Introduction

Sex work is widespread in India, and occurs on a much larger scale than in many other countries (NACO, 2006). It has been estimated that India has more than a million female sex workers (FSWs) (NIMS & NACO, 2006), which is about 1% of the adult women in India (Dandona et al., Reference Dandona, Dandona, Kumar, Gutierrez, McPherson, Samuels and Bertozzi2006). In southern India, the presence of large number of FSWs, combined with high HIV prevalence among them, has given rise to a myriad of interventions with various strategies (Blanchard et al., Reference Blanchard, O'Neil, Ramesh, Bhattacharjee, Orchard and Moses2005). These strategies include individual/cognitive interventions through peer outreach and education and the use of structural/environmental interventions (Jana & Singh, Reference Jana and Singh1995; Ngugi et al., Reference Ngugi, Wilson, Sebstad, Plummer and Moses1996; Parker et al., Reference Parker, Easton and Klein2000; Kerrigan et al., Reference Kerrigan, Ellen, Moreno, Rosario, Katz, Celentano and Sweat2003; Jana et al., Reference Jana, Basu, Rotheram-Borus and Newman2004; Blankenship et al., Reference Blankenship, West, Kershaw and Biradavolu2008; Reza-Paul et al., Reference Reza-Paul, Beattie, Syed, Venukumar, Venugopal and Fathima2008). Despite these interventions, recent evidence suggests high rates of HIV among sub-groups of FSWs such as illiterates, widows, divorcees and mobile FSWs (Brahme et al., Reference Brahme, Mehta, Sahay, Joglekar, Ghate and Joshi2006; Ramesh et al., Reference Ramesh, Moses, Washington, Isac, Mohapatra and Mahagaonkar2008).

Cross-nationally, research demonstrates that women enter sex work for various reasons: lack of economic development in rural areas (Wawer et al., Reference Wawer, Podhisita, Kanungsukkasem, Pramualratana and McNamara1996), economic necessities within the household and ‘survival sex’ (Whelehan, Reference Whelehan2001; Rao et al., Reference Rao, Gupta, Lokshin and Jana2003; Bucardo et al., Reference Bucardo, Semple, Fraga-Vallejo, Davila and Patterson2004; Hong & Li, Reference Hong and Li2008) and coercion or deception, which forces them into sex work against their will (Basu et al., Reference Basu, Jana, Rotheram-Borus, Swendeman, Lee, Newman and Weiss2004; Busza, Reference Busza2004; Silverman et al., Reference Silverman, Decker, Gupta, Maheshwari, Patel and Raj2006). A few Indian studies have analysed the reasons for entry into sex work and identified male dominance, trafficking, destitution of women (Blanchard et al., Reference Blanchard, O'Neil, Ramesh, Bhattacharjee, Orchard and Moses2005; Dandona et al., Reference Dandona, Dandona, Kumar, Gutierrez, McPherson, Samuels and Bertozzi2006; NACO, 2006) and industrialization (UNESCO, 2002; Blanchard et al., Reference Blanchard, O'Neil, Ramesh, Bhattacharjee, Orchard and Moses2005) as the major reasons. Increasing evidence around profiles of the FSWs suggests that a majority of them are illiterate, or belong to lower caste groups, or face poor economic conditions back at home (Chattopadhyay et al., Reference Chattopadhyay, Bandyopadhyay and Duttagupta1994; Salunke et al., Reference Salunke, Shaukat, Hira and Jagtap1998; Chattopadhyay & McKaig, Reference Chattopadhyay and McKaig2004; Dandona et al., Reference Dandona, Dandona, Kumar, Gutierrez, McPherson, Samuels and Bertozzi2006; Ramesh et al., Reference Ramesh, Moses, Washington, Isac, Mohapatra and Mahagaonkar2008; Reza-Paul et al., Reference Reza-Paul, Beattie, Syed, Venukumar, Venugopal and Fathima2008) indicating that women from poor socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to be in sex work. While these studies have provided valuable information on little known areas of sex work, the extent to which their findings can be extrapolated to inform programme design is limited because they are based on either small sample sizes or did not explore the major reasons for entry into sex work. More importantly, these studies have not examined the relationship between motivations for entry into the sex work and condom use behaviour.

One important question that has frequently dominated the discourse on FSWs in India, and continues to remain relevant to both anti-trafficking and HIV prevention programmes, relates to the reason(s) that determine a woman's/girl's entry into sex work: are the women trafficked into sex work or do they join sex work by their own choice? Further, are those women who join sex work due to compelling conditions or force more likely to have higher HIV risk behaviours than others? With answers to these research questions, this study advances knowledge on reasons for entry into sex work and its associated factors, and examines its linkages with condom use behaviours.

Methods

The study is based on data from a cross-sectional behavioural survey conducted between September 2007 and July 2008 in 22 districts with at least 2000 reported FSWs from four high HIV prevalence states of southern (Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu) and western (Maharashtra) India. The districts were identified using unpublished mapping and enumeration data of FSWs collected independently by the State AIDS Control Society and Avahan (India AIDS Initiative of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation). The sample size for a district was determined by using an estimated proportion of 30% inconsistent condom use, an assumed difference of 3% increase in the proportion with every unit increase in degree of mobility, a confidence level of 95% and power of 80%.

A uniform sampling design was used for each district to select FSWs for screening; however, the districts varied significantly in terms of the number of FSWs and locations in which they practise sex work. The district-level descriptions helped to identify small and large FSW sites (hotspots), which included brothel areas and soliciting places such as roads, highways, bus stands, railway stations and market areas. These lists of hotspots were used to prepare a list of PSUs (primary sampling units). Primary sampling units were formed by combining small hotspots or by segmenting large hotspots such that each PSU has approximately 500 FSWs. Three PSUs were selected randomly in each district. The sample size for each PSU was fixed at about 20% of FSWs. The number of FSWs to be interviewed was allocated to brothel-based and non-brothel-based in proportion to their estimated size. Two types of sampling procedures were adopted for selecting brothel-based and non-brothel-based FSWs because of the difference in how sex work is practised in India.

For selection of FSWs in brothel-based areas, a two-stage systematic sampling procedure was used. First, a list of lanes/small pockets/areas within a brothel site in a PSU was prepared. About 20% of the lanes or small areas were selected systematically at the first-stage sampling. In the second-stage sampling, brothel houses were systematically selected from selected lanes, with the first house selected randomly and subsequent houses selected based on a calculated interval.

For selection of sex workers in non-brothel-based areas, a time location sampling procedure was used. Using the lists of hotspots, the key informants and NGO staff were contacted to determine the peak days and times for the sex workers' visit to the sites. Thus, for each area, time slots were fixed for the interviewers to visit the site. Interviewers visited each of those sites as per the allotted time slot and waited for sex workers. Female sex workers who came to the site at the defined times were selected for interview using a screening tool.

A total of 10,075 FSWs were contacted through sampling; 94% (n=9475) agreed to be interviewed using a screening questionnaire, and 5611 of them were found to be eligible for detailed interview according to the study definition of mobile FSWs. (Mobility is defined as those who moved to two or more places for the purpose of sex work in the past two years, and one of those moves/visits was made across districts.) Of these 5611 eligible FSWs, 113 were excluded from the analysis: fifteen were not interviewed because they were below the age of 18 years, 21 refused to participate due to lack of time, 51 withdrew from the interview in the middle, and for 26 individuals data were missing on socioeconomic variables.

The data were obtained via face-to-face interviews conducted in private or public locations according to the choice of the respondents. Interviews were conducted by multi-lingual research investigators with a graduate degree. Verbal consent was obtained from all respondents prior to their participation by the interviewers.

Survey data were collected in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu using hand-held PDAs (palmtop digital accessories); in Karnataka, data were collected using printed questionnaire forms. The quality assurance of data collection involved immediate review by field staff after interviews to ensure accuracy and completion. This was followed by same-day review by the field supervisor, and weekly transport of data to the data management team in Karnataka where data were entered and processed monthly to verify accuracy in data entry. The quality assurance for PDAs involved customized data collection screen, and review of the data for accuracy on a daily basis soon after downloading data to the mainframe computer. Data collected from printed questionnaires and PDAs did not show any differences in data collection/recording/quality, except that more time has gone into entry of Karnataka survey data.

Measures

Women in the survey were presented with a list of five reasons for entering sex work, drawn primarily from qualitative research conducted prior to the survey in the same selected sites. Each woman in the survey was asked to mention the primary reason for her entry into sex work. The responses were collected under five broad categories that included: force (defined as exploitation, deception by known people, deception by unknown people, false marriages, and being sold to brothels); negative social circumstances in life (lack of basic education, early marriage, restricted control over major decisions in life, worry over caring for children, domestic violence, husbands' alcoholism and/or extramarital behaviours); economic conditions (wanting more money, debt, paying-off loans borne by husband or parents, inadequate income in the household, requirement of money to take care of husband or parents who have chronic illnesses, money for children and children's education, and lack of employment, need for an adequate dowry for the marriage of their daughters); traditional family activity (belonging to particular caste groups where sex work is an accepted norm, i.e. Devdasi in Karnataka, Lambani in Andhra Pradesh, Bedia in Madhya Pradesh, Kanjar in Gujarat, Kolathi in Maharashtra, Dewar in Chhattisgarh) and own choice (willingly engaging in sex work and not reporting any of the above). Traditional sex workers from Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and Chhattisgarh were identified in the sample from Maharashtra state.

Data were collected from individual FSWs on their demographic characteristics (age, marital status, age at entry into sex work, age at first sex, age at marriage for currently married respondents), socioeconomic characteristics (education, income and presence of debt at the time of entry into sex work as well as at the time of the survey, value of debt at the time of survey), sex-work-related characteristics (places of solicitation, places of sex and occupations engaged in addition to sex work). For the purposes of examining the relationship between reasons for entry into sex work and condom use behaviour, information on controls such as the duration of sex work and exposure to intervention programmes was also collected. Exposure to programmes was measured from questions on their access to either free or subsidized condoms or their ability to purchase condoms (coded as 1 for ‘yes') and if neither accessed free or subsidized condoms nor purchased condoms (coded as 0 for ‘no’).

The survey also collected information on condom use behaviours with occasional, regular and non-paying clients in the current place (condom use in the past week prior to survey), previous place of work (visit in the past 2 years) and during their visit to jatra places (places where religious festivals celebrated in a group) in the past 12 months. These data were used to create variables such as inconsistent condom use in the current place (with occasional, regular clients and non-paying partners), inconsistent condom use in the previous place of work (with occasional, regular clients and non-paying partners), inconsistent condom use in visit to jatra places and overall inconsistent condom use in the past 2 years. Inconsistent condom use is defined as the non-use of a condom even a single time that the respondent had sex with clients and/or non-paying partners.

Analyses

Univariate statistics were used to analyse the reasons for entry into sex work. Chi-squared analyses were used to identify differences in reasons for entry into sex work by socio-demographics among women engaged in sex work. A logistic regression model was developed to investigate the relationship between reasons for entry into sex work and different indicators of inconsistent condom use. Variables that had a p-value less than 0.10 in the univariate analysis were considered in the logistic regression model. The importance of these factors in the logistic model was determined by their significance on a likelihood ratio test. The relationships between reasons for entry into sex work and inconsistent condom use were adjusted for socio-demographic characteristics, duration of involvement in sex work and exposure to programme interventions. Crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR) were used to interpret the relationship of inconsistent condom use among FSWs to the risk factors. Confidence intervals (CI) are reported at 95%. The effect of small size in a category is reflected by large CIs. Only statistically significant adjusted ORs were used while discussing the relationships. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS v16.0.

Results

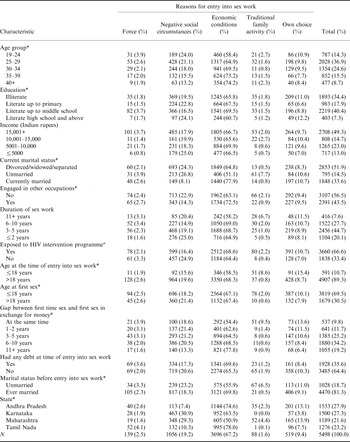

Of the 5498 respondents with complete information, 51% were below the age of 30 (range 18–62 years; SD 6.9 years). One-third (1893/5498) were illiterate and 7% (403/5498) had more than 8 years of education (Table 1). One-third (1848/5498) of the respondents were currently married; 52% (2853/5498) had been previously married and the remaining 15% (795/5498) were single. A little more than two-fifths (2391/5498) of the respondents were also engaged in other occupations such as agriculture work, construction work, fruit/vegetable selling, daily wage work, domestic work, petty business, bar work, and shop attendants in bus/railway stations. Overall, the mean age at entry into sex work was 24.1 years (range 9–41 years; SD 5.09 years) and age at first sex was 17.5 years (range 9–38 years; SD 3.09 years). Of the total sample, four-fifths (4470/5498) were married before their entry into sex work and three-quarters were currently either divorced, widowed or separated.

Table 1. Distribution of socio-demographic characteristics and reasons for entry into sex work by state

About two-thirds of the respondents (3696/5498; 67.2%) reported economic reasons (with or without an outstanding debt at the time of entry) for entering into sex work; 19.2% reported negative social circumstances in life (1056/5498); and 9.4% (519/5498) reported that they entered into sex work on their own choice. A relatively small number reported force (2.5%, 139/5498) or that sex work was a traditional family activity (1.6%, 88/5498). Reasons for entry into sex work as well as other characteristics varied significantly among states. For example, the major reason given by FSWs from Andhra Pradesh to enter into sex work was economic conditions, while a considerable proportion of women in Karnataka (31%; 463/1500) and Maharashtra (29%; 348/1189) states reported that they entered into sex work due to negative social circumstances in life (Table 1).

About one-fifth of the respondents reported negative circumstances in life as a reason for entry into sex work. This proportion is higher among respondents who are in the age group of 25–29 years, with less education, earning less than 5000 rupees a month currently, those divorced/widowed/separated, not engaged in other occupations, unmarried before entry into sex work and those from the states of Karnataka and Maharashtra when compared with their respective counterparts (p<0.001) (Table 2). Similarly, two-thirds of the respondents reported economic conditions as reasons for entry into sex work; these percentages are relatively higher among those respondents with less than primary education, those ever married at the entry of sex work, those engaged in other occupations, those in debt at the time of entry into sex work and those from the states of Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh when compared with their respective counterparts (p<0.001).

Table 2. Distribution of characteristics on the reasons for entry into sex work

* p<0.001, Pearson's χ2 test p-values.

a Exposure to programmes was measured from questions on FSWs' access to either free or subsidized condoms or their ability to purchase condoms (coded as 1, ‘yes') and if neither accessed free or subsidized condoms nor purchased condoms (coded as 0, ‘no’).

In logistic regression models, both crude and models adjusted for socio-demographic characteristics, and intervention-related variables, women who joined sex work for economic reasons and negative social circumstances in life were found to be significantly associated with increased inconsistent condom use in the current place as well as in the places where she practised sex work over the past 2 years as compared with those women who entered sex work willingly because of family tradition or their own choice (Table 3). For instance, inconsistent condom use in the last week is greater among women who entered sex work for economic reasons (44.1% vs 33.3%; adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.12–1.69) or among those who entered sex work due to negative social circumstances in life (53.9% vs 33.3%; AOR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.23–1.99) than those women who entered sex work willingly, even after controlling for their duration of sex work, income, exposure to an intervention programme and other socio-demographic characteristics.

Table 3. Odds ratios (and 95% confidence intervals) from logistic regression models on inconsistent condom use in the past two years by type of clients after controlling for background characteristics

a Weighted average computed from the values on inconsistent condom use in sex with occasional, regular and non-paying partners.

b Adjusted odds ratios: odds ratios are adjusted for the following variables in the multivariate analysis: age group, education, marital status, involvement in occupations other than sex work, age at entry into sex work, age at first sex, state.

c Exposure to programmes was measured from questions on their access to either free or subsidized condoms or their ability to purchase condoms (coded as 1, ‘yes') and if neither accessed free or subsidized condoms nor purchased condoms (coded as 0, ‘no’).

Wald χ2p-values:

*** p<0.001;

** p<0.01.

Discussion

Motivations for women's entry into sex work could be many. This study found that two-thirds of the mobile FSWs in four states of India entered into sex work mainly due to economic conditions, while one-fifth entered due to negative social circumstances in life and one-tenth entered on their own choice. Further, this study found a significant association between reasons for entry into sex work and consistent condom use, indicating that sex workers' practise of consistent condom use to some extent depends on their primary motivation for entry into sex work. For example, sex workers who mentioned negative circumstances in life (viz., husband or other family members with a chronic disease) may remain more vulnerable over time because of continuing negative situations. However, this may not be true for those who entered due to ‘force’. Such sex workers may be most vulnerable at the time of entry but they adapt to the new work environment. These results suggest that intervention programmes should consider working with FSWs with negative life situations to find a solution to removing its effects; for example, by providing health insurance to take care of family members with chronic disease.

More importantly, only 3% of mobile FSWs reported ‘force’ as the main reason for their entry into sex work. Though many Indian studies have shown that the majority of the women are lured or forced into sex work (Chattopadhyay & McKaig, Reference Chattopadhyay and McKaig2004; Dandona et al., Reference Dandona, Dandona, Kumar, Gutierrez, McPherson, Samuels and Bertozzi2006; Silverman et al., Reference Silverman, Decker, Gupta, Maheshwari, Patel and Raj2006), this does not hold true for mobile sex workers. This contradicting result in the Indian context requires further research as to whether women who face negative life situations are vulnerable to options for work offered by facilitators such as agents or whether women voluntarily choose sex work and rationalize their choice post-entry by indicating their negative life circumstances. The results show that most FSWs who join as widowed/separated/divorced enter willingly, by choice, as they relate to either economic conditions or negative social circumstances in life and they are perhaps facilitated to join. The findings of the current study that most women join sex work primarily for economic reasons and due to negative circumstances in life are consistent with many studies in India (Rao et al., Reference Rao, Gupta, Lokshin and Jana2003; Basu et al., Reference Basu, Jana, Rotheram-Borus, Swendeman, Lee, Newman and Weiss2004).

Further, findings from this study reveal that the great majority of FSWs who entered due to economic reasons or negative social circumstances in life are currently in the age group of 25–34 years, previously married and were not engaged in any other occupations. These study findings are consistent with other Indian studies that suggest that lower status in society and fewer economic opportunities for women (Somaiya et al., Reference Somaiya, Awate and Bhore1990; Chattopadhyay et al., Reference Chattopadhyay, Bandyopadhyay and Duttagupta1994) and marital break-up (NACO, 2006) are push factors for entry into sex work and HIV vulnerability (Dandona et al., Reference Dandona, Dandona, Kumar, Gutierrez, McPherson, Samuels and Bertozzi2006).

These findings reinforce the idea that entry into sex work is tied in with the larger issue of the status of women and their lack of economic independence in India. Approximately two-thirds of the study population was married before the legal age of 18, which is relatively higher than the 45% of young adult women in the general population married before age 18 years according to the Indian National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3) (IIPS & Macro International, 2007). The NFHS-3 data document that 56% of adult women in the state of Andhra Pradesh were married before the legal age of 18 years. The corresponding percentages of women married before age 18 years for the states of Karnataka, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu are 41%, 40% and 25%, respectively (IIPS & Macro International, 2007). In the study population, more than four-fifths of FSWs married before the age of 18 years in the states of Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra. Other studies from India suggest that the proportion of women getting married below the age of 18 years is higher among rural, poor and less educated individuals (Audinarayan, Reference Audinarayan1993; Sivaram et al., Reference Sivaram, Richard and Rao1995; Richard & Sunder Rao, Reference Richard and Rao1997; Rama Rao & Sureender, Reference Rama Rao and Sureender1998; Bhagat, Reference Bhagat2002; Raj et al., Reference Raj, Saggurti, Balaiah and Silverman2009). These data suggest that early age at marriage, marital break-up and/or lack of education are some factors for their negative life situations or economic difficulties. Data from the current study also show that more women with marital break-up and lack of education quoted negative circumstances or economic conditions as reasons for entry into sex work.

Research from other countries on reasons for entry into sex work ranges from description of broad contextual factors such as push factors from places of origin in Thailand (Wawer et al., Reference Wawer, Podhisita, Kanungsukkasem, Pramualratana and McNamara1996) or migration from less developed areas to cities (Day, Reference Day1988; Zalduondo, Reference Zalduondo1991), lack of employment opportunities in specific areas of Russia (Aral et al., Reference Aral, St Lawrence, Tikhonova, Safarova, Parker, Shakarishvili and Ryan2003) to more specific individual factors such as money and ‘survival sex’ in China (Hong & Li, Reference Hong and Li2008), economic necessity in Mexico and the US (Bucardo et al., Reference Bucardo, Semple, Fraga-Vallejo, Davila and Patterson2004), quick and short-term income source (Whelehan, Reference Whelehan2001), domestic violence in the US (Sharpe, Reference Sharpe1998; Dalla, Reference Dalla2001) and trafficking in Asia (UNDP, 2007). The current study documents the evidence that reasons for entry – if they are economic in nature or represent negative life circumstances – are associated with early age at first sex, early marriage and lack of education. On the other hand, growing rural poverty, which is driving young women from their villages into unskilled labour in urban areas, is one of the national and regional contextual determinants of the sex work system in India (Rozario, Reference Rozario1988). Some of these individual and contextual factors could be addressed through expansion of social development programmes or through provision of education and employment opportunities for young women and strengthening family and community structures to create a strong culture of protecting young women from sexual exploitation (UNAIDS, 2002).

In addition to documenting the reasons for entry into sex work in India, findings from this study also demonstrate that those women who entered for economic reasons or due to negative social circumstances in life seem to have linkages with their continued inconsistent condom use behaviour in different places where they practise sex work. The linkage between reasons for entry into sex work and inconsistent condom use is significant, even after controlling for duration of involvement in sex work and exposure to programme intervention. These findings suggest a need for heterogeneity in strategies for improving condom use and reducing HIV infection for different sub-groups of FSWs. For example, strategies of communication in programmes could be tailored according to the reasons through which women entered into sex work. The view that those women who engage in sex work by force are more vulnerable to HIV risk (UNDP, 2007) is supported by the current study, as inconsistent condom use is 2.5 times more likely for those women who entered by ‘force’ than those who entered by ‘own choice’.

While the current study provides important insights into reasons for entry into sex work and its association with condom use behaviours, the findings must be interpreted with consideration of several notable limitations. Firstly, the findings cannot be generalized for the entire female sex worker population in India as the sample included only mobile FSWs from four high HIV prevalence states. Secondly, it is possible that women's reports on their entry are socially desirable responses or have been modified over time because of social stigma attached to sex work in India. The third potential limitation of the study is that entry into sex work could include multiple reasons but the survey only asked the respondents to mention a primary reason, which may affect the classification of FSWs and interpretation of the results. For example, economic hardship may be the overriding reason for all FSWs, but some of them decided to report ‘own choice’ as the primary reason for entry into sex work. Future work should consider inclusion of two questions on primary and secondary reasons for entry into sex work. Finally, the data used in the study are retrospective in nature and therefore subject to recall errors and rationalization of past behaviours. For example, inconsistent condom use among those who entered into sex work for economic reasons might also be determined through a woman's own negotiating power and the autonomy within the place where she has sex with her clients. Further, it is likely that women who enter into sex work for one reason (say force) may over the years find other justifications to continue to engage in sex work. On the other hand a woman may enter into sex work reportedly by choice and may subsequently find herself trapped in a situation from which she is unable to get out.

Nevertheless, these findings emphasize the need to consider women's pre-entry conditions in HIV prevention programmes. Failing this, certain mechanisms through which women entered into sex work could lead to serious public health implications, including poor sexual and reproductive health and high levels of violence. For example, sex workers who entered due to negative circumstances in life may be exploited and are subjected to HIV risk through sexual relationships outside of sex work. Sex workers influenced by economic conditions may continue to have inconsistent condom use, if their counselling does not include the pre-entry sex work and current conditions. More importantly, current outreach, education and counselling programmes targeted at individuals among mobile FSWs who entered due to negative circumstances in life or economic conditions or force may prove ineffective in the long run due to the nature of their mobility. These findings and suggestions are in line with the recommendations made by Jana and colleagues (Jana et al., Reference Jana, Bandyopadhyay, Saha and Dutta1999) from the Sonagachi project. The key ingredient of the project's success is not the implementation of a specific set of activities per se, but the fact that the project focused on responding to the targeted community's needs (Jana et al., Reference Jana, Bandyopadhyay, Saha and Dutta1999; Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Parkhurst, Ogden, Aggleton and Mahal2008). Current HIV prevention programmes with FSWs addressing structural barriers (Jana et al., Reference Jana, Bandyopadhyay, Mukherjee, Dutta, Basu and Saha1998; Steen et al., Reference Steen, Mogasale, Wi, Singh, Das and Daly2006; Moses et al., Reference Moses, Ramesh, Nagelkerke, Khera, Isac, Bhattacharjee and Gurnani2008) need to consider individual mobile sex worker's pre-entry context, as this will have important implications for their current work behaviour, including consistent condom use. Addressing the needs of sex workers' pre-entry contexts would be more helpful if this was initiated at their early stages of entry into sex work. In conclusion, increased efforts are urgently needed to expand HIV prevention programmes to reach women in the early years of their entry into sex work as some of their pre-entry contexts might continue to influence their risk for HIV.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation through Avahan, its India AIDS Initiative. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Avahan. The authors thank Gina Dallabetta, Padma Chandrasekaran and Tisha Wheeler for their valuable comments on an earlier version of the paper.