Introduction

Hair sheep show traits that are desirable for lamb production, especially in extensive production systems (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Pereira, Silva, Paulino, Mizubuti, Pimentel, Pinto and Rocha Junior2013) and represent an important genetic resource for producing lambs (McManus et al., Reference McManus, Bianchini, Paim, de Lima, Neto, Castanheira, Esteves, Cardoso and Dalcin2015). These animals are usually bred in the Caatinga biome (Maciel et al., Reference Maciel, Carvalho, Batista, Guim, Souza, Maciel, Pereira Neto and Lima Junior2015), which exhibits seasonal fluctuations in feed availability during the year. Farmers’ dependence on the availability of feed from nature has been the primary problem facing hair sheep production in semi-arid regions.

The ability of ruminants to undergo metabolic and endocrine adaptation to feeding restrictions depends on species and physiological characteristics (Rodrigues et al., Reference Rodrigues, Chizzotti, Martins, da Silva, Queiroz, Silva, Busato and Silva2016), as well as age, sex and breed (de Araújo et al., Reference de Araújo, Pereira, Mizubuti, Campos, Pereira, Heinzen, Magalhães, Bezerra, da Silva and Oliveira2017). In addition to nutritional variables, which are important for adjustments in animal management practices, it is necessary to be concerned with the physiological aspects of animals bred in these regions. Thermal measurements taken in production systems allow verification of the animals’ welfare and the impacts of specific alimentary plans on thermoregulatory processes (Knizkova et al., Reference Knizkova, Kunc, Gürdil, Pınar and Selvi2007; McManus et al., Reference McManus, Bianchini, Paim, de Lima, Neto, Castanheira, Esteves, Cardoso and Dalcin2015).

Given the many functions that nutrients fulfil in animals’ bodies, adequate protein and energy supplies during growth are of paramount importance (Rodrigues et al., Reference Rodrigues, Chizzotti, Martins, da Silva, Queiroz, Silva, Busato and Silva2016; Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Lima, Marcondes, Rodrigues, Campos, Silva, Bezerra, Pereira and Oliveira2017). Knowledge of the effect of feed restriction on growing hair sheep (Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Fontenele, Silva, Oliveira, Ferreira, Mizubuti, Carneiro and Campos2014) is of global importance because it would allow the development of better food strategies and would reduce costs in the formulation of diets (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Pereira, Silva, Paulino, Mizubuti, Pimentel, Pinto and Rocha Junior2013) and environmental perspectives. Therefore, the hypothesis investigated in the current paper was that feed restriction could affect intake, digestibility, microbial efficiency synthesis and heat tolerance. In this context, the current study was conducted to evaluate the impact of dietary reduction on nutrient intake and digestibility, feeding behaviour, urinary excretion of purine derivatives (PD), nitrogen balance and rectal and superficial temperatures in growing Morada Nova lambs.

Materials and methods

Animals, treatments and general procedures

Thirty-five hair lambs (14.5 ± 0.89 kg initial BW, 2 months old) were used in a completely randomized study with a 3 × 3 factorial arrangement with three sex classes (11 intact males, 12 castrated males and 12 females) and three levels of feeding (ad libitum, 300 and 600 g/kg/dry matter (DM) feed restriction for 120 days). The lambs were placed in individual pens equipped with feeders and water troughs.

All lambs were fed a similar diet throughout the experimental trial. A total mixed ration (TMR) (Table 1) was formulated to meet the nutritional requirements of late-maturity lambs as defined by the NRC (2007) with a gain of 150 g/day. In the formulation of the TMR, Tifton 85 hay (Cynodon sp.) was used as roughage (600 g/kg/DM). The lambs were fed twice daily, at 07.30 and 16.00 h, allowing for up to 100 g/kg/DM refusals only for animals fed ad libitum, and their intake was recorded on the basis of the daily feed supply. Before each morning feeding, the refusals from the previous day's feedings for each animal fed ad libitum were removed and weighed to calculate the intake and feeding levels of the lambs of each sex class submitted to 300 and 600 g/kg/DM feed restriction. Every 15 days, the lambs were weighed in the morning (at 07.00 h, before feeding) to obtain their body weight (BW).

Table 1. Ingredient and chemical composition of experimental ration

NDFap, neutral detergent fibre corrected for ash and protein.

a Composition, 1 kg of premix: calcium 225–215 g; phosphor 40 g; sulphur 15 g; sodium 50 g; magnesium 10 g; cobalt 11 mg; iodine 34 mg; manganese 1800 mg; selenium 10 mg; zinc 2000 mg; iron 1250 mg; copper 120 mg; fluor 400 mg; vitamin A 37.5 mg; vitamin D3 0.5 mg and vitamin E 800 mg.

Digestibility trial, collection of urine and determination of microbial protein synthesis

The digestibility trial was carried out indirectly using indigestible neutral detergent fibre (iNDF) as to estimate faecal DM excretion. Every 15 days, at specific times (08.00 h on the first day, 12.00 h on the second day and 04.00 h on the third day), faeces were collected from the animals’ rectal ampulla. Faecal samples, refusals, concentrate and Tifton 85 hay were incubated in situ over a period of 240 h in the rumen of a cow receiving an experimental feed. After, the bags were washed in water until they became clear (Van Soest et al., Reference Van Soest, Robertson and Lewis1991), and the residue was weighed and considered to be the iNDF. An estimate of the total digestible nutrients (TDN) was calculated according to Weiss (Reference Weiss1993) as follows:

where CP is the crude protein, NFC is the non-fibre carbohydrates, NDFap is the neutral detergent fibre corrected for ash and protein and EE is the ether extract. Subscript d means digestible.

Spot urine samples were collected every 20 days, approximately 4 h after the morning feeding, during spontaneous urination, used for analysis of PD to estimate microbial protein synthesis (MPS). For collection of urine from males, plastic collectors adapted to the animal's body were used. Disposable urethral catheters were used to collect urine from females. Samples of urine (5 ml) were collected, diluted with 45 ml of a solution of 0.018 mmol sulphuric acid (H2SO4), and stored at −20 °C. The concentration of creatinine in the urine was determined using a commercial kit (Labtest, Lagoa Santa, MG, Brazil) to estimate the urinary volume.

The analysis of allantoin in the urine was performed using a colorimetric method (Fujihara et al., Reference Fujihara, Ørskov, Reeds and Kyle1987). The concentration of uric acid was evaluated using an enzymatic colorimetric test with clearing factor lipase (Barham and Trinder, Reference Barham and Trinder1972; Fossati et al., Reference Fossati, Prencipe and Berti1980), and the creatinine concentration was analysed using the alkaline picrate method (Henry et al., Reference Henry, Cannon and Winkelman1974). To estimate microbial purine derivative absorption (AbsPD), the following equations were used, proposed by Chen and Gomes (Reference Chen and Gomes1992):

where Y is expressed in mmol/day, X is the AbsPD (mmol/day), 0.84 represents the recovery of absorbed purines as PD in urine, and the component within brackets represents the endogenous contribution, which decreases as exogenous purines become available for utilization by the lambs.

where MN is microbial nitrogen (g N/day), assuming that the N concentration of purine is 70 mg N/mmol, the ratio of purine N to total N in mixed ruminal microbes is 11.6:100, and the digestibility of microbial purines is 0.83. The MN values were multiplied by a factor of 6.25 to obtain microbial crude protein (CPmic). Subsequently, the MPS was calculated using the following equation:

The amounts of N intake (g/day) and N excreted in faeces and urine were considered for calculation of the N balance (NB). Nitrogen retention was calculated as the difference between NB and basal endogenous nitrogen loss (BEN), assuming the endogenous tissue and dermal N losses to be 0.35 and 0.018 metabolic weight, respectively. The equation to calculate the BEN was:

The value of nitrogen retained (NR) was expressed as NR = NB−BEN. Endogenous urinary losses (EUL) were calculated from the equation adapted for sheep by ARC (1980):

Ingestive behaviour and infrared thermography

Ingestive behaviour of lambs was characterized by measuring feeding time (TAL, h/day) and rumination time (TRU, h/day) at 10 min intervals for 24 h, every 20 days, according to the methodology proposed by Johnson and Combs (Reference Johnson and Combs1991). To evaluate thermal stress on the animals, rectal temperature (RT) was measured at 09.00 and 14.00 h with a digital thermometer inserted near the rectal ampulla of the animal, at a depth of approximately 3.5 cm. The Iberia heat tolerance test was used to determine the heat tolerance coefficient, a measure of the adaptability of the animals, according to the following equation:

where HTC = heat tolerance coefficient; 100 = maximum efficiency to maintain body temperature at 39.1 °C; 18 = constant; RT = average RT (°C) based on readings at 09.00 and 14.00 h; and 39.1 °C = average RT considered normal for sheep (Reece et al., Reference Reece, Erickson, Goff and Uemura2015).

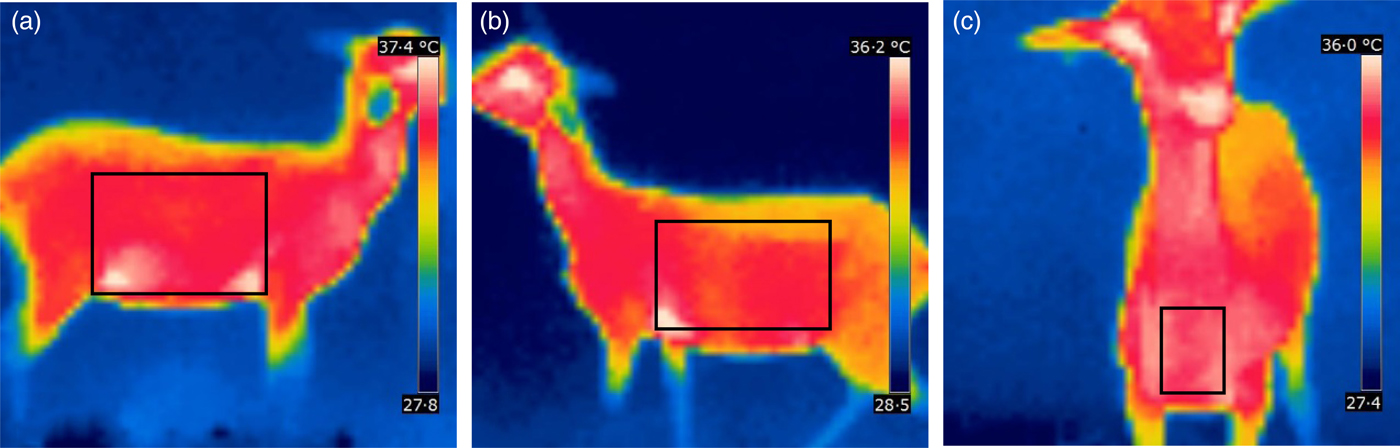

Thermal scanning of lambs was performed using an infrared camera (FLIR, 620 series; FLIR Systems Co. Ltd., St Leonards, New South Wales, Australia). Temperatures were measured in the regions of the rib and the flank from the right and left sides and in the pectoral region of the animal (Fig. 1). The measurements were taken every 20 days for three consecutive days, totalling 3780 images at the end of the experimental period, which were analysed using Quick Report® software. For the analysis of temperatures, rectangles were drawn using the ‘Area’ tool, which defines the mean temperature of a delimited area.

Fig. 1. Thermographic images and temperature collection areas of Morada Nova lambs. Regions of the right side (A), left side (B) and pectoral region (anterior aspect) (C).

The air temperature (TA) and relative humidity (RH) were measured every 15 min by means of two data loggers placed on the premises at the collection point for the physiological parameters. The temperature–humidity index (THI) was obtained by the formula described by Buffington et al. (Reference Buffington, Collier and Canton1983):

where Tdb is the dry bulb temperature. The mean temperature during the experimental trial was 28.8 °C (morning: 27.6 °C; afternoon: 30.0 °C), and the RH was 77.3% (morning: 78.1%; afternoon: 64.9%).

Analysis and calculations

Samples of the ingredients, orts and faeces were dried in a forced air oven at 55 °C for 72 h, ground to pass through a 1 mm screen (Wiley Mill, Arthur H. Thomas, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and subsequently analysed for DM (AOAC, 1990; method number 967.03), ash (AOAC, 1990; method number 942.05), CP (AOAC, 1990; method number 981.10), EE (AOAC 1990; method number 920.29), acid detergent fibre (AOAC 1990; method number 913.18), neutral detergent fibre (NDF, Van Soest et al., Reference Van Soest, Robertson and Lewis1991) and fibrous carbohydrates (Sniffen et al., Reference Sniffen, O'Connor, Van Soest, Fox and Russell1992). The NDF analysis was performed using thermostable α-amylase without sodium sulphite and was corrected for residual ash (Mertens, Reference Mertens2002) and residual nitrogenous compounds (Licitra et al., Reference Licitra, Hernandez and Van Soest1996). The quantity of NFC was calculated using an equation described by Hall (Reference Hall2000):

Total carbohydrate content (TC) was calculated according to Sniffen et al. (Reference Sniffen, O'Connor, Van Soest, Fox and Russell1992):

Statistical analysis

The data were subjected to analysis of variance using the GLM procedure in SAS version 9.0 (SAS® Inst. Inc., Cary, NC, USA) with the following mathematical model:

where Y ijk is the dependent or response variable measured in animal or experimental unit ‘k’ of sex class ‘i’ at feed restriction ‘j’; μ is the population mean or global constant; S i is the effect of sex class ‘i’; R j is the effect of feed restriction ‘j’; S i × R j is the interaction between effects of sex class ‘i’ and feed restriction ‘j’; and ε ijk is the unobserved random error. Tukey–Kramer's test was used to compare the means at P < 0.05 and the same criterion was adopted for interactions between the effects of sex and feed restriction.

Thermographic results were evaluated according to a mathematical model:

where Y ijkl is the dependent or response variable measured in the animal or experimental unit ‘l’ of sex class ‘i’ at feed restriction ‘j’ and period ‘T’; μ is the population mean or global constant; S i is the fixed effect of sex class ‘i’; R j is the fixed effect of feed restriction ‘j’; T k is the fixed effect of period ‘k’; S i × R j is the interaction between effects of sex class ‘i’ and feed restriction ‘j’; S i × T k is the interaction between sex class ‘i’ and period ‘k’; R j × T k is the interaction between feed restriction ‘j’ and period ‘k’; S i × R j × T k is the interaction of sex class ‘i’, feed restriction ‘j’ and period ‘k’; and ε ijkl is the unobserved random error. The Tukey–Kramer test was used to compare the means at P < 0.05 and the same criterion was adopted for interactions among the effects of sex, feed restriction and period.

Results

There were effects of sex and feed restriction (P < 0.05) on nutrient intake (Table 2). Intact and castrated males consumed more DM and NDFap (%BW and BW0.75) than females (P < 0.05). Neither eating time nor ruminating time was affected by sex. Feed restriction influenced nutrient intake significantly (P < 0.05). Dry matter intake, NDFap intake (%BW and BW0.75) and eating time were highest in lambs with ad libitum intake (P < 0.05), followed by lambs subjected to 300 g/kg/DM feed restriction. Time spent ruminating was similar for animals subjected to ad libitum feeding and 300 g/kg/DM feed restriction.

Table 2. Effects of sex class and feed restriction on nutritional variables in hair lambs (means and ± s.d.)

s.d., standard deviation; s.e.m, standard error of the mean; DM, dry matter; NDFap, neutral detergent fibre corrected for ash and protein; NFC, non-fibre carbohydrates; TDN, total digestible nutrients; BW, body weight.

a Sex class: IM, intact males; CM, castrated males; F, females.

b Feed restriction: ad libitum (AL) or 300 or 600 g/kg/DM reduction of the AL intake.

There was no influence of sex class on the CP, EE or NFC digestibility coefficient (Table 3). Sex class influenced DM digestibility (P < 0.05), which was highest in castrated males. The digestibility of DM and CP was lower (P < 0.05) in animals fed ad libitum than in animals subjected to 300 or 600 g/kg/DM feed restriction (P < 0.05). Ether extract digestibility (P < 0.05) was highest in animals subjected to 300 g/kg/DM feed restriction.

Table 3. Effect of sex class and feed restriction on digestibility coefficients in hair lambs (means and ± s.d.)

s.d., standard deviation; s.e.m, standard error of the mean.

a Sex class: IM, intact males; CM, castrated males; F, females.

b Feed restriction: ad libitum (AL) or 300 or 600 g/kg/DM reduction of the AL intake.

There were interaction effects (P < 0.05) of sex and feed restriction on OM, NDFap and TC digestibility (Table 4). At 300 g/kg/DM feed restriction, the digestibility of OM and NDFap was lowest in intact males; however, intact males, castrated males and females did not differ when subjected to ad libitum feeding or 600 g/kg/DM feed restriction. Total carbohydrate digestibility was highest at 600 g/kg/DM (P < 0.05) in all sex class.

Table 4. Interaction effects of sex class and feed restriction on nutrient digestibility coefficients in hair lambs (means and ± s.d.)

s.d., standard deviation; s.e.m, standard error of the mean; OM, organic matter; NDFap, neutral detergent fibre corrected for ash and protein; TC, total carbohydrates.

a Sex class: IM, intact males; CM, castrated males; F, females.

b Feed restriction: ad libitum (AL) or 300 or 600 g/kg/DM reduction of the AL intake.

Nitrogen retention, purine derivatives and microbial efficiency

Nitrogen intake, faecal nitrogen, BEN and EUL were higher in intact males (P < 0.05) (Table 5). Feed restriction influenced the overall balance of N compounds (P < 0.05) and lambs subjected to 600 g/kg/DM feed restriction excreted those compounds at lower levels than lambs under the other feeding conditions.

Table 5. Effects of sex class and feed restriction on nitrogen balance and purine derivatives in hair lambs (means and ± s.d.)

s.d., standard deviation; s.e.m, standard error of the mean.

BEN, basal endogenous nitrogen loss; EUL, endogenous urinary losses; BW, body weight.

Total PD, total purine derivatives; Xant and Hypoxant, xanthine and hypoxanthine; CP, crude protein; MP, microbial protein synthesis; TDN, total digestible nutrients; AbsPD, purine derivative absorption.

a Sex class: IM, intact males; CM, castrated males; F, females.

b Feed restriction: ad libitum (AL) or 300 or 600 g/kg/DM reduction of the AL intake.

§ Nitrogen, amounts of Nitrogen

¶ Excretion of DP, Excretion of Digestible Protein

†† CPmic, microbial crude protein

Urine output and creatinine excretion were not influenced by sex class or feed restriction (Table 5). Sex class did not affect allantoin, xanthine and hypoxanthine, AbsPD, total PD, CPmic or MPS, but did affect uric acid excretion (P < 0.05); the values of the latter were higher in males than in females. Allantoin, uric acid, AbsPD, total PD and CPmic production were lowest in the animals subjected to 600 g/kg/DM feed restriction (P < 0.05). The efficiency of MPS was highest in the animals subjected to 600 g/kg/DM feed restriction (P < 0.05).

Thermographic temperatures

Surface temperatures on the right and left sides (Fig. 1) and the front pectoral region, as well as RT, were influenced by feed restriction and period (P < 0.05, Table 6). The lowest temperatures (P < 0.05) were observed in animals subjected to 600 g/kg/DM feed restriction. Decreased temperatures were also recorded in the morning period (P < 0.05). HTC was highest in animals subjected to 600 g/kg/DM feed restriction (P < 0.05).

Table 6. Infrared thermography (°C), rectal temperature (°C) and heat tolerance coefficient according to sex class, feed restriction and time period in hair lambs (means and ± s.d.)

s.d., standard deviation; s.e.m, standard error of the mean.

a Sex class: IM, intact males; CM, castrated males; F, females.

b Feed restriction: ad libitum (AL) or 300 or 600 g/kg/DM reduction of the AL intake.

c Period: M, morning; A, afternoon.

There was an interaction effect (P < 0.05) of sex class and feed restriction on surface temperature on the right side of the sheep (Table 7), whose lowest morning values were in females subjected to 600 g/kg/DM feed restriction and whose lowest afternoon values were in females and castrated males subjected to 600 g/kg/DM feed restriction.

Table 7. Infrared thermography according to different sex classes and feed restriction levels in hair lambs during different time periods (means and ± s.d.)

s.d., standard deviation; s.e.m, standard error of the mean.

a Sex: IM, intact males; CM, castrated males; F, females.

b Feed restriction: ad libitum (AL) or 300 or 600 g/kg/DM levels of the AL intake.

c Period: M, morning; A, afternoon.

d IRT right side = infrared thermography of the right side.

Discussion

Digestibility in the rumen results from the competition between digestion and passage rates (Dhanoa et al., Reference Dhanoa, France, Siddons, Lopez and Buchanan-Smith1995), and passage rate is positively correlated with intake of DM (Van Soest, Reference Van Soest1994). The greatest protein digestibility coefficients for animal diets are observed feed restriction, which can be explained by the reduction of the contribution of endogenous losses. The use of nitrogen compounds in the restricted animals was marked by decreased excretion of urinary nitrogen, indicated by a positive nitrogen balance, because there was intensified nitrogen recycling and increased conservation of compounds, reducing the amount of protein lost to the environment. Intact males had higher intake and nutrient utilization efficiency than either of the other classes. This is because males have higher energy and protein requirements for growth (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Pereira, Silva, Paulino, Mizubuti, Pimentel, Pinto and Rocha Junior2013; Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Fontenele, Silva, Oliveira, Ferreira, Mizubuti, Carneiro and Campos2014), demanding higher intakes (NRC 2000, 2007).

Microbial nitrogen compounds were affected by feed restriction. Knowledge of microbial protein production (Fujihara et al., Reference Fujihara, Shem and Matsui2007) is indispensable for feed strategies, mainly to meet the protein requirements of animals (Valadares Filho et al., Reference Valadares Filho, Costa e Silva, Gionbelli, Rotta, Marcondes, Chizzotti and Prados2016). Thus, the use of PD excretion in urine is a useful tool to measure the production of nucleic acids by rumen microorganisms (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Hovell, Ørskov and Brown1990), and in feed-restricted animals, PD excretion measurement enables knowledge of the amino acids available in the duodenum (Chizzotti et al., Reference Chizzotti, Valadares Filho, Valadares, Chizzotti and Tedeschi2008) so that the protein requirements for maintenance can be met (NRC 2001). There is little information on the excretion of PD in hair sheep. Creatinine excretion was constant, regardless of sex class and level of feed restriction. Creatinine is formed in a non-enzymatic and irreversible process of removing water from phosphocreatine in the muscle tissue (Harper et al., Reference Harper, Rodwell and Mayes1982).

Owing to its constant production and proportionality to the BW of an animal, creatinine is used to estimate the urinary excretion of ruminant animals in individual samples (David et al., Reference David, Poli, Savian, Amaral, Azevedo and Jochims2015). Sheep subjected to dietary restriction decrease their DM intake and, consequently, there is a decreased flow of microbial nucleic acids into their intestines. This change is evidenced by reduced excretion of total PD, uric acid and allantoin, the largest single component of PD excreted in the urine. The excretion of allantoin for each sex class was 0.84, reflecting the complete excretion of PD, which was found to occur in a higher proportion of approximately 0.85 (Verbic et al., Reference Verbic, Chen, MacLeod and Ørskov1990). Hypoxanthine, xanthine and uric acid are excreted through urine with a high renal clearance rate constant of approximately 0.33/h in sheep (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ørskov, Hovell, Eggum, Boisen, Bsrsting, Danfter and Hvelplund1991) and cattle (Giesecke et al., Reference Giesecke, Balsliemke, Südekum and Stangassinger1993). In ruminant animals, most of the purine flowing into the small intestine is of microbial origin and absorbed exogenous purines are excreted into urine after the salvage pathways reach saturation. Excretion and CPmic production are proportional to DM intake, having strong correlations with the flow of microbial nitrogen compounds into the duodenum. However, the decreased rate of passage is attributed to low feed intake, which causes an increase in the use of nutrients, as demonstrated by increased nutrient digestibility. Thus, minor losses of nitrogen and maximizing synchronization between dietary protein and carbohydrates in the rumen can result in improved efficiency of the use of microbial protein, as can be observed in animals subjected to 600 g/kg DM feed restriction. Microbial efficiency can be represented by the production of microbial cells (number or weight) synthesized by the substrate unit used. For the nutritional requirements of ruminant systems, microbial efficiency can be expressed as a function of TDN (NRC 2001, 2007), fermentable metabolizable energy (AFRC 1993) or the availability of carbohydrates in the rumen.

In tropical or semi-arid conditions, fibrous carbohydrates are the main source of energy in the rumen, and the grasses of these regions have average or low levels of protein; the availability of N in the rumen may be the main factor limiting microbial growth in this compartment. The average MPS was estimated at 53.1 g/kg of TDN, but less than the mean value of 76.2 g CPmic per kg of TDN was obtained in studies with sheep and goats in tropical regions receiving control diets (Fonseca et al., Reference Fonseca, Valadares, Valadares Filho, Leão, Cecon, Rodrigues, Pina, Marcondes, Paixão and Araújo2006; Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Garcia, Pires, Silva, Pereira, Viana, dos Santos and Pereira2010; Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Pereira, Arruda, Cabral, Oliveira, Mizubuti, Pinto, Campos, Gadelha and Carneiro2016).

Animals undergoing long periods of food shortage alter their physiological processes, becoming more adapted to the hot climate, changing their typical ingestive behaviour and the use of ingested nutrients while decreasing their energy expenditure for maintenance to ensure thermoregulation. Moreover, in high-temperature environments, productivity is compromised, given that feed intake is reduced and is usually correlated positively with heat production in fasting. Thus, animals that are acclimated to heat alter their physiological processes in order to reduce heat production (Starling et al., Reference Starling, da Silva, Negrão, Maia and Bueno2005). The surface temperatures found in the current study demonstrated that dietary restriction minimizes heat loss through the skin of the animal. Obviously, this result occurred because the animals maximized the use of nutrients in their bodies, generating less body heat through metabolic processes (Kleiber, Reference Kleiber1975). The physiological parameters of ruminants are directly influenced by climatic factors such as temperature, RH and solar radiation (Furtado et al., Reference Furtado, Peixoto, Regis, Nascimento, Araújo and Lisboa2012). Typically, an increase in the ambient temperature is accompanied by an increase in the RT of the animal, requiring additional effort to ensure thermoregulation. Despite the differences found in the current study, the RT values remained within the range of physiological values suggested by Marek and Mócsy (Reference Marek and Mócsy1973) in young animals up to 1 year old (38.5–40.5 °C). These results demonstrated the adaptability of hair sheep to the tropical climate even under critical stress conditions in the afternoon, as demonstrated by the THI (80.48). Males and females at 600 g/kg/DM feed restriction had decreased values for body temperature on the right side. However, for the left side and the front aspect of the chest, a similar finding was recorded in all animals restricted to 600 g/kg/DM feed. The lower feed intake resulted in less time spent on feeding behaviour and rumination, reducing the number of calories expended through those activities. According to Lachica and Aguilera (Reference Lachica and Aguilera2005) and Cannas et al. (Reference Cannas, Van Soest and Pell2003), the time spent on feeding activities can increase animal heat production by 10–26%, resulting in higher energy costs. The variation in body temperature was greatest on the left side of the animals owing to the topographic location of the stomachs, which, according to Ørskov and Ryle (Reference Ørskov and Ryle1990), make this region of the body a window to the temperature variations within.

Infrared thermography (IRT) is an important non-invasive tool that measures the surface temperature of an animal and identifies many physiological and pathological processes related to changes in body temperature (Montanholi et al., Reference Montanholi, Odongo, Swanson, Schenkel, McBride and Miller2008; Church et al., Reference Church, Hegadoren, Paetkau, Miller, Regeve-Shoshani, Schaefer and Schwartzkopf-Genswein2014). Another factor that influences the variation of body surface temperature is the environmental temperature, which affects the skin surface temperature and heat exchange between the organism and environment (Collier et al., Reference Collier, Dahl and VanBaale2006). The animals with the lowest surface temperatures on the left and right sides were those subjected to 600 g/kg/DM feed restriction. These results show that the feed restriction minimizes heat loss through the animal's skin. Less heat loss occurs because the animal maximizes the use of nutrients by the body, causing less heat to be released during endogenous reactions (Kleiber, Reference Kleiber1975). In addition, lower feed intake resulted in less time spent on feeding and rumination activities, reducing the expenditure of calories on ingestive behaviour. According to McManus et al. (Reference McManus, Tanure, Peripolli, Seixas, Fischer, Gabbi, Menegassi, Stumpf, Kolling, Dias and Costa Junior2016), animals that have lower body surface temperatures are more efficient animals.

Conclusion

Feed restriction reduces the time spent on feeding and rumination but on the other hand improves the digestibility of nutrients, balance of nitrogen compounds and the 600 g/kg/DM level maximizes the efficiency of microbial synthesis, while the gender factor influence only the NB. In addition, IRT indicated that males and females subjected to 600 g/kg/DM feed restriction have increased heat tolerance coefficients.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq-Brazil), by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES-Brazil).

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The current study was conducted at the Department of Animal Science at the Federal University of Ceara in strict accordance with the recommendations of the Guide for the Care and Use of Agricultural Animals in Research and Teaching and was approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the Federal University of Ceara, Ceara State, Brazil. This research was submitted to and approved by the Research Ethics Committee on Animals (CEUA) according to its guidelines (UFC – protocol number 98/2015).

Author ORCIDs

R. L. Oliveira 0000-0001-5887-4753.