“Bird-tracks” and “tadpoles” are both names for ancient script. As customs changed, the script came to be used less and less, until any basis for knowledgeable discussion was lost and it was known only from hearsay. The Grand Preceptor said: “When the [forms of the] rites are lost, search for them in the countryside.” Might not ancient script be even better than the countryside? Footnote 1

The names of dozens of artists from the tenth century have come down to us, for the most part with very little information about their lives and scarcely more about their art. Fortunately, the life and professional career of Guo Zhongshu 郭忠恕 (928–977) can be reconstructed in enough detail to give a sense of the personality of the artist and the world that he experienced. Indeed, we are doubly fortunate because Guo, it turns out, had no ordinary life. Known to art historians today primarily as one of the great painters of architectural subjects in Chinese history, Guo entered adult life in a different guise, as a brilliant young paleographer and calligrapher. This aspect of his career, no less important than his painting, is the subject of the present study. Although specialists have recognized his scholarly and calligraphic achievements, we still lack a contextualized account that incorporates what can be known of his biography and social circumstances. More important for the theme of this special issue, the material dimension of Guo's paleographic and calligraphic activities also remains to be explored. Any discussion can only be very partial, however, since no manuscripts or autograph calligraphies survive, only stone steles; fortunately, Guo's engagement with stele production is in itself of the highest historical interest. The chronologically organized text that follows tells a biographical story, with as much detail as the available sources allow, which eventually opens out onto the material world of steles, before returning to biography to recount the last chapter of Guo Zongshu's life. Rather than offering a conclusion, I end with a reflection on the materialities of transmission of paleographic and calligraphic knowledge. For the purposes of this article I have not thought it necessary to choose between the very different lenses of biography and material culture, since my goal is not to prove a thesis but to reconstruct an unfamiliar world. As I hope to show, the understanding of one person's life can enrich the understanding of artifacts associated directly and indirectly with the person, and vice versa.

Luoyang and Bian, 928–948

Guo was born in Luoyang in 928 under the Later Tang dynasty, during the relatively peaceful and enlightened reign of Mingzong (r. 926–933).Footnote 2 The Later Tang at that moment controlled most of north China, and during the previous year had absorbed the Shu kingdom in Sichuan as well (Sichuan would secede again in 934). In his later years, Guo claimed his ancestral home to be Fenyang 汾陽 in Shanxi, just south of Taiyuan, where there was a famous branch of the Guo family descended from the Tang general Guo Ziyi (697–781). The eleventh-century art historian, Liu Daochun 劉道醇, however, records Guo's home as the area of Wudi 無棣 and Dihe 滴河 counties in modern Shandong, north-east of Jinan 濟南.Footnote 3

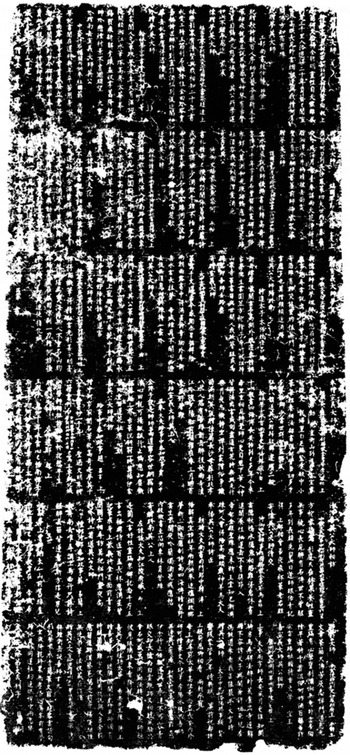

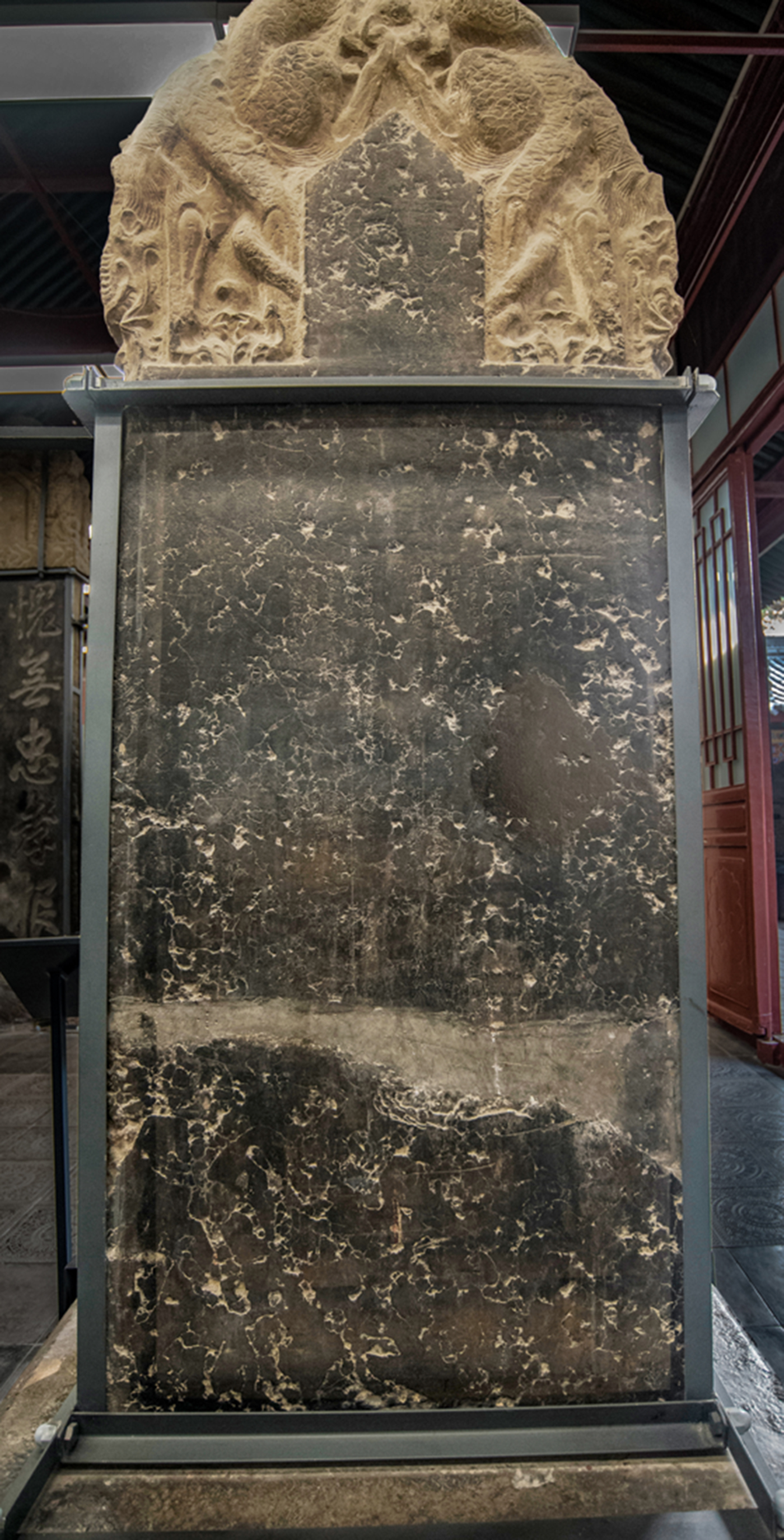

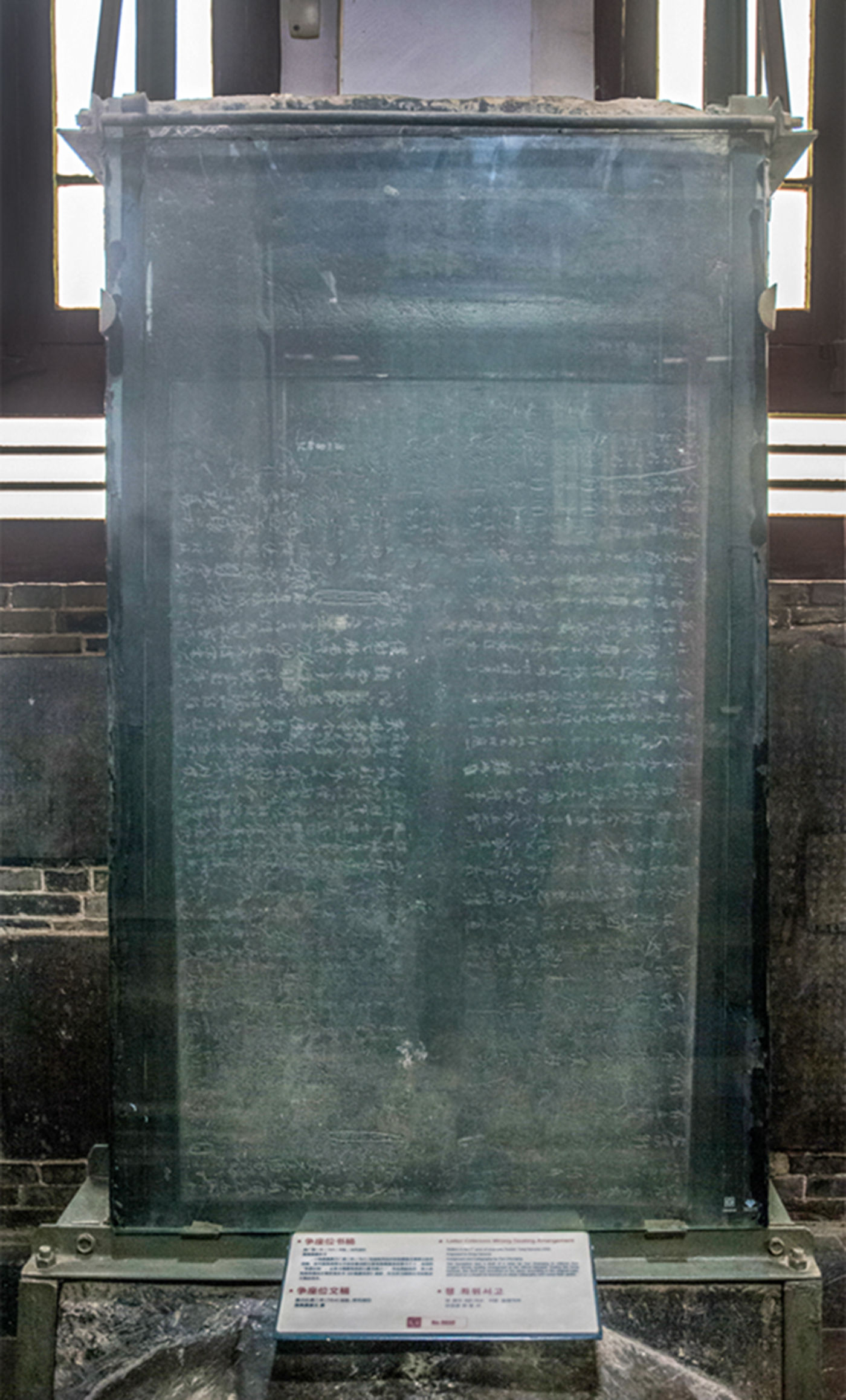

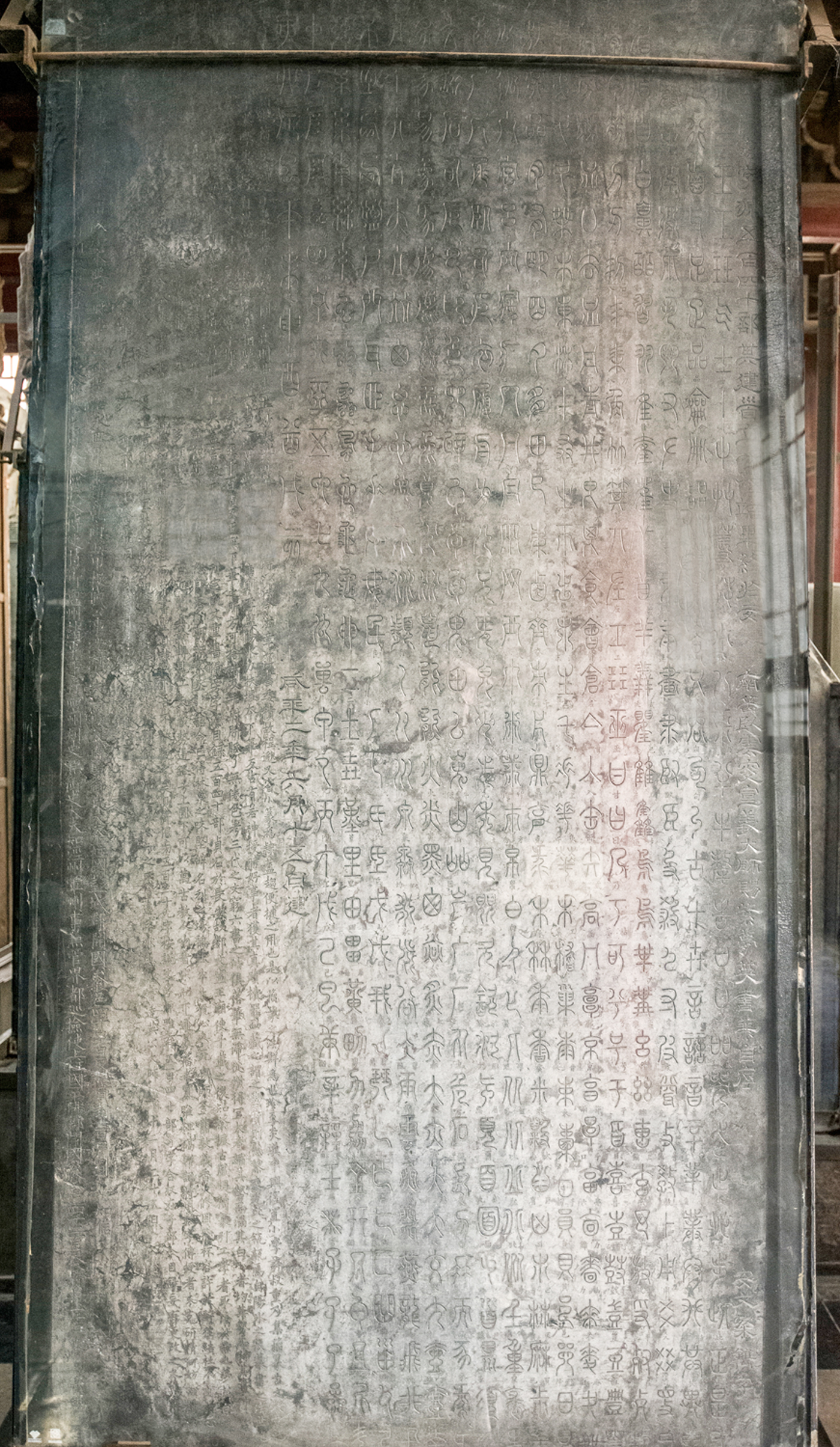

Compared to nearby Bian (modern Kaifeng), Luoyang was an old-fashioned place where the attachment to classical education was widely shared in the population. In Guo's case, “he learned to read from his maternal grand-uncle Zai Tianxing 宰天興.”Footnote 4 Guo turned out to be a child prodigy. He appears to have been fiercely interested in writing and calligraphy and was able as a boy to “master the Nine Classics” (tong jiujing 通九經).Footnote 5 The Nine Classics did not simply refer broadly to the canonical Confucian texts, but more specifically to the stone-engraved editions of the Classics dating from the Kaicheng period (836–840), when sets of stones were engraved in standard script to stand in front of the National University (Taixue 太學) buildings within the Tang dynasty Directorate of Education (Guozijian 國子監) complex in Chang'an (Figure 1).Footnote 6 It was presumably rubbings taken from these Stone Classics that Guo used as a child, allowing him to pass the special tongzi examination for gifted children at the age of seven sui, one of nine children nominated by local officials as Prefectural Nominees (xianggong 鄉貢) who received the degree that year.Footnote 7 The bureaucratic records inform us that Guo Zhongshu and the other eight boys first gave an account of their family circumstances and submitted the documentation of their nomination for verification, then were given an identification tablet and led into the examination hall.Footnote 8 Guo's earliest biographer, Wang Yucheng 王禹偁 (954–1001), reports that during the examination Guo was able to “recite the Book of History (Shang shu 尚書) from memory and write out the Analects of Confucius (Lunyu 論語).”Footnote 9 Apparently, the examination Guo took conformed to the Tang regulations of 866, which called for the student to be able to recite from memory one complete classic plus sections of the Analects and the Classic of Filial Piety (Xiaojing 孝經), and also to be able to write as required.Footnote 10 Having successfully passed the examination, Guo and the other boys reported orally their official certification to the Bureau of Appointments in the Ministry of Personnel.Footnote 11 This procedure existed because the tongzi examination qualified the successful child for later appointment as an official, even though the child might take no further interest in study. The absurdity of this system led to the temporary abolition of the tongzi examination from 940 to 943 under the Later Jin.Footnote 12 The date of Guo's participation in the tongzi examination has long been in dispute, because the date of 924 recorded in the documentary collection Models from the Archives (Cefu yuangui 冊府元龜, completed 1013), which would imply a birth date of 918, is incompatible with the statements in Song shi 宋史 that Guo was ruoguan 弱冠 (around twenty sui or slightly older) in 948 and must therefore have been born ca. 927–928.Footnote 13 As it turns out, 927 can be ruled out as a birth date because a separate documentary record of successful candidates exists for the corresponding 933 tongzi examination, which lacks Guo's name; thus we may conclude that Guo was born in 928.Footnote 14

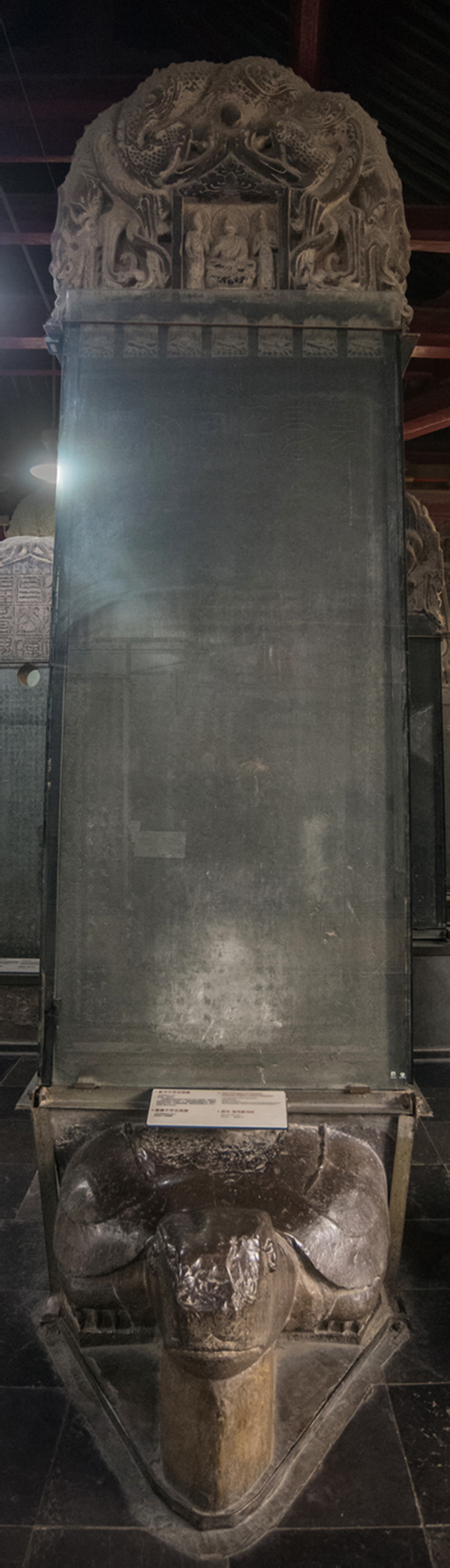

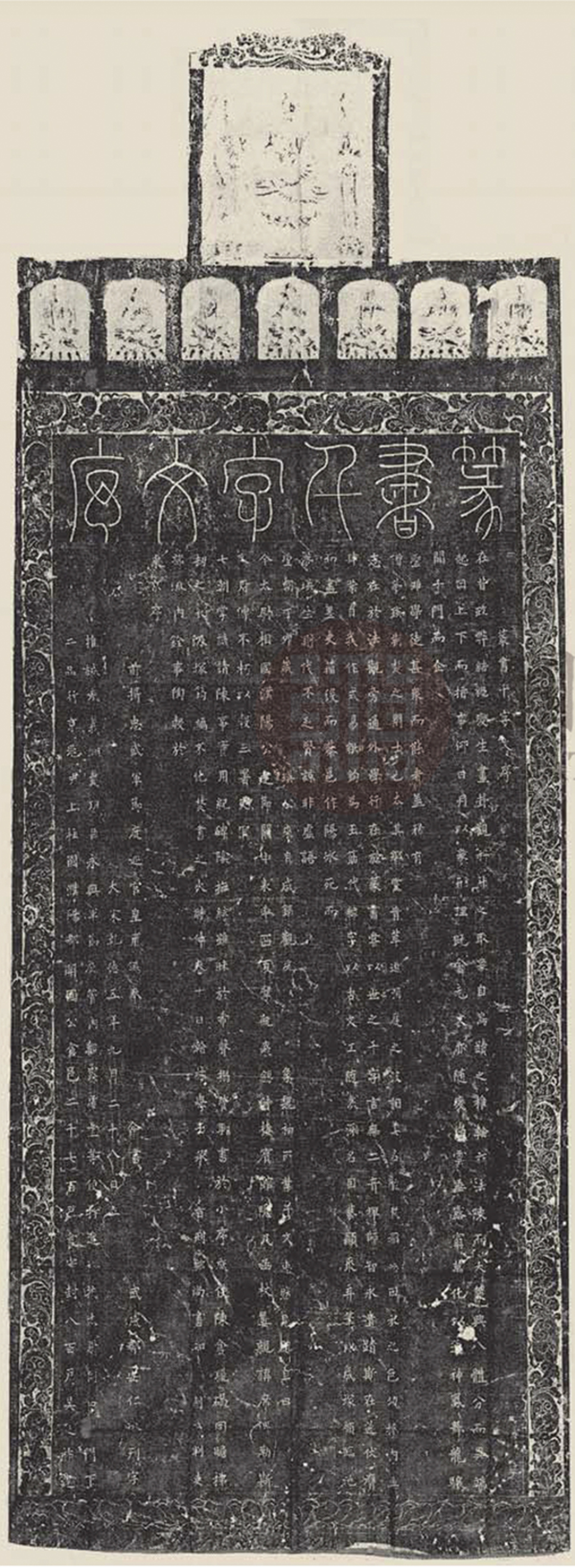

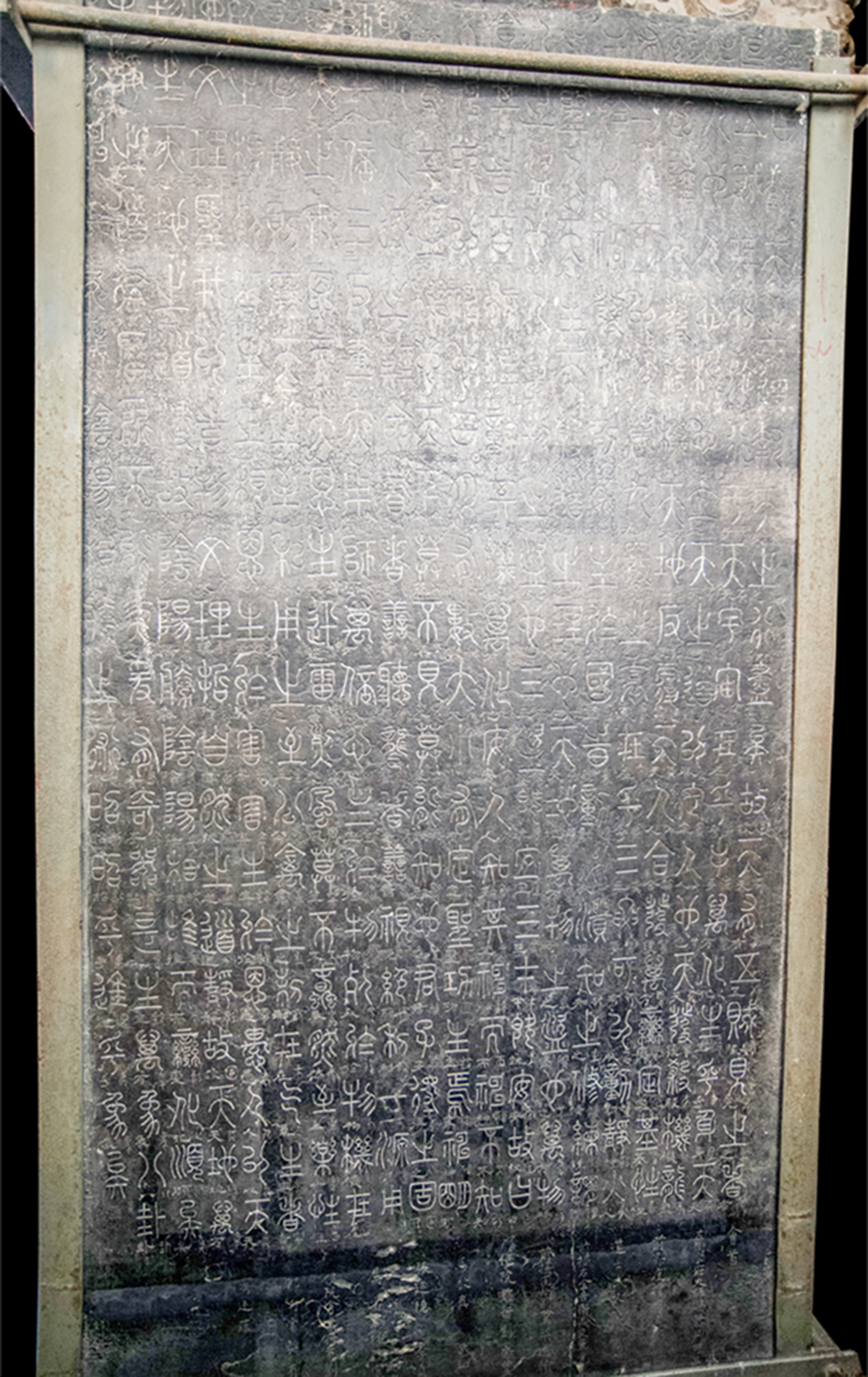

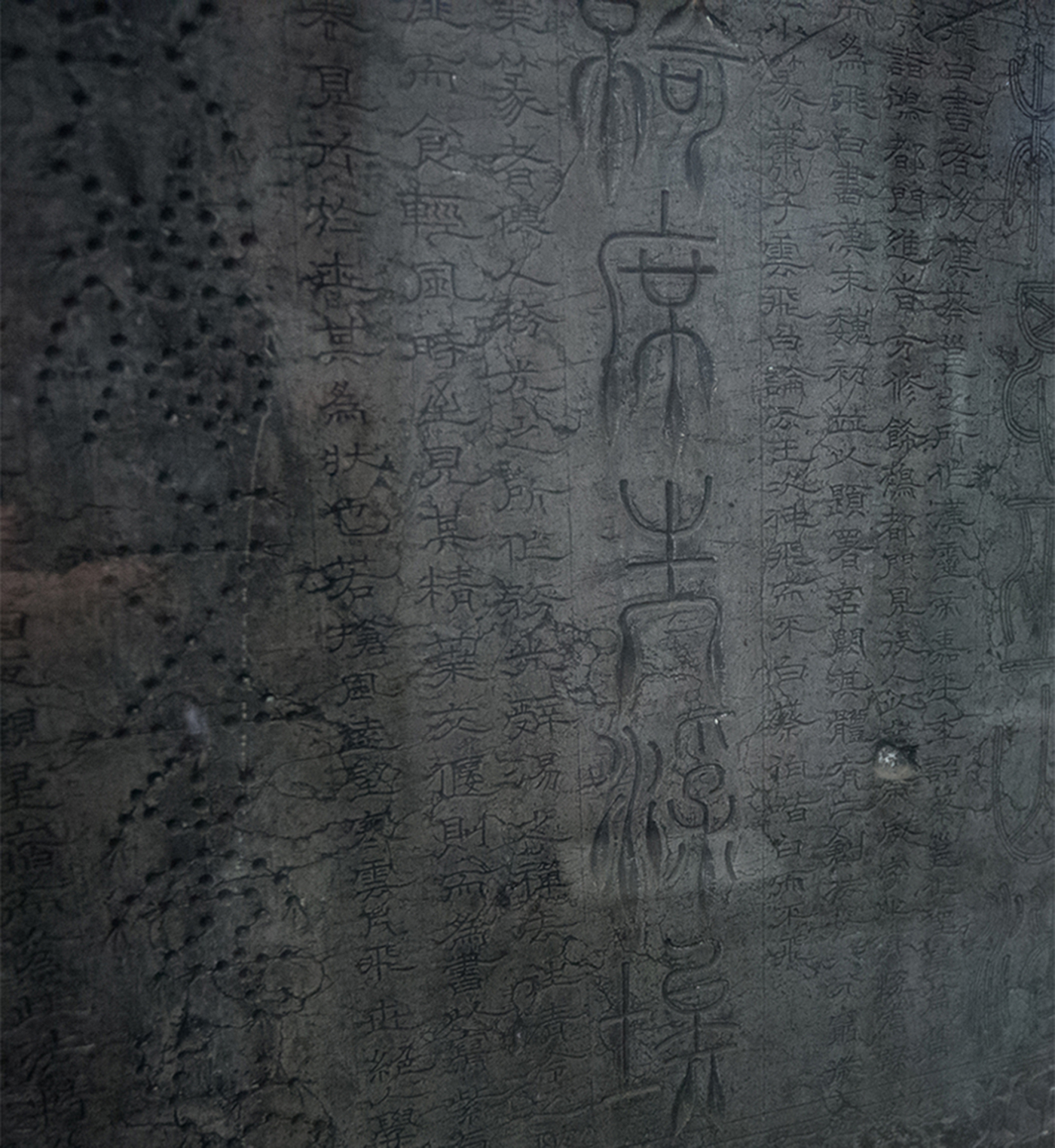

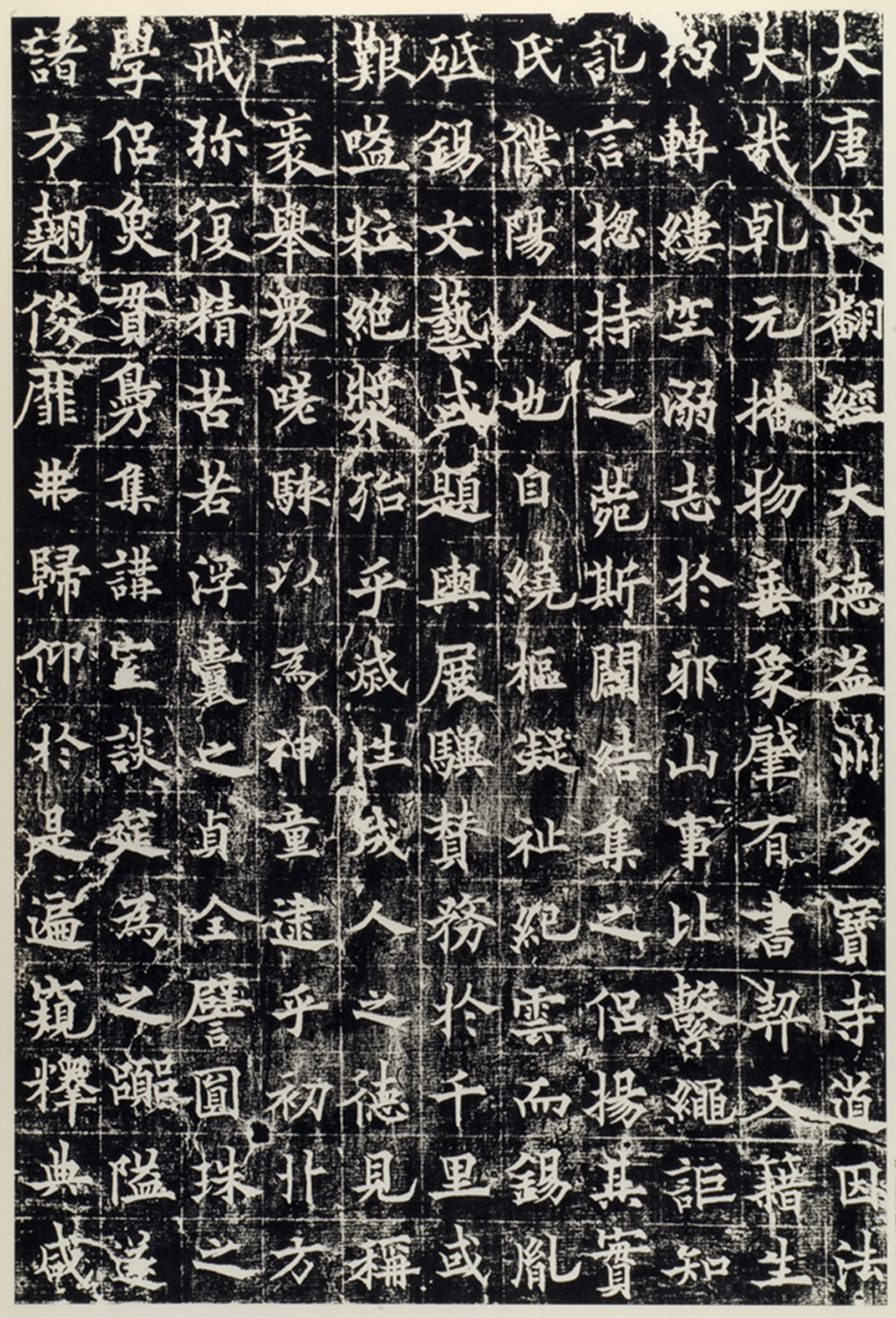

Figure 1 Partial view of The Kaicheng Stone Classics (Kaicheng shijing 開成石經), ca. 836–840. Xi'an Beilin Museum. Shenxi Provincial Museum, ed., Sui Tang Wenhua (Hong Kong: Zhonghua shuju; Shanghai: Xueshu, 1990), 148. (color online)

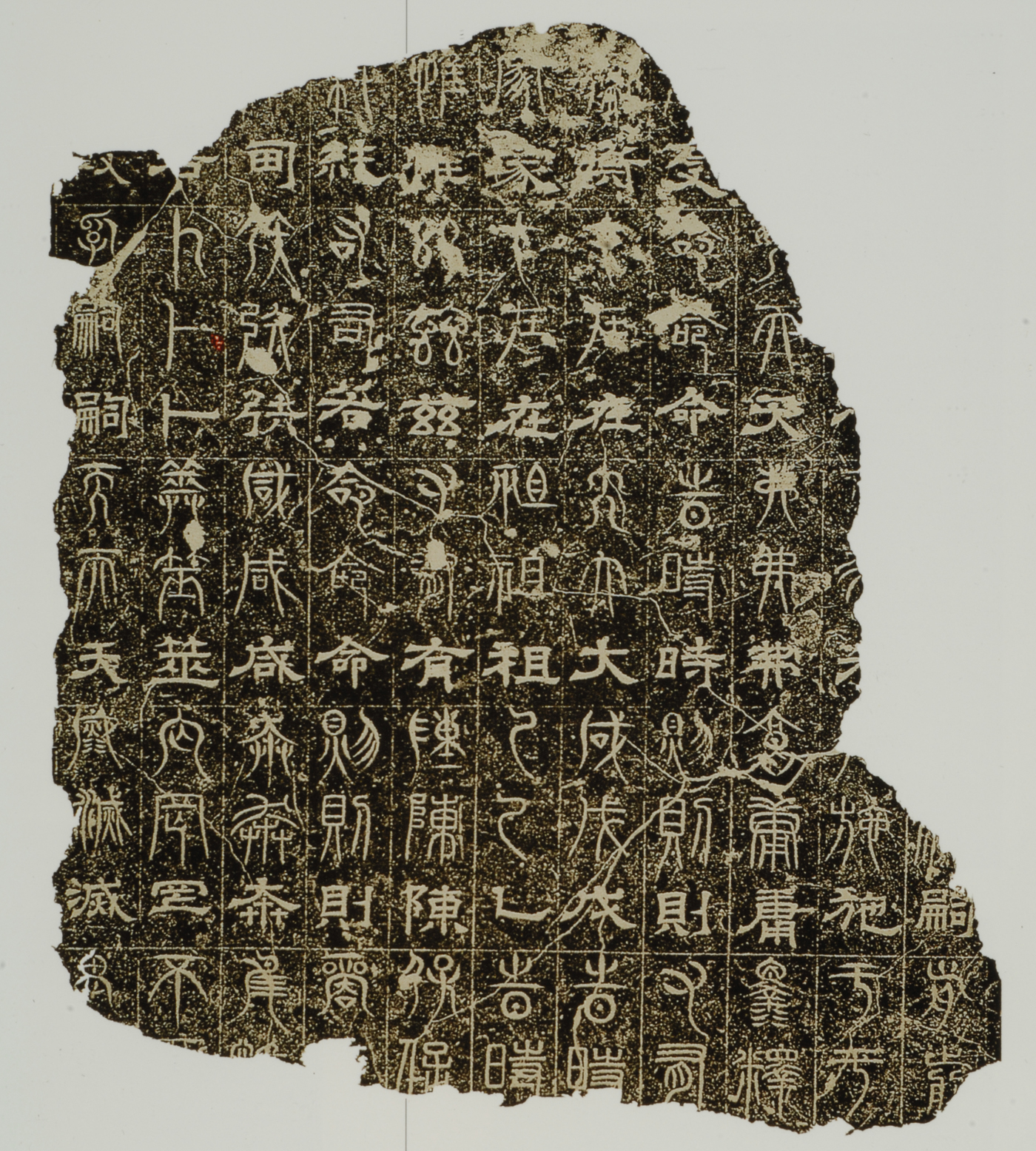

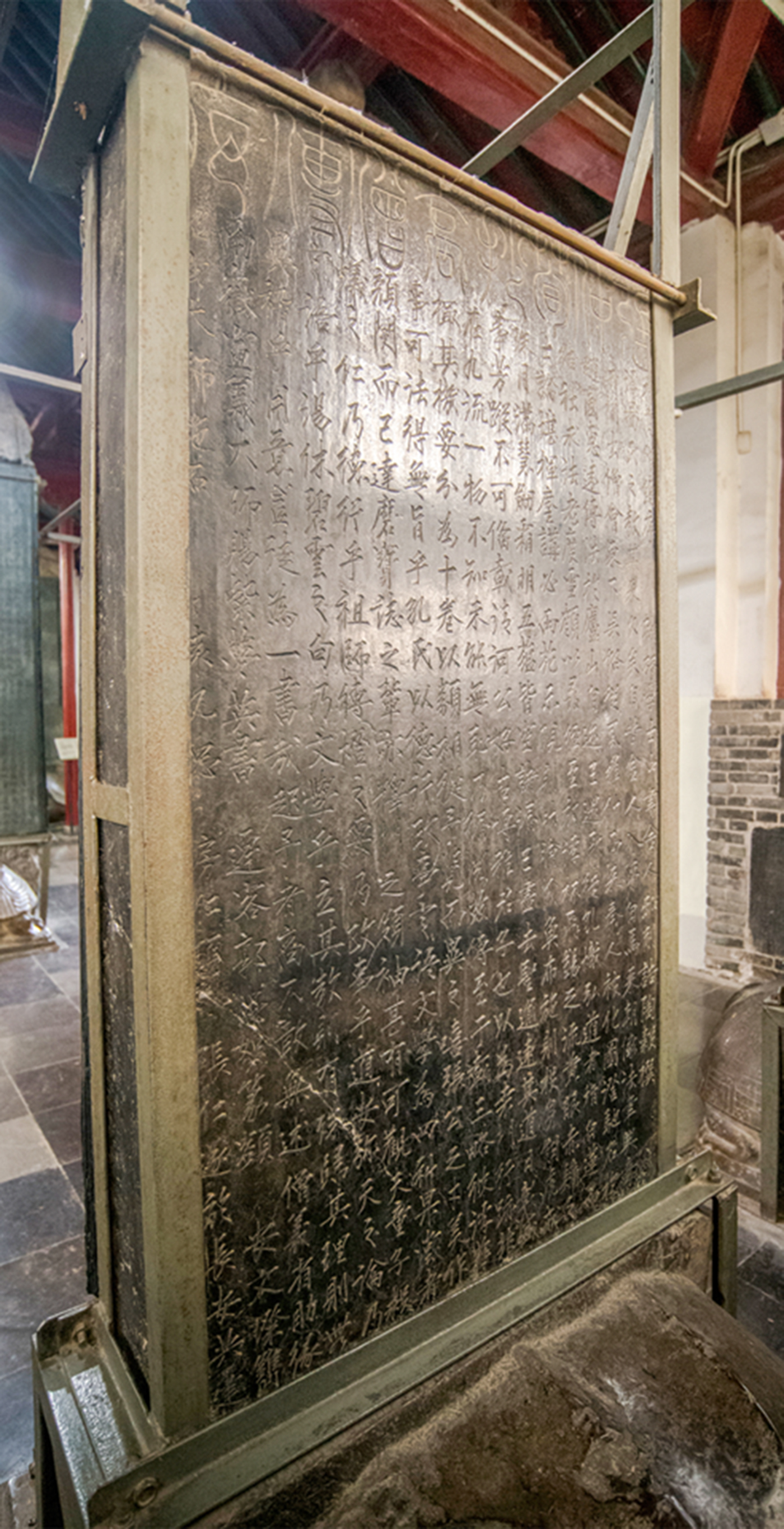

Guo Zhongshu was in no danger of resting on his laurels, for he had an exceptional interest in study. According to Zhu Changwen 朱長文 (1041–1100), writing ca. 1066, “In his youth, he was able to compose prose, excelled at the histories, the classics, and paleography (xiaoxue 小學), and was especially good at regular script calligraphy” (少能屬文, 善史書小學, 尤工真楷).Footnote 15 Although no direct information is available on the paleographic texts to which he had exposure, pride of place must go to the great Han dynasty dictionary, Shuowen jiezi (Discussion of Single-Graph Characters and Explanation of Compound Characters 說文解字) compiled by Xu Shen 許慎 (ca. 58–ca. 147 CE), which was the point of reference for all paleographic studies. Other obvious candidates are two Tang-period dictionaries, Single-Graph and Compound Characters of the Five Classics (Wujing wenzi 五經文字, 776) by Zhang Can 張參, and Compound-Character Graphs of the Nine Classics (Jiujing ziyang 九經字樣) by Tang Xuandu 唐玄度 (active first half ninth century) that were appended to the Kaicheng Stone Classics. He may also have had access through rubbings to an earlier stele-published edition of the Classics: the Wei dynasty Stone-Engraved Classics in Three Scripts (Santi shijing 三體石經, ca. 241), which employed ancient script (guwen 古文), seal script (zhuanshu 篆書), and clerical script (lishu 隸書) (Figure 2). For a studious child in Luoyang, the logical next step after success in the tongzi examination was attendance at one of the schools run by the Directorate of Education. The several schools of the Tang dynasty had at this point effectively been reduced to two: the School for the Sons of the State (Guozixue 國子學) and the National University (Taixue 太學).Footnote 16 Through an expansion in 930, the two universities together were able to accept as many as 200 students in any given year. The School for the Sons of the State was reserved for the children of prominent families; as a student who was not from such a family, Guo is more likely to have entered the National University, whose students were largely from poor elite families (rank 7 and higher) whose entry was sponsored by civil officials.Footnote 17 In Guo's day there seems to have been no formal program of teaching. From 929 on, National University students were encouraged to follow their own interests, and were tutored accordingly.Footnote 18 As a poor student, Guo would probably not have been considered eligible for the jinshi examination, which in this period was socially extremely restrictive.Footnote 19 The 1120 Xuanhe Inventory of Paintings (Xuanhe huapu 宣和畫譜) states that he obtained the less prestigious but still highly desirable mingjing 明經 degree in the Classics, which would have superseded his tongzi degree as the basis for his subsequent government appointments.Footnote 20 Although there were mingjing tracks of differing degrees of difficulty at the National University, the examination might examine only two classics and was not considered to be very rigorous. As a result, it attracted anywhere between 500 and upwards of a thousand candidates each year, most of whom had no real education beyond rote learning, and very few of whom had National University training. This led the Directorate of Education to disband the examination from 940 to 944, and also, in years when the examination was administered, to allow candidates to take the examination only once.Footnote 21

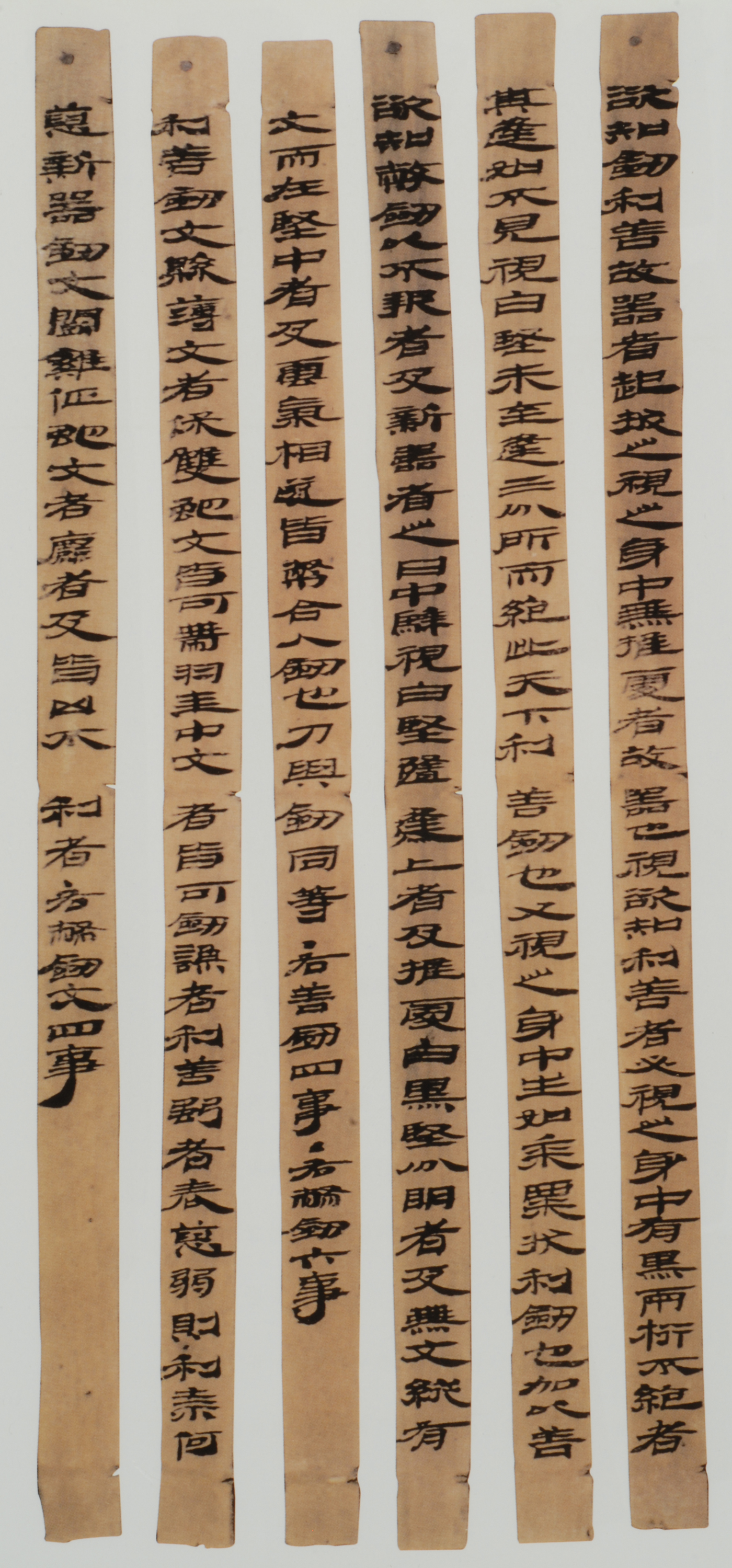

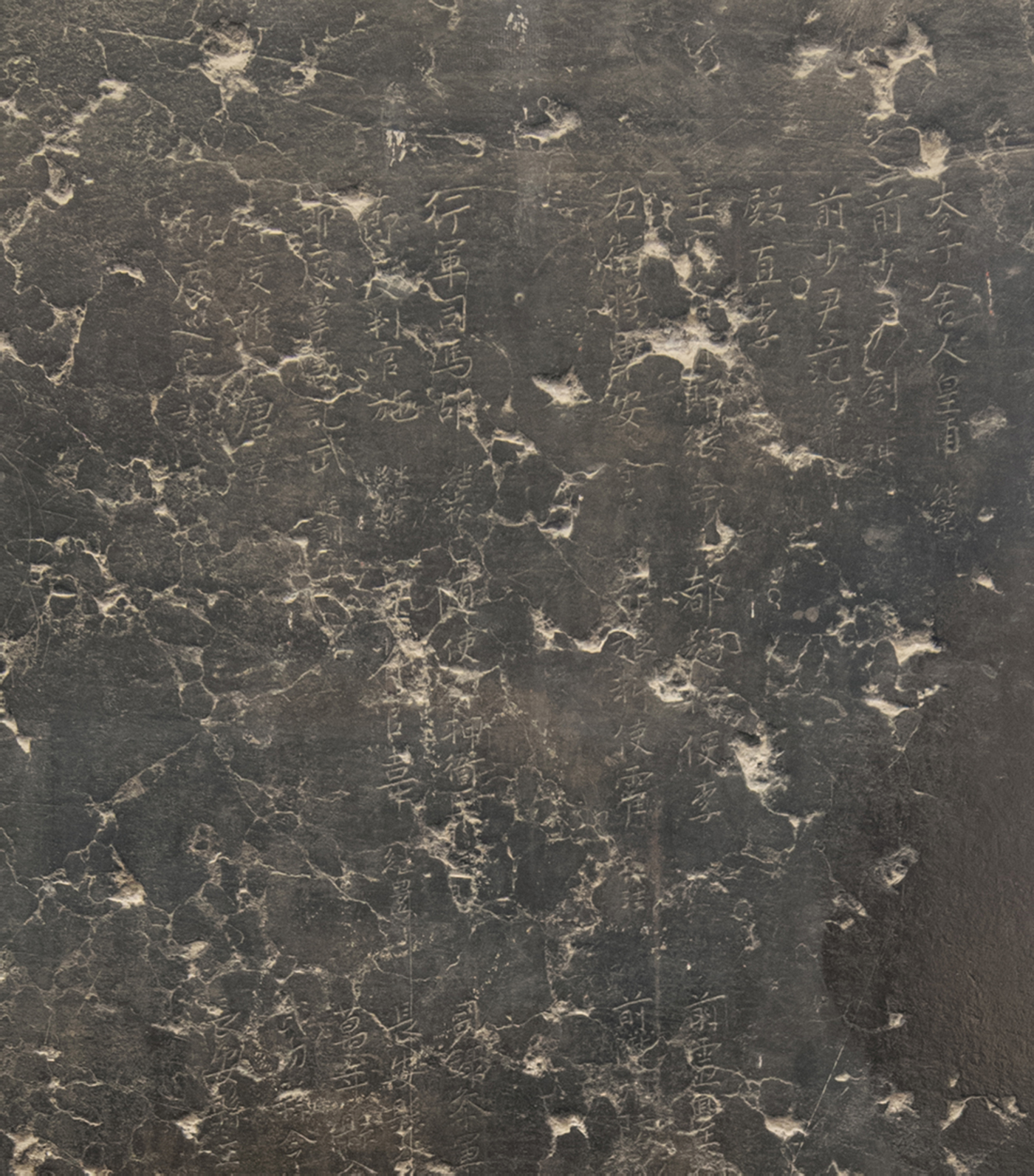

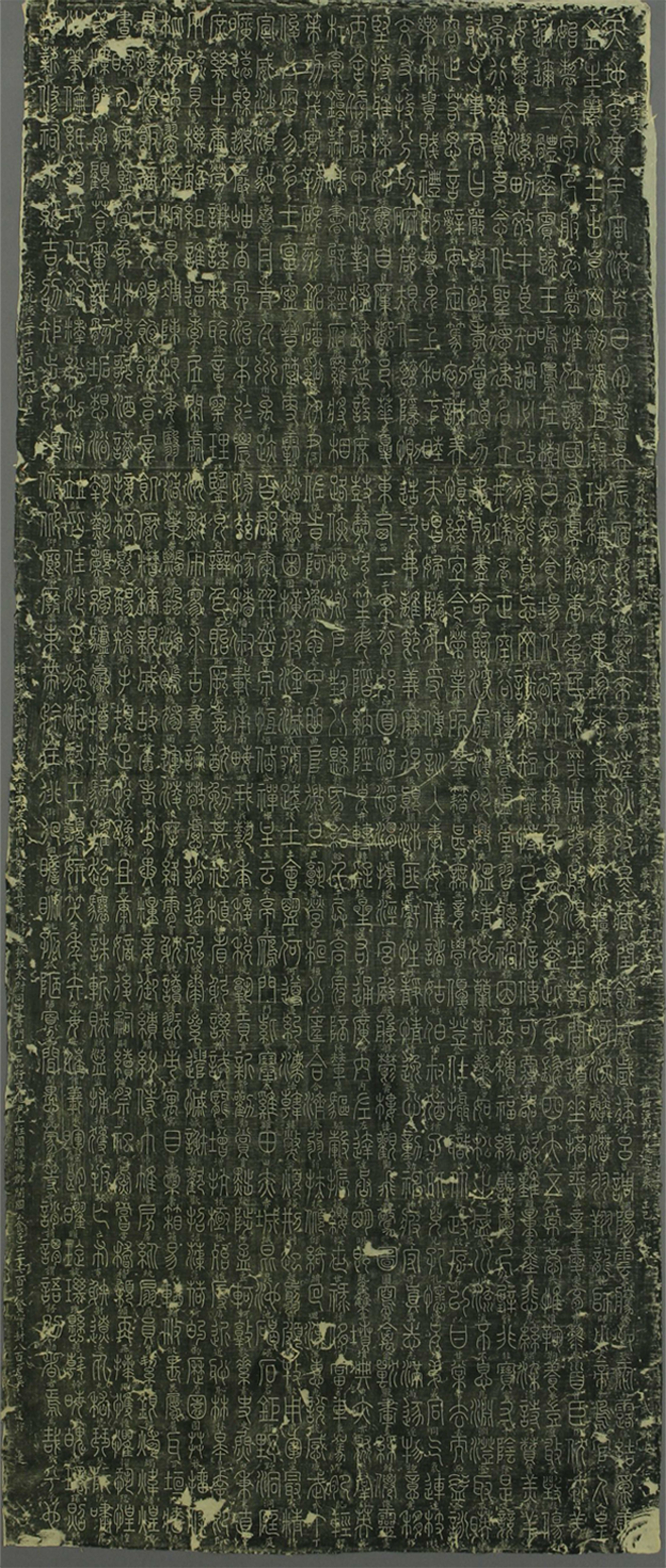

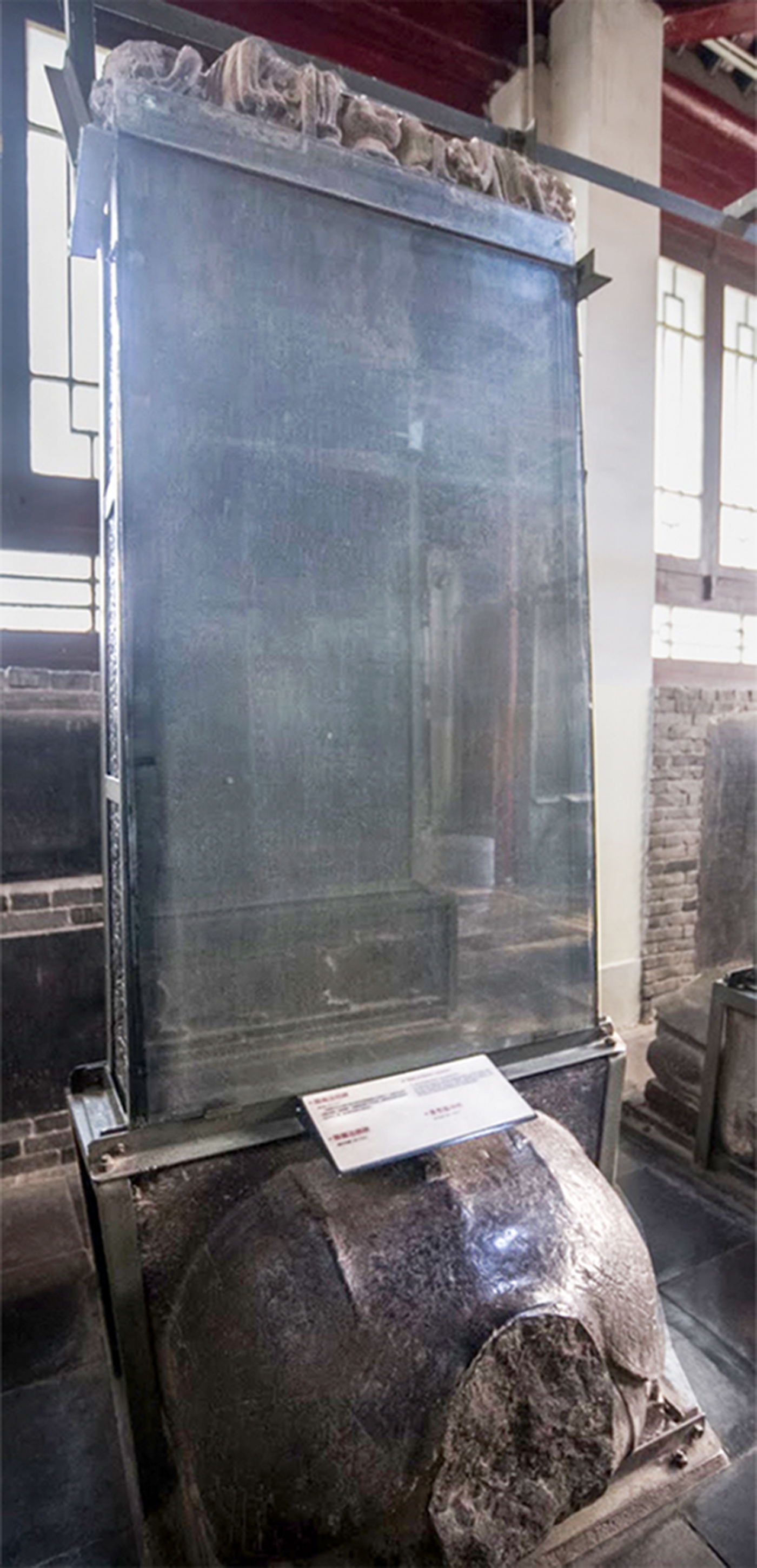

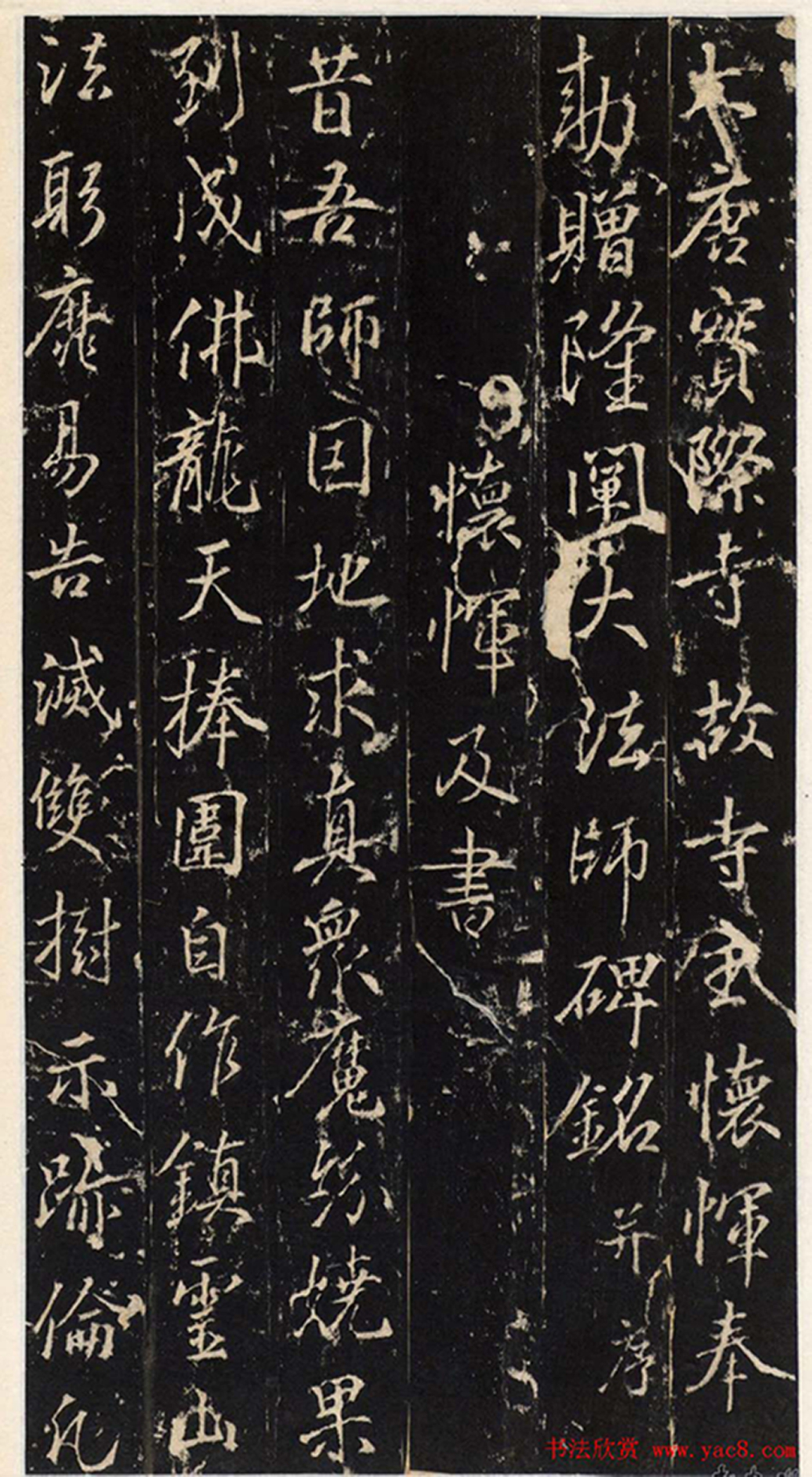

Figure 2 Ink rubbing of a fragment of The Stone-Engraved Classics in Three Scripts, ca. 241. Fragment in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing. Jin Weinuo and Xing Zhenling, eds., Zhongguo meishu quanji, 19, Shufa 1 (Hefei: Huangshan shushe, 2010), 167. (color online)

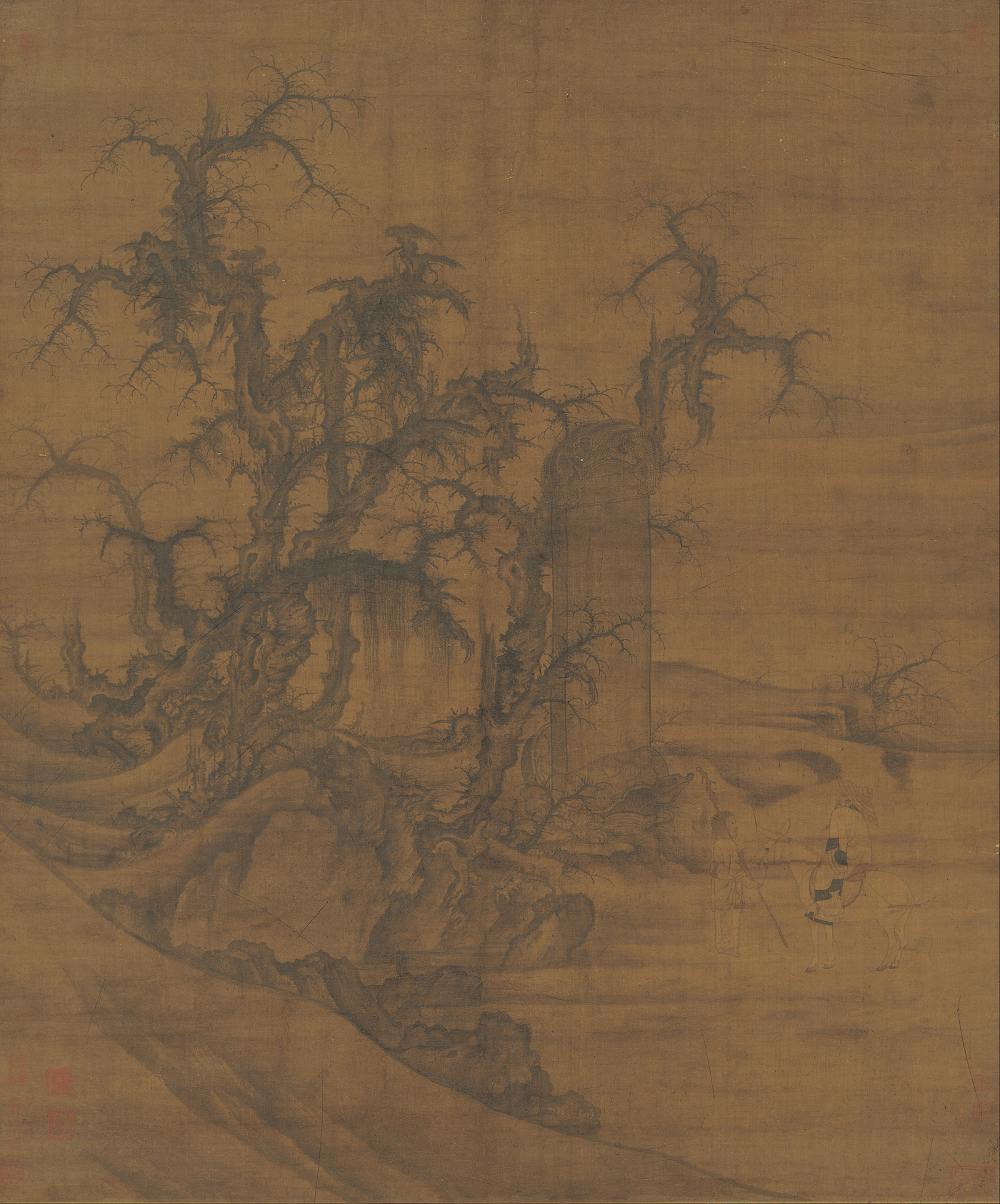

Until 935 the Directorate of Education was located solely in Luoyang, but when the Later Jin relocated the headquarters of the Directorate to Bian, in 936, the Luoyang Directorate reverted (at least nominally) to its former secondary status. Since students younger than fourteen sui were not usually accepted, Guo in principle would not have entered the National University until 941 under the Later Jin, and he would have passed the mingjing examination in either 946 or 948 (there was no examination in 947). His tuition fees were 2,000 cash at the start of his studies and a further 1,000 cash upon receiving his degree.Footnote 22 Not enough is currently known about the operation of the Directorate's universities during that period, however, for it to be possible to determine whether he pursued his studies and took the examination in Luoyang or Bian, or some combination of the two.Footnote 23 These student years laid the basis for Guo's subsequent multi-faceted reputation as a gifted prose writer, a calligrapher proficient in seal, clerical, and standard scripts, and a scholar specializing in paleography. A revealing anecdote recorded in Wudai shi bu 五代史補 refers to this period. “Someone showed him bird-trace writings that he had obtained at Dragon Mountain, and Zhongshu immediately read out the whole text for him, as if he had learnt it by heart” (嘗有人於龍山得鳥跡篆。忠恕一見輒誦如宿習。).Footnote 24 The Dragon Mountain referred to here is probably the one known today as Square Mountain 方山, located in central Henan to the south-east of Luoyang, just west of Yuzhou 禹州.Footnote 25 Yuzhou was an ancient habitation site that legend designated as the site of the capital of the Xia dynasty and subsequently as the fiefdom of the descendants of the Xia ruling house under the Shang. More reliably, under the Western Zhou, Yuzhou was the fiefdom of a younger brother of King Wu and his descendants. The city later became part of the state of Zheng 鄭, and then became the capital of one of the city-states, Han 韓, that emerged from the break-up of the state of Jin 晉 in the late fifth century BCE. The term “bird-track seal script” refers to the mythical invention of writing by Cang Jie on the basis of his observation of the tracks left by birds; it is thus a generic reference to ancient writing. Thus, although the material form of the writing that Guo Zhongshu saw is not stated, it is likely to have been an excavated object. The artifact was probably not an inscribed oracle bone from the Shang or early western Zhou period, first because oracle bones with writing have not been found in southern Henan, and second because Guo would not have been able to read the script with the ease reported in the anecdote. More likely, it was either a bronze vessel with an inscription or a fragment of a bamboo slip manuscript. However, the fact that the anecdote states only that bird-track writings were obtained suggests that writing was the very purpose of the artifact, and it may therefore have been a Warring States manuscript (Figure 3).Footnote 26 The anecdote demonstrates that already as a teenager Guo Zhongshu had developed a specialized knowledge of the history of writing.

Figure 3 Five bamboo slips from a fragmentary manuscript of the Daodejing, ca. fourth century BCE. Excavated from a Chu tomb at Guodian, Hubei. Collection of Jingmen Municipal Museum. Zhongguo fashu quanji, 1, Xian-Qin Qin-Han, Song Zhenhao editor-in-chief (Beijing: Wenwu, 2009), 78. (color online)

In a different direction, Guo's National University experience in the 940s must have been colored by the Directorate of Education's commitment to publishing new editions of the classics using the modern technology of woodblock printing. This innovative project entailed close attention to paleography, since the Directorate sought to establish standardized texts without the many variant characters that littered the Stone Classics.Footnote 27 Guo would certainly also have been aware that the Directorate's enterprise was a response to recent state-sponsored printing projects in the contemporary Wu-Yue and Southern Tang kingdoms, and thus belonged to a larger quasi-international world of scholarship.Footnote 28 Guo Zhongshu studied at the National University during a period of intense publishing activity by the Directorate of Education. In 927, the Luoyang Directorate had published its first printed book, a new edition of the Tang political text, Essentials of Government in the Zhenguan Reign (Zhenguan zheng yao 貞觀政要) by Wu Jing 吳兢 (670–749).Footnote 29 And in 932, at the urging of two Confucianist ministers, Li Yu 李愚 (d. 935) and Feng Dao 馮道 (882–954), the Directorate began work on an official woodblock-printed edition of the Nine Classics that, as it turned out, would take twenty-one years to complete.Footnote 30 Unflaggingly supported by the long-serving Feng Dao, the printing project continued under both Later Jin emperors, Shi Jingtang 石敬瑭 (r. 936–942) and Shi Chonggui 石重貴 (Chudi, r. 942–947). In 943, the Directorate published the Five Classics, offering it for sale ahead of the complete set of Nine Classics.Footnote 31 This would have been a major event in the life of a sixteen-sui student on the mingjing track. All editorial work must have come to a halt, however, when the Khitan army occupied Bian in 947 for several months, bringing the Later Jin to a brutal end. Yet, as early as the following year, under the short-lived Later Han dynasty, the Directorate resumed work on the remaining four Confucian classics (Zhou li, Yi li, and the Gongyang and Guliang commentaries on the Spring and Autumn Annals), which would eventually be published as part of a complete set of Nine Classics under the Later Zhou in the summer of 953.Footnote 32

The Khitan occupation of Bian was unprecedented. Shatuo rulers had generally maintained friendly relations with the Liao. But whereas Shi Jingtang had allowed the Later Jin to be a client state of an increasingly powerful Khitan empire, Shi Chonggui turned against the Liao. The Liao emperor, Yelü Deguang 耶律德光, led his troops down into Hebei at the end of 946 and defeated the Later Jin army. He then entered the capital, Bian, on the first day of the New Year, 947, and for a few months occupied the city, making the administrative changes appropriate to the absorption of Later Jin into the Great Liao empire. These changes included the downgrading of the capital to Bianzhou, corresponding to its former status within the Tang empire. Then Yelü Deguang abruptly changed course and instead decided to head back north, taking with him the Later Jin court's assets of personnel, repositories of knowledge, ritual tools, and military matériel. In the view of Naomi Standen, whose reconstruction I am following here, no central government official would have been exempt. If he did not lay low in order to avoid being caught up in the events, Guo's lowly student status would conceivably have protected him from becoming a prisoner of war. He certainly knew of, if not witnessed, the rounding-up of useful individuals and the pillaging of useful things, including the Directorate of Education's libraries, to take back to Liao territory.Footnote 33

In an unexpected turn of events, Yelü Deguang took ill and died on the way north. Subsequently many of the captured Later Jin officials, including Feng Dao, were released. They returned to Bian, which in the interim had become the capital of the Later Han dynasty.Footnote 34 Indeed, the founding of Later Han in northern Shanxi in early 947 by Liu Zhiyuan 劉知遠 (895–948), who continued Shi Chonggui's hostility to the Liao, had been one of the factors precipitating Yelü Deguang's abandonment of Bian. Having escaped the Khitan net himself, Guo made his first public intervention as a scholar in 948 under the Later Han, in either Bian or Luoyang. In the fourth month of 948, Guo, still only 20 sui, composed a preface to the Buddhist Tripitaka, Preface on the Purpose of the Triptaka (Dacangjing zhixu 大藏經旨序), which was engraved on a stele. Guo wrote the seal-script title for the stele himself, but it was another young man, Yuan Zhengji 袁正己, from Runan 汝南 in southern Henan, who wrote out the text itself in regular script (kaishu 楷書) calligraphy, probably in the Ouyang Xun style for which Yuan was to become known.Footnote 35 Neither the inscription nor the text has survived, but there are reasons to think that it was connected to a former Confucian scholar turned Buddhist monk, Kehong 可洪. In 939, Shi Jingtang had ordered the inclusion in the Tripitaka of the 450 juan of Compendium of Sounds and Meanings in the Tripitaka (Dacangjing yinyi suihan lu 大藏經音義随函录), which Kehong had just submitted to the throne.Footnote 36 Kehong's text was modelled on Textual Explanations of Classics and Canons (Jingdian shiwen 經典釋文) by the Tang classicist, Lu Deming 陸德明, of which the Directorate of Education would print a new edition in 959 (see Figure 10). In his preface to Compendium of Sounds and Meanings, Kehong states, “without written language there is no way to transmit the purpose [of sutras]” (非文字無以傳其旨).Footnote 37 If the shared word “purpose” is not simply a coincidence, therefore, the text transcribed by Yuan Zhengyi with a seal script title by Guo Zhongshu may have been this very preface to the Compendium of Sounds and Meanings. The Compendium, it is worth noting, made good use of Xu Shen's Discussion of Single-Graph Characters and Explanation of Compound Characters, seen in Figure 4 in a ninth-century manuscript version, on which Guo himself would soon publish his own specialist study.Footnote 38

Figure 4 Xu Shen, Discussion of Single-Graph Characters and Explanation of Compound Characters (Shuowen jiezi), ninth century. Manuscript handscroll, Japanese private collection. Jin Weinuo and Xing Zhenling, eds., Zhongguo meishu quanji, 20, Shufa 2 (Hefei: Huangshan shushe, 2010), 389. (color online)

Xuzhou, 948–950

Later in 948 Guo obtained his first appointment as an official, when he was recruited by Liu Zhiyuan's nephew and adopted son, Liu Yun 劉贇. Liu had just been appointed Military Commissioner (jiedushi 節度使) of the Wuning Circuit, based in Xuzhou due east of Bian at the edge of Later Han territory, in the north of present-day Jiangsu province, on the eastern frontier with Southern Tang.Footnote 39 The unexpected death of a seasoned general had created a vacancy, which Liu Zhiyuan filled by appointing Liu Yun, on the eve of his own unexpected death on March 10. All sources concur that Guo Zhongshu was ruoguan 弱冠 when he entered Liu Yun's entourage, and the circumstantial evidence of examinations presented earlier confirms that he was exactly 20 sui. Xuzhou was a place of strategic military importance for any Luoyang- or Bian-based dynasty's relations with the Southern Tang kingdom to the south and the Liao empire to the north. Guo Zhongshu's role on Liu Yun's staff is not entirely clear. According to the Song History, he was an advisor (congshi 從事) with the official rank of Judge (tuiguan 推官), but these titles give no indication of the range of his actual functions. In a general sense, though, Guo was following what was perhaps the most effective path to advancement that a mingshi graduate could take, which was to join the secretariat of a powerful man, either a high civil official in the central government or a Military Commissioner away from the capital. Military Commissioners, who founded all of the Five Dynasties and most of the Ten Kingdoms, constituted a military aristocracy with princely powers in the areas they controlled.

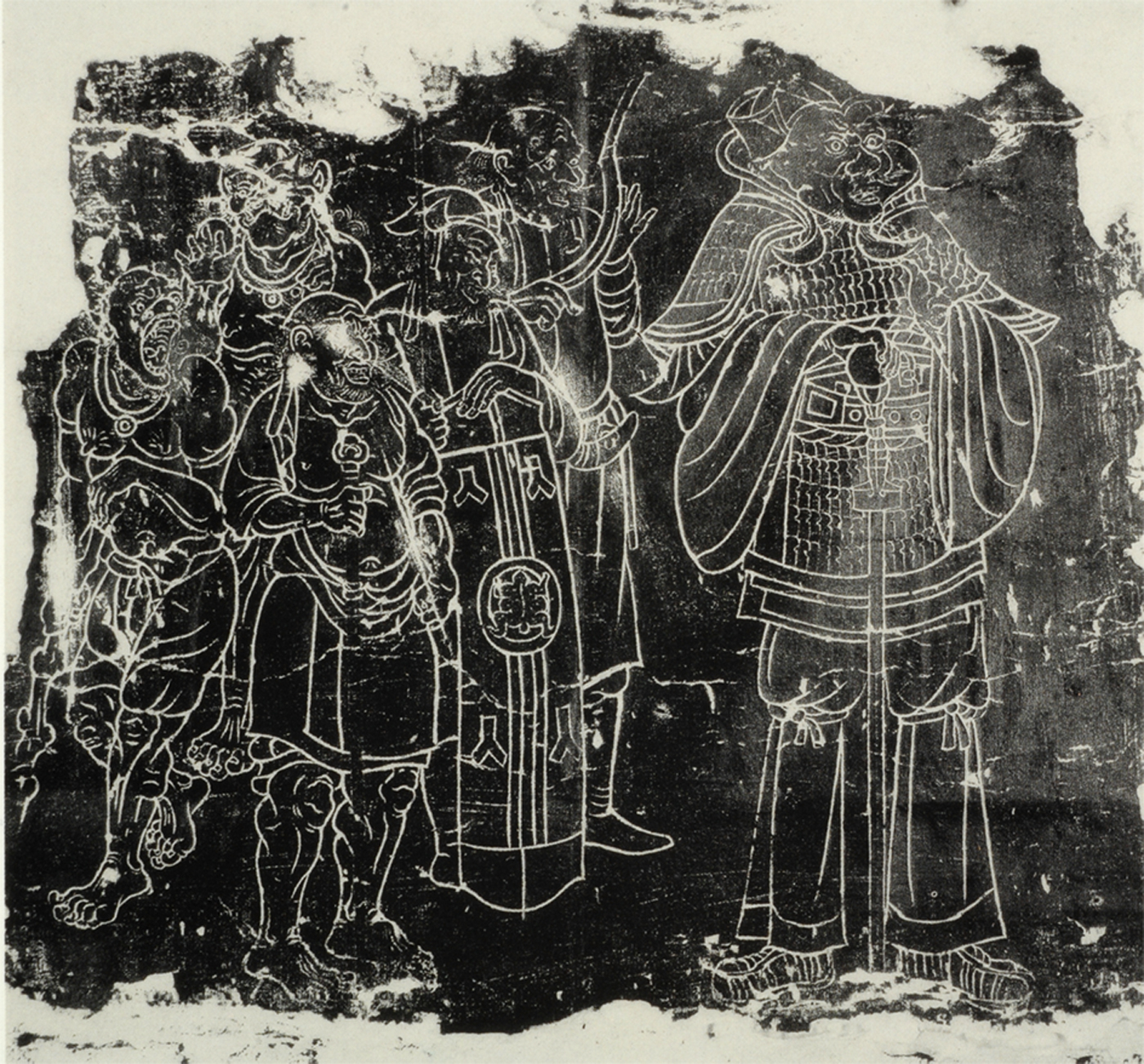

These generals and their families developed a distinctive visual and material culture. In recent years, archaeologists have excavated several lavish tombs of Military Commissioners, some turned rulers, in north-central China and beyond.Footnote 40 To these tombs can be added a few recently excavated, imperially authorized honorific steles (dezhengbei 德政碑) that were originally erected above ground as public monuments in honor of their achievements.Footnote 41 A number of Buddhist chapels also survive from the period of the Guiyi Commandery's control of Dunhuang. These tombs, steles, chapels, and temples, together with descriptive texts from the period, attest to a pattern in the way the generals’ two worlds of military action and civil life were represented. The professional military life of the Commissioners was represented largely textually, on epitaph tablets (muzhiming 墓誌銘) placed in the tombs, and on honorific steles above ground. Visual references to the military life are rarer: the most common are depictions of guardian deities in tombs, temples, though one also finds representations of military processions and orchestras, as well as depictions of the animals pursued in hunting (tomb of Meng Zhixiang). The Chinese Military Commissioners, whatever their ethnic origins, differed from their contemporary Khitan counterparts in not including portraits of their favorite horses in their tombs. The bulk of the visual representations depicted instead the pleasurable domestic life of the palace residence. In fact, in several of the tombs the Commissioners were buried together with their wives, or the wife had her own adjoining tomb. The tombs reveal a striking devotion not only to luxury but also to the latest fashions. Every excavated tomb has proven to be large; every tomb has its own unique design. The tomb decorators were always the best available, working in the latest styles of painting, sculpture, or sculptural relief. The tomb as a whole had as one of its purposes to enact an inhabited underground mansion or palace with equally up-to-date and luxurious furniture, objects, and wall decoration. Female attendants are depicted wearing fashionable attire. These characteristics of tomb decoration are echoed in the paradise scenes of chapels and temple halls associated with the military aristocracy, which translate the vision of a pleasurable life (spiritually earned in this case) into an exotic register.

The preoccupation with pleasure seen in the art that the generals sponsored chimes with Tao Gu's 陶穀 (903–970) near-contemporary description of the Five Dynasties fashion for elaborate banquets:

During the fifty years of the Five Dynasties, family names claimed dynasties one after another like wheatcakes being flipped from the oven, and the officials and nobles were ever more excessive [in their conduct]. People of no merit encountered the magnanimity of the rulers, and became rich and powerful for no reason, treating the security of their states as if Qin and Yue had not plotted against each other. And so generals, ministers, and men of high status came to steal pleasure from the [ephemeral] enjoyment of banqueting. These, the powerful men of the day, had even more appreciation for the paraphernalia of banquets, and wherever there was luxurious food from land or water they would gather in front of it. Banquets on the scale of a hundred square feet were not unusual, where they would set up two tables, one on either side, supporting lustrous flowers and jade-like fruit; vegetables, bamboo shoots, and minced fish; sweetmeats and intoxicants, to the tune of several hundred varieties. They called this practice “paired platforms for dishes,”Footnote 42 and no imperial banqueting kitchen or official's household was able to match it.

五代五十年間, 易姓告代。如翻鏊上餅然, 官爵益濫。小人乗君子之器, 富貴出於非意, 視國家安危如秦越不相謀。故將相大臣得以竊亨燕安。當時貴勢以筵具更相尚。陸珍水異, 畢集於前。至於方丈之案不勝列, 傍挺二案, 翼之珠花玉果, 蔬荀鮓醢, 糖品香劑, 參差數百, 謂之綽楔臺盤。御宴官家例不能辨。Footnote 43

Given that Military Commissioners were men of action, it is not surprising that in addition to these outdoor banquets they also felt a deep affinity for arts of performance. Visual representations of music, dance, and storytelling, and references to their own practice of “flying white” (feibai 飛白) calligraphy or their polo-playing, are variously found on epitaph tablets and steles, and in pictorial representations in tombs, chapels, and temple halls.

This is the distinctive world that Guo Zhongshu entered when he joined Liu Yun's entourage in Xuzhou as a fresh-faced National University graduate from a modest family background. With an insecure new eighteen-sui emperor, Liu Chengyou 劉承祐, on the throne, who was surrounded by powerful generals with designs on power, Liu Yun's own position was very uncertain. The brief account of his Wuning Commandery tenure in Jiu wudai shi 舊五代史 begins with a discussion of portents, which give a sense of the tense atmosphere in his entourage. Although Liu's tenure began auspiciously enough in the eighth month of 948 with the appearance of a multi-colored cloud, in the winter of 949 a flock of unusual birds resembling phoenixes congregated in a tree in the courtyard of Xianbi Hall (probably the main hall of the yamen). Xianbi 鮮碧, meaning rare jade, is a homophone for the Xianbi or Xianbei 鮮卑 people; the name may have been chosen as a reference to the Liu family's Shatuo origins. A visitor who observed the birds is said to have commented sadly and ominously: “When wild birds enter a residence, it means that the master of the house is going to disappear, no-one knows where” (野鳥入室, 主人將去).Footnote 44

Aside from his military duties, Liu Yun also had ideological responsibilities. His adoptive father, Liu Zhiyuan, sought to reinforce the legitimacy of the Later Han dynasty by claiming to be descended from the founder of the Han dynasty, Liu Bang, who was born near Xuzhou. An ancestral temple already existed on Mt. Mangdang 芒碭山 to the east of the city. To reinforce the claim of ancestry, however, Liu Zhiyuan ordered the construction of a second ancestral temple on a site not far from that of the original temple, on the grounds that textual evidence showed the new site to be Liu Bang's correct birthplace. The construction of this temple was Liu Yun's administrative and, no doubt, financial responsibility as Wuning Military Commissioner. When the building was completed in 949, it was Guo Zhongshu who transcribed in bafen clerical script calligraphy the text of a stele inscription commemorating the temple's construction, Stele Commemorating the Renovation of the Ancestral Temple of Emperor Gaozu of the Han Dynasty (Chongxiu Gaozu miao bei 重修高祖廟碑).Footnote 45 The stele was erected at the site of the temple.

Guo must have spent much of the two years or so that he spent in Liu Yun's entourage on scholarship. The proof is that the following year, 950, in the seventh month, he completed his first scholarly study at the age of only 22 sui. Entitled Origins of Compound Characters in the “Shuowen” (Shuowen ziyuan 說文字源), the now-lost book was a paleographic study of Xu Shen's Discussion of Single-Graph Characters and Explanation of Compound Characters. This was not simply a private project, however. Guo's transcription of Origins of Compound Characters in the “Shuowen” was engraved at the time on a stele in Xuzhou, perhaps in the grounds of the city's Confucius Temple or prefectural school. We owe our knowledge of the stele to the great compendia of inscriptions by Ouyang Xiu 歐陽修 (1007–1072) and Zhao Mingcheng 趙明誠 (1081–1129).Footnote 46 Both writers discuss the stele rubbing as an example of Guo Zhongshu's xiaokai小楷 calligraphy, but Zhao's table of contents, which gives the more precise date, lists it as a combination of seal script (zhuan 篆) and xiaokai. This probably does not mean that there was a seal script title above a stele text written entirely in xiaokai, but rather that the characters Guo was explaining were basically in small-seal script (following the model of Discussion) with commentaries in xiaokai. If Ouyang and Zhao did not comment on the seal script headings as calligraphy, it may be because the headings were not entirely in small-seal script. Discussion included a number of rare ancient script (guwen 古文) characters for which there were no seal script equivalents, and Guo is likely to have done the same. From the point of view of the eleventh-century writers, ancient script, current in the Warring States period, belonged more to the realm of writing than calligraphy.

To understand why Guo Zhongshu wrote Origins of Compound Characters in the “Shuowen,” and why his efforts should still concern us today, one has to know something about Discussion of Single-Graph Characters and Explanation of Compound Characters itself and how it circulated in Guo's time. The author, Xu Shen, composed the dictionary in order to give his Eastern Han contemporaries access to the meanings of words in texts that had originally been written in scripts that few people could read any more. In Xu Shen's time these texts largely circulated in versions that used small-seal script or clerical script—the two new scripts that had been introduced in the third century BCE to replace the earlier scripts, and which had been imposed at the price of the deliberate destruction of manuscripts written in the earlier scripts. Most important for Xu's purposes was ancient script, since this was the script used in surviving or excavated bamboo slip manuscripts, but the dictionary also included characters drawn from even earlier scripts. Wherever possible, Xu Shen presented the word in small-seal script form; but when no seal script equivalent existed for a character, he used the original ancient script or an even earlier script. The dictionary's explanations, meanwhile, were in clerical script. Xu Shen recognized that Chinese writing had an organizing principle: when characters combined graphs, one of the graphs identified a group of related characters to which the compound character belonged. The individual graphs were called wen when they appeared on their own as single-graph characters, and pianpang (what we know todays as radicals) when they became organizing components of a compound character. Much like a modern Chinese zidian dictionary, Discussion had individual entries for both the organizing character component and all its related compound characters.

In Guo Zhongshu's time, when the Classics had long since been translated into the more modern regular script, Discussion of Single-Graph Characters and Explanation of Compound Characters remained the major reference work for understanding the meanings of Chinese characters, no matter what script they were written in. Xu Shen's original version no longer existed, however; instead, tenth-century scholars used an updated version created by the eighth-century paleographer and calligrapher, Li Yangbing 李陽冰 (ca. 713–787) (see Figure 4). Li Yangbing's version of Discussion translated all the remaining ancient and earlier script headings into small-seal script as well. Yet Li Yangbing's updating did not make the dictionary any easier to use. One of Guo Zhongshu's older contemporaries, Lin Han 林罕 (897–949 or later), complained:

For us today, the Shuowen is huge, is dense with text, and takes up many scrolls; it is hard to find what one is looking for, and going back and forth one ends up confused and not knowing where to go.

今以《說文》浩大, 備載群言, 卷軸煩多, 卒難尋究, 翻致懵亂, 莫知指歸。Footnote 47

Moreover, tenth-century scholars were starting to be aware that the translation of ancient script into any more recent script had a potential for error that compromised access to the wisdom and knowledge of the Ancients. Ancient script itself, which had never completely disappeared, was becoming an object of fascination and paleological study.

The aforementioned Lin Han, a scholar from Sichuan, was a pioneer. During the years 926 to 933, Sichuan was briefly absorbed into the Later Tang empire, and in 931 Lin took advantage of the resulting travel possibilities to visit Luoyang. A period of illness during his visit led him to start compiling a new edition of Discussion of Single-Graph Characters and Explanation of Compound Characters.Footnote 48 After falling ill again in 935, back in Chengdu, a year after the establishment of the Later Shu regime, Li returned to his research. Since his illness lasted some years, he had the time to revise his earlier work. In 937 he completed the now-lost edition, entitled Comprehensively Annotated “Shuowen” (Shuowen jijie 說文集解), which circulated in manuscript form. For this edition, Lin Han combined the explanations in Li Yangbing's earlier edition with material from elsewhere, such as the explanations of clerical script characters in another eighth century text, Imperially Established Sounds and Meanings of Single-Graph and Compound Characters (Sheng zhi Kaiyuan wenzi yinyi 聖製開元文字音義, 753).Footnote 49 Lin Han then went on to address the difficulties that using Discussion entailed in a new work that again has not survived, Brief Discussion of the Origins of Compound Characters [in Relation to] Character Components (Ziyuan pianpang xiaoshuo 字源偏旁小說).Footnote 50 Lin here isolated the 541 single-graph characters of the dictionary, which he probably wrote out in seal script. Beneath each one, he listed the compound characters that were derived from the single-graph character when it was used as a radical, and specified the pronunciation in each case, using a clerical script homophone when the character was well known and the qieyun system when the character was more obscure. Lin Han's innovative reference work provided the user of Discussion with a convenient way of seeing and exploiting the logic of Chinese writing that Xu Shen had identified, but which the organization of his dictionary tended to obscure. Lin Han had Brief Discussion of the Origins of Compound Characters [in Relation to] Character Components engraved on a stele in Chengdu in 949 “to avoid the errors of copying” and the labor associated with manuscript transmission, since ink rubbings could be made from the stele.

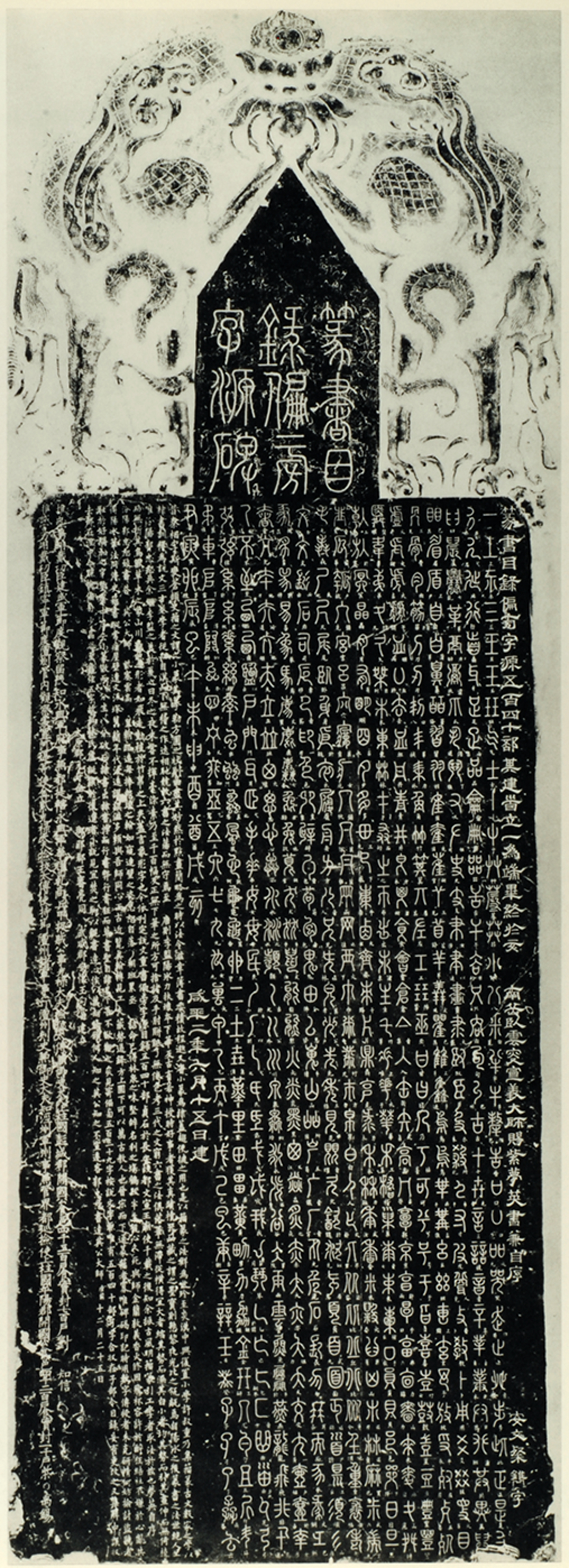

Guo Zhongshu's Origins of Compound Characters in the “Shuowen” appears to have been lost before the end of the Song dynasty. All we concretely know about it comes from a brief comparison that Guo made in the 960s with a similarly titled work by a third scholar, a Buddhist monk from the former territory of Chu, Mengying 夢英 (934/6–999 or later). Commenting on Mengying's Tabulation of Character-Component Origins of Compound Characters (Mulu pianpang ziyuan 目錄偏旁字源, see Figures 73–74), Guo wrote: “I notice that in what you sent me there are 539 [actually 540] characters listed as character components. Now, Origins of Compound Characters in the “Shuowen” only had 540 [actually 539] headings, because jie 孑 is listed under the zi 子heading, but now your Tabulation has rashly changed it back again [to a heading of its own]” (見寄偏旁五百三十九字, 按《説文字源》唯有五百四十部, 「孑」字合收於子部, 今《目録》妄有更攺之。).Footnote 51 Comparing these remarks with Tabulation of Character-Component Origins of Compound Characters, which does survive as a stele inscription (Figures 69–70), one can infer that Guo's earlier book made a similar tabulation of the character components (pianpang 偏旁) from which compound characters are generated. In the same letter, Guo Zhongshu goes on to note the deficiencies of Lin Han's Comprehensively Annotated “Shuowen,” and also writes disparagingly of Lin's Brief Discussion of the Origins of Compound Characters [in Relation to] Character Components:

Moreover, in Comprehensively Annotated the character ei is listed under the qu heading in the accompanying note. And, checking his character components, he is short five characters—jing, suo, zhi, gui, and xuan. So you can see that Lin's work is not properly grounded and will mislead later investigators. If you see his Brief Discussion, you might as well burn it.

又《集解》中「誒」收去部, 在注中。今點檢偏旁, 少「晶、惢、至、龜、弦」五字, 故知林氏虛誕, 誤於後進者, 《小説》 見,冝焚之 。.Footnote 52

For all Guo's bluster, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that his Origins of Compound Characters in the “Shuowen” of 950 was directly modelled on Lin Han's Brief Discussion of the Origins of Compound Characters [in Relation to] Character Components, published in 949. Mengying's later Tabulation of Character-Component Origins of Compound Characters—the only one of these three very similar studies to survive—no doubt owed a debt to both.

Scholarship was one thing, personal survival in murderous times another. In the course of the year 950, it became clear that the Later Han emperor, Liu Chengyou, would not be able to retain his throne in the face of the rising power of Guo Wei 郭威, a Han Chinese general reportedly descended from Guo Ziyi's brother who was determined to free the Central Plains region from Liao encroachment. Guo Wei had served Shatuo rulers with distinction since the Later Jin, but now saw himself as more qualified to rule than the young Liu Chengyou, who unsuccessfully tried to have him murdered in 950. In 950, having indeed eliminated Liu Chengyou, Guo Wei proposed Liu Yun as successor and sent senior ministers, including Feng Dao, to persuade Liu to come to Bian. The ominous portents associated with Liu Yun accumulated. As Liu Yun set out to welcome Feng Dao at the outskirts of Xuzhou, his usual horse shied, forcing him to use a different horse, an incident that onlookers took as inauspicious. And as he left the city, the clouds parted and a band of sunlight lit up the city behind him like a painting, while thunder rumbled. This time the contemporary comment was that the heavens were splitting apart.Footnote 53 The invitation to become emperor was patently dangerous, and Liu Yun eventually accepted it with great hesitancy. On the way to Bian, he and his entourage, including Guo Zhongshu, accompanied by the senior ministers, stopped overnight at Shangqiu, and awoke to discover 700 cavalry led by Guo Chongwei 郭崇威 outside the yamen compound blocking their way forward. They quickly learned that Guo Wei had seized power. With Guo Zhongshu at their head, Liu's entourage turned on the ministers, whom they accused of having betrayed them:

When Zhongshu learned of the changed situation, he self-righteously remonstrated with [Feng] Dao: “Your excellency has been a senior minister under successive dynasties. Your honesty is famous throughout the world. When scholars everywhere speak of you, it is always with admiration for your conduct, which they uniformly consider exceptional. But now suddenly you baselessly propose to abandon the enterprise of Han and its predecessors. Does this leave your excellency easy in your heart?” Dao said nothing in reply. Zhongshu then argued to Liu Yun that he should kill Dao and flee to Hedong [northern Shanxi]. Liu Yun vacillated and could not bring himself to do it, then was overtaken by disaster. Zhongshu went into hiding for a long time.

忠恕知事變, 乃正色責道曰:”令公累朝大臣, 誠心著於天下, 四方談士無賢不肖, 皆以為長者。今一旦反作脫空, 漢前功業並棄, 令公之心安乎?” 道無言以對。忠恕因勸湘陰公殺道, 以奔河東。公猶豫未決, 遂及於禍。忠恕竄迹久之。Footnote 54

This account, from Wudai shi bu 五代史補, is corroborated by a broadly similar account in Jiu wudai shi that does not mention the name of Feng Dao's attacker.Footnote 55 In contrast to his later, Song dynasty reputation, in his own lifetime Feng Dao, the unwavering supporter of the Directorate of Education, was a much admired figure, exactly as Guo is reported to have described him.Footnote 56 Feng, as a sixty-nine-sui veteran of the administrations of three dynasties plus the Liao occupation, had faced down more formidable opponents than the twenty-three-sui Guo Zhongshu. Moreover, in this case Feng was unfairly accused, since he had in fact opposed an earlier attempt by Guo Wei to seize power and moreover had no prior knowledge of the events of the previous hours that had suddenly brought Guo Wei to the throne. From other accounts it seems that the man who had Liu Yun's ear during this critical time was Dong Yi 董裔, the manager of official paperwork (panguan 判官) on Liu Yun's staff.Footnote 57 It makes sense, therefore, that after Guo Zhongshu “clashed with the Record Keeper Dong Yi (despite the fact that the latter is said to have been giving similar advice to Liu Yun), he resigned and left” (與記事董裔争事, 拂衣而去).Footnote 58 This was fortunate for Guo, given that within hours Guo Chongwei executed Dong Yi and Liu Yun's other lieutenants.Footnote 59 No wonder Guo Zhongshu went into hiding and laid low for a long time. For, compounding the problem, his intemperate intervention subsequently took on a dangerous resonance from the fact that Liu Yun's biological father, Liu Min 劉旻, went on to establish a Shatuo Northern Han 北漢 kingdom (950–979) at Taiyuan during the same year. A troublesome irritation to both the Later Zhou and the Song, the kingdom survived until 979 as a client state of the Liao.

Bian, 952–953

In the first month of 951 Guo Wei established his own [Later] Zhou dynasty. He then executed Liu Yun and attacked his remaining followers in Xuzhou, eliminating them after a two-month siege.Footnote 60 Guo Zhongshu was fortunate: his proven talents as a paleographer were more useful to the Zhou government than would have been his elimination. The Directorate of Education was then under the directorship of Tian Min 田敏 (b. 880), a specialist of the Classic of History (Shang shu 尚書) with whom Guo, given his fascination for the same text, may have studied at some point. The Later Zhou Directorate recruited Guo Zhongshu, probably not before 952 given the dangerous situation he was in in 951, but probably not later either, to judge by what he achieved by the end of 953. The occasion of his recruitment was most likely an imperial order to “seek out sages” (zhao xian 召賢). “Seeking out sages” was a time-honored recruitment strategy for governments when the supply of degree holders was insufficient or when qualified candidates for official positions were reluctant for political reasons, and there were several such orders under the Later Zhou. Official appointments at that time followed Tang practice, commonly combining functional titles (guan 官), prestige titles (sanguan 散官), and merit titles (xun 勳). The combination fixed the official's status within a complex hierarchy, but his functional title determined the design and color of the robes he wore and the corresponding basic salary.Footnote 61 Guo Zhongshu's initial titular appointment was to the School for the Sons of the State, as Erudite with Responsibility for the Study of Calligraphy (Guozi shuxue boshi 國子書學博士).Footnote 62 He is the only known Erudite to have had this responsibility under any of the Five Dynasties (though he had a counterpart in the Later Shu kingdom), and he was not to have a successor in Bian until after Taizu's reign ended in 976.Footnote 63 Calligraphy and paleography both fell under the shuxue boshi rubric, defining his actual function within the Directorate of Education. His corresponding prestige title was Grand Master for Closing Court (Chaosan dafu 朝散大夫, rank 5b2 under the Tang dynasty) within the Court of the Imperial Clan (Zongzheng si 宗正寺), where his merit title was vice-director (cheng 丞).

Under the Later Zhou in the 950s, the Directorate of Education continued to operate as much or more as a center of publishing as it did as a teaching institution. Completing a longstanding institutional project, in 953 the complete set of the Nine Classics was finally printed and offered for sale. Like the Kaicheng Stone Classics before them, the Five Dynasties editions printed by the Directorate of Education employed a standardized regular script calligraphy, made possible by the use of a few particularly disciplined calligraphers. The calligrapher for most of the Nine Classics was Li E 李鶚, whose work for the project can still be seen today in facsimile due to a Muromachi-period reprint of a Southern Song Directorate of Education reprint of the 953 Erya edition (Figure 5).Footnote 64 By this time, the Directorate had also expanded its printing activities to include reference works beyond the Erya, the original lexicographic guide to the Classics. The additional reference works were useful to the Directorate's ongoing professionalization of the examination system, since they helped to create consensus over the identification of characters, the identification of tones, and the interpretation of meaning. The first of these ancillary texts to be published, also in 953, were new editions of Single-Graph and Compound Characters of the Five Classics (Wujing wenzi 五經文字), here shown in an eighteenth-century edition (Figure 6), and Compound-Character Graphs of the Nine Classics (Jiujing ziyang 九經字樣); the latter work had previously also been printed privately in 946.Footnote 65 It was almost certainly in order to work on these two books that Guo was recruited to the Directorate of Education, since he wrote in 953 that he had “recently been serving as an official paleographer, verifying and correcting the identification of compound characters in the Stone Classics” (臣頃以小學蒞官, 校勘正經石字).Footnote 66 For this work, the research leading up to his Origins of Compound Characters in the “Shuowen” (Shuowen ziyuan 說文字源) of 948 had prepared him perfectly.

Figure 5 Muromachi-period facsimile reprint of a Southern Song Directorate of Education facsimile reprint of the 953 Later Zhou Directorate of Education printing of Guo Pu's Erya, transcribed by Li E (detail). Guyi congshu (Tokyo: Chinese Embassy, 1884) facsimile reprint. (color online)

Figure 6 Zhang Can, Single-Graph and Compound Characters of the Five Classics (Wujing wenzi 五經文字). Yangzhou: Qimen Ma shi Congshulou, Qianlong period, based on a rubbing of the engraved edition appended to the Kaicheng Stone Classics. (color online) Downloaded from GMZM.org. http://www.gmzm.org/?gujitushu/wujingwenzi.html.

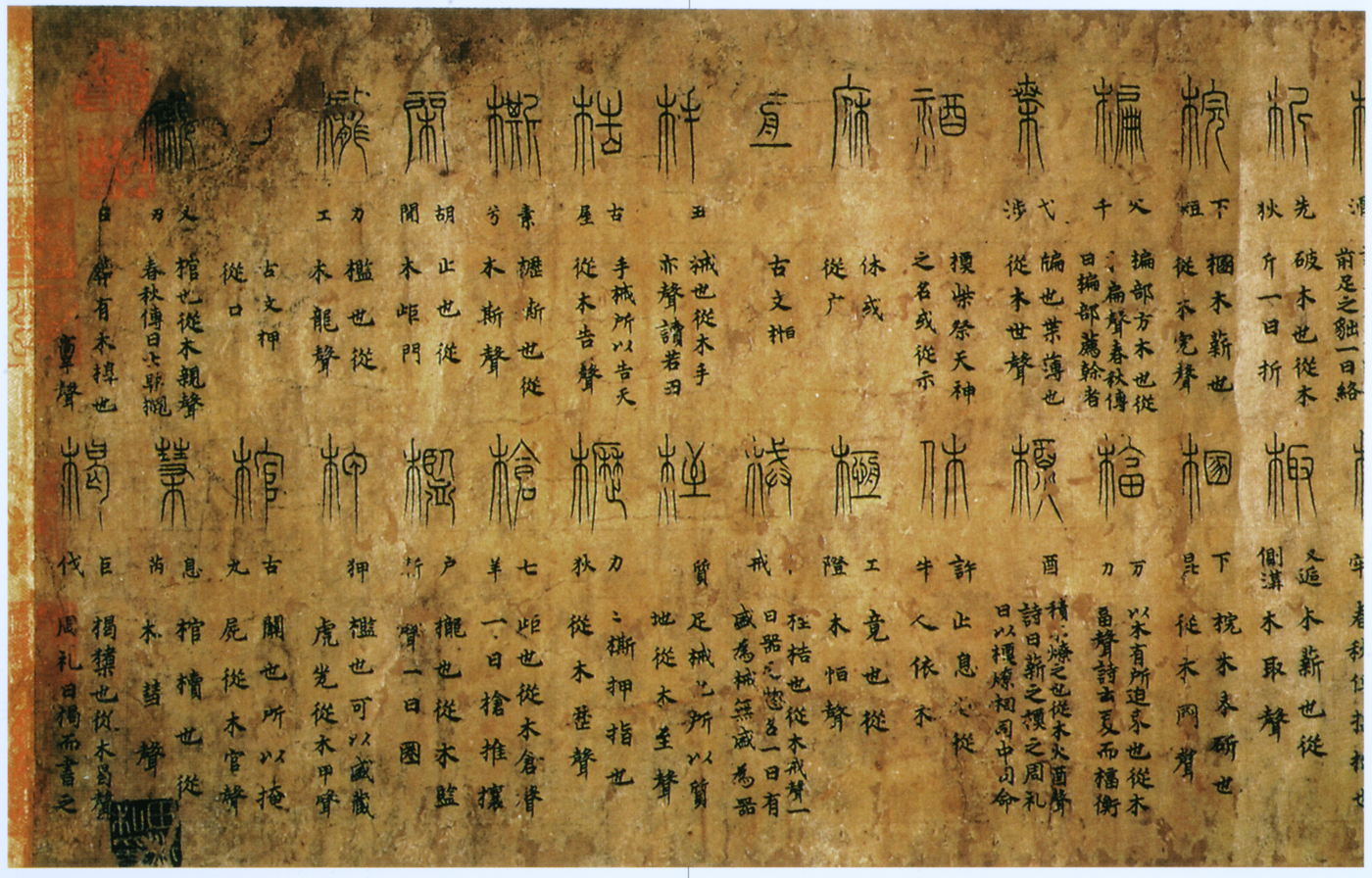

Guo Zhongshu made the paleographic principles of his editorial work at the Directorate of Education available through a second book of his own entitled Bamboo Slip Writing (Han jian 汗簡), which he completed and submitted before the end of 953; Figure 7 illustrates an eighteenth-century edition (Figure 7).Footnote 67 Bamboo Slip Writing takes the basic organization of his earlier Origins of Compound Characters derived from Lin Han as the basis for a much more ambitious reference work than either Lin or he had been able to produce. Whereas the earlier works had used seal script for the entry headings, Bamboo Slip Writing uses ancient script itself. The bulk of the book is a “Tabulation” 目錄 in which related compound characters are listed under each heading in ancient script but are identified in regular script. To establish the orthography of the ancient script characters, Guo drew on seventy-one sources, which are noted at each use. Guo explained at the beginning of the book:

In bamboo slip manuscripts [see Figure 3] the different compound characters corresponding to each single-graph radical (zimu 字母) are so numerous that they cannot all be recorded here. Moreover, they are published elsewhere. For ease of consultation, therefore, I have only made separate records for the radicals, and for all the other compound characters [related to each radical], I have used regular script [to identify them] in a note underneath.

Figure 7 Guo Zhongshu, Bamboo Slip Writing (Han jian 汗簡), Sibu congkan xubian, 70, juanxia 2.81a. (color online) Downloaded from Wikisource.

汗簡字母篆文繁多, 不能備載, 且世有刋本, 故僅錄字母, 其餘諸字, 悉以楷書列註其下, 以便檢閱).

I take this to mean that identifying the ancient-script equivalents for all the small-seal script compound characters in Li Yangbing's edition of Discussion of Single-Graph Characters and Explanation of Compound Characters would have been too big a job. Clearly, Guo intended his book to be used in conjunction with Discussion, in which the reader could find the seal script (though not ancient script) version of any given compound character. This also allowed Guo to eschew any philological explanation of the characters’ meanings, since this too could be found in Discussion.

Guo Zhongshu prefaced his book with a short explanation in which he argued for the importance of studying ancient script directly:

Bamboo slip writing, which transmits the image of antiquity, is the progenitor of later [forms of writing]. It started from Cang Jie and stopped with Shi Zhou. We thus follow the Stone Drum inscriptions, from which one can get some idea of it. But there are many errors of transcription, and it is impossible to understand the text completely. Your humble subject recently served as an official paleographer, verifying and correcting the identification of compound characters in the Stone Classics. This involved consulting a vast range of sources and drawing on existing dictionaries; whenever I gathered useful information, I immediately wrote it up in scroll form. [In this dictionary] I have prioritized first the Classic of History, then the Stone Classics and Discussion of Single-Graph Characters and Explanation of Compound Characters, and have supplemented these with information patched together by later writers. Following Mr. Xu's example [in Discussion], I have divided the characters according to category, so that they will not get mixed up with each other and for ease of consultation. I have also noted the source for each character, so that [the contributions of different sources] can be distinguished. In addition, beneath each compound character, I have explained the design of the character without translating it into clerical-script form, to aid the reader's understanding. All characters that are the same as in modern script have been excluded, because it would add nothing to the phonological or paleographic literature. Are also omitted: redundant forms, characters that are difficult to transcribe with the brush, and anything beyond my knowledge.

汗簡者, 古之遺象, 後代之宗師也。蒼頡而下, 史籀已還。爰從漁獵, 得其一二。傳寫多誤, 不能盡通。臣頃以小學蒞官, 校勘正經石字。繇是諮詢鴻碩, 假借字書, 時或採掇, 俄成卷軸。乃以《尚書》為始, 《石經》《說文》次之, 後人綴緝者殿末焉, 遂依許氏, 各分部類, 不相間雜, 易於檢討, 遂題出處, 用以甄别。仍於本字下, 直作字樣之釋, 不為隸古, 取其便識。與今文正同者, 惟目錄之外, 不復廣收。《切韻》、《玉篇》, 相承紕繆。體既煩冗, 難繕牋毫, 有所不知, 盡闕如也.

The book ends with an appendix, “Brief Comments on the Tabulation” (Luexu mulu 略叙目錄), that gathers together earlier discussions of the script down to the late Tang dynasty.

As Zheng Sixiao 鄭思肖 (1239/41–1316/18) perceptively inferred, Guo wrote Bamboo Slip Writing to defend the chronological precedence of the characters in the ancient-script versions of the Classic of History over those in the “modern-script” version. The latter version had been orally transmitted by the scholar Fu Sheng 伏生 (active late third-early second century BCE), and written down using the clerical-script characters in use at the beginning of the Han dynasty (Figure 8). But there had also been several ancient-script versions, of which one championed by the fourth-century scholar Mei Ze 梅賾 survived; however, that version was a scholarly reconstruction “reverse-engineered” from the clerical-script version. Both the clerical-script and ancient-script versions were considered authoritative, but scholars differed as to which represented the earlier version of the Classic. This was an important paleographic issue, because Xu Shen had cited characters from both ancient-script and clerical-script versions in Discussion of Single-Graph Characters and Explanation of Compound Characters. Footnote 68 Guo stated his own position bluntly at the end of his appendix:

“Bird-tracks” and “tadpoles” are both names for ancient script. As customs changed, the script came to be used less and less, until any basis for knowledgeable discussion was lost and it was known only from hearsay. The Grand Preceptor said: “When the [forms of the] rites are lost, search for them in the countryside.” Might not ancient script be even better than the countryside? This is your humble subject's purpose. Although only in small fragments, [ancient script] has not disappeared from the world, so I have given an account here [of people's continued awareness of it], by collecting references to [ancient script] and presenting them in chronological sequence.

鳥跡, 科斗通謂古文。歷代從俗, 斯文患寡, 目論臆斷, 可得而聞。太史公曰:”禮失求諸野。”古文不愈於野乎?亦下臣之志也。塵露雖㣲, 山海不却, 畧叙其事, 集而次之。

In Mei Ze's ancient-script version of the Book of History, the characters included a combination of ancient-script graphs that were current during the Warring States period and ancient-script graphs that came into circulation at a later date. In Guo Zhongshu's time, no-one had yet misinterpreted the inclusion of the latter anachronistic graphs as evidence of deliberate forgery. On the contrary, Guo seems to have recognized that the Mei Ze ancient-script version was an imperfect reconstruction. So what he was really defending was the chronological precedence of an ideal ancient-script version that remained to be properly reconstructed. His confidence in the correctness of this view was based on the 71 sources cited in his notes to the entries.Footnote 69

Figure 8 On Judging Good-Quality Swords and Knives (Xiang li shan jiandao 相利善劍刀), wooden-slip manuscript written in bafen clerical script, early first century CE. Excavated from the ancient site of Jianshuijin Guan in Jinta County in Juyan, Gansu. Collection of Gansu Provincial Cultural Relics Research Institute. Zhongguo fashu quanji, 1, Xian-Qin Qin-Han, Song Zhenhao editor-in-chief (Beijing: Wenwu, 2009), 237. (color online)

While Bamboo Slip Writing did not have a wide circulation under the Song dynasty, it did have notable admirers. At the end of Taizu's reign the noted calligrapher Li Jianzhong 李建中 (945–1013) found an unattributed manuscript copy. A Hanlin Academician, the formerly Southern Tang calligrapher Xu Xuan 徐鉉 (916–991), brother and scholarly collaborator of the paleographer, Xu Kai 徐鍇 (920–974), identified for Li its authorship. Li Jianzhong then made his own manuscript transcription of Bamboo Slip Writing, which he submitted to Song Taizong in 976 in a successful attempt to get himself noticed as a calligrapher.Footnote 70 Later, the paleographer Xia Song 夏竦 (985–1051) used Bamboo Slip Writing as the basis for a new dictionary, Pronunciations and Tones of Ancient Script (Guwen sisheng yun 古文四聲韻), in which he replaced Guo's ancient script transcriptions of the radicals with transcriptions in clerical script. Other admirers included Ouyang Xiu 歐陽修 (1007–1072), the antiquarian Lü Dalin 呂大臨 (1046–1092), the poet Su Shi 蘇軾 (1037–1101),Footnote 71 and the philosopher Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130–1200).Footnote 72 As late as the end of the eighteenth century, the compilers of the Siku quanshu, themselves deeply involved in archaeological scholarship, were similarly impressed. In their view, Bamboo Slip Writing was the basis for all paleological study of ancient script following it.Footnote 73 In the course of the nineteenth century, however, Bamboo Slip Writing gradually came to be marginalized as Qing philologists focused their attention on inscriptions on excavated Shang and Zhou bronze vessels, which employed an even more archaic form of script. Moreover, Guo Zhongshu's own Warring States archaeological evidence was doubted. One prominent eighteenth-century figure, Bi Yuan 畢沅 (1730–1797), had gone so far as to accuse Guo Zhongshu of having fabricated characters. By the end of the nineteenth century, Bamboo Slip Writing was considered by many to be completely untrustworthy, while others attributed its unfamiliar elements to the currency of late versions of ancient script in the centuries immediately preceding Guo's book. The latter characterization was not entirely wrong—Guo did not always get the reconstruction right—but there was a tendency to overestimate vastly the number of anachronistic characters he included. The reputation of Bamboo Slip Writing has recovered, however, with the arrival of scientific archaeology, as more and more of the very forms that puzzled later writers have turned up on excavated bamboo slips. It is now recognized that although Bamboo Slip Writing is not devoid of ancient script characters whose forms were invented by post-Han writers, it is basically an accurate reflection of the script in use in the Warring States period. Correspondingly, in recent decades Bamboo Slip Writing has proved to be an invaluable reference work for scholars involved in deciphering the vast numbers of bamboo slips that have been recovered from Warring States tombs in central and south-central China.Footnote 74 Guo Zhongshu's scholarly reputation has soared in consequence. Since the year 2000, his paleology has become the object of many articles, dissertations, and books in China.Footnote 75

Ruzhou, 954

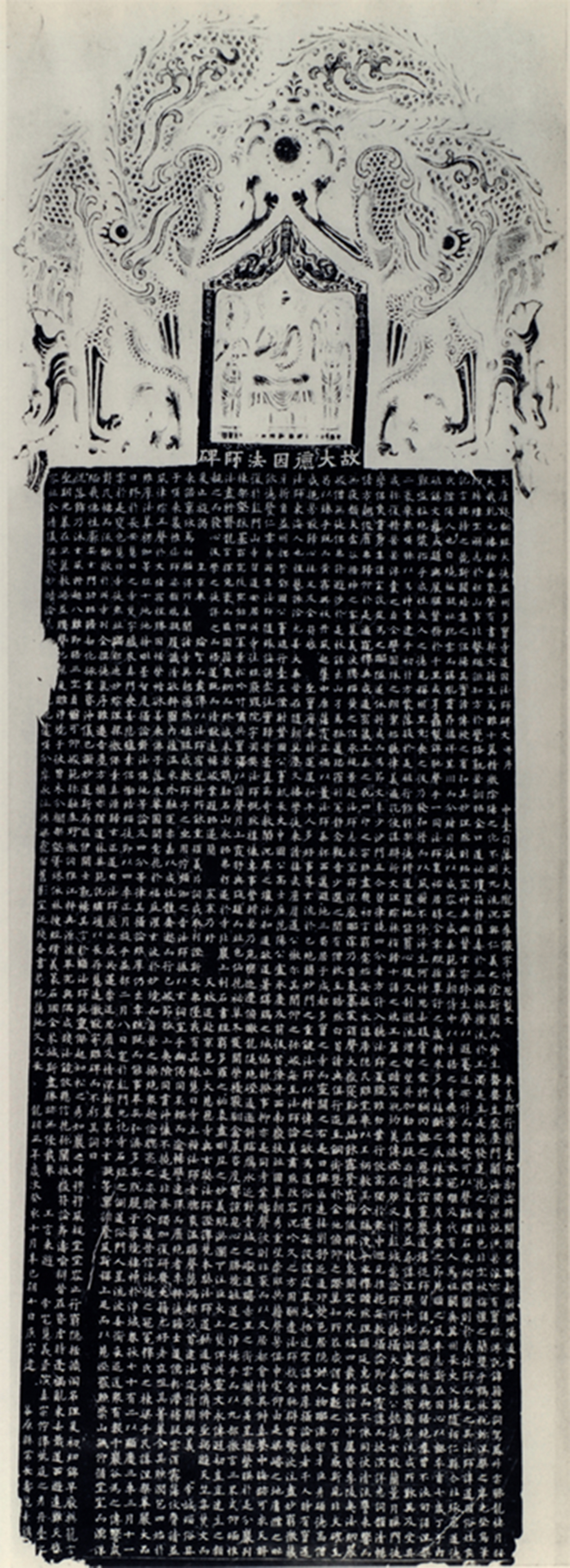

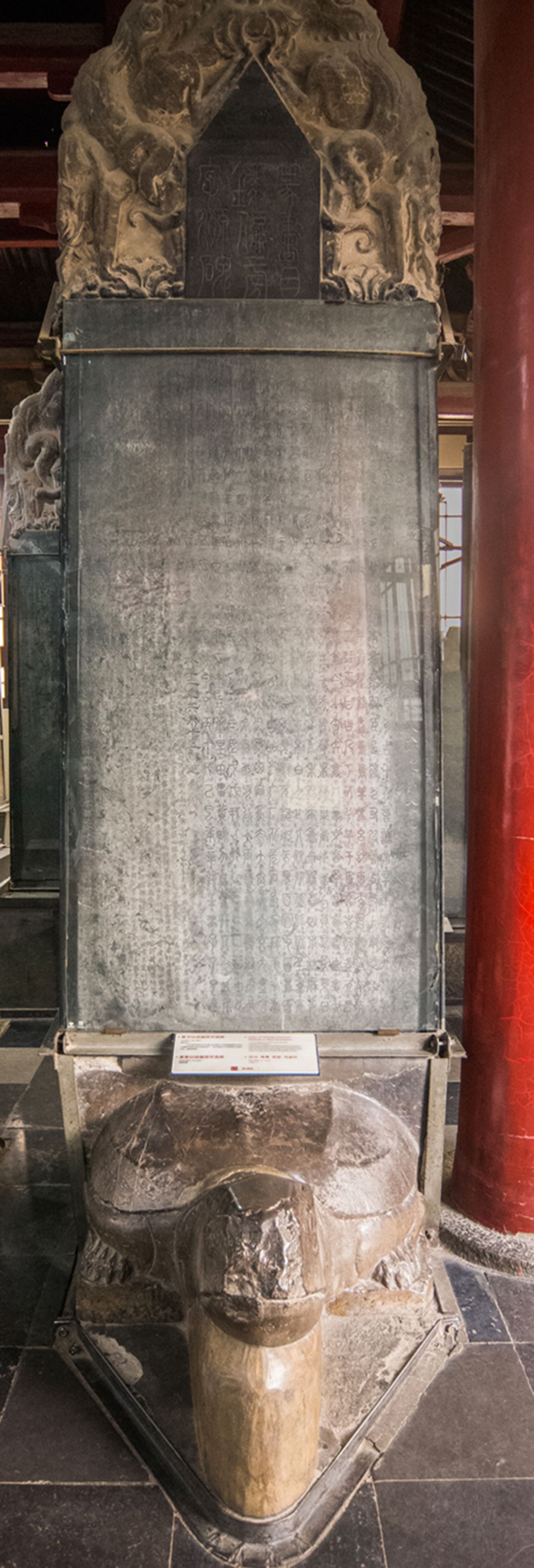

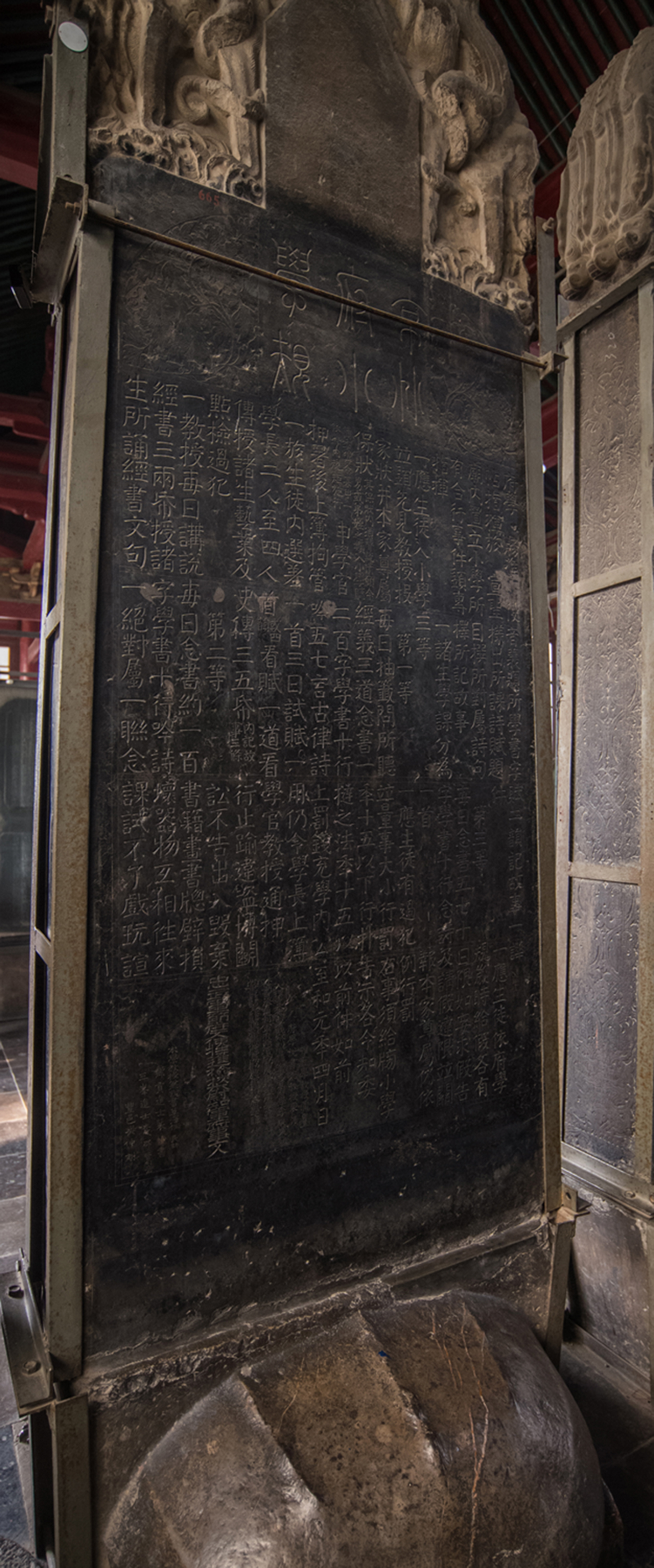

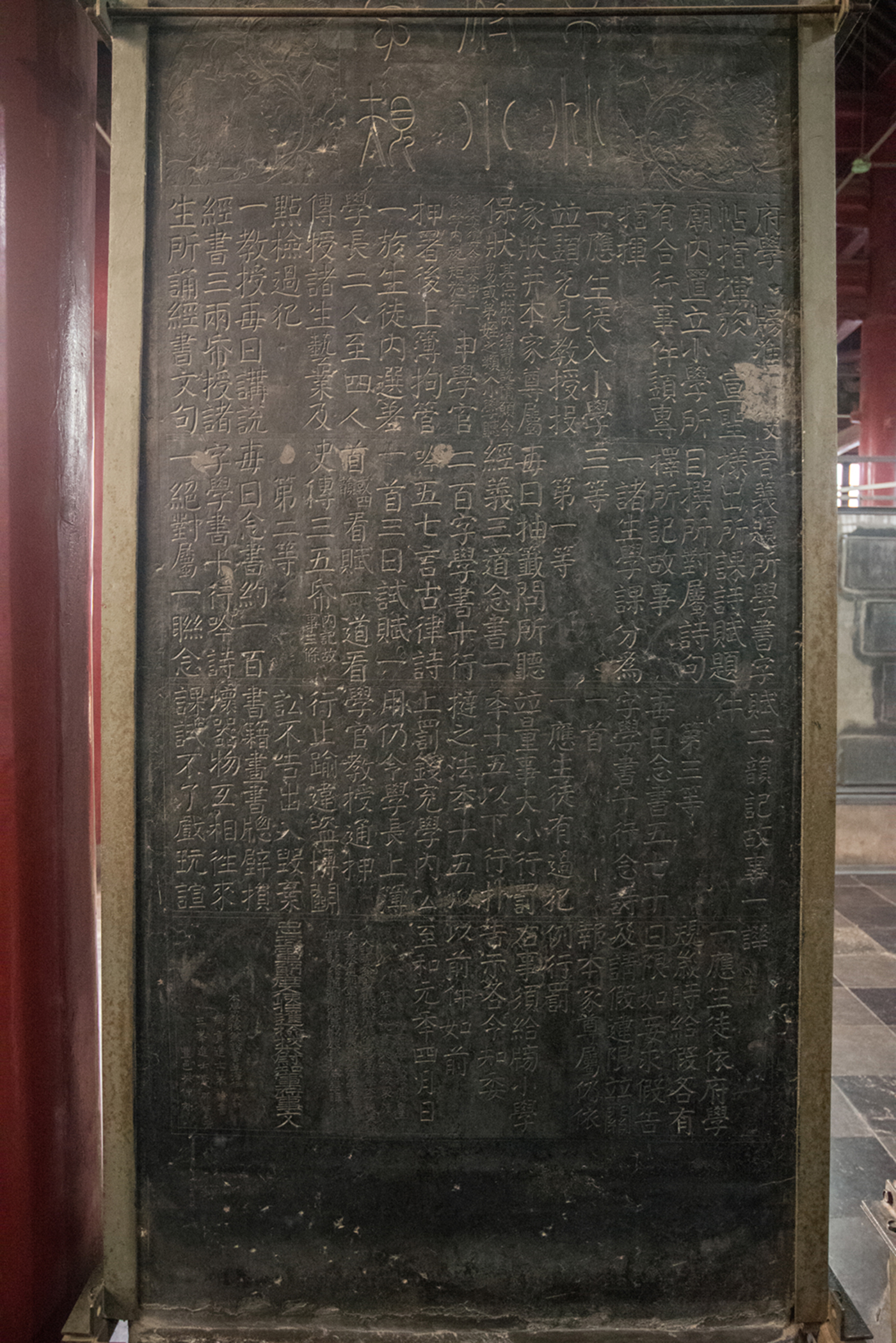

Guo Wei died suddenly at the beginning of 954. After the accession of his nephew-in-law Chai Rong 柴榮 as Shizong 世宗 (r. 954–959), Guo Zhongshu's Directorate of Education position lapsed. He was reassigned to serve as District Magistrate (xianling 縣令) in an unidentified county of Ruzhou in southern Henan, to the south of Luoyang, located “within a bend of the Ru river to the west of Mt. Song” (在汝水之汭, 嵩山之陽).Footnote 76 Although it might at first seem odd that Guo should have switched to the field administration, one of the policies of the Later Zhou emperors (later continued by the early Song rulers) was to strengthen central government control over local administration by appointing civil officials from the center.Footnote 77 It was as District Magistrate that on the fifteenth day of the fourth month of 954, he signed a stele inscription, Record of the Temple to the Exalted King of Culture (Confucius) (Wenxuan wang miao ji 文宣王廟記), which he had composed as well as transcribed (see Figure 13). Guo chose the less easily readable small-seal script (rather than bafen 八分 clerical or xiaokai) for the transcription, as if he wanted to use writing to displace the reader back into the pre-Han past. Confucius Temples (variously called Wenxuan wang miao 文宣王廟, Wen miao 文廟, Kongzi miaotang 孔子廟堂, or Kong miao 孔廟,) were state institutions, often associated with a prefectural or county school. This was the second stele inscription that Guo Zhongshu contributed to the network of Confucian institutions in north-central China, following his Shuowen ziyuan stele in Xuzhou. The text of the 954 stele inscription, Record of the Temple to the Exalted King of Culture, carried its own heavy political meaning. Two years earlier, Guo Wei had visited Qufu in Shandong. When challenged about the propriety of the Son of Heaven paying homage to a mere mortal, Guo Wei replied: “Confucius has been the teacher of rulers for a hundred generations—how could I not venerate him?” (文宣王, 百代帝王師也, 得無敬乎).Footnote 78 With this, he signaled that Confucian ideology would be central to the Later Zhou enterprise in a way that had not been the case for the Later Han, Later Jin, Later Tang, or Later Liang.

Bian, 955–959

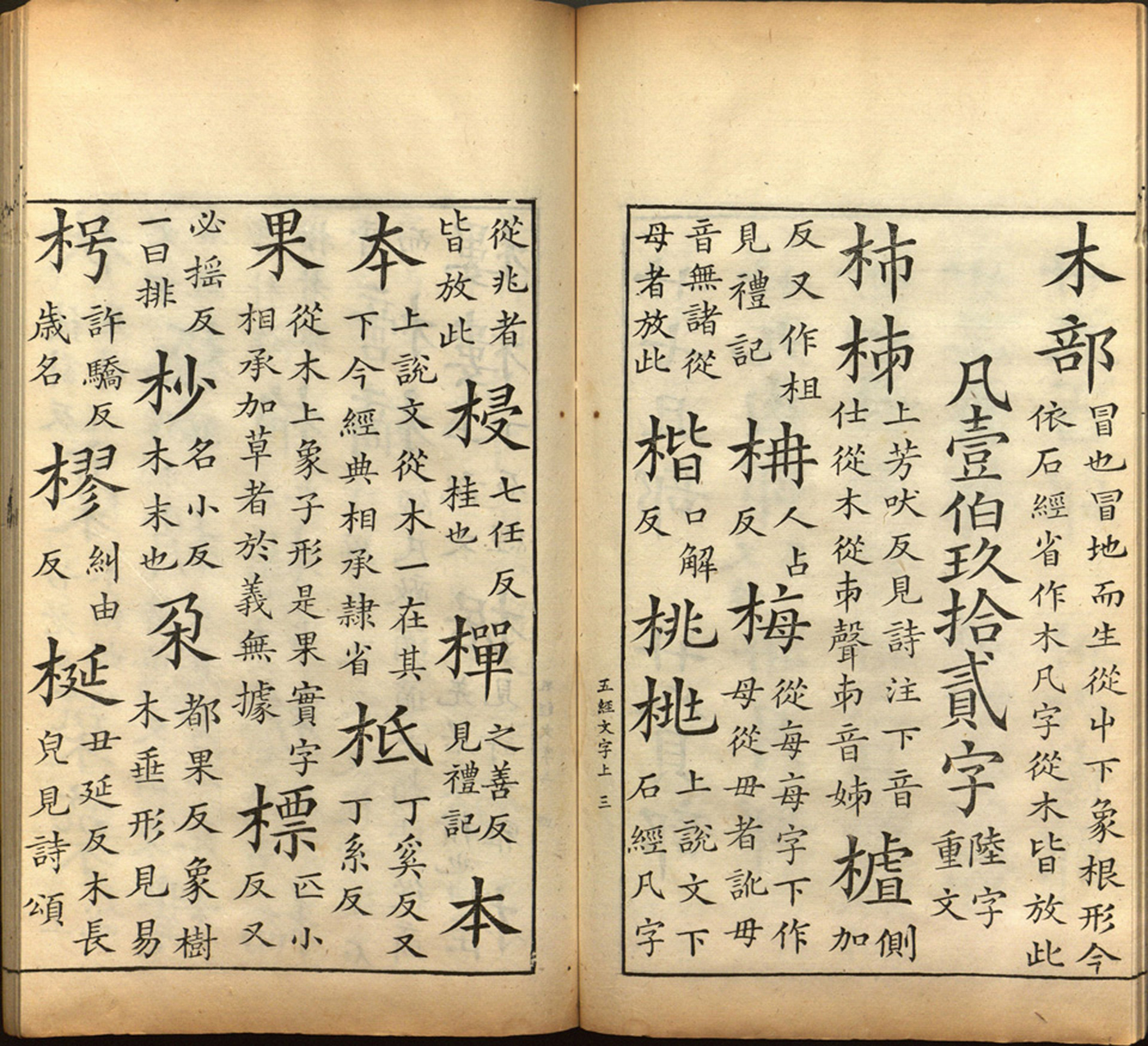

Guo did not stay long in Ruzhou. Shizong's administration quickly brought him back to the School for the Sons of the State. In 955, the Directorate of Education in Bian was relocated to a monastery (Tianfu puli chanyuan 天福普利禪院). During this period, from perhaps as early as 955 until the end of the dynasty in 959, Guo worked on two scholarly books. The first to be completed was another dictionary, Bodkin (Peixi 佩觿), illustrated in a Kangxi edition in Figure 9, its title as much a reference to the intricacy of paleographic and philological work as to the book's function as a tool. Bodkin, which circulated as a manuscript that gained a printed version in the Qing dynasty, was another outgrowth of Guo's work on the Directorate's reference publications. At the head of the text, Guo Zhongshu identifies himself as Erudite of the Five Classics Specializing in the Book of Changes (Guozi Zhou Yi boshi 國子周易博士), holding the prestige title Grand Master for Court Audiences (Chaoqing dafu 朝請大夫, 5b1 under the Tang), representing a slight promotion within the Court of the Imperial Clan from his Later Han position as Grand Master for Closing Court. His merit title was similarly a promotion, in this case a notable one, to Pillar of the State (zhuguo 柱國).Footnote 79 Given his ongoing paleographic work during this period, the shift in his responsibilities as Erudite from shuxue (paleography and calligraphy) to the Zhouyi (i.e., the Yijing) probably means that he was adding rather than changing responsibilities. A plausible explanation is that Guo Zhongshu had been assigned to the team of scholars that started work in 955 on a new edition of Lu Deming's Textual Explanations of Classics and Canons (Jingdian shiwen, Figure 10), mentioned earlier as Kehong's model for Compendium of Sounds and Meanings in the Tripitaka.Footnote 80

Figure 9 Guo Zhongshu, Bodkin (Peixi), Qinding siku quanshu, juanxia, 1a. Downloaded from Guoxuedashi.com. (color online)

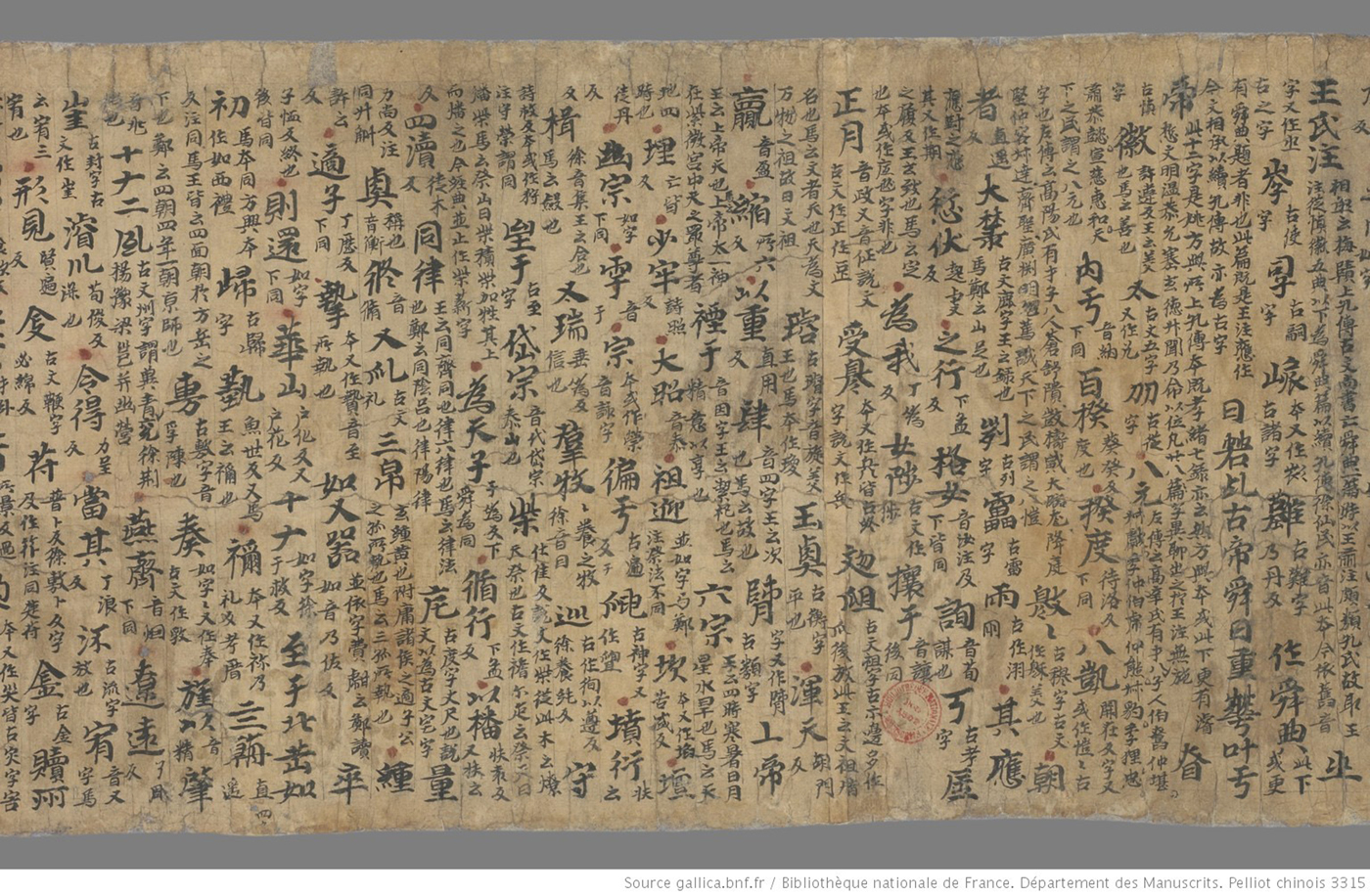

Figure 10 Lu Deming, “Textual Explanations of the Book Of History” (Shangshu shiwen 尚書釋文), from Textual Explanations of Classics and Canons (Jingdian shiwen), fragmentary ink-on-paper manuscript from Dunhuang Mogao Cave 17, late Tang dynasty. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Pelliot chinois 3315. Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France. (color online)

Like the other Tang dynasty dictionaries on which Guo had worked, Textual Explanations attempted to remove some of the confusion caused by inconsistent transcriptions when the Classics were originally written down, reflecting the fact that at the point when ancient script was current the Chinese written language had not yet stabilized. The various dictionaries also addressed the further confusion created by historical distance, since the more (but not completely) standardized regular script of the Tang, like the clerical script from which it had developed, in itself often contradicted the use of the equivalent characters during the Warring States period. In the course of his work, Guo came to realize that all this inconsistency and confusion was susceptible to morphogenetic analysis of the visual forms of characters and the association with pronunciation. The bulk of Bodkin (scrolls two and three of the three-scroll work) comprises a compendium of pairs of compound characters with similar shapes or sounds written in regular script, where the second character is the one that can be used to establish the shared meaning (Figure 9). For each pair of characters, Guo specifies the specific process responsible for the first character's association with the second character's meaning, which takes him back into ancient script. Preceding the dictionary proper, however, is a one-scroll treatise on paleography and linguistics establishing the rationale of the dictionary; although the treatise has obvious philological implications, Guo leaves these to others to explore. Instead, Guo lays out discursively the patterns of inconsistency that he has identified, and provides detailed reasons for why they occurred, identifying basic historical processes that led to confusion, and further breaking down each of these processes into more specific processes. In just a short space, therefore, Guo pithily sketches out the landscape of the morphogenetic development of the written Chinese language, from Warring States ancient script to modern regular script—the first person to do so.Footnote 81 Like Bamboo Slip Writing, Bodkin had a limited circulation under the Song, but it was much appreciated by those who had access to it, including the statesman and paleographer, Song Xiang 宋庠 (996–1066), who considered his own annotated edition of Guo's text to be one of his treasures.Footnote 82

Guo's second and in political terms more consequential project of the later 950s was nothing less than a Revised Ancient-Script [Edition of the] Classic of History with Explanations of Characters (Ding guwen shang shu bing shiwen 定古文尚書并釋文). Guo aimed to replace the Mei Ze ancient-script reconstruction with a more accurate reconstruction of his own. Revised Ancient-Script [Edition of the] Classic of History with Explanations of Characters fitted better than his earlier books (Origins of Compound Characters in the “Shuowen”, Bamboo Slip Writing, and Bodkin) into the Directorate's program of printed publications stretching across three decades and three dynasties, and Guo apparently prepared a woodblock-printed edition. For this we have the testimony of the late Southern Song scholar, Wang Yinglin 王應麟 (1223–1296), who notes a 959 version in “carved woodblocks [for printing]” (keban 刻板).Footnote 83 Wang's mention may indicate that Revised Ancient-Script [Edition of the] Classic of History with Explanations of Characters was actually part of the Directorate's new edition of Textual Explanations of Classics and Canons published that year.Footnote 84 This hypothesis seems more likely than the alternative: that Guo's ancient-script edition of the Classic of History was a separate, stand-alone book printed by the Directorate. Among the manuscripts recovered from the Dunhuang library cave is a fragmentary late Tang manuscript preserving part of the Classic of History section of Lu Deming's multi-volume dictionary (Figure 10).Footnote 85 It shows that Guo is likely to have compiled the book with the text in ancient script for the main text and xiaokai regular script for the notes and commentary. Chao Gongwu 晁公武 (1105–1180) mentions that Guo's now-lost text was later engraved in stone, which leaves open the possibility that a rubbing from this stele edition may some day surface.Footnote 86 In 959, Shizong gave every sign of being able to reunify China under the Later Zhou. The partial success of his campaigns against the Southern Tang the previous year had forced its ruler Li Jing (r. 943–961) to declare nominal allegiance to the Later Zhou. In 959, there was no thought of a Song dynasty. Guo Zhongshu must have known that his edition of the Classic of History had the potential to influence general understanding of one of the canonical Five Classics. The scholarly stakes, for him, were enormous.

Guo Zhongshu's four major books (some other short works, now lost, are recorded) were produced within the short span of ten years, and followed a logical progression.Footnote 87 Guo began with a study of Discussion of Single-Graph Characters and Explanation of Compound Characters (Origins of Compound Characters in the “Shuowen”), then produced his own alternative dictionary of ancient script characters (Bamboo Slip Writing), and continued with an innovative study of the historical development of writing (Bodkin). Finally, Guo applied his broad knowledge of ancient script to establishing a more reliable ancient-script edition of the Classic of History (Revised Ancient-Script [Edition of the] Classic of History with Explanations of Characters). In 959 Guo, at the age of 32 sui, was a scholar and calligrapher of high reputation who aspired to change the course of Confucian scholarship through his paleographic and linguistic work.

Guo Zhongshu's Early Calligraphy

Guo's years in Luoyang and Bian under the Zhou—the 950s—overlapped with the final years of one of the great modern practitioners of running and draft scripts, Yang Ningshi 楊凝式 (873–954), from Huayin 華陰, just west of the bend of the Yellow River on the way from Luoyang to Chang'an. A follower of the great regular-script calligrapher Yan Zhenqing 顏真卿 (709–785), Yang's radical innovation was to introduce elements of running and draft script into regular script (Figures 11, 12). Here, as in so many other areas of culture and social life in the tenth century, modern practice entailed the breaking down of categorical divisions through attention to the transitions between formerly compartmentalized categories.Footnote 88 Under the Later Tang, as Mingzong built up the state library, Yang Ningshi was a Directorate of Education librarian and editor in Luoyang, but in the years before his death in 954 he became an eminent administrative official in the Zhou government, a Junior Preceptor (shaoshi 少師), posted to Luoyang as the Regent in charge of the Western Capital (Xijing liushou 西京留守). Few works by Yang Ningshi survive today, even though his work was much in demand at the time. Tao Gu relates the following story:

The calligraphy and painting of the Junior Preceptor, Yang Ningshi, was preeminent in its time. The scrolls of paper left by those who sought calligraphy from him were piled high like a smooth [white] wall. The Junior Preceptor gave a great sigh, and said: “What am I to do with so many ‘creditors’—they're really like armed bullies! When I was a boy, I found strange [the story of] Yan Liben warning his younger relatives not to study painting; now that I am old, I start to realize that talent really can be a burden.”

少師楊凝式, 書畫獨步一時。求字者紙軸堆疊若坦壁。少師見則浩歎曰:“無奈許多債主, 真尺二寃家也。少時怪閻立本戒子弟勿習丹青, 年長以來始覺以能為累” 。Footnote 89

One of Yang's preferred practices was to write on the interior walls of temples, often next to or on the surface of significant mural paintings. His inscriptions of this kind were, in effect, colophons, but of a kind that, like the wall paintings, had a certain built-in ephemerality. Many of Yang's inscriptions could be seen in the temples of Later Zhou and early Song Luoyang, where they were much imitated, most famously by the man who would later submit a copy of Guo Zhongshu's Bamboo Slip Writing to Taizong, Li Jianzhong. (Later, in Chang'an, the Buddhist monk-paleographer Mengying would follow Yang's example, leaving inscriptions on the interior walls of temples all over the city.) Only a few of Yang Ningshi's inscriptions, however, were ever engraved in stone to circulate as rubbings later.Footnote 90

Figure 11 Yang Ningshi (873–954), On the Daily Life of Transcendents (Shenxian qiju fatie 神仙起居法帖). Autograph manuscript on paper, 27 x 21.2 cm., Palace Museum, Beijing. Jin Weinuo and Xing Zhenling, eds., Zhongguo meishu quanji, 20, Shufa 2 (Hefei: Huangshan shushe, 2010), 401. (color online)

Figure 12 Yang Ningshi (873–954), Colophon to “Ten Episodes at Lu Hong's Thatched Cottage” (“Lu Hong caotang shizhi tu” ba 《盧鴻草堂十志圖》跋). Ink on paper, National Palace Museum, Taipei. Jin Weinuo and Xing Zhenling, eds., Zhongguo meishu quanji, 20, Shufa 2 (Hefei: Huangshan shushe, 2010), 403. (color online)

Yang's fame in mid-century Luoyang left Guo Zhongshu unmoved. Guo held running script and draft script in low esteem; by temperament and principle he preferred the disciplined order of regular script (particularly small regular script, or xiaokai), bafen clerical script, seal script, and ancient script. Although Guo Zhongshu's xiaokai calligraphy has not survived, we have Ouyang Xiu's enthusiastic testimony that it was outstanding. Here, Ouyang Xiu comments on the rubbing he had acquired of Guo's 950 Origins of Compound Characters in the “Shuowen” stele in Xuzhou:

The item to the right is the Origins of Compound Characters in the “Shuowen,” written in the hand of Guo Zhongshu who served in the imperial court and whose career is documented in the Veritable Records. He was a particularly eccentric character. Today people know him only for his calligraphy in small seal script and are ignorant of his skill in regular script, which is equally exquisite. However, [examples of] his regular-script characters carved in stone are not [usually] to be seen; that this work is the only surviving example is indeed a great shame. Amid the violence and disorder of the Five Dynasties, schools and academies fell into ruin and the way of scholarly gentleman slid deep into decline. Yet, even in such dire circumstances as these, there were men of Guo Zhongshu's calibre. Today our great state has ruled for a hundred years, peace reigns under heaven and Confucian learning flourishes once more, yet in the art of calligraphy alone has there been no comparable renaissance, so much so that the art itself stands on the brink of dying out. So if one were to seek the likes of Zhongshu's small character regular script today it simply could not be done. When I have occasion to speak with Junmo (Cai Xiang 蔡襄, 1012–1067) on the subject, this matter gives us no small cause for lament. The stele itself is to be found in Xuzhou.Footnote 91

右小字說文字源。郭忠恕書。忠恕者。集本有「五代漢周之際為湘陰公從事」十二字。及事皇朝。其事見實錄。頗奇怪。世人但知其小篆。而不知其楷法尤精。然其楷字亦不見刻石者。蓋惟有此耳。故尤可惜也。五代干戈之際。學校廢。是謂集本作為。君子道消之時。然猶有如忠恕者。國家為國百年。天下無事。儒學盛矣。 獨於字書忽廢。幾於中絕。今求如忠恕小楷。不可得也。故余每與君謨歎息於此也。石在徐州。集本無此四字。嘉祐八年十二月廿日書。

In contrast to this high assessment of Guo's early xiaokai regular script, Zhao Mingcheng considered the bafen clerical script of Guo's 949 Stele Commemorating the Renovation of the Ancestral Temple of Emperor Gaozu of the Han Dynasty, a rubbing of which he owned, to be weak in comparison to Guo's later bafen work. Be that as it may, in Bodkin, Guo left one of the most interesting discussions of the origin of the term bafen:

In the common understanding there are two theories on bafen. Some say that bafen (the eight distinctions) is the method of seal-script, while erfen (the two distinctions) is that of lishu clerical script. Others maintain that its characters all resemble the character “eight” (ba 八), with a configuration like waves coming to rest. Your subject (chen 臣) believes that neither theory is correct. Today it can be explained as follows: the Han dynasty scholar, Cai Yong, thought that clerical script was made up of eight distinct (fen 分) form-types, and that it was only after all these eight form-types evolved that this craft came into existence, which he called bafen, or “the eight distinctions. This is closer to the truth”.Footnote 92

八分之說, 流俗有二。或曰八分篆法, 二分隸文。又云, 皆似八字, 勢有偃波。臣以為二說皆非也。今按, 書有八體, 漢蔡邕以隸作八分體, 盖八體之後又生此法, 謂之八分, 近矣。

Today we can see from this period only Guo Zhongshu's seal script, represented by a single work, the 954 Record of the Temple to King Wenxuan (Confucius), a fragment of which survives in the form of rubbings (Figure 13).Footnote 93 Seal script had a widespread presence in mid-tenth century Luoyang and Bian. In the early 950s, for example, the eminent minister, He Ning 和凝, transcribed in seal script his own collected works, all one hundred juan of them, and had them privately woodblock-printed.Footnote 94 Surviving examples of Later Zhou seal script include the title inscription of a Later Zhou stele (Figure 14). But Guo had little time for recent seal script (see below). His own model was Li Yangbing (Figure 15), whose approach to seal script derived in part from that of Li Si 李斯 (third century BCE). Li Yangbing's approach generates an immediately recognizable architectonics, which conveys an austere and profound decorum. In Li's own words:

From heaven, earth, and mountainscapes I apprehend the script's square and round shapes; from the sun, moon, and astral formations I apprehend the complementarity of its organizing principles; from caps, robes, and insignia of rank I apprehend its deferential and ceremonious appearance; from eyebrows, mouths, and noses I apprehend its distinctions of pleasure and anger or sorrow and ease; from fish, birds, and beasts I apprehend its rules for extension, diminution, and propulsion; and from horns and teeth I apprehend its wavering and chewing motions. The hand thus gives rise to a myriad of transformations, as the mind creates what it will. The script fully manifests all the moods and images of Heaven, earth, and man, and it describes the appearance of the ten thousand things.

于天地山川, 得方圆流峙之形;于日月星辰, 得经纬昭回之度;于云霞草木, 得霏布滋蔓之容;于衣冠文物, 得揖让周旋之礼;于鬓眉口鼻, 得喜怒, 惨舒之分;于虫鱼禽兽, 得屈伸飞动之理;于骨角齿牙, 得摆拉咀嚼之势。随手万变, 任心所成, 可谓通三才之气象, 备万物之情状者矣。Footnote 95

Given his paleographic interests, Guo Zhongshu's calligraphic engagement with Li Yangbing's seal script was understandable. Still, Guo was aware of being out of step with his times—not only because of his predilection for this particular script, but because of his archaeological approach. In a later letter, “Reply to Mengying,” he writes:

Since the Southern Dynasties ended, few [calligraphers] have mastered the zhuan (small-seal) and zhou 籀 (large-seal) scripts. Only on steles, epitaphs, and seals do people today use a few characters. Those who teach [the scripts] are unable to do high-quality research themselves, and though there is nothing to stop them from inquiring, the partisans of received wisdom ridicule those who like to ask questions, and offer far-fetched interpretations [of the correct way of writing the characters]. As Zhaizhong [Xie Lingyun 謝靈運, 385–433] says in his preface, “After small-seal script dispersed, bafen script was born; when bafen was destroyed, clerical script made its appearance. Clerical script is orderly but running script is harmful; running script is [pushed to] madness, and draft script becomes wild. From clerical script onwards, these are not scripts I wish to look at.”

晉宋而下,通篆籒者寡。唯碑碣印記,時用數字傳授者,未克研精,何 妨檢討。盜聽者恥於好問,加之穿鑿。齋中序云:「小篆散而八分生, 八分破而隷書出。隷書序而行書弊,行書狂而草書聖。自隷已下,吾不欲觀之矣。」Footnote 96