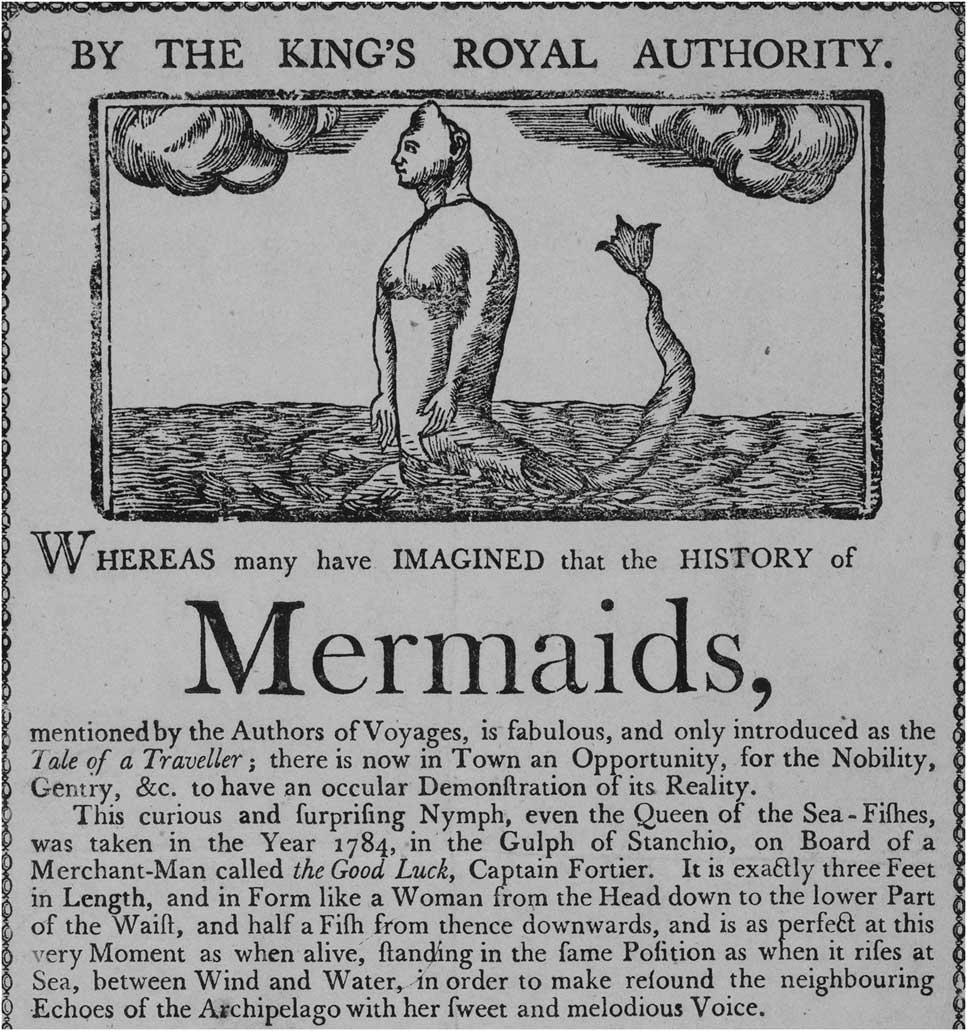

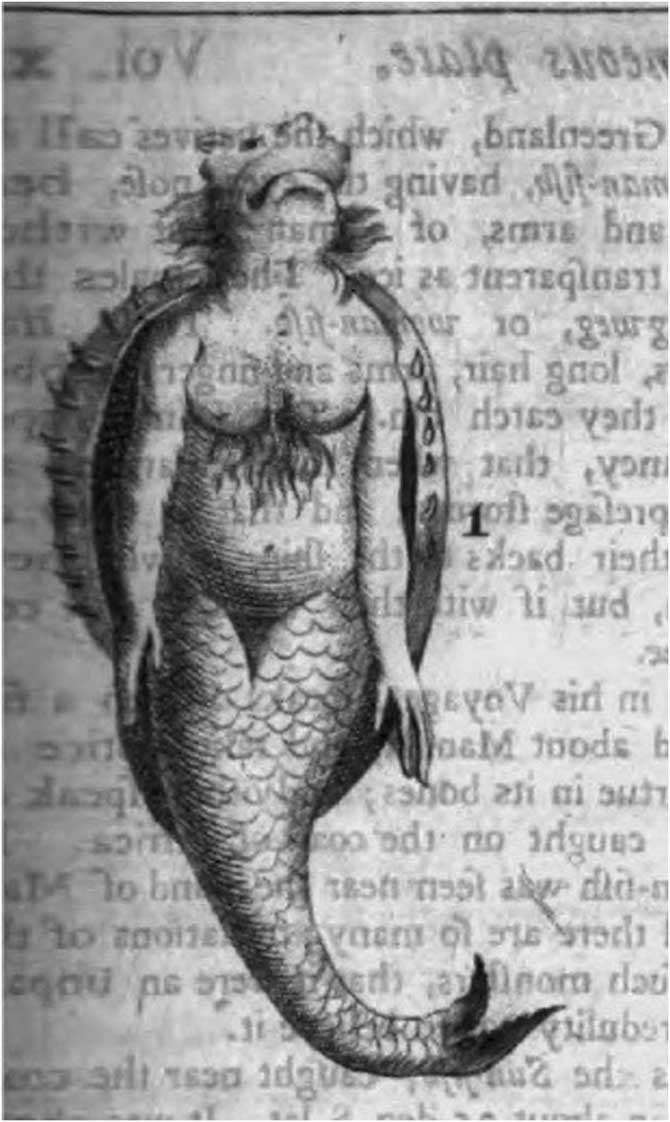

A broadside circulated throughout London in 1795 that announced, “Whereas many have imagined that the History of Mermaids, mentioned by the Authors of Voyages, is fabulous, and only introduced as the Tale of a Traveller,” there now existed “an ocular Demonstration of [merpeople’s] Reality” on exhibition at London’s Spring Gardens. Captured in the Mediterranean Ocean in 1784 and now displayed “BY THE KING’S ROYAL AUTHORITY,” this preserved mermaid specimen was “exactly three feet in Length, and in Form like a Woman from the Head down to the lower Part of the Waist, and half a Fish from thence downwards.” Yet, as demonstrated by the broadside’s accompanying image (figure 1), this mermaid did not exhibit the beautiful female form of myth. A horned, bald head replaced flowing hair, while the specimen’s face was defined by masculine rather than feminine features. Its torso was also rather misshapen, as were its stunted arms. Such a representation reveals larger ideological transformations, for by the close of the eighteenth century, European Enlightenment thinkers had restructured their cultural and scientific imaginations to encompass a new sort of merpeople—ugly, frightening creatures that were a far cry from figures that had long decorated cathedrals and filled travellers’ stories. Despite detracting voices, well-respected philosophers such as Carl Linnaeus, Cotton Mather, Benoit de Maillett, Peter Collinson, Erik Pontoppidan, Jacques-Fabien Gautier, François Valentijn, and Louis Renard transformed mermaids and tritons from creatures of lore into specimens worthy of in-depth scientific investigation.Footnote 1

Fig. 1 “A ‘curious and surprising Nymph…taken in the Year 1784, in the Gulph of Stanchio,’ and exhibited at the Great Room, Spring Gardens, London, in 1795.” Reproduced with permission of London Metropolitan Archives, City of London.

Over the past thirty years, scholars have stressed the importance of “wonder” for Enlightenment thought. As historians Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park contend, even as many Enlightenment thinkers derided wonders in their scientific studies, they could not ignore the wondrous aspects of nature, for they were “markers of the outermost limits of what they knew, who they were, or what they might become.” Though Enlightenment thinkers liked to style themselves arbiters of a “new science [with an] objective approach to the study of nature,” wonder, mystery, and superstitions remained central to their investigations of humanity and the natural world. As Bob Bushaway has argued, eighteenth-century English thinkers often accepted “alternative belief” (that is, “superstitions”) in their everyday lexicon: though “at odds with orthodox belief…they sat comfortably alongside formal knowledge or religious belief.”Footnote 2 Thus, while a thick vein of scepticism marked Enlightenment thinkers’ studies, such investigations cannot be divorced from European gentlemen’s concurrent quest to merge the wondrous and the rational. Perhaps nowhere is this more apparent than in philosophers’ investigations of merpeople.

Examining Enlightenment philosophers’ debates over mermaids and tritons illuminates their willingness to embrace wonder in their larger quest to understand the origins of humankind.Footnote 3 Naturalists utilized a wide range of methodologies to critically study these seemingly wondrous creatures and, in turn, assert the reality of merpeople as evidence of humanity’s aquatic roots. Besides publishing accounts in newspapers, scholars of merpeople exchanged information and ultimately published their oft-controversial (but scientifically driven) research in respected outlets such as the Gentleman’s Magazine and Scot’s Quarterly. As with other creatures they encountered in their global travels, European philosophers utilized various theories—including those of racial, biological, taxonomical, and geographic difference—to understand merpeople’s place in the natural world. By the second half of the eighteenth century, certain philosophers integrated merpeople into their explanation of humanity’s origins, thus bringing this phenomenon full circle.Footnote 4

Monsters Sell Newspapers: Merpeople in the Rag Linen

Enlightenment thinkers’ pursuit of merpeople cannot be understood without recognizing the culture of acceptance that surrounded mermaids and tritons by the eighteenth century. Not only did historical sightings of these mysterious creatures stretch deep into time and far across the globe, but mermaids and tritons decorated cathedrals and churches throughout Great Britain and the Continent, graced heraldry, signs, and maps, and served as key motifs in mythologies from Ireland to Spain. Many Enlightenment scholars, in short, would have grown up surrounded by the culture of merpeople.Footnote 5

Such cultural immersion is perhaps best reflected in the considerable amount of mermaid and triton sightings recorded in eighteenth-century British American newspapers (often reprinted from British and European newspapers). On 6 May 1736, for example, Benjamin Franklin informed readers of his Pennsylvania Gazette of a “Sea Monster” recently spotted in Bermuda, “the upper part of whose Body was in the Shape and about the Bigness of a Boy of 12 Years old, with long black Hair; the lower Part resembled a Fish.” Apparently, the creature’s “human Likeness” inspired his captors to let it live. A 1769 issue of the Providence Gazette, similarly, reported that crewmembers of an English ship off the coast of Brest, France, watched as “a sea monster, like a man” circled their ship, at one point viewing “for some time the figure that was in our prow, which represented a beautiful woman.” The captain, the pilot, and “the whole crew, consisting of two and thirty men” verified this tale. The Virginia Gazette, furthermore, reported in 1738 that Englishmen had caught a strange fish “supposed by many to be the Triton, or Merman of the Antients, being four Feet and a half in Length, having a Body much resembling that of a Man” just outside of Exmouth, England. And only one year later, the same journal exclaimed that some fishermen “took on that Coast [of Vigo, Spain] a Sort of Monster, or Merman, 5 Feet and a Half from its Foot to its Head, which is that of a Goat.”Footnote 6

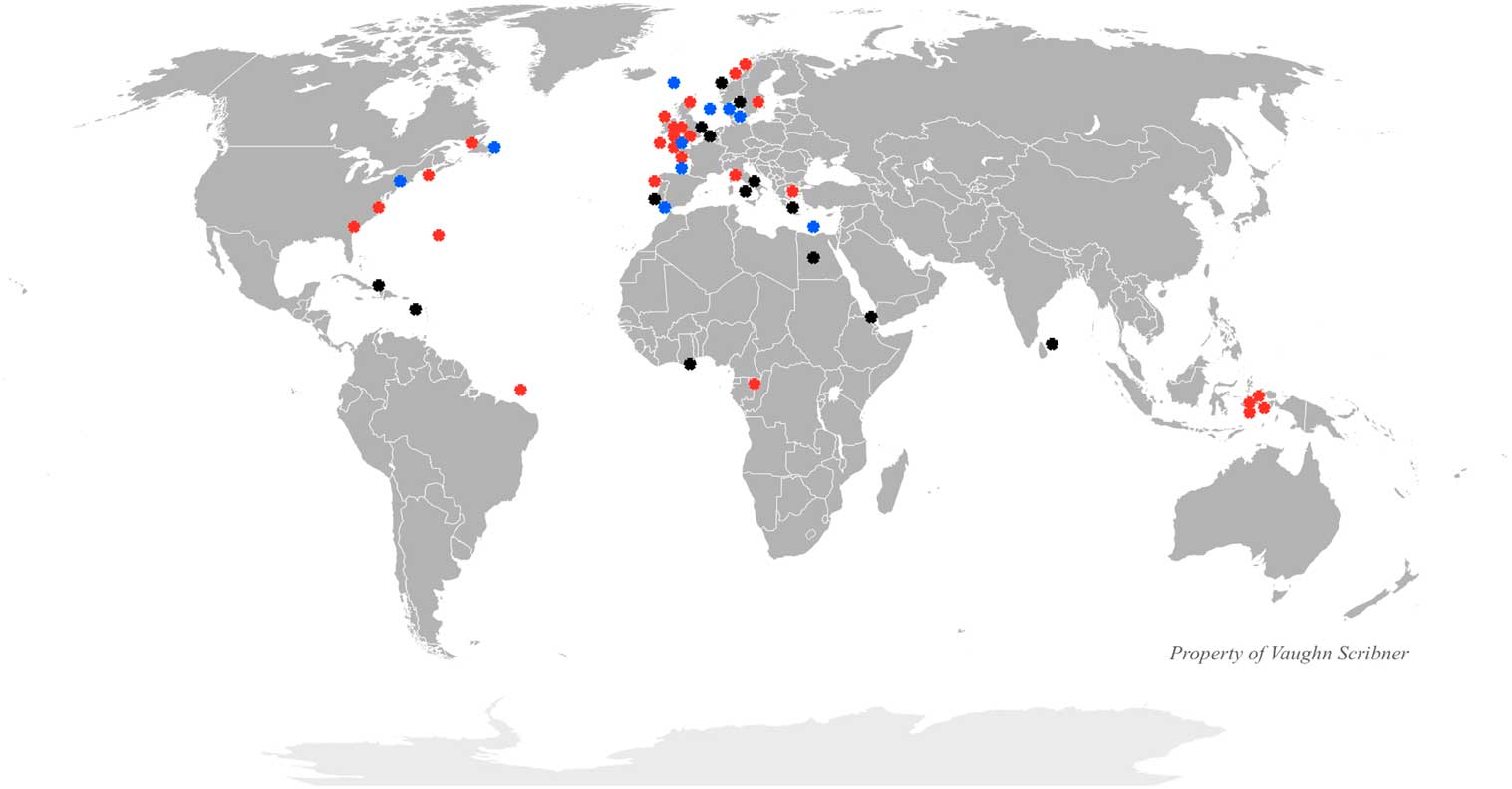

Though not accounting for every mermaid and triton sighting reported in eighteenth-century British and British American newspapers, the above examples are representative of what an early modern Briton would have found in the rag linen. (See figure 2 for a map of sightings.) That these interactions were even reported in the newspaper tells us much. Respected philosophers like Benjamin Franklin considered such encounters legitimate (and interesting) enough to spend the time and money to print in their widely read newspapers. By doing so, printers and authors helped sustain a narrative of curiosity surrounding these wondrous creatures. As a Londoner sat down with his newspaper (perhaps in the aptly-named Mermaid Tavern) and read yet another instance of a mermaid or triton sighting, his doubt might have transformed into curiosity.Footnote 7

Fig. 2 “Mapping Mermaids.” Map of every available (source-verified) European-reported mermaid sighting between 1400 and 180; Created by Vaughn Scribner.

For many newspaper readers throughout the British Empire, this was exactly the case—by the eighteenth century, amateur scholars took to their local newspapers to debate the existence of merpeople. One Bostonian wrote to the Boston Evening-Post in 1762, “I find by your Paper…that you are willing…to entertain your Customers, with such natural curiosities as are the most remarkable.” This author, who dubbed himself “W.X.,” tackled the question of whether mermaids and mermen were, in fact, real. W.X. began his piece by addressing “some of the greatest naturalists” who contended that mermaids and tritons “took their rise from an imperfect view of a Sea-Cow.” Laughing this notion off, the Bostonian argued that a sea cow was “so far from having any likeliness of the human species” that it could not be linked to a mermaid or triton. Merpeople, for this Boston gentleman, were far more likely to have deep connections with humankind. W.X. proceeded to record “a few” of the “many proofs…that there are such animals as Mermaids, &c.” He referenced various publications in his point-by-point analysis, ranging from scholarly books to magazines to travel narratives. Realizing that his argument would “not be sufficient to prevent many from ridiculing [his assertions] as spurious,” W.X. ended his article with an exact copy of the English Captain Richard Whitbourne’s account of a mermaid off the coast of Newfoundland in 1610. Whitbourne described the “strange Creature” in extreme detail, noting that its facial features made it “beautifull,” with a “well proportioned” body and “blue strakes” of hair on its head. Yet as the creature attempted to board the ship, the crew beat it away with oars and fled the scene. Because the authenticity of this “ancient narrative” was “unimpeached,” W.X. hoped that it would silence any doubters of the existence of merpeople once and for all. Of course, it did not.Footnote 8

Across the Atlantic Ocean, a writer asked the editor of the British Apollo in 1710 whether he believed the spate of merpeople sightings pouring into England during the last few centuries. After going into considerable detail on a mermaid who washed up on shore in Holland in 1503 and was then taught to act like an upstanding Christian by local villagers, the poster pleaded, “Now, Gentlemen, I wou’d desire you to inform me, of the credit of [the Holland mermaid story], and whether the being Mermen and Mermaids is not a meer Fable, for I cannot persuade my self to believe there ever were such Creatures.” The editor replied first by insisting that the story of the Holland mermaid “is Attested by Historians of so good Credit, that it wou’d be Injustice not to believe them.” He continued to note, “there can be no doubt made but that there are such Creatures as Mermaids, being frequently mentioned by Ancient Writers under the Name of Tritons and Syrens.” Like W.X., the editor then provided a thorough investigation of merpeople sightings, particularly that of a triton off the coast of France in 1636. Having described the triton sighting in extreme detail, the editor exclaimed, “We thought it wou’d not be unpleasant to give this Story at large to the Reader, since it is from an Author of undoubted Credit, and may serve not only to conform our Belief that there are such Creatures, but also to give us an Idea of them.” For this editor, the case was closed—if only it were that simple.Footnote 9

Despite the surplus of merpeople sightings in the eighteenth century and a long tradition of belief, most naturalists continued to deride those who entertained the existence of such creatures. As early as 1668, the Englishman John Wilkins produced An Essay Towards a Real Character, and a Philosophical Language for the Royal Society of London in which he sought to provide definitions of every creature in the animal world. But “as for fictitious Animals, as Syren, or Mermaid, Phoenix, Griffin…&c.,” Wilkins contended, “there is no provision made for them in these tables, because they may be infinite; and besides, being but bare names, and no more, they may be expressed as Individuals are.” Twenty-two years later, John Locke echoed Wilkins when he exclaimed “there neither were, nor had been in Nature such a Beast as an Unicorn, nor such a Fish as a Mermaid.” Thomas Boreman began his 1740 discussion of mermaids by remarking that these creatures “seem rather to be Creature of [Ancient Writers, Statuaries and Painters’] own Invention than any real Production of Nature,” while Benjamin Martin took a more levelled approach to discounting mermaids, contending “The Stories of Mer-Maids…had undoubtedly their Original from such Animals as have in some Respect a Likeness to the human Shape and Features.” He continued, “Among these the Monkey Kind, the Orang Outang, and the Quoja Morron, are the chief on Land, and the Fish call’d the Mermaid (tho’ it has nothing of the Human Form) [figure 3] and some other unusual Animals in the Sea.” By the final decade of the eighteenth century, the author of The Naturalist’s Pocket Magazine believed that the seal was “the true and sole foundation of the Mermaid,” while John Stewart, in The Revolution of Reason, asserted that a mermaid was none other than a “fabulous animal” with a possibility of existence “so distant, that they merit the discriminatory term futile ideas.” If the ever-growing community of philosophers and naturalists were ever going to entertain the thought of merpeople, a more scientific approach to these “fabulous” creatures was absolutely necessary.Footnote 10

Fig. 3 Pierre Boaistuau, Certaine Secrete Wonders of Nature (London: Henry Bynneman, 1569), 47.

Global Networks of Exchange: Cabinets of Curiosity and the Republic of Letters

Though volumes abounded on monstrosities and creatures such as merpeople by the eighteenth century, a naturalist might also have the chance to see a (dead) mermaid or triton specimen in person.Footnote 11 Filled with mysterious items ranging from “unicorn horns” (later discovered to be narwhal tusks) to coconut shell goblets to fossils to specimens of animal and human monsters, “cabinets of curiosities” served as symbols of power and enlightenment for European gentlemen. Mermaid parts, unsurprisingly, often joined other curiosities in these “wonder rooms.” While visiting such a collection in Amsterdam in the early eighteenth century, the French philosopher Maximilien Misson “observ’d among other things…The hand of a Mermaid.” Among the “curiosities” listed in Middlesex, England in 1713, similarly, was “The Rib of a Triton (or Merman),” while Mr John Tradescant of London kept “the hand of a mermaid” in his seventeenth-century private museum. According to the Dutch philosopher, Isaac Vossius, finally, the town of Copenhagen kept a mermaid’s skeleton on display after 1644. Combined with European global exploration, such collections only reinvigorated interest in merpeople. As historian Harriet Ritvo contends, merpeople, like other curiosities, “were part of a range of apparent exceptions that might, if they were genuine and if they were properly understood, help define the limits of biological possibility.” A new frontier of natural science waited in the depths of the oceans.Footnote 12

In an expanding number of investigations into mermaids and tritons, naturalists demonstrated a growing propensity for the wondrous. They also, importantly, revealed how the process of scientific research had drastically changed over the last 200 years. Rather than rely strictly on ancient texts and hearsay, eighteenth-century naturalists mustered various “modern” resources—global correspondence networks, erudite publication opportunities, transatlantic travel, specimen procedures, and learned societies—to rationally examine what many considered wondrous. Thus, a growing body of gentlemen both carried on and eschewed the supposed narrative of enlightened logic: they applied well-known, valid research methods to mysterious, largely derided merpeople. In doing so, philosopher-collectors complicated our—and their contemporaries’—conceptions of science, nature, and humanity.

As early as 1676, Thomas Glover, “an Ingenious Chirurgion [Surgeon]” who had lived in Virginia “for some years” submitted his description of a merman sighting to the Royal Society. In describing Virginia’s various rivers, Glover exclaimed, “I shall here insert an account of a very strange Fish or rather a Monster, which I happened to see in Rapa-han-nock River.” As Glover’s craft arrived at a calm estuary, the rest of his crew went ashore, leaving the naturalist to read a book. Yet the surgeon noted he “had not read long before I heard a great rushing and slashing of the water, which caused me suddenly to look up.” To Glover’s amazement, “about half a stones cast from me appeared a most prodigious Creature, much resembling a man, only somewhat larger, standing right up in the water with his head, neck, shoulders, breast, and waste, to the cubits of his arms, above water; his skin was tawny, much like that of an Indian.” Boasting a “pyramidal” slick head, large black eyes and eyebrows, a gaping mouth (with accompanying moustache), and a mid-section resembling a man’s, the triton’s countenance was “grim and terrible.” The creature circled Glover’s ship, staring down the scared Englishman. As a trained surgeon familiar with both human and animal anatomies, Glover concluded his account by remarking, “At last [the triton] shoots with his head downwards, by which means he cast his tayl above water, which exactly resembled the tayl of a fish with a broad fane at the end of it.” Hardly considering Glover’s account fictitious, the Royal Society published it in their Philosophical Transactions. After reading Glover’s account in 1750, one English author contended, “This Creature seems to be the Mermaid or Merman, supposed to be half human and half a Fish, the Reality of which many Persons have doubted; but their Existence is too well attested to be denied.”Footnote 13

Glover was not the only man to witness a merperson in the New World. On 5 July 1716, Cotton Mather penned a letter to the Royal Society. The Boston naturalist often sent letters abroad detailing his scientific findings. Yet this letter’s subject was somewhat curious—titled “a Triton,” the missive demonstrated Mather’s sincere belief in the existence of merpeople. The Royal Society fellow began by explaining that, until recently, he considered merpeople no more real than “centaurs or sphynxes.” Mather found myriad historical accounts of merpeople, ranging from the ancient Greek, Demostratus, who witnessed a “Dried Triton…at ye Town of Tanagra,” to Pliny the Elder’s assertions of the existence of mermaids and tritons. Yet because “Plinyisums are of no great Reputation in our Dayes,” Mather noted, he passed off much of these ancient accounts as false. Mather’s “suspicions” of the existence of such creatures “had got more Strength given,” however, when he read the accounts of well-respected historical figures such as Monal (prefect of Mauritius), Bellonius (Pierre Belon), and Gillius (Pierre Gilles). Mather found that sightings of mermaids and tritons were no longer relegated to ancient history—according to various volumes, a group of Englishmen had caught a merman off the coast of “Orford of Suffolk…in ye Reign of K. John,” a mermaid had been dragged ashore and trained to knit near Edam, Holland in 1404, and the Englishman, Captain Richard Whitbourne witnessed a mermaid while exploring Newfoundland in 1610. Still, Mather was not totally convinced, at least until 22 February 1716, when “three honest and credible men, coming in a boat from Millford to Brainford [Connecticut]” encountered a triton. Having heard this news firsthand, Mather could only exclaim, “now at last my credulity is entirely conquered, and I am compelled now to believe the existence of a triton; for such a one has just now been exhibited in my own country, and the attestations to it are such that it would be a fault in me at all to question it.” As the creature fled the men, “they had a full view of him and saw his head, and face, and neck, and shoulders, and arms, and elbows, and breast, and back all of a human shape…[the] lower parts were those of a fish, and colored like a mackerel.” Though this “triton” escaped, Mather was totally convinced of its existence—and that of other creatures like it. Maintaining that his story was not false, Mather promised the Royal Society that he would continue to relay “all New occurrences of Nature.”Footnote 14

In 1743, the English botanist Peter Collinson also delved into the world of merpeople, writing to Sir Hans Sloane of the Royal Society with news that his friend, Sylvanus Bevan (of London) had acquired “a great rarity…a Maremaid Hand and arm.” Collinson explained that Bevan had procured this arm while sailing off the coast of Brazil, when “Something like Human came and threw its arm…over the [ship’s] gunnel” and a crew member hacked the creature’s arm off. The creature receded into the water, leaving “the Maremaids arme” behind for Bevan, Collinson, and Sloane’s inspection. Yet Sloane had to wait until 1747 to see the arm, when “Mr Bevan shew’d the Bones of the arm of a Fish resembling the arm and hand of a man…found on the Coast of Brazil” to the inquisitive Royal Society.Footnote 15

The famous naturalist (and colleague of Collinson), Carl Linnaeus, also threw himself into investigating mermaids and tritons. Having read newspaper articles detailing mermaid sightings in Nyköping, Sweden, Linnaeus sent a letter to the Swedish Academy of Science in 1749 urging a hunt in which to “catch this animal alive or preserved in spirits.” Linnaeus admitted, “science does not have a certain answer of if the existence of mermaids is a fact or is a fable or imagination of some ocean fish.” Yet in his mind, the reward outweighed the risk, as the discovery of such a rare phenomenon “could result in one of the biggest discoveries that the Academy could possibly achieve and for which the whole world should thank the Academy.” Perhaps these creatures could reveal man’s origins? For Linnaeus—a philosopher world-renowned for his contributions to natural classification—this ancient mystery had to be solved.Footnote 16

Besides sending letters around the globe, eighteenth-century philosophers exchanged travel narratives detailing mermaids and triton sightings. Take the English traveller, John Josselyn, for example. Although some of Josselyn’s assertions “must have lifted the eyebrows of his most credulous follower,” as one historian contends, Josselyn’s Account of Two Voyages to New-England had gained notoriety in scientific circles by the eighteenth century.Footnote 17 The intrepid traveller’s report of a merman, consequently, probably piqued the interests of men like Mather, Linneaus, and Collinson. In a story startlingly similar to Mr. Bevan’s, one Mr. Mittin told Josselyn of his violent encounter with a triton in the early seventeenth century. Apparently Mittin, a “Gentleman” and a “great Fouler,” was hunting from his boat in Casco Bay, Maine, when a triton began to board his craft. Mittin quickly hacked off its hand with a hatchet: “the Triton presently sunk, dying the water with his purple blood, and was no more seen.” Perhaps expecting credulity from his readers, Josselyn closed by noting “the saying of a wise, learned and honourable Knight, that there are many stranger things in the world, than there are to be seen between London and Stanes.” Such a statement would have rung true with eighteenth-century philosophers. The world and its oceans, after all, rendered new discoveries with every passing day. Who was to say that merpeople might not be next?Footnote 18

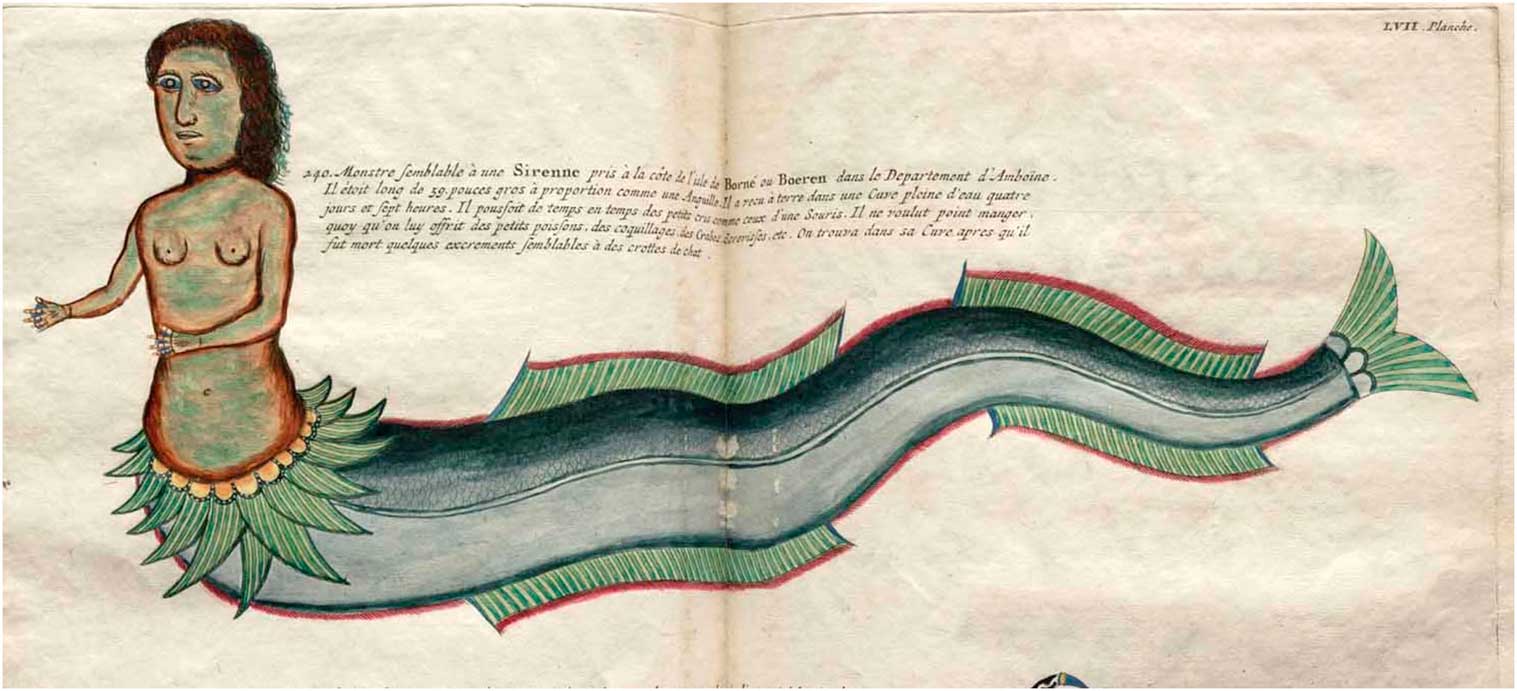

The Dutch artist Samuel Fallours also claimed to have discovered merpeople in a distant land. Fallours lived in Ambon from 1706 to 1712 while serving as a clergyman’s assistant for the Dutch East India Company. During Fallours’ tenure on this Spice Island, he drew various representations of native flora and fauna. One image (figure 4) happened to depict a mermaid, or “sirenne.” Fallours’ sirenne closely resembled the classic depiction of a mermaid, with long, sea-green hair, a pleasant face, and a bare midsection that turned into a blue-green tail at the waist. This mermaid’s skin, however, was dark (with a slight greenish tinge), implying a similarity with the local natives.Footnote 19

Fig. 4 “Sirenne,” in Louis Renard, Poissons, Ecrevisses et Crabes (Amsterdam: Reinier & Josué Ottens, 1719). Reproduced with permission of the University of Glasgow Library.

In the notes that accompanied Fallours’ original drawing, the Dutch artist contended that he “had this Syrene alive for four days in my house at Ambon in a tub of water.” Fallours’ son had brought it to him from the nearby island of Buru “where he purchased it from the blacks for two ells of cloth.” Eventually, however, the whimpering creature died of hunger, “not wishing to take any nourishment, neither fishes nor shell fishes, nor mosses or grasses.” After the mermaid’s death, Fallours “had the curiosity to lift its fins in front and in back and [found] it was shaped like a woman.” Fallours claimed that the specimen was subsequently relayed to Holland and lost. The story of this Ambon siren, however, had only just begun.Footnote 20

Before Louis Renard, a French-born book dealer living in Amsterdam, ever published a version of Fallours’ “Sirenne” in his own Poissons, Ecrevisses et Crabes (1719), Fallours’ images had already enjoyed wide distribution. Yet, because of the unusually bright colours and fantastic creatures represented in Fallours’ drawings, many doubted their accuracy. Renard was especially worried about the validity of Fallours’ “Sirenne,” exclaiming, “I am even afraid the monster represented under the name of mermaid…needs to be rectified.” The bookseller utilized the republic of letters “for clarification,” sending “some copies to Batavia and Ambon to have them verified.” He promised prospective readers “if it happens that it is necessary to change something, I feel I am obliged to notify the public.” The stakes got even higher in 1716 when Czar Peter I of Russia and his wife, Catherine I, visited Renard’s bookshop and viewed Fallours’ mermaid image. Catherine remained unconvinced that Fallours had harboured a mermaid, and demanded that Renard find proof of this monster. Renard quickly sent a letter to two of Fallours’ acquaintances: François Valentijn, a Dutch minister who was friends with Fallours’ supervising preacher, and Abrahamus Parent, the head minister of the Dutch Reformed Church at Ambon during Fallours’ tenure on the island.Footnote 21

Both men were little help. Valentijn declared that he was “not a witness to the event that [Renard] describe[d],” and had not “heard of it until today,” while Parent informed Renard that, while he met Fallours at Ambon, he was unfamiliar with Fallours’ captive mermaid. As a consolation prize of sorts, both men provided Renard with explanations of their own random encounters with merpeople. But Renard did not need other mermaid tales. He needed proof of one mermaid, and he simply could not get it.Footnote 22

Philosophers found both promise and disgust in Fallours’ painting and the subsequent dialogue that Renard initiated with his frantic letters. In his preface to the 1754 version of Renard’s Poissons, Ecrevisses et Crabes, the Dutch collector/director of the menageries and “Natuur- en Kunstkabinetten des Stadhouders,” Aernout Vosmaer, declared that “the mermaid deserves more attention than is generally given. Its existence is positively asserted.” Vosmaer continued by calling objections to merpeople’s reality “weak,” and contending that “this monster, if we must call it by this name (although I do not see the reason for it)” was simply able to avoid humans’ traps better than any other creature (because of its hybrid nature) and was thus rarely seen. Because of merpeople’s biological similarity to humans, furthermore, Vosmaer argued that they were “more subject to decay after death than the body of other fishes.” Such a lack of preservation also diminished sightings (and full specimens in cabinets of curiosity). Renard’s work, as historian Theodore W. Pietsch contends, demonstrated how “describers of nature, particularly scientific illustrators, were developing a greater concern with exact, precise representations of living things.” Renard based his detailed investigations upon “direct observation and reason,” which was in line with Enlightenment approaches to philosophical inquiry. His choice to include a mermaid, however, rankled some of his erudite colleagues.Footnote 23

The English naturalist Emanuel Mendez da Costa—a member of the Royal Society who professed a dedication to “the passionate pursuit of Nature”—was far less impressed with Fallours’ (and, by proxy, Valentijn and Renard’s) work. In a 1776 review of the most recent scholarship on conchology, da Costa called Valentijn’s Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën (1724–26) “a curious but not a scientifical work.” Especially damning in da Costa’s opinion was Valentijn’s decision to include “a fine figure of a Mermaid as vulgarly painted” among “two large, or sheet plates, wherein he has figured some sea plants, and some fish.” “This ridiculous circumstance alone,” da Costa grated, “has degraded [Valentijn’s] work among the too lively collectors.”Footnote 24

Collinson did not share da Costa’s disgust for a combination of proven science and speculative merpeople research. In 1755, he wrote to the Gentleman’s Magazine reciting Captain Richard Whitbourne’s 1610 mermaid sighting off the coast of Newfoundland. As a member of the Royal Society and a well-respected naturalist, Collinson’s opinion would have held real weight in the scientific community. Thus, when Collinson prefaced the Whitbourne sighting with his own prose, contending, “There are still many people who doubt the existence of the Mermaid, and perhaps with good reason, yet all natural historians deliver it as a fact, and the many relations of navigators of credit should not be wholly disregarded,” people would have listened. More than anything, Collinson’s 1755 submission to the Gentleman’s Magazine—a periodical read throughout the English-speaking world—provides a succinct snapshot of how midcentury European academics grappled with the science of merpeople. Though many “doubt[ed] the existence of the Mermaid…with good reason,” they also had to come to terms with the myriad sightings by trusted “navigators of credit,” as well as the fact that “all natural historians deliver [merpeople] as fact.” Although Collinson wrote this piece twenty-one years before da Costa damned Valentijn’s work, furthermore, this article was closely correlated with da Costa’s 1776 review, for it ignited a flurry of subsequent scientific studies of merpeople in the pages of the Gentleman’s Magazine (and other erudite publications) over the next half century. By publicly announcing his belief in merpeople, in short, Collinson inadvertently(?) marked the beginning of a wave of mermaid and triton studies in the Atlantic world. When taken this way, da Costa’s quick rejection of Valentijn’s work seems much less representative of the larger scientific community.Footnote 25

From Sightings to Science: Publications and Humankind’s Marine Origins

By midcentury, a growing number of philosophers not only believed in the existence of merpeople, but also began to wonder what sort of ramifications such creatures might have for understanding humanity’s origins. As G. Robinson noted in The Beauties of Nature and Art Displayed in a Tour Through the World (1764), “though the generality of natural historians regard mermen and mermaids as fabulous animals…as far as the testimony of many writers for the reality of such creatures may be depended upon, so much reason there appears for believing their existence.” The Reverend Thomas Smith took Robinson’s contention to an even more final note four years later, exclaiming while “there are many persons indeed who doubt the reality of mermen and mermaids…yet there seems to be sufficient testimony to establish it beyond dispute.” Smith, like Robinson, W.X., and the editor of the British Apollo before him, subsequently listed a long (and well-versed) history of mermaid and triton sightings by notable figures. But the problem remained—men like Robinson and Smith could only rely upon ancient, often ridiculed, sightings for their “proof.” They needed scientific research to back up their claims. And they got it.Footnote 26

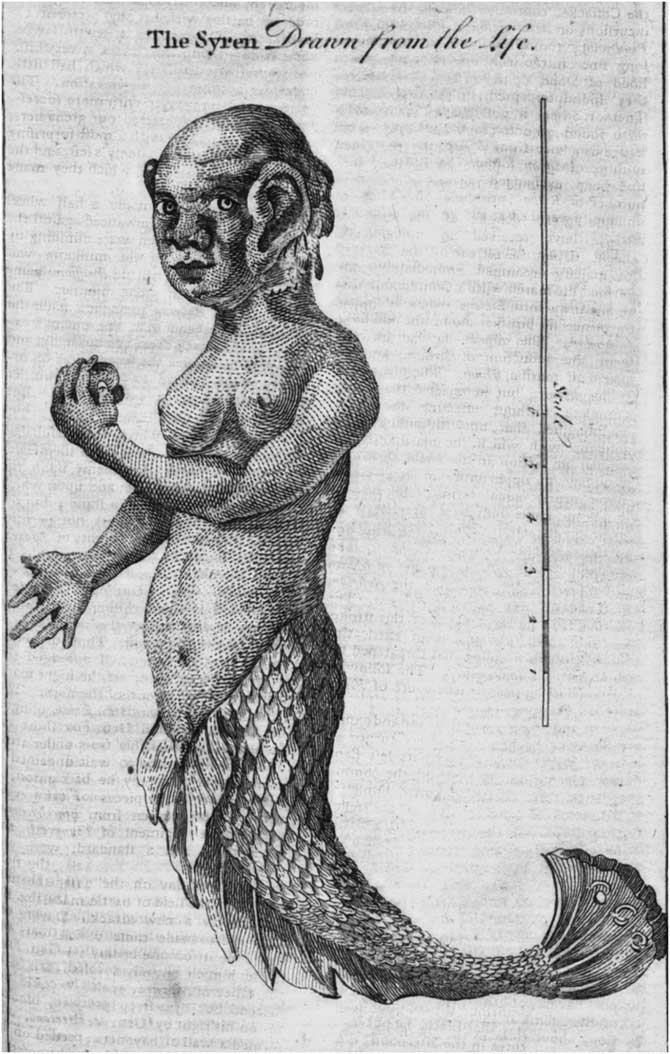

Three especially important articles—each approaching merpeople through unique scientific methodology—appeared in the Gentleman’s Magazine between 1759 and 1775. The first piece, published in December 1759, accompanied a plate image of a “Syren, or Mermaid…said to have been shewn in the fair of St. Germains [Paris]” in 1758 (figure 5). The author noted that this siren was “drawn from life…by the celebrated Sieur Gautier.” Jacques-Fabien Gautier, a French printer and member of the Dijon Academy, was widely recognized for his skill in printing accurate images of scientific subjects.Footnote 27 Attaching Gautier’s name to such a strange image gave the print immediate credibility. Even without Gautier’s name, however, the print and its accompanying text were distinguished by their modern scientific methodology. Gautier had apparently interacted with the living creature, finding that it was “about two feet long, alive, and very active, sporting about in the vessel of water in which it was kept with great seeming delight and agility.” And though Gautier noted that the creature was friendly as its onlookers fed it bread and small fish, he also remarked that such actions were only “the attention of mere instinct.” For Gautier, this creature was an exotic beast that necessitated close scientific investigation.Footnote 28

Fig. 5 “The Syren Drawn from Life,” in Sylvanus Urban, Gentleman’s Magazine for December 1759 (London: D. Henry, 1759), 600.

Gautier consequently recorded that “its position, when it was at rest, was always erect. It was a female, and the features were hideously ugly.” As illustrated in detail by the accompanying print, Gautier found its skin “harsh, the ears very large, and the back-parts and tail were covered with scales.” According to the image, this was not the mermaid that had long graced cathedrals throughout Europe. Nor did it match the description relayed by so many other naturalists and discoverers throughout history. Where they had seen a beautiful female form, distinguished by flowing blue-green hair, Gautier’s mermaid was completely bald with “very large” ears and “hideously ugly” features. At only two feet tall, Gautier’s siren was also much smaller than traditional mermaids. More than anything, Gautier’s mermaid reflected the mid-eighteenth century approach to studying the wondrous aspects of nature. The Frenchman had employed well-respected scientific techniques—in this case a close inspection of the creature’s anatomy and an “accurate” accompanying illustration (much resembling those of other creatures at the time)—to display as hard reality what many still considered fantasy.Footnote 29

Gautier’s assertions made waves in the British scientific community. An anonymous contributor to the June 1762 issue of the Gentleman’s Magazine exclaimed that Gautier’s image “seems to establish the fact incontrovertibly, that such monsters do exist in nature.” But this author had further evidence. An April 1762 edition of the Mercure de France reported that in June 1761 two girls had “discovered, in a kind of natural grotto, an animal of a human form, leaning on its hands” while playing on a beach in the island of Noirmoutier (just off the southwest coast of France). In a rather morbid turn of events, one of the girls stabbed the creature with a knife and watched as it “groaned like a human person.” The two girls then proceeded to cut off the poor creature’s hands “which had fingers and nails quite formed, with webs between the fingers,” and sought the aid of the island’s surgeon, who, upon seeing the creature, recorded: “it was as big as the largest man…its skin was white, resembling that of a drowned person…it had the breasts of a full-chested woman; a flat nose; a large mouth; the chin adorned with a kind of beard, formed of fine shells; and over the whole body, tufts of similar white shells. It had the tail of a fish, and at the extremity of it a kind of feet.” In this author’s opinion, such a story—when verified by a trained and trusted surgeon—only further proved Gautier’s research. For a growing number of eighteenth-century Britons, merpeople existed, bore a striking resemblance to humans, and needed to be studied at length.Footnote 30

Finally, in May 1775 the Gentleman’s Magazine published an investigation of a mermaid “taken in the Gulph of Stanchio, in the Archipelago or Aegean Sea, by a merchantman trading to Anatolia” in August 1774. Like Gautier’s 1759 “syren,” this specimen (figure 6) was drawn and described in detail. Yet the author also separated himself from Gautier, noting that his mermaid “differs materially from that shewn at the fair of St. Germaine, some years ago.” In an especially interesting turn of events, the author utilized a comparison of the two mermaid prints to speculate on issues of race and biology, contending “there is reason to believe, that there are two distinct genera, or, more properly, two species of the same genus, the one resembling the African blacks, the other the European whites.” While Gautier’s siren “had, in every respect, the countenance of a Negro,” the author found that his mermaid displayed “the features and complexion of an European. Its face is like that of a young female; its eyes a fine light blue; its nose small and handsome; its mouth small; its lips thin.” Where the previous two authors had used the science of precise description, verification, and illustration to prove the validity of their specimens, in short, the 1775 writer took comparisons with humans one step further by inserting modern ideas of race and biological difference.

Fig. 6 “The Impression of the Character,” in Sylvanus Urban, Gentleman’s Magazine for May 1775 (London: D. Henry, 1775), 217.

Further investigation of this comparison is necessary. The author contended that Gautier’s mermaid—with her “very large” ears, broad nose, and “hideously ugly” features—resembled “the countenance of a Negro.” His own specimen, meanwhile, boasted “fine light blue” eyes, a “small and handsome” nose, and a small mouth with “thin” lips, and thus supposedly embodied “the features and complexion of an European.” Though only one among many images of African women existing at the time, Francois Le Vaillant’s “Woman from Caffraria” (figure 7) well demonstrates an eighteenth-century European’s biased interpretation of African femininity. As historian Jennifer L. Morgan has shown, early modern English writers leaned on two main stereotypes to commodify and denigrate African female bodies. First, they “conventionally set the black female figure against one that was white—and thus beautiful.” Here, this 1775 author followed perfectly in line, comparing Gautier’s “negro” and “hideously ugly” mermaid to his own beautiful mermaid with the “features and complexion of an European.” Second, early modern Europeans concentrated on African women’s supposed “sexually and reproductively bound savagery”—especially notions of their abilities to constantly suckle their various children—in order to ultimately turn to “black women as evidence of a cultural inferiority that ultimately became encoded as racial difference.” Note the large breasts of both Gautier and Le Vaillant’s women. While Gautier’s mermaid is not associated with a child, her large breasts infer that she could indeed nurse a child quite adequately. Le Valliant, meanwhile, depicted his subject with a suckling child. The 1775 mermaid, however, is shown as having small breasts, which might have symbolized what English naturalists considered an important racial difference between white and black women: white women, with their supposedly smaller breasts and lower tolerance for physical pain were allegedly more civilized than African women who, with their purported larger breasts and higher pain barrier, could birth and raise children without any pain (like “savage” animals). Not only were naturalists using the science of merpeople to gain a deeper understanding of the natural order of sea creatures, but they were also utilizing their interpretations of these mysterious beings to reflect upon humans’ place in the ever-changing racial, biological framework.Footnote 31

Fig. 7 “Female Caffree,” in Francois Le Vaillant, Travels from the Cape of Good-Hope, into the Interior Parts of Africa, vol. 2 (London: William Lane, 1790), 263.

The Gentleman’s Magazine was not the only eighteenth-century British publication to embrace the scientific study of merpeople. One contributor to the November 1758 edition of The Scots Magazine, for example, analysed two prints of a “real Mermaid,” related by the Frenchman, John Barbot “in his [late seventeenth-century] voyage to Congo river…in the lakes of Angola, in the province of Massingan.” Called “woman-fish” by the Portuguese and “syrene” by the French, these creatures apparently “abounded” in the waters surrounding colonial settlements in Africa. The contributor to the Scots Magazine explained that such creatures “are found both male and female, of various sizes; the largest about eight feet long, with short arms and hands, but long fingers, which they cannot close, because they are webbed.” When one of these mermaids poked its oval head out of the water to feed on grass, it revealed a face with a high forehead, flat nose, wide mouth, and no chin or ears. Yet, most importantly, the author provided two detailed images—one (figure 8) of the mermaid “when laid upon her back” and another (figure 9) that “shows her as she swims in the water.” While the creature in figure 9 resembled a manatee, with a non-descript body and a somewhat humanoid face, the subject of figure 8 closely resembled popular descriptions of merpeople. These two images were ultimately scientific explanations for detractors who contended that mermaid sightings were actually manatee or seal sightings. When viewed from above, this mermaid looked every bit the manatee. But when turned over for close scientific enquiry, it indeed matched traditional descriptions of mermaids and tritons with a naked midsection, humanoid breasts, and a fish-like tail. In the author’s contention, these images, combined with various mermaid sightings through history (especially Captain Richard Whitbourne’s 1610 account, which the author deems “the most authentic [mermaid sighting] that has yet been given”), convinced the author that “it were an unpardonable incredulity not to believe…the reality of such monsters.”Footnote 32

Fig. 8 “Mermaid When Laid Upon Her Back,” in The Scots Magazine for November 1758, vol. 20 (Edinburgh: Sands, 1758), 588.

Fig. 9 “Mermaid as She Swims in the Water,” in The Scots Magazine for November 1758, vol. 20 (Edinburgh: Sands, 1758), 588.

Scientific research of merpeople was hardly limited to erudite journals. The French naturalist, Benoit de Maillett, penned the Telliamed (1748) in which he attempted to “relate man to geology and [geology] to the universe.” De Maillett deemed the ocean wholly responsible for the geographic and geologic structure of the earth’s surface. His contention that such processes occurred over billions of years, furthermore, broke new scientific ground, as no one had published any sort of model encompassing such a vast period. Yet de Maillett’s assertion of “the marine origin of the human races” received the most critical attention. In de Maillett’s telling, plants, animals, and humankind originated in the waters of the ocean. As the ocean steadily receded (part of an endless process of flooding and drying), the continents revealed themselves. Plants, animals, and humans consequently moved onto this new land, becoming “terrestrial” through “a generalized and continuous process of transformism.” According to de Maillett’s model, mermaids and tritons were not only real, they were humanity’s ancestors. Like so many others, de Maillett provided readers a vast history of mermaid and triton sightings throughout space and time, promising “I shall reject anything which may be considered as a product of the imagination of poets and only relate well-documented facts.” Reflecting Mather’s earlier assertion that naturalists did not trust Pliny’s tales of merpeople, de Maillett mentioned that he had chosen to omit “Pliny, who is perhaps unjustly called a liar.” De Maillett believed Pliny’s oft-ridiculed tale of a triton playing the flute, adding his own scientific contention that the triton’s “music, to be sure, could not have been very delicate and harmonious since he was probably blowing with his mouth into a perforated reed.” Having combed through these “strange…but so authenticated” accounts with a critical eye, the French philosopher concluded that they “are such proofs as the marine origin of the human races that, in my opinion, they are sufficient to demonstrate such a truth to persons less prejudiced in favour of another imaginary origin than most of the terrestrial people.” In de Maillett’s opinion, religion had blinded too many to the aquatic origins of humankind. Adam might have existed, but his ancestors had been mermaids and tritons.Footnote 33

Such a model was, unsurprisingly, both controversial and exciting. Certain orthodox naturalists lashed out at de Maillett’s anti-religious theory. In his L’histoire naturelle éclaircie dans une de ses parties principals, la conchyliologie (1757), for instance, the French philosopher Dezallier d’Argenville exclaimed, “What a folly in this author to substitute Telliamed for Moses, to bring man out of the depths of the sea, and, for fear that we should ascend from Adam, to give us marine monsters for ancestors! Only a kind of godlessness could invent such dreams.” Yet others lauded de Maillet’s work: Voltaire recognized the Telliamed as an important model for his own conceptions of Earth’s history, while seventy-two of France’s 500 libraries stocked the book (making the Telliamd—the palindrome of “de Maillet”—the sixth most popular volume in French libraries in the mid-eighteenth century). By borrowing and expanding upon general theories from ancient authors such as Lucretius, Epicurus, and Herodotus (not to mention various Arabic writers), de Malliet not only reconfigured Europeans’ understanding of the geological origins of the world, but also provided context and justification for myriad mermaid and triton sightings. Merpeople, in his telling, fit perfectly with the geological, natural, and scientific history of humankind and the earth.Footnote 34

Erik Pontoppidan—Bishop of Bergen and member of the Royal Academy of Sciences at Copenhagen—built upon de Maillet’s work in his Natural History of Norway (1752–53). Realizing that certain readers might “suspect [him] of too much credulity” when they arrived at his section on mermaids and other sea creatures, the Nordic naturalist remarked, “I am content patiently to submit to their censure, till they have read the chapter through, and then I flatter myself that I shall have no need of an apology.” Pontoppidan began his investigation by admitting, “most of the accounts we have had of [merpeople] are mixed with meer fables, and may be looked upon as idle tales.” When story tellers represented the merman “as a prophet and an orator” or depicted the mermaid as “a fine singer,” Pontoppidan continued, “one need not wonder that so few people of sense will give credit to such absurdities; or that they even doubt the existence of such a creature.” Yet, in Pontoppidan’s theory, when one cut through the “idle” stories and “fictions” with scientific analysis, the truth of merpeople revealed itself.Footnote 35

Especially important for Pontoppidan’s investigation was the belief that each creature on land had its equivalent in the sea.Footnote 36 “It is well known,” Pontoppidan argued, that sea-horses, sea-cows, sea-wolves, sea-hogs, and sea-dogs that “bear a near resemblance to the land animals” inhabit the depths of the sea. “Though this should be allowed as reasonable,” he continued, “some may make objections, founded upon self-love, and respect to our own species.” Pontoppidan realized that, as in the case of de Maillett’s unorthodox thesis, many would find fault in thinking that any other creature could resemble man, “the lord of all creatures…[created in] the image of God.” Yet the bishop continued his research, supposedly finding proof of his assertions with the existence an African “Wood-man” who seemed to have been “produced from the intercourse between a man and an ape, or an ape and a woman.” Pontoppidan went into extreme detail on every mermaid and triton sighting in and around Norway he could muster, ultimately concluding that, no matter the unorthodox nature of his findings, they were scientifically viable, if not proven. For this philosopher, science and religion could exist harmoniously.Footnote 37

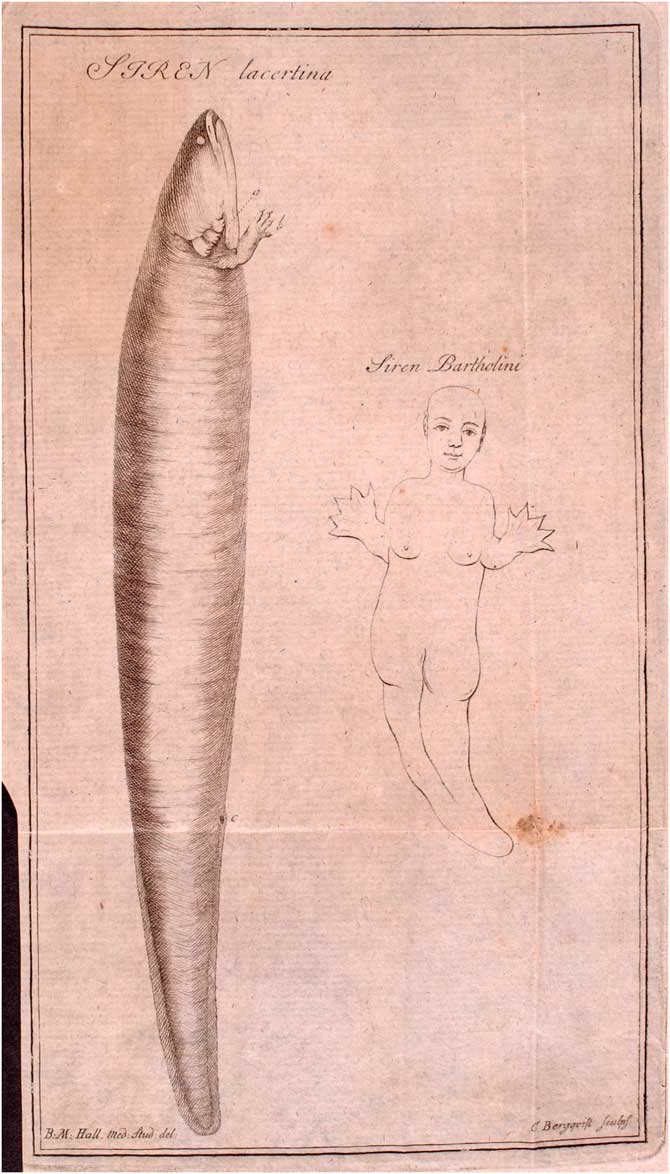

Eighteen years later, Carl Linnaeus and his student, Abraham Osterdam, further complicated the story. Though the Swedish Academy found nothing in their search for Linnaeus’s mermaid in 1749, Linnaeus and Osterdam took matters into their own hands by publishing Siren lacertina, dissertatione academica orbi erudito data in 1766. Having detailed a long list of mermaid sightings throughout history in the initial pages of this dissertation, they next relayed myriad instances of “marvelous animals and amphibians” that closely resembled creatures of lore and, consequently, made classification tricky. Such explanations led Linnaeus and Osterdam to their investigation of a man in South Carolina who held a creature very much resembling a mermaid. The purpose of the dissertation was to understand this mysterious creature termed Siren lacertina, or greater siren. Living in the swampy climate of South Carolina, the creature apparently sounded like a duck, but with a cry more “sharp and clear.” Dissection revealed that the being harboured “lungs and gills” within its chest (bridging the gap between mammal and fish), a fish-like tail where its legs should have been, and small arms jutting from its torso (figure 10). Though not as humanoid as the seventeenth-century Danish physician Thomas Bartholin’s description of a mermaid (figure 10), this “siren” nevertheless exhibited clear characteristics of what many eighteenth-century citizens would have considered a merperson. Linnaeus and Osterdam accordingly went into extreme detail in their investigation of the animal, employing modern dissection methods to categorize and understand everything from the creature’s small teeth to its “flat…depressed” head to its anus (which apparently stopped at its tail). Ultimately, they judged this mermaid-like creature “worthy of an animal, which should be shown to those who are curious, because it is a new form.” The “father of classification” had, apparently, discovered a “worthy” piece of the natural puzzle, and it linked humans (even if distantly) to amphibious merpeople-like creatures.Footnote 38

Fig. 10 “Siren Lacertina and Siren Bartholini,” in Carl Linneaus and Abraham Osterdam, Siren lacertina, dissertatione academica orbi erudito data (Uppsala, 1766), 17. Reproduced with permission of the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation.

Linnaeus had originally set out looking for a merperson that would have more closely resembled Bartholin’s representation. The mere possibility of the existence of a creature exhibiting the upper body of a human and the lower body of a fish had led Linnaeus and many other European philosophers on a global journey that demanded the most up-to-date scientific methodologies. While many of his peers attested to having discovered beings that closely resembled mermaids and tritons of lore, the Swedish physician ultimately found a specimen that only faintly resembled the popular image of a merperson. His Siren lacertina did not have the head and torso of a human being, nor was its tail as clearly fish-like as those merpeople who adorned the pages of the Gentleman’s Magazine. Nevertheless, Linnaeus and Osterdam had uncovered a new creature in the backcountry of South Carolina, and it did indeed exhibit certain characteristics—namely human-like arms, complicated internal organs like lungs and an anus, and the ability to live both on land in the water—that led them to determine that this “siren” was the closest thing to merpeople that they had come across. The Siren lacertina also, importantly, further blurred the lines of classification that Linnaeus had so proudly developed, suggesting that perhaps human beings might find some distant relation to amphibious creatures.

Conclusion

Eighteenth-century philosophers’ investigations of merpeople represented both the endurance of wonder and the emergence of rational science during the Enlightenment period. Once resting at the core of myth and on the very fringes of scientific research, mermaids and tritons steadily caught philosophers’ attention. Initially such research was relegated to newspaper articles, brief mentions in travellers’ narratives, or hearsay, but by the second half of the eighteenth century, naturalists began to approach merpeople with modern scientific methodology, dissecting, preserving, and drawing these mysterious creatures with the utmost rigor. By the close of the century, mermaids and tritons emerged as some of the most legitimate specimens for understanding humanity’s marine origins. The possibility (or, for some, the reality) of merpeople’s existence forced many philosophers to reconsider previous classification measures, racial parameters, and even evolutionary models. As more European thinkers believed—or, at least, entertained the possibility—that “such monsters do exist in nature,” in short, Enlightenment philosophers merged the wondrous and rational to understand the natural world and humanity’s place in it.