1 Introduction

This paper explores how Singapore's highly successful strategy of growing its state investment vehicles and wealth management sector has, at the same time, caused strained relations with both European Union (EU) and the United States of America (US) over financial transparency, and continues to strain its relations with near neighbours, particularly Indonesia. The paper examines the collective impact of the Asian Financial Crisis (AFC 1997–8), the 2001 electronics slump, the events and aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC 2007–9), Euro-zone slump (2008–present), and the rapid rise of China as a global economic player (1990s–present) on Singaporean policymakers as they have sought to actively reinforce Singapore's status as a regional financial centre (through legislative changes and extensive state incentives and investments in both public and private vehicles) and in doing so strained a number of key international relationships. The primary actor amongst the key policymakers to have driven these financial reforms has been Singapore's Prime Minister since August 2004, Lee Hsien Loong. The link between politics and banking and finance has long been established in the island state, with Singapore's and Southeast Asia's largest bank, the Development Bank of Singapore (DBS), being a government entity along with the massive sovereign wealth funds the Government Investment Corporation (GIC) and Temasek Holdings. By the mid-1990s, it was increasingly clear to the Peoples Action Party (PAP) elite that many of the basic banking roles Singapore had built its financial sector success upon throughout the 1960s to 1990s were becoming the realm of other cheaper financial destinations (Shanghai in China and Bangalore in India). Lee, in concert with cabinet colleagues, moved quickly to redirect the nation's financial services towards the niche but highly lucrative activities of individual and trust wealth management (Low, Reference Low and Chong2010: 171). An essential element of the wealth management sector is non-transparency – the full state assurance that private financial affairs shall remain known only to the holder of the account and the specific financial vehicle holding the account. To this end, the Singaporean government has more than lived up to its end of the bargain. It has reinforced privacy laws despite calls from the US and EU that such policies open the door to mass off-shore tax avoidance, the legitimizing of black money, and at worst terrorist financing.

The GFC and Euro-zone meltdown, however, and the resulting large public sector debt and continuing poor economic growth rates in the US and the EU has led their respective legislatures to make significant regulatory moves related to wealth management accountability. Singapore, having suffered its own downturn in 2008–9, initially remained steadfast during 2008–11 to the position that the financial transparency initiatives driven by the US and EU would be an imposition on its sovereign rights. The determined position of the EU, including activist diplomacy by Germany, and the US continued actions against tax evasion in Switzerland and other jurisdiction have seen Singapore's position change significantly over the last three years (2011–14). Singapore has become signatory to a series of agreements, including the May 2014 Automatic Exchange of Information in Tax Matters Agreement, covering the wealth management of citizens from these jurisdictions (OECD, 21 July 2014). One of the immediate and universal criticisms of these agreements has been the lack of commitment to assist developing economies achieve the same effective level of EU–US regulatory structures, and more importantly the active enforcement of such regulations. That Singapore is in effect acquiescing to European and United States demands on tax evasion in the full knowledge that the future growth areas for its wealth management sector, developing and emerging markets, including Indonesia, remain below par regarding regulation and enforcement (in terms of tax evasion, anti-corruption and black economy asset diversion) (Song, Reference Song2014).

Singapore's elite do believe that Singapore is a well governed state and economy. Cabinet members often express the belief that the People's Action Party (PAP) has delivered the world's best governance. The results, they state, are in the gleaming tower blocks in Shenton Way and Marina Bay occupied by global banks and financial services (Goh, Reference Goh2009; Lee, Reference Lee Hsien Loong and Tar How2010). Despite their confidence in internal governance, Singapore's exposure as a city-state to global economic currents is undeniable. The Singapore recession (2008–9) was a direct product of its high exposure to the growth and stability, or otherwise, of global finance and trade. Prime Minister Lee (2010) outlined his analysis of the GFC's impact on Singapore:

Singapore has just gone through two very difficult years. The problems became acute in 2008 when the US and European financial systems nearly collapsed, dragging down real economies worldwide. We were also dragged down, faster than others because we are more open and globalised, and by January 2009, our economy was facing a drastic plunge. Therefore, over the last one year, we have focused on dealing with the downturn, working with employers and unions to save jobs, supporting viable companies with needed financing, and helping Singaporeans to pull through the crises. The year turned out much better than we had feared. This was partly because globally the worst scenarios which we had imagined fortunately did not materialise, and also because the measures we took – the ‘Resilience Package’ – were effective and helped to keep companies afloat, workers in jobs and to keep confidence up and morale high. We are moving ahead again with cautious confidence. . . we need to restructure our economy to maximise our growth, our potential and what we are able to deliver. We need to do this to respond to physical limits. (in Tan, Reference Tan2010: 5–6)

Correspondingly, Singapore's rapid rebound from recession in 2010 (with annual growth at 14.5%) highlighted the intertwined nature of its full engagement with globalization (Basu Das, 2010; Monetary Authority of Singapore, 2011). Singapore's position on individual/trust wealth management and privacy provisions is driven by legitimate concerns that its small size and geographic location means it could find its financial sector left behind by far larger players in Northeast and South Asia. This paper explores Singapore's efforts to benefit from the rapid global expansion of wealth management whilst managing at times strained relationships with key international and regional partners over the regulation of this sector.

2 Globalization in twenty-first century Singapore: success and hurdles

In August 2004, Lee took over the prime ministership in a long-term and well-orchestrated transition of power from Goh Chok Tong, who had been in office since 1990 (Welsh et al. (eds.), 2009). Lee came to office with high credentials. He had served in primary finance and the planning of cabinet portfolios for over a decade, including having served as head of the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS, 1998–2004) and finance minister (2001–7) throughout the AFC (1997–8) and the 2001 electronic-sector derived recessions. He designed and executed the restructuring of Singapore's financial sector following the 1997 crisis with two fundamental aims: firstly, to enhance the centrality of state capacity in overseeing the financial sector; secondly, to fully internationalize an already highly internationalized banking sector within regulatory structures focused on the quality of sector participants. The central strategic policy being that Singapore should aim to move ahead of its regional rivals (Hong Kong, Sydney, Shanghai, and Dubai). In efforts to achieve this, the Singapore Stock Exchange (SGX) changed regulations to enable innovation and technology stocks to be more easily listed, and government leaders travelled extensively to reaffirm the nation's political stability and good governance (including the financial security and secrecy of high-wealth individual/trust Singapore-held assets).

By end-2010, Singapore hosted 7,000 multinational companies (MNCs) from the US, Japan, and Europe, 1,500 from China, and a further 1,500 from India, all attracted to Singapore in the knowledge that capital expertise and required credit would be accessible (US State Department, 21 May 2011). Numerous key business surveys rank Singapore at the highest level for legal, political, and economic stability, the ease of doing business, financial flow, business centre characteristics, knowledge creation and information flow, competitive regulation, low tax and strict secrecy – all seen as highly desirable to hedge funds, banks, and the property sector. The opening of Integrated Hotels and Resorts (Marina Sands Resort and Sentosa Resort casinos) and the introduction of Formula One racing (first held in September 2008) have all been directed at attracting and retaining wealthy individuals/trusts/enterprises to the island state (da Cunha, Reference da Cunha2010).

Yet, despite these significant successes, the international ground has been moving unfavourably for Singapore with China's emergence as a global manufacturing and supply chain powerhouse and India's rise in international services (banking, telecommunication, and information management) placing the city-state with the challenge of operating within these highly competitive international sectors. As a result, Singapore's substantive state-backed funds (namely the GIC, Temasek Holding, and others) and human capital have been actively expanded by the government to rapidly advance the nation's capacity to attract the international wealth management players (both the bankers and the high-wealth individuals they service) deemed essential to Singapore's future prosperity (Grigg, 2014; Robins, Reference Robins2014; Grant, Reference Grigg2014).

3 Singapore as a wealth management centre: governance and regulatory environment

Singapore has been highly successful in attracting international financial sector enterprises. The massive Swiss-based giant UBS being but one example of an international wealth management actor who has been actively courted by the Singapore government elite (the GIC as the owner of 6.4% of UBS shares is one of the largest shareholders), and now making the island a global centre for various wealth-generating operations. Despite this highly visible success (UBS is a key sponsor of Singapore's F1 Grand Prix), the sheer scale of international banking and finance means that Singapore must be selective in its activities. It has focused on providing niche, but highly profitable, services, most notably wealth management services. Those financial services aimed at wealthy individuals or trusts, have been particularly targeted as providing the island state with a competitive edge. Along with traditional Western markets, Singapore is successful in gaining market share within the new wealth management markets of China, Russia, Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East. One clear example being the May 2007 opening of Singapore first Islamic Bank, the Islamic Bank of Asia (IB Asia), as a subsidiary of DBS Bank. The aim is clear, to tap into the bourgeoning Middle Eastern wealth management and investment market (Vernardos, Reference Vernardos2010). Having concluded that the GFC-type instability will remain a feature of the international financial landscape for some time, the Singapore government moved swiftly through the MAS to ensure the city's highly regarded reputation and regulatory credentials remained firmly fixed within the minds of these wealthy individuals/enterprises through the active legislative enactment and enforcement of Basel III (Lee, Reference Lee Hsien Loong and Tar How2010; MAS, 2011).

Traditionally, high levels of secrecy regulation have been the central requirement for any location, be it Switzerland or Monaco, to thrive as an international wealth management centre (Logutenkova, Reference Logutenkova2012). For Singapore this was absolutely no hurdle. The PAP itself has consistently maintained that governing the island economy through state investment corporations and government-linked companies (GIC, Temasek Holding) requires limiting transparency. Lee Yuan Yew has made it clear on numerous occasions that he sees non-transparency as essential to Singapore's continued governance and long-term prosperity:

we are managing over $US100 billion. The assets have steadily increased in value over the years. The returns are adequate. We are a special investment fund. The ultimate shareholders are the electorate. It is not in the people's interest and the nation's interests to detail our assets and their yearly returns. The accounts of GIC are checked by the Accountant-General, Auditor-General and examined by the Council of Presidential. There is total accountability. (Ho, Reference Ho and Ho2005: 273–5)

The secrecy of the GIC, Temasek Holdings and other government-linked investment vehicles means a complete independent picture remains beyond reach. This policy position will not change any time soon, as PM Lee as chairman of the GIC has reaffirmed its centrality (Lee, Reference Lee Hsien Loong and Tar How2010). Beyond the transfer from father to son, the non-transparency doctrine is a fundamental ideological tenant on the PAP's governance legitimacy.

Nevertheless, it is a position now being challenged by the GFC-derived immediate paper and realized losses of the government investment vehicles in US and European banking, financial services and property markets which has led to some of the harshest sustained criticism that the PAP governing elite has faced during its four decades-plus of government (Crispin, Reference Crispin2009; ABC, 2009; Giam, Reference Giam2010). The PAP in turn has made it clear that there is, seemingly, no middle ground. That it will not sacrifice the GIC and other state investment vehicles secrecy through choice. In turn, the critics refuse to be silenced, and one early critic in particular, Gerald Giam (Reference Giam2010), now finds himself as a nominated member of the Parliament of Singapore. To-date shareholder activist attempts to have Singapore's large enterprises open their books to more than restricted external review continue to be stonewalled. For example Singaporeans only got to know the full extent of Temasek's US-based GFC losses through the US Securities and Exchange Commission. The Singapore government and the company itself was a study in silence.

Aligned to the PAP, adherence to non-transparency is the consistent and vigorous defense by the leadership of their often-stated position that Singapore is a centre of excellence in corporate governance (Anandarajah, Reference Anandarajah and Leong2005: 246). Then-Minister Mentor, and former Prime Minister, Goh Chok Tong (2009), has stated:

Moreover, the ever greater emphasis on building trust, good governance and competence plays to Singapore's advantage. We are ranked first in corporate governance standards in Asia by the World Economic Forum, and we have maintained a stable ‘AAA’ sovereign rating from Fitch. The City of London's Global Financial Centre Index ranked Singapore the most competitive financial centre in Asia, and third globally, after London and New York. However, it is important not to be complacent as trust, good governance and our reputation for competence require continuous reinforcement as standards change and new demands arise . . . We have a reputation for a sound regulatory regime and a trusted legal and governance framework.

This PAP vocal proclamation of high-corporate governance standards is hardly surprising given that the continued presence of the vast sums of individual/trust/enterprise wealth are dependent upon the city maintaining the highest levels of banking and finance management and regulation. Any serious questioning of Singapore's corporate governance would see these wealthy entities promptly repatriate their funds home or to a third destination (for details of Singapore's corporate governance legislation, see Anandarajah, Reference Anandarajah and Leong2005). The government has consistently actively moved to protect its governance reputation through legislation. The Prevention of Money Laundering Act of 2002, which legally compels financial institutions to report suspicious transactions, was introduced to rebuff accusations that Singapore is insufficiently proactive in curtailing non-legitimate wealth entering the country (The Economist, 2011c). However, Section 47 of the Singapore Banking Act is titled, ‘Secrecy’, and makes it abundantly clear that banking client's information ‘shall not, in any way, be disclosed by a bank in Singapore’. In a speech to parliament in 2001, then finance minister and drafter of the Banking Act, current Prime Minister Lee, made clear that this secrecy act would be enforced vigorously, with any secrecy breach deemed a criminal offence. Lee was not reinventing the wheel in such an approach, but was in complete step with Switzerland, whose secrecy laws remain vigorous to this day and prompting a senior US investigator in 2014 to state: ‘It is tough to get through the Swiss secrecy law’ (Letzing and Zibel, Reference Letzing and Zibel2014; Saunders and Letzing Reference Saunders and Letzing2014). The Secrecy provisions in the Banking Act, critics argued at the time, effectively meant banks have no rational reason to ask difficult questions of the Asian and international rich clients as to the validity of the origin of the money being invested. Increasing from $US92billion in 1998, to $US350 billion in 2007 and $US500 billion by end-2008, Singapore's wealth management sectors growth was deemed central to national prosperity, and the PAP government had no intention of hindering its continuing expansion (Ball, Reference Ball2009; Studwell, Reference Studwell2008).

In October 2009, the PAP government passed a bill through parliament amending the income tax law to comply more in line (but not fully) with Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) standards to fight cross-border tax evasion, allowing the Singapore government to ask banks for client information in potential cases of foreign tax evasion. This move by the Singapore government, however, did not see the island state removed from the OECD's grey list of countries deemed uncooperative, and as this paper will show, how it led directly to an escalation of European diplomatic pressure (Reuters, 2009). Despite this, the PAP government insisted at the time it had done enough.

4 Switzerland's loss, Singapore's gain?

There can be no doubt that Singapore's ultimate aim is to challenge Switzerland as the home of private wealth management. It has made such intent well-known through continuous reforms and promotional campaigns throughout Europe, North America, the Middle East, China, Russia, and other emerging markets. The message is uniform: that high wealth individuals/trusts will find Singapore a welcoming nation with a supporting regulatory and tax climate, including the vigorous enforcement of the strict privacy laws. Whilst the objective of overtaking Switzerland in wealth management might have seemed fanciful even five years ago, tectonic regulatory shifts in Europe and the US are altering the equation. The EU and the US have been effective in placing pressure upon Switzerland to comply with new transparency arrangements throughout Europe (Saunders and Letzing, Reference Saunders and Letzing2013). In 2005, Switzerland was forced under EU threats to restrict the nation's trade with wider Europe to comply with EU demands for a 15% withholding tax on all EU citizens. This has now risen to 35%. The US has also moved on Switzerland, with UBS being forced in 2009 to pay a $US780 million dollar fine to the US in return for not being prosecuted in American courts and between 2009 and 2014 to reveal the names and details of 4450 rich American citizen's suspected of tax evasion. A further 38,000 American citizens, in recognition that the Swiss banks could no longer protect their identities, have taken part in a partial amnesty program. Revealing their hidden wealth in Switzerland, they have paid a staggering $US5.5 billion in taxes up to end-2013, with a further $US5billion still to be paid. Other Swiss banks have been forced to concede and either enter bankruptcy, with century-old Wegelin being the most notable, or, like Credit Suisse, set aside hundreds of millions in order to settle fines to US regulatory bodies. The US regulatory authorities hardly needed to point out that they carried a very big stick: possessing as they do the ability to suspend UBS operations in the US, which account for 37% of its employees, and to declare Switzerland as a black list tax haven. Such a declaration would by law require all US companies to exit the nation and terminate the 70,000 employees they have in Switzerland. In 2014 Switzerland has a raft of newly minted and updated tax treaties with the US, France, Germany, and other countries: a total of 18 tax treaties in all, all aimed at ending the tax evasion excesses of the past (Logutenkova, Reference Logutenkova2012; Shotter, Reference Shotter2013; Letzing and Zibel, Reference Letzing and Zibel2014).

The lessons for Singapore in these substantive changes to Switzerland banking and finance are apparent, as Saltmarsh (Reference Saltmarsh2010) makes clear:

The switch was not Switzerland's idea. Its neighbours, painfully aware of the tax receipts they were losing, have been increasing the pressure for years. But it was not until the US government threatened UBS, the biggest Swiss bank, with criminal prosecution about a year ago [2009] that the wall really began to crumble . . . an end to absolute banking secrecy will change the country's pre-eminent financial sector . . . Niche private banks that previously specialized in undeclared assets in Geneva and Zurich will have to adapt, and some may fail, analysts and academic predict. Those that remain will have fewer assets to manage.

The outcome of these EU–US imposed tax evasion regulations and treaties has been a relative decline in new wealth management assets held by Swiss banks, severe staff retrenchments across the financial sector, and question marks over the continued growth of a sector that still accounts for a massive $US2.99 trillion in assets as of end-2012 (Grant, Reference Grigg2014).

The benefits Singapore has gained over the last decade as a result of the EU and the US moves against Switzerland's wealth management sector have been significant to say the least as an unnamed private banker makes plain: ‘Prior to that, our Singapore desk in Europe was booking millions of dollars – now its billions’ (Australian Financial Review, 2009, various). In a January 2008, speech Prime Minister Lee made it clear that Singapore wealth management system was part of the PAP's long-term ‘survivalist’ doctrine:

As the prosperity of China and India grows, we are anxious that we do not get lost among the Asian superpowers . . . Hong Kong is preoccupied with China, while we are more omni-directional in our approach. (Kleinman, Reference Kleinman2008)

For the PAP leadership, wealth management is not just a financial and economic affair but more importantly a sovereign one. If the island-state allows the global economic giants, the EU and the US, today to impose limits on Singapore's sovereignty and prosperity, tomorrow it could be China, India, Indonesia, or another who would seek to impose their will.

The Singapore government has continued its systematic introduction of legislation and state support systems targeted at attracting international wealth management institutions and investors. The Economist 2011a) outlines these moves:

To retain those [book] assets, Singapore produced a legal framework enabling trust accounts, once the preserve of Jersey and Bermuda. This was despite the fact that Singapore itself does not tax estates and Singaporeans have no need of the service. Good trust laws combined with strong asset-management and foreign-exchange capabilities make Singapore appealing for wealth-management types everywhere.

Singapore's approach is the antitheses to laissez-faire. Broadly speaking, it has kept a tight rein on domestic finance and done what it could to induce international firms to come. Licenses can be obtained efficiently and quickly, a blessing in a bureaucratic world. So can visas for key employees. There are tax breaks for firms considered important, as well as reimbursements for relocation expenses.

For the wealth management clients, there would be: no withholding tax: no capital gains tax: no tax on interest and investment earnings, and no stamp duty. Former Prime Minister, then Minister Mentor, Goh Chok Tong (2009) made plain the success of these measures:

Prior to the [GF] crisis, the asset management industry in Singapore had flourished, with growth averaging 20% per annum over the last 7 years [2002–8]. It has grown in diversity to include not just global traditional fund managers but also alternative investment managers. Most of the fund management firms here are from Japan, Europe and the US, reflecting the international character of our asset management industry.

UBS, the world largest private bank, and the primary target of the EU–US highly effective anti-tax haven campaign in Switzerland, now has its second largest office and its Asian regional hub in Singapore. Further, it has established a new academy for private wealth management located on the prestigious Command House colonial estate. Key competitor and active wealth management institution, Citigroup Singapore, now has 9,400 workers within its Singapore operations and continues to expand to fulfill commercial requirements. Standard Charter now calls Singapore home to its global headquarters. Credit Suisse has also moved its head of international banking to the city. In all, private foreign banks operating in the wealth management sector now number approximately fifty. Prior to the GFC, such was the demand from private banks to gain/or increase their presence in Singapore corporate office space, prices matched those of New York and Zurich, and often exceeded them. The current development of the massive Marina Bay Financial Centre is a testament to the success of the government's actions. Further, the PAP government has enabled the active importation of foreign talent through a favourable skilled visa/migration scheme, and financed the rapid expansion of domestic wealth management talent through tertiary institutions and centres (AXA University Asia Pacific Campus (April 2009), SMU-Sim Kee Boon Institute for Financial Economics, SMU-BNP Paribas Hedge Fund Centre, INSEAD Asia Pacific Institute of Finance and the National University of Singapore-Risk Management Institute (NUS-RMI).

The door to the city has been opened with any wealth management client with $S20 million able to gain permanent residency immediately if they place $S5 million into a Singapore-based account. UBS alone acknowledges signing more than 100 supporting letters for permanent residency which translates into a minimum investment of $500 million into Singapore based accounts (Australian Financial Review, 2009, various). With 50-plus private banks operating on the island, it is not difficult to determine that the ‘residency’ investment system reaches into the multiple-billions of dollars range placed with these institutions. Middle Eastern investors, post-11 September 2001 terrorist attacks and the resulting tighter US banking laws over the last decade, are also moving assets into Singapore. As stated this prompted the DBS to set up an internal Islamic Bank to accommodate such needs. They have been equally matched by Russian counterparts who, following the 1990s–2000s privatizations of national oil and gas reserves into selected hands, have placed an estimated $US300 plus billion dollars of assets into Singapore over the last decade (Banking and Payments Asia, 6 April 2009). The Economist (2011b) makes clear the impact of these new wealth sources: ‘The scale of the transformation has been enough to propel Singapore into the ranks of the world's leading financial centres’, and by end 2012 assets under management increased 22% from the previous year to $S1.63 trillion (or $US1.29 trillion) (Grant, Reference Grant2013).

5 The price of success: the growing regulatory reach of the United States of America and the European Union

As recently as 2010, PM Lee Hsien Loong has stated: ‘We need some discipline to bind all countries to multilateral impartial rules. We're doing better than before, but no country completely gives up its sovereignty’ (in Liow, Reference Liow and Chong2010: 29). Up until recent times, Switzerland's political and financial leadership stated the same. The breaking down of Switzerland's tax haven status from the onset of the GFC (2007) onwards, however, has shown that when two of the world's large economic actors, the US and the EU, act in concert to impose their economic will, few can resist. As former Prime Minister Goh highlighted above, both are major investors across key value-added areas of Singapore's financial and manufacturing landscape. At end-2012, total accumulated assets of US investment in manufacturing and service sector in Singapore was $US85.99 billion, with approximately 1500 US firms operating in Singapore, whilst Singapore has $US 22 billion invested in America (US Department of State, 2014).

EU member nations, most notably France and Germany, squeezed by the GFC and the looming Euro-zone crisis, began to focus on their tax base, including regulatory moves to gain greater access to information on the real wealth base of their citizens. Whilst Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and Monaco were immediate targets, from 2009 Singapore, because of its very success in attracting funds, increasingly came under the regulatory glare as Europe's financial and economic woes deepened. Despite protestations from the PAP that Singapore's corporate governance was excellent, Glyn Ford, a British Member of the European Parliament, made it clear that Singapore was under European scrutiny:

If I wanted somewhere to launder money, Singapore would be getting towards the top of my list. . . Where there are dark corners of the financial world, dirty money tends to end up. (Australian Financial Review, 2009, various)

Economic diplomatic pressure on Singapore directly from the EU and member states would only intensify over 2009 to 2011 as the Euro zones economic plight deepened. On 2 June 2011, in a joint media conference with German Chancellor Angela Merkel during her visit to the island-state, Prime Minister Lee was asked by German journalists about EU concerns over Singapore's transparency regime. He replied:

The Republic is a cooperating financial centre that maintains high standards of transparency and integrity, oversight of funds flows and takes action against suspicious and improper transactions . . . We cooperate with other jurisdictions in doing that, and there is a framework for doing that between regulators which we participate in. It's important that this be fair and objective, and that Singapore is able to play a constructive role in this overall global system. (Times Business Directory of Singapore, 2011).

Merkel chose to weigh in stating that during the meeting, PM Lee recognized the importance of transparency to Asia and that:

(It is in our) common interest to have a joint approach to financial market regulation. We want to avoid (having) places in the world were regulation was less stringent and would therefore prove very attractive to the financial sector or business. (Times Business Directory of Singapore, 2011)

There was no hiding the fact that Germany had now made greater financial transparency and tax avoidance a priority of the EU-Singapore relationship (BBC, 2012, Merkel, Reference Merkel2011a, Merkel Reference Merkel2011b). The German journalist, as is standard for international visits by heads of state, had clearly been briefed by Merkel's advisors that the agenda would focus largely on this grey area of international banking and finance. Further, Merkel's own response would have been analyzed and vetted numerous times by her and her key staff prior to delivery. In fact, Merkels's policy push was part of the European Savings Tax Directive, which maintains a tax regime (just as the US does) that obliges EU citizens to pay taxes on earnings worldwide wherever it is generated, and with the regulatory gaze very much fixed on Singapore. Having forced Switzerland into greater compliance throughout 2008–12, Singapore's very success at attracting large-scale individual/trust assets has ensured that the EU and the US economic regulators have come to focus on the validity of such accumulation. As Singapore has found, moving from the regional to the global in wealth management and as a financial actor comes with very different expectations from key global economic heavyweights.

That evening (of 2 June 2011), to emphasize the point that Germany (and by extension the EU) had a significant role to play in the Singaporean economy, Merkel as the invited deliverer of the annual address of the influential Institute of Southeast Asian Studies government think-tank stated plainly: ‘More than 1,200 German companies are active in Singapore. German investment here amounts to more than eight million euro. Some 7,000 Germans live in your country, including more than 200 scientists who value Singapore as an extremely attractive research location.’ Merkel, as her audience knew full well, spoke with the authority of a shared Germany–EU–US position since the Merkel (2005–present) and Obama (2009–present) administrations had collectively imposed their will on Switzerland with a singular concerted purpose. In October 2012, Singapore and Germany announced a comprehensive deal to tackle tax evasion by German citizens (which the rest of the EU quickly sought to impose) (BBC, 15 October 2012). The US Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) of 2013 introduced even further strict compliance measures in relation to the overseas wealth of its citizens. One analyst (Drummond, Reference Drummond2011) defines the measures as such:

[The FATCA] will effectively turn banks outside America into collectors for the Internal Revenue Service . . . There is a strong push within the US to do whatever is needed to reduce tax evasion . . . [in the identification of customers with US tax liabilities] the onus to investigate lies with the banks themselves . . . Should banks refuse to co-operate, they themselves will be punished with a 30 percent withholding tax on any revenue they earn in the US. In effect compliance is the only option. The law is aimed at stamping out the practice of US citizens using foreign-domiciled corporations or foreign banks to hide income from tax authorities . . . And there is no chance of some countries being carved out. Such a move would raise political issues for the US government.

In direct response to this EU–US regulatory activism throughout 2009 to 2014, Singapore has systematically ‘rolled out a series of measures aimed at reducing tax evasion activities within its jurisdiction’, including the previously mentioned enhanced commitments to the automatic exchange of bank data (Guo and Woo, Reference Guo and Woo2013). As a result, Singapore's wealth management institutions, directed by Singaporean regulatory authorities, will in the future be highly selective in accepting business from US and EU high-wealth individuals (Song, Reference Song2014).

This may, or may not, have a dampening effect on the net growth trajectory of Singapore's wealth management sector, as the individual wealth of the US and Europe is still the largest globally, a fact that Singapore has accepted. Singapore-based wealth managers are already directing new energies on high wealth individuals/trusts from emerging economies, whose governments show little to no interest in bringing transparency and taxation regulatory pressure to bear. The rise of China, Russia, India, the Middle East, and Indonesia with their rapidly expanding wealth management needs means that the cost of the new US–EU regulatory regimes will more than likely be handsomely offset by Singapore's active pursuit of these new wealth drivers. As the next section shows, whilst attracting and managing such ‘emerging’ wealth has obvious benefits to Singapore's domestic prosperity, it in fact comes with a substantive reputational and regional relationship risk profile.

6 Regional implications of being a wealth management centre

The rapid expansion of Singapore's wealth management services, including strengthening the privacy laws, whilst introducing tensions with US and EU regulators, has had an even greater detrimental effect on the bilateral relationship between Singapore and its ASEAN partner and regional giant, Indonesia. This author does not overplay the extent of the tensions derived from this area of dispute between the two nations, and is in full agreement with Hamilton-Hart (Reference Hamilton-Hart, Ganesan and Amer2010: 200) that as a whole bilateral relations are defined by the ‘large areas of complementarity and cooperation that exists’. This author also concurs with Hamilton-Hart's analysis that such disputes have a long history based on the very different structures of the two economies, with Singapore's port-trade commercial orientation contrasting starkly with Indonesia's large hinterland economy centred on agricultural and resource extractions, and providing ample room for areas of contestation to arise (Hamilton-Hart, Reference Hamilton-Hart, Ganesan and Amer2010). What is new to the relationship, however, is dramatic changes over the last decade within Indonesia's political space, including a free, open, and highly vocal media. The 2014 presidential election of Joko Widodo (Jokowi), a political figure who has built a political-based centred on establishing better governance standards, including a high-profile anti-corruption stance, best encapsulates this changing Indonesian political landscape (The Conversation Australia, 2014, various). Singapore can hardly expect that the new President's governance and anti-corruption reform agenda to end at Indonesia's border, and can only expect further questioning over how national/regional public funds continue to end up in Singapore-held accounts. In fact, the PAP's domestic political opponents are already asking this very question.

The questions surrounding Singapore's role as a harbour for ill-gotten Indonesian wealth are hardly new, but in the post-Suharto era have taken on a new dynamic. Back in 1999, the then Indonesian President, B.J. Habibie, accused Singapore of harbouring ‘economic criminals’ as the sheer scale of graft surrounding Indonesia's mis/management of Asian financial crisis banking and corporate bail-outs emerged. It was during this time that Habibie, completely frustrated by Singapore's role as a refuge for Indonesian wealthy exiles, made his famous derogative comment that the island nation was nothing but a ‘little red dot’ on the map. Whilst not all of Indonesia's super-rich residing in Singapore are the beneficiaries of ill-gotten gains, a significant number of high-profile wealthy individual and family conglomerates are (refer to Table 1). In 2006, according to a wealth report titled Asia-Pacific Wealth Report by Merrill Lynch and Capgemini, ‘around one-third of the 55,000 millionaires who lived in Singapore at that time were Indonesian, with assets totalling a staggering $87 billion’ (The Economist, 2011b). The next year, in February 2007, the Jakarta Post claimed 18,000 super-rich Indonesian were residing in Singapore (Sasdi, 26 February 2007). As a result, Indonesians are now the island states largest purchasing group of premium Singapore real estate and significant consumers of everything from luxury goods, to medical services, to international schooling (The Economist, 2011c). A leaked email from the then chief economist of Morgan Stanley, Andy Xie, after a regional IMF conference held in September 2006, states as much:

People at the meeting were competing with each other to praise Singapore as the success story of globalization . . . Actually, Singapore's success came mostly from being the money laundering centre for corrupt Indonesian businessmen and government officials . . . To sustain its economy, Singapore is building casinos to attract corrupt money from China.

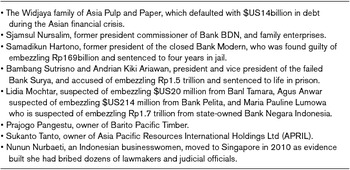

Table 1. Indonesia's super-rich and wanted residing in, or believed to be residing in, Singapore

Notes: The US does not have an extradition treaty with Indonesia but co-operation by US officials saw the fugitive Indonesian David Nusa Wijaya, wanted in connection with embezzlement of about US$140 million, return to Indonesia from San Francisco earlier in 2006. The US Indonesian Embassy released a statement: ‘The US Government understands that returning fugitives and stolen assets from abroad in corruption cases is a top law-enforcement priority in Indonesia.’ The implied message being that ‘others’ do not.

Fugitive Indonesian banker, Hendra Rahardja, who embezzled $US300 million, was about to be extradited from Australia to Indonesia in early 2003 when he died of cancer in Sydney. His funds were frozen in Australia before being returned to Indonesia.

A 2006 case in which a Swiss bank co-operated with the Indonesian Government in tracking down $US5.2 million in allegedly improper funds deposited by the former head of Bank Mandiri, Indonesian largest state-owned bank. Those funds were returned to the Indonesian government.

Knowing full well that such a public position was untenable for Morgan Stanley's Singapore operations, Xie resigned immediately. Significantly he did not retract the comments (Studwell, Reference Studwell2008: 35). Xie was not alone in holding this view. In a 2006 interview with Backman (Reference Backman2006), an unnamed senior regional fund manager stated:

Singapore has truly become the global centre for parking ill-gotten gains. The private banking teams are huge and in practice almost ask no questions (compared with branches elsewhere, including Switzerland).

An acquaintance of mine who made $US13 million through a corrupt deal (in Indonesia) was not asked about how he got the money despite obviously having a job that would not have allowed such amounts to have been accumulated. Russians, mainland Chinese and Indonesians are pouring money into Singapore. High-end property has risen 30–50 percent in the last 18 months or so.

Simmering frustration within Indonesia over the presence in Singapore of the super-rich exiles sought by the Indonesian judiciary boiled over again in February 2007. Indonesia announced a complete ban on the exportation of sand, vital to Singapore's construction industry, to the island state, and senior officials made no secret of linking it to the failure of Singapore to sign an extradition treaty. Indonesia's then vice-president, Jusuf Kalla (2004–9, 2014–), in a media interview, pointing to the billions in alleged ill-gotten gains held in Singaporean accounts by fugitive Indonesians. In an attempt to resolve tensions, and ongoing defense relations issues, the two countries launched immediate rounds of vigorous diplomacy and in April 2007 signed a joint extradition-and-defense agreement (the Extradition Treaty and Defense Cooperation Agreement). The Indonesian House of Representatives, however, has refused to ratify the Treaty over concerns relating to the defense component (Purba, 7 July 2011). The Singapore government has also consistently responded that verifiable evidence must be supplied by the Indonesian authorities as Singapore regulators or bankers are not quasi-investigators. This is in fact a perfectly technically correct response from the Singapore government as it corresponds with the OECD's policies in relation to countering offshore tax evasion and money laundering. Not surprisingly, it has not appeased Indonesian critics (OECD, 23 September 2009).

The failure of both countries to resolve the divisive issue in a timely manner means it has found critical voices on both sides. Current political opposition figures in Singapore, Kenneth Jeyaretnam and Gerald Giam being the most vocal, openly concur with the position that Singapore has done very well out of providing Indonesia's super-rich unfettered access to its wealth management sector, but has done far too little in holding to account those who have obtained it illegally (Giam, Reference Giam2010; Song, Reference Song2014). Giam (Reference Giam2010) takes the Singapore government to task:

The government previously claimed that there is no need for an extradition treaty, because Singapore banks already have stringent checks in place to ensure that the Republic is not used as a money laundering centre. If this is the case, then the government should have no worries that the Extradition Treaty will impact the money parked in local banks. If it turns out to be the case, then it's high time our banks put their house in order . . .

The Treaty will also remove the main bugbear in bilateral relations with our largest and most important neighbour, and open doors for further cooperation in a myriad of areas . . . Indonesia is Singapore's second-largest trading partner and Singapore is one of Indonesia's biggest foreign investors. A growing Indonesian economy would be a boon for not only our exporters and investors, but our service industry as well. It is certainly not a ‘zero sum game’, as many in our government often see it. Lower corruption means more efficient running of business and less ‘overheads’ that need to be paid out to get things done.

Of equal validity The Economist (2011b) did not miss Indonesia's own failings:

Some critics have charged that lawmakers blocked the extradition treaty so Singapore could remain a safe haven for the sort of Indonesian corruptions suspects who donate to their campaigns – or even a refugee for themselves . . . Other disturbing questions remain: why do high-profile corruption suspects always seem to be able to slip out of Indonesia, just before a travel ban is issued. And why don't the Indonesian government and parliament make the extradition treaty a national priority.

The level and extent of Indonesia's systemic corruption problems, particularly in relation to the judiciary, have been well documented by others and is beyond the scope of this study. Equally well documented is the ‘strategic centrality’ of Indonesia to Singapore's future prosperity and security which is openly acknowledged by Singapore government officials and academics alike. Anything other than harmonious relations with Indonesia can rightly be determined as detrimental to Singapore's own long-term strategic and economic well-being (Smith, Reference Smith1999,Footnote 1 2000, Koh and Chang, Reference Koh and Lin2005, Liow, Reference Liow and Chong2010: 33). The Singapore elite's self-proclaimed adherence to pragmatism does inform them that their island nation needs Indonesia's good will more than the reverse. That said, even Singapore's harshest critics acknowledge that any attempt to repatriate fugitive Indonesians and/or their wealth would lead to a mass exodus to a third accommodating country. The result being significant losses to Singapore's wealth management funds with no net gain to Indonesia (Giam, Reference Giam2010: 359). The Singapore government has in recent times (July 2014) shown a willingness to take immediate ‘meaningful’ measures to assist Indonesia to fight corrupt practices, including agreement to withdraw the $S10,000 bill from circulation after it was found to be the exchange-of-choice in several high-profile cases. Yet even here there is dispute with Singapore's plans to withdraw the bill over time being met with the insistence of Indonesian lawmakers that immediate withdrawal is required (ChannelNewsAsia, 7 July 2014). Such antagonism merely highlights the level of frustration amongst some Indonesian lawmakers as further meaningful actions beyond this limited measure requested by them has continued, in their view, to be stonewalled by the Singapore government.

For Singapore, submitting to the Indonesian parliaments stated desire to repatriate funds and persons-of-interest would set an unwanted precedent. Beyond Indonesia, super-rich from throughout ASEAN, China, India, Russia, the Middle East, and Africa all have significant assets in Singaporean-based financial institutions. With US–EU citizens now firmly under the taxation gaze of their respective regulatory authorities, the Singapore government has not surprisingly concluded that substantive further growth rests with these emerging markets. Singapore, therefore, continues to show not even the slightest inclination of risking the continued presence of these high-wealth individuals/trusts through appeasing Indonesia's extradition requests. It will do nothing to risk this high growth ‘emerging market’ sector within the wealth management portfolio of the national economy.

This status quo position, however, is not without substantive risk in itself. Singapore has been fortunate over the last decade to have a moderate President Susilo Bambang Yudoyono (2004–14) as Indonesia's leader and now faces the equally moderate President Jokowi for the next five years (2014–19) at least. As a political figure, Jokowi has shown that his preference is to reconcile differences, build consensus, and to take a decidedly non-confrontational approach. Singapore might never find a better Indonesian leader with whom to resolve this area of long-standing differences between the two nations. The election of President Jokowi to the highest office in the land, the first with no immediate ties to Suharto's New Order regime, and one with an openly anti-corrupt governance stance, clearly reflects the aspirations of most Indonesians for clean governance and accountability. Such aspirations clearly do not end at Indonesia's borders. Ganesan's (2005) statement: ‘Strategically, Indonesia is certainly far too important for Singapore to ignore’: means that the current status quo for Singapore is in fact not a sustainable one, and that, if grasped, the next five years under a reformist Indonesian president might afford the Singapore leadership the best opportunity to finally resolve, to its long-term strategic benefit, the vexed question of Indonesian wealth on the island state.

7 Conclusion

Singapore's state-derived development as a wealth management sector is driven by deep concerns amongst the PAP elite over Singapore's future prosperity. Having overseen the national economy through three significant economic downturns (1997–8, 2001, 2008–9) in little more than a decade-and-a-half, the PAP leadership has been determined to develop new channels of economic growth (Choy, Reference Choy and Chong2010; da Cunda, Reference da Cunha2010). Wealth management is part of a broader national economic strategy that includes bio-technology, advanced manufactures, design, advanced financial–medical–education services, integrated resorts and casinos, which collectively are seen to be anchoring Singapore's future success at home and abroad. However, the GFC and the resulting policy activity by the EU and the US on tax evasion by their citizens have raised a raft of policy challenges for Singapore. The two economic superpowers now place Singapore alongside Switzerland as worthy of regulatory oversight because of its dramatic expansion as a wealth management hub. Singapore's national leadership has strongly expressed the view that Singapore will embrace the post-GFC US and European regulatory regimes covering citizens of those jurisdictions, with managing chairman of the MAS Ravi Menon stating: ‘Our message to tax criminals is loud and clear; their money is not welcome in Singapore. And our message to our financial institutions is also loud and clear: If you suspect the money is not clean, don't take it’ (Song, Reference Song2014). Singapore, however, will continue to benefit from the rapid expansion of wealth outside of the Europe and America, with its position in Asia and reputation for high quality banking and financial services governance positioning it as the preferred site for wealthy emerging market individual/trusts from China, India, and greater Asia. For these individuals/trusts, the PAP's positions on secrecy laws surrounding the wealth management sector is highly attractive. This author can envisage only limited circumstances in which Singapore under the PAP would reduce such secrecy. A number of scenarios exist and none would be undertaken by choice:

1. A loss of significant domestic political support. The political opposition in the recent elections (2011, 2013) gained significant traction in asking how the PAP's courting of high wealth (mainly foreign) individuals fit into its claim of leading a communitarian society. Like all other political parties, the PAP's first priority is to stay in power. Ultimately, foreign bankers and foreign high-wealth individuals do not vote.

2. Like Switzerland, external forces such as the EU, the US, and others act in concert to put in place even further sanctions against Singapore-based banks and financial institutions they see as acting as tax havens or facilitators of ill-gotten gains. The GFC has hardened the resolve of US and EU jurisdictions to clamping down on what they see as illegitimate practices within the international financial system. The US and EU collectively remain the largest value-added investors on the island-nation, so their concerns cannot easily be dismissed by any current or future Singapore government.

3. Indonesia, the current democratic and economic giant in the region has elected a president (Jokowi) known as be Mr Clean. Clearly, the national polity expects better anti-corruption measures and overall sounder governance from their politicians. All positive future scenarios from a Singaporean perspective rely on Indonesia politicians confining anticorruption measures to within its borders. Is this really a sound basis upon which to build future Singaporean–Indonesian bilateral relations?

The PAP's continuing assertion that national economic sovereignty will never be compromised by external forces belies the fact they its economy is highly externalized. The PAP elite themselves regularly acknowledge that it is one of the most globalised economies in the world (Lee, Reference Lee Hsien Loong and Tar How2010). Switzerland had long stated a sovereignty position which it claimed would buffet it from international pressures to open up its financial system but this crumbled in the face of post-GFC penalties and sanction from very proactive US and EU regulators. Europe and the US have shown through Switzerland that they will treat all wealth management centres, Singapore included, along the very same lines if their wealth management gains come at the expense of powerful ‘others’. These actions have no doubt been keenly observed by others, including the governments of emerging giants such as China and India, and closer to home, Indonesia. Singapore's wealth management sector therefore mirrors the city-state's broader history, with success determined by its ability to adapt to external forces.

About the author

Ian Patrick Austin is currently a Senior Lecturer in International Business at Edith Cowan University in Perth Western Australia. He is a member of the Asian Business and Organisational Research Group (ABORG) within the School of Business at the university. His works on Singapore include research manuscripts examining Australia–Singapore relations, Goh Keng Swee and Singapore's Pragmatic Public Policy. Ian is currently conducting policy-oriented research on Singapore's ‘Global City’ status and United States of America–Asian commercial relations.