1. Financial crisis and provincial financial autonomy

Chinese authoritarianism is fragmented (Lieberthal and Oksenberg, Reference Lieberthal and Oksenberg1988; Mertha, Reference Mertha2009), especially so with regard to the relations between the central and local governments. On the one hand, the cadre responsibility system ensures hierarchical political control of Chinese government officials (Takeuchi, Reference Takeuchi2014; Burns, Reference Burns2019). On the other hand, since the market-oriented reform in the late 1970s, Chinese local governments have gained greater autonomy in administering their economic affairs (Oksenberg and Tong, Reference Oksenberg and Tong1991).

The literature on Chinese political economy shows that economic decentralization helps sustain China's fast economic development, because it creates more regional competition and policy experiments (Montinola et al., Reference Montinola, Qian and Weingast1995; Cao et al., Reference Cao, Qian and Weingast1999), hardens local budget constraints (Qian and Roland, Reference Qian and Roland1996, Reference Qian and Roland1998), and increases local officials' incentives to produce higher economic growth (Li and Zhou, Reference Li and Zhou2005). This reform fostered a close tie between the state and business (Chen, Reference Chen2002; Tsai, Reference Tsai2007), as reflected in the term ‘local state corporatism’ (Oi, Reference Oi1992). Over the course of the reform, the local state's autonomy relative to business has declined and in some regions, its relationship with enterprises has turned into clientelism (Ong, Reference Ong2012). Central state capacity has also shrunk as local states gain more discretion over their financial resources (Wang, Reference Wang and Walder1995). Chinese central leaders, especially during the 1980s and 1990s, have never unanimously supported marketization and decentralization (Cai and Treisman, Reference Cai and Treisman2006), leading to the ebb and flow of local economic autonomy.

Previous research on Chinese central–local relations has identified two different logics of local leadership selection (Bulman and Jaros Reference Bulman and Jaros2020). Based on the logic of central control, the center should appoint the most loyal and trustworthy officials, who often reside in Beijing and lack local political experience, to regions vital to national security and economic growth. However, the logic of responsive governance emphasizes the values of native officials' local experience and ties for accommodating various local needs and asks for their appointment in their home provinces. Existing research examining post-reform personnel data has generally supported the logic of responsive governance (Zeng, Reference Zeng2016; Bulman and Jaros, Reference Bulman and Jaros2020). In the reform era, officials not locally rooted are shown to be indecisive and conservative toward economic policies (Cheung et al., Reference Cheung, Chung and Lin1998). In contrast, native officials tend to keep a cooperative relationship with their local colleagues and have strong incentives to facilitate economic reforms. The central government is thus willing to grant local governments more discretion over local economic affairs at the cost of central control (Zeng, Reference Zeng2016). As the reform proceeded in its early stage, a greater proportion of native officials started to occupy critical local leadership positions. The economic reform altered the power distribution between the central state and the local state.

Economic independence is likely to translate into the political power of provincial governments. Political leaders of rich provinces possess strong bargaining power with the central government to the extent that they have access to affecting national policy and politics. In the early years of the reform, Deng Xiaoping and his allies tried to allocate a large proportion of the Central-Committee membership to provincial leaders, making them the largest bloc in the body of supreme authority of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The initial intent to empower provincial officials, who had invested interest in promoting financial decentralization, was to create a political counterweight to conservative central bureaucrats and to sustain the momentum of the reform. An unintended consequence was that it pushed decentralization with a ratchet, for provincial leaders became obstacles to any initiatives to recentralization (Shirk, Reference Shirk1993). An example is the 1994 fiscal reform, an effort to replace the fiscal contract system with the revenue-sharing system in order to increase the central government's share of local revenues. Although this reform was eventually carried out, it was delayed for many years because of strong opposition from a group of provincial governors (Chung, Reference Chung1994).

Crises often break the power equilibrium between central and subnational governments. In most cases, external crises enhance state autonomy, centralizing state authority over the personnel management of bureaucrats (Bulman and Jaros, Reference Bulman and Jaros2020). For instance, Victor Shih (Reference Shih2008) has shown that when confronted with the threat of inflation, provincial leaders are more willing to hand over their discretion over provincial fiscal affairs to the central government because they are less experienced and less capable of combating inflation.

The 2008 global economic crisis heavily struck the Chinese economy, significantly slowing down its economic growth. In November 2008, the central government announced an investment plan that involved 4 trillion yuan (approximately 586 billion dollars). Its purpose was to restructure the Chinese economy to be more dependent on consumption rather than international trade and investment. After 2008, budget deficits rose to a high level for most provincial governments, and local economic growth became more reliant on financial support from the central government. According to the financial data released by the National Bureau of Statistics, except for Beijing, deficits increased in all Chinese provinces from 2007 to 2008, with the average increase rate at 41%.Footnote 1 In 2012, the provinces of the highest GDP growth – such as Guizhou and Yunnan – were also those suffering a very high rate of budget deficits.

Increased provincial deficits lead to a higher degree of financial dependence on the central government. On the one hand, the central government faces less local resistance when it intends to intervene in local politics. On the other hand, a province deep in debt has lower political clout in the central institutions of the CCP. In this paper, we will examine these two consequences of deficits by analyzing the enforcement of the law of avoidance and provincial representation in the CCP Central Committee.

2. Political centralization and Chinese federalism

Yingyi Qian and Barry Weingast popularized the term of Chinese-style federalism through a series of research on Chinese fiscal decentralization during the reform era (Montinola et al., Reference Montinola, Qian and Weingast1995; Qian and Weingast, Reference Qian and Weingast1997; Jin et al., Reference Jin, Qian and Weingast2005). But, China has also achieved a higher level of federalism in terms of political institutions (Landry, Reference Landry2008). As Jonathan Rodden argued, federalism is a ‘process – structured by a set of institutions – through which authority is distributed and redistributed’ (Rodden, Reference Rodden2004: 489). An essential feature of Chinese local politics is a shared authority (tiaokuai). A local party organization is often subject to both its counterpart at a higher level and the local party committee. For example, provincial party disciplinary inspection commissions follow the leadership of both provincial party committees and the Central Disciplinary Inspection Commission (Manion, Reference Manion2004; Guo, Reference Guo2014). Another example is the 1983 reform of party cadre appointment that the two-levels-down system was replaced with the one-level-down system. From then on, provinces have been able to appoint bureau-level officials without approval from Beijing,Footnote 2 but Beijing still firmly controls the appointment of (vice-)ministry-level officials, including all provincial-standing-committee members. With tight personnel control, the central government is able to constrain local governments' behavior, for example, to hold their zeal for myopic investment (Huang, Reference Huang1999).

Mirroring the Central Committee, provincial party committees make decisions over important economic, social, and political affairs in their jurisdictions. The core of a provincial party committee is its standing committee. Most provincial standing committees consist of 13 members, among which the top two are the provincial party secretary and governor. The official rankings reflect provincial officials' seniority as well as the importance of their positions. According to the CCP constitution, provincial committee members elect provincial secretaries, vice secretaries, and standing-committee members, but the Central Committee reserves the right of vetoing the election results.Footnote 3 Such an institutional arrangement allows both provincial and central leaders to affect the composition of provincial standing committees.

As some China scholars have observed, factionalism prevails in the CCP central institutions, but it plays a less dominant role in local governments (Nathan, Reference Nathan1973; Shih et al., Reference Shih, Adolph and Liu2012; Landry et al., Reference Landry, Lu and Duan2018). Central party leaders are alert with local officials' efforts to form a clique and thus try to enforce the law of avoidance, that is, the law of preventing officials from taking crucial positions in their hometowns (Li, Reference Li and Joseph2010: 185). Nevertheless, when choosing new provincial-standing-committee members, provincial officials tend to support the candidates who have social ties with them, because they have less trust in strangers than their family members, fellow townsmen, classmates, and acquaintances. In this sense, the preferences of provincial officials and central leaders are conflicting over the composition of provincial standing committees.

The law of avoidance has become a major norm in the CCP, but its enforcement varies across provinces. If a province suffers a high level of deficits and economic dependence, it will be less resistant to the central government's intervention in its local politics. The central government thus can effectively break cliques established on native ties by manipulating the rankings of the provincial-standing-committee members. Here, we propose two hypotheses with regard to the enforcement of the law of avoidance.

H1. The number of birthplace ties is negatively associated with the ranking in the provincial standing committee. As the provincial deficit rises, the negative effect of birthplace ties is enlarged.

H2. Native members in the provincial standing committee are more likely to be ranked below non-native members, especially so in provinces with a large deficit.

Federalism resembles a contract that holds each side obligated to one another. Thus, one important dimension of federalism is the degree of local officials' involvement in national politics (Rodden, Reference Rodden2004). The CCP has put effort to increase the representation of diverse interests, including different regional interests. Most Chinese central leaders have governing experience in multiple provinces. In the current Politburo, for example, six out of 25 members also serve as provincial party secretaries, representing Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Chongqing, Guangdong, and Xinjiang.

The Central Committee is bestowed with the highest authority of the CCP, where almost all provincial party secretaries and most provincial governors enjoy full membership and a few lower-ranking members of the provincial standing committee have a chance to receive alternate membership. Full members of the Central Committee have the right to participate in national decision-making, such as electing Politburo members and revising the CCP Constitution. In terms of full membership, every province receives approximately equal representation in the Central Committee, whereas in terms of alternate membership, the representation is skewed. In November 2012, the 18th National Party Congress elected 171 alternate Central-Committee members, among which five members represented Zhejiang province but only one represented Hebei province.

We argue that the low representation of certain provinces to some extent is attributed to their poor economic performance and high fiscal dependence on Beijing. If a province is not able to make ends meet, it loses not only the power to resist the control of the central government but also the channel to affect national politics. Here, we propose a hypothesis on the relationship between provincial deficits and representation in the Central Committee.

H3. If a province is confronted with a high deficit, its standing-committee members will have a low likelihood to be elected into the CCP Central Committee.

3. Data and measurement

We collected profiles of all provincial-standing-committee members in 2013. The main data source is the Chinese Officials Database accessed from www.ifeng.com. This database provides the basic biographical and career information on most high-ranking local officials. To fill in the missing cases, we turned to the Database of Chinese Party Cadres and Government Officials accessed from www.people.com. Provincial standing-committee members as regional military officials were excluded in the dataset because they are subject to a separate personnel management system, and their public career profiles are often incomplete. The dataset for our final analysis includes 365 provincial-standing-committee members.

3.1 Provincial-standing-committee ranking

The ranking of provincial-standing-committee members (Ranking) is measured as an ordinal variable ranging from 1 to 13 for most provinces. But, in two ethnic autonomous regions, Xinjiang and Tibet, there are 15 standing-committee members, where the upper limit of this variable is 15. Note that Ranking is negatively correlated with political status. Ranking is coded as one for provincial party secretaries, the most powerful local officials. Ranking is often coded with a high number for the most trivial government positions.

3.2 CCP Central-Committee membership

The membership in the CCP Central Committee (Membership) is measured as a variable containing three categories: alternate, full, and Politburo membership. It should be a nominal rather than ordinal variable because the selection criteria vary across the three levels of Central-Committee membership. For example, the electorate of alternate and full members of the Central Committee is the delegates of the National Party Congress, whereas the electorate of Politburo members is Central-Committee full members.

3.3 Provincial deficits

The provincial deficit is defined as the difference between provincial spending and revenue. It is measured based on the financial data released by the National Bureau of Statistics of China. We examined the provincial budgets between 2008 when the global financial crisis hit China, and 2012 when the 18th Central-Committee transition took place. Provincial deficits are measured based on the following equation, where ![]() $\sum\nolimits_{t = 2008}^T {Spending} $ and

$\sum\nolimits_{t = 2008}^T {Spending} $ and ![]() $\sum\nolimits_{t = 2008}^T {Revenue} $ indicate aggregate provincial spending and revenue over the years between 2008 and T Footnote 4:

$\sum\nolimits_{t = 2008}^T {Revenue} $ indicate aggregate provincial spending and revenue over the years between 2008 and T Footnote 4:

There is a geographic pattern of provincial deficits. The coastal provinces were relatively solvent, a majority of which had a deficit below 50%. During the reform era, these provinces were the leading forces of economic opening and development. In most inland provinces, the financial risk was moderately serious, where the deficit was kept below 200%. The deficit was highest in the provinces dominated by ethnic minorities. It was also very high in Northeast China, the declining industrial center established before the market-oriented economic reform. Additionally, the level of deficits is highly correlated with provincial GDP per capita with the correlation coefficient at −0.40, statistically significant at the 95% confidence level. This shows that less developed regions in China tend to be more heavily indebted and fiscally dependent.

3.4 Birthplace ties

The first measure of birthplace ties is a count variable, namely the number of fellow standing-committee members born in the same province. This measure is equivalent to degree centrality, which is a network metric describing the structural importance (Freeman, Reference Freeman1979). Based on our data, provincial-standing-committee networks were sparse with the median of birthplace ties at one and 37% of the members without any birthplace ties. However, such a network was dense in Shandong province with the median at four. One may expect that native officials are most likely to be the largest part of their provincial standing committees. However, this is not always the case. For example, in 2013, officials born in Zhejiang province dominated in the Shanghai standing committee. The central leaders try to restrict provincial officials from establishing a large local clique, whether they are native or non-native to the province under their administration. The second measure of birthplace ties is a binary variable, indicating whether one works in his or her birth province. In 2013, out of each provincial standing committee, four members on average were native (about 30%). There was a wide range in the proportion of native officials in the provincial standing committee. In Shandong province, eight standing-committee members were native, whereas in Shanghai, Tianjin, and Hainan, only one was native.

3.5 Demographic characteristics

Provincial officials vary in their demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and ethnicity (see Appendix 1). Based on our data, the average age was 52 when one became a provincial-standing-committee member. In 2013, out of 365 members, only 36 were women. Women's representation was highest in Jiangsu province with three female standing-committee members; it was lowest in Shanghai and Tibet without any female members. Approximately 10% of provincial standing-committee members were ethnic minorities from 13 ethnic groups, especially Tibetans (9), Hui (8), Mongols (6), and Uyghurs (4). This percentage corresponds to the national ratio of ethnic minorities to the Han (China's ethnic majority). Most minority members were concentrated in three ethnic autonomous regions, Tibet, Xinjiang, and Inner Mongolia, where they constituted more than a one-third in respective provincial standing committees. Some minority ethnic groups enjoy political presence outside of their original settlements. For instance, in 2013, Hui served in six different provincial standing committees, Tibetans in four, and Mongols in three.

3.6 Career characteristics

The provincial standing committee is hierarchical, where the party secretary and governor are at the ministerial level and the rest are at the vice-ministerial level. The party secretary and governor are therefore always ranked as the top two. The rankings of the other members are largely determined by the importance of their responsibilities and seniority. The variable Seniority is measured as the number of years when one had served in the provincial standing committee with which one was currently affiliated. According to our data, one-third of the members were bureau-level officials before they entered the provincial standing committee, then promoted to the vice-ministerial level. Many members were already assigned a position at the vice-ministerial level before they entered the provincial standing committee. Their previous political careers were various: it could be a key position in a province, a central party institution, a central government department, a national bank, a big state-owned enterprise, etc. Previous political experience is measured with three variables. The first variable (Local Experience) is the number of years when one had been a provincial official at the vice-ministerial level or above.Footnote 5 The second variable (Non-local Experience) is the number of years when one had been a (vice-)ministerial-level official in the central government, a central CCP organization, or the economic sector. The third variable (Work Units) is the number of different work units where one had been a (vice-)ministerial-level official.

3.7 Local–central ties

Although central leaders try to suppress cliques formed among local officials, they tend to extend their own support networks by assigning key provincial positions to their loyal followers or by recruiting them into the Politburo (Zhang, Reference Zhang2014). Here, we use birthplace ties to measure ties between provincial officials and central leaders, in particular birthplace ties with Politburo Standing-Committee members of the 17th and 18th Central Committees. Local–central ties are not common social capital for provincial-standing-committee members: in 2013, 34% of them had a birthplace tie with the old central leaders (the 17th Politburo Standing CommitteeFootnote 6), and 24% with the new central leaders (the 18th Politburo Standing Committee).

4. Models and discussion

4.1 Deficits and rankings in the provincial standing committee

Ordered logistic regressions are used to test the two hypotheses regarding the enforcement of the law of avoidance where the dependent variable is the ranking of the provincial-standing-committee member (see Table 1). In models 1 and 3, all provincial-standing-committee members are included. For robustness check (Appendix 2), models 2 and 4 exclude provincial party secretaries and governors for analysis, who are at the ministerial level, one level above the other provincial-standing-committee members. All of these models control for provincial officials' basic demographic characteristics, work experience, and local–central ties.

Table 1. Ordered logistic regression analysis of rankings of provincial-standing-committee members

Data source: The Database of Chinese Officials maintained by www.ifeng.com.

Notes: Military officers in provincial standing committees are excluded. In models 1 and 3, all provincial-standing-committee members are included, whereas in models 2 and 4, provincial party secretaries and governors are excluded. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered by provinces. The estimates of the thresholds are omitted in the table.

The models presented in Table 1 provide strong evidence for the detrimental effect of birthplace ties on provincial officials' rankings and such an effect is enhanced with a higher provincial deficit. As Table 1 shows, the coefficient of birthplace ties among provincial officials, whether they are measured as a count or a binary variable, is positive and statistically significant, indicating that birthplace ties are positively correlated with rankings of provincial-standing-committee members, or negatively correlated with their political status. In this sense, birthplace ties among local officials are negative social capital with regard to their careers, imposing a barrier to the most significant posts in the provincial government (e.g., provincial party secretary and governor). This shows that the Chinese Communist regime still appreciates the ancient rulers' wisdom of the law of avoidance in balancing central and local authorities (Li, Reference Li and Joseph2010). This norm has created distinct promotion incentives for native and non-native officials, leading to bifurcated career paths: native officials are less motivated for getting promoted into top leadership and more willing to pursue a political career based in their hometowns (Gao, Reference Gao2017).

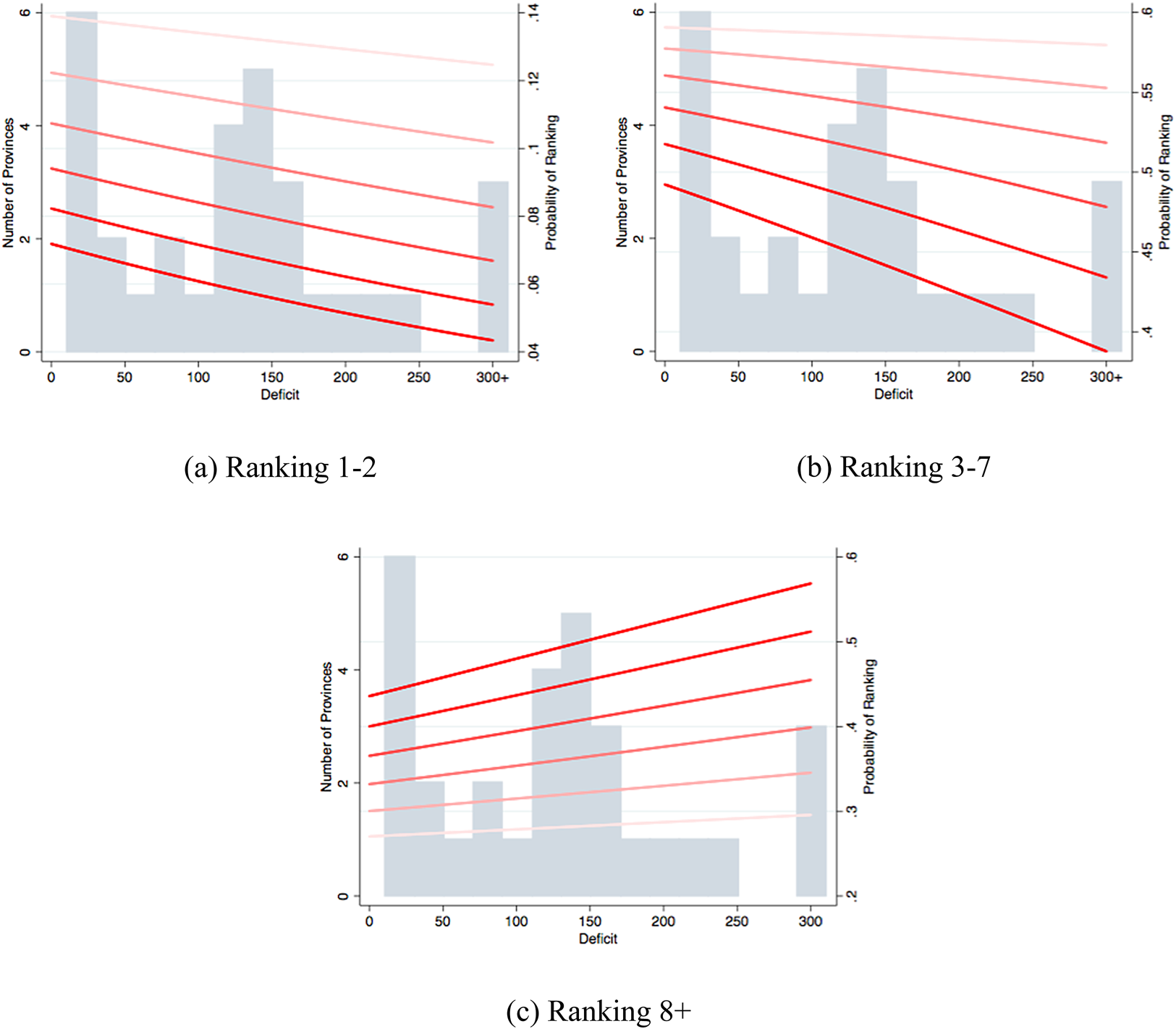

In model 1, the interaction term between deficits and birthplace ties is positive and statistically significant, suggesting that the effect of birthplace ties on rankings is also conditioned on the level of provincial deficits. In provinces with high deficits and urgent need of fiscal transfer from the central government, the barrier to top local leadership positions is further heightened for officials with extensive local connections. Based on model 1, Figure 1 visualizes such an interaction effect. Rankings of provincial-standing-committee members are first collapsed into three tiers: the ‘ranking 1/2’ category consists of all provincial party secretaries and governors; the ‘ranking 3–7’ category includes most important vice-ministerial-level officials, such as heads of provincial organization departments and secretaries of provincial disciplinary inspection commissions; and the ‘ranking 8 + ’ category subsumes the rest of provincial-standing-committee members, who take less important provincial leadership posts. In estimating the probability for each ranking category, binary predictors (gender and ethnicity) are set to their modes, and continuous and count predictors (age, career characteristics, and local–central ties) are set to their means.

Figure 1. Estimated effect of birthplace ties (count) on rankings of provincial-standing-committee members, varying deficit: (a) ranking 1-2, (b) ranking 3–7, and (c) ranking 8+. Notes: The graphs are based on the estimates of model 1 in Table 1. The histograms indicate the distribution of provincial deficits averaged over years from 2008 to 2013. The deficit over 300% is coded 300. The six lines from the lightest to the darkest represent the number of birthplace ties changing from 0 to 5. They show how the probability of certain rankings (1-2, 3–7, or 8+) varies as the deficit increases from 0 to 300%. In estimating the probability for each ranking category, binary variables (gender, ethnicity) are set to their modes, and continuous and count variables (age, career characteristics, local–central ties) are set to their means.

In Figure 1, the histogram in the background shows the distribution of deficits across 31 Chinese provincial-level administrative units. They are clustered into three groups: relatively solvent coastal provinces, mildly insolvent inland provinces, and heavily indebted provinces in ethnic minority settlements and Northeast China. The color of the six lines corresponds to the number of birthplace ties. The line is made darker as the number of birthplace ties increases from zero to five. Holding deficit at a fixed level, with more birthplace ties, the probability to fall into the ‘ranking 1/2’ tier or the ‘ranking 3–7’ tier drops, whereas the probability to fall into the ‘ranking 8 + ’ tier rises. For instance, based on the model, in a province free from deficits, a well-connected official with five birthplace ties is 7% less likely to be ranked top two than an isolated official without any birthplace ties, 10% less likely to be ranked between three and seven, and 17% more likely to be ranked eight or above.

In model 3, birthplace ties are measured as a binary variable, indicating whether the provincial-standing-committee member is native in the host province. The coefficient for birthplace ties in these two models is positive and statistically significant at the 95% confidence level, consistent with the findings from model 1 that the law of avoidance constrains the promotion prospects for locally connected officials. However, in model 3, the interaction terms of deficits and birthplace ties are not statistically significant, providing no evidence for the moderating effect of provincial deficits. Our empirical analysis sheds some light on how local economic resources affect power distribution between Chinese central and local authorities. It is shown that financial dependence weakens locally rooted political forces in provincial leadership and constrains the development of regional factions.

Our findings corroborate two recent empirical studies addressing the same research question, and further the understanding of how the law of avoidance is enforced by the party in its personnel management. Zeng (Reference Zeng2016) observed that the proportion of outsiders in provincial standing committees increased from 20% in 1992 to 40% in 2012. But, he also showed that the proportion is conditioned on economic performance that fewer outsiders serve as standing-committee members in provinces with high levels of GDP per capita and FDI per capita. Our research demonstrates that other than economic growth, fiscal deficits are also an important economic factor affecting the enforcement of the law of avoidance. Rather than examining whether the center avoids natives to govern important regions, we look at a different aspect of the law of avoidance, that is, whether the center avoids natives to take important local positions.

Complementing Zeng's investigation on Jiang's and Hu's administrations (Zeng, Reference Zeng2016), Bulman and Jaros focused on the administration under Xi who became the Chinese political leader in 2012 and has significantly centralized Chinese state power (Bulman and Jaros, Reference Bulman and Jaros2021). In the empirical analysis, Zeng (Reference Zeng2016) implicitly treated all provincial-standing-committee members as equals, we differentiate between them in terms of rankings, and Bulman and Jaros (Reference Bulman and Jaros2021) took a further step, examining various leadership roles individually. They observed that even in the Xi era, a large number of local officials retain their positions in provincial standing committees, but the most important roles – including party secretary, governor, organization department head, and disciplinary inspection chief – are subject to stronger central control. And they believed that such a complex strategy reflects different risk factors involved in different forms of localism (subnationalism, territorial cliques, and local protectionism).

Our regression models also control for demographic characteristics, work experience, and local–central ties of provincial officials. Age is statistically significant in models 1 and 3, including all provincial-standing-committee members, but not in models 2 and 4, excluding provincial party secretaries and governors. It appears that in allocating local leadership positions, age matters only for the levels of these positions (ministerial-level or vice-ministerial-level) – in general, provincial party secretaries and governors are older than their colleagues in provincial standing committees. For provincial officials at the same level, however, their responsibilities and rankings are not largely determined by their age. The other two demographic characteristics, gender and ethnicity, are not statistically significant, having no direct effect on rankings of provincial officials, holding all the other variables constant. This may be a result of the Communist Party's efforts to improve the descriptive representation of women and ethnic minorities. Nevertheless, they may be underrepresented indirectly as a result of their demographic attributes, for they may lack work experience that is valued for key local leadership posts.

Among the four work-experience variables, Seniority, the number of months that one had served in the provincial standing committee as of 2013, is negatively correlated with rankings across all of the models. This demonstrates that senior officials tend to receive more important positions of provincial leadership. Moreover, it is shown that previous local experience has no effect on rankings. It is also shown that previous non-local experience plays a role only for the promotion into the top tier, for the coefficient of this variable becomes statistically insignificant when provincial party secretaries and governors are excluded (models 2 and 4). Similarly, diversity of work experience (Work Units) appears to be a crucial selection criterion only for top-tier provincial standing-committee members, but not for their lower-tier colleagues.

Unlike birthplace ties between provincial officials, birthplace ties with central leaders, whether they are the 17th or the 18th Politburo-Standing-Committee members, have no significant effect on rankings of provincial officials. It seems that birthplace ties are weak ties and inadequate to generate strong trust between central leaders and provincial officials.

4.2 Deficits and Central-Committee membership

A multinominal logistic regression model is employed to investigate how provincial deficits affect provincial-standing-committee members' status in the Central Committee (see Table 2). The dependent variable, Membership, contains four categories – Central-Committee non-members, alternate members, full members, and Politburo members – with non-members as the baseline category.

Table 2. Multi-nominal logistic regression analysis of central-committee membership

Data source: The Database of Chinese Officials maintained by www.ifeng.com.

Notes: Military officers in provincial standing committees are excluded. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered by provinces. The baseline category indicates those who are outside the Central Committee.

As Table 2 shows, the coefficient of deficits is statistically significant only with regard to alternate Central-Committee membership. This finding indicates that in a province struggling to fill in its budget hole, its standing-committee members at the vice-ministerial level have a low chance to become part of the CCP central leadership. It also indicates that for the party secretary and governor in such a province, however, the prospect for securing full Central-Committee membership or Politburo membership is not affected.

Based on the multinomial logistic regression model, Figure 2 visualizes the substantive effects of deficits on Central-Committee membership. The histogram shows the distribution of provincial deficits averaged over the years from 2008 to 2012. The three lines illustrate the relationship between the level of deficits and the prospect for getting a seat in the Central Committee, with the dot line for alternate membership, the dash line for full membership, and the solid line for Politburo membership. As Figure 2 demonstrates, there is a strong negative correlation between deficits and alternate membership. For instance, as the level of deficits rises from zero to 300%, the probability of becoming an alternate Central-Committee member will decline from 0.19 to 0.15. Such a 4% decrease cannot be ignored, because the baseline probability is already low. In contrast, the other two lines are low and flat, showing that deficits have a weak, if not any, effect on full and Politburo Central-Committee membership.

Figure 2. Estimated effect of deficits on central-committee membership. Notes: The graphs are based on the estimates from the multinominal regression model in Table 2. The histograms indicate the distribution of provincial deficits averaged over years between 2008 and 2012. The deficit over 300% is coded 300. In estimating the probabilities on Central-Committee membership, the binary variables are set to their modes, and the continuous and count variables are set to their means.

These findings suggest that two logics are at work in Central-Committee membership selection. On the one hand, each province usually is allocated two secure full-member seats in the Central Committee, usually one for the provincial party secretary and the other for the governor,Footnote 7 regardless of local economic performance and independence, and this institutional arrangement is intended for representing various provincial interests in national decision-making (Li, Reference Li and Joseph2010). The same logic goes for Politburo membership. Although given its small size (usually 25 members) the Politburo does not allow equal provincial representation, its composition reflects regional balance. It is not difficult to forecast the provincial presence in the coming Politburo, very likely which will include the party secretaries of Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Chongqing, Guangdong, and Xinjiang. The first four administrative units are the municipalities directly controlled by the Chinese central government, with Beijing and Tianjin in North China, Shanghai in East China, and Chongqing in Southwest China. Guangdong is China's largest province in terms of population and GDP, located in South China. Xinjiang, in Northwest China, is of deep concern for Chinese political leaders because of tense ethnic conflicts. The logic of regional pluralism contradicts the previous finding that local economic performance, especially GDP growth, is a major consideration for the promotion of top provincial leaders (Li and Zhou, Reference Li and Zhou2005).

On the other hand, the logic of economic independence plays an important role with regard to fewer provincial leaders. Although the Central-Committee membership of provincial party secretaries and governors is immune to bad local economic conditions, a serious deficit greatly reduces the likelihood of securing an alternate-member seat for the other provincial-standing-committee members. The logic of economic independence and the logic of regional pluralism together ensure that a province with an increasing deficit will have less influence in national decision-making, but will not completely lose its voice.

To a certain extent, our findings are consistent with Li's observation of Central-Committee recruitment in the Jiang era (Li, Reference Li, Naughton and Yang2004). He observed two conflicting trends of elite selection: the rise of political localism and the consolidation of institutional restraints on local factions. A typical example of the first trend is the Shanghai gang, a group of high-ranking officials who originated from Shanghai and have close ties with Jiang. Another example is princelings, who are descendants of former central leaders and are usually based in Beijing. Meanwhile, various institutional measures were taken to control local factions. These measures include but are not limited to reshuffling provincial party secretaries and governors, shortening term lengths, enforcing the law of avoidance, and reserving two full-membership seats in the Central Committee for each province. It appears that although granting provincial governments considerable autonomy with their own personnel management, the central government keeps tight institutional control over crucial positions of provincial leadership, especially party secretaries, governors, organization department chiefs, and disciplinary inspection chiefs. As part of Xi's devoted anti-corruption efforts, the National Supervisory Commission and its local branches were established in 2018 as a centralized political institution supervising and disciplining government officials and party cadres. This institutional reform also centralized the personnel management of local disciplinary officials, with an increasing number of outsiders becoming provincial disciplinary inspection chiefs (Bulman and Jaros, Reference Bulman and Jaros2021).

Moreover, Table 2 demonstrates that demographic characteristics have mixed effects on Central-Committee membership. First, younger provincial officials are more likely to become an alternate member, but less likely to become a full member. Second, men have a higher chance of getting full membership than women, but such a gender bias ceases to exist with regard to alternate and Politburo membership. Third, in the Central Committee, ethnic minorities are over-represented as alternate members, equally represented as full members, but under-represented as Politburo members. In addition, work experience is also shown to have mixed effects on Central-Committee membership. Local experience matters for all ranks of membership. Non-local experience is important, but not for Politburo membership. And diverse work experience seems to be a necessary requirement for Politburo membership.

5. Conclusions

Economic autonomy is an important source of political power. As wealth is redistributed, power comes to a new equilibrium. Economic performance has been a major source of the Chinese government's political legitimacy (Wang, Reference Wang2005). When native officials are able to take advantage of their local knowledge and ties to achieve a high level of local economic performance, the center is likely to grant them more discretion over their local economic and political affairs. In contrast, when native officials lack abundant local resources and are heavily dependent on the central government for financial support, the center will tighten its control over the provincial government, in particular its personnel management. Our research examines the relationship between Chinese central and provincial governments after the 2008 economic crisis. With a sharp rise in provincial debts, provincial governments became more financially reliant on the central government. We find that highly insolvent provinces have weak bargaining power against the center. Compared to the outsiders transferred from the center or the other provinces, their native officials have a lower chance to take key local leadership positions. And further, these provinces have weaker influence in national decision-making processes, especially in terms of alternate Central-Committee membership.

With a closer look at the empirical results, economic performance is not the only logic for how power is allocated between the center and provinces and among provinces themselves. We find that balanced regional representation is an important principle with regard to provincial involvement in national decision-making. For instance, the Central Committee reserves two seats for the party secretary and governor of each province regardless of its economic independence. Such institutional arrangement allows national policy-making to reflect various interests of Chinese provinces, not just the concerns from the most developed provinces.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/CK4XM8.

Appendix 1. Summary statistics of the characteristics of provincial-standing-committee members

Appendix 2. Robustness of the findings on deficits and rankings

Since provincial party secretaries and governors may be subject to a different set of evaluation criteria from other provincial-standing-committee members, we conducted a robustness test by excluding provincial party secretaries and governors for regression analysis (models 2 and 4). As model 2 shows, the robustness test supports the interaction effect of deficits and birthplace ties on provincial-standing-committee rankings. In fact, the coefficient of birthplaces in model 2 (0.1720) is higher than the coefficient in model 1 (0.1397), and the coefficient of the interaction term is the same in these two models (0.0005). These findings suggest that the detrimental effect of birthplace ties on rankings is larger for vice-ministerial provincial officials than provincial party secretaries and governors, but the moderating effect of deficits is similar for them. The findings from model 4 are consistent with those from model 3: when birthplace ties are measured as a binary variable, birthplace ties do harm to one's ranking in the provincial standing committee, but the magnitude of this detrimental effect is not conditioned on provincial deficits.