THE BEGINNINGS OF ISLAM IN IGBOLAND

The Igbo territory east of the River Niger is the major ethnic nation in south-eastern Nigeria, the former Eastern Region (Fig. 1). In 1999, Igboland was named the southeast geopolitical zone, comprising Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu, and Imo States.Footnote 1 South-eastern Nigeria generally, and Igboland in particular, have been repeatedly described as a predominantly Christian region.Footnote 2 Only a few years back, the Catholic priest and scholar Columba Nnorom referred to Igboland as one of Africa's homogenous Christian regions.Footnote 3 The Igbo Christian identity at present does not derive from the total absence of other religious groups within it but rather attests to the reality of Nigeria's religious composition, with relatively few members of other faiths (indigenous Igbo religion, Eastern religions, and esoteric religions) in Igboland. Ottenberg sees Igbo religious distinctiveness as a contrast to the rest of the country and remarks: ‘If the north will be Islamic, Igbo country will be Christian.’Footnote 4 With some success in Muslim proselytization from the 1930s to the 1990s, Igboland, while still retaining its profile as Nigeria's most populous Christian region, began after the Nigeria–Biafra War (the Nigerian civil war of 1967–1970) to manifest tendencies indicative of religious heterogeneity, even though this reality is not widely acknowledged by the majority in Igboland. Notwithstanding, the Nigeria–Biafra War was an important catalyst in the development of an indigenous Muslim community in Igboland, having opened the region to a varied range of external influences including those linked to religion.

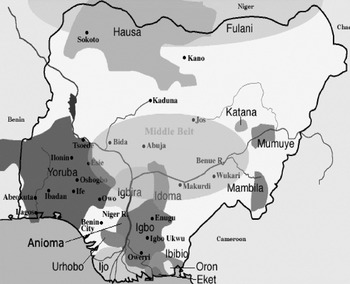

Fig. 1. Map showing some of the ethnic and linguistic groups in Nigeria.

Conversions by the Igbo to Islam began in the late 1930s. In 1937, Garba Oheme, from Enugu Ezike in the old Nsukka Division of northern Igboland, converted to Islam at the age of 29 at Calabar (in the Efik homeland) in the present south-south geopolitical zone;Footnote 5 Muslim leaders in Igboland are unanimous in their acknowledgement of Oheme as the first Igbo convert to Islam.Footnote 6 With Oheme's conversion, the old Nsukka Division became the first part of Igboland to produce an indigenous Muslim. The Division, situated in the extreme north of Igboland, was created in the 1920s, having common boundaries on its northern fringes with the Igala and Okpoto of the Middle Belt, the north-central geopolitical zone, and on its west and south with other Igbo groups (Fig. 2). By location, Nsukka Division is the closest part of Igboland to northern Nigeria, where Islam has been the dominant religion since the jihad of 1804. Unlike their influence on Igbo towns to the south, Christian missions had made no significant impact in the Nsukka area by 1930. The Church Missionary Society, which arrived there in 1933, was preceded only a few years earlier by the Roman Catholic missionaries, with the result that Nsukka Division was decidedly traditional in its mode of worship (and the indigenous Igbo religion was the major religion) when Muslim migrants from northern and western Nigeria began to settle there from the 1920s. Most village elders in Enugu Ezike and Ibagwa very quickly recalled during interviews that Islam was the first foreign religion to which they were exposed, with the arrival of Nupe, Hausa, and Yoruba Muslim traders – the Nupe and Hausa migrating southwards as a result of the colonial wars of conquest in the territory of the Sokoto Caliphate, which then encompassed much of northern Nigeria and parts of the north-central geopolitical zone. Only a few people were reported to have converted to Christianity in the environs of Enugu Ezike and Ibagwa before 1930.Footnote 7

The introduction of Islam in the old Nsukka Division was more likely to occur than in other parts of Igboland, because of its closeness to northern Nigeria; yet it took considerable time before Islamic worship actually developed in the area. By 1967, when the Nigeria–Biafra War started, few other parts of Igboland had gained Muslim converts, the main towns involved being Owerri, Abakaliki, and Enohia. Enohia had the largest number of Igbo converts to Islam, following the group conversion of a quarter of the village in 1958, organized by Sheikh Ibrahim Nwagui.Footnote 8 The entire Igbo Muslim population in 1967, scattered in just three Divisions – Nsukka, Owerri, and Abakaliki – was estimated to be fewer than two hundred.Footnote 9 With concerted efforts after the Nigeria–Biafra War in 1970, from without and within Nigeria, Igbo converts to Islam grew in number. Igbo towns that gained Muslim indigenes in the decade after the civil war were Mbaise, Enugu, Awgu, Umuahia, Orlu, and Awka; the presence of Muslim soldiers of the Nigerian army contributed to the extension of Islam in these places. By 1990, the Igbo Muslim population was estimated to number about ten thousand, out of the entire Igbo population of more than sixteen million.Footnote 10 This figure, regarded more as a bold projection than the reality,Footnote 11 still indicates a modest but significant progress in the face of ‘almost total Christianity in Igboland’ and despite the antagonism to Islam from Christians and followers of Igbo indigenous religion.Footnote 12

Fig. 2. The Igbo homeland in Nigeria, showing the study location east of the River Niger.

Until 1990, conversions to Islam among the Igbo derived from the interplay of internal and external factors whose lines of demarcation were in some cases blurred. These factors include the genuine spiritual quest and conviction that Islam is the appropriate way to God; the recognition of Islam as a universal religion; perceived divine influence through dreams and revelations; mixed religious marriages; the desire for integration within established Muslim financial and political networks, which was heightened by the political and economic marginalization of the Igbo following the Nigeria–Biafra War; dissatisfaction with a previous religious group; the results of habituation; proselytization among the Igbo by Muslims whose other goal, besides gaining converts, is bringing about political unity in the country;Footnote 13 and the pull of financial and other inducements.

This article examines the development of Islamic faith in Igboland since its introduction in the late 1930s. It is concerned with a number of issues, in particular the complex interplay of the religious and ethnic identities of Igbo Muslims, including the mapping of religious values onto ethnic ones. I also discuss recent transformations within the Igbo Muslim community. The disconnection since the 1990s of ethnicity from religion, which is one result of the progress of Islamic education in Igboland, is especially noteworthy. The responses in Igboland to Igbo conversions to Islam and the challenge to Igbo Christian identity and traditional values are also considered.

Conversion has been variously definedFootnote 14 but in the context of this discussion it refers to a change in religion and its underlying culture (or the adoption of a religion by a previously non-religious person). For conversion to take place, social networks with members of the new faith, among other forms of social interactions, are inevitable. In this article, I look at the process of conversion to Islam from either a Christian or an indigenous Igbo religious background, or from a history of no religion until Islam was adopted. The first part of the article deals with the progression of conversion from the time that the decision to convert was taken or when it became obvious that an individual had switched to another religious tradition. This is followed with an examination of the circumstances surrounding the Igbo Muslim community and an assessment of individual and group reactions to conversions and their fundamental bases. Oral data collected from February 2003 until June 2006 from Muslims and non-Muslims of Igbo and other ethnic groups played an important part in this construction. They allowed insight into some of the thoughts and motivations of Igbo converts to Islam and the reactions of other Igbo to their religious change. A few interviews were conducted after 2006. Over forty persons of Igbo, Hausa, Yoruba, Nupe, and Fulani origins, among others, were interviewed in connection with this study. The majority of the interviewees had primary education; quite an impressive number had post secondary school certificates. The few persons with no exposure to formal education had the privilege of Qur'anic education. Interviews were held privately at a convenient location to the interviewees, and follow-up sessions were held in a few cases to clarify issues. Interviewees freely used one of English, Pidgin English, or Igbo to share their knowledge.

INDUCTION INTO ISLAM

The Nigerian constitution supports the right to self-determination of one's faith. Igbo Muslims trying to establish their right to be Muslims and to refute assumptions by other Igbo that Islam is incompatible with Igbo identity severally reiterated this. The process of conversion to Islam in Igboland is no different from the mechanics of conversion to Islam generally: an intending male convert informs a Muslim, generally an imam (a Muslim religious leader or the head of a specific Muslim community that worship in a particular mosque), if personally acquainted with one, of his decision to become Muslim. Some first try to obtain basic knowledge about Islam or discuss their intentions with people around them, friends as well as family members who appear predisposed to support their move. Once the decision to convert is taken, the intending convert contacts an imam directly or through an acquaintance. In response, the imam invites the individual to the next Friday worship at the mosque. Dauda Ojobe's conversion in 1971 followed this pattern. When Ojobe (b. 1929) informed the imam in his community that he wished to become Muslim, he was asked to return the following Friday to communicate his intentions to the community of Muslim believers in his village, the majority of whom were non-Igbo. In 1990, at Kaduna, Nathan Okeke (b. 1969) passed through a similar process to become a Muslim, even though he had been a regular visitor for some time at the mosque, taking part in prayer and other acts of worship.Footnote 15 At the end of the Friday congregational prayer, and in conjunction with the counseling of the imam, the potential convert informs the congregation of his intention to be Muslim. He is told of the basic observances of Muslims, namely avoidance of alcohol, cultivation of perpetual love for all, and observance of the five daily prayers. If the newcomer pledges commitment to these acts of worship, he is led through the ritual bath of purification (Tahāra), a symbolic bath performed without cosmetic soap. The ritual is interspersed with recitations and the confession of the Shahāda, by which the convert affirms ‘There is no God but Allah and Mohammed is his prophet.’ Igbo Muslim leaders and converts commonly refer to this event as the ‘Muslim baptism’.Footnote 16 Fitted into the induction are lessons on pre-prayer ritual washing or ablutions. It appears that there has been no significant change in this ritual from that described by Abdurrahman Doi based on his observations in Ibagwa in 1965:

The intending convert is given a bath, and is dressed in a white robe especially prepared for him for this occasion; then he is brought to the mosque where fellow Muslims of different ethnic origin assemble to witness the conversion. The Shahāda is pronounced and repeated by the convert and the Imam gives him guidance on Islamic matters. Then the Jama'ah, i.e., the gathering, cheer the new convert, saying Alhamdu Lillad and Allahu Akbar, after which the congregation donate whatever they can to help their new Muslim brother, from one kobo to one naira.Footnote 17

In nearly all African Muslim communities, the mere profession of faith has been sufficient for admission into the community.Footnote 18 The conversion ceremony is a public proclamation (witnessed only by Muslims), symbolizing the rejection of any previous religious tradition for Islam. Candidates for conversion who fail to submit to the ceremony do not regard themselves as Muslims and are also not regarded as such by other Muslims, although some may retain strong interests in Islam, even practicing it somewhat in daily life.Footnote 19

As part of the conversion process, the convert is guided to choose a new name. At the naming ceremony, a ram may be slaughtered. With or without a special naming ceremony, new names of Arabic origin, either with Islamic connotation or not, are adopted to replace the convert's first name or last name. The name change reflects the convert's new faith. Name change after conversion was common with early converts from Nsukka, Abakailiki, and Owerri Divisions of south-east Nigeria before 1967. Hausa and Nupe mallams (scholars) who came to Igboland as traders and as companions of Muslim traders officiated in those naming ceremonies. Adult naming ceremonies were not as elaborate as the naming of children born to Muslim converts, as described by the imam Ibrahim Eze:

When Hausa Muslims from Kano came to Ibagwa, they gave names to children born to the Igbo who joined them in Islam. They took a barber to the naming ceremony and he barbed the hair of the new baby and gave it facial marks. They gave us facial marks. They taught us that since we have joined Islam, we should observe their custom …Footnote 20

The imam's story was corroborated by a former female Muslim of Igala origin from north-central Nigeria, married to an Igbo. She noted: ‘The Muslim naming ceremony was full of celebration. Once a child was a week old, the hair was barbed and marks were made on the face.’Footnote 21

Conversion to Islam brought changes in the lifestyle of Igbo converts. Taking on new names to reflect a new religious identity also occurred during the early decades of Christian missionary activities in the south-east and elsewhere in Nigeria. As Christian converts had their local names changed in mission schools to Christian or European names, in like manner Muslim mallams supervised the adoption of Islamic or Arabic names for Igbo converts to Islam. The Muslim name change does not derive from any borrowing from Christian missionaries but has an independent origin that dates to the foundation of Islam, during which time the adoption of new names signified personal worship or confession of one's faith. Name change, Frank Salamone points out, made further identification with one's religious community easier.Footnote 22 Igbo Muslims interpreted it as an indication of the authenticity of their conversion claims.Footnote 23

Until the end of the 1980s, widely differing opinions were held concerning the emphasis on Arabic or Islamic names for Igbo converts. The 1990s, however, saw a change in Igbo Muslims' disposition to this identification policy and its relevance. Since then, imams of Igbo origin have advocated that new converts to Islam should retain their vernacular or Christian names while also adopting an Arabic name as the first or middle name. Imam Ibrahim Eze, one of the oldest Igbo imams, explained the discourse underpinning this change in practice, which results from their understanding that Islam does not call for a loss of ethnic identity:

In the early days of Islam some of the Arab Muslims retained their pre-conversion names. God ruled that they should retain their names … There were actually many early Arab Muslims who retained the original names their parents gave them. Here in Igboland, a long time ago, we debated this issue and agreed that converts should retain their original names provided they are practicing Muslims. However, there is an Islamic injunction that revertees should choose one of the old prophetic names.Footnote 24

Apart from taking on a new name, Igbo converts were given facial markings by Muslim mentors from Nupe and Kano to align them with their new ethno-religious customs. Facial marks were indeed part of the cultural marker of some riverine Igbo groups but had no religious basis. These Igbo communities gave marks to their members during the long centuries of the slave trade, using the marks as a safeguard for clan members and also for facilitating quick identification of slave victims. By the time colonial rule was established and pax Britannica enforced, the need for marks dwindled and the practice lost its prominence for those communities that relied on it as they would on their modern international passports. It continued, however, in Alor-agu in Nsukka Division, where it assumed a new significance, being associated with conversion to Islam. C. K. Meek records that facial marks were used by Hausa ethnic communities in northern Nigeria and Islamized communities in north-central Nigeria for a variety of reasons: to distinguish their members from other ethnic groups; to prevent loss of identity during the slave period; and, afterwards, as adornment or as an indication of membership in Islam. He writes:

Religious ideas also exert a modifying influence on the system of scarification. Thus the alternated triple lines at the corner of the mouth, such as used by the Nupe of Bida, by the younger generation of Kakanda, and by many other Islamized [groups] of Ilorin, Nupe, Nassarawa, and Munshi provinces, are said to be an indication that the parents of children so marked were Muhammadan.Footnote 25

Encouraged by Muslim mallams of Nupe, Hausa, and Yoruba origin, Igbo converts to Islam learned the rudiments of their new faith, giving emphasis to prayers and their set times, and to identification with Islamic practices such as the wearing of Muslim clothing; in reality, this required converts to be dressed in gowns according to the fashion of Muslim Hausa, and many years later in their Yoruba variants by those who did not wish to align themselves so closely with Hausa Muslim identity.Footnote 26 Nupe and Hausa Muslim settlers in Igboland had begun by the 1950s to integrate their converts within existing Hausa and Nupe settlements. Thus, Igbo Muslims, with their Hausa and Nupe mentors, created distinct Muslim communities within existing Igbo communities. These communities have survived today and are found at Alor-agu, Ogrute, and Ibagwa, all in the Nsukka area of Enugu State as well as in Owerri and Orlu in Imo State. In Enohia, Ebonyi State, where group conversion of a quarter of the village occurred in 1958, the reverse was the case, as the Igbo Muslim community took the initiative of incorporating Muslim migrants from northern and north-central Nigeria within its territory to help train them in the way of Islam. The relevance of these religious communities lay in the fact that basic Islamic precepts with the necessary base culture were thus more easily transferred to new converts. The realistic conclusion would be that the practice of Islam by the Igbo in its early stages followed the Hausa prototype, with many Hausa cultural details. Converts lived in a kind of apprenticeship arrangement, attached to Hausa or Nupe traders, some of whom doubled as itinerant mallams, for purposes of learning Islamic worship and the daily routine of believers from the original custodians, as these groups were considered to be. Converts imitated their spiritual mentors in nearly everything, and their wives – most of whom converted along with them – also conformed to the pattern of the daily routine of Hausa Muslim women. My oldest female interviewee, who was born when ‘there was no school’ remarked:

I was young when I entered Islam. If at that age you were married, you were required to be obedient to your husband. Whatever he told you not to do, you did not do it. If he said do not go out, you did not go. When he decides to let you go, you go.Footnote 27

Nevertheless, learning the rudiments of the faith at a time and in an environment where the facilities for it were lacking or inadequate was challenging, judging from the experience of Igbo converts to Islam in the 1950s to 1970s. Referring to the life of his father, who became Muslim in Enugu Ezike in the 1950s, Sheikh Idoko observed: ‘Actually my father was not so learned in the Qur'an. He learned just the basics, like the prayer.’Footnote 28 Alhaji Musa Ani recalled his experience after his conversion to Islam in Enugu in 1975:

It was not easy knowing what was going on. I joined them in prayer without knowing what they were saying. I just marked my head on the ground as I saw them mark their heads on the ground. And the Hausa man was not literate to educate you …Footnote 29

From the inception of the Igbo Muslim community at the turn of the 1950s, adult converts to Islam arranged for Qur'anic education for their male children. Some sent their children to itinerant mallams who served the Hausa Muslim migrant community to train them in the recitation of the Qur'an. Others sent their sons to northern and north-central Nigeria for their Qur'anic education. Learning centers patronized included Akpanya, Nassarawa, Keffi, Kano, and Sokoto. The first crop of Igbo Muslim children who learned to recite the Qur'an outside Igboland did so in the 1950s, before the establishment in 1958 of the first Qur'anic school in Igboland at Ibagwa-aka in Nsukka Division. Two foreign teachers, one of whom was a Sudanese, served the school. A second school was established in 1963 in Enohia in the old Abakaliki Division. The Ibagwa and Enohia Qur'anic schools were destroyed during the civil war; only the Enohia school has since been rehabilitated. For the years when the Ibagwa school functioned, it suffered from lack of funds and unavailability of teachers.Footnote 30 From 1970, after the civil war, other Qur'anic schools were opened at Owerri (Imo State) and in the army barracks of Enugu (Enugu State) and Onitsha (Anambra State) for families of non-indigene soldiers of the Nigerian army stationed in those places. The Qur'anic schools offered basic knowledge of the Arabic language to help Muslim children say their prayers in their original language. Proper knowledge of the Arabic language and Islamic studies was acquired outside Igboland. In 1973, the proposal to establish an Islamic primary school that would combine formal school curriculum with Islamic subjects was first publicly disclosed. A newspaper report stated:

The first Islamic school in the East Central State is to be sited at Enugu. The school will admit pupils from all parts of the state … The Igbo Muslim leader in Enugu, Malam Sulaiman Onyeama, said it was decided at a recent representative meeting of Muslim leaders in the state.Footnote 31

Post-1980 converts appear to have had better opportunities than the older generation, although still not comparable with what could be obtained in the Muslim states of northern Nigeria or in western Nigeria, which also boasts a large Muslim population that dates back to about the late sixteenth century.Footnote 32 In 1988, a second Qur'anic school in the Nsukka area was opened at Obukpa, and another in 2002 at the Nsukka town market for children of traders of northern Nigeria origin. The market school is supervised by the Sarkin Doya, the Hausa chief of the market responsible for coordinating the business of traders of northern and north-central Nigeria origin. It is supported from donations from northern Nigeria and the contributions of the local Muslim community. In much of Igboland, Qur'anic schools operate in the evenings and at weekends to avoid interfering with the schedule of government schools. More recent Qur'anic schools are found at the cattle markets of Enugu, Umuahia, and Lokponta in Abia State, serving families of traders from northern Nigeria. On the whole, the Qur'anic schools in Igboland report poor attendance of children of Igbo Muslims, most of whom engage with their education at government schools.

Far better access to Islamic religious education was obtained in northern and western Nigeria. In addition to these provisions, Igbo converts living in those parts of the country were also integrated with indigenous Muslims soon after conversion, for the purposes of transferring religious precepts and basic Islamic culture to new converts, just as occurred in Igboland from the 1950s onwards. Speaking of Kaduna State in the 1990s, one interviewee observed:

The Igbo who converted to Islam stayed with a mallam for a period of time to learn about Islam … Previously they were not doing that until the Hausa discovered that the Igbo were more interested in their money than in their religion … Now, when they get an Igbo convert, they keep him with a mallam in a place like Tudunwada.Footnote 33

Besides the direct contact with mallams who were on hand to guide the young convert through his religious obligations, Islamic schools were readily available and offered basic Qur'anic education and advanced Islamic studies, all in a far more ideal setting than could be offered in the south-east.

Conversion seems to have elicited its own excitement. Male converts reported feelings of intoxication with their new faith after conversion. Their enthusiasm was variously displayed, but one obvious outcome was the quick adoption of flowing gowns. Alhaji Musa Ani, who converted to Islam in 1975, asserted:

I started wearing babariga [Hausa style flowing gowns] without wasting time and one long cap longer than [President] Shagari's. People called me Aboki and ‘Alhaji ba Mecca’ [a Muslim pilgrim who has not performed the hajj]. I did not hide what I was doing. I was proud …Footnote 34

Such enthusiastic converts took on with equal speed the task of convincing family members – wives, children, siblings – and, where possible, friends and associates to become Muslims.Footnote 35

Unmarried Igbo male converts accelerated their process of adaptation to their new religious family by taking Muslim wives. Suitable wives were found without much difficulty in the Nsukka area of northern Igboland and in Kogi State, in north-central Nigeria. It appears to have been considerably easier, however, to marry a woman from Hausaland. It spared most grooms the problem of convincing non-Muslims to marry them. Moreover, whereas a non-Muslim woman may readily agree to marry a Muslim male, the same ease of acceptance of the marriage cannot be guaranteed from her relatives. A few converts also mentioned the simplified marriage rites of Muslims as another appealing reason for marrying women from Muslim-dominated communities. For many interviewees, it is easier practicing Islam in areas with predominant Muslim populations than in the Igbo homeland. Perhaps because of this, a good many Igbo converts to Islam residing outside their villages are not known in their home communities as Muslims because they have never disclosed that identity there.

Clearly visible outward markers were associated with Igbo converts to Islam, as already noted. Indeed, there is no doubt that conversion to Islam went hand in hand with the reception of various manifestations of Hausa culture. Abdurrahman Doi, the Pakistani Muslim scholar who labored in the 1960s with a few Muslim expatriates and non-Igbo academics affiliated with the University of Nigeria to fan the fire of Islam into flame in Ibagwa and Obukpa communities of Nsukka Division, confirms this connection:

Those Ibos who have accepted Islam have automatically accepted the material manifestation of Islamic culture. With the acceptance of Islam, they have accepted the ideal of the universal brotherhood in Islam and look upon other Muslims as their Ikhwan fid Deen i.e. ‘brethren in Islam’.Footnote 36

What Doi calls ‘Islamic culture’ in reality became hausanization.Footnote 37 This process, which was a more-or-less direct result of conversion, according to non-Muslim Igbo assumptions, differed in its degree for individual converts and their locations. For most Igbo Muslims in south-east Nigeria, hausanization manifested in the dress pattern, the style of the child-naming ceremony, Islamic dietary prescriptions, and the interjection of a few Hausa words into common parlance. The use of these words had so far been restricted to Muslims and is not very common among the Igbo generally. The popular ones were Kulleh (‘seclusion’), karatu (‘Qur'an’), kafirci (‘unbeliever’), makaranta (‘Qur'anic school’), and musulachi (‘mosque’).Footnote 38 Most Igbo Muslims, including clerics, retained the use of Chukwu (the Igbo term for God) in place of Allah in their references to the Exalted One.

Post-conversion transformation was observed more with men than with women, for whom many of the Muslim markers were blurred by customary Igbo demeanor. The grooming and comportment of Igbo Muslim women closely resembled those of non-Muslims, so that only very rarely were their religious affiliations discerned, even from their attire. The wife of a chief imam, who was ‘born into Islam’, disclosed her avoidance of headscarves and other Muslim markers in public out of consideration for her business, which she did not want to harm by revealing her religious identity. However, she never failed to have a scarf handy so that she was not hindered from saying her prayers at the appropriate times.Footnote 39 While emphasis was not laid on female public participation in general prayers, the situation was different for men, whose conversion become known when regularly seen walking to the mosque with Hausa and other known Muslims.

Among Igbo Muslims living in the major cities of northern Nigeria, the degree of hausanization varied: one group appeared completely assimilated into Hausa culture, while the attitudes of another resembled those of their brethren in the homeland. For those fully assimilated, their spouses were Hausa and their children were raised as Hausa. Douglas Anthony's study of Igbo Muslims in Kano city shows that, in many cases, the fully hausanized had severed all links with their non-Muslim families in the south-east and also with the south-east itself. For the category with a lesser degree of hausanization, spouses were largely Igbo, Igala, or even Hausa, but their children were raised as Igbo. One reason for the thorough hausanization by Igbo Muslims in northern Nigeria, as found in this study, was the need to adapt completely to the religious requirements; in the minds of many Igbo Muslims, Hausa culture best typifies Islam.Footnote 40 Another reason, disclosed by Anthony, was the need to avoid being tainted by the hypocrisy of less ingenuous Igbo converts, who nominally join Islam for economic reasons but recant later.Footnote 41 Just as converts living in northern Nigeria showed tendencies indicative of some degree of hausanization, so also did converts residing in western Nigeria, although, for this group, the degree of cultural influence appeared minimal.

THE BENEFITS OF CONVERSION

In addition to the spiritual wellbeing anticipated from conversion, there were fringe benefits that Igbo converts associated with being Muslim. Muslims in Nigeria have long gained a reputation for helping each other, and this, for the most part, was the motivation for several pragmatic conversions. An early documentation of such conversions in Nigeria was Murray Last's account of the Maguzawa of northern Nigeria in the 1960s and 1970s, who though practically richer than their Muslim neighbors converted to Islam for purposes of expanding economic interests.Footnote 42 Conversions to Islam in Igboland have similarly been associated with economic and political benefits.Footnote 43 Muslim benevolence was helpful when converts were made: assistance rendered by older Muslims cushioned the harsh reactions of relatives, friends, and colleagues opposed to a new convert's resolution; help from other believers was reportedly relied upon during stressful moments. The first generation of Igbo converts to Islam, during the 1930s to 1950s, spoke effusively about the benevolence of Nupe and Hausa Muslims to them. It was widely reported at Enugu Ezike that persons who showed interest in Islam in the 1920s found a mentor in Ibrahim Aduku, a Muslim horse trader of Nupe origin, who took local citizenship in the town in the 1920s. Aduku facilitated local interest in Islam through generous provisions of credit to both traders and non-traders. The fruits of his labor in terms of outright conversion of the local people to Islam were not very significant, being limited to his wives and children and perhaps a few indigenes who became converts many years after his death in 1931.Footnote 44

Through similar acts of patronage, Sheikh Ibrahim Nwagui of Enofia, in the Afikpo village group of Abakaliki Division, now in Ebonyi State, drew indigenes of Enofia into Islam from 1958 until his death in 1975,Footnote 45 just as Hausa and foreign Muslim missionaries of Saudi origin did in Mbaise, Imo State, between 1970 and 1974.Footnote 46 This latter group of Igbo Muslims, the post-civil-war converts, enjoyed educational sponsorships that took them to foreign Muslim countries for study. Among the earliest beneficiaries of such scholarships was Mallam Isa Ekeji, one of the first converts to Islam in Mbaise: he was trained at the University of Damascus in Syria. Between 1970 and 1990, converts of varying ages received scholarships to study in Saudi Arabia in particular, but also in Egypt, Libya, and Pakistan. Such opportunities became incentives for encouraging Igbo male youths into Islam. Comparatively, far fewer female Muslims enjoyed similar benefaction – doing so as rewards for their fathers' conversions – and their sponsorship was by and large for secondary education within Nigeria.Footnote 47

Until the 1980s, study scholarships to Saudi Arabia were for both secondary and tertiary education. This changed in the 1990s, according to Sheikhs Idoko and Abugu, when scholarships were given essentially for university programs only, with candidates for secondary education partly or fully sponsored to study within Nigeria, preferably in northern Nigeria. The main subjects of study at Islamic universities were Islamic sciences and Islamic jurisprudence. Comparatively few scholarship-holders gained their degrees in the pure and applied sciences; there is no record so far of any graduate from the arts and humanities.Footnote 48

The Muslim World League (MWL), popularly known among Igbo Muslims as Rabita (from Rabita al-Alam al-Islami), was cited by several interviewees as the major sponsor of study scholarships for Igbo Muslims. It is also the organization that trained nearly all the sheikhs in Igboland in Saudi Arabia. These, on completion of their training, were posted back as missionaries to Igboland. The MWL was founded by, and in, Saudi Arabia in 1962 as an agency for the spread of Islam and the promotion of Islamic unity.Footnote 49 It is financed by various Muslim countries, whose membership in the organization is voluntary, but Saudi Arabia is its acknowledged major donor. Of its eight bodies and their functions, the two whose presence have been felt in Igboland in the past two decades are the International Islamic Organization for Education and the International Islamic Relief Organization.

It can be said that Rabita, through its educational and other opportunities for Igbo converts to Islam, has effectively promoted Islam in Igboland over the past three decades. Igbo Muslim missionaries, trained in Saudi Arabia in particular but also in other Islamic countries, have gradually taken over religious responsibility for the Igbo Muslim community from imams of Egyptian and Pakistani nationality and their counterparts from northern Nigeria, who together constituted the foundational Islamic clerical community in Igboland before 1990. Although many imams in Igboland are still non-Igbo, an appreciable number of indigenous imams have emerged since the mid-1980s.

The association of Igbo Muslims, and indeed Nigerian Muslims, with Rabita presupposes their exposure through Rabita influence to Wahhabiyya views, which has been regarded internationally as a radical form of Islam.Footnote 50Wahhabiyya was variously accused of terrorist activities in different parts of the world. The MWL and the International Islamic Relief Organization in particular were both mentioned in connection with financing terrorism, and this, perhaps, might have fuelled concerns on the likely outcomes of Igbo conversions to Islam, such as the possibility of the development of Islamic fundamentalism in Igboland in such forms as the emergence of internal strictures such as sharia law in Igbo states. These concerns are quite beyond the scope of this study, given the recent emergence of Islamic worship in Igboland and the preoccupation of Igbo Muslims, in the last three decades, with constructing an identity for themselves. However, what clearly emerged during this investigation was the unpopularity of sharia law with a great number of Igbo Muslims.Footnote 51 The non-Muslim majority in Igboland have been against any form of religious assertiveness in the Igbo homeland by Muslims, Igbo or non-Igbo, as one way of forestalling the imposition of any strong Islamic influence on the homeland. Muslim converts, therefore, are in many communities excluded from local politics and disqualified from holding chieftaincy titles. Awudu Munagoro says:

It is assumed that I am a member of the Nnewi Community Union because every adult male indigene must belong to it. In the real sense I am not a member because they will never allow me to speak during meetings and if they give me a chance to speak, my words will not be accepted. They regard me as an Hausa man because of my religion yet I know that in the Nnewi Community Union, everybody is not Christian. Some belong to the Igbo religion. They will allow them to speak and their words will be accepted.Footnote 52

Jamir Abdukareem, who became a Muslim in western Nigeria before the age of 16 and who displays Yoruba Muslim cultural influence, stated: ‘We do not keep our heads high like those in western Nigeria. We try to keep our heads low and avoid whatever might generate conflict.’Footnote 53 Indeed, Igbo and foreign Muslim missionaries in Igboland regard the Igbo environment as hostile to Islam and the people themselves as resistant to its ideology. This unresponsiveness appears to affect Igbo Muslims, if we accept the view expressed here:

One notices a loss of courage in this society, manifested most strongly in the failure of Igbo Muslims to individually and collectively face up to the challenge of being Muslim which otherwise consists in absolute and unconditional loyalty and submission to Allah, obedience to and execution of his law, the recognition of the supremacy of the Qur'an and Sunnah, the propagation of his message and opposition to any doctrine, philosophy, or system that contradicts it, and being ready for the defense of Islam. Today, Muslims no longer talk of themselves as Muslims for fear that unbelievers might be angry with them. They prefer to be identified with the democrats, mixed economists, socialists, Marxists, humanists, and so on, all in the attempt to obscure their Muslim identity. This is the limit of cowardice: when one can no longer say ‘I am’!Footnote 54

Sheikh Idris Al Hassan, the Ghanaian Muslim missionary in Igboland, expressed optimism for future success in Muslim missionary endeavors in Igboland. He was one of those who identified financial constraints as an important deterrent to launching a strategic and successful missionary campaign in Igboland. In the meantime, he gave the following assessment of the Igbo after 23 years (1979–2003) of missionary work among them:

I have not seen the Igbo hostile, but to the religion. What I can tell you is that they are ignorant of Islam and, naturally, whatever one is ignorant of he fears it or hates it … If you think that the Igbo would want to come to Islam en masse, it is not going to be by mere preaching and preaching alone. Not preaching in this limited form we are doing … You know your people … If a man does not believe, no matter what you do, he sticks to what he does …Footnote 55

Another factor affecting Igbo responsiveness to Islam is the confusion from recent incidents of religious conflicts in the country. With the introduction of sharia law in northern Nigeria from 2000 and efforts to implement the same, attacks were launched on non-Muslims residing in the sharia states. The outcome in Igboland was the intensification of the connection drawn between Islam and violence. The Enugu State Muslim public relations officer articulated the Igbo stand on these incidents as follows:

The Igbo believe that if one joins Islam, he will be killed. If he is not killed, he will be made a killer. The Igbo man does not want to be a killer and he does not want to be killed.Footnote 56

RESPONSES TO CONVERSIONS TO ISLAM

Humphrey Fisher wrote that conversion ‘was sometimes, perhaps often, a difficult step, likely to arouse scorn in traditional society’.Footnote 57 He offered the example of the Galla, who ridiculed Muslims as ‘women water-carriers, back-rinsers, crying to prayer like monkeys’, and the Bambara, who likened ‘the Muslim at prayer to a donkey grazing’. Igbo Muslims have found themselves in a similar situation. Reactions to conversions to Islam in Igboland have, in general, rarely been pleasant, attracting much ridicule. The common tendency leans towards disappointment with, and denunciation of, the convert. If Igbo society were divided roughly into two, at one end (and in the majority), would be found those who are negative about Islam, while, at the other end, would stand those who appear not too upset by Islam and who rather admire the religion and the commitment of its members.Footnote 58 This second category includes within its ranks individuals who have had relatively close interaction with Muslims, either in northern or western Nigeria or elsewhere.Footnote 59 They are rarely incensed over Igbo conversions to Islam.

For that majority that treats conversion to Islam with displeasure, their concerns broadly rest on five points. The first is the fear, which is still current, that conversion would mark the gradual fulfillment of the nineteenth-century Fulani jihad strategy of thrusting south until non-Islamic communities located well beyond the southern limits of the Sokoto Caliphate were brought within the sphere of Islam. Johnson described this strategy as an attempt ‘to dip the Qur'an into the sea’,Footnote 60 a phrase that has stuck since colonial times. A second reason derives from the lingering bitterness over the atrocities meted out to the Igbo during the Nigeria–Biafra War by Hausa soldiers of the Nigerian army.Footnote 61 The third is the resentment arising from the possibility of Igboland losing its long-held stand as a non-Muslim territoryFootnote 62 and its image as a land of ‘almost total Christianity’, as Ottenberg describes it.Footnote 63 The fourth point is the perceived marriage of convenience between Islam and violence. This association was worsened by the upsurge of militant Islam both globally and in Nigeria since the 1970s.Footnote 64 The recent resurgence of Muslim militancy in Nigeria from 2000 manifested in the accelerated incidence of Muslim attacks on Christians, which eventually provoked counter-attacks from Christians. This supposed Muslim flair for violence was contrasted with Igbo aversion to the shedding of blood. Many Igbo are alarmed that conversion would predispose their Muslim members to violence, thereby ending the Igbo historical aversion to bloodshed.Footnote 65 Lastly, there is a worry that religious balkanization, a possible consequence of conversions to Islam, endangers Igbo interests and survival and might bring about the eclipse of Igbo culture by the imposition of Hausa norms. Added to this are the hard feelings for certain Hausa Muslim values, such as a traditional system perceived by many Igbo as unsupportive of economic and social innovation encouraging self-affirmation, individualization, and democratic decision-making, all of which are regarded as key features of Igbo ethnic identity.

An Igbo position on the first three points was articulated in 1969, during the Nigeria–Biafra War, by Lieutenant Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu, Biafra's military leader, who described the conflict between Nigeria and Biafra as a war against Muslim expansionism in Nigeria. Much of the religious aggression and official proselytization of the late Sir Ahmadu Bello, the Sardauna of Sokoto, a descendant of Uthman dan Fodio, and the first Nigerian political head of the Northern Region until January 1966, was construed by the Igbo to be geared towards accomplishing the nineteenth-century jihad strategy of conquering non-Muslim lands south of the Sokoto Caliphate. The Igbo in particular, but also other non-Muslim groups of north-central Nigeria, commonly held that the Sardauna was determined to ensure the conquest of Nigeria under Islam. The result was Colonel Ojukwu's accusation that the Sardauna tried ‘by political and economic blackmail and terrorism, to convert Biafrans settled in northern Nigeria to Islam’, in the hope ‘that these Biafrans of dispersion would then carry Islam to Biafra, and by so doing give the religion political control in the area’.Footnote 66 To forestall the accomplishment of this plan in Igboland, state-sponsored persecutions were unleashed against Igbo Muslims during the war. The traumatized group, found mostly in Nsukka and Abakaliki Divisions, were forced to flee Igboland until these areas were brought under the control of the Nigerian army and the safety of Igbo Muslims was guaranteed.Footnote 67 Thirty-nine years after the war, Alhaji Omar Farouk considers it a success for Islam that there are now indigenous Muslims in south-east Nigeria, including Rivers State, the southernmost part of Nigeria. He regards this development as the fulfillment of the jihad prophecy that the Qur'an would be dipped into the sea and, for him, the sea referred to is the Atlantic Ocean.Footnote 68

In addition, there is a widespread sense that Igbo culture is not aggressive. There are many popular remarks that the Igbo tradition and worldview abhor the shedding of blood with which Hausa Muslims have been associated. Persons who object to Igbo conversions to Islam on the grounds of assimilation of Hausa Islamic culture are concerned that the sacredness of blood would be compromised by Igbo converts. They enjoy the support of those who do not wish to relinquish their members to another ethnic group. Adamu and Anthony both outline the high assimilation tendencies of the Hausa ethnic group.Footnote 69 Anthony, in particular, reports on three Igbo men who, after conversion to Islam, acquired Hausa ethnic identities, relinquishing their Igbo identities.Footnote 70 The fear of such loss for Igbo communities is a major factor in their resistance to Igbo conversions to Islam. Remarks suggestive of this loss are commonly heard and are responsible for converts being addressed as onye Hausa (‘Hausa man’) or nwanyi Hausa (‘Hausa woman’), implying that the convert is no longer an Igbo but a Hausa. It was in an attempt to forestall these losses (as some construed them) that a community in Igboeze excommunicated a convert in the anticipation that he would repudiate his faith. The importance of such measures lies in the social and economic benefits of belonging to a specific ethnic group. In mounting such pressure, community leaders understood the unlikelihood that all converts would easily and simultaneously accept rejection from their families and from the entire community. One excommunicated convert worked through his extended family to win his acceptance back into his community but only succeeded after he agreed to the conditions set by the community leaders, which were communicated by their chief: that he would retain his Igbo names and every marker of his Igbo identity and ensure that his children did same; that he would take part in shared communal activities as an indication of his involvement in the community; and, lastly, that he would make certain that his children mixed freely with other children of their age in the community.Footnote 71

The Igbo Muslim community is aware of the backlash caused by the series of riots against non-Muslims in northern Nigeria between 2000 and 2006, which in turn provoked retaliatory killings of Hausa settlers in Igboland by the Igbo. Mallam Ibrahim Eze, a chief imam, lamented the disrepute into which Islam and Muslims were brought by the riots and the hostility from Igbo non-Muslims, and remarked, ‘Now Igbo parents regard their sons who want to join Islam as going to participate in the many crises for which Hausa Muslims were famous and so they try to prevent them from shedding blood.’Footnote 72 A strongly worded denunciation of Islam by a young Igbo man, which touched on some of the factors causing resentment at conversions to Islam in Igboland, demonstrates the outlook of this class towards Islam and its progress in Igboland:

It was for the lust of knowing what should not be known that man made this mucky journey into religion … Taking into consideration the recent events in Nigeria … one could see the irony of Islam. Muslims preach peace and propagate war, terrorism, destruction, confusion, and riot. They preach unity and love but regard non-Muslims as infidels whose necks should be broken. They preach intolerance where they are in the majority but tolerance where they are in the minority … About 75 per cent of riots in Nigeria are caused by Muslims. Islamic religion promotes anarchy.Footnote 73

It is not unusual to find a good number of Igbo for whom conversion to Islam is tantamount to betrayal of, and disloyalty to, their ethnic group. Family members, colleagues, acquaintances, and friends reportedly use subtle and not-so-subtle means to express displeasure at conversions to Islam. Deriving from the basic premises outlined, Igbo aversion to Islam that became public during the Nigeria–Biafra War continued afterwards, frequently coming to the fore each time a member of the group became Muslim. Children of Muslim converts were not spared public antagonism for the conversion of their parents and, of course, their own. The principal of the Islamic primary school at Enugu concluded that children suffered more public antagonism than their parents, supporting this by saying: ‘When they appear at bus stops other commuters address them rudely, saying “Hausa children, go away!”Footnote 74 In 2003, the city of Enugu had a projected Igbo Muslim population of less than a thousand, scattered amid a population of about a million inhabitants. There, as in other parts of Igboland, Muslim converts, who are in the minority, were easily identified, making them easy targets of public disapproval.

Public antagonism may heighten with each convert gained by Islam, even when the immediate family of the convert is not bothered by the conversion. Ironically, in one interesting case of the conversion of a lawyer about a decade ago, his Muslim relatives were displeased with the conversion on the grounds that it was a career-motivated act, not borne out of sincere religious quest. In this instance, the bone of contention among his Muslim relatives centered on the genuineness of the conversion.Footnote 75 Thus, the convert found himself in a strait betwixt his Muslim relations, mostly members of his extended family, and his non-Muslim family members. Both sides had issues with his conversion.

Igbo converts to Islam tell of unpleasant episodes that attended their conversion experience. Below is Alhaji Mutui's story of his conversion experience in 1982:

When one embraces Islam he faces persecution from relatives. In my own case my wife was against my conversion because we were very good Christians. She did not see why we should abandon Christianity. Later she converted but after a while she saw that she could not do those things she did as a Christian … The worst were the daily prayers and all the hard dos and don'ts. Living a Muslim life is full of dos and don'ts and commitment to the practice of Islam. She couldn't cope. She left the family in 1986 and went back to Christianity …

My other relations also kicked against my conversion. Up till now they are not comfortable with my being a Muslim. But, it is my faith; it belongs to me, I cannot compromise it for anything! When in the course of prayer we say “Allahu Akbar,” meaning “God is great,” people make mockery of us. They call us ndi alakuba. Footnote 76

Two more uncorroborated stories were given as indications of public opposition to conversions. In the first, the issue at stake was the broadcasting in the 1980s of a Muslim religious program by the National Television Authority in Enugu, the major Igbo city:

Christians had Christian half-hour so I thought of hosting a similar program for Islam. My application to the Nigerian Television Authority for permission was denied. I went to the head office in Lagos and applied. After a series of petitions, I was directed to the person in charge of the religious unit. He was a Reverend Father who knew me as a Christian … He was annoyed with me … He felt I was going to preach against Christianity and refused my request to host the program. I continued mounting pressure until he asked me to put in an application and I did … They prepared a set of guidelines that I should not mention Jesus Christ and that I should not abuse other religions. I went by that agreement and they aired the program … The program ran from 1983 until 2000. Sometimes, mid-way though the recording, it would be stopped in anger to a comment made about Jesus Christ and I would be told to present my religion and not compare Christianity with Islam … Educated Muslims were shy to appear on the screen in that program. Those who did and went back to their offices were ridiculed by their colleagues …Footnote 77

Meanwhile, Harun Eze, a 27-year-old undergraduate from Enugu Ezike, narrated this story:

Contrary to what people say, Islam is a religion of peace … But with respect to my community, I would say that Islam has had a divisive impact … The constitution of the country accords the right of freedom of religion to you and me but in my community Muslims are marginalized. People treat us like outcasts. They despise us and deprive us of what is rightfully ours. For instance, the University of Nigeria is one of the best universities … but I was denied admission there even when the university is located at my backyard and this was because I am a Muslim. Islam also created a huge barrier in my relationship with people.Footnote 78

The extent to which Harun's claim was true is unknown. There have been a growing number of Muslim students in the University of Nigeria since its inception in 1960. In recognition of its Muslim population, the university has a mosque within its premises, which serves its Muslim members as well as other Muslims from the surrounding villages, and also a resident chief imam. An Igbo Muslim student, Okpani Oko from Enohia, participated actively in this study as a research assistant. It is questionable that admission into the university was denied to a qualified candidate on the grounds of religious affiliation, since the same university admits Muslim students of all ethnic backgrounds.

One quality of conversion is that it brings about realignment in religious belief and daily customs, and produces other changes. It necessitates a convert leaving one religious camp for another and giving up one set of values for another. The group losing naturally fights to win back what they are about to lose as, simultaneously, the group gaining does all it can to consolidate its gain. The resulting scenario presents little opportunity for a win–win situation since one party wins and another loses; the reactions of the losing party can be imagined. Igbo converts to Islam find themselves in the centre of the pull between their new religious family and their discarded religious family. There is no end, except the threat of death, to the efforts of friends and relatives eager to dissuade the convert from his chosen course. Where parents seem deeply antagonized by a child's conversion, the often-reported action is to disown – albeit temporarily – the convert. In Anambra State in 2006, a 43-year-old woman reported this treatment from her father following her marriage to a Muslim, which her family understood as a prelude to her conversion to Islam.Footnote 79 These attempts are not always indications of hatred for the convert but the consequence of personal and group prejudice against Islam and sometimes against the Hausa, who typify Islam and its worldview to the Igbo. Friends and relations engaged in the war of reclamation of Igbo converts more often than not act on the assumption that their actions are necessary to save a precious one from potential error and deviation from the truth. Few consider the convert's interests and choices, thus negating their right to self-determination in the all-important matter of faith.

Among Igbo converts to Islam are persons who clearly comprehend the basis for local resentment towards Islam and who acknowledge how difficult it is for most Igbo to accommodate the regulations of the religion to the point of converting. Dauda Ojobe, whose conversion occurred in 1971 observed:

Muslim ritual washing that required converts to carry kettles all the time hindered people from becoming Muslim. Hardly would you meet a farmer, on his return from the farm, who would agree to do ablution – wash here and there – before eating; or who would move about with kettle … even after urination when he was mandated to wash.Footnote 80

When matters of religious regulations are combined with memories of the Nigeria–Biafra War, and the consequent hausanization of Igbo converts to Islam, reactions appear intense. Even Alhaji Mutui of Owerri told of his inability, soon after his conversion in 1982, to shake off his bitterness for the Hausa because of his civil-war experience. He recalled:

I was a major in the Biafran army. During the campaign to liberate Owerri I fell into a trap and was captured by Nigerian soldiers. I was held at Owerri until the end of the war … Twice I was condemned to death during the war; twice I dug my grave to be buried alive … So, why should I love them?Footnote 81

He overcame his fear, however, and became one of the early converts to Islam in Enugu after the civil war. Mutui's case shows that memories dim with time, even though they hardly die. Generally, the Igbo exemplify this phenomenon clearly. Thirty-nine years after the Nigeria–Biafra War, many survivors (with differing degrees of vividness in their memories of the war) continue to share their experiences and this has not aided Islam in Igboland. The complicity in war crimes of Muslims of different ethnic groups deployed to south-east Nigeria to crush the Biafra rebellion was one potent factor militating against conversions to Islam in Igboland. It was not helped by the launching of various websites recycling civil-war stories of victimization, torture, and genocide against the Igbo by the armed forces of the Federal Government of Nigeria, members of which were drawn largely from northern Nigeria.Footnote 82 Alhaji Sani Ibrahim described Muslim and non-Muslim relationships in his town as follows: ‘Because of the Nigeria–Biafra War, Muslims and non-Muslims in this town have been cat and mouse ever since.’Footnote 83

Instances of conversion-related troubles in Igboland between 1970 and 1990 not only occurred in connection with conversions from Christianity and Igbo religion to Islam but also the other way round. Converts from Islam to Christianity narrated similar harassments and, in some cases, more serious outcomes, being threatened with death in addition to other punishments, in accord with the Muslim concept of Murtadd, which postulates that an apostate of Islam is qualified for death.Footnote 84 Hawakwunu described her marriage to an Igbo Christian in 1963 as ‘disobedience marriage’, on account of which she was disowned by her family.Footnote 85 A young male Muslim convert to Christianity said of his conversion in 1990: ‘The reactions from my relatives and friends were harsh. I was boycotted, denied, disowned, despised’.Footnote 86 Quite a number of converts felt intense pressure from those around them not favorably disposed to their religious switch. Mallam Ibeh, who became a Muslim in 1996, falls within this category. He narrated how strongly tempted he was to renounce Islam:

Each time I thought about how people treated me in this community, I felt like going back to the church. And each time I remembered my previous life of affluence, the friends I lost by becoming a Muslim, and many other things, I felt like renouncing my faith. The worst challenge was from my family … They want me to renounce my faith and go back to the Church and to my business …Footnote 87

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Islam may not as yet claim a huge following in Igboland, but it is making steady progress and conversions are taking place nonetheless. The benefits of conversion were summed up by Rambo as including gaining some sense of ultimate worth, participating in a community of faith that connects one to both a rich past and an ordered and exciting present, and generating a vision of the future that in turn mobilizes energy and inspires confidence.Footnote 88 These qualities would certainly make conversion a continuous human experience. The possibility, therefore, of completely blocking the conversion process in Igboland appears slim in the light of the strong forces of accelerated urbanization and global intermingling, both of which continue to foster mobility, social heterogeneity, and increased interaction between people of different religions and nationalities.