INTRODUCTION

This article investigates the impact of public law judgments on private rights in the context of maritime delimitation. The main purpose of judicial delimitation is the peaceful settlement of interstate maritime disputes. By establishing maritime boundaries, international judges seek to separate the overlapping entitlements of two states in a shared maritime space, on the basis of international law and in an equitable manner.Footnote 1 In this light, maritime delimitation rests on the reduction of each state's jurisdiction in the ocean.

This raises questions as to whether a delimitation judgment may also disturb any private exploratory rights that already exist in the disputed area. The author's concerns emerge from the tendency of judges to disregard any non-geographical factors (such as the presence of natural resources or exploratory permits in the disputed area) during the process of maritime delimitation. In essence, this practice allows for the reallocation of the private rights in question and, eventually, creates tension between public international law and private law.

This tension is particularly evident in the Somali-Kenyan boundary dispute, which is currently before the International Court of Justice (ICJ). The presence of private permits granted by Kenya for the exploration of the contested maritime area makes this case worth studying. Hence, it will be interesting to investigate the ICJ's potential stance towards existing private rights.

This article will demonstrate that, insofar as the ICJ aligns with the standard doctrines of maritime delimitation, the prospective judgment may cause the reallocation and, ultimately, the discharge of Kenya's privately-held permits in the disputed area. The key to reversing this outcome is state cooperation; however, as this study observes, this practice is not without difficulties. Through the present analysis, the author challenges the current rules of maritime delimitation and the capacity of international fora to handle complex boundary disputes involving private rights. The author hopes this will encourage future discussion of the legal responses to this problem.

The article is in two parts. The first identifies the clash between public international law and private law in the context of judicial delimitation. After introducing some basic concepts of public international law (ocean enclosure, maritime disputes, delimitation), the article concentrates on the potential impact of international adjudication on private rights that already exist in a disputed area. Against this background, the author sets the research question: will an exploratory permit survive the potential reallocation of the explored area due to maritime delimitation?

The second part answers this question in the context of the Somali-Kenyan case study. After presenting the specifics of the boundary dispute, the article investigates the potential impact of the upcoming delimitation judgment on Kenya's privately-held contractual permits, and the possible ways to secure private rights under the auspices of international law.

THE CLASH BETWEEN PUBLIC INTERNATIONAL LAW AND PRIVATE LAW

From freedom of the seas to ocean enclosure

For centuries, the ocean has been the subject of a battle: the battle between mare liberum [freedom of the seas] and mare clausum [ocean enclosure - sea under the jurisdiction of one nation]. According to the former doctrine, introduced by Hugo Grotius in 1609, the sea as a whole was too immense to be appropriated by a nation. Despite its wide acceptance among the circles of natural law, the so-called “freedom of the seas” was challenged when John Selden first supported states’ rights to the world's seas and oceans.Footnote 2 The idea of state expansion in the ocean was quickly favoured by coastal nations. By the mid-20th century, mare clausum had successfully dominated international legal theory.

The prevalence of ocean enclosure in the mid-1900s can be attributed to three main reasons. First, the control of the seas would provide littoral states with access to offshore living and non-living resources. The world's increasing food and energy needs had long ago turned states’ interests to the ocean. Yet, it was not until the end of World War II that technological advancements enabled the search for and the utilization of natural resources at great depths.

Secondly, the mid-20th century is intertwined with the independence of many states in Africa, Latin America and Asia. The end of colonization marked the birth of new coastal states seeking economic development and participation in global trade. The key to progress was the declaration of permanent sovereignty over the natural wealth of those states, which encouraged foreign investment onshore and offshore.Footnote 3

Thirdly, the true catalyst for the expansion of states’ jurisdiction in the ocean was the development of a suitable legal framework. For centuries, a state's authority could not extend beyond three nautical miles from the shore, subject to the so-called “cannon shot” rule.Footnote 4 Yet, with the passage of time, states sought to expand their offshore jurisdiction.Footnote 5 In response, the Geneva Convention on the Continental Shelf of 1958 first established coastal states’ exploratory rights to the seabed within a distance of 200 nautical miles.Footnote 6 However, the expansion of state control in the ocean was completed with the implementation of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in 1982. Pursuant to this quasi-universal treaty, every littoral state is now entitled to a 12 nautical mile territorial sea, a 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone and a 200 nautical mile continental shelf which, in certain circumstances, can extend up to 350 nautical miles from the coast.Footnote 7

Overlapping entitlements and maritime delimitation

In an ideal world, all littoral states would be able to enjoy the full extent of their legal entitlements in the ocean. Alas, this picture is far from real. Whenever two (opposite or adjacent) states are proximate, their legitimate projections may abut or overlap. To separate their overlapping entitlements, states need to establish an international maritime boundary through the process of delimitation.Footnote 8

The basic function of delimitation is that it helps states define their offshore jurisdiction in a clear-cut way. By definition, boundaries are “lines that mark the limits of an area”Footnote 9 or, more correctly in this case, that mark the limits of the jurisdiction of the two states in a shared maritime space. That aside, boundaries serve a series of political, legal and administrative purposes too.Footnote 10 These purposes, which Johnston calls “state values”, can be classified in two main categories: symbolic values (states’ national defence and integrity, exercise of national jurisdiction and sovereignty, good neighbouring); and practical values (states’ economic welfare and self-sufficiency through the conduct of economic activities, such as farming, trade, tourism, fishing, exploitation of hydrocarbons and mineral deposits).Footnote 11 It must be pointed out, however, that “there is no rule that the … frontiers of a State must be fully delimited”.Footnote 12 This applies to both land and maritime boundaries.Footnote 13

Delimitation plays a problem-solving role too, for it settles international maritime disputes. Typically, these disputes arise from disagreement between two states regarding their boundary's exact location or the criteria to be applied for the establishment of the boundary.Footnote 14 That said, an international dispute is not a vague declaration of opposite assertions over the same area but a “specific and explicitly expressed” disagreement that remains unresolved for a reasonable time.Footnote 15 Until this difference is crystallized into a specific claim, no actual dispute exists.Footnote 16

International maritime disputes: Means of settlement and underlying challenges

It is not impossible for an unresolved boundary difference to evolve into a violent conflict and threaten international peace and stability.Footnote 17 In order to avoid this situation, international law provides several ways for the peaceful settlement of interstate disputes. According to the UN Charter, “[t]he parties to any dispute, the continuance of which is likely to endanger the maintenance of international peace and security, shall, first of all, seek a solution by negotiation, enquiry, mediation, conciliation, arbitration, judicial settlement, resort to regional agencies or arrangements, or other peaceful means of their own choice”.Footnote 18

The obligation on states to resolve their disputes peacefully also extends to the ocean. More specifically, UNCLOS provides that states settle their maritime disputes mutually and through means of their own choice.Footnote 19 As such, no state may unilaterally demarcate a disputed maritime area.Footnote 20 In principle, a mutual solution is achieved through bilateral negotiations that lead to an agreement.Footnote 21 However, negotiations are not always successful. To protect the situation from a potential stalemate, part XV of UNCLOS provides states with a cluster of means of third-party resolution, including international arbitration and adjudication.Footnote 22

The majority of boundary disputes are successfully resolved directly by states through treaties, while only 6–7 per cent of them are settled by international bodies.Footnote 23 This shows that interstate negotiations are much preferable to adjudication and there are two main reasons for this.

For one thing, diplomacy allows states to keep the dispute under their own control. By choosing this path, states are free to determine not only the place and time of their negotiations but, most importantly, their content. They may agree on any boundary line of their preference and take into account factors (economic, political or historic) that would normally be disregarded by an international body.Footnote 24 The second benefit of diplomacy is that it soothes tensions between the disputants. Both sides will join the negotiating table not as competitors but as equal actors. There will be no “winner” or “loser” at the end of their discussions, even if one of them eventually revises its original position in the spirit of compromise. As put by Judge Moore, negotiation is the process “by which governments, in the exercise of their unquestionable powers, conduct their relations one with another and discuss, adjust and settle their differences”.Footnote 25

Despite its benefits, however, diplomacy is not always effective. Not all states show the same will to cooperate and compromise. Neither do they wish to spend valuable time on long rounds of negotiation that may eventually be fruitless.Footnote 26 In such cases, forcing states to the negotiating table would stoke existing tensions rather than soothe them. States may therefore choose to submit their boundary disputes to international courts or tribunals.Footnote 27 Judicial delimitation is the subject matter of this study.

One of the greatest benefits of judicial delimitation is that it provides a “third-party” solution. Upon the submission of a boundary dispute to an international forum, “jurisdiction over the matter shifts to a new body and each side to the dispute is committed in advance to accepting the verdict”.Footnote 28 As requested by the states, the judges will either indicate the criteria for an equitable solutionFootnote 29 or draw the actual boundary line.Footnote 30 Hence, by choosing adjudication, states confer on a third party extensive discretionary powers.

This does not necessarily mean that the announced delimitation judgment or arbitral award is always acceptable to both sides. A maritime dispute arises from the inability of two littoral states to enjoy the full extent of their legal entitlements in the ocean due to coastal proximity. To address this situation, international judges are called upon to separate the states’ overlapping entitlements over the shared maritime space. To that extent, maritime delimitation requires the reduction of each state's legal entitlement in the ocean.Footnote 31

To reach an equitable result, international judges must strike a delicate balance between the disputants’ conflicting entitlements. However, “equity does not necessarily imply equality”.Footnote 32 The concept of distributive justice is incompatible with maritime delimitation. As held by the ICJ, the purpose of maritime delimitation is not the apportionment or division of the disputed area into converging sectors, but the establishment of maritime boundaries in a maritime space that already appertains to both states.Footnote 33

Things, however, are more complex in practice. It is possible that, pending delimitation, state A granted one or more private exploratory permits in the shared maritime space without its neighbour's consent.Footnote 34 This right is not affected by the lack of clear maritime boundaries. Hence, pending delimitation, a littoral state can enjoy the full extent of its entitlement in the ocean, had it not been for the presence of its neighbour.Footnote 35 Besides, as highlighted by international jurisprudence, the lack of fixed maritime boundaries should not in itself preclude a state's economic activities in the shared area.Footnote 36 However, it is also possible that the delimitation judgment eventually awards all or part of the explored area to state B.Footnote 37 In that case, the question arises as to whether the existing private rights will survive.

One would expect judges to take this question into serious consideration during delimitation. Over the years, international jurisprudence has sought to make the process of delimitation as objective and predictable as possible.Footnote 38 That way, the protagonists of a boundary dispute may “estimate” the outcome of delimitation before initiating the process of adjudication. In this light, international judges have developed a particular approach consisting of three steps: the construction of a provisional equidistance line, made of all points that are equally distant from the states’ base points; the correction of this line if required by the circumstances; and a retrospective check of the boundary's proportionality.Footnote 39 This approach is systematically followed in international jurisprudence, “unless there are compelling reasons that make it unfeasible” in a particular case.Footnote 40

However, these principles do not axiomatically safeguard private rights that already exist in a disputed area. Pursuant to the “three-step” process, international judges determine whether there are any factors that may affect the course of a boundary. Traditionally, these factors related to coastal geography, such as the concavity or convexity of the states’ coastlines and the presence of islands in the disputed area.Footnote 41 On the contrary, any non-geographical factors, such as the presence of privately-held concessions (such as for fishing or petroleum operations) in the disputed area, are treated with great scepticism. It must be noted, however, that judges’ stance towards private rights was not always that strict.

In the famous Grisbadarna case of 1909, the arbitrators of the Permanent Court of Arbitration paid particular attention to the private rights of Swedish fishermen in the disputed waters between Norway and Sweden. As stressed by the hearing panel, “it is a well established principle of the law of nations that the state of things that actually exists and has existed for a long time should be changed as little as possible; this principle is especially applicable in the case of private interests which, once disregarded, cannot be effectively preserved by any manner”.Footnote 42 It was observed that, if the line proposed by Norway was eventually accepted, private rights would be threatened with reallocation. This in turn would severely disturb the legally acquired interests of the private persons. To prevent this outcome, the award eventually favoured Sweden.

A few decades later, in Tunisia v Libya, the ICJ affirmed that the presence of oil wells in the disputed area may affect the process of delimitation.Footnote 43 As explained by the judges, this can be the case if the line of existing concessions denotes an explicit or tacit agreement between the states or a modus vivendi [acceptable arrangement] on the preferred boundary line.Footnote 44 Although the ICJ was not requested to draw the actual boundary (but only to determine the factors that would lead to an equitable result), it respected the line of existing petroleum permits.Footnote 45 Consequently, the private rights of the respective operators were protected from reallocation.

Despite these precedents, this position is no longer endorsed in jurisprudence. In a series of subsequent cases, judges have affirmed that a line of oil concessions may indicate states’ consensus on a boundary's location. In none of those cases, however, did the courts adjust or shift the provisional boundary line in accordance with existing permits.Footnote 46

This shift in the stance of judges is not entirely without justification. Because of its position in Tunisia v Libya, the ICJ was severely criticized for pursuing an activist role.Footnote 47 To avoid a similar accusation, judges are now extremely cautious when examining the conduct of states as evidence of boundary agreements.

There are other reasons that support the new stance of judges. It can be argued that disregarding permits during maritime delimitation prevents states from extending claims in the continental shelf through the doctrine of effective occupation.Footnote 48 Although this doctrine is widely accepted in territorial delimitation, it does not apply in the ocean. This is because the rights of every coastal state in the continental shelf exist automatically and, as such, do not depend on claim or occupation.Footnote 49

It can be added that the new approach of judges seeks to discourage competitive drilling among disputing states. By authorizing drilling without its neighbour's consent, a state may breach its procedural obligations to cooperate and not prejudice the final delimitation agreement under articles 74(3) and 83(3) of UNCLOS. Besides, the practice of unilateral drilling in undelimited areas may lead to the wasteful exploitation of shared natural resources.Footnote 50

In summary, judges’ current practice of disregarding any private rights that exist in the area under delimitation does not lack justification. Be that as it may, this practice is in direct conflict with the general principle of international law that protects legally acquired private rights from potential disturbance. It is regrettable that judges no longer refer to this principle, which has been present in international law since the time of Vattel.Footnote 51 Clearly, this omission can have legal and practical implications for non-state actors operating in contested waters. To capture the scale of those implications, this article now refers to the Somali-Kenyan case study.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE SOMALI-KENYAN CASE STUDY

The boundary dispute

This dispute has its roots in Kenya and Somalia's disagreement on the exact location of their boundary in the western Indian Ocean (figure 1). Based on the principle of equidistance, Somalia contends that the boundary should follow a diagonal, southeast route into the ocean, extending from the states’ land border.Footnote 52 According to Kenya, however, the maritime boundary should be “a straight line emanating from the states’ land boundary terminus and extending due east along the parallel of latitude on which the land boundary terminus sits”.Footnote 53

Figure 1. Depicting the parties’ boundary claims in the western Indian Ocean. Kenya's claim follows a parallel line, while Somalia's claim follows the (provisional) equidistance line. This map was prepared by International Mapping for the Government of Somalia and is included in Somalia's application to the ICJ.

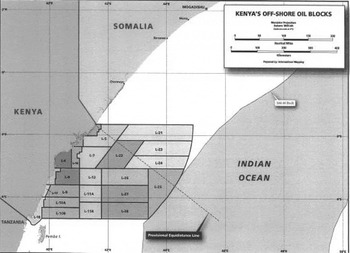

Despite a series of rounds of negotiation, the boundary difference remained unresolved. In fact, it was severely aggravated in 2012, when Kenya granted a number of permits (production sharing contracts or PSCs)Footnote 54 for the exploration of the western Indian Ocean.Footnote 55 Somalia challenged the validity of its neighbour's exploratory permits for oil blocks L-21, L-22, L-23 and L-24 (figure 2), as they fall entirely or partly within the disputed area.Footnote 56 In August 2014, Somalia requested the ICJ to “determine the complete course of the single maritime boundary, dividing all the maritime areas appertaining to Somalia and Kenya in the Indian Ocean”.Footnote 57

Figure 2. Depicting Kenya's offshore oil blocks in relation to the boundary difference. This map was prepared by International Mapping for the Government of Somalia and is included in Somalia's application to the ICJ.

Possible delimitation scenarios

Both states are anticipating the ICJ's ruling with great concern. The significance of the verdict, however, will be much greater for Kenya. Depending on the judgment, the country's upstream operations in oil blocks L-21, L-22, L-23 and L-24 will either continue or cease permanently.

If the ICJ accepts Kenya's boundary claim, the entire disputed area will remain permanently under Kenya's jurisdiction. As a result, the permits granted for oil blocks L-21, L-22, L-23 and L-24 will continue to authorize the activities of Kenya's investors. However, it is foreseeable that the judgment will favour Somalia (entirely or partly). This is because Somalia's boundary claim is based on the “three-step” delimitation approach that is systematically followed in the jurisprudence. If the ICJ complies with this standard practice, it will draw the boundary line regardless of any non-geographical factors that may exist in the disputed area, including Kenya's privately-held oil permits.

Two possibilities arise from the application of the “three-step” approach. The first is that the final boundary will coincide with Somalia's provisional equidistance line. This would be the case if the ICJ finds no geographical circumstances justifying a departure from equidistance.Footnote 58 The second is that the boundary will fall somewhere between the states’ extreme claims. This will happen if the ICJ “corrects” the provisional equidistance line due to coastal disproportionality. In either case, however, the area under Kenya's exploration will be affected. In the first instance, the entire disputed area (comprising oil blocks L-21, L-23, more than half of block L-24 and almost half of block L-22) will be awarded to Somalia. In the case of shifted equidistance, the final boundary will cut through one or more of the four disputed oil blocks (figure 3).

Figure 3. If the boundary is drawn anywhere between the parties’ boundary claims, it will affect one or more of Kenya's oil blocks. Original map taken from Somalia's application to the ICJ (see comment in figure 2). The extra lines on the map have been added by the author for illustrative purposes only.

As a result, the area under Kenya's exploration will shrink, subject to the final positioning of the boundary. Any oil blocks (or parts thereof) located south of the final line will remain under Kenya's jurisdiction; yet, the country will lose any blocks located north of the final boundary.

Each of these oil blocks has been the subject matter of a PSC. The entire contractual relationship, as well as the parties’ rights and obligations, are based on this particular area (contract area). The sudden redistribution of this area to Somalia would cause a fundamental change of circumstances that could ultimately affect the contractual relationship between Kenya and its investors.

Whether Kenya acted in bad faith in unilaterally granting exploratory permits in the undelimited area or whether it violated its procedural obligation to negotiate with Somalia and seek a cooperative arrangement of a practical nature under articles 74(3) and 83(3) of UNCLOS are certainly important issues, although they lie beyond the scope of this analysis. The main question that this article addresses is whether Kenya's privately-held permits will survive a potential redistribution of the contract area due to judicial delimitation. The answer depends on the nature of the instruments in question. The following paragraphs discuss this issue in detail.

THE NATURE OF KENYA'S PSCs

Although entered into between state and non-state actors, the agreements in question are mere private contracts. What is more, these instruments are governed by Kenyan law, which, in essence, is English common law.Footnote 59 Consequently, they are subject to the rules and principles of English contract law, such as the norm pacta sunt servanda [agreements must be kept].Footnote 60 A question that arises is whether the parties to these contracts will remain contractually committed upon the redistribution of the explored area. Put differently, does the fundamental change of circumstances caused by delimitation justify the termination of the affected contracts?

Before 1863, the general rule in English common law was that contracts would remain binding even upon a radical change of circumstances.Footnote 61 The reason was that “where there is a positive contract to do a thing, the contractor must perform it or pay damages for not doing so”.Footnote 62 However, as Sir Hughes Parry put it, “during the last one-hundred years, the courts have been evolving a doctrine to general effect that if there should occur some intervening event or change of circumstances so fundamental on it to strike at the root of the agreement, the contract should be treated as brought to an end forthwith, quite apart from the expressed volition of the parties themselves”.Footnote 63

This remark refers to the doctrine of “frustration of the contract” or more precisely “frustration of the adventure or of the commercial or practical purpose of the contract”.Footnote 64 In particular, a contract is threatened with frustration when: (i) its performance becomes impossible (ii) for a reason that was both unforeseeable by the parties relying on it at the time of entry into the contract and (iii) supervening (not provided for by the language of the contract).Footnote 65 The legal consequence of frustration is that it discharges both parties from the duty of future performance. That way, the principle pacta sunt servanda is inhibited.

This article now examines whether the redistribution of Kenya's oil blocks due to delimitation could qualify as a frustrating event. For that reason, each of the three elements of frustration is discussed in relation to maritime delimitation.

Impossible performance

This element is the most crucial. Although, the term “impossible” is quite vague, some useful interpretative guidelines are found in legal theory and jurisprudence. According to case law, “a contractual obligation has become incapable of being performed because the circumstances in which the performance is called for would render it a thing radically different from that which was undertaken by the contract. ‘Non haec in foedera veni’; it was not what I promised to do”.Footnote 66

As agreed by scholars and judges, an event that makes performance of a contract “onerous or more expensive” is not frustrating.Footnote 67 On the contrary, performance becomes impossible when it is “positively unjust to hold the parties bound” to this contract.Footnote 68 This happens, for example, when the subject matter of the contract is physically destroyed. As held in Taylor v Caldwell, “in contracts in which the performance depends on the continued existence of a given person or thing, a condition is implied that the impossibility of performance arising from the perishing of the person or thing shall excuse the performance … That excuse is by law implied because from the nature of the contract it is apparent that the parties contracted on the basis of the continued existence of the particular person or chattel”.Footnote 69

That aside, performance may also be impossible if the subject matter of the contract is seriously damaged (in the case of goods or cargo) or becomes unavailable. The latter can happen when the subject matter is expropriated by a public authorityFootnote 70 or affected by a court order.Footnote 71 The prospective delimitation judgment of the ICJ could be such an order. As already explained, upon its redistribution to Somalia, an oil block would no longer fall under Kenya's jurisdiction. Although the oil block would not be physically destroyed, it would become unavailable for the purpose of performance of the respective PSC.Footnote 72 In particular, it would be legally impossible for Kenya to authorize upstream activities in an area that belongs to a foreign jurisdiction. If it did so, it would be acting ultra vires.Footnote 73 Similarly, the presence of Kenya's contractors in an area of foreign jurisdiction would result in their legal (civil or criminal) liability towards Somalia. It is, therefore, accepted that maritime delimitation can render the performance of a PSC impossible.

Unforeseeable event

The next step is to examine whether this situation is unforeseeable. According to Treitel, an event is foreseeable and will prevent frustration of the contract only when it is one that “any person of ordinary intelligence would regard as likely to occur”.Footnote 74 One could argue that the redistribution of Kenya's oil blocks is clearly foreseeable, as the boundary difference was known to Kenya and its contractors when the PSCs were signed in 2012. This position can, however, be rejected for the following reasons.

First, although the Somali-Kenyan boundary difference was known in 2012, Kenya and its contractors could not predict that the case would go to court. International law does not oblige states to resolve their boundary differences. In fact, maritime delimitation is not mandatory at all. Nonetheless, if states wish to proceed with delimitation, they may do so through an agreement.Footnote 75 If no delimitation agreement can be reached, then the case is brought to an international body.Footnote 76 However, in order to be settled judicially, a boundary situation must be an actual dispute.Footnote 77 It was explained earlier that an international dispute is not a mere difference of opinion but a “specific and explicitly expressed disagreement” that remains unresolved for a reasonable time.Footnote 78 Based on the facts of the case, the Somali-Kenyan boundary difference evolved into a dispute when Kenya's exploratory permits were granted. As stated by Abdullahi Haji, Somalia's minister of foreign affairs in 2012, “[t]he issue between Somalia and Kenya is not a dispute; it is a territorial argument that came after oil and gas companies became interested in the region. If the argument continues unresolved, it will change into a dispute that may result at last in souring the deep relation between our two countries and (cause a) war at last”.Footnote 79

The diplomatic negotiations that took place until 2014 and the memorandum of understanding signed between Kenya and Somalia in 2009Footnote 80 also suggest that the parties’ intention was to settle their boundary difference through an agreement. Besides, one cannot overlook that the outbreak of civil war in 1991 and the consequent socio-political instability rendered Somalia a “failed state”. It was not until 2012 that the country obtained a permanent central government and entered an era of institutional reconstruction. It can, therefore, be presumed that Kenya could not predict or expect that fragile Somalia would eventually bring the case to the ICJ. Rather, it is likely that Kenya granted the oil concessions in some sort of good faith, expecting that the boundary line (and the future of the existing permits) would be freely decided between the two parties.

Secondly, even if Somalia's plans to seek judicial assistance were already known in 2012, the outcome of judicial delimitation would still be uncertain. No safe predictions can be made until the ICJ's judgment is announced. In fact, it is even possible that the entire explored area will remain under Kenya's jurisdiction after delimitation.

Thirdly, one could argue that a diligent investor (oil company) should have foreseen the risk, the very moment they showed interest in an undelimited area. This would inhibit the investor from invoking frustration.Footnote 81 According to legal theory, however, the mere fact that a particular event “was or ought to have been foreseen … does not (necessarily) prevent it from becoming a frustrating event; the question … is whether the new situation thus created is within or outside the scope of the contract”.Footnote 82 Hence, depending on the circumstances, an event that makes contractual performance impossible can still cause frustration, even if it could or should have been foreseen by one of the parties. After all, no English courts have ever excluded frustration just because the event in question “was or should have been foreseen”.Footnote 83

Supervening event

The existence of this element depends on whether Kenya's PSCs refer explicitly to any changes in the contract area due to maritime delimitation. A clause that would normally refer to this event would be the force majeure clause. Although the concept of force majeure originates from civil law,Footnote 84 it is widely employed in common law when frustration is difficult to establish.Footnote 85 Its purpose is to excuse non-performance upon the occurrence of an unforeseeable and unavoidable event.Footnote 86 As a risk allocation tool, the force majeure clause is freely negotiated between the contractual parties. In most contracts, however, it consists of two limbs: one listing specific events (acts of God, wars, natural disasters) and a general one referring to “any event beyond the control of the parties”. That way (unlike with frustration), contractual parties are prepared for certain risks “beforehand, in an agreed, rather than an imposed, manner”.Footnote 87

Under Kenya's Model PSC, the force majeure clause includes:

“1. Acts of God, unavoidable accidents, acts of war or conditions attributable to or arising out of war (declared or undeclared), laws, rules, regulations, and orders by any government or governmental agency, strikes, lockouts, or other labour or political disturbances, insurrections, riots, and other civil disturbances, hostile acts of hostile forces constituting direct and serious threat to life and property, and all other matters or events of a like or comparable nature beyond the control of the Party concerned, other than rig availability.

2. In this clause, ‘Force Majeure’ means an occurrence beyond the reasonable control of the Minister or the Government or the contractor which prevents any of them from performing their obligation under this contract.”Footnote 88

This clause makes no reference to a boundary dispute (existing or future) or a prospective delimitation judgment. Still, one might consider delimitation to be an event “of a like or comparable nature [to those described in para 1 of the clause] beyond the control of the Party concerned”. That could be based on the fact that the impact of delimitation is unforeseeable.

This study, however, finds that the event of delimitation is not of “a like or comparable nature” to those described in the force majeure clause. A closer look at these events shows that they do not affect the very existence of the contract. What they really do is to freeze (suspend, hinder or delay) the performance of the affected party's contractual obligations. This situation is temporary, as it lasts until the cessation of the particular event. In that sense, force majeure does not exclude liability for a breach of contract; it simply ensures “that non-performance is no breach because no performance was due in the circumstances which have occurred”.Footnote 89 Such circumstances arise from a physical catastrophe, a strike, a civil riot and the like. This is why a force majeure clause usually provides an extension of time to the promisor.Footnote 90 During that period, the contract is dormant but still exists. It is left to the parties’ discretion to agree to cancel the contract if its performance remains impossible beyond a certain time.Footnote 91 However, this is not the case with delimitation, the impact of which is immediate and irreversible. As already seen, once the contract area of a PSC “changes hands”, it becomes legally unavailable. No court has the power to enforce that contract.Footnote 92 Hence, the impact of delimitation on a contract is much closer to frustration than to force majeure.Footnote 93

For these reasons, this study contends that maritime delimitation can qualify as a frustrating event. As a result, and unless the ICJ departs from the fixed doctrines of maritime delimitation, the affected permits will be automatically discharged, even if their subject matter (oil blocks) is partly redistributed to Somalia.Footnote 94 The reason is that, in English common law, there is “no such concept as partial or temporary frustration”.Footnote 95 A contract is either frustrated (in total) or it remains in force.

Further implications of contract frustration

As put by Lord Bingham, frustration will “kill the contract and discharge the parties from further liability under it”.Footnote 96 Consequently, Kenya's contractors may have to abandonFootnote 97 any areas that are no longer under Kenya's jurisdiction, without further liability. Yet, there is another important issue to be addressed. Since “the remedy in a frustrated contract is to place the parties (to the extent possible) back to the positions that they were prior to the contract”,Footnote 98 the question of the contractors’ refund arises.

One of the main features of a PSC is the contractor's commitment to a large capital investment, before conducting any exploratory or development activities. This usually includes: a signature bonus, a monetary security or parent company guarantee, and a series of surface fees payable in advance of certain periods.Footnote 99 If production follows, the contractor first recovers his investment costs by receiving reimbursement from the produced oil (known as cost oil) and then earns a share from the remaining production (known as profit oil). If no oil is discovered, the contractor is not reimbursed at all. In the oil industry, this financial risk is acceptable. However, the risk that may arise from the discharge of a PSC before its completion is different. A situation where the contractor loses any pre-payments (signature bonus or surface fees) due to the contract's sudden termination would be inequitable.Footnote 100 In order to avoid this, the contractor must submit a restitutionary claim.

According to the general (common law) rule of restitution, a claimant can only recover his money if the consideration for his payment has totally failed (total failure of consideration).Footnote 101 This requires that no part of the condition pursuant to which the claimant made a payment to the defendant has been satisfied. Courts, however, have gradually developed a different theory for the case of frustration. Their original position was that the money paid under a contract that became frustrated was irrecoverable.Footnote 102 This was later reversed in the famous Fibrosa case, which held that money paid before frustration was recoverable, but only if the consideration for the payment had wholly failed.Footnote 103 Yet, a strict application of this rule would cause inequitable results in the case of frustrated contracts involving pre-payments.

This problem was eventually tackled by the Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943. This act (also applicable in Kenya)Footnote 104 applies to any contract that has become impossible to be performed or been otherwise frustrated. According to section 1(2), all sums to be paid pursuant to the contract before the frustrating event are no longer payable, while any sums already paid are recoverable. In practice, this means that a total failure of consideration is no longer required in frustrated contracts.Footnote 105 Thus, restitution can be sought even when the contract is frustrated after partial performance. The act adds that any valuable benefit (other than money) obtained before the time of discharge is also recoverable, where that is considered just.Footnote 106

Pursuant to section 1(2) of the act, Kenya's contractors would not only be discharged from future payments, but they could also seek a refund for any payments (signature bonus, fees or guarantee) made before frustration. This refund would cover what was paid under the frustrated contract but nothing more, so there would be no damages for breach of contract or loss of profits.Footnote 107

It is also possible that Kenya's contractors have conducted a series of seismic surveys and geological reports since 2012.Footnote 108 Irrespective of their results (a major oil discovery or a dry well), these services have been performed for Kenya's benefit. Whether the contractors seek compensation for such non-monetary contributions is answered by section 1(3) of the act and the famous case of BP Exploration Co (Libya) Ltd v Hunt (No 2). Footnote 109 In this case, Mr Hunt (who owned an oil concession in Libya) assigned the exploration and production of oil to BP. The company would provide all necessary finance until oil was found, while any profits would be shared between the parties. Oil was eventually found, but the concession was expropriated in 1971 by Muammar Gaddafi's regime. BP (which had already paid half of its contributions) argued that the contract was frustrated, adding that Mr Hunt obtained a valuable benefit from the contractual performance before the expropriation. Therefore, the company claimed a “just sum” of money under the Frustrated Contracts Act 1943. The act provides neither a definition of “benefit” nor a method for its calculation. Hence, the court had to deal with these issues. As Goff J put it,

“Money has the peculiar character of a universal medium of exchange. By its receipt, the recipient is inevitably benefited; and … the loss suffered by the plaintiff is generally equal to the defendant's gain, so that no difficulty arises concerning the amount to be repaid. The same cannot be said of other benefits, such as goods or services … From that very nature of things, therefore, the problem of restitution in respect of such benefits is more complex than in cases where the benefit takes the form of a money payment.”Footnote 110

The court first identified the defendant's benefit, which in that case was the end product of the company's services.Footnote 111 It then estimated the value of this benefit pursuant to the circumstances.Footnote 112 On that basis, Goff J determined the “just sum”, being the sum that would lead to “the prevention of the unjust enrichment of the defendant at the plaintiff's expense”.Footnote 113 This amount consisted of the expenditure made by the claimant plus payments in cash and oil, while deducting the oil BP received in reimbursement. In this light, Goff J accepted that the contract was frustrated and awarded BP $35.4 m, pursuant to section 1(3) of the act. The defendant's argument that BP had contracted to take the risk of expropriation was rejected.

Based on this, Kenya's contractors have a prima facieFootnote 114 right to seek a refund for any contributions (monetary or otherwise) made before frustration. In order to support their claims, the contractors must prove that Kenya obtained a benefit before the time of discharge. As explained above, any monetary pre-payments would constitute a benefit. In the case of non-monetary contributions however, the benefit must be identified and valued by a judge or an arbitrator.Footnote 115

Notwithstanding this right, Kenya's contractors would permanently lose their permits due to delimitation. This in itself is detrimental as, in order to remain in the area, the companies would have to obtain new permits from Somalia.Footnote 116 If they fail to do so, these investors will have wasted a considerable number of years working on the “wrong side”. Furthermore, this may ultimately deter oil companies from operating in contested waters in the future.

A REVERSIBLE SITUATION?

Arguably, this situation would have been avoided if the dispute had not been brought to international adjudication in the first place. For instance, the states could have entered into a delimitation treaty bearing a “grandfather” clause in order to preserve the existing private rights in the shared area.Footnote 117 However, the states’ failure to agree on the exact location of the boundary has made the conclusion of such a treaty unfeasible.

Alternatively, Kenya and Somalia could seek a provisional arrangement in the form of a joint development agreement.Footnote 118 Such an agreement would allow states to develop in common the natural resources of the shared maritime area, while shelving the boundary dispute and complying with their procedural obligation to cooperate under articles 74(3) and 83(3) of UNCLOS. The beneficiaries of this arrangement would not only be the two states but also the private oil companies already operating in the disputed area. Notwithstanding its merits, a joint development agreement is not easy to conclude. As with all agreements, it is the product of good faith, strong political will and mutual consent.Footnote 119 It can be argued that Kenya's economic and industrial superiority, and the fact that Somalia (formerly a “failed state”) still lacks strong domestic institutions, may have debilitated the two states’ relations and ultimately hindered the reaching of such an arrangement.

The ICJ will eventually resolve the boundary dispute. Still, can the foreseeable frustration of Kenya's permits be reversed, even if the existing concessions may not affect the course of the final boundary? This study shows that reversal is possible. The ICJ can encourage the conclusion of an interstate unitization agreement, should the final boundary cut through any of Kenya's oil blocks. In that case, the delimitation judgment will terminate the long boundary dispute, with the subsequent unitization agreement allowing for the development of a potential transboundary reserve by the existing operators on behalf of both states. The outcome of this process would be: the successful settlement of the long boundary dispute by a third party; the common development of natural resources by Kenya and Somalia; and the preservation of existing private interests in the area.

State cooperation post delimitation for the development of transboundary reserves has successfully occurred before in practice,Footnote 120 and has also been encouraged by judges in previous delimitation cases.Footnote 121 It must be noted, however, that cooperation with a view to unitization rests solely on the states’ will and does not yet have the effect of a customary rule.Footnote 122 Nor is it entirely absolved of practical difficulties.Footnote 123 A unitization agreement requires long negotiations or even the modification of each side's resource claims. One would expect that the presence of a clear maritime boundary (post delimitation) would facilitate interstate negotiations. However, how easy would it be for Kenya and Somalia to return anew to the negotiating table in order to conclude a unitization agreement? The pressure to reach such an agreement could imperil the states’ relations or even jeopardize the implementation of the ICJ's delimitation judgment. Apparently, attempts for state cooperation can either bring wonderful results or become a new source of controversy.

CONCLUSIONS

The peaceful coexistence of states falls squarely within the contours of public international law. Yet, when it comes to maritime delimitation, public international law does not stand alone: insofar as there are privately held rights in the disputed area, the establishment of international boundaries is also a matter of private law.

Alas, the main approaches of delimitation followed in modern jurisprudence do not appear to be in line with this statement. As this article has explained, the tendency of judges to disregard exploratory permits during the process of maritime delimitation opens the way to the reallocation and, eventually, the termination of any affected acquired rights in the disputed area. If anything, this creates tension between public international law and private law.

This tension underlies the Somali-Kenyan boundary dispute, which is currently before the ICJ. It has been demonstrated that, insofar as the prospective ruling follows the doctrines of maritime delimitation, it may act as a frustrating event causing the discharge of Kenya's privately held contracts in the disputed area. The key to avoiding this situation is state cooperation through the conduct of a unitization agreement. However, inasmuch as state cooperation lacks the cloak of international custom, the future of private interests in disputed areas remains uncertain.

The fact that existing private rights may suddenly vanish upon the judicial settlement of the dispute raises serious concerns as to the efficacy of the current rules of maritime delimitation. In the bigger picture, it challenges the stance of the international law of the sea towards long-existing international principles, such as the doctrine of acquired rights. Hence, although international adjudication can resolve an interstate dispute in a final and peaceful manner, it may ultimately disturb the private rights that already exist in the disputed area.

It is hoped that this study has informed the ongoing discussion about the legal problems that may emerge during judicial delimitation. Apart from balancing the conflicting interests of states, delimitation should also be concerned with protecting existing private rights in disputed waters. The systematic promotion by judges of state cooperation both pending and post delimitation could be an encouraging first step towards that goal.