In an article published in 1981, Frederick Cooper asked ‘what did Islam mean to slaves? Did they develop among themselves or in conjunction with others a view of Islam that rejected their own subordination?’ In his answer, Cooper argued that in the case of the largely Muslim societies on the coast of East Africa where he carried out his research, slaves used Islam to further their own interests. ‘Just as the slaveholders’ control heavily depended on their ability to define cultural values and analyze their position in terms of a divine order’, Cooper wrote, ‘slaves challenged their owners on the same grounds.’Footnote 1 The logic of this argument is impeccable; surely the common Muslim beliefs and practices of slaves and masters made ethical discourse an important site at which the relations and struggles of slavery took place.Footnote 2 Just as in the slaveholding societies of the Atlantic world, where the polyvalent messages of Christianity served to buttress both ideologies of slavery as well as resistance to them,Footnote 3 African Muslims found in Islam principles that served different social standpoints. Slavery is licit in Islamic law; yet intra-Muslim fellowship is among the most important religious values in Islamic ethics. The problem with this line of analysis, as Cooper admitted, is that it was not based on much empirical evidence of actual slave voices.Footnote 4

In this article, I present direct testimony of interactions between Muslim slaves and their masters in West Africa using a series of Arabic letters written by literate Muslim slaves in the nineteenth century. In this correspondence, I show how a small number of literate Muslim slaves, acting as commercial agents in their master's trading network, made appeals to their own piety and morality as Muslims in negotiations with their masters. But the goal of these slaves – at least insofar as we have access to it in the letters that they wrote – was to improve their individual positions and status within their master's family and business structures. There is no evidence that their knowledge of Islam, which for one slave in particular was quite considerable, led them to challenge their master, or to offer alternative understandings of Islam that derived from their social position as slaves. Instead, slaves used their Muslim identity as a means of claiming the position of a trusted client in their master's enterprise. Rather than dispute their inferior status as slaves, they insisted that their fidelity to their master's commands were ensured by their moral character as Muslims.

We must understand these arguments as rhetorical strategies in negotiations with masters meant to accomplish particular ends such as individual social promotion and ultimately manumission. However, Cooper argued that: ‘[T]he slaves’ acquisition of religious knowledge and cultural familiarity could undermine the basis of their inferiority.’Footnote 5 In none of the letters used in this article is there any challenge made by slaves to the fundamental inferiority of their status. There are no claims by slaves to equality with noble Muslims in ritual practice, or in forms of dress, as Cooper suggested in his discussion of slaves’ interpretations of Islam. When slaves wrote in ways that emphasized their submission to their master's orders, and acceptance of their own low status as slaves, they were not interpreting Islam in ways that were obviously different from their masters. They struggled to improve their lives, but they did so within an Islamic framework that was accepted by both masters and slaves. What the letters used in this article make clear is that there are many answers to Cooper's question about what Islam meant to slaves, and that we must account for those Muslim slave voices that did not challenge the fundamental inequality of their status as slaves in direct ways.

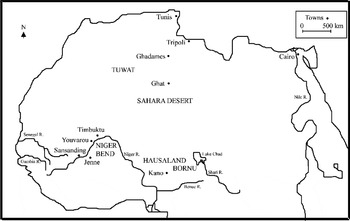

The correspondence that I will discuss was produced by members of a commercial network that operated in the Central Sahara and the Niger Bend region of the West African Sahel from a base in the town of Timbuktu, in present-day Mali. The head of the network was a man originally from the northern Saharan oasis town of Ghadames,Footnote 6 and a significant part of his business involved sending gold, ostrich feathers, cloth, and slaves north across the Sahara. In addition, he engaged in more local commercial circuits of salt, foodstuffs, and cloth that were exchanged along the desert edge in West Africa.Footnote 7 The merchant's name was ʿĪsā b. Aḥmayd b. Muḥammad b. Mūsā b. Muʿizz al-Shaʿwānī al-Ghadāmisī. He established a household in Timbuktu in the 1850s, if not earlier,Footnote 8 and he died in the early 1880s, after which some of his sons began to direct the business.Footnote 9 In West African markets outside of Timbuktu, the trade itself was largely carried out by slaves belonging to ʿĪsā b. Aḥmayd. The two most important slaves who acted as commercial agents for their master, and who wrote and received letters, were named Anjay ʿĪsā and Ṣanbu ʿĪsā. Where these two men were born, or grew up, is not known.Footnote 10 The letters are useful in providing some biographical information, but they are mostly about commercial, rather than personal, matters. What the letters do allow us to reconstruct are some of the direct communication between a master and his slaves. As I will argue, these are wonderfully rich and highly unusual sources that give us a glimpse of the rhetoric used by some Muslim slaves in precolonial Africa.Footnote 11

Fig. 1. Map of North and West Africa in the nineteenth century.

Because most of the letters are not dated, it is often impossible to be sure of the precise historical context in which they were written. But those letters that do carry dates provide a range for this correspondence of between 1854 and 1900. As such, they were written in the decades immediately preceding European colonial conquest. Letters were sent to and from Timbuktu and other market towns in the Niger Valley such as Youvarou (Yuwar) and Sansanding (Sinsani). The details of the political situation in this region at that time are beyond the scope of this article. However, it is important to highlight the fact that this was a period of political instability and conflict.Footnote 12 It was only when the French colonial state definitively established itself in the 1890s that a certain amount of security returned to the area. Into this milieu came merchants from the Sahara, who funneled trade goods and slaves north via their entrepôt at Timbuktu to places like Ghadames. From there, traders continued to Tripoli and Tunis on the Mediterranean coast. Although there were other Saharan destinations for merchants, Ghadames was especially important in the late nineteenth century, as it had been for centuries, in part because it was located astride the shortest trans-Saharan route to the Mediterranean.Footnote 13 Colonial conquest brought these economic circuits to an end by largely – although not entirely – redirecting trade to European-controlled Atlantic networks.

MUSLIM SLAVES AND KNOWLEDGE OF ISLAM

Direct evidence of the religious thought of any group of slaves in sub-Saharan Africa before the advent of European colonial rule is difficult to find. For Muslim slaves, the first question that must be addressed is the extent to which enslaved people in Muslim African societies embraced Islam. Widely-held slaveholder ideology in Muslim Africa justified the practice of slavery as a punishment for unbelief and a rejection of Islam on the part of those enslaved. Although masters were required to give their slaves religious instruction that would bring them into the fold of Islam, slaves were often represented as the antithesis of Muslims, people who lacked personal honor and behaved in licentious ways.Footnote 14 This is perhaps one reason why the aspiration for Islamic education is frequently invoked in the life stories of ex-slaves and their descendants in the West African Sahel.Footnote 15 Allen Fischer and Humphrey Fischer argued in their widely cited overview of slavery and Islam in West Africa that masters often neglected their duty under Islamic law to educate their slaves in religious matters.Footnote 16

But there is evidence that not all slaves were denied access to religious instruction; some even achieved literacy in Arabic. A Muslim ex-slave in colonial Tanganyika named Rashid bin Hassani described the religious education that he received in the nineteenth century by saying that he had been circumcised by his master and ‘taught the Mohammedan religion and to read the Koran’.Footnote 17 Cooper made the argument that in nineteenth-century East Africa, many masters took their responsibility to teach Islam to their slaves seriously.Footnote 18 The reason that Muslim slaveholders were expected to offer their slaves religious instruction is because the institution of slavery was justified as a means of spreading Islam. In teaching their slaves how to be Muslims, slaveholders acted to wean them away from non-Muslim customs that had made them, from the Muslim point of view, legitimate targets of enslavement in the first place.

The education of slaves is a topic that comes up regularly in the extensive Arabic legal literature written in West Africa during the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries by local Muslim scholars. In the tradition of the Kunta, a prominent Arabophone lineage active in Saharan commerce in what is today Mauritania, northern Mali, and southern Algeria, slaveholders were instructed that Islamization of slaves was very important for their own salvation. The great Kunta scholar and Sufi shaykh Sīdi al-Mukhtār al-Kuntī (d. 1811) asserted that even force was a legitimate and necessary means of making slaves practice Islam.

It is not sufficient just to propagate [Islam], but instead it is necessary that [the slaveholder] force them [to become Muslims] whether they are non-believers (majūs) or idolaters (wathaniyīn). They should be forced by beatings and threats, without going so far as killing them. If [the slave] is led to Islam, and he is corrected in the recitation of the Muslim credo, then it is also necessary to force them to learn their religion including issues of purity, prayer, and fasting. He should not speak to them about work during the period of learning the [essential] texts.Footnote 19

A similar argument was made by another important Kunta scholar named Shaykh Bāy al-Kuntī (d. 1929), who claimed that there was scholarly unanimity on this issue. The slave must ‘know what God permits and what He forbids’, because in this way he will be able ‘to claim the rights that God has put in place for him.’Footnote 20 In the Kunta tradition, there was a didactic poem which set out the requirements of educating slaves:

And preserve the right of the slave; for indeed

He is affirmed in matters of religion; so be patient and steadfast

And teach them the matter of the creeds; for indeed

It is incumbent upon you; so lead them to the well

And do not disregard them as if they were livestock; for indeed

They are human beings …Footnote 21

For those who insisted upon the duty of educating slaves, the analogy was usually made to the education of women. Shaykh Bāy invoked the verse in the Qur'an which made heads of household responsible for the religious practice of all of their dependants.Footnote 22

An educated, Muslim slave was expected to marry. According to Shaykh Bāy, marriage was a means for slaves to live in dignified ways.Footnote 23 The duty of the master to educate his slaves and authorize their marriages bound slaves to their masters in ways that were understood to be permanent. Even after manumission, a former slave's behavior and moral being were, in part, the responsibility of his master.Footnote 24 Freed slaves had to maintain a relationship with their former master in a form of clientship called walāʾ. According to Shaykh Bāy, ‘he who makes claims upon he who is not his father or depends on those who are not his masters, is cursed by God, the angels and the people together.’Footnote 25 Such slaveholder ideology provided a template of social belonging for Muslim slaves, even as they sought manumission. The achievement of autonomous social space did not, in most cases, mean independence from their master's patronage.Footnote 26

Anjay ʿĪsā, one of ʿĪsā b. Aḥmayd's principal slave agents, was both literate in Arabic and achieved some level of Islamic learning. When Anjay died in Timbuktu at the turn of the twentieth century, he was the owner of a number of Islamic books on the subjects of Islamic law, Arabic grammar, and devotional literature. The executers of his property after he died listed thirteen books found in his house.Footnote 27

1. A copy of the Qurʾān;

2. [Ibrāhīm b. Marʿī al-Shabrakhītī's (d. 1697)], Sharḥ al-Shabrakhītī li-Mukhtaṣar Khalīl,Footnote 28 [a commentary on the most important handbook of Mālikī jurisprudence, the Mukhtaṣar by Isḥāq b. Khalīl (d. 1374)];

3. An unnamed work of tafsīr [Qurʾānic exegesis];

4. A book by Shihāb al-Dīn [presumably Aḥmad b. Muḥammad b. ʿUmar al-Khafājī's (d. 1659), Nasīm al-riyāḍ fī sharḥ shifāʾ al-Qāḍī ʿIyāḍ,Footnote 29 a commentary on the popular biography of the Prophet Muḥammad by the Andalusian al-Qādī ʿIyāḍ (d.1149)];

5. An unnamed commentary on Khalīl b. Isḥāq's handbook of Mālikī jurisprudence;

6. Part of a dictionary;

7. A book of Mālikī fatwas [legal opinions];

8. A book by al-Ḥaṭṭābī [either Muḥammad b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Ṭarābulsī (known as Ḥaṭṭāb) (d. 1540–1), who wrote commentaries and hashias on Khalīl's Mukhtaṣar, or more likely from the pairing after it, Ḥamd b. Muḥammad b. Ibrāhīm al-Khaṭṭābī's (d. 996), Bayān iʿghāz al-Qurʾān,Footnote 30 on the incomparability of the Qurʾān to anything else]; and then [ʿAbd al-Ghanī] al-Nābulsī's [d. 1731] Badīʿa,Footnote 31 [on marvels];

9. A book called the Tahdhīb al-ustādh [probably Khalaf b. Abī ʾl-Qāsim Muḥammad al-Barādhiʿī's (d. 1039), al-Tahdhīb fī ikhtiṣār al-Mudawwana al-kubrā or Tahdhīb masāʾil al-Mudawwana,Footnote 32 which is a commentary on Saḥnūn's (d. 854) Mudawwana [a foundational work of Mālikī law];

10. Al-Qasṭallānī's [d. 1517], Irshād al-sārī fī sharḥ Bukhārī, [a commentary on al-Bukhārī's hadith collection];

11. A book on Arabic grammar;

12. A book on zakāt [Islamic alms-giving] in Khalīl's handbook;

13. Multiple tafsīrs [Qurʾānic exegeses].

By the time of his death, Anjay had been manumitted.Footnote 33 The fact that a recently freed slave would possess these texts suggests that he had achieved a level of education and sophistication that would have exceeded that of many free-born people in Timbuktu at the time. Understanding how Anjay and his fellow slaves used their Islamic education in interactions with masters and former masters is the task of the remainder of this article.

SLAVES AS COMMERCIAL AGENTS

Certain subgroups of slaves were more likely to achieve at least modest levels of Islamic education than others. Broadly speaking, those slaves who lived in the households of their masters, or who were born into slaveholding societies, shared their masters’ religious culture. But beyond this generalization, there were also positions in Muslim parts of Africa for trusted slaves in political, military, and commercial spheres. Sean Stilwell has described a group of elite royal slaves in the nineteenth-century Sokoto Caliphate who were given Islamic education and were expected to practice Islam.Footnote 34 The situation in Sokoto is analogous to more elaborate uses of Muslim slaves in government and the military in North Africa. According to Mohammed Ennaji, Islamic education was also an important component of the training of royal slaves in Morocco.Footnote 35 The employment of Muslim slaves as soldiers is also well attested.Footnote 36 But it is perhaps in commerce that the role of educated Muslim slaves was most developed in Africa.Footnote 37

It was not an uncommon practice in long-distance trade networks in Africa for slaves to be employed as commercial agents. In nineteenth-century East Africa, enslaved commercial agents called mafundi (sing. fundi) often led caravans from the coast to the interior and conducted themselves as independent entrepreneurs while on these missions.Footnote 38 Similar patterns have been described in North, West and Central Africa.Footnote 39 According to Charles Monteil, who carried out research with merchants based in Jenne (Djenné) on the Middle Niger in the 1930s, traders ‘very often confide their biggest business to slaves or freed slaves who are better agents than their relatives’.Footnote 40 We know that slaves were also important in the Saharan trade. In James Richardson's account of his visit to Ghadames in the 1840s, he described merchants who sent slaves to Timbuktu in order to conduct business.Footnote 41 The Tunisian traveler Muḥammad al-Ḥashāʾshī reported in his narrative of his Saharan travels in the 1890s that among the 19 merchants from Ghadames resident in Kano, one was a ‘black slave’ named ʿAlī b. Barka, and two were freed slaves named Hammād and Zabarma.Footnote 42

The importance of slavery to the functioning of Saharan and sub-Saharan trade was directly related to the insecurity and unpredictability of carrying out commerce over such large distances in territories not controlled by any hegemonic political authority. Ralph Austen and Dennis Cordell have argued that the absence of formal legal safeguards provided an incentive for Saharan trade networks to incorporate as many participants as possible: ‘Instead of formal legal arrangements, the ties between participants in the various zones of the caravan trading system seem to have been based mainly upon combinations of kinship, clientage, and slavery.’ According to Austen and Cordell, such arrangements could ‘withstand the uncertainties of the trade, and they also incorporated not only major partners, but also lesser collaborators, such as camel attendants. They also sustained ties between the desert system and expanding merchant networks extending farther south across the Sudan into the forest.’Footnote 43 These principles of cross-cultural trade have long been recognized.Footnote 44 European-centered commercial networks also relied on social bonds that were both horizontal and vertical, tying as many people as possible into patron-client structures. This ‘density of relations’ mitigated the risks of such activities.Footnote 45

For slaves to be effective commercial agents, they needed incentives that would bind them to their masters’ businesses. One means of encouraging the loyalty of slave agents was the potential path to manumission that such service could provide. Another possibility was for profits to be shared between master and slave agent in some form of partnership, as in the framework of commenda trade practices in the medieval and early-modern Mediterranean and Indian Ocean. In the commenda system, which is called muḍāraba or qirāḍ in the Muslim world, agents entered into contractual relations with patrons who provided goods or capital to be traded in distant markets. The agent received a fixed percentage of the profits in return for his labor.Footnote 46 A third type of relationship meant to ensure loyalty was an arrangement where the slave was able to trade on the side on his or her own account. This is how Olaudah Equiano earned the money necessary to buy his freedom in the eighteenth-century Caribbean;Footnote 47 it has also been described by the descendants of slave agents in the Ghadames network in Hausaland in West Africa.Footnote 48 In the letters written by, and addressed to, the slaves Anjay ʿĪsā and Ṣanbu ʿĪsa, it is clear that all three types of incentives motivated their actions.

The letters reveal that slaves were often considered to be the most knowledgeable people about trade, and those likely to be able to pass along commercial intelligence about prices, market conditions, and the security of roads. In a letter written from the Saharan oasis of Ghat in 1884 by a man named al-Mukhtār b. al-Ḥājj ʿAlī b. al-Ḥājj Muḥammad ʿAmmūsh al-Balīlī, he addressed Ṣanbu and Anjay, both described as ‘slaves of ʿĪsā’. Announcing that he had received no news from ʿĪsā b. Aḥmayd's son Aḥmad al-Bakkāy, he wrote: ‘The reason for this letter is because Muḥammad b. ʿĪsā and I have come to Ghat and we were told that if we want to know what is happening in Timbuktu, we must correspond with the slaves in order to gather news. How can we respond to you unless you send us all the news?’ The letter-writer continued by chastising Ṣanbu for failing to write to him: ‘And you, Ṣanbu, this is because of your failings! You know everything, and now you are the equivalent of our father. Indeed you have al-Ḥājj Muḥammad there with you in Timbuktu who used to overwhelm us with news, yet eight years have now passed and we have not had a letter in response from al-Bakkāy.’ The letter also sought personal updates on people in Timbuktu in the larger expatriate Ghadames household to which Ṣanbu and Anjay were attached.

You must absolutely give us all the news from these people, and that includes the news of the servant (waṣīf) al-Ḥājj, may God help and strengthen him, and a response putting together the news of our father, and what has become of al-Bakkāy, and what has happened with Bana-kayār and Bou Naʿām in the house. Give us all the news about any matter which might materialize for our brothers in Timbuktu and we will respond accordingly.Footnote 49

Such letters make clear that this stratum of slaves was crucial to the functioning of the larger trade network, as well as a feature of the households of the merchants.

Slaves filled the role of trusted couriers, especially in the trade with the Middle Niger. In one letter, a merchant from the Middle Niger wrote that he was unable to find people whom he could trust to carry gold to Timbuktu. For this reason, he described how he had given his gold to two slaves belonging to a merchant from Tuwat (a Saharan oasis complex in present-day southern Algeria): ‘You will find the gold karats with Bilāl. There are 100 [karats of gold], which I told you before were in the possession of Musi. Now they are in the hands of Bilāl. Both [Bilāl and Musi] are slaves of Muḥammad Daʿaysha al-Tuwātī. I kept them with me until now only because I could not find anybody whom I could trust to take them.’Footnote 50 Examples such as these indicate that some slaves were held in high confidence, even when they belonged to other owners.Footnote 51 A letter of introduction carried by Anjay and written by his master is extant. It is addressed to a man named Ubb Saʿīd, who ʿĪsā b. Aḥmayd calls ‘his brother in Almighty God’, and asks that Anjay be well treated. The brief letter states: ‘My slave (ghulām) Anjay has come to you so please ensure that no one treats him unjustly. I have ordered him to stay there and you will see that he is of the highest intelligence …’Footnote 52

SLAVE RESPECT AND SOCIAL AUTONOMY

One of the most striking features of the letters written to Anjay and Ṣanbu is the degree of rhetorical respect accorded to them by those they corresponded with. This is especially the case in letters addressed to Anjay. For example, in one letter written to Anjay by his master, it begins: ‘from ʿĪsā b. Aḥmayd, with full and generous greetings (bi-ʾl-salām al-atamm al-akram) to his slave (ghulām) Anjay …’Footnote 53 After ʿĪsā b. Aḥmayd died in the early 1880s, his sons became Anjay's masters.Footnote 54 The son who ran the family trading business in Timbuktu was named Aḥmad al-Bakkāy. In many of the letters that he wrote to Anjay in the 1880s and 1890s, there is the repeated usage of the following salutary formula: ‘From Aḥmad al-Bakkāy b. ʿĪsā b. Aḥmayd to his brother and friend, and (only) then his slave (ghulām) Anjay, peace be upon you and upon your family.’Footnote 55 It is possible that they were biological half-brothers, sons of ʿĪsā b. Aḥmayd by different mothers, one free and the other enslaved. But even if they were not, the invocation of brotherhood and friendship between a master and his slave suggests that the relationship between the two men was familiar and respectful, almost certainly born out of shared lives and experiences.

The language used in the greetings is more familiar – even fawning – in some of the letters exchanged between Anjay and his business associates in the Niger Bend region. One letter addressed to Anjay begins, ‘Full greetings and general respects from Bāba b. al-Shaykh Kumu to his beloved, and his brother, Anjay…’Footnote 56 In another letter – this one written by another slave – Anjay is represented as a paragon of virtue.

From the beloved and respectful brother al-Barka, slave of Shaʿbān the cutler, to his beloved, excellent, honored brother – the most blessed (al-abrak), the most refined (al-adīb), the most distinguished (al-nabīh), the most highly esteemed (al-aʿazz), he who has surpassed his mates, a shining light for the people of his time; may God help us and him – Unghī [Anjay] ʿĪsā. Peace be upon you and everyone with you.Footnote 57

The language employed in praising Anjay was certainly drawn from existing models of deference and respect in commercial letters, but it is remarkable to find these terms used to address a person of slave status. It is important to understand that Anjay was on intimate terms with his master and his master's sons. Letter writers who were not part of ʿĪsā b. Aḥmayd's larger household had their own, usually commercial, interest in offering respectful greetings to Anjay as a member of ʿĪsā's household and trading network.Footnote 58 In either case, it is clear that Anjay's position as a slave did not make him a person undeserving of rhetorical honor.Footnote 59

Ṣanbu and Anjay were both married, and had households in Timbuktu. In one letter written by Ṣanbu and addressed to Anjay in Timbuktu, he asks that a message be passed along to his wife named Kani, and that his greetings be conveyed to two brothers named Baniya and ʿUthmān.Footnote 60 In another letter it is mentioned that Anjay was married to a woman named Bintu.Footnote 61 The ability to establish and support separate households suggests that these slaves had achieved an unusual level of autonomy and economic viability for the nineteenth-century Niger Bend. Yet even in letters written by slaves, the authors consistently provided information about their social status and the person to whom they belonged. Al-Barka, for example, identified himself in this way. So did Anjay and Ṣanbu. That slaves would acknowledge their status in letters exchanged with their masters is not surprising. But slaves also identified themselves according to their social status in letters that they exchanged among themselves. Part of the explanation for this is that scribes wrote many of the letters.Footnote 62 But the reason that slave status was marked in this correspondence goes beyond masters’ (or scribes’) efforts to maintain and reinscribe social status and hierarchy within the commercial network. It also seems to have served the interests of the slaves to some extent, by identifying them with this relatively prosperous trans-Saharan network.

Anjay and Ṣanbu's status as ghulām marked them off from first generation slaves and allowed them to make claims on their master's family as junior clients, especially if they could anticipate eventual manumission. Other terms such as ʿabd (pl. ʿabīd), which is the main Arabic word for ‘slave’, are used in the letters to refer to slaves undertaking transportation labor such as porters. For example, in one letter, the price of the porterage is listed at 2,000 cowries.Footnote 63 Other terms such as ama, (slave girl) and khādim (servant) are common when discussing the prices, availability, and purchase of slaves in West African slave markets.Footnote 64 The term ghulām can be an ambiguous word, since its base meaning is young man or boy.Footnote 65 However, in this case we know from other information in the letters that Anjay and Ṣanbu were indeed slaves. Ghulām signals a level of acculturation into the master's society and culture. It can be equated with second generation slaves, or even with groups of people called slaves in many West African societies who, by virtue of having been born into the status of slavery, were not supposed to be sold.Footnote 66 In their letters, Ṣanbu or Anjay show no desire to sever the social bonds that tied them to the larger family of their master ʿĪsā. Instead, they sought social promotion as junior clients within their existing social network. The success of these strategies depended on convincing their master that he had a moral duty to behave as a good patron and good Muslim vis-à-vis his slaves.

SLAVE VOICES

Most of the extant letters written by slaves are concerned with commercial matters. They are often detailed accounts of transactions, prices, and market conditions. One example is a letter written by Ṣanbu, to his master ʿĪsā on 16 June 1864 from Sansanding: ‘The reason for this letter is that ʿUthmānFootnote 67 has left twenty units of grain with Yarūsāgh… I sent it on [25 January 1864], but we heard that he was not able to go that way [because of insecurity] so he instead headed for Jenne, which he reached without trouble.’ Ṣanbu then began his accounting:

I also sold nine blocks of water-damaged salt for 64,000 cowries, and I gave the money in trust to the commercial house (dār). I sold four blocks of salt for 24,000 cowries, and I bought two long strips of cloth for 26,000 cowries. I made four blankets from each one, and the thread and the tailoring to do this cost 10,000 cowries. I bought the 20 units of grain that I sent with Yarūsāgh for a value of 17 blocks of salt. This accounts for thirty blocks. After that, I sold 48 blocks for 120 mithqāls of gold,Footnote 68 which means that each block was exchanged for 2 1/2 mithqāls of gold. After that I bought 50 units of grain. This is all that I have right now, in addition to the remaining value of the salt and the cowries.

Ṣanbu also passed along commercial news demanded by ʿĪsā.

You asked about the prices of commodities in Sansanding: One block of salt sells for two mithqāls of gold, or 10,000 cowries. Labor is 2,700 cowries. Grain is 400 cowries for a sack (qashāsha). There are no slaves (khadīm) that can be bought profitably here. Cotton strips are cheap, but honey is expensive. Shea butter is expensive, baobab flower is not available, and tamarind is expensive. Grain is expensive throughout the country but there are no people who are more dishonest than the people of Sansanding. They gouge prices all the time because they do not believe in God or shaykhs.Footnote 69

The precision of the commercial detail found in this letter is a common feature of much of the correspondence, and it is in no way unique to letters written by slaves.Footnote 70 Nonetheless, this example gives an idea of how important it was for Ṣanbu to demonstrate that he had acted scrupulously in carrying out his master's commission.

The diligence of Ṣanbu's accounting was meant to avoid any disputes or accusations of dishonesty by his master. Conflicts among trading partners, or between agents and investors, were not uncommon. When slaves were blamed by their masters for acting inappropriately, the stakes could be quite high. In one case, Anjay was accused by his master of having disobeyed orders to return to Timbuktu, and instead remaining in the town of Youvarou. In reply, Anjay wrote a long letter defending his actions and seeking to mollify ʿĪsā b. Aḥmayd. Anjay began by denying that he had acted improperly: ‘You said in the two letters that you had ordered me to return to you and not to remain here. I have not deviated from this for even one day. I do not disobey your commands and your orders because I do not wish to disobey them even for a single moment.’Footnote 71 Claiming that the ‘delay was caused by circumstances, not my personal choice’, Anjay went on to argue that ‘there is no quick business in the town of Youvarou. Salt is not sold quickly and gold is not found easily.’ Further, Anjay wrote that ‘you are absent and I am present here. It is those who are here on the ground who can see and know what those who are not here cannot see and cannot possibly know. This is the difference between you and me. I have no personal business in remaining here other than your service and business.’ It seems likely that the master suspected that Anjay was delaying his return to Timbuktu because of personal business that Anjay was undertaking on the side, as was common among traders of this sort.

It is of course possible that Anjay did have his own business on the side that detained him in Youvarou. But in the rhetoric of this letter, Anjay claimed an authority based on his trustworthiness and his morality, which he clearly understood to be among the most important Islamic ethical values of commerce.Footnote 72 Anjay made the argument that the situation in Youvarou was dangerous for all traders, and that he was unable to carry out his master's commission easily:

Since we have come to the town of Youvarou not one of us has slept securely in our houses; instead we have spent our nights beside the river guarding our goods from our enemies. None of [the traders] who are in the town of Youvarou sleep in their houses because they must spend their nights beside the river. We have spent three consecutive nights outside in this way. In these conditions, the heart does not rest peacefully. It is better to do that than to do something else.

In an effort to assuage his master, Anjay wrote that he had ‘asked Saddi to delay his trip here for a few days so that I could put together a little bit of gold and send it to you with him, but he said that he could not stay here any longer. God willing, you will see all the gold that I acquired in these last days.’

So far, the letter reveals only a conflict between Anjay and ʿĪsā over the master's impatience with the amount of time Anjay had taken in completing his business and returning to Timbuktu. Claiming that the delay was caused by political insecurity, Anjay explained why he had been unable to complete his mission. There are many letters that tell similar stories of blocked commercial routes and inauspicious conditions for trade. What makes this letter so interesting is that Anjay included a larger argument about his own status as a slave and as a Muslim. ʿĪsā had accused Anjay of having sold goods on credit, against his orders. Anjay replied that he ‘had sold on credit [but] I did this only for one load (ʿadīla) of tobacco, which I sold for 100,000 cowries on credit. This was a mistake on my part, but it was decreed by God Almighty and I did not do it by my own will.’ Anjay promised that

God willing, I will come to you without further delay. Do not listen to everything that people say to you until you see me, God willing. To you, I am like the mouse that is in the house of the people: He does not abandon these people of the house. You and I are like that. So rest your heart in peace about me.

By invoking divine will repeatedly and suggesting that his relationship with his master was religiously sanctioned, Anjay made claims on his master as a client.Footnote 73 Anjay's argument that he is a ‘mouse in the house of people’ suggests the real thrust of his argument. Although he was a slave, Anjay represented himself as a junior client of ʿĪsā's household and commercial network. Anjay's ability to lay claim to this position was bound up with his master's perception of his loyalty and his Muslim piety, but also quite clearly, with his own subjective experience as a junior member of this extended household and with his own religiosity as a Muslim. He concluded by writing that ‘from me you will see only things that please you, God willing. I swore an oath to God Almighty to never betray you. Even if people tell you that I am stealing your money, I will walk to you on my two feet, God willing. I will walk to you myself and you will do with me what you want. I prefer this to betraying you.’ This is not the language of resistance, or even contested meanings of particular Islamic ideas or patron-client structures.Footnote 74 Instead, it is a claim to the religiously-sanctioned role of a slave as a junior member of his master's family. It is also clearly a way for Anjay to remind his master about how a patron should behave.

Anjay's claims upon his master were not made from a position of strength. Despite being a Muslim ghulām, Anjay remained vulnerable to the whims of his master. A ghulām slave's vulnerability is evident in a letter addressed to ʿĪsā b. Aḥmayd in Timbuktu by a man named ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Yamina, in which the writer explained that he was sending him one of his slaves named Kunma. When he arrived, the letter explained, Kunma was to be sold to the merchants of Tuwat because ‘he will tell the secrets of the master about his children.’Footnote 75 Presumably, Kunma did not know about his fate. That he could be sold to Saharan merchants from Tuwat because he posed a potential threat to his master's honor, offers a stark reminder of how precarious the position of even a relatively higher status slave could be.

After ʿĪsā b. Aḥmayd died in the early 1880s, there was a continuing relationship between Anjay and the sons of ʿĪsā. I have already quoted the salutary line in a letter from one of ʿĪsā's sons named Aḥmad al-Bakkāy, who referred to Anjay as his ‘brother’ and only then as ‘the slave of his father’.Footnote 76 One of ʿĪsā's other sons named al-Khalīfa referred to Anjay as his ‘father’ in one letter.Footnote 77 It is clear from this correspondence that Anjay was held in some regard by the sons of ʿĪsā. He was older than they were and had almost certainly been a member of their household as they grew up. The extent of their respect can be gauged from the fact that Aḥmad al-Bakkāy sent his own son to study in a Qur’anic school with Shaykh Bāba b. Sinṭāwu, who had apparently also taught Aḥmad al-Bakkāy himself as a child. Aḥmad al-Bakkāy told Anjay ‘to stand by the side [of his son] as much as possible, to hit him and imprison him, to do what is possible and impossible until he obeys you and obeys God’.Footnote 78 By this point in his life, Anjay was a senior member of the family in terms of his age. Even if he was a slave – or perhaps a former slave by now – he could still be expected to play the role of an adult in disciplining a child.

I do not know when Anjay was manumitted. It did not occur at ʿĪsā's death, as Anjay surely had hoped. But it is clear from the letters sent to Anjay after his master's death that the manumission did eventually happen.Footnote 79 Even so, the language of slavery continued to be invoked in correspondence with Anjay. For example, in a letter written to Anjay by someone named Muḥammad b. Ṭālib, the rhetorical use of the language of social hierarchy and slave inferiority was made as a rebuke to Anjay for not having sent a response to a previous letter.

I saw al-Khalīfa and I did not hear anything from him, nor did he give me a letter from you. I did not write a letter to Aḥmad Bāba but instead, I wrote to you with all the news about what happened. So, why did you not write back to me and send [the letter] with him? If I was to become a slave to you, and you would write me a letter telling me good things and bad things, what would I do for you? What would you hear from me? What would reach you from me? If sending al-Khalīfa was enough I would not have written a letter to you telling you all that happened. I raised you [in status] and now you abase me …Footnote 80

The last line of the above passage appears to refer to Anjay's manumission. The stain of slavery remained, even as the letter writer sought news from Anjay, now a free client of the family of his former master.

CONCLUSION

Fragmentary though the evidence presented in this article is, it does suggest some of the complex ways that some slaves who were involved in commerce used Islamic idioms to negotiate the social webs that constituted their lives. Anjay and Ṣanbu were both slaves, but they clearly identified themselves as Muslims. In their dealings with their master – whether in detailed accounting of transactions or in disputes over obedience and dishonesty – they made their own morality and honesty into explicit arguments about fidelity to their masters. The evidence of the letters suggests that Anjay's ethics in particular were widely acknowledged by others within the social and commercial world that he inhabited. Letter-writers consistently praised his uprightness and moral behavior, even if his masters always reiterated his status as their slave.

Cooper argued that Muslim slaves in coastal East Africa sought inclusion with elite, free Muslims in Islamic rituals such as prayer, and that they demanded religious equality in accordance with their level of Islamic knowledge and piety, rather than based on social status or origin.Footnote 81 Jonathon Glassman has termed these efforts by slaves and people of slave descent to be recognized as full members of Muslims communities’ ‘struggles for Swahili citizenship’. Like Cooper, Glassman argued that although slaves generally accepted the ‘patriarchal and Islamic idioms that gave shape to public rituals, they did not necessarily share the dominant interpretation of them’.Footnote 82 Much of the literature on slavery in Muslim parts of Africa has followed this line of interpretation, highlighting the ideological tension between the proselytizing ideals of Islam and the difficulty slaves faced in gaining recognition as Muslims.

The evidence presented in this article suggests that Muslim slaves also made arguments when addressing their masters using the rhetoric of slaveholder patronage and social hierarchy. In the letters that Anjay and Ṣanbu wrote to their master, it was their ability to embody Islam as good Muslims that allowed them to enjoy a degree of social autonomy as junior members of their master's trading enterprise. Certainly this was not the only possible way in which Muslim slaves could invoke Islam. But the claims to equality as Muslims that are so prominent in Africanist literature often capture moments of significant social change and social mobility for slaves. This was clearly the case in the second half of the nineteenth century on the East African coast, just as it was in the early twentieth century in the West African Sahel. Contests over the ability of people of slave descent to practice Islamic rituals equally, or to follow noble sumptuary practices,Footnote 83 reflect these socially dynamic circumstances. The Muslim slaves involved in commerce in the Sahara and Niger Bend in the second half of the nineteenth century engaged in different kinds of struggles. They had more to gain from retaining their unequal positions within their masters’ networks than in seeking their fortune outside of them. Their arguments to their masters therefore explicitly acknowledged the religious validity of their status as slaves, even as they sought individual manumission as junior members of their masters’ family.