Introduction

On November 14, 2015, an intriguing find made news at the highly anticipated and publicized archaeological site of the Mausoleum of Marquis of Haihun (Haihunhou 海昏侯) near Nanchang 南昌, Jiangxi 江西.Footnote 1 A number of broken lacquered wooden boards were retrieved from the main burial chamber (Figure 1). A preliminary examination revealed a painted portrait of Confucius (ca. 551–479 BCE) in full-color and his inscribed biography in black ink. The form and size of the boards as well as the material of lacquered wood prompted archaeologists to identify the fragments to be part of a wooden screen, and they naturally dubbed it the “Confucius Screen” (Kongzi pingfeng 孔子屏風), a name that quickly gained popularity in various media reports and among enthusiastic scholars. In the next two weeks, more pieces were discovered, including, curiously, a large rectangular bronze plate found broken in half, which at the time was thought to be the back panel of the wooden screen. The excitement attending the discovery of the earliest known image of Confucius and new information about his life offered by the inscription drew all the attention to Confucius,Footnote 2 and few noticed the rather unusual feature of a wooden screen having a bronze panel attached to its back.

Figure 1 Archaeologists retrieving fragments of the lacquer-painted wooden boards on November 14, 2015, from www.chinanews.com/cul/2015/11-14/7623478.shtml

It was not until April 7, 2016 that a well-known and curious archaeologist named Wang Renxiang 王仁湘 published a blog entry and proposed a different theory. After making a trip to examine all the retrieved pieces of the “Confucius Screen,” Wang rejected this identification and proposed that it was a “standing mirror” (lijing 立鏡). He speculated that it was originally composed of the bronze panel (i.e., the mirror) and a wooden mirror frame. The frame has a lacquer-painted cover and a backboard. It was on the back of the mirror frame that the portrait of Confucius and his biography, as well as the then-newly identified images of several of his disciples and their biographies were painted and inscribed.Footnote 3

The following further examination in the indoor excavation concurred with Wang's new theory and revealed many more details that were not available in the initial report. A crucial hint at the identification of the object was a relatively well-preserved inscription on the badly damaged cover. It includes a self-reference, yijing 衣鏡, which semantically should mean a “covered mirror,” but has been functionally understood as a “dressing mirror,” that is, a mirror assisting the user to get dressed.Footnote 4 The official preliminary site report subsequently adopted this identification.Footnote 5 A separate article by the excavators focusing on this particular object introduced the now-established designation, “Confucius Dressing Mirror” (Kongzi yijing 孔子衣鏡) later in 2016.Footnote 6 Nevertheless, the public and scholarly fascination remains steadfastly on Confucius and, to a lesser extent, on his disciples, and their lives rediscovered in the inscriptions. What has eluded us is the significance of the material change from taking the object as a screen to identifying it as a mirror. The immediate context of the object—the tomb of the Marquis of Haihun—also ironically eluded many observers who enthusiastically followed this archaeological spectacle: one of the ten “Most Important Archaeological Finds of 2015.”Footnote 7

“[O]bjects do not just provide a stage setting to human action; they are integral to it.”Footnote 8 However, it is reasonable to say that neither the entombed “Mirror” nor the buried Marquis of Haihun were meant to be brought back to the world of the living. This unexpected afterlife under the spotlight naturally leads to a probe into their lives prior to the interment. “[A]s people and objects gather time, movement and change, they are constantly transformed, and these transformations of person and object are tied up with each other.”Footnote 9 It turns out that the transformations undergone by both the “Mirror” and the Marquis are equally complicated and intricately entangled, despite the fact that, since the two were unearthed, the Marquis of Haihun—the infamous Liu He 劉賀 (92–59 BCE)—has received a disproportionate amount of scrutiny, while the “Mirror” as an object remains elusive. This is because of Liu He's historically unique status as the ninth emperor of the Western Han (202 BCE–9 CE) at age of seventeen and his dramatic fall after only twenty-seven days, when he was accused of being “licentious and lewd” (yinlun 淫亂)Footnote 10 and thus morally unfit for the throne. The somewhat uncanny “Mirror,” featuring Confucius and his celebrated worthy disciples, is therefore unsurprisingly interpreted by some as a tool for self-reflection and moral cultivation for the benefit of the young deposed emperor in his short and precarious remaining life before his death at age thirty-four.Footnote 11 In other words, the “Mirror” has been taken as a “lived object”—a personal belonging of the deceasedFootnote 12—used in Liu He's life for its attributed symbolic function to morally “illuminate” its owner and user. The presence of the “Mirror” in Liu He's tomb is largely taken for granted as part of the grave goods, whose conventional interpretation suggests that it may benefit the tomb occupant or continue to function in his afterlife just as it did in his life.

However, the exact nature or function of the “Mirror” in its own and Liu He's afterlives has not been sufficiently addressed. This is due, on one hand, to the overwhelming attention paid to the Confucius image and the moral as well as political implications of Confucian self-cultivation that it signaled; on the other hand, and more importantly, it is a result of overlooking the material side of the object and the mortuary context of its entombment. To remedy this imbalance, the present study focuses on the following two aspects of the “Mirror” as an assemblage: its material integrity and its life and afterlife, which are enmeshed with those of the Marquis. The making of the object and the person illuminate each other. In the sections that follow, I will focus on the material and physical composition of the “Mirror” as well as its mortuary and ritual function in the broader context of funerary material culture and burial practice in early imperial China. This allows me to raise questions about the current identification of the “Mirror” as a functional “dressing mirror” and a “lived object” used by Liu He for moral self-cultivation or political self-preservation when he was alive. Alternatively, I propose to consider the “Mirror” as a composite talisman to protect the deceased Marquis against baleful and harmful influences in the tomb and in his afterlife. It is my hope that such a holistic and contextual analysis ultimately will contribute to a fuller understanding of the inseparable material, social, and cultural world of the Han China.

The Person: The Life and Afterlife of Liu He (92–59 BCE)

Before delving into a detailed analysis of the “Mirror,” a brief introduction to the historical circumstances surrounding Liu He's life and death, as well as those around the extraordinary discovery of his tomb is in order. Liu He was born in 92 BCE, the son of Liu Bo 劉髆, the fifth son of Emperor Wu of Han 漢武帝 (r. 141–87 BCE) and his beloved Lady Li 李夫人. Liu Bo was bestowed the title of King of Changyi 昌邑王, and he was the ruler of this princely kingdom located in present-day Shandong 山東.Footnote 13 When Liu Bo died in 88 BCE, his young child, Liu He, inherited both his title and the kingdom, continuing a privileged life into his teen years on the east coast of the Han Empire. When Emperor Zhao 昭帝 (r. 87–74 BCE) died without an heir in 74 BCE, Huo Guang 霍光(d. 68 BCE), the powerful regent at the court, unexpectedly chose Liu He, the seventeen-year old nephew of the late emperor, for the throne. This was the turning point in Liu He's life, as he was called upon to rush to the capital Chang'an and became the ninth emperor of the Han.

On the twenty-seventh day of Liu He's reign, however, he was deposed by Huo Guang in favor of another great-grandson of Emperor Wu, the future Emperor Xuan 宣帝 (r. 74–49 BCE). Liu He was first sent back to Shandong under the watchful eyes of the newly enthroned Emperor Xuan and his imperial court. Soon Liu He's kingdom was degraded and he was then demoted to the status of a commoner. It was only in 63 BCE, after years of suspicion and hostility, that Emperor Xuan felt politically secure enough to take pity on Liu He and relocate him to the Yuzhang 豫章 Prefecture in present-day Jiangxi, a remote corner in the southeast of the empire. There Liu He was given the minor title of Marquis of Haihun 海昏侯.Footnote 14 The Haihun Marquisate had a modest tax income of four thousand households, but Liu He was permanently confined to his marquisate until death and forbidden from participating in any imperial ancestral rituals and courtly affairs.Footnote 15

Liu He died at the age of thirty-four in 59 BCE. Despite the premature death of two of his heirs, the Marquisate of Haihun lasted four more generations into the Eastern Han (25–220 CE). In the Han dynastic history, the Hanshu, we read, “After being on the throne for twenty-seven days, because of licentious and lewd behaviors, [Liu He] was deposed and sent back to his former kingdom” 立二十七日, 以行淫亂, 廢歸故國.Footnote 16 This is how Liu He has been officially remembered, together with many other accounts and anecdotal stories in the received literature, all alluding to his personal transgressions and moral failures as the cause of his truncated rule.

In 2011, law enforcement and archaeologists were alerted by the locals about looting activities taking place at an ancient burial site on Dundunshan 墩墩山, “Hill of Mounds,” about sixty kilometers north of Nanchang, Jiangxi. Archaeologists spent the next five years systematically surveying and investigating the surrounding area (5 km2). The surveys and subsequent excavations located and confirmed the seat of the Han Marquisate of Haihun at the Zijincheng 紫金城 site, and identified walled mausoleums of multiple generations of the Marquis of Haihun as well as cemeteries of the elite and common residents of the Marquisate.Footnote 17

From 2015 to 2016, the largest tomb of all, Tomb M1, was meticulously excavated. With great anticipation, archaeologists finally reached the bottom of a deeply dug earthen pit of this large-scale shaft tomb and revealed an enormous wooden burial structure of multiple chambers. Inside the middle chamber, a set of nearly flattened coffins was found. The nested coffins had been crushed by the collapsing weight of the piled earth on top of them, which had concealed this magnificent tomb for over two millennia. Inside the inner coffin, a badly preserved skeleton lay on a mat made of liuli-glass, an exuberantly expensive material exclusively produced by the Han imperial workshop. Underneath the mat, there was a layer of one hundred neatly arranged pieces of pure gold disks. Archaeologists had already retrieved an astonishing amount of gold in this tomb, resulting a total of 115 kilograms of 478 pieces in a variety of shapes including disks, plaques, horse-hoof shaped ingots, and what is known from the textual sources as linzhijin 麟趾金, gold ingots in a toe-shape of the auspicious mythical animal Qilin 麒麟.Footnote 18

Around the waist area of the skeletal remains, a small jade seal was found. The inscription of the unmistaken name “Liu He” on the seal confirmed what archaeologists had long suspected about the identity of the tomb occupant (Figure 2). Tomb M1, or now more famously known as the Haihunhou Tomb, was where Liu He, the infamously deposed ninth emperor of Han, was put to rest.Footnote 19 This is also an extremely rare case of an archaeological find in which not only the tomb of this scale escaped the nearly inevitable fate of looting (ancient and modern) and remained intact prior to the scientific excavation, the tomb occupant was also both archaeologically and historically identified.

Figure 2: A jade seal of Liu He, modified after Kaogu 2017.6, 60, fig. 50, courtesy of Yang Jun, Jiangxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology

The Place: The Haihunhou Mausoleum

The Haihunhou Mausoleum is a walled burial complex of a sprawling 4.6 hectares or 11.4 acres (Figure 3). There are two primary tombs—one for Liu He (M1) and the other presumably for his wife (M2, unexcavated)—one chariot-and-horse pit (K1),Footnote 20 and seven accompanying burials (M3–9), one of which has recently been identified as the tomb of Liu He's eldest son, Liu Chongguo 劉充國 (M5). Liu He and his wife were buried side-by-side on top of the “Hill of Mounds.” In front of their tombs, archaeologists have discovered the foundation of a four-building complex that they suspect is the couple's shared sacrificial shrine.Footnote 21 The structure and layout of Liu He's mausoleum is not unusual for its time, but it exceeds the statutory and sumptuary rules for his status as a Marquis at the time of his death. Some scholars argued that Liu He's unique status as a deposed emperor and his complicated relationship with Emperor Xuan might account for his exceedingly lavish burial.Footnote 22

Figure 3 Plan of the Haihunhou Mausoleum, modified after Kaogu 2017.6, 47, fig. 3

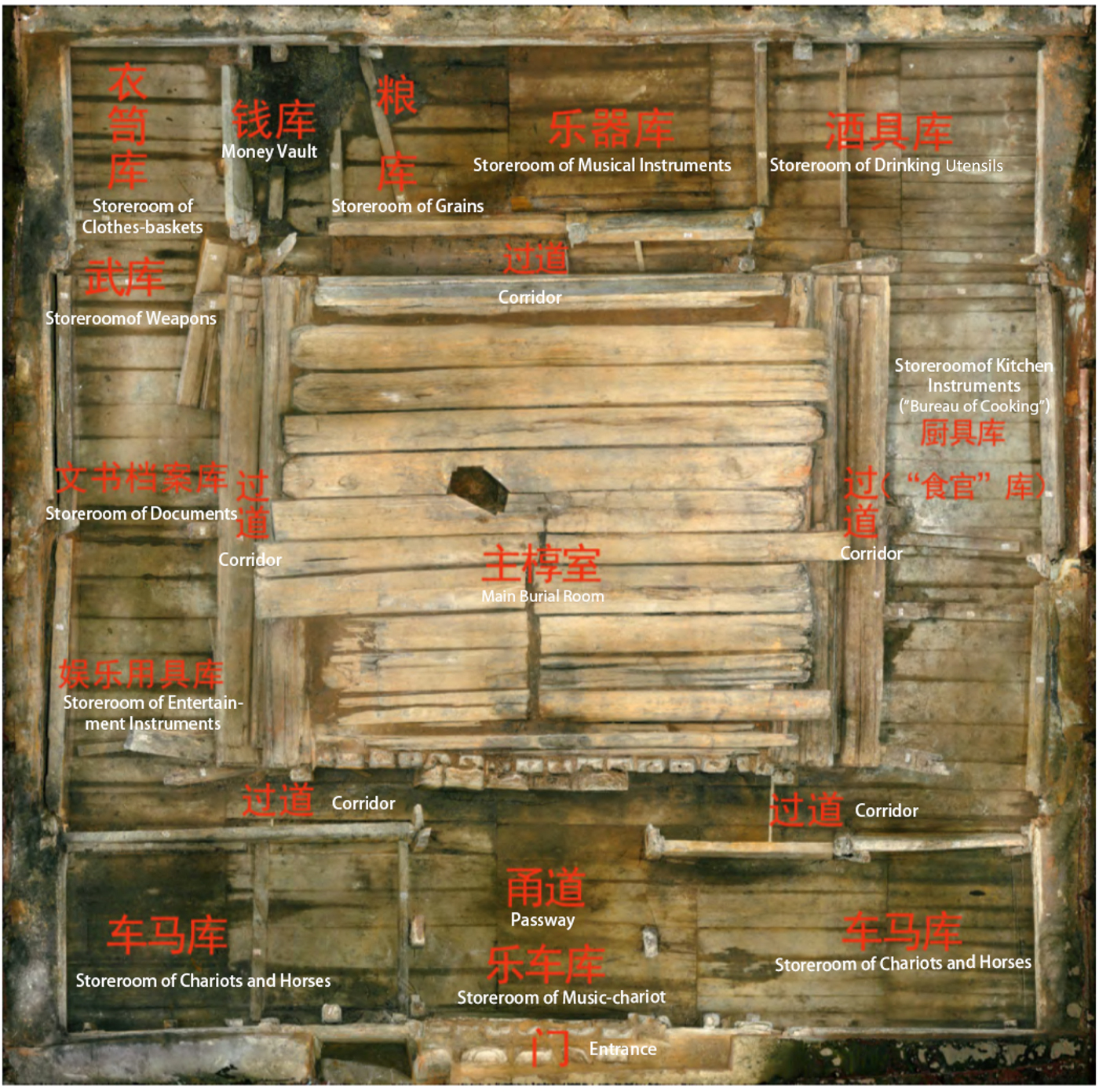

Liu He's tomb (M1) is a square-shaped earthen pit with one tomb ramp, the total size of which is about 400m2. Inside the grave pit, deep underground, a three-meter high wooden burial structure (guo 槨) was built up from the bottom of the pit. It was divided into multiple rooms on all four sides, the “storage rooms,” as excavators call them now. There is a main chamber in the middle of the burial structure. A corridor is formed in between the “storage rooms” and the main chamber (Figure 4). The “storage rooms” were filled with exquisite grave goods of all sorts. A total of over 10,000 sets and pieces of entombed objects have been retrieved so far.Footnote 23 These side rooms are designated by the excavators according to their assumed function, based on the material content of the buried goods. For example, the “Money Vault” yielded about ten tons of bronze coins, an estimate of two million coins, many of which are intact in strings of 1000-coins known as one guan 貫.Footnote 24 The “Document Storeroom,” or perhaps more accurately, a library/archive, housed a selection of Classical Confucian texts. They include extant excerpts or unknown and lost sections from texts such as the Book of Odes (Shijing 詩經), the Annals of Springs and Autumns (Chunqiu 春秋), the Analects (Lunyu 論語),Footnote 25 the Records of Rites (Liji 禮記), the Classics of Filial Piety (Xiaojing 孝經), and the Book of Changes (Yi 易). In addition, there are other master literature and literary compositions, medical and mantic manuals, technical instructions for playing the popular game of Liubo 六博, and administrative documents including memorials written by Liu He to the imperial court. These texts and documents were written on a total of 5,200 pieces of bamboo slips and wooden boards.Footnote 26

Figure 4 Plan of the wooden burial structure (guoshi) of the tomb of Marquis of Haihun (M1), modified after Kaogu 2017.6, 50, fig. 10, courtesy of Yang Jun, Jiangxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology

The main room in the middle of the burial structure has a spacious size of 51.8m2. It is divided into two halves by a separating wall but connected through a doorway in the middle. Liu He's nested coffins were placed in the east chamber, together with a large number of bronze ritual vessels.Footnote 27 In the west chamber, archaeologists found furniture pieces such as a sitting bed and reclining rests as well as lacquer wares including tables, serving trays, and drinking cups. It is in this west chamber that the “Mirror” was found, near the western wall of the west chamber, facing downwards and broken into pieces.Footnote 28

The Object: The “Mirror”

This intriguing object has attracted a great amount of attention, in particular among scholars of Confucian tradition and dynastic history in the Han. The presence of the earliest portrait of Confucius and seven of his disciples, as well as excerpts of their biographies that largely overlap with those in the Grand Scribe's Records (Shiji 史記), has excited many, who consider the inscriptions a new textual trove. Others have also compared the lacquer-painting techniques deployed in the rare and full-body colored portraits of the most celebrated Confucian figures.Footnote 29 Historians are also quick to contextualize this unusual object in the unique history of Liu He's short but tumultuous life. There are two main theories with regard to how this “Mirror” sheds light on nuances and details about Liu He, which the dynastic history may have had intentionally concealed or distorted. Both theories address the official allegations about Liu He's moral shortcomings and the deviant behaviors that led to his downfall after only twenty-seven days on the throne. One theory argues for rectifying Liu He's reputation—in life and in the afterlife—in light of what now have been found in his tomb. In the simplest terms, this view suggests that Liu He must have been deeply immersed in, or at least exposed to, Confucian learning, which should have been a good guardrail against those alleged immoral and lewd behaviors. Echoing those who have suspected that Liu He's deposition was a political plot of the kind commonly seen in Han court politics, Liu He's burial and entombed goods such as those Confucian classics found in the “Library/Archive” and this “Confucius Dressing Mirror” now provide the material support for repudiating that official account.Footnote 30 The other theory suggests that the heavy Confucian component of Liu He's burial may indicate that Liu He sought refuge in Confucian moral self-cultivation after his removal from the throne, either for self-protection under the surveillance of the court,Footnote 31 or because of a sincere intention in some kind of personal redemption, self-imposed or otherwise.Footnote 32

Regardless of the debates surrounding certain textual and visual analyses, or even the methodological soundness of the somewhat simplistic revisionist arguments, which cannot be fully addressed here, there are two problematic aspects of the current view of the “Mirror” unearthed from Liu He's burial. First, the single-minded focus on the portraits and biographies of Confucius and his disciples overlooks a plain fact that they are only part of an object that is an assemblage of multiple components. Not looking at the object holistically, and more importantly, failing to recognize that this “Mirror” is first and foremost a physical object, not a text that exists without a medium, risks mischaracterizing and misinterpreting not only the object as a whole but also the texts inscribed on them. Second, directly related to and to some extent a result of the first point, those who interpret the function of the “Mirror” as a teaching or self-cultivation instrument used in Liu He's life neglect to ask how it was actually used and why it was buried in the tomb. The current theories unfortunately selectively use only part of the object in their argument, and they take its presence in the burial as a matter of fact without addressing the funerary process that brought it to the tomb.

My following discussion revisits the contextualized object in light of these concerns. I will first introduce all the components of the “Mirror,” in the process of which I will also raise questions about this designation. Instead of focusing on the images and biographical texts of the Confucian figures, I will center my analysis on an inscription of rhymed prose, dubbed by the excavators the “Dressing Mirror Rhapsody” (衣鏡賦), found on the front cover of the “Mirror.”Footnote 33 Unlike the biographies of Confucius and his disciples, this short inscription actually contains a few hints about the fashioning and function of the object. I will conclude by proposing a hypothesis about how this object may have come to be included in Liu He's burial.

The Contextualized Object: Materiality

The “Mirror” was found near the middle of the western wall in the west chamber, facing the doorway that leads to the east chamber where Liu He's coffins were placed (Figure 5). This location may not be accidental and I will return to it later in the discussion. It was found facing down, broken into pieces. However, it is unclear in the preliminary report whether this was the original placement and deposition manner of the “Mirror,” or the facing-down and broken condition occurred after the tomb was closed.Footnote 34

Figure 5 Location of the “covered mirror” found inside the burial chamber of Liu He's Tomb, modified after the 3D Reconstruction, courtesy of Yang Jun, Jiangxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology

A preliminary restoration by the excavators shows that it has two principle parts: a rectangular bronze panel (the “dressing mirror”) and a rectangular wooden frame with an openable front cover and a fixed backboard. The frame, the cover, and the backboard were all painted. The portrait of Confucius was found on the exterior of the backboard. Its initial identification as a pingfeng screen was because of the rectangular shape and the painted fragments of the wooden panel. On the surface it shares these common features with some excavated specimens that have been identified as screens from several Han tombs such as two color-painted lacquer-wood screens from the famous early Western Han Mawangdui 馬王堆 tombs (Figures 6a–b)Footnote 35 as well as one large full-body-sized standing screen from the tomb of Zhao Mei 趙眜 (r. 137–ca. 122 BCE), the second King of the Nanyue Kingdom 南越.Footnote 36

Figure 6a (front) and 6a (back) A color-painted lacquered wooden screen from Mawangdui M1 (M1:447), photos after Hunan Provincial Museum (http://61.187.53.122/collection.aspx?id=1389&lang=zh-CN)

The subsequent discovery of the self-referential phrase, yijing, in a rhymed text inscribed on a fragment of the front cover prompted the archaeologists and historians to revise their initial identification of a “screen” to a “dressing mirror.” It may be because of the size and weight of the bronze panel that the excavators also hypothesized that for it to properly function as a “dressing mirror,” the framed “Mirror” might have originally been mounted on a stand (Figure 7).Footnote 37 It should be noted, however, that there is no stand or any trace of a stand found together with or near the broken pieces of the “Mirror” in the tomb. Possible explanations for the absence of the assumed stand have been proposed, ranging from the stand not having been included in the burialFootnote 38 to its having degenerated because it was made of perishable organic materials. The latter explanation is belied by a large number of well-preserved objects made of wood and bamboo in the same tomb under the same preservation conditions. The “missing” stand is not the only peculiar or “odd” aspect of this object, nor can the current identification of it as a “dressing mirror” fully account for its possible genesis and its placement in the tomb of Liu He.

Figure 7 The proposed reconstruction of the “Dressing Mirror” with a stand, modified after Nanfang wenwu 2016.3, 62, fig. 4

Let me begin with the details of the bronze panel (Figure 8a). It was a large rectangular bronze plate, broken in the middle at the time of the discovery. The restored measurement is (L)70.3 x (W)46.5 cm. The thickness of the panel is 1.3 cm with a slightly thinner edge at 1.2 cm. The unpolished backside of the bronze panel has five semi-circular knobs, measuring (L)3.8 x (W)2.0 x (H)1.8 cm. It weighs 20.048 kilograms.Footnote 39 The excavators suggest that these knobs were used to mount the bronze panel onto the wooden frame.Footnote 40 Although the exact mounting mechanism is not explained, one can observe what seem to be impressions left by the knobs being pushed into the interior of the restored backboard (Figure 9a). There are also two bronze rings, one attached to each side of the wooden frame (Figure 9b), which the excavators hypothesize may have been used to mount the framed “Mirror” onto a now-missing stand, as demonstrated in their proposed reconstruction (Figure 7). The excavators give no specifics as to how to mount a heavy and framed bronze panel using only these two small and slim rings. These technical questions are relevant to understanding the nature and the function of the “Mirror,” and a full restoration in the future may clarify these remaining questions.Footnote 41

Figure 8a The Haihunhou bronze panel (broken in the middle when found), modified after Nanfang wenwu 2016.3, p. 61, fig. 2, courtesy of Yang Jun, Jiangxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology

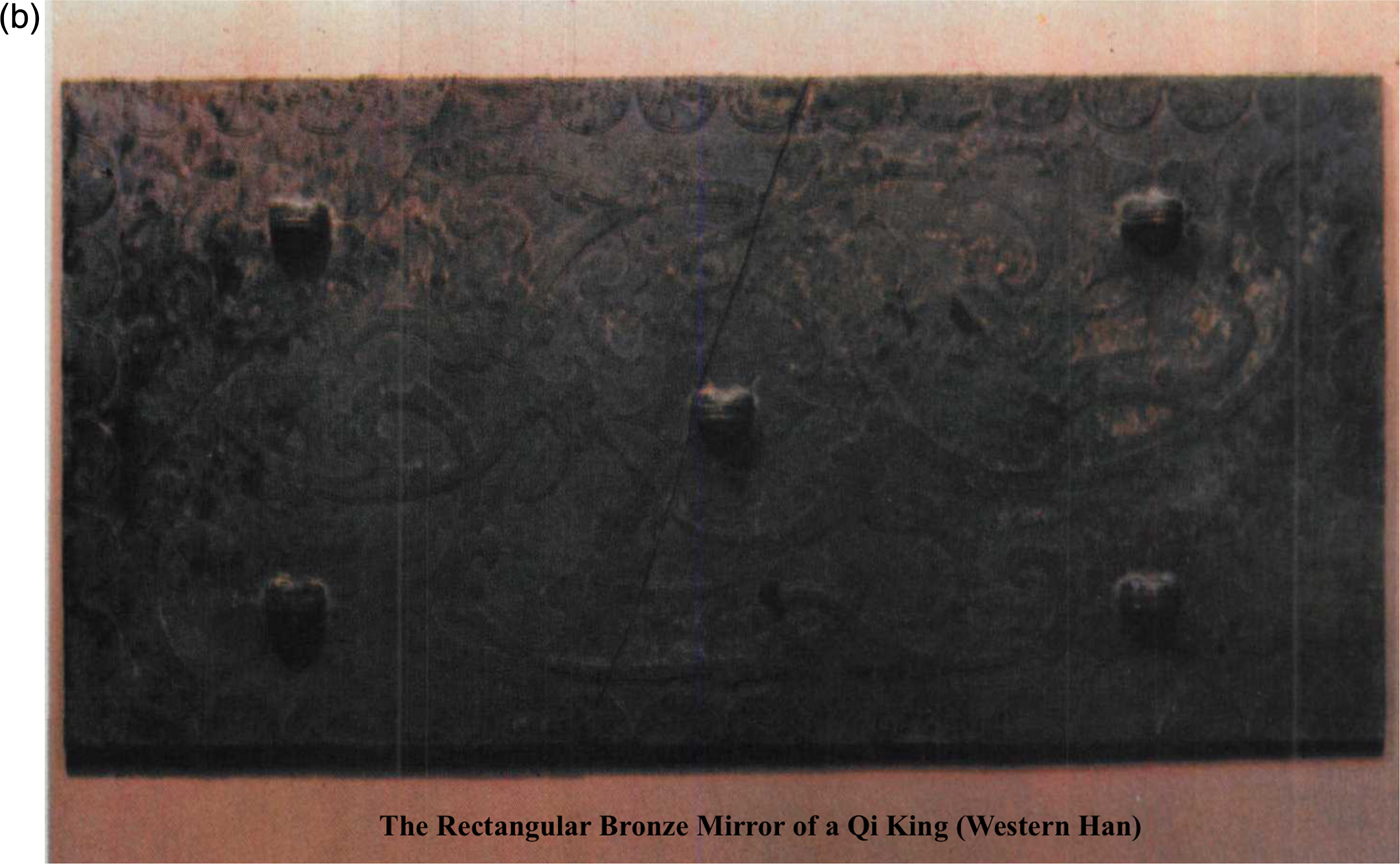

Figure 8b The Qi King's bronze mirror (back), modified after Kaogu xuebao 1985.2, Color Plate 13.1

Figure 9a The restored wooden frame (painted front side) and the backboard showing the interior side, after Wenwu 2018.11, 82, fig. 1, courtesy of Yang Jun, Jiangxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology

Figure 9b The restored wooden frame (backside) and the backboard showing the exterior side (Upper left: Portrait of Confucius), after Nanfang wenwu 2016.3, 63, fig. 7, courtesy of Yang Jun, Jiangxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology

Although Han hand-held bronze mirrors are common in archaeological finds,Footnote 42 such large-size and rectangular-shape bronze mirrors are rare. The only other known specimen was found in 1980, in an external storage pit for the burial of a certain king of the Qi 齊 Kingdom in Western Han near Zibo 淄博, Shandong (Figure 8b).Footnote 43 It was identified as a bronze mirror and curiously also found broken into two pieces approximately in the middle. By comparison, it is both larger and more than twice as heavy, measuring (L)115.1 x (W)57.7 x (H)1.3 cm and weighing about 56.6 kilograms. Coincidentally, it also has five similarly arranged semi-circle knobs (5 x 3.5 x 3.2 cm) on the backside. However, the backside of the Qi mirror was decorated in exquisite patterns of dragon and persimmon petals,Footnote 44 while that of the Haihunhou bronze panel is plain without any décor. Unlike the Haihunhou bronze panel, which was found together with a wooden frame and inside the burial chamber, the Qi mirror was found alone without any frame or stand, and it was found in a storage pit outside the tomb. These differences raise the question about whether the fact that the Haihunhou “Mirror” seemed to be framed and was placed inside the burial chamber in an area considered by some as the underworld equivalent of a sitting-room in the world of the living, bear any significance beyond a mere idiosyncratic choice.

Differences aside, the fact that the only other known large-size rectangular bronze mirror was found in Shandong is worth noting. Liu He's father was the first King of Changyi, a kingdom located in present-day Juye 巨野, Shandong. Liu He lived there before he went to Chang'an in 74 BCE, and he was sent back to Shandong after he was deposed. When he was relocated to Yuzhang (present Jiangxi) in 63 BCE, he must have moved his properties, many of which inherited from his father, from Shandong to Jiangxi. In Liu He's tomb, there are indeed many lacquer ware fragments, musical instruments, and some bronze vessels that bear the manufacture inscription of Changyi.Footnote 45 Against this background, and given the physical resemblance of the two bronze panels, it is worth considering the possibility that the Haihunhou bronze panel may have been made in Shandong and brought with Liu He when he was relocated to Jiangxi. In other words, although it is unclear how such a large and heavy bronze panel was actually used as a mirror, it seems reasonable to surmise that this bronze panel might have been made long before Liu He's death.

An anecdote about a large bronze mirror used by the First Emperor of Qin (r. 221–210 BCE), recorded in the fourth-century CE Xijing zaji 西京雜記, sheds some light on the nature and usage of large bronze mirrors. The story tells that such a mirror was found in the Qin palace in Xianyang 咸陽 by the future High Emperor of Han 漢高祖, Liu Bang 劉邦 (r. 202–195 BCE). It is described as follows:Footnote 46

There was a rectangular mirror, four-chi wide (c. 92 cm), five-chi and nine-cun tall (c. 135.7 cm). Both sides were reflective. When people faced it directly, it reflected them [upright], but the shadow of people was reflected upside down. If [one] placed the hands over the heart, then [one could] see [his or her] intestines, stomach, and five internal organs clearly without any hindrance. If people had a sickness inside, then once they placed their hands over the heart and looked at their reflection in the mirror, then they knew where the sickness was. Moreover, if a woman had nefarious intentions, then her gall bladder would be open and her heart moving [in the reflection in the mirror]. The First Emperor of Qin often used [this mirror] to show the reflection of the palace ladies. Those whose gall bladder was open and heart moving would be executed.

有方鏡,廣四尺,高五尺九寸,表裏有明,人直來照之,影則倒見。以手捫心而來,則見腸胃五臟,歷然無硋。人有疾病在內,則掩心而照之,則知病之所在。又女子有邪心,則膽張心動。秦始皇常以照宮人,膽張心動者則殺之。

Although the account is anecdotal and was included in a post-Han text associated with Ge Hong 葛洪 (283–343 CE), a polymath interested in mantic practices including alchemy, it may be informed by earlier beliefs and practices. At the least this story provides another perspective to consider the possibility that such a large and rectangular bronze mirror may be primarily of a talismanic nature, in addition to the two other commonly conceived functions of regular, especially hand-held, mirrors. One is the apparently utilitarian function of being a “dressing mirror.” The other is the conventional symbolism of mirror for self-reflection in personal and moral cultivation, such as expressed in the words of a Confucian scholar, Xun Yue 荀悅 (148–209 CE), “A morally noble person (junzi) has three reflections, reflecting in the ancient, reflecting in the others, and reflecting [in the self-image] in the mirror” 君子有三鑒,鑒乎前,鑒乎人,鑒乎鏡.Footnote 47 In order to decide the intended function of this entombed object, we also need to look at the frame set.

All three parts of the wooden frame set—the rectangular frame, the front cover, and the backboard—were lacquer-painted. The rectangular frame, painted in red, was made of solid wood planks, and the restored exterior measurement is (L)96 x (W)68 x (T)6 cm, and the interior measurement is (L)72.4 x (W)44.4 cm. The excavators found two small lumps of metal remains on the top beam of the frame that they suspected to be used to attach the frame to a stand. Inside the frame (location not specified), it is reported that there is a bronze bolt with which the excavators thought to have been used to fix the bronze panel via the knobs on the back when it was inserted.Footnote 48 Recalling the reported size of the bronze panel, (L)70.3 x (W)46.5 cm, if all these published measurements are accurate, then it seems that the frame and the bronze panel were not fitted seamlessly.

The Contextualized Object: Visuality

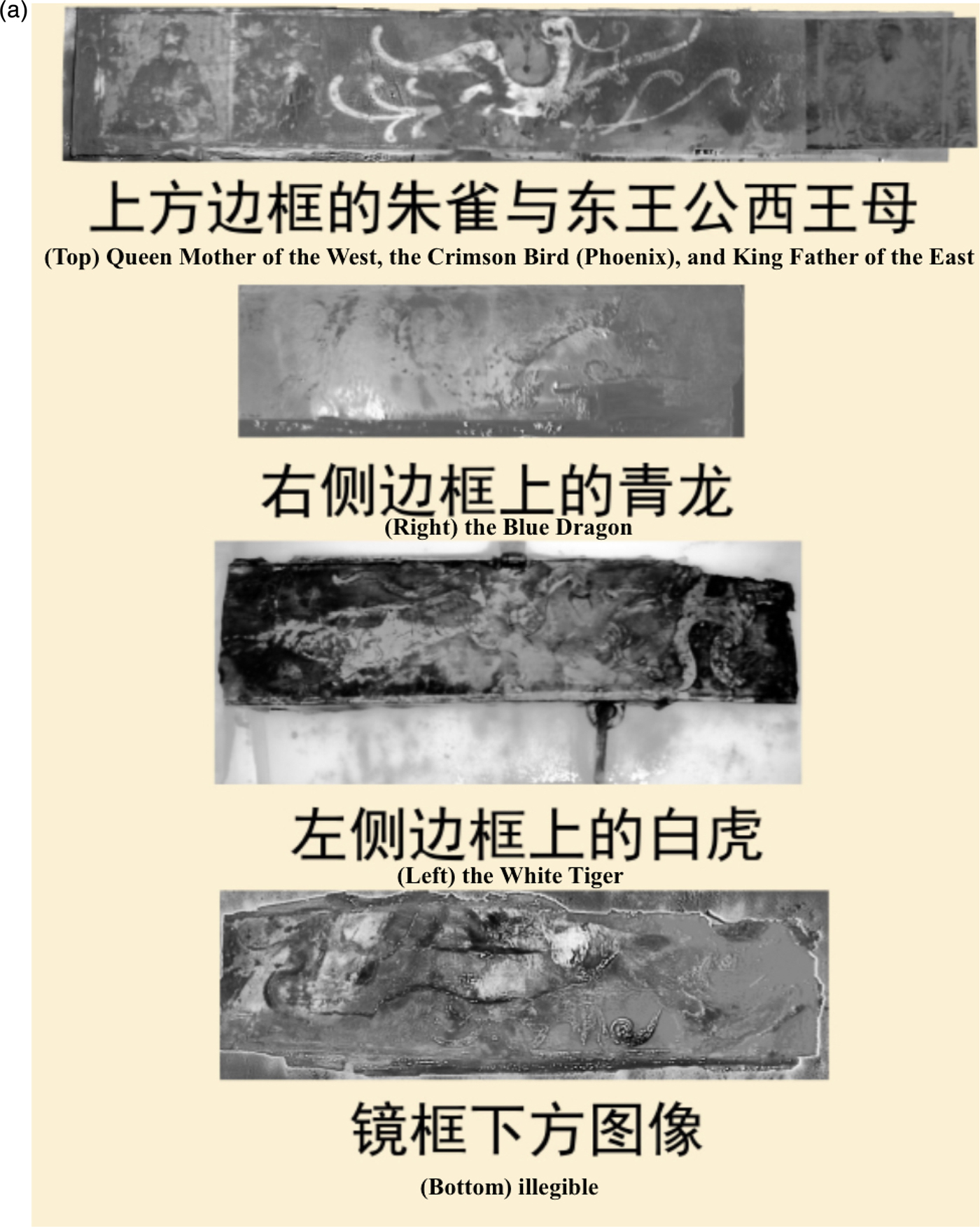

On the front side of the frame, all four facades were painted (Figures 10a and 10b). Based on both the iconography and the description in the aforementioned “Dressing Mirror Rhapsody” (Figure 11), they have been identified, from the perspective of the viewer, as follows: on the top beam, from left to right, Queen Mother of the West, the Crimson Bird (Phoenix), and King Father of the East; on the left beam, the White Tiger; on the right beam, the Greenblue Dragon. The image on the bottom beam is illegible now, but the inscription has it as the “Dark Crane.”Footnote 49 The mythical animals of the Four Directions—the White Tiger, the Greenblue Dragon, the Crimson Bird, and the Dark Xuanwu (a hybrid of a snake on top of a turtle)—as well as the immortal couple of the Queen Mother of the West and the King Father of the East were popular pictorial themes on Han bronze hand mirrors as well as in the Han tomb murals.Footnote 50 Their associations with otherworldly realmsFootnote 51—the immortal land or the afterlife world—and their perceived protective powers were also well documented in the Han.Footnote 52

Figure 10a Infrared Scans (IR) of the four front sides of the wooden frame, modified after Nanfang wenwu 2016.3, 62, fig. 6, courtesy of Yang Jun, Jiangxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology

Figure 10b Color Images of the “Queen Mother of the West”(left), “King Father of the East” (right), and “Crimson Bird”(middle) on the top beam of the wooden frame, after Wenwu 2018.11, 83, fig. 2, courtesy of Yang Jun, Jiangxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology

Figure 11 A rhymed inscription, dubbed by the editors the “Dressing Mirror Rhapsody,” after Nanfang wenwu 2016.3, 64, fig. 10, courtesy of Yang Jun, Jiangxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology

Both the front cover (exterior and interior) and the backboard (exterior only) were painted with images and inscribed with texts. The portrait of Confucius was painted on the exterior of the backboard. The whole panel was first outlined at the edges with bright yellow lines, and two more yellow lines divide the area within the outline into three vertical registers, each containing two full-body portraits of two persons, standing face to face. Each person is identified by a cartouche with the name of the person in it and a short biographical text. Confucius ((H)28.8 x (W)8.4 cm) is on the left side of the upper register; facing him was his favorite disciple Yan Hui 顏回 (Figure 9b). The middle register has Zigong 子貢 on the left and Zilu 子路 on the right. The bottom register has Tangdai Ziyu 堂駘子羽 (a.k.a., Tantai Mieming 澹台灭明) and Zixia 子夏. With the exception of Confucius, whose full body was filled in color, the bodies of his disciples were outlined but not color-filled.Footnote 53 Their biographies are largely identical to those in the Shiji with some textual variants and minor differences.Footnote 54

The front cover was badly damaged, broken into several tens of smaller pieces, so the current restoration is tentative. Unlike the backboard, which was only painted on the exterior, the cover was painted on both sides. This may be because as a cover, it was openable via the two hinges fixed on the left side. However, the interior images and texts are barely legible now. Only in what would be the middle register, one can see two heads. The one on the left seems to be Zizhang 子張 and the one on the right, Zengzi 曾子. Only part of Zizhang's biography remains legible, and nothing can be read of Zengzi's.Footnote 55

The placement of the portraits of Confucius and his disciples as well as their biographies is curious.Footnote 56 What modern scholars consider as the most important of these Confucian figures is undoubtedly Confucius, evidenced in the now widely accepted designation, “Confucius Dressing Mirror.” But the portrait of Confucius was actually painted on the backside of the “Mirror.” This raises a practical question for those who argue for this “dressing mirror” doubling as an instrument of teaching and self-reflection for the intended user, in this case, Liu He. For example, Wang Chuning argued that this mirror would allow Liu He to “self-reflect in the image and in history” (tushi zijing 圖史自鏡). Specifically, he explained, when Liu He was looking into the mirror, he would be able to see himself in the front side of the mirror, but on the backside of the mirror, he would see the images and read the deeds and words of Confucius and his disciples, which he was expected to compare to his own so that he could follow the teachings to “thrice reflect upon myself” (三省吾身) and “strive for being an equal when seeing a worthy” (見賢思齊).Footnote 57 Strictly speaking, this would require Liu He either to turn the framed “Mirror” around to see the images and words about Confucius on the backside or to walk to the back of the “Mirror.” This makes one wonder why the most important figure, Confucius, is not placed on the front side of the cover, or better, on the interior of the front cover which would conveniently allow Liu He to see the image of the sage and the text about his life side by side with his own reflection when he opened the cover to reveal the reflective side of the mirror. Additionally, in order to make all the portraits and texts accessible and visible to the potential viewer, this framed “Mirror” needed to be placed in the middle of the room or at least with enough room behind it for access to the back where the majority of the figures and texts were placed. This is certainly not inconceivable or impossible to arrange; however, I raise these practical questions to highlight the importance of considering all the components of this object—an assemblage to be precise—and taking into consideration their physical features and spatial relations in order to ascertain the object's intended use and function. Looking at it this way, it becomes clear that this “Mirror” is not just about the images and biographies of Confucius and his disciples.

The Contextualized Object: Textuality

Let us take a closer look at the exterior face of the cover and reconsider the other images—the mythical animals and the immortal couple of the Queen Mother of the West and King Father of the East—on the front side of the frame. Because the cover has been severely damaged, not all the images painted on the external side are recognizable. One fragment seems to be a portrait of Zhong Ziqi 鍾子期, identified with the inscription “Zhong Zi listening to it” (鍾子聽之),Footnote 58 a figure from a well-known tale about music and friendship popular in Han times.

Another fragment bears what the excavators now call the “Dressing Mirror Rhapsody,” a rhymed text that seems to be relatively complete, with the exception of the last few lines (Figure 11). This inscription is the source of the phrase yijing, which excavators and scholars have taken at face value to label the object. However, taking yijing out of context has actually obscured the nature and function of a clearly composite object. In my view, this rhymed text as a whole provides valuable hints at the production and the intended function of the object. For this reason, it warrants a full translation here:Footnote 59

The inscription follows a clear order in its description of the framed “Mirror.” It begins by praising the overall fine quality of its making (1). Then it moves to describe the images on the front cover (2), the images on the frame (3), and the images on the backboard (4), emphasizing repeatedly in each section the power of these images to help people avoid harm and misfortune and obtain blessing and happiness. It concludes with commendation, using stock phrases wishing for long-lasting blessing and joy for the family and generations to come (5). Although the inscription does make one passing reference to “refining the appearance” in section (1) and mentions Confucius and his disciples in section (4), it is clear that they are only part of an overall message that this inscription emphatically attempts to convey. That is the ritual potency of the said object, including but certainly not limited to the Confucian images, to ward off troubles and afflictions and to bring blessing, tranquility, and long-lasting joy. The unabashed tone with which it extols its own benefits finds company in some inscriptions on Han hand-held bronze mirrors, which Anthony Barbieri-Low deemed “advertisements.”Footnote 64 For example, a bronze mirror with a date of 145 CE bears an inscription that partly reads:Footnote 65

I have harmoniously combined the three auspicious metals,

And refined the white [tin] and the yellow [copper] according to a secret formula.

As brilliant as the sun or the moon, its reflection enables one to see the ends of the earth.

It will enable one to extend his life and have eternal happiness without end.

For one who buys this mirror, may his family become rich and prosperous.

May he have five sons and four daughters, and may they all become [or marry] marquises and princes.

For one who buys this mirror secondhand, may he occupy a prominent place in a large market.

May his family acquire a good name … [fragmentary, unclear passage].

Another mirror dated to late second or earlier third century CE has a similar inscription:Footnote 66

Mirrors made by Shangfang are really all the rage.

On them are immortals who know nothing of old age.

If parched, they drink of jade; when hungry, sup on dates.

They rove about on the hills of the gods, plucking fungus and herbs that are blessed.

Long life to you, longer than metal or stone or even the Queen of the West.

Barbieri-Low noted that the language used in these what he called “magico-auspicious” jingles are “similar in form to popular rhymes and magical incantations” in the Han. He argued that such mirror inscriptions served a dual purpose as both “advertising slogans” and “religious texts” to persuade and please the customer.Footnote 67 Although these two inscriptions, like the vast majority of extant examples, were for hand-held mirrors, the similarity between their rhymed “jingles” and this elegantly composed “Rhapsody” are striking, especially the emphasis on the apotropaic power of the images on them as integral to the efficacy of the object, which clearly goes beyond the utilitarian function of a regular mirror that simply reflects physical appearance. This reading of the “Dressing Mirror Rhapsody” effectively shifts our attention from the moral and educational use that it held for its owner and user, Liu He, to its maker and the making of a talismanic object with characteristics of a commodity.

In this light the first line in the inscription begs further scrutiny. At first glance, “the newly completed covered mirror” certainly may be read as a direct and simple self-reference to the very object as a regular “mirror,” as it is currently understood. However, the curious wording “newly completed” may also be understood as referring to the particular making of the entire assemblage. It is not beyond the realm of possibility that the “covered mirror” may be “newly completed” in the sense that the frame set was added to the bronze panel, which produced the final composite object that we see now. Two previously made observations may strengthen this hypothesis. One is that the Qi king's mirror was found without a frame in a storage pit, suggesting that this kind of large-size rectangular bronze panel could be a stand-alone object. In contrast, the Haihunhou “mirror” was placed inside the burial chamber, facing the doorway leading to the coffins of Liu He. This particular location corresponds provocatively to the line in the inscription, “Powerful beasts and fierce animals [on it] protect the doorway and the chamber.” Additionally, our earlier note about the less-than-perfect physical fit between the frame and the bronze panel may also indicate that the frame was not finely made or intended to be actually assembled with the bronze panel. This reminds us of the various ways mentioned in the Xunzi that funerary objects, or what Xunzi called mingqi 明器, are rendered incomplete or with the appearance of the objects without their full utility.Footnote 68

Concluding Remarks

When the excavators published their introductory report and analysis about this intriguing object, they made two points that require revision. One is the naming of the object as “Confucius Dressing Mirror.” The other is the suggestion that this “Mirror” originally may have been mounted to a stand, which was not included or had gone missing in the tomb. As the analysis above makes clear, both the designation and the reconstruction are premised on the understanding that the Confucian portraits and the biographical texts are central to the identification of object, and that the “Mirror” was used in Liu He's life as a teaching and self-cultivation device.

My reading of the complete assemblage as a talismanic object that may have been a “newly completed,” composite specifically for funerary purposes and ritual functions in the afterlife, differs significantly from the existing theories introduced earlier. I argue that despite the historical and artistic value of the Confucius’ portrait and the biographies to historians today, calling the object “Confucius Dressing Mirror” is misleading. The images of Confucius and his disciples were popular themes that were often seen on Han artifacts and in tomb reliefs, along with the mythical animals and the Queen Mother of the West and her divine counterpart, the King Father of the East.Footnote 69 These pictorial motifs and narrative tropes certainly reflect the broader cultural orientations and artistic tastes of the time, but their particular presence should be first and foremost considered and interpreted in their immediate material context.

In this case, it seems that the image of Confucius and his disciples are best read according to the rhymed inscription as integral to the propagated magical power of the object to bring tranquility and harmony with the cosmic order to its owner, which is not necessarily mutually exclusive from self-cultivation, broadly defined, but was not independently endowed with such power. As for the “missing” stand, if my hypothesis about the composite making of the “covered mirror” holds, and the frame set was produced for interment only, there may have been no need for such a stand. This being said, the two small bronze rings on the frame, which partly prompted the proposed reconstruction of a “standing mirror,” are curious, even though the exact mechanism of using these two flimsy-looking rings for mounting such a heavy set remains unclear. If there was indeed a stand which was not included in the burial, it may be one of the rare cases in which a funeral modification needed to indicate the “relocation” of the deceased from the living world to the realm of the dead, as articulated in the Xunzi, was made in an archaeologically visible manner.

In the final analysis, the key point that I try to convey is a methodological one. I highlight and address the importance of a contextual approach to entombed objects that pays attention to the material composition and the location and arrangement inside the burial, as well as to the need to reconstruct the trajectory of the relocation of funerary assemblage from the living world to the realm of the dead in the process of funerary rituals. The “Mirror” is an enigmatic object that cannot be completely understood given the present state of our knowledge. There are indications that it may have been made long before Liu He's death, rendering it a “lived object” (shengqi), but there are also indications that it was newly assembled for the burial chamber, rendering it a “funerary object” (mingqi). It is my hope that future research may reveal the extent to which the archaeologist's categories of analysis are themselves in need of revision.

Acknowledgements

I thank Dorothy Ko for her invitation to contribute to this special issue on material culture as well as for her incisive comments and unwavering support throughout the writing process. I also want to express my sincere gratitude to Yang Jun 楊軍 of Jiangxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology, the leading excavator of the Haihunhou site. He not only provided the necessary access and critical support to the Haihunhou site and the excavated materials, but also generously allowed me to use the images and figures of the Haihunhou finds in the article. Liu Yong 劉勇 of The University of Science and Technology (Beijing), who was working at the conservation center at the Haihunhou site, warmly guided me through the indoor excavation sites and shared his firsthand experience and insights of the entombed objects during my visit in 2017. The anonymous reviewers have provided constructive comments and suggestions that have improved the clarity of the article. All remaining mistakes are mine alone.