Introduction

Violence against women (VAW) is a widespread problem in every society regardless of class, gender, race, religion, nationality and educational background (Cobia et al., Reference Cobia, Robinson and Edwards2008). Intimate partner sexual violence (IPSV) is the most common form of VAW committed by husbands, boyfriends, dating partners or someone close to a victim. Regarded as a concern in developing countries, IPSV has adverse physical and psychological consequences for women’s health (Heise, Reference Heise1994). It takes place within an intimate relationship, and includes not only marital rape but also all types of sexual assault.

It is estimated that the global prevalence of coerced or forced first-time sex among younger women aged 15 years or less ranges from 11% to 45% (Garcia-Moreno et al., Reference Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise and Watts2006). Worldwide, approximately 30% of women aged 15 or over have experienced physical and/or sexual violence at some time in their lives (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Ferguson, Shrestha, Shrestha, Oakes and Gupta2018). Moreover, 10–50% of women have experienced sexual violence (WHO, 2005). In most cases, sexual violence is perpetrated by a person known to the victim, with sexual IPV having a higher prevalence than non-sexual IPV (Dartnall & Jewkes, Reference Dartnall and Jewkes2013). In addition, younger women are more likely to experience force during their first experience of sexual intercourse (Garcia-Moreno et al., Reference Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise and Watts2006). Although IPSV is a severe problem worldwide, it is a little studied issue in many societies (Heise, Reference Heise1994), including Bangladesh, even though this country has been ranked second by the World Bank among countries impacted by IPV (Solotaroff & Pande, Reference Solotaroff and Pande2014).

Sexual violence is rooted in gender inequality, discrimination and the unequal power balance between men and women (Dartnall & Jewkes, Reference Dartnall and Jewkes2013). No single theoretical framework is available that can explain all factors related to violence against women (Nieder et al., Reference Nieder, Muck and Kärtner2019). However, patriarchy and rigid gender roles have been reported to be instrumental in sexual violence in Bangladesh (Naved, Reference Naved2013). Structurally, a patriarchal society is a male-dominated society in which men enjoy a higher position in terms of power and authority than women. This patriarchal notion not only creates men’s ownership over women’s bodies, sexuality, mobility and autonomy but also grants men the right to control women’s behaviours (Heise, Reference Heise1994; Sharma, Reference Sharma2005). These norms legitimize the male perpetration of ownership, with women tending to accept it as part of their fate and relationship. Patriarchal norms create gender inequality at the societal level, constructing power hierarchies in which women are placed in a subjugated position compared with their male counterparts (Sharma, Reference Sharma2005). This powerlessness creates an inability to resist the male perpetration of these norms against women (Visaria, Reference Visaria1999).

Socio-cultural factors are associated with perceived gender roles in Bangladesh. Gender-role socialization means learning the social expectations and attitudes related to one’s gender (Nieder et al., Reference Nieder, Muck and Kärtner2019). In a patriarchal society, women are expected to be kind and sympathetic, while men are expected to be independent, powerful and aggressive (Heilman, Reference Heilman2001). Likewise, women are expected to do the housework, child rearing, food preparation and cooking, while men are expected to work outside the house and be the income earner. Women are expected to be passive and men the decision-makers; therefore, men are perceived as superior to women. In this type of society, men inflicting violence at the household level is socially accepted, contrary to the situation for women where it is not accepted. This acceptance of paradoxical gender roles is a significant risk factor for the prevalence of sexual violence in Bangladesh. Through this process, women become more subdued; therefore, men take the opportunity to be more dominant and to exercise more control over women. These gender roles transmit from generation to generation, creating hierarchical constructions of masculinity and femininity that essentially contribute to sexual violence at the household level (Saravanan, Reference Saravanan2000).

Patriarchy or male dominance in a society is considered the most common factor associated with sexual violence (Kalra & Bhugra, Reference Kalra and Bhugra2013). In contrast, protective factors, especially a higher level of education and a higher income, reduce the likelihood of being a victim of violence. Education and income increase women’s empowerment, thus reducing their risk of gender-induced violence. However, women’s empowerment may have adverse effects: when women become empowered they have a more significant role in society, challenging the traditional gender roles. This increases social tension which, in turn, may cause sexual violence (Lodhia, Reference Lodhia2014). This phenomenon is a form of patriarchal backlash, whereby violence against women increases as men want to adhere to traditional gender roles and regain control over women (Lodhia, Reference Lodhia2014). If women challenge traditional gender roles, men feel deprived of socially sanctioned privileges and fear the loss of control over women. If women gain more liberty, they may face more violence (Simister & Mehta, Reference Simister and Mehta2010) as a result of the power conflict. Patriarchal ideology reinforces the traditional gender roles that justify the power of men over women.

In marital relationships in Bangladesh, men have been observed to exercise more power than women and to be more violent. Women are abused due to power asymmetry (Gerber, Reference Gerber1991). At times, a husband perpetrates violence against his wife to establish and exercise his power over her (Dobash & Dobash, Reference Dobash and Dobash1979). When a girl enters a new family as a wife, she acquires the lowest position in the family’s power hierarchy. Moreover, socially and financially, she is dependent on her husband as she does not have immediate access to paid work. Newly married young women do not discuss incidents of sexual violence with others as these issues they consider to be exclusively private. They also refrain from seeking support from legal aid organizations for fear of repeated victimization, disgrace or the risk of getting divorced.

Various factors are associated with sexual violence in Bangladesh. Ahmed (Reference Ahmed2005) revealed that age, schooling, household head’s education level, poverty and development programme membership were predictors of IPV against women in a rural area of Bangladesh. Johnson and Das (Reference Johnson and Das2009) found that a husband’s drug abuse, polygamy, unfaithfulness to his wife and attitude towards wife-beating (wife-beating norms) increased the risk of spousal violence in Bangladesh. Naved (Reference Naved2013) revealed different associated factors, which included a patriarchal mindset in the family’s history, age of the woman, dowry demands and income quartiles. Sambisa et al. (Reference Sambisa, Angeles, Lance, Naved and Curtis2010) found that factors provoking sexual violence included: residence in a district municipality, younger age, less education, lower-class family, husband’s alcohol addiction, sexually transmitted disease (STD), poor mental health and wife-beating norms. Naved and Persson (Reference Naved and Persson2005) found that dowry demands, history of abuse of the husband’s mother by his father and wife’s credit group membership increased the likelihood of a wife’s physical abuse by her husband.

Islam et al. (Reference Islam, Tareque, Sugawa and Kawahara2015) found that the likelihood of IPV was increased among husbands who had witnessed their mother being beaten by their father. Abramsky et al. (Reference Abramsky, Watts, Garcia-Moreno, Devries, Kiss, Ellsberg and Heise2011) showed that a woman’s risk of IPV was reduced by higher education, higher socioeconomic status and having an arranged (formal) marriage. Das et al. (Reference Das, Bhattacharyya, Alam and Pervin2016) reported that dowry demands, poverty, the wife’s financial and emotional dependency, husband’s extramarital affairs and his desire for male children were the main reasons for violence against women. The Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) (BBS & SID, 2016) reported that 27.3% of married women had experienced more than one sexual violence incident perpetrated by their husbands during their lifetime. Just under a quarter (22.1%) of married women had experienced forced sex; followed by being compelled to have sexual intercourse against their will (18.7%) or being forced to do something sexual that they found humiliating or degrading (5.8%).

South Asia has been considered one of the worst places for women experiencing violence of different types during their lifetime (Khurram & Hyder, Reference Khurram and Hyder2003). Puri et al. (Reference Puri, Shah and Tamang2010) showed that gender norms, wife’s financial dependency, poverty, husband’s drug addiction, social stigma and wife’s poor familial and social environments were the main factors for sexual violence against married women in Nepal. Similarly, Oshiro et al. (Reference Oshiro, Poudyal, Poudel, Jimba and Hokama2011) found that IPV in Nepal was associated with husbands drinking alcohol, polygamy and lower household economic status. Jayasuriya et al. (Reference Jayasuriya, Wijewardena and Axemo2011) found that those at greatest risk of IPV in Sri Lanka were young women, wives of husbands addicted to drugs and wives with husbands having extramarital affairs. Likewise, Kimuna et al. (Reference Kimuna, Djamba, Ciciurkaite and Cherukuri2013), in their study in India, showed that place of residence, religion, marriage duration and women’s level of education were significantly associated with sexual violence against married women in the household. A recent study revealed that area of residence, religion, respondent’s education, wealth index, partner’s occupation and respondent’s occupation were IPSV predictors in Bangladesh (Sanawar et al., Reference Sanawar, Islam, Majumder and Misu2019).

In contrast, it is very difficult to identify the determinants of IPSV in Bangladesh due to the country’s cultural setting (Sanawar et al., Reference Sanawar, Islam, Majumder and Misu2019). Moreover, it is hard to make a comparison with results from prior studies due to differences in the adopted research methodologies, sampling sizes, diversity among respondents and the measures of violence. Nevertheless, a few studies have been conducted in Bangladesh to determine the factors instrumental to IPSV in the country (Hadi, Reference Hadi2010; Sambisa et al., Reference Sambisa, Angeles, Lance, Naved and Curtis2010; Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Hoque and Makinoda2011; Naved, Reference Naved2013; Islam et al., Reference Islam, Mazerolle, Broidy and Baird2017; Sanawar et al., Reference Sanawar, Islam, Majumder and Misu2019). Most previous studies, as envisaged, have focused on a limited number of risk factors. The current study attempted to expand the number of risk factors likely to be instrumental to intimate partner sexual violence (IPSV).

Methods

The study adopted a cross-sectional research design involving married women aged from 15–49 years. Applying both qualitative and quantitative approaches, focus group discussions (FGDs) and the social survey method were used to collect data from the targeted respondents.

Setting

An area in Kandigoan Union Parishad, Sylhet Sadar Upazila, Bangladesh, was selected as the study area. A national survey in 2011 found the prevalence of sexual violence in the area to be 19.8% (BBS, 2011). This rural area was selected as it was situated outside the city corporation area, which had a lower level of reported IPV than the rural area. The literacy rate of Kandigoan Union Parishad was reported to be 45.6% in Bangladesh’s most recent literacy survey (BBS, 2011).

Sampling

A two-step cluster sampling procedure was applied to determine the sample size. According to the 2011 Census, 7186 married women aged 15–49 years lived in Kandigoan Union Parishad (BBS, 2011). Kandigoan Union Parishad is divided into nine subunits or wards; three (Wards 1, 3 and 5) were selected randomly then 250 married respondents aged 15–49 years selected using the simple random sampling technique of Cochran’s sample size calculation formula (Cochran, Reference Cochran1963). The t-value for selection of the alpha level of 0.025 in each tail was 1.96; the estimate of variance was 0.25; and the acceptable margin of error for the proportion was 0.05.

Data collection

Data were collected from January to March 2017 through face-to-face interviews by four qualified female field investigators conversant in the local dialect and familial culture. These were well trained in data collection data techniques before deployment in the field, including management of any emotional stress experienced by respondents. The study’s objectives were explained to each respondent, and their verbal consent was obtained before starting data collection. Respondents voluntarily agreed to participate in the study with neither money nor a gift provided in exchange for their time. Interviews were conducted at the respondent’s house at a convenient mutually agreed time. Care was taken to ensure privacy, with interviews taking place in respondent’s living rooms or other private place where they could not be overheard. Respondents were free to skip questions they felt uncomfortable answering. They were assured that the confidentiality of their data would be strictly maintained at all stages of the study.

Variables

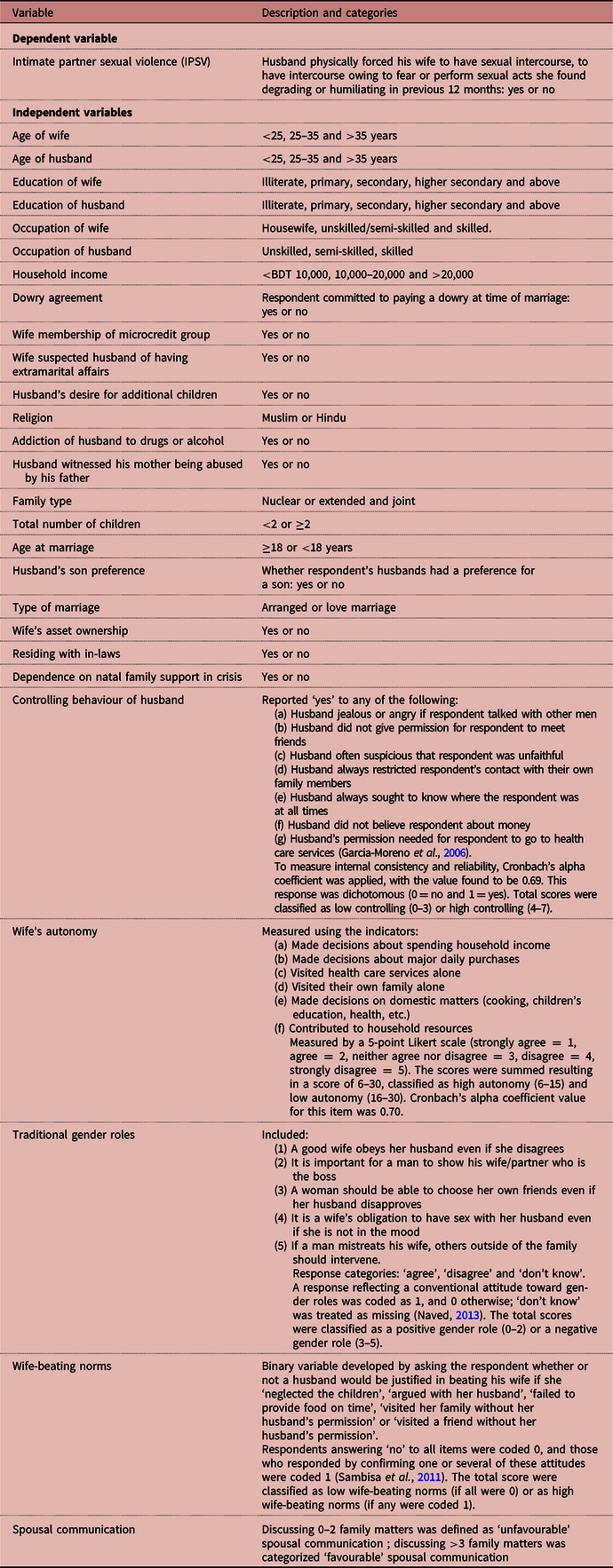

Table 1 summarizes the study variables and their categories. The dependent variable was ‘experienced intimate partner sexual violence (IPSV) in the last 12 months’. Independent variables were: age of wife (years); age of husband (years); education of wife; education of husband; occupation of wife; occupation of husband; household income; wife committed to paying dowry; wife member of a microcredit group; wife suspected husband of having extramarital affairs; spousal communication; autonomy of wife; husband’s attitude towards gender roles; husband’s desire for additional children; husband witnessed his mother being abused by his father; husband’s controlling behaviour; husband addicted to drugs or alcohol; husband’s attitude towards wife-beating (‘wife-beating norms’); family type; wife’s age at time of marriage; husband’s son preference; type of marriage; wife’s asset ownership; couple residing with in-laws; and dependency on natal family support during crises.

Table 1. Definitions of study variables

Data analysis

Univariate, bivariate and multivariate techniques were applied, in addition to percentage analysis, for data analysis to interpret the collected primary data. Cross-tabulation and chi-squared tests were then applied to measure the association between independent and dependent variables. The multiple logistic regression model was next applied to measure the effect on IPSV of various factors. The logistic regression model then included the variables found to be most significant in bivariate analysis.

A multiple logistic regression model was employed to measure the probability of women experiencing IPSV during the previous 12 months. The dependent variable (IPSV) was coded ‘1’ if the respondent experienced IPSV, and ‘0’ if she did not. Binary logistic regression analysis was used as the dependent variable was nominal as women either experienced IPSV or they did not. For each of the two outcome variables, a binary choice model was involved, with this taking a linear form as presented below:

logit P = ln (P/(1−P) = B 0+B 1 wife’s age+B 2 husband’s age + B 3 dowry commitment + B 4 wife member of a microcredit group+B 5 wife suspected husband of having extramarital affair + B 6 spousal communication + B 7 wife’s education + B 8 husband’s education + B 9 wife’s occupation + B 10 wife’s autonomy + B 11 household income + B 12 husband saw mother abused by father + B 13 husband’s controlling behaviour + B 14 husband’s desire for additional children + B 15 husband’s alcohol consumption + B 16 wife’s asset ownership + B 17 dependency on natal family support during crisis + B 18 age at marriage + … e

where B 1, B 2, B 3, B 4… represent the coefficients of each predictor variable, B 0 is the intercept, while e is an error term and ln(P/(1–P) represents the natural logarithm of the odds of the outcome.

Results

Background characteristics

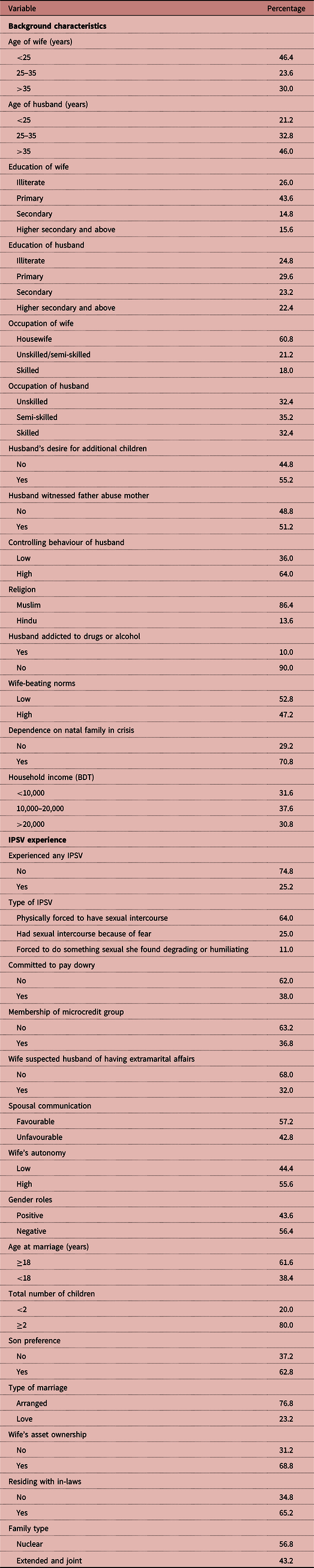

Table 2 shows the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the respondents. A quarter (25.2%) of respondents claimed to have experienced sexual violence during the previous 12 months. Among them, 67.0% reported that their husbands had physically forced them to participate in sexual intercourse, followed by 25.0% who had sexual intercourse with their husbands out of fear and 11.0% were forced to do something sexual that they found degrading or humiliating.

Table 2. Background characteristics and reported IPSV of married women aged 14–49 years, rural Bangladesh, N = 250

As is usual in Bangladesh, wives were mostly younger than their husbands, irrespective of their level of education or other background characteristics. Illiteracy was prominent in the study area, with about a quarter (26.0%) of respondents being illiterate. Most (60.8%) were housewives, as is usually the case in Bangladesh. Thirty-eight per cent reported that they were committed to paying dowry during their marriage, although this is against the country’s laws. Likewise, 32% of respondents suspected that their husbands had extramarital affairs about which they were kept in the dark. Nevertheless, a progressive view was found, with most respondents (55.6%) expressing the opinion that they had a high level of autonomy in the household, despite having experienced VAW.

Likewise, as members of a patriarchal society, husbands were accustomed, to a greater extent, to controlling their wives’ behaviour, with this reported by 64.0% of respondents. More than half (52.8%) of respondents pointed out that their husbands considered wife-beating to be a natural phenomenon. Child marriage was also noticeable among the respondents, with 38.4% marrying before the age of 18.

Bivariate analysis associations

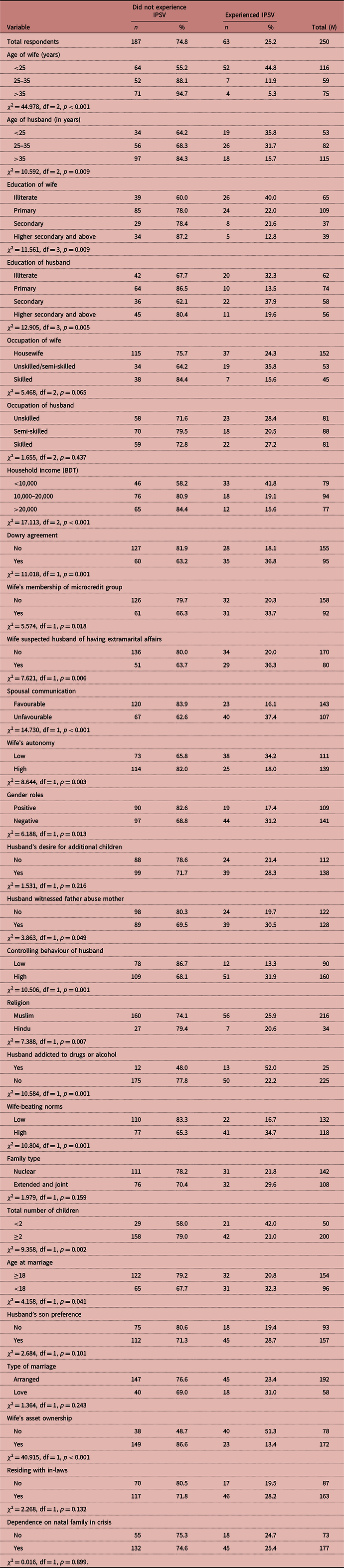

Table 3 shows the results of the bivariate analysis of the association between reported IPSV in the previous 12 months and background variables. The prevalence of IPSV was high (44.8%) among those in the younger age group (<25 years), but only 5.3% among those aged over 35 years. It was also dependent on wife’s educational level and was found to be higher (40.0%) among illiterate women than those who were highly educated (12.8%). The IPSV prevalence was 24.3% among respondents who were not involved in income-generating activities (housewives), but higher (35.8%) among those who were working in unskilled and semi-skilled jobs. However, the rate was much lower (15.6%) among respondents with skilled jobs.

Table 3. Bivariate association between risk factors and IPSV

The rate of IPSV was high (41.8%) when respondents’ household income was less than 10,000 Bangladeshi taka (BDT). However, it decreased to 19.1% among respondents with higher household incomes ranging from BDT 10,000 to BDT 20,000. The rate of IPSV was the lowest (15.6%) among respondents with incomes above BDT 20,000.

The rate of IPSV was also associated with the dowry agreement. Just over a third (36.2%) of respondents who were committed to paying a dowry experienced IPSV, whereas the proportion was nearly one-fifth (18%) among respondents who did not have this commitment. Regarding membership of microcredit groups, IPSV increased from 20.3% to 33.7% (approximately 13.4 percentage points) for respondents who were members of microcredit groups.

The rate of IPSV was also dependent on respondents’ autonomy; high level of autonomy was associated with a significantly lower rate of IPSV (18.0%) than a low level of autonomy (34.2%). Husbands’ attitude towards gender roles had a noticeable association with rate of IPSV, with 31.2% of respondents of husbands with negative suffered IPSV compared with 17.4% of those with positive attitudes. Similarly, the IPSV rate was higher among respondents (31.9%) whose husbands had a high level of control over their wives’ behaviour compared with those (13.3%) whose husbands demonstrated a low level of control. Regarding husband’s wife-beating norms, IPSV was higher (34.7%) among respondents whose husbands had wife-beating norms compared with those who did not. Respondents living in an extended family experienced a higher rate of IPSV compared with those in a nuclear family (29.6% vs 21.8%). Similarly, the rate of IPSV was higher in the case of respondents with fewer than two children (42.0%), and among those whose husbands had a preference for having a son (28.7%) or who had a desire for additional children (28.3%). The rate of IPSV was higher in love marriages than in arranged marriages (31.0% vs 23.4%). In contrast, the rate of IPSV was considerably lower among respondents who owned assets (13.4%), who did not depend on their natal family’s support (24.7%) or who did not live with their in-laws (19.5%), compared with their counterparts.

From the chi-squared test results, husband’s occupation, family type, type of marriage, dependence on natal family support during a crisis, residing with in-laws and husband’s son preference were not found to be significant, so these were excluded from the logistic regression analysis.

Logistic regression analysis results

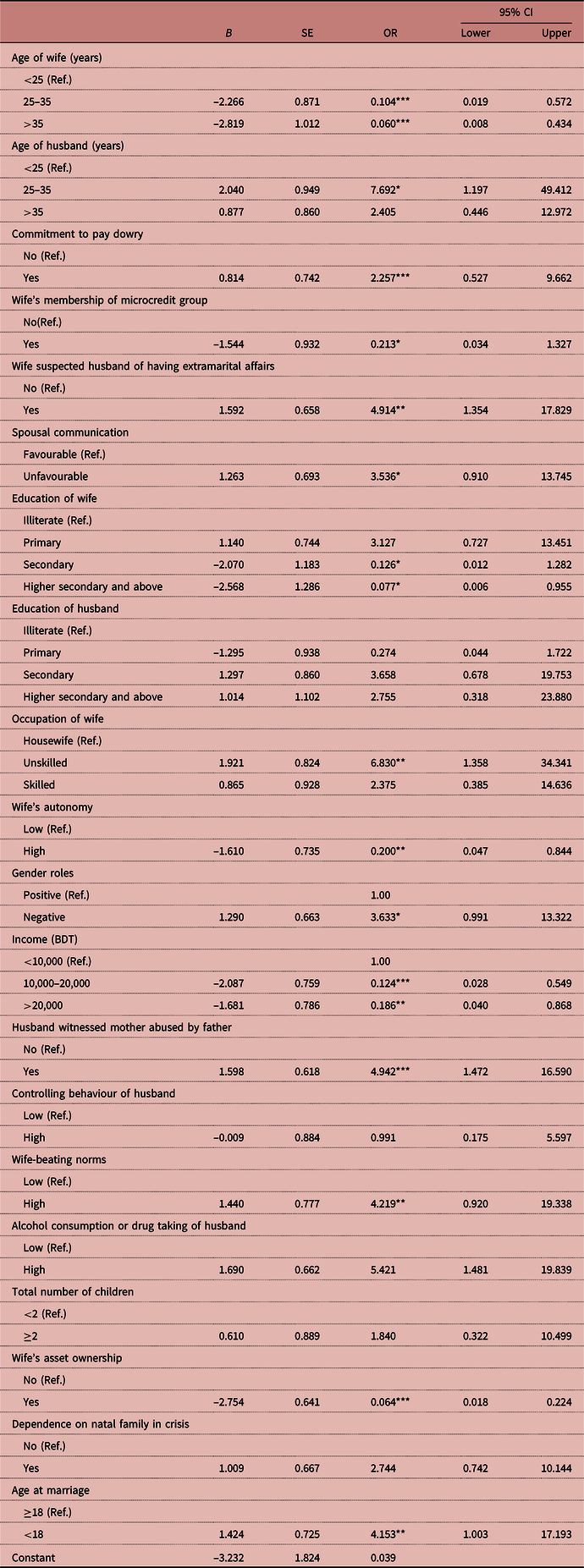

Table 4 shows the results of the logistic regression analysis including the variables found to be significant in the bivariate analysis: age of wife; age of husband; wife’s education; husband’s education; wife’s occupation; household income; wife committed to pay dowry; wife’s membership of microcredit group; wife suspected husband of having extramarital affairs; spousal communication; wife’s autonomy; husband’s attitude towards gender roles; husband seen his mother abused by his father; husband’s controlling behaviour; wife-beating norms; husband’s alcoholism; wife’s asset ownership; dependence on natal family support during a crisis; and age at marriage.

Table 4. Logistic regression results with IPSV determinants

*p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Ref. = reference category; B = unstandardized coefficient; SE = standard error.

Older age of respondents was found to be a significant protective factor for IPSV, with women aged 25–35 years and those aged over 35 being, respectively, significantly 0.104 times less likely (OR = 0.104; 95% CI = 0.019–0.572) and 0.060 times less likely (OR = 0.060; 95% CI = 0.008–0.434) to report IPSV, compared with those younger than 25 years. Similar to the bivariate analysis results, the logistic model showed significant differences in IPSV by level of education, with education, and especially higher levels of education, affecting IPSV in a strong negative way.

Again, respondent’s employment status was a strong predictor of experiencing IPSV. Unskilled working women were more likely to experience IPSV (OR = 6.830; 95% CI = 1.358–34.341) than housewives. Women whose household income ranged from BDT 10,000 to 20,000, and those whose income was over BDT 20,000, respectively, were 0.124 times less likely (OR = 0.124; 95% CI = 0.028–0.549) and 0.186 times less likely (OR = 0.186; 95% CI = 0.040–0.868) to have experienced IPSV, compared with those whose household income was less than BDT 10,000. Respondents who were committed to pay a dowry during their marriage also reported a higher IPSV rate.

As expected, husbands’ extramarital affairs significantly increased the IPSV risk. The odds of IPSV were 4.914 times higher (OR = 4.914; 95% CI = 1.354–17.829) if wives suspected their husbands were having extramarital affairs, compared with those whose husbands were not. The odds of IPSV were 3.536 times higher (OR = 3.536; 95% CI = 0.910–13.745) among respondents who had unfavourable spousal communication compared with those with favourable spousal communication.

Theoretically, wives’ autonomy should have a significant effect on the IPSV rate. This theoretical expectation was confirmed by the finding that respondents were much less likely (OR = 0.200; 95% CI = 0.047–0.844) to report IPSV if they had a high level of autonomy compared if they had less autonomy. The odds of IPSV were 4.942 times higher (OR = 4.942; 95% CI = 1.472–16.590) for respondents whose husbands had witnessed their mothers being abused by their fathers compared with if they had not.

As expected, husband’s wife-beating norms had a significant influence on the IPSV prevalence among respondent women. The odds of experiencing IPSV were more than four times higher among respondents whose husbands had wife-beating norms compared with those whose husbands who did not. As in the bivariate analysis results, regression analysis showed that IPSV was more than four times higher among respondents whose husbands took drugs or drank alcohol compared with those whose husbands did not. Ownership of assets appeared to be a protective factor against ISPV, significantly reducing the likelihood of IPSV. The risk of IPSV was more than four-fold higher (OR = 4.153; CI = 1.003–17.193) among respondents who married before the age of 18 compared with those who married after the age of 18.

Discussion

The study found that the prevalence of sexual violence (IPSV) against married women aged 15–49 years in this rural area of Bangladesh was 25.2%. The sexual violence reported by these women was upsetting, with some reporting their husbands forcing them to engage in sexual intercourse during menstruation or illness. Some reported that their husbands verbally abused them to fulfil their desire for sex, swearing at them if they denied them sex. Das et al. (Reference Das, Bhattacharyya, Alam and Pervin2016), in their study in Bangladesh, reported that in extreme instances, husbands would use a cloth gag to stop their wives make a noise during sexual intercourse.

The study revealed that the commitment to pay a dowry at the time of marriage increased the likelihood of a woman suffering IPSV, with partial or non-payment of dowry sometimes leading increasing IPSV severity. Similar results were found by Naved (Reference Naved2013) in their study in Bangladesh, who found that the level of sexual violence by husbands was 1.91 times higher for those who had dowry agreements during their marriages than for those who did not. Dowry demands at the time of marriage have even been found to be associated with IPSV during pregnancy (Islam et al., Reference Islam, Mazerolle, Broidy and Baird2017). By applying different types of abuse, husbands exert continuous pressure on their wives to receive monetary support from their parents-in-law. A dowry also increases the status and security of a young wife in her husband’s house. A large dowry reduces inter-spousal violence as it increases the resource base of the couple’s household. Women with autonomy to control the dowry have a lower likelihood of domestic violence than those who have no control over the dowry (Srinivasan & Bedi, Reference Srinivasan and Bedi2007).

The current study identified that husbands having wife-beating norms significantly increased the rate of IPSV in Bangladesh. Sambisa et al. (Reference Sambisa, Angeles, Lance, Naved and Curtis2010) reported that IPSV was 1.57 times higher among husbands who believed in norms in favour of wife-beating compared with those who did not. Wife-beating norms were also associated with husbands’ controlling behaviours, which are rooted in the existing value system. For example, the local saying ‘my husband can rule me as he has the authority’ supports the controlling role of husbands. If a man fails to have control over his wife, his masculinity will be questioned by the male community. This study revealed that almost half the respondents’ husbands had that attitude, with this needing further detailed study to unearth why these norms continue to prevail among Bangladeshi men.

Husbands’ alcohol consumption or drug addiction was a strong determinant of sexual violence, with these men being 1.84 times more likely to commit IPSV compared with those who were not alcoholic or drug addicted (Sambisa et al., Reference Sambisa, Angeles, Lance, Naved and Curtis2010). Similarly, Kimuna et al. (Reference Kimuna, Djamba, Ciciurkaite and Cherukuri2013) found that in India, married women whose husbands drank alcohol were significantly 2.082 times more likely to experience sexual violence than those whose husbands did not drink. In Nepal, women were found to be 1.74 times more likely to experience IPSV if their husbands were alcoholics (Pandey, Reference Pandey2016). Drunk people are more likely to exhibit violent behaviour as alcohol reduces their judgment of socially accepted norms, releases their inhibitions and clouds their judgment (Jewkes, Reference Jewkes2002). Men, when drunk, are more likely to ignore the signs of their wives’ unwillingness to engage in sex, with this, in turn, increasing the incidence of forced marital rape. Alcohol consumption leads perpetrators to exert psychological and physical pressure to gain their sexual satisfaction (Abbey et al., Reference Abbey, McAuslan and Ross1998), even leading men into risky sexual behaviours (Johnson, Reference Johnson2014).

Violence is a learned social behaviour that can be transmitted from generation to generation for both men and women (Naved, Reference Naved2013). A history of abuse of a husband’s mother by his father increases the IPSV risk. For example, in Bangladesh, men who witness their mother being tortured by their father have an increased likelihood (OR = 1.58, 95% CI = 0.05–2.39) of sexual violence against women (Naved, Reference Naved2013). Similarly, in India, husbands who, as children, witnessed their fathers torturing their mothers were three times more likely to sexually coerce their wives compared with husbands who had not witnessed such incidents (Koenig et al., Reference Koenig, Stephenson, Ahmed, Jejeebhoy and Campbell2006). In Nepal, women who had witnessed their fathers abusing their mothers were two times more likely (OR = 1.97, CI = 1.32–2.94) to report IPSV, compared with those who did not witness such abuse (Pandey, Reference Pandey2016). Incidents of witnessed inter-parental aggression in their natal family increases the risk of family abuse in husbands’ intimate relationships as they could reproduce specific types of aggressive behaviour (Hines & Saudino, Reference Hines and Saudino2002).

The current study found that IPSV decreased as the age of respondents increased, and this has been confirmed by previous studies in Bangladesh (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Hoque and Makinoda2011; Naved, Reference Naved2013; Islam et al., Reference Islam, Mazerolle, Broidy and Baird2017; Sanawar et al., Reference Sanawar, Islam, Majumder and Misu2019). However, a contradictory result was found by Singh et al. (Reference Singh, Sinha, Jain, Djamba and Kimuna2015) in India, who found that older women were more likely to experience IPSV than younger women. Older women have been found to have more autonomy in family relationships than younger women; thus, they are more likely to have exposure to the IPSV compared with younger women. However, in Bangladesh, the relationship between age and IPSV is complex. While the current study did not examine the effects of spousal age difference, this factor may also mediate the women’s age–IPSV relationship. In Bangladesh, the traditional marriage practice is that men marry younger women. If the age gap is large, this may create problems in their sexual life, with these couples failing to sexually influence and interest each other. When men are much older than women, this could result in sexual refusal which, in turn, could increase the incidence of coercive sex and violence. A recent study conducted by Sanawar et al. (Reference Sanawar, Islam, Majumder and Misu2019) found that spousal age difference was not significantly associated with IPSV in Bangladesh. However, more research is warranted to explore the influence on IPSV of husband’s and wife’s ages, and the mediating role of spousal age difference.

The incidence of IPSV was significantly higher where wives suspected their husbands of having extramarital affairs. Prior evidence from a study conducted in India supports the view that a husband’s history of extramarital relationships significantly increases the likelihood of coercive sexual intercourse (Koenig et al., Reference Koenig, Stephenson, Ahmed, Jejeebhoy and Campbell2006). This history would ignite family conflict, thereby increasing the risk of violence. In the present study, in many cases wives knew about the extramarital affairs of their husbands, but could not speak out or control their husbands as this might create social pressure on the wives themselves, or they might be abused in different ways. For example, a husband might leave his wife at her parents’ home, threaten her with separation or divorce, or commit verbal or physical violence – all of which the wife would probably to be blamed on the wife.

The study’s regression analysis also revealed that IPSV was not associated with households that relied on the natal family’s support during a crisis. In their study in Bangladesh, Naved and Persson (Reference Naved and Persson2005) found that households reliant on natal family support during a crisis did not have a significant level of IPSV experiences. The current study found that religion was not significantly associated with IPSV, as has been found in some previous studies (Babu & Kar, Reference Babu and Kar2009; Kusanthan et al., Reference Kusanthan, Mwaba and Menon2016). However, other studies (Kimuna et al., Reference Kimuna, Djamba, Ciciurkaite and Cherukuri2013; Sambisa et al., Reference Sambisa, Angeles, Lance, Naved and Curtis2010; Pandey, Reference Pandey2016; Sanawar et al., Reference Sanawar, Islam, Majumder and Misu2019) suggested that religion was associated with IPSV. Sanawar et al. (Reference Sanawar, Islam, Majumder and Misu2019) suggested that quantitative studies had a weakness with regard to measuring the effects of religion on sexually intimate topics, especially in the case of Bangladesh.

Women’s education was found to be the most protective factor against IPSV, with prior evidence supporting the view that women with a higher level of education are less likely to experience sexual violence than their illiterate counterparts (Babu & Kar, Reference Babu and Kar2009; Sambisa et al., Reference Sambisa, Angeles, Lance, Naved and Curtis2010; Kimuna et al., Reference Kimuna, Djamba, Ciciurkaite and Cherukuri2013). In contrast, Sanawar et al. (Reference Sanawar, Islam, Majumder and Misu2019) found that educated women in Bangladesh experienced a higher level of sexual violence than their uneducated counterparts. These authors suggested that educated women had a higher level of autonomy in decision-making in their sexual relationships. These results may vary depending on different social settings where local norms and other traditions are important. The risk of IPV was found to increase in cases where women’s educational status was higher than that of men (Flake, Reference Flake2005). More highly educated women have more freedom than women with lower levels of education, with a higher level of liberty for women increasing their risk of gender-based violence (Jewkes, Reference Jewkes2002). When women are both poor and illiterate, their likelihood of IPSV is higher.

The current study found that IPSV was higher in the poorest households. Sambisa et al. (Reference Sambisa, Angeles, Lance, Naved and Curtis2010) reported that men of poor wealth status and middle wealth status were 1.79 and 1.59 times more likely, respectively, to commit IPSV compared with men of higher wealth status. A similar result was found by Sanawar et al. (Reference Sanawar, Islam, Majumder and Misu2019) among married women in Bangladesh, with the richest women being less likely to be affected by sexual violence than the poorest women. Likewise, the richest households were less likely to experience sexual violence by husbands against their wives in the previous year compared with their poorest counterparts (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Hoque and Makinoda2011). Poverty increases IPSV (Heise & Garcia-Moreno, Reference Heise and Garcia-Moreno2002) as living with poverty-driven stress and frustration and being unable to meet basic household needs provide ready impetus for marital disagreement and thus increase the likelihood of violence. Moreover, the relationship between poverty and IPSV is mediated by stress, which is a vital IPSV risk factor. Poor people have fewer resources for reducing stress, which, in turn, increases the likelihood of IPV (Jewkes, Reference Jewkes2002).

The risk of IPSV was found in this study to be less for wives with a higher level of autonomy, with this confirmed by Singh et al. (Reference Singh, Sinha, Jain, Djamba and Kimuna2015); however, counter-evidence was produced by others (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Hoque and Makinoda2011; Koenig et al., Reference Koenig, Stephenson, Ahmed, Jejeebhoy and Campbell2006) who found no significant association between IPSV and wives’ autonomy (Sambisa et al., Reference Sambisa, Angeles, Lance, Naved and Curtis2010; Islam et al., Reference Islam, Mazerolle, Broidy and Baird2017; Sanawar et al., Reference Sanawar, Islam, Majumder and Misu2019). According to social perceptions in the study community on the relationship between husbands and wives, husbands have the ultimate authority to make all kinds of decisions, even about sexual intercourse. Wives are expected to perform according to the will, or for the pleasure, of their husbands. These social perceptions allow men to exercise authority over their wives, to force them to engage in sexual intercourse and even to torture them if they refuse. However, the association between women’s autonomy and IPSV may also be mediated by other cultural factors, such as male status, level of patriarchal norms and problems associated with manhood and the male ego. Jewkes (Reference Jewkes2002) asserted that the sources of women’s autonomy had various elements, such as education, income and community roles, but these do not all have an equal effect on IPSV in terms of a protective role.

This study found that IPSV was significantly related to woman’s age at marriage. Even though the legal age for women to marry in Bangladesh is 18, about 59% of women marry before that age (NIPORT et al., 2016). Most younger women have little knowledge about sex and fear sexual activity, so this can be a traumatic experience for them (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Schuler, Islam and Islam2004). Girls aged less than 18 when they marry have less ability to make decisions, and lower social status, power and resources than women who marry at, or after, the legal age. Early marriage has been found to reduce a wife’s opportunity for education and increase her dependence on her husband, with these factors increasing the risk of violence (Pandey, Reference Pandey2016).

In India, women who marry before the age of 18 are more likely to experience sexual violence than those who are older when they marry (Kimuna et al., Reference Kimuna, Djamba, Ciciurkaite and Cherukuri2013). Young brides also lack relationship power in the household; thus, their risk of IPV increases (Heise et al., Reference Heise, Ellsberg and Gottmoeller2002). Pandey (Reference Pandey2016) found in Nepal that women who were married by the age of 15 faced 1.71 times higher odds of sexual violence compared with women who were married at or above the age of 20. Garcia-Moreno et al. (Reference Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise and Watts2006) provided evidence supporting the view from the WHO multi-country study that younger women are more likely to report their first sexual intercourse as being coerced, reporting that the global prevalence of first-time forced sex among younger women aged 15 or less ranges from 11% to 45%.

The current study found that wives’ asset ownership reduced the probability of sexual violence. Peterman et al. (Reference Peterman, Pereira, Bleck, Palermo and Yount2017), in their cross-country study, found that asset ownership was negatively associated with sexual or physical IPV in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Pakistan and Honduras. Women’s asset ownership has been found to increase their bargaining power, status and household resources which, in turn, lowers the risk of gender-based violence (Bhattacharyya et al., Reference Bhattacharyya, Bedi and Chhachhi2011). However, the association between asset ownership by women and IPSV is very complex, and dependent on the types of asset owned and the cultural context.

Lack of spousal communication increased the risk of IPSV in the current study. Spousal communication may help to maintain a good relationship between husband and wife (Bhatta, Reference Bhatta2014). Naved (Reference Naved2013) found that a higher spousal communication score reduced the likelihood of IPSV in both rural and urban areas of Bangladesh, which is consistent with the current study’s finding. Having little or no spousal communication was also found to increase the risk of all types of violence against married women in a study conducted in a rural area of Nepal (Lamichhane et al., Reference Lamichhane, Puri, Tamang and Dulal2011). In contrast, Singh et al. (Reference Singh, Sinha, Jain, Djamba and Kimuna2015) found that women were less likely to experience sexual violence if spousal communication addressed reproductive and sexual health matters.

Husband’s attitude towards gender roles were found in the current study to be associated with IPSV. Violence was found to be higher in husband-dominated, than in egalitarian, families. Husbands often use violence as a means of controlling their wives to demonstrate their superiority (Choi & Ting, Reference Choi and Ting2008). Similarly, a husband’s lower level of decision-making power increases the risk of violence, with the risk being higher when he thinks he had less power than his wife. An unsatisfactory power relationship between husband and wife may even increase violence (Choi & Ting, Reference Choi and Ting2008). However, some studies (Koenig et al., Reference Koenig, Stephenson, Ahmed, Jejeebhoy and Campbell2006; Naved, Reference Naved2013; Islam et al., Reference Islam, Mazerolle, Broidy and Baird2017) have found that IPSV is not associated with gender roles. In these contexts, other family members, even the wives’ parents, tend to blame the women for not obeying their husbands, and not doing the right thing for the sake of family peace. Through socialization, women learn to be timid, silent and soft, and to not resist, and react to, their male guardians, including their husbands. These feminine traits were found to support violence against women in the studied community.

Women’s unskilled work was also found, in the current study, to be associated with IPSV. This finding was also reported by Sanawar et al. (Reference Sanawar, Islam, Majumder and Misu2019), who claimed that employed women in Bangladesh were 1.467 times more likely to report IPSV compared with unemployed women. Similarly, working women were 1.47 times more likely to experience IPSV in Bangladesh (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Hoque and Makinoda2011) and 1.6 times more likely to experience sexual violence in Zambia (Kusanthan et al., Reference Kusanthan, Mwaba and Menon2016), compared with their unemployed counterparts. Women who work regularly experience less domestic violence than those whose work is seasonal or on a contractual basis (Panda & Agarwal, Reference Panda and Agarwal2005). Unskilled workers in Bangladesh do not receive employment benefits, such as health care, sick leave or job security, which may affect their well-being. Wives in these situations have to continue these types of abusive relationships as, without their husbands’ support, they lack the financial resources to live (Slabbert, Reference Slabbert2017).

In conclusion, the current study attempted to identify the risk factors for IPSV in a rural setting in Bangladesh. The findings suggest that IPSV is caused by multiple factors, each with a distinctive dynamic and impact. Alcohol consumption and drug use were the most notable risk factors for IPSV being committed by husbands in this society. Likewise, husbands’ extramarital affairs, especially risky sexual behaviour, need to be taken into consideration when designing IPSV prevention programmes. Social norms are a prominent barrier to accessing services from agencies that provide legal and health care support to women. Intervention programmes designed to prevent violence need to address the issue of women’s awareness, including sexual rights and women’s rights. An effective drug prevention policy should be implemented at the community level, and efforts made to change attitudes and norms, especially those that support husbands’ attitudes towards IPSV and wife-beating norms. Strategies should be undertaken to develop husbands’ consciousness of their wives’ equal rights at the household level.

The study had its limitations. As it was a cross-sectional study, it could not establish either causality or the direction of relationships, only IPSV and risk factor associations. The findings cannot be generalized to all of Bangladesh as the sample was not fully representative of the country. The findings were based on data generated from a survey of married women in which the experience of IPSV may not have been reported by some women. Further research comprising a nationwide survey with a causal design is essential for a comprehensive understanding of this multidimensional problem. Despite these limitations, the current study confirms that IPSV is a widely prevalent problem in rural Bangladesh.

Funding

This study was supported by the Bangladesh Institute of Social Research (BISR) trust under the Adjunct Researcher Fellowship programme.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Ethical Approval

No additional ethical approval was required for this study.