INTRODUCTION

Triplet-born lambs are lighter at birth, and during the first 24 h of life they have lower plasma concentrations of thyroid hormones and lower rectal temperatures than twin- or single-born lambs (Cabello & Levieux Reference Cabello and Levieux1981; Barlow et al. Reference Barlow, Gardiner, Angus, Gilmour, Mellor, Cuthbertson, Newlands and Thompson1987; Stafford et al. Reference Stafford, Kenyon, Morris and West2007). Newborn lambs with lighter birth weights or lower rectal temperatures display reduced vigour (Dwyer Reference Dwyer2003; Dwyer & Morgan Reference Dwyer and Morgan2006) and less of a drive to suckle (Alexander & Williams Reference Alexander and Williams1966), making them more susceptible to hypothermia (Dalton et al. Reference Dalton, Knight and Johnson1980). This may explain why triplet-born lambs have a lower survival rate than twin- or single-born lambs (Morris & Kenyon Reference Morris and Kenyon2004; Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Muir and Smith2004; Kerslake et al. Reference Kerslake, Everett-Hincks and Campbell2005; Everett-Hincks & Dodds Reference Everett-Hincks and Dodds2008).

Thyroid hormones have been shown to play a critical role in the initiation of independent thermoregulation and maintenance of body temperature after birth (Symonds et al. Reference Symonds, Bird, Clarke, Gate and Lomax1995). Newborn lambs with greater plasma concentrations of thyroid hormones appear to be better at producing heat (Alexander Reference Alexander and Phillipson1970) and maintaining core body temperature when subjected to cold stress (Caple & Nugent Reference Caple and Nugent1982; Polk et al. Reference Polk, Callegari, Newnham, Padbury, Reviczky, Fisher and Klein1987). Thyroid hormone production is reliant on the thyroid gland absorbing iodine from the blood (Underwood & Suttle Reference Underwood and Suttle1999). Iodine is actively transported across the placenta to the developing fetus, where from day 50 of pregnancy the fetus synthesizes its own thyroid hormones from maternal iodine (Potter et al. Reference Potter, Mcintosh, Mano, Baghurst, Chavadej, Hua, Cragg and Hetzel1986). Lambs born from ewes supplemented with iodine have greater thyroxine concentrations at birth (Andrewartha et al. Reference Andrewartha, Caple, Davies and Mcdonald1980) and at 24 h of age (Rose et al. Reference Rose, Wolf and Haresign2007) when compared with lambs born to non-supplemented ewes. They have also been reported as having greater rectal temperatures after birth (Donald et al. Reference Donald, Langlands, Bowles and Smith1994). Increasing maternal plasma iodine concentration during pregnancy could therefore increase the thyroid hormone production in the fetus and/or newborn lamb and thus improve newborn lamb heat production. This experiment investigates the effect of maternal iodine supplementation on twin- and triplet-born lamb plasma thyroid hormone concentrations, rectal temperature and their ability to produce heat within 24–36 h after birth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This experiment was conducted at Massey University Keeble Farm, Palmerston North, New Zealand (40°24′S, 175°36′E, 44 m asl) from 8 February 2006 until 17 September 2006. The experiment was a 2×2 factorial design, which included two litter sizes (twin- and triplet-bearing ewes) and two iodine supplementation treatments (supplemented and non-supplemented). A sheep fertility-enhancing vaccine (Androvax®, AgVax, Upper Hutt, New Zealand) was given to 1150 mixed aged Romney cross ewes 63 and 35 days prior to the start of mating (13 April 2006). Half of the ewes (n=575) were injected intramuscularly in the anterior half of the neck with 1·5 ml/ewe of iodized peanut oil (Flexidine® (26% w/w of iodine bound to ethyl esters of unsaturated fatty acids in oil), Bomac Laboratories Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand) 35 days prior to the start of mating. Romney rams (n=10) fitted with crayon mating harnesses joined the ewes for a 10-day breeding period. Ewes with a crayon-marked rump were pregnancy diagnosed using ultrasound scanning at 64 days (P64) after the mid-point of the breeding period (18 April 2006). Non-pregnant, single-, twin- and triplet-bearing ewes were marked for future identification. All of the ewes remained in one flock on ad libitum pasture from the beginning of mating until P68. At P68, 16 twin- and 14 triplet-bearing ewes were randomly selected from each supplemented and non-supplemented treatment group. These ewes were removed from the main flock and were grazed together on ad libitum pasture until parturition.

At P145, the selected twin- and triplet-bearing ewes were moved into a 2·5 ha paddock and supervised continually for the next 10 days. Twenty-five twin-bearing ewes (supplemented, n=13; and non-supplemented, n=12) and 22 triplet-bearing ewes (supplemented, n=12; and non-supplemented, n=10) that showed signs of parturition were moved quietly to small individual pens (5×3 m) located in the paddock. The ewes remained in these pens during parturition. Measurements and samples were taken from lambs within 5 min of birth and until 24–36 h of age (described later). All ewes had access to herbage and water within the pens and were released from the pen 24 h after the last lamb was born.

The intensive lambing observations and measurement were undertaken from 6 to 16 September 2006. During this period, the weather conditions consisted of an average wind speed of 3·87 m/s, total rainfall of 0·01 mm, an average temperature of 10·3°C (max.=12·3°C, min.=7·25°C), and an average wind chill of 997·1 kJ/m2/h.

The Massey University Animal Ethics Committee approved the trial.

Ewe measurements

Unfasted ewe live weight and body condition score (scale 1–5, half units (Jefferies Reference Jefferies1961)) were measured at mating, P68, P100, P120 and P141. A 10 ml blood sample was also collected by jugular venepuncture (lithium heparin, Becton Dickson Vacutainer Systems, USA) from a sub-sample of the ewes (supplemented, n=12; and non-supplemented, n=14) on P100, P120 and P141.

Lamb measurements

The lambs were tagged and their birth rank and birth order were recorded within the first 5 min of birth. At the same time, two 5 ml blood samples were collected from each lamb by jugular venepuncture (lithium heparin and potassium oxalate vacutainer, Becton Dickson Vacutainer Systems, USA). Rectal temperature was also measured within the first 5 min of birth and this measurement was repeated at 1, 3, 6 and 12 h after birth. If the rectal temperature of a lamb fell below 36°C (Alexander Reference Alexander1962 b), no further measurements were taken and the lamb was removed from the experiment. At 3 h after birth each lamb was weighed, its sex determined and crown–rump length and thoracic-girth circumference were measured. Additional 5 ml blood samples were collected from each lamb by jugular venepuncture (lithium heparin vacutainer, Becton Dickson Vacutainer Systems, USA) at 3, 12 and 24 h after birth.

At 24–36 h of age, 28 twin-born lambs (supplemented, n=14; non-supplemented, n=14) and 30 triplet-born lambs (supplemented, n=17; non-supplemented, n=13) were randomly selected to determine their maximal heat production (summit metabolism) by indirect open-circuit calorimetry. The average cold stress index (CSI) within the first 24–36 h of life was calculated using the following equation (Donnelly Reference Donnelly1984):

where W is the mean wind speed (m/s), T is the mean temperature (°C), and R is the mean rainfall (mm).

A 10 ml blood sample was taken from the lamb via jugular venepuncture (lithium heparin, Becton Dickson Vacutainer Systems, USA) immediately prior to the lamb being placed in a crate within an indirect open-circuit calorimeter (McCutcheon et al. Reference McCutcheon, Holmes, Mcdonald and Rae1983). The lamb's head was placed in a plastic hood, which was sealed around the neck with a collar. Air was drawn into and from the hood for measurement of oxygen consumption. A temperature probe was inserted in the rectum of the lamb to record body temperature. The lamb was exposed to an environmental temperature that ranged from 6 to 8°C and was allowed to acclimatize to these conditions for a total of 12 min. This period of time is referred to as the adjustment period. During this time, rectal temperature and oxygen consumption measurements were recorded over three successive 4-min periods to obtain a stabilized metabolic rate so that a base heat production level could be calculated. At the end of 12 min, lambs were exposed to wet and windy conditions to induce maximal heat production (summit metabolism). This period of time is referred to as the onset of severe cold stress. Artificial chilled rain (1°C) was applied from the 12 min mark through sprinklers at a standardized rate of (1·08 litres/min) and cold air was passed over the lamb by a fan positioned behind the animal at a rate of 1·0 m/s. After 20 min cold air was passed over the lamb at a rate of 1·5 m/s and after another 20 min at a rate of 2·0 m/s. The rate of cold air then stayed constant for the remaining period of time. Rectal temperature and oxygen consumption measurements were taken at 4 min intervals for 88 min or until the lamb reached maximal heat production, whichever occurred first. Maximal heat production was assumed to have been met when the rectal temperature of the lamb declined at the rate of 1°C/20 min and there was no further increase in the consumption rate of oxygen (Alexander Reference Alexander1962 b). To facilitate heat loss and stimulate heat production to its maximum, all lambs with a birth weight above 4 kg had the wool clipped from their back and sides, leaving a wool depth of 3 mm. Maximal heat production was calculated from oxygen consumption using the following formula (Revell et al. Reference Revell, Morris, Cottam, Hanna, Thomas, Brown and McCutcheon2002):

where it was assumed that 20·46 kJ of heat is produced per litre of oxygen consumed (McLean Reference McLean1972). Dividing oxygen consumption by a constant of 3·6 converts kJ/h to W.

After the lamb reached its maximum heat production, or after 88 min had elapsed in the calorimeter, the lamb was removed from the calorimeter, thoroughly dried, and a 5 ml blood sample was taken via jugular venepuncture (lithium heparin, Becton Dickson Vacutainer Systems, USA). Thereafter, the lambs were placed in a heated room for 1 h before being returned to their dams.

Plasma analysis

All blood samples were stored on ice until they were centrifuged at 1000 g for 15 min. The plasma was removed and frozen at −20°C. A random sample of ewe (8 twin- and 7 triplet-bearing ewes from non-supplemented treatment, and 7 twin- and 7 triplet-bearing ewes from supplemented treatment) and lamb blood samples (14 twin- and 13 triplet-born lambs born to non-supplemented ewes and 14 twin- and 17 triplet-born lambs born to supplemented ewes) were analysed. Ewe plasma samples were analysed using a diagnostic kit for iodine (tetramethylammonium hydroxide micro (TMAH) digestion, 90°C for 1 h, filtration (Fecher et al. Reference Fecher, Goldman and Nagengast1998; Hill Laboratories, Hamilton, New Zealand)). Lamb plasma samples were analysed using diagnostic kits for glucose (the hexokinase method, Roche Diagnostics Ltd, Switzerland), non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA) (Sigma, Illinois, USA), total thyroxine (T4) and total tri-iodothyronine (T3) (radioimmunoassay diagnostic kit, Coat-A-Count, Diagnostic Products Corporation, CA, USA), gamma-glutamyl-transferase (GGT) (Roche kit, Roche Diagnostics Ltd, Switzerland), and immunoglobulin G (IgG) (standard direct ELISA assay).

Statistical analysis

The dataset for metabolite and hormone concentrations and rectal temperatures contained some missing values due to the following reasons: (i) if the lamb was dead at birth, blood samples and rectal temperatures were not measured, (ii) blood samples that were not obtained after two attempts were not collected, (iii) blood samples and rectal temperatures that were not taken within 10 min of the required time were not included in the analyses and (iv) if the rectal temperature of a lamb fell below 36°C during the observation periods, no further measurements were taken and the lamb was removed from the remainder of the study.

All ewe measurements that were taken over time (plasma iodine concentrations (P68, P120 and P141), ewe live weight (P50, P100, P120 and P141) and ewe body condition score (P100, P120 and P141)) were analysed using a repeated measure (PROC GLM) analysis. These models contained the fixed effects of ewe iodine supplementation (non-supplemented and supplemented) and litter size (twin- and triplet-bearing), plus their interactions. Non-significant (P>0·05) interactions were removed from the general linear model. Lamb plasma T4 and T3 concentrations that were taken over time (within 5 min of birth, at 3 h of age and at 24–36 h of age) were also analysed using a repeated measure (PROC GLM) analysis. These models contained the fixed effect of ewe iodine supplementation (non-supplemented and supplemented) and birth rank (twin- and triplet-born), plus their interactions. After running the model, the model was re-run with lamb birth weight as a covariate. The interactions or covariate only remained in the general linear model if significant (P<0·05).

Lamb physical measurements (live weight, crown–rump length and thoracic-girth circumference), lamb plasma glucose, GGT and IgG concentrations at 24–36 h of age, and lamb plasma glucose and NEFA concentration before and after the onset of calorimetry were analysed using a general liner model (PROC GLM). These models contained the fixed effects of ewe iodine supplementation (non-supplemented and supplemented), lamb birth rank (twin- and triplet-born) and lamb sex (male and female), plus their interactions. After these models were run, the model was re-run with lamb birth weight as a covariate. The interactions or covariate only remained in the general linear model if significant (P<0·05).

Plasma NEFA concentrations before and after the onset of calorimetry were not normally distributed. To achieve a normal distribution the concentrations were log10 transformed. Lamb rectal temperatures measured within 5 min of birth and at 3 and 12 h of age, were not normally distributed. Log, squared, cubed and square-root transformations were unable to normalize the data. Lamb rectal temperatures from birth until 12 h of age were therefore presented as median and interquartile ranges. The non-parametric test of Kuskal–Wallis was used to determine the significance of ewe iodine supplementation (non-supplemented and supplemented) and lamb birth rank (twin- and triplet-born) on lamb rectal temperatures.

The base heat production and maximal heat production (in units of W), the base heat production and maximal heat production on a per kg of live weight basis (W/kg), and the rate to reach maximal heat production (W/kg/min) were analysed using a general linear model (PROC GLM; SAS, 2003). The model contained the fixed effects of the calorimeter machine (one and two), iodine supplementation (non-supplemented and supplemented), birth rank (twin- and triplet-born), sex (male and female), plus their interactions. Plasma GGT concentrations at 24–36 h of age and average CSI within the first 24 h of life were fitted as covariates. After these models were run, the models were re-run with lamb birth weight as a covariate. Interactions and covariates were retained in the model if significant at P<0·05. If not significant they were removed and the model was refitted.

The proportion of lambs reaching maximal heat production were analysed as a binomial trait using the SAS procedure for categorical modelling (PROC GENMOD). Data were analysed as logit transformed values and presented in the results as back-transformed percentages. The model contained the fixed effects of ewe iodine supplementation (non-supplement and supplement) and birth rank (twin- and triplet-born), plus their interactions.

RESULTS

Ewe plasma iodine concentrations

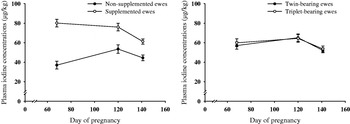

Ewes that were supplemented with iodine had greater (P<0·001) plasma iodine concentrations at P68, P120 and P141 than ewes that were not supplemented (Fig. 1). While plasma iodine concentrations of supplemented ewes did not differ (P>0·05) between P68 and P120, they decreased (P<0·01) from P120 until P141. In contrast, the plasma iodine concentrations of non-supplemented ewes increased (P<0·01) from P68 to P120, but did not differ at P140 (P<0·05) from P68 or P120.

Fig. 1. Effect of iodine supplementation (non-supplemented and supplemented (n=15 and 15, respectively)) and litter size (twin- and triplet-bearing (n=16 and 14, respectively)) on ewe plasma iodine concentrations on pregnancy day 68 (P68), P120 and P141 (mean±s.e.).

Litter size had no effect on ewe plasma iodine concentrations. While plasma iodine concentrations of twin- and triplet-bearing ewes did not differ (P>0·05) between P68 and P120, they did decrease (P<0·01) from P120 and P141.

Ewe live weight and body condition score during pregnancy

Ewe iodine supplementation and litter size had no effect (P>0·05) on ewe live weight (kg) at P50, P100, P120 and P141 (pooled means±s.e., 60·5±0·70, 72·5±0·83, 76·1±0·87 and 84·5±1·15, respectively), or on ewe body condition score at P100, P120 and P141 (pooled means±s.e., 3·1±0·07, 3·1±0·05 and 3·1±0·04).

Lamb body size measurements

Ewe iodine supplementation had no effect (P>0·05) on lamb birth weight, crown–rump length or thoracic-girth circumference (Table 1). Triplet-born lambs were lighter than twin-born lambs and had a smaller thoracic-girth circumference (P<0·001). Differences in thoracic-girth circumferences, however, were explained by lamb birth weight. For every 1 kg increase in lamb birth weight, crown–rump length and thoracic-girth circumference increased by 22·6±6·35 and 25·0±3·18 mm, respectively.

Table 1. The effect of iodine supplementation (non-supplemented and supplemented) and lamb birth rank (twin- and triplet-born) on lamb birth weight, crown–rump length and thoracic-girth circumference (mean±s.e.)

Lamb core body temperature after birth

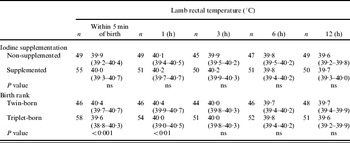

Ewe iodine supplementation had no effect (P>0·05) on lamb rectal temperature within 5 min of birth or at 1, 3, 6 and 12 h of age (Table 2). Triplet-born lambs had lower (P<0·01) rectal temperatures within 5 min of birth and at 1 h of age, compared with twin-born lambs. Lamb birth rank had no effect on lamb rectal temperatures at 3, 6 and 12 h of age.

Table 2. The effect of iodine supplementation (non-supplemented and supplemented) and birth rank (twin- and triplet-born) on lamb rectal temperature within 5 min of birth and at 1, 3, 6 and 12 h of age (median (interquartile range))

Significance was determined by the Kruskal–Wallis test.

Lamb plasma glucose, GGT and IgG concentrations

Triplet-lambs born to iodine-supplemented ewes had greater glucose and IgG concentrations at 24–36 h of age than triplet-born lambs born to non-supplemented ewes (P<0·01; Table 3). This relationship was not observed in twin-born lambs (P>0·10). Within the iodine-supplemented treatment group, triplet-born lambs tended to have a greater IgG concentration than twin-born lambs (P=0·07). Within the non-supplemented treatment group, twin-born lambs had a greater glucose concentration than triplet-born lambs (P<0·05). Ewe iodine supplementation and lamb birth rank had no effect on plasma GGT concentrations at 24–36 h of age (P>0·1).

Table 3. The effect of iodine supplementation (non-supplemented and supplemented) and lamb birth rank (twin- and triplet-born) on lamb plasma glucose, gamma-glutyl-transferase (GGT) and immunoglobulin G (IgG) concentrations at 24–36 h of age (mean±s.e.)

Lamb plasma thyroid hormone concentrations

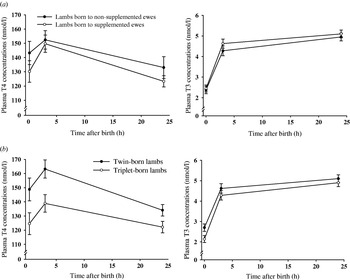

Ewe iodine supplementation had no effect (P>0·05) on newborn lamb plasma T4 and T3 concentrations within 5 min of birth and at 3 and 24–36 h of age (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2. (a) Effect of iodine supplementation (non-supplemented and supplemented (n=25 and 29, respectively)) on lamb plasma thyroxine (T4) and tri-iodothyronine (T3) concentrations within 5 min of birth and at 3 and 24–36 h of age (mean±s.e.). (b) Effect of lamb birth rank (twin- and triplet-born (n=25 and 29, respectively)) on lamb plasma thyroxine (T4) and plasma tri-iodothyronine (T3) concentrations within 5 min of birth and at 3 and 24–36 h of age (mean±s.e.).

Over time, plasma T4 concentrations of lambs born to non-supplemented ewes did not differ (P>0·05) between birth and 3 h of age but did decrease (P<0·05) from 3 to 24 h of age. Plasma T4 concentrations of lambs born to supplemented ewes increased (P<0·05) from birth until 3 h of age, but then decreased (P<0·01) from 3 to 24 h of age. Plasma T3 concentrations of lambs born to both non-supplemented and supplemented ewes increased (P<0·001) from birth until 3 h of age. From 3 to 24 h of age, plasma T3 concentrations increased (P<0·05) for lambs born to non-supplemented ewes, and stayed the same (P>0·05) for lambs born to supplemented ewes.

Twin-born lambs had greater (P<0·05) plasma T4 concentrations within 5 min of birth and at 3 and 24 h of age than triplet-born lambs (Fig. 2b). After adjustment for lamb birth weight, however, lamb birth rank had no effect on plasma T4 concentrations. For every 1 kg increase in lamb birth weight, plasma T4 concentrations increased by 10·9±3·31 nmol/l. Twin-born lambs had greater plasma T3 concentrations than triplet-born lambs within 5 min of birth (P<0·05). Lamb birth rank had no effect (P>0·05) on plasma T3 concentrations at 3 and 24 h of age. Lamb birth weight had no effect (P>0·05) on plasma T3 concentrations.

Over time, plasma T4 concentrations of twin- and triplet-born lambs did not differ (P>0·05) between birth and 3 h of age, but did decrease (P<0·05) from 3 to 24 h of age. Plasma T3 concentrations of twin- and triplet-born lambs increased (P<0·05) from birth until 3 h of age. From 3 to 24 h of age, plasma T3 concentrations did not differ (P>0·05) for twin-born lambs, but increased for triplet-born lambs. Ewe iodine supplementation and lamb birth rank had no effect (P>0·05) on plasma T3:T4 ratio within 5 min of birth, at 3 h of age or at 24–36 h of age (data not shown).

Base heat production, maximal heat production and rate to reach maximal heat production

Iodine supplementation had a positive effect on the base heat production on a per lamb basis (W/lamb) and had no effect on the maximum heat production on a per lamb basis (Table 4). Triplet-born lambs tended to (P=0·08) have a lower base heat production on a per lamb basis and had (P<0·01) a lower maximal heat production on a per lamb basis than twin-born lambs. A one unit increase in plasma GGT concentration was associated (P<0·01) with an increase in the maximal heat production on a per lamb basis, at a rate of 0·01 (s.e.±0·002) W. After adjustment for lamb birth weight, lamb birth rank no longer had an effect on the base and maximal heat production on a per lamb basis. For every 1 kg increase in lamb birth weight, the base and maximal heat production on a per lamb basis increased by 6·46 (s.e.±2·04) W and 10·5 (s.e.±3·49) W, respectively.

Table 4. The effect of iodine supplementation (non-supplemented and supplemented) and birth rank (twin- and triplet-born) on lamb base heat production (W and W/kg), maximal heat production (W and W/kg) and the rate to reach maximal heat production at 24–36 h of age (mean±s.e.)

Newborn lambs born to iodine-supplemented ewes had a greater base heat production on a per kg of live weight basis (W/kg) than lambs born to non-supplemented ewes (P<0·05; Table 4). Iodine supplementation did not affect maximal heat production on a per kg of live weight basis, or the rate to reach maximal heat production (W/kg/min). The base heat production on a per kg of live weight basis tended (P=0·08) to be greater in triplet-born lambs than twin-born lambs. Neither maximal heat production on a per kg of live weight basis or the rate to reach maximal heat production differed (P>0·05) between twin- and triplet-born lambs. A one unit increase in plasma GGT concentration was found to be associated (P<0·01) with an increase in the maximal heat production on a per kg of live weight basis at a rate of 0·01 (±0·003 (s.e.)) W/kg. Lamb weight had no effect on the base and maximal heat production on a per kg of live weight basis.

The proportion of lambs to reach maximal heat production during calorimetry

Ewe iodine supplementation and lamb birth rank had no effect (P>0·05) on the proportion of lambs reaching maximal heat production during 88 min of cold stress (0·93, 0·85, 0·89 and 0·90 for supplemented, non-supplemented, twin-born and triplet-born lambs, respectively).

Plasma glucose and NEFA concentrations before and after calorimetry

Lambs born to iodine-supplemented ewes had greater plasma glucose concentrations after calorimetry than lambs born to non-supplemented ewes (9·4±0·40 and 8·3±0·40 mmol/l, respectively; P<0·05). Lamb birth rank had no effect (P>0·05) on lamb plasma glucose concentrations before or after calorimetry, or on the change in the concentration of glucose from before calorimetry until after calorimetry. Iodine supplementation and lamb birth rank had no effect (P>0·05) on plasma NEFA concentrations before or after calorimetry, or on the change in the concentration of NEFA from before calorimetry until after calorimetry (1·0±0·09 (pooled mean±s.e.), 1·3±0·12 and 0·3±0·16 mmol/l, respectively).

Correlations between lamb birth weight, thyroid hormones, plasma metabolites and maximal heat production on a per lamb and per kg of live weight basis

Lamb birth weight, plasma T4 concentrations within 5 min of birth, plasma T3 concentrations at 3 and 24–36 h of age, plasma GGT concentrations at 24–36 h of age, and plasma glucose concentrations before calorimetry were positively (P<0·05) correlated with maximal heat production on a per lamb basis (Table 5).

Table 5. Correlations between lamb birth weight, thyroid hormones, plasma metabolites and maximal heat production on a per lamb basis and a per kg of live weight basis

*** P<0·001; **P<0·01; *P<0·05.

Lamb plasma T3 concentrations at 24–36 h of age, plasma GGT concentrations at 24–36 h of age and plasma glucose and NEFA concentrations before calorimetry were positively correlated (P<0·05) with maximal heat production on a per kg of live weight basis.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the present study was to determine if maternal iodine supplementation had a positive effect on twin- and triplet-born lamb thyroid hormone concentrations, rectal temperature and heat production 24–36 h post-birth. Based on the serum iodine status of newborn calves and the thyroid-weight:birth weight ratio of newborn lambs, McCoy et al. (Reference McCoy, Smyth, Ellis, Arthur and Kennedy1997) and Knowles & Grace (Reference Knowles and Grace2007) suggested that maternal plasma iodine concentrations of approximately 40 μg/l, which are similar to the maternal plasma iodine concentrations of the non-supplemented treatment group in the present study, were inadequate. Maternal iodine concentrations of 65 g/l, which are similar to the maternal plasma iodine concentrations of the supplemented treatment group, are considered adequate.

Positive associations between maternal iodine plasma concentrations and thyroid hormone concentrations of the newborn lamb (Andrewartha et al. Reference Andrewartha, Caple, Davies and Mcdonald1980; Rose et al. Reference Rose, Wolf and Haresign2007) and between thyroid hormone concentrations of the newborn lamb and its thermoregulation have been reported previously (Alexander Reference Alexander and Phillipson1970; Caple & Nugent Reference Caple and Nugent1982; Polk et al. Reference Polk, Callegari, Newnham, Padbury, Reviczky, Fisher and Klein1987; Symonds et al. Reference Symonds, Bird, Clarke, Gate and Lomax1995). In the present study, however, maternal iodine supplementation had no effect on the thyroid hormone concentration of the lamb from birth to 24 or 36 h of age, core body temperature from birth to 12 h of age, or the maximal amount of heat produced at 24–36 h of age on a W/lamb or W/kg basis. Given that previous studies have reported a positive association between maternal iodine supplementation and plasma T4 concentrations (Andrewartha et al. Reference Andrewartha, Caple, Davies and Mcdonald1980; Rose et al. Reference Rose, Wolf and Haresign2007), and given that maternal iodine concentrations were different between treatment groups, it is also unclear why differences in lamb plasma thyroid concentrations were not observed. Lamb plasma T3 concentrations at 24–36 h of both twin- and triplet-born lambs were both found to be positively correlated with maximal heat production on a W/lamb basis and a W/kg of live weight basis. The inability of maternal iodine supplementation to alter lamb plasma thyroid concentrations may therefore explain the lack of differences between treatment groups for lamb heat production. This finding also supports previous reports (Alexander Reference Alexander and Phillipson1970; Caple & Nugent Reference Caple and Nugent1982; Polk et al. Reference Polk, Callegari, Newnham, Padbury, Reviczky, Fisher and Klein1987; Symonds et al. Reference Symonds, Bird, Clarke, Gate and Lomax1995), which indicate that manipulation of thyroid hormones should improve lamb heat production. In support of previous studies (Alexander Reference Alexander1962 a; Dwyer & Morgan Reference Dwyer and Morgan2006; Stafford et al. Reference Stafford, Kenyon, Morris and West2007), triplet-born lamb birth weights were lighter than twin-born lamb birth weights, and triplet-born lamb plasma T4 and T3 concentrations after birth and rectal temperatures within 5 min of birth and at 1 h of age were lower than twin-born lambs. These results, combined with the positive correlation between plasma T4 concentrations within 5 min of birth and maximal heat production on a W/lamb basis, suggest that triplet-born lambs may be more susceptible to a hypothermic death during periods of cold stress than twin-born lambs.

Maternal iodine supplementation had a positive effect on the plasma IgG concentrations of triplet-born lambs at 24–36 h of age, which, in the present study, were used as an indicator of colostrum intake (Maden et al. Reference Maden, Altunok, Birdane, Aslan and Nizamlioglu2003; Kenyon et al. Reference Kenyon, Stafford, Morel and Morris2005). Maternal iodine supplementation has been previously been reported as having a positive effect on the production of milk (Odjakova Reference Odjakova1999; Angelow et al. Reference Angelow, Petrova and Makaveeva2004), which in turn may have a positive effect on the intake of colostrum by the lamb and therefore its survival. Caution needs to be taken here however, as (i) these positive effects were only seen in triplet-born lambs and not twin-born lambs; (ii) IgG uptake is not only influenced by colostrum intake, but also by the amount of IgG in the milk and the efficiency of colostrum absorption (Boland et al. Reference Boland, Brophy, Callan, Quinn, Nowakowski and Crosby2004; Boland et al. Reference Boland, Brophy, Callan, Quinn, Nowakowski and Crosby2005), neither of which were measured in the current experiment; and (iii) recent research has clearly shown that increasing the level of iodine in the diet of ewes in late pregnancy is associated with reduced immunoglobulin uptake (Boland et al. Reference Boland, Brophy, Callan, Quinn, Nowakowski and Crosby2004; Boland et al. Reference Boland, Brophy, Callan, Quinn, Nowakowski and Crosby2005; Rose et al. Reference Rose, Wolf and Haresign2007) not increased uptake. One of the differences between the present study and the multitude of studies that have shown a reduction in IgG uptake lies in the mode of iodine delivery. Because IgG uptake is important for diseases resistance in early life, the effect of different modes of iodine administration and the effects this may have on the colostrum uptake of the lamb merit further investigation.

CONCLUSIONS

Under the conditions of the present study, maternal iodine supplementation had no effect on twin- and triplet-born lamb thyroid hormone production, core body temperature and maximal heat production. Maternal iodine supplementation did, however, have a positive effect on plasma IgG concentrations in triplet-born lambs, which may indicate an increase in colostrum intake. Independent of maternal iodine treatment, plasma T3 concentrations were found to be positively correlated with maximal heat production on a per lamb basis and on a per kg of live weight basis. This indicates that if maternal iodine supplementation had been successful in increasing plasma T3 concentrations, twin- and triplet-born lamb heat production may have been improved. Overall, triplet-born lambs were found to be lighter and to have lower rectal temperatures and lower plasma T4 and T3 concentrations than twin-born lambs.

The authors thank Meat and Wool New Zealand for financial support of this research programme and the National Centre for Growth and Development and Massey University for financial support of the first author's work. The authors also thank Dr K. A. Goodwin and Dr A. J. Wall for their technical support.