Introduction

Nearly 42% of ever-married women in Malawi have experienced some form of physical, sexual or emotional violence perpetrated by their current or most recent spouse (NSO Malawi & DHS Program, 2017). The estimate of domestic violence in Malawi is much higher than the global estimate of 35% (WHO, 2017). Some customs and cultural practices in Malawi could contribute to the normalization of intimate partner violence. For example, religious institutions in Malawi do not recognize marital rape and it is understood that when a woman signs the marriage contract, she gives consent to sex throughout her married life (Kanyongolo & Malunga, Reference Kanyongolo and Malunga2011). A recent study indicates concordance between men and women in Malawi in their perception that women do not have the right to refuse sex from husbands (Kaminaga, Reference Kaminaga2017). A good percentage of women in Malawi think a husband is justified in beating his wife for at least one of the following reasons: if the wife burns food, argues with husband, goes out without telling him, neglects the children or refuses sex (NSO Malawi & ICF International, 2016). Nevertheless, there are regional variations in the reported justifications. The latest national-level study indicates that the highest percentage is in the Northern region (24.9%) followed by the Central region (16.7%) and the lowest is in the Southern region of the country (13.9%). Although the rank and order are not replicated in the regional variation for the level of spousal violence, the Southern region reported the lowest level of violence at 37% and the level of spousal violence was highest in the Northern and Central regions (47%), vindicating the work of earlier studies that acceptance of intimate partner violence is both a barrier to its reduction and a strong predictor of its prevalence (Alio et al., Reference Alio, Clayton, Garba, Mbah, Daley and Salihu2011; NSO Malawi & ICF International, 2016).

Although patriarchy and dependency theories suggest that economic and social processes that support the patriarchal order contribute to women's inferiority and increase their potential for suffering from domestic violence, a study in eight African countries, including Malawi, has suggested that cultural factors/customs such as having multiple partners may be more important to domestic violence than socioeconomic status (Dobash & Dobash, Reference Dobash and Dobash1979; Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Ho-Foster, Mitchell, Scheepers and Goldstein2007; Alio et al., Reference Alio, Clayton, Garba, Mbah, Daley and Salihu2011; Hyde-Nolan & Juliao, Reference Hyde-Nolan, Juliao, Fife and Shrager2011). Culture can be defined as the general customs and beliefs of a particular group of people at a particular time. It is the characteristics and knowledge of a particular group of people, encompassing language, religion, cuisine, social habits, music and arts (Hanson, Reference Hanson2013). In Malawi, the importance of culture is enshrined in the Malawi Constitution, section 26, which recognizes that every person shall have the right to use the language, and to participate in the cultural life, of his or her choice (UNFPA, 2012). The strength of culture in supporting and legitimizing gender inequality is a subject of debate in contemporary times. Feminists argue that culture is highly gendered and embeds structural inequalities throughout society (Anderson, Reference Anderson1997; Renzetti et al., Reference Renzetti, Edleson and Bergen2001). Malawi is no exception, and socio-cultural factors such as polygyny, dowry and male-headed households have been linked to domestic violence (Bisika, Reference Bisika2008). In addition, it has been argued that religion, just like culture, is a powerful institution within a society that plays a major role in shaping gender roles and social rules and behaviours (Inglehart & Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2003).

Most women in Malawi accept domestic violence as a family affair and are unlikely to report it (Pelser et al., Reference Pelser, Gondwe, Mayamba, Mhango, Phiri and Burton2005). A study on attitudes towards wife beating in Benin, Ethiopia, Malawi, Mali, Rwanda, Uganda and Zimbabwe revealed that more women than men perceive wife beating as justified (Rani et al., Reference Rani, Bonu and Diop-Sidibe2004).

One custom that emanates from poor socioeconomic status that is commonly practised in Malawi is early/child marriage. Early marriage is marriage that occurs when one or both partners are less than 18 years of age (UNFPA, 2012). At 47%, Malawi's level of girl child marriage is ranked 11th globally (GoM-AFIDEP, 2017; NSO Malawi & ICF International, 2017). In contrast, only 8% of boys marry before the age of 18 in Malawi, which indicates that most girls are marrying men who are much older than themselves (NSO Malawi & ICF International, 2017). A study across 30 countries found that the average age of first abuse for women is 22.1 years, suggesting that women are more likely to encounter their first abuse when they are young adults (Peterman et al., Reference Peterman, Bleck and Palermo2015). But the association between spousal age difference and violence against women may differ across populations, showing a protective effect against domestic violence in Nigeria but elevating the risk of women suffering intimate partner homicide in the United States (Breitman & Schackelford, Reference Breitman and Schackelford2004; Adebowale, Reference Adebowale2018). In Malawi, most early marriages are forced marriages due to the practice of wife inheritance, or parents using that as an opportunity for improving their poor socioeconomic conditions, and such practices are common in communities that practise polygynous marriage (MHRC, 2006). Early marriage has been linked to domestic physical violence in India (Pallikadavath & Bradley, Reference Pallikadavath and Bradley2018).

Although polygyny is a common cultural practice across all ethnic groups in Malawi, it is predominant in the Northern region amongst patrilineal communities (Berge et al., Reference Berge, Kambewa, Munthali and Wiig2013; Chikhungu et al., Reference Chikhungu, Madise and Padmadas2014). In polygynous marriages, first wives receive less support and attention from their husbands once their husbands acquire a new wife (MHRC, 2006). The patrilineal communities in the Northern region also practise bride price (lobola), which is a cultural practice where the groom's family makes a payment to the bride's family in kind, cash or material goods upon marriage to make the union ‘legitimate’ (Oguli, Reference Oguli2004). Gray (Reference Gray1960) asserted that bride price payment reduces women to the status of a property owned by the husband such that they are unable to defend and control their own bodies. Most communities in the Central and Southern regions are matrilineal. A common characteristic of matrilineal societies is higher autonomy amongst women, which leads to higher divorce rates than among their counterparts in the patrilineal societies (Arnado, Reference Arnado2004; Takyi & Gyimah, Reference Takyi and Gyimah2007). Unsurprisingly, the Southern region of Malawi has a relatively larger percentage of female-headed households (28%) compared with the Central region (21.2%) and Northern region (19.9%) (NSO Malawi, 2012).

Although not a cultural factor per se, heavy alcohol consumption has been commonly linked to domestic violence across the globe but the impact of alcohol consumption on behaviour varies across societies (SIRC, 1998; Brecklin & Ullman, Reference Brecklin and Ullman2002; Gilchrist et al., Reference Gilchrist, Johnson, Takriti, Westo, Beech and Kebbell2003; McKinney et al., Reference McKinney, Caetano, Harris and Ebama2009). Evidence based on cross-cultural research and controlled experiments indicates that the effects of alcohol on behaviour are largely determined by social and cultural factors rather than the effect of the ethanol itself. Societies hold different expectations about the effects of alcohol and social norms regarding the drunken state (SIRC, 1998). It has been established that alcohol is only an enabler of certain culturally given drunken states, with some societies across the world displaying little aggression after consuming alcohol and others showing aggression only in specific drinking contexts or against selected categories of drinking companions (Heath, Reference Heath and Gotthiel1983; Marshall, Reference Marshall1981). In Malawi a modest percentage (14.5%) drink alcohol but significantly more men (27.3%) than women (1.6%) do so (ADD, 2013).

Previous studies on the linkages between gender-based violence or violence against women and culture in Malawi have been limited to a few selected districts with analysis being largely descriptive (MHRC, 2006; Bisika, Reference Bisika2008). No study has investigated the cultural factors associated with various types of violence against married women across the whole population in Malawi. In this study, the latest national data from Malawi were used to explore the association between cultural factors and the likelihood of married women experiencing sexual, physical and emotional violence after controlling for socioeconomic factors.

Methods

Data

Data for women aged 15–49 years were taken from the Malawi Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) of 2015. The women's questionnaire collected information from 24,562 of the 25,146 women aged 15–49 years who were eligible for interview, representing a 98% response rate. One-third of the sampled households were asked questions on domestic violence (6379 households). Specifically, constructed weights were used to adjust for selection of only one woman per household to ensure national representativeness. The domestic violence module collected data on different types of violence: physical, sexual and emotional. The survey also provided information on background characteristics, including household wealth status and demographic characteristics of all household members such as age, sex and relationship to household head. Further details of study design and data collection are reported on the National Statistical Office of Malawi website (http://www.nsomalawi.mw/).

Dependent variables

Four types of domestic violence – sexual, less-severe physical, severe physical and emotional – were analysed. The dependent variable was binary: a woman who experienced any of the four types of domestic violence took the value 1 and 0 otherwise.

The four types of domestic violence were defined as follows. A women was reported to have suffered sexual violence if she was ever forced by her partner or husband to have sexual intercourse when she did not want to or been forced to perform a sexual act that she did not want. A woman suffered emotional violence if she had ever been insulted or made to feel bad about herself by her husband or partner, been humiliated in front of others, had been threatened or hurt, or if someone that the respondent cared about was harmed. Less-severe physical violence was reported if a woman was physically harmed by their partner or husband by being pushed, shaken, slapped or punched with a fist or hit by something harmful, ever had her arm twisted or hair pulled or had something thrown at them. Severe physical violence was reported if a woman had ever been kicked, dragged, strangled, burnt or threatened with knife/gun or other weapon by her husband or partner.

Independent variables

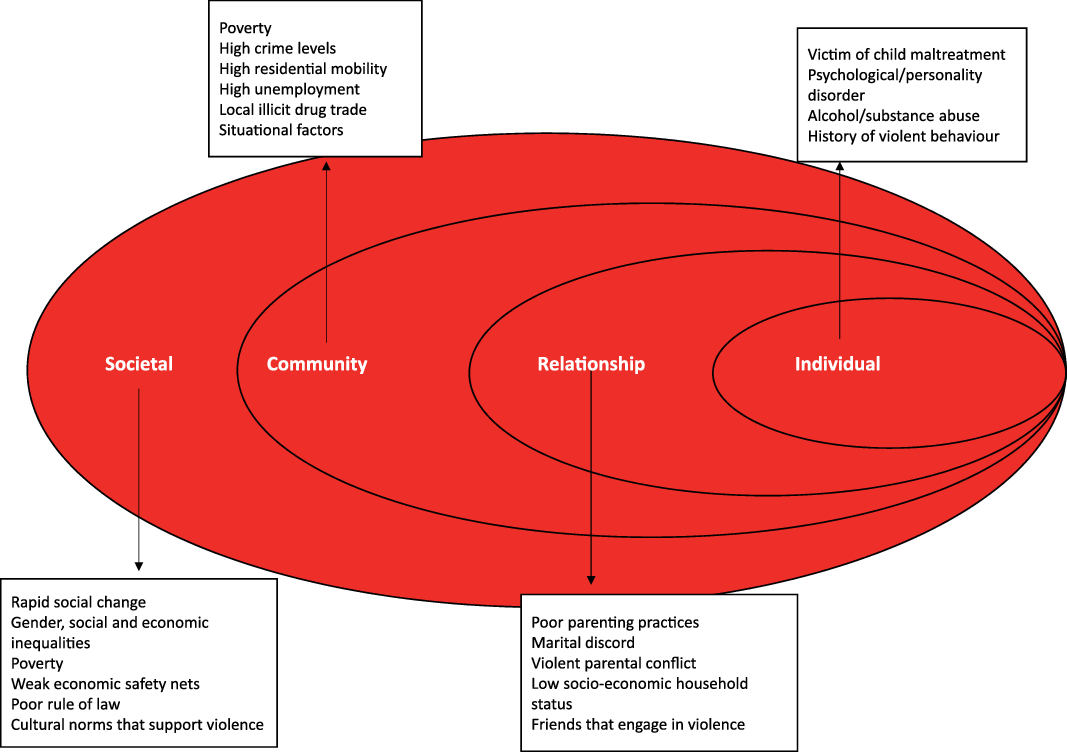

The study of associates of domestic violence are best conceptualized through the ecological model of violence (Carson, Reference Carson1984) commonly used by the WHO Violence Prevention Alliance shown in Fig. 1 (WHO, 2018). Of key relevance to this study is the societal level, which recognizes factors such as gender, social and economic inequalities, poverty and cultural norms.

Figure 1. The ecological framework: examples of risk factors for intimate partner violence at each level. Source: WHO (2018). The Violence Prevention Alliance (VPA) approach (http://www.who.int/violenceprevention/approach/ecology/en/).

The choice of cultural and socioeconomic variables was guided by the ecological framework of violence (Fig. 1), and previous literature on the factors associated with domestic violence discussed in the Introduction and data available in the 2015 Malawi DHS. The initial bivariate analysis explored if there was an association between any form of domestic violence and the following respondent characteristics: current age, age at cohabitation, level of education, place of residence, region of residence, religion, ethnicity, spousal age difference, husband's alcohol consumption, age at first sex, current occupation and type of marriage (including respondent's rank among other wives for polygynous marriages). Table 1 presents the independent variables included in the final models.

Table 1. Distribution of background characteristics of study women, Malawi, 2015

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using STATA Version 14.0. Sampling weights were used to account for the unequal probability of selecting a survey respondent. To describe the proportional distribution of the survey respondents, cross-tabulations were performed and Chi-squared test of association was performed to examine the association between the domestic violence variables and the cultural, demographic, geographic, socioeconomic variables and husband characteristics. Chi-squared tests of association were performed instead of correlation tests or other measures of associations because the data were categorical (Rea & Parker, Reference Rea and Parker2014).

The final analysis used multilevel logistic regression modelling to estimate the odds ratios (OR) of a woman experiencing domestic violence for women of particular cultural traits after taking into account background characteristics that were statistically significant in the Chi-squared test of association. Multivariate analyses are able to identify characteristics associated with experiencing domestic violence net of other factors, whereas multilevel modelling ensures that estimates are robust in hierarchical data such as those use in this study and where the factors being studied vary significantly at a higher level, e.g. community. In the models where significant variation of domestic violence exists at the community level, the fixed effects estimates are representative of the community level and not at the population level. A p-value of less than 0.05 was used to decide which variables were statistically significant in both the bivariate and multivariate analysies.

Modelling framework

The following logit link is a function that models the probability that a woman i in community j experienced either sexual, emotional, less-severe physical or severe physical domestic violence.

$$lo{g_e}\left( {\frac{{{\pi _{ij}}}}\over{{1 - {\pi _{ij}}}}} \right)$$

$$lo{g_e}\left( {\frac{{{\pi _{ij}}}}\over{{1 - {\pi _{ij}}}}} \right)$$

A two-level random intercept model was fitted, with the woman as the first level and the community as the second level. The two-level random intercept model for woman i nested within a community j may be represented as follows;

$$lo{g_e}\,\left( {\frac{{{\pi _{ij}}}}\over{{1 - {\pi _{ij}}}}} \right)\, = \,{\beta _0}\, + \,{\beta _1}{x_{1ij}}\, + \, + \,{\beta _2}{x_{2ij}} + ... + \,{\beta _6}{x_{6ij}}\, + \,{u_{0j}}$$

$$lo{g_e}\,\left( {\frac{{{\pi _{ij}}}}\over{{1 - {\pi _{ij}}}}} \right)\, = \,{\beta _0}\, + \,{\beta _1}{x_{1ij}}\, + \, + \,{\beta _2}{x_{2ij}} + ... + \,{\beta _6}{x_{6ij}}\, + \,{u_{0j}}$$

where x 1 to x 6 represent a mixture of cultural, demographic, geographic, socioeconomic and husband/partner characteristics that are explanatory variables for the probability that woman i in community j experiences some form of domestic violence. The term β 0 is the overall intercept and β 1 to β 6 are coefficients for the explanatory variables x 1 to x 6. The term U 0j is the community-level random effect, which represents the variation of the likelihood of experiencing violence for women from different communities and is assumed to be normally distributed with a mean equal to 0 and variance equal to σ µ0 2.

Results

Results of the bivariate analysis

A Chi-squared test was undertaken to test the association between the four types of domestic violence and background factors to identify which variables should be included in the multilevel logistic regression analysis. Ethnicity, religion, marriage type, education level, occupation and husband's intake of alcohol were found to be significantly associated with all four types of violence, and the following variables were found to be associated with either one, two or three of the four types of domestic violence: matrilineal/patrilineal lineage, age at first cohabitation, age at first sex, urban/rural residence, husband's occupation and husband's education level.

The study also explored the variation in approval of wife beating across cultural and geographical factors because acceptance of domestic violence may perpetuate its existence and in some cases reduce the likelihood of it being reported (Alio et al., Reference Alio, Clayton, Garba, Mbah, Daley and Salihu2011; Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Ho-Foster, Mitchell, Scheepers and Goldstein2007; Biswas et al., Reference Biswas, Rahman, Kabir and Raihan2017). Table 2 presents the results of a Chi-squared test of association between cultural and geographical factors and the percentage of women who think wife beating is justified for any reason. The percentage of women that thought wife beating was justified was higher among women who married between the ages of 14 and 17 years than among those who married at less than 13 years or over 18 years of age. It was higher amongst women from rural areas than in those from urban areas, higher in the Northern region than the Central and Southern regions, higher amongst Christian women than Muslim women, highest amongst the Tumbuka, Nkhonde and Tonga ethnic grouping, second highest amongst those classed as ‘Other’ ethnicity and lowest amongst the Ngoni and higher amongst women in polygynous marriages than among women in monogamous marriages.

Table 2. Association between women's perceptions on wife beating and cultural and geographical factors

a ‘Other’ comprised of various ethnic groupings that are foreign.

Results of the multilevel logistic regression analysis

The results of the multilevel logistic regression analysis are presented in Tables 3 and 4. Table 3 shows the results of the random part of the model and Table 4 provides the results of the fixed part of the model. All models showed significant community-level variance. In the fixed part of the model, three variables (urban/rural residence, lineage and husband's occupation) were not significant in the multivariate analysis despite showing a statistically significant association in the bivariate analysis.

Table 3. Results of the random part of the model

Table 4. Results of the fixed part of the multilevel logistic regression analysis

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Cultural and geographical factors

The results of the fixed part of the model indicated that type of marriage (polygynous or not) was an important factor explaining the likelihood of a woman experiencing any form of domestic violence. The odds of experiencing violence were higher for first wives than for wives in monogamous marriages: 49% higher for emotional violence, 61% higher for less-severe violence and 82% higher for severe physical violence. In the emotional violence model there was a significant difference in the odds of experiencing violence between women who were in monogamous marriages and those who were second wives in polygynous marriages. The odds of experiencing emotional violence were 34% higher in second or higher order wives than in wives in monogamous marriages. There was a statistically significant interaction between wife's rank and age at cohabitation in the sexual violence model. Compared with women in monogamous marriages aged 13 or less, the odds of experiencing sexual violence were nearly three times greater for first wives aged 18 years above.

The ethnicity variable was only significant for the less-severe physical violence and severe physical violence variables. The odds of experiencing less-severe physical were 28% higher amongst the Lomwe and 45% higher amongst the Sena than among the Chewa. Religion also turned out to be significantly associated with experiencing domestic violence. The odds of experiencing any form of domestic violence were lower for Muslim women compared with Christian women: 33% lower for sexual violence, 34% lower for emotional violence, 39% lower for less-severe physical violence and 41% lower for severe physical violence. The region variable was significantly associated with sexual and emotional violence only. The odds of experiencing sexual violence were 64% higher amongst women from the Central region than women from the Northern region, and the odds of experiencing emotional violence were 57% higher among women from the Central region than in women from the Northern region.

Husband's characteristics

Of the three husband characteristics (husband's education level, husband's occupation and husband's alcohol intake) it was only husband's alcohol intake that was significantly associated with women's experience of domestic violence. Compared with women whose husbands did not drink alcohol, women whose husbands often drank alcohol had higher odds of experiencing sexual violence (4 times), emotional violence (6 times), less-severe physical violence (7 times) and severe physical violence (9 times). The odds of experiencing any form of violence were about twice as high for women whose husbands sometimes drank alcohol compared with women whose husbands did not drink any alcohol.

Socioeconomic and demographic variables

Woman's employment status, woman's education status, age at first cohabitation, age at first sex and woman's current age, which were all included as control variables, were found to be significantly associated with at least one type of violence.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore cultural factors associated with sexual, emotional and physical (both less-severe and severe) violence against married women in Malawi. The findings indicate that marriage type (monogamous or polygynous), age at marriage, ethnicity and religion are important cultural factors that determine the likelihood of a married woman experiencing any form of domestic violence in Malawi. Husband's/partner's alcohol intake also emerged an important determinant of domestic violence encountered by married women in Malawi and its influence may vary across cultural settings.

In all four types of domestic violence, the odds of Muslim women experiencing domestic violence were less than those of Christian women. This finding is interesting and may either indicate that Islamic teachings of wife's obedience to her husband ensures that the likelihood of Muslim women being at loggerheads with their husbands are minimal, or that such teachings increase the acceptability of domestic violence amongst Muslim women such that they are less likely to report (Why Islam, 2015; Biswas et al., Reference Biswas, Rahman, Kabir and Raihan2017; Eidhamar, Reference Eidhamar2018). In Malawi, Muslim women have higher odds of experiencing controlling behaviour than Christian women, which aligns with Islamic teachings (Chikhungu et al., Reference Chikhungu, Amos, Kandala and Palikadavath2019), but the finding from this study that the percentage of women that approve of wife beating for any reason is higher amongst Christian women than Muslim women suggests that the low levels of violence among Muslim women may not be as a result of acceptance of violence and low reporting level, but that violence is actually lower amongst Muslim women.

The finding that women in polygynous marriages have higher odds of experiencing violence than women in monogamous marriages is consistent with the findings from previous studies in Malawi and other settings (Bisika, Reference Bisika2008; Jansen & Agadjarian, Reference Jansen and Agadjarian2016). Women in polygynous marriages tend to have limited access to land, inheritance and sources of formalized power and are therefore less likely to have an equal relationship with their partners compared with women in monogamous unions (Goody, Reference Goody1973; White & Burton, Reference White and Burton1988; McCloskey et al., Reference McCloskey, Williams and Larsen2005). The biggest difference in the odds of experiencing violence between women in polygynous and monogamous marriages was in the likelihood of experiencing severe physical violence compared with less-severe physical violence and emotional violence. The study also found that there was no significant difference in the odds of experiencing less-severe and severe physical violence between women in monogamous marriages and women who were second wives in polygynous marriages, similar to findings from Mozambique (Jansen & Agadjarian, Reference Jansen and Agadjarian2016).

Interestingly, the influence of age at marriage/cohabitation on domestic violence depended on the type of marriage (monogamous or polygynous). Women who married at 14 years of age or more were more likely to encounter sexual violence if they were first wives in a polygynous marriage than were women who married at 13 years or less and were in a monogamous marriage, which is not consistent with the expectation that younger women may be more vulnerable and more likely to be abused, but cements the important influence of marriage type over and above age at cohabitation/marriage of the woman. Marrying at 18 years of age or more has been found to be protective for physical domestic violence in India (Pallikadavath & Bradley, Reference Pallikadavath and Bradley2018).

The ethnicity variable was a significant factor in the less-severe and severe physical violence models only. The Lomwe and the Sena had higher odds of experiencing these two forms violence compared with the Chewa, Mang’anja and Nyanja. Interestingly the Tumbuka, Nkhonde and Tonga ethnic groups, the majority of whom practise bride price (lobola), did not have higher odds of experiencing violence compared with the Chewa, Mang’anja and Nyanja, who do not practise bride price (Gray, Reference Gray1960). The Lomwe follow a matrilineal lineage system but the Sena are patrilineal (Chikhungu et al., Reference Chikhungu, Madise and Padmadas2014). This finding suggests that there are potentially other factors within these ethnic groupings that may explain why they have relatively higher levels of violence compared with the Chewa, Mang’anja and Nyanja.

By the greatest margin, the factor that explained the likelihood of women experiencing any form of domestic violence was whether or not their partner/husband drank alcohol. The difference in the odds of experiencing violence was highest between women whose husbands drank alcohol often and those whose husbands did not drink alcohol; and highest in the severe physical violence model, followed by the less-severe physical violence, then emotional violence and sexual violence models. The difference in odds of experiencing violence between women whose husbands drank alcohol occasionally and those than never drank alcohol was significant but small. The role of alcohol in domestic violence has been reported in numerous previous studies (Brecklin & Ullman, Reference Brecklin and Ullman2002; Gilchrist et al., Reference Gilchrist, Johnson, Takriti, Westo, Beech and Kebbell2003; Room et al., Reference Room, Babor and Rehm2005; McKinney et al., Reference McKinney, Caetano, Harris and Ebama2009; Bernardin et al., Reference Bernardin, Maheut-Bosser and Paille2014; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kim and Park2016) but socioeconomic status may mediate the relationship between alcohol use and intimate partner violence and different societies may have different expectations about the effects of alcohol and social norms when people are drunk, such that behaviour in a drunken state may vary across societies (SIRC, 1998; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Kane and Tol2017). A small percentage of men drink alcohol in Malawi (ADD, 2013). This study was based on cross-sectional data so the relationship between the cultural factors and violence against women should be strictly interpreted as an association, and it was not possible to conclude that cultural factors that emerged statistically significant in the modelling caused violence against women.

In conclusion, apart from socioeconomic factors such as woman's education level and occupation and husband's alcohol consumption, cultural factors are important determinants of the likelihood of women experiencing domestic violence in Malawi. Key cultural factors are type of marriage (polygynous or monogamous), age at marriage, religion and ethnicity. Age at marriage/cohabitation interacts with type of marriage such that those who marry monogamously at a relatively younger age are less likely to encounter sexual violence than older first wives in polygynous marriages. Perceptions that wife beating is justified for various reasons may not explain why some groups are more likely to experience violence than others; a higher percentage of Christian women perceive that it is justified for a man to beat his wife than do Muslim women, but Muslim women are less likely to encounter any of the four types of violence. Interventions to tackle violence against married women should aim at promoting monogamous marriages and discouraging polygynous marriages, and also the culture of heavy alcohol consumption amongst husbands. Future studies could explore further if there are key lessons that families can learn from Muslim families and across ethnic groups.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial entity or not-for-profit organization.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Ethical Approval

The study used publicly available anonymized data such that there was no need to seek ethical approval. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.