INTRODUCTION

It is not easy to discern political negotiation and compromise in the distant past. Oral traditions of conflicts between named individuals point to complex processes of social and political change: to unfold their meaning, however, corroborating sources are necessary, and interpretations can vary widely.Footnote 1 Historians have turned to explorations of the use of space and the meanings attached to space for insights into past social dynamics.Footnote 2 Capital cities, in particular, often express important social realities and ideological concerns. In Dahomey, according to Edna Bay, the structure of the capital and the particular reversal of ordinary social rules inside it expressed the sacred character of the kingdom. Sylvia Nannyonga-Tamusuza argues that the unique forms of gender that operated in the Ganda capital suggest its special power.Footnote 3 Ivor Wilks has argued that Asante ‘mental maps’ of distances from Kumasi functioned as a form of calendar as well as an administrative structure for the state; Thomas McCaskie identifies decline in the power of the Asantehene in relation to provincial chiefs in the nineteenth century.Footnote 4 Benjamin Ray pointed out that Buganda's capital was laid out as a microcosm of the kingdom and reflected its administrative order; Jean-Pierre Chrétien sees the capitals of the interlacustrine kingdoms as ‘both a reflection and a recapitulation of the country’, which were centers of power and crossroads for people and things, but not truly cities.Footnote 5 Henri Médard and Richard Reid have considered how incipient colonial power began to reshape the Ganda capital in the 1890s, and Peter Gutkind focused a study of modern indigenous authority on the administration of the Ganda capital over the first half of the twentieth century.Footnote 6

Examining spatial relationships has led scholars to identify social formations characterized by heterarchy, revealing the ‘continual tension among multiple and competing centers of power and authority and among people who constructed opposing alliance networks’, as Allen Howard notes.Footnote 7 Susan Keech McIntosh and Roderick McIntosh found multiple, overlapping forms of authority in clustered urban sites that they studied in the middle Niger delta. They argued that societies in Middle Niger resisted centralization, social hierarchies, and the monopolization of decision-making; they seem to have organized, instead, in a way that intentionally created heterarchy. The ‘(horizontal) social complexification’ of Jenne-Jeno had political and social value: ‘In heterarchy, the relations between subgroups are those not of coercion and control but of separate but linked, overlapping yet competing spheres of authority.’Footnote 8 Noting the tendency to perceive heterarchy as a stage of social organization that societies pass through on their way to becoming hierarchical, Roderick McIntosh drew a distinct contrast with Weberian theory, arguing that, in a social system characterized by heterarchy, ‘authority is shared among many corporate groups rather than being the monopoly of a charismatic individual (in Weber's sense) or of one bureaucratic lineage’.Footnote 9 Hidden evolutionary assumptions regarding political power can also obscure the role of heterarchal authority in African kingdoms. Where Africans did create hierarchies, the evidence may suggest that people used aspects of heterarchy both to make possible and to restrain the power of kings.

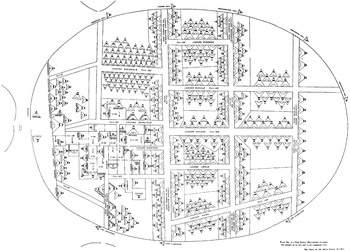

This article argues that people in ancient East Africa in the area that became Buganda relied on heterarchy as a strategy to ensure accountable government even as the kingdom centralized. The precise placement of 292 chiefs and ritual experts in relation to each other and to the king in a map that portrays the capital of Buganda in the time of Kabaka (King) Ssuna, who ruled between approximately 1830 and 1858, portrays not only Buganda's lived practice of power relations but also makes visible the political compromises and accommodations which contributed to the creation of the kingdom (see Fig. 1). A careful reading of the map in conjunction with the rich historical sources for Buganda suggests how people constrained the power of their rulers over several centuries, since traces of successive moments of compromise can be discerned in the placement of compounds in the capital. At the center of the overlapping webs of obligation that formed the Buganda polity was a king who distributed prestige and received tribute in labor and goods, but he held his place by mediating among competing chiefs.

Fig. 1. Kaggwa's map of Ssuna's capital. This map of the capital of Buganda during the reign of Kabaka Ssuna (1830–58) locates 292 chiefs and other figures of authority in relation to each other and to the king. (From John Roscoe, The Baganda (New York, 1911); used with permission of Taylor and Francis.)

If we look beyond the dynastic tradition, which asserts a powerful king from the distant past, we can see that kingship developed out of chiefship and that the first forms of polity were created through carefully composed participation of multiple lineage groups in the region. Buganda's earliest rulers sought to neutralize rival sources of power through strategic incorporation: they exercised a kind of power that focused much more on co-optation than domination. If power in the ancient kingdom of Buganda was assembled – a kind of pulling together of multiple powers, rather than an assertion of one kind of authority over another – then heterarchy was a strategy used both to constitute a hierarchical polity and to curb the king's power. Heterarchy was a tool that allowed centralization and ensured accountability. Diverse authority figures provided significant and effective checks on the king's power prior to the violent expansion in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and, when the king's power grew, he was still surrounded, literally and figuratively, by others who curbed his authority.

A well-established historiography views Buganda as an example of emerging African bureaucracy on a Weberian model. But the perception of the Ganda as bureaucratic modernizers, as ‘autocratic modernizers’, or, more recently, as ‘defensive modernizers’ can best be understood as originating in one side of a political argument.Footnote 10 The sources for this version of Ganda history were generated in the context of the massive conflict over land, political voice, and prestige that engaged articulate Ganda from the time that landed property was created in 1900. When Sir Apolo Kaggwa, the chief architect of Ganda–British collaboration, came under attack for his autocratic style after wielding power for more than twenty years, he narrated the entire history of the kingdom as a sequence of clashes in which kabakas (kings) dominated all others.Footnote 11 Kaggwa's statements regarding the absolute power of kings and their tendency to take the land of clans legitimized his own self-serving actions in the allocation of mailo (privately owned) land in 1900, and his imperious domination of Buganda as katikkiro (prime minister) for decades. As I have suggested elsewhere, Kaggwa and his opponents in the 1920s argued over the nature of good government using only the aspects of Buganda's history that suited their causes. Kaggwa and his co-regents claimed that the dominating power that they had assumed was actually the king's power, and ignored every instance of a king capitulating or a subordinate figure successfully taking initiative; meanwhile, his opponents ignored the coercive violence of the kingdom's expansion and claimed that kings always returned the prestige and land that they took from lesser authorities.Footnote 12 Neither version conforms to what can be discerned of the historical record, but Kaggwa's assertion of royal power became the basis of a view that effectively erased the memory of heterarchy in Buganda's political order.Footnote 13

Kaggwa's monarch-focused history of Buganda politics fitted with the structure of the polity that could be perceived in the mid-twentieth century. By that time, a core element of heterarchy – the power of royal women – had ceased to exist.Footnote 14 British explorers who visited the kingdom in the late nineteenth century had failed to perceive the political power of the queen mothers they encountered. They wrote about the women's actions as bizarre, capricious and amusing, rather than as an integral part of the political system.Footnote 15 The critical political power that royal women had wielded was diminished by cataclysmic nineteenth-century violence, ignored in colonial governance, and erased from memory by colonial education. The rampant violence of the nineteenth-century slave trade, when warlord politics came to dominate East African societies including Buganda, had eroded the complex, heterogeneous power relationships and the checks on the power of the king, and colonial authority recognized only three bureaucratically ranked categories of chiefs. Colonial authorities rationalized their rule in reference to the widespread brutality that nineteenth-century visitors had observed, and some historians interpreted ambiguous oral sources in a way that extended despotic violence into the indefinite past. As Christopher Wrigley explained Buganda, ‘To win power, you must have spears behind you; to keep it, you must ensure that they are not plunged into your back’ – an observation that might have accurately described ruling strategy in colonial Uganda as well as earlier but misrepresented the political logic of a deeper past.Footnote 16 In the post-colonial era, historians have explored other paradigms for political integration, including trade, ritual, healing, and environmental pressures.Footnote 17

In order to contribute to the growing body of work which recognizes an intentional complexity in ancient African polities, this paper first considers the validity of the map of Ssuna's capital as a historical source and then explores evidence for reliance on heterarchy in successive stages of the development of the kingdom.

MAPPING AND MAPS IN BUGANDA

The map of Ssuna's capital, attributed to Apolo Kaggwa when it was published in John Roscoe's The Baganda in 1911, is a form of ‘evidence in spite of itself’, in which relationships encoded in spatial terms reveal not only political logic and the functioning of heterarchal forms of accountability but also the development of those forms over several centuries. There are three extant maps of nineteenth-century Ganda capitals, drawn in exactly the same style: Ssuna's capital, the royal enclosure inside that capital (both published by Roscoe), and a large map of Kabaka Muteesa's capital that hangs in Makerere University's Geography department. In 1906, Apolo Kaggwa brought knowledgeable chiefs, royal women, and clan elders to be interviewed by himself and Roscoe, and his book Empisa za Buganda, as well as Roscoe's, resulted from those interviews. It seems likely that Kaggwa made his maps as a result of those joint interviews conducted in his parlor, as the text asserts:

The plans have been drawn by the Katikiro, Sir Apolo Kaggwa, who was aided by the most intelligent of the old men who knew the place, and who had lived either in the Royal Enclosure or in the Capital during King Suna's life time.Footnote 18

This, and a similar statement in the preface, are the only extant explanations of the maps, since no papers relating to the production of The Baganda are known to exist, and there is no reference to the maps in the Kaggwa papers in the Makerere University Africana Collection.Footnote 19

It might be argued that Apolo Kaggwa drew Ssuna's capital with 370 compounds and 292 named figures of authority in order to impress a foreign audience with the grandeur of Buganda, or to enhance his claims regarding the predominance of royal power over all others. Kaggwa's books, memoranda, and papers present a challenge of interpretation familiar to historians of other parts of Africa: this key interlocutor between his own society and foreigners also promoted particular interests.Footnote 20 Fortunately, a multitude of sources – including vociferous contemporary critics of Kaggwa – allow the historian to weigh the validity of his work, including these maps. Information that we have regarding the political importance that the Ganda attached to the physical location of authority figures in relation to each other and what we know about how Ganda marshaled spatial information for their own goals before and during negotiations with imperial entrepreneurs suggest that the Ganda had already been thinking spatially about the kingdom and the capital, without the technology of map-making.

The Ganda marked social and political relationships in how they allocated and occupied public spaces. The bones of important dead people were exhumed, and moved, not infrequently, into a place where their influence was desired or out of a place where their influence was not wanted.Footnote 21 In 1900, when Ganda chiefs began to allocate the 20,000 square miles that were to be their part of the mailo land division, they assigned a square mile to each of the deceased kings. Explaining their decision to British authorities who did not approve of granting land title to dead kings, they said

It was in this way: every dead Kabaka had his katikiro as well as his other chiefs at the place of his burial. Our intention was therefore that each dead Kabaka should be allotted one square mile which should be marked out in his name. This would have been in conformity with the old native custom for the deceased Kabaka to possess estates and their chiefs.Footnote 22

Living people's placement also mattered. Chiefs sat in the king's assembly according to a strictly determined order: during the reign of Kabaka Juuko in the mid-seventeenth century, a new ritual had been devised to keep order among chiefs who disagreed about their proper place in the lukiko, the king's assembly.Footnote 23 In 1906, Kuruji, who had been a chief who was ‘custodian’ to Kabaka Mutesa, described the placement of 17 specific chiefs, ranged on both sides of the king; 29 other seats were allocated to those who entered the assembly first (see Fig. 2). Kuruji explained the rules:

If Kibari came in first he could sit where Mukabira or Namutwe usually sat, or if Mugema were away with the King's permission he could sit in his seat. If e.g. Kimbugwe were absent, Kangao might move up, and Kibari be asked to sit in Kangao's chair, he could not sit above a county chief. There were six county chiefs on the left, four on the right. The Katikiro and Kuruji had no chairs, but sat on the ground. The others had stools to sit on.Footnote 24

In the king's assembly, chiefs' distance from the king demonstrated their particular place in the kingdom: Kaggwa's map portrays the same meaning conveyed in the entire capital.

Fig. 2. Seating of chiefs in Kabaka Mutesa's assembly. Where chiefs sat in the king's assembly demonstrated their relative importance: Kabaka Mutesa's steward, the chief Kuruji, dictated the details in this sketch to John Roscoe in 1906. (University of Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Africa, s. 17, 56, used with permission.)

The placement of compounds in the Ganda capital stayed the same over different reigns and in different locations: Ganda kings moved their capitals frequently, but they were always rebuilt in the same pattern. The significance of the order of the capital can be inferred from an attempt to change it. The fragile peace that ended Buganda's civil war was almost destroyed in 1893 when Catholic and Muslim chiefs refused to bring their people to do obligatory labor for the king in the capital: they demanded a greater share of the provinces and of the land of the capital, and they received it.Footnote 25 Roscoe claimed that ‘for many generations the same plan of laying out the Capital and the Royal Enclosure has been followed’.Footnote 26Mugema, the extremely important chief known as ‘the father of the kabaka’ and ‘the prime minister of the deceased kings’, whose central place in the capital and in the kingdom is discussed below, had been, from the earliest memories of the kingdom, responsible for taking care of the princes. It is to be expected, therefore, that the map of Ssuna's capital locates the princes living exactly adjacent to the mugema. However, the responsibility for the princes was transferred from the mugema to another chief, kasujju, in the reign of Kabaka Mutebi, seven generations and two hundred years before the time of Kabaka Ssuna. That princes continued to live next to the mugema in the early nineteenth century, even though the kasujju became responsible for them sometime around 1650, suggests that the placement of chiefs and others in the capital remained the same over a period of time that extends hundreds of years into the past.

Ganda chiefs had used spatial knowledge of the kingdom and the capital in negotiations before Roscoe arrived in Buganda. Kaggwa and the other regents produced a list of over 600 chiefs between the first and second day of negotiations with Commissioner Harry Johnston in 1900, and the allocation of space in the capital had been a subject of intense debate among Ganda leaders in the successive efforts made, in the 1880s and 1890s, to end the civil war by layering new religions into the order of Ganda chiefship.Footnote 27 The view of the capital portrayed in the map may have been codified as part of those negotiations: as Allen Howard notes, people can make maps without drawing those maps out on paper.Footnote 28 Roscoe implied that Kaggwa was the principal creator of the maps: ‘No attempt has been made to draw the plans to scale, they are sent forth as they were received from the Katikiro.’Footnote 29 These maps suggest that the Ganda thought about power in spatial terms and that they embraced map-making with the same enthusiasm they evinced for literacy as soon as they were exposed to it.

Maps drawn by Protestant and Catholic missionaries in 1892, and a map of the palace drawn by Alexis Sebowa (who held the important chiefly office of pokino), are remarkably similar to Kaggwa's maps, although they portray less detail.Footnote 30 Both the White Fathers' map and a sketch map by the Protestant missionary Baskerville (see Figs. 3 and 4) were drawn to explain the battle of Mengo in January, 1892, and they therefore mark the locations relevant to that conflict. Both include several chiefships created after Ssuna's time, but the pattern of roads and placement of chiefs' compounds are the same as they are on Kaggwa's map. The White Fathers' map specifies the location of 21 chiefs and figures of authority; Baskerville shows fewer, leaving off the lubuga (‘queen-sister’), the sengoba, and the mugema, among others. Both show the British fort, the market, and the missions, established after Ssuna's time and therefore not on Kaggwa's map. The Catholic map also shows the ancient capital of King Karema, the tomb of King Mutesa, and Natete, the village of Arab traders. The critical point, in terms of assessing the validity of Kaggwa's map, is that every chiefship they show that was also on Kaggwa's map is in the same location.

Fig. 3. White Fathers' map of the capital in January 1892. While the White Fathers noted fewer than twenty of the chiefships located by Kaggwa, the chiefships they name that had existed in Ssuna's time are in the same location relative to the palace. (From P. G. Leblond, Le Père Auguste Achte (Algiers, 1912).).

Fig. 4. G. K. Baskerville's map of the capital in 1892. This map has less detail, but the locations of chiefships match those of Kaggwa and of the White Fathers. (Adapted from John A. Rowe, Lugard at Kampala (Kampala, 1969), used with permission of Pearson Education Ltd.)

The maps of the palace interior produced by Kaggwa and by Pokino Sebowa are also fundamentally congruent, although they are drawn in different styles (see Figs. 5 and 6). Sebowa's is a rectangle with 128 squares and rectangles on the inside, marking compounds, streets, and gardens. Kaggwa's is oval, with named streets and 496 houses. The two maps show the same streets and the same important buildings in the same locations: the bulange, the room where chiefs assembled to meet the king; another room where the king heard disputes; store rooms for the royal treasure; and places at the far left and far right of the palace where the king forged iron and beat bark-cloth. Both maps indicate that movement inside the palace involved turning many corners; it would not have been possible to see any distance inside, in contrast to the Ganda style for roads outside the palace, which were broad and straight. Kaggwa's map shows distinct waiting rooms for princes, chiefs, wives, and other people, and each of those groups also had its own space to meet with the king. Sebowa's map indicates three hills inside the palace, which the king could climb in order to look out and see what was happening in the palace and the capital. The existence of the panoptical hills, as well as the coherence of the extant maps and the evidence of Ganda spatial thinking all suggest that the map of Ssuna's capital provides profound historical insights, even though the precise conditions of its creation cannot be determined.

Fig. 5. Kaggwa's map of the Ganda palace. (From John Roscoe, The Baganda (New York, 1911); used with permission of Taylor and Francis.)

Fig. 6. Sebowa's map of the Ganda palace. This is remarkably similar to Kaggwa's map. (From Julien Gorju, Entre le Victoria, l'Albert et l'Edouard (Rennes, 1920).)

COMPROMISE, ACCOUNTABILITY AND CO-OPTATION IN THE EARLY HISTORY OF BUGANDA

The histories of kingdoms begin with kings, who arrive and convince people to follow them. According to tradition, this happened for Buganda when Kabaka Kintu came to the Lake Nalubaale (Victoria) area with some clans, and met other clans there; and after Kintu disappeared in a forest, the kingdom was saved through the arrival of his grandson Kimera from Bunyoro. A more complicated story underlies the oral tradition. Somehow, people organized themselves in a way that involved accepting a ruler. At some point in time, people following a leader whom they could see and visit accepted being ruled by someone further away, whom they could not see. In attempting to perceive the nature of these gradual changes in political practice, it is important to keep in mind that the categories that make sense in the present did not exist when these processes began. Kings, clans, and chiefs have not always existed: kings became kings as we know them, and clans and chiefs became clans and chiefs as we know them, in interaction with other figures of authority over a long period of time.Footnote 31 At some point in that process in the area north of Lake Victoria, a kingdom that we could recognize as Buganda came into being. Yet people lived in that area, pursuing a form of subsistence centered on bananas, from some time around 1000 CE, and some of their story can be discerned.

Several points in the long history of a coalescing polity can be read in the placement of compounds in the Ganda capital (see Fig. 7). Furthest back in time, the siting of compounds in the capital replicates the grouping of homes and banana plantations along a street leading to the compound of a chief – a pattern of settlement that was likely to have been established around 1000 CE as intensive banana cultivation came to predominate in the area north of Lake Victoria that was to became Buganda.Footnote 32 Some time later, before 1500, a loose confederation of groups who collaborated in religious activity was formed: a trace of that ancient organization is visible in the placement of compounds around the very outside edge of the capital. At some point, probably after 1500, the people and their leaders who collaborated in some forms of worship assented to a king. It is impossible to know how that happened, but the structure of the capital shows limits on the power of the king: figures of authority who had held power before him, and others who had the power to challenge him, are placed near, but across running water from the palace. A new form of kingship arrived in Buganda from Bunyoro around 1600 – placed in the very center of the capital are the compounds of the two chiefly titles brought from Bunyoro. The capital also bears the mark of Kabaka Mawanda's transformation of the order of the kingdom, which occurred around 1700.

Fig. 7. Old and new authority in the capital. Older figures of authority, whose power checked that of the king (highlighted here in solid grey), had compounds in the capital across streams of running water from the palace. The newest figures of authority, highlighted here in grey stripes, had compounds in the open space in front of the palace that replicated a chief's courtyard. (Based on Fig. 1.)

Concepts and practices of political organization premised on heterarchy predated the foundation of Buganda. The origins of kingship in ancient East African understandings of chiefship can be glimpsed in the way that the spatial organization of Ssuna's capital replicates the spatial organization of the ekyaalo (settled community), the form of settlement that had been used by people living to the west and north of Lake Victoria for hundreds of years before the foundation of the kingdoms. According to David Schoenbrun, the people who lived to the west and north of Lake Victoria and spoke a common language between about 500 BCE and 500 CE used the term ekyaalo to designate a neighborhood that stretched along the top of a hill, in which each homestead connected to the others by a path that led to the compound of the chief.Footnote 33 The physical space of Ssuna's capital also consists of long, rather straight streets of compounds that reach toward a large open space facing the lubiri, the palace of the king. In contrast to the well-known maps of Kumasi, the capital of Asante, the roads from each province do not lead into the capital from every direction; rather they converge on one side in a way that makes the shape of the capital the same as the shape of the ekyaalo. The open space in front of the palace supplied for the kingdom what the chief's courtyard did for the people of a chief: it was the place where cases were heard, where people brought tribute in goods and in labor, and where they received gifts that demonstrated their connection to those who ruled.

Chiefs and other figures of authority in Buganda protected themselves from the overbearing power of a king in the same way that followers protected themselves from the overbearing power of a chief: they withdrew their support. People attached themselves to a chief and received land to cultivate, reflected prestige, and a chief's service in deciding cases through a relationship of allegiance known as kusenga (to attach to a superior); the follower reversed that process and left a chief through kusenguka (to leave a superior) if he was dissatisfied with his land, or with his chief's demands, or his chief's poor decisions, or his chief's sinking social status.Footnote 34 Legal cases, recorded oral traditions, and ethnographic evidence from the early twentieth century all attest that chiefs struggled to hold on to their followers and that the terms of the relationship favored the followers.Footnote 35 According to Ganda proverbs, ‘Musenze alanda’ (‘The follower often changes his master’) and ‘Busenze muguma: bwe bukonnontera n'osongola’ (‘Service is like the digging stick: when it has become blunt, you point it again’).Footnote 36 The relative abundance of land and scarcity of labor meant that chiefs needed their followers more than followers needed their chiefs. The strategy of withdrawing support from one chief and giving it to another resulted in the extremely dense web of chiefships and overlapping allegiances in the oldest parts of the kingdom so graphically illustrated by Lloyd Fallers, and recently analyzed by Henri Médard.Footnote 37

Recorded dynastic tradition indicates that chiefs and other figures of authority used the same strategy of withdrawing support to exert pressure on kings who ruled badly. Kabaka Kagulu, whose cruel and unstable reign in the early eighteenth century is remembered as a kind of anti-government, provoked a rebellion that took the form of chiefs gathering not in the courtyard of the king but on a hill adjacent to it, and jeering at the king; they refused his attempts to persuade them back to the court, which was a sign to Princess Ndege Nassolo to organize men to overthrow the king.Footnote 38 The Ganda also famously withdrew support from Kabaka Mwanga when he planned to maroon and kill his Christian chiefs on the Ssese islands; the chief Nyonyintono told Mwanga, ‘All Buganda refuses to take you to Ssese’.Footnote 39 Nineteenth-century visitors to Buganda experienced the effects of chiefs and other powerful figures refusing to support the king. Food, firewood, porters, and guides were all in the gift of the king, but only if the chiefs and others who controlled those resources produced them.Footnote 40

Important exchanges took place in the courtyard of the compound of a chief, in the kingdom equivalent (the large open space in front of the palace), and in the king's audience rooms inside the palace. Followers of a chief brought him banana beer and part of their hunt, and provided services such as maintaining roads, bridges, and the reed fences that marked his status; chiefs brought the king the same things, as well as specific gifts, such as named canoes or particular crafts that marked the relationship of that chiefship to the king.Footnote 41 These gifts were prestations, in Mauss's sense of the term: the ‘bond created by things is in fact a bond between persons’.Footnote 42 Chiefs brought gifts in a way that would ensure everyone in the capital recognized their contribution. The explorer James Augustus Grant observed firewood being ceremoniously presented to the king in 1860:

all were under officers, perhaps a hundred in one party. If wood is carried into the palace up the hill, it must be done as neatly as a regiment performs a manoeuvre on parade, and with the same precision. After the logs are carried a certain distance, the men charge up hill, with walking sticks at the ‘slope’, to the sound of the drum, shouting, and chorusing. On reaching their officer, they drop on their knees to salute, by saying repeatedly in one voice the word ‘n'yans’ … Each officer of a district would seem to have a different mode of drill.Footnote 43

These elaborate rituals of exchange also contributed to mechanisms of accountability, because Ganda wielded reciprocal obligation to make their rulers take the actions they desired. The men of a chief bringing wood to the capital all repeated ‘n'yans’ (‘thank you’) to express their gratitude for the opportunity to do the work, but the consequence of their work and their politeness would be their chief's ability to extract some corresponding gift or privilege from the king.

Exchanges of gifts appear to be at the heart of the formation of the ancient polity that became Buganda. During the centuries that people dwelling north of Lake Victoria began to cultivate bananas intensively and to adapt their social institutions to the circumstance of permanently cropped banana gardens, people who headed lineages were not the only leaders of communities. Since land was abundant and the surplus produced by intensive banana cultivation led to a rising population, we can surmise that people left to form new communities, following leaders who attracted adherents for a variety of reasons. Some might have been leaders of a lineage branch; others might have gathered followers around the grave of a particularly illustrious ancestor; some drew others to themselves as a result of charisma or because they had amassed material resources that could be used in supporting a group of people opening new land. When these many kinds of leaders affiliated with each other in a polity with a king, mutual obligation was the language that explained their connection. The most substantial chiefships in the hierarchy of the kingdom came into being when people who already had authority over land and people associated themselves with the king by offering a service. M. S. M. Semakula Kiwanuka has pointed out that the rulers of the ancient central areas of Buganda, who had status as elders of clans and rulers of people, became chiefs with titles that indicated work in the royal household. Kaggo, the leader of the seed clan who controlled much of Kyaddondo, became the chief called ‘sabaddu’ (‘chief of the servants’), who supervised people who worked in the household, and his immediate subordinate was ‘sabakaki’, chief of the palace guards. While these chiefs controlled large, important provinces (which had previously been their independent territories), they also continually carried out the work of their office for the king.Footnote 44 Service to any king in the history of the dynasty created bonds of connection and obligation with the ruling king. For example, a new king had had to visit the land on which the seed clan herded for kings since the time of

Kabaka Nakibinge, who planted a tree there for us to tie on his cow which we look after there and which is called Nakawombe; moreover the present Kabaka Daudi Chwa came to this place and saw this very tree and he also gave us his own cow to look after.Footnote 45

The services clans performed for the king brought them close to royal power, but also gave them the capacity to withhold a service he required.

The services that defined how clans and autonomous chiefships connected to the king expressed the ‘undischargeable debt – a lore of extraordinary sacrifice by one group for others’, which, according to Roderick McIntosh, characterized heterarchy in the middle Niger.Footnote 46 Another ‘mechanism of integration’ for Buganda was the new moon ceremony, in which the organized, extended lineages that we call clans reminded the king of what they had done for him, and what their ancestors had done for his ancestors. Lineages preserved the memory of their services to earlier kings by continuously appointing living people to the positions of high servants to deceased kings.Footnote 47 The kingdom's strategies for accountability also seem to be modeled on the strategies that followers used with their chiefs: gifts of services and things linked chiefs and followers, and also kings and people, and groups of chiefs unhappy with the actions of a king withdrew their support in the same way that a dissatisfied client withdrew his allegiance to his chief.

PRE-ROYAL POWERS: RITUAL ELDERS ON THE EDGE OF THE CAPITAL

The assembled, deliberately constructed coalitions of multiple holders of power that characterized Ganda politics seem to have emerged as kingship developed. A suggestion of this comes from the most remarkable feature of the map of Ssuna's capital: leaders who had power to challenge the king lived on the edges of the capital, across streams of flowing water from the king. Jean-Pierre Chrétien observes that forms of kingship emerged throughout the Lakes region of East Africa around five centuries ago, and views the creation of kingship in Buganda as particularly characterized by ‘a compromise between a new authority, of a strongly religious nature, and a network of influential clans’.Footnote 48 Kaggwa's map of Ssuna's capital reveals that the compromise involved retaining the autonomous power of leaders who had preceded the kabaka in a way that distinguished their authority from that of the king. The flowing water that separated the king's power from his challengers' power appears to be a physical statement of Ganda political logic: multiple forms of authority should exist, they could be contiguous, but they must be distinct; and the opposition among them needed to be managed, and cooled.

It is not possible to determine when the balance created between a king in the center and powerful figures surrounding him came to be an aspect of kingship in Buganda, but a number of sources indicate that it was very ancient and that this arrangement would have been part of the earliest form of kingship in the region. Suggestions of the process of establishing kingship can be traced in historical linguistics, in comparisons of similar institutions across the region, in dynastic traditions, and in the map of the capital. The people who had settled in the Lakes region sharing a common Bantu language and mixed-farming system began to develop more distinct forms of subsistence, and their languages began to diverge around 1500 years ago; according to David Schoenbrun, the intensive banana cultivation that came to characterize Buganda emerged between 900 and 1100 CE.Footnote 49 The first kinds of larger associations were religious, and some of them, practiced by people who now speak distinct languages, must have preceded the establishment of kingdoms. As mentioned above, in the area that became Buganda, a kind of kingship that involved clans collaborating to support a king came into existence sometime before 1500. This ruler, called Buganda-Ntege-Walusimbi, ruled a confederation of clans, and it is possible that the flowing water divisions between the king's power and others' power derive from this period.

The forms of religious association that preceded kingship in the Lakes region of East Africa suggest an intentional effort to compose power through combining different groups. These practices drew multiple clans into interaction with each other for spiritual practice. Many of the clans participating in the area that became Buganda were ‘firstcomer’ clans, or clans that claimed to have arrived with Kintu, Buganda's mythical first king. The Mbajwe cult required the participation of the kativuma seed clan, the yam clan, the leopard clan, the bushbuck clan, and the grasshopper clan.Footnote 50 Worship of Kintu at Magonga involved tasks performed by members of the pangolin clan, the leopard clan, the vervet monkey clan, the buffalo clan, and the grasshopper clan. Kintu worship can be dated to sometime after 500 CE but before 1000 CE, since it was practiced around the region. The Mbajwe cult probably started after Luganda had emerged as a language, around 1000 CE.Footnote 51 In contrast to worship of the lubaale deities, which arrived later and were often primarily associated with one clan, the Mbajwe and Kintu cult rituals required members of different clans to act together, each clan designate carrying out a particular function. The katambala (head of the sheep clan) was in charge of the strong spiritual medicine Mbajwe: his compound is one of those placed across a stream of running water from the king when a king in Buganda began to have a capital.Footnote 52

Intentional clan collaboration is also evident in the ancient Buganda-Ntege-Walusimbi form of kingship. These kings were not included in the king list of the dynastic tradition (although some early twentieth-century writers hotly disputed Kaggwa's king list), but hints of the pre-kabaka-style king remain.Footnote 53 A Ganda folk tale records that God sent the moon to report on how well Walusimbi was ruling, which made the sun jealous, causing a fight that gave the moon its dark spots. Christopher Wrigley suggests that Walusimbi controlled a center of ritual activities directed towards fertility and agricultural prosperity at Bakku in Busiro.Footnote 54 A trace of the earlier kingship is visible in the role that the civet clan elder, Walusimbi, and other firstcomer clans played in the installation of a kabaka. In what Benjamin Ray argues are the oldest ceremonies for ‘confirming’ the king, leaders of the civet cat and lungfish clans carried out ritual exchanges at Bakku with the new kabaka, which demonstrated that those leaders – who wore royal regalia for the ceremony – assented to the king's rule. The nankere, leader of the lungfish clan, gave the incoming king beads from his own crown, and the king had to trespass and then pay a fine for trespassing, ritually acknowledging authority preceding his own. Named officers of the vervet monkey, mushroom, seed, and colubus monkey clans also participated in these aspects of a king's installation.Footnote 55 We can surmise that the many specific clan contributions to the ‘confirming the king’ ceremonies reveal aspects of the pre-existing form of kingship. Like the Mbajwe and Kintu cults, the Walusimbi kingship seems to have drawn apparently autonomous clan groups into association with each other.

CHALLENGERS TO THE KING: WATER BOUNDARIES IN THE CAPITAL

The placement of compounds in the Ganda capital asserts the power of people organized as clans to choose the king, and to check his power. While the institution of the clan undoubtedly changed in interaction with kingship, some form of extended lineage identified by an avoided totem was an ancient form of social organization shared by the earliest Bantu-language-speaking inhabitants of the Lakes region. Three royal women and the important chief mugema – the most critical kingmakers – all had compounds on the edges of the capital, across streams of flowing water. In contrast to other forms of monarchy in the region, Ganda princes took their mothers' clans. This meant that all organized extended lineages could expect one of their sons to become king at some point, and when that did happen, the extended lineage would hold the offices of nnamasole (queen mother), whose authority and court mirrored that of the king, and nabikande (sister of the queen mother), who oversaw the pregnancies of all the king's wives. Another clan would have the office of lubuga (queen sister – chosen from among the half-sisters of the king by the same father), who participated in all the king's councils and had her own set of subsidiary chiefs. These powerful women ruled their own domains, checked the power of the king, and, along with the chief mugema, had a significant role in choosing the next king. The mugema, clan leader of the vervet monkey clan, advised the king as his ‘father’ and the ‘prime minister’ of the deceased kings, all of whose shrines were in his territory. He played a critical role in the installation of new kings, and his unique voice was marked in ritual prohibitions: he stood instead of kneeling in the presence of the king, and he did not eat food prepared by the king's cooks.Footnote 56

According to elders who provided information to John Roscoe in 1906, the queen mother and the queen sister had to live on their own hills, separated by a stream of flowing water, because they were also kings and ‘two kings could not live on the same hill’.Footnote 57 The power these women wielded was substantial. The queen mother appointed her own set of ministers, mirroring that of the king, placed them on lands that were exclusively under her control, and received a portion of all taxes collected.Footnote 58 Her lands, located in every part of the kingdom, gave her a material base independent of the king: the people who lived on these lands served her and not the king.Footnote 59 The queen mother's lands were exempt from taxation by the king, and from plundering by his men. The chief sabaganzi (the queen mother's brother), her prime minister, and other appointed chiefs did not have to obey the king or his ministers. She had the responsibility, according to Ham Mukasa, a nineteenth-century colonial chief, of preventing the king from acting in a way that harmed his people.Footnote 60 The explorer John Hanning Speke described the queen mother's palace in 1862:

every thing looked like the royal palace on a miniature scale. A large cleared space divided the queen's residence from her Kamraviona's [Prime Minister's]. The outer inclosures and courts were fenced with tiger-grass; and the huts, though neither so numerous nor so large, were constructed after the same fashion as the king's. Guards also kept the doors, on which large bells were hung to give alarm, and officers in waiting watched the throne-rooms. All the huts were full of women, save those kept as waiting rooms, where drums and harmonicons were placed for amusement.Footnote 61

The physical palace expressed the political logic that the queen mother's power mirrored that of the king. Meanwhile, the queen sister participated fully in the king's decision-making, and also had lands throughout the kingdom, and her own hierarchy of chiefs.Footnote 62

The royal women whose compounds ringed the capital, along with the chief mugema, acted as king-makers.Footnote 63 The nabikande controlled potential future kings in her supervision of all pregnant wives of the king, and the mugema had had the responsibility of caring for the princes, until the reign of Kabaka Mutebi, who probably reigned in the middle of the seventeenth century.Footnote 64 Even after that, the princes had a compound near the mugema's, across the same stream. The work of the nabikande and the mugema for the kings' children paralleled what would have been done by the ssenga (the mother's sister) in a normal family: they took care of the king's children for the kingdom. A clan obtained the kabakaship when one of its members who was a wife of the king succeeded in mobilizing her clan members and their allies to support her son as the next king. Since one clan did not provide a sufficiently large number of supporters to win the throne, the successful queen mother had to create broad-based support in order for her son to come to power.Footnote 65 A Ganda king was therefore permanently beholden to his mother and the coalition of clans she had assembled to back him.

The placement of the katambala, the mugema, and the three royal women across flowing water could have been a statement of how participants understood a new kind of power as they created it. The many clans that contributed to the religious practices that preceded the creation of the kingdom might have assented to a king who was first among his equals because of the role that powerful royal women gave to clans. Alternatively, the queen mother's mirroring of the king, and the flowing water that divided her and the others from the king, could reflect a compromise, a deliberate effort at cooling conflicts over power that emerged as the kingdom developed. However it came to be, the dynastic tradition reveals queen mothers guiding and admonishing kings, and, until the late nineteenth century, kings did not win conflicts with their queen mothers. The placement of these figures of authority across streams of water demonstrates the importance of distinct, autonomous authority in early Buganda and a way of thinking about power that placed distinct forms of authority in relation to each other.

A PLACE FOR THE NEW IN THE KING'S COURTYARD

The newest forms of authority, in contrast, were in the absolute center of the capital. Two very large compounds faced the king's across the courtyard; these belonged to the katikkiro (prime minister) and kimbugwe (‘keeper of the king's twin figure’) (see Fig. 7). According to an oral tradition, the holder of the office of keeper of the king's twin figure, which had previously been called wolungo, bought the right to change the title of the office to commemorate his service to the Kabaka Kimbugwe, who probably ruled around 1600.Footnote 66 Since the katikkiro and the wolungo also existed in the kingdom of Bunyoro, and since they were not attached to a particular Ganda territory, it seems likely that these two offices came into existence at the same time that a new king from Bunyoro (or an indigene adopting Nyoro royal ritual) became king over an earlier hierarchy in Buganda.Footnote 67 The shrines of lubaale deities, like the compounds of the prime minister and the keeper of the king's twin figure, represent a new form of power that had to be accommodated. Worship of lubaale deities had arrived in this region around 1500, allowing people to seek occasional assistance from or to devote themselves to the worship of these spiritual forces.Footnote 68 Kings and lubaale forces engaged in conflicts over what each owed to the other that lasted generations.Footnote 69

The lubaale shrines and the compounds of the two central chiefs may have been placed at the very center of the capital – in and adjoining the central court – because the order of compounds in the capital already existed, so they took up some of the empty space that was the courtyard in front of the king's palace. Their placement in the center might also demonstrate their connection to the kabaka: the keeper of the king's twin figure and the prime minister ruled with the king. The lubaale shrines in the courtyard asserted the importance of lubaale worship in the kingdom; their autonomy from the king was constantly asserted in the well-defined, visible presents sent by kings to the lubaale worship centers. Whatever the explanation of the spatial distinctions of old power and new power in the capital, they reveal a practice in the distant past of placing potentially competitive forces in interaction with each other at the heart of the kingdom.

One further innovation brought the capital to its form in Ssuna's time. In the mid-eighteenth century, Kabaka Mawanda linked particular territories and the chiefs of those territories to places in the center of the kingdom in an attempt to quell the roiling conflict that had arisen as the kingdom expanded. One hundred years earlier, Kabaka Mutebi had added the province of Busujju and Kabaka Kateregga had added the province of Butambala, so attaching named territories to the kingdom was not new. Mawanda successfully took the chiefships of Bulemeezi, Kyaddondo, and Kyaggwe away from clan leaders and gave them to his own designees. More fundamentally, he created a new form of prestige and a visible sign of it by establishing ‘headquarters’ for those provinces and also for Ssingo, which had been added to the kingdom by Kabaka Mutebi. He brought the chief mugema into his new conceptual framework for the kingdom by defining the mugema's territory, Busiro, as a province.Footnote 70 Together, these actions gave the polity its familiar form, with straight roads leading out from the headquarters of each province and converging on the capital, and its two streets leading to the courtyard of the king.

CONCLUSION

A careful examination of Apolo Kaggwa's map of Kabaka Ssuna's nineteenth-century capital suggests important dimensions of the history of power in the region that became Buganda. The spatial ordering of the capital suggests that people modeled kingship on chiefship, and that clans collaborated in the creation of a kind of kingship that allowed them to retain some kind of control over their king. Heterarchical strategies became part of a hierarchical polity. The streams of flowing water that separated the king's power from that of royal women, the chief mugema, and the Mbajwe cult leader katambala, and the presence of 292 named chiefships in the capital, demonstrate that people had made their rulers accountable not by centralizing power but by keeping things complicated. The long history visible in the map of Buganda's capital reveals compromise and accommodation. At points of historical conflict, new holders of power joined older ones, but the older ones remained.