Introduction

In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), adolescents girls and young women (AGYW) aged 15–24 years continue to be disproportionately affected by HIV (UNAIDS, 2017). Each year, about 380,000 AGYW become infected with HIV globally, of which 80% are living in SSA (UNAIDS, 2014). This heightened risk and vulnerability to HIV acquisition among AGYW in SSA can be attributed to a complex interplay of biological, structural, behavioural and social factors (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Beutel and Maughan-Brown2007; Idele et al., Reference Idele, Gillespie, Porth, Suzuki, Mahy, Kasedde and Luo2014; Kenu et al., Reference Kenu, Obo-Akwa, Nuamah, Brefo, Sam and Lartey2014; Asaolu et al., Reference Asaolu, Gunn, Center, Koss, Iwelunmor and Ehiri2016). The majority of new HIV cases among AGYW in SSA are due to risky sexual behaviours such as low condom use, early sexual debut, having multiple sexual partners, engaging in transactional sex, poor HIV knowledge and low HIV risk perceptions (Simbayi et al., Reference Simbayi, Chauveau and Shisana2004; Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Beutel and Maughan-Brown2007; Puffer et al., Reference Puffer, Meade, Drabkin, Broverman, Ogwang-Odhiambo and Sikkema2011; Kenu et al., Reference Kenu, Obo-Akwa, Nuamah, Brefo, Sam and Lartey2014).

In Ghana, the 2015 report from the Ministry of Health indicated a rapid increase in new HIV infections among young people, especially among AGYW aged 15–24 years (MoH, 2015a). This is quite alarming given that Ghana’s Ministry of Health reported a relatively low HIV prevalence rate (1.2%) among young people aged 15–24 in 2014 (MoH, 2013, 2015a, 2015b). By 2017, the prevalence rate of HIV among this population increased by 45% (MoH, 2016), with AGYW accounting for more than half of this (MoH, 2016). Despite this high HIV prevalence rate among AGYW in Ghana, HIV testing remains low – less than 30% of this population have ever tested for HIV (GDHS, 2015). To reduce the growing burden of HIV among AGYW, there is a critical need to increase HIV testing. HIV testing is an important entry-point to reach undiagnosed individuals and to link people living with HIV to prompt and adequate care (Branson et al., Reference Branson, Handsfield, Lampe, Janssen, Taylor, Lyss and Clark2006). Early screening and diagnosis will ensure that Ghana is on target to achieve the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS) 90-90-90 goals, which aims to ensure that 90% of people living with HIV know their HIV status by 2020 (UNAIDS, 2015). This target has now been revised for countries to meet a 95-95-95 goal by 2030 (UNAIDS, 2015). Ghana’s 2016–2020 National HIV and AIDS Strategic Plan (NSP) mirrors the UNAIDS target to achieve the 90-90-90 testing and treatment targets by 2020 (MoH, 2016).

Low uptake of HIV testing among young people can be explained partly by anticipated stigma and discrimination associated with HIV, poor comprehensive HIV knowledge, lack of knowledge about existing services, low risk perception and fear of testing outcomes (Musheke et al., Reference Musheke, Ntalasha, Gari, Mckenzie, Bond, Martin-Hilber and Merten2013; Kurth et al., Reference Kurth, Lally, Choko, Inwani and Fortenberry2015; Sam-Agudu et al., Reference Sam-Agudu, Folayan and Ezeanolue2016). These barriers undermine efforts to increase HIV testing and highlight the critical need to increase the uptake of HIV testing among AGYW. While there is an extensive body of literature on the socio-demographic, behavioural and socioeconomic determinants of HIV testing among young people in Ghana (Andoh-Robertson, Reference Andoh-Robertson2018; Gyasi & Abass, Reference Gyasi and Abass2018) and SSA (Musheke et al., Reference Musheke, Ntalasha, Gari, Mckenzie, Bond, Martin-Hilber and Merten2013; Asaolu et al., Reference Asaolu, Gunn, Center, Koss, Iwelunmor and Ehiri2016; Sam-Agudu et al., Reference Sam-Agudu, Folayan and Ezeanolue2016; Gyasi & Abass, Reference Gyasi and Abass2018), the role of socio-cultural factors such as ethnicity has not been extensively explored. Studies have shown that fundamental factors that foster or hinder specific health behaviours among young people in SSA are deeply rooted within socio-cultural contexts that shape their lives (Wight et al., Reference Wight, Plummer and Ross2012; Iwelunmor et al., Reference Iwelunmor, Blackstone, Jennings, Converse, Ehiri and Curley2018). For instance, socio-cultural factors exhibited through cultural gender norms, cultural beliefs and practices have been found to significantly influence sexual and reproductive health behaviours such as contraceptive use (Imasiku et al., Reference Imasiku, Odimegwu, Adedini and Ononokpono2014; Okigbo et al., Reference Okigbo, Speizer, Domino, Curtis, Halpern and Fotso2018), engaging in risky sexual behaviours (Odimegwu et al., Reference Odimegwu, Somefun and Chisumpa2018) and HIV testing (Gyasi & Abass, Reference Gyasi and Abass2018; Perkins et al., Reference Perkins, Nyakato, Kakuhikire, Mbabazi, Perkins and Tsai2018).

Ethnicity is an important socio-cultural factor shown to influence health behaviour in SSA (Gyimah, Reference Gyimah2002; Ononokpono et al., Reference Ononokpono, Odimegwu, Adedini and Imasiku2016). The role of ethnicity in health behaviour can be explained by the unique socio-cultural practices, values and beliefs within ethnic groups that could positively or negatively impact health outcomes (Ononokpono et al., Reference Ononokpono, Odimegwu, Adedini and Imasiku2016). In the African context, the strong sense of identity and solidarity attributed to one’s ethnicity partly explains the ability of culture to shape health behaviours (Imasiku et al., Reference Imasiku, Odimegwu, Adedini and Ononokpono2014). For instance, some HIV prevention studies have found associations between ethnicity and sexual behaviours among young people (Sambisa et al., Reference Sambisa, Curtis and Stokes2010; Odimegwu et al., Reference Odimegwu, Somefun and Chisumpa2018). A study in Ghana found ethnic variations in sexual debut, such that women from the majority ethnic group Akan were more likely to have early sexual debut compared with women from other ethnic groups (Amoateng & Baruwa, Reference Amoateng and Baruwa2018). In Ghana, ethnic groups may differ in their conceptualization of sexual behaviours among young women (Amoateng & Baruwa, Reference Amoateng and Baruwa2018). Unlike other ethnic groups in Ghana, Akan is matrilineal. This translates to women from this ethnic group having a level of independence and autonomy not experienced by non-Akan women (Takyi & Nii-Amoo Dodoo, Reference Takyi and Nii-Amoo Dodoo2005). Similarly, studies in Zimbabwe and Nigeria have also found associations between ethnicity and sexual behaviour among young people between 15–24 years, even after controlling for socio-demographic and socio-cognitive factors (Sambisa et al., Reference Sambisa, Curtis and Stokes2010; Mberu & White, Reference Mberu and White2011; Odimegwu et al., Reference Odimegwu, Somefun and Chisumpa2018). Although limited research has been conducted to examine the role of ethnicity and HIV testing specifically, a study in Uganda found that perception of cultural norms around HIV testing can predict an individual’s likelihood of testing for HIV (Perkins et al., Reference Perkins, Nyakato, Kakuhikire, Mbabazi, Perkins and Tsai2018).

Based on the foregoing, there is an extensive body of empirical literature on factors that influence the uptake of HIV testing. However, a study explaining the influence of a socio-cultural factor such as ethnicity on HIV testing among young people in Ghana is yet to be conducted. To address this gap, the primary objective of the study was to examine the influence of ethnicity on HIV testing among AGYW in Ghana. Whilst it is important to acknowledge that socio-cultural factors extend beyond ethnicity, ethnicity serves as a proxy for culture in the context of this study, as previously used in other studies (Fayehun et al., Reference Fayehun, Sanuade, Ajayi and Isiugo-Abanihe2020; Mobolaji et al., Reference Mobolaji, Fatusi and Adedini2020).

Conceptual framework

The study was guided by the PEN-3 cultural model (Airhihenbuwa & Webster, Reference Airhihenbuwa and Webster2004), which is widely used to explain the role of culture on health behaviour (BeLue et al., Reference BeLue, Okoror, Iwelunmor, Taylor, Degboe, Agyemang and Ogedegbe2009; Iwelunmor et al., Reference Iwelunmor, Newsome and Airhihenbuwa2014, Reference Iwelunmor, Sofolahan-Oladeinde and Airhihenbuwa2015; Okoror et al., Reference Okoror, Belue, Zungu, Adam and Airhihenbuwa2014). This model provides a framework to assess the impact of cultural diversity resulting from the multi-ethnic nature of African countries like Ghana on health behaviours and health outcomes (Airhihenbuwa & Webster, Reference Airhihenbuwa and Webster2004). The model suggests that three primary domains explain the role of culture in health behaviours, namely: 1) cultural identity (CI), 2) relationships and expectations (RE), and 3) cultural empowerment (CE) (Airhihenbuwa, Reference Airhihenbuwa2007). This study focused on the cultural identity and relationship and expectations domains.

Based on the application of the PEN-3 model, HIV testing is determined most proximally by cultural identity factors. In this study, the focus was on the role of ethnicity as an indicator of cultural identity in HIV testing. The PEN-3 model suggests that ethnicity is an important marker of cultural identity (Airhihenbuwa & Webster, Reference Airhihenbuwa and Webster2004; Airhihenbuwa et al., Reference Airhihenbuwa, Ford and Iwelunmor2014) and has been found to play a critical role in health behaviours in SSA. Other CI domains such as neighbourhood factors, family members and family structures are also important determinants of health behaviour (Russell et al., Reference Russell, Coleman and Ganong2018). In terms of family structure, studies have found that female-headed households are less likely to access health services, because of limited access to the economic resources within the household (Schatz et al., Reference Schatz, Madhavan and Williams2011; Van Rooyen et al., Reference Van Rooyen, Stewart and De Wet2012). This hinders their ability to use health services, such as HIV testing services. Likewise, place and region of residence are important CI domain factors that are associated with HIV testing (Asaolu et al., Reference Asaolu, Gunn, Center, Koss, Iwelunmor and Ehiri2016). Subsequently, cultural identity domains influence relationships and expectations. Relationship and expectations (RE) factors include knowledge, beliefs and values that influence decision-making towards health behaviours and practices (Ambasa-Shisanya, Reference Ambasa-Shisanya2009). They are grouped into ‘perceptions’, ‘nurturers’ and ‘enablers’. Relationships and expectations include resources and other factors that encourage or discourage health behaviours (Ambasa-Shisanya, Reference Ambasa-Shisanya2009). Overall, an individual’s construction and interpretation of health behaviour are influenced by their perception, the resources that enable or limit their actions towards health and the influence of their relationships (family and friends) in either encouraging or discouraging behaviour change (Iwelunmor et al., Reference Iwelunmor, Sofolahan-Oladeinde and Airhihenbuwa2015). Furthermore, HIV knowledge, marital status and knowledge of a testing location have been found to be important determinants of HIV testing (Asaolu et al., Reference Asaolu, Gunn, Center, Koss, Iwelunmor and Ehiri2016; Iwelunmor et al., Reference Iwelunmor, Blackstone, Jennings, Converse, Ehiri and Curley2018).

Guided by the conceptual framework (Figure 1), which was informed by the PEN-3 cultural model and existing literature, the following hypotheses were proposed: 1) ethnicity is associated with HIV testing among AGYW in Ghana, and 2) after controlling for CI and RE domain factors, ethnicity will be associated with HIV testing among AGYW in Ghana.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework explaining the link between ethnicity and HIV testing among adolescent girls and young women in Ghana.

Methods

Study area

Ghana is made up of an ethnically diverse population of over 27.4 million people (GhanaStatistics, 2017). There are over 100 ethnic groups in Ghana, with Akan, Mole-Dagbon, Ewe, Ga-Dangme and Gurma being the largest (Mancini, Reference Mancini2009). Ethnic groups are identified based on language, geographical origin, social systems and cultural practices (Takyi & Addai, Reference Takyi and Addai2002).

Data source

Data were from the 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey (GDHS). This is a nationwide cross-sectional survey that is conducted every 5 years covering all ten administrative regions in Ghana (GDHS, 2015). In 2019, the ten regions were further divided into sixteen regions (BusinessGhana, 2019), but this study only focused on the ten regions as reported in the 2014 GDHS. The Demographic and Health Surveys collect information on various demographic and health issues, including HIV and contraceptive use (Kruk et al., Reference Kruk, Johnson, Gyakobo, Agyei-Baffour, Asabir and Kotha2010). The 2014 GDHS followed a two-stage sampling strategy. First, clusters comprising enumeration areas (EAs) were randomly selected, then households within the EAs were systematically sampled. Face-to-face interviews were conducted among 9659 women and 4609 men with a response rate of 97% and 95%, respectively (Kruk et al., Reference Kruk, Johnson, Gyakobo, Agyei-Baffour, Asabir and Kotha2010). The GHDS collects data using questionnaires tailored to men, women, and households. Further details on the survey design, methodologies and questionnaires are described elsewhere (GDHS, 2015). This study was restricted to the sample from the women’s questionnaire. The analytical sample was restricted to young people (females) aged 15–24 who responded to the question ‘Have you ever been tested for HIV?’ Participants who had a missing value for this question were excluded (n = 2). The final sample size for the analysis was 3325. Figure 2 presents the sample selection process.

Figure 2. Sample selection flowchart.

Variables and covariates

Dependent variable

The primary dependent variable was ‘HIV testing’ measured by asking survey participants if they had ever tested for HIV. ‘Yes’ was selected for participants who had ever tested for HIV and ‘no’ for those who stated otherwise.

Independent variable

The primary independent variable was the participant’s ‘ethnicity’, operationalized as an aspect of cultural identity. This was categorized into six groups based on recommendations from other Ghanaian studies (Takyi & Addai, Reference Takyi and Addai2002), coded as: 1 = Akan; 2 = Mole-Dagbon; 3 = Ewe; 4 = Ga/Ganme; 5 = Guan; and 6 = Other. The ‘Other’ ethnic group was comprised of Mande, Gurma, Grusi groups, as well as the ethnic category labelled as ‘other’ in the data set.

Covariates

The selection of covariates for this study was guided by the conceptual framework (Figure 1) and existing empirical evidence on factors associated with HIV testing (Iwelunmor et al., Reference Iwelunmor, Blackstone, Jennings, Converse, Ehiri and Curley2018). Table 1 shows the list of covariates included in the study along with their definitions and categories.

Table 1. Description of covariates included in the study

Cultural identity variables included family structure, place of residence, and region of residence. Relationship and expectations variables included HIV knowledge, condom use, age of sexual debut, multiple sexual partners, marital status, and religion. The following variables were controlled for in the analysis: wealth status, employment status, age and education; these have been found to influence HIV testing among young people (Asaolu et al., Reference Asaolu, Gunn, Center, Koss, Iwelunmor and Ehiri2016).

Data analysis

The analysis was carried out in three steps. First, descriptive statistics were calculated in frequencies and percentages for selected variables, since they were all categorical variables. Second, bivariate analysis using Chi-squared tests was conducted to examine the association of each variable (main independent variable and covariates) with the dependent variable (HIV testing). Thirdly, a logistic regression model was conducted to examine the effect of ethnicity and other predictors on HIV testing among the participants. The variables included in the logistic regression were:

-

Ethnicity

-

All cultural identity factors (family structure, place of residence, region of residence)

-

All relationship and expectations factors (religion, condom use, comprehensive HIV knowledge, marital status, age at sexual debut, engaging in multiple sexual partnerships)

-

All control variables that were significantly associated with HIV testing in the bivariate analysis (education, wealth status, employment status).

Prior to conducting logistic regression, multicollinearity was assessed using correlation matrix and variance inflation factor (VIF) and there were no concerns with collinearity among variables. The results of the logistic regression model are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All data analyses were conducted using SAS University Edition and a significance level of 95% (α = 0.05) was maintained for all tests. The Proc Survey command was used to account for the complex sampling design of the GDHS. Weighting, stratification and clustering variables provided by the DHS survey were used throughout the data analysis.

Results

Descriptive characteristics

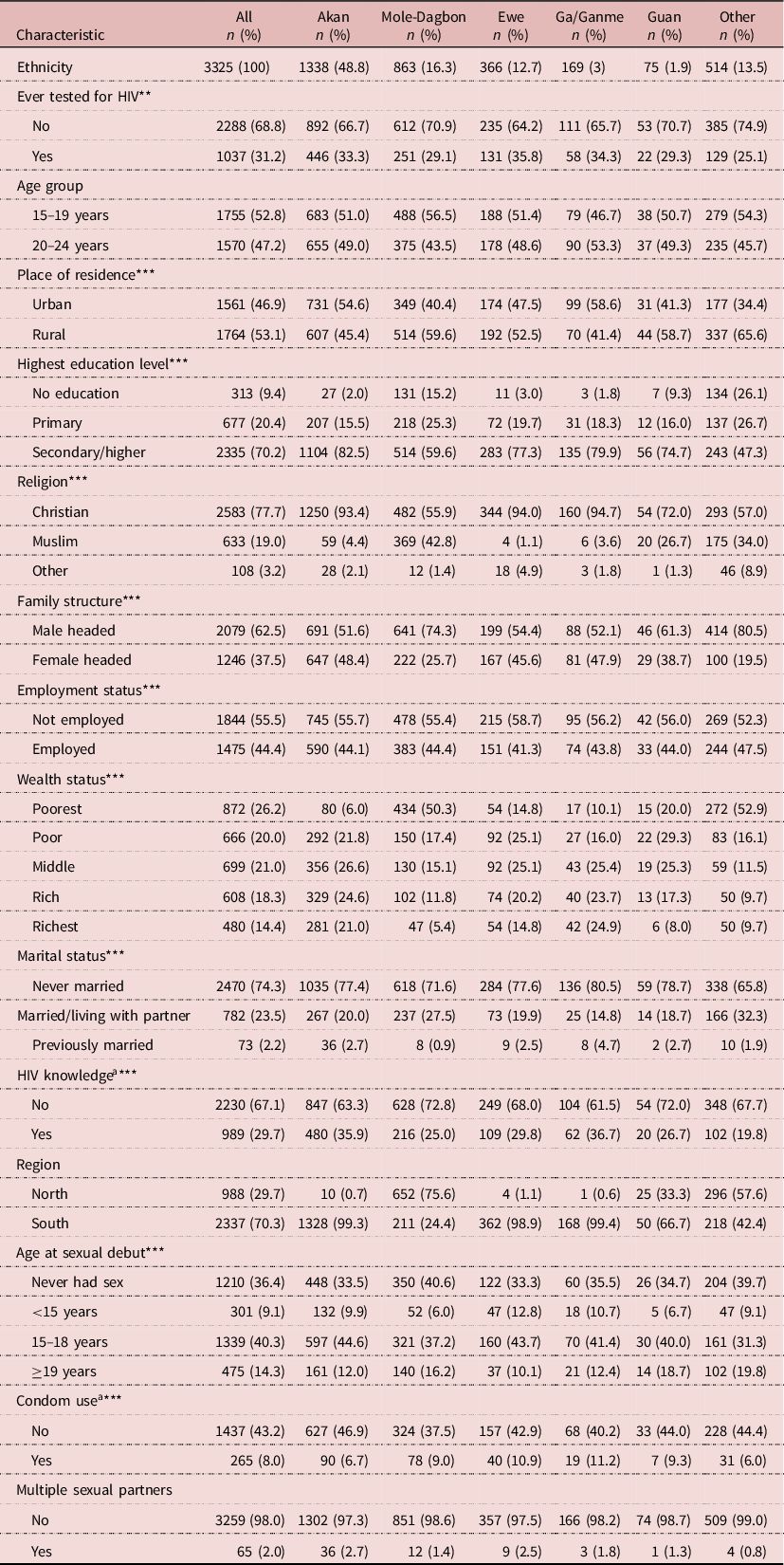

The weighted descriptive statistics of the study sample are presented in Table 2. There were a total of 3325 AGYW participants. Of these, 68% had never tested for HIV, and close to half (49%) belonged to the Akan ethnic group. The participants were almost equally distributed across age groups, rural–urban residence and wealth status categories. The highest proportion had secondary education or higher (74%), were Christians (80%), were never married (82%) and did not have multiple sexual partnerships (98%).

Table 2. Characteristics of adolescent girls and young women by ethnicity, 2013 GDHS (N=3325)

a Sample size slightly less than 3325 due to missing data.

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Bivariate analysis of associations between ethnicity and covariates

Table 2 shows the distribution of the study sample characteristics across the six ethnic categories. The following participant characteristics were statistically associated with ethnicity (p<0.05): ever tested for HIV, place of residence, highest education level, religion, family structure, employment status, wealth status, HIV knowledge, age of sexual debut and condom use. Age, region and multiple sexual partners were not statistically associated with ethnicity (p>0.05).

The results of the bivariate association between HIV testing and selected covariates are presented in Table 3. Ethnicity and several selected covariates were significantly associated with HIV testing (p<0.05). Among the CI domain variables, place of residence (p<0.05) and region of residence (p<0.01) were associated with HIV testing. Most RE domain variables, i.e. HIV knowledge (p<0.05), condom use (p<0.001), religion (p<0.05), marital status (p>0.001) and age of sexual debut (p<0.001), were significantly associated with HIV testing, but having multiple sexual partnerships was not statistically significant. All control variables (highest education level [p<0.01], wealth status [p<0.01], employment status [p<0.001]) except age group were significantly associated with HIV testing.

Table 3. Bivariate analysis of HIV testing by explanatory variables (ethnicity and covariates)

*p<0.05; ** p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Multivariate association

Table 4 presents the results of the logistic regression model fitted to examine the association between ethnicity and HIV testing. The model showed a statistically significant association between HIV testing and ethnic group (p<0.01). Compared with those from the Akan ethnic group, those from the Mole-Dagbon (OR = 0.73, CI: 0.57–0.93) and ‘Other’ ethnic groups (OR = 0.60, CI: 0.44–0.81) were significantly less likely to test for HIV. Participants who were from Ewe (OR = 0.99, CI: 0.74–1.32), Ga/Ganme (OR = 0.91, CI: 0.62–1.33) and Guan (OR = 0.72, CI: 0.36–1.45) ethnic groups also had lower odds of testing for HIV compared with those from the Akan ethnic group. However, this association was not statistically significant.

Table 4. Logistic regression models of the association between HIV testing and ethnicity, and selected covariates

Bold confidence intervals indicate statistical significance; OR: Odds Ratio; aOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio (adjusted for variables listed in Methods section); CI: confidence interval; AIC: Akaike Information Criterion.

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

The adjusted model, which controlled for all the variables in the conceptual framework, showed that ethnicity was not a significant predictor of HIV testing. The model did, however, show a significant relationship between HIV testing and marital status, having multiple sexual partners, age and condom use. For instance, married (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 4.56, CI: 3.46–6.08) and previously married (aOR = 4.30, CI: 2.00–9.23) participants were significantly more likely to test for HIV compared with those who were never married. Participants between the ages of 20 and 24 years (aOR = 1.88, CI: 1.37–2.58) were significantly more likely to test for HIV than those aged 15–19 years. The odds of testing for HIV were lower for individuals who had multiple sexual partners (aOR = 0.41, CI: 0.20–0.85) compared with their counterparts who did not have multiple sexual partners. Likewise, condom use among study participants resulted in lower odds of HIV testing (aOR = 0.56, CI: 0.38–0.84).

Discussion

Despite high HIV prevalence and incidence rates among adolescent girls and young women in Ghana, HIV testing remains low among this population. To explain this trend, several studies have examined the role of socioeconomic and individual-level factors on HIV testing among this population (Musheke et al., Reference Musheke, Ntalasha, Gari, Mckenzie, Bond, Martin-Hilber and Merten2013; Asaolu et al., Reference Asaolu, Gunn, Center, Koss, Iwelunmor and Ehiri2016; Andoh-Robertson, Reference Andoh-Robertson2018), but there has been little focus on the role of socio-cultural factors. Utilizing the PEN-3 cultural model (Airhihenbuwa & Webster, Reference Airhihenbuwa and Webster2004; Iwelunmor et al., Reference Iwelunmor, Newsome and Airhihenbuwa2014), this study examined the association between ethnicity (an aspect of culture) and HIV testing among AGYW in Ghana. The study was premised on the hypothesis that a greater insight into socio-cultural practices and resources might be salient in understanding differentials in HIV testing. Understanding the relationship between HIV testing and ethnicity in a multi-ethnic country like Ghana is essential to improve the uptake of HIV testing. This improvement can be achieved by maintaining factors within ethnic groups that enable uptake of testing while mitigating factors that discourage uptake.

Although ethnicity was significantly associated with HIV testing in the bivariate model, it ceased to be significant when controlling for the relationship and expectations domain and other cultural identity factors informed by the PEN-3 cultural model (Airhihenbuwa & Webster, Reference Airhihenbuwa and Webster2004; Iwelunmor et al., Reference Iwelunmor, Newsome and Airhihenbuwa2014). This suggests that ethnicity alone may not explain the differences in HIV testing among AGYW in Ghana. This is contrary to the hypothesis that ethnicity will be associated with HIV testing in this population, even after controlling for other explanatory variables highlighted in the conceptual framework. Given these findings, it is evident that while ethnicity is an important component of culture, ethnicity alone may not capture all the cultural values and socio-cultural factors that influence HIV testing. Therefore, the role of other aspects of culture cannot be ruled out. An extensive body of literature shows the link between health behaviour and culture in SSA (Gyimah, Reference Gyimah2002; Takyi & Addai, Reference Takyi and Addai2002; Airhihenbuwa & Webster, Reference Airhihenbuwa and Webster2004). Given that an individual’s ethnic group does not change, ethnicity may explain differences in demographic and economic factors that hinder or foster access to health resources. A growing body of literature also suggests that ethnic differentials in health outcomes may be influenced by underlying socioeconomic and demographic factors that foster health inequalities (Gyimah, Reference Gyimah2002; Imasiku et al., Reference Imasiku, Odimegwu, Adedini and Ononokpono2014). Therefore, it is important for future studies to explore how differences in socioeconomic factors across ethnic groups may explain HIV testing, and further explore specific cultural factors that may influence HIV testing among adolescent girls and young women in Ghana. Moreover, an individual’s ethnicity and cultural background influences their overall health (Airhihenbuwa, Reference Airhihenbuwa1994) and perception of disease states, as well as their receptiveness to preventative interventions.

In this study, marital status, condom use and engaging in multiple sexual relationships were the most significant predictors of HIV testing among AGYW in Ghana. Participants who were married or previously married were more likely to test for HIV compared with those who were never married. This association has also been found in other studies where individuals who were married were more likely to test compared with their unmarried counterparts (Salazar-Austin et al., Reference Salazar-Austin, Kulich, Chingono, Chariyalertsak, Srithanaviboonchai and Gray2018). Among sexually active participants, individuals who used condoms were less likely to test for HIV. This is inconsistent with previous findings that have found condom use to be associated with an increased likelihood of HIV testing among young people (Salazar-Austin et al., Reference Salazar-Austin, Kulich, Chingono, Chariyalertsak, Srithanaviboonchai and Gray2018). In a study across four countries (South Africa, Zimbabwe, Tanzania and Thailand), higher condom use was associated with HIV testing among young people aged 14–24 years (Salazar-Austin et al., Reference Salazar-Austin, Kulich, Chingono, Chariyalertsak, Srithanaviboonchai and Gray2018). This finding does not align with the proposed conceptual framework of this study, which hypothesized that HIV preventive behaviour such as condom use would encourage uptake of HIV testing. The alternative findings could be as a result of low HIV risk perception among individuals engaging in protected sex. Similar to previous studies, the study found that young women with multiple sexual partners were less likely to test for HIV compared with those reporting single sexual partnership (Salazar-Austin et al., Reference Salazar-Austin, Kulich, Chingono, Chariyalertsak, Srithanaviboonchai and Gray2018). Nonetheless, as stated previously, findings from several studies suggest that there is a low perception of risk among individuals engaging in risky sexual behaviours, such as multiple sexual partners (Tan & Black, Reference Tan and Black2018; Warren et al., Reference Warren, Paterson, Schulz, Lees, Eakle, Stadler and Larson2018). This may explain the discordance in HIV testing among individuals engaging in risky sexual behaviours.

The study has its limitations. Given the cross-sectional nature of the data source, casual associations with HIV testing among AGYW in Ghana could not be concluded. Nonetheless, the focus of the study was not to determine the causal relationship but to assess if there were any variations in HIV testing across ethnic groups. Also, the measure of cultural norms using ethnicity as a proxy does not quite account for the nuances within different cultures in Ghana. Ethnic groups with small sample sizes were merged into one category for the analysis. This categorization may have limited the ability to consider variation across minority ethnic groups. Nonetheless, this study provides a basis for further investigation on the role of cultural factors on health behaviours such as HIV testing among young people in SSA. Future studies could extend this work by conducting qualitative studies to carefully delineate the cultural and religious characteristics within ethnic groups in Ghana, and the socioeconomic factors (i.e. income and employment) that may be an indication of the perceived economic burden of HIV testing. Capturing this vital information may explain the variations in HIV testing across the different ethnic groups. Despite these limitations, this study had several strengths. First, the data source used for this study was nationally representative – the GDHS dataset. This is a credible data source with rigorous data collection design and a high response rate (GDHS, 2015). Second, this is one of the first studies to assess the association between ethnicity and HIV testing among AGYW in Ghana. This information could be useful when designing targeted interventions to meet the unique health needs of young people with different cultural norms and values.

In conclusion, this study provides evidence that ethnicity is not associated with HIV testing among adolescent girls and young women in Ghana. The bivariate association between ethnicity and HIV testing was attenuated when other cultural identity, behavioural and socioeconomic factors were controlled for. This suggests that beyond ethnicity, there are behavioural and socioeconomic factors that could explain differences in HIV testing across ethnic groups. The study particularly highlights the importance of considering individual-level factors, paying attention to marital status and sexual behaviours, in addition to the community-level factors that may influence the uptake of HIV testing when developing HIV prevention programmes for adolescent girls and young women in Ghana. Interventions and programmes aimed at increasing HIV testing among this group should take into consideration behavioural factors such as condom use, multiple sexual partnerships, as well as individual-level factors such as age and marital status, which are strongly associated with HIV testing. Interventions and policies should also take into consideration differences in the manifestation of these behavioural and individual determinants of HIV testing across ethnic groups. Future research could be conducted to delineate how these individual and behavioural determinants vary across ethnic groups.

Acknowledgments

The 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey data were available with permission from the DHS programme at dhsprogram.com/Data.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency, commercial entity, or not-for-profit organization.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors of this paper do not have any conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

The research was carried out by using a publicly available database. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees in human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1978, as revised in 2008.

Author Contributions

UN, TS and JI were involved in the conception, analysis and writing of the manuscript and approved it for publication. CO, FU, SM and JG critically reviewed the manuscript and approved it for publication.