Introduction

In 909, Zhang Chengfeng 張承奉 (r. 894–910, birth and death dates unclear) had been the military commissioner (jiedushi 節度使) of Dunhuang, an oasis town in northwestern China, for fifteen years.Footnote 1 His grandfather, Zhang Yichao 張議潮 (799–872), had toppled the Tibetan lords in 848 and established his family rule in Dunhuang. Zhang Yichao's nephew, son, and son-in-law succeeded him until, in 894, Zhang Chengfeng became the fifth military commissioner of this semi-independent state. In the waning years of the Tang dynasty (618–907), warlords such as the Zhangs governed much of the domain of the Tang beyond the two capitals.Footnote 2 The most powerful among them, such as Zhu Wen 朱温 (852–912), would vie for control of Central China in the post-Tang world. Stories about warlords in Central China fill the volumes of Histories of the Tang and Histories of the Five Dynasties. In comparison, the Dunhuang regime under Zhang Chengfeng ruled over merely two prefectures in the northwestern corner of what used to be the Central Asian frontier of the Tang empire. His deeds were largely ignored by contemporary warlords and forgotten by later historians. Exactly one line about him is preserved in the official annals, which mis-records his name as “Zhang Feng”:Footnote 3

In Shazhou (i.e. Dunhuang), during the Kaiping reign of the Liang dynasty, there was a military commissioner Zhang Feng who styled himself “White Clothed Son of Heaven of Golden Mountain.”

沙州,梁開平中,有節度使張奉,自號「金山白衣天子」。

Few could, or cared to, understand Zhang's enigmatic title “White Clothed Son of Heaven of Golden Mountain” until 1900, when Wang Yuanlu 王圓箓, a local Daoist monk in Dunhuang, stumbled upon a cave filled with medieval manuscripts. Sealed up in the early eleventh century, this collection of manuscripts sat undisturbed for almost nine centuries.Footnote 4 It is primarily a collection of Buddhist texts, but a significant number of official documents also made their way into the collection, primarily being used as paper to repair Buddhist texts. Among these documents are edicts, poems, petitions, and orders produced by the Dunhuang government. On the basis of these rich materials, scholars have successfully determined that, between 909 and 911, Zhang Chengfeng, an unremarkable successor in a small regional state, abandoned the title of military commissioner used by his ancestors, and proclaimed himself the Emperor (huangdi 皇帝) and Son of Heaven (tianzi 天子) of a new “Han” dynasty.Footnote 5 He was described as wearing white cloth, because in honoring the color white and its associated element of metal in the five-element theory, his state purportedly succeeded the Tang dynasty which honored the color yellow and the element of earth. This new state, according to the Dunhuang documents, was called “Golden Mountain Kingdom of Western Han” 西漢金山國.Footnote 6

Zhang Chengfeng's career as an “emperor” only lasted for about two years before he was forced to give up this title by a combined force of a military defeat by the Uyghur kingdom of Ganzhou to the east of Dunhuang and an internal revolt from Dunhuang's commoners. A few years later, Zhang was overthrown by a subordinate named Cao Yijin 曹議金 (r. 914–935), who initiated the Cao family rule of Dunhuang that lasted until 1035. Zhang's failed foray into emperorship is generally considered an insignificant, if also erratic, era in the history of Dunhuang. Scholarly work on this state significantly dwindled after the initial interest in clarification of dates of important events.Footnote 7 Aside from a few long poetic compositions made during this period, Zhang's endeavor seems to have, once again, stopped interesting historians.

In this article, I show that if we place Zhang's ambition and his Golden Mountain kingdom in the broader context of the post-Tang world, there is much to learn from its short history. Both the timing of Zhang's new state and his association with the color white indicate that this state-building project was a direct response to the fall of the Tang. In this way, what Zhang did is not too different from what a number of other states, such as the Former Shu (907–925), did immediately after the fall of the Tang. The Dunhuang response under Zhang is worth investigating because, unlike all other self-styled Tang successors, the documents about Zhang Chengfeng's new state are not preserved through the discriminating editorial works by historians of the Song dynasty, which was itself a rival for the Tang legacy. Therefore, the choices made, language used, and precedents sought by the emperor of the “Golden Mountain kingdom” allow us a contemporaneous view of the new political reality created by the fall of the Tang. The clarification of this new reality compels us to see the political history of the post-Tang world in a new light.

This article is in two parts. In the first part I describe the drama of Zhang's short-lived emperorship in three Acts. In Act I, I recount the history of the strained relation between the Tang court and Dunhuang prior to Zhang Chengfeng to provide context for Zhang's actions after the fall of the Tang. Then, I offer an analysis of the ideology of Zhang Chengfeng's new state, which shows that, while Zhang claimed to be an emperor, he also attempted to localize certain universal features of the Tang empire to fit the political reality in Dunhuang. In Act III, I trace an alternative vision popular among the “ten-thousand commoners” in Dunhuang that vehemently opposed Zhang Chengfeng's state-building project. This voice from the supposed commoners, rarely heard in state-sponsored histories, advocated a return to Dunhuang's earlier political status as a vassal to a state based in North China. Such a view was inherited by the Cao family rulers, and it ushered in a new era in the history of Dunhuang.

The second part of the article reflects on how the story of Zhang Chengfeng's brief emperorship can help us rethink the political history of China in the tenth century. I argue that the conventional framework of “Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms” is teleological and does not properly capture the challenges facing the political figures at the time. Every warlord in the post-Tang world faced a similar choice to that which so dramatically split Zhang Chengfeng and the commoners of Dunhuang: should one adhere to a hegemon in North China, whoever it may be, or should one find regional justifications for power? Analyzing the making of the post-Tang political regionalism in Dunhuang offers new ways of understanding this unique period of political division in the history of China.

The Emperor of Dunhuang: A Drama in Three Acts

Act I: Returning to A Foreign Country

In 848, Zhang Yichao, who was from a local noble family in Dunhuang, revolted against his Tibetan overlords, who had ruled the area for more than half a century. With the Tibetan empire crippled by internal strife, Zhang was able to drive out local Tibetan officials and expand his control beyond Dunhuang. A prompt decision of “return to Tang Empire” was made as he sent envoys to Chang'an, the Tang capital, in the same year as his rebellion.Footnote 8 Of this first dispatch of envoys, we unfortunately know little. In late 851, Zhang Yichao dispatched a more formal and better-documented group, headed by the renowned monk Wuzhen 悟真 (816–895), to Chang'an.Footnote 9 It was followed in July by Zhang Yitan 張議潭 (?–860), Zhang Yichao's older brother, who brought maps and household registrations of eleven prefectures of the Hexi region, many of which were under Zhang Yichao's rule. These acts were clear signs of the Zhangs’ wish for political reincorporation into the Tang.Footnote 10 In a poem written to the Tang court, Wuzhen expressed his gratitude for seeing the Emperor:Footnote 11

By reminding his audience in the capital that the Dunhuang people were “of the old days,” Wuzhen was clearly claiming Dunhuang's old status as a part of Tang. The use of ethnic terms such as lu (caitiffs) and yi (barbarians) also implies Dunhuang's unique status as a “Han” Chinese region in the far west. Zhang's seizure of power was thus presented as a renewal of Tang power, which should only naturally be recognized by the Tang court. This view, however, was not shared by everyone in Chang'an. Bianzhang 辯章, the head monk in Qianfu Monastery in Chang'an, commented that:

Wuzhen, the monk of Gua and Sha [Prefectures], was born among the western barbarians [xifan 西蕃] and came here to the noble state [i.e. Tang] … [The Emperor] asked the similarities and differences between the Great State [i.e. Tang] and the barbarian prefecture [rongzhou 戎州] on the law of the Buddha.Footnote 12

While xifan (western barbarians/Tibet in the west) might have meant Tibet (and not the generic “foreign”), as Wuzhen was indeed born when Dunhuang was under Tibetan rule, the “barbarian prefecture” points unmistakably to Dunhuang under Zhang Yichao. This attitude was in line with the position of the Tang court, which gave the new Dunhuang state the title of “military prefecture of returning to righteousness [guiyijun 歸義軍].” As seen in other contemporaneous cases, the term “returning to righteousness” was used exclusively for polities of non-Chinese ethnic background in the Tang dynasty. One branch of Uyghurs active not far from Dunhuang was given the same name: Guiyijun, after offering their allegiance to the Tang.Footnote 13 Evidently, unlike what the name might suggest at face value, it was usually a recognition of political inclusion and cultural exclusion.

The uneasiness of this first encounter colored the rest of the six decades of Dunhuang's relation with the Tang court. Although Zhang Yichao was given the title of “military commissioner” three years after his uprising, his relationship with the capital remained tense, with both parties keen on the control of Liangzhou, the key city of the Hexi region on Dunhuang's path to Chang'an.Footnote 14 In 867, after his brother, who was serving as a hostage to the Tang, died in Chang'an, Zhang Yichao himself was summoned as a replacement. Zhang Yichao had to oblige and left the rulership in Dunhuang to his nephew Zhang Huaishen (831–890), who ruled until being murdered with his wife and six sons in 890. Yet, only in 888, more than twenty years after his assumption of power, did the Tang court confer on Zhang Huaishen the title of military commissioner. In these two decades, numerous envoys made the difficult journey from Dunhuang to Chang'an to seek the appointment, and repeatedly, they encountered another denial.Footnote 15

The best documented of these trips occurred towards the end of these two decades.Footnote 16 Two Dunhuang officials named Zhang Wenche 張文徹 and Song Runying 宋閏盈 led the group that left Dunhuang in the twelfth month of the second year of the Guangqi 光啟 reign (886).Footnote 17 On the seventeenth day of the second month in the following year, they reached the temporary residence of the Tang emperor in Xingyuan 興元 (modern Hanzhong 漢中).Footnote 18 Three days later, the envoys had their first meeting with the ministers, who told them to wait for the emperor in Fengxiang. When they reached Fengxiang, they turned in six more petitions, on the ninth, the eleventh, the thirteenth, the seventeenth, the twentieth, and the twenty-third days of the third month (April 16, 18, 20, 24, 27, and 30 of 877 in Gregorian calendar), to no avail. The Dunhuang document that details this series of events, Stein 1156, breaks up after the petition on the twenty-third, leaving us wondering if more attempts were made. What we do know is that after all these efforts, the envoys were still unsuccessful in securing the title and had to return to Dunhuang empty-handed.

The ensuing desperation led to conflicts among the envoys. A group headed by Zhang Wenche had given up hope and proposed to join a regiment of traveling soldiers and return to Dunhuang immediately, whereas Song Runying insisted on staying and trying again. The complaint of Zhang Wenche and three others went so far as deriding Zhang Huaishen, the lord of Dunhuang himself: “what accomplishment did the puye have to ask for the insignia (of military commissioner)? In the past twenty years, how many minions have tried to come here (to ask for the insignia)? … If you (meaning Song Runying) can get the insignia, the four of us will walk with our heads!”Footnote 19 Song's faction, while recognizing the frustration that “after writing documents and sending people across the desert ten thousand times, nothing was achieved,” still expressed with great determination: “without the insignia, we will not return even if faced with death!”Footnote 20

Two years later, after yet another mission of envoys, the Tang court ultimately gave in and granted Zhang the title. When the Tang envoy conferring the title finally reached Dunhuang, he was given a tour in the area. This trip was so significant that it was recorded in the biographical bianwen (transformation text) written in honor of Zhang Huaishen.Footnote 21 According to this text,

after the Minister [shangshu 尚書, meaning Zhang Huaishen] accepted the decree, he directed the imperial envoy into the Kaiyuan Monastery to pay respect to the divine portrait of Emperor Xuanzong (685–762). The imperial envoy saw the earlier imperial throne, which resembled the one Emperor Xuanzong had used when he was alive. He [the Tang envoy] sighed: “though Dunhuang was blocked from Han for a hundred years, and was lost to western barbarians [rong], they still revered our dynasty and kept the image of the Emperor, which was lost in the other four prefectures [meaning Gan, Liang, Gua, and Su, all of which are in the Hexi corridor]. The walls of the cities in prefectures of Gan, Liang, Gua and Su were all destroyed. The residents lived with the ugly barbarians, and their clothes were all fastened on the left [zuoren]. Only the Sha prefecture [i.e. Dunhuang] shared the same people and culture with the Inner Land [neidi 內地].

尚書授敕已訖,即引天使入開元寺,親拜我玄宗聖容。天使睹往年御座,儼若生前。歎念燉煌雖百年阻漢,沒落西戎,尚敬本朝,餘留帝像。其於(餘) 四郡,悉莫能存。又見甘涼瓜肅,雉堞彫殘,居人與蕃醜齊肩,衣著 豈忘於左衽。獨有沙洲一郡,人物風華,一同內地。Footnote 22

The authenticity of the story is hard to confirm. If we are to believe the account of a memorial stele dedicated to Zhang Huaishen which claimed that Tibetans forced the people of Dunhuang to adopt Tibetan custom and clothing, an act Zhang's ancestors resented,Footnote 23 it is quite difficult to imagine that the Tibetan rulers would have allowed an image of the Tang Emperor to exist and be honored for some eighty years. Nevertheless, the story reveals that people in Dunhuang regarded their prefecture as the only place in Hexi area that preserved the political tradition (as represented by the image of the emperor) and cultural practice (i.e. the clothing) of China proper. A similar attitude is also visible in a number of lyric poems (quzici 曲子詞) recorded in Dunhuang manuscripts. One wished that Dunhuang would “eventually extinguish the barbarian [fan] wolves and they will together pay homage to the emperor.”Footnote 24 Another acknowledged the difficulties of the survival of the state: “Dunhuang is surrounded by six barbarian groups on four sides … it is afraid that, without the heavenly power from afar, the He-Huang area will eventually sink into the barbarians.”Footnote 25 A particular poem, titled “Paying the Loyalty,” went as far as saying that “when we eventually reach the Tang, and are able to bow to the divine noble emperor, there will be tears every step we walk and they will drench our clothes as we look at the red door of the palace. … For thousands of years we will pay our loyalty.”Footnote 26 Like the repeated efforts of envoys trying to acquire an appointment, this theme of “loyalty” in lyric poems was used to validate the status of Dunhuang as a legitimate member of the Tang political world.Footnote 27

Such was the relationship between Dunhuang and the Tang court before the fall of the Tang: on the one hand, the rulers of Dunhuang desired Tang recognition in order to substantiate their legitimacy; on the other hand, the Tang central government was cautious and even suspicious, and used the authority of conferring the title of military commissioner as a means to control this far-flung region. In order to accomplish this goal, the Tang court not only required high profile political hostages from Dunhuang, but also repeatedly rejected or postponed the Dunhuang government's request for the title of military commissioner. Contrary to the self-perception of Dunhuang, which regarded the Zhang family regime as a representation of Han Chinese civilization in the region, the people in the capital often saw Dunhuang as little different from the “barbarians” surrounding it. The zealous “return” in Dunhuang was met with indifference and hostility in Chang'an. Zhang Chengfeng inherited this relationship. His subsequent choices can only be understood with this background in mind.

Before Zhang Chengfeng became the military commissioner, a series of political upheavals occurred: the control of Dunhuang was seized by Suo Xun 索勛 (?–894) in 892, whose rule lasted for two years before he was defeated by Zhang Yichao's fourteenth daughter and her husband, whose family was surnamed Li. Zhang Chengfeng was then established as the nominal ruler of Dunhuang, but members of the Li family held sway. Only after another two years was his aunt able to restore the sovereignty fully to the hands of Zhang Chengfeng.Footnote 28

Such power grabbing, common among local warlords in late Tang, was the symptom of a structural problem. The legitimacy of the rule of any warlords derived, in theory, from the central government, and was therefore not supposed to be hereditary. Yet with few exceptions, local warlords desired transmission of power within their families in a hereditary fashion. This tension was temporarily resolved if the title of military commissioner could be automatically granted to the next ruler in line. But if the ruler was ruling without the appointment from the central government, he ran a greater risk of facing local opposition.Footnote 29 Such risk materialized in Dunhuang from 890 to 896, between the murder of Zhang Huaishen and the assumption of power of Zhang Chengfeng, with the rule of Dunhuang changing four times among three families. It took Zhang Chengfeng another four years to acquire the official Tang appointment. By this time, the aging empire had seven years of life left. When the demise of Tang finally came, Zhang Chengfeng was presented with a crisis, as his legitimacy to rule in theory came partly from the appointment by the Tang. He faced this crisis by proclaiming himself an emperor (huangdi 皇帝).

Act II: The Emperor of Dunhuang

On the first of June in 907, Zhu Wen, the most powerful warlord in North China and de facto ruler of the ailing Tang empire, finally ascended the throne as the new emperor. Several days later, he changed the reign name from Tianyou, “Protected by Heaven” to Kaiping, “Initiating Peace,” and announced the name of his new state: the Great Liang. The news of the official end of the Tang must have traveled quickly to Dunhuang, and in the following year, Zhang Chengfeng dispatched a diplomatic mission to the Liang state. After the return of this mission, Zhang Chengfeng, perhaps sensing the weakness of the new state in North China, decided to found his own independent state, two years after the fall of the Tang.Footnote 30

Zhang's new state was the result of a compromise between his universalist aspirations and the regional realities of Dunhuang. Such compromise can be seen in the name of the state, “the Golden Mountain Kingdom of Western Han” (Xi Han jinshanguo 西漢金山國) and the personal title Zhang adopted, “the Emperor of White Cloth of the Golden Mountain Kingdom” (Jinshan baiyidi 金山白衣帝). The elements of metal/gold and whiteness in the name of the kingdom and the emperor are clear indications of the relation between Zhang's new regime and the Tang Empire. According to the Five-Element Theory, the element befitting a ruler changes in patterned cycles.Footnote 31 The element of metal/gold succeeds that of earth; and in parallel the color of white succeeds that of yellow. Because earth and yellow were the element and color of the Tang, the element of metal/gold and color of white used in the political terminologies of the new empire in Dunhuang signify that Zhang Chengfeng had the objective not merely of breaking away from regimes in North China, but of achieving the status of a Tang emperor. Thus, he adopted the title of “emperor” (di) rather than the more modest “king” (wang). Similarly, the use of the state-name “Han” invoked another long-lasting dynasty based in North China, while at the same time signifying Dunhuang's unique ethnic self-identification among states in the region.Footnote 32 It is clear from these choices that Zhang was not satisfied with merely establishing a local kingdom, but modeled his new state after such juggernauts as the Han and the Tang empires.

At the same time, these names also show Zhang's awareness that his state was not quite like the Han or the Tang. The addition of the ambiguous epithet of “Golden Mountain” to both the state-names and the title of the “emperor” might point to the regional nature of his new state.Footnote 33 Such regional nature is unambiguously revealed by the added “west” to the name of the state. In this respect, one might be tempted to compare Dunhuang (=Western Han) with the Southern Han and Northern Han among the “Ten Kingdoms.” But it is crucial to point out that, the directional adjectives in the “Southern” Han and the “Northern” Han were later added by historians for the dual purposes of distinction and denigration. When these states were established, their proper state-name was simply “Han.”Footnote 34 In contrast, in documents and texts composed in Dunhuang, we can see that the “western Han” was the officially adopted state name.Footnote 35 The regional nature of the state was evident for the composers, users, and readers of these documents in Dunhuang.

The dynamics between universalism and regionalism are clearly revealed in two long panegyric poems composed during the short life of the “Golden Mountain Kingdom.” The first poem, The Song of the White Sparrow 白雀歌, was written on the occasion of the sighting of a white sparrow, an auspicious sign of the founding of a new state.Footnote 36 As historian Yu Xin has pointed out, Zhang Chengfeng wished to inherit two political traditions through extolling the sighting of the white sparrow. At the founding of the Tang dynasty, white sparrows appeared as omens for Li Yuan (566–635) to claim the title of emperor.Footnote 37 Locally, another significant precedent is also well known: the Illustrated Geography of Shazhou (Dunhuang), in an entry on auspicious omens, cites a historical text, The Account of the Western Liang, about the appearance of white sparrow at the court of Li Hao 李暠 (351–417), the founder of the Western Liang dynasty (400–421).Footnote 38 Under Li Hao's rule, Dunhuang became the capital of a regional state for the first time in its history.Footnote 39 Therefore, the choice of white sparrow as the representative omen for the new state betrays a dual ambition in line with the name of the state and the Zhang's imperial title. He wished to assume the status of the emperor while maintaining a distinctive local identity that was rooted in the Hexi region and not, like the Tang or the Han dynasties, in traditional centers of imperial power in North China such as Chang'an and Luoyang.

This theme of regionalism is central to the Song of the White Sparrow. In the preface, the author, a “fisherman from the land of Three Chu” named Zhang Yong, recounts the genesis of this new state:Footnote 40

His Highness the Son of Heaven of Golden Mountain Kingdom, from above he received the mysterious emblem and obtained the book (of mandate) of Heaven and Earth; from below he accorded with the wish of the people, and facing south he became the Lord. He will continue the restoration of the Five Liangs, and occupy the great places of the eight prefectures.

金山天子殿下,上稟虛符,特受玄黃之冊;下副人望,而南面為君。繼五涼之中興,擁八州之勝地。

The use of the term “restoration” (zhongxing) in this poem directs us to the source of legitimacy of Zhang's fledging empire.Footnote 41 Unlike his ancestors who tied the rationale of their state to the recognition of the Tang court, Zhang Chengfeng traced an alternative history that he could “restore.” What he found were the five kingdoms, all bearing the state-name Liang–Former Liang (320–376), Later Liang (386–403), Southern Liang (397–414), Western Liang (400–421), and Northern Liang (397–439)–that ruled parts of the Hexi region in the fourth and fifth centuries. This may seem an odd choice, because in the familiar stories of Chinese history these regimes are often given limited attention, if not simply ignored. In a recent history of the Northern and Southern dynasties, Mark Edward Lewis spared exactly one sentence on these states: “equally stable in nomenclature [to the various Yan states in northeastern China] but of little political consequence was the Gansu corridor in the far northwest that initially survived as a Jin province and was ruled sequentially by five mixed Chinese-barbarian states all called Liang (Former, Later, Southern, Western, and Northern).”Footnote 42 Contrary to this assessment, the memory of “Five Liangs” was not inconsequential in the region they ruled, and can be found in many different places in documents from Dunhuang.Footnote 43

The Song goes on to connect Zhang Chengfeng with the mystic Emperor Yao (堯) and Emperor Wen (wenwang 文王) of the Zhou dynasty. The verse section of the song includes a long and lavish description of the auspicious color “white” and the element of “metal/gold,” making reference to “white” sixty-two times and “metal/gold” nine times. Particularly interesting is a sentence toward the end of the poem: “white is the best of all five colors; how could one know this without our king [i.e. Zhang Chengfeng]?” Here, the poet tacitly acknowledges that Zhang's claim of replacing the Tang was a recent development: the color of white was elevated to the newly revered status because of Zhang Chengfeng's state-building policies.

Following this claim of history was an irredentist claim of land. The state of Dunhuang at this time controlled the equivalent of two Tang prefectures: Guazhou and Shazhou. But according to the Song, it aspired to “occupy the great places of the eight prefectures.” While it is unclear which specific prefectures the Song refers to, this new aspiration likely mirrored the area controlled by the five Liang states: from Liangzhou in the east to eastern Central Asia in the west. Nor did this aspiration remain a pipe dream: The first step Zhang Chengfeng took after enthronement was to attack Loulan in eastern Central Asia. The Loulan kingdom famed in Han dynasties was long buried in sands; what was left of Loulan in early tenth century were loosely structured polities that posed limited military threat.Footnote 44 The purpose of this attack was partially also to resume the connection with Khotan further to the west.Footnote 45 Zhang's successful campaign in Loulan boded well, it seemed, for his state-building project.

The claim of land also extended to the east. In another panegyric poem the Song of the Divine Sword of the Dragon Fountain (Longquan shenjian ge 龍泉神劍歌), the poet, a “great Prime Minister” (da zaixiang 大宰相) with the surname Zhang, proposed that the new emperor “destroy Gan prefecture and occupy the land of the Five Liangs.” The campaign against the Uyghurs, who occupied the Gan prefecture immediate to the east of Dunhuang, was the second step toward restoring the land of the Five Liangs.Footnote 46 With the demise of Tang, the shared ties Dunhuang had with the Uyghur kingdom of Ganzhou as Tang vassals also disappeared, and this severance of ties gave the ruler of Dunhuang justification for invasion. In order to achieve this irredentist objective, Zhang Chengfeng opted for cooperating with the remnants of Tibetan forces, the long-term enemy of the Tang, in order to attack the Uyghurs in Gan prefecture. This campaign, however, proved disastrous for Zhang. In 911, only two years after Zhang's founding of the new regime, he found the city of Dunhuang surrounded by the counterattacking Uyghur army.

The battle of the city of Dunhuang with the Uyghurs is the best-known moment in the history of the Golden Mountain kingdom, thanks to a single manuscript in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Pelliot chinois 3633. On the verso side of this manuscript one finds the Song of the Divine Sword of the Dragon Fountain.Footnote 47 This panegyric poem was written after the Uyghur army reacted with a forceful march against Dunhuang. The “Sword of the Dragon Fountain” was a famed weapon from age immemorial.Footnote 48 This poem begins with a reference to this sword, seen as a sign of royal power.Footnote 49 Many couplets follow in praising the great virtues of Zhang Chengfeng as comparable to that of the mythical emperors of Yao 堯 and Shun 舜. Then it turns to military promise: “the newly sharpened sword must be used; it is not too late to set the border and expand the domain” (神劍新磨須使用,定疆廣宇未為遲).

What exactly was this domain that the new emperor planned to control? The following verses give an outline:

To the east (we will) take He (prefecture), Lan (prefecture) [both places are in eastern Gansu], and Guangwu city; to the west (we will) take Tianshan (garrison) and Hanhai (garrison) [both places are in modern Turfan]; to the north (we will) control Yanran (western Mongolia) and … ling (Congling?) garrison; to the south (we will) reach Rong and Qiang and Lhasa will be conquered.

東取河蘭廣武城,西取天山澣海軍。北掃燕然□嶺鎮,南盡戎羌邏莎平

This domain covers a vast region from eastern Gansu to Turfan, from Lhasa to Mongolia, greatly exceeding the land controlled by the Liang states. Importantly, it does not include the usual core area of Chinese Empires in north China, but orbits around the center that is Dunhuang.

Then Prime Minister Zhang, the poet, explains that the envoy to Tibet was sent “to establish a marriage in order to extend [the reign of] the state.” This explanation is necessary because the foundation of the Zhang family rule in Dunhuang was the banishment of the Tibetan rulers. He then offers an account of the ongoing battle, where the martial skills of many generals of Zhang are extolled and seen as indispensable for the future military success over the Uyghurs. After telling the story of the actual event, the poem goes on to outline a broader plan for the newly founded state of Zhang Huaishen:Footnote 50

This plan consists of two parts. First, the wish to pass the Golden Mountain kingdom on to his descendants reflects Zhang's desire for a stable, hereditary rule. This desire was a central concern for late-Tang warlords like Zhang Chengfeng's father and grandfather. The relentless effort to get the Tang to grant titles to the lord of Dunhuang was a central part of these lords’ bid to maintain hereditary rule. Zhang Chengfeng himself was the victim of the failure of such efforts when the local strongman Suo Xun usurped the role of military commissioner following the death of his father Zhang Huaiding. The long battle to win back the lordship of Dunhuang must have convinced Zhang Chengfeng of the importance of establishing a secure, hereditary position for the Zhang family. This wish could have been the main reason for Zhang to establish a new state in the first place because, in an imperial state, the rule of one family was the presumed rule rather than the result of incessant courting of a distant emperor.

Second, it is clear from these lines that the full ritual apparatus of a new empire had not yet been properly established. At the moment of writing, a new reign name had not been chosen, and the ritual protocol of sacrifice to Heaven in the southern suburb had not been performed. Nonetheless, the poem promises that these steps will be taken in the near future, and Dunhuang will be properly established as the new capital. The irredentist ambition set out in the Song of the Divine Sword is broadly in line with the localized history claimed in the Song of the White Sparrow in the sense that this ambition, however grandiose, still centered around Dunhuang. Just as no claim to the history of Han and Tang were made in the Song of the White Sparrow, no land in the traditional center of Chinese empires seemed to have interested Zhang and his officials in the Song of the Divine Sword. What they were planning to build was a distinctively regional polity.

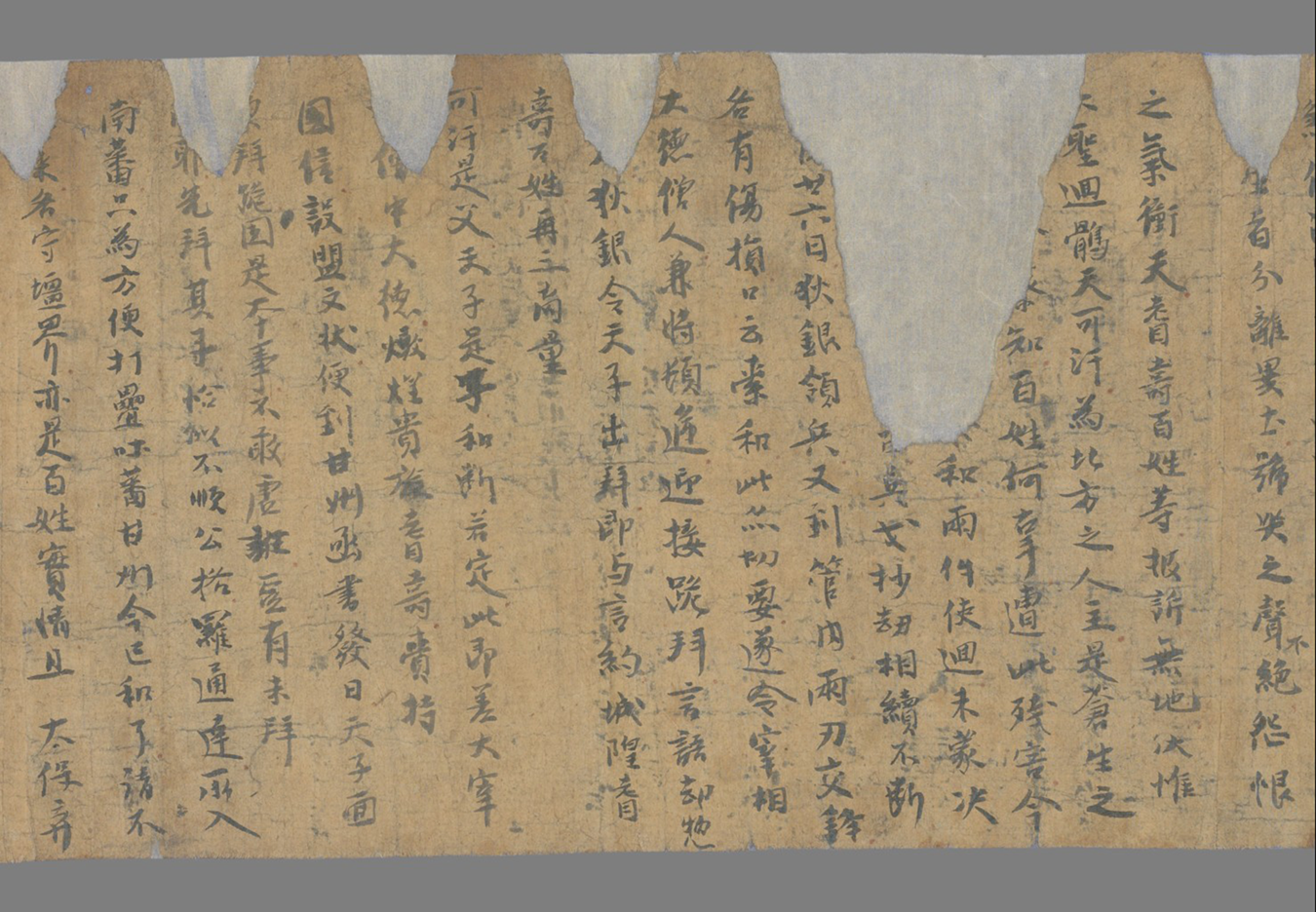

Lest we think all these were just empty promises, Zhang's state building effort is revealed concretely in his governmental documents. As a standard in the founding of a new regime, the ranks of officials were generally changed. Figure 1 is a royal decree from Zhang Chengfeng, known by the title of shengwen shenwu baidi (White Emperor of Sagely Talent and Divine Valour). This document is the office-certificate (gaoshen 告身) of a certain official named Song Sixin on the occasion of a promotion.Footnote 51 There are two aspects in this promotion. The rank of Song Sixin was promoted from Unofficial Commander (san-bingmashi 散兵馬使) to General (yaya 押衙),Footnote 52 while his actual appointment remained the same: “in charge of affairs of guests” (zhikeshi 知客事). But more importantly, an additional title Minister of the Court of State Ceremonial (honglu qing 鴻臚卿) was given to him. Adding the new title did not alter the nature of Song's appointment—the Minister of the Court of State Ceremonial in the Tang was in charge of managing visiting envoys—but it changed his office from a local to an imperial one. Additionally, the strict use of imperial formatting, including the raising of the imperial title, the repeated use of the imperial seal (which reads jinshan baiyi wang zhiyin “The Seal of the White-Clothed King of the Golden Mountain [Kingdom]”), and the royal signature chi 勑 (which presumably is the only part of the document actually written by the emperor himself) are all evidence for the official adoption of an imperial pretension. As is visible from this decree, even though the vision of this new state was limited to a certain locality, almost all other aspects of political actions taken by Zhang Chengfeng adhered to the standard practices of a Chinese emperor.

Figure 1. A Decree from the Emperor of the Golden Mountain Kingdom of Western Han. Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

This prospect of a new state also acquired acknowledgement by the general public to a certain degree. In a certain zhaiwen 斋文 (Buddhist text performed in ritual assemblies), it is stated, “the predicted longevity is eight hundred years and the jeweled reign will constantly prosper; the life of His Holiness will be one thousand autumns and the Western Han will forever be honored.”Footnote 53 However, instead of lasting for one thousand years, this grand plan failed within two, when the superior Uyghur army swiftly defeated that of Zhang Chengfeng.Footnote 54 The discrepancy in military strength was the main reason for the end of Zhang's whimsical plan of restoring the land of the Five Liang, but as I will show in the next section, domestic dissent regarding the political vision of Dunhuang also contributed to his swift failure.

Despite his ultimate failure, Zhang Chengfeng built his new state with a clear vision. In nomenclature, it differed little from the Tang empire itself. The short life of the new state did not allow Zhang to follow through with all the steps toward building a new “imperial” regime, including the adoption of a new reign name, the construction of a new capital, and the ritual sacrifice to Heaven; but these steps were being planned. At the same time, his regime was also clearly regional in that he did not seek to take over the geographical core of the Han and the Tang empires. Instead, Zhang sought, and found, a local precedent–the Five Liang states–in the last period of political fragmentation after the fall of the Han. Although Zhang's geographical ambition far exceeded the land controlled by all five Liang states combined, it resembled the Liang precedents in having its center in the Hexi region. Unfortunately for Zhang, his state-building project that combined imperial nomenclature with a regional outlook was to be fatally challenged both without and within.

Act III: The Commoners Strike Back

On the recto side of the Song of the Divine Sword of the Dragon Fountain one finds a document named “a petition by the ten thousand fan and han commoners (baixing) of Shazhou submitted to the Great Divine Heavenly Khaghan of Uyghur,” written in the seventh month of the year 911.Footnote 55 This document offers a drastically different view of the Uyghur invasion, the Tibetan connection, and the general political inclination of the Golden Mountain Kingdom. The nominal petitioners were not any individuals, but “ten thousand fan and han commoners (baixing) of Sha Prefecture [i.e. Dunhuang].” It begins with a recounting of the history of Dunhuang:

Shazhou used to be a prefecture of The Great Tang. Previously during the era of Tianbao, An Lushan rebelled and the region of Hexi was conquered as a result. For more than one hundred years, the Tibetans governed nominally, until the second year of the Dazhong era [848], when our military commissioner Taibao [i.e. Zhang Yichao], arising from a first-rank family in Dunhuang, expelled the Tibetans and restored the land again.Footnote 56 It has been more than seventy years since then, and the tribute has never been stopped. Taibao, after his success and accomplishment, returned to the Tang bearing the insignia [節]. He was offered higher titles and given access to the royal court. Exceedingly great was the favor he received. Later, he fell ill and passed away in the land of the emperor. His sons and grandsons thereafter guarded the western gate [of the empire] until now. In the meantime, the Heavenly Khaghan dwelled in Zhangye and (we both) served the same family [i.e. the Tang] without a second thought. The eastern road was opened and the Heavenly envoys were never stopped. This was because of the power of the Khaghan. The commoners are appreciative of this and are not unaware of it.

沙州本是大唐州郡。去天寶年中,安祿山作亂。河西一道,因茲陷沒;一百餘年,名管蕃中。至大中二年,本使太保,起燉煌甲□,□卻吐蕃,再有收復。爾來七十餘年,朝貢不斷。太保功成事遂,仗節歸唐。累拜高官,出入殿庭,承恩至重。後□染疾,帝里身薨。子孫便鎮西門,已至今□。中間遇天可汗居住張掖,事同一家,更無貳心。東路開通,天使不絕,此則可汗威力所置,百姓□甚感荷,不是不知。

As discussed above, Zhang Chengfeng's view of the history involved the inheritance of the legacy of the Five Liang states; and Zhang Yichao, the founder of the Zhang family rule in Dunhuang, was conspicuously absent in Zhang Chengfeng's version of Dunhuang history revealed in the panegyric poems. The history in the Petition is different in a number of ways. The origin of the Zhang family rule is presented as an integral part of the Tang. Taibao, an honorific title used exclusively for Zhang Yichao, is praised for defeating the Tibetans and “recovering” Dunhuang, and his trip to Chang'an and eventual death there is seen as “returning” to the court of the emperor, the Tang emperor. The tremendous honor Zhang Yichao received at the Tang court ensured, according to this version of Dunhuang history, the rule of his descendants in Dunhuang. The Uyghur Khaghan, a former ally of the Tang, is regarded as a part of this power structure, serving the Tang and maintaining the connection Dunhuang had with China proper. In this rosy retelling of the relation between Dunhuang and the Tang, disagreements and hostilities regarding the control of Liangzhou and the authorization as the military commissioner are conveniently overlooked. The implication of this alternative version of history is clear: since both Dunhuang and the Uyghurs in Gan Prefecture had served a Central China regime in a peaceful manner in the recent past, there was no reason this type of relation could not be restored.

The petition then turns to more recent events, when “the two places [Dunhuang and Uyghur-controlled Ganzhou] were caused by someone to fight and mutual hatred arose” (兩地被人斗合,彼此各起仇心). Here, the wording is intriguingly ambiguous, because the “someone,” whether an individual or a group, is not specified. As mentioned in the previous section, the decision to invade the Uyghurs was made by none other than the new emperor Zhang Chengfeng and was praised by his officials; this line could thus be read as a subtle condemnation of Zhang's behavior. Then the plight of the commoners is invoked with a request for the Uyghur Khaghan to stop the senseless violence, after which the petition moves to the immediate present. Diyin, the son of the Uyghur Khaghan, led an army to Dunhuang, and fierce fighting ensued in which both sides were severely damaged. The result was that a truce was negotiated:

Diyin requested that the Son of Heaven come out and bow on his knees, and then he would agree to a covenant. Elders and commoners of Chenghuang repeatedly discussed: the Khaghan is the father, the Son of Heaven is the son; if a peace agreement is reached, we will dispatch the Prime Minister, the Great Virtuous among the monks, as well as nobles and elders of Dunhuang, bearing the National Seal and the document for a covenant, to Ganzhou. When the letter was issued, the Son of Heaven knelt down and bowed towards the East. This is only reasonable, and we dare not be dishonest. How can we bow down to the son before we bow down to the father?

狄銀令天子出拜,即與言約。城隍耆壽百姓,再三商量:可汗是父,天子是子,和斷若定,此即差大宰相、僧中大德、燉煌貴族、耆壽、賫持國信,設盟文狀,便到甘州。函書發日,天子面東拜跪,固是本事,不敢虛誑。豈有未拜其耶,先拜其子?

This truce was an unequal one. To achieve a ceasefire, Diyin requested that Zhang Chengfeng acknowledge the Uyghur Khaghan as his father. His request was agreed upon, not by Zhang Chengfeng, but by the “elders and commoners.” These townspeople further promised that envoys would be sent to Ganzhou to complete the agreement, on which occasion “the Son of Heaven knelt down and bowed towards the East.” Even though Zhang Chengfeng was still referred to in this document as “Son of Heaven” (tianzi 天子), his prestige was unmistakably impaired to the point that the lofty title almost sounds like a mockery.

This damage to his status can be observed in the formatting of the document as well. According to the Tang code, in writing official documents, a special format called pingque 平闕 is to be observed in order to grant honor to specific terms and names. Twenty terms including “Emperor 皇帝” and “Son of Heaven 天子” belonged to the ping (short for pingchu 平出) category, meaning that the scribe should begin a new line whenever these terms were encountered. A second group of slightly less prestigious terms receive the treatment of que, meaning that a blank space is to be placed in front of them.Footnote 57 Our petition observed this regulation, but in an idiosyncratic manner (See Table 1).

Table 1. Scribal Honors in petitions from ten thousand commoners

Except for one case, where it received the que treatment, all other seven occurrences (the appearance as an addressee in line 2 should not be counted) of the title of the Uyghur leader: Khaghan (kehan 可汗) were written with the ping treatment. Similarly treated is the term for father (a-ye 阿耶 < 阿爺) which refers to the Uyghur Khaghan. The five occurrences of Taibao, the title of Zhang Yichao, all were treated with the honor que, and other terms related to the Tang dynasty, such as “Tang” “Court” (殿庭), “Imperial Land” (帝里), were also ascribed special treatment. In stark contrast, “Son of Heaven,” the title of Zhang Chengfeng, was given the lower que treatment twice; in three other occurrences, this term did not enjoy any scribal honor. In the central line of the agreement: “Khaghan is the father, Son of Heaven is the son,” Khaghan received the ping treatment, while “Son of Heaven” received none at all (See Figure 2, top of line 10 and line 12). By making these scribal choices, the scribe of the text, likely an official in Dunhuang, ascribed honorable status to the Uyghur Khaghan, the Tang, and Zhang Yichao, all of which were elements Zhang Chengfeng had intended to exclude or overwhelm in his imperial project. In this sense, the scribal honors and dishonors aligned closely with the content of the text in their disagreement with Zhang Chengfeng's vision and their wish to return to the type of inter-state relations established during the late Tang dynasty by Zhang Yichao.

Figure 2. Petition of the Ten Thousand Commoners, Line 22 to 33. Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The rest of the petition centers on one particular incident, Dunhuang's envoy to Tibet for military assistance against the Uyghurs. As mentioned above, Zhang Chengfeng regarded the alliance with the Tibetan power to be an important aspect in securing the longevity of his new state. The “elders and commoners,” on the other hand, had an entirely different view. They observed that “the Heavenly Khaghan lived in Zhangye [張掖] and served the same family [with us] without second thought. It was under the powerful establishment of the Khaghan that the eastern route was opened and imperial envoys were able to come incessantly. The commoners were grateful and were not unaware of that.” Here, the goal was to return to the established pattern of Tang times when both Dunhuang and the Uyghur kingdom in Gan Prefecture nominally served the lord in China proper. The real mutual enemy was said to be and always to have been the Tibetans. Along this line of argument, Zhang Chengfeng's decision to cooperate with the Tibetans was made, according to the “elders and commoners,” because “the Son of Heaven acted anxiously on his impulse, and the commoners all did not agree with that” (天子一時間懆々發心,百姓都來未肯). Here, the writer of the petition expressed more than subtle disapproval; the intense disdain for the “Son of Heaven” is all too evident.

It is rare to see a petition sent not by an individual, but by a group of people. The sensitive nature of the message might have contributed to such an omission. Of course, the ten thousand commoners could not have all participated in writing this rebellious (to Zhang Chengfeng) letter. Fortunately, there is evidence for an educated guess as to the authorship. Stein 4276 (now in the British Library) contains a petition written by An Huaide, a high official of Guiyijun, together with “monks, laymen, officials of the province, as well as elders, the ten tribes of Mthong-kyab and Tuihun [Tuyuhun], soldiers of the three armies, and ten thousand Fan and Han commoners of the two prefectures and six garrisons.”Footnote 58 Only the beginning of this letter is preserved, and it agrees to a remarkable extent with the first part of the Petition—to the degree that historian Zheng Binglin regarded it as a draft of the Petition.Footnote 59 If this is the case, then writing in the name of “ten thousand commoners” was the official An Huaide. It is significant that in this letter written during the era of “Golden Mountain Kingdom,” An Huaide's title begins with Guiyijun, the official name of Dunhuang before the creation of Zhang Chengfeng's new regime. In using this title, An Huaide revealed an inclination in line with what was actually described in the body of the letter. He did not recognize Zhang Chengfeng's empire and wished for the restoration of the pre-imperial status of Dunhuang as a vassal state to North China regimes.

Details about the exact outcome of this truce are unknown. What is known is that a treaty seemed to indeed have been established between Dunhuang and the Uyghurs, and the city did not fall under Uyghur rule. During the last days of Zhang's rule, due to his military defeat and mass opposition, he had to make concessions regarding his imperial project: the name of his new state was changed to the Dunhuang kingdom of Western Han (Xi Han Dunhuang guo 西漢敦煌國), and he himself was relegated from “Son of Heaven” and emperor to a “king” (wang 王). While Dunhuang retained the title of Han, the geographical limitation was a decided setback to the region.Footnote 60 But even such demotion was not enough to save the Zhang family rule. Three years later, Zhang Chengfeng was replaced by Cao Yijin (?–935).Footnote 61 While the exact process of this transfer of power is not documented, it is clear that the vision of the “ten thousand commoners” prevailed. This vision was adopted by the new rulers of the Cao family, who resumed ties with the central Chinese regime, maintained the fictive blood-relations with the Uyghur kingdom, and forfeited any imperial pretense in domestic politics.Footnote 62 This principle would be more or less maintained by later Cao rulers, who would control Dunhuang for another century.

As Zhang Chengfeng's imperial project was reversed, the version of the history of Dunhuang he promoted was also repressed and forgotten. In a local history titled “A Chronicle of the Important Events of Gua and Sha Prefectures” composed well into the Cao family rule of Dunhuang, a local official Yang Dongqian 楊洞芊 recounts the history of Dunhuang. In the preface, Yang states that the scope of his chronicle is limited: “Not mentioning other places, I will only discuss Gua and Sha Prefectures.”Footnote 63 The limited coverage of this local history aligns well with the actual domain under the control of the Dunhuang state, in drastic contrast to Zhang Chengfeng's geographical vision. The history of Dunhuang presented in Yang's account starts with the Han dynasty, when Dunhuang was first incorporated into a North China based imperial state. It then moves on to the Jin, and the Wei, the Northern Zhou, the Sui, and the Tang dynasty, and ends just before the An Lushan Rebellion. Conspicuously absent is the period of Five Liang dynasties, the source of so much of Zhang's ambition. To Yang, there was clearly no lesson worth learning from the history of these regional states. In both its geographical coverage and chronological selections, this version of the history of Dunhuang represents a thorough rejection of Zhang Chengfeng's imperial vision.

From the view of the “ten thousand fan and han commoners” expressed in the Petition, to the policy of the Cao rulers, and to the history recounted by Yan Dongqian, a vision of Dunhuang history and its political status emerged that differed drastically from those promoted by Zhang Chengfeng. In this alternative vision, Dunhuang should not become the center of a regional “empire,” but should continue to adhere to a lower status that connected it to a North China regime; The important periods in the history of Dunhuang were those when Dunhuang was either directly under the rule of a North China regime such as the Han and the early Tang or maintained a strong connection with them. Zhang Chengfeng's locally rooted imperial project was resolutely abandoned.

Putting Dunhuang back into “Chinese” History

More than one hundred years after their discovery in 1900, few would deny the importance of Dunhuang materials, whether in the form of manuscripts or mural paintings, to the study of medieval China. The materials from Dunhuang have provided crucial, and often unique, examples for the study of literature, language, religion, and art history.Footnote 64 Yet, in the field of political history, Dunhuang materials seem to have had little impact. Many excellent works exist on the political history of Dunhuang, but they are viewed as either having only local significance, or as relevant to the broader narratives of Chinese history only in the seventh and eighth centuries, when it was under the direct rule of the Tang dynasty. Even though the majority of secular documents from Dunhuang date to after the Tang retreat from Dunhuang in the ninth and tenth centuries, these materials seem to have contributed little to our understanding of Chinese history in these two centuries. For instance, the volume on the political history of the Five Dynasties and the Song in the Cambridge History of China, makes no mention in more than 1000 pages of the materials from Dunhuang.

The exclusion is a result of the historical project of the Song dynasty. In Song historiography, the tenth century is known as the “Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms 五代十國 (907–960).”Footnote 65 This term implies a tripartite typology of states in the tenth century: “the five dynasties,” “ten kingdoms,” and other unnamed, foreign states. Such division was not random. The “Five Dynasties” were seen as the legitimate line of transmission of the mandate, because the Song was essentially their heir state; the “Ten kingdoms” were grouped together and distinguished from the “Five Dynasties” because they were located in regions eventually conquered by the Song. Any state that did not participate in the eventual rise of the Song was downgraded to the background of the historical record or left out altogether. Dunhuang, for example, was put into the monograph on the “Four Barbarians” in Ouyang Xiu's New History of the Five Dynasties (Xin Wudai shi), despite the manifested Han cultural identity of the rulers of Dunhuang.Footnote 66 The historiography of the inevitable Song victory is thus embedded in the typology of “Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms.”

This typology has been questioned and revised in a number of ways: Johannes Kurz has explained that the creation of this idea was a complex process, exposing the constructed nature of this typology.Footnote 67 Liu Pujiang has pointed out the singularly low status of the Later Liang among Song historians, with the notable exception of Ouyang Xiu.Footnote 68 The Song volume of the Cambridge History of China exhibits an apparently minor but consequential revision of this typology: the chapter on “Southern Kingdoms” covers nine of the “Ten Kingdoms” and leaves out the only Northern one: the Northern Han.Footnote 69 This small change means that the standard of categorizing the tenth-century states in the Cambridge History shifted from a division between “dynasty” and “kingdom” according to their perceived importance and their relations to the Song, to a more purely geographical division between north and the south. Hugh Clark, in his work on Fujian and Southern China, has proposed the idea of a Tang-Song interregnum in the tenth century.Footnote 70 Compared to the “Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms,” the “Tang-Song interregnum” is a subtler concept that allows for geographical flexibility not retrospectively imposed by Song historians. But these two ways of viewing the tenth century are similar in that they both include the victory of the Song as the terminus. In this sense, these revisionist approaches to the political history of tenth-century China still do not allow the inclusion of Dunhuang and the broader Inner Asian world into their narratives.

The discussion above shows that, even though Dunhuang was placed in the category of foreign country by Song historians and generally excluded from most modern historians’ narratives of Chinese history, Zhang Chengfeng certainly considered his empire not as a “foreign” one, but quite literally as a “Han” kingdom, and an heir to the Tang. If we compare Dunhuang to many of the contemporary, post-Tang states, the similarities are apparent.Footnote 71 In Sichuan, for instance, Wang Jian (847–918) also declared himself an emperor, but maintained a state that was decidedly rooted in the Sichuan region with no northern territorial ambitions.Footnote 72 In Guangdong, Liu Yan (889–942), descendent of a regional military commissioner just like Zhang Chengfeng, not only claimed the title of emperor, but also used “Han” as the name of his state.Footnote 73 In both Dunhuang and the Southern Han, local lords decided to assume emperorship when their envoys reported the weakness of the Later Liang dynasty. The Southern Han Emperor's question that “now that the Central Country (zhongguo) is chaotic, who can claim to be the Son of Heaven? How can I traverse ten thousand li just to serve an illegitimate court?” would presumably have been in Zhang Chengfeng's mind as well.Footnote 74 Even the White Sparrow, the potent symbol of Zhang's new political aspiration, also appeared as an auspicious omen in the court of Wang Jian, and was likely also seen as a sign of a new, regional state.Footnote 75

The similarities among these post-Tang projects of political regionalism are most evident in their use of history. Many regional rulers sought historical precedents in the last period of political fragmentation after the fall of the Han dynasty. The clearest case is, again, the Shu state established by Wang Jian. On several occasions, Wang Jian invoked the precedent of the Shu Kingdom (221–263) in the Three Kingdoms period and compared himself to Liu Bei (163–223). The establishment of the state was based on a suggestion to “follow the precedent of Liu Bei 行劉備故事.”Footnote 76 In the edict Wang Jian issued upon enthronement, he further pronounced this connection by claiming “to use [the name of] Shu just as at the time of the Zhangwu reign [of Liu Bei]” (謂蜀都同章武之時).Footnote 77 Indeed, the lesson from the kingdom of Shu seems to have affected actual policy. In an edict issued in 910 that was designed to encourage agriculture, Wang Jian began by invoking the actual deeds of Liu Bei: “previously when the former Liu emperor entered Shu, Lord Wu (Zhuge Liang, 181–234) persuaded him to close the border and nourish the people. Ten years later, [they] launched a military campaign that rocked the Guanzhong region” (昔劉先主入蜀,武侯勸其閉關息民,十年而後,舉兵震搖關內).Footnote 78 The fact that Zhuge Liang's military campaign eventually failed was conveniently ignored. This view was even adopted by Zhu Wen. In a letter to Wang Jian, Zhu suggested that they “Learn from the previous practices between Cao Cao (155–220) and Liu Bei, each state having its own lord and officials.”Footnote 79 In his response letter, Wang Jian echoed this sentiment by claiming that “after the chaos of the Eastern Han, the Three Kingdoms all prospered.”Footnote 80 The regional states in the Three Kingdoms period provided Wang Jian a historical model of regionalism in much the same way that the Five Liangs did for Zhang Chengfeng.

Similarly, the ruler of the Wuyue kingdom was compared to the Wu kingdom in the Three Kingdoms Period. In a letter from the Tang emperor Zhangzong (867–904) to Qian Liu (852–932), the founder of the Wuyue kingdom, the emperor invoked the case of Sun Quan's loyalty to the Han dynasty in a state of crisis.Footnote 81 After the fall of the Tang, Qian Liu again compared himself to Sun Quan (182–252), this time deciding to follow Sun's example of political flexibility and accepting Zhu Wen's status as Sun had accepted that of Cao Pi (187–226).Footnote 82 Cao Pi and other figures of the Period of Division (220–589) served as precedents for the kingdom of the Southern Han, albeit in a less straightforward manner. In the epitaph for Liu Yan (889–942), he was praised as having the literary talents of Cao Pi and Xiao Ze (440–493), the emperor of the Southern Qi dynasty; Liu's military endeavors were praised as similar to those of the legendary Shu minister Zhuge Liang: “With the scheme of a tiger and the cunning of a dragon, he conducted the ‘seven captures and seven releases.’ Distraught, he looked to the north. There was much unrest in the Central Plain. Although the desire for conquest was in his heart, he was not ultimately able to realize the ambition.”Footnote 83 The “seven captures and seven releases” refers to Zhuge's famous tactic to subdue the southern rebels led by Meng Huo, and the “look to the north” invokes Zhuge's thwarted effort to topple the Wei regime. Finally, in an even less direct manner, the lord, named Wang Shenzhi (862–925), of a small state based in Fujian also traced his genealogy to the Southern Liang State (502–557), when, as the story goes, a Daoist monk named Wang Ba in Fujian prophesized the rise of a regional state headed by his descendants. Wang Shenzhi, claiming to be a descendant of Wang Ba, hoped that this pre-Tang origin would help his own descendants to rule Fujian: “if the sons and grandsons follow my way, they will be granted the Min region for many generations.”Footnote 84 This wish echoes Zhang Chengfeng's goal to “pass on to sons and grandsons the rule of Dunhuang.”Footnote 85 All of these regional rulers found convenient precedents for regionalism in the Period of Division.

As people like Wang Jian, Liu Yan, and Wang Shenzhi all eventually claimed to be “emperor” (di) in much the same manner as Zhang Chengfeng, their version of political regionalism that combined a universalist claim with regional roots was broadly similar to Zhang's project in Dunhuang. All of these cases included the claim of a pre-Tang regional historical precedent, the assumption of the title of emperor and other imperial pretensions, and regional geographical ambitions. All these states, from the Southern Han to Dunhuang (“western Han”), adopted this type of political regionalism as a direct response to the fall of the Tang and to their understanding of the weaknesses of the North China regimes that succeeded the Tang. There is no clear reason why our telling of Chinese history should continue to follow the practice of Song historians to include the Southern Han but exclude Dunhuang.

By putting Dunhuang back into the narrative of Chinese history in the tenth century, I am, of course, not proposing a framework of “Five Dynasties and Eleven Kingdoms.” Instead, the example of Dunhuang invites us to consider the broader political changes after the fall of the Tang dynasty that cannot be properly placed within the existing historiographical framework developed by Song historians. These changes encompassed the kind of political regionalism seen in Zhang Chengfeng's Dunhuang as well as in the Former Shu and the Southern Han, but also included other forms of political reaction to the fall of the Tang. The Later Tang and the Southern Tang decided to claim themselves as direct heirs to the Tang and to revive the Tang dynasty.Footnote 86 The Later Liang attempted to be a legitimate successor of the Tang; Later Jin and Later Han, on the other hand, maintained imperial pretensions but submitted politically to Khitan.Footnote 87 At the borders of this broad post-Tang world, places like Korea, Vietnam, and Central Asia used the fall of the Tang as an opportunity to graft aspects of Tang royal ideology and vocabulary onto their own states. The kings of both Khotan and Korea, for instance, inventively reused the idea of “China” in their political projects after the fall of the Tang.Footnote 88 Most importantly, the Khitan state retained many Tang institutions, and arguably became the political center of the Eastern Eurasian world after the fall of the Tang.Footnote 89 A comprehensive survey of these new political developments will allow us to go well beyond the “Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms” framework and formulate new ways of understanding the political history of China in the tenth century.

Conclusion

This article recounts a brief and largely forgotten episode in the history of Dunhuang in the early tenth century. With dramatic change of fortunes, military triumphs and failures, imperial ambitions and commoners’ disdain, this episode is interesting and worth telling in its own right. But my goal of telling this story goes a bit further. I argue that Zhang Chengfeng's attempt to build a regional state shows that Dunhuang was not disconnected from North China after the fall of the Tang. Despite Ouyang Xiu's exclusion of Dunhuang as a foreign state, people in Dunhuang were following the events in North China closely and reacted strongly to the fall of the Tang, just like many others in “China proper.” The specific ways in which Dunhuang reacted politically to the fall of the Tang were echoed in other regional states. These states, such as the Former Shu and the Southern Han, were retrospectively treated as belonging to the “Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms,” while the similar post-Tang state-building activities in Dunhuang were forgotten in traditional Chinese dynastic histories.

Through recounting Zhang Chengfeng's brief imperial ambition, I hope to make the case for incorporating Dunhuang and its surrounding region of eastern Central Asia into the narrative of Chinese history in the ninth and tenth centuries. There are two dimensions for such incorporation. The first is historical: places like Dunhuang and its surrounding regions faced similar problems as those in “China proper” after the fall of the Tang and often found similar solutions. They should be considered integral parts of the post-Tang world. Existing frameworks of understanding Chinese history in the tenth century do not allow the incorporation of Dunhuang. While these frameworks are each still useful in certain contexts,Footnote 90 in the realm of political history in particular, I suggest that we seek alternative ways of synthesis that would allow us to incorporate the political histories of places like Dunhuang.

The second dimension of the incorporation of Dunhuang into the narrative of Chinese history is historiographical. Documents from Dunhuang, because they were made before the early eleventh century and sealed in an undisturbed manner until 1900, include many different representations of the political changes of the post-Tang world in the tenth century that did not go through the editing and selection of Song historians. Unlike the histories of the states included in the “Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms” framework, which were all edited by historians in the Song, Dunhuang documents offer a uniquely contemporaneous view of how political figures, and possibly even commoners, reacted to the fall of the Tang. In this article, I demonstrate the usefulness of Dunhuang materials for understanding one type of political regionalism in the broader post-Tang world. But Dunhuang documents contain much more information about other forms of change in the tenth century. In a Khotanese letter, where the king of Khotan claims to be a “King of Kings of China,” in a letter from the emperor of the Later Jin that addressed the Khitan Khaghan as the “Emperor of the Northern Dynasties,”Footnote 91 and in the rich official documents left by the Cao regime we see how a state maintained its vassal status to the North China regime while cultivating a local base of power—an experience also shared by states in “China proper” such as the Kingdom of Chu (907–951) under the Ma family. As Peter Lorge has pointed out that “even were we to defy the category of ‘The Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms,’ it would be reified at the most basic level of research by the change in sources from one traditionally constructed period to the next.”Footnote 92 To go beyond the category of “The Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms,” we need to explore sources that were not produced by Song historians who tended to reify dynastic units based in North China. An examination of the diverse array of political ideologies found in Dunhuang materials and other contemporary textual materials in Turfan, Khotan, and Kharakhoto will lead to a more comprehensive picture of how the world changed politically after the fall of the Tang.