Introduction

Background

Parent–child interaction is a powerful force shaping child development during the dynamic years from birth to five. Although the specifics vary across domains, there is general agreement that early, frequent, and high-quality caregiver–child interaction is important. Broadly, the characteristics of high-quality interaction include parental responsivity (Bornstein, Tamis-LeMonda, Hahn, & Haynes, Reference Bornstein, Tamis-LeMonda, Hahn and Haynes2008), reciprocity (Romeo et al., Reference Romeo, Leonard, Robinson, West, Mackey, Rowe and Gabrieli2018), consistency (Landry, Smith, Swank, Assel, & Vellet, Reference Landry, Smith, Swank, Assel and Vellet2001), awareness of the child's developmental level (Bibok, Carpendale, & Müller, Reference Bibok, Carpendale and Müller2009), playfulness (Weisberg, Zosh, Hirsh-Pasek, & Golinkoff, Reference Weisberg, Zosh, Hirsh-Pasek and Golinkoff2013), and richness (Hirsh-Pasek et al., Reference Hirsh-Pasek, Adamson, Bakeman, Owen, Golinkoff, Pace and Suma2015). High-quality, parent–child interaction has been linked to favorable child development outcomes across a variety of domains. For instance, children who participate in early, frequent, high-quality interactions with their parents tend to exhibit more prosocial behaviors, better emotional regulation abilities (Davidov & Grusec, Reference Davidov and Grusec2006), more adaptive behavioral patterns (Leckman-Westin, Cohen, & Stueve, Reference Leckman-Westin, Cohen and Stueve2009), stronger cognitive skills (Smith, Landry, & Swank, Reference Smith, Landry and Swank2006), and superior language abilities (Hirsh-Pasek et al., Reference Hirsh-Pasek, Adamson, Bakeman, Owen, Golinkoff, Pace and Suma2015) than those who do not.

Naturally, not every parent–child interaction can be optimal, but some dyads face more barriers than others. Two psychosocial factors have received much attention from those interested in successful parenting and parent–child relationships. The first is the parent's perceived locus of control. Control perceptions exist on a spectrum from internal to external. People with more internal control perceptions tend to believe that control over their environment, life outcomes, and relationships lies within them. Conversely, people with more external control perceptions tend to believe that these things are outside of their control (Rotter, Reference Rotter1966). The second factor, perceived self-efficacy – a related but theoretically and measurably distinct construct (Zimmerman, Reference Zimmerman2000) – reflects the degree to which an individual believes she can effect change in herself, her environment, and in others. Historically, self-efficacy has been defined by its four main components: intentionality, forethought, self-reactiveness, and self-reflectiveness (Bandura, Reference Bandura2001). Thus, individuals with high self-efficacy can plan ahead, modify their performance in the moment, and constructively reflect upon previous experiences to effect behavioral change.

More internal control perceptions (Hagekull, Bohlin, & Hammarberg, Reference Hagekull, Bohlin and Hammarberg2001; Hassall, Rose, & McDonald, Reference Hassall, Rose and McDonald2005; Houck, Booth, & Barnard, Reference Houck, Booth and Barnard1991; Lloyd & Hastings, Reference Lloyd and Hastings2009) and a higher degree of perceived self-efficacy (Benzies, Trute, & Worthington, Reference Benzies, Trute and Worthington2013; Coleman & Karraker, Reference Coleman and Karraker2003; DeSocio, Kitzman, & Cole, Reference DeSocio, Kitzman and Cole2003; Hess, Teti, & Hussey-Gardner, Reference Hess, Teti and Hussey-Gardner2004; Jones & Prinz, Reference Jones and Prinz2005) have been linked to positive parenting experiences, constructive parenting practices, and better child outcomes. For instance, external maternal control perceptions were a strong positive predictor of parenting-related stress among parents of children with intellectual disabilities (Hassall et al., Reference Hassall, Rose and McDonald2005). Also, at-risk mothers in a prenatal and infant home-visiting program were less likely to get pregnant again within a year of their child's birth and more likely to be responsive to their infants if they exhibited higher, rather than lower, self-efficacy (DeSocio et al., Reference DeSocio, Kitzman and Cole2003). Finally, lower efficacy perceptions have been bi-directionally associated with child maladaptive behavior (Hassall et al., Reference Hassall, Rose and McDonald2005; Weaver, Shaw, Dishion, & Wilson, Reference Weaver, Shaw, Dishion and Wilson2008).

Communicative interactions

In this study, we expanded upon the existing evidence about the relationship between parental psychosocial perceptions, parenting practices, and child outcomes. Specifically, we were interested in the influence of control and self-efficacy perceptions on parent–child communicative interactions. Early, frequent, high-quality parent–child communicative interactions are critical for developing strong language and preliteracy skills (Cartmill et al., Reference Cartmill, Armstrong, Gleitman, Goldin-Meadow, Medina and Trueswell2013; Hirsh-Pasek et al., Reference Hirsh-Pasek, Adamson, Bakeman, Owen, Golinkoff, Pace and Suma2015; Ramírez-Esparza, García-Sierra, & Kuhl, Reference Ramírez-Esparza, García-Sierra and Kuhl2014; Romeo et al., Reference Romeo, Leonard, Robinson, West, Mackey, Rowe and Gabrieli2018; Rowe, Reference Rowe2012) – skills that are foundational to later academic and life success (Dickinson, Golinkoff, & Hirsh-Pasek, Reference Dickinson, Golinkoff and Hirsh-Pasek2010; Hoff, Reference Hoff2013). Such interactions are characterized by temporally contingent and topically contiguous parental responses, the use of directives that do not require the child to shift attention, the presence of rich language structures, and varied exposure to print concepts (Bibok et al., Reference Bibok, Carpendale and Müller2009; Bornstein et al., Reference Bornstein, Tamis-LeMonda, Hahn and Haynes2008; Flynn & Masur, Reference Flynn and Masur2007; Hirsh-Pasek et al., Reference Hirsh-Pasek, Adamson, Bakeman, Owen, Golinkoff, Pace and Suma2015; Masur, Flynn, & Eichorst, Reference Masur, Flynn and Eichorst2005; Piasta, Justice, McGinty, & Kaderavek, Reference Piasta, Justice, McGinty and Kaderavek2012; Tamis-LeMonda, Kuchirko, & Song, Reference Tamis-LeMonda, Kuchirko and Song2014). We used these evidence-based qualities of parent–child communicative interaction as a basis for selecting the training targets in our study.

It is well established that parent–child communicative interactions are impeded by limited access to time, resources, and support. For instance, socioeconomic status (SES) has been extensively investigated as a variable in mother–child interaction research (Hirsh-Pasek et al., Reference Hirsh-Pasek, Adamson, Bakeman, Owen, Golinkoff, Pace and Suma2015; Hoff, Reference Hoff2013; Rowe, Reference Rowe2008). These studies reveal that, on average, children from low-SES households receive less – and lower quality – early language input than their mid- to high-SES peers, although there is also great variability within SES groups. Caregiver factors like knowledge of child development (Rowe, Reference Rowe2008; Suskind et al., Reference Suskind, Leung, Webber, Hundertmark, Leffel, Suskind and Graf2018) and maternal depression (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Malmberg, Sylva, Barnes and Leach2008) also relate to the quality and quantity of mother–child communication interactions, revealing positive and negative associations, respectively. The influence of control and efficacy perceptions on mother–child communicative interactions is unknown. We sought to fill this gap by examining maternal perceived locus of control and self-efficacy within the context of a mother–child language and literacy training program. Understanding the role of maternal psychosocial factors in interaction and training outcomes is a necessary first step towards improving individualized parent training recommendations and broader training approaches.

Parent training to support early language and literacy

An early language and literacy parent training program is an ideal setting for studying maternal control and efficacy perceptions. The training protocol itself affords many opportunities to observe communication between mother and child in a manner that is controlled across dyads. These training programs require parents to be active agents in their own change as well as their child's. Thus, parents’ beliefs about their ability to effect change or their control perceptions could impact their readiness or ability to implement trained strategies. For example, parents are often asked to expand on what their child says as part of early language programs. To expand on a child's production the adult must follow what the child is attending to, process the child's production, and provide a contingent, enhanced response. Parents who believe themselves to be more efficacious, or with more internal control, may be more prepared to provide this input.

There is also a practical advantage in that parents and other caregivers are increasingly targeted through training programs to improve caregiver–child interaction (Reese, Sparks, & Leyva, Reference Reese, Sparks and Leyva2010; Roberts & Kaiser, Reference Roberts and Kaiser2011). Not all caregivers are able to implement even the most rigorously evidence-based techniques equally well, and not all children benefit comparably from caregiver-implemented programs. We do not fully understand why.

Reese and colleagues (2010) conducted a review of parent training programs that focused on early language and reading skills in typically developing children. They suggested that parents are an underutilized resource, but noted that factors like the focus of the program (e.g., language vs. writing) and adversity (e.g., low-SES) need to be considered in selecting training targets. Similarly, Roberts and Kaiser (Reference Roberts and Kaiser2011) conducted a meta-analysis of parent-implemented early language programs for children with primary or secondary language impairment. They found these programs to be generally effective, but the effect sizes varied greatly. Furthermore, only receptive language and expressive syntax outcomes were significant when compared to clinician-implemented intervention (Roberts & Kaiser, Reference Roberts and Kaiser2011). However, this meta-analysis did not explore the potential factors that might impact how well parents are able to implement trained techniques. These papers simultaneously illustrate the promise of parent training programs and the need to understand differences that might impact individual training outcomes.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to address this gap. We asked several questions in the context of a training program designed to enhance the quality of the language interactions between mothers and their children. Table 1 describes our three research questions and hypotheses. Our primary focus was on examining the role of maternal psychosocial factors on training outcomes. However, we also evaluated the efficacy of our training program and baseline maternal input quality as preliminary steps. Broadly, we expected that traditionally more favorable (i.e., high self-efficacy and internal control perceptions) maternal self-efficacy and control would be positively associated with high-quality language input, child language abilities, and print awareness at baseline. We predicted that maternal self-efficacy and control would significantly contribute to predicting training outcomes, but we were unsure of the directionality – hence the need for this study.

Table 1. Research questions and hypotheses

Methods

Study design

This was a behavioral randomized controlled trial designed to explore if and how maternal control and efficacy perceptions relate to training program outcomes. Although determining training efficacy was a preliminary step, the main focus of the study was to examine the role of maternal psychosocial factors in predicting training outcomes. Mother–child dyads were randomly assigned to two parallel arms – immediate- or delayed-training control group in a 1:1 ratio. Maternal use of language strategies and child language skills were assessed at three time-points (baseline, after one month at the end of training, and one month post-training). The delayed-training control group was a no-treatment control during the course of the study. For ethical reasons, we wanted them to have the opportunity for training, so we offered training to them after the study ended. There were no changes to the eligibility criteria or training protocol during data collection. This study was not pre-registered, but it was part of a dissertation project, so the questions and outcomes were documented prior to data collection. We use the CONSORT guidelines here in reporting the trial outcomes (Schulz, Altman, & Moher, Reference Schulz, Altman and Moher2010; a copy of the checklist is included in the Supplementary materials, available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000919000138>).

Participants

Recruitment

This research was conducted in a small, Midwestern university town. University-wide e-mails, flyers around the community, and word of mouth were used to recruit dyads. The study was approved by the University's Institutional Review Board.

Sample size

This study was powered for the main research question about maternal psychosocial factors and training outcomes. Given that this was a pilot study, and that we had limited a priori knowledge of the anticipated variability in the sample, we used a rule of thumb approach to estimate our sample size of 30. This approach is consistent with recent recommendations for pilot trials (Whitehead, Julious, Cooper, & Campbell, Reference Whitehead, Julious, Cooper and Campbell2016).

Eligibility criteria

Participants were 30 mother–child dyads (n = 15 immediate-training group and n = 15 delayed-training control group). English-speaking mothers with a minimum of high-school level educational attainment (age 21–40) and their first-born children (age 2;6–4;0) with no mother-reported speech, language, hearing, learning, or other developmental delays or disorders were invited to participate. All children had to score better than –1 standard deviation on standardized expressive and receptive vocabulary measures (Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Fourth Edition and Expressive Vocabulary Test-Second Edition; Dunn & Dunn, Reference Dunn and Dunn2007; Williams, Reference Williams2007) to be eligible to participate. All data collection and training took place in the lab except for the initial eligibility screening and remote check-in during training, which took place via phone. One child in the control group received an autism-spectrum diagnosis over the course of the study. All analyses were conducted with and without this child's data, but ultimately the child was not excluded from the analyses as the results did not differ – or were less conservative when the child was excluded.

The first-born eligibility criterion was used to control for potential changes in maternal locus of control based on parenting experience (Houck et al., Reference Houck, Booth and Barnard1991). Maternal self-efficacy and control perceptions had not previously been explored as they relate to early language interaction quality and parent training outcomes. Thus, we chose to examine these constructs during interactions with typically developing children as a first step in this line of inquiry. The age range for the children was comparable to other early language training studies (Baxendale & Hesketh, Reference Baxendale and Hesketh2003; Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Hemmeter, Ostrosky, Fischer, Yoder and Keefer1996; Lonigan & Whitehurst, Reference Lonigan and Whitehurst1998). However, the children in the current study were younger than those in most print knowledge programs (Justice & Ezell, Reference Justice and Ezell2000, Reference Justice, Weber, Ezell and Bakeman2002; Lovelace & Stewart, Reference Lovelace and Stewart2007). This age range was selected to prevent ceiling effects, given that the children in the present study were typically developing.

Training

Eligible dyads who were randomly assigned to the training group participated in four training sessions over approximately four weeks and a two-month follow-up session. Control-group dyads completed three data collection sessions (i.e., baseline, one month, and two-month follow-up) in addition to the initial screening session. Training and control-group dyads were given the selected books to take home, but the control-group dyads were not instructed on their use of the books. Data collection for both groups occurred simultaneously. There was no attrition, but one control-group dyad completed their follow-up session three weeks late due to scheduling difficulties. An overview of the protocol for the two groups is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Training and control-group procedures by session

Training protocol

The instructional component of the training group sessions took place during sessions two, three, four (phone session), and five. The training sessions lasted approximately 30–40 minutes each time except for the 5- to 10-minute phone session. The training sessions began with the naturalistic reading and play activity upon which the individual feedback was based (see Table 2). The dyads were provided with a new book during each of the in-laboratory sessions. Mothers were prompted to read with their child like they typically would at home. After the dyad finished the book, the trainer brought in a selection of five toys – sand, a board game, a toy food set, a toy zoo set, and a pretend doctor kit – for 15 minutes of free play. During the reading and play sessions, the trainer sat in the adjacent observation room behind a one-way mirror and took notes on the mother's use of the target strategies. These notes were later used as part of the parent training. Sessions in the lab were video-recorded.

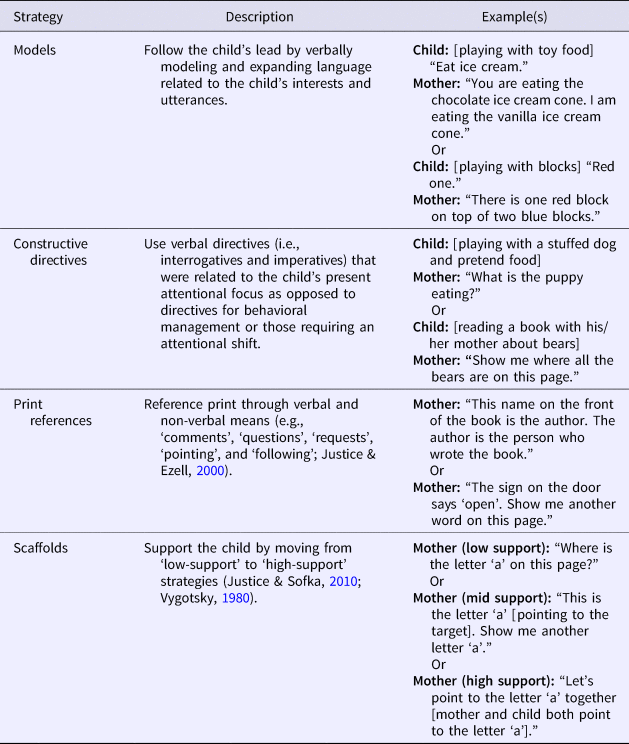

After the free-play session, the trainer returned to the room to provide feedback. Mothers were taught four evidence-based language stimulations strategies (Table 3). First, a written copy of the four training strategies and accompanying real-life video examples were shown to the mother. After reviewing the videos and strategies, the mother was asked to summarize her understanding of the targets. Then, the trainer provided the mother with feedback about the reading and play session she had just completed with her own child related to the target strategies. Each mother was provided with feedback related to the same four strategies, but the feedback was individualized to that dyad's specific performance. For example, each mother was given one example of something she was already doing well and one new thing to try related to the use of scaffolding.

Table 3. Training strategies

Book selection

Each book was selected to have a similar print salience metric based on ratings from a list of over 100 children's books by Justice and Sofka (Reference Justice and Sofka2010). First, only narrative books from the list were examined, then four of the books with the highest and most similar print salience values were selected (range overall: 0–9.28, range for this study: 3.86–4.34; Justice & Sofka, Reference Justice and Sofka2010). The books were also chosen to be similar in thematic content – three books about starting school and one about letters. The analyses were adjusted for the length of each book.

Outcomes

Mothers’ use of target language and print strategies

Use of the four language and print strategies – models, constructive directives, scaffolds, and print references – was coded from videos of the mother–child interactions during reading and play at baseline, one month, and two months using ELAN (Wittenburg, Brugman, Russell, Klassman, & Sloetjes, Reference Wittenburg, Brugman, Russell, Klassman and Sloetjes2006). Descriptions and examples of the strategies are provided in Table 3. A coding manual was developed to support reliability. This was an event-based coding system in that the outcome was the total number of strategies (and the number of each type of strategy) used during the reading and play sessions. An utterance could be assigned more than one code if it could be classified as multiple different strategies (e.g., a scaffold and constructive directive). A speaker change or more than 2-second pause indicated a turn change.

The coding of the reading session began when the mother started addressing the book (e.g., picking it up and reading the title), and finished when the book was closed. Since all dyads shared the same books they all had equal opportunities to interact during each reading session. Coding of the play sessions began two minutes into the sessions and lasted for seven minutes. This allowed dyads to settle into the play interaction before coding began.

Maternal perceived locus of control

Maternal control perceptions were assessed using the Internal–External Scale (IES) at baseline (Rotter, Reference Rotter1966). We selected this scale because it had been recently validated, used widely, and shown to capture individual variability in domain-general control perceptions amongst adults (Bedel, Reference Bedel2012; Houck et al., Reference Houck, Booth and Barnard1991). The IES has 29 forced-choice items that prompt mothers to select the statement with which they agree the most. These statements contrast perceptions about concepts like nature vs. nurture, luck vs. work, and the impact of an individual on their peers and environment (e.g., “In the long run the bad things that happen to us are balanced by the good ones.” vs. “Most misfortunes are the result of lack of ability, ignorance, laziness, or all three.”; Rotter, Reference Rotter1966, p.12). Internal consistency on this measure ranged between .65 and .79 across the 1600 participants included in the initial validations studies. The IES includes six unscored distractor items – with a maximum possible score of 23. As scores move from low to high, the corresponding control perceptions move from more internal to more external (Rotter, Reference Rotter1966).

Maternal perceived self-efficacy

Maternal efficacy perceptions were assessed using the Self-Efficacy Scale at baseline (Sherer & Adams, Reference Sherer and Adams1983; Sherer et al., Reference Sherer, Maddux, Mercandante, Prentice-Dunn, Jacobs and Rogers1982). This scale has been used in a variety of studies and is sensitive to individual differences in domain-general self-efficacy (Scherbaum, Cohen-Charash, & Kern, Reference Scherbaum, Cohen-Charash and Kern2006; Wei, Russell, & Zakalik, Reference Wei, Russell and Zakalik2005). This is a 23-item scale including two subscales measuring general and social self-efficacy. Sherer and colleagues reported a Crohnbach's alpha of .86 and .71 for these scales. Each item contains a statement (e.g., “If I can't do a job the first time, I keep trying until I can.”; Sherer et al., Reference Sherer, Maddux, Mercandante, Prentice-Dunn, Jacobs and Rogers1982, p. 666), with which mothers are asked to rate their level of agreement on a 5-point scale (from ‘strongly disagree’ = 1 to ‘strongly agree’ = 5). An overall score is calculated from the sum of the score of each of the items. Lower scores correspond to less perceived self-efficacy, while higher scores correspond to greater perceived self-efficacy (Sherer & Adams, Reference Sherer and Adams1983; Sherer et al., Reference Sherer, Maddux, Mercandante, Prentice-Dunn, Jacobs and Rogers1982).

Maternal responsivity

The temporal and topical relationships between mother and child utterances were coded at baseline, one month, and two months. Consistent with previous research, maternal utterances that started within two seconds of the child's production and were related in topic to what the child said were labeled responsive (Justice, Weber, Ezell, & Bakeman, Reference Justice, Weber, Ezell and Bakeman2002). This behavior was predicted to relate to the use of the target strategies – particularly the modeling/expanding strategy – but it was not explicitly taught. Therefore, it was a measure of generalization when examining the training efficacy and predictors of training gains.

Child language

The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Fourth Edition (PPVT-4; Dunn & Dunn, Reference Dunn and Dunn2007) and the Expressive Vocabulary Test-Second Edition (EVT-2; Williams, Reference Williams2007) were used to assess children's vocabulary abilities at baseline. Fifty-utterance language samples were collected at baseline and follow-up to track change children's language skills over the course of the study. These samples were used to measure children's conversational use of language. These samples were collected during mother–child play interactions with an array of toys. The choice to collect the language sample from interaction with the mother, as opposed to the clinician, was a conscious one given that the training focused on this dyadic interaction. The language sample metrics included the number of different words (NDW), number of total words (NTW), and the ratio between the two (NDW/NTW). The language samples were transcribed and analyzed using SALT (Miller & Chapman, Reference Miller and Chapman2006).

Child print awareness

Print awareness was one of the child outcomes we measured to evaluate the training and examine predictors of training gains – measured at baseline, one month, and two months. The evaluation tool was an age-appropriate 20-item, criterion-referenced assessment from Lovelace and Stewart (Reference Lovelace and Stewart2007). Prior versions of the assessment have also been used in in research predicting later literacy outcomes in young children (Justice & Ezell, Reference Justice and Ezell2002). The assessment asks children to identify a variety of print targets like the title, author, and direction of the text.

Randomization

Eligible dyads were randomly assigned to either the immediate-training group (henceforth the ‘training group’) or to a delayed-training control group (henceforth the ‘control group’). A stratified – by child sex – permuted, blocked design (blocks of six) was used to maintain group balance. The randomization was generated by one of the authors not involved in screening or enrolling participants. The first author completed the screening and enrollment process for each before opening the next study assignment document. The participant assignment sequence was stored on a computer document, so only one assignment was visible on each page. This concealed the order of future assignments.

Blinding

The first author conducted all study sessions and preliminarily coded the parents’ use of target strategies. The first author was blind to group randomization order until after participants had been enrolled. A second coder, who was blind to group assignment, conducted coding reliability analyses. The baseline language samples were transcribed by a student who was blind to the group membership and hypotheses. Reliability for the follow-up language samples was also done by this student.

Statistical methods

All analyses were conducted using SAS University Edition. Given the exploratory nature of this study, the cut-off for all tests was α = .05 Type I error level. Normality assessments (Shapiro–Wilk Test; Shapiro & Wilk, Reference Shapiro and Wilk1965) were conducted for each measure to determine the need for parametric or non-parametric hypothesis testing. Cases in which non-parametric tests were used are specified; otherwise it can be assumed that the data met the normality criteria.

Repeated measures analysis of variance (RMANOVA) models were constructed to evaluate the treatment outcomes over the three time-points. Each model was adjusted for baseline performance on the outcome measure. Pearson correlations between baseline and outcome measures of interest were calculated prior to conducting the modeling analyses. The correlational analyses used the data from the training and control group at baseline. The Ferguson (Reference Ferguson2009) guidelines were used when interpreting the correlations (i.e., r = .2 minimum for clinical significance, r ⩾ .5 ‘moderate’ effect, r ⩾ .8 ‘strong’ effect) and effect sizes. These effect size guidelines provide guidance for interpretation beyond traditional statistical significance by also examining the possibility for clinical significance or promising trends.

Multiple regression models were used to examine the relationship between the maternal psychosocial measures and training program outcomes from baseline to follow-up. Covariates included in the full model were chosen based on the correlational data using the (Ferguson, Reference Ferguson2009) guidelines. On occasions when several child factors were potential covariates, the one with the largest correlation to the outcome measure was selected to prevent collinearity.

Fidelity and reliability

Fidelity-to-treatment analyses

A trained undergraduate student performed fidelity-to-treatment checks on one-third of the treatment sessions using a 35-item, presence or absence checklist describing the order and content of each session. Overall treatment fidelity was 98% (517/525 targets present across 15 sessions). Fidelity-to-treatment ranged from 91% (32/35 targets) to 100% (35/35 targets) within the sessions, and 67% of the sessions exhibited 100% treatment fidelity.

Language samples

A trained graduate student blind to group assignment coded the baseline language samples. The PI transcribed the final language samples, but reliability checks were done on a randomly selected four of them (out of 30; 2 training and 2 control) by a trained undergraduate who was also blind to group assignment. Inter-transcriber reliability was 97.5% (5 disagreements in 200 utterances).

Coding reliability

The PI coded all of the reading and play interaction videos based on maternal responsivity and target strategy use. Twelve of the videos (out of 90: 2 training and 2 control at each time-point) were randomly selected and re-coded by a trained undergraduate coder who was blind to group assignment and hypotheses. Inter-coder agreement was 93.6% overall, 94.9% during reading, and 92.4% during play.

Results

Participant flow

Thirty-one dyads completed the screening, but one dyad decided not to continue prior to baseline data collection (Figure 1). Thus, there were 30 dyads for the analyses presented here.

Figure 1. Participant flow.

Recruitment

Recruitment, training, and follow-up procedures took place between February and June of 2015. The trial ended when the target number of participants had been enrolled.

Baseline data

Demographic data describing the two cohorts are presented in Table 4. Although there were unequal numbers of male and female children, the ratio of male to female children (i.e., 6:9) was the same for both groups. All participants selected ‘white’ as their racial category. There were no significant baseline differences between the control and training groups (Table 4). Independent-sample t-tests or Wilcoxon Two-Sample Tests were used as appropriate for these comparisons. Only one effect size – maternal strategy use (d = 0.49) – met the minimum reporting level (Ferguson, Reference Ferguson2009). Thus, the groups were well matched. Furthermore, all analyses relating to strategy use controlled for baseline performance.

Table 4. Baseline participant characteristics for control and training group

Note. aNon-parametric test. Effect sizes are Cohen's d (Cohen, Reference Cohen1969). Ferguson (Reference Ferguson2009) recommends the following lower limit values for Cohen's d: minimum reportable level = 0.41, moderate = 1.15, large effect = 2.70.

Numbers analyzed

There were 30 dyads (n = 15 immediate training, and n = 15 delayed-training control) included in the analyses.

Outcomes

Training program outcomes for mothers and children are presented in Table 5. Unadjusted and adjusted (for baseline) mean differences are presented along with 95% confidence intervals. In each of the models we considered the following covariates: maternal age, maternal education, child age, and child vocabulary score. We included any given potential covariate in the models only if it was significantly correlated with the outcome of interest. All outcome measures were adjusted for baseline performance by the inclusion of baseline scores in the model.

Table 5. Training program outcomes at two-month follow-up

Does the training program work?

Mothers

The effect of the treatment on the mothers was evaluated with a 3 (time: baseline, one month, two months) × 2 (group: treatment, control) RMANOVA model. The dependent variable was the total number of the four strategies of interest that were used by the mother during reading and play. There was a significant main effect for time (F(2,56) = 18.61, p < .0001, η 2 = 0.34) and group (F(1,28) = 15.90, p < .001, η 2 = 0.39). There was a significant time × group interaction (F(2,56) = 11.70, p < .0001 η 2 = 0.21). The training group made significantly greater gains in strategy use over time than the comparison group. At follow-up mothers in the training group used an average of 75.87 more strategies in their interactions than mothers in the control group after adjusting for baseline. This effect was apparent for all four strategies, but the difference between mothers in the training and control groups was the largest for constructive directives and scaffolds. Mothers in the training group used 24.73 more constructive directives and 22.60 more scaffolds than the control group mothers at follow-up. A more detailed context and strategy breakdown is available in Alper (Reference Alper2015).

To determine whether the treatment generalized to untrained behaviors, we used a 3 (time: baseline, one month, two months) × 2 (group: treatment, control) RMANOVA model. The dependent variable was the percent of mother's utterances that were responsive to the child's utterance during reading and play. There was a significant main effect for group (F(1,28) = 8.12, p < .01, η 2 = 0.27) and a significant time × group interaction (F(2,56) = 4.36, p = .02, η 2 = 0.13). There was no significant main effect for time. Mothers in the training group increased their responsivity over time while mothers in the control group decreased. At follow-up mothers in the training group were 11.73% more responsive than mothers in the control group after adjusting for baseline (Table 5).

Children

The effect of the treatment on the children was evaluated with three 3 (time: baseline, one month, two months) × 2 (group: treatment, control) RMANOVA models. The dependent variables were the number of print targets the children were able to identify, the number of different words they produced during their language samples, and their NDW/NTW ratios. There were no significant group differences in the number of different words or NDW/NTW ratios after training. When examining print awareness outcomes, there was a significant main effect for time (F(2,56) = 15.63, p < .0001, η 2 = 0.42) and group (F(1,28) = 6.5, p = .02, η 2 = 0.2). There was also a significant time × group interaction (F(2,56) = 3.92, p = .03, η 2 = 0.1). Children in the training group made greater gains than those in the control group.

Do maternal control and efficacy perceptions relate to the quality of maternal language input and child language measures at baseline?

Lower scores on the locus of control measure indicate more internal (traditionally more favorable) locus of control perceptions; higher scores on the self-efficacy measure indicate higher (traditionally more favorable) self-efficacy perceptions. Maternal perceived locus of control and self-efficacy scores were marginally correlated with each other at baseline (r = –0.36, p = .05). Thus, high perceived self-efficacy tended to be associated with more internal control perceptions. Neither self-efficacy nor locus of control correlated with mothers’ baseline strategy use or responsivity.

As predicted, children whose mothers had more internal control perceptions tended to identify more print targets at baseline (r = –0.42, p = .02; Table 6). There was no correlation between locus of control and the children's spoken language abilities measured as NDW, NDW/NTW ratio, or vocabulary scores. Contrary to our predictions, children whose mothers had higher self-efficacy perceptions tended to use fewer different words (NDW; r = –0.53, p = .002) and have a lower number of different words to number of total words (NDW/NTW) ratio (r = –0.49, p = .05). There was no correlation between maternal self-efficacy and the children's print identifications or vocabulary scores.

Table 6. Baseline Pearson correlations between maternal locus of control, self-efficacy, child language measures, and covariates

Notes. N = 30 dyads. Maternal education represented the number of years past high school. PPVTR = raw score on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Fourth Edition (Dunn & Dunn, Reference Dunn and Dunn2007). EVTR = raw score on the Expressive Vocabulary Test-Second Edition (Williams, Reference Williams2007). Print = number of print targets identified by the child. * p < .1, ** p < .05, *** p < .01.

Do maternal control and efficacy perceptions relate to maternal and child training outcomes?

Maternal outcomes

We focused on the outcomes for which mothers in the training group made greater gains than the control group – The number of strategies used and percent of responsive utterances. First, we examined the combined training and control group correlations between maternal perceived self-efficacy, locus of control, potential covariates, and maternal outcomes (i.e., strategy use and responsivity). Self-efficacy, but not locus of control, was marginally correlated with strategy (r = –0.30, p = .11) and responsivity (r = –0.32, p = .08) increases; the lower the self-efficacy at baseline, the greater the gains. Maternal age, child age, and maternal education were not correlated with the maternal outcomes. Child receptive vocabulary score at baseline was significantly and positively correlated with mothers’ increase in strategy use (r = 0.39, p = .03).

Based on the correlational data, we constructed multiple regression models to determine whether maternal perceived self-efficacy contributed significantly to predicting maternal training gains. After controlling for group (i.e., the effects of training), maternal self-efficacy was not a significant predictor of strategy or responsivity increases.

Child outcomes

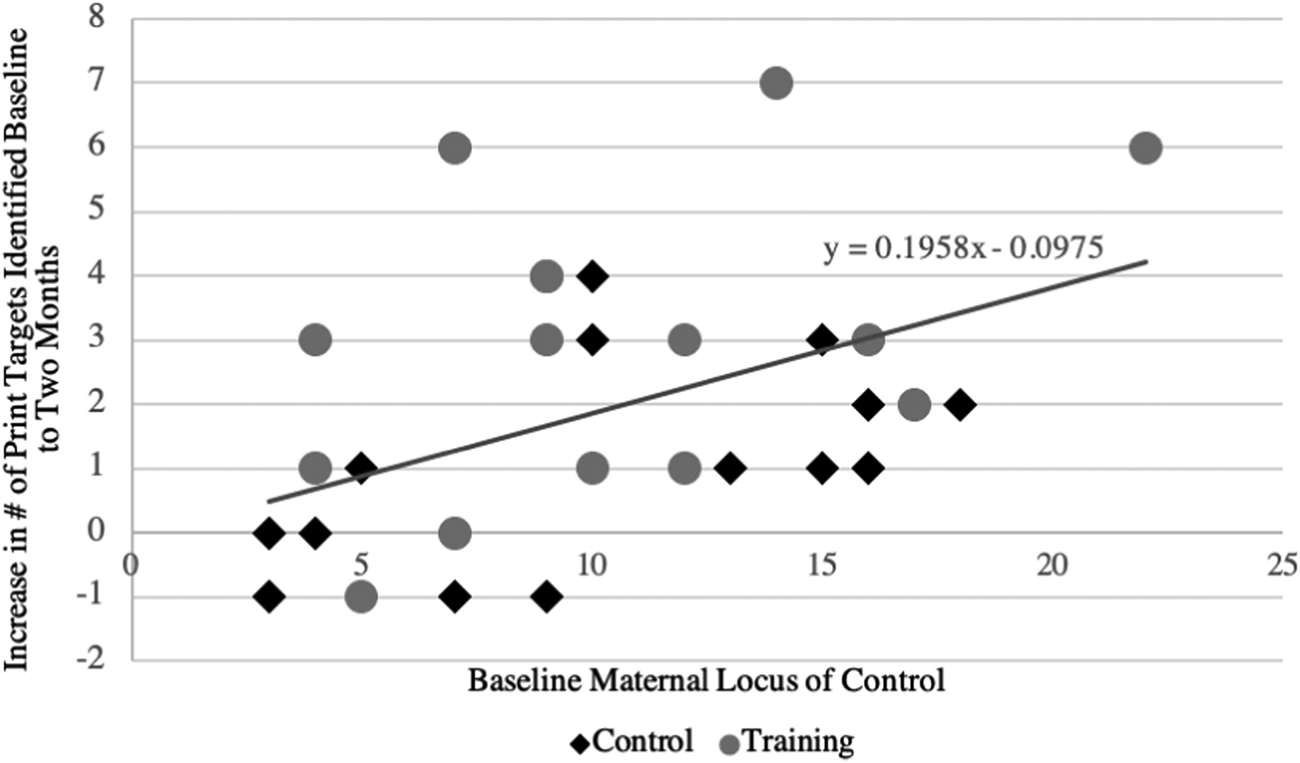

Table 7 shows the correlations between baseline participant characteristics and child gains from baseline to follow-up. We focused on the child outcome on which the training group showed significant improvement compared to the control group – The number of print targets identified. Children whose mothers had more external (traditionally less favorable) control perceptions at baseline tended to make greater gains in print identification from baseline to follow-up (r = 0.46, p = .01).

Table 7. Training and control-group Pearson correlations between maternal locus of control, self-efficacy, child outcome measures, and covariates

Notes. N = 30 dyads. Maternal education represented the number of years past high school. PPVTR = raw score on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Fourth Edition (Dunn & Dunn, Reference Dunn and Dunn2007). EVTR = raw score on the Expressive Vocabulary Test-Second Edition (Williams, Reference Williams2007). Print = number of print targets identified by the child. * p < .1, ** p < .05, *** p < .01.

A multiple regression model was constructed to test if maternal control perceptions significantly contributed to predicting child print gains from baseline to the two-month follow-up. The model incorporated the training and control-group data, but controlled for group membership as well as baseline performance through the use of the change score. Figure 2 shows a scatter-plot of print gains by baseline maternal locus of control and group. In our regression model, group membership and perceived locus of control explained 39% of the variance in print gains from baseline to two-month follow-up (R2 = .39, F(2,27) = 8.67, p = .001). Both group membership (β = –1.83, p < .01) and perceived locus of control (β = 1.87, p < .01) were significant predictors. There was no significant interaction between group and locus of control. Thus, after adjusting for the effect of group membership, children whose mothers had more external control perceptions at baseline made greater gains in print awareness from baseline to two-month follow-up.

Figure 2. Scatter-plot of training and control-group print gains from baseline to two-month follow-up by baseline maternal locus of control. Higher locus of control scores reflects more external control perceptions. The trendline is based on the combined data from the two groups.

Harms

There were no adverse effects reported during the course of the study.

Discussion

Overview

A greater understanding of the psychosocial factors that influence parent–child communicative interactions may ultimately support the development of more effective interventions. We chose to focus on self-efficacy and control perceptions because these factors are potentially malleable and have been positively associated with parenting practices and child outcomes (Benzies et al., Reference Benzies, Trute and Worthington2013; Lloyd & Hastings, Reference Lloyd and Hastings2009). We examined the influence of these factors on mother–child communicative interactions within the context of a language and preliteracy parent training program. The program itself was efficacious for the mothers and the children. We did not find any relationships between maternal psychosocial factors and maternal communication practices (either at baseline or in changes in those practices over time). However, we did find that children whose mothers had a more internal locus of control identified more print targets at baseline, and those whose mothers had a more external locus of control made more gains in print identification over time. Children whose mothers had a higher sense of self-efficacy used fewer different words and had lower NDW/NTW ratios at baseline. Below, we interpret these findings more fully.

Training program

The training program used in this study was designed using established, evidence-based approaches to provide a controlled context for examining the role of maternal perceived self-efficacy and locus of control. Therefore, we expected to replicate previous studies that found this type of training to be efficacious (Reese et al., Reference Reese, Sparks and Leyva2010), and we did. Still, the one-on-one approach, light-touch dosage of around two hours’ total contact time, and unique combination of language and print content, were distinguishing aspects of this training program. Additionally, the training program was efficacious for both mothers and children. We observed significant increases in domains that were directly targeted, like maternal strategy use, and through generalization, like child print awareness and maternal responsivity. Furthermore, these increases were robust even one month after having received the last training session. Although typically developing, the children were younger than those often included in print awareness interventions (Justice & Ezell, Reference Justice and Ezell2000, Reference Justice, Weber, Ezell and Bakeman2002; Lovelace & Stewart, Reference Lovelace and Stewart2007), thus we have demonstrated that very young children can benefit from these programs.

There were qualitative – not just quantitative – differences in maternal input after training. The increased use of constructive directives and scaffolds – strategies which support child participation – is particularly noteworthy. There is mounting evidence that the quality of adult language input – including adult–child turns and wh-question use – matters as much or more than input quantity (Romeo et al., Reference Romeo, Leonard, Robinson, West, Mackey, Rowe and Gabrieli2018; Rowe, Leech, & Cabrera, Reference Rowe, Leech and Cabrera2017).

Maternal psychosocial factors and baseline measures

After determining that our training was efficacious, we examined the baseline maternal and child profiles to inform our main question about training outcomes. More internal maternal control perceptions were significantly correlated with greater child print awareness at baseline. This finding expands upon previous work demonstrating positive associations between maternal psychosocial factors and positive parenting practices (DeSocio et al., Reference DeSocio, Kitzman and Cole2003; Hagekull et al., Reference Hagekull, Bohlin and Hammarberg2001; Jones & Prinz, Reference Jones and Prinz2005). We speculate that mothers who have a more internal locus of control may be more likely to offer their children direct pre-reading instruction rather than waiting for teachers to introduce this material. That said, given that these are correlational data, we cannot determine whether child ability drives maternal psychosocial perceptions or vice versa.

The significant negative correlations between maternal self-efficacy and child NDW and NDW/NTW ratios are puzzling. We think it likely that the finding reflects the interactive context in which we measured NDW. Specifically, we measured NDW in language samples collected during mother–child play interactions. Mothers with lower self-efficacy might have been less active participants in the play than mothers with higher self-efficacy, hence, their children had more chances to talk, more chances to produce a variety of different words. None of our measures of mothers’ communicative behaviors at baseline captured this hypothesized difference so a conclusive interpretation is not possible. Further exploration of this is warranted, given the mounting evidence that high-quality interaction includes adult–child turns, not just adult input (Romeo et al., Reference Romeo, Leonard, Robinson, West, Mackey, Rowe and Gabrieli2018).

Maternal psychosocial factors and training outcomes

Children whose mothers had more external control perceptions at baseline made greater gains in print awareness over time. This was true even after controlling for the treatment effect. Together, these factors – group membership and maternal locus of control – explained approximately 40% of the variance in children's print awareness gains. There are a variety of complex skills involved in naturally incorporating print references into book sharing. The training in the present study asked mothers to incorporate print references while also engaging in the other high-quality language stimulation behaviors. Mothers needed to identify print targets and highlight them responsively and with appropriate scaffolding – this is not a simple task. Notably, print references were the least frequently occurring behavior at baseline. Sharing control of the interaction and following the child's lead may be more difficult for mothers with more external control perceptions. This could explain why the children of these mothers made greater gains, particularly in the challenging domain of print awareness. Moreover, recall that children whose mothers had more internal locus of control perceptions tended toward better print identification at baseline than other children. In a sense, these mothers had less to teach their children about print than mothers who had a more external locus of control.

Limitations

This was a preliminary study involving a small sample. This could have impacted our ability to detect group differences at baseline (e.g., the effect sizes in Table 4) and over time. The homogeneity of the participant sample allowed us to minimize potential confounds between the training and control groups due to variations in SES, cultural background, and educational attainment. However, the same homogeneity that enhanced internal validity represents a threat to external validity. Although there was enough variability to meet the requirements for normality on most of the measures, we cannot be confident that our findings would generalize to mother–child dyads from less affluent, less educated, or minority communities. We are particularly interested to know whether the results will generalize to children with communication disorders. A second limitation is that the data gathered here reflect general measures of self-efficacy and locus of control due to the lack of available domain-specific scales at the time of data collection. Although this does not negate the importance of the general measures, it is possible that stronger associations would have been observed with more tailored scales.

Future directions

Our findings suggest the utility of considering parent psychosocial perceptions when designing early language training programs. Further research is needed to link specific approaches with given psychosocial profiles, but the evidence presented here is the first step in this process. A critical next step is to investigate these caregiver characteristics with children who need these training programs most – those at risk for poor language outcomes due to learning environment, communication disorder status, or both.

Conclusions

This was an exploratory study examining how caregiver psychosocial factors relate to the quantity and quality of caregiver language input as well as caregiver–child outcomes during an early language and literacy parent training program. The results of this study showed that our training was efficacious for mothers and children. Furthermore, maternal control perceptions significantly predicted child print knowledge at baseline and gains over time above and beyond the effect of training. Individual-level psychosocial factors can affect the quality of mother–child communicative interaction and the efficacy of language and literacy training programs that exploit these interactions.

Supplementary materials

For Supplementary materials for this paper, please visit < https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000919000138>).

Author ORCIDs

Rebecca M. ALPER, 0000-0002-3192-8720; Karla K. MCGREGOR, 0000-0003-0612-0057

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project was provided by the Fahs-Beck Fund for Research and Experimentation (Dissertation Grant), the University of Iowa Graduate and Professional Student Government (Research Grant), and the University of Iowa Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders. These sponsors did not play a role in study design, analysis, or selection of publication destination. Toni Becker and Rex Hadden provided support with language samples, reliability coding, and fidelity-to-treatment analyses.