South China's Pearl River Delta is one of the world's most fascinating and complex ecosystems. More of an inland sea than a classic delta,Footnote 1 it supports millions of people who live on or near its margins (Map 1). Located along the southern edge of this waterworld is a tidewater expanse of oyster beds and brackish-water marshes, known as Laufaushan, “Floating Mountain”Footnote 2—a term that captures its beauty and ever-changing topography. This article explores the relationship between landowning farmers who laid claim to this stretch of coastline and the itinerants who harvested the rich bounty of sea products along the shore.

MAP 1 Pearl River Delta and Hong Kong New Territories, 1898–1978 (Colonial domain shaded)

In many respects there are parallels between the Pearl River Delta and the ecosystems described by James Scott in his history of Southeast Asia's “anarchist” highlands.Footnote 3 Cynthia Chou's ethnography of migratory fishing specialists who inhabit the saltwater margins of Indonesia also presents important comparative perspectives.Footnote 4 Scott and Chou focus on regions where state authorities were essentially absent, except for punitive raids and episodic attempts to put down rebellions.

As numerous historians have documented,Footnote 5 China's southern coast was also an unruly frontier until the mid-twentieth century. Dian Murry's description is particularly apt:

[This region] must be seen not as a simple strip of land demarcating land and sea, but rather as a large and somewhat indeterminant region embracing a variety of settlement patterns. Just as there was an ‘inner Asian frontier’ … where sedentary agriculture … gives way to pastoral nomadism, … so here, in the south, there was a maritime frontier where sedentary settlement patterns gradually yielded to those of maritime nomadism.”Footnote 6

The coastal terrain explored in this article subsumed an array of micro-ecosystems—each exploited by occupational specialists who were, in turn, monitored by a security force maintained by landowning interests. Members of this organization also guarded the industries that emerged along the coast: oyster processing, lime smelting, salt production, brickmaking, fish preservation, and marketing. Banditry was a constant threat. Laufaushan's commercial system would not have been possible without this internal security system—on guard, twenty-four hours a day, every day of the year.

Background: Ethnographic Fieldwork Along the Hong Kong Coast

In 1898, a 365 square-mile section of land adjacent to the colony of Hong Kong was leased by the British government for a period of 99 years. Laufaushan and the villages discussed in this article were thus incorporated into what became known as the “New Territories” and were subject to colonial administration until 1997—at which point control reverted to China. Approximately 600 villages of various sizes and complexities were incorporated into this colonial domain. Fewer than 100 British (English/Scottish/Welsh/Irish) officials and police officers were in charge; they, in turn, were assisted by hundreds of local Chinese interpreter-assistants and Punjabi (Sikh and Muslim) police patrolmen. A brief and somewhat disorganized resistance to the British takeover emerged among landowning elites and their tenant supporters in early 1899, but this was quickly extinguished in what became known as the “Six Days War.”Footnote 7

The New Territories, like much of China's southern coast, were dominated by large, single-surname/single-lineage villages that held the best land and controlled local commerce. Two of these villages, Ha Tsuen 厦村 and San Tin 新田, are the focus of this article. In 1911 Ha Tsuen had a population of approximately 1,200 people; San Tin had just under 1,100.Footnote 8 All resident males in these villages (save for a handful of slave-retainersFootnote 9) shared the same surname: Teng (鄧) in Ha Tsuen, Man (文) in San Tin. All daughters married-out of the community and all wives married-in from other communities—reinforcing an androcentric culture that rivaled anything found in southern Italy or northern India.

Ha Tsuen and San Tin were also branches of larger, multi-community surname alliances known in the anthropological literature as higher-order lineages.Footnote 10 The Teng higher-order-lineage (H-O-L) included four major village-complexes, all of which fell under British control in 1898 and continued to cooperate (and, at times, feud among themselves) throughout the twentieth century and beyond. The Man H-O-L has a different, and more complex history: in 1898 the new border was demarcated 300 yards north of San Tin. Regular social interaction with the six other Man lineage-villages immediately north of the border was severed in 1941 (following the Japanese invasion of Hong Kong) and did not resume until 1997—when the New Territories was “repatriated” (回歸) to Chinese control.Footnote 11

The landscape of the New Territories was similar to that of other Guangdong coastal regions: Cantonese-speaking communities such as Ha Tsuen and San Tin dominated the best paddy lands in the alluvial plains created by delta rivers, while Hakka-speakers settled in the hills interspersed throughout the landscape. Until the 1910–1912 completion of the Castle Peak Road system, which looped through the northern New Territories, land transport was restricted to single-file paths and cattle trails.Footnote 12 Prior to that date, Ha Tsuen and San Tin depended on ferries and cargo barges to import supplies and carry produce (crops and industrial goods) to market. Lorry traffic, introduced in the late 1920s, transformed the economy and brought the two villages into closer contact with Hong Kong's urban centers, 20 miles to the south.

Ha Tsuen and San Tin were highly organized, close-knit rural communities—in the sense that residents knew each other intimately and outsiders could not walk into these villages without notice (or challenge). Walls and gates were everywhere and fierce watchdogs guarded the narrow paths, threatening anyone whose scent they did not recognize.Footnote 13 Older women sat outside the gates of walled compounds (圍) and did not hesitate to challenge strangers: “Who are you looking for?!” (Cantonese: Wan-bingo-a?! 搵邊個呀?). Hawkers were not allowed into the village after dark and had to notify local authorities before they could sell their wares. The local security force (巡丁)Footnote 14 patrolled at night, ringing a gong every three hours to reassure residents: “Three o'clock [a.m.] and all is well.”Footnote 15 Empty houses were not rented or sold to outsidersFootnote 16 (non-lineage members) until well into the 1990s. By contrast, the nearby tenant villages and settlements of shoreline workers (see below) were essentially unguarded and subject to banditry and intrusion.

Ethnographic research for this article began in 1969, when Rubie Watson and I lived in San Tin—a specialized farming community that emerged on the edge of the delta's saline marshes in the seventeenth century (see Map 1). By the middle of the eighteenth century this otherwise hostile environment had been converted into six polders containing over 480 acres of brackish-water paddy land.Footnote 17 The red rice produced on these polders (沙田) sustained the local farmers for the next three centuries—until political circumstances and economic opportunities led to a full-scale shift to overseas emigration in the 1960s.Footnote 18

In 1977 Rubie Watson began her ethnographic study of Ha Tsuen, 7 miles south of San Tin. During that period (1977–1978) I resided in Ha Tsuen but spent most of my days in the nearby hinterland, where I conducted interviews in tenant villages and coastal settlements along the Laufaushan coast (Map 2). This article draws primarily on first-hand information (based on interviews and observations) collected during those two ethnographic experiences.

Coastal Ecosystems: Laufaushan

Founders of the Teng lineage settled in the rich plain near Laufaushan in the fourteenth century and dominated the economy of their district (鄕) until the late-twentieth century.Footnote 19 A stone tablet (dated 1751) in Ha Tsuen's ancestral hall notes that founding ancestors chose this area because of its ecological and commercial advantages: “[After a] close study of the landscape, and viewing the rich advantages of Ha Tsuen's broad expanse of land, fish, and salt, [our ancestors] moved from Kam Tin [their original home] to live in Ha Tsuen.”Footnote 20 The connection between land and sea thus distinguished the Ha Tsuen Teng from competing lineages that controlled the inland portions of the New Territories.Footnote 21

Teng pioneers constructed a double-crop rice paddy system that produced a prize variety of white rice that was always in demand in regional markets. Ha Tsuen landlords and ancestral estates claimed ownership rights to all land in their district. Besides rice fields and vegetable plots, these claims included the shoreline, estuaries, tidal flats, and expanses of reeds extending 200 yards or more into Deep Bay (see Map 2)—an odd name for what was essentially a flat estuary with two constantly changing channels for the passage of shallow-draft boats and barges.Footnote 22 Anyone wishing to exploit this coastal territory had to pay rent to the Teng ancestral hall, which held ownership rights to most of the Laufaushan coastline and hundreds of acres of prime rice land.Footnote 23

MAP 2 Deep Bay and Yuen Long District, 1969–1978

Locally recognized categories of shoreline property included tidal flats (oyster beds), fishponds, duck ports,Footnote 24 commercial lots (fish shops, tea houses, restaurants), lime kilns, brick kilns, ferry piers, rocky shorelines (fish traps and stationary dip-nets), brackish-water reed fields (raw material for baskets and sleeping mats), and grassy hills above the shoreline (a primary source of domestic cooking fuel).Footnote 25

The sandy beaches of Laufaushan constituted a carefully monitored source of income for Ha Tsuen's ancestor hall. Until the introduction of nylon netting in the 1960s, fishnets were made of ramie and linen—natural fibers that required regular drying after use.Footnote 26 The beaches also supported acres of drying platforms for salt fish, a common staple of the southern Chinese diet.Footnote 27 Larger varieties of oysters were also preserved in this manner. In the 1950s, the resources associated with Laufaushan constituted approximately 25 percent of the Teng ancestral hall's funds (until income declined in the late 1970s).Footnote 28

Oysters: the Delta's Premier Resource

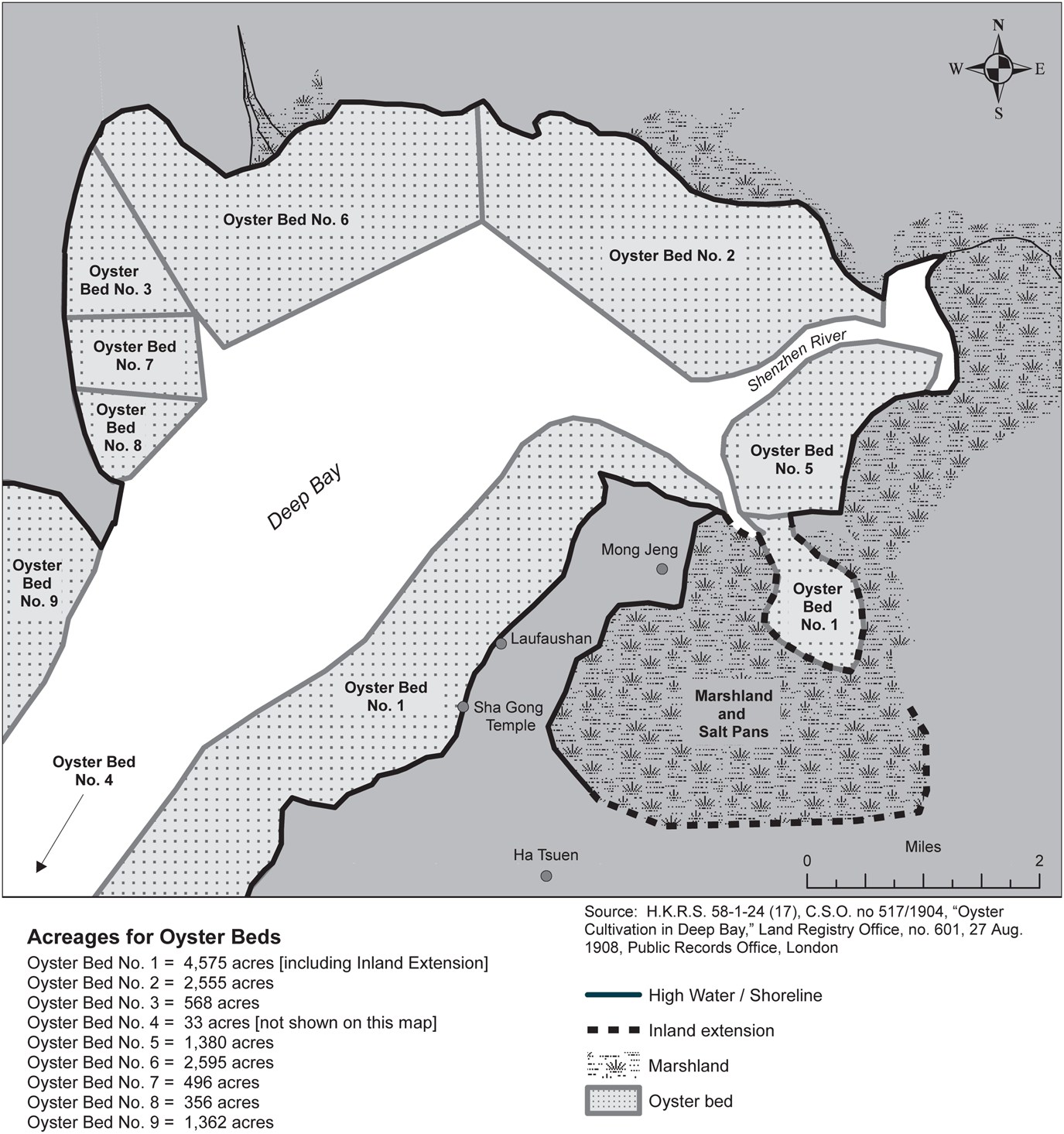

In 1667 the imperial Chinese government granted a deedFootnote 29 to Teng pioneer settlers for the right to collect rent for use of the oyster beds established along the Laufaushan coast. This deed was valid until 1909, when the recently established British colonial administration extended tenancy rights in the form of renewable, twenty-one-year crown leases.Footnote 30 The five largest beds had auspicious names (裕安塘,公和塘,裕和塘,合和塘,豐裕塘), all ending with the character tang (塘), commonly used for ponds or enclosures. During the first decade of the twentieth century, the Laufaushan oyster beds were clustered in tidal waters covering 2,100 hectares (approximately 5,200 English acres).Footnote 31 Map 3 shows the general outline of this oyster terrain; most of these beds date from the mid-seventeenth century and were registered in Qing dynastic archives. Qing authorities leased the beds to designated claimants (including the estate of Ha Tsuen's ancestral hall) and demanded an annual payment for their use.Footnote 32 It appears that British colonial officials devised this map, in part, as a political maneuver in 1904 to claim future territorial rights in Deep Bay and adjoining waters. It is almost certain that oyster production was not carried out in all of the territory covered by these numbered beds. Only a few hundred acres of Yuwutong (裕和塘), which fronted on the Laufaushan coast, was actually devoted to oysters.Footnote 33

Map 3 Oyster Territory in Deep Bay, British Colonial Depictions, 1904

Laufaushan oysters were prized for their tenderness and delicate taste. Some of the larger varieties took up to five years to reach full maturity and were used primarily to make oyster sauce—an essential ingredient of Cantonese cuisine. Favorable water conditions, mild tides, and the skills of local oyster workers were responsible for Laufaushan's primary product. Although oysters were considered to be a luxury, the demand was strong, even during periods of economic recession. This is due, in large part, to a peculiarity of the Cantonese ethnozoological system: villagers classify the oyster as a plant, not an animal. The critical distinction is based on the premise that oysters, unlike other sea creatures, do not move (at least perceptibly) of their own volition. Oysters are “planted” (種) in “fields” (田) like any other crop;Footnote 34 they are neither trapped in nets, nor caught with hooks. Furthermore, oysters are analogous to rice in that the immature spat (like rice sprouts) are transplanted from nurseries to finishing beds, which are the size of large rice paddies, where they grow to full size.Footnote 35 Ha Tsuen residents also claimed that oysters—like plants—do not have souls or spirits (shen 神) and, thus, cannot be killed (sha 殺) when they are cooked or eaten.Footnote 36

The demand for fresh oysters was particularly high during religious observances that proscribe the consumption of animal flesh. Until the 1980s, many local families observed vegetarian restrictions on the first and fifteenth of each lunar month. During the five-day sequence of community purification rites (jiao 醮),Footnote 37 a festival that occurs every ten years in Ha Tsuen District, nothing that fits the category “meat” or “seafood delicacy”Footnote 38 can be brought into the community—let alone eaten. In Ha Tsuen this period was marked by the consumption of (literally) tons of fresh oysters delivered from Laufaushan. Rather than treating the jiao as a period of culinary restraint or abstinence, therefore, older people in Ha Tsuen sometimes spoke of the festival as “oyster eating time.”

Oyster Sauce, Lime Smelting, and Brick Kilns

Laufaushan was also the center for small-scale industries that were dependent on the oyster beds for raw materials. One of the wealthiest families in Ha Tsuen started an oyster sauce (蠔油) factory at Laufaushan in the early 1900s; the enterpriseFootnote 39 employed up to twenty local men and women by the 1960s, many of whom had moved to Laufaushan from other parts of the Pearl River Delta. The company continued production until 1983, when it was closed due to a pollution crisis in the local oyster beds.Footnote 40 The bottled product carried a label identifying it, in English, as “Tang's Sauce.”Footnote 41 It was marketed in Hong Kong, Southeast Asia, and overseas Chinese settlements—including San Francisco's Chinatown and London's Soho District.

The sauce was made by boiling oysters and reducing the fluid to a thick, brown residue. Oyster sauce has a long history in the Pearl River Delta. It was an essential flavoring for the “common pot” banquets that marked weddings, housewarmings, and births of male offspring.Footnote 42 Every village had its own banquet chef who stewed and thickened dried oysters with local herbs to produce a distinctive blend. Recipes were passed from father to son, becoming the equivalent of intellectual property—although village chefs were never paid for their services.Footnote 43

Residents of Laufaushan also worked in kilns (灰窰) that produced lime from crushed oyster shells. The kilns were owned by Teng entrepreneurs who purchased mounds of spent shells, which—like the oysters—were deemed to be the property of Ha Tsuen's ancestral hall. There were four lime kilns in Laufaushan, one of which was still operating in the 1980s.Footnote 44 The lime had many uses, including egg preservation, cloth-dying, leather-tanning, wall-plastering, waterproofing for nets and rope, and as a caulking agent for wooden boats.Footnote 45 Spent shells were also shipped (on narrow barges) to these kilns from oyster beds in the creeks leading to Yuen Long Market.Footnote 46

The Man lineage could not have survived on the margins of Deep Bay without oyster shell lime, a flocculating agent that made it possible for water buffalo teams to plow the otherwise sticky, viscous soil.Footnote 47 Lime was also the active agent in zhuangli 樁籬—a concrete-like building material of uncommon strength and longevity.Footnote 48 Villagers claimed that zhuangli is so strong that bandits knew it was not worth their time to attack walls made of it. Many zhuangli walls in Ha Tsuen remain intact today, 300 years after construction.

Another set of kilns near the village of Mong Jeng (see Map 2) produced two types of bricks from mud and clay harvested in nearby marshlands: low-fired red bricks and high-fired green bricks (青磚 reflecting their color). Green bricks were finished in “step-kilns” (梯窰) situated on hillsides, thereby allowing an up-draft required for high temperatures.Footnote 49 Wealthy households paid high prices for green bricks which were far more resistant to dynamite and iron crowbars—the two essential tools of housebreaking in south China. Bandits who operated in the delta knew that walls built with green brick also had interior layers of lime-based zhuangli concrete, making it more profitable to focus on red brick structures.

The Water Patrol: A Commercial Security Force

Prior to the 1950s, commercial enterprises along the Pearl River Delta could not count on the Chinese government (or, in the New Territories, the British Colonial administration) to provide routine protection against bandits and predatory neighbors.Footnote 50 Specialized security forces thus emerged to guard local industries of any consequence. In the nearby market town of Yuen Long, for instance, shop and mill owners supported their own street patrols that operated day and night.Footnote 51 C. K. Yang describes a “navigation protection corps” that operated in delta waters near Guangzhou to provide armed guards for passenger boats and freighters.Footnote 52

Along the Laufaushan coast, security was assured by an organization known locally as the “water patrol” (水巡).Footnote 53 Rents and fees for the use of oyster beds, lime kilns, fish shops, restaurants, and associated industries were collected by members of this specialized force. These fees, combined with paddy field rents, constituted the primary sources of income for the Teng ancestral hall (i.e., the estate of the founding ancestor and, by extension, the property of all living males who could demonstrate descent from that ancestor). The water patrol's leader, known locally as the “water master” (水長), was selected—by auction—during a formal meeting held in Ha Tsuen's ancestral hall, once every eight years. Auction winners paid an annual sum to the hall and sponsored a banquet for Teng elders who were asked to legitimize the transaction by “chopping” a cloth document with their signature stones.Footnote 54 In 1946 the office fetched HK$500 (per annum), an impressive sum for that period; by 1970 the winning bid had increased to HK$4,000.Footnote 55 In return, the leader and his patrolmen received 3 percent of the harvested oysters (either in kind or in cash equivalent following sale) as their fee for protecting the crop. They also collected an additional 15 percent for the Teng ancestral hall—the legally recognized holder of the subsoil rights (地骨 lit. “earth bones”) of the oyster beds. The remaining 82 percent ended up in the hands of the leaseholders who held the cultivation rights (地皮, “earth skin”).Footnote 56 Leaseholders were responsible for paying the oyster workers (see discussion below), plus additional expenses associated with harvesting, transportation, and marketing.

The water master recruited his own team—all of whom (like the master himself) were members of the Teng lineage. Patrolmen received a share of the harvested oysters and any additional funds collected for guarding businesses in Laufaushan Market. These were, by local standards, lucrative sources of income for men in their twenties and thirties. Membership varied from six full-time operatives in the 1930s to ten during the 1960s.

The Teng, like all major lineages in the Pearl River Delta, also maintained a land-based security force (巡丁)Footnote 57 that patrolled villages and fields in Ha Tsuen District. The activities of the two security forces did not overlap, although there was close coordination between leaders who understood that their primary duty was to maintain the territorial hegemony of the Teng lineage.

The duties of water patrolmen were first, to guard the oyster beds and, second, to protect commercial enterprises that emerged along the coast (seafood processing, lime smelting, shoreline fishing, boat provisioning, and fish marketing). Until the 1970s when restaurantsFootnote 58 and a fresh fish market expanded at Laufaushan, patrolmen devoted most of their time to watching over the oyster beds and making sure that oyster workers did not encroach on territory outside their assigned allotments. Thievery was a constant threat. At low tide the oysters were exposed to the boat and barge traffic along Deep Bay, leading to and from the market town of Shenzhen. Two or more patrolmen were on guard, day and night, to ensure that unauthorized persons did not venture into the beds. Nighttime raids by small groups of oyster thieves who arrived in boats was an ever-present danger. If trouble arose, a loud gong summoned other patrolmen (and Teng men who happened to be in the vicinity) who rushed to the coast.

Oyster workers were well known to Teng patrolmen who were quick to spot strangers. Starting in the 1950s, according to Ha Tsuen elders, harvesting permits were required before anyone could remove oysters from the beds or offer them for sale in the nearby market. These documents—printed ticketsFootnote 59 inscribed with the date and name of harvester—had to be renewed each morning until the harvest was finished, a procedure that allowed patrolmen to check for intrusions into neighboring beds (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Oyster Harvesting Permit, 1977, Water Patrol, Laufaushan (Photo by J. L. Watson©)

The water master and his part-time assistant/accountantFootnote 60 lived with their families in Ha Tsuen. Ordinary patrolmen resided in a barracks-like headquarters at Laufaushan and were on call twenty-four hours a day, 365 days a year. They slept in shifts on hammocks or camp cots arranged haphazardly around the walls of their barracks and cooked for themselves on coal-burning grills. The majority of water patrolmen were preadapted to this spartan life: they had spent their youth (ages 13–20) in “bachelor houses” (男仔屋) located in the back rooms of Ha Tsuen's ancestral halls and study halls (書房/書院). Overcrowding was a serious problem in tightly nucleated villages such as Ha Tsuen, and many young men were—quite literally—pushed out (推出) of their parents’ homes at puberty.Footnote 61 Two bachelor halls were still operating in Ha Tsuen during the 1970s.

Most water patrolmen were second or third sons of Ha Tsuen tenant farmers and therefore could not count on their families for help with bride-wealth payments.Footnote 62 If they wished to marry and start their own families, they were completely dependent on their own resources. The fees generated by guarding oysters and Laufaushan's auxiliary industries thus made the water patrol an especially attractive occupation for these young bachelors.Footnote 63

Oyster Theft and Boundary Control

Oyster thievery reached its peak, according to retired patrolmen, during the late 1940s and early 1950s, when immigrants from Guangdong Province flooded into the New Territories.Footnote 64 In 1946 the Commissioner of Hong Kong Police authorized the water patrol to carry rifles,Footnote 65 legalizing a practice that had begun surreptitiously in the 1920s when surplus weapons (Enfield rifles and pistols from First World War battlefields) were readily available in the Pearl River Delta.Footnote 66 According to retired patrolmen, the level of violence increased alarmingly during the late 1940s and early 1950s, a period marked by incursions of Nationalist and Communist forces into Hong Kong territory. No member of the Teng lineage was killed while protecting the local oyster beds, but several patrolmen were involved in shootouts with “bandits” (a category that included any armed outsider) in the 1940s.

In 1947 the Hong Kong Government built a police station at Laufaushan and “encouraged” Teng patrolmen to relocate their headquarters from a hill overlooking the oyster beds to a new building in the nearby fish market.Footnote 67 The move underscored a fundamental change in the security system for Ha Tsuen District. Henceforth, the Royal Hong Kong Police assumed the burden of suppressing bandits and monitoring the entry of immigrants from China. Nonetheless, Teng water patrolmen continued to carry firearms, especially during night patrols, until the early 1960s.

Besides watching for thieves, patrolmen were also responsible for verifying the boundaries of oyster beds and for monitoring harvest procedures. These duties presented special problems, given that the Laufaushan mud flats are completely devoid of natural features and—without flag poles that had to be repositioned after every storm—it was impossible to distinguish one oyster bed from another (maps in the conventional sense did not exist).Footnote 68 The Teng relied on mental maps that were passed from father to son in particular patrilines associated with the oyster business.Footnote 69 Leaders of the water patrol were always careful to employ two or three of these specialists as full-time patrolmen. Their ancestors had devised an indigenous system of surveying.Footnote 70 Teng surveyors used distant hills and islands along the western shores of Deep Bay, plus rocks and trees on the Laufaushan coast, as sighting points to align boundary flags in the mud flats. These skills were kept strictly within specialist patrilines. Surveyors always worked alone and the boundary specifications were never recorded in writing.Footnote 71 Their main duties were to realign the flags after storms and to make periodic checks to ensure that oyster workers had not moved into adjoining beds.

Exploiting the Shoreline: Long-nets and Fish Traps

Teng patrolmen were also responsible for regulating all types of fishing that emerged along the shores of Laufaushan. They could not, of course, monitor the activities of specialists who fished in deep waters beyond the coast, but they did control the small-scale entrepreneurs who operated within the low tide zone.

Residents of Ha Tsuen District had a complex lexicon that distinguished between (a) fishing with nets towed behind boats and (b) fishing from the shore. The latter category included a wide variety of methods that employed nets and traps.Footnote 72 Large dip-nets—permanently attached to wooden huts—were located on shore or in shallow mudflats.Footnote 73 Rattan basket-traps (used primarily to catch shrimp, crabs, and small fish) were placed near sluice gates, river mouths, or narrow channels. Fish weirs were created by piling rows of stones along tidal flats that filled with water during hightide and left fish trapped at low tide.Footnote 74

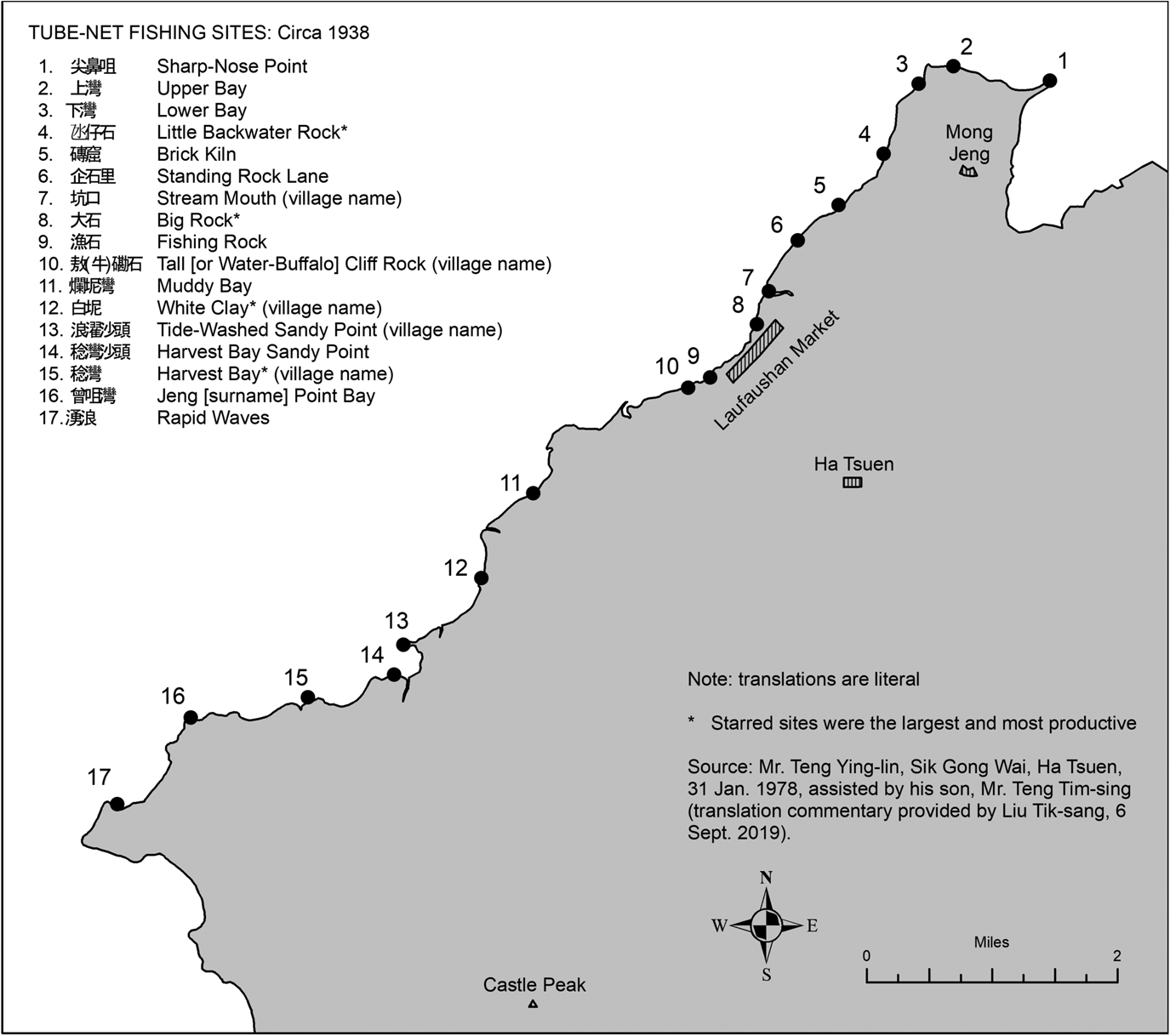

Stationary tube-nets (網魚) constituted by far the most lucrative form of shore fishing, and as such they were carefully regulated by Ha Tsuen's water patrol. Tube-nets measured two meters wide at the mouth and up to 200 meters in length, sufficient to capture entire schools of fish. Teams of 12 to 15 men banded together to set the nets and haul in the catch during low tide; Ha Tsuen elders claimed that, in the 1930s, it was not uncommon to capture up to 500 pounds of high-quality fish on a good day.Footnote 75 Seventeen sites, each with its own place name (see Map 4), were set aside specifically for tube-netting in Ha Tsuen District. In 1978 several Teng elders could recite the entire list, even though they had not visited many of the sites for over two decades. Questions about tube-nets sparked a series of nostalgic stories, most of which focused on male camaraderie among teams of young men who spent long summer nights drinking together under the stars, watching the nets, and dreaming of the big catch that would make them rich. Three men, interviewed in their seventies and eighties, confided that these were among the happiest moments of their lives, even though they had earned barely enough to cover their expenses.

Map 4 Tube-Net Fishing Sites, Laufaushan Coast, ca. 1938

As with all categories of shore land and tidal flats in Ha Tsuen District, the rights to collect fees for use of the seventeen tube-net sites were controlled by the Teng ancestral hall (Yaugungtang 友恭堂). Managers of the hall held an annual auction, restricted to members of the lineage, for rights to exploit these sites. This was an informal, entirely local arrangement. Unlike rights to land and oyster beds, the colonial administration (and before 1898, the Qing imperial government) was neither involved with nor aware of these financial transactions. Several of the sites adjoined land owned by non-Teng farmers who lived in villages miles from Ha Tsuen. The reputation of the Teng water guard was enough to ensure that they were never challenged.

In 1936, according to one of the participants, a team of twelve men (all Teng) paid HK$500 for control of the eight most productive sites.Footnote 76 Interest in long-net fishing declined in the 1950s, due largely to the rising attractions of wage labor. It became increasingly difficult to put together teams of young men who had enough time to manage the nets. By the early 1960s no one was bothering to repair the nets and most of the sites had been abandoned or turned over to small-scale fish trappers (using rattan baskets) who paid a nominal rent to the Teng ancestral hall.

All resources taken from tidal flats bordering Ha Tsuen District were thus subject to fees collected by the Teng water patrol. This policy led to frequent confrontations with tenant farmersFootnote 77 who lived in small villages near the water and relied on shoreline foraging to supplement their diets. Shrimp, crab, and small fish constituted an important source of animal protein for these farmers, whose main staple was sweet potato gruel. In the early 1950s Teng patrolmen discovered a group of women from a tenant village collecting shrimp near one of the long-net sites. As they had not paid fees to the water patrol for fishing rights, their catch was confiscated and their baskets burned. Male residents of the village in question were so incensed by this action that they marched on the water patrol headquarters and threatened to burn it down. According to witnesses who recounted the event, Teng patrolmen brandished rifles to keep the crowd at bay until police officers from the nearby Laufaushan station arrived to take charge of the situation.Footnote 78

Fishing and Social Stigma: Drawing Social Boundaries

The discovery that Teng males regularly participated in shoreline fishing activities came as a surprise when I first learned of it in 1977. Earlier research in San Tin had led me to conclude that Cantonese farmers drew a clear social boundary between people who “plow fields” (Cantonese gaang-tihn 耕田) and those who “catch fish” (juk-yu 捉魚). The residents of San Tin were always keen to separate themselves from the fisherpeople who lived in an encampment of boats and ramshackle mat-sheds (茅屋) near Ha Wan Tsuen, near the mouth of the Shenzhen River—on the outer edge of San Tin District. No self-respecting member of the Man lineage (I was told repeatedly) would engage in full- or even part-time fishing. It was acceptable to manage fresh-water ponds, but this was treated as a subcategory of farming.Footnote 79 The Man spurned all other forms of coastal fishing and hired residents of Ha Wan Tsuen to operate the stake-nets that lined the reclamation dikes in San Tin District.Footnote 80

When I first raised this question with residents of Ha Tsuen District in 1977, many older people claimed that there was a wide social chasm between themselves (land-based farmers) and the fisherpeople who lived on boats anchored near Laufaushan. As my research progressed, however, it became evident that they drew a finer set of distinctions than their counterparts in San Tin and, hence, were less rigid in their definition of social boundaries relating to the exploitation of coastal resources.

In both districts there was a fundamental division between those who lived in brick and stone-built houses on land and those who lived on boats (floating, beached, or permanently anchored), or in temporary mat-sheds. The Teng, however, further distinguished between specialists who treated fishing as a full-time occupation and farmers who engaged in part-time shoreline fishing on an occasional basis to supplement their income.Footnote 81 Until the 1980s many land-based farmers in the Hong Kong New Territories and Guangdong Province socially ostracized full-time fisherpeople and assigned them to the ethnic category daahn-ga yahn 蛋家人, a Cantonese slur that is difficult to translate but means, literally, “egg people” (often Romanized as Tanka). Eugene Anderson notes that the full-time fisherpeople he lived among in the mid-1960s did not use this term and deeply resented it; they referred to themselves as “people of the water” (Cantonese shui-sheung yahn, 水上人).Footnote 82

Many farmers in the New Territories claimed that fisherpeople were descendants of non-Han peoples who had inhabited the delta before the Tang dynastic era (fifth century), when founders of several local lineages first began emigrating to coastal Guangdong from Jiangxi Province.Footnote 83 But genetic evidence does not support such claims. After years of research in the Pearl River Delta, Huang Xinmei, a medical anthropologist at Zhongshan University, concluded that the boat dwelling people of Panyu and Zhongshan Xian, Guangdong Province (identified in her research as 水上居民 “water-dwelling people”), were not significantly different from their land-based, farmer neighbors.Footnote 84 Furthermore, the main thrust of Barbara Ward's path-breaking study of the Hong Kong “boatpeople” is that, culturally and linguistically, they are little different from Cantonese-speaking land people.Footnote 85

The ever-changing nature of social/ethnic identity in the Pearl River Delta is evident in the work of Helen Siu, who has studied historical transformations in Xinhui County, Guangdong Province, 60 miles west of Laufaushan.Footnote 86 Siu notes that one of the dominant lineages in this region may well have started—three centuries earlier—as “hired hands” for land reclamation projects and were likely to have been of Dan (fisherpeople) origin. Local landlords referred to such workers as sha-min 沙民, literally “sand people.”Footnote 87 Siu's ethnic transformation argument is also supported by David Faure's study of land development in the Pearl River Delta.Footnote 88

Nonetheless, the social stigma of occupational origin was still very much alive in the New Territories well into the 1970s. People with fishing origins who wished to “pass” into the untainted status of landed Cantonese had to cut all ties with their past, lest it affect their job chances and marriage prospects.Footnote 89 This pattern of social conservatism may well be a consequence of the Pax Britannia that prevailed in the New Territories, as opposed to the dramatic revolutionary transformations that convulsed Xinhui County (and other parts of the Pearl River Delta) under Communist Party rule. The colonial administrators in rural Hong Kong did not attack and totally transform the preexisting systems of land ownership and social hierarchy they encountered in Ha Tsuen and San Tin Districts.Footnote 90 There were, as many observers have noted,Footnote 91 major changes in the economic, educational, and tenancy systems that underlay New Territories social life, but the Teng and Man lineages (along with their counterparts in British territory) continued to dominate social life in their respective districts until at least the 1990s. More will be said about these recent transformations in the final section of this article.

Oyster Workers and Social Marginality

In the 1960s and 1970s, many older villagers in the New Territories were suspicious of any “outcomers” (外來人) who were not generations-long residents of local communities. One such group was the community of oyster workers who lived in temporary, makeshift housesFootnote 92 along the Laufaushan coast. Theirs was a dangerous occupation that required diving (without oxygen tanks or sealed masks) and the underwater manipulation of stones and large shells that supported the oyster spat as they grew to maturity.Footnote 93 After a few hours of coaching from former water patrolmen, I learned to spot oyster workers by their scarred feet, caused by decades of treading on hidden debris in knee-deep water. The stones had to be reset after each storm to prevent mud from suffocating the oysters. Skill in operating mud-scooters was an essential feature of the tenders’ craft; these wooden sleds, propelled with one foot much like skateboards, were still in use at Laufaushan during the mid-1970s.Footnote 94

According to Liu Tik-sang, who has conducted ethnographic research on coastal ecosystems in the Pearl River Delta since the mid-1970s, Teng water patrolmen often referred to oyster workers by a term best translated as “oyster guys” (蠔佬), a designation that the specialists themselves resented.Footnote 95 Oyster workers, most of whom were surnamed Chan 陳, addressed each other by personal name or nickname—none of which local farmers professed to know or remember. Almost all of these oyster specialists were migrants from the Shajing 沙井 District in Dongguan County, Guangdong—25 miles north along the coast. Most had permanent (brick and tile) homes in sea-side villages in Shajing District and were registered as Shajing Commune members by the Chinese government.Footnote 96 As the Communist land reform campaigns (and associated political movements) proceeded in Shajing, however, many oyster workers began to build temporary homes in unregistered communities along the northern shore of the Laufaushan coast, where they resided throughout the year. This began to change, again, in the 1970s as the Cultural Revolution ended and many older oyster workers resumed the practice of returning to Shajing after retirement.Footnote 97

Farmers in Ha Tsuen District never fully accepted oyster workers as trustworthy neighbors and sometimes referred to them as “West Roaders” (Cantonese sai-louh yahn 西路人), a local term that has derogatory overtones given that “west” is depicted in popular religious iconography as the territory of darkness and death.Footnote 98 During interviews, older people also used “West Roader” as a synonym for bandits who raided New Territories villages during the 1920s and 1930s. By implication, oyster workers were equated with untrustworthy drifters no matter how many generations they had worked in the Laufaushan oyster beds.

My 1978 interviews in Laufaushan revealed a strikingly different picture: oyster workers perceived themselves as members of a skilled occupation with its own secrets and complex history. Senior specialists were addressed by their colleagues as “master” (師傅), much like the Cantonese woodcarvers described by Eugene Cooper.Footnote 99 Specific patrilines maintained a monopoly on esoteric skills that were essential to oyster production. Perhaps the most interesting was the ability to judge water salinity by its taste. Oysters are susceptible to rapid changes in salt content, which can kill an entire crop overnight.Footnote 100 During droughts, and surges of fresh water following typhoons, oyster masters had to judge when it was time to pull the shells, even if they had not reached full maturity.

The skill of water tasting (done every day at high tide) was passed from father to son. Not all oyster workers had such skills because, as one master put it, “you have to learn while your taste-sense (Cantonese hau-meih 口味) is still young.” Teng water patrolmen respected the skills of the Laufaushan taste-masters and allowed them to recruit their own teams of Shajing oyster workers. Jakob Eyferth's study of “skill reproduction” among Chinese paper makersFootnote 101 presents interesting comparisons to the complex demands of oyster farming. Both communities of specialists depended upon the transfer of techniques and knowledge within restricted lines of descent.

Salt and Salt Workers

The industries along the Pearl River Delta consumed vast quantities of low-grade sea salt which was dried in shallow pans adjoining the coast. Salt was used as a preservative for oysters, shrimp, crabs, and other sea foods that were shipped to markets throughout South China and Southeast Asia.Footnote 102 Allied industries—including food preservation (pickling), peanut oil processing, basket weaving, and clothing manufacture—needed salt in large quantities.

Several elders in San Tin and Ha Tsuen noted that small-scale saltpans existed in their districts until the mid-nineteenth century.Footnote 103 One of the wealthiest members of the Man lineage built an elegant, multi-chambered mansion for his extended family on the outskirts of San Tin and purchased a low-level imperial title in the 1860s—reputedly from the proceeds of salt trafficking.Footnote 104 An eighteenth-century TengFootnote 105 is also said to have become wealthy on the proceeds of saltpans located at a long-abandoned site near Ha Tsuen, known to local people as Yim Chong (鹽廠 lit. “salt-yard”). Ha Tsuen's walled market (厦村市) housed several refineries that boiled brine for the manufacture of block-salt that was shipped to urban markets in Hong Kong and Guangzhou.Footnote 106 By the early twentieth century, however, physical evidence of local saltworks had disappeared as a consequence of extensive land reclamation projects that transformed the coastal flats in both districts.Footnote 107

The Tou (陶) lineage, settled in a district adjoining Ha Tsuen, maintained a specialized “salt patrol” (鹽巡), which operated until the mid-nineteenth century, to protect their drying facilities along the Tun Mun Coast.Footnote 108 According to Tou elders,Footnote 109 salt was a tempting target for thieves because it was always in short supply in nearby markets, where it was used to preserve fish, vegetables, and pickles. The leader of the salt patrol was chosen during an annual auction in the Tou ancestral hall. Patrolmen (all of whom had to be members of the Tou lineage) received a share of the finished salt every year, which they could sell in local markets. As in Ha Tsuen District, the duties and territorial purview of this specialized organization did not overlap with the activities of the Tou village patrol (巡丁). Local salt workers were described (by Tou elders) as fisherpeoples and other marginalized “outcomers” (外來人) who lived along the nearby coast.Footnote 110

In San Tin District these specialists were known by a Cantonese term, yim-tin lo 鹽田佬, which translates as “salt-field guys.”Footnote 111 Little is known about the social organization and the division of labor that governed salt production in Xin'an County, even though saltpans existed along the coast during the Ming dynastic era (1368–1644) and probably as early as the tenth century.Footnote 112 The county gazetteer includes a detailed section on the bureaucratic system devised by state authorities to monitor and tax salt production, starting in 1369.Footnote 113 Approximately 3,000 salt makers were registered (for tax purposes) with the Xin'an salt bureau but, as Peter Ng and Hugh Baker note,Footnote 114 there were probably many more unregistered producers in the delta—including the small-scale enterprises that emerged in San Tin and Ha Tsuen Districts.

Marginal Specialists on the Delta's Edge

By the mid-eighteenth-century communities of specialists emerged to exploit resource microniches in the delta ecosystem. One such resource was the expanse of reeds (鹹水草 lit. “saltwater grass”) that flourished in the brackish-water marshes near San Tin and the village of Mong Jeng in Ha Tsuen District. The finest quality reeds were woven into sleeping mats that had the unique quality of remaining cool during the hottest of summer nights; not surprisingly there was always a strong demand for these items in local markets.Footnote 115 Reeds were essential for the cottage weaving enterprises that produced baskets, hats, fish traps, salt bags, and dozens of other essential items sold throughout south China. Marsh grasses were also used as packing materials (for pottery and bottled products), fuel (for domestic and industrial purposes), and thatching for roofs and hut construction.Footnote 116 Water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes), a succulent used as pig feed,Footnote 117 was a major source of income for coastline foragers. Semi-permanent communities of reed gatherersFootnote 118 and basket weavers could still be found in the San Tin District until the early 1970s. During my 1969 interviews, these specialists insisted that they were not related to the residents of nearby waterfront settlements and objected when older residents of San Tin sometimes referred to them as “drifters” (Cantonese sui lau chaai 水流柴 lit. “floating driftwood/debris”).Footnote 119

The reed gatherers resided in mat-sheds along the outer dikes of reclamations owned by San Tin's main ancestral hall and were allowed to stay only as long as they served the interests of the Man lineage. A similar community emerged along a major dike system that was built in Ha Tsuen District during the early twentieth century. Residents of these two communities used boats on a regular basis but they lived and slept on land—an important distinction from their point of view. In addition to reed work, they were employed by managers of ancestral halls and reclamation companies to maintain dikes, dig ponds, and repair sluice gates.

In San Tin District the right to harvest reeds was auctioned each year in a local ancestral hall that also served as headquarters for the village patrol; bidding was restricted to members of the Man lineage. Auction winners hired groups of reed gatherers to do the actual harvesting and weaving. Allotments of finished mats, hats, and baskets were then sold to wholesalers in regional markets. Designated reed gatherers were granted exclusive use of the flat surfaces along reclamation dikes where they sorted, soaked, and dried the harvested reeds. San Tin's security force patrolled the area to keep fisherpeople from using the dikes to dry fish and shrimp—space for which was always in short supply.

Large flocks of ducks that fed on insects and small crustaceans in the saline marshes were an important feature of the local economy. The sight of an accomplished duck herder, guiding his ravenous horde with a 30-foot bamboo pole as they swarmed along the reclamation dikes, is truly one of the wonders of delta life.Footnote 120 In spite of the obvious skills involved, local farmers considered duck herding to be a demeaning occupation.Footnote 121 Most households in Ha Tsuen and San Tin Districts kept a few chickensFootnote 122 or geese for personal consumption, but ducks were potentially more destructive of crops and required constant attention—something a busy farmer could ill afford. Duck herders, like reed gatherers, operated under the auspices of Man entrepreneurs who owned the herds.Footnote 123 The butchered and dried ducks ended up in meat shops and restaurants throughout the delta.

Social Boundaries in the Delta

The most significant cultural feature separating people who lived along the water margin of the delta was the practice of endogamy—people married within their own social category and avoided marriages across categories. In the Cantonese context, it is (usually) the woman who marries out of her parental household and moves into the home of her husband's parents (or her husband's household).Footnote 124 The Teng of Ha Tsuen had complex marriage alliances with other landed lineages in the delta region, including the Man of San Tin. These marriages were instrumental in building links between the two communities—reinforcing their power and influence. Fisherpeople and oyster workers also tended to marry within their own occupational category and were strictly proscribed as marriage mates for landed villagers—at least in the two districts under study.

In other parts of the Pearl River Delta, isolated cases of intermarriage between fisherpeople and farmers have been reported—but even these few examples were met by considerable resistance. James Hayes reports one such case that occurred on Lantau Island (in Hong Kong waters) during the 1940s. Residents of the village in question ostracized the in-marrying bride and her children; the family eventually moved to another community located on the New Territories mainland.Footnote 125 During four decades of field research in San Tin and Ha Tsuen Districts, I found no evidence to suggest that marriages of this nature ever existed in the Man or the Teng lineage.

Another important gauge of social interaction is commensality—the practice of dining together in public settings. In the 1960s and 1970s, residents of farming communities avoided teahouses or restaurants that served the fishing community and never (to my knowledge) invited fisherpeople—including those with whom they had business ties—to banquets or weddings. In the thirty or more banquets I have attended in New Territories lineage villages since my research began in 1969, I do not recall a single occasion when an oyster worker, a fisherperson, or a coastal itinerant appeared as a guest.

Nor did the processes of segregation between land and sea end at death. Like all land-owning lineages along the delta, the Teng and Man guarded their burial grounds with special vigilance. One of the most important tasks of the village patrol organizations in Ha Tsuen and San Tin was the regular monitoring of hills and shorelines in their districts. All legitimate graves had to be approved, in advance of burial, by the leader of the local patrol.Footnote 126 Members of dominant lineages, and their long-settled tenant farmers, had rights to local burial sites. Problems arose when strangers attempted to bury their dead in lineage territory. The interment of corpses or bones on land claimed by lineages was treated as a dangerous act—with serious, long-term consequences (including future claims to land or resources).

Unauthorized corpses discovered in Teng or Man territory were exhumed and dumped—without ceremony—into the sea.Footnote 127 Fisherpeople who frequented Laufaushan buried their dead in the hills of isolated (and uninhabited) islands in the delta.Footnote 128 Oyster specialists who worked in Laufaushan solved the problem by repatriating their dead for burial in their home district of Shajing, 25 miles to the north.Footnote 129 The delta has long been a dumping ground for unwanted, unclaimed, or inconvenient corpses. During the Communist land reform campaigns of the 1950s and the Cultural Revolution disruptions in the 1960s, dozens of corpses washed ashore along Laufaushan—a gruesome reminder of political upheavals only a few miles to the north.Footnote 130

The workers who made Laufaushan industries possible had no lasting memorials to commemorate their efforts or even their residence in the area. They were, by the standards of Teng farmers, “people without history.”Footnote 131 Fisherpeople, oyster specialists, salt workers, and reed gatherers left no written genealogies, no inscribed ancestor tablets, and no impressive ancestral halls adorned with stone inscriptions and signed paintings (all of which are on permanent display in Ha Tsuen and San Tin).Footnote 132

By contrast, members of landowning lineages sometimes confided (to this outsider) that they felt overburdened with history—so much, in fact, that the legacy of the past restricted their ability to adapt to changing circumstances in the late twentieth century. “We can't do anything without thinking of the ancestors,” said one Teng entrepreneur who was struggling to start a new business in 1978. “We have to plan for the future, but our history Footnote 133 cannot be forgotten. Look around [gesturing to the Teng ancestral hall]. It is everywhere.”

The End of a Social Order: Laufaushan Transformations

The social, economic, and political underpinnings of village social life have been completely transformed since my initial field investigations of the 1960s and 1970s. By the time I returned to the New Territories for a third round of fieldwork in the 1980s, the oyster beds, reed fields, lime smelteries, and brackish-water paddy systems had all ceased operation. The Laufaushan oyster beds had been hit by a series of pollution crises that effectively destroyed the industry for the next two decades.Footnote 134 Production rebounded somewhat in the 2010s, but traditional cultivation (in shoreline beds) has been largely replaced by floating barges that nurture oysters on ropes suspended in deep water. It is also significant that most of these oysters are not sold, or consumed, in Hong Kong.Footnote 135

Meanwhile the physical landscape of Ha Tsuen District (which includes the Laufaushan coastline) has been transformed by unplanned, chaotic development of the type sometimes referred to as “Desakota” sprawl; others have called it “despoliation.”Footnote 136 Paddy fields and vegetable plots have morphed into a haphazard collection of industrial sites, warehouses, lorry parks, and concrete platforms that store thousands of shipping containers for Hong Kong's busy freighter trade. In 2007, one such platform (with 800 rusty containers stacked six to eight high) arose two hundred yards from the entrance to Ha Tsuen's 350-year-old ancestral hall—a sight many Teng elders found particularly disturbing.Footnote 137

In the course of these disruptions, Hong Kong's newest “New Town” emerged three miles north of Ha Tsuen. Named for the brackish-water paddy system discussed earlier in this article, Tin Shui Wai arose in record time—eight years from start to finish.Footnote 138 Today its thirty- and forty-story apartment blocks house over 300,000 people—all but a tiny fraction of whom have no previous connection to the original inhabitants of the New Territories. Tin Shui Wai is a bedroom community served by a rapid transit system that shuttles residents to and from Hong Kong's major metropolitan center, 20 miles to the south.

Similar transformations have occurred in San Tin District, where one of the world's busiest border stations (Lok Ma Chau) was constructed on paddy fields that had sustained the Man lineage during the six previous centuries.Footnote 139 In 2015, over 28 million people passed through this checkpoint, most of whom departed on fast trains that rocket through the New Territories on their way to and from Kowloon.Footnote 140 Members of the Man lineage began emigrating in large numbers to Europe and Canada during the 1960s and 1970s; the descendants of these pioneer migrants constitute an international diaspora linked by social media and (increasingly infrequent) visits to San Tin.Footnote 141

Today, in the third decade of the twenty-first century, ecotourism and seafood dining are the dominant industries in Laufaushan.Footnote 142 The local scene is dominated by a gleaming, ultra-modern bridge that links the New Territories to new cities on the western shores of Deep Bay (the bridge looms high above the old fishing stations 12 and 13 on Map 4). Laufaushan's drying racks for salt fish and the dilapidated shacks of oyster workers are long gone. Nothing of the complex social past remains, save in the memories of a handful of aging villagers—and in the fieldnotes of a retired anthropologist.