Introduction

On May 4, 1960, anthropologist Arthur P. Wolf's Taiwanese research assistant MC observed this episodeFootnote 1 of a brother–sister dyad interacting with another child in a Hoklo village (Xia Xizhou下溪洲) near Taipei:

Bai Yanyan (a seven-year-old girl) was standing in front of a rock with food on it. Lin Yikun (a seven-year-old boy) was in a hurry to go away and stuck a paper package into Yanyan's hand and said: “Here is some face powder [for pretend play]. I give this to you.”

Yanyan: “Alright.” She took it.

Yikun: “You have to let my [younger sister] Meiyu play with you.” Yikun turned and ran off.

His sister Lin Meiyu (five-year-old): “You let me play with you, alright?”

Yanyan nodded her head. She put the powder package under the rubber band that was holding her purse closed.

Meiyu had a little cosmetic box in her hand. Yanyan took it from her and said: “We'll put this in my purse, alright? We'll put it with all my other things.”

Meiyu nodded her head in agreement. (MC)

Blending elements of kinship, friendship, gender, and age, this ethnographic observation provides a glimpse into young children's moral life and power dynamics: The young boy Yikun “bribed” his peer Yanyan with the explicit goal of getting Yanyan to accept his little sister Meiyu as her playmate. Yanyan accepted Yikun's gift—a popular play object among young girls in the community—as well as his accompanying request. Perhaps benefitting from her seniority in age or her position as the desired playmate, Yanyan also took the initiative to lead the subsequent interactions, commanding the control of resources upon Meiyu's agreement. Above all, we see a little boy helping his younger sister to make friends with peers, in a social world outside the home, through exchange of gifts and favors.

This article aims to understand learning morality with siblings: How do young children learn their first lessons about relating to others and asserting oneself, about cooperation and conflict, about negotiating parental control, and about the power of authority, through interaction with their siblings, in peer and family contexts? The opening vignette is just one among nearly two thousand observational episodes about these Taiwanese children's social life in an archive left behind by the late anthropologist Arthur Wolf, which I call “the Wolf archive.” Young children are “the most blatant, intellectually innocent, and professionally overlooked among the unrepresented” people in historiography.Footnote 2 As Arthur Wolf himself stated in a draft manuscript: “Until recently Chinese scholars have had no interest in writing naturalist accounts of Chinese children.Footnote 3 The older literature is entirely prescriptive in the manner of the famous Tales of Filial Piety. Western travelers and missionaries sometimes mention children in relating their experiences, but these are typically brief and prejudiced.”Footnote 4 His precious field-notes offer a unique opportunity to understand the lives of children in rural families at the margins, children whose stories would otherwise unlikely figure into historical sources and accounts.Footnote 5

Examining these children's world also helps to remedy a problem in today's socio-cultural anthropology. If lack of direct access to the world of the young contributed to the relatively marginalized status of children in historical representations, the problem with anthropology is perhaps of a different nature: the reluctance to recognize children's critical role and unique capacity in the acquisition, transmission, and creative transformation of socio-cultural knowledge.Footnote 6 In the plentiful ethnographic research about “the Chinese family,”Footnote 7 anthropologists have often encountered children, especially in the past: when anthropologists were doing village ethnographies, children were running around everywhere in a village.Footnote 8 They have rarely placed children, by which I mean the actual experience rather than the representation or discourse of children, at the center of analysis.Footnote 9 If anything, in the eyes of anthropologists, and similarly for those adult interlocutors in anthropologists’ fieldwork, young children are no more than passive objects of Chinese moral discourse,Footnote 10 especially that around filial piety.Footnote 11 One of the most visible changes in family and kinship in contemporary China is the emergency of child-centered families,Footnote 12 especially in urban China, since the One-Child Policy and, more recently, in the context of continued low fertility even after the loosening of family planning policies.Footnote 13 Childrearing has become a central topic for current ethnographic inquiries, but the majority of these works focus on the discourses and practices of “rearing,” featuring the adult perspectives rather than those of the child.Footnote 14 Children's worlds are overlooked. They silently lie in the shadows of parent–child ties. This might reflect a general bias in social science, “the nurture assumption” as psychologist Judith Harris diagnosed, which overemphasizes the impacts of parenting on child development.Footnote 15 The problem is more acute in socio-cultural anthropology, though, due to its persistent hostility to psychology and the resultant unwillingness to engage with research on children's cognitive development.Footnote 16

Lacking awareness of and attention to children's agency, and prioritizing parenting beliefs and socialization strategies, the anthropology of the Chinese family since its inceptionFootnote 17 has obscured an important dimension of learning: peer learning. In particular, this scholarship has neglected a crucial aspect of the peer-learning experience: sibling relations. Classic works, shaped by British anthropology's lineage studies traditions, rarely focused on siblings as children, only on brother–brother rivalry as adults.Footnote 18 Later research, inspired by the new anthropology of kinship that takes the lived experience of “relatedness,” instead of formal structures, as a central concern, has still paid little attention to sibling experience.Footnote 19 There are a few exceptions, such as studies on young adulthood, such as “same-year siblingship” (fictive kin, friendship)Footnote 20 and elder sister's sacrifice and support for younger brother in rural China.Footnote 21 This reflects a broader problem in the new anthropology of kinship—the neglect of sibling relations, a problem related to the bias in favor of the centrality of parent–child and conjugal relations.Footnote 22

The existence and co-residence of siblings, however, has persisted over most of human history. Across many cultural communities, instead of having adults supervise and teach them, children spend a lot of time playing with and learning from other children, and siblings are important agents in such peer learning processes.Footnote 23 As cross-cultural research on child development has long demonstrated: “Siblings always matter.”Footnote 24 From an evolutionary perspective, sibling experience in childhood is a key component in human kin detection,Footnote 25 of which Arthur Wolf's research on Taiwanese sim-pu-a 媳婦仔 (“little daughter-in-law”) Footnote 26 remains a classic case. For socio-cultural anthropologists, sibling relations, especially cross-sex siblings, are constructed simultaneously as equal (shared parenthood) and as different (age, gender, birth order).Footnote 27 Exploring sibling relations in childhood can help us understand the double-edged quality of human kinship: love and control, connection and exclusion in the practice of relatedness.Footnote 28

This article tells the story of a brother–sister dyad, the main characters in the opening vignette. Their family was featured in Margery Wolf's A Thrice-told Tale,Footnote 29 but what happened to the children remained a mystery. This intrigued me. Through new theoretical lenses, analytical techniques, and, inevitably, my own interpretations, I re-covered and re-discovered the once untold tale of a brother–sister dyad. Telling their story, I highlight the moral agency of the least-studied members of the human family––young children. I focus on siblings, arguably the most obscured relationship in the study of Chinese families.

The wolf archive: history, theory and methods

The late sinologist and anthropologist Arthur Wolf conducted more than two years of dissertation fieldwork (1958–60), in a Hokkien-speaking village in Banqiao district 板橋鎮 near Taipei.Footnote 30 His research team included Margery Wolf and several Taiwanese research assistants, and they lived with the “House of Lim.” The Lim (林 Lin, pseudonym) family was the most prestigious family in the village, and the only big, joint family compared to the rest of nuclear or stem family households.Footnote 31 The village at that time had a total population of around six hundred, including more than two hundred children. The majority of villagers descended from southern Fujian Chinese migrants who had settled in the area during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and some other villagers who had moved to the area more recently. It was during the era of KMT martial law, on the eve of massive industrialization, urbanization, and fertility decline. In the golden age of “China” ethnography, motivated by the quest of understanding “Chinese” society, the Wolfs were not concerned about their villagers’ own identity.Footnote 32 But most villagers were Taiwanese 本省人, adults speaking a mixture of Japanese and Hokkien, children speaking Hokkien in the village and learning Mandarin at school as part of their compulsory education. In terms of economic prospects, most families were still poor by local standards, with a mixture of farming and factory work income: average daily earnings were 20–30 yuan (NT) for men, 15–20 for young men, and 7–10 for women. They were not equally poor though. The House of Lim (Lin) had the highest standing, distinguished by the largest house with all-brick walls and concrete floors (two rooms even with terrazzo floors), while others had smaller houses with brick-walls or mud-brick walls.Footnote 33

Today the Wolfs’ field-site is no longer a village, but part of New Taipei City 新北市. Once known under the pseudonym Peihotien, however, this village remains an iconic landmark in the map of sinological anthropologists,Footnote 34 thanks to the two anthropologists’ seminal works on marriage, kinship, women, and gender.Footnote 35 Less known to many, however, the Wolf's Xia Xizhou 下溪洲 project was the first systematic, anthropological research on Han Chinese children and childrearing in the world. With the target population of children ages 3 to 12, it triangulated multiple research methods: 1) naturalistic observations of children's social interactions at home, inside the village, and at the elementary school outside the village, including three types, timed Child Observation, Situation-based Observation, and Mother Observation; 2) standardized interviews with children and mothers; 3) projective tests––a popular method in psychology at that time, using culturally appropriate prompts for story-telling, i.e., dolls in Doll Play, pictures in TAT (Thematic Apperception Test), to elicit children's understandings and feelings about interpersonal relationships; 4) a survey of infant care and mother–infant interactions (Baby Survey). All the fieldnotes were indexed by the event information (date, time, location) and by the participants’ ID numbers. In addition, the archive preserves comprehensive demographic and household information for all the children and their family members. As Arthur Wolf stated in his 1982 NSF project summary: “We should emerge from analyzing these data with dramatically greater systematic knowledge about Chinese childhood than we have ever had before.”Footnote 36

From the original data collection to my re-analysis and writing, this journey involves multiple layers of transcription, translation, and interpretation. Under Arthur Wolf's supervision, his two Taiwanese research assistants, initials MC and MS, collected most of the observational and interview data. In their late-adolescence, these two women lived with the Wolfs, spoke Hokkien and became children's trusted friends, which contributed to the successful and high-quality data collection.Footnote 37 During the fieldwork, the research assistants, fluent in spoken English, reported their observations and interviews in English to Margery Wolf, who typed these data into English notes. Research assistant MC and a young Taiwanese man and college student Huang Chieh-Shan 黃介山 interviewed children in each of the two projective tests, Doll Play and TAT, and these transcripts were the only Chinese documents preserved in this archive.Footnote 38 Six decades later, my team digitized all these type-written notes into readable files.

This re-analysis is animated by a new theoretical and methodological vision. In 1958, Arthur Wolf's original research purpose was to replicate the Six Cultures study of Child Socialization (SCS) in a Chinese society. Launched in the 1950s by a group of anthropologists and psychologists at Harvard, Yale, and Cornell University, SCS is a landmark project in the history of psychological anthropology and cross-cultural research on childhood.Footnote 39 Wolf's project improved on the SCS design in several respects, including a larger sample size, longer fieldwork duration, and added methods, thus yielding to a more complete, multi-faceted dataset that was larger in volume than that from the individual sites in SCS.Footnote 40 It was influenced by the behaviorist theoretical paradigm in the SCS: for behaviorists, the human mind is a black box and learning is a process of responding to external stimulus, conditioned via reward and punishment.

Significant paradigm shifts in child development research have taken place since the Wolfs’ trip to Taiwan, though, most prominently, the “cognitive revolution”Footnote 41 and subsequent advancements in studying children's developing minds. Young children have a much more complex mental capacity and richer emotional life than behaviorists once assumed, and this matters for understanding the nature of social learning and the foundations of human culture.Footnote 42 As part of a synergy between evolutionary anthropology and cognitive science in exploring the origins of human cooperation,Footnote 43 research in the past few decades has pushed the ontogeny of morality into early childhood, even infancy.Footnote 44 Trained in this new, interdisciplinary paradigm of cognitive anthropology, I approach materials in the Wolf archive from a different angle: my predecessors used the framework of “child training” or “socialization,”Footnote 45 which saw the child primarily as an object being molded by external forces, especially parenting. Instead, I see children as moral agents actively navigating and making their own social world.

For observational data, the original SCS protocol prescribed nine behavioral systems in childrearing (succorance, nurturance, responsibility, self-reliance, achievement, obedience, dominance, and sociability) and a behaviorist “antecedent-consequent” hypothesis-testing procedure.Footnote 46 Instead of following that protocol, I designed a new behavioral grading system that includes about thirty social interaction themes to capture the complexity of children's experience: It is the convergence of deductive, top-down (relevant concepts in current scholarship) and inductive, bottom-up (salient topics in the corpus, features in local context) qualitative coding processes. Each theme was graded according to a binary (0.5, 1) or tripartite (0, 0.5, 1) scoring standard evaluated by its behavioral intensity, valence or frequency.Footnote 47

Moreover, I paid close attention to projective tests data (Doll Play and TAT): children's speech and story-telling prompted by pictures or objects. General projective tests at that time, invented in Western psychology, were designed to elicit fantasy and assess personalities, and were used by anthropologists when the “Culture and Personality School” was still popular.Footnote 48 Different from standardized projective tests in the West, the Wolfs’ team hired local artists to design culturally appropriate prompts. For example, instead of using the ambiguous pictures in standard Thematic Apperception Test,Footnote 49 the Wolfs’ team used a series of nine drawings for their own TAT. Each drawing was a sketch of a social scenario that involved a child figure and some other figures (children and/or adults). They also added a Doll Play task, featuring a set of six dolls in a farmhouse setting, an elderly woman, an adult man, an adult woman, and three children. Contrary to the incomplete or inadequate projective tests data in the SCS,Footnote 50 the Wolfs’ team managed to collect good-quality data from these tests.Footnote 51 Unlike other types of data, his team didn't translate these complete transcripts into English, and following the SCS field-guide, these data were assigned a peripheral role. I believe, however, that fine-grained analysis of children's story-telling can shed much valuable light on their inner experience and provide a rare opportunity to see the local world through the eyes of children.

At a time with no personal computers, Arthur Wolf was overwhelmed by the large amount of data: one of the reasons he turned to other projects. Re-approaching these data today, my challenge, instead, is a lack of first-person fieldwork experience. Fortunately, this archive, with its mixed-methods and systematic nature, afforded me the opportunity to triangulate multiple analytic approaches, including digital humanities methods. I took advantage of new programmatic techniques, including NLP (natural language processing) and social network analysis. These computational methods can complement ethnographic interpretation and behavioral coding to generate multiple levels of insights from this corpus, making it possible for me to re-imagine the lives of children through texts.

A marginalized family and their untold tale

The family of Lin Yukun and Lin Meiyu was featured in Margery Wolf's book A Thrice-Told Tale: Feminism, Postmodernism, and Ethnographic Responsibility, as well as in its shorter, article version.Footnote 52 This family “had lived in the village for nearly ten years, but by village tradition they were still newcomers.”Footnote 53 In a community bonded through kinship, they didn't belong to the prominent lineage of the village, the Lin lineage (pseudonym, to be consistent with House of Lim).Footnote 54 At the beginning of the Wolfs’ fieldwork, this nuclear family included father Lin Tianlai (#47, age 32), mother Lin Chenxin (#48, age 30), and three children: Lin Yikun (#49, age 6, boy), Lin Meiyu (#50, age 5, girl), and an infant boy Lin Jukun (#51).

In the spring of 1960, in a then remote village on the edge of the Taipei basin in northern Taiwan, a young mother of three lurched out of her home, crossed a village path, and stumbled wildly across a muddy rice paddy. The cries of her children and her own agonized shouts quickly drew an excited crowd out of what had seemed an empty village. Thus began nearly a month of uproar and agitation as this small community resolved the issue of whether one of their residents was being possessed by a god or suffering from a mental illness.Footnote 55

Margery Wolf's writing began with this story. The lady in question “was a fiercely protective mother who had quarreled in recent months with a woman from the Lim household when her young son had been slugged by a Lim boy.”Footnote 56 Children's fights, not uncommon in the village, were an important factor in the onset of the lady's “erratic behavior,” and her breakdown was the focus of “A Thrice-told Tale.” These published works, however, gave us few clues about her children: how are these little ones coping with their life, as part of a marginalized family going through a scandalous crisis?

One episode in Child ObservationFootnote 57 clearly shows that children were active participants in village gossip. One day Mother (Lin Chenxin) drew a crowd in her courtyard, dancing like a Tang-ki (spirit medium), making bai-bai motions. She summoned the research assistant MC, hugged her close and praised her for being kind to all the children, but the chaotic scene frightened MC. The next day, children from other families, while playing a hopscotch game, teased their observer, “Older Sister” MC.

A boy named Lin Shihui asked MC: “Did you really cry yesterday when she (Lin Chenxin) caught you? Lin Xiuyun (a girl) told everybody that you cried loud. Did you?”

MC (indignantly): “I did not.”

Lin Xiuyun (angrily): “Now, when did I say that? Now, when did I say that?”

(Another girl) Lin Shuyu laughed very loud.

(The boy) Lin Shihui: “I heard you. Don't you think I didn't hear you.” Lin Xiuyun seemed quite anxious and probably did say this.

One can only imagine the kind of teasing, mocking or social exclusion Lin Chenxin's own children would have experienced. Due to their marginalized situation and the fact that this mother was very shy, Wolf's team did not conduct concentrated observation or interviews with Lin Chenxin as they did with some other mothers. But fortunately her two older children were quite visible in the Wolf archive.Footnote 58 Child Observation includes sixty-four timed episodes that involve at least one of the two children, of which seventeen episodes involve both children. Besides, eight episodes of other (un-timed) observations involve one child or both; in terms of projective tests, both children participated in TAT, and the sister also participated in Doll Play. Drawing from the core data, Child Observation, the next section explores these two children's social positioning in the context of their peer network.

Brother–sister dyad in peer network

Systematic observational data of children in naturalistic settings, with complete information of participants, provide a rare opportunity to examine children's traces and networks. Among a total of 1,678 episodes, nearly three quarters (n = 1,231) involve children exclusively (ages below eighteen), with no adults at all. Even among the remaining 447 episodes, in many occasions adults were merely present, not actually interacting with children. In contrast to the predominant focus on parent–child ties and parenting in Chinese studies, this pattern suggests the importance of peer-interaction and potentially peer-learning in children's life. Social network analysis, based on computing co-occurrence of people in a given observation and aggregating co-occurrence counts across all observations, confirms the primacy of child-to-child ties in this corpus.

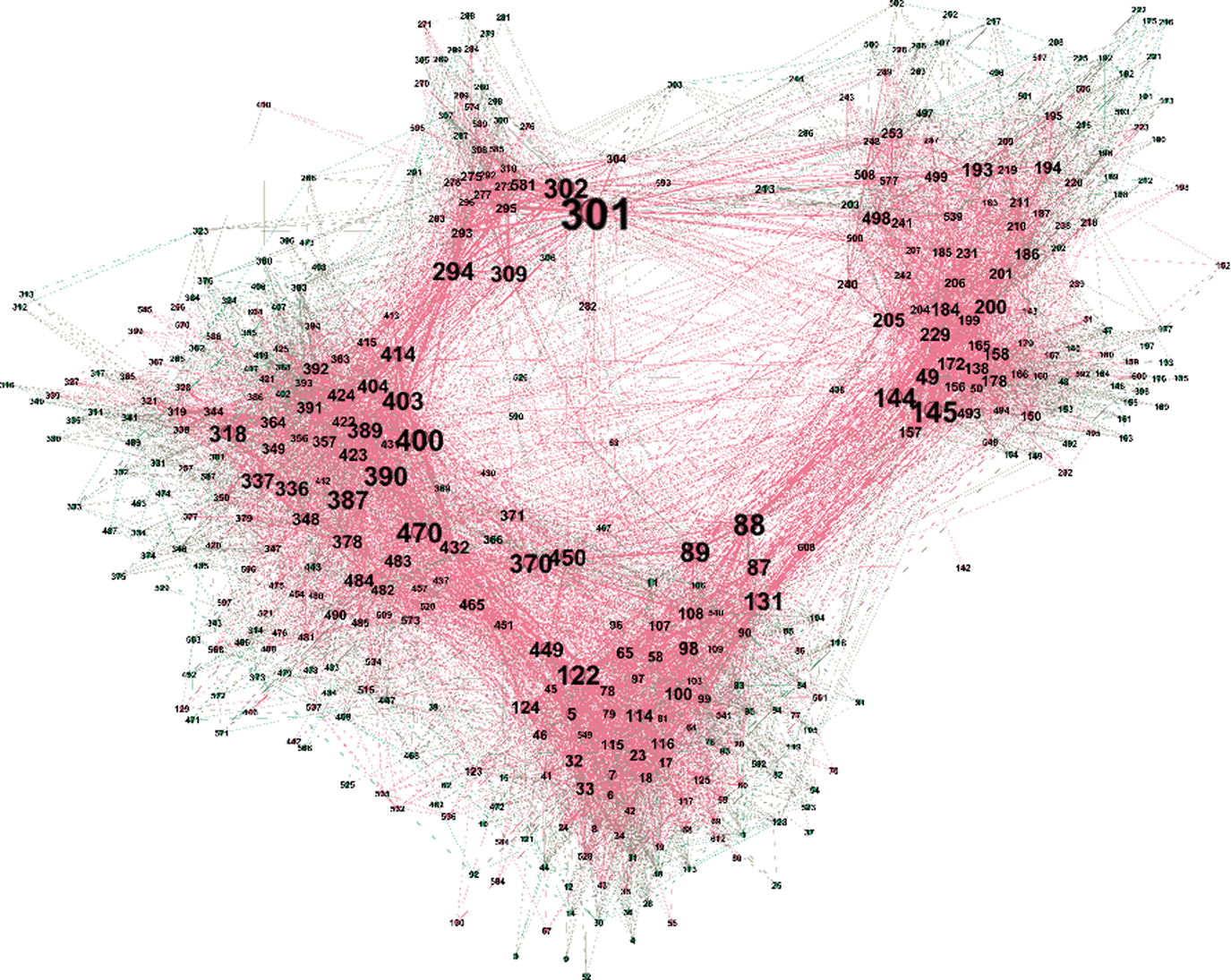

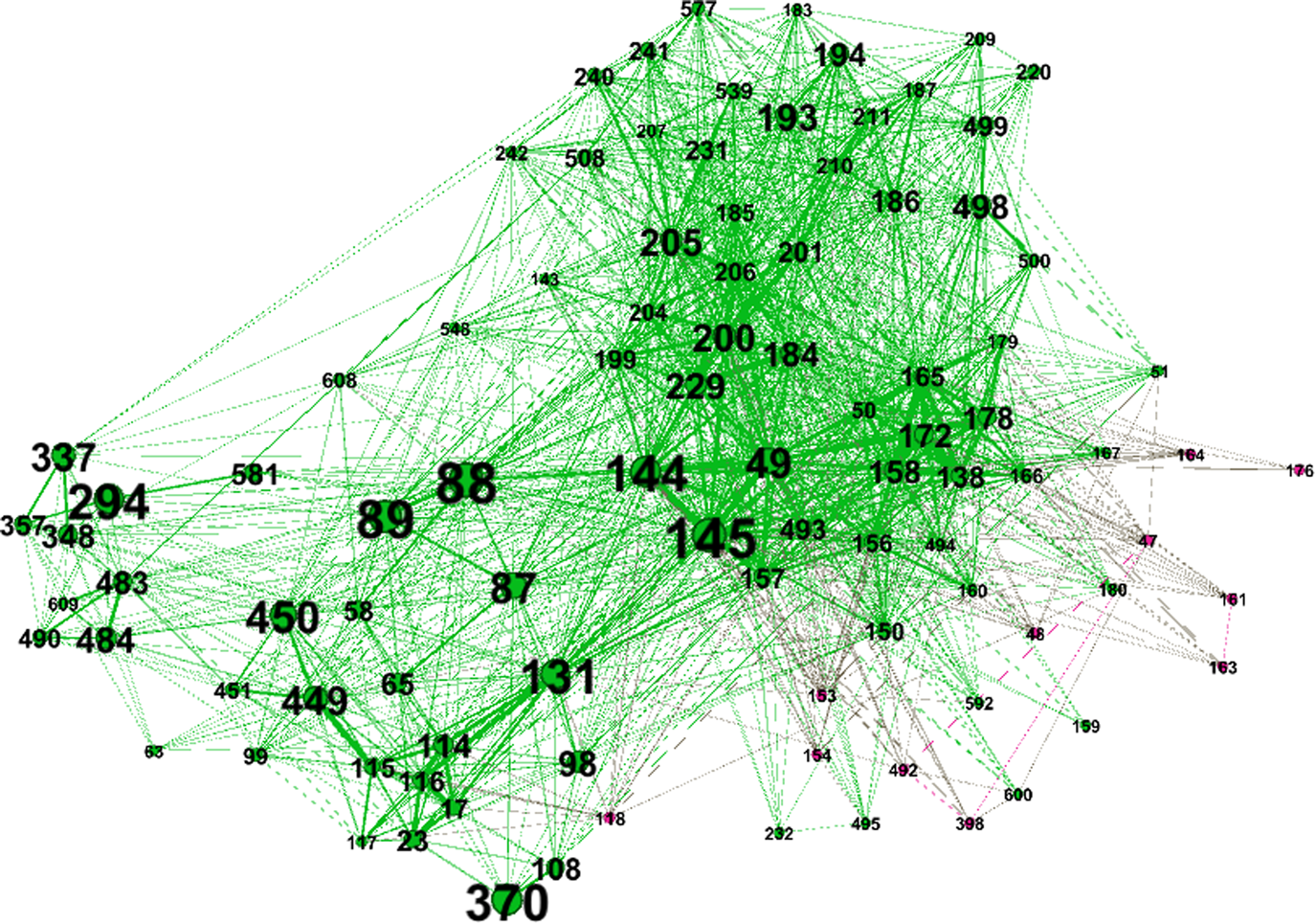

Figure 1 depicts the entire Child Observation network and Figure 2 depicts its subset, the union network of Lin Yikun (#49) and Lin Meiyu (#50). These figures show that children occupied a central position in both networks and that adults were at the periphery. Each node in the network represents a person, each edge (line) between two nodes represents the co-occurrence of these two people; the thickness of edges is proportional to the frequency of co-occurrence observed. The number on each node represents the person ID, and the size of a node is proportional to the person's betweenness-centrality––importance as a “bridge” between other people in the network. In Figure 1, pink nodes represent children and light green nodes represent adults; In Figure 2, bright green nodes represent children and bright purple nodes represent adults.

Figure 2 Child Observation subset (Child #49 and #50) union network

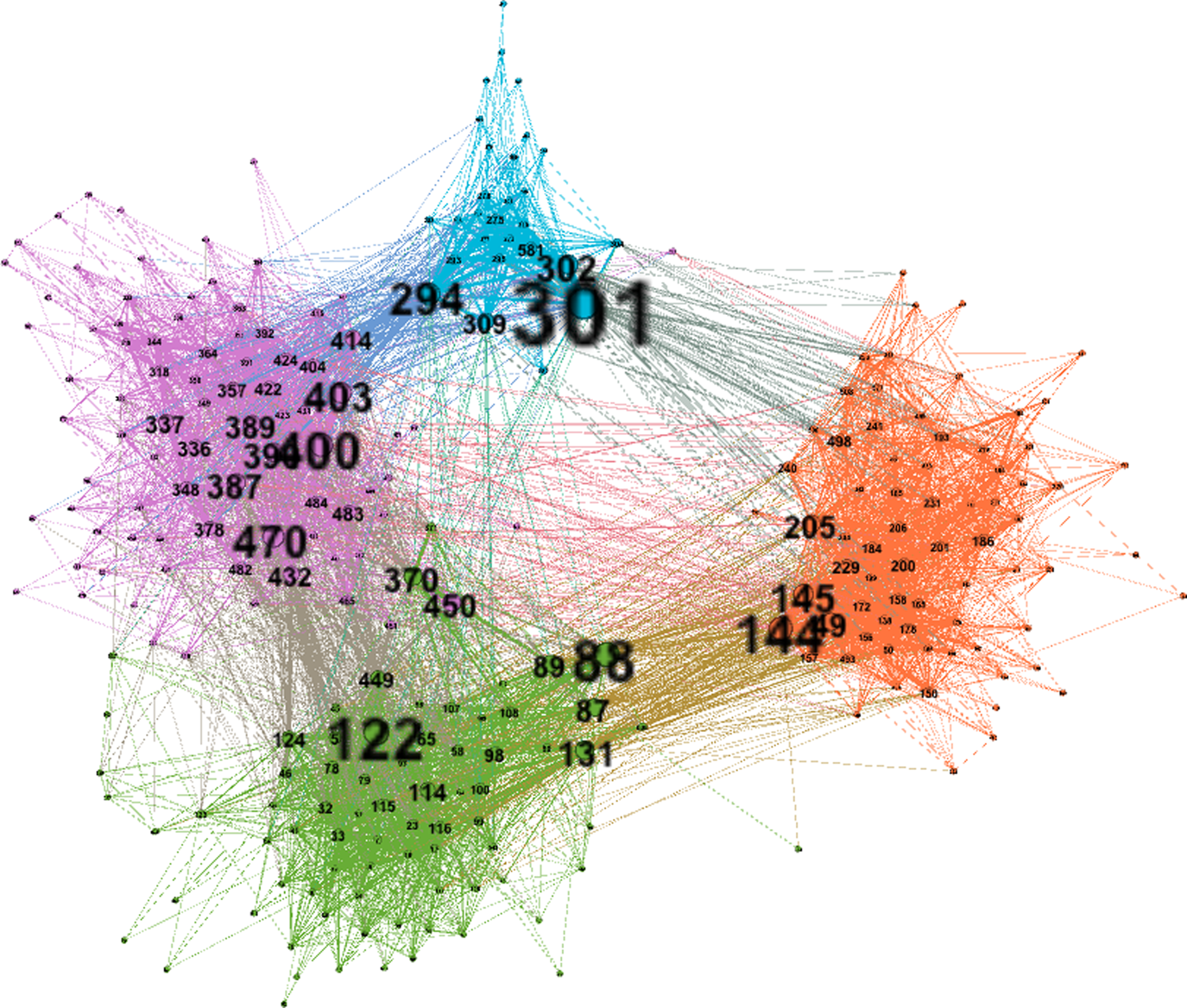

Figure 3 omits all adult nodes and depicts children's peer network in the Child Observation corpus. Based on observed co-occurrence, children formed four “cliques,” indicated by color. The brother–sister dyad, #49 and #50, belonged to the same clique (Figure 3, the right corner), suggesting that they two often played together and their playmates overlapped.

Figure 3 Child Observation child network (modularity)

Moreover, a closer look at this brother–sister dyad's network attributes, in comparison to the respective maximum numbers observed in the child network (see Table 1), reveals these two children's social positioning in their peer world: Brother co-occurred with seventy-nine other children in the network (measured by “degree,” the number of other nodes he is connected to), many repeatedly (total co-occurrence measured by “weighted degree”), and close to the maximum values observed; therefore he was a popular figure in the peer network. But in terms of between-ness centrality, brother was far from being the central hub of connections. Sister ranked much lower in all three attributes compared to her brother. Taken together, Brother was an active figure in the village peer network, despite his mother and family's marginal status; but Sister appeared less in the observations and was often observed overlapping with her brother in play. To understand what contributed to these patterns, age, gender, and/or personality, let's look at the content of observations.

Table 1 Child #49 and #50 in child network. “Max*” represents the child/node who had the highest value in each of the three network attributes. It may not refer to a single child; it just serves as a reference value for positioning Child #49 and #50 in the network

Play, cooperation and conflict

What were Brother and Sister doing in these observations? This section first examines aggregate-level patterns of their peer-interactions through NLP (natural language processing) analysis. It then delves into the granular-level characteristics of these interactions through behavioral-grading, with a focus on cooperation and conflict, the bright and dark side of moral development.

NLP Analysis: word frequencies and clusters

NLP techniques are well suited to analyzing linguistic patterns of these systematically collected observational texts. The Child Observation texts are transformed into “clean” texts, after common preprocessing steps such as removing stop-words and lemmatizing the corpus. Figures 4 and 5 depict the global, word frequency pattern of all the words that appeared in the subset of 64 timed observations involving Brother and/or Sister, out of the Child Observation corpus. Figure 4 presents the top 100 highest-frequency words in a word cloud format, and Figure 5 presents the top fifty highest-frequency words.Footnote 59

Figure 4 Top 100 highest-frequency words in Child Observation subset (Child #49 and #50)

Figure 5 Top 50 highest-frequency words in Child Observation subset (Child #49 and #50)

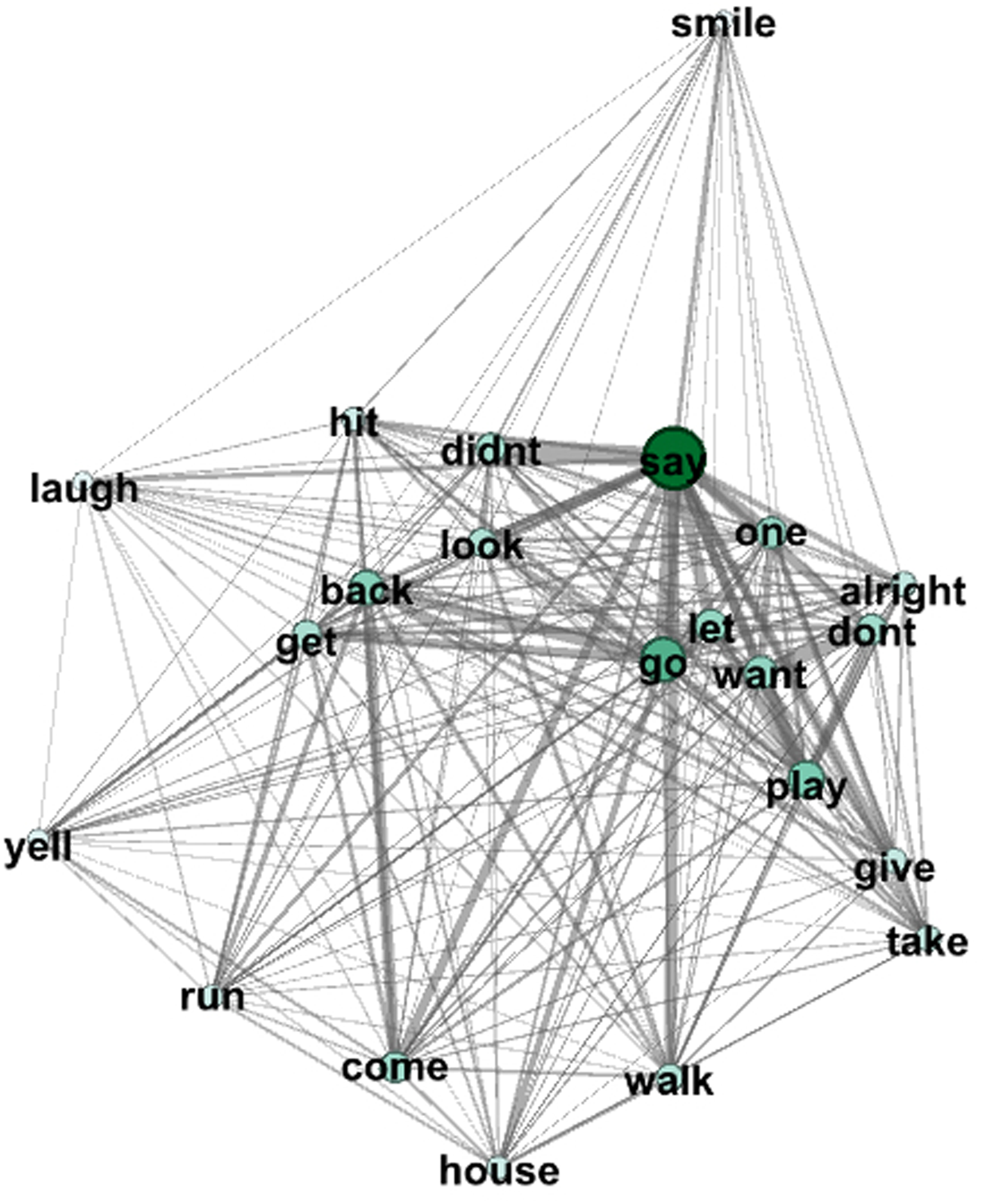

On the basis of these, Figure 6 depicts the word co-occurrence network: Each node represents one high-frequency word, and each edge represents co-occurrence of the two nodes/words, node size proportional to the word's frequency and edge thickness proportional to degree of co-occurrence between the two words. It examines relationships between high-frequency words in this subset. These analyses identify several notable patterns: The words “say” and “play” ranked #1 and #5, indicating the abundance of verbal interactions and the overall prevalence of play in their interactional contexts; The word “hit” ranked #21, lending additional evidence of children's fighting and conflict to support what I found previously from children's interview data;Footnote 60 The words “laugh” and “yell” ranked #20 and #34 respectively, giving us a clue of the emotional texture of children's play; Finally, co-occurrence high-frequency word pairs, such as hit-smile, hit-laugh, and hit-run provides a glimpse into how different behaviors intertwined in children's naturalistic play.

Figure 6 Word co-occurrence network (top 22) in Child Observation subset (Child #49 and #50)

Note: The word co-occurrence matrix in Figure 6 was computed in Python programming language, via word embeddings analysis, and then visualized in Gephi (layout: Force Atlas 2 algorithm).

Notably, many high-frequency words such as “laugh,” “smile,” and “yell” occurred in various emotional tones: For example, laughing or smiling happily (joy), laughing at someone's miserable situation (teasing), smiling with a sense of embarrassment (shame), yelling angrily in a situation of aggression (anger, e.g., cursing dirty words) or yelling happily during play (joy, e.g., successfully spotting the “ghost” during hide-and-seek). Children's emotional and moral expressions are complex and ambiguous, which requires us to go beyond word-association patterns and delve into the behavioral sequences in their contexts.

Behavioral grading: cooperation and conflict

Using a fine-grained behavioral grading protocol, I analyzed all sixty-four timed Child Observation episodes as well as the additional eight episodes of untimed, situation-based observations involving the brother and/or his sister. I clustered peer-interaction behavioral themes into two main categories, cooperation and conflict. Across all observations, at least one child in the sibling dyad appeared in situations with the following forms of cooperation—collaboration, leading, following, ownership assertion, ownership acknowledgement, praising, request for help/sharing/game access/comforting, sibling care, helping/sharing/granting access/comforting—and conflict: disagreeing, physical aggression, verbal aggression, scolding, taking, competition, dominating, submitting, pleading, tattling. I created a composite score for cooperation and conflict respectively. Moreover, several themes of cooperation have a contingent nature, leading to non-cooperation (score 0), thus would be treated differently.Footnote 61 Besides, both children appeared in teasing scenarios, and teasing can be very ambiguous, from playful to aggressive, a grey area between cooperation and conflict.

Table 2 summarizes the behavioral grading results. First, in terms of absolute numbers, Brother not only appeared in a lot more observations than Sister, as co-occurrence social network analysis revealed, he was involved in many more behavioral interactions as the behavioral initiator or recipient. Moreover, in terms of ratio––conflict or cooperation composite score divided by number of observations—Brother initiated cooperative acts more frequently than sister, but the two appeared in similar ratio as recipients of cooperation; Brother initiated conflicts more frequently than sister, and he was also a more frequent recipient of conflictual behavior. In cooperation, Brother acted more as an initiator, Sister more as a recipient (including a recipient of Brother's goodwill); in conflicts, both appeared more as a recipient. Was Brother a more popular figure than Sister? Was Brother helping Sister in peer interaction, as the opening vignette portrayed? If both of them were ridiculed or bullied by peers, what were the reasons? To really understand what these quantitative patterns mean and what motivated these various behaviors, we need to explore the ethnographic details.

Table 2 Behavioral grading results (Child #49 and #50). After grading all behaviors manually, I exported the behavioral grading data to and completed analysis in R programming language (package: dplyr)

Coalition and rivalry: ethnographic insights

This section uses ethnographic episodes to contextualize the aforementioned textual and behavioral patterns, to flesh out these two young characters, and to demonstrate the moral lessons these youngsters learned. Brother and Sister had very different personalities, and their case invites us to reflect critically on common impressions about gender socialization in “the Chinese family,” for example, boys are more aggressive than girls.Footnote 62 Observational materials suggest that the brother was a caring and protective figure. He played with many other kids. The sister was more aggressive, and she was not popular. On many occasions the sibling dyad acted in solidarity, like a small coalition facing the world outside their home. Together they learned to coordinate with peers, negotiating fairness and ownership, adapting to respect game rules, and submitting to peer leaders. But transcripts of projective tests reveal an intriguing picture of sibling rivalry, or, in the sister's eyes, bullying on the part of the brother. These complex patterns illuminate the early development of ambivalent and contradictory dimensions: love and power or care and control, in cross-sex sibling relationship.

Coalition and coordination outside the home: naturalistic observations

As behavioral grading results suggest, Brother Lin Yikun, although accused by his mother and other adults of being a trouble-maker (fighting with other children),Footnote 63 was more a cooperator than an aggressor. By the age of seven he had already mastered clever skills in negotiating rules of games and access to group play with other kids. He used the principle of reciprocity to his own advantage, reminding playmates of his previous favors he'd granted them. For example, when he saw an older girl holding sticks with feathers, he asked: “Give me one of yours, will you? You have two in your pocket.” Rejected by the girl, he insisted: “I, I, I did something for you.”Footnote 64 He sometimes controlled his anger and yielded to other children: Another girl (#172, a year and half older than he), a leader in their small group, bullied him, but he did not fight back. That's why a bystander boy teased him: “A boy is afraid of a girl!” On another occasion, chased, cursed, and hit by two naughty boys much younger than he, he appeared frightened. Those boys’ older brother laughed: “Ha ha, the older one is afraid of the younger one.”Footnote 65 Although sibling care was mainly girls’ responsibility, Yikun also helped take care of his little brother (#51). In one scenario his sister Lin Meiyu called the observer MS: “See? Big brother can take care of little brother.”Footnote 66

Lin Meiyu, on the other hand, had a different personality, which helps to explain why her status in the peer network was more peripheral compared to that of her brother. She was not a popular child, even before the onset of her mother's scandalous insanity. Unlike her brother, she was not that easy to get along with. She interrupted other children's play or bullied them, including her big brother. Her brother's friends saw her as a troublemaker and were reluctant to include her during their play. She wanted to play with other children, though. Once two boys were playing a marble game—pretending little rocks were marbles. She asked to join but was bluntly rejected by one of them. She turned to the other boy, her classmate, attempting to manipulate him: “He (your playmate) doesn't want our Jung class [忠班] to play!”Footnote 67 The boy who rejected her stayed firm: “Yes, I do. I just don't want you to play.” During a jumping rope game, one boy explicitly asked the group leader not to let Lin Meiyu play: “She hit my little brother.” Meiyu walked off, looking unhappy.Footnote 68

One day, Lin Meiyu was excluded again. Three children were playing house. She walked up to watch, but a girl shouted at her (angrily with a threatening look): “Get out of here! I don't want you to look.” She looked sad and walked away. But her brother Lin Yikun happened to be there. He yelled to tattle to his mother, attempting to protect his sister.Footnote 69 Lin Yikun appeared as a brother of a caring heart: In dyadic interactions, he yielded to her many times even when she grew aggressive. In multi-person interactions, he used his social skills to help her. The opening vignette is a great example: He “bribed” a girl with face-powder so that she would agree to play with his little sister.

Sometimes help was mutual and cooperation was fruitful: Playing “house” with other children, they partnered in “crime,” taking away a small boy's stones and teasing him;Footnote 70 But seeing another child cheating a younger one when playing tops, Sister echoed her brother to mock and condemn the cheater.Footnote 71 In hide-and-seek games, they two coordinated together to “cheat,” sister on the watch for brother who was the “ghost” trying to catch hiding children.Footnote 72

But since neither of them was a leader in their peer group, negotiating with peers could be difficult. In the following observation, their negotiations failed. Footnote 73

Children were playing “cars” on 2 seat tricycles. Lin Yikun was in the front seat and another little boy was pushing. Sister came and sat down.

Yikun told the child who was next in line to get on the trike: “Come and get in your seat. Next time it's my sister's turn.”

An older girl (#138) disagreed: “No, it's not, it's mine. We have to line up.”

Yikun countered: “No. We pretend she (Lin Meiyu) is my daughter so I have to give her a ride first and she doesn't have to pay for a ticket”

The girl (#138) rejected: “No, you can't do that. We have to line up.”

Yikun: “It's my tricycle!”

Disagreement continued, until the leader (#172) in their playgroup, a quite dominant girl, intervened and reinstated the importance of turn-taking rules. Brother attempted various methods to help his sister skip the line, improvising fictive parent–child kinship (apparently the real sibling tie was not enough) and asserting his ownership. But in the end they had to submit to more “powerful” children, even though they were playing on his tricycle. In this quite serious pretend play scenario, we not only see children's rich imaginative world––riding tricycles as “cars” and using leaves as tickets—but also how they learned to coordinate with peers and comply with rules.

Conflict and rivalry at home: story-telling in projective tests

What about life inside their family? As I mentioned earlier, because their mother was a shy figure, the Wolfs’ team didn't manage to interview her or observe their family interactions at home. But, fortunately, these children participated in projective tests. These verbal communication records offer a precious window into children's thoughts and emotions. In both tests, children were asked what they thought people in the scenarios were doing. The Doll Play test in the Wolf Archive, based on localized dolls and farmhouse, featured children's spontaneous story-telling about family scenes. Some TAT drawings could be interpreted as interactions between family members too. Narratives in these two projective tests shine light on actual family dynamics inside the home.

In Lin Meiyu's Doll Play test, a salient theme is sibling rivalry or, to be more exact, brother dominating and bullying sister. At the first sight of dolls, she looked carefully, checked the dolls’ clothes, and started to tell this story spontaneouslyFootnote 74:

AFootnote 75: Big sister was arguing.

Q: With whom?

A: Big brother.

Q: Why?

A: Brother ate her candy.

Q: Then they started to argue, right? How?

A: They fought on and on. Brother hit sister; he's bad.

Q: How did they fight? Can you show me?

A: Like this, like this! (Holding B-boy doll and G-girl doll, crashing them)

Q: How's the sister?

A: She cried.

Q: Did the sister hit the brother?

A: No. Sister didn't. It was brother all the time.

Meiyu was tested in two sessions. In both sessions, she spontaneously pivoted the conversation to the same topic: brother is mean to sister and he deserves to be punished. Unlike “brother eating sister's candy” or “brother hitting sister” in the above excerpt, in some other segments she didn't even articulate a specific explanation. For example, she just repeated: “He (brother) is so bad.” This poses a stark contrast to the imagery of a protective brother and the pattern of brother–sister solidarity that emerged in peer play outside the home setting. One might wonder, though, if this had anything to do with Meiyu's real experience, or whether it was just purely imaginary fantasy. Yes, these utterances were a product of children's story-telling exercise, and most likely it does reflect Meiyu's self-serving bias, that Brother was always the villain. But there are several reasons to doubt that stories she told were mere fantasies: first, sibling conflict is one of the most common themes across all Doll Play transcripts (nearly fifty children), which probably reflects its prevalence in this village community. Besides, in Meiyu's two sessions, the names she gave the dolls mapped exactly onto her family's real situation. For example, she called the boy doll “big brother,” the girl doll “big sister” and the baby doll “little brother.”Footnote 76 Moreover, the scenario of brother–sister fighting, especially over candy, appeared not only in Doll Play. It also surfaced in Meiyu's TAT session conducted several months earlier, and in surprisingly similar ways. Compare the following two excerpts: The first one was from her Doll Play transcript, and the second was from her TAT transcript.

Doll Play excerpt:

A: Big brother wanted money for food.

Q: Who gave him money?

A: He asked her. (Pointing at M)

Q: What did the brother say to mom?

A: He said, “mom, give me one cent.”

Q: What did mom say?

A: Mom said, “why did you fight.”

Q: And the brother?

A: And sister came told mom brother took her candy away.

Q: What did mom say then?

A: Mom said she would not give him one cent.

Q: What did the brother do next?

A: He cried.

Q: And how's mom?

A: Mom said, “why did you take your sister's candy?” Big brother stopped crying.

The following TAT excerptFootnote 77 is especially intriguing. The research assistant showed Meiyu the fifth drawing in the set, which featured a girl, a broken bowl on the floor, and an adult woman. Meiyu interpreted the drawing as about the girl breaking a bowl and her mom reacting to it, including beating her. When the research assistant asked what the girl in the picture would feel when her mom hit her for breaking the bowl, Meiyu went silent. Then, the research assistant repeated his question: “What will the girl feel?” Surprisingly, Meiyu pivoted her answer to an apparently irrelevant topic, big brother taking her candy:

A: She wants to fight someone.

Q: Does She want to fight someone?

A: Yes.

Q: Who did she fight with?

A: Her brother.

Q: Why her brother?

A: Because her brother took her candy.

Q: Did the brother really take her candy?

A: Yes.

Q: Why?

A: There was a lot of candy, so he took all of them.

Last but not the least, another detail in the story Meiyu told about the girl character breaking a bowl alludes to her own family's experience shown in A Thrice-Told Tale. Right before the above TAT segment, Meiyu mentioned that the girl's mother found out she broke a bowl. Asked what would happen then, Meiyu answered: “When mom found out, she didn't feel well.” When asked why mom didn't feel well, she pivoted, again, to the topic of fighting, the girl fighting with her big brother. Children fighting and mom feeling unwell was not something portrayed in that particular TAT drawing at all, but it encapsulated what happened to Meiyu's mom: Her brother Yikun's fight with another boy (presumably from the important, “House of Lim” family), was a major contributing factor to the onset of their mother's psychiatric symptoms. Coincidentally, Meiyu's TAT session was conducted in summer 1960, just a few months after her mother's “erratic behavior.” Pressed by the research assistant twice to explain why, in the drawing, the mom would feel unwell upon her children's fighting, Meiyu kept silent. This little girl's nuanced reactions, her utterances and hesitancy, hint at the lingering impacts of the chaos in the adult world on these young children's emotional and moral experience.

Taken together, Meiyu's reactions in projective tests amount to what I call “reality-based fantasy”: The stories she told are closely related to, or mapped from, the reality of sibling rivalry and conflict at home, in competition for resources and parental care. These projective tests also reveal another key aspect of Yikun and Meiyu's social world, that is, fighting and punishment. The next section shifts the attention to punishment, highlighting children's agency in negotiating parental discipline and situating their experience and imaginations of authority and violence in the local context.

Punishment and (DIS)-obedience: from parenting to children's experience

The disobedient child: punishment and its discontents

Many ethnographers at that time, including Margery Wolf,Footnote 78 noticed an important parenting value in rural communities in post-war Taiwan, namely attempting to prohibit fighting among children. Parents took children's fighting seriously and did not hesitate to punish children who engaged in conflicts. Punishment includes scolding, beating, and sometimes tying up the offender with a rope. Parental punishment, especially from the mother, was a salient theme in the lives of Lin Yikun and his sister. It not only appeared in Meiyu's story-telling, but also recurred in several segments of Yikun's TAT transcript: For example, when shown the drawing of a girl character, a broken bowl and an adult woman character, Yikun mentioned the same scenario as Meiyu did, that mother would beat up the girl; Presented with other drawings featuring multiple children, he inferred that the children were fighting and would be punished by the mother figure.Footnote 79

Arthur Wolf explained the rationale of this ideology in its social context, the need to maintain neighborliness in a close-knit community connected through kinship ties:Footnote 80

[M]ost Taiwanese mothers … were extremely anxious about their children's getting into fights with their neighbors’ children. Children were never encouraged to fight back. To the contrary, they were severely punished for fighting regardless of whether or not they had instigated the fight. The most likely explanation is Minturn and Lambert's suggestion that “relative anxiety about peer group aggression is related to the intimacy of social and economic bonds among members in the community, and the degree to which children can disrupt these adult relationships.”Footnote 81

The tragic story of Lin Chenxin––Yikun and Meiyu's mother, illustrates the extent to which children can disrupt adults’ relationships with neighbors. But how did these children react to parental discipline? The following is an excerpt of one episode observed right in front of their house.Footnote 82 In this scenario a little boy attempted to tattle about Yikun's misbehavior: “stealing” flowers. Yikun's mom cursed the tattler and gave the flower back to Yikun—indeed “a fiercely protective” mother.Footnote 83 But the observation also sheds light on Yikun's naughty disobedience. He ignored mom's threat and punishment.

Lin Yikun came back with a branch with a flower on it.

145 (a six-year-old boy): “I know whose flower that is. I'm going to tell him. I'm going to go tell that you're stealing his flowers.”

Yikun: “I didn't steal it. I found it.”

Yikun's mom came out and asked him: “Where did you get that flower.”

When Yikun saw his mother coming, he threw the flower on the ground. 144 (an eight-year-old boy) and 204 (a ten-year-old boy) ran to get it.

145 was still yelling: “You stole somebody's flower. I'm going to tell somebody. Something's going to happen to you.”

Yikun's mom to 145: “Tell you're going to die! What would you get if you told? You'd get a sex organ (cursing).”

145 stopped yelling and looked a little confused. Mom went to Yikun and said: “Where did you get it? How could it get in there. The gate is closed. If you do it again I'm going to beat you.”

Mom took the flower from 204 and said to Yikun: “Go home.”

Mom and Yikun walked into the house. Yikun hadn't said a word. He looked a little bewildered. As they went into the house mom said: “Next time I'm going to tie you in the house.”

Mom walked into the kitchen and Yikun came out again. 145 stood and watched all this. 145 saw a dragon fly and ran to catch. Yikun ran also to get it.

145: “No. It's mine.”

Yikun: “No. It's mine.”

They pushed at each other. Yikun's mom had come to the door again. She yelled: “Whose? It belongs to the one who catches it.”

She told Yikun: “Don't catch it. What do you want that for? If you don't have rice you can't live. If you don't have a dragonfly you'll live. Come back.”

Yikun: “No!”

Children's discontent with punishment manifested in various ways, not only towards their own parents. In a Mother Observation (MO) episode, in the aftermath of a conflict with a younger boy, Yikun defiantly confronted another adult (#226) and articulated his justifications, when the adult cursed Yikun and threatened to beat him up:Footnote 84

At that point Lin Yikun was standing about ten steps away from him.

226 scolded him loudly, “KanFootnote 85. Why did you hit a boy smaller than you? You should give way to a boy who is smaller than you. You should. Didn't you know it? You hit him so hard that you hurt him. I'll call the policemen and let them seize you.”

Yikun held his head high up looking aimlessly around showing that he was not at all scared. 226 stopped to breathe and Yikun took the chance, saying, “He tried to take my thing away by force. He even pushed me down to eat the mud. Why shouldn't I beat him for it.”

226 cursed, “Kan. If you hit him again I'll surely beat you to death. Try it and see. Kan.”

Then he walked away talking to 192 (another adult), who happened to pass by, and telling the story angrily. 192 said, “He (Yikun) really is a bad boy.”

Children's moral compass is more complicated than that prescribed by adults. Older children yielding to younger ones is indeed an important parenting norm in this community.Footnote 86 However, although adults judged him as a bad boy and scolded him for not yielding to the younger one, Yikun apparently did not agree with these adults. He believed hitting was justified when it was defensive and reciprocal. Not just concerned with what happened to themselves, they also talked about other children's experience in clearly normative terms, with their own sense of justice and fairness. In one observation, Yikun was playing with a six-year old girl (#178). On the way 178 said: “Beiguang (her grandfather's older brother) is very mean. One day 172 (Beiguang's granddaughter) was just standing under the guava tree and Beiguang came and hit her.” Yikun extended his moral judgment: “He shouldn't have hit her. She was just standing there. She didn't do anything.” 178 agreed: “That's right. He's not supposed to hit her.”Footnote 87

Moreover, children even mocked parental discipline, turned it into their own entertainment, and enriched their creative game-play repertoire. The following episode involves the sibling dyad, Yikun and Meiyu, in a group play initiated by the leader girl (#172):Footnote 88

172 was mother and running around spanking all the children. 178, 179, and Lin Meiyu were going back to 172. 172 ran out and they all ran away yelling: “Mother is coming!”

They ran all the way to the center before they discovered 172 wasn't chasing them. They came back. Lin Meiyu didn't go all the way and just as they got back she yelled: Mother is coming! Off they went again, laughing and yelling. They returned again. 172 wasn't in sight. 178 sneaked around trying to see her.

179 yelled: “Mother is coming!” And 178 jerked to a stop. This was repeated several times. Finally, 172 called 178 to “come home.” 178 walked over to her.

Lin Yikun and 157 were kneeling in front of 172, laughing and moaning: “Oh mother, I don't dare do it again. Please don't spank me.”

172 was getting some rocks from under a basket. 178 picked up a stick and walked over to the kneeling children and pretended she was striking them, saying: “Oh, you dead child. What are you kneeling here for?”

178 walked over to 157 and repeated this. 157 stood up (angrily) and said: “Why do you hit me?” He hit 178 back.178 just smiled. 157 knelt down again and took up his refrain of “Oh Mother, don't hit me.”

178: “Oh, you dead child! What are you kneeling here for?”

They both turned around and said: “Well, it's your mother that told us to.” 172 came back with two rocks on a “plate” and a stick in her hand. She lifted the stick as if to hit them and they jumped up and pulled on her and said: Oh, please don't hit me. Then they each grabbed a rock and ran away. P stood laughing.

172: “Oh, those two dead children!” 172 put away her “plate.”

Lin Yikun and 157 came back with several children behind them, waving the stolen rods and saying: “We're here! We're here!” 172 jumped at them and they all ran away.

Ethnographic records of “the Chinese family” from the mid-twentieth century have said a lot about parental punishment and discipline, its ideology and practice.Footnote 89 Their analytical focus, nonetheless, was skewed towards the adults, the enforcers of punishment. That obscured the actual experience of the punished, the complexity of children's reactions, and their discontent with authority, hierarchy, and parental power. This hilarious episode showed us how children, arguably the least powerful members of local society at that time, channeled their discontent––a mixture of fear, anger, and perhaps also contempt––into humor, sarcasm, and amusement.

Learning morality: through children's eyes

The lack of interest in children in the anthropology of the Chinese family makes sense if we follow behaviorist assumptions that children are mere objects of training: They get deterred, conditioned, and molded by adults’ discipline such as scolding, shaming,Footnote 90 and punishment. Nevertheless, as cognitive anthropologists point out, evaluating the child as approved or disapproved of is a universal technique in shaping children into competent members of their communities, but its very efficacy is precisely predicated upon children's emotional and cognitive predispositions.Footnote 91 Once we shift our attention to children and see the world through their eyes, we are confronted with the puzzles of learning morality—puzzles that are central to understanding where norms regulating social relations come from and how they change or persist across generations.

When I read the above episodes and encountered children mimicking familiar scenes in their life, such as adult scolding “you dead child” and child pleading “mom, don't hit me,” I couldn't help but wonder: What did these little ones think and feel about that, when they were punished by parents, or observed other children being scolded and shamed? When they pleaded to parents, did that deter them from misbehaving, or was that more of a negotiation strategy? Moreover, when Lin Yikun defended himself for not yielding to a younger child in front of that child's father, and expressed his dissatisfaction toward the unjust punishment forced upon another child, we are prompted to ask: how did children develop their own understanding of what is right and wrong, which might be at odds with what adults taught or demonstrated?

The socio-cultural approach to moral learning––a manifestation in sinological anthropology is the emphasis on “parenting” and “child training”––tends to omit the active role of children themselves.Footnote 92 A main reason for this is an impoverished view of learning. In his 1995 book The Roads of Chinese Childhood, Charles Stafford pointed out that mainstream anthropological accounts of cognitive development were psychologically implausible: “How people actually learn (as opposed to how societies organize learning) is scarcely understood by anthropologists.”Footnote 93 It rings true even today that mainstream anthropologists don't care about learning as agentive, experiential processes—as a recent critique points out.Footnote 94 The Wolf archive provides a unique opportunity to address this problem. In a previous article I analyzed standardized interviews with seventy-nine children on questions related to aggression. I found that children's answers deviated from the parental ideal of avoiding fights and revealed, in their narratives, well-calibrated reciprocal aggression and sensitivity to others’ intentions.Footnote 95 Observational and projective tests records, as demonstrated in this article, not only reaffirmed the prevalence of children's fighting despite parental admonishment and punishment, but also revealed their discontent with authority, calculation of reciprocity and reasoning of justice. These patterns defy the earlier, behaviorist explanation of reward–punishment reinforcement learning that framed the SCS study and illuminate young children's complex psychology, the capacity to construct their own moral universe.

Concluding remarks

Children matter for the human family. Human beings take an extraordinary long time to grow up; such extended period of immaturity and dependency, which prepare us for behavioral flexibility and adaptability—that is, the power of learning—is key to our species’ success.Footnote 96 This paper reconstructs the story of two young children from historical field-notes that are ordinary but also extraordinary: ordinary because they are about young children's mundane life; extraordinary, because they provide a window into children's rich socio-moral world, a topic that was long obscured in studies of “the Chinese family.” I traced how the brother–sister dyad navigates the social world and negotiates with peers and adults: the two helped each other in peer interactions outside the home, longing for social inclusion; they told stories of sibling conflicts at home; they maneuvered against adult punishment and mocked it in game play.

Rediscovering this story enriches historical and anthropological understanding of morality and family. First of all, going beyond a predominant focus on parent–child ties, I show that child-to-child ties constitute an important space for moral learning. In contrast to the highly mechanistic, behaviorist model of “child training,” children negotiate their own social norms and create their own culture.Footnote 97 Siblings are especially important in this regard. The dualities of care and dominance, and love and power in their early form matter for understanding sibling relations in adulthoodFootnote 98 and for the double-edged quality of human kinship.Footnote 99

Moreover, sibling relationships in childhood were rarely studied in the anthropology of “the Chinese family.” These ethnographic records offer precious historical insights into the roles of adult siblings in today's Taiwan.Footnote 100 Connected to the Wolfs's classic works on family and kinship more broadly, these records also provide a comparative reference to understanding family change in China: the experience of singleton children and their families in urban China over the past four decades and uncertainties about the future, as China is grappling with its stark reality of ultra-low fertility despite the promotion of the two-child policy and now three-child policy.Footnote 101

Last but not the least, by bringing to light young children's stories in the past from the shadow of classic works in sinological anthropology, this article looks toward the future, to envision new theoretical and methodological conversations. It is a call for ethnographers to embrace methodological pluralismFootnote 102 and engage with digital humanities techniques to examine fieldnotes old and new.Footnote 103 It also advocates an interdisciplinary, cognitive anthropology approach that takes children's psychological capacities and experiences seriously, and puts them at the center of understanding human relatedness. However remote or invisible, children are moral agents in all corners of human society.