INTRODUCTION

To meet the multiple objectives of poverty reduction, food security, competitiveness and sustainability, several researchers have recommended a farming systems approach (Norman Reference Norman1978; Byerlee et al. Reference Byerlee, Harrington and Winkelman1982; Shaner et al. Reference Shaner, Philipp and Schmehl1982). A farming system is the result of complex interactions among a number of inter-dependent components, where an individual farmer allocates certain quantities and qualities of four factors of production, namely land, labour, capital and management to which they have access (Mahapatra Reference Mahapatra1994). Farming systems research offers a tool for natural and human resource management in developing countries such as India. This is a multidisciplinary whole-farm approach and effective for addressing the problems of small and marginal farmers (Gangwar Reference Gangwar1993). The approach aims at increasing income and employment from smallholdings by integrating various farm enterprises and recycling crop residues and by-products within the farm itself (Behera & Mahapatra Reference Behera and Mahapatra1999). Under the gradual shrinking of land holding, it is desirable to integrate land-based enterprises such as fishery (pisciculture), dairy, poultry, duckery, apiary, field crops, vegetable crops (olericulture) and fruit crops (pomology), etc., within the bio-physical and socio-economic environment of the farmers to make farming more profitable and reliable (Behera et al. Reference Behera, Jha and Mahapatra2004). In the current review, some of the problems facing Indian agriculture are outlined and the potential for integrated farming systems research discussed, with emphasis on mathematical modelling, and illustrated by means of a novel case study.

BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT

The Indian economy is predominantly rural and agricultural, and the declining trend in size of land holding poses a challenge to the sustainability and profitability of farming. In view of the decline in per capita availability of land from 0·5 ha in 1950/51 to 0·15 ha by the turn of the century and a projected further decline to less than 0·1 ha by 2020, it is important to develop strategies and agricultural technologies that enable adequate employment and income to be generated, especially for small and marginal farmers who constitute more than 0·80 of the farming community (Jha Reference Jha2003). Devendra (Reference Devendra2002) advocated farming systems analysis and multi-disciplinary research for the development of small farms. No farm enterprise is likely to be able to sustain the small and marginal farmers without resorting to integrated farming systems (IFS), i.e. a system in which different enterprises (e.g. fishery, dairy, crop, etc.) are included in farm activities in an integrated manner with a major focus on bio-resource recycling within the system, for the generation of adequate income and gainful employment year round (Mahapatra Reference Mahapatra1992, Reference Mahapatra1994). Farming systems research, therefore, is a valuable approach to addressing the problems of sustainable economic growth for farming communities in India.

The IFS methodology could provide a pathway to achieve an ‘evergreen’ revolution in Indian agriculture (Swaminathan Reference Swaminathan1996). Hence, development of suitable IFS models for the small farmer in different agro-ecological regions of the country is important. The basic aim of an IFS is to derive a set of resource development and utilization practices, which lead to substantial and sustained increases in agricultural production (Kumar & Jain Reference Kumar and Jain2005). Farming system studies involving a number of enterprises and taking the physical, socio-economic and bio-physical environments into consideration are complicated, expensive and time-consuming (Mahapatra & Behera Reference Mahapatra, Behera, Panda, Sasmal, Nayak, Singh and Saha2004). There exists a chain of interactions among the components within the farming systems and it becomes difficult to deal with such inter-linking, complex systems. This is one of the reasons for slow and inadequate progress in the field of farming systems research in India and elsewhere (Jha Reference Jha2003). This problem could be overcome by the construction and application of suitable whole farm models (Dent Reference Dent1990). However, it should be mentioned that the inadequacy of available data from the whole farm perspective currently constrains the development of whole farm models.

During the last 4–5 decades of agricultural research and development in India, major emphasis has been given to component- and commodity-based research projects involving developing animal breeds, farm implements, crop varieties and farm machinery, mostly conducted in isolation and at the institute level. This component-, commodity- and discipline-based research has not proved wholly adequate in addressing the multifarious problems of small farmers (Jha Reference Jha2003). Following such approaches, it has been argued that several problems have appeared in Indian farming, such as declining resource use efficiency and declining farm profitability and productivity (Chopra Reference Chopra1993; Sharma & Behera Reference Sharma and Behera2004). Environmental degradation, including ground water contamination and entry of toxic substances into the food chain, has become a significant problem.

The problems of Indian agriculture are suited to a holistic approach to research and development efforts. It has been recognized that a new vision for agricultural research in the country, one that allows the commodity- and component-based research efforts at an institute level to be shifted to farmer-centric research and development efforts, is desirable (Mahapatra & Behera Reference Mahapatra, Behera, Panda, Sasmal, Nayak, Singh and Saha2004). The crop and cropping system-based perspective of research needs to make room for farming systems-based research conducted in a holistic manner for the sound management of available resources by small farmers (Gangwar Reference Gangwar1993; Jha Reference Jha2003). In farming systems research, small farmers are considered to be clients for agricultural research and development of technology (Rhoades & Booth Reference Rhoades and Booth1982; Chambers & Ghildyal Reference Chambers and Ghildyal1985; Ashby Reference Ashby1986). IFSs are often less risky, because if managed efficiently, they benefit from synergisms among enterprises, a diversity in produce, and environmental soundness (Lightfoot Reference Lightfoot1990; Lightfoot et al. Reference Lightfoot, Bimbao, Dalsgard and Pullin1993; Prein et al. Reference Prein, Lightfoot and Pullin1998; Prein Reference Prein2002; Pullin et al. Reference Pullin, Mathias, Charles and Baotong1998). On this basis, IFS models have been suggested for the development of small and marginal farms (Rangaswamy et al. Reference Rangaswamy, Venkitaswamy, Purushothaman and Palaniappan1996; Behera & Mahapatra Reference Behera and Mahapatra1999; Behera et al. Reference Behera, Jha and Mahapatra2004). Crop farming alone can be a risky venture and should not necessarily be the sole option for resource-poor farmers in developing countries.

Farming systems research can be used in the formulation of new agricultural systems for policy purposes. Development of a modelling approach to farming systems with due verification and validation using computer software, followed by on-farm experimentation, provides a sound basis for agricultural research. The most important contribution of farming systems research is that it provides a focus for all the disciplines involved in agricultural research and development, and it attempts to classify farmers into relevant categories for agricultural research and policy, while involving them in an active way (Fresco Reference Fresco1984). Sands (Reference Sands1986) reported that farming systems research is naturally farmer-oriented research, which cuts across disciplinary boundaries, centres on an on-farm, problem solving and operational approach, complements mainstream commodity research and also provides feedback from farmers. In the light of the background discussed above, a case study was undertaken with the objective of developing IFS models for different classes of farm size for generating adequate income and employment levels, and analysing the risk associated with a particular income level.

A CASE STUDY

The study area

The study was conducted in five villages: Ratanpur, Rautarapur, Palsipani, Siulia and Jhinti Sason in the Mayurbhanj, Balasore, Kalahandi and Puri districts, respectively, of Orissa state, India (Fig. 1). These villages are located in eastern India between 17°31′ and 20°30′N latitude and 81°31′ and 87°30′E longitude with the altitude of 26–200 m above mean sea level. The area receives an average rainfall of 1300 mm/annum, except in Palsipani where rainfall is around 750 mm/annum. The daily temperature reaches as high as 43°C in May and drops down to as low as 10°C in January. The average relative humidity varies from 84% in August to 66% between January and March. The mean daily bright sunshine hours varies from 4·8 in August to 9·3 in May. These villages are mostly dominated by scheduled tribes and scheduled castes and resource-poor farmers, the majority of whom run marginal or small farms.

Fig. 1. Map of the state of Orissa showing the sites of on-farm study. The study was conducted in five villages: Ratanpur, Rautarapur, Palsipani, Siulia and Jhinti Sason in the Mayurbhanj, Balasore, Kalahandi and Puri districts of India, respectively.

Data collection

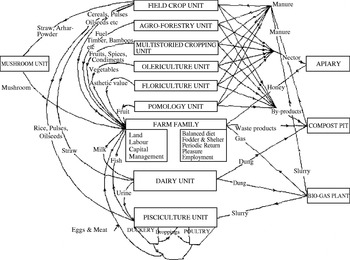

Socio-economic surveys were conducted using both Rapid Rural Appraisal and Participatory Rural Appraisal techniques (FAO 1995) in the five selected villages in Orissa from 1992/93 to 1996/97. Farms in these villages were categorized as marginal, small, medium and large, depending upon the size of the land holding (Table 1, Anonymous 2005). Resource availability and interactions of the different components within the farming system were recorded for each farm by questionnaire. Cost of production and output for each enterprise, and resource flow between the enterprises and interaction of various enterprises were also recorded. The farming systems in the area are characterized as pond- and rice-based involving fishery, poultry, duckery, apiary, mushroom horticulture and field crops (Table 1; Fig. 2). Many farm households have specialized in fishery and horticultural enterprises because of an adequate resource base and market accessibility.

Fig. 2. Interactions among different components of the farming systems.

Table 1. Enterprise options of different farm categories under varying resource availability and constraints for eastern India

* Data based on socio-economic surveys conducted in the five selected villages in Orissa state from 1992/93 to 1996/97.

† Numbers refer to the average options for different enterprises in the region by different categories of farmer which were recorded/observed during the process of socio-economic survey of the farmers in the selected villages.

Following pre-testing, a structured questionnaire was applied to a total of 120 farms. The head of the household was normally interviewed, although husband and wife were present throughout the interview in the majority of cases. The interview was generally conducted in the home or on the farm. The patterns of bio-resource flow and interactions were assessed from household survey data supplemented by information from group discussions and interviews with key informants, and Anganwadi workers (government-registered, village clerks) were used to produce bio-resource flow/interaction diagrams. The data were used for risk analysis through construction of whole-farm models using variants of linear programming at the laboratory of the Biomathematics Group in the School of Agriculture, Policy and Development in The University of Reading.

Multiple criteria analysis

In the traditional mathematical programming approach to modelling agricultural decision making, the decision maker seeks to optimize a well-defined single objective. In reality, this is not always the case as the decision maker is often seeking an optimal compromise among several objectives, many of which can be in conflict, or trying to achieve satisfying levels of his goals (Romero & Rehman Reference Romero and Rehman2003). Two multi-criteria programming techniques, goal programming and compromise programming (both variants of linear programming; see Thornley & France Reference Thornley and France2007 for variants of linear programming), were used in a study of small-scale dairy farms in central Mexico by Val-Arreola et al. (Reference Val-Arreola, Kebreab and France2006). In the current study, a linear programming model for compromise and risk in agricultural resource allocation was applied to develop whole farm models from the information obtained in the above surveys.

Traditional risk and uncertainty analysis is, by its nature, multi-objective with the twin concerns of profit and measuring its variability. The approach to risk programming in agricultural planning was proposed by Markowitz (Reference Markowitz1952). In this method, the risk to an agricultural enterprise is measured by the variability of its return using variance as the index. Low risk enterprises have relatively small variance, which means their returns are concentrated round the mean value. On the contrary, high-risk enterprises have relatively large variance and, therefore, their returns are dispersed round the mean value. Once the risk has been established in this manner, Markowitz (Reference Markowitz1952) introduced the concept of efficiency. A portfolio or mixture of agricultural enterprises is efficient if it has minimum variance for a given income or it has maximum income for a given variance. In this case, the total variance of a plan that is a mixture of enterprises is the objective function to be minimized. The constraint set for the problem includes an additional restraint measuring the expected income of the plan. Thus, the model has the two objectives of expected income and its variance.

Hazell (Reference Hazell1971) reduced the minimization of variance to minimizing mean absolute deviations (MOTAD); thus enabling an ordinary linear programming model to be solved rather than solving a parametric quadratic programming problem. The approach of Hazell defines efficiency in terms of expected income and mean absolute deviations and deals with two objectives. Moreover, the minimization of the mean absolute deviation implies minimizing the sum of the deviational variables measuring under- and over-achievement with respect to a null deviation in every period considered in the model. The method of risk programming called target MOTAD (Tauer Reference Tauer1983) was used in the current case study. In this approach, a target level of income T allows a deviation Y r in period r (=1, 2, …, 5 years in the current study). The net margin deviations and mean for each different enterprise over the consecutive 5 years are given in Table 2. The matrix of the model used for risk programming follows that given by Romero & Rehman (Reference Romero and Rehman2003). This yields a bi-criteria linear programming problem in which the net margins in each period are expressed as targets and the twin objectives are to minimize the sum of the absolute values of the net margin deviations and to maximize expected gross margin (Romero & Rehman Reference Romero and Rehman2003). MOTAD and its variants have had some application in analysing risk associated with farming in parts of sub-Saharan Africa (Maleka Reference Maleka1993; Adesina & Ouattara Reference Adesina and Ouattara2000).

Table 2. Net margin deviations and mean from different enterprises during 1992/93 to 1996/97 used for compromise programming

a Includes vegetables, fruit and field crops.

b Crossbred cow.

c Composite fish comprising Catla (Catla catla), Rohu (Labeo rohita), Mirgal (Cirrhinus mrigala) and Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella).

d 1 unit consists of 64 beds of paddy straw mushroom (Volvariella volvacea)/month from March to October and 100 bags of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus sadercaju) from November to February.

e 1 unit consists of 50 laying birds (Leghorn).

f 1 unit consists of 30 ducks (Khaki Campbell).

g Apiary unit of ISI eight framed box with bee species Apis cerana indica.

h KVIC and Dinabandhu model of biogas plant of 2 m3 capacity.

The constraint set

Resource availability and the constraints faced by the farmers in Orissa vary with the size of farm (Table 1). It is clear that marginal farmers suffer the most from limited availability of capital and land, though usually they have surplus labour for farm activities. In the case of marginal farms, due to a smaller land resource, mushroom cultivation is a potentially valuable enterprise for providing periodic income. All farmers derive their food from the farm by growing food crops, which include some horticultural crops to meet family requirements for vegetables and fruits. Apiary does not compete for land resources hence it is also an attractive enterprise for marginal and small farmers. This enterprise becomes more successful when adjacent farm areas are given over to floriculture. A marginal farmer must allocate a smaller number of apiary units while medium and large farmers can have more. There is a close interaction between fishery and duckery enterprises. If a farmer allocates a bigger area for fish ponds, he can also carry more ducks. Each family requires a single biogas plant, but large farmers can accommodate more units. A marginal farmer usually keeps one dairy cow, whereas a small farmer keeps two and medium and large farmers can keep 4 and 10 cows, respectively. Accordingly, they also make provision for an area for fodder. Marginal farmers generally do not keep ducks and poultry for commercial purposes because of capital constraints. However, small and marginal farmers usually keep the poultry and duckery enterprises in integration with the fish ponds, and the excreta of the ducks and poultry are generally recycled to the fish pond.

Devendra (Reference Devendra1983) and Devendra & Thomas (Reference Devendra and Thomas2002b) studied farming in south-east Asia with respect to various physical and bio-physical constraints faced by small farmers. They state that the traditional small farm scenario in Asia and India is characterized by low capital input, limited access to resources, low levels of economic efficiency, diversified agriculture and resource use, conservative farmers who are often illiterate and living on the threshold between subsistence and poverty, and suffers from a lack of ability to adopt new technology. Others, however, have argued that poor farmers are generally efficient but risk averse (e.g. Ghatak & Ingersent Reference Ghatak and Ingersent1984).

RESULTS

The IFS model for marginal farms

Enterprise options for a marginal farmer having a resource availability of 1 ha of land, 500 man-days of labour per annum for farm operations and Rs 50 000 as capital are given in Table 3. With this resource availability, the maximum income of Rs 49 734 was obtained with the maximum risk of Rs 16 354, whereas the lowest income of Rs 28 623 resulted in the lowest risk of Rs 4698. With increasing levels of income, the risk level also increased. At the highest level of income the area under crop was the maximum at 0·75 ha, whereas at the lowest level of income the area under crop was the least at 0·25 ha. The enterprise combination for a marginal farmer under low risk levels was crop (0·25 ha), dairy (1 unit), fishery (0·25 ha) and biogas (1 unit). At this level of income, the actual resource use was 0·5 ha land, 165 man-days of labour and Rs 32 154 of capital. Hence, under low risk levels, the available resources at the farmer's command are under-utilized. However, at the highest risk level, the enterprise allocations were crop (0·75 ha), dairy (1 unit), fishery (0·25 ha), mushroom (0·72 units), apiary (2 units) and biogas (1 unit). For this farm enterprise combination, the actual resource uses were 1 ha land, 401 man-days of labour and Rs 50 000 of capital. Thus under the high risk level of income his capital and land resources were fully utilized. However, his labour resource was under-utilized. For further increase in income, both land and capital were the limitation.

Table 3. Enterprise options for marginal farms in Orissa state obtained using multiple criteria decision making techniques

Fishery proved to be the least risky enterprise, for which area allocation was the same at the lowest as well as the highest risk level. In the case of the crop enterprise, area increased with increasing income. Hence, it was more risk-prone. The enterprise combination of dairy, crop and fishery is very common in the region. An enterprise like dairy gives a regular income to the farm family. Dung from the dairy enterprise is better recycled to the crop field and fish pond as biogas digested slurry. Animal and crop integration is a common feature of farming in these regions (Gill et al. Reference Gill, Samra and Singh2005). Behera et al. (Reference Behera, Jha and Mahapatra2004) generated a net income of Rs 19 991 from 0·4 ha of land (Rs 49 977/ha) for a marginal farm having different combinations of crop, poultry, fish, biogas and apiary. A similar level of income was recorded at the high level of risk in the present study. On-station studies in the lowland ecosystems of Tamil Nadu in southern India during 1987–92 by Rangaswamy et al. (Reference Rangaswamy, Venkitaswamy, Purushothaman and Palaniappan1996), taking marginal farmers' situations into consideration, revealed a net profit of Rs 11 755/year was obtained from a rice–poultry–fish–mushroom IFS with a 0·4 ha area (Rs 29 387/ha/year), whereas a conventional cropping system of rice–rice–green manure/pulses gave a net income of Rs 6334/year from the same area (Rs 15 835/ha/year). An IFS increased net income and employment from the farm holdings and provided a balanced diet for the resource poor farmers compared to a conventional cropping system.

The IFS model for small farms

Enterprise options for small farmers under varying resource limitations and availability are presented in Table 4. A small farmer having 2 ha of land, Rs 75 000 as capital for investment and 600 man-days of labour per year at his command generated a maximum income of Rs 77 292 with risk involvement of Rs 24 220, while at the lowest income level of Rs 58 983 the risk level was Rs 15 759. Increased income also involved increased risk. The enterprise combination at the lowest risk level was: crop (0·25 ha), fishery (0·5 ha), dairy, mushroom, poultry, duckery and biogas (1 unit apiece). But at the highest level of income and risk, the allocation of crop area increased to 1 ha and the apiary allocation was 4 units. At the lowest level of income and risk, actual resource use was 0·75 ha of land, 429 man-days of labour and Rs 64 950 of capital. Thus the resources of small farmers were under-utilized and among these three factors of production, land was highly under-utilized. With the increase in income and risk, use of these production factors also increased gradually. At the highest level income, actual resource use was land 1·5 ha, labour 590 man-days and capital Rs 75 000. In this case also, the land resource is under-utilized. Capital was the constraint on further increase in income.

Table 4. Enterprise options for small farms in Orissa state obtained using multiple criteria decision making techniques

Certain enterprises such as crops increased with increasing risk and income level, indicating that this enterprise involved a greater degree of risk for this group of farmers. The allocation of area for pisciculture at the high level of income and at the low level of income was the same, which shows that a fishery enterprise is less risk-prone and also profitable.

A similar IFS model for small farms based on on-station experiments into integrated farming suggested farm enterprises of crop, fishery, duckery, apiary, biogas and mushroom for optimum integration on a small land holding of 1·25 ha under eastern Indian conditions (Behera & Mahapatra Reference Behera and Mahapatra1999). The land was allocated for different enterprises in proportion to their significance to household needs and local market demand. The model generated a net income of Rs 58 000/year (Rs 92 800/2 ha) and employment of 573 man-days/year (917 man-days/2 ha/year) with the adoption of the suggested enterprise combination. Similarly Gill et al. (Reference Gill, Samra and Singh2005) reported a net income of Rs 73 973/ha from the model for an enterprise combination of rice–wheat+poultry+dairy+piggery+poplar tree+fishery when adapted to small farms in the Punjab (north-west India). The fishery and piggery integration was ideal not only from the income point of view but also for providing feed for the fishery enterprise through partly recycling the pig manure via the fish pond.

The IFS model for medium farms

Enterprise options for medium farmers are presented in Table 5. A medium farmer typically has around 4 ha of land, capital of Rs 150 000 for investment and 1200 man-days of labour per annum for allocating to different enterprises. With these resources, a maximum income of Rs 197 960 was obtained with a risk level of Rs 31 328, and a minimum income of Rs 138 082 involved a risk level of Rs 20 856. The enterprise combination for the minimum income was: crop (2 ha), dairy (1 unit), fishery (1·25 ha), mushroom (1 unit), poultry (1 unit), duckery (1·12 units), apiary (2 units) and biogas (1 unit). The crop enterprise allocation was the same for the maximum income, while there was a 1 unit increase in dairy allocation and the area under fishery increased from 1·25 to 2 ha. Also, there was further allocation of 2 units of poultry and 6 units of apiary, while there was no allocation for duckery. The option to select an area of more than 2 ha for crops was available but the area allocated remained fixed at 2 ha for all levels of income, while allocation of the area under fishery gradually increased, demonstrating that the crop enterprise involves little risk while the fishery enterprise involves greater risk. At the lowest level of income and risk, actual resource use was: land 3·25 ha, labour 886 man-days/year and capital Rs 98 219. In this instance, the farmer's available resources are under-utilized. With increasing income, use of all resources increased gradually. At the highest level of income, resource use was: land 4 ha, labour 1200 man-days/year and capital Rs 150 000. Thus, land, labour and capital resources are fully utilized at this level of income.

Table 5. Enterprise options for medium farms in Orissa state obtained using multiple criteria decision making techniques

The IFS model for large farms

Large farmers are in the most advantageous position with highest level of resource availability and the minimum level of resource constraints. The enterprise options for a large farm having resource availability of 10 ha of land, Rs 300 000 of capital and 2500 man-days/year of labour are given in Table 6. A large farmer could generate a maximum income of Rs 416 651 with a risk level of Rs 61 522, while the lowest risk of Rs 53 554 was associated with the lowest income (Rs 351 524). At the highest as well as lowest levels of income, all enterprises played a promising role. At the lowest level of income and risk, the allocation of enterprises was: crop (5 ha), dairy (4 units), fishery (3·2 ha), mushroom (2 units), poultry and duckery (2 units apiece), apiary (10 units) and biogas (2 units). At highest level of income, the enterprise allocation was: crop (5·97 ha), fishery (4 ha), apiary (15 units) and the remaining enterprises the same as for the lowest level. Actual resource use under the lowest income was: land 8·2 ha, labour 2200 man-days/year and capital Rs 266 635. Therefore, land, labour and capital were all under-utilized. Interestingly, at the highest level of income, the land, labour and capital resources of the farmers were almost fully utilized.

Table 6. Enterprise options for large farms in Orissa state obtained using multiple criteria decision making techniques

All farms

Examination of data on resource use efficiencies and farm profitability in terms of rupee invested on production inputs, taking all farm sizes and income and risk levels into consideration, revealed that the marginal farms were the most unprofitable with the returns of Rs 0·89 per rupee invested. This was followed by small, medium and large farms with returns per rupee investment of Rs 0·91, 1·41 and 1·32 respectively, at the lowest risk and income levels. A similar trend was observed in case of maximum risk and income level. With increase in farm income and risk levels, the resource use efficiency also increased. Medium and large farms proved to be more profitable than small and marginal farms with higher levels of resource use efficiency and return per rupee invested. This is due to cultivation of larger areas of crops and a higher level of other enterprises and greater farm mechanization, etc., which resulted in better utilization of available resources. On the other hand, fragmented holdings and small farms did not permit mechanization and there was inadequate use of available resources, resulting in low resource use efficiencies and overall lack of profitability.

DISCUSSION

Agricultural production is typically a risky business. Farmers face a variety of price, yield and resource risks that make their incomes unstable from year to year. In many cases, farmers are also confronted by the risk of catastrophe. Crops and livestock may be destroyed by natural hazards (floods, fire or drought), pests, soil limitations, etc. The types and severity of risk confronting farmers vary with the farming system, and with the climatic, policy and institutional setting. Nevertheless, agricultural risk is prevalent throughout the world, and it is particularly burdensome to small-scale farmers in developing countries. The adoption of new technologies by farmers will depend on perceived risk reduction of harvest failure as well as economic benefit for the household (Fox et al. Reference Fox, Rockström and Barron2005). Farmers often prefer farm plans that provide a satisfactory level of security even if this means sacrificing average income. More secure plans may involve adopting less risky enterprises, diversifying to a greater number of enterprises to spread risk, and using established technologies rather than venturing into new ones. To resolve this problem, techniques for incorporating risk-averse behaviour in mathematical programming models have been developed. The use of such techniques was illustrated in this review by applying target MOTAD (Tauer Reference Tauer1983) to the circumstances facing marginal, small, medium and large farmers in the eastern Indian state of Orissa.

To modify existing farming systems and to make them more profitable and sustainable, it is important to understand the interactions among their different components at the farm level. A change in any one component will significantly affect the others as well as the functioning of the entire system. Knowledge of inter-component linkages therefore leads to more efficient utilization of farm resources within each sector under different farming systems (Anandajaysekeran Reference Anandajaysekeran1997). The extent of linkages within farming systems has been assessed in an Indian context in this paper. Close examination of resource recycling (Fig. 2) shows the inter-dependence of the different components of the system in making the farmer self sufficient in terms of ensuring his family members have a sufficient food supply for leading a healthy life, increasing the standard of living through maximizing total net return, and providing more employment. A by-product of dairy, i.e. the cow dung, forms an important raw material for the biogas plant. The digested slurry of biogas forms a major part of feed for pisciculture by increasing plankton growth and supplies valuable manure for raising the productivity of field crops, olericulture, pomology and ornamental crops. Similarly, by-products of field crops such as paddy straw form a major ingredient of mushroom cultivation. Again, straw used for mushroom production is utilized for cattle feed and compost preparation. The by-product of poultry units, i.e. poultry droppings, forms an important feed material for pisciculture through increased plankton growth, as well as increasing the fertility of land to get higher yields from the crop enterprise. Even apiary has an indirect bearing on the crop enterprise by increasing yield and quality through improvement in pollination, in addition to providing farmers with a wholesome product in the form of honey. Similarly, farmers like to have flowers on the farm, which add to the aesthetic appearance of the family farm, and the flowers themselves serve as foraging plants for honeybees.

The integration of animals and crops is well developed in Asian farming systems, particularly in small-scale agriculture. There are marked complementarities in resource use in these systems, with inputs from one sector being supplied to another, such as using draught animal power and manure for crop production and crop residues as feed for animals. There is enough evidence of positive and economic benefits from animal–crop interactions that promote sustainable agriculture and environmental protection (Behera & Mahapatra Reference Behera and Mahapatra1999; Devendra Reference Devendra2002). Animal traction can improve the quality and timeliness of farming operations, thus raising crop yields and incomes. The manures from animal enterprise contribute considerably to the maintenance of soil fertility and improve crop productivity and sustainability of farming systems. Livestock provide a least-cost, labour-efficient route to intensification through their role in nutrient cycling. Keeping animals on the farm provides a use for other resources such as crop residues which might otherwise be wasted (Devendra Reference Devendra2002). In India, bullocks, buffalos, equines, camels and yak are important for draught power in different agro-ecological zones. The production of draught bullocks is still a major aspect of cattle rearing in India (Singh Reference Singh, Devendra and Gardiner1995).

Crop production provides a range of residues and agro-industrial products that can be utilized by both ruminants and non-ruminants. These include cereal straw (viz. rice, wheat and maize), sugarcane tops, grain legume haulms (viz. groundnut and cowpea), root crop tops and vines (viz. cassava and sweet potato), oilseed cakes and meals (viz. oil palm kernel cake, cotton seed cake and copra cake), rice bran and bagasse (Behera et al. Reference Behera, Kebreab, Dijkstra, Assis and France2005). In Asia, rice straw is the principal fibrous residue fed to >0·90 of ruminants. Devendra (Reference Devendra and Renard1997) calculated that 0·30 of rice straw is used for feed in south-west Asia. In south-east Asia, systems combining animals with annual cropping and those integrating animals with perennial tree crops are very common. In all cases, without exception, the interactions between crops and animals were positive and beneficial. The benefits were directly associated with increased productivity, increased income and improved sustainability (Pant et al. Reference Pant, Demaine and Edwards2005; Shekinah et al. Reference Shekinah, Jayanthi and Sankaran2005).

Economic performance from 1985 to 1992 for three sizes (1·2, 2·5 and 5 ha) of farmer-managed farm showed that dairy production contributed most to the total gross profits (0·31, 0·63 and 0·69, respectively) (de Jong et al. Reference de Jong, Kuruppa, Jayawardena and Ibrahim1994). Animals also contributed significantly to an improvement in soil fertility through manure and biogas production was able to replace domestic fuel needs. Both ruminants and non-ruminants provided manure for the maintenance and improvement of soil fertility. Manure is used widely throughout south-east Asia, where the use of artificial fertilizer is low and soil fertility depletion is a major constraint to agriculture, particularly in humid and sub-humid climates. In integrated crop–pig–aquaculture systems in south-east Asia, pig manure is drained and the clear effluent applied as fertilizer to vegetable plots or rice fields and fish ponds (Gill et al. Reference Gill, Samra and Singh2005). The solid component is used for biogas production. In integrated rice–duck–aquaculture systems, duck excreta fertilize the rice crop and also provides food for the fish (Devendra & Thomas Reference Devendra and Thomas2002a).

The vast majority of farmers in the Orissa region do not have the resources to replace draught animal power with tractors. Devendra (Reference Devendra1993; Reference Devendra1996) revealed the results of long-term case studies. The pattern and magnitude of bio-resource flow in IFSs varied taking different enterprises into consideration. The degree of synergism through mutually rain-forcing linkages among crops, livestock and aquaculture was high in comparison to other enterprises in the system. The entire IFS philosophy revolves around better utilization of time, money, resources and labour by farm families (Behera & Mahapatra Reference Behera and Mahapatra1999; Behera et al. Reference Behera, Jha and Mahapatra2004). The farm family obtains scope for gainful employment the year round thereby ensuring a reasonable income and higher standard of living.

Taking all the above into consideration, it can be stated that there is a demand for a holistic approach to technology generation and dissemination, in addition to the traditional component approach. Projection through development agencies or extension functionaries of a whole farm scenario for farm income based on an IFS is lacking (Mahapatra & Behera Reference Mahapatra, Behera, Panda, Sasmal, Nayak, Singh and Saha2004). In this context, construction and application of whole farm models by using linear programming methods, though they do not account for socio-cultural issues, are valuable for resource allocation and enterprise selection. In extension and developmental programmes in most developing countries, the respective agencies generally go to farmers and give a variety of advice in an ad hoc manner. Few appear to put a clear-cut whole farm scenario forward for consideration (Mahapatra & Behera Reference Mahapatra, Behera, Panda, Sasmal, Nayak, Singh and Saha2004). In the context of present challenges to make small farms profitable not only in India, but also in most of the Asian and other developing countries, it is necessary to place an overall scenario for farm income and employment generation and other associated benefits before the small and marginal farmers in order to motivate them. Placing such pictures before farmers will aid their confidence to adopt new technologies in an integrated manner for enhancing farm income and employment, thereby helping to provide a socio-economic uplift to farmers in the region.

CONCLUSION

IFSs are important for the efficient management of available resources at the farm level to generate adequate income and employment for the rural poor, for the promotion of sustainable agriculture, and for the protection of the environment. The synergistic interactions of the components of farming systems need to be exploited to enhance resource use efficiency and recycling of farm by-products. The farming systems approach to agricultural research and development efforts should be adopted as an important strategy to accelerate agricultural growth and thereby provide leverage for transforming poverty-prone rural India into a more prosperous India.

The constructive criticism and additional references provided by an anonymous reviewer is gratefully acknowledged. Funding support and help for the proposed study was provided by the Indian National Science Academy, New Delhi and the Royal Society, London, under their bilateral scientific exchange programme.