Introduction

Maternal mortality is one of the key health challenges facing low- and middle-income countries. Globally, 810 women die from pregnancy-related complications each day. Around 99% of the world’s annual maternal mortality cases occur in low- and middle-income countries (WHO, 2010, 2014), with sub-Saharan African countries recording 62% of these (WHO, 2019). Maternal mortality rates in these countries need to be decreased in order to achieve target one of Sustainable Development Goal Three (SDG 3), which aims at reducing the global maternal mortality ratio to 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030 (United Nations, 2015).

Many maternal deaths are preventable, and the utilization of antenatal care (ANC) services contributes greatly to the prevention of such deaths (Okedo-Alex et al., Reference Okedo-Alex, Akamike, Ezeanosike and Uneke2019). The utilization of ANC services, as part of reproductive health care, provides an opportunity for health promotion, and the early diagnosis and treatment of illnesses during pregnancy (Okedo-Alex et al., Reference Okedo-Alex, Akamike, Ezeanosike and Uneke2019; Yaya & Ghose, Reference Yaya and Ghose2019). The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that every pregnant woman should have a minimum of 4 ANC visits throughout pregnancy, with the first visit occurring in the first trimester of pregnancy (WHO, 2002; UNICEF, 2020).

In November 2016, the WHO proposed new guidelines and recommendations on ANC and this included an increase in the recommended number of ANC visits from 4 to 8 or more contacts. To enhance quality, appropriate timing and maximum impact of care, the WHO also introduced an ANC model specifying that pregnant women should have their first ANC contact in the first 12 weeks of gestation, with subsequent contacts at 20, 26, 30, 34, 38 and 40 weeks of gestation. The model also emphasized the need to ensure a good attitude and comprehensive, person-centred care at each contact and the provision of timely and relevant information to pregnant women (WHO, 2016).

In Cameroon, 4500 pregnant women die every year from pregnancy-related complications. To reduce these deaths, close to one million pregnant women are expected to have at least 4 ANC visits every year (Bonono & Ongolo-Zogo, Reference Bonono and Ongolo-Zogo2012). However, only about 35% of pregnant women in Cameroon attended the critical first-quarter ANC visit in 2011, with 85% having at least one ANC visit and 60% having 4 or more ANC visits (INS et al., 2011).

Understanding the factors associated with the utilization of ANC services among pregnant women is needed to design strategies, policies and interventions to reduce maternal mortality. Previous studies on the utilization of ANC have mainly focused on sub-Saharan Africa (Okedo-Alex et al., Reference Okedo-Alex, Akamike, Ezeanosike and Uneke2019) and specific countries within the region such as Angola (Shibre et al., Reference Shibre, Zegeye, Idriss-Wheeler, Ahinkorah, Oladimeji and Yaya2020), Ethiopia (Yaya et al., Reference Yaya, Bishwajit, Ekholuenetale, Shah, Kadio and Udenigwe2017; Tiruaynet & Muchie, Reference Tiruaynet and Muchie2019) and Cameroon (Bonono & Onglo-Zogo, Reference Bonono and Ongolo-Zogo2012; Halle-Ekane et al., Reference Halle-Ekane, Obinchemti, Nzang, Mokube, Njie, Njamen and Nasah2014). The present study sought to assess how the new WHO guidelines, recommendations and models of focused ANC are working in Cameroon, by studying recent ANC utilization in Cameroon using data from a nationally representative survey executed after the implementation of the new WHO guidelines. This study aimed to examine the factors associated with the number and timing of ANC visits among married women in Cameroon. The study findings can be used to inform the design and implementation of strategic interventions and approaches to reducing maternal mortality in the country.

Methods

Data source

Data were from the 2018 Cameroon Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) (INS & ICF, 2020). This is one of the most recent datasets and was published after the implementation of the new WHO ANC service guidelines in November 2016. The DHS is a standardized cross-sectional survey undertaken in over 90 low- and middle-income countries, with the aim of providing current estimates on a number of health indicators and track countries’ progress on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The surveys employ a two-stage stratified sampling approach in sampling the research participants, grouped by urban and rural areas. The first stage involves the selection of clusters or enumeration areas (EAs) and the second stage consists of the selection of households for the survey. Details of the methodology employed in the study can be found in the final survey report (INS & ICF, 2020), available on the DHS programme website. This study considered a weighted sample of 1652 currently married women who gave birth within 0–12 months prior to the survey and had complete information on all the variables of interest as eligible respondents.

Study variables

The dependent variables were number of ANC visits, categorized as <8 visits or ≥8 visits, and time of first ANC visit, categorized as ≤3 months (early) or >3 months (late), as per the WHO recommendations (WHO, 2016). The explanatory variables were age of women at childbirth (≤19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, ≥40), place of residence (urban, rural), religion (Christian, Muslim, other), birth order (1–2, 3–4, ≥5), pregnancy intention (no, yes) and polygyny status (monogamous, polygamous as first wife, polygamous as second or higher wife). Other explanatory variables considered were health insurance coverage (no, yes), wealth quintile (poorest, poorer, middle, richer, richest), husband’s highest educational level (no education, primary, secondary, tertiary) and difference in age between husband and wife (wife older or same age as husband, husband 1–5 years older, husband 6–10 years older, husband more than 10 years older).

Data analyses

Three steps were followed for data analyses. The first involved the extraction, cleaning and recoding of variables. Data on respondents who had complete information and responses for all variables considered in the study were used in the analyses. As part of the first step, a multicollinearity test of the explanatory variables was conducted to investigate the presence of high collinearity between them, and no high collinearity was found. Secondly, frequencies and percentages were used to present the distribution of the explanatory variables. Next, a bivariate binary logistic regression analysis of the two outcome variables and each of the explanatory variables was conducted. In the final step, a multivariable binary logistic regression was used to examine the relationship between the outcome variables, while adjusting for all the explanatory variables and the results were presented as crude odds ratios (cOR) and adjusted odds ratios (aOR). All analyses were performed using Stata 14.0. Weighting, clustering and stratification were used to adjust for the complex survey design. Significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

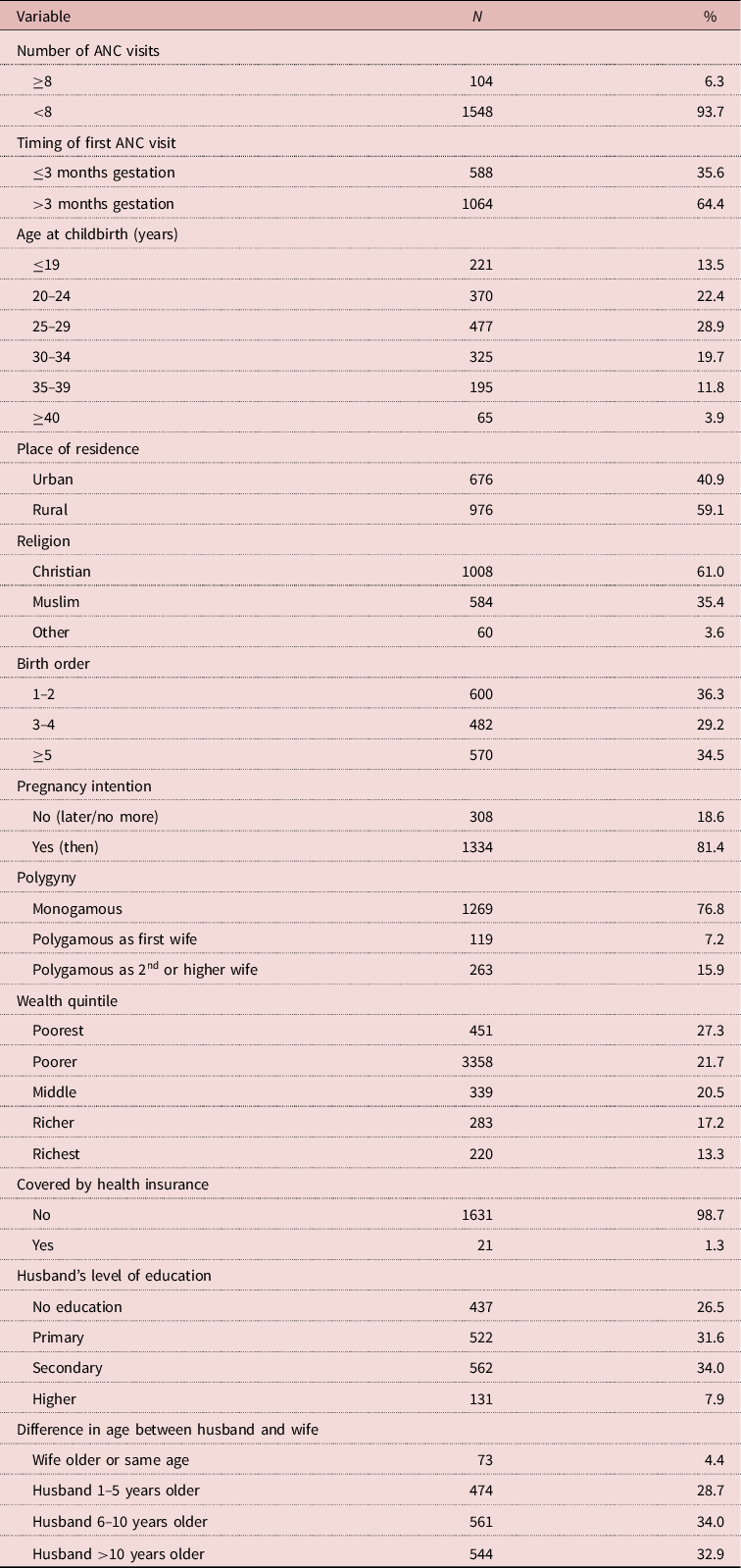

The proportions of women who had ≥8 ANC visits and first ANC visit at ≤3 months gestation were 6.3% and 35.6% respectively. Most women gave birth to their children at age 25–29 (28.9%), lived in rural areas (59.1%) and were Christians (61.0%). Most of the women had 1–2 birth order (36.3%), had planned pregnancies (81.4%) and were in monogamous marriages (76.8%). The majority of the women were in the poorest wealth quintile (27.3%), were not covered by health insurance (98.7%), had husbands with secondary education (34.0%) and husbands who were 6–10 years older than them (Table 1).

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of currently married women at most recent birth, Cameroon, 2018 (weighted), N=1652

Factors associated with number of ANC visits

The adjusted model showed that women aged 35–39 at childbirth were more likely to have had ≥8 ANC visits than those aged ≤19 (aOR=3.99, 95% CI=1.30–12.23). Also, women in the poorer (aOR=3.31, 95% CI=1.06–10.35) and middle (aOR=3.22, 95% CI=1.01–10.27) wealth quintiles were more likely to have had ≥8 ANC visits than those in poorest wealth quintile. The likelihood of ≥8 ANC visits was higher among women whose husbands had secondary (aOR=7.00, 95% CI=2.26–21.71) and higher (aOR=16.93, 95% CI=4.91–58.34) education than those whose husbands had no formal education (Table 2).

Table 2. Unadjusted and adjusted binary logistic regression on the association between women having ≥8 ANC visits and explanatory variables, Cameroon, 2018

***p<0.001; **p<0.05; *p<0.10.

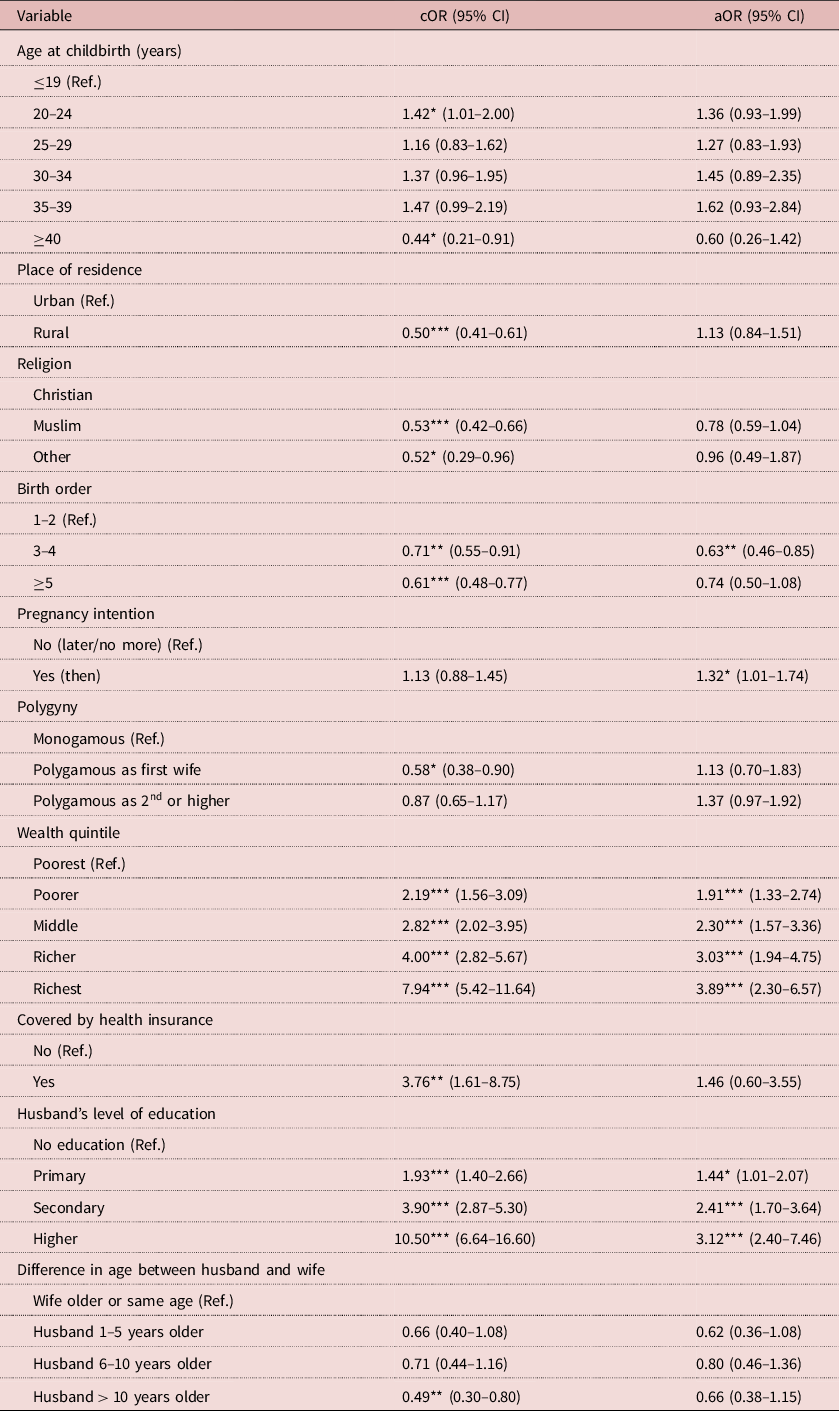

Factors associated with early timing of first ANC visit

Birth order showed a significant association with the early timing of first ANC. Women with 3–4 birth order (aOR=0.63, 95% CI=0.46–0.85) were less likely to have had early ANC visits than those with 1–2 birth order. The likelihood of having early ANC visits was higher among women whose pregnancies were intended (aOR=1.32, 95% CI=1.01–1.74), compared with those with unintended pregnancies. Moreover, compared with the poorest women, the poorer (aOR=1.91, 95% CI=1.33–2.74), middle (aOR=2.30, 95% CI=1.57–3.36), richer (aOR=3.03, 95% CI=1.94–4.75) and richest women (aOR=3.89, 95% CI=2.30–6.57) were more likely to have had early timing of first ANC visits. The odds of early timing of first ANC visits also increased with husband’s level of education, with women whose husbands had primary (aOR=1.44, 95% CI=1.01–2.07), secondary (aOR=2.41, 95% CI=1.70–3.64) and higher education (aOR=3.12, 95% CI=2.40–7.46) being more likely to have had early ANC visits than those whose husbands had no formal education (Table 3).

Table 3. Unadjusted and adjusted binary logistic regression of the association between women having early timing of first ANC visits (≤3 months gestation) and explanatory variables, Cameroon, 2018

***p<0.001;**p<0.05;*p<0.10.

Discussion

This study investigated the factors associated with the number and timing of ANC visits among married women in Cameroon using the most recent DHS dataset since the implementation of the new ANC WHO guidelines in 2016. The findings showed that age at childbirth, wealth quintile and husband’s educational level were significantly associated with the number of ANC visits among married women. On the other hand, birth order, pregnancy intention, wealth quintile and husband’s educational level were the only variables found to be associated with the early timing of first ANC visit.

With regard to wealth, the study found that women in the poorest wealth quintile were likely to make fewer ANC visits compared with those in the poorer and middle wealth quintiles. In addition, the richest women had the highest odds of initiating ANC early and the poorest women had the lowest odds. This suggests that women from poor families in Cameroon are more likely to initiate ANC visits late than those from rich families, and are likely to receive fewer ANC visits than their richer counterparts (fewer than the WHO recommended standard). These findings support those of previous studies in Cameroon (Tolefac et al., Reference Tolefac, Halle-Ekane, Agbor, Sama, Ngwasiri and Tebeu2017) and Ghana (Arthur, Reference Arthur2012). Simkhada et al. (Reference Simkhada, Teijlingen, Porter and Simkhada2008), in their systematic review of factors affecting the utilization of ANC in low- and middle-income countries, identified the cost of travel and services as the main barriers to accessing ANC in most low- and middle-income countries. Thus, late initiation of ANCs may result from poor women attempting to limit their total ANC attendances in a pregnancy in order to reduce the overall cost of ANC. In addition, late initiation and fewer ANC visits among poor women could be due to the time needed to access ANC services – time poorer women cannot afford to spend when they have family and household duties and to attend to, even if ANC services and transport are free (Finlayson & Downe, Reference Finlayson and Downe2013). This is supported by the finding that there was no significant relationship between having health insurance and early ANC initiation or number of ANC visits. Thus, empowering women socioeconomically could be one of the best ways of addressing the problem of non-attendance and late ANC initiation during pregnancy among married women in Cameroon.

The study revealed that women whose husbands had higher education were more likely to initiate ANC visits early and had a higher number of ANC visits than those whose husbands had no formal education. Similar findings have been reported in Bangladesh (Chanda et al., Reference Chanda, Ahammed, Howlader, Ashikuzzaman, Shovo and Hossain2020) and Nigeria (Adekanle & Isawumi, Reference Adekanle and Isawumi2008). Since education is associated with employment and higher socioeconomic status, husbands with higher educational attainment are likely to be wealthier and better able to support their wives financially for ANC than those with a lower level of education (Tarekegn et al., Reference Tarekegn, Lieberman and Giedraitis2014). Thus, in a patriarchal nation like Cameroon, where married women largely depend on their husband’s income (Sultana, 2018), early ANC initiation and number of ANC visits could depend on the financial capacity of their husbands. Moreover, husbands with higher educational attainment are more likely to have better understanding of the ANC concept, processes and benefits. Thus, they may be more supportive of their spouses, not only in initiating ANCs early but also complying with the WHO recommended number of visits, as husband’s involvement has been shown to be significantly associated with improved ANC attendance among married women (Tweheyo et al., Reference Tweheyo, Konde-Lule, Tumwesigye and Sekandi2010).

Older women were more likely to have 8 or more ANC visits compared with younger women. This confirms earlier findings conducted in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi (Pell et al., Reference Pell, Meñaca, Were, Afrah, Chatio, Manda-Taylor and Ouma2013) and in Rwanda (Manzi et al., Reference Manzi, Munyanez, Mujawase, Banamwana, Sayinzoga and Thomson2014; Nisingizwe et al., Reference Nisingizwe, Tuyisenge and Hategeka2020) – that younger women were less likely to have 8 or more ANC visits. A plausible explanation for this could be that older women might have more experience with motherhood and more likely to be informed about pregnancy.

Early initiation of ANC was low among women with higher birth order compared with those with lower birth order. Similarly, Pell et al. (Reference Pell, Meñaca, Were, Afrah, Chatio, Manda-Taylor and Ouma2013) reported that multiparous women with higher birth order in Malawi and Kenya initiated ANC late and usually towards the end of the second trimester, except when they had experienced complications with a previous pregnancy. The delay in ANC initiation among women with higher birth order could be attributed to previous negative experiences with ANC services. For instance, a previous study in Cameroon identified poor satisfaction as one of the major reasons preventing multiparous women from utilizing ANC (Edie et al., Reference Edie, Obinchemti, Tamufor, Njie, Njamen and Achidi2015). Moreover, women with higher birth order may perceive themselves as being capable of handling their pregnancy during the early stages and will not see the need to seek ANC, thus endangering their lives and that of their unborn babies (Aliyu & Dahiru, Reference Aliyu and Dahiru2017). Therefore, minimizing the negative experiences associated with ANC and properly educating all pregnant women on the dangers associated with delaying the initiation of ANC could improve the timing of ANC among married women as they attain higher birth order.

Consistent with the findings of a previous study conducted in Ghana (Manyeh et al., Reference Manyeh, Amu and Williams2020), married women whose pregnancies were intended were more likely to have early ANC visits compared with those with unintended pregnancies. A plausible reason for this is that intended pregnancies are more valued by pregnant women and their partners, making it more likely that they will initiate ANC early.

The study had its strengths and limitations. The major strength of the study is that it used nationally representative sample of currently married women who gave birth in the past year before data collection. The short time between pregnancy and data collection could have minimized the risk of recall bias. However, the cross-sectional nature of the study meant that only associations could be made and causality inference was not possible. The nature of the survey may have resulted in social desirability bias because some participants may have been tempted to provide socially desirable responses to questions on both the number and timing of ANC visits. Finally, the availability of, and distance to, health care facilities, which affect accessibility and health-seeking behaviour, were not assessed.

In conclusion, this study highlights that age at childbirth, wealth, husband’s educational attainment, birth order and pregnancy intention could influence the utilization of ANC services among married women in Cameroon. Hence, to improve attendance and early initiation of ANC, interventions should be targeted at empowering women financially and removing all financial barriers associated with accessing ANC, improving ANC education among women and encouraging male involvement in ANC education.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial entity or not-for-profit organization.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical Approval

This analysis was based on the Demographic and Health Survey data from Cameroon which are available in the public domain. The data can be downloaded from: https://dhsprogram.com/methodology/survey/survey-display-511.cfm. The study conducted a secondary analysis with no identifiable information on survey respondents. The DHS reports that ethical procedures were the responsibility of the institutions that commissioned, funded or managed the surveys. All DHS surveys are approved by ICF international as well as an Institutional Review Board (IRB) in respective countries to ensure that the protocols are in compliance with the US Department of Health and Human Services’ regulations for the protection of human subjects. In compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki on human research, both verbal and written consent for participation were duly obtained from respondents based on their level of education before data collection.