The supercargo, Jerome Cornelisz, having been on the island for almost a month after the ship had run aground, and seeing the ship reduced to fragments, began to realise that his first intention of seizing the vessel had to be abandoned. Therefore he considered that his next alternative, being at the head of affairs during the absence of the Commodore, was to murder all the people except 10 men, and then with the scoundrels that remained under his command to seize the yacht that was expected to arrive from Batavia to rescue them, and to go pirating with her, or to run into port at Dunkirk or somewhere in Spain.

Willem Siebenhaar, “The Abrolhos Tragedy,” Western Mail (Christmas Number), 24 December 1897, 5.

The 1629 wreck of the Dutch East India Company ship Batavia off the coast of western Australia and the subsequent mutiny and massacre of the survivors is sometimes seen as a gruesome national foundation myth. In 1897 the first English account of the disaster termed the survivors “Australia’s First White Residents,” preceding better-known stories of British invasion and encounter on the east coast by a century and a half.Footnote 1 In recent years the story has grown in popular significance, and is increasingly explored by Australian scholars, artists, and the public. In this article I examine how the wreck of the Batavia and its shocking aftermath was represented by the illustrated book Ongeluckige voyagie, van’t schip Batavia (Unlucky voyage of the ship Batavia), published in 1647 in Amsterdam. This popular work helped shape a new genre of shipwreck narratives, expressing contemporary cultural preoccupations and visual conventions. Notably, it included fifteen copper engravings, comprising six full pages, that focused and dramatised key moments from the narrative. These illustrations were shaped by the period’s unique visual culture, expressing new ideas about pictorial and political space that derived from synergies between cartographers and artists. However the visual narrative also used innovative techniques of montage and vignette to convey the narrative’s drama and affirm principles of morality, honour, and order. While the pamphlet text remains a partial and highly mediated account of the disaster, the images vividly communicate these events to present day audiences. Understanding their original meanings helps us transcend barriers of language, culture, and historical period to engage with this “earliest of Australian books,” as it was termed by the pamphlet’s 1897 translator, Willem Siebenhaar.Footnote 2

The Publishing Context

The Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC) was formed in 1602 and expanded rapidly over its first fifty years, simultaneously fostering the Dutch book trade and its national and international markets. In the seventeenth century a large, predominantly urban Dutch reading public nourished a market for prints, engraved histories, poems, and polemics, and many across Europe were interested in Dutch voyages.Footnote 3 Pamphlets were a highly popular form of cheap print that catered to a large international audience, circulating through international networks; they addressed topical events and issues, although their multimedia diversity of form and content challenges easy definition.Footnote 4 Closely linked to developments in other genres, including books, maps, art, and literature, their dissemination expressed the intertwining domains of the Dutch pictorial tradition, intellectual inquiry, and mercantilism.Footnote 5 Merchants such as Willem Jansz Blaeu moved within an international network of scholars, but crucially, books were merchandise and their saleability to a popular audience was key.Footnote 6

As the largest shipping company in the world during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the VOC’s voyages provided a key means of revealing global human and environmental diversity to European audiences. Given that Dutch prosperity and global success were founded in maritime trade, it is not surprising that shipwreck might assume a powerful cultural significance. The Company’s giant ship-machines, with their specialised technologies and elaborate social order, seemed the cutting edge of modernity and power—and so the disaster of shipwreck ruptured contemporaries’ sense of mastery, reminding them of the might of God and the frailty of humankind. From the time of Jan Huyghen van Linschoten’s Itinerario (1595–1596), returning voyagers’ accounts were quickly printed and translated into the leading European languages, often with high-quality engravings. Already by 1600 the Dutch travel account had become a distinct literary genre, and in the mid-1640s both the disaster and the personal travel account appeared.Footnote 7 Skipper Willem Ysbrantsz. Bontekoe of Hoorn published an archetypal disaster account in 1646, an epic narrative of a ship that caught fire in the Sunda Strait, causing a huge explosion, culminating in the ordeal of seventy-one survivors drifting in a small boat. Bontekoe’s narrative gave these events religious meaning, as the ordeal was cast as a rite of passage and test of “the humanist ideal of community and the Calvinist precept of obedience to the divine will,” while the temptation of cannibalism was “warded off only by the inflexible piety of the godly captain.”Footnote 8

Another prototype was provided by the enormous two-volume Begin Ende Voortgangh, van de Vereenighde Nederlantsche Geoctroyeerde Oost-Indische Compagnie (Origin and Progress of the United Netherlands Chartered East-India Company), published between 1644 and 1646 by one of the leading Amsterdam publishers specialising in navigational and cartographical material during the 1640s, Jan Janssonius (born Jan Janszoon), with historian and editor Isaac Commelin.Footnote 9 Janssonius is now most remembered (and collected) for his epic multivolume atlases—such as the 1657 Atlantis Majoris, and especially the eleven volume Atlas Novus, published 1638–1660, containing the work of around one hundred credited authors and engravers.Footnote 10 Begin Ende Voortgangh is an enormous compendium of travel literature that contains more than sixteen hundred pages of text. It was a landmark in the popularisation of the Dutch travel narrative genre, as well as continuing the venerable tradition of edited voyages of discovery made popular by such late sixteenth-century writers as Theodor de Bry and Levinus Hulsius and those of the early seventeenth century such as Samuel Purchas.Footnote 11 The illustrations and maps are nearly all from earlier editions rather than being printed for the first time.

In the wake of the success of Bontekoe’s narrative, as well as their own Begin Ende Voortgangh, an illustrated pamphlet based on the Batavia’s commandeur Francisco Pelsaert’s journal was published the following year, in 1647, edited by Commelin and published by Janssonius, titled Ongeluckige voyagie, van’t schip Batavia (Unlucky voyage of the ship Batavia).Footnote 12 Ongeluckige voyagie told the story of the ill-fated ship Batavia, sailing on its first voyage with a cargo mainly of jewels and silver designed to increase the VOC’s influence and wealth in the Indies. Two hours before dawn on 4 June 1629, the ship struck the Morning Reef, part of the Houtman Abrolhos off the almost unknown coast of western Australia. While most of the 322 passengers and crew made their way to the flat, inhospitable islands of the archipelago, commandeur Francisco Pelsaert, the skipper Ariaen Jacobsz, and others left in a longboat to search for water, and when they were unsuccessful, continued on the long journey north to Batavia. Meanwhile undermerchant Jeronimus Cornelisz, the most senior VOC officer remaining with the survivors, led a group of mutineers who planned to kill most of the survivors, seize any rescue ship, and go pirating. They separated the group of survivors into smaller parties isolated on different islands, and marooned the VOC soldiers on the seemingly barren Wallabi Island with instructions to look for water. The mutineers began to kill the remaining survivors a few at a time, often secretly or at night, although after several weeks they launched several open massacres, eventually murdering over 120 people. In the meantime, the soldiers on Wallabi Island unexpectedly found water, and led by Wiebbe Hayes, managed to fend off attacks from the mutineers. A battle between the two forces was dramatically interrupted by the return of Pelsaert from Batavia in the ship Sardam, and the mutineers were captured, interrogated with torture, and several executed, including the ringleader Cornelisz.

Disaster Narratives

Although vastly shorter than Bontekoe’s account and Begin Ende Voortgangh, focused on just three voyages, and with relatively few illustrations, Ongeluckige voyagie also became very popular, as indicated by eight reprints and further pirated editions.Footnote 13 Ongeluckige voyagie drew together a range of key contemporary concerns, including global exploration and trade and also the destruction of these grand schemes, human wickedness and bloodlust, and the punishment of immorality. For Dutch and European readers of the era, such accounts responded to a craving for disaster stories—expressing the perennial human fascination with danger, but also a specifically Dutch frontier history, where survivors brave the waters and inherit the promised land. In these accounts, sin is divinely punished, but expiation follows through suffering and providential intercession at a time of direst need.Footnote 14 Simon Schama’s magisterial account of Dutch culture during the Golden Age explores the centrality of “trials by water” to Dutch identity and culture, founded upon the “primal Dutch experience: the struggle to survive rising waters.”Footnote 15 Schama defines a distinctively Dutch moral geography in which effort and perseverance were required for survival, arguing that “to be wet was to be captive, idle and poor. To be dry was to be free, industrious and comfortable.”Footnote 16 As he notes, epic disaster narratives such as Bontekoe’s that arose from real events were structured by the expectation that good fortune would be struck by providential retribution and an ordeal from which only the virtuous and God-fearing would escape. Retribution is sudden and often directed at worldly prosperity, provoked by moral corruption from within.Footnote 17 But Schama also argues that as well as catering to an enduring public appetite for “armchair calamity” and the vicarious enjoyment of danger that we still relish today, these stories and images were “parables of a manifest national destiny and followed a standard moral formula.”Footnote 18

Recent scholarship has also attended to the way that shipwreck may reveal the uncertainties of cultural principles and moral geography by rupturing the Dutch sense of global consciousness and power, highlighting the dangers of increasing mobility, and confronting “domestic audiences with the human sacrifice and suffering required to secure their status as global consumers and seemingly transcendent selves.”Footnote 19 Literary scholar Carl Thompson argues that shipwreck imagery served the cultural purpose of attempting to “comprehend, frame, and delimit the trauma,” addressing a collective anxiety by “helping communities to negotiate the trauma of shipwreck and reconciling them to such tragedies as the necessary cost of modernity, empire and trade.”Footnote 20 He suggests that this negotiation of shipwreck may itself have played a significant part in the emergence of modern subjectivity. Again, Josiah Blackmore argues that these stories of destruction are a sobering reminder of mortality, prompting humility and undermining expansionist hubris.Footnote 21

But unlike the sailor’s story from below, the text of Ongeluckige voyagie indirectly expresses the perspective of a long-term and senior employee of the VOC reporting to his strict and distant superiors, aiming to justify his own actions and urge his devotion to Company interests. In analysing the pamphlet text I have relied upon Willem Siebenhaar’s translation, first published in the local Australian newspaper the Western Mail in 1897, the first English translation of the pamphlet.Footnote 22 Despite his ultimate control over the pamphlet’s form, shaped by the enormous contemporary success of the genre of the illustrated travel account, Commelin based his pamphlet on a rearrangement of Pelsaert’s journals, producing a complex multivocal text.Footnote 23 Pelsaert’s journals comprised the narratives of a range of individuals not normally considered authors, including the interrogated criminals and witnesses, some elicited under torture or threat of torture, whose accounts were rewritten and embedded within Pelsaert’s and subsequently Commelin’s text.Footnote 24 The first edition of the pamphlet features the editor, Commelin, appearing in the first person to explain and excuse its provisional status. Commelin wrote “To the Reader”:

I have not yet at present a daily account of the events that took place about the ship and among the people who reached the islands while the Commodore had left for Batavia to seek assistance. The following meagre narrative and account of judicial proceedings and confessions are all that has come to hand so far. They contain, however, the principal horrors and murders that occurred and also the justice done to the perpetrators. Still the want of a continuous record has prevented my polishing this story in such good order as I had wished. I would, therefore, request anyone who should be in possession of further information or notes to place them in the hands of the printer, so that they may be added to a second edition. For the same reason I trust that deficiencies of this my work will be excused. With this I bid the reader farewell, recommending him to read all with judgement and discrimination.Footnote 25

Such practices of literary mediation—including appropriation, editing, and publishing—determined the text’s audience and effects.Footnote 26 VOC officials at Batavia in 1629, such as Antonio Van Diemen, were critical of the ship’s lax discipline prior to the wreck, and of Pelsaert’s decision to leave the wreck and the survivors, inclining to see Pelsaert’s blame of Jacobsz as a means of excusing himself.Footnote 27 So in the immediate aftermath of events, writing in December 1629 from Batavia, Pelsaert emphasised his care for the best interests of the VOC. He addressed his employers: “Honourable, Brave, Wise, Provident, Very Discreet Hon. Lords, I shall pray God that according to my humble Wishes, He will safeguard the Hon. Lords from further damage, and will bless them with a year of expansion and abundant trade and all that is necessary for their souls’ salvation.”Footnote 28 Such expressions might appear merely rote, but as Susan Broomhall argues, they formed part of the VOC’s ritual of communicative practice, in which even stylised affective language could reinforce ideals, hierarchies, and relations of familiarity across its global network.Footnote 29

Although we gain many hints of insubordination, negligence, and fragmentation of the social order within the Pelsaert/Commelin narrative, ultimately it seeks to reinforce traditional Dutch moral geography, aligned with VOC principles. In his reading of accounts of mutinies and wrecks of Dutch East India Company ships, Richard Guy emphasises these texts’ function in supporting the Company’s discourse of discipline: as “worst-case survival manuals” they advise readers that the best option in the event of disaster is to obey the officers’ orders and the Company’s rules, and explicitly link ship discipline to religious virtue.Footnote 30 So in seeking to justify his own behaviour, Pelsaert (and his later editors) structured his account as a battle between God and the Devil, good and evil, represented by the discipline and piety of the VOC and its officers, especially himself, arraigned against the heretical beliefs and evil deeds of Cornelisz, who “by his innate corruptness had allowed himself to be led by the Devil.”Footnote 31

When Cornelisz was first questioned, Pelsaert asked him “why he allowed the Devil to lead him so far astray from all human feeling … solely out of bloodthirstiness to attain his wicked ends.”Footnote 32 Pelsaert recorded examples of the way that Cornelisz had influenced his followers, for example eighteen-year-old Jan van Bemmel, who had wandered the island calling “Come now, devils with all sacraments, where are you? I certainly wish I now saw a devil, and who wants to be boxed on the ear? I shall certainly manage it!” Pelsaert recorded that “daily he had heard from Jeronimus that there was neither devil nor Hell, and that these were only fables.”Footnote 33 Frequently Pelsaert commented on the testimonies and confessions he collected, such as when he noted, “but it seemed that [despite] the cruel things they had started … God Almighty had stopped their evil intention by destroying some of the principal leaders by the sword and by causing Jeronimus, the Author of all, to be captured, as before mentioned, in order to make more known to all men the wonder of His justice.”Footnote 34

Several scholars argue that there was a shift within shipwreck narratives over the seventeenth century to considering that extremes of suffering shed light on resilience and the endurance of the self, the threshold between humanity and animality, and the strength of the social contract.Footnote 35 This concern with human behaviour rather than providential order is evident in Pelsaert’s lengthier journal, where he interprets the mutinous “scoundrels” behaviour as a breach of the self, and a brutal transformation: in discussing the mutineers’ shipboard assault on the passenger Lucretia Jansz [van der Mijlen], for example, Pelsaert suggests that the perpetrators in their cruelty had changed into animals under the influence of evil, exemplified by Cornelisz. Mattijs Beer, noted Pelsaert, “has behaved himself very inhumanly here on the island near the Wreck, and has gone outside himself, namely, allowing himself to be used willingly by Jeronimus.”Footnote 36 Beer was one of the gang who had plastered Lucretia Jansz “with dung and other filth on the face, and next over the whole body.”Footnote 37 Allert Jansson “changed himself into worse than an evil tiger filled with all thinkable wantonness and cruelties,” also as evidenced by his obedience to the skipper’s order to “smear the face and the whole body of the wife of a certain undermerchant, named Lucretia Jansz, whom he very much hated, with dung and other black substances.”Footnote 38 But in the end Pelsaert emphasises divine judgement, concluding that providence had ensured a happy ending:

More than 120 persons, Men, Women, and Children, had been Miserably murdered, by Drowning as well as by Strangling, Hacking and Throat-cutting; and also had in mind to do still more, which they would have put into action if Almighty God had not been aggrieved and thwarted their plan and all their intentions. Moreover, [He] has stopped them, submitting them to their well-earned punishment and God’s just condemnation for the villainies they have so long committed and the Very great lust they have had therein. God the Almighty be thanked for the good outcome and the rescue of us all. Amen.Footnote 39

However, given that only 116 of Batavia’s 322 passengers survived to reach Batavia, many observers, past and present, have challenged Pelsaert’s evaluation of the tragedy as a “good outcome.”

Visualising Unlucky Voyage

Pelsaert’s framing of events as a battle between good and evil, godliness and heresy, is made explicit in Commelin’s pamphlet, which can also be seen as a moral fable: the first edition’s title page cast it as “a caution to all who would sail to the Indies.” The pamphlet was further distinguished by the fifteen fine copper engravings that complemented the text and identified key moments in its bloody narrative. The engravings illustrating Ongeluckige voyagie constitute an innovative visual narrative that gives more pointed meaning to the text. The moments chosen for illustration express contemporary views of what was important, as well as what could be seen. They draw from contemporary visual conventions, but are also novel in communicating the Batavia’s bloody tale effectively to a popular audience through visual strategies of movement and vignette.

Five of the six illustrated pages show the shipwreck and subsequent events as a succession of seascapes, part of the late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century Dutch artistic tradition depicting danger and disaster at sea.Footnote 40 Such highly dramatised images were of course prompted by the extraordinary expansion of seafaring in the newly independent Dutch Republic. But several of the engravings in Ongeluckige voyagie occupy the interesting space between map and picture already trialled in maps, paintings, and books, including van Linschoten’s formative Itinerario. These exemplify the “mapping impulse” of seventeenth-century Dutch art first identified by art historian Svetlana Alpers, featuring shared interests between paintings and maps as descriptive objects that constructed and conveyed knowledge. Alpers’s classic The Art of Describing insists on the “visuality” of Dutch art—that is, instead of referring to a textual meaning, as is the case in Italian Renaissance art, it “serves and energises a system of values in which meaning is not ‘read’ but ‘seen,’ and in which “new knowledge is visually recorded.”Footnote 41 Here the technology of visualisation acts primarily to document behaviour—describing rather than prescribing. Alpers identifies links between Dutch art, maps, and mirrors in the Low Countries via features such as rigorous accuracy and the apparently contingent place of the viewer in relation to the image.Footnote 42

Ultimately, as recent research has shown, the seventeenth century gave rise to new conceptualisations of space that were simultaneously and cooperatively explored in maps, surveying manuals, cosmographic studies, landscape paintings, and many other media.Footnote 43 Ulrike Gehring and Peter Weibel argue that rather than originating in landscape painting, this approach actually stemmed from the frontispieces of treatises for training geographers, surveyors, and fortification engineers that appeared in large print-runs from the 1580s. Such manuals provided instructions for reproducing landscapes to scale and also had “programmatic title pages on which the infinite landscape space is already anticipated.”Footnote 44 Particularly transformative was the work of French printmaker Jacques Callot and Flemish painter Pieter Snayers, whose images stand at the intersections between art and science during a period when artists, engineers, scientists, and craftsmen collaborated. Callot, for example, one of the most famous artists of his time, worked with military cartographers to produce the landmark overview landscape The Siege of Breda 1624–1625 (1628). This etching deploys visual strategies for the dissolution of spatial boundaries derived from navigation manuals and marine paintings, and locates the military action in “a precisely described landscape true to scale and topography”Footnote 45 (Figure 1). Its diverse perspectival spaces, although not internally coherent, created a new long-distance effect that was subsequently copied by painters such as Snayers.

Fig. 1 Jacques Callot, The Siege of Breda 1624–1625 (1628). Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe (inv 1995–1), 147cm×125.5cm.

In producing illustrations for cheap broadsheets, books, and popular pamphlets like Ongeluckige voyagie, seventeenth-century engravers drew freely upon these sophisticated antecedents, as well as their translations over subsequent years into engravings illustrating travel accounts by Lodewijcksz, De Marees, Linschoten, Spilbergen, Van Neck, and others. In addition, broadsides produced during the Thirty Years’ War, for example, combined bird’s-eye views of battles, cities, and sieges to make these strategic military tactics immediate and explicable to the viewer.Footnote 46 As one English advertisement for a print of the siege of Breda noted, “you may with the eye behold the siege, in a manner, as lively as if you were an eye-witnesse.”Footnote 47

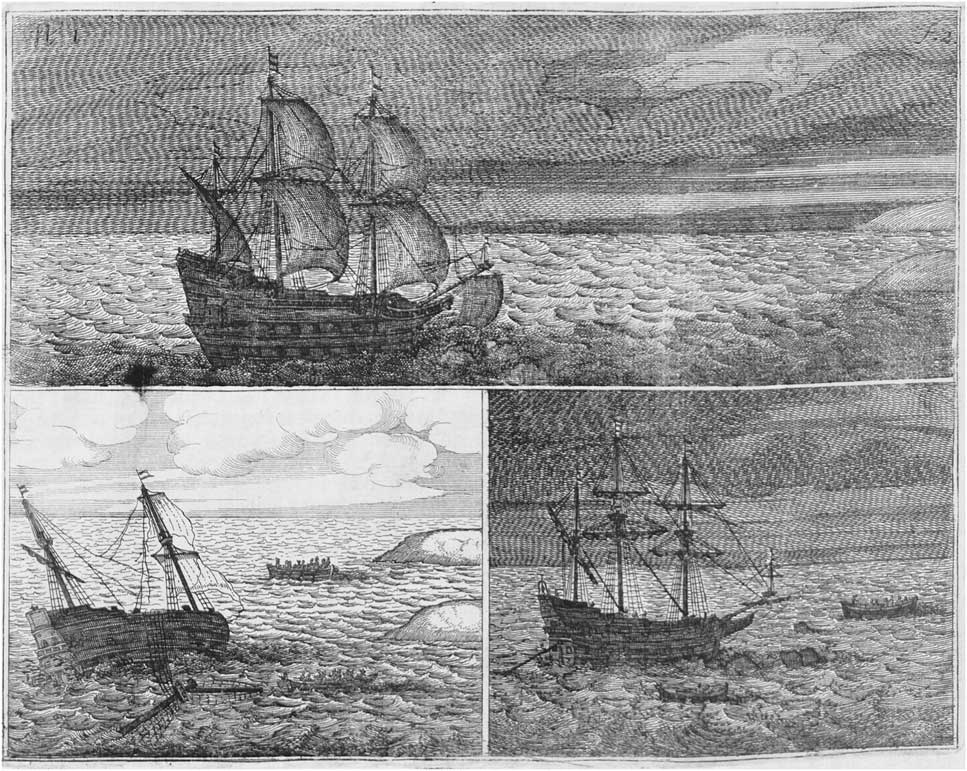

For all their apparent accuracy of detail, Dutch shipwreck scenes were structured according to contemporary moral and visual principles, rendered in highly generalised terms, and rarely depicted identifiable shipwrecks.Footnote 48 Like their textual counterparts, the conventions of shipwreck imagery in seventeenth-century Dutch art expressed an underlying conviction that “these disasters had a place in the larger cosmic scheme of things and that their destructive potential was thus clearly bounded.”Footnote 49 This sense of divine order is signalled very strongly in Unlucky Voyage’s first illustration (“No 1”), which actually comprises three engravings that the eye follows clockwise, from top to bottom left, to create a visual narrative. First we see the moment just before impact, as the Batavia, under full sail, crashes on to the reef, barely visible here as a watery disturbance under the bow. The face of God looks sombrely through the clouds (Figure 3: Detail “No 1”), demonstrating his divine intention to prevent the planned mutiny and punish the villains. These three scenes are reminiscent of the portolans (sailors’ instructions) used in nautical manuals, which Ulrike Gehring has shown influenced the visual representation of space over these decades.Footnote 50 They evoke coastal views, showing three-dimensional ships sailing along in front of detailed topographic land profiles, which were combined with the cartographic aerial view to orientate the sailor (Figures 2 and 3).

Fig. 2 “No. 1” (a., wreck of the Batavia on 4 June 1629, “about 2 hours before daybreak”; b., before dawn; c., the next day, 5 June 1629). Commelin, Ongeluckige voyagie. Courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia <919.412 PEL>.

Fig. 3 Detail from “No. 1.” Commelin, Ongeluckige voyagie. Courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia <919.412 PEL>.

Of particular interest is the engraver’s decision to create a sense of temporal movement through showing successive, precisely located moments in the story: Moving to the bottom right hand image, it is still nighttime, placing the image within the first hours of terror; the ship remains upright and with mainmast intact while the crew desperately works to free it; already the sails are furled and boats work to warp the ship off, while discarded cannons lie on the reef. The bottom left shows us the scene the following morning with the now leaning ship, its mainmast cut down and dragging overboard, and boatloads of people rowing to the distant islands. The arrangement of the images in this way—visualising quickly successive moments from the disaster—is an effective way of representing the temporality of shipwreck, which in a single image is reduced to the singular terrible moment of impact, or indeed, any of its subsequent moments, but as Pelsaert’s journals make so excruciatingly clear was actually a long-drawn-out period of hours and days, as the ship gradually settled and broke up amidst the survivors’ desperate activity. Joining these specific, identifiable moments also acts to create a kind of filmstrip temporality that draws the viewer into the narrative, paralleling the events recounted by the written text.

The arrangement of the images within the text was carefully planned, as indicated by the instruction “Aenwijsinge voor de Boeck-binders waer de Platen moeten ingevoeght worden” (Instructions for the bookbinders where the plates must be inserted), and indeed the relationship of text and image is very close; marginal notes further highlight key moments in the text, and these also correlate closely with the images.Footnote 51 Engraving “No. 2” follows folio 8, for example, and depicts events described on that page, showing two scenes: At top, the wreck, figures still visible on deck, while a rowing boat hovers near the bow (Figure 4

Fig. 4 “No. 2.” Commelin, Ongeluckige voyagie. Courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia <919.412 PEL>.

). A figure can be seen jumping from the boat into the water holding a plank—this was the brave carpenter Jan Egbertsz of Amsterdam, who swam through high surf from the ship to Pelsaert’s yawl, bringing Cornelisz’s request for rescue, and back again, taking timber to make sweeps.Footnote 52 The yawl can be seen behind, and two small islands with tents and survivors. At bottom we see three small boats with sails among small hummock islands, with a few figures exploring.

Next (Figure 5) we see a single scene of massacre, signalling its central importance, and the most spectacular form of murder. The mutineers killed most of their victims in smaller numbers over a longer period, and often clandestinely, but large-scale massacre was visually more accessible. The scene may represent the first massacre of at least fifteen people on Traitor’s Island on 9 July or perhaps subsequent attacks on Seals Island on 15 and 18 July. The vestiges of the wreck lie in the foreground, with barrels and other flotsam widely scattered. Immediately behind, and closely juxtaposed in a great distortion of scale, an almost aerial vantage point provides us with a map-like depiction of a massacre in progress. Two figures attack with swords and clubs a helpless person lying on the ground, bodies lie dead, a few have run into the sea to escape, a child runs towards someone being cut down, a few stand around helplessly watching, and three figures in the far distance are close to the ground in an unidentifiable activity. Yet they are spaced evenly across the plane of the island, its empty abstraction enhanced by a neat ledge-like circumference. No women are clearly visible. Here we see a cartographic sensibility joined with an interest in descriptive specificity—the twin poles of geography and chorography.Footnote 53 Like Brussels painter Pieter Snayers’s oil paintings of particular locations pictured almost from a bird’s-eye perspective with naturalistic figures and trees populating the foreground, this hybrid image constitutes both map and landscape. Snayers’s works often centre on specific battles so that they simultaneously constitute journalistic records, military histories, and landscape scenery. Visual artists took Snayers’s scaled sections of three-dimensional space and transformed them into an uninterrupted continuum.Footnote 54

Fig 5 “No. 3” [Massacre]. Commelin, Isaac, ed., Ongeluckige voyagie. Tot Amsterdam: Voor Jan Jansz, 1647. Courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia <919.412 PEL>.

The small vignettes of figures in conflict also remind us of Callot’s 1620 etching The Fair at Impruneta, in which the crowd is grouped into tiny vignettes. Alexandra Onuf argues for a tendency towards “enlivening landscapes” at this time, even to the extent of reworking older plates by adding theatrical tableaux of gunfights and miniature battles to formerly empty landscapes.Footnote 55 Such “irruptions of violence” are reminiscent of the Flemish iconographic tradition boerenverdriet, or peasant sorrow, showing the injustice of war from a peasant perspective.Footnote 56 Callot himself was influenced by boerenverdriet prints in producing his famous series of eighteen small etchings known as The Miseries and Misfortunes of War, based on his experiences during the 1618–1648 Thirty Years’ War. The Miseries and Misfortunes of War was marketed widely from the 1630s, condemning abuse by soldiers and constituting the first visual critique of war.Footnote 57 This critical theme was evoked by the pamphlet’s depiction of the armed mutineers attacking their innocent victims. Comparison with Janssonius’s contemporary publications also indicates some shared conventions: the landmark two-volume Begin Ende Voortgangh also featured engravings showing ships sailing past islands such as St Helena, its boundaries enclosing three-dimensional hills and mountains. Military art presented in books at this time also translated the conventions of high art into cheaper mass-produced form.Footnote 58

But although they strike us as being very “map-like,” unlike Janssonius’s atlases, the scenes of Ongeluckige voyagie are spatially nonspecific, lacking any name or identifying feature: like the clouds and sea, the land merely provides a natural and nondescript backdrop for human action. The schematic treatment of the islands—drawn in cartoonish fashion as small round cakes of land—also foregrounds human action. One factor of course was that even by 1647 the archipelago was not widely known, although it had been first sighted in 1619 by Frederick de Houtman, captain-general of the Dordrecht.Footnote 59 The islands did not appear on a published map until 1622, on a little-known portolano by VOC cartographer Hessel Gerritsz.Footnote 60 Although Ongeluckige voyagie’s scenes are precisely located in temporal terms in relation to Pelsaert’s narrative, their spatial indeterminacy underlines the survivors’ social and moral dislocation, marooned in a heterotopic space of disorder and otherness (Figures 6 and 7).

Fig. 6 “No. 4.” Commelin, Ongeluckige voyagie. Courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia <919.412 PEL>.

Fig. 7 “No. 5” Commelin, Ongeluckige voyagie. Courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia <919.412 PEL>.

The visual narrative then returns to the filmic mode of the first two full pages, continuing with the return of Pelsaert from Batavia (“No. 4” in top left corner), shown sailing towards the Abrolhos islands on the Sardam and so dating it between 15 July and 7 September. At top right the Sardam approaches an island where smoke rises from three fires and figures are fighting, indicating the battle between the mutineers and the soldiers then underway (7 September). A boat rows towards the Sardam presumably to be warned by Wiebbe Hayes of the intended treachery of the mutineers. At bottom, we see an anchored ship with two small rowing boats approaching the island with four tents, and figures with guns and clubs. Again, image “No. 5” comprises four scenes, showing successive moments from the dramatic denouement in a rapid-fire filmic mode evoking the sequence of action. At top left a raft nears an island with three tents and figures with weapons, moving to top right, where two rowing boats approach an island, with the closest firing guns on the people on the island. At bottom right, two men remain in the boat, while the others have disembarked and are fighting; several bodies lie on the ground. At bottom left, a large group stands on the right, seemingly the liberated survivors, now safe again.

Torture and Punishment

Having shown the dramatic and violent crimes committed on land and at sea, the final illustration, “No. 6,” shifts to depict the moral consequences of immorality, returning us to the ordered social space of investigation, confession, and execution (Figure 8). It comprises two scenes depicting the punishment by mutilation and hanging of the ringleaders. At the top are shown three gallows, the most distant with two swinging bodies, in the middle distance two dead men swing and another is being taken up a ladder. In the foreground a man kneels while holding out his right hand to be chiselled off. Severed hands already lie around the anvil. A ship lies at anchor offshore. At bottom, in an enclosed space, torture is inflicted on four men: two are suspended by ropes and pulleys from the ceiling, their arms strained backwards; one lies in the foreground centre on a table, being given the water torture. These are perhaps the most alien images to us, evoking a culture of spectacular violence that belongs to a different, harsher age. The legal system of the United Provinces of the Netherlands allowed for judicial torture and corporal punishment, including the death penalty. The States General of the Netherlands allowed the VOC to administer such punishment in Batavia’s courts, and like Dutch law, this was “inflicted differentially according to social status, religion, gender and ethnicity.”Footnote 61

Until the late eighteenth century it was customary across northwestern Europe to publicly display the bodies of executed individuals.Footnote 62 Like other popular illustrations of the first half of the seventeenth century showing the punishment and disgrace of criminals, such graphic violence worked as a mechanism to dishonour the men, just as the actual public executions did, by “disseminating shame.” Through depicting this degrading punishment, illustrators such as Claes Jansz. Visscher signalled the subjects’ loss of status in respectable society.Footnote 63 In the execution of Jeronimus and his colluders in Ongeluckige voyagie we again see the influence of Callot’s Miseries and Misfortunes of War, a moral tale that details punishment inflicted by military law, including torture and spectacular violence such as criminals being broken on a wheel and hanged men swinging from a tree. As Peter Raissis notes, this “shocking spectacle [is] belied by Callot’s refined touch and the measured elegance of the composition at large.”Footnote 64 The dungeon scene of torture also has precedents, showing the three chief methods used to elicit confessions from the mutineers: water torture, the rack, and keelhauling—here the suspension of the convicted by their arms, causing dislocation and frequently death (Figure 8).

Fig. 8 “No 6.” Commelin, Ongeluckige voyagie. Courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia <919.412 PEL>.

The final illustration of torture has proved puzzling to modern observers, because although it is linked to the final section of Commelin’s narrative, detailing the torture and confession of each accused man aboard the Sardam between 17 and 28 September 1629, the space does not appear to be aboard a ship, but rather a room in a building. There are two possibilities: First, perhaps the engraver lacked expert knowledge of ships and/ or simply relied upon the many precedents of torture scenes constituted by the pictorial genre termed the Theater des Schreckens (theatre of horror).Footnote 65 Second, the image may refer to the subsequent torture of mutineers in Batavia, where the evidence of Antonio Van Diemen of the Council of the Indies indicates that Adriaen Jacobsz, Jan Evertsz, and Zwaantie were imprisoned, interrogated, and punished.Footnote 66 In June 1631, after a year and a half of imprisonment, van Diemen wrote to the VOC that Jacobsz “has been condemned to more acute examination and has been put to the torture.”Footnote 67 Further, of the nine mutineers who returned to Batavia in early December 1629, lance corporal “Stone-Cutter” Pietersz at least was kept for trial in Batavia, and punished after return.Footnote 68 The omission of this image from subsequent editions may indicate that it was considered peripheral to the shipwreck itself, or too generalising to warrant inclusion.

Finally, it is worth considering what is missing in this visual account, and how these “blind spots” shape its impact: what does the visual narrative add to, overlook, or emphasise? Notably absent is the covert nature of the mutiny, and the many secret, nocturnal, or otherwise concealed assaults. These challenged contemporary pictorial conventions, rendering much of the rebels’ behaviour invisible and producing an emphasis in the engravings upon spectacular violence. Similarly, the moral and emotional significance of women’s ill-treatment throughout the narrative—including the shocking shipboard attack on the respectable wife Lucretia Jansz prior to the wreck and the sexual slavery of several survivors—is invisible in the engraved series. Women’s voices are also absent from Pelsaert’s journals, except as blameless victims. In the published Ongeluckige voyagie, a letter apparently from Wiebbe Hayes is introduced, telling how Lucretia confronted her rapist Cornelisz just before he was hanged, when he publicly admitted that she had never freely consented to sexual relations. Whether authentic or not, this serves as testimony to her chasteness.Footnote 69 This invisibility accords with contemporary cultural conventions regarding women’s ideal role in the Dutch Republic in the seventeenth century, proscribed to the domestic, private, and morally regulated sphere, as detailed in marriage and household guides such as Jacob Cat’s popular advice book, Houwelyck (Marriage), first published in 1625. In art the virtuous woman is characterised by her quiet modesty and the centrality of domestic life, sometimes suggested visually by her association with the turtle.Footnote 70 There was no place for the respectable woman in the heterotopia of shipwreck and mutiny, and just as the illustrator dishonoured the criminals by depicting their final degradation, he chose not to intensify the women’s suffering by exposing their humiliation.

As a coherent whole, Ongeluckige voyagie’s narrative moves from the moment of God’s retribution, through disaster, conflict, and chaos, to the reassertion of social and providential order. The images complement the text in their emphasis upon a narrative logic structured by divine mandate, as well as reinforcing the laws and practices of the VOC. The complex text edited by Commelin was given more specific and immediate meaning by Janssonius’s engravings, isolating key moments in the tragedy but also creating a visual logic and temporality of their own through techniques of sequencing and juxtaposition. The illustrations’ combination of temporal movement and human action is distinctive, and effectively conveyed the drama and brutal intensity of events. The criminals are dishonoured as they deserve, as expressed through the graphic violence of their torture and execution. In this way the series expresses the constellation of art and science produced by the period’s unique political and economic history, translated by engravers into a range of popular print forms. New conceptions of space stemming from engineering, cartographic, and military visual strategies shaped this popular pamphlet, exemplified by the sophisticated and innovative perspectives characteristic of Callot and Snayers. These, joined with a concern to trace the moral implications of mutiny and the punishment of unlawful violence, underlined the geographic and moral isolation of the shipwreck as a heterotopic space of chaos and depravity. In sum, the pamphlet constituted a lively combination of text and imagery that successfully engaged an expanding popular audience, contributing to the new genre of disaster narratives. Through these strategies, Ongeluckige voyagie domesticated the tale of an almost unimaginably distant tragedy, both reaffirming the might of the VOC yet also providing a frisson of strangeness, an intimation of the wildness that made their own Dutch world so safe.

Whereas originally Ongeluckige voyagie was a popular narrative produced for European audiences, today it has become an Australian story. As its first English translator, Willem Siebenhaar, noted in 1897, this “earliest of Australian books” told the story of “the first settlers—involuntary, it is true—in Australian territory.”Footnote 71 At a time of nationalist debate leading up to federation in 1901, he suggested that while “its heroes and villains are Dutch and Frenchmen, and its publisher honest Jan Jansz, of Amsterdam, the whole deals with Australia and Australian settlement, and gives us a glimpse of aborigines similar to those who still inhabit our colony.”Footnote 72 Recent retellings have also suggested that the tale of the Batavia, gothic as it seems, contributes to a long-term Asian-centred Australian past, revealing the cosmopolitan networks characterising this region from the sixteenth century, and undermining the narrative of fatal British impact.Footnote 73 In recent decades archaeological and scientific research has recovered the underwater and terrestrial sites of the Batavia tragedy, and facilitated archaeological reconstruction and investigation of the wreck.Footnote 74 Through maritime archaeology the site has been relocated, uncovered, reassembled, and analysed to piece together these long-ago events in a systematic process governed by scientific protocols. Yet this seemingly objective approach towards the story belies its intensely affective power, once evoked in readers by empathy with Dutch neighbours and fellow-citizens, but now elicited through the resonance of objects.Footnote 75 We still love disaster stories, wherever they are set, and the shipwreck still carries a potent cultural freight. Perhaps today the sea is less central to our cultural imaginary, and the airplane or even interplanetary disaster have superseded the shipwreck in rupturing our fantasies of transcendence and power. Nonetheless the Batavia shipwreck remains a heterotopia, a place outside the norms and rules of society, and a space of otherness that makes our own comfortably ordered world possible. As it recedes further into the past, Ongeluckige voyagie’s vision of madness and brutality continues to compel.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Alistair Paterson, Ted Snell and Paul Uhlmann for inviting her to participate in the Batavia: Giving Voice to the Voiceless exhibition, and to Arvi Wattel, Susan Broomhall, Susanne Meurer, Erica Persak and the Kerry Stokes Collection for their generosity and advice.