Introduction

Adolescence is a period of life characterized by physical changes moving the individual from childhood into adulthood. Adolescence begins with puberty, a period of rapid physical maturation involving bodily changes due to significant height and weight gain (pubertal growth spurt), acquisition of muscle mass, the distribution of body fat resulting in the typical gynoid patterns of fat distribution, and the development of secondary sexual characteristics (Tanner, Reference Tanner1962; Bogin, Reference Bogin2005). Pubertal increased body weight and other physical changes often necessitate a confrontation and reorganization of self-perception (O’Dea & Abraham, Reference O’Dea and Abraham1999; Siegel et al., Reference Siegel, Yancey, Aneshensel and Schuler1999; Mäkinen et al., Reference Mäkinen, Puukko-Viertomies, Lindberg, Siimes and Aalberg2012). In particular, adolescent girls who find pubertal adjustment especially challenging are more likely than boys to evaluate negatively their physical appearance and show a higher level of body and weight dissatisfaction (Barker & Galambos, Reference Barker and Galambos2003; Presnell et al., Reference Presnell, Bearman and Stice2004; Ojala et al., Reference Ojala, Vereecken, Välimaa, Currie, Villberg, Tynjälä and Kannas2007). This dissatisfaction seems to be a significant risk factor for body distortions, depression, low self-esteem and eating disorders (Stice et al., Reference Stice, Hayward, Cameron, Killen and Taylor2000; Holsen et al., Reference Holsen, Kraft and Roysamb2001; Stice & Bearman, Reference Stice and Bearman2001; Stice & Whitenton, Reference Stice and Whitenton2002; Paxton et al., Reference Paxton, Eisenberg and Neumark-Sztainer2006a; Hrabotsky et al., Reference Hrabosky, Cash, Veale, Neziroglu, Soll and Garner2009). Girls are more likely than boys to be depressed, and this differentiation begins at around age 14 (Cash and Pruzinsky, Reference Cash and Pruzinsky1990). Also, aberrance in maturational timing (advanced or delayed pubertal development) is commonly agreed to increase the risk of body dissatisfaction (McCabe & Ricciardelli, Reference McCabe and Ricciardelli2004). Girls who mature earlier than their peers are less satisfied with their own bodies and more concerned about physical appearance (Williams & Currie, Reference Williams and Currie2000). Even though sex and age are two widely studied factors in adolescents’ perceptions of their own bodies, other biological, behavioural and socio-cultural variables, such as the stage of pubertal development, weight status, teasing from peers, relations with friends, parents, siblings and teachers, acquaintances and the media could also influence self-perception of one’s body (Stice & Whitenton, Reference Stice and Whitenton2002; Paxton et al., Reference Paxton, Neumark-Sztainer, Hannan and Eisenberg2006b; Smolak, Reference Smolak2009; Michael et al., Reference Michael, Wentzel, Elliott, Dittus, Kanouse and Wallander2014).

The perception that a person has of his or her physical self, and the thoughts and feelings that result from that perception, are involved in the concept of body image. Body image is defined as a multifaceted psychological construct that includes subjective attitudinal and perceptual experiences about one’s body, particularly its appearance (Cash & Pruzinsky, Reference Cash and Pruzinsky1990; Cash & Szymanski, Reference Cash and Szymanski1995). The four-dimensional model associated with this construct includes: perceptual dimension (one’s internal perception – how an individual estimates his or her own body size and/or shape), cognitive dimension (one’s thoughts – how an individual thinks he or she looks), affective dimension (one’s feelings – the way an individual feels he or she looks) and the fourth one – a behavioural aspect (refers to appearance-related behaviours such as grooming, checking, concealing) (Cash & Smolak, Reference Cash and Smolak2011).

Body image dissatisfaction refers to a subjective, negative evaluation of some aspect of one’s physical appearance (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Heinberg, Altabe and Tantleff-Dunn1999). The negative evaluation of body image develops when an individual’s beliefs about his or her own actual body size and/or shape (the actual self) do not match how the attributes are judged by others (the ideal self) (Grogan, Reference Grogan2008). According to the theoretical framework provided by the self-discrepancy theory, the actual/own versus ideal/own discrepancy corresponds to the absence of positive outcomes (dejection-related emotions) or presence of negative outcomes (agitation-related emotions) and resultant disappointment and dissatisfaction (Higgins, Reference Higgins1987).

Menarche (the first menstruation and the onset of menstrual bleeding) is the most apparent event of maturation in girls, a step within the process of pubertal development typically occurring after the peak of the growth spurt in height (Kaczmarek, Reference Kaczmarek2001, Reference Kaczmarek2012). In societies of Western culture, normal menarche timing can range from the ages of 9 to 16 (Kaplovitz & Oberfield, Reference Kaplovitz and Oberfield1999; Rosenfield et al., Reference Rosenfield, Lipton and Drum2009), with average age between 12 and 13, and with 12.78 years being the median age in Polish girls (Kaczmarek, Reference Kaczmarek2012). Early onset of menstrual status is characterized by anovulatory cycles, but they usually become ovulatory within the first gynaecologic year (World Health Organization, 1986). Menstrual cycles typically range from 21 to 35 days, and in adolescent females can last up to 45 days (Hillard, Reference Hillard2008). Each cycle consists of a cyclical sequence of changes in the ovaries (ovarian cycle) and uterus (uterine cycle). The ovarian cycle involves the process of oogenesis. The uterine cycle encompasses a series of changes in the endometrium of the uterus to receive a fertilized ovum.

The ovarian cycle consists of the follicular phase (postmenstrual), ovulation and luteal phase (premenstrual), whereas the uterine cycle is divided into menstruation, proliferative phase and secretory phase (Sembulingan & Sembulingan, Reference Sembulingan and Sembulingan2014). Menstrual cycles are counted from the first day of menstrual bleeding to the first day of next menstrual bleeding. Using the criterion proposed by Altabe and Thompson (Reference Altabe and Thompson1990), the entire duration of a menstrual cycle can be divided into three main phases: the menstrual phase, which begins on the first day of menstrual bleeding from the vagina, lasts 4–6 days and ends with the cessation of flow; the premenstrual phase, which includes the last 5 days of the luteal phase prior to the onset of menstrual bleeding; and the intermenstrual phase, which includes the time interval from one week following the cessation of flow to one week prior to the onset of menses, i.e. the remainder of the cycle.

Both the ovarian and uterine cycles are controlled by the neuroendocrine system (the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis, HPG) (Hall, Reference Hall2014). Changing hormone levels across the menstrual cycle significantly influence the female body with both physical (weight gain, bloating, breast sensitivity, abdominal crump) and emotional effects (mood swings, negative, depressive mood) (Farage et al., Reference Farage, Neill and MacLea2009). Consequently, they may have an impact on self-image and body (dis)satisfaction.

Several studies have investigated the association between different phases of the menstrual cycle and body image in healthy adult women. Faratian and colleagues (Reference Faratian, Gaspar, O'Brien, Johnson, Filshie and Prescott1984), studying 52 women who evaluated their perceived body image by adjusting the width of two vertical lights at several body regions, reported significant increases in perceived body size during the premenstrual phase. They found a statistically significant discrepancy between perceived body size and actual body size. Using the same methodology, Altabe and Thompson (Reference Altabe and Thompson1990) in their study of 60 participants aged 17–25 at differing menstrual phases, revealed that the greatest size overestimation difference between phases occurred perimenstrually (premenstrual and menstrual phases) when participants overestimated the depth of their waist. Using a figural drawing scale consisting of nine drawings ranging from very thin to obese, Carr-Nangle and colleagues (Reference Carr-Nangle, Johnson, Bergeron and Nangle1994) in their study of 26 normally cycling women between 18 and 40 years of age, found that measures of body size remained stable across menstrual phases but body dissatisfaction was the greatest during the perimenstrual (premenstrual and menstrual combined) phase of the cycle. Similar findings were reported by Racine and colleagues (Reference Racine, Culbert, Keel, Sisk, Burt and Klump2012), who evaluated (dis)satisfaction in body image in eighteen healthy adult women across the menstrual cycle using daily self-report measures. They found that body image dissatisfaction was likely to be greater during the mid-luteal/premenstrual phases than in the follicular and ovulatory phases. Jappe and Gardner (Reference Jappe and Gardner2009), using video distortion methodology, examined 30 young women (mean age 23.3 years, SD=3.9) and found that body image dissatisfaction was greater during the premenstrual and menstrual phases as compared with the intermenstrual phase. These findings corroborate the study conducted by Teixtera and colleagues (Reference Teixeira, Fernandes, Maques, Lacio and Dias2012) on 44 Brazilian university students (average age 23.3 years, SD=4.7), who evaluated their body image using a figural rating scale. The study revealed that dissatisfaction with body image peaked during the menstrual phase, with a significant increase after the premenstrual phase and a significant decrease after the menstrual phase. The reviewed literature has shown consistency in the role of different phases of the menstrual cycle on body dissatisfaction of adult women. However, these studies are relatively old and based on very small samples of women. Furthermore, there is a critical gap in the level of knowledge about adolescent girls. Aiming at addressing this issue, this study was undertaken to assess the association between different phases of the menstrual cycle and perceived body image in Polish adolescent girls aged 12–18 years, after controlling for other covariates, such as age, menstrual history (age at menarche and usual menstrual cycle length) and body weight characteristics. It is hypothesized that the perception of physical image among adolescent girls is differentiated by phases of the menstrual cycle according to the physical and emotional side-effects of physiological and hormonal fluctuations that occur during that period.

Methods

Participants

The initial sample consisted of 339 schoolgirls aged 12–18 in grades 1–3 of lower secondary and 1–2 of upper secondary schools in the Wielkopolska and Pomerania regions of Poland. The schools were randomly selected from government listings of secondary public schools in these two regions. Of 199 schools selected from the sampling frame (every tenth school), 38 schools (19.1%) responded to our invitation. Study participants were thus recruited by school participation. Eligibility criteria for participation in the study included (i) the absence of eating or menstrual disorders and/or any other chronic diseases/conditions that might affect menstrual cycle; (ii) having achieved menarche and regular menstrual cycles. Participation in the study was voluntary. The schools’ headmasters received an invitation letter and an information brochure about the research project. They approved the study protocol and gave permission to run the study in their schools. Furthermore, in collaboration with them, subjects’ parents were informed about the goals of the study and the possibility of refusing the participation of their children. Only those schoolgirls whose parents had given a written consent for them to participate were enrolled for the study. Of all invited parents, 7.8% declined participation of their children in the survey. In addition, schoolgirls who had attained the legal age for consent (16 years in Poland) gave their written consent for their participation in the study.

Study design and data collection procedures

The cross-sectional survey was carried out over the period from April to September 2009. The study design and data collection procedures were approved by the Bioethics Commission of the Poznań University of Medical Sciences and the Poznań Board of Education. The survey was carried out in compliance with the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration and subsequent amendments (World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki, 2001). The study protocol included a self-reported background data questionnaire, self-rated body image and anthropometric measurements.

Information about place of residence, menstrual history and menstrual cycle were obtained through a constructed and validated questionnaire (M. Kaczmarek, 2007 unpublished). Place of residence was then categorized according to regional geography into: village (up to 1000 inhabitants); small- to medium-sized town with fewer than 100,000 inhabitants; and large city with ≥100,000 inhabitants (Regional Data Bank of the Central Statistical Office, 2008).

Age at menarche, menstrual cycle duration and menstrual bleeding duration were indicated and recorded in the above-mentioned questionnaire by the subjects themselves. Age at menarche was reported retrospectively. The menstrual phase of a subject at the time of study was determined based on a retrospectively reported date of last menstruation, taking into account the menstrual cycle regularity, usual length of the cycle, duration of menstrual bleeding and the criterion proposed by Altabe and Thompson (Reference Altabe and Thompson1990). Three phases of the menstrual cycle were distinguished: the menstrual phase included the onset of the beginning of flow to the cessation at the end of flow; the premenstrual phase included the last 5 days of the luteal phase prior to the onset of flow; the intermenstrual phase included one week following the cessation of flow to one week prior to the onset of menses, i.e. the remainder of the cycle.

Data regarding body image perception were obtained using the Figure Rating Scale (FRS) developed by Stunkard and colleagues (Reference Stunkard, Sorenson and Schulsinger1983). The FRS instrument consists of nine schematic silhouettes, each marked with a number, ranging from 1, being the thinnest, most underweight body type, to 3 or 4, being the endomorphic-muscular type of a body, to 9, being the largest, most obese type. Participants were presented with a female version of the FRS and were asked to select the figure that most closely resembled their own body size, and the figure that they considered ideal and would like to look like. The level of body image dissatisfaction was derived through discrepancy scores by subtracting the score of the silhouette selected by the participants as the ideal from the one selected as the actual – the ideal-self discrepancy. Thus, negative or positive scores indicated the girl perceived herself as fatter or thinner than the ideal, respectively, whilst zero score indicated she was satisfied. Psychometric evaluation of the FRS instrument has proved acceptable reliability with a 2-week period test–retest value for the ideal variable of 0.71 and 0.83 for affective ratings (Thompson & Altabe, Reference Thompson and Altabe1991). Validity of the scale for adolescent girls has shown r=0.71 for correlation with actual weight and r=0.67 for correlation with body mass index (BMI) (Cohn et al., Reference Cohn, Adler, Irwin, Millstein, Kegeles and Stone1987).

Anthropometric measurements such as body height and weight were performed in school nursery rooms during morning hours and taken according to standard procedures (Knussmann, 1988/Reference Knussmann1992). Then, BMI was calculated by taking a subject’s weight (kg) and dividing it by her height squared (m2). Following the IOTF (International Obesity Task Force) recommendation, Cole’s cut-off values were used to determine the following weight status: underweight with three categories of thinness, normal/healthy weight, overweight and obese (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Bellizzi, Flegal and Dietz2000, Reference Cole, Flegal, Nicholls and Jackson2007). Chronological age was calculated in decimal values by subtracting the date of examination from the date of birth. The age groups were divided by years, defined in terms of the whole year, e.g. the 12-year-old group included subjects 12.00 to 12.99 years old.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated on the study sample, which consisted of 330 subjects (nine of the original 339 subjects were excluded due to incomplete data: they had been premenarcheal at the time of examination). The one-way ANOVA was used to determine differences in body image measures (actual body image, ideal body image and the ideal-self discrepancy – outcome variables) across levels of potential predictor factors (independent variables). General logistic regression (GLR) models were constructed to examine the association between the ideal-self discrepancy and the potential predictor variables. In these models, the dependent outcome variable was a dichotomous variable with two levels of ideal-self discrepancy in perceived body image: satisfied (no discrepancy between the ideal and actual body image – 0 score) versus dissatisfied (discrepancy between the ideal and actual body image scores – the absolute values), whereas menstrual cycle phase, chronological age at the time of examination and age at menarche, the urbanization level of place of residence, type of school, menstrual status, weight status and usual duration of menstrual cycle were used as potential predictor variables (independent variables). At first, bivariate (unadjusted) GLR models were constructed to evaluate associations of body dissatisfaction and all potential predictor variables singly. Variables that were significantly (at p<0.05) associated with body dissatisfaction in the bivariate analysis of the GLR model were entered into the multivariate analysis. A final explanatory model with a subset and odds ratio (OR) of the factors associated with body image dissatisfaction was obtained using a backward elimination procedure and rejection criterion of the p-value greater than 0.5. Statistical analyses were performed using the STATISTICA 10.0 data analysis software system (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). All significance tests comprised two-way determinations. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

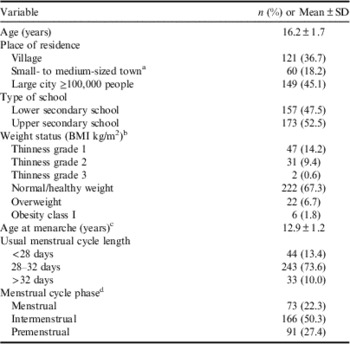

Table 1 shows the background characteristics of the 330 girls. They were aged between 12 and 18 years (mean age 16.2; SD 1.7 years), with 63.3% living in urban settings, 47.5% students of lower secondary schools and 52.5% students of upper secondary schools. The mean age at menarche was 12.9 years (SD=1.2). Seventy-three per cent reported menstruating every 28–32 days. At the time of the survey, 50.3% of the subjects were at the intermenstrual, 27.4% at premenstrual and 22.3% at menstrual cycle phase.

Table 1 Characteristics of sample, Polish adolescent girls aged 12–18 years (N=330)

a <100,000 people.

b Weight status was defined using the IOTF suggested cut-off points for BMI (see Cole et al., Reference Cole, Bellizzi, Flegal and Dietz2000, Reference Cole, Flegal, Nicholls and Jackson2007).

c Menarche age was self-reported.

d Menstrual phase: when there is menstrual flow; intermenstrual interval: remainder of the cycle, including the proliferative (follicular) phase and the first part of the secretory (luteal) phase; premenstrual phase: final part of the luteal phase, 5 days before the beginning of menstrual flow.

A large majority of the subjects (67.3%) had normal, healthy weight. Abnormal weight status included 24.0% of underweight, 6.7% of overweight and 1.8% subjects with obesity class I. The proportion of subjects reporting dissatisfaction with body image (the relative numbers) was 76.4%. The results also demonstrated that 65.2% of those dissatisfied with their bodies would like to be thinner, with only 11.2% of the subjects wishing to put on weight. Only 28.6% of the subjects admitted to being happy with how they looked (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Prevalence of adolescent girls who desired to be thinner, satisfied with their body and desired to be fatter.

Crude (unadjusted) associations between different measures of body image and potential predictor variables are shown in Table 2. One-way ANOVA indicated that weight status, age at menarche and menstrual cycle phase were associated with the actual body image and rate of ideal-self discrepancy (p<0.01; p=0.02; p=0.04 and p<0.01; p=0.04; p=0.03 for actual body image and ideal-self discrepancy, respectively). The ideal body image measure was independent of all variables except weight status (p<0.01). There was no significant association between different measures of body image and subjects’ chronological age, place of residence and type of school, and the usual length of menstrual cycle.

Table 2 Unadjusted associations between measures of perceived body image and potential predictor variables in Polish adolescent females using one-way ANOVA (N=330)

a Age groups: 12–14 years; 14–16 years; 16–18 years.

b Weight status: thinness grade 1; thinness grade 2; thinness grade 3; normal/healthy weight; overweight; obesity class 1.

c Age at menarche groups:<12 years; 12–14 years; >14 years.

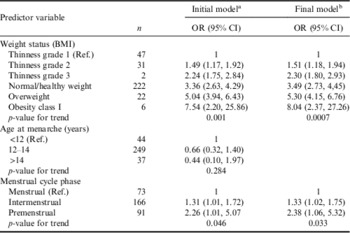

Unadjusted logistic regression analysis indicated that body dissatisfaction was directly associated with body weight status (p-value for trend <0.001; OR=12.26; 95% CI=3.54, 42.41), age at menarche (p-value for trend=0.036; OR=3.37; 95% CI=1.08, 10.52) and different phases of the menstrual cycle (p-value for trend=0.033; OR=2.32; 95% CI=1.07, 5.06) (see Table 3).

Table 3 Unadjusted logistic regression models to evaluate the association and odds ratio (OR) between dissatisfaction with body image and potential predictor variables

a USS: upper secondary school.

These crude associations were adjusted in the multivariate approach (Table 4). The final selected model obtained using the backward elimination method revealed that, adjusted for other factors, body dissatisfaction was significantly associated with increasing BMI (p-value for trend=0.0007) and different phases of the menstrual cycle (p-value for trend=0.033). Age at menarche, significantly associated with body dissatisfaction in the bivariate analysis, lost its significance in the multivariate approach.

Table 4 Adjusted associations between dissatisfaction with body image and predictor variables using multiple logistic regression models with backward elimination procedure

a Adjusted for age at menarche, weight status and phase of menstrual cycle; χ 2=16.085; df=3; p=0.001.

b Adjusted for weight status and the phase of menstrual cycle; χ 2=16.029; df=2; p=0.0003.

The adjusted odds ratio indicated an eight times greater probability of dissatisfaction with body image for subjects with obesity class I than their thinness grade 1 counterparts (OR=8.04; 95% CI=2.37, 27.26). The probability of body dissatisfaction among subjects differing by phases of the menstrual cycle was 2.4 times higher for subjects at their premenstrual cycle phase than those at the menstrual phase (OR=2.38; 95% CI=1.06, 5.32).

Discussion

Using a large sample of adolescent girls aged 12–18 years, the present findings demonstrated for the first time, to the authors’ knowledge, the differential effects of menstrual cycle phases on dissatisfaction with body image. The likelihood of body dissatisfaction among adolescent girls was 2.4 times greater for those at the premenstrual phase of the cycle as compared with their peers at the menstrual phase. These findings are in agreement with several other studies of body image dissatisfaction among adult women, which showed the association of increasing body dissatisfaction score with premenstrual cycle phase (Faratian et al., Reference Faratian, Gaspar, O'Brien, Johnson, Filshie and Prescott1984; Racine et al., Reference Racine, Culbert, Keel, Sisk, Burt and Klump2012) or premenstrual/menstrual phases combined (Altabe & Thompson, Reference Altabe and Thompson1990; Carr-Nangle, 1994; Jappe & Gardner, Reference Jappe and Gardner2009; Teixeira et al., Reference Teixeira, Fernandes, Maques, Lacio and Dias2012). Furthermore, the findings of the present study showed that body image dissatisfaction due to different phases of menstrual cycle can manifest as early as in adolescence.

The negative effects of the cyclical changes of the menstrual cycle on body image satisfaction have been well documented in terms of the premenstrual syndrome, which occurs during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and includes physiological (consequences of water retention), cognitive, emotional (negative mood) and behavioural (increased appetite) changes (Talen & Mann, Reference Talen and Mann2009; Staničić & Jokić-Bergić, Reference Staničić and Jokić-Bergić2010; Romans et al., Reference Romans, Kreindler, Asllani, Einstein, Laredo and Levitt2012; Helverson, Reference Helverson2013). The cyclical nature of these effects is caused by fluctuations in circulating hormones under the control of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis. In the follicular phase of the cycle, with the concentration of oestrogen rising, the brain becomes more and more animated and capable of receiving and processing a larger amount of information. In that period, women experience higher sensory sensitivity, improved well-being, liveliness, enthusiasm, higher self-esteem, are more sexually aroused and more prone to pleasure. Progesterone, on the other hand, causes the reduction of brain blood flow as well as oxygen and glucose consumption. For that reason, the activity of nervous cells is deteriorated, as is libido, mood and reception of stimuli; there arises anxiety, which, combined with fatigue, may lead to depression. Progesterone also has some mitigating effects as it contributes to the restoration of emotional stability. That condition is typical for the second (luteal) half of the cycle (Nowakowski et al., Reference Nowakowski, Haynes and Parry2010; Toffolettto et al., Reference Toffoletto, Lanzenberger, Gingnell, Sundstörm-Poromaa and Comasco2014). Due to a sudden drop of both hormones (oestrogen promoting well-being and progesterone mitigating mood changes) some 4–5 days before menstruation, woman's behaviour may fluctuate from hostility and aggression to a deep distress (McPherson & Korfine, Reference McPherson and Korfine2004; Baca-Garcia, et al., Reference Baca-Garcia, Diaz-Sastres, Ceverino, Perez-Rodriguez, Navarro-Jimenez and Lopez-Castroman2010; Kikuchi et al., Reference Kikuchi, Nakatani, Seki, Yu, Sekiyama, Sato-Suzuki and Arita2010). The monthly mood swings experienced by many adolescent girls can also affect the fluctuation of bodily self-perception across the menstrual cycle. The present results, and those of other authors, are consistent with presumptions about the effects of the fluctuation of progesterone and oestrogen levels in the course of the female menstrual cycle. However, these findings need additional data that can only be derived from longitudinal studies.

Duncan and colleagues (Reference Duncan, Ritter, Dornbusch, Gross and Carlsmith1985) examined the impact of the adolescence period on body image. They found that girls who begin puberty earlier tend to be more dissatisfied with their weight, with 69% of them wishing to be slimmer. According to the ‘off-time hypothesis’, deviation from the normative pubertal timing, whether advanced or delayed, is suggested to increase the likelihood of difficulties in adolescents’ adaptations to pubertal changes in physique (Alsaker & Flammer, Reference Alsaker and Flammer2006; Graber et al., Reference Graber, Brooks-Gunn and Warren2006).

Petroski and colleagues (Reference Petroski, Velho and De Bem1999) examined the association of menarcheal age with level of satisfaction with body weight in 1070 Brazilian female students of puberty age. They found that students who had matured earlier than their peers were more likely to report body dissatisfaction and wish to reduce their weight. These results are supported by observations from Abraham and colleagues (Reference Abraham, Boyd, Lal, Luscombe and Taylor2009) on 363 female school students from Australia, aged 12–17 years, participants in a cross-sectional computer survey. They indicated that the discrepancy between actual and desired weight (body weight dissatisfaction) was the greatest at 7–12 months and 13–24 months after menarche. The present estimates, however, did only reveal an unadjusted association between age at menarche and dissatisfaction with body image. This association lost its significance after adjusting for other covariates.

It has generally been accepted that body dissatisfaction among females is first noticeable when a girl is approaching puberty and experiencing physical changes as her body matures (Schroeder et al., Reference Schroeder, Hillary, Omar and Swedler2002; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Yeung and Lee2003; Lien et al., Reference Lien, Dalgard, Heyerdahl, Thoresen and Bjertness2006; de Guzman & Nishina, Reference de Guzman and Nishina2013). Adolescent girls are particularly vulnerable to developing a negative body image due to physical and sexual changes occurring during puberty (Bair et al., Reference Bair, Steele and Mills2014). The increasing prevalence of negative body perceptions among adolescent girls and the tendency towards wishing to be thinner have become a cultural norm in Western culture (Soh et al., Reference Soh, Touyz and Surgenor2006; Bair et al., Reference Bair, Steele and Mills2014).

In the same manner, these findings confirm the observations of other studies, i.e. a tendency of adolescent girls to rate their bodies too large and desire to reduce their weight. Al Sabbah and colleagues (Reference Al Sabbah, Vereecken, Elgar, Nansel, Aasvee and Abdeen2009), in their review of data from the Health and Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) 2001/2002 study, a cross-sectional survey of 11-, 13- and 15-year-old school children carried out in 35 countries and regions across Europe, Canada and USA, with the collaboration of the World Health Organization and encompassed more than 160,000 young people, reported that the percentage of girls dissatisfied with their body varied from 36.0% in Russia to 56.8% in Slovenia and 52.1% in Poland. In a subsample of overweight girls these figures were almost doubled: 56.6%, 81.6% and 77.6% for Russia, Slovenia and Poland, respectively. The proportion of subjects reporting dissatisfaction with body image in the present study was higher than that in the authors’ previous studies (76.4% in the present study vs 69.8% in Kaczmarek and Durda (Reference Kaczmarek and Durda2011)) and that observed among adolescent girls in Canada (47%) (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Bennett, Olmsted, Lawson and Rodin2001), in the United States (60%) (Presnell et al., Reference Presnell, Bearman and Stice2004) and in the majority of non-Western countries. Body image dissatisfaction among adolescent schoolgirls in Amman, Jordan, accounted for 21.2% of the sample (Mousa et al., Reference Mousa, Mashal, Al-Domi and Jibril2010), 16% in Saudi Arabia (Al-Subaie, Reference Al Subaie2000) and 13% in Palestine (Latzer et al., Reference Latzer, Tzischinsky and Asaiza2007). These figures provide evidence for Westernization of body image dissatisfaction.

Results on body image dissatisfaction similar to those found in the present study were reported by Pelegrini and colleagues (Reference Pelegrini, da Silva Coqueiro, Beck, Debiasi Ghedin, da Silva Lopes and Petroski2014) in their study of 317 Brazilian adolescent girls aged 14–19. The percentage of dissatisfied girls accounted for 78%, of whom those who desired to reduce their weight accounted for 65%. Girls were 4.2 times more likely to reduce their weight than boys (OR=4.17; 95% CI 2.60, 6.69).

In many investigations, the status of body weight described in terms of BMI is one of the main biological factors associated with body image dissatisfaction (Kostanski & Gullone, Reference Kostanski and Gullone1998; Thompson & Smolak, Reference Thompson and Smolak2001; Muris et al., Reference Muris, Meesters, van de Blom and Mayer2005; van der Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, Mond, Eisenberg, Ackard and Neumark-Sztainer2010; Pelegrini et al., Reference Pelegrini, da Silva Coqueiro, Beck, Debiasi Ghedin, da Silva Lopes and Petroski2014). Also in this study, the association of dissatisfaction with body image and BMI was quite prominent, indicating that obese adolescent girls were eight times more likely to rate their body image negatively than their underweight counterparts. There is general agreement that the higher the BMI, the higher the extent of body dissatisfaction and frequency of nutritional disorders (Mirza et al., Reference Mirza, Davis and Yanovski2005; Menzel et al., Reference Menzel, Schaefer, Burke, Mayhew, Brannicki and Thompson2010).

There are several limitations of this study that must be kept at the forefront when interpreting the results. Firstly, a cross-sectional design makes it difficult to assess the direction and causality. This design, however, was methodologically appropriate for answering the research question, i.e. evaluating the association between increasing body image dissatisfaction score (outcome variable) and exposures (selected biological and non-biological factors) (Mann, Reference Mann2003). Secondly, errors in recall of the exposure and possible outcome may produce a reporting bias. The reliability of self-reported data has widely been discussed in the literature and was taken into account in this study (Fan et al., Reference Fan, Miller, Park, Winward, Christensen and Grotevant2006). A further limitation may be the inaccuracy in identifying phases of the menstrual cycle on the calendar-based method. Indeed, the calendar method is not as accurate as ovarian hormonal assays but is acceptable by most studies. The strengths of the study include the school-based design survey of healthy adolescent girls, the multivariate approach and integration of multiple factors hypothesized to be associated with the outcome variable – dissatisfaction with body image.

In conclusion, body image is affected by many biological, social and individual factors. This study confirmed the association between body image dissatisfaction and different phases of the menstrual cycle when controlling for chronological age and body weight status. The premenstrual phase of the menstrual cycle appeared to be associated with the greatest score of body dissatisfaction compared with other menstrual phases. Investigation into the issue of body self-image is not only of cognitive, but also of practical value as understanding better the factors contributing to the formation of a negative body image may be instrumental in developing preventive health programmes targeted at young people.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and constructive suggestions, which led to an improvement of the manuscript. Both authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding this work.