Japan before the World War II was, in some sense, more globalized than it is today. The ratios of exports and imports – as well as of capital inflows and outflows – to GDP in the period were higher than at present. Japan generally accepted more goods, services, and capital from abroad, and provided more goods, services, and capital to other countries.

This meant that more Japanese benefitted from globalization than they do now. Japan's globalization began with the Treaty of Peace and Amity between the USA and the Empire of Japan in 1854, which predates the Meiji Restoration of 1868, and was peacefully accelerated during the interwar period. But the liberal international order and free trade, which provided material and cultural benefits for Japan, collapsed at the end of the 1930s for ideological, economic, and historical reasons. I will explain these in turn.

This paper has four sections in addition to this introductory section. The first section gives a description of Japan's globalization before the World War II through comparisons with postwar trends. The second section explains the competing ideologies about free trade at the time. The third section analyzes the benefits of international trade and investment. The fourth section summarizes historical events that affected people's thinking about free trade and international investment. And the last section provides a conclusion.

1. Japan's Globalization before the World War II

After Japan opened its economy to the world in 1854, its external trade steadily expanded. As Figure 1 shows, the ratios of exports and imports to GNP were 5.2 and 5.6%, respectively, in 1885, but the shares increased to 10.7 and 13.8% in 1900. They expanded further to around 20% in the 1920s and early 1930s but declined to 5% in 1945. Following the World War II, they hovered around 15% after 1970, not consistently exceeding 15% until the 2000s. These figures suggest that Japan was more globalized before the World War II than it is today.

Figure 1. The ratios of exports, imports and current balance to GDP.

1.1 Japan's trade partners

What countries did Japan trade with? Figure 2 shows the major destinations of Japan's exports since the Meiji era, and Figure 3 shows the countries from which Japan imported. The major markets of Japan's exports were the USA and China (including Manchuria/Manchukuo). Japan's exports to the USA were larger than to China in 1929 (I am using 1929 rather than 1930 as the reference year since the 1930 data is affected by the Great Depression), declined in the early 1930s, slightly increased in the latter half of the decade, and subsequently decreased again. Exports to China, on the other hand, steadily increased, exceeding those to the USA in 1934.

Figure 2. Exports of Japan.

The decrease of the US share in the early 1930s can be explained by the Great Depression; as the US economy gradually recovered, the US share increased. The decrease at the end of the 1930s, meanwhile, can be explained by the growing antagonism in Japan–USA relations.

Figure 3 shows that Japan's imports from the USA were bigger than from China and India in 1929 and that this continued until 1940 just before the outbreak of the Pacific theater of the World War II in 1941. After that, of course, imports from the USA sharply declined.

In short Japan's trade depended almost equally on the USA and China until the 1930s, after which Japan came to depend on China for exports and on the USA for imports. This suggests that US exports to Japan included items like oil, scrap iron, and machine tools that were necessary for Japan to execute the war.

1.2 Trade items of Japan

What were Japan's major trading items? Figure 4 shows Japan's main exports and Figure 5 imports. The amount of each item is shown on the left-hand scale, while total exports and imports are expressed on the right-hand scale. Figure 4 covers Japan's main export items from 1900 to 1944. In 1929, Japan's main exports were raw silk and cotton fabric – the same items from 1900 to the end of the 1930s. The shares of raw silk to total exports were 36.4% in 1929 and 14.2% in 1939. The shares of cotton fabric and yarn to total exports, meanwhile, were 20.5% in 1929 and 13.3% in 1939.

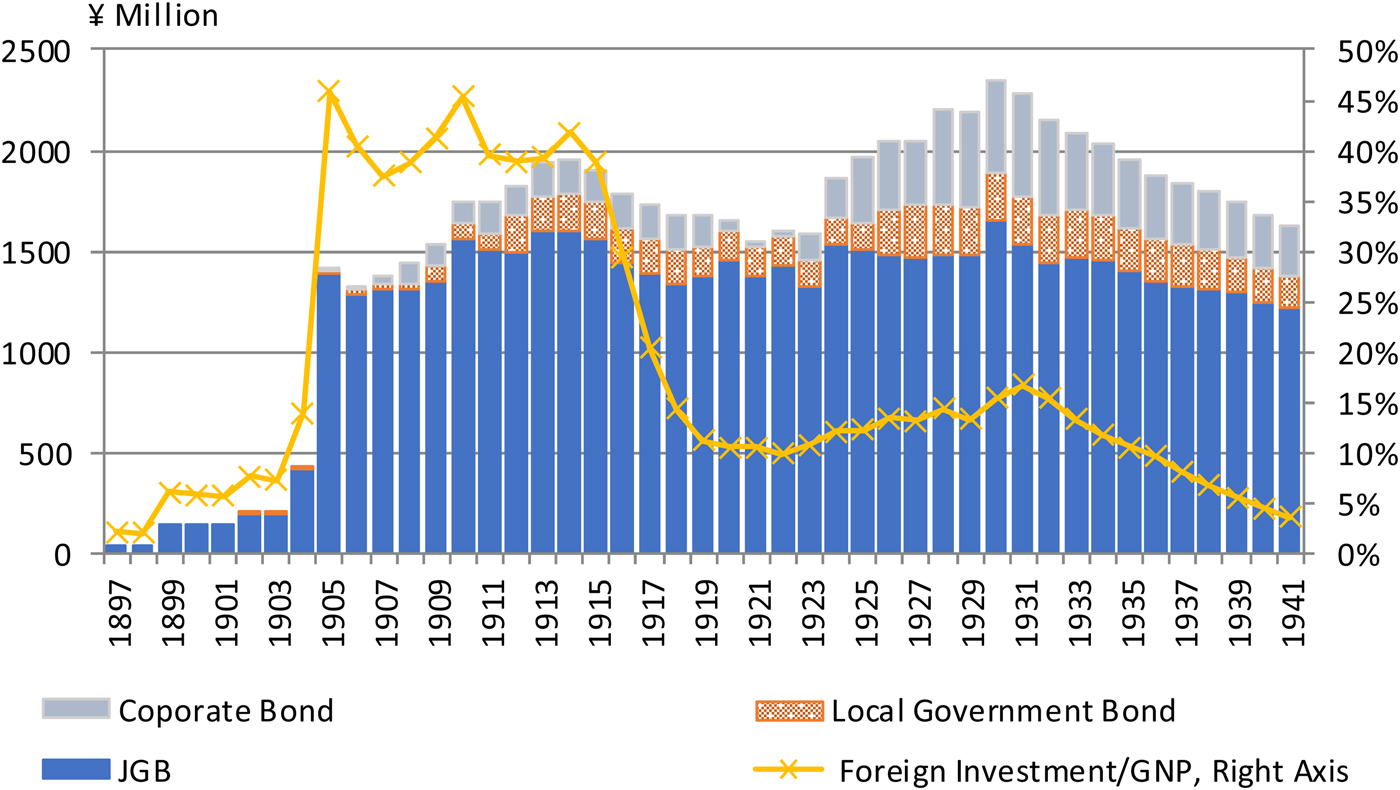

Figure 6. Outstanding of foreign investment to Japan.

Manufacturing exports other than cotton fabric and yarn were very limited. There are very few industries that may have been helpful for the war effort. I added values for cement, chinaware, iron and steel products, textile machines, vessels, and toys (cement can be used to build fortresses, and even the toy industry can make simple parts for weapons), but the values for these items were only 74 million yen in 1929 and 237 million yen in 1939. Their shares of total exports were just 3.5% in 1929 and 6.6% in 1939.

Products were manufactured for domestic use, of course, so the manufacturing base was larger than what export figures suggest, but being able to export means that products were internationally competitive in terms of both cost and quality. In the latter half of the 1930s, exports of manufacturing products other than cotton yarn and fabric rapidly increased, but this does not necessarily reflect improvements of Japanese products, because these exports mainly went to Manchukuo under Japan's orders and with Japan's financial assistance.

Figure 5 shows Japan's main import items from 1900 to 1944. In 1929 – as well as from 1900 to the end of the 1930s – Japan's main import was raw cotton. The share of raw cotton to total imports was 25.9% in 1929 and 15.8% in 1939. In value terms, Japan imported 439 million yen of raw cotton in 1929 and 573 million yen in 1939. Japan exported 462 million yen of cotton fabric and yarn in 1929 and 475 million yen in 1939, which are not so different from imports, with the import value actually being bigger than that for exports in 1939. This suggests that while Japan could not earn any foreign currency through cotton, people were able to consume cotton products. Only raw silk was a source of any significant foreign exchange for Japan.

Silk and cotton fabric and yarn are so-called light industry products that developed under free-market conditions, without significant support from the government (see Section 2 of this paper). In the latter half of the 1930s, Japan tried to support so-called heavy industries, but it was not necessarily successful (I will discuss the matter later).

1.3 Current balance and capital flow

In Figure 1, exports and imports are defined as shares of GNP and include travel, transportation, investment income, and other items. The difference between exports and imports thus nearly equals the current balance. The current balance is also the net capital outflow (a positive current balance means net capital outflow, and a negative current balance means net capital inflow).Footnote 1

Net capital flows before the World War II was larger than after the War. The average shares of the current balance to GNP were minus 2.3% in the 1900s (1900–09), plus 2.5% in the 1910s, minus 1.7% in the 1920s, and minus 0.4% in the 1930s. After the War, the ratios were 0.2% in the 1960s, 0.8% in the 1970s, 2.2% in the 1980s, 2.5% in the 1990s, and 3.4% in the 2000s (2000–09).

Additionally, the averages of the absolute values of these shares were especially high before WWII: 2.4% in the 1900s, 4.3% in the 1910s, 1.8% in the 1920s, and 0.9% in the 1930s, compared with 0.8% in the 1960s, 1.3% in the 1970s, 2.4% in the 1980s, 2.5% in the 1990s, and 3.4% in the 2000s. Since higher averages indicate a more active movement of foreign capital, such movements in the Japanese economy were more active in the 1910s and 1920s than in the 1980s; based on a different indicator, they were more active than even in the 2000s.

1.4 Capital outstanding

The figures in the previous section are of capital flows. If we look at capital outstanding, we can see that Japan before WWII was really globalized. The ratio of outstanding foreign investment (including bonds) in Japan to GNP in the first decade of the 1900s was more than 40%. It declined to around 10% in 1920 and gradually increased in the 1930s, before declining again thereafter.

The increase was caused by the Russo-Japanese War, and it declined because of the World War I. In the latter half of the 1910s, Japan exported its products to the world because of the war in Europe, earned foreign exchange, and repaid its debt. But, the decline in the value was small. The large decline in the share of outstanding foreign investment can mainly be explained by an increase in Japan's GNP (both the debt and GNP are expressed in yen terms).

The movement from 1900 to 1920 was affected by the War, but after 1920, the main reasons are economical. Japan welcomed foreign investment amounting to 15% of GNP.

1.5 Foreign direct investment

I could not find comprehensive data on foreign direct investment before WWII, but it was clearly important for the Japanese economy in that period. Table 1 shows foreign direct investment in the manufacturing sector at the end of 1931. New items, such as electricity, automobiles, petroleum, and rubber, found their way into Japan along with foreign capital.

Table 1. Foreign direct investment

Source: Mitsubishi Economic Institute, Nihon no Sangyo to Boekino Hatten (Development of Japanese Industries and Trades).

In concrete terms, General Electric injected capital into Tokyo Electric and Shibaura Manufacturing (the two became Toshiba through a subsequent merger in 1939) before WWI, and after WWI Westinghouse injected capital into Mitsubishi Electric. Siemens and Furukawa jointly established Fuji Electric. Ford and GM started knock-down production in 1925 and 1927, respectively. Imports of 1,000 cars a year were replaced by production of 29,000 cars by 1929. Dunlop established Japan Dunlop before WWI and monopolized Japan's tire market, but Goodrich and Furukawa established a joint company, Yokohama Rubber Co., and Shojiro Ishibashi, who made a fortune by producing rubber-soled socks with a separate big toe, established Bridgestone.

Japanese companies that invited foreign capital learned to design and production technologies, and got a chance to educate and train their engineers. These technologies spread to other companies, leading to the development of new industries. For example, tire production technology spread after engineers and skilled workers at Dunlop quit the company (Hashimoto Reference Hashimoto1989).

1.6 Japan's Assets Abroad and Foreign Assets in Japan after WWII

More detailed data are available for the period following the World War II. Figure 7 shows Japan's assets abroad, foreign assets (Liabilities in Figure 7) in Japan, their ratios to GDP, Japan's direct investment abroad, and foreign direct investment (in the form of stocks) in Japan since 1971.

Figure 7. International investment position of Japan.

The ratios of Japan's assets abroad and foreign assets in Japan were around 40–60% until the end of the 1990s. The ratio of foreign assets to GDP was less than 50% until 2004. The same ratio (bonds only) before WWII was already more than 40% in the middle of the 1910s.

In this sense, Japan can be said to have been more globalized before WWII than in the early 2000s. Many people no doubt benefitted from this state of affairs, with exports, imports, and foreign investments strengthening the value of the liberal international order, free trade, and free flow of capital for Japan. One would assume, then, that there were many advocates of free trade and investment. Producers who were not competitive with imports may have opposed free trade, but trade with other countries was promoted in accordance with the costs structure at the time. It was not possible to continue producing items at an internationally high cost. Silk and cotton industrialists made a fortune and had the power to influence government policy. Japan, however, failed to protect the liberal international order based on free trade. I will explore the reasons in the following sections.

2. Ideology

Japan is famous for its industrial policy under the direction of the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (now the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry), and many believe that the state has been actively intervening since the Meiji Restoration through subsidies, favorable foreign exchange allocations, tax credits, favorable loans, high custom duties, and other measures. But this is actually a misconception, as I will explain at the end of Section 4.

At the end of the 1880s, List, Friedrich's National System of Economics, which advocates protecting industries a nation needs and condemns free trade as a means of thwarting the industries of emerging nations, was translated into Japanese. His ideas, though, were circulated only among a small circle of academics, journalists, and bureaucrats (Morris-Suzuki Reference Morris-Suzuki1989).

Through the Meiji era, Japan's mainstream economic policy was the promotion of the free market and free trade, and this continued until 1930. Taguchi, Ukichi (1855–1905) advocates free trade in his Tokyo Keizai Zasshi (Tokyo Economic Journal) (Morris-Suzuki Reference Morris-Suzuki1989).

Tsuda, Mamichi (1829–1903) wrote, ‘It is generally accepted that among Western political economist that… tariffs, rather than provide protection, are bad measures injurious to the people generally’ (Braisted Reference Braisted1976, p. 56).

Matsukata, Masayoshi (1835–1924), leader of the Meiji Restoration, Minister of Finance, and Prime Minister, said, ‘The natural function of government is chiefly to protect the public interest and guarantee peace to the community. The government should never attempt to compete with the people in industry and commerce. It falls within the sphere of government to look after matters of education, armament, and the police, while matters concerning trade and industry fall outside its sphere. In fact, in these matters, the government can never hope to rival in shrewdness, foresight and enterprise men who are activated by immediate motives of self-interest.’ (Smith, Reference Smith1955, p. 95).

Additionally, Japan was deprived of tariff autonomy by unequal treaties with the Western powers toward the end of the Edo period. Japan recovered its autonomy in 1899, but even after that Japan did not employ a high tariff policy.

The ratio of tariff revenue to import value was less than 5% until 1899 and less than 20% even thereafter. Of course, the ratio is not a good indicator of tariff protection because it declines if some items are not imported because of an excessively high tariff rate. The tariff rate increased for some items in the latter half of the 1930s, but the average declined (Takeda Reference Takeda1977).

As shown in Figure 4 above, Japan's main export items were silk and cotton fabric, and these industries developed without protection. Several silks and cotton cloth plants were built by the Japanese government at the beginning of the Meiji era, to be sure, but these plants ran deficits and were sold off to private companies (Smith, Reference Smith1955).

2.1 Total war

A different situation appeared after WWI. During the War, Japan expanded its exports of industrial products to Europe, but after WWI, the European economy gradually recovered, and Japanese products were no longer in demand. As a result, Japanese industry suffered from excess capacity. But the impact of the decline in industrial exports was limited. During WWI, exports of iron, fiber machines, and ships exploded, but the share of these exports even at their peak in 1918 was only18.1% of silk exports in 1919 (silk exports in 1918 was particularly low).

It is true that these heavy industries asked for government protection, but such efforts were not successful. Even in 1940, when the government tried to divert capital from individual and corporate owners, business groups staunchly opposed such moves, and the government gave up (Nakamura, Reference Nakamura1980).

During the War, importing resources can become difficult, and this prompted the idea of developing a ‘power base.’ This is a base that can produce the goods necessary to execute the war. In the situation before WWII, China was in disarray, and there was no powerful central government. Japan's military leaders believed that China could become Japan's power base, and Japan acquired the Kwantung Leased Territory and various other concessions in Manchuria. China produced low-quality iron ore and coal but did not produce petroleum (which had not yet been discovered in China). Japan needed various resources, which not even the whole of China could produce. Japan's power base needed to expand indefinitely to meet all of Japan's resource needs. Naturally, the world turned against Japan.

The idea of protecting and developing industries became politically meaningful when it gained the support of the Japanese military. Military leaders were shocked by what they saw in Europe: the volume of bullets used, such new weapons as airplanes and tanks, and trucks carrying weapons and soldiers. They concluded that Japan, too, had to create an industrial base to produce bullets and new weapons and that the base must be mobilized for war if and when it occurred. The idea that emerged was total war, conducted not only by soldiers but by a nation as a whole.

In order to prepare for such total war, the government needed to control the economy and to create and expand military-related industries, such as iron and steel and those to build ships, airplanes, and automobiles.

The idea of turning one's back on the liberal international order may have been born during WWI, but it did not materialize until 1929.

2.2 An outlet for a surplus population

Another factor in the decision to reject the liberal international order was the notion that Japan had a surplus population and needed to house that population. The population in Japan today is declining, but at that time, it was growing rapidly, jumping from 34 million in 1868 to 43 million in 1898 and 62 million in 1928. Japan's population increased by 26.2% from 1868 to1898, and by 44.5% from 1898 to 1928.

Takahashi Kamekichi, a noted and influential economist at that time, argued that Japan was suffering from overpopulation. He wrote in 1927, ‘Japan is not so much ‘inevitably’ forced to fight for – raw materials. It is rather much more true to say that Japan is ‘inevitably’ forced to fight for an ‘outlet for its surplus population.’ (Takahashi Reference Takahashi1927, p. 1–44).

Takahashi argued that the world market was dominated by the Western powers and that Japan's fair entry into that market was being blocked, and as a consequence, it was impossible to find peaceful solutions for Japan's overpopulation.

On the other hand, Ishibashi, Tanzan clearly denied the need for an ‘outlet for its surplus population’ in an essay in 1921.

Ishibashi joined business publisher Toyo Keizai Shinposha in 1911 as a journalist and columnist and became president of the company in 1941. He was a leader of the Taisho Democracy movement who worked to strengthen the Diet and to establish a tradition whereby the head of the majority party forms a government; before then, the prime minister had been appointed by the privileged aides of the emperor. Ishibashi upheld the values of liberalism, individualism, anti-imperialism, anti-colonialism, and anti-militarism and argued that sovereign power resides with the people. While Toyo Keizai magazine had only a small circulation at a time when the total circulation of daily newspapers was 10.13 million (1930) and 13.27 million (1937) (Kase Reference Kase2011), it was read by business leaders and provided a forum for liberal and anti-militarism thinkers to voice their opinions. Ishibashi also established circles of Toyo Keizai readers called the Keizai Club all over Japan, sent lecturers there, and encouraged discussion among club participants. The number of clubs increased from 25 in 1941 to 41 in 1945. These activities were supported by businessmen and liberals. After the War ended, Ishibashi ran for election and failed, but became finance minister in 1946 (He got a seat in the member of the House of Representatives in 1947). He opposed the dissolution of the zaibatsu, cut occupation expenses for the US army, and was purged by the occupation authorities in 1947Footnote 2. The purge was dismissed in 1951, and Ishibashi became prime minister in December 1956 but resigned in February 1957 due to illness.’ (Kaisetsu (Explanatory Introduction by the editor), Matsuo (Reference Matsuo1991) and Masuda, Reference Masuda1995)

Ishibashi argued, ‘The value of trade with Korea and Taiwan was around 900 million yen, while that with the USA was some 1.4 billion yen, India was a little less than 600 million yen, and Britain was a little over 300 million. The USA, India, and Britain are necessary countries for Japan's economic independence. … Additionally, in Korea, Taiwan, and Manchuria, there is nothing that Japan essentially needs. The most important industrial material is cotton, but this comes from India and the USA. Among such important items as petroleum, coal, iron, and wool, nothing is mainly supplied by Korea, Taiwan, and Manchuria. Japan imported 57 million kin [Japanese weight unit, about 600 g] of iron ore from Manchuria, but Japan's total imports of iron ore reached 2.5 billion kin. It is foolish to make a fuss over such an amount. Japan acquired Karafuto (Sakhalin) decades ago, but it has not brought any economic benefits.

‘These territories have done nothing to resolve the population problem, moreover. There are 159,000 Japanese living in Taiwan, 337,000 in Korea, 181,000 in Manchuria, and 78,000 in Karafuto. These, together with the Japanese in China, totaled little less than 800,000.

‘The population of Japan as a whole, meanwhile, increased by 9.45 million from the period of the Russo-Japanese War (1904) to 1918. The increase of 800,000 in overseas territories is not even 10% of the total. There are 60 million Japanese people living on the mainland. The happiness of these 60 million should not be forsaken for the sake of the 800,000 living elsewhere.’Footnote 3

Of the increase in the population, what did the 8.65 million people who did not live in overseas territories do? They, of course, went to work at the shops, factories, and offices in Japan. The majority of the Japanese people were not persuaded by Ishibashi's arguments.

Konoe, Fumimaro, who was prime minister between 1937 and 1939 and again from 1940–1941, wrote in 1918, ‘In the world after the World War I, the ideas of democracy and humanism have undeniably flourished. For Japan, too, it is desirable to develop democracy and humanism. Regrettably, however, Japanese critics do not seem to understand the egoism that lurks behind their democracy and humanism; these values are considered equal to the demands of justice and humanity. The peace that the British and Americans advocate is a status quo that is convenient for them, and they glorify it under the name of humanity. … The UK and France have colonized under-civilized regions and monopolized those interests. All the ‘less developed countries’ [that is, developed countries that were late in acquiring colonies, such as Germany and Japan] were placed in a situation in which they were unable to get the land they needed. This situation threatens the equal survival of nations and is completely contrary to justice and humanity.’ (Oka Reference Oka1972).

In short, Konoe argued that wealth was gained by plunder and that it was impermissible for those who plundered first to justify the status quo with words of democracy and humanism. Those who did not gain wealth at first had the right to restart the plunder game again. While his words may have been imprudent, it suggested that Japan could not help but make war if it hoped to be rich.

Unfortunately, the Japanese people were more inclined to listen to Konoe than to Ishibashi. From our modern perspective, we believe that ideologies that reject the liberal international order, free trade, and the free movement of capital are not likely to prosper, but they were popular at the time, and an increasing number of Japanese people began embracing such ideologies.

3. Conflict of interests

The share of the trade to GDP during the interwar period reached as high as 40%, suggesting that there was considerable profit to be made from trade. Some may have benefitted by restricting trade if they were able to sell their products that had previously been imported. But having to pay a higher price does not benefit the nation as a whole. And in order to produce airplanes, ships, cars, and trucks – as well as tanks, air fighters, and battleships – Japan needed to import iron ore, aluminum, petroleum, and machine tools. Developing industries for a war power base does not necessarily lead to autarky.

The colonization of Taiwan, Korea, and Manchuria was not very profitable for most, although some did profit from them. Many Japanese in the colonies enjoyed affluent lifestyles. But their wealth was not necessarily derived locally. Japan was unable to levy heavy taxes on poor peasants in Taiwan, Korea, and Manchuria. Rice was exported to Japan by Taiwan and Korea, bananas by Taiwan, and soybeans by Manchuria. Importing rice made good economic sense, but this lowered domestic rice prices, and Japanese farmers suffered as a result. Today, Japan is reluctant to import rice. Did people back then think that importing rice was one of the benefits of having colonies? Obtaining new sources of soybeans, meanwhile, was not enough to make most people glad about Japan's colonial acquisitions.

On the contrary, the Japanese on the mainland needed to support the 700,000 soldiers in Manchuria. The soldiers required food, clothing, and weapons. These items cost a lot of money, and many Japanese in Manchuria depended on the military for their survival. This money came from taxes paid by people in Japan. The military secretly entered into a contract with the local government calling for it to pay the Japanese military the cost of defending and maintaining peace and order in Manchukuo, but Japan decided not to accept payments in 1933 (Furumi Reference Furumi1978). Then, who paid the costs? It was the taxpayers in Japan. While the Japanese colonies did not produce much wealth for Japan as a whole, some Japanese did get good salaries from Japanese taxpayers.

For example, Muto, Tomio, a 30-year-old Tokyo district court judge in 1933, wrote later that he was paid an annual salary of 6,500 yen. This, at the time, was the same amount as the chief justice of the Supreme Court (Muto Reference Muto1988). Manchukuo could not hire Japanese with expertise without paying such a high salary. That such people were hired suggests, moreover, that unemployment was not serious in 1933.

3.1 What benefits did colonies bring?

Then, how much wealth did the colonies bring to Japan? First, I will examine the size of the colonial economies compared with Japan. In 1937, the net domestic products (NDP) of Japan, Taiwan, Korea, and Manchukuo were, respectively, 20,965 million yen, 925 million yen, 2,786 million yen, and 4,129 million yen (Yamamoto Reference Yamamoto1992). The respective NDPs of Taiwan, Korea, and Manchukuo were just 4.4, 13.2, and 19.7% of Japan's. I have omitted figures for other colonies, such as Karafuto, Nanyo, and Kantoshu, because of their negligible size.

They registered strong growth, however. The annual average growth rates of real GDP for Japan, Taiwan, and Korea were 3.31, 4.41, and 3.68%, respectively, from 1911 to 1938.Footnote 4 Per capita real growth rates for Japan, Taiwan, and Korea, meanwhile, were 1.95, 2.43, and 2.11%.Footnote 5 The benefits of economic growth were absorbed by increases in population, though, with per capita income growths being about 2%. Growth rates before WWI were quite high compared with other countries, with world per capita real growth from 1913 to 1940 (data from 1911 to 1938 was not available) being only 0.9%, according to Maddison (Reference Maddison2008) (later revised to 1.3%).Footnote 6

While I was unable to find real GDP data for Manchukuo, I did locate nominal national income (NI) statistics from 1937 to 1943 (Yamamoto, Reference Yamamoto2003). If the nominal NI is deflated using a retail price index (Yamamoto, Reference Yamamoto2003, Table 2–5 (1), (2). The two price index series are connected in 1941), the NI in ‘real terms’ increased 1.27-fold from 1937 to 1943 (Annual growth rate is 4.1%). The population increased 1.21 times over the same term, so per capita ‘real’ NI increased 1.05 times, whose annual growth rate is 0.8%. This was not remarkable growth.

Additionally, Japan invested 1.156 billion yen from 1932 to 1936, and 4.702 billion yen from 1937 to 1941(these are nominal figures) (Yamamoto, Reference Yamamoto1992, Table 3-3). The NDP of Manchuria was 4.129 billion yen in 1941, as I mentioned, so investment grew more than fourfold during the latter 4 years, and average investment for 4 years was 1.176 billion yen. So, per capita ‘real’ NI grew at only 0.8% annually even spending 28% (1.176/4.129) of NI. This means that the investment is inefficient.

Did these growth figures in its colonies really benefit Japan? One measure of tangible benefits would be the difference in the wages of Japanese in the colonies and those in Japan, and the difference in returns on investment in Japan and in the colonies.

First, I will look at worker wages. As I stated earlier, there were 149,000 Japanese living in Taiwan, 337,000 in Korea, and 181,000 in Manchuria. Japan's total population was 68 million. Since the total in the three colonies was 667,000, they accounted for only 1% of the Japanese population. This means that even if the Japanese in the colonies earned twice as much as those in Japan, this would only boost Japan's GDP by 1%.

Second, as for returns on Japanese investments in the colonies, they might be higher because real growth rates were higher in the colonies. But the actual difference was about 1% at most. Japan's capital stock (government and private) in Taiwan was 2.1 billion yen in 1943, that in Korea was 7.2 billion yen in 1940 (Yamamoto, Reference Yamamoto1992), and the sum of investment from 1932 to 1941 was 5.9 billion yen in Taiwan and Korea, and 4.7 billion yen from 1937 to 1941 in Manchukuo, giving a total of 19.9 billion yen, 1% of which is 199 million yen, while I do not think return on investment in Manchukuo was higher than that in Japan. This is only 0.5% of GDP, as Japan's GNP was 36.9 billion yen in 1940 (Okawa et al. Reference Okawa, Nobukiyo and Yuzo1974, Table 8).

Therefore, the economic benefits of holding the colonies were a boost of only 1.5% of GNP. Japan could have invested in these territories even if it had not colonized them. The 1.5% figure is a maximum estimation. Japan spent 15.1 and 22.5% of GNP in 1937 and 1940, respectively, for military defense to protect its tiny colonial benefits (Emi and Yuichi, Reference Emi and Yuichi1966, Table 10 Total [A], for military defense expenditure. For GNP, See Okawa .Kokumin Shotoku, Table 8.).

Of course, some may argue that Japan benefitted in other ways, such as by confiscating land or buying land by deceiving the landlords and peasants in Taiwan, Korea, and Manchukuo. This might have happened, but I could not find any evidence of how much land Japanese acquired at rates lower than the market price. In Manchukuo, Japan first tried to buy land at lower prices, but the landowners and peasants rebelled; Japan thus raised the purchase price, and after the leader of the biggest rebellion, Xie Wendong, was freed, he came to cooperate with Japan (Muto Reference Muto1988). This suggests that Japan ultimately bought land at market prices. After the Communist Party of China took power, however, Xie was executed for cooperating with the Japanese military.

Another benefit may have been that Japan could monopolistically export its heavy and chemical products to the colonies, such as metal products and machinery. Japan exported 1,159 million yen of heavy and chemical products to the world in 1937, of which 744.8 million yen, or 64.5%, went to the colonies (Yamamoto Reference Yamamoto1992). If these areas had not been Japan's colonies, they could have imported from other countries. The value, however, was only 744.8 million yen – just 3.5% of Japan's GDP. A significant share of the imports from Japan, moreover, was purchased by the entities set up by the Japanese government and private companies in the colonies.

Japan could export to the colonies at favorable conditions, giving Japan a trade surplus with those territories, but Japan ran a deficit with other areas (Yamamoto Reference Yamamoto1992). Japan made the colonies use the yen, so Japan earned yen through its exports but no foreign exchange. Japan continued to suffer from foreign exchange shortage. Nakamura points out that Japan's international balance was in danger (Nakamura, Reference Nakamura1980)

Kiyosawa, Kiyoshi wrote in 1929, ‘The Tanaka administration sent an army to Jinan, China, to protect the properties of 2,000 Japanese there, whose total worth was 570,000 yen. This was a so-called vital interest for Prime Minister Tanaka, for which Japan wound up expending 37.74 million yen. Spending 37.74 million yen to protect 570,000 yen's worth of property would be unthinkable in Japan. Japan also offered favorable loans that were not to be returned, as Japanese businesses were not in good condition, including 4.2 million yen for the Qingdao and Yangtze areas – 3 million yen for Qingdao and 1.2 million yen for Yangtze – although only 17,000 Japanese were living in Qingdao. If the Japanese government gave the same amount of money to all citizens, it would cost nearly 200 yen per person (Per capita GNP in 1929 was only 260 yen) (Okawa et al. Reference Okawa, Nobukiyo and Yuzo1974).

‘In Hankou, there are only 1,000 Japanese, but 550 soldiers and five battleships were dispatched. Four soldiers, four machine guns, and 20 light machine guns were sometimes required to protect each Japanese citizen.

‘What are Japan's main interests in Manchuria and Mongolia? The most important property is the South Manchurian Railway Company, with property worth 355 million yen. This is slightly larger than total deposits at Mitsubishi Bank in Japan. Would the Japanese government protect this company with an army division?’ (Kiyosawa, Reference Kiyosawa2002)Footnote 7, Footnote 8

Protecting one's international rights is a legitimate undertaking, but Japan at that time should have compared the costs and benefits. Kiyosawa proposed more reasonable solutions in his essay.

4. Was it possible to maintain the liberal international order before WWII?

Even before the World War II, the liberal international order based on free trade was possible. Japan was a beneficiary of free trade, and it needed natural resources, advanced technologies, and markets. Japan's colonies and China, which Japan tried to colonize, could not provide such essential natural resources as iron ore, coal for refining steel, and petroleum oil for war. In peacetime, they could neither provide cotton for industrial materials nor markets for Japanese silk. Japan imported resources from the USA and India and technologies from the USA, UK, and Germany. Japan expanded its markets to Asia, the USA, and Europe, but the USA was still the most important market in the first half of the 1930s, especially for silk exports.

It is true that Japan's exports were blocked by protectionism in the USA and the British Empire, but the effects are often exaggerated. Japan's export index (1926 = 100) increased from 91 in 1929 to 97 in 1937, while the world export index decreased from 94 in 1929 to 44 in 1937 (Ikeda, Reference Ikeda1992, Table 1-1). Japan's exports to China and Manchukuo increased in the latter half of the 1930s, but it was for the development of Manchukuo, such as railroad trains and rails, metal products, motors, and machinery. Japan mainly imported soybeans.

This was a period when Japan, too, lacked infrastructure. Japanese cities and rural area asked the central government for an expansion of the railroad network. Japan did not need to build up industry in Manchukuo when infrastructure was in need of improvement in Japan.

So, the benefits of having colonies were small, as I wrote in the previous section, but Japan took the path of autarky and a controlled economy, bent on disrupting the liberal international order. Wilsonian-Taisho moment was lost in the latter half of the 1930s.

4.1 Road to Autarky

The government and the military tried to introduce laws on controlling the economy, but they could not do so because the business sector was opposed to such laws, arguing that they were socialist and violated the constitutional guarantee of property rights for Japanese subjects.

Such laws were gradually enacted despite the opposition in the latter half of the 1930s.

This can be explained by three factors. One is that people came to distrust capitalism and big business because of the Showa Depression in 1929, which was the Great Depression in Japan. The Depression in Japan was not so severe as in the USA and Europe, but it was still a shock for ordinary people who trusted the establishment and earned their living with their labor. Silkworm peasants saw the price of their products shrink by half, even though their debts remained the same.

Second, the military launched the Manchurian Incident in September 1931. Twenty thousand Japanese soldiers pushed over 300,000 Chinese soldiers who were governing the area, and created Manchukuo, a Japanese puppet state in March 1932. These 20,000 soldiers (the number increased to 740,000 in 1941) controlled a land of 60 million peoples. The Japanese people believed that this land would bring a fortune to Japan, and this enhanced the power and prestige of the military.

Nakamura, Takafusa, an authority on Japanese economic history, wrote, ‘The Manchurian Incident was reproached internationally, but in Japan, many people thought – albeit briefly – that something new would happen and that the state of depression would change. It cannot be denied that the incident was recognized in a positive light. This suggests, though, how gloomy the economy and society must have been at the time, and how many people welcomed any signs of change.’ (Nakamura, Reference Nakamura1986, p. 63).

Third, a faction of young military officers made two coup d’état attempts, killing opposing ministers and politicians in 1931 in 1936. The attempts failed, and the officers were executed, but the military's voice became strong, and politicians opposing the military were oppressed.

Military expenditures were expanded to 3.5 billion yen, which was larger than Japan's total national budget of 2.7 billion yen in1937 (Emi and Yuichi, Reference Emi and Yuichi1966)Footnote 9. In order to restrain inflation, the government introduced direct control of the economy. In the same year, the Temporary Fund Adjustment Act and the Temporary Measure Act on Exports and Imports, which allocated finances, imports, and foreign exchange for military use, were enacted. People could not get enough money for daily expenses, but at least inflation was temporarily oppressed (pent-up demand exploded, though, after the end of WWII). The next year, in 1938, the National General Mobilization Law was enacted, and it became possible for the government to mobilize workers, decide wages and labor conditions, control activities of private companies, and allocate bank assets. A controlled economy was completed by the end of the 1930s (Nakamura, Reference Nakamura1980).

The new laws, however, did not necessarily lead to the development of the military industry. Nihon Seitetsu, a big iron and steel company created through the merger of several iron and steel companies, tried to increase prices by limiting production facilities, and the result, at the beginning of the Pacific War, was a steel shortage in Japan (Miyazaki and Osamu Reference Miyazaki and Osamu1989). This was the reality of Japan's industrial policy.

Flath, David writes, ‘Perhaps the army's control faction and other like-minded architects of the wartime industrial policy incorrectly perceived the true nature of a price system, that it induces economically efficient choices without the need for central direction. Or perhaps, instead, they correctly perceived the nature of politics. By erecting a broad and intrusive, but opaque, mechanism for shifting private resources to the war effort, Japan's leaders effectively removed government procurement from the arena of public debate, and veiled the true economic costs of the war behind a cloak of secrecy.’ (Miwa, Reference Miwa2008; Flath, Reference Flath2014, p. 210; also argues that Japanese military government failed in efficiently mobilizing productive capacity for war.)

Tokutomi, Soho, who was a journalist, historian, and admirer of militarism in the 1930s, admitted that a military-controlled economy was not only inefficient but also unfair. He wrote after the War, ‘A military equipment company sent a document asking to supply the army with a certain product, but an army officer simply put the document into his desk; the company had offered bribes to the navy, but not to the army … Work at the bureaucracy is neither for the people nor for the bureaucracy itself. For whom do bureaucrats work? They work primarily to amass a personal fortune, and, secondly, to protect their own and their families’ interests. It was in such a situation that Japan had to begin a war by staking the survival of the nation on a German-style controlled economy, which only caused confusion. There were only a few retired generals who did not work as advisors or managing directors of private companies and were not involved in making money. Most earned more than ordinary businessmen.’ (Tokutomi, Reference Tokutomi2006, p. 177, 184, 218).

People in street said, ‘To get along the world, stars (means army), anchors (navy), black market, and connection are required, and only honest men lose.’

The militarization of industry did not necessarily mean autarky. Japan had to import iron ore, petroleum, and machine tools. Japan had to import machine tools from the USA, the UK and Germany. The development of heavy industry did not enable Japan to deny the free trade.

Japan's Zero fighter was processed by American machinery. Without trade, Japan could not prepare for war. The precision of the production process declines as the machines become old, so the performance of the Zero could not help but decline.

Conclusion

Japan during the interwar period was more globalized in many ways than it is now. Japan prospered under the liberal international order based on free trade and the free movement of capital.

The Japanese people at the time believed that the country needed more land overseas to feed the increasing population, but as Ishibashi pointed out, less than 10% of the increase in the Japanese population was outside of Japan, the growing mainland economy gave jobs to the other 90% of the population.

The benefits the colonies conferred were not great, as Ishibashi and Kiyosawa pointed out, but some Japanese, particularly military and civil personnel in the colonies were major beneficiaries. Those investing in the colonies also benefited, but a significant share of products was supplied to the Japanese military and civil servants. This, therefore, did not lead to benefits for Japan as a whole.

Japan was among the first to recover from the Great Depression, and by the middle of the 1930s was in a full employment situation.Footnote 10 Japan did not need to export its population to other countries or to acquire territories through military action.

It is true that Japan suffered from the protectionism resulting from the Great Depression, but the damage has been exaggerated, as Japan was able to expand its exports in the 1930s. Japan was also able to import petroleum, scrap iron, and machine tools – which were necessary for Japan to strengthen its military – from the USA until 1940. Japan may have continued to import these products if it had avoided a useless military expansion in China.

The military expansion into China and the shift to a controlled economy in Japan and Manchukuo benefitted those who supplied goods to the military and obeyed the authorities. Of course, the military got benefits, too. Such benefits, though, came at the expense of Japanese taxpayers and consumers, who were oppressed and were unable to criticize the military.

The benefits gained from the military clampdown and a controlled economy were quite visible, but the benefits of the liberal international order often cannot be clearly seen. This may be akin to the heavy media coverage about the losses incurred by farmers from the agreement on the TPP (Trans-Pacific Partnership) and the scant attention given to benefits for consumers.

Japan still had a chance to recognize the true benefits of the liberal international order and the false benefits of colonization, military expansion, and a controlled economy had they listened more closely to the likes of Tanzan Ishibashi, Kiyoshi Kiyosawa, and others like them. Wilsonian-Taisho moment, however, was lost in the latter half of the 1930s.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to helpful comments from Professor Takashi Inoguchi and participants of the conferences on this theme held on 9 January 2016, 14 October 2016, and 9 March 2017. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent the organization that he belongs to. All the remaining errors are my own.

Harada Yutaka After graduation from the University of Tokyo in 1974, he joined Economic Planning Agency, the Government of Japan. He got M.A. in Economics from University of Hawaii, and Ph. D. in Economics from Gakushuin University. He worked as Directors of Overseas Research Division and Social Research Division, Economic Planning Agency, and Vice President, Policy Research Institute, Ministry of Finance, Chief Economist and Senior Managing Director, Daiwa Institute of Research, Professor, Faculty of Political Science and Economics, Waseda University, and others. He has been Member of the Policy Board, Bank of Japan since 2015. His books are Basic Income, Why are There Many Poor People in Japan, Empirical Studies on Prolonged Stagnation (with HAMADA Koichi and others), Principles of Japan awarded Ishibashi Tanzan Prize, Studies on the Showa Depression (with IWATA Kikuo, and others) awarded Nikkei Prize for Excellent Books in Economic Science and Theory, Japan's Lost Decade, and others.