Introduction

Little is known about the risk and precipitating factors for abortion in developing countries, where community-based surveys on abortion are rare. Existing studies have generally considered a small set of potential household and individual socio-demographic determinants of abortion, and have treated abortion as an isolated outcome, ignoring its relationship with prior reproductive health behaviours and experiences (Nair & Kurup, Reference Nair and Kurup1985; Shapiro & Tambashe, Reference Shapiro and Tambashe1994; Ping & Smith, Reference Ping and Smith1995; Agadjanian & Qian, Reference Agadjanian and Qian1997; Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Rahman and van Ginneken1998; Babu et al., Reference Babu, Nidhi and Verma1998; Okonofua et al., Reference Okonofua, Odimegwu, Ajabor, Daru and Johnson1999; Ahiadeke, Reference Ahiadeke2001; Bairagi, Reference Bairagi2001; Calvès, Reference Calvès2002; Geelhoed et al., Reference Geelhoed, Nayembil, Asara, van Leeuwen and van Roosmalen2002; Guillaume & Desgrees du Lou, Reference Guillaume and Degres du Lou2002; Razzaque et al., Reference Razzaque, Ahmed, Alam and van Ginneken2002; Bose & Trent, Reference Bose and Trent2005; Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Nyblade, Parasuraman, MacQuarrie, Kashyap and Walia2003; DaVanzo et al., Reference DaVanzo, Rahman, Razzaque and Grammich2004a, Reference DaVanzo, Razzaque and Rahman2004b). Using data from a large cross-sectional survey of abortion knowledge, attitudes and practices in Rajasthan, India, this paper makes two new and important contributions to this literature. First, the relationship between contextual-level factors and abortion are examined, in addition to household- and individual-level factors. Second, the probability of pregnancy and the conditional probability of induced abortion are jointly modelled, thus better reflecting abortion as the result of sequential and interrelated behaviours and events.

Conceptual framework

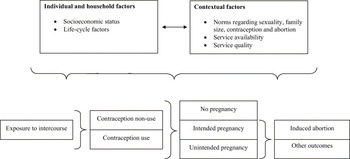

As there are no known conceptual frameworks for the determinants of induced abortion in developing countries, a developed country model was adapted, as shown in Fig. 1 (Rossier et al., Reference Rossier, Michelot and Bajos2007). Three aspects of this model are important for the current analysis. First, the probability of abortion is decomposed into a chain of interrelated and sequential events and behaviours, each with its own risk factors, which are analysed simultaneously. In doing so, these events and behaviours are assumed to be jointly determined with the decision to have an abortion, as supported by previous literature (Kane & Staiger, Reference Kane and Staiger1996; DaVanzo et al., Reference DaVanzo, Rahman, Razzaque and Grammich2004a). Second, the model assumes pregnancies reported as both intended and unintended may end in induced abortion; for example, originally intended pregnancies may be terminated following sex determination tests. Third, abortion and its antecedent events are determined by contextual, household and individual characteristics. Included under contextual factors are norms concerning sexuality, family size, contraception and induced abortion, as well access to, and quality of care of, abortion and family planning services. At the household and individual levels, the primary determinants are socioeconomic and life-cycle factors. The developing country community-based literature on the impact of each of these factors on induced abortion is summarized below.

Fig. 1. Conceptual framework for determinants of induced abortion and its antecedent event.

Determinants of abortion

Contextual-level effects. While there is significant research on the effect of contextual factors on induced abortion in developing countries, particularly the United States (Lundberg & Plotnick, Reference Lundberg and Plotnick1990; Currie et al., Reference Currie, Nixon and Cole1996; Joyce & Kaestner, Reference Joyce and Kaestner1996; Argys et al., Reference Argys, Averett and Rees2000; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Jewell and Rous2001), only two developing country studies have considered such factors (Ping & Smith, Reference Ping and Smith1995; Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, DaVanzo and Razzaque2001). The first study was conducted in China, and found a decreased likelihood of pregnancy termination in counties where enforcement of national family size policies was relaxed compared with those with strict enforcement, even after controlling for individual and household factors (Ping & Smith, Reference Ping and Smith1995). The second study, conducted in Matlab, Bangladesh, found significantly lower abortion rates in areas with better family planning services, although this was attributed to a decrease in unintended pregnancy rates, rather than to a difference in the propensity to abort unintended pregnancies (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, DaVanzo and Razzaque2001).

Household- and individual-level effects. Relative to contextual factors, the literature on effects of household and individual factors on induced abortion in developing countries is extensive. These studies have repeatedly highlighted socioeconomic factors as important determinants of induced abortion. Household standard of living, education, employment and caste have shown a consistently positive relationship with the likelihood of abortion (Nair & Kurup, Reference Nair and Kurup1985; Shapiro & Tambashe, Reference Shapiro and Tambashe1994; Agadjanian & Qian, Reference Agadjanian and Qian1997; Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Rahman and van Ginneken1998; Babu et al., Reference Babu, Nidhi and Verma1998; Okonofua et al., Reference Okonofua, Odimegwu, Ajabor, Daru and Johnson1999; Ahiadeke, Reference Ahiadeke2001; Calvès, Reference Calvès2002; Geelhoed et al., Reference Geelhoed, Nayembil, Asara, van Leeuwen and van Roosmalen2002; Guillaume & Desgrees du Lou, Reference Guillaume and Degres du Lou2002; Razzaque et al., Reference Razzaque, Ahmed, Alam and van Ginneken2002; Bose & Trent, Reference Bose and Trent2005; Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Nyblade, Parasuraman, MacQuarrie, Kashyap and Walia2003; DaVanzo et al., Reference DaVanzo, Rahman, Razzaque and Grammich2004a, Reference DaVanzo, Razzaque and Rahman2004b). Urban residence has shown a positive relationship with abortion in four of the six studies considering this measure of socioeconomic status and no relationship in the others, raising the question of whether urbanization is a proxy for improved socioeconomic status or other unmeasured factors, including differential access to services (Babu et al., Reference Babu, Nidhi and Verma1998; Okonofua et al., Reference Okonofua, Odimegwu, Ajabor, Daru and Johnson1999; Ahiadeke, Reference Ahiadeke2001; Geelhoed et al., Reference Geelhoed, Nayembil, Asara, van Leeuwen and van Roosmalen2002; Bose & Trent, Reference Bose and Trent2005; Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Nyblade, Parasuraman, MacQuarrie, Kashyap and Walia2003).

Life-cycle factors are also important individual-level predictors of abortion in developing countries. Most studies show an increase in the odds of abortion with increasing age, sometimes followed by a decrease in the late reproductive years, with exceptions in studies of adolescents or in settings where pre-marital intercourse is more common (Shapiro & Tambashe, Reference Shapiro and Tambashe1994; Alvarez et al., Reference Alvarez, Garcia, Catasus, Benitez, Martinez, Mundigo and Indriso1999; Ahiadeke, Reference Ahiadeke2001; Calvès, Reference Calvès2002; Guillaume & Degrees du Lou, Reference Guillaume and Degres du Lou2002; Razzaque et al., Reference Razzaque, Ahmed, Alam and van Ginneken2002; Bose & Trent, Reference Bose and Trent2005; DaVanzo et al., Reference DaVanzo, Rahman, Razzaque and Grammich2004a, Reference DaVanzo, Razzaque and Rahman2004b). Studies have also linked increased parity to pregnancy termination (Ping & Smith, Reference Ping and Smith1995; Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Rahman and van Ginneken1998; Ahiadeke, Reference Ahiadeke2001; Bairagi, Reference Bairagi2001; Calvès, Reference Calvès2002; Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Nyblade, Parasuraman, MacQuarrie, Kashyap and Walia2003; DaVanzo et al., Reference DaVanzo, Rahman, Razzaque and Grammich2004a), and in Asia, son preference (Ping & Smith, Reference Ping and Smith1995; Bairagi, Reference Bairagi2001; Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Nyblade, Parasuraman, MacQuarrie, Kashyap and Walia2003). Family spacing or limiting desires and short pregnancy intervals have also been associated with increased odds of abortion (Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Rahman and van Ginneken1998; Razzaque et al., Reference Razzaque, Ahmed, Alam and van Ginneken2002; Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Nyblade, Parasuraman, MacQuarrie, Kashyap and Walia2003; DaVanzo et al., Reference DaVanzo, Rahman, Razzaque and Grammich2004a, Reference DaVanzo, Razzaque and Rahman2004b).

The effect of women's autonomy on the propensity to terminate a pregnancy has received surprisingly little attention in the developing country literature. Two studies that included measures of women's autonomy, however, found it to be an important individual-level predictor of, and positively associated with, abortion (Akin, Reference Akin, Mundigo and Indriso1999; Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Nyblade, Parasuraman, MacQuarrie, Kashyap and Walia2003).

While the conceptual framework used in this paper posits that contraceptive use is jointly determined with sexual activity, pregnancy and abortion, most studies treat it as an exogenous variable. Cross-sectional studies have shown a consistently strong and positive association between current- and ever-use of contraception and induced abortion (Alvarez et al., Reference Alvarez, Garcia, Catasus, Benitez, Martinez, Mundigo and Indriso1999; Okonofua et al., Reference Okonofua, Odimegwu, Ajabor, Daru and Johnson1999; Razzaque et al., Reference Razzaque, Ahmed, Alam and van Ginneken2002; Bose & Trent, Reference Bose and Trent2005). Studies considering time-varying measures of contraceptive use suggest that this relationship reflects strong pre-pregnancy desires to control fertility among women undergoing abortions (Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Nyblade, Parasuraman, MacQuarrie, Kashyap and Walia2003; DaVanzo et al., Reference DaVanzo, Rahman, Razzaque and Grammich2004a).

Methods

Setting and data source

This study was conducted in the rural north-western Indian state of Rajasthan, one of India's least developed states. According to the latest National Family Health Survey (NFHS), only one-third of females aged ≤6 are literate. Marriage is nearly universal and occurs early. Fertility has declined little in the past decade, and the total fertility rate of 3.8 children per woman is roughly 30% higher than the national average (IIPS & ORC Macro, 2000). Son preference is believed to be pervasive, and to result in selective abortion of female fetuses and a skewed child sex ratio (Census of India, 2002).

In Rajasthan, like elsewhere in India, women have been entitled to legal abortion services during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy for medical and social reasons since the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act of 1971 was enacted (Government of India, 1971). Despite the existence of a seemingly liberal abortion policy, deficiencies in its implementation contribute to the continued predominance of illegal abortions in India. Access to approved facilities is poor, particularly in rural areas (Khan et al., Reference Khan, Barge, Kumar, Almroth and Pachauri1999). The quality of legal services is hindered by inadequately trained providers, pervasive infrastructure problems, poor treatment of clients and a lack of counselling (Johnston, Reference Johnston2002). Mis-perceptions regarding abortion legality are widespread among women, men and even providers (Sheriar, Reference Sheriar2001; Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Nyblade, Parasuraman, MacQuarrie, Kashyap and Walia2003; Elul et al., Reference Elul, Barge, Verma, Kumar, Bracken and Sadhvani2004). Ultimately, 60–90% of the annual 6 million abortions estimated in India are believed to be illegal, and unsafe abortions account for significant mortality and morbidity (Chhabra & Nuna, Reference Chhabra and Nuna1994; Sood et al., Reference Sood, Juneja and Goyal1995; Johnston, Reference Johnston2002; Duggal & Ramachandran, Reference Duggal and Ramachandran2004; Ganatra, Reference Ganatra, Jejeebhoy and Ramasubban2000a, Reference Ganatra, Puri and Look2000b; Johnston, Reference Johnston2002; Sedgh et al., Reference Sedgh, Henshaw, Singh, Ahman and Shah2007).

The data for this analysis come from a 2001 Population Council Abortion Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices survey conducted in six districts of Rajasthan (Elul et al., Reference Elul, Barge, Verma, Kumar, Bracken and Sadhvani2004). Multi-stage stratified cluster sampling was used to select a sample of 3682 ever-married women aged 15–44 in district headquarters, villages and towns lying within a 25 km radius of the district headquarters, as well as one pre-selected town per district and villages lying within a 5 km radius of those towns. Ultimately, 3266 (89%) of the 3682 eligible women identified were interviewed. This paper includes data from the 2571 (79%) currently married women at risk of pregnancy and abortion during the five years preceding the survey. Woman- and pregnancy-based data are combined such that women who had no or one pregnancy in the five-year reference period appear in the dataset once, while those with more than one pregnancy appear in the dataset multiple times, corresponding to the total number of pregnancies they reported in the reference period. The final sample consists of 3861 observations.

Analytical approach

Combining woman- and pregnancy-based data permits simultaneous modelling of two of the four principal antecedent events or behaviours depicted in Fig. 1: namely pregnancy and abortion. While the conceptual framework suggests that abortions may result from both unintended and intended pregnancies, due to the small number of abortions in the sample, these probabilities were not modelled separately. Instead, abortion was conditioned on all pregnancies, regardless of intentions.

A maximum likelihood bivariate probit model with selection was used to jointly identify the determinants of whether or not a woman has a pregnancy, and whether those pregnancies end in induced abortion or another outcome (i.e. live birth, spontaneous abortion or still-birth). Following the conceptual framework, this model allows explicit correlation between the two dependent variables, as well as for the censoring process, thus accounting for potentially significant endogeneity between them (Greene, Reference Greene2003). As the model fits two equations simultaneously, the parameters that govern the determination of whether a woman has a pregnancy can differ from those that govern whether the pregnancy ends in abortion, thus accommodating a key aspect of the conceptual framework. In other words:

(1) y 1j=(x 1j′β1+µ1j >0), for the pregnancy selection model;

(2) y 2j=(x 2j′β2+µ2j >0), for the abortion model;

where:

µ1j ∼ N(0, σ);

µ2j ∼ N(0, 1);

corr(µ1j, µ2j)=ρ;

and y 2j is only observed if, and only if, y 1j>0.

All analyses account for clustering at the primary sampling unit (PSU), household and respondent levels, and were performed using STATA 7.0.

At the individual level, five variables were included: time-varying measures of the respondent's age, number of living children and number of living sons, as well as religion, and the strength of the respondent's personal networks. To assess personal network respondents were first asked to list (but not name) up to five ever-married women aged 15–44 with whom they discuss important matters and share secrets; and if they listed at least one such network member, they were then asked whether each network member had attempted abortion in the five years preceding the survey. As studies have documented an association between fertility regulation and both social interaction generally and social interaction regarding family planning specifically (Entwisle et al., Reference Entwisle, Rindfuss, Guilkey, Chamratrithirong, Curran and Sawangdee1996; Montgomery & Casterline, Reference Montgomery and Casterline1996; Kohler, Reference Kohler1997; Kohler et al., Reference Kohler, Behrman and Watkins2001; Madhavan et al., Reference Madhaven, Adams and Simon2003; Feyisetan et al., Reference Feyisetan, Phillips and Binka2003), this variable was categorized to reflect both whether respondents had personal networks, and if so, whether those networks included women who purportedly had attempted abortion in the reference period. The presence of a personal network in itself was hypothesized to be positively associated with the likelihood of abortion, even if those network members had purportedly not attempted abortion, and a stronger relationship was expected if those networks included women with abortion experience.

At the household level, two variables were considered: standard of living and area of residence. The standard of living index was calculated following the NFHS approach, which considers eleven different aspects of household wealth (IIPS & ORC Macro, 2000). Area of residence was based on census definitions.

At the contextual level, five variables were constructed by aggregating individual responses to questions regarding individual education, modern temporary contraceptive use, knowledge of abortion legislation, and familiarity with sex-selective abortion to the PSU level. In some cases, measuring these variables at the community level bypassed potentially endogeneity that would occur if they were measured at the individual level. For example, if individual-level knowledge of abortion legality was positively associated with induced abortion, it would be difficult to discern whether women who are more knowledgeable about abortion legality have more abortions or whether women who have abortions are more likely to learn abortion is legal. As increased community education has been associated with lower fertility and increased use of contraception, net of individual-level factors (Kravdal, Reference Kravdal2002; Moursund & Kravdal, Reference Moursund and Kravdal2003), it was expected to be positively correlated with abortion. Since time-varying data on contraceptive use at the individual level were not available, community-level prevalence of spacing methods at the time of the survey was included among the independent variables. This measure provides an indication of community desires to control fertility, and also, as community-level contraceptive prevalence is arguably more stable over time than individual use, serves as a proxy for contraceptive use at the start of the reference period. Community-level knowledge of abortion legality and beliefs regarding whether husband's consent is required pre-abortion capture different perceptions of abortion access that may deter women in India from terminating pregnancies (Ganatra, Reference Ganatra, Jejeebhoy and Ramasubban2000a). Since widely publicized legislative proscriptions on sex determination tests are likely to lead to under-reporting of sex-selective abortions, community-level knowledge of sex-selective abortions by others serves as a proxy for the prevalence of such abortions in a given community.

Results

Table 1 describes the background characteristics of the 2571 women at risk of pregnancy (and hence abortion) during the five years preceding the survey, the 1809 who had at least one pregnancy during the reference period, and the 202 who reported at least one abortion in that period.

Table 1. Percentage distribution of respondents at risk of pregnancy, reporting at least one pregnancy, and reporting at least one abortion in the five years preceding the survey

a At start of reference period.

Table 2 provides the coefficients from the bivariate probit selection model for the entire sample. In Model 1, which shows the effects of household and individual variables on the risk of pregnancy and the conditional risk of abortion, life-cycle factors are significantly related to the probability of pregnancy and to the conditional probability of abortion, albeit the latter to a lesser degree. While the probability of pregnancy peaks for women aged 25–34, age is positively related to abortion. Increasing parity is negatively correlated with pregnancy and positively correlated with abortion conditional on pregnancy. While the number of living sons is also negatively associated with pregnancy, it has no significant relationship with the likelihood of a pregnancy being terminated. As expected, socioeconomic status is associated with both outcomes. Women of high socioeconomic status and urban women are less likely than their low and middle socioeconomic status and rural counterparts, respectively, to become pregnant; once pregnant, though, they are more likely to abort. Higher individual educational attainment, however, is associated with a decreased probability of pregnancy but not significantly associated with pregnancy termination. While personal networks have no effect on the likelihood of pregnancy, as hypothesized, women with personal networks are significantly more likely to terminate their pregnancies, particularly if their networks include women with abortion experience.

Table 2. Bivariate probit estimates of pregnancy and abortion in the five years preceding the survey for total sample

a At start of reference period or before the index pregnancy if the woman had ≥1 pregnancy.

In Model 2, community-level education and contraceptive use are added to the pregnancy equation and all five community-level variables are added to the abortion equation. No community effects emerge in the pregnancy model and only a single marginally significant effect is observed in the abortion model: pregnancies are more likely to be terminated as more women in the community know someone who has had a sex-selective abortion. Inclusion of the community-level variables, however, reduces the rural–urban differential in both models, so much so that residence is no longer significantly related to either outcome variable. Similarly, individual-level educational differences in the propensity to get pregnant disappear once the community-level variables are added.

Since rural India is characterized by poorer access to abortion and minimal familiarity with abortion legislation, the meaning of the contextual factors may vary by geographic area. Table 3 explores the effects of individual, household and contextual variables on induced abortion in urban versus rural areas. Using the same variables as in the final model for the total sample, some of the previously observed relationships for household and individual factors persist in both areas. Women aged 25–34 remain the most likely to become pregnant, and increasing age is still strongly positively associated with a pregnancy being terminated in both geographic areas. Religion continues to have no effect on either outcome. The effects of other variables, however, differ across the geographic sub-samples. For urban women, increased parity and number of living sons are both inversely related to pregnancy and not significantly associated with termination. Among rural women, increased parity negatively affects the propensity to get pregnant but positively affects the likelihood of abortion, while the number of living sons has no significant relationship with either outcome. Similarly, household standard of living shows a strong inverse relationship with pregnancy risk among urban women but not in the rural sample. Its effect on the likelihood of a pregnancy ending in abortion, however, is stronger among rural women. Additionally, the effect of personal networks on the likelihood of a pregnancy ending in abortion is evident only for rural women and is particularly strong when their networks include women with abortion experience.

Table 3. Bivariate probit estimates of pregnancy and abortion in the five years preceding the survey, by geographic area

a At start of reference period or before the index pregnancy if the woman had ≥1 pregnancy.

Note: All p values are from the z-test; ref.=reference group; estimates take into clustering by household and by woman.

The contextual variables remain largely non-significant in both the pregnancy and abortion models once the data are disaggregated by geographic area. The previously observed association between community knowledge of sex-selective abortion behaviours among others and pregnancy termination is not significant in either area. Among rural women, however, community-level beliefs regarding whether husband's consent is required to obtain an abortion emerges as the strongest predictor of a pregnancy being aborted: the greater the proportion of women in the community who incorrectly believe that husband's consent is required pre-abortion, the less likely rural women are to terminate their pregnancies.

Discussion

This paper examined contextual-, household- and individual-level determinants of induced abortion using data from a large community-based abortion knowledge, attitudes and practice survey. Using a model that accounts for endogeneity between abortion and pregnancy, the probability of abortion was decomposed into two sequential but interrelated behaviours and events. This approach provides a more methodologically rigorous analysis of the determinants of this important method of fertility control. Of particular significance is the finding that rural women who report sharing important and private matters with other ever-married women of reproductive age are more likely to terminate pregnancies, particularly if their networks include women who purportedly had abortions. While there are significant data demonstrating the impact of social interaction on contraceptive use in developing countries (Entwisle et al., Reference Entwisle, Rindfuss, Guilkey, Chamratrithirong, Curran and Sawangdee1996; Montgomery & Casterline, Reference Montgomery and Casterline1996; Kohler, Reference Kohler1997; Kohler et al., Reference Kohler, Behrman and Watkins2001; Madhavan et al., Reference Madhaven, Adams and Simon2003; Feyisetan et al., Reference Feyisetan, Phillips and Binka2003), this is the first study to document the effect of such interaction on abortion. More attention should be directed to studying the relationship between social interaction and the likelihood of abortion.

Other results reaffirm the role of individual-level socioeconomic status and life-cycle factors in predicting abortion behaviour. They also provide additional evidence of where in the conditional chain of events leading to abortion these factors exert their influence. In particular, women's age, parity and household standard of living were strongly associated with both pregnancy and abortion. The number of living sons impacted fertility solely by decreasing the likelihood of pregnancy, which is surprising given the skewed child sex rations in Rajasthan (Census of India, 2002). Several analyses of abortion determinants in India have documented a direct relationship between son preference and abortion (Bose & Trent, Reference Bose and Trent2005; Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Nyblade, Parasuraman, MacQuarrie, Kashyap and Walia2003), suggesting that women in the survey may have under-reported pregnancies of female fetuses. Additionally, while there was evidence of rural–urban differentials in the propensity to abort in the initial analysis, these differences disappeared after controlling for community-level factors, suggesting that geographic residence is a proxy for access to services rather than a direct measure of socioeconomic status.

In contrast to the literature on the importance of community effects on other healthoutcomes and behaviours (von Korff et al., Reference von Korff, Koepsell, Curry and Diehr1992; Diez-Roux, Reference Diez-Roux1998), particularly of reproductive nature (Entwisle et al., Reference Entwisle, Hermalin, Kamnuansilpa and Chamratrithirong1984, Reference Entwisle, Casterline and Sayed1989; Degraff et al., Reference Degraff, Bilsborrow and Guilkey1997; Mroz et al., Reference Mroz, Bollen, Speizer and Mancini1999; Katende et al., Reference Katende, Gupta and Bessinger2003; Kravdal, Reference Kravdal2002; Stephenson & Tsui, Reference Stephenson and Tsui2002; Koenig et al., Reference Koenig, Ahmed, Hossain and Mozumder2003; Moursund & Kravdal, Reference Moursund and Kravdal2003; Stephenson & Tsui, Reference Stephenson and Tsui2003; Koenig et al., Reference Koenig, Stephenson, Ahmed, Jejeebhoy and Campbell2006), this study found little support for community effects on either pregnancy or abortion. Only two community-level variables were significantly associated with either outcome: increased community knowledge of sex-selective behaviours among others was positively associated with abortion among pregnant women in the total sample, and increased community misperceptions regarding husband's consent pre-abortion was negatively associated with pregnancy termination in the rural sub-sample. In the latter case, however, the effect estimate was highly significant and was by far the largest observed, underscoring the importance of community-level beliefs regarding consent requirements in deterring women from terminating their pregnancies. This finding is particularly worrisome as access to abortion services is already poor in rural India.

As few community-level effects on abortion were found, abortion may be determined largely at the individual level in Rajasthan. Indeed, a previous analysis of the determinants of abortion in several north Indian states, including Rajasthan, concluded that abortion behaviour in those states largely reflected women's individual characteristics as compared with several southern Indian states (Bose & Trent, Reference Bose and Trent2005). Before supporting this conclusion, however, further efforts are needed to develop relevant community- and contextual-level variables. Direct measures of access to, and quality of, services have been shown to determine other reproductive health outcomes in developing countries (Entwisle et al., Reference Entwisle, Hermalin, Kamnuansilpa and Chamratrithirong1984, Reference Entwisle, Casterline and Sayed1989; Degraff et al., Reference Degraff, Bilsborrow and Guilkey1997; Mroz et al., Reference Mroz, Bollen, Speizer and Mancini1999; Katende et al., Reference Katende, Gupta and Bessinger2003; Stephenson & Tsui, Reference Stephenson and Tsui2002; Stephenson & Tsui, Reference Stephenson and Tsui2003; Tuoane et al., Reference Tuoane, Diamond and Madise2003) and should be included in future analyses of determinants of abortion. While abortion providers may be reluctant to share the requisite information in facility surveys, women can report on providers and facilities in community-based studies.

Several study limitations should be noted. First, despite efforts to elicit complete pregnancy histories, under-reporting of pregnancies and induced abortions, and mis-reporting of induced abortions as spontaneous abortions or still-births, may have occurred. Thus, it is possible that the observed positive association between socioeconomic status and abortion may reflect a greater willingness of women of higher socioeconomic status to report abortions, and not true differences in levels of abortion. Second, given the cross-sectional nature of the data, several issues of causal and temporal ordering could not be definitively sorted out, particularly among the individual-level variables that were modelled as fixed across time. Additionally, the data do not permit exploration of several key steps in the chain to abortion as depicted in the conceptual framework, most notably sexual activity and individual-level contraceptive use pre-pregnancy. Due to the small numbers of abortions in the data, probabilities of unintended pregnancies and intended pregnancies could not be modelled separately and had to condition abortion on all pregnancies. Finally, data were not available on several potentially important determinants of abortion, including fertility desires, son preferences, duration of pregnancy intervals and women's autonomy.