INTRODUCTION

The aims of this study are twofold. The first is to document how the use of past tense verbs changes over time in Spanish-speaking children's intra-conversational narratives from two to three years of age. The second is to explore children's use of past tense verbs in relation to their use of temporal/aspectual markers in co-constructed narrative discourse at this early age. Interrelationships among grammatical and discourse skills are described for two monolingual Spanish speakers throughout their third year of life as they become gradually more adept at encoding temporality.

Narratives emerge in the context of heavily scaffolded parent–child conversations as early as two years of age. Starting at about age two, the major developmental tasks within language development include perfecting grammatical skills and acquiring discourse skills essential to producing longer stretches of talk such as narratives (Ninio & Snow, Reference Ninio and Snow1996). A particular challenge characteristic of narrative development is temporal displacement, i.e. the ability to communicate about events that lie outside the immediate context of the conversation (Ninio & Snow, Reference Ninio and Snow1996; Sachs, Reference Sachs and Nelson1983). Children's first conversations center on persons, objects or events that are present in their environment. In narratives about past or fictional events, children have to move from the ‘here-and-now’ to the ‘there-and-then’, and thus cannot rely as much on contextual support (Sachs, Reference Sachs and Nelson1983). This discourse genre requires, in Gerhardt's (1988: 205) words, ‘the capacity to use language as its own context’. Indeed, contextual support needs to be replaced by the linguistic skills required to express, among other relations, the temporal connections necessary to construct a narrative. Temporality is a crucial dimension of narratives as the temporal sequence of events is what moves the plot forward (Labov & Waletzky, Reference Labov, Waletzky and Helm1967).

Temporality is defined here as ‘the expression of the location of events on the timeline, temporal relations between events and temporal constituency of events [i.e. aspectual information]’ (Berman & Slobin, Reference Berman and Slobin1994: 19). Speakers signal temporal information through language in multiple ways: via grammatical morphemes such as tense/aspect marking on verbs; via lexical items such as temporal/aspectual adverbs, connectives and expressions (later, then); and via discourse strategies, such as the sequential disposition of events in a narrative. Even though most languages make use of grammatical, lexical and discourse devices for expressing temporality, the mappings between temporal notions and linguistic forms vary from language to language, making the development of temporality language-specific (Berman & Slobin, Reference Berman and Slobin1994; Hickmann, Reference Hickmann2003). Spanish is an interesting language for the study of temporal expression because its complex verbal paradigm richly encodes temporal and aspectual relations.

The Spanish verbal system offers a particularly researchable developmental challenge in that control of the full paradigm requires, in addition to attention to number and person, control over three tenses (past, present and future), at least four aspects (perfective, imperfective, perfect and progressive) and three moods (indicative, subjunctive and imperative). Spanish has a synthetic morphology; there are forty-plus distinctively marked forms of each verb stem, as well as additional twenty-plus forms created with auxiliary verbs that themselves display the full paradigm differentiation. Spanish marks a past/non-past distinction. Past events are marked whereas present tense forms can express both present and future events. The three most frequently used forms traditionally described as conveying temporal distances prior to the moment of speech are: present perfect (recent past: he cantado), preterite (distant past: canté) and pluperfect (past in the past: había cantado). Supplementary verb inflections mark additional temporal relations and aspectual contours of past actions: imperfect (cantaba), progressive with an imperfect auxiliary (estaba cantando), progressive with a perfective auxiliary (estuve cantando) and prospective imperfect (iba a cantar).Footnote 1

Grammarians have traditionally described the Spanish preterite as referring to completed past situations, and the present perfect as establishing a relation of simultaneity with the present, be it because the referred past action has not yet ended, or because its consequences are still visible or relevant to the present situation (Bello, Reference Bello1984). This distinction, however, is not equally realized in all Spanish varieties. Contrastive studies of adult Peninsular vs. American Spanish have reported a preferred use of preterite forms in American Spanish as opposed to a more prominent use of present perfect in SpainFootnote 2 (Moreno de Alba, Reference Moreno de Alba1993). The use of the present perfect has adopted an increasing perfective meaning in Spain, so that it is more often used to refer to completed past events. In contrast, in nearly all American Spanish varieties most past events are reported via the preterite because the present perfect has adopted an increasing present meaning that results in its restricted use for continuative actions; those that continue to be relevant in the present (De Jonge, Reference De Jonge1995).

In narrative discourse, most Peninsular and American Spanish varieties use perfective forms (present perfect or preterite) to report foregrounded events that advance the plot. Imperfective forms usually convey continuous, iterative or habitual actions. Even though imperfective forms might appear throughout a narrative, this tense is most frequently used for setting or background information (Silva-Corvalán, Reference Silva-Corvalán2004). Spanish also encodes temporal information in a variety of lexical items (adverbs, connectives).

Verbs

Despite the large body of research on verb development in Spanish, the expression of temporality, which requires a broader analytical lens, has been minimally explored. One crucial contribution is Berman & Slobin's (Reference Berman and Slobin1994) cross-linguistic study of children's narratives starting at age three. In their analysis of the Spanish corpora, Sebastián & Slobin (Reference Sebastián, Slobin, Berman and Slobin1994: 242) report that:

Almost every combination [of tense/aspect forms] is attested in the 3-year-old sample from Spain, and comparison with the Chilean and Argentinean data convinces us that we did not chance upon a particularly precocious sample in Madrid.

These researchers describe Spanish-speaking children as precocious in their use of tense/aspect inflections and suggest that the complexity of the Spanish system, far from impeding its acquisition, seems to facilitate it.

This abundance of forms at such an early age leads to the following question: How do young Spanish-speaking children's linguistic skills progress so that by three years of age they are able to use almost the full array of tense/aspect forms in narration?

Spanish-speaking children as young as two years of age start using verb inflections to express temporal contrasts (Fernández, Reference Fernández and López Ornat1994; Gathercole, Sebastián & Soto, Reference Gathercole, Sebastián and Soto1999). A piecemeal – as opposed to ‘across-the-board’– acquisition has been documented as ‘the Spanish-speaking child moves step by step towards productivity by learning forms verb by verb’ (Gathercole et al., Reference Gathercole, Sebastián and Soto1999: 30). Verb semantics has also been invoked as an influential variable contributing to an early yet selective acquisition of past tense inflections (Jackson-Maldonado & Maldonado, Reference Jackson-Maldonado, Maldonado, Rojas Nieto and de León Pasquel2001).

Despite the early acquisition and diversity of forms documented, several studies have reported minimal presence of past tense forms before age three (González, Reference González1980; Peronard, Reference Peronard1987; Morales, Reference Morales1989; Johnson, Reference Johnson and Pérez Pereira1996). According to González, (Reference González1980: 8), his participants aged 2 ; 6 produced the imperfect, imperfect progressive and pluperfect ‘too infrequently to warrant discussion’. Morales (Reference Morales1989), in her cross-sectional study of Puerto Rican children aged two to six, concluded that narrative via past tense verbs does not emerge until after age three. More radically, Johnson (Reference Johnson and Pérez Pereira1996) reported minimal productivity of verb tenses up to age four.

In sum, on the one hand studies on acquisition report an early emergence of past forms offering analyses that take into account the communicative function, the interactional context or verb semantics early in development (Fernández, Reference Fernández and López Ornat1994; Gathercole et al., Reference Gathercole, Sebastián and Soto1999; Jackson-Maldonado & Maldonado, Reference Jackson-Maldonado, Maldonado, Rojas Nieto and de León Pasquel2001, respectively). On the other hand, studies that focus on the subsequent use of past tense from ages two to three highlight the scarcity or even absence of these inflections. These latter studies are based on cross-sectional samples, and do not take into consideration the larger context. In particular, discourse genre and function are generally overlooked. In contrast, Sebastián & Slobin (Reference Sebastián, Slobin, Berman and Slobin1994) report the abundance of forms by age three in a specific discourse: narrative. The present study seeks to clarify these contradictory results by closely following the use of past tense verbs in intra-conversational narratives from two to three years of age.

Temporal/aspectual markers

Most research on temporal/aspectual markers before age three in Spanish offers lists of isolated forms without considering the discourse context or functions. One exception is Sebastián, Slobin and colleagues, who found that three-year-old narrators produced aspectual markersFootnote 3 ya ‘already’ and otra vez ‘again’ to express result and recurrence, respectively; general sequencers entonces ‘then’, luego ‘after’; a few anaphoric expressions; and the subordinating conjunction cuando ‘when’ to mark immediate anteriority or simultaneity (e.g. Sebastián & Slobin, Reference Sebastián, Slobin, Berman and Slobin1994). Other studies report the early appearance of ya, ahora, mañana; at least one sequencer entonces, después or luego; the conjunction cuando; some deictic adverbs (e.g. ayer, hoy); and a few phrases expressing reference time (e.g. en la mañana, hace tiempo) (González, Reference González1980; Hernández Pina, Reference Hernández Pina1984) but without offering any further analysis on discourse context.

Verbs and temporal markers

To my knowledge, only one study – Eisenberg (Reference Eisenberg1985) – has described concurrent grammatical and discourse development of temporality for children younger than three years of age in Spanish. Eisenberg contributed a valuable description of the emergence of temporally displaced talk in a longitudinal analysis of two Spanish-speaking children from approximately two to three years of age. She summarized the developmental changes into three phases. In the first phase, the fact that Spanish-speaking children and adults were talking about the past was established by the adults' use of tense forms, while children's contributions were simple nominals or infinitives. Children produced a few verbs in the context of simple adult-initiated routines. In the second phase, children became less dependent on adults' scaffolding with most utterances containing past tense verbs. Finally, in the third phase, children spontaneously initiated past talk, including adverbs and conjunctions. Adverbs and connectives were scarcely used before age three, with the latter being used initially as empty links in descriptions of past events, and only later used ‘appropriately’ (Eisenberg, Reference Eisenberg1985: 192).

Eisenberg documented a considerable advance in discourse autonomy and an increasing frequency of grammatical forms. However, she did not explore specific verb tenses, distinct temporal markers or discourse functions and how they relate to each other. Eisenberg's study raised a still unanswered question: How do changes in discourse skills relate to grammatical development over time from ages two to three? This study intends to take Eisenberg's analysis one step further to investigate interrelationships among lexico-grammatical and discourse skills.

Theoretical proposals

In the study of the emergence of temporality, whether young children are cognitively and linguistically able to refer to the past has been a controversy for a long time. Piaget concluded that young children were cognitively too immature to handle the temporal concept of pastness before age six (Piaget, Reference Piaget1969). However, Halliday (Reference Halliday1975) reported that his son Nigel at 1 ; 6 would spontaneously narrate past happenings to a familiar adult via rudimentary linguistic means. While research on productivity of verb tenses has reported an early acquisition of the present vs. past tense contrast, whether these tense inflections refer to a deictic past or not has remained controversial. Shirai & Miyata (Reference Shirai and Miyata2006) have clarified this discussion by documenting a distinction between initial contrastive use of past tense and use of deictic past. In their longitudinal analysis of Japanese children between ages 1 ; 2 and 2 ; 5, these authors found that the contrastive use of past tense preceded the use of deictic past.

The development of temporality has been further illuminated by Katherine Nelson's and Richard Weist's contributions. Based on her research on Emily's narratives and her script data, Nelson (Reference Nelson and Nelson1989; Reference Nelson1996) raises three developmental claims about the mutual influence of event knowledge and language use. First, she argues that in the acquisition of tense inflections ‘language makes salient a type of relation that was not previously apparent in the child's nonlinguistic conceptual representations’. She points out that before acquiring the tense system, children may only distinguish between now and not-now (Gerhardt, Reference Gerhardt and Nelson1989) or might express exclusively actions related to present circumstances. Via the use of tense inflections consistently associated with distinct time points, children learn the conceptual distinction of past, present and future (in languages that make such distinctions). Her second claim points to the inverse effect of cognitive representation facilitating language acquisition. Nelson argues that ‘nonlinguistic experientially derived’ event representations – including notions of sequence, duration and frequency – facilitate the acquisition of linguistic forms that express these relations. In Nelson's words ‘[i]n this case, language makes explicit knowledge that was previously implicit’ (1996: 289–90). Finally, she points out that language makes accessible abstract concepts that cannot be acquired through experience, in particular conventional markings of time, such as hours, days, months, etc. Conventional time markers require explicit instruction and are typically learned at school.

Weist & Buczowska (Reference Weist and Buczowska1987) suggest a four-phase development of temporal reference, based on Smith's (Reference Smith1980) proposal. Weist and Buczowska's model places the first phase at the emergence of language production, which they describe as restricted to the ‘here-and-now’ of speech time (ST). In the second phase, children begin to mark events as past, present or future in relation to ST via tense inflections, in other words, event time (ET) becomes independent from ST, e.g. Tower fell down. In the third phase, between about 2 ; 6 and 3 ; 0, temporal/aspectual markers emerge, and consequently children start conveying reference time (RT). At this phase, however, RT can only be concurrent with ET, e.g. When I was at school [RT], I cried [ET]. In the fourth phase, not until 3 ; 6 or 4 ; 0, ST, ET and RT can be related freely, establishing simultaneous, anterior or posterior relations among the three, e.g. I cried [ET] before I went to school [RT]. This account comprises not only a gradual inclusion of more linguistic time points, but an increasing flexibility and complexity in the relationships potentially established among them.

Despite the complementary nature of Nelson's and Weist's proposals, there are some points of controversy. In line with Weist's model, previous studies on English have reported that temporal markers are not acquired until after tense contrasts are productively used (Bloom, Lifter & Hafitz, Reference Bloom, Lifter and Hafitz1980). Nevertheless, Nelson's (Reference Nelson and Nelson1989) analysis showed that Emily's crib monologues displayed temporal adverbials at the same time as the tense system was being organized. In addition, Nelson foregrounds the role of discourse, highlighting Weist's exclusive focus on sentence-level connections (Nelson, Reference Nelson and Nelson1989: 301). Nelson argues that by looking at entire narratives, instead of isolated sentences, it is possible to find not only sequential relations among events, but also ST–ET–RT relations much earlier than Weist's model indicates. In fact, she argues that children's struggles to order events drive them to master tense usage and temporal markers (Nelson, Reference Nelson and Nelson1989: 304–305).

Whether Spanish-speaking children produce temporal markers in synchrony with or only after the productive use of the tense system is still an unanswered question. Whether Spanish-speaking children follow Weist's model or are able to produce more precocious combinations of time perspectives earlier in discourse also remains to be explored. This study examines the synchronous and asynchronous relationships among different temporal skills at the grammatical and discourse levels to relate the findings to the theoretical claims just reviewed.

METHODS

The design involved comparative case studies of two young Spanish-speaking children followed longitudinally during a one-year span. Children were recorded in spontaneous parent–child conversations from two to three years of age. Both children were monolingual speakers of Spanish, were the first-born and only child in their families, and came from middle-class households.

María

María's longitudinal dataset was published by López Ornat, Fernández, Gallo & Mariscal (Reference López Ornat, Fernández, Gallo and Mariscal1994) and is available in CHAT format through the CHILDES Database (MacWhinney, Reference MacWhinney2000). María is a girl from Madrid, Spain. From age one to age four, María was videotaped biweekly in sessions of approximately thirty minutes. Sessions took place at home during spontaneous interactions with familiar adults. For this study, the twelve published sessions from age 2 ; 0 to 3 ; 1 were selected for analysis.

Isabella

Isabella was audio-recorded every fifteen days in sessions of about thirty minutes to an hour. Sessions took place at home during spontaneous interactions with her parents, who are from Latin America (father is from San Juan, Puerto Rico and mother is from Lima, Perú).Footnote 4 Isabella's dataset was fully transcribed following CHAT conventions. It comprises eleven time points from age 2 ; 2 to age 3 ; 3.

Defining a narrative: data selection

Labov & Waletzky (Reference Labov, Waletzky and Helm1967: 28) defined a minimal narrative as a sequence of two restricted [independent] clauses which are temporally ordered. Starting with Peterson & McCabe (Reference Peterson and McCabe1983), this characterization has guided most linguistic approaches to narrative development. As Bamberg (Reference Bamberg1997) has pointed out, this definition implies a minimum requirement of two events sequentially ordered and it is ubiquitously assumed that it requires predicates marked by tensed verbs. After examining María's and Isabella's language exchanges, the need to stretch the boundaries of this definition became evident. In child language there is a long history of including proto-forms in one's analysis, e.g. speech acts (Bates, Camaioni & Volterra, Reference Bates, Camaioni and Volterra1975), or grammatical markers (Brown, Reference Brown1973). Including predecessors of later more advanced forms is needed to understand the origins of narratives. For this study intra-conversational narrativesFootnote 5 were defined as consisting of at least two contiguous and topically related child utterances that referred to any two components of a past or fictional happening (event, setting, evaluation and/or speech). This expanded definition includes proto-narratives – i.e. narratives that refer to a temporally displaced happening even without containing a clear tensed verb – and encompasses both personal and fictional renditions of events.

Narrative segments were identified in transcripts using the GEM program from CLAN (MacWhinney, Reference MacWhinney2000). Shifts from and to ‘here-and-now’ talk were especially helpful in identifying narrative boundaries, as were explicit elicitation attempts by parents. Narratives were coded for lexico-grammatical and discourse measures. The measures reported here comprise a subset of the original coding system (for further details see Uccelli, Reference Uccelli2003).

Discourse measures

At the discourse level, narratives were divided into narrative clauses, which were coded for narrative components following highpoint analysis (Peterson & McCabe's (Reference Peterson and McCabe1983) adaptation of the Labovian narrative analysis):

event clauses: report actions that constitute the backbone of the story and serve to advance the plot.Footnote 6

setting clauses: offer referential information about space, time, characters and general background information. temporal setting clauses are of particular interest in this study.

evaluative clauses: provide the narrator's stance towards the narrated events via qualifications, explanations, expressions of emotions and emphatic assertions, among others.

Additional narrative components include speech clauses which express characters' reported or indirect speech, and openings and closings which mark the beginning and end of narratives (see Appendix).Footnote 7 Mean frequencies of narrative components were generated.

Inter-rater reliability for narrative components was estimated using Cohen's kappa statistics (Bakeman & Gottman, Reference Bakeman and Gottman1997). A native Spanish-speaking researcher independently coded fifteen percent of the narratives in each corpus. Cohen's kappa statistic was 0·94 for narrative components.

Lexico-grammatical measures

frequency of verbs (types and tokens): verbs were coded for verb stem, person and tense.

frequency of temporal/aspectual markers (types and tokens): adverbs, connectives and other temporal expressions were identified.

RESULTS

Discourse measures

Narrative length

Tables 1 and 2 display, for each time point, the total number of narratives produced, and the total frequencies of basic narrative units. Overall narrative length increased on average for both girls over time, in accordance with the positive association between narrative length and age reported in the literature on children's personal narratives (Peterson & McCabe, Reference Peterson and McCabe1983). However, it is worth highlighting that narratives exhibited a variety of lengths throughout most time periods with short and long narratives present at both ends of the data collection sessions. It is also noticeable that Isabella tended to produce somewhat longer narratives.

TABLE 1. María's data: raw frequencies of general narrative measures

* Three sessions were combined due to the low incidence of narratives in each of them. From now on this time period which combines data from ages 2 ; 6, 2 ; 7 and 2 ; 8 will be referred to using the older age: 2 ; 8.

TABLE 2. Isabella's data: raw frequencies of general narrative measures

María's progress appears somewhat distorted towards the end of the year by the fact that she was disinclined to talk at 3 ; 1, after she had been engaged in extended autonomous narrative at 2 ; 9 and 2 ; 11 (see María's narrative under ‘Diversity and integration of temporal/aspectual markers’). In fact, María's last session offers an unusually poor performance overall, probably as the result of the family being on vacation. A quote from her mother confirms María's reluctance to talk during this session:

MOTHER: Hoy no quieres hablar nada, ¿eh?

‘Today you don‘t want to talk at all, do you?’

Thus, I will not interpret this last performance as a developmental regression, but just as the result of external circumstances affecting María's motivation to narrate.

Narrative components

Figures 1 and 2 show the frequency of event clauses as compared to setting and evaluation clauses. For María, narratives initially consisted mostly of elicited setting information with a range of one to two events per narrative and minimal evaluation. At 2 ; 4, the frequency of event clauses increased considerably, while setting clauses became less frequent. In the last three months of her third year, the frequencies of event, setting and evaluation clauses per narrative became more balanced, with events constituting a third of all main narrative components (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1. MARIA: Frequency of major narrative components.

Fig. 2. ISABELLA: Frequency of major narrative components.

For Isabella, narratives also consisted initially mostly of elicited setting information, but from the beginning Isabella's narratives displayed a higher number of event clauses than María's. Over time, setting and evaluation became more balanced, but event clauses continued to dominate Isabella's narratives throughout the year and increased considerably in the last months (see Figure 2).

As repetitions of the same event were numerous in the data, Table 3 offers the average frequencies of distinct reported events per narrative produced over time for each girl. In this table, proto-narratives (narratives with one or zero events) were excluded. There was a clear progression for both girls towards representing a larger number of distinct events in their narratives. The fact that children this young can incorporate as many as seven events in their narratives is impressive. Of course, we need to remember that these were heavily scaffolded intra-conversational narratives and, for the vast majority, relying on shared knowledge between the child narrator and the interlocutor. However, all events included in this table were either spontaneously produced or elicited without being previously mentioned either by the child herself or her interlocutor, and thus all constituted instances of new information provided by these young narrators. Children produced two-event narratives from the beginning of their third year and included, over time, on average, as many as four (María) or seven (Isabella) events per narrative. They engaged in talk not only about the immediate past, but also about events that occurred hours or even days before the moment of speech from the beginning of data collection. Indeed, these narratives about a distant past comprised the most frequent narrative discourse throughout the entire third year covered by both datasets (for details on the uses of past tense forms to refer to immediate or distant past see Uccelli (Reference Uccelli2003: 61)). Thus, in the context of spontaneous conversations with familiar adults, these children referred to past events starting as young as age 2 ; 0.

TABLE 3. Frequency of reported events (proto-narratives are excluded)

Lexico-grammatical measures

Past-tense verbs

As shown in Figures 3 and 4 for María and Isabella respectively, initially the frequency of past tense verbs increased at a very slow pace. Most sessions displayed, on average, a token frequency of one to three past tense verbs per narrative, only two or fewer verb stems, and basically one verb form type per stem type, signaling minimal morphological variety of past tense usage.Footnote 8 A salient change in the production of past tense verbs emerged later, starting at age 2 ; 9 for María and age 2 ; 10 for Isabella. During these sessions, the observed trajectories displayed a sudden growth spurt, with narratives reaching averages of 12·1 and 9·1 past tense verbs per narrative, respectively. Similarly, the frequencies of verb form types and stems also increased considerably and the gap between these two frequency trajectories widened for the first time for both girls. During these last months there were always more than three verb form types per narrative and in some sessions as many as five, and the number of different verb stems fluctuated between 2·5 and 3·6 per narrative.

Fig. 3. MARIA: Past tense verbs: tokens, form types and stems per narrative.

Fig. 4. ISABELLA: Past tense verbs: tokens, form types and stems per narrative.

This substantial increase in tokens, verb form types and stems per narrative reveals a more advanced mastery of past tense morphology in narrative production during these last months. The higher morphological flexibility displayed by these narratives resulted in large part from a higher diversification in past tense/aspect combinations per narrative.

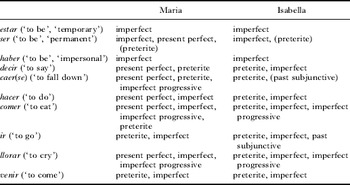

Interestingly, not only did both girls produce mostly the same forms of past tense/aspect inflections, but also the order in which they incorporated new forms into narrative discourse tended to coincide. Table 4 offers a summary of María's and Isabella's diversity of past tense/aspect forms divided into three phases. The use of past tense/aspect can be summarized as a first phase characterized by minimal presence or diversity of past tense verbs; a second one, in which most narratives displayed past tense verbs and a few emerging contrasts between perfective and imperfect past forms; and a third one, in which all narratives displayed a comparably higher frequency of past tense verbs, and exhibited contrasts between perfective/imperfect and progressive/non-progressive past forms, with single narratives including as many as four distinct tense/aspect inflections.

TABLE 4. Diversity of past tense/aspect forms: three phases

* imperfect: During Phase 1, the imperfect was expressed only by a few verb forms always used in the same form (estaba, era, tenía) and in no other tense.

Towards the end of their third year, these young narrators, in addition to a sustained use of past tense forms, selected from among a variety of inflections that offered supplementary aspectual information, i.e. various perspectives on the course of past actions. The same forms were generally produced by both girls, with the most salient difference being the preference for either present perfect (María) or preterite (Isabella) associated with each girl's regional variety. While not all past forms of the Spanish verbal paradigm were present in these data, a significant proportion of them was produced. In line with Sebastián & Slobin's (Reference Sebastián, Slobin, Berman and Slobin1994) findings, only the perfective progressive was absent from these performances (the pluperfect – or past perfect – was produced once by Isabella).

To illustrate the types of verbs children used with past tense inflections in their narratives, the fifteen most frequently used verb stems were identified for each child. Interestingly, ten out of the fifteen verb stems were the same for both children. Table 5 displays these ten verb stems along with the past tense inflections they displayed throughout the year.

TABLE 5. Most frequent verb stems with past tense inflections in Maria's and Isabella's intra-conversational narratives

note: Parentheses indicate infrequent occurrences (three or less) of a specific verb stem/past tense combination.

These verb stems refer either to perceptually salient actions or to states. All stems referring to perceptually salient actions displayed at least two – and up to four – distinct past tense inflections that were eventually used successfully to mark aspectual contrasts. Recent research suggests that perceptually salient words, with higher imageability and individuability, tend to be learned before more abstract ones (Hirsh-Pasek & Golinkoff, Reference Hirsh-Pasek and Golinkoff2006). Perhaps, perceptual salience – combined with frequency and discourse context –contributes also to the initial conceptualization of aspectual contrasts within past tense inflections. Interestingly, the more abstract state verbs, despite their high frequency, either were used exclusively in one past tense form (estar, haber – imperfect) and/or still displayed unconventional uses of present tense in past-anchored narratives at the end of data collection (ser, estar). Whether this is related to their less perceptually salient nature, however, could only be confirmed by further research on the role of imageability in tense/aspect acquisition.

Differences in language varieties

The preferential use of either present perfect or preterite as the initial and most frequent form to express pastness (both immediate and distant past) in narratives was related to language patterns in each girl's language variety. This was confirmed by a brief analysis of child-directed talk. As shown in Table 6, the divergent preferences of primary past perfective form (present perfect for María; preterite for Isabella) were associated with the frequencies of these forms in parental child-directed speech. Higher frequencies of exposure to present perfect vs. preterite forms resulted from patterns of use characteristic of each child's Spanish variety combined with the frequency of participation in certain narrative subgenres. For further analysis see Uccelli (Reference Uccelli2003).

TABLE 6. Frequencies of past tense/aspect forms in parental speech directed to children

Temporal/aspectual markers

In Tables 7 and 8 the order of markers in the first column follows the order of appearance in the data for each girl. From the total of twenty-six types observed, ten types were produced by both girls. In line with previous research, the most common shared markers were cuando ‘when’, entonces ‘then’, ya ‘already’, después ‘then/after’ and otra vez ‘again’.

TABLE 7. María's temporal/aspectual markers by age and order of appearance

TABLE 8. Isabella's temporal/aspectual markers by age and order of appearance

Even though temporal/aspectual markers were not present in all narratives, both girls were able to convey a range of temporal/aspectual meanings via a limited but varied set. The most common temporal/aspectual meanings conveyed by both girls were: temporal relations of posteriority, anteriority and simultaneity; and aspectual meanings of recurrence, completion and achievement. However, the order in which these forms and meanings made their appearances in narrative clauses varied. During the initial exploration of certain form/meaning correspondences, these girls preferred contrasting entry points. María initially used temporal connectives and adverbs in syntactically accurate contexts but without clear meanings. From this entry point – characterized as ‘use before meaning’ (Nelson, Reference Nelson1996) – María progressed towards expressing clear temporal meanings via the previously empty forms. Isabella, on the contrary, seemed to go from meaning to form, using meaningful aspectual expressions in isolated syntactic contexts, gradually incorporating these forms into increasingly complex sentences. Her first temporal setting clauses included pseudo-subordinated clauses that only later included the connective in a full-fledged sentence:

MOTHER: ¿Cuándo fue eso?

‘When was that?’

CHILD: Que vino Nico.

‘That Nico came.’

MOTHER: ¿Cuando vino Nico?

‘When Nico came?’

CHI: Sí.

‘Yes.’

Developmental co-occurrences

When looking simultaneously at the analytical dimensions of past tense usage and narrative components, it became evident that the progress in the use of past tense inflections occurred mostly in the context of EVENT Footnote 9 clauses (as opposed to evaluation or setting). More interestingly, once the consolidation in the use of past tense inflections to report EVENTS was achieved, an explosion of forms, both in frequency and diversity of tense/aspect inflections, temporal markers and temporal setting occurred. During the first months children would report EVENTS via unclear, non-linguistic or non-past forms, but eventually both started using a past tense form for every single reported EVENT (although this was still not the case for setting or evaluation). At this point children seem to have established a connection between past foregrounded EVENTS and perfective past tense. This crucial linguistic/cognitive achievement constituted a milestone that seemed to facilitate the acquisition of subsequent linguistic forms to express temporal relations.

In Figures 5 and 6 the lines labeled PAST TENSE EVENTS display the number of EVENT clauses with past tense verbs divided by the total number of EVENT clauses. If all EVENTS were reported via a past tense verb, a straight line would indicate a ratio of one-to-one for EVENTS and past tense verbs. The fact that the line does not reach one during the early months reflects children's use of other means to report EVENTS, namely non-verbal resources (i.e. enactment, sound effects), unclear forms and non-past forms (i.e. present tense, non-personal forms). When the line becomes solid, the graph shows the point at which children achieved the consolidation of past tense to report EVENTS. From that point on, the gaps observed correspond to narratives anchored in the present tense, but all other narrative EVENTS were reported via past tense. As these figures show, once EVENTS were consistently reported via past tense verbs, the production of temporal markers and temporal setting exhibited unprecedented increases. These figures illustrate the explosion of temporal forms occurring during the last months of the third year simultaneously or subsequently to the achieved consistency of past tense to report EVENTS. Not only did temporal markers and temporal setting clauses increase, but also the variety of past tense/aspect inflections increased considerably, as explained above. Although the ages at which this consolidation was achieved varied – between ages 2 ; 4 and 2 ; 5 for María and ages 2 ; 8 and 2 ; 9 for Isabella – general patterns of co-occurring or immediately subsequent developmental changes in the production of other means to express temporality coincided for both girls.

Fig. 5. MARIA: Grammatical and discourse skills used in expression of temporality.

Fig. 6. Isabella: Grammatical and discourse skills in the expression of temporality.

Developmental co-occurrences across- and within-child can be summarized in three phases: (1) a preferred but inconsistent use of perfective past tense for EVENT clauses with minimal presence of either empty connectives (María) or aspectual markers (Isabella); (2) a move towards consistent use of perfective tense for EVENT clauses and mostly present tense to report evaluation; and finally (3) an explosion of forms characterized by a consistent use of past tense for EVENT clauses, an increasing, though not always consistent, use of past tense for setting and evaluation, and a considerable increase in frequency and variety of past tenses and temporal/aspectual markers, as well as the emergence of temporal setting. Among the different skills displayed over time, the consolidation of the use of past tense to report EVENT clauses marked an important developmental point for both girls that triggered an explosion of co-occurring developmental skills.

The following section describes these three phases, illustrating them with examples.

THREE DEVELOPMENTAL PHASES: A QUALITATIVE PORTRAYAL

Phase 1: alternative means to report past events

The preference for past tense usage to report narrative EVENTS was evident for both girls even at this early phase. In seven out of ten sessions for María, and in nine out of eleven sessions for Isabella, more than 60% of all EVENT clauses were reported via perfective past tense. Despite this overall preference, the use of past tense to report EVENTS was far from consistent. During these first months approximately one-third of all EVENTS were reported via: (a) non-verbal means – such as gestures or sound effects; (b) unclear forms; or (c) non-past verb forms – present tense verbs or non-personal verb forms. Here are some examples.

(a) Non-verbal events

These elicited narratives include gestures and sound effects as strategies for conveying events. Probably, the lack of a lexical item to refer to the targeted actions was the underlying cause for using these non-verbal means.

FAT: ¿Qué le cantaron a Ludovico hoy?‘What did you sing to Ludovico today?

CHI: beye+tuyu, beye+tuyu, beye+tuyu beye tuyu, beye tuyu, beye tuyu

[% child sings].[% child sings].

CHI: 0 [child claps].0 [child claps]. ▸▸ non-verbal event

FAT: ¿Y todos aplaudieron al final?‘And everybody clapped at the end?’

¿Y qué hizo Ludovico?‘And what did Ludovico do?’

CHI: [child blows as if blowing a candle].[child blows]. ▸▸ non-verbal event

FAT: ¿Cómo se dice eso?‘How do you say that?’

CHI: xx (UNC) veya [:vela].‘xx (UNC) candle.’

FAT: Sopló las velas.‘[He] blew the candles.’

¿Cuántas velas había?‘How many candles were [there]?’

CHI: Una.‘One.’

FAT: Una.‘One.’

CHI: aiendo [=?comiendo] (UNC, PROG?)‘aing [=? eating] (UNC, PROG?)’

tota [:torta], allí tota [:torta].‘cake, there cake.’

MOT: ¿Comiste torta?‘You ate cake?’

CHI: Sí.‘Yes.’

(Isabella, 2 ; 2)

Isabella found alternative strategies to convey meanings that still surpassed her lexico-grammatical skills. Through non-verbal enactments and sound effects she was able to report distinct components of a past anecdote. This narrative exchange also illustrates the opportunities for learning verbs in conversational narratives. In most instances, immediately after the enactment, the interlocutor produced the corresponding past tense verb phrase providing the linguistic forms that matched the communicative intent of the child.

(b) Unclear forms

The following example displays two unclear forms in the co-narration of a vicarious experience.

CHI: Me ágo (UNC).‘[I] xx (UNC).’

MOT: ¿Te ahogas? ¿Quién te ha enseñado a ti?‘Did you choke? Who has taught you?’

CHI: No. Con un camelo [:caramelo].‘No. With a candy.’

MOT: ¿Con un caramelo, te ahogas?‘With a candy you choke?’

CHI: Sí. Estaba (ipfv) una niña, ¿a qué sí?‘Yes. There was (ipfv) a girl, right?’

MOT: Sí. ¿Dónde?‘Yes. Where?’

CHI: No sé. En misa.‘I don't know. At Mass.’

MOT: Sí.‘Yes.’

CHI: En misa.‘At Mass.’

MOT: Hay una niña que por poco se ahoga,‘There is a girl that almost chokes,

¿verdad hija ?right daughter?’

CHI: Sí. Co, co u camelo.‘Yes. Wi, with a candy.’

MOT: Fíjate, creo que‘See, I think that

sólo ha oído la palabra ahogo una vez.[she] has heard the word choke once.’

CHI: No! Una ni, una niña, ¿a qué sí?‘No! A gi, a girl, right?’

MOT: Claro.‘Of course.’

CHI: Claro. Se se sa solo (UNC) a llorar.‘Of course. [She] xx (UNC) to cry.’

MOT: Se puso a llorar.‘[She] started to cry.’

CHI: Sí.‘Yes.’

(María, 2 ; 2)

The forms María used to report EVENTS were not past tense verbs, but unclear forms that her mother translated into conjugated verbs.

(c) Use of non-past forms

Non-personal forms (i.e. progressives and infinitives) and present tense were also used to report events during this phase:

FAT: Di lo que has hecho a mamá‘Tell what [you] have done to your mother.’

[% child is silent].[% child is silent].

Venga, díselo ¿qué has hecho?‘Come on, tell her what have [you] done?’

CHI: 0 [% child makes an angry face].0 [% child makes an angry face].

FAT: ¿Qué has hecho?‘What have you done?’

CHI: ompiendo [:rompiendo] (PROG)‘breaking (PROG)

las plantas.the plants.’

FAT: ¿El qué?‘What?’

CHI: Las plantitas.‘The little plants.’

FAT: ¿El qué?‘What?’

¿Qué le has hecho a las plantitas?‘What have you done to the little plants?’

CHI: Aquí, en el suelo.‘Here on the floor.’

FAT: Claro, ¿qué ha hecho mamá?‘Of course, what did mom do?’

CHI: O [?] regaña (pres).(…)‘Or [?] [she] scolds (pres). (…)’

(María, 2 ; 1)

CHI: Beya [:Isabella] peya [:pega] (pres)‘Beya [:Isabella] hits (pres)

atí [:así] Daneya atí [:así] mano.[like] this Daneya [like] this hand.’

MOT: ¿En la mano? ¿Quién pegó?(…)‘On the hand? Who hit?’

CHI: A mí.‘Me.’

MOT: ¿Daniela?‘Daniela?’

CHI: No a mí.‘Not me.’

MOT: ¿Tú le pegaste? ¿Por qué, gorda?‘You hit her? Why, dear?’

CHI: Lloyó [:lloró] (pfv).‘Cried (pfv).’

(Isabella, 2 ; 4)

Progressive forms, such as rompiendo ‘breaking’, convey information about the course of the actions, i.e. the aspectual nature of the actions, rather than information about their temporal location. María might be focusing on the durative/iterative aspect of the action of breaking, instead of locating it in the past. In the cases of regaña ‘scolds’ and pega ‘hits’ it is harder to speculate about the motivation. Notice that in other cases, such as lloró ‘cried’, the past tense is used. It seems that at this phase, children were still struggling to convey basic meanings without yet making consistent choices of tense.

Additional strategies

Two additional resources were identified during this phase: (1) the child's assent in response to her interlocutor's yes/no questions about a past event (a conversational pattern reported by Eisenberg (Reference Eisenberg1985) ); and (2) the use of speech, either in the form of actual ‘quotes’ or in the form of songs that took place at the moment of the reported anecdote. These strategies remained part of children's narrative performance throughout the year but later were combined with full-fledged event clauses and used mostly as additional support instead of main carriers of narrative content. In the next example María conveyed almost the entire narrative via speech clauses that reported what was said at the moment of the anecdote (speech clauses are underlined). Only the last unclear clause is not a speech clause. Initially her aunt prompted María for an event clause, but the child responded with a speech clause. Her father continued the interaction via a general request, but then he followed the child's lead and prompted her for a speech clause.

AUNT: ¿Qué hiciste al Yayito con la tele?‘What did you do to Yayito with the TV?’

CHI: Quítalo (imp).‘Stop it (imp).’

FAT: A ver, cuéntame.‘Let's see, tell me.’

CHI: Págalo [:apágalo] (imp).‘Turn it off (imp).’

FAT: Cuéntamelo más.‘Tell me more.’

CHI: Págalo [:apágalo] (imp).‘Turn it off (imp).’

FAT: ¿El qué?‘What?’

CHI: Págalo (imp) la tele Yayito.‘Turn it off (imp) the TV Yayito.’

FAT: ¿Por qué? ‘Why?’

CHI: Poque sí.‘Just because.’

FAT: ¿Y qué dijo el Yayito?‘And what did Yayito say?’

CHI: Pos que no.‘Well that no.’

FAT: ¿Y tú? ¿Y tú qué hiciste?‘And you? What did you do?’

CHI: xx (UNC) en e culo.‘xx (UNC) on the butt.’

(María, 2 ; 1)

By directly quoting direct speech without even using a verb of diction to introduce it, children were able to advance the plot adding new developments to the anecdote. These strategies illustrate children's search for alternative resources to report meaning that might still surpass their grammatical skills.

During this phase, despite some unanalyzed uses of imperfect, such as estaba, setting and evaluation clauses were conveyed mostly via verbless clauses that tended to occur as responses to elicitation questions:

AUNT: ¿Dónde has estado este verano? (…)‘Where have you been this summer?’

CHI: En Galisia [:Galicia].‘In Galicia.’

AUNT: ¿Y qué tal lo has pasao?‘And how was it?’

CHI: Bien.‘Good.’

(María, 2 ; 1)

In conclusion, at this early phase, even though the majority of events were reported via past tense verbs, approximately one-third of them were expressed via non-verbal means, unclear forms, non-personal forms and present tense verbs. Evaluation and setting were mostly conveyed via verbless clauses, and were often prompted by adult questions.

Phase 2: transition towards consistency

This transition phase is characterized by progress towards the consolidation of the use of past tense verbs to report events. It constitutes a transitional moment in which both girls still produced some narratives without tensed verbs, yet also produced for the first time a few narratives with as many as seven past tense verb form types. There is one instance of a non-personal form produced by each girl to report an event, signaling the transitional nature of this moment. From 2 ; 5 on for María, and from 2 ; 8 on for Isabella, all EVENT clauses were consistently reported via tensed verbs and mostly via past tense verbs.

The distinction between perfective and imperfective started to be evident with just a few but meaningful uses of imperfect to mark past actions' contours, in particular, the aspectual meanings of duration and iteration:

Durative: Caperucita se iba (ipfv) por el bosque. (María, 2 ; 5)

‘Little Red Riding Hood was leaving through the woods.’

Iterative: Tiraba (ipfv) todo a [:al] piso. (Isabella, 2 ; 8)

‘[She] was throwing everything to the floor.’

Durative/Iterative: Comía (ipfv) todo. (Isabella, 2 ; 8)

‘[He] was eating everything.’

Within this phase each girl produced one contrastive aspectual use, i.e. the same verb stem in perfective and imperfective form. Isabella used the forms sonó and sonaba in a conventional manner to refer to a completed punctual action and an incomplete durative action, respectively. María's aspectual contrast with constiparse was not clear because she used se ha constipado and se constipaba in an invented plot to refer to what seemed foregrounded punctual events. Thus, a few functional uses of the imperfect co-occurred with some less clear cases. The functional instances, though, seem to anticipate that the first aspectual distinction to emerge within a past perspective was perfective vs. imperfective. It is important to highlight, however, that isolated contrastive uses do not imply a productive mastery of the imperfect tense.

Between ages 2 ; 5 and 2 ; 8, both girls produced the alternative form of perfective past (preterite for María,Footnote 10 and present perfect for Isabella). For Isabella it was only a single instance, however for María this phase constituted the emergence of the use of the preterite in her fictional narratives. Her uses reflect a still incipient presence of the preterite: only four tokens were identified during this phase, most of them produced in the context of what seems a memorized minimal story.

Verbless clauses still constituted an important presence, but now as many as 50% of evaluation clauses (for María, 40% for Isabella) were expressed via present tense verbs. Still, past tense was the least used means for evaluation. Verbless clauses continued to be the main means used by both girls to express setting.

In sum, during this transition phase children moved from using non-conventional means to report events to producing past tense verbs in most narratives, but without yet consistently sustaining a past perspective for reporting events. The frequency of past tense forms slowly increased during this phase, and the distinction between perfective and imperfective started to surface in just a few uses that denoted either duration or iteration.

Phase 3: explosion of forms

During the last months, these young narrators consistently reported all narrative EVENTS via past tense verbs, with the only exception of narratives anchored in the present tense. Narratives displayed a sustained sequence of past tense verbs, but a few illustrated the still ongoing struggles with the use of past tense/aspect to report evaluation and setting.

These narratives were the longest and most complex performances in the dataset, signaling an advancing ability to sustain a past perspective. EVENTS were consistently reported via past tense, and new perspectives were combined with the perfective option used almost exclusively in previous phases. Indeed, the panorama clearly changed from a monotonous rendition of EVENTS basically dominated by the present perfect for María, and the preterite for Isabella, with occasional uses of the imperfect, to narrations that combined as many as four distinct past tenses. In the narratives of the last three months, the preterite shared the narrative space with the imperfect (and with the present perfect for María), and an imperfect progressive (plus a prospective imperfect only for Isabella) offered yet additional perspectives on the course of past actions. While the anticipated perfective/imperfective distinction from previous months became consolidated, the next aspectual contrast was progressive vs. non-progressive past actions. The following example displays a set of multiple shifts in tense/aspect that mark effective contrasts. Functional tense shifts occurred from past to present tense to distinguish event vs. speech clauses, respectively; and imperfect progressive, perfective and imperfect were used to mark different perspectives on past actions: durative, completed/punctual or iterative contours.Footnote 11

CHI: Y yo estaba, yo estaba,‘And I was, I was

yo estaba jugando (ipfv.prog)I was playing (ipfv.prog)

con mis piezaswith my [puzzle] pieces

y me estaba alacando (ipfv.prog)and [she] was pulling (ipfv.prog) [away]

[:arrancando]esa pieza, iasí, así!that piece from me, [like] this, [like] this!’

MOT: ¿Así te las arrancaba(ipfv)‘[Like] this [she] was pulling (ipfv)

de tu mano? them away from your hand?’

CHI: ¡Sí!‘Yes!’

MOT: ¿Y tú qué hiciste (pfv)?‘And what did you do (pfv)?’

CHI: Yo e poní (pfv-overreg)‘I put (pfv-overreg) it

y Abrí me quitó (pfv) ota vez‘and Abri took (pfv) it away again

y yo dijo (pfv-3rd p.sg):and I said (pfv-3rd p.sg):

“Me das (pres-2nd p.sg.) esa pieza“Give (pres-2nd p.sg.) me that piece please”

por faló [:favor]”

y Abrí me quitaba (ipfv)and Abri was taking (ipfv) [it] away

así[like] this

y no me decía (ipfv) por faló [:favor]!and [she] was not telling (ipfv) me please!’

MOT: ¡No te decía (ipfv) por favor!‘[She] was not telling (ipfv) you please!’

CHI: Yo le decía (ipfv) por faló [:favor]‘I was telling (ipfv) her please

y me quitaba (ipfv)and [she] was taking (ipfv) [it] away

y arranchaba (ipfv)and [was] pulling (ipfv) away

yo le decía (ipfv) por faló [:favor]I was telling (ipfv) her please

y ella me daba (ipfv)and she was giving (ipfv) [it] to me

y me arranchaba (ipfv)and [she] was pulling (ipfv) [it] away from me

y yo le pedía (ipfv) por faló [:favor].and I was asking (ipfv) her (saying) please’

MOT: Mm, ¿y entonces qué‘Mm, and then what did [you]

hicieron (pfv)?do (pfv)?’

CHI: Y Ima [:Irma] e decía (ipfv) a Abrí‘And Ima was telling (ipfv) Abri

que no se debe (pres:aux) arranchar!that [one] should (pres:aux) not pull away.’

MOT: Ah ok.‘Ah OK.’

CHI: ¡Y ella hació (pfv-overreg)‘And she did (pfv-overreg)

ota [:otra] vez!again!

yo le dije (pfv) por faló [:favor].I told (pfv) her please.

Ella me arranchó (pfv).She pulled (pfv) [it] away from me.’

MOT: ¿Y qué pasó (pfv)?‘And what happened (pfv)?

CHI: Y Ima le lijo [:dijo] (pfv):‘And Ima told (pfv) her:

“¡No hagas (neg imp) eso!” (…)“Don't do (neg imp) that!” (…)’

(Isabella, 3 ; 3)

The most significant change in the production of evaluative clauses was a sudden spurt in the use of past tense to express evaluation, with some sessions exhibiting as many as 65% (for María) and 75% (for Isabella) of evaluation clauses with past tense verbs (e.g. y no me decía (ipfv) por faló!). Verbless clauses now constitute the secondary means for expressing evaluation and present tense remains used, although less frequently than in the previous phase. In setting clauses, the use of past tense also increased, although verbless clauses continued to be frequent and for some sessions were still the most prevalent.

Unconventional uses of present tense for evaluation and setting

Towards the end of the year, the children produced a few long and minimally scaffolded narratives. Interestingly, even with the maintenance of past tense being a challenge in such autonomous discourse contexts, past tense was consistently used for EVENT clauses. It was in the context of setting or evaluation, that past tense was not consistently used. The following example displays a fragment of María's retelling of ET, a narrative anchored in the past tense. The complex content combined with the length of the narrative posed a challenging scenario for tense maintenance and María produced some unexplained shifts into present tense in her retelling:

CHI: (…) pues el niño se asustó (pfv).‘(…) well the boy got scared.

Estaba (ipfv) sentado en una silla,[He] was sitting on a chair,

se asustó (pfv) de ET.[he] got scared with ET.’

FAT: ¿Le dio (pfv) susto o no?‘[He] got scared or not?

¡Pobrecito!Poor thing!’

CHI: Y mira, se ponía (ipfv) así‘And see, [he] was [like] this

porque se asusta (pres).because he is scared.’

FAT: ¿Cómo pone (pres) la cara?‘What face does [he] make?’

CHI: La cara así.‘The face [like] this.’

[% makes a scared face][% makes a scared face]

FAT: Hala, ¡qué cara más fea!‘Wow, what an ugly face!’

CHI: Ésa la pone (pres) el niño.‘That [face] makes the boy.’

(María, 2 ; 9)

For EVENTS, the child appropriately used past tense, but when she reported evaluation she sometimes shifted into present tense. Unfortunately, these unconventional instances were not sufficient to warrant an analysis of possible discourse-motivated shifts.

In the context of more autonomous performances, setting and evaluation seem to be more vulnerable components, while EVENTS are consistently reported via past tense. Thus, while unconventional uses of tense were minimal after the first half of these girls' third year, it could be expected that as they move towards more autonomous narrative performances, this advance in autonomy would bring with it the new challenge of tense maintenance, particularly in the expression of setting and evaluation.

Diversity and integration of temporal/aspectual markers

Towards the end of their third year, the frequency and variety of markers for expressing temporality in narratives increased considerably for both girls. Two important developmental advances took place: (1) the emergence of temporal setting providing relevant reference time for narrated events; and (2) the integration of distinct temporal markers within clauses and narratives. Children displayed the ability to integrate as many as three (María) or four (Isabella) types of temporal/aspectual markers within a single narrative. These narratives combine reference time markers, aspectual expressions and temporal adverbs offering explicit and relevant temporal information.

CHI: Cuando, cuando eh era (ipfv) chiquita‘When, when eh [I] was little,

decía (ipfv) “patapatatatata”I used to say “patapatatatata”

y a poco a pocoand by little by little

había aprendido (past.perf) xx.[I] had learned xx.’

[%com: child refers to the fact that when she was little she could not speak well]

MOT: Has aprendido‘[You] have learned

y aprendido cada vez más ¿no gorda? and learned more each time, right?’

CHI: Sí.‘Yes.’

Despés cumpía(ipfv) un año‘After [that] [I] turned one year,

y despés cumpía (ipfv) dos añosand after [I] turned two years,

y despés cumpía (ipfv) tres años. and after [I] turned three years.’

MOT: Exacto‘Exactly.’

(Isabella, 3 ; 1)

CHI: Joseantoniete hoy m'a [:me ha] pegao.‘Joseantoniete today has hit me.

M'a [:me ha] pegao (pres.perf),[He] has hit me,

<cuando estaba>,when [he] was,

cuando estaba (ipfv) su marde [:madre]when his mother was

en el jardín.in the yard.’

MOT: ¿Sí?‘Yes?’

CHI: Sí. ‘Yes.’

MOT: ¿Y qué hacías (ipfv) allí?‘And what were [you] doing there?’

CHI: Pues estaba hablando (ipfv.prog)‘Well, [I] was talking

con Ma. Carmento Ma. Carmen

y su madre,and his mother,

y a Joseantonioand to Joseantonio

y la, y l'a [:le ha] preguntao (pres.perf)and the, and [he] has asked

a su marde [:madre]:his mother:

“Quieres (pres) jugar con la,“Do you want to play ball with the,

conmigo a la pelota mamá?”with me mom?”

Eso ha preguntao (pres.perf).That [he] has asked.’

MOT: Y su mamá ¿qué le ha dicho (pres.perf)?‘And his mother, what did [she] say?’

CHI: No, Joseantonio no.‘No, Joseantonio, no.’

(María, 2 ; 11)

Clearly, not all narratives displayed such skillful integrations. These few examples, however, are illustrations of these children's optimal skills in the expression of temporality via explicit grammatical markers.

CONCLUSIONS

From two to three years of age, children in this study progressed from scattered and inconsistent linguistic means for encoding pastness to mastering a basic linguistic system that included devices to mark location of events (past, present and future), temporal relations (anteriority, simultaneity and posteriority), and aspectual meanings (perfective, imperfective, progressive, iterative). Obviously, by age three, they had only acquired a subset of the forms and functions available in their language and they still had much to learn. However, the basic means already acquired by the end of their third year allowed these children to construct narratives with explicit temporal relations successfully conveyed via linguistic expressions.

DISCUSSION

This analysis illustrates a converging development, with grammar and discourse developing interactively. At the beginning of the year, with still limited grammatical skills, children used not only non-verbal means (e.g. gestures and onomatopoeias), but also reported speech to convey complex narrative content. Children seemed to be searching for forms of expression as the result of their motivation to report what happened. In line with these results, Halliday (Reference Halliday1975) has already documented a child aged 1 ; 6 spontaneously narrating past happenings to an adult using unconventional and rudimentary linguistic forms. Following Bruner's (Reference Bruner1990) argument, this motivation to narrate would push forward grammatical development in that the desire for more accurate reports will lead children to search for more precise grammatical means of expression. In particular, as Nelson (Reference Nelson1996) has proposed, children's drive to sequence events seems to be a core force stimulating co-occurring grammatical and discourse development. Once new grammatical devices are acquired, children's ability to communicate more complex narratives advances as well. In this way, progress continues, and will continue, as the result of a constant synergic development of skills.

Developmental co-occurrences

These data reveal important points of concurrence with Nelson's (Reference Nelson and Nelson1989) analysis of Emily's narratives. First, Nelson's claim that linguistic forms lead to the conceptualization of the distinction of past, present and future time is highly relevant. Initially, children in this study used perfective past inflections only partially to report events, and their uses of past tense were far from systematic. We can speculate that during this initial phase perfective forms have come to the children's attention based on their interactions with adults, but the conceptual distinctions of these forms are still under construction (Nelson, Reference Nelson and Nelson1989; Reference Nelson1996). Once children established the connection between foregrounded EVENTS and perfective past tense, an explosion of temporal skills took place. This initial conceptual/linguistic advance seems to offer a conceptual frame that facilitates the construction of further connections between linguistic forms and their temporal meaning. Now, children start to represent their experientially driven event knowledge – e.g. sequence, duration – with new linguistic devices such as adverbs and connectives. This synchronous development of multiple skills to express temporality indexes an initial basic system of temporality.

Temporal markers and reference time

As in Nelson's descriptions of Emily's narratives, temporal/aspectual markers were produced as early as the first past perfective forms expressing temporal contrasts emerged. However, the frequency and functionality of these markers dramatically changed after the consolidation of past perfective to express EVENTS was achieved. In line with Smith's (Reference Smith1980) original proposal and Weist & Buczowska's (Reference Weist and Buczowska1987) model, these young children were able to refer to a time preceding speech time (ST) via tense inflections. This study suggests that, within the highly complex Spanish verb paradigm, children focus first on mastering a basic form, i.e. perfective, to express past actions in narratives without explicitly marking other temporal relations. During the initial productive yet not systematic use of past tense marking, the only markers used were either empty connectives or aspectual markers. Gradually mere juxtaposition and inconsistent past tense gave way to the systematic expression of past EVENTS via perfective and only then did a substantial increase in temporal markers take place. At this point temporal markers were introduced to make temporal relations explicit and reference time emerged, via temporal adverbs, connectives, full clauses and other expressions. In line with Weist's analysis, reference time emerged only between 2 ; 6 and 2 ; 9, when the explosive synchrony of temporal skills took place. The systematic use of the perfective immediately precedes or coincides with the abrupt increase in temporal markers and the emergence of temporal setting, and therefore suggests a temporal system in which ST (speech time), ET (event time) and RT (reference time) can be all expressed linguistically for the first time. In accordance with Weist's third phase, children in this study referred only to restricted RT, i.e. that which coincides with ET, and were still not able to refer to flexible RT.

Abundant use of past tense verbs

First, the distinct past tense inflections – i.e. present perfect vs. preterite – preferred by each child corresponded to the most frequent forms of the language varieties that surrounded each of them.

Second, children in this study produced a high frequency and considerable diversity of past tense verbs during their third year of life. In contrast, several previous studies of Spanish acquisition have reported minimal variety in past tense forms before age three (González, Reference González1980; Peronard, Reference Peronard1987; Morales, Reference Morales1989; Johnson, Reference Johnson and Pérez Pereira1996). None of these previous studies focused on narrative discourse, therefore the answer to the discrepancies seems to be found in the context of language production. This analysis points towards narrative as a context that promotes a sophisticated use of grammar, specifically of past tense inflections. These findings are indeed consistent with Sebastián & Slobin's (Reference Sebastián, Slobin, Berman and Slobin1994) and Eisenberg's (Reference Eisenberg1985) studies. It is of the utmost importance to describe discourse context in studies of verb use or acquisition. Without this specification, individual differences as well as contradictory results among studies will remain unanswered. In particular, future comparative analyses of narrative vs. non-narrative discourse are crucial to fully understand how different discourse contexts interact with specific lexico-grammatical skills in the expression of temporality.

Additionally, despite the early contrastive use of perfective tense reported for María by Fernández (Reference Fernández and López Ornat1994), it was only at the age of 2 ; 6 that María started to use the past tense consistently to report narrative events. Thus, in line with Shirai & Miyata's (Reference Shirai and Miyata2006) distinction between the use of contrastive past tense and the use of deictic past, the first contrastive uses of past tense for this girl seem to signal only the beginning of a gradual learning process. In fact, the abundant production of past tense inflections reported in this study is not at odds with a view of a piecemeal acquisition (see Gathercole et al., Reference Gathercole, Sebastián and Soto1999).

This study underlines the importance of narrative co-construction in development; and it foregrounds the need to study grammatical and discourse progress in an integrative manner, so that children's progress can be fully understood. While the current results are revealing of interconnected phenomena in the development of past reference, they are also limited to only this corner of temporality, without analyzing present, future or conditional reference. Only further research with larger samples could confirm the developmental co-occurrences reported here. These findings offer an initial but incomplete account of how temporality develops in Spanish and invite further explorations of the full temporal system.

APPENDIX: Narrative components: coding manual (adapted from Hemphill, Uccelli, Winner, Chang & Bellinger, Reference Hemphill, Uccelli, Winner, Chang and Bellinger2002)

Children's narrative utterances were broken down into clauses. A clause is defined as ‘a unit that contains a unified predicate, … [i.e.] a predicate that expresses a single situation (activity, event, state). Predicates include finite and nonfinite verbs, as well as predicate adjectives’ (Berman & Slobin, Reference Berman and Slobin1994: 660). Each narrative clause should be coded using only one narrative structure coding (%nas).

Narrative structure (%nas)

- $SETT

Setting. Clauses that provide descriptive information about the spatio-temporal context of the events, the characters and any additional background information that provides the context of the narrated events. Clauses that refer to temporal setting were identified:

- :TEM

Temporal setting. Clauses that offer a temporal framework either for the entire narrative or for a specific fragment of it, e.g. Era verano ‘It was summer time’; Eran las 5:30 de la tarde ‘It was five thirty in the evening’; Cuando tenía tres años ‘When I was three’.

- $EVNT

Events. Clauses that report actions will be coded as events. Events constitute the backbone of the narrative as they are the components which advance the narrative plot.

- :NV

Non-verbal. This code is added when the event is reported non-verbally, via gestures or enactment. Events should be coded as NV when they are conveyed via non-verbal means exclusively.

- :ONO

Onomatopoeic. This code is added when the event is reported via onomatopoeic sounds without being reported verbally. If the onomatopoeic forms refer to an event which is conveyed verbally conveyed, then the onomatopoeia should be coded as $EVAL.

- $EVAL

Evaluation. Clauses that provide affective or evaluative commentary on the events will be coded as evaluation. These clauses included onomatopoeic forms, intensifiers, adjectives, internal states and causality.

- $OPE

Narrative opening, e.g. Había una vez, Once upon a time; Te acuerdas cuando …, Remember when …

- $CLOS

Narrative closing. Clauses that contain explicit expressions of termination, e.g. y colorín colorado este cuento se ha acabado, The end.

- $NNAR

Non-narrative talk. Clauses that are not part of the narrative. ‘Yes’ and ‘no’ answers to adult's questions, attention getters, child's questions and off-topic clauses irrelevant to the narrative.

- $UNC

Unclassifiable.

ADDITIONAL CODES FOR REPETITION