milk with added κ-CN showed a negative peak in the region of the whey proteins and a positive peak in the region of the soluble aggregates, indicating that the whey proteins were converted to soluble aggregates on heating. No negative peak was observed in the region of the added κ-CN, which was interpreted as indicating that the added κ-CN was not involved in the formation of the serum-phase aggregates and therefore that only the κ-CN originally bound to the casein micelles was involved in aggregate formation.

This current study was conducted in an attempt to provide evidence on whether the interaction of the denatured whey proteins with κ-CN on the casein micelle preceded the dissociation of κ-CN−whey protein complexes from the casein micelles, or whether κ-CN dissociated from the casein micelles early in the reaction, with the denatured whey proteins preferentially interacting with the serum-phase κ-CN. Three approaches were taken. Firstly, κ-CN was added to milk before pH adjustment and heating, which would indicate whether there was a preferential interaction of the denatured whey protein with the micelle-bound or serum-phase κ-CN. Secondly, the heating time at 90°C was varied, and the levels of native whey protein, serum-phase κ-CN and micelle-bound denatured whey protein were monitored in an attempt to determine whether κ-CN was found in the serum phase before significant levels of the whey proteins were denatured. Thirdly, the level of serum-phase κ-CN in milks heated at temperatures from 20 to 90°C was monitored to see whether κ-CN dissociated from the casein micelles at temperatures below those at which the whey proteins were denatured.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of κ-CN

κ-CN was purified using the methods described in detail by Cho et al. (Reference Cho, Singh and Creamer2003) and was stored in frozen solution until required.

Milk samples

Reconstituted skim milk samples were prepared by adding low heat skim milk powder (Fonterra Co-operative Group, New Zealand) to Milli-Q water to a final concentration of 10% (w/w) total solids, with a small amount of sodium azide (0·01% w/v) added as a preservative. For the milk samples with added κ-CN, the κ-CN solution was first added to the water at the required concentration (~0·1 or 0·2%, w/w) before addition of the milk powder. The reconstituted skim milk samples were allowed to equilibrate at ambient temperature (about 20°C) for at least 10 h before further treatment.

Adjustment of pH and heat treatments

The pH of the milk samples was adjusted to pH 6·5, 6·7 or 6·9 by the slow addition of 1 m-HCl or 1 m-NaOH to stirred solutions. The pH was allowed to equilibrate for at least 2 h and then minor re-adjustments were made. The milk samples were transferred to glass tubes and either held at 20°C or heated, with continuous rocking, in a thermostatically controlled oil bath preset to temperatures from 40 to 90°C for times up to 30 min. The heating time included the time to reach the experimental temperature. After heat treatment, the milk samples were cooled by immersion in cold running water until the temperature was below 30°C. The heated samples were stored overnight at ambient temperature before any analysis.

Centrifugation

Serum-phase caseins and whey proteins were defined as those that did not sediment from the milk during centrifugation at 14 000 rev/min (~25 000 g) for 1 h at 20°C in a bench centrifuge. A sample (1 ml) of each milk was placed in a small plastic tube of 1·5 ml total volume and centrifuged. After centrifuging, the clear supernatant (serum) was carefully poured from the pellet. The protein content and the composition of the supernatants were determined by gel electrophoresis and laser densitometry.

Gel electrophoresis and laser densitometry

The level of serum-phase casein and whey protein (α-lactalbumin and β-lactoglobulin combined) or native whey protein was determined using sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) under reducing conditions, as has been described previously (Anema & Klostermeyer, Reference Anema and Klostermeyer1997). For the serum-phase casein and whey proteins, the centrifugal supernatants were analysed by SDS-PAGE without further treatment. For the native whey proteins in the heated milks, the casein and the denatured whey proteins were precipitated from the milk by adjustment of the pH to 4·6, and the precipitate was removed by centrifuging in a bench centrifuge. The resultant supernatant was analysed by SDS-PAGE to give the level of native whey protein remaining in the milk sample.

The SDS-PAGE gels were scanned using a Molecular Dynamics Model PD-SI computing densitometer (Molecular Dynamics Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and integrated using the Imagequant software associated with the densitometer. The quantity of each protein in the ultracentrifugal supernatants was determined as a percentage of that in the original milk samples.

Results and Discussion

Effect of addition of κ-CN to milk on the distribution of denatured whey protein between the colloidal and serum phases

In order to examine whether there was a preferential interaction of denatured whey protein with serum-phase or micelle-bound κ-CN, κ-CN was added to the milk prior to pH adjustment and heat treatment at 90°C for 15 min. The level of κ-CN added was approximately 0·1 and 0·2%, which increased the κ-CN level from about 0·45% to about 0·55 and 0·65% respectively. Figure 1 shows representative gels for the milks and serums from the unheated and heated milk samples with added κ-CN in comparison with those without added κ-CN, whereas Table 1 shows the level of denatured whey protein in the serum for the milk samples heated at the different pH values.

Fig. 1. Selected SDS-PAGE patterns of the proteins in skim milk samples and serums from unheated and heated skim milk samples. (A) skim milk; (B) skim milk+0·2% (w/w) κ-casein. Lane 1: unheated skim milk, dilution 1:40; Lane 2: serum from unheated skim milk, dilution 1:10; Lanes 3−5: serum from heated (90°C/15 min) skim milk at pH 6·5, 6·7 and 6·9 respectively, dilution 1:10. (i) αS-casein; (ii) β-casein; (iii) κ-casein; (iv) β-lactoglobulin; (v) α-lactalbumin.

Table 1. Serum-phase denatured whey proteins from skim milk with different levels of added κ-casein that were adjusted to pH 6·5, 6·7 and 6·9 before heating at 90°C for 15 min. The numbers represent the average and standard deviation of triplicate measurements

† Data at a given pH with the same letters are not significantly different from each other at P<0·05

The added κ-CN remained in the serum when the unheated milk was centrifuged (Fig. 1). On heating at pH 6·5, for the milk without added κ-CN, most of the denatured whey protein interacted with the casein micelles, and only 35% of the denatured whey protein remained in the serum. However, for the milks with 0·1 and 0·2% added κ-CN, the level of denatured whey protein remaining in the serum increased to ~65 and ~85% of the total, respectively. When the pH at heating was increased to pH 6·7 and pH 6·9, the level of κ-CN in the serum increased with increasing pH at heating because of the pH-dependent movement of κ-CN from the micelles to the serum phase (Fig. 1; Donato & Dalgleish, Reference Donato and Dalgleish2006; Anema, Reference Anema2007). As expected, the κ-CN levels in the serum from the milks with added κ-CN were higher than those in the serum from the milks without added κ-CN at all pH at heating (Fig. 1), indicating that similar levels of κ-CN to those observed for the milks without added κ-CN were moved from the micelle to the serum phase. As a consequence, the level of denatured whey protein in the serum-phase increased as the pH at heating was increased; however, at every pH at heating, the level of denatured whey protein in the serum increased as the level of added κ-CN increased (Table 1).

These results demonstrated that, when κ-CN was added to the serum phase, there was a preferential reaction of the denatured whey proteins with the serum-phase κ-CN when the milk was heated. This was most evident for the samples heated at pH 6·5, as, at this pH, the indigenous κ-CN remained predominantly associated with the micelles, and, in milk without added κ-CN, the denatured whey proteins predominantly interacted with κ-CN on the casein micelles. However, when κ-CN was added to the serum phase of the milk at pH 6·5, there was a preferential interaction with the serum-phase κ-CN and the majority of the denatured whey protein remained in the serum, associated with the added κ-CN (Fig. 1 & Table 1). Fig. 1 also indicates that, on heating milk at pH 6·7 or 6·9, the increase in serum-phase κ-CN and denatured whey protein was accompanied by some increases in the levels of serum-phase αs-casein (αs-CN) and β-casein (β-CN).

Effect of heating time on whey protein denaturation and the distribution of κ-CN and whey protein between the colloidal and serum phases

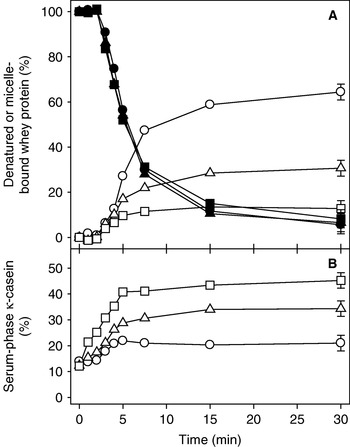

Figure 2 shows representative gels for the effect of heating time on the serum protein composition and the denaturation of whey proteins from milk samples that were heated at 90°C for times up to 30 min. Figure 3 shows the level of denaturation of the whey proteins, the level of whey proteins associated with the casein micelles and the level of serum-phase κ-CN for the milk samples at pH 6·5−6·9 that were heated at 90°C for times up to 30 min. The heat-up time for the milk samples was about 2 min; therefore, little denaturation of the whey proteins was observed until the milk was heated for longer than 2 min, and the level of denaturation increased with heating time, so that almost 100% of the whey proteins were denatured after 30 min of heating. Little effect of the pH at heating was observed, with similar denaturation levels at each heating time regardless of the pH value (Fig. 2 & Fig. 3A).

Fig. 2. Selected SDS-PAGE patterns of the proteins in the serums from skim milk samples heated at 90°C for different times. (A) serums from skim milk at pH 6·5; (B) serums from skim milk at pH 6·9. Lanes 1−9: serums from milk heated at 90°C for 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7·5, 15 and 30 min respectively. (i) αS-casein; (ii) β-casein; (iii) κ-casein; (iv) β-lactoglobulin; (v) α-lactalbumin.

Fig. 3. Level of denatured whey protein, micelle-bound whey protein and serum-phase κ-casein in milk samples heated at 90°C for different times. A: denatured (filled symbols) and micelle-bound (open symbols) whey proteins; B: serum-phase κ-casein. The skim milks were adjusted to pH 6·5 (○, •), pH 6·7 (△, ▲) and pH 6·9 (□, ■) before heating. Error bars represent the standard deviations of triplicate measurements.

For the milk sample at pH 6·5, the level of κ-CN in the serum increased from about 10 to 20% during the first 5 min of heating, with little further change on prolonged heating. A similar general behaviour was observed for the milk samples at pH 6·7 and pH 6·9, with proportionally higher levels of κ-CN at each heating time as the milk pH was increased. About 30 and 40% of the κ-CN was in the serum after 5 min of heating for the milks at pH 6·7 and pH 6·9 respectively, with little further change in these levels when the heating time was extended beyond 5 min. The increase in serum-phase κ-CN on heating at pH 6·7 and 6·9 was accompanied by some increases in the level of serum-phase αs-CN and β-CN (Fig. 2).

For whey proteins associating with the casein micelles, no association occurred at heating times of 2 min or less regardless of the pH at heating, which was expected as no denaturation of the whey proteins occurred under these conditions. At longer heating times, the level of whey protein interacting with the casein micelles increased with heating time up to ~5−7·5 min, and then plateaued on longer heating. The level of whey protein interacting with the casein micelles increased with decreasing pH so that, after 30 min of heating, about 60, 30 and 10% of the whey proteins were associated with the micelles at pH 6·5, 6·7 and 6·9 respectively.

Figures 2 & 3 demonstrate that, for the milks at pH 6·5−6·9, the κ-CN dissociated from the casein micelles before (significant) levels of the whey proteins were denatured. The dissociation of κ-CN reached its maximum level after only about 5 min of heating, whereas only about 40−50% of the whey proteins had denatured after this heating time. In addition, at pH 6·7 and pH 6·9, little further interaction of the whey proteins with the casein micelles occurred beyond 5 min of heating (Fig. 3). As the maximum level of κ-CN had already dissociated from the micelles after 5 min of heating, this indicated that there was a preferential interaction of the denatured whey proteins with serum-phase κ-CN. In contrast, for the sample at pH 6·5, the level of whey protein interacting with the casein micelles increased with heating time up to 15 min, at which time >90% of the whey proteins were denatured. In the pH 6·5 sample, relatively low levels of κ-CN were in the serum, and this level of serum-phase κ-CN may have been insufficient to interact with all the denatured whey proteins; therefore interaction of the denatured whey proteins with κ-CN in both the serum phase and on the casein micelles continued until virtually all the whey protein was denatured.

Effect of heating temperature on the distribution of κ-CN and whey protein between the colloidal and serum phases

Figure 4 shows representative SDS-PAGE gels of the serum protein compositions from milk samples that were heated at 20−90°C for 15 min. Figure 5 shows the levels of serum-phase κ-CN and whey protein from the milk samples at pH 6·5−6·9 that were heated at 20−90°C for 15 min. For the milk at pH 6·5, low levels of κ-CN were in the serum phase at all temperatures. However, for the milk samples at pH 6·7 and pH 6·9, the level of κ-CN in the serum increased as the heating temperature was increased, with proportionally higher levels as the pH was increased at each heating temperature (Fig. 4 & Fig. 5). This was accompanied by some increases in the level of serum-phase αs-CN and β-CN (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Selected SDS-PAGE patterns of skim milk samples and serums from skim milk samples heated for 15 min at different temperatures. (A) skim milk and serums from milk heated at pH 6·5; (B) skim milk and serums from milk heated at pH 6·9. Lanes 1−7: serum from skim milk heated for 15 min at 20, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80 and 90°C respectively, dilution 1:10; lane 8: skim milk, dilution 1:40. (i) αS-casein; (ii) β-casein; (iii) κ-casein; (iv) β-lactoglobulin; (v) α-lactalbumin.

Fig. 5. Level of serum-phase whey protein (filled symbols) and κ-casein (open symbols) in milk samples heated for 15 min at different temperatures. The milks samples were adjusted to pH 6·5 (○, •), pH 6·7 (△, ▲) and pH 6·9 (□, ■) before heating. Error bars represent the standard deviations of triplicate measurements.

All the whey proteins were in the serum at temperatures below 70°C regardless of the pH of the milk before heating, which was not surprising as the whey proteins were not significantly denatured at these temperatures (results not shown). However, at temperatures above 70°C, the level of whey protein in the serum was dependent on the pH of the milk at heating. At pH 6·5, the level of whey protein decreased with increasing temperature so that about 40% of the whey protein remained in the serum after heating at 90°C. Higher levels of whey protein remained in the serum as the pH at heating was increased, so that about 70% and about 90% of the whey proteins were in the serum at pH 6·7 and pH 6·9 respectively after heating at 90°C. This difference in serum-phase whey proteins was not related to the denaturation of the whey proteins, as treatment above 70°C denatured the same level of whey proteins at all pH (results not shown). After a heat treatment at 90°C, about 90% of the whey proteins were denatured at all milk pH.

These results, which are in agreement with an earlier report (Anema & Klostermeyer, Reference Anema and Klostermeyer1997), clearly show that κ-CN was moved to the serum phase at temperatures below those at which the whey proteins were denatured (<70°C). The level of serum-phase κ-CN increased with increasing temperature, and there was no significant change in this behaviour at temperatures above or below 70°C. This indicated that the interaction of denatured whey proteins with κ-CN on the micelle surface was not a prerequisite for the dissociation of κ-CN from the micelles.

When 0·1 to 0·2% of κ-CN is added to the milk serum (Fig. 1, Table 1) or when high levels of κ-CN are dissociated into the serum (Fig. 2, Fig. 3), there will be a significant number advantage of serum κ-CN molecules over the number of casein micelles containing the colloidal κ-CN. Therefore, if the interaction of the denatured whey proteins with κ-CN is dependent on the collision rate between the interacting species, the preferential interaction of the denatured whey proteins with the serum-phase κ-CN may simply be a consequence of the larger number of serum-phase κ-CN molecules over the number of casein micelles and therefore the higher number of collisions between these serum-phase components. In addition, it is likely that the reactive thiol groups of the denatured whey proteins will require the correct orientation for interaction to occur with the disulphide bonds of κ-CN. The κ-CN on the casein micelles will have restricted mobility and probably provide some steric hindrance to approaching molecules when compared with the κ-CN in the serum phase, and this may also contribute to the preferential interaction of the denatured whey proteins with the serum-phase κ-CN.

Although this current study indicated that κ-CN dissociated from the casein micelles in the early stages of heating, and that the denatured whey proteins preferentially interacted with the serum-phase κ-CN, this contrasts with other reports, which suggest that the denatured whey proteins first interact with κ-CN on the casein micelle surface and that the whey protein−κ-CN complex subsequently dissociates from the casein micelles (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Donato and Dalgleish2005; Donato & Dalgleish, Reference Donato and Dalgleish2006; Donato et al. Reference Donato, Guyomarc'h, Amiot and Dalgleish2007). In a recent study by Donato et al. (Reference Donato, Guyomarc'h, Amiot and Dalgleish2007), the formation of serum-phase κ-CN−denatured whey protein aggregates in heated milks with and without added κ-CN was determined using SEC. The SEC difference profiles between the sera from unheated and heated milk with added κ-CN showed a negative peak in the region of the whey proteins and a positive peak in the region of the soluble aggregates, indicating that the whey proteins are converted to soluble aggregates on heating. No negative peak was observed in the region of the added κ-CN, which was interpreted as indicating that the added κ-CN is not involved in the formation of the serum-phase aggregates and therefore that only micelle-bound κ-CN is involved in aggregate formation.

However, under these conditions, indigenous micelle-bound κ-CN dissociates from the casein micelles on heating (Donato & Dalgleish, Reference Donato and Dalgleish2006; Anema, Reference Anema2007), and the ratio of κ-CN to whey protein, especially in the serum phase, is markedly increased. Therefore, the size and the composition of the soluble aggregates may be altered, especially by forming smaller aggregates. This may affect the SEC profiles, especially the difference profiles in the region of the added κ-CN. In addition, almost all the denatured whey proteins are found in the serum phase when only low levels of κ-CN are transferred to the serum and the ratio of κ-CN to denatured whey protein is low and relatively constant (Donato & Dalgleish, Reference Donato and Dalgleish2006; Anema, Reference Anema2007); therefore, only small amounts of the added κ-CN may interact with the denatured whey proteins, and some of this may be replenished by the dissociation of the indigenous κ-CN from the micelles on heating. The observation of only small changes in the SEC difference profiles is thus not conclusive evidence that interactions of the denatured whey proteins with the casein micelles precede the dissociation of κ-CN from the micelles.

Although it is clearly established that κ-CN dissociates from the casein micelles on heating, it is still unknown what causes the dissociation to occur. In recent models of the casein micelles, the micelle structure is maintained by hydrophobic interactions and by colloidal calcium phosphate (Horne, Reference Horne1998; Walstra, Reference Walstra1999). Hydrophobic interactions increase with temperature in the range used in these experiments, and the level of colloidal calcium phosphate increases with increasing temperature; therefore, the casein proteins should be more strongly held within the casein micelle structure. The observation that the dissociation is pH dependent suggests that charge effects may be involved. The formation of serum-phase κ-CN is accompanied by some increase in serum-phase αs-CN and β-CN (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3), which suggests that a substantial rearrangement of the casein micelle structure may be occurring during heating, as has been suggested previously (Anema & Li, Reference Anema and Li2000). Clearly, further studies to elucidate the mechanism for the dissociation of κ-CN (as well as αs-CN and β-CN) from the casein micelles in milk are required. It would also be interesting to investigate whether this dissociation of casein is compatible with the structure and stability of the casein micelles that has been described in recent models (Horne, Reference Horne1998; Walstra, Reference Walstra1999).

The interaction between the denatured whey proteins and κ-CN forms small serum-phase aggregates (Guyomarc'h et al. Reference Guyomarc'h, Law and Dalgleish2003; Rodriguez del Angel & Dalgleish, Reference Rodriguez and Dalgleish2006; Anema, Reference Anema2007), whereas the interaction between denatured whey proteins in the absence of casein can form large aggregates at the ionic strength found in milk (Schorsch et al. Reference Schorsch, Wilkins, Jones and Norton2001). It has long been known that the addition of casein, particularly κ-CN to whey proteins prior to heat treatment limits the aggregate size of the denatured whey proteins (Kenkare et al. Reference Kenkare, Morr and Gould1964; Morr & Josephson, Reference Morr and Josephson1968; McKenzie et al. Reference McKenzie, Norton and Sawyer1971) and this may suggest a preferential reaction between κ-CN and the denatured whey proteins (particularly β-lactoglobulin) over interactions between the denatured whey proteins. The disulphide bonds in κ-CN are in the hydrophobic N-terminal (para-κ-CN) domain, whereas the hydrophilic and highly charged C-terminal (glyco-macro-peptide) domain does not readily interact and actually acts as a stabilizing hairy layer when associated with the surface of colloidal particles such as casein micelles (Holt & Horne, Reference Holt and Horne1996; Horne, Reference Horne1998; Walstra, Reference Walstra1999) or even latex particles (Anema, Reference Anema1997). Therefore, rather than a preferential interaction between κ-CN and the denatured whey proteins, it is likely that the incorporation of κ-CN into the aggregates acts as a chain terminator, limiting aggregate size and stabilizing the aggregates with a surface location.

In conclusion, this study showed that: when κ-CN was added to the milk serum, and the milk was heated at 90°C under conditions where little κ-CN dissociates from the casein micelles (pH 6·5), there was a preferential interaction between the denatured whey proteins and the serum-phase κ-CN (Fig. 1 & Table 1); κ-CN dissociated from the casein micelles before significant levels of whey proteins were denatured and the maximum level of dissociation of κ-CN was achieved when only about half the whey proteins were denatured (Fig. 2 & Fig. 3); κ-CN dissociated from the casein micelles at temperatures below those at which the whey proteins denature (Fig. 4 & Fig. 5). Based on these observations, it appears that κ-CN dissociation from the micelles is a rapid process and can precede the interaction reactions of the denatured whey proteins with κ-CN, on heating at 90°C.

The author would like to thank Claire Woodhall for proofreading the manuscript. This work was funded by the New Zealand Foundation for Research, Science and Technology, contract numbers DRIX0201 and DRIX0701.