Foreign aid has been one of the major tools of developed countries to attain their political objectives. Preceding studies often found that donors tend to disburse aid to advance their political and strategic interests, such as assisting governments of vital importance (Maizels and Nissanke, Reference Maizels and Nissanke1984; Schraeder et al., Reference Schraeder, Hook and Taylor1998; Alesina and Dollar, Reference Alesina and Dollar2000; Boschini and Olofsgård, Reference Boschini and Olofsgård2007; Fleck and Kilby, Reference Fleck and Kilby2010; Boutton and Carter, Reference Boutton and Carter2014) and/or altering the policies of recipients (Dunning, Reference Dunning2004; Kuziemko and Werker, Reference Kuziemko and Werker2006; Bueno de Mesquita and Smith, Reference Bueno de Mesquita and Smith2007; Dreher et al., Reference Dreher, Sturm and Vreeland2009a, Reference Dreher, Sturm and Vreeland2009b; Bearce and Tirone, Reference Bearce and Tirone2010; Lim and Vreeland, Reference Lim and Vreeland2013; Carter and Stone, Reference Carter and Stone2015) rather than merely meet recipients' needs. Although the use of aid to attain political objectives is not restricted to a particular donor, scholars often identify the US, the largest economy in the postwar era along with the greatest interest in maintaining global stability, as the most frequent user of aid as a foreign policy instrument because the efficacy of aid hinges largely on the resources available to the donor who disburses it (Meernik et al., Reference Meernik, Krueger and Poe1998; Apodaca and Stohl, Reference Apodaca and Stohl1999; Fleck and Kilby, Reference Fleck and Kilby2010).Footnote 1

Yet the efficacy of aid as a foreign policy tool depends also on the aid policies adopted by the others (Orr, Reference Orr1990: 144). If other donors join the US efforts, Washington is more likely to attain its political objectives. Conversely, if other donors take measures that will offset the impact of American foreign aid, the US needs to expend more resources to achieve its ends. As cooperation from other donors, particularly from its allies, certainly helps the US attain its overarching political objectives, the US often keeps a watchful eye on the flows of aid disbursed by other donors. There are potentially two directions in which the US would ask allies to assist its aid programs. One way is to complement its aid efforts: the US may urge its allies to disburse aid to the same recipients. Another way is to substitute its aid efforts: the US may pressure its allies to disburse aid to countries that receive little US aid. Depending on which direction the US presses the allies to disburse aid, the probability the US achieves its diplomatic objectives will shift because substitution entails the costs of losing control over several developing countries, allowing other donors to pursue their own interests. To see whether and how the US attempts to minimize this risk, I examine both the direction and magnitude of US influence on lesser powers' aid allocation by focusing on the relationship between the US and Japan.

Although the US has applied pressure on various subordinate states, I focus on this binary relationship because Japan has been one of the largest donors of bilateral aid during the period of this study (1971–2009).Footnote 2 Despite its significance, Japan's aid policy has been criticized for its responsiveness to gaiatsu (external pressure), especially the one from the US (Calder, Reference Calder1988; Orr, Reference Orr1990; Miyashita, Reference Miyashita1999, Reference Miyashta2003; Lancaster, Reference Lancaster, Leheny and Warren2010).Footnote 3 For instance, at the 1983 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) conference, ‘U.S. representatives reportedly presented Japanese delegates with a list of 20 countries for aid consideration, selected for their strategic importance’ (Yasutomo, Reference Yasutomo1986: 104). Moreover, since the 1970s, the US and Japan have regularly held aid consultations (Inada, Reference Inada1989: 402). Because postwar Japan depends heavily on the US for its security and trade, Japan frequently made concessions to demonstrate its willingness to support US foreign policy (Orr, Reference Orr1990: 17). However, this does not mean that Japan has always succumbed to US pressure. Interestingly enough, different studies found that Japan seeks commercial interests through aid delivery, and that such aid policies have been repeatedly criticized by US officials (Orr, Reference Orr1990: 125; Arase, Reference Arase1995; Hook and Zhang, Reference Hook and Zhang1998; Schraeder et al., Reference Schraeder, Hook and Taylor1998; Berthélemy and Tichit, Reference Berthélemy and Tichit2004). Why is there inconsistency in previous findings? Are there any variations in Japan's responsiveness to external pressure? If so, what determines these variations? I address these questions by shedding light on domestic politics of Japan. Japan's aid policy is predominantly determined by bureaucratic administrators (Inada, Reference Inada1989: 401), and different bureaucratic agencies are in charge of allocating grants and loans. Thus, I will analyze allocation of grants and loans separately to explore how differences in decision making influence the degree to which US interests shape Japan's aid policy.

I argue that the US applies pressure on Japan to complement its aid efforts rather than to substitute them because substitution will allow Japan to strengthen its ties with recipients and advance its own interests.Footnote 4 Such opportunistic behavior will reduce American influence on the recipients and prevent the US from achieving its overarching diplomatic objectives. To minimize this risk, the US pressures Japan to complement its aid efforts. I further assert that allocation of Japanese grants is more receptive to US pressure than that of loans because in Japan, grants are left to the discretion of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) that uses external pressure to win bureaucratic turf wars, whereas loans are determined through consultations among multiple bureaucratic agencies, including the one that represents the interests of Japanese domestic industry. Using a new dataset on Japan's Official Development Assistance (ODA) from 1971 to 2009, I estimate both ordinary least squares (OLS) and two-stage least squares (2SLS) regressions to handle the issues of reverse causality and joint decision-making. I also conduct case studies to demonstrate how Japan changed its aid policies in response to US pressure. The results of empirical analyses support the argument.

1. Related literature

The responsiveness of Japan's foreign policy, including its aid programs, to external (especially US) pressure has been widely discussed in the preceding studies (Calder, Reference Calder1988; Orr, Reference Orr1990; Miyashita, Reference Miyashita1999, Reference Miyashta2003; Lancaster, Reference Lancaster, Leheny and Warren2010). Past theoretical studies often attributed Japan's receptiveness to external pressure to its heavy reliance on American security guarantees (Lake, Reference Lake2009). Japan had no alternative alliance partners, and faced acute threats from China, the Soviet Union, and North Korea. Its self-imposed military constraints also exacerbated fears of US disengagement among the Japanese public (Cha, Reference Cha2000).Footnote 5 Preceding studies tended to assert that Japan disbursed aid in accordance with US interests in order to deflect American complaints about unequal burden-sharing and reinforce the US−Japan security tie. For instance, Lake (Reference Lake1999: 182) argued that Japan's postwar dependence on US protection made it impossible to have freedom in policy making. Similarly, Miyashita (Reference Miyashita1999) posited that Japan's responsiveness to American pressure is primarily a result of the asymmetric interdependence between them. Several empirical analyses on Japan's aid allocation provided evidence to support these claims (Katada, Reference Katada1997; Neumayer, Reference Neumayer2003).

However, different empirical studies reported that there are dissimilarities between US and Japanese aid patterns: whereas the US seeks to advance its geopolitical and ideological interests, Japan's aid is driven primarily by its commercial interests (Schraeder et al., Reference Schraeder, Hook and Taylor1998; Berthélemy and Tichit, Reference Berthélemy and Tichit2004). Indeed, even in the 1980s, on average 21% of Japanese aid went to socialist countries, whereas only 6% of US aid was directed to such regimes (Schraeder et al., Reference Schraeder, Hook and Taylor1998: 312). Provision of large volumes of aid from Japan to these countries during the Cold War arguably suggests that Japan was not entirely susceptive to US pressure. These mixed findings indicate that we need a different theoretical framework to understand variations in Japan's responsiveness to external pressure.

Moreover, preceding studies did not scrutinize the direction of US influence on Japan's aid patterns. As noted, there are potentially two directions in which the US might ask Japan to assist its aid programs: one is complementary and the other is substitution. Exploring the direction in which the US asks Japan to assist its aid programs is important because Japan's aid allocation affects the probability that Washington will achieve its diplomatic objectives. Since most previous studies did not explore why the US urged Japan to disburse aid to particular recipients, I provide a theoretical framework for the direction of US pressure on Japan's aid flows. Previous empirical studies also failed to exhibit consistent findings regarding US influence on Japan's aid policy as they tended to focus on one specific region or employ one particular type of assistance as a measure of American influence. The limited scope of their analyses resulted in mixed findings; whereas Katada (Reference Katada1997) found that in South and Central America, the US urges Japan to supplement its aid efforts, Neumayer (Reference Neumayer2003) demonstrated that Washington pressures Japan to complement its military assistance. Thus, it remains uncertain whether their findings will still hold even if we expand the scope of their analyses into different regions or employ a different measurement of US influence. A more systematic study needs to be conducted to provide more general insights into Japan's responsiveness to US pressure.

Another shortcoming of past studies is that they did not differentiate loans from grants,Footnote 6 even though they acknowledged that loans constituted a disproportionately large share of Japan's ODA.Footnote 7 The allocation of loans and grants deserves separate attention because different bureaucratic agencies participate in their allocation, and these differences in the policy-making process largely affect the degree to which US interests shape their provisions. Japan's strong sectionalism in bureaucracy has been widely discussed, and its impact on formulating aid policy has drawn particular scholarly attention (Rix, Reference Rix1980; Orr, Reference Orr1990; Lancaster, Reference Lancaster, Leheny and Warren2010). If each ministry or bureaucratic agent attempts to maximize parochial interests through aid delivery, then who participates in the decision-making process undoubtedly affects Japan's aid allocation. Because the ratio of loans to ODA varies from year to year and across regions, I conduct separate analyses of Japanese grants and loans to explore both the direction and magnitude of US pressure on their allocations, and examine how bureaucratic politics in Japan influences the degree to which it responds to external pressure.

2. The argument

In the postwar era, the US formed an alliance with Japan to maintain security in East Asia. Although the US agreed to carry a heavy defense burden to provide security guarantees for Japan, such defense policies have frequently met severe domestic criticism in the US as they seemed to allow Japan to free-ride on American defense efforts. To circumvent domestic criticisms, US officials constantly urged Japan to share the burden in other issue areas, including foreign aid.Footnote 8 The lack of domestic support for aid programs has also prompted the US government to pressure Japan to share the cost of aid delivery.Footnote 9 For instance, the former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger asserted that Japan should spend more on economic assistance rather than defense expenditures, and former US National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski articulated that Japan should increase its aid so that the total of both economic assistance and military spending reached 4% of GNP (Inada, Reference Inada1989: 400). President Jimmy Carter also urged Japan to expand its aid budget and share the financial burden (Orr, Reference Orr1990: 111).

Despite widespread public loathness to expand aid budget, foreign aid has been a major tool of the US government to advance its political interests. There seem to be at least two overarching objectives the US seeks to attain through aid provision. The first objective is the preservation of its sphere of influence by protecting the governments of strategically important locations from being toppled by anti-US rebels. There are ample historical examples in which the US has disbursed large volumes of aid to assist governments facing communist threats (e.g., Turkey and Greece) (Boschini and Olofsgård, Reference Boschini and Olofsgård2007)Footnote 10 or combating terrorist groups (e.g., Afghanistan and Iraq).Footnote 11 The second objective is to increase US bargaining power vis-à-vis the recipients so that it can facilitate reform of economic institutions (Bearce and Tirone, Reference Bearce and Tirone2010), promote democracy and human rights (Meernik et al., Reference Meernik, Krueger and Poe1998; Apodaca and Stohl, Reference Apodaca and Stohl1999; Lai Reference Lai2003; Dunning, Reference Dunning2004), and alter their voting behavior in multilateral institutions (Kuziemko and Werker, Reference Kuziemko and Werker2006; Dreher et al., Reference Dreher, Sturm and Vreeland2009a, Reference Dreher, Sturm and Vreeland2009b; Carter and Stone, Reference Carter and Stone2015). Regardless of the differences in US diplomatic objectives, I argue that the US would press Japan to complement its aid efforts rather than substitute them as substitution would allow Japan to increase its clout in the recipient and advance its own interests.

If the primary goal was to preserve its sphere of influence, the US would urge others to disburse aid in tandem. Although ideally, the US would let other donors assist pro-US governments on its behalf and reduce or eliminate the necessity for the US to provide aid, there are several reasons for the US not to adopt such a strategy. First, the volume of aid disbursed by other donors may not be sufficient to maintain pro-US regimes because no ally has financial resources comparable to those of the US. Second, the US administration would face global criticism if it reduced its aid levels substantially. For instance, when a proposal for reducing US aid by 45% was leaked, the Japanese government protested that ‘in the context of substantially reduced U.S. aid levels, it would be difficult to defend’ the new aid budget in the Diet (Orr, Reference Orr1988: 751). Third, the withdrawal of US aid may increase the risk that other donors will act opportunistically: once lesser powers find that the US has lost its influence over particular states, they may attempt to enhance their own clout in them. Because a limited US presence would reduce its global influence and future diplomatic and investment opportunities, the US government would not dare focus on a small number of recipients (Bigsten, Reference Bigsten2006: 21; Knack and Rahman, Reference Knack and Rahman2007: 195; Frot and Santiso, Reference Frot and Santiso2011: 65). Thus, the US attempts to retain influence on strategically important states and prevent other donors from increasing their clout in them.

If the primary purpose of US aid provision was to alter the behavior or policies of recipients, the US would also urge other donors to provide aid in tandem so that it could enhance its bargaining leverage with recipients while minimizing the risk of other donors seeking their own interests. If the US asks other donors to provide aid to a particular state in accordance with the initiation of its aid programs, the recipient may become more inclined to comply with American demand. If the US urges other donors to redirect their aid in accordance with the withdrawal of its aid, recipients are more likely to succumb to US threats because failure to follow US requests would mean the withdrawal of aid from multiple sources. By urging other donors to withdraw aid simultaneously, the US could also prevent them from enhancing their bargaining leverage vis-à-vis recipients. If the US instead focused on fewer recipients and allowed others to advance their interests, such as monopolizing the market of a developing country, the US would find it more difficult to convince them to withdraw aid as their benefits of maintaining relations with the recipient may surpass the costs of circumventing US pressure. For this reason, Washington urged allies to withdraw aid from the Sandinista Nicaragua in tandem with the US (Orr, Reference Orr1990: 144). Similarly, following the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia in 1978, the US officials pressured Japan to subdue the opinion of continuously providing Japan's aid to Hanoi as they suspected that Japan took this opportunity to advance its commercial interests (Orr, Reference Orr1990: 122). Accordingly, I derive the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: US aid patterns have a positive impact on the allocation of Japan's ODA, meaning that Japan tends to disburse aid in line with the US.

Although the US has constantly pressured Japan to disburse aid in tandem, Japan's aid flows do not always coincide with US aid patterns because aid allocation is ultimately determined by domestic actors within Japan. Japan has never had an aid ministry, and decisions on aid allocation to individual recipients are left up to administration after the Diet approves the total aid budget (Yasutomo, Reference Yasutomo1986: 67; Inada, Reference Inada1989: 406; Orr, Reference Orr1990: 24). Participants in the decision-making process differ between grants and loans, and this substantially affects the impact of external pressure on their allocation. Allocation of grants is largely left to the discretion of the MOFA (Orr, Reference Orr1990: 30; Arase, Reference Arase1994: 178),Footnote 12 which is the lead agency in foreign affairs and has close ties with representatives from other countries. Yet this ministry lacks a strong domestic constituency and needs backing from abroad to preserve its influence within the bureaucracy (Orr, Reference Orr1990: 107; Miyashita, Reference Miyashita1999: 707). According to Orr (Reference Orr1990: 13), MOFA sometimes urged the US ‘to apply pressure in order to bolster the Ministry's position relative to other ministries on many bilateral issues.’ MOFA's sensitivity to global criticism as well as its desire to win bureaucratic turf battles enabled the US to have profound influence on the allocation of Japanese grants.Footnote 13

In contrast, the allocation of loans has been determined through consultations among three (previously four) agencies (Orr, Reference Orr1990: 30; Arase, Reference Arase1994: 178). In addition to MOFA, the Ministry for Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI) and the Ministry of Finance participate in allocation decisions.Footnote 14 The involvement of multiple agencies reduces MOFA's influence in the policy-making process and exacerbates the pulling and hauling among various bureaucratic agencies. In particular, METI, which represents the interests of Japanese industry, often seeks to advance the country's commercial interests.Footnote 15 Because Japanese loan programs frequently entailed construction of large-scale infrastructure in recipient states, they could bring considerable benefits to contractors. Therefore, numerous Japanese business companies, especially construction firms and trading companies, have carried out intense lobbying in Japan (Orr, Reference Orr1990: 28). To protect and promote their interests, METI has been encouraging to direct aid to countries with a high economic potential for Japanese firms. According to Orr (Reference Orr1990: 37), ‘MITI never opposes extending assistance to communist countries based on political grounds.’Footnote 16 Consequently, even during the Cold War, large volumes of yen loans were extended to communist countries, such as China and Laos (Inada, Reference Inada1989: 405). Accordingly, the involvement of multiple agencies in the policy-making process reduces the impact of external pressure on the allocation of yen loans.

I further suspect that the characteristics of Japanese loans may also reduce the impact of US pressure on their allocation. Japanese ministries and agencies tend to become more selective when determining loan recipients. Contrary to grant aid, loans require repayment, and insolvency or even delay in repayment could cause serious financial loss to the lender. Japanese loan programs rely heavily on borrowing from the Fiscal Investment and Loan Program (FILP) and the General Account budget (Arase, Reference Arase1995: 199).Footnote 17 Default means the loss of savings and pensions of Japanese citizens, which will immediately provoke domestic repercussions. Therefore, ministries and bureaucratic agencies, including MOFA, become more selective in determining loan recipients to ensure that loans are paid back in full. Orr (Reference Orr1990: 59) states that ‘[a]id, especially yen loans, demonstrates the government's confidence in a recipient country's stability.’ The desire to avoid default also seems to reduce the impact of US pressure on the allocation of loans. Accordingly, I derive the second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: The allocation of Japanese grants is more susceptible to US pressure than that of loans.

3. Research design

I utilize the following five variables as the dependent variables of this study: the volumes of Japanese grants, technical assistance,Footnote 18 grants-tech (i.e., the aggregates of grants and technical assistance), the net disbursement of loans, and the net disbursement of ODA (i.e., the aggregates of grants-tech and loans) to each country in a given year (in constant 2015 US dollars).Footnote 19 The data come from MOFA's website (MOFA, 2016) and the sample covers both developed and developing countries for the period 1971−2009.Footnote 20 I take the natural logarithm of these variables (plus one) as they are highly right skewed. Although the bulk of studies on aid allocation use OECD data, I employ MOFA's dataset for the following reasons. First, it contains no missing values from 1969 to 2014.Footnote 21 A comparison between MOFA and the OECD data reveals that 1,875 observations (28% of the total) are missing from the OECD data between 1971 and 2009.Footnote 22 Second, MOFA data have a record of aid flows from Japan to countries not on the DAC's list. The OECD defines foreign aid as ODA if it is directed toward states on the DAC list and if it satisfies the condition of a grant element of at least 25%.Footnote 23 However, in reality, donors frequently give aid to countries not placed on the list, especially if the latter suffer catastrophic losses from natural disasters. Indeed, Japan extended its aid even to some OECD countries.Footnote 24 The use of MOFA data, therefore, helps us avoid sample selection bias. Third, MOFA data contain separate observations of various types of Japanese aid, allowing us to examine the differences across them.Footnote 25

I utilize US aid as the key independent variable for this analysis. This variable measures the sum of US economic and military assistance, both of which come from the US Agency for International Development (USAID, 2016). I take the natural logarithm of this variable (plus one). When estimating OLS regressions, I use this variable in one year lag. If Japanese decision-makers allocate foreign aid based on US aid allocation in the previous year, the use of a lagged variable is justified. When estimating 2SLS regressions, however, I employ the unlagged variable to allow for the possibility that the US and Japan jointly determine their aid levels. I expect that the estimated coefficients have a positive sign, and that the coefficient I obtain when using grants as the dependent variable is greater than the one I obtain when using loans as the dependent variable.

I include a series of control variables found in the literature on the determinants of foreign aid. First, I include three variables that measure recipients' economic need. One is the natural logarithm of per capita gross domestic product (GDP), taken from the United Nations Statistics Division (UNSD, 2016). The 1992 ODA Charter of Japan articulates that humanitarian concerns (i.e., poverty reduction) are one of the primary objectives of Japan's ODA (MOFA, 1992: Secs. 2.4, 3.2[b]),Footnote 26 and preceding studies demonstrated that lower income levels are associated with higher aid levels (Chan, Reference Chan1992: 11; Katada, Reference Katada1997; Schraeder et al., Reference Schraeder, Hook and Taylor1998; Tuman and Ayoub, Reference Tuman and Ayoub2004; Tuman et al., Reference Tuman, Strand and Emmert2009). I expect that grants are more likely to be directed to least developed countries partly because the recipients do not have to repay the debt, and partly because the Japanese government is more selective in loan recipients.

Next, I include the natural logarithm of population taken from the UNSD (2016). Although large populations generally enhance economic growth, previous research found a strong negative relationship between population size and Japan's aid volumes (Katada, Reference Katada1997; Tuman et al., Reference Tuman, Strand and Emmert2009) and attributed this outcome to the fact that each country has a vote in the UN General Assembly (UNGA) and the votes of smaller states are less expensive to buy off (Katada, Reference Katada1997: 941). Thus, population is expected to have a negative impact on the allocation of grants and loans.

Trade has been regarded as a key determinant of Japanese aid flows as Japan needs to expand its export markets and secure imports of raw materials owing to a small domestic market and the lack of natural resources (Chan, Reference Chan1992: 7). Nevertheless, the findings of past studies are mixed. While some reported that there is a positive relationship between trade and Japan's aid flows (Maizels and Nissanke, Reference Maizels and Nissanke1984; Schraeder et al., Reference Schraeder, Hook and Taylor1998; Tuman and Ayoub, Reference Tuman and Ayoub2004), others found that the ratio of trade to GDP is negatively associated with aid levels (Tuman et al., Reference Tuman, Strand and Emmert2009), and still others found no relationship between them (Chan, Reference Chan1992: 13). I employ the natural logarithm of the sum of exports and imports between Japan and a country (plus one). The original data on trade are taken from the International Monetary Fund (IMF, 2016).Footnote 27 I suspect that trade is positively associated with both grants and loans, albeit more so to loans because wealthier states tend to trade more with Japan and are less likely to go into default.

Second, to control for the effects of the recipients' policy orientation, I introduce democracy, policy distance, and war into the analysis. Democracy is an indicator variable, coded 1 if a country has a democratic government and 0 otherwise. This variable comes from Cheibub et al. (Reference Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland2010). The spread of democracy has been one of the ideological goals of the US (Meernik et al., Reference Meernik, Krueger and Poe1998; Apodaca and Stohl, Reference Apodaca and Stohl1999; Lai, Reference Lai2003; Dunning, Reference Dunning2004), and previous research found that the US tends to disburse more aid to democratic states (Alesina and Dollar, Reference Alesina and Dollar2000: 49). Japan has historically assisted fledgling democracies to signal its support for this ideological goal of the US. For example, during the 1980s, Japan disbursed aid to recently democratized countries such as Jamaica (Brooks and Orr, Reference Brooks and Orr1985: 333), and the 1992 ODA Charter announced that democratization is one of the determinants of Japan's ODA (MOFA, 1992). Preceding studies found that Japan's ODA is associated with democratic regimes (Tuman and Ayoub, Reference Tuman and Ayoub2004; Tuman et al., Reference Tuman, Strand and Emmert2009). Therefore, I speculate that democracy has a positive impact on the allocation of Japanese grants and loans.

Previous research found a positive relationship between states' voting patterns at the UNGA and aid flows (Alesina and Dollar, Reference Alesina and Dollar2000: 46). Thus, I introduce policy distance, which measures the absolute distance between the ideal point estimate of Japan and that of each state in a given year. The data on ideal point estimates come from Voeten et al. (Reference Voeten, Strezhnev and Bailey2009). The longer the distance between their ideal points, the less likely it is that they vote in tandem. I expect that policy distance has a negative impact on the allocation of Japan's grants and loans.

I also include war, an indicator variable, which takes the value of 1 if the recipient is a primary party to an inter- or intra-state conflict and 0 otherwise. I create this variable based on the UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset (Pettersson and Wallensteen, Reference Pettersson and Wallensteen2015). Since 1945, Japan has embraced the idea of ‘heiwa kokka,’ a peace-loving nation, and used its aid as a tool to signal its pacifist spirit (Yasutomo, Reference Yasutomo1989–1990: 502). The 1992 ODA Charter declares that recipients' military spending and arms exports are determinants of Japan's ODA (MOFA, 1992). Japan is particularly reluctant to extend loans to war-torn states partly because they are less likely to repay the debt, and partly because the safety of the personnel, who are to be dispatched if a Japanese corporation wins the bidding, is not ensured.Footnote 28 For the same reason, Japan seems to refrain from sending technical experts to conflict zones. Accordingly, Japanese aid, especially loans and technical assistance, is less likely to be directed to countries engaged in armed conflicts.

Third, to control for the effects of natural disasters on aid allocations, I include total deaths, a variable that measures the natural logarithm of the number of deaths (plus one) caused by natural disasters that took place in a country in a given year. This variable comes from EM-DAT (CRED, 2016). Several scholars assert that donors disburse ODA to countries that have recently suffered from natural disasters regardless of their economic development (Frot and Santiso, Reference Frot and Santiso2011). I expect that as the number of deaths caused by natural disasters increases, Japan is more inclined to disburse aid, especially grant aid, to affected countries.

Fourth, I include attacks on Japanese, a variable that counts the number of terrorist attacks targeting Japanese citizens in a country. The original data are derived from the Global Terrorism Database (GTD) (START, 2016), and I take the natural logarithm (plus one). An attack launched against Japanese citizens seems to stimulate a domestic backlash, and the Japanese government is compelled to take measures to prevent the recurrence of such tragic events. I expect that this variable has a positive impact on the allocation of Japan's grants because they seem to work effectively in assisting recipient governments. However, the Japanese government might be reluctant to allow its citizens to be dispatched to countries where their safety is not guaranteed. Thus, I expect that this variable has a negative impact on the allocation of loans and technical assistance.

Fifth, I include UNSC member, an indicator variable, coded 1 if a country is a temporary member of the UNSC and 0 otherwise.Footnote 29 There has been a growing concern over major powers' vote-buying at the UNSC (Kuziemko and Werker, Reference Kuziemko and Werker2006; Dreher et al., Reference Dreher, Sturm and Vreeland2009a, Reference Dreher, Sturm and Vreeland2009b). Lim and Vreeland (Reference Lim and Vreeland2013) demonstrated that aid from the Asian Development Bank (AsDB) tends to surge dramatically while the recipient is serving on the UNSC, and they used this finding as evidence for Japan's attempt to influence the Council's resolutions. If Japan also aims to alter voting patterns through bilateral channels, the flows of Japanese grants and loans must have a positive relationship with this variable. Summary statistics are presented in the Supplementary files.Footnote 30

4. Results

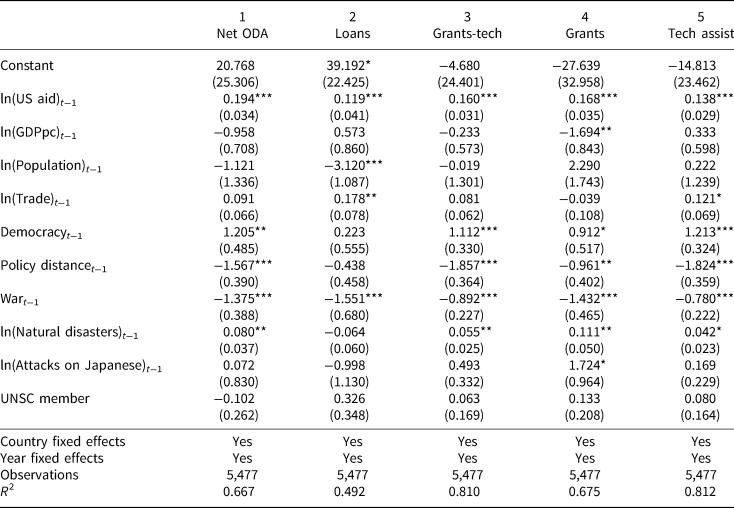

Table 1 reports the results of OLS regressions. The dependent variables in columns 1–5 are (Japanese) net disbursement of ODA, loans, grants-tech, grants, and technical assistance (tech assist), respectively. The coefficient estimates of US aid in all columns have a positive sign and statistical significance, supporting Hypothesis 1. It is noteworthy that this result holds even after I control for recipients' economic strength and humanitarian concerns, suggesting that Japan disburses aid in line with the US not simply because they compete over export markets or care victims of natural disasters. Moreover, the comparison between the coefficients in columns 2–5 reveals that ceteris paribus, the allocation of yen loans (0.12 in column 2) is less receptive to US influence than that of grants (0.16, 0.17, and 0.14 in columns 3–5, respectively). The results of Seemingly Unrelated Regressions also suggest that the estimated coefficient for loans is indeed smaller than the ones for grants and grants-tech, supporting Hypothesis 2.Footnote 31

Table 1. Results of OLS regressions

Clustered standard errors are reported within parentheses. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01 (two-tailed).

Table 1 further reveals that Japan allocated grants and loans for different purposes. The estimated coefficients of GDP per capita in columns 1, 3, and 4 are negative, whereas those in columns 2 and 5 are positive. The statistical significance in column 4 means that ceteris paribus as a state becomes wealthier, it is less likely to receive grants from Japan. The coefficient estimates of population are negative in columns 1–3, whereas those in columns 4–5 are positive. Only the coefficient in column 2 is statistically significant, suggesting that ceteris paribus as a state's population grows, Japan becomes less inclined to extend loans to that state. The estimated coefficients of trade are positive in all columns (except column 4), although only those in columns 2 and 5 are statistically significant. Thus, ceteris paribus as the volumes of trade between Japan and a recipient increase, Japan tends to raise the levels of loans and technical assistance to that state.

A country's policy orientation seems to be associated with the allocation of Japan's ODA. The coefficient estimates of democracy are positive and statistically significant in all columns (except column 2). Therefore, all else equal, Japan tends to increase the levels of grants once a country is democratized. Similarly, the negative significant sign of policy distance (except column 2) suggests that ceteris paribus as policy distance between Japan and a country widens, Japan is less inclined to give grants to that state. The estimated coefficients of war are negative and statistically significant in all columns, indicating that Japan has a strong disinclination to disburse both loans and grants to the countries at war. Although Japan's ODA has been criticized for its lack of a consistent aid philosophy (Yasutomo, Reference Yasutomo1986: 14; Hook and Zhang, Reference Hook and Zhang1998), this anti-war orientation has been upheld since the Ohira cabinet (1978–1980), which refused to disburse aid to countries engaging in armed conflict (Yasutomo, Reference Yasutomo1986: 43). The coefficient in column 2, however, is much smaller than the one in column 5, suggesting that even if a country is involved in armed conflict, Japan may not reduce the amount of technical assistance as much as the volume of loans.

The estimated coefficients of natural disasters are positive and statistically significant in all columns (except column 2), although their sizes are relatively small. Therefore, all else equal, Japan tends to increase the levels of grants and technical assistance, albeit slightly, as the number of deaths caused by natural disasters rises. The estimated coefficients of attacks on Japanese are positive in all columns (except column 2) but only coefficient in column 4 is statistically significant. Thus, ceteris paribus Japan disburses more grants as the number of attacks targeting Japanese nationals in a country increases, although the relatively large size of standard errors means that uncertainty surrounding the effects of terrorism on Japan's aid disbursements remains high.

Surprisingly, membership of the UNSC does not seem to be associated with the allocation of Japan's ODA. The estimated coefficients of UNSC member are not statistically significant in all columns and their sizes are equally small (except column 2). This result contradicts with the findings of previous research on Japan's aid allocation (Vreeland and Dreher, Reference Vreeland and Dreher2014: 149–157), US aid allocation (Kuziemko and Werker, Reference Kuziemko and Werker2006), German aid allocation (Dreher et al., Reference Dreher, Nunnenkamp and Schmaljohann2015), and aid disbursements by multilateral institutions (Dreher et al., Reference Dreher, Sturm and Vreeland2009a, Reference Dreher, Sturm and Vreeland2009b; Lim and Vreeland, Reference Lim and Vreeland2013). To find out why our findings are mixed, I estimate regressions with different specifications and different data sets.Footnote 32 The overall results suggest that the inconsistencies stem from the use of different data sets. I also speculate that the outcome misses statistical significance partly because Japan has utilized its aid programs to secure a temporary seat at the UNSC rather than to influence its resolutions, and partly because since 1971, Japan has used multilateral channels rather than bilateral ones to conceal its exercise of power over the recipient (Lim and Vreeland, Reference Lim and Vreeland2013).Footnote 33

5. Issues of endogeneity

Although the results of OLS regressions support both Hypotheses 1 and 2, OLS estimates would be biased upward if Japanese aid levels raise US aid volumes, whereas they would be biased downward if Japanese aid levels reduce the supply of US aid. To tackle the issues of reverse causality and joint decision-making, I estimate 2SLS regressions using US attacks as an instrument. This variable counts the number of terrorist attacks targeting US nationals in a potential recipient state in year t − 1 (START, 2016). I take the natural logarithm of this variable (plus one). I consider the following system of equations:

$$A_{it} = \alpha Z_{it-1} + {\bi X}_{{\bi it}}\Gamma + \delta _t + \psi _i + \varepsilon _{it}, \;$$

$$A_{it} = \alpha Z_{it-1} + {\bi X}_{{\bi it}}\Gamma + \delta _t + \psi _i + \varepsilon _{it}, \;$$ $$Y_{it} = \beta A_{it} + {\bi X}_{{\bi it}}\Gamma + \delta _t + \psi _i + \nu _{it}.$$

$$Y_{it} = \beta A_{it} + {\bi X}_{{\bi it}}\Gamma + \delta _t + \psi _i + \nu _{it}.$$ Equation (1) is the first stage of the 2SLS system and equation (2) is the second stage. The variable A it is the endogenous variable of interest, the volume of US aid disbursed to a particular recipient i in year t. Xit is a vector of country-year covariates, Y it denotes Japan's aid, δ t is year fixed effects, ψ i is country fixed effects, and Z it−1 denotes US attacks. The error term ɛit in (1) (or ν it in (2)) captures all factors that affect US aid (Japan's aid) other than covariates and fixed effects. OLS estimator of equation (2) would be biased if these two error terms are correlated owing to the presence of unobservable common factors (i.e., omitted variables) that affect both US and Japanese aid policies. To overcome the endogeneity problem, I estimate equation (1) and save the fitted values  $\hat{A}_{it}$, which are defined as

$\hat{A}_{it}$, which are defined as

$$\hat{A}_{it} = \alpha Z_{it-1} + {\bi X}_{it}\Gamma + \delta _t + \psi _i.$$

$$\hat{A}_{it} = \alpha Z_{it-1} + {\bi X}_{it}\Gamma + \delta _t + \psi _i.$$ That is,  $\hat{A}_{it}$ exclude the residual of the first-stage regression that is possibly correlated with ν it. The 2SLS second stage regresses Y it on

$\hat{A}_{it}$ exclude the residual of the first-stage regression that is possibly correlated with ν it. The 2SLS second stage regresses Y it on  $\hat{A}_{it}$, Xit, and the fixed effects. This means that the 2SLS estimator is consistent even in the presence of the omitted variables (Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge2013).

$\hat{A}_{it}$, Xit, and the fixed effects. This means that the 2SLS estimator is consistent even in the presence of the omitted variables (Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge2013).

The instrumental variable must satisfy the following two conditions. First, it must be correlated with the endogenous regressor (i.e., US aid). Previous research demonstrated that the US tends to disburse more aid as the number of terrorist attacks targeting Americans increases (Boutton and Carter, Reference Boutton and Carter2014). I also find that the coefficient of US attacks in the first stage is positive and statistically significant (see column 6 in Table 2). According to Neumayer and Plümper (Reference Neumayer and Plümper2011), US citizens frequently fall victim to international terrorism, and they attributed this fact to the extensive presence of US military personnel outside the homeland. Since World War II, the US has formed security alliances with numerous countries and stationed its troops inside their territories to preserve its strategic interests and maintain global stability. For terrorist groups, however, the presence of US troops appears to be both a threat to their existence and a hindrance to the achievement of their political goals. Thus, they often choose US personnel as the primary target of their attacks (Crenshaw, Reference Crenshaw2001: 432). Following attacks, the US government frequently increases its aid levels to assist the government of the targeted state, to restore public order, and to improve security.

Table 2. Results of 2SLS regressions

Clustered standard errors are reported in parentheses. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01 (two-tailed).

The Kleibergen−Paap rk Wald F statistic is 18.505 in columns 1–5.

Second, the instrument must be uncorrelated with the structural error term. Previous research on aid allocation and Japanese foreign policy suggests that the second condition also holds. In the postwar era, the general public in Japan tends to think Japan should uphold Article 9 of the Constitution, which strictly prohibits the possession of a military and the use of troops except for defensive purposes. Although the Japanese government attempted to expand the mandate of Self-Defense Forces (SDF) by passing the International Peace Cooperation Law in 1992, the actual participation of SDF in UN peacekeeping missions remained low. Owing to the limited presence of troops abroad, Japanese nationals have been less susceptible to terrorist attacks than Americans. This means that US attacks and attacks on Japanese are not correlated, and that the instrument is unlikely to have a direct impact on the allocation of Japan's ODA, although it may still affect the latter through US aid allocation. In addition, previous research on aid delivery revealed that the US may not increase its aid levels after observing terrorist attacks against foreign nationals. For example, Boutton and Carter (Reference Boutton and Carter2014) found no evidence that US aid levels are associated with the number of terrorist attacks targeting non-US nationals, even if the victims are from a formal ally of the US. Given that even the US, which possesses the interests in maintaining global stability, is reluctant to disburse aid to protect the interests of its allies, the lesser powers, which normally do not possess such interests, are unlikely to voluntarily increase their aid levels following the incidents targeting US nationals. Indeed, Potter and Van Belle (Reference Potter and Van Belle2004) found no evidence that Japan's aid allocation is associated with negative media coverage, such as global terrorist activities. Note that even at the onset of the War on Terror, the US government had to urge Japan to disburse aid to neighboring states of Afghanistan (MOFA, 2002).

These findings suggest that in the absence of US pressure, Japan is unlikely to give aid to compensate the damage caused by terrorism or to show its sympathy to foreign victims of terrorist attacks. To determine the validity of this claim, I perform the following placebo tests. First, I estimate OLS regressions including a variable that counts the number of terrorist attacks targeting British nationals in a country. Second, I estimate OLS regressions with a variable counting the total number of terrorist attacks minus the number of terrorist attacks targeting US and Japanese nationals in a country. I find that neither of these variables has a positive and significant influence on the allocation of Japan's ODA.Footnote 34 I also estimate 2SLS regressions with another instrumental variable and test for the validity of overidentifying restrictions.Footnote 35 Hansen's J statistic fails to reject the null hypothesis that all overidentifying restrictions are jointly valid at the 5% level.

As long as these two conditions are met, Z can be used to estimate the causal effect of US aid on Japan's aid (Morgan and Winship, Reference Morgan and Winship2015). Table 2 presents results of 2SLS estimation.Footnote 36 Column 6 reports the results of the first stage.Footnote 37 The estimated coefficient of US attacks has the expected positive sign, meaning that terrorist attacks increase the volume of US foreign aid. Columns 1–5 present the results of the second stage. The estimated coefficients of US aid are positive and statistically significant in columns 1 and 3–5, although the loss of statistical significance in column 2 seems to be caused by the increase in standard errors. Because the result in column 2 does not pass the robust regression-based test,Footnote 38 here I compare the estimate in column 2 in Table 1 and those in columns 1 and 3–5 in Table 2.Footnote 39 Because the IV influences the volume of Japanese aid only through US aid (see Fig. 1), I interpret the coefficient of interest, β, in (2) as showing the causal effect of a change in US aid, which is induced by the change in US attacks, on the change in Japan's aid.Footnote 40 The estimates imply that an additional 1% rise in US aid, caused by terrorist attacks, will increase Japan's net ODA, grants-tech, grants, and technical assistance by 0.79, 0.46, 0.59, and 0.36%, respectively. Since the increase in loans is just 0.12% (column 2 in Table 1), I conclude that the supply of US aid has a greater impact on the allocation of grants than that of loans, thereby supporting Hypothesis 2. Although there are several differences between Tables 1 and 2,Footnote 41 the central results regarding the impact of US aid on Japan's aid allocation remain intact (i.e., Hypotheses 1 and 2 are supported).

Fig. 1. A causal graph.

One may think that the increase in Japan's aid to a US strategic location followed by the increase in American aid does not necessarily mean that the US applied pressure on Japan to disburse aid to the particular recipient because Japan, which anticipated future US pressure, might have voluntarily increased its aid to that country. However, I disagree with this interpretation due to the following reasons. First, until the US exerts pressure, Japanese officials are not certain whether the change in Japan's policy actually meets US interests because the US may wish to exclude interference from other countries. Second, US pressure helps the MOFA convince other bureaucratic agencies of the necessity of changing Japan's aid policy. To strengthen its bargaining power, therefore, MOFA officials have an incentive to wait for US pressure. Third, Japan has employed its aid policy to signal its willingness to assist US overarching political objectives. If Japan altered its aid policy before the US applying pressure, it could not credibly signal its willingness because Washington might perceive that Japan is simply advancing self-interests. To demonstrate that Japan sacrifices its interests to accommodate US concerns, Japan needs to wait for US pressure before changing its aid policy. Indeed, in all cases I examined (see the next section), I found that Japan shifted its aid policy after it faced US pressure. The combined results of quantitative and qualitative analyses, therefore, suggest that Japan's aid has been receptive to US pressure.

To evaluate the robustness of my empirical results, I conducted a series of additional tests, and reported the results in the Supplementary files. The central findings remained largely unaffected.

6. Cases

The findings in the previous section reveal that when American strategic interests were threatened by terrorist activities, the US tended to increase its foreign aid to the affected state in the following year and apply pressure on Japan to follow suit. Yet combatting terrorism is just one of the many motives that drive US aid provision. To see how other interests prompt the US to exert pressure on Japan, and whether Japan changes its aid programs in response to US pressure, I conducted case studies. The cases include Nicaragua, the Gulf War, Vietnam, China, Russia, and North Korea; however, I only present the case of China in this paper and relegate other cases to the Supplementary files.

7. China

When the Chinese government brutally suppressed prodemocracy demonstrators in Tiananmen Square on 4 June 1989, the US and major European powers strongly accused China of human rights abuses, and decided to impose economic and diplomatic sanctions against it. US President George H.W. Bush publicly deplored the military crackdown and suspended arms sales to China (Skidmore and Gates, Reference Skidmore and Gates1997: 521). Sino−American relations became further strained over the treatment of Fang Lizhi, a Chinese prodemocracy activist who was in the custody of the American embassy in Beijing. Although the US granted asylum to Fang, the Chinese government issued an arrest warrant for this political dissident (Miyashita, Reference Miyashta2003: 61–62). On 20 June, President Bush, under pressure from the Congress, expressed his opposition to World Bank loans to China, and on 26 June, the World Bank announced the suspension of these loans (Kesavan, Reference Kesavan1990). On 29 June, the US House of Representatives passed an amendment to the foreign aid bill, introducing more sanctions on China. The amendment was also approved by the Senate on 14 July (Skidmore and Gates, Reference Skidmore and Gates1997: 522).

Japan was initially reluctant to take punitive measures against China. On 7 June, Prime Minister Sosuke Uno stated that while the military crackdown was regrettable, he would refrain from denouncing the Chinese government. He also denied that Japan might apply sanctions against China (Kesavan, Reference Kesavan1990: 672). Similarly, Foreign Minister Hiroshi Mitsuzuka stated that he was not yet thinking of taking punitive action against China (Kesavan, Reference Kesavan1990: 672). The Japanese government believed that sanctions were counterproductive as they would provoke Chinese nationalistic sentiments and jeopardize the Sino−Japanese relationship (Miyashita, Reference Miyashta2003: 58). Japanese corporations were also opposed to the suspension of aid as they had high commercial stakes in China (Miyashita, Reference Miyashta2003: 56).

Japan's reluctance to take punitive measures against China provoked vehement criticism from the US and Western European countries. The Western media accused Japan of taking a soft line on China's human rights abuses and suspected that Japanese firms were seeking to monopolize the Chinese market by sending their staff back to China soon after the incident (Miyashita, Reference Miyashta2003: 59). The US Congress also hardened its criticism of Japan's equivocal position on China's human rights abuses (Kesavan, Reference Kesavan1990: 675). In response to this mounting international criticism, on 20 June 1990, the MOFA announced that it would postpone the introduction of the third aid package ($5.2 billion loan program) to China (Miyashita, Reference Miyashta2003: 59). Although MOFA officials did not believe that sanctions were effective in altering China's behavior, they decided to act in concert with Western countries to avoid provoking the US Congress and avert international isolation (Zhao, Reference Zhao, Koppel and Orr1993: 170–171; Miyashita, Reference Miyashta2003: 56, 70).

Shortly after the suspension of Japan's ODA, Japanese policymakers and business leaders called for the early resumption of loans and normalization of relations with Beijing. Yet MOFA officials and the Foreign Ministry, who were under strong foreign pressure, objected to the resumption of foreign aid. For instance, when the new Prime Minister Toshiki Kaifu attempted to partially resume the yen loans, the Foreign Ministry suggested that it would not be a good idea to resume aid without US consent. In particular, Deputy Foreign Minister Takakazu Kuriyama and Vice Minister for International Affairs Hisashi Ogawa stated that ‘Japan's unilateral action might cause a major strain in U.S.-Japan relations and alienate Japan from the other G-7 members’ (Miyashita, Reference Miyashta2003: 66).

US pressure on Japan to sustain a freeze on aid mounted following the deterioration of the Sino−US relationship over the Fang incident. In October 1989, US Undersecretary of State Robert Kimmitt warned Japanese Vice Foreign Minister Hisashi Owada that the US government would not abruptly lift the aid sanctions on China (Kesavan, Reference Kesavan1990). In December, National Security Adviser Brent Scowcroft warned Japan not to resume the yen loans too quickly (Zhao, Reference Zhao, Koppel and Orr1993: 172). In early March 1990, Secretary of State James Baker told Japanese Foreign Minister Taro Nakayama that the US was opposed to lifting the ban on non-humanitarian aid to China, and that it would expect Japan to refrain from resuming the yen loans until Beijing allowed Fang and his family to flee the country (Miyashita, Reference Miyashta2003: 67). In late April, when an LDP member, Toshio Yamaguchi, visited Washington to discuss trade issues, Brent Scowcroft reminded him that Japan should not unilaterally lift its sanctions on China (Miyashita, Reference Miyashta2003: 67). In May, Scowcroft told former Foreign Minister Hiroshi Mitsuzuka that ‘the United States does not want to see the loans to China being restored too quickly’ (Miyashita, Reference Miyashta2003: 62). Facing US pressure, the MOFA concluded that Japan should not unilaterally lift the ban on economic assistance to China.

After December 1989, the US−China relationship gradually ameliorated. On 8–9 December, Brent Scowcroft visited Beijing to pursue improved US−China relations. On 14 December, China announced that it was ready to discuss the Fang Lizhi issue with the US. On 19 December, President Bush announced the lifting of the congressional ban on the Export−Import Bank loans to China (Kesavan, Reference Kesavan1990). On 10 January 1990, the Chinese government declared the termination of martial law, and on 20 January, the government released the prodemocracy demonstrators who were arrested during the 4 June military crackdown (Miyashita, Reference Miyashta2003: 65). On 27 February, the World Bank partially lifted a freeze on the loans to China, although the US Congress remained adamantly opposed to the full resumption of World Bank loans until China dropped charges against Fang Lizhi (Kesavan, Reference Kesavan1990; Miyashita, Reference Miyashta2003: 66). On 25 June 1990, the Chinese government finally allowed Fang Lizhi to leave the country. While the release of Fang did not elicit a full resumption of World Bank loans, President Bush informed Prime Minister Toshiki Kaifu that he would not object to Japan's resumption of the loans to China (Dowd, Reference Dowd1990). Once Bush has given his approval, at the July 1990 G-7 summit in Houston, Prime Minister Kaifu announced that Japan would gradually resume the yen loans to China.

8. Conclusion

In this paper, I explored whether and how the US urges minor powers to disburse aid to achieve its overarching political objectives and how domestic politics of subordinate states affects the degree to which external pressure shapes their aid policies by focusing on the relationship between the US and Japan. This was the first attempt to provide a theoretical framework for the direction of US influence on Japan's aid provision and to explore why its impact varies across different types of aid by focusing on Japan's bureaucratic politics. I employed a new dataset of Japan's ODA and estimated both OLS and 2SLS regressions to handle the issues of reverse causality and joint decision-making. I argued and demonstrated that the US applies pressure on Japan to complement its aid efforts rather than to substitute them as the US attempts to prevent Japan from strengthening ties with the recipients and advancing its own commercial interests. Thus, Japan tends to disburse aid in tandem with the US. However, since Japan's aid policies are determined by bureaucratic agencies, there exist variations in Japan's receptiveness to external pressure. If a bureaucratic agency, which has close ties with foreign representatives but lacks a strong domestic constituency, is in charge of aid allocation, the aid policy is more receptive to US pressure than an aid policy formulated through consultations among multiple agencies including the one with strong domestic support. Accordingly, in Japan, the allocation of grant aid, which is left to the discretion of MOFA, is more receptive to US pressure than that of loans. These two hypotheses were supported by the combined results of quantitative and qualitative analyses.

The results of this study help us understand a longstanding puzzle of why there exists a discrepancy in criticisms of Japan's ODA; while some scholars argued that Japan's aid policy has been vulnerable to gaiatsu (Calder, Reference Calder1988), others asserted that Japan has been seeking its own commercial interests (Schraeder et al., Reference Schraeder, Hook and Taylor1998). This seeming discrepancy in the responsiveness of Japan's aid policy might have stemmed from the fact that most existing quantitative studies on Japan's ODA employed aggregated data and did not investigate the impact of US aid on the allocation of different types of Japan's ODA. Because the share of loans in Japan's ODA varies from year to year, it is not surprising that previous findings are mixed. The outcomes of this study, therefore, suggest the importance of disaggregating ODA especially if donors disburse various types of aid and different domestic actors are in charge of their allocation.

The findings of this paper are further extendable to the literature on aid coordination (or lack thereof).Footnote 42 Recently, a growing number of scholars and policymakers have stressed the importance of aid coordination and encouraged donors to concentrate on fewer recipients as recipients generally lack sufficient administrative skills to absorb aid from multiple channels. For example, Knack and Rahman (Reference Knack and Rahman2007) asserted that donor proliferation causes excessive recruitment of administrators by donor states, which puts further strain on already scare resources (i.e., skilled labor) of recipients. Nevertheless, previous empirical studies generally found that donor proliferation remains more prevalent than aid coordination (e.g., Frot and Santiso, Reference Frot and Santiso2011), although they did not provide us much insight into why coordination fails.Footnote 43 The findings of this research indicate that a superpower's incentives to use aid to attain diplomatic objectives and to prevent minor powers from acting opportunistically also account for coordination failure. Accordingly, if the dominant state could refrain from pressuring others to complement its aid efforts, or if developed countries in general could resist a temptation to inhibit others from specializing in a particular country and strengthening political/economic ties with the recipient, we may observe a more efficient delivery of foreign aid.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this paper can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1468109920000018.

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to Xinyuan Dai, Niheer Dasandi, Christina Davis, Kentaro Fukumoto, Yusaku Horiuchi, Takeshi Iida, Gaku Ito, Minoru Kitahara, Shuhei Kurizaki, Hideki Nakamura, Megumi Naoi, Ryoh Ogawa, Sawa Omori, David M. Potter, Yasuyuki Todo, and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions. I would particularly like to thank Ryosuke Okazawa for his constructive criticism and insightful feedback. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the Modern Economics seminar at Osaka City University on 4 October 2016, the annual meeting of the Japan Association of International Relations on 14 October 2016, the annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association on 7 April 2017, the spring meeting of the Japanese Economic Association on 25 June 2017, the inaugural meeting of the NEWJP on 27 August 2019, and International Political Economy Workshop at Kobe University on 27 September 2019. This research was supported by funding from the 2017 Strategic Research Grant for Young Researchers at Osaka City University and funding from Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Nos. 26245020 and 18H03623). I am responsible for all remaining errors.