1. Introduction

Congressional scholars have often explained elected representatives' behavior by referring to the incentives derived from electoral rules. Accordingly, changes in electoral rules are expected to result in changes in legislative behavior. This article discusses how changes to electoral rules affect legislative behaviors and whether the district and party-list legislators behave differently under a mixed-member system. There is an agreement about the consequences of electoral rules, such as the plurality rule in a single-member district (SMD) and proportional representation (PR). For instance, representatives elected under the SMD system tend to represent local interests, advance a personal reputation, and provide a constituency service in their districts (Mayhew, Reference Mayhew1974; Cain et al., Reference Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina1984; Reference Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina1987; Flanigan et al., Reference Flanigan, Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina1988). Legislators elected under the PR system tend to represent national interests, advance the party's reputation, and toe the party line in legislative voting (Fenno, Reference Fenno2003; Colomer, Reference Colomer2011). It is, consequently, assumed that SMDs with plurality rules and a list PR system should drive legislators to behave differently.

Scholars are still debating whether a mixed-member system provides a mandate-divide mechanism, and extant evidence remains inconclusive. There are three debating theories: ‘the best of both worlds (Shugart and Wattenberg, Reference Shugart and Wattenberg2001),’ ‘the worst of both worlds (Bawn and Thies, Reference Bawn and Thies2003),’ and the ‘contamination theory (Crisp, Reference Crisp2007).’ In principle, they differ regarding whether there is a mandate-divide between list PR and district representatives. The mandate-divide hypothesis expects district representatives to have high incentives to embrace constituents' preferences and their mandate to be defined by district voters. This view expects list PR legislators to be likely constrained by the party leadership to a much greater extent. However, there is no consensus on whether such a mandate-divide exists in the mixed-member system. I argue that most studies underestimated the strength of parties in parliament and the candidate selection, particularly in the parliamentary system, which may undermine the expected effect generated by the electoral system. It is why there is no conclusive finding on mandate-divide mechanism under the mixed-member system in extant literature.

Is there a mandate-divide between the district and list PR representatives in Taiwan? Does electoral reform affect party discipline? Most studies only consider the yea and nay votes in the analysis, but I argue that abstention and absence are potential sources of defection in some countries. I will analyze the defection behavior considering abstention and absence. This article shows that analysis of defection behavior considering abstention or absence can be an appropriate method in countries where party discipline is stringent. Besides, this article finds that mandate-divide exists in Taiwan: district legislators tended to defect from the party line than list PR members, but the motivation of defection has decreased after electoral reform. However, district legislators were more likely to be absent from voting than list PR members after electoral reform as they attempted to avoid position-expressing and spent more time in constituency service.

This article is organized as follows. First, I will discuss the extant literature regarding the related studies. Then, I will describe the electoral reform in Taiwan and present the hypotheses. Third, I will present the results of the defection rate using the roll-call vote. Meanwhile, I will complement with discussing interviews I conducted. Finally, I will conclude and provide suggestions for future studies.

2. Mandate-divide under mixed-member system

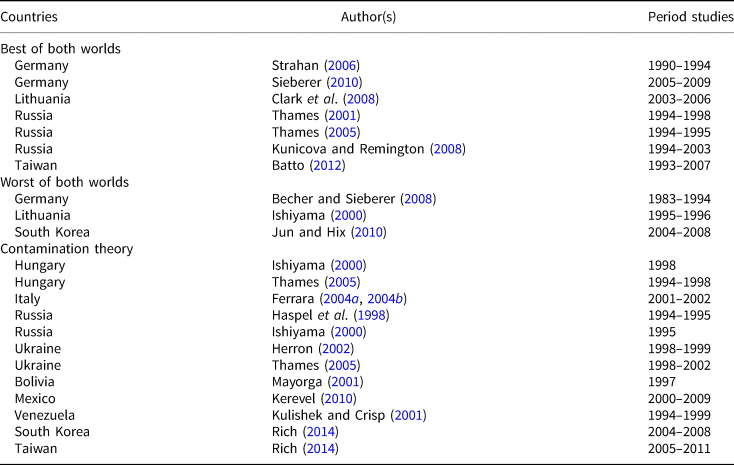

Mixed-member systems offer a quasi-experimental setting in which we can simultaneously observe the behavior of representatives elected under different rules (Stratmann and Baur, Reference Stratmann and Baur2002; Moser and Scheiner, Reference Moser and Scheiner2005). The idea that the different tiers of representatives are linked to different principles underlines the logic of the ‘mandate-divide’ perspective (Thames, Reference Thames2005). District representatives are agents of voters and have many incentives to be responsive to the needs of local constituents. By contrast, list PR members are the agents of parties. They tend to defend their parties' positions and policies and focus on national interests (Shugart and Wattenberg, Reference Shugart and Wattenberg2001; Bawn and Thies, Reference Bawn and Thies2003; Ferrara et al., Reference Ferrara, Herron and Nishikawa2005; Thames, Reference Thames2005; Kerevel, Reference Kerevel2010; Sieberer, Reference Sieberer2010). However, there are no conclusive findings in mandate-divide, and three different perspectives are still debating (see the summarized instances in Table 1).

Table 1. Empirical tests of the mandate-divide hypothesis on party unity in previous studies

The ‘best of both worlds’ perspective hinges on assuming that a mixed electoral system's tiers operate independently (Shugart and Wattenberg, Reference Shugart and Wattenberg2001). It fits the nation of a mandate-divide. According to this view, a mixed-member system encourages cohesive national parties through the PR tier and local responsiveness through the SMD tier. It makes local interests relevant to legislators while still promoting solid national parties accountable to the constituents (Shugart and Wattenberg, Reference Shugart and Wattenberg2001). Consequently, legislators elected under the SMDs should have a propensity to represent local interests, be more likely to challenge party leadership when there is a conflict between local and national interests, and be more active in promoting parochial bills. On the contrary, legislators elected under the PR system are expected to represent national interests, engage in legislative activities that benefit the party's reputation, and behave uniformly in roll-call votes.

The ‘worst of both worlds’ perspective notes that candidates usually represent two types of interests: organized (interest groups) and unorganized ones (individual voters) (Bawn and Thies, Reference Bawn and Thies2003). It also draws attention to the fact that most mixed-member systems allow dual candidacies (i.e., the possibility that a legislator runs in both tiers in the same election). It means that a nominal tier candidate can be rewarded with a safe seat in the party-list in case their candidacy in the former is unsuccessful (Ferrara, Reference Ferrara2004a). In other words, candidates losing in the local district can still have the chance to be elected as party-list members (Reed and Thies, Reference Reed, Thies, Shugart and Wattenberg2001; Pekkanen et al., Reference Pekkanen, Nyblade and Krauss2006). According to Klingemann and Wessels (Reference Klingemann, Wessels, Shugart and Wattenberg2001), these ‘double included’ legislators attempt to balance their roles as local representatives and party agents, but not everyone agrees that this is the norm. If there is an absence of independence, we cannot expect nominal tier candidates to behave as legislators elected in an SMD-plurality system, nor can we expect list-tier members to behave as legislators elected in a closed-list PR system (Crisp, Reference Crisp2007). Because Taiwan has no design of dual-candidacy, this hypothesis cannot be tested in the case of Taiwan.

The ‘contamination theory’ views mixed-member systems as a distinct type of electoral system, not just a mere combination of plurality and PR systems. The central point is that ‘the existence of one tier prevents legislators from the other tier from behaving as if they were elected in a “pure” system made up of their tier alone’ (Crisp, Reference Crisp2007). According to this view, mixed-member systems operate differently from the corresponding pure systems because voters do not make independent decisions when voting on each tier. Parties may adopt similar campaign strategies despite competing in two different tiers. Therefore, the legislators elected in different tiers may behave similarly (Cox and Schoppa, Reference Cox and Schoppa2002; Ferrara et al., Reference Ferrara, Herron and Nishikawa2005; Crisp, Reference Crisp2007). One source of potential contamination is the party, which may constrain the behavior of its members. For instance, Stratmann and Baur (Reference Stratmann and Baur2002) found the mandate-divide between German legislators elected under plurality rule and those elected under list PR did not manifest in roll-call votes because voting decisions in parliament were made along party lines. In other words, party discipline can prevent potential differences between tiers from emerging in roll-call votes. This may result from institutional mechanisms that foster party unity in parliamentary systems (e.g., the vote of confidence) or the centralized candidate selection method (CSM).

3. Case selection

Why should we focus on the case of Taiwan? Most countries using a mixed-member system reformed from ‘pure’ plurality rule or PR system. They just added an additional tier in their original system. Taiwan is one of the countries (Japan and South Korea) that reformed its electoral system from the single non-transferable vote (SNTV) in multi-member districts (MMDs) to the mixed-member majoritarian (MMM) system (or parallel system). Taiwan completed electoral reform through a constitutional amendment in 2005. The classic SNTV takes place in one tier only. One unique trait Taiwan had was that it had introduced another party-list tier jointly with the SNTV tier before moving to the MMM system. Such a system might be viewed as a subtype of a mixed-member system (Batto, Reference Batto2012), but it was slightly different from the classic mixed-member system, where voters cast two separate votes for each tier.

By contrast, voters in Taiwan only had one ballot that was cast in the lower SNTV tier. The allocation of party-list seats (list tier) was determined by the vote share in the local district election (nominal tier), with a 5% threshold (Wang, Reference Wang1996). After electoral reform, Taiwan adopted the MMM system. Voters have two ballots for the district candidate and the party they prefer separately. The nominal tier is elected in an SMD, and allocation of the list-tier is determined by the vote share that each party gained with a 5% threshold. Thus, Taiwan is a perfect case to see the effect of electoral reform on legislative behavior and compare the mandate-divide mechanism under the SNTV and MMM system. In this article, mandate-divide indicates the different electoral mandates for list PR members and district members elected in SNTV or SMD.

4. Electoral reform and role of parties

Electoral reform was one of the reforms in the constitutional amendment of 2005. The amendment also abolished National Assembly and transferred its rights to the Legislative Yuan. Such executive–legislative reform gave legislators more power with the rights of impeachment, alteration of the national territory, and amendment of the constitution. Taiwan is a semi-presidential system, so legislators should have more autonomy than members in a parliamentary system. However, I do not think such reform would affect party discipline because these rights require a very high threshold to exert.Footnote 1 Without the party leadership, legislators cannot achieve their goals with these rights. By contrast, the passage of roll-call vote only requires simple plurality. Any dissident may lead to the opposite outcome of the voting. Thus, I argue that executive–legislative reform should have a minimal effect on legislative behavior.

Electoral reform should change the relations among politicians, constituents, and the party, and I will elaborate on my argument below. Different electoral systems have a distinct effect expected by the institutional designer. SNTV is a highly candidate-centered electoral system. The most important feature of the SNTV is that elections are held in MMDs, and candidates are selected using a simple plurality rule. The electoral threshold is usually low due to multiple seats and aspirants in a district (Cox and Rosenbluth, Reference Cox and Rosenbluth1993; Cox, Reference Cox1997). The big parties have the incentive to nominate multiple candidates. Thus, big parties face significant challenges in determining the potential distribution of votes among their candidates. Big parties have to nominate an appropriate number of candidates to avoid wasting votes on winning or trailing candidates (Cox and Rosenbluth, Reference Cox and Rosenbluth1993; Cox and Niou, Reference Cox and Niou1994; Cox and Thies, Reference Cox and Thies1998; Bergman et al., Reference Bergman, Shugart and Watt2013). Besides, big parties aim to maximize their seats, and they need to manage vote equalization to prevent losing a winnable seat (Bergman et al., Reference Bergman, Shugart and Watt2013; Yu et al., Reference Yu, Shoji, Batto, Batto, Huang, Tan and Cox2016). By contrast, the small parties face little difficulty in the nomination and can gain an electoral bonus in MMD when the district magnitude (DM) is larger (Taagepera and Shugart, Reference Taagepera and Shugart1989).

With the salient presence of intraparty competition, SNTV enhances candidates' incentives to cultivate a personal vote (Nemoto et al., Reference Nemoto, Pekkanen and Krauss2014), and the value of the personal vote grows as a district's magnitude increases (Carey and Shugart, Reference Carey and Shugart1995; Shugart et al., Reference Shugart, Valdini and Suominen2005). Thus, legislators are more likely to defect from the party because they still have the chance to be elected even if running as an independent or representing another party label under MMD. Due to a lower electoral threshold under MMD, candidates are incentivized to articulate radical language, take extreme policy stances, use vote-buying strategies, and target specific groups of constituents with particularistic proposals and pork-barrel projects to appeal the support of particular constituents (Cox, Reference Cox1990; Myerson, Reference Myerson1993; Cox and Thies, Reference Cox and Thies1998; Stockton, Reference Stockton2010; Chi, Reference Chi2014).

The electoral reform changed the relations between candidates and parties. First, parties have to select only one candidate in SMD carefully. The intraparty competition disappears in the election, and SMD leads to a two-party battle. Although electoral reform reduces fragmentation in parliament, it increases the disproportionality between the vote and seat (Wu, Reference Wu2008; Stockton, Reference Stockton2010). Thus, the small parties have little chance of winning a plurality election under SMDs and can only strive to surpass a high 5% threshold to gain the seats in the list-tier. Second, candidates without the endorsement of the party will find it challenging to win the seat under the SMD because the SMD is electorally favorable for the big parties (Wu, Reference Wu2008; Stockton, Reference Stockton2010). Party leaders can impose party discipline on party members. Once the legislator is expelled by the party or membership is suspended, his or her reelection will be interrupted. They need to maintain their membership by trading with their loyalty.

The electoral reform also changed the relations between politicians and constituents. First, the plurality rule in SMDs enhances the accountability linkage between the representative and the constituent (Lancaster, Reference Lancaster1986; Scholl, Reference Scholl1986; Norris, Reference Norris2004). It is easier for voters to identify whom to reward or punish in SMDs than in MMDs (Lancaster, Reference Lancaster1986; Lancaster and Patterson, Reference Lancaster and Patterson1990; Norris, Reference Norris2004). Legislators are therefore likely to devote themselves to activities that benefit their political reputation. Second, politicians elected under SMD are concerned more with localness: bringing pork-barrel projects back to the constituency, claiming credit for legislative achievements, involving themselves in district activities, and providing a variety of constituency services (Mayhew, Reference Mayhew1974; Cain et al., Reference Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina1984; Reference Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina1987; Flanigan et al., Reference Flanigan, Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina1988; Carey and Shugart, Reference Carey and Shugart1995; Fenno, Reference Fenno2003). Third, unlike SNTV candidates, candidates competing in SMDs are incentivized to adopt centrist positions. When two candidates compete in SMDs, they tend to converge to the median voter's position (Downs, Reference Downs1957). Candidates will seek positions that enjoy majority support rather than niche positions that appeal only to a small share of the electorate (as with SNTV).

As for the list-tier, Taiwan adopted a closed-list PR system. Before the electoral reform, voters had only one vote to elect candidates in both tiers. The fate of candidates in these linked-PR seats depended on the performance of party candidates in local districts elected under SNTV. That is, list PR candidates did better electorally when their SNTV partners did better. After electoral reform, voters can vote for the party they prefer, which increases the importance of party labels. It also increases the incentives for parties to advance national policy programs they will promote after the election on the electoral manifesto. Parties are also incentivized to nominate reputable persons at the top of the list. This may have affected the electoral incentives of list PR candidates differently compared to the post-reform period when two separate votes severed the electoral linkage between tiers.

Apart from the electoral system, the CSMs also change among parties in Taiwan. Norris (Reference Norris1997) showed that electoral institutions substantially impact CSMs, particularly differences in DM and ballot structure. Under the plurality rule in SMDs, parties should be especially concerned about selecting a candidate capable of appealing to most of the electorate in the district. By contrast, MMDs allow for a more balanced roster. Different CSMs have distinct effects on legislators. When the party controls the nomination of candidates and campaign funds, party leaders can induce Members of Parliament (MPs) to behave in the pattern fitting the party's best interest (Reed and Thies, Reference Reed, Thies, Shugart and Wattenberg2001). For instance, parties may push candidates in SMDs to undertake party-centered campaigns (Crisp, Reference Crisp2007). Crisp et al. (Reference Crisp, Escobar-Lemmon, Jones, Jones and Taylor-Robinson2004) found that MPs chosen under centralized CSM were less likely to initiate legislation targeting constituencies and more likely to focus on national interests.

The parties in Taiwan have evolved distinct CSMs in different periods. Due to the limited length of the article, I could not describe in detail but summarize the evolution of CSMs among parties in online Appendices A and B. In brief, Taiwanese parties had more diverse CSMs on nominal tiers before electoral reform. The small parties tended to control the nomination, but the big parties (Kuomintang, KMT, and Democratic Progressive Party, DPP) adopted different rules in selecting their candidates. They had different rules components in selecting the nominal tier candidates, such as party member voting, opinion poll, and party cadres voting. As for the list tier, the KMT tended to control the nomination of the list tier, but the DPP combined different rules as they had on the nominal tier. After electoral reform, both big parties converged their CSMs: they used the 100% opinion poll to select their nominal tier candidates but controlled the nomination of list tier candidates. Compared to the period prior to the electoral reform, party leaders lost influence over SMD candidates but gained more influence over list PR candidates. However, it does not mean the party is not important in the SMD election. Party labels become more critical in the elections. When the ruling party performs well, it benefits its candidates elected in SMDs, particularly in battlefield districts.

5. Hypotheses

Comparative evidence of party unity under a mixed-member system remains inconclusive, but the differing mandates hypothesis has been tested in many countries (see Table 1). According to conventional explanations along the lines of the ‘best of both worlds’ theory, legislators elected under SNTV should have been more likely to defect from the party line than party-list legislators. Moreover, the electoral rules literature would go a step further and argue that intraparty competition within SNTV legislators should have been more intense when DM was high (Carey and Shugart, Reference Carey and Shugart1995). Therefore, there is a high likelihood that defection rates would have been greater among SNTV legislators elected in high-magnitude districts. Properly evaluating party unity prior to the electoral reform demands that we pay attention to the three types of legislators elected during the pre-reform period: SNTV legislators running where DM was low, SNTV legislators running where DM was high, and list PR legislators.

The ‘best of both worlds’ theory would also expect list PR legislators elected after the reform to be more disciplined than their counterparts elected in SMDs. For legislators elected via closed-list PR after the reform, party reputation is paramount. These MPs are primarily interested in promoting a positive image of the party (Stratmann and Baur, Reference Stratmann and Baur2002). Under closed-list PR, voters are more likely to be influenced by the party's positions than by legislators' individual characteristics (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Saiegh, Spiller and Tommasi2002). As several scholars have noted, legislators elected under closed-list PR are less likely to deviate from the party line than legislators elected under SMDs, who have more to gain electorally from occasional deviations from the party line to accommodate district concerns (Sieberer, Reference Sieberer2010; Batto, Reference Batto2012). Moreover, public opinion polls influenced the nomination of SMD candidates, while the goodwill of party leaders was more likely to determine the nomination of list PR candidates. Party leaders had the tools to prevent dissidents from running in party lists. When party leaders control nominations, as in the UK, MPs have been much more inclined to collaborate promoting the party's reputation than when party leaders play a less prominent role in nominations, as is the case in the USA (Cox, Reference Cox1987).

However, the ‘contamination’ theory cast some doubts on these expectations. First, list PR candidates before the reform were not elected independently; their fate was linked to the performance of SNTV candidates. This altered the incentives of both list PR and SNTV candidates, who knew that their electoral chances were not independent. Second, party leaders in parliament could still play a relevant role by expelling or giving fines to dissident legislators, which lowered incentives to defect among legislators elected in SNTV (before the reform) and SMDs (after the reform).

One significant change in the election reform has been the greater importance of parties after introducing the MMM system. In Taiwan, changing electoral rules from SNTV to MMM increased the importance of political parties. The end of intraparty competition at the district level and the direct election of party-list candidates strengthened the importance of party labels. Legislators' incentives to defend the party increased, and the value of personal vs party reputation decreased. The party's relative importance to SMD candidates is greater than under SNTV, so party discipline under the SNVT is likely lower than under SMDs, particularly for legislators elected under SNTV in larger DM.

To sum up, this discussion leads to a series of alternative hypotheses about party unity before and after the electoral reform. Hypotheses 1 and 2 reflect the conventional expectation from the ‘best of both worlds’ perspective.

H1: Before the reform, party unity should be higher among legislators elected under the PR than among legislators elected under SNTV.

H2: After the reform, party unity should be higher among legislators elected under PR than among legislators elected under plurality in SMDs.

The null hypothesis of no difference in unity between legislators elected under the two different tiers would be consistent with the contamination hypothesis. The following hypothesis focuses on roll-call votes and refers to changes before and after the electoral reform.

H3: Overall levels of party discipline should be higher after the electoral reform (under the MMM system) than before it (under the SNTV system).

The final hypothesis in this section refers to CSMs. As summarized in online Appendices A and B, I classified different CSMs into inclusive (decentralized) and exclusive (centralized) CSMs. Exclusive CSMs are a method whereby party leaders completely control the nomination, and inclusive CSM is the method open for a vote cast by the party members or method adopting poll survey. I expect to see that inclusive CSM should drive the candidates to resort to the support of party members or general voters. They should, therefore, have incentives to represent the interests of the electorate. Consequently, they are expected to be more likely to deflect from the party line and advance particularistic interests.

H4: Party unity should be higher among legislators elected with exclusive CSM than legislators elected with inclusive CSM.

6. Variables and operationalization

This section describes how I operationalized independent variables and control variables. Aside from the quantitative method, I also interviewed legislators and their legislative assistants. I quoted the content of these interviews in the empirical analysis.

6.1 Independent and control variables

The independent variable in this article is the electoral tier. This dummy variable captures the legislator elected with different electoral rules: district MPs (elected with SNTV-MMD or SMD-plurality), PR list MPs, and indigenous MPs (elected with SNTV-MMD). Besides, legislators' incentives to cultivate a personal vote are greater in SNTV when DM is higher (Carey and Shugart, Reference Carey and Shugart1995). Thus, DM matters in SNTV. I classify SNTV legislators into lower and higher DM. The mean of DM is 7 in the pre-reform period. If SNTV legislators were elected in DM ≦7, they were classified as lower DM. If SNTV legislators were elected in DM ≧8, they were classified as higher DM.Footnote 2

I also included several control variables in the analysis. The first is the inclusivity of (de)centralization in the CSMs, which was operationalized as a dummy variable. Based on the description of CSMs in online Appendices A and B, this categorical variable ranges from very decentralized to very centralized. A binary variable – inclusive and exclusive CSMs were used for simplified analyses.Footnote 3

The other control variables are political variables. First, I expected party affiliation and members of the majority and the opposition party to behave differently. In the pre-reform period, there were five parties in parliament: KMT, DPP, People First Party (PFP), Taiwan Solidarity Union (TSU), and Non-Partisan Solidarity Union (NPSU) (only present in the sixth term). After the reform, the KMT and DPP dominated in parliament. Because NPSU is not a classic party, it was excluded from the analysis of the roll-call vote.Footnote 4 I created party dummies in the regression models. In addition, whether the party was ruling or the opposition party should influence party members' behaviors. For instance, ruling party members might devote much time to constituency service, while opposition party members might participate more actively in legislative activities (Sheng, Reference Sheng2008; Wang, Reference Wang2009). Second, the committee chair should possess more power and resources than general legislators (Sheng, Reference Sheng2014). I measured how many times legislators chaired a committee because a committee chair is selected each session. Third, seniority might also matter. Senior legislators and freshmen legislators should behave differently. For instance, senior legislators are less likely to defect from the party (Nemoto et al., Reference Nemoto, Krauss and Pekkanen2008). I counted how many terms they have served in the parliament to measure the seniority. Fourth, I controlled for two other variables related to localism. The first one was whether the legislator had a local faction background, using an updated adaptation of Lin's (Reference Lin2013) data. The other was whether the legislator had experience in local politics. For instance, legislators previously served as a representative in the local city or county council, heads of the village, city mayor, county magistrate, etc. Both were operationalized as dummy variables.

The final control variables are demographic one: gender and level of education. Many studies have found distinct differences between male and female politicians in terms of their behaviors and the issues of importance (see Lawless, Reference Lawless2015). Legislators who have education in particular professional fields should also focus on such issues to build their own legislative professionalism (Huang, Reference Huang2017). They may also be more concerned with national interest instead of particularistic interest. I recoded the educational level into three categories: high school and below, undergraduate, and graduate levels.

6.2 Conduction of interviews

This article also explored how Taiwanese legislators perceived the electoral rules. André et al. (Reference André, Depauw and Martin2016) argued that legislators do not always perceive electoral incentives similar to what scholars argue. Each country's unique political culture, party rules, legislative rules, or levels of party institutionalization may alleviate the effect of the electoral system and affect how legislators behave. However, most literature ignored the importance of legislators' perceptions of electoral rule. To fill this gap, I interviewed 15 legislators and congressional assistants to understand how they perceive Taiwan's electoral reform.Footnote 5 Although I interviewed legislators elected in the ninth term (2012–2015), the interviews could still provide valuable insights because 11 of 15 interviewees have experiences in pre- and post-reform periods. Due to limited space, the procedure for the interviews and backgrounds of interviewees are described in online Appendix C.

7. Data, methods, and analysis

A roll-call vote occurs when each legislator votes yea or nay as their names are called by the clerk, who records the votes on a tally sheet. According to articles 34, 39, and 44-1 of the Law Governing the Legislative Yuan's Power, a roll-call vote is required to override a veto, decide on a vote of no confidence, and for a motion to recall the president. Roll-call votes are regularly used for other motions in Taiwan and can be requested by 15 legislators or political parties.

I examined roll-call votes taken from the fifth to eighth Legislative Yuan, covering two terms pre-reform and two terms post-reform. The roll-call vote dataset was compiled and provided by the Center for Legislative Study, Department of Political Science at Soochow University in Taiwan.Footnote 6 The dataset includes votes on bills (policy) and legislative procedures, such as motions of reconsideration and motions of expediting a bill directly to the Second Reading. As presented in the next subsection, due to a very low rate of voting against, I analyzed all the roll-call votes without distinguishing different vote types.

As to the research method, some scholars use the approach of legislator × vote for analyzing whether legislators voted against their parties on certain roll-call votes with the logit model. However, I argue this approach generates a large sample size to make statistics more likely to be significant. The evidence is that the control variables are always statistically significant as well.

Focusing on the pre-reform period in Taiwan, Batto (Reference Batto2012) argued that some legislators might be more likely to defect on certain policies and use the multi-level logit model to analyze the roll-call votes. I agree that some legislators are more interested in some policies and are more likely to defect from the party on certain policies. However, in addition to different policies, there are many potential reasons to explain why legislators choose to defect from the party. For instance, whether a policy is important varies among legislators. When a bill is regarding the benefits of one's constituency, the legislator will value it. A legislator may defect because a certain policy violates their value or ideal. The bills promoted by the government are also important, and the party whip should push ruling party members to defend them. Such bills should incur more inter-party confrontations and party cohesion among ruling party members. Therefore, to identify important bills, I excluded unanimous roll calls from the analyses because they should be less important.Footnote 7 Besides, I considered only those votes where at least one-third of party members cast votes and at least one-half of those voted either yea or nay. When there is a low attendance rate among party members, such roll-call vote should be less important.

In this article, the unit of analysis is the individual legislator, and the legislator's aggregated defection rate is the dependent variable. I adopted this approach based on several reasons. First, many legislators quit their jobs due to many reasons (such as bribery, crime, death, or serving as a minister) during their tenure, and new members filled the vacancies through by-election or substitution on the party list.Footnote 8 To include these cases, I count the proportion of votes in which a legislator defected from the party line while in tenure. Otherwise, such cases will be eliminated from the analysis. But, I considered only party-affiliated legislators who cast more than 10 votes during their tenure. This approach eliminates a few legislators who had a short voting record due to the aforementioned reasons. Besides, the Speaker and Vice Speaker are also excluded from this analysis because they only vote to break the tie and have a short voting record.

Second, counting the defection rate by year may be a good approach to see the trends of defection. However, it usually takes a long time for MPs to review a bill. Most bills are reviewed and passed in the middle tenure. Legislators usually reviewed relatively fewer bills in the initial and last years of tenure.Footnote 9 The ruling party might also attempt to pass relatively controversial policies in the middle tenure to decrease the impact on the next election. Thus, considering the characters of different tenure stages, analyzing the legislator's aggregated defection rate is a better approach to examine the effect of electoral reform.

7.1 Analysis of defection rate

In addition to outright voting against one's party, I considered abstentions and absences as potential defections. The most challenging issue is whether we should treat absences as defection. Some scholars treated absences simply as missed votes, and some treated them as defections. On the one hand, some scholars speculated that legislators' absences are strategic. Specifically, they missed a session because they did not want to vote with or against the party. For instance, Herron (Reference Herron2002) considered absences, regardless of the underlying cause, to be defections. Ferrara (Reference Ferrara2004a, Reference Ferrara2004b) counted absences as defections unless the legislator's absence is due to attending to party activities or other official business. Thus, it is not easy to distinguish normal absences from strategic absences.

On the other hand, some scholars doubted that absence was a proxy for defection and thus did not treat them as such. However, in some instances, when a researcher found the defection rate (without counting absences) and absence rate to be highly related, then there may be a case to be made for incorporating the latter into the analysis as a form of defection (Sieberer, Reference Sieberer2010).

In the Taiwanese political context, anecdotal evidence suggested that both arguments had some merit (Batto, Reference Batto2012). First, party leaders often complained about how difficult it is to mobilize party members to attend floor meetings; this is especially true of district legislators because they are often busy in constituent activities. In many such instances, legislators would vote the party line if they could be motivated to attend the session. However, there were also stories about legislators taking overseas trips at precisely the time when controversial votes were scheduled. It was thus likely that some absences were quasi-defections.

When the ruling party enjoys a majority, party leaders may tolerate an absence. According to Rich (Reference Rich2014), with the KMT's overwhelming majority of seats (71.7%) in the 2008 congressional election, the party established informal rules with its party members: legislators alternated committee and roll-call vote attendance, swapping attendance commitments to avoid voting on issues when the party position is not consistent with legislators' constituent or personal preference. Absence may indicate a sign of party weakness if parties encourage this behavior. However, party-sanctioned absences were much preferred to abstaining or voting against the party, as both are more explicit signs of party splits. In South Korea, absences are also preferred to abstention and voting against one's party as a means to show displeasure (Rich, Reference Rich2014). Thus, when legislators perceive a strong signal of opposition from constituents, they might choose absence to skirt a controversial issue and avoid both criticism from constituents and the party's punishment. On some occasions, district legislators might need to participate often in local activities, and thus they tend to absent themselves from votes more often than list PR members.

In light of these considerations, I operationalized defections in three ways. First, a yea or nay vote in opposition to the majority of a legislator's party is considered a defection (type 1). Second, a yea, nay, or abstention vote in opposition to the majority of a legislator's party is considered a defection (type 2). Third, a yea, nay, or abstention vote in opposition to the majority of a legislator's party or an absence is considered a defection (type 3).

Table 2 summarizes statistics for defection rates for KMT and DPP. In addition, I presented separate results for the district and list PR legislators. As shown in Table 2, type 1 defection rates were pretty low no matter in the pre- or post-reform periods. The type 2 defection rate was only slightly larger than the type I defection. I found that district legislators usually had a little higher type I and II defection rates than list PR members, but not statistically significant. However, when focusing on type 3 defection (i.e., with absences counted as defection), district legislators had a much higher level of type 3 defection rates than list PR members, particularly for the KMT legislators. After the electoral reform, type 1 and 2 defection rates decreased. For both major parties, type 1 and 2 defection rates did not seem to differ much between the district and list PR legislators. However, absences increased a lot after electoral reform. But, district legislators had a statistically significantly higher type 3 defection rate than list PR members.

Table 2. Distribution of defection rate by party (%)

Then, I used ordinary least-squares (OLS) models to examine individual defection rates. The correlation between type 1 and 2 defection rates was 0.88. However, the correlation between type 3 and the other two defection rates was only 0.15. This suggests that the measure including absences as defection is picking up different legislative behavior. In the rest of this section, I used type 2 defection rates as the dependent variable and then complemented this analysis by looking at absence rate only (not type 3 defection) separately.

Table 3 presents the result of the type 2 defection rate. Model 1 focuses on the pre-reform period, model 2 focuses on the post-reform period, and model 3 uses data of all periods. I did not include all the control variables mentioned above in all the models. First, I controlled only for CSMs in the pre-reform period because CSMs are collinear with the electoral tiers in the post-reform period. After electoral reform, the main parties adopted inclusive CSMs for nominating local district legislators and adopted exclusive CSMs for nominating list PR members. Besides, model 3 additionally controls for ruling party members because there was only one ruling party and no coalition government in the pre-reform or post-reform period.Footnote 10 There is no need to control the ruling party in the pre-reform (model 1) or post-reform period (model 2) because it has collinearity with the parties in models 1 and 2.

Table 3. OLS model of defection rate: voting against and abstention (type 2)

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses.

***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05, *P < 0.1.

Overall, the results lent support to hypotheses 1, 2, and 3. Model 1 shows that SNTV legislators elected under large DMs tended to have a defection rate that was 0.5% higher than those of list PR legislators. However, there was no statistically significant difference in defection rate between legislators elected by SNTV in the districts with smaller DM and legislators elected in the fused-PR lists. Hypothesis 1 is thus not fully supported. Model 2 shows that SMD legislators had a higher defection rate in comparison with list PR legislators. This outcome is consistent with hypothesis 2, which predicts greater unity from the latter group of legislators. Model 2 shows that SMD legislators had a higher defection rate than list PR legislators. This outcome is consistent with hypothesis 2, which predicts greater unity from the latter group of legislators. The difference, however, was tiny: 0.1%. Besides, indigenous legislators are also expected to defect from the party line, particularly after reform, because they represent their indigenous interest.

However, I failed to find that CSM affected the defection rate. Hypothesis 4 is not supported. Model 3, which includes all periods, confirms previous results. I discovered that legislators elected in local districts (SNTV before the reform and plurality in SMDs after the reform) exhibited a higher defection rate than list PR legislators. Indigenous legislators also exhibited a higher defection rate than list PR members. There was no statistically significant difference between list PR legislators before and after the reform.

I also found there were statistical differences among congressional periods. First, legislators in the sixth term were less likely to defect from the party line than legislators in the fifth term. The level of party unity might be increasingly rising before the electoral reform. I argue legislators in the sixth term might already be affected by the electoral reform. Legislators might need to present their loyalty to their parties after they had realized the total seat of legislators would be downsized in half. Demonstrating loyalty might help their primary campaign for the seventh congressional election. Even if failing in the primary, demonstrating loyalty could also help them to be nominated by the party (on the party list). Sheng (Reference Sheng2008) provided another potential reason. According to the interviewers, when DPP president Shui-bian Chen was trapped in a corruption scandal and the ‘Depose-Bian Movement,’ the DPP legislators realized that they had to be united, particularly when DPP was a minority ruling party because they were in the same boat with President Chen. Otherwise, they would be defeated by the opposition parties.

Second, I found that the legislators in the post-reform period (both the seventh and eighth terms) were less likely to defect from the party line than legislators in the fifth term. I further analyzed the marginal effect, compared the pre-reform and post-reform periods, and found that the legislators' defection rate in the post-reform period was statistically significantly different from that of the legislators in the pre-reform period (F = 4.21, P-value = 0.041). The results lent support to hypothesis 3, which predicts higher overall levels of unity after the electoral reform.

Moreover, within the post-reform period, I found the defection rate in the eighth term was statistically higher than one in the seventh term. KMT was the ruling party then, and it enjoyed the majority seats in parliament. However, KMT President Ying-jeou Ma was suffering from a lower presidential approval. The KMT district legislators might, thus, be worried that the dissatisfactory performance of the ruling party would encumber their reelection so that they abstained from expressing their positions on some controversial issues. The occasion that KMT legislators faced was not similar to the DPP members in the sixth term. On the one hand, the DPP was shadowed by the corruption scandal, but KMT was not. On the other, the DPP was a minority ruling party then, but the KMT was a majority ruling party. Minority ruling party members should have a strong incentive to be united. Otherwise, the government will fail to rule. Sheng's (Reference Sheng2008) explanation is only specific to the occasion of the sixth term and cannot be applied to KMT legislators during Ma's presidency in the eighth term. Besides, as presented in Table 2, both KMT and DPP had a higher abstention rate in the eighth term than in the seventh term, so there should be some controversial issues that both KMT and DPP had no intraparty consensus.

7.2 Analysis of absence rate

Table 4 presents regression models where the dependent variable is the proportion of absences (absence rate). Model 4, which evaluates data for the pre-reform era, shows no statistically significant difference between tiers. CSM also had no effect in explaining the absence rate in the pre-reform period. Model 5, however, shows that SMD legislators missed votes somewhat more often than list PR legislators. Model 6 confirms the findings of the previous two models. SMD legislators were absent more frequently than list PR members after electoral reform, but SNTV legislators were not. The possible reasons are that SMD legislators might spend more time in constituent activities or avoid expressing their position on some controversial issues after they were elected in SMD after electoral reform (see more discussion in the section of interview).

Table 4. OLS model of absence rate

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses.

***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05, *P < 0.1.

As for control variables, it is worthy of discussing them. First, before electoral reform, it is expected that DPP legislators were less likely to be absent than KMT members because they needed to defend the government's policies. After electoral reform, because the KMT enjoyed the supermajority seats in the parliament, as mentioned in Rich's (Reference Rich2014) article, KMT members alternated attendance to ensure enough attendance rate. Second, legislators with local faction backgrounds were more likely to be absent from voting, but it is only statistically significant at a 90% confidential interval in the pre-reform period. Under MMD, legislators with local faction backgrounds might have more incentives to spend more time participating in constituent activities. Third, legislators who served more times as committee chairs were less likely to be absent from voting, particularly after reform, because they were party whips. Finally, legislators in the sixth term were less likely to be absent than those in the fifth term because no parties had majority seats. Besides, the ruling and opposition parties had an intense conflict due to President Chen's corruption scandal. Legislators in the eighth term were less likely to be absent than those in the seventh term because the KMT only had plurality seats (56.6%) in the parliament. Besides, President Ma also suffered from lower presidential approval. Both KMT and DPP legislators should have had a higher attendance rate.

To summarize, the findings based on the type 2 defection rate reject the hypotheses that predict no difference between local and list PR legislators. Instead, I found that after the reform, legislators elected by plurality rule in SMDs were more likely to defect from the party line than list PR legislators, a finding consistent with the ‘best of both worlds’ perspective (i.e., hypothesis 2). Before the reform, legislators elected by SNTV in districts with high magnitude had the highest defection rate.

The results for the model using only absences as the dependent variable show no statistically significant difference between SNTV and list PR legislators before the electoral reform and a higher absence level among legislators elected by plurality rule in SMDs after the reform. However, the extent to which this strengthened or weakened the hypotheses is unclear because previous literature had different interpretations of whether the absence should be viewed as defection.

7.3 Additional analysis of district legislators

District legislators faced the largest impact from electoral reform: DM decreases from MMD to SMD. District legislators are expected to be more likely to defect from the party line than list PR members because they need to represent their constituents. I additionally examined the behavior of district legislators and included two additional variables in the regressional models: nature log of DM and electoral security. Due to the limited length of the article, I described the analysis of district legislators in online Appendix D.

8. Evidence from the interviews

As presented above, Taiwanese parties have a high level of party unity. But the district legislators tended to defect from the party more often than list PR members. Several factors affected the relatively higher level of party unity in Taiwan and the mandate-divide on party unity. The following section describes the interviews that I conducted in summer 2019. When I cited an individual's remarks, I used a code name for anonymity (see online Appendix C for details).

8.1 High party unity in Taiwan

As noted in the previous analysis, I observed high levels of party unity in Taiwan. The reasons for this vary across the parties. Party culture is one of the reasons. KMT was a historically authoritarian party. It formerly employed a top-down leadership style, and most party members yielded obedience to the central party leadership. Although the KMT was intertwined with local factions, they had no preference for public policies except those affecting their benefits. As for the DPP, it was a party composed of many social groups that developed democratically. The different intraparty factions preferred to negotiate and debate. After a consensus is made, the party members must obey and defend the party's position.

When the KMT was an authoritarian party, the government was led by the party. In the 1980s, the authoritarian KMT valued the executive system more and disregarded the legislative system. The central party committee made the policies and instructed the Executive Yuan to initiate a given bill (Sheng, Reference Sheng2008). Once the party's central committee makes a decision, very few party members would oppose it (interviewee KML2). The party members voted for the party's position because they feared punishment. Most KMT party members yielded obedience to the central party leadership until 2000, when the KMT lost the presidential election for the first time and was reduced to being the opposition party in the 2001 congressional election. The KMT underwent a period of a party split. Many party members left and established the PFP, led by Chu-Yu Soong. The KMT's party unity then started to rise after the fifth term, when the KMT lost control of both government and parliament for the first time, and the PFP was established due to a party split. The members of KMT became more unified when they realized the value of controlling government (Sheng, Reference Sheng2008).

The KMT also had the ability to punish dissident members. In most cases, the KMT legislators voted in line with the party's decision. The KMT has many ways to maintain party disciplines, such as fines, party membership suspension, and expulsion. Such methods encourage party members to follow the command of party leaders (Sheng, Reference Sheng2008). In the cases where the party leaders commanded a ‘grade A mobilization (jiǎ jí dòng yuán),’ requesting all party legislators to be present on the floor and vote for the party's position, the dissenters would be punished. The absentees might also be punished unless they ask for an absence in advance. For instance, the party might make an exception for district legislators whose districts were farther away from parliament if they could not attend the meeting (interviewee KFP).

In contrast to the KMT, when the DPP was the opposition party, it was already a highly disciplined party and more united than the KMT. Several reasons explain why the DPP is more disciplined than the KMT. First, although their parliamentary party caucus members are elected each session, Chief Secretary Chien-Ming Ker remains in his position. An unwritten party law guarantees his status within the party. He is guaranteed renomination, and no one would challenge his leadership and primary election (interviewee KML1). The DPP's Chief Secretary is responsible for carrying through the will of the party.

Another reason was DPP's status as a minority in parliament. After the DPP assumed the reins of government for the first time, the status of minority government compelled the DPP members to unite more than before. The DPP even had a higher party unity level than the KMT because the majority opposition parties were usually able to contend against the ruling party (Sheng, Reference Sheng2008). After 2008, when the DPP lost both the presidential and congressional elections, its minority opposition party status forced party members to be more united to contend against the KMT, who enjoyed supermajority seats in parliament.

The DPP is well known for strict party discipline and punishment. All the DPP interviewees said their party discipline is stringent. Every Friday morning, all party legislators must attend the parliamentary party caucus. Party legislators can request absence two times per session in advance. If party legislators are absent from the parliamentary party caucus, they will be fined (interviewee DFP). The DPP allows party members to debate vigorously within the parliamentary party caucus. After a consensus is achieved, all party legislators have to obey the decision. If party members did not follow the parliamentary party caucus's decision and voted differently, they would be fined by the caucus (interviewee DFP). Fines are accrued any time they vote against the party or abstain from voting.Footnote 11 However, in some cases, if a certain policy violates personal beliefs or values, some legislators still accept a fine and choose to vote against the party (interviewee DFC).

Moreover, the DPP caucus records party members' defection behaviors and imposes a points-accumulation system on them. Party members who have a terrible record of defection behavior will be deprived of the right to select the committee they prefer and to serve as a committee chair or party whip (interviewee DFP). One's party membership might be suspended if their records are unacceptable. Suspension may affect party members' qualification to participate in the primary (interviewees DML1, DML3).

8.2 Mandate-divide on party unity

As noted in the previous section, I found support for hypothesis 3, which states that unity should be higher in the post-reform period. As discussed above, I argue two plausible answers for the increased unity found in the post-reform era: greater party control over nominations and the greater importance of party labels.

Parties play a more critical role in the nomination process of list PR legislators after the electoral reform. Parties adopted a more party-centered CSM because they had a strong incentive to provide an eye-catching list for the voters when voters can vote for a party after electoral reform. Since the parties control list PR candidates' nominations, list PR legislators rely on the party's nomination to stay in parliament (interviewee PMC). They are expected to be united and defend the party's position. After all, list PR legislators' power originates from the party, unlike the district legislators, whose power derives from the voters in the district (interviewee DFL1). List PR legislators are certain to be constrained by party leadership; a defector will not be nominated again in the next election or will be expelled from the party (interviewee DML1, DML2, KFP, PMC). List PR legislators are therefore expected to exhibit higher levels of loyalty. The worst potential outcome is that the party expels a list PR member from the party, losing their qualification as a legislator. However, district legislators still can retain the qualification to serve as a legislator even if they are expelled from the party (interviewee DFL3).Footnote 12 Consider the following statements from interviewees.

List PR legislators have to represent their parties to pursue their maximum interest. Today it is the party's choice to nominate me as list representative. I am responsible for my party, and my party has to be accountable to the people. After all, when voting, voters vote for the party, not for me. (Interviewee PMP)

List PR legislators may not inwardly agree with the party. Because the party nominates them, they cannot serve as a legislator once they have lost party membership. Even if a district legislator loses party membership, they can still be a legislator. They can run as an independent candidate in the next election. Whether they can be elected depends on their electoral strength. So, the list-PR legislators must have a higher party unity level than the district legislators because they are carrying the mission of a political party. (Interviewee DML1)

Second, the reputation of parties became more electorally important after the reform. On the one hand, for the district legislators, elections became a two-party battle under SMD (interviewee KML3). Though the legislators need to cultivate personal votes, the party's reputation greatly affects the voters' choice. SMDs are advantageous to big parties with a positive reputation and a high approval rate. When the party has a negative image, the design of SMD will backfire. The evidence is that the ruling party can own the majority seat in parliament after electoral reform. By contrast, under the SNTV-MMD, candidates from the same party would compete against each other, and small parties had a greater chance of winning office. Between 2001 and 2007, the ruling party (DPP) was always the minority party. Because party labels became more important after electoral reform, SMD legislators have a strong incentive to enhance the party's reputation.

On the other hand, party labels also became more important for the election of list PR legislators. Before the reform, voters did not choose lists; instead, they voted for SNTV candidates in fused lists that allocated PR seats. After the reform, voters cast two votes, one of which is for a party list. This change enhanced the role of party labels. Whether list PR candidates can be elected depends on the vote share that the party gains from the second ballot. List PR legislators should have an incentive to defend the party's policies. Since the party leaders control the nomination process, voting against the party and abstention might also endanger future nominations.

Third, SMD legislators faced larger electoral pressure from the electorate. Meanwhile, SMD candidates were selected with a more inclusive CSM. As described above and in online Appendix A, the parties adopted poll primary for selecting their candidates. Winning a poll survey is the only requirement in the primary. SMD legislators faced greater electoral pressure than SNTV legislators. In addition, it is easier for the electorate to hold their representatives accountable under an SMD. It is riskier for SMD legislators to take positions that differ from those of their constituents than for SNTV legislators.Footnote 13

Consequently, public opinion is the essential consideration in the minds of district legislators (interviewee KML1) because electorates' support is the district legislators' lifeline in the election (interviewee DFL2). Under the SNTV-MMD, the legislator could represent a specific group. After DM decreased from MMD to SMD, the district legislators now need to win the most votes in the SMD. They have to serve as a ‘catch-all’ representative (interviewee PMC).

It is not always easy for SMD legislators to choose between public opinion and the party's position. Absence is a good strategy to skirt controversial issues. Party leaders understood that district legislators faced such a dilemma. In some cases, party leaders sanctioned absences because the majority party leaders preferred party-sanctioned absences to outright dissident votes or abstention, which generated an image of party splits (Rich, Reference Rich2014). This may explain why there was a higher absence rate during roll-call vote sessions after electoral reform. Consider the following statement from legislator DML3:

Because Taiwan is a pluralistic society, the SMD ensures that the representative cannot help but play dumb, take a vague position on the issues, please both hostile sides, and avoid fundamental decisions. But this will not happen under the MMD. I like broccoli, and you want a carrot. [Literally translated as ‘everyone has their own fans!’] (Interviewee DML3)

Moreover, because there is only one representative in an SMD, the legislator is more identifiable. They have to put constituency interest in the first place; otherwise, they will lose in the next election (interviewee KML2). Some legislators said they would eventually follow public opinion when there is a conflict between the intended policy and public opinions. Consider the following statements from two legislators:

I am a representative elected by the constituents. I must represent the interests of my constituency. So, sometimes, the constituency's interests may not be 100% consistent with the political party's interests. When there is a conflict, I would definitely follow public opinion in my constituency. (Interviewee KML1)

For me, I will consider public opinion first during the eventual voting, then the party's position and personal values or ideals is the last thing I will consider. That does not mean I do not defend my values and ideals. I think I have to respect other people's thoughts. I do not feel that my personal values or ideals are wrong. But that is what democracy is. (Interviewee DML1)

In summary, the level of party unity in Taiwan was high, on the one hand, because of party culture. On the other, the parties enforced punishment to maintain party discipline. Under the SNTV-MMD, the parties might be more likely to take disciplinary measures against party members violating this principle because the legislators relied more on their personal vote to be elected. After electoral reform, two-party competition in the SMD battle has increased the importance of party labels and party image. Party members had incentives to defend the party's position and maintain an image of a united party. However, SMD legislators faced a larger cross-pressure from the party and constituents. Because SMD legislators had to win the support of majority voters in the district to be elected, they were more likely to defect from the party when public opinion expressed a clear position against the policy, even though the party would punish them. Whether SMD legislators chose to vote against their party or not depends on their calculation regarding the chance of reelection.

9. Conclusion

This article concentrates on evaluating the main hypotheses using the party defection rate. After describing the data and discussing the different possible measures, I examine the defection rate that measures the proportion of times a legislator voted against a majority of his or her party, considering abstentions as defections. The results reveal statistically significant differences between legislators elected in nominal and list districts. There is a mandate-divide between legislators elected from the district and party list. It is consistent with the ‘best of both worlds’ perspective. The results also show that levels of party unity were higher after the electoral reform, which is consistent with the second hypothesis. However, after electoral reform, SMD legislators had a higher absence rate than list PR members. The potential reasons are that SMD attempted to avoid their position on some controversial issues and spent more time in constituent activities.

In the part of the interview, I explained how party leaders employ mechanisms to encourage unity and punish potential defectors. Nonetheless, despite being potentially unlikely to find differences in electoral incentives among different types of legislators because of a high level of party unity in Taiwan, my findings show that electoral rules likely influenced differences in roll-call behavior. Although this article did not find that CSMs affected legislative behaviors, evidence stressing the influence of parties was revealed in the interviews: party leaders enforce various punishment mechanisms to enforce party discipline. The role of the party cannot be ignored. Therefore, it is why previous studies had no consistent findings on the mandate-divide mechanism under the mixed-member system. The future study of mandate-divide should consider the role of the party and cannot just focus on the electoral system.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1468109922000111 and https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/XM8HMI.

Conflict of interest

The author declares none.