In September 1961, approximately two thousand Indians who had settled in Mozambique and professed Hinduism gathered in their community centre in Lourenço Marques, the colony's capital city, to pay tribute to Adriano Moreira, the Portuguese Minister of the Overseas Territories. The Portuguese propaganda machine covered this event, emphasising that, despite the “unjust” and “intolerable” aggressions by the “Indian Union,” its nationals were allowed to live and work in Mozambique without being targets of reprisal.Footnote 1 The aggressions in question targeted the Portuguese State of India (Estado Português da Índia, hereafter referred to by the acronym EPI), which extended over an area of 3,700 square kilometres and comprised three small and geographically discontinuous territories: Goa, Daman, and Diu.

Following the liberation/occupation of the EPI by India on 18 December 1961, this situation would change dramatically. The political measures introduced by the Portuguese authorities in the aftermath of the Goa crisis were overtly presented as aimed at protecting lives and assets; however, the Indian nationals established in Mozambique immediately became the target of reprisals and bargaining chips in Portugal's attempts to leverage the negotiations with Indian authorities. Specifically, the Portuguese colonial state first confined Indian citizens in internment camps and took judicial action to freeze and confiscate their assets; subsequently it ordered that such assets be liquidated, and the Indian nationals deported.

Whilst the political and diplomatic features of the Goa crisis have received considerable scholarly attention, its aftermath in colonial Mozambique remains a neglected subject.Footnote 2 In-depth and systematic research on this topic still remains a mere desideratum. Only a handful of studies have explored the impact of these political measures and the different ways in which men and women of Indian origin who had settled in this territory experienced the conflict between Portugal and India. However, the available literature suggests that the lives of Indian nationals were severely affected as a result of these events.Footnote 3

This exploratory article focuses on the Portuguese colonial policy that targeted Indian nationals settled in Mozambique following the fall of Portuguese India. It also addresses the views, concerns, and responses developed by Indian nationals to cope with political measures such as expropriation and expulsion. Our intent is to highlight how the colonial management of Indian minorities in Mozambique evolved from a long-standing duplicitous attitude, encompassing suspicion and persecution but also a strategic economic and political rapprochement, to an even more ambivalent approach in the wake of the political crisis in Goa, with the implementation of retaliatory policies professed as humanitarian in nature. We will argue that ambivalence also characterised the manner in which men and women of Indian origin related to the Portuguese colonial power and responded to its governance.

The case study presented in the present article relies upon written historical records and oral sources, which are addressed with a combined quantitative and qualitative methodology. In order to shed new light on the policy that targeted Indian nationals—its design, implementation procedures, and impact—the systematic evaluation of published primary sources, specifically the legal regulations and official proclamations issued in the Boletim Oficial de Moçambique (Official Bulletin of Mozambique) from December 1961 onwards, provided valuable material. The archival records of PIDE/DGS, the Estado Novo (New State) political police, offered further insights on the complexities, hesitations, and ambivalences surrounding the implementation of such policy.Footnote 4

The oral sources under analysis resulted from several distinct research projects on Indian migration to African territories, all of which actually featured the Goa crisis topic, either by design or by chance.Footnote 5 This article focuses particularly on the memories of Hindu men and women—a majority of Indian nationality—targeted by Portuguese retaliatory political measures in the aftermath of the Goa crisis. The interviews were carried out in Portuguese or Gujarati (especially in the case of older women), and followed a strong biographical orientation. This concurred to elicit both contexts, actions, and strategies, as well as information on how the interviewed subjectively experienced the events and constructed meaningful memories.Footnote 6 Our goal is to apply cumulative insights on their experiences of messiness, loss, trauma, and resilience in the aftermath of the Goa crisis. At the same time, we will attempt to keep in mind the dialectic processes of remaking colonial and postcolonial experiences, and attempt to avoid the simplistic reductivism of colonial memories to a postcolonial viewpoint.

The article is organised as follows: the first section provides a brief overview of the Indian communities in Mozambique during the second half of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, emphasising how the economic competition introduced by the growth of Indo-British firms triggered colonial measures to regulate their circulation and business activities. The second section introduces the political and diplomatic features that surrounded the conflict between the Portuguese and Indian governments. The third section offers an interpretative perspective on the underlying motives of the duplicitous governance policies targeting Indian citizens in the aftermath of the Goa crisis. The analysis then moves on to the differentiated impact of these policies amongst the Indian minorities inasmuch as they intersected with nationality, religion, and class differentials. Exploring the construction of Indian nationalism as a threat to the Portuguese colonial power, the next section suggests how identification and resistance could ambivalently coexist within male Indian/Hindu colonised subjects. The article then attempts to highlight a specific Indian/Hindu female narrative of the Goa crisis, which proposes alternative modes of conceptualising the relation between Self and Other, including their inherent power dynamics. The final section addresses the Indian nationals’ asset liquidation and deportation process, providing a quantitative overview of the implementation of the retaliatory measures.

Indians in Mozambique: A Brief Overview

Since the late seventeenth century, a considerable portion of the merchant activity in Mozambique was carried out by Hindu and Muslim traders from the Portuguese territories of Diu and Daman. Indian textiles were exchanged for ivory across the Indian Ocean following the establishment, in 1686, of the Company of Mazanes, which had exclusive rights to engage in commerce between Diu and Mozambique Island.Footnote 7 During the same period, a group of Catholic Indians from Goa, known as canarins, worked in the colonial administration or became land holders in Mozambique under a Portuguese lease regime.Footnote 8

Gradually, the Hindu Vanias (traders) of Diu were displaced by a number of merchants from the tiny princely state of Kutch, particularly Hindu Bhatias and Muslim Ismaili Khoja, who benefitted from their dominant role in the Omani state's trade and finance to extend their activities along the East African coast.Footnote 9 Many had followed the Sultan when, in 1840, he relocated from Muscat to Zanzibar, taking advantage of the growing ivory, gum copal, spices, and slave trade.Footnote 10 The numerous innovations these merchants introduced, namely, the increased volume of exchanges and a growing supply of new African products, as well as the establishment of long-distance enterprises and investment in banking activities, were rapidly replicated by other Indian businessmen in Mozambique during the second half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 11

Indians were legally recognised as British subjects after 1843; though they were never granted the status of full citizens,Footnote 12 they were entitled to travel to and reside in the territories under British rule, as well as in foreign territories which maintained diplomatic relations with Britain. In the mid-1880s and 1890s, however, this scenario changed, notably when the Boer Republics and the colony of Natal introduced restrictive measures against Indian immigrants. Fuelled by racial prejudice, anti-Indian feeling experienced a steady growth, spreading to other East African territories. Mozambique thus became an appealing alternative destination for Indians, despite the restrictive regulation issued in 1932 which aimed to limit Indo-British immigration into the Portuguese colony.Footnote 13

Since the commercial sector had diversified and offered opportunities for further expansion, the major economic interest of British migrants, whether Hindus or Muslims, was placed upon international trading operations. The import/export business was made possible by the development of transnational connections and exchanges which included India, the nuclei of co-ethnics settled in east and southern Africa, and other more profitable regions (e.g. China, Japan, England, and Portugal). Recently arrived migrants generally started out by working as clerks. With the support of their former employers, many became travelling salesmen. They bought goods on credit, exchanged them for produce supplied by local farmers, sold the produce to import/export firms, paid their debts, replenished their stocks, and once again returned to the bush. After some time, they would establish a cantina (a small general store, especially in rural areas). The increase in supplies from the farmers to the cantineiros enriched the warehouse owners and exporters, thus enabling them to expand their business.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, the consolidation of the colonial system in Mozambique also offered multiple economic opportunities for migration to Portuguese Indians. While most Hindu and Muslim migrants from Diu and Daman found employment in the construction industry and the cantineiro commerce, Catholic Goans were interested in taking up positions in the colonial administration and invested in the higher education of their offspring (sending them to Goa and Portugal), thus laying the foundations for middle-class professional diversification.Footnote 14

Though World War II interrupted some of the Indian import/export circuits, the firms which imported mainly from Portugal and the largest Indian money changers profited enormously. The Portuguese government remained neutral, which meant that many Portuguese trading ships were not disturbed during the conflict. Increased demand for certain goods on the part of the warring countries and the resulting price increases, and later the influx of foreign currencies into Mozambican ports, all contributed to an improvement of the economic status and social standing of some of the large family firms, such as Ranchordas Oddha & Co., Haridas Damodar Ananji & Co., Gorbandas Vallabdas & Co., Damodar Manglagy & Co., Dayaram Gopaldas & Co., Bhagwangi Kakhoobhai Co., Prabusdas Binji Co., Gulamhusem & Co., or Tharani & Co.Footnote 15

British Indians were often depicted as threatening economic competition by Portuguese settlers and government officials; despite this, the political understanding that large British Indian firms played a crucial part in Mozambique's economy inhibited the implementation of harsher legal constraints on their circulation and business activities. Additionally, until the independence of British India and its partition into two independent countries, India and Pakistan, on 14 August 1947, diplomatic imperatives also compelled the Portuguese colonial authorities to welcome a significant number of British Indian subjects to Mozambique. Coping with this delicate situation required the adoption of ambivalent measures. Accordingly, while the Portuguese authorities made efforts to curb the influx of British Indian migrants to Mozambique, they officially denied any hostility towards them.Footnote 16 Moreover, they came to share a similarly “ambiguous floating position” with the Catholic Goans, who participated in the “circles of power and ideological formation” but at the same time were kept out as “second class citizens”.Footnote 17 British Indian entrepreneurs had the recognition on the part of the governing classes that they were indispensable economic partners and promoters of Portuguese colonialist ideology, while constantly being reminded that they were “subaltern elites.”Footnote 18

The Goa Crisis: A “Deep Wound Inflicted to the Nation's Body”Footnote 19

Besides putting the EPI in a “position of great vulnerability,” British Indian independence in the aftermath of World War II was a strong indication that the international constellation in the postwar years would not favour the persistence of formal colonial empires.Footnote 20 Portuguese colonial rule came under mounting criticism, and Portugal also became increasingly isolated internationally. Unwilling to decolonise, the Portuguese response to such attacks, which inter alia questioned the legitimacy of governing overseas territories, was to deny the existence of a colonial situation and to embrace Luso-tropicalism in order to legitimise Portuguese colonial sovereignty.Footnote 21

Its meagre economic and strategic value notwithstanding, Portuguese India held a significant symbolic weight. Founded in 1505, it evoked the grandiose past of the Portuguese overseas expansion.Footnote 22 According to António de Oliveira Salazar, the head of the Portuguese dictatorship, the EPI was a “family jewel, owned by an old family of immense tradition,” as such, it had “to be kept in the family.” Additionally, Salazar was unwilling to give these territories away, as he feared this would eventually pave the way for other decolonisation processes, ultimately resulting in the collapse of the Portuguese Empire, an ideological pillar of the Estado Novo regime. Hence, the determination to keep Portuguese India and the refusal to negotiate a political solution led to a gradual deterioration of the political and diplomatic relations between Portugal and India, culminating in the Indian invasion and occupation of the EPI on December 1961.Footnote 23

Whilst it is beyond the scope of this article to provide a detailed account of the political and diplomatic conflict in which India and Portugal became embroiled for thirteen years,Footnote 24 it is important to highlight some of its key aspects. Shortly after the establishment of diplomatic relations between Portugal and India, a memorandum issued by Indian representatives on 27 February 1950 requested the opening of negotiations in order to discuss a peaceful, political solution for the future of the Portuguese colonies in India. The Portuguese government rejected such a discussion outright. In January 1953, India reaffirmed this proposal and the Portuguese once again refused to engage in negotiations vis à vis the future of the EPI. As a result, later that year, in June, the Indian ambassador to Portugal left the country.Footnote 25

The following year, India increased pressure on the Portuguese state. On 25 July 1954, Indian forces occupied the enclaves of Dadra and Nagar Haveli. The Indian government also implemented an economic blockade, banned the import and export of weapons and ammunition, and imposed travel restrictions on Portuguese officials throughout the Indian Republic. During 1955 the situation escalated further, as the satyagrahis Footnote 26 promoted peaceful marches across Goa, which were brutally repressed by the Portuguese authorities. As a result of the increasing tension, diplomatic relations between Portugal and India were terminated. From 1956 to 1960, tensions between the two states apparently decreased, the occurrence of several attacks in Portuguese border areas that targeted police stations and military forces notwithstanding. These were followed by Portuguese repressive and retaliatory actions.Footnote 27

On 22 December 1955, Portugal filed a formal complaint with the International Court of Justice in The Hague against India regarding the Dadra and Nagar Haveli enclaves—only days after Portugal was admitted to the United Nations. On 12 April 1960, the International Court of Justice acknowledged the Portuguese right to cross Indian territories to reach the enclaves of Dadra and Hagar Aveli. The Portuguese state celebrated the decision and exploited it for propagandistic ends as a victory against the Indian state. On 11 August 1961, in disregard of the verdict, India annexed these territories by law. Moreover, shortly thereafter Jawaharlal Nehru, the Indian Prime Minister, launched the prospect of a military takeover of Goa in a public speech. Tension heightened between September and December 1961. The Portuguese Foreign Office—under the leadership of the diplomat Franco Nogueira—received increasingly alarming reports that India was mobilising to take Goa, Daman, and Diu by force. Although aware of Indian invasion plans, the Portuguese government believed that Nehru's pacifist ideology would lead him to avoid armed confrontation and military occupation.Footnote 28

The year 1961 was an annus horribilis for Salazar's Estado Novo. The regime had to cope with several crises—including the outbreak of the liberation war in Angola earlier that year—and was increasingly isolated in the international arena. Nonetheless, the Portuguese government undertook intense diplomatic efforts and a media offensive to counter the Indian threat.Footnote 29 Besides employing the rhetoric of national victimisation before a vilified enemy, the Portuguese press often highlighted the reversal of the Indian and Portuguese roles in the conflict. The newspaper Diário de Lisboa claimed in 1961 that Nehru cited his own clean record and pointed his finger at Salazar and his colonial regime. The newspaper went on assert that in the case of Goa “Any reasonable person would say that Nehru is the aggressor and Salazar the defender of the Portuguese territories.”Footnote 30

Neither diplomatic efforts nor military action prevented the loss of the EPI. On 17–18 December 1961, India carried out “Operation Vijay,” an attack and occupation of Portuguese India—by land, sea, and air—with no less than forty thousand troops. The territories were quickly overrun and Governor-General Manuel António Vassalo e Silva surrendered on 19 December 1961, to avoid a massacre of the Portuguese troops.Footnote 31 During five months, the Indian government confined about 4,500 individuals in internment camps—namely members of the Portuguese military who had surrendered, alongside a few notable civilians.Footnote 32 The Portuguese Empire's precious “family jewel” was lost, and not unlike the occupation of the Dadra and Nagar Haveli in 1954, this loss was felt in Portugal as a “deep wound inflicted on the nation's body.”Footnote 33 From the point of view of this article, this traumatic event set the stage for the reprisals that would soon target Indian citizens in Mozambique.

The Aftermath of the Goa Crisis: Using the Lives of Indian Citizens As Weapons Against the ‘Enemy’

According to the 1955 Mozambican census, in addition to 11,044 Indo-Portuguese, a total of 4,191 foreigners of Indian origin holding British, Indian, Pakistani, or South African passports were residents of Mozambique.Footnote 34 Following the invasion of the EPI, the Portuguese government deliberately leveraged Indian citizens in the difficult negotiations with Indian authorities, as they became targets of reprisal.

These measures, however, were not a direct reaction to the invasion and occupation of the EPI, and were prepared before the event. On 11 December 1961, considering the impending Indian attack on the EPI, the Overseas Ministry asserted that leverage was required to negotiate the liberation of possible Portuguese prisoners, and consequently put Indian citizens under surveillance and their “interests under control,” further asserting that preparations should be made for their timely internment.Footnote 35

By 15 December 1961, the PIDE delegation in Mozambique was already preparing a list of the Indian nationals who were to be confined in internment camps.Footnote 36 By then, PIDE was equally aware of the rumours that circulated in Mozambique regarding the possibility that certain groups within the white population might carry out retaliatory actions against Indian citizens if the attack on Goa took place. The rumours even suggested that the African population would take part in such reprisals, enticed by white Portuguese merchants, who saw this as a unique opportunity to rid themselves of their competitors. It was also reported that Indians, regardless of their nationality, geographical origin, or religious affiliation, were distressed and apprehensive, as they were receiving threatening anonymous letters and phone calls.Footnote 37 To clarify this situation it is worth noting that PIDE emphasised that Mozambique's “population would like to see interned and expelled any and all individuals, regardless of their nationality, commonly known as ‘monhés.’”Footnote 38 Therefore, it is highly probable that this combined to fuel a sense of uneasiness amongst Indian communities.

Aware of this situation, the governor-general of the colony, Manuel Sarmento Rodrigues, ordered district administrators and native chiefs to protect the personal integrity of all Indians, asserting that any violence against them would harm Portuguese national interests by providing the nation's enemies with reason for further criticism.Footnote 39 On 18 December 1962, the colonial government of Mozambique ordered the administrative internment of Indian nationals.Footnote 40 The Office of the Minister for the Overseas Territories, arguing that “urgent action was required to prevent the loss of property belonging to the subjects of the Indian Union,” also ordered Indian nationals’ assets to be frozen, not only in Mozambique but across all Portuguese colonies.Footnote 41

On 17 January 1962, a legislative order issued by the Mozambique general government stipulated that assets belonging to Indian citizens were to be “judicially confiscated.” In order to supervise the management and liquidation of the seized assets, the Mozambican government established the Comissão Coordenadora dos Assuntos Relativos a Bens Pertencentes a Súbditos da União Indiana (Coordinating Committee of the Indian Union Subjects’ Assets, hereafter referred to as the Coordinating Committee).Footnote 42 Finally, on 24 February 1962, another decree ordered the closure of all businesses owned by Indian nationals, as well as of companies that had shareholders with Indian passports.Footnote 43

As mentioned, the main goal of the Portuguese was to negotiate the exchange of Indian nationals for Portuguese nationals captured by India in Goa.Footnote 44 Accordingly, over 2,152 Indian citizens (including men, women, and children) were interned in ten camps in Mozambique, with the vast majority of the internees (1,623) held in the capital, Lourenço Marques.Footnote 45 Difficulties in determining who in fact amongst the Indian communities was an Indian citizen complicated the internment process.Footnote 46 Local authorities tended to perceive “Indians” mainly as a racial category, thus failing to recognise their distinct ethno-religious identities and their different statutes of citizenship and nationality.Footnote 47 In an interview, Gangaben Ramji suggested that there were cases of transnational families comprising members holding East African, South African, and Portuguese citizenship confined in these internment camps.Footnote 48 She also indicated that the citizenship of spouses and adult children were denied in favour of husbands’ and fathers’ political identification as Indian nationals.Footnote 49

My mother was born in Kenya and retained her British passport. When she became pregnant for the first time, she gave birth at her parents’ house in Nairobi. That's why my older brother had British citizenship… Due to conflicts between my grandfather's brothers, the family business broke up. My father then settled in Pretoria. To this day, my second brother has a South African passport. My father was always looking for opportunities in Mozambique. We were born in Lourenço Marques. When that [internment] happened, my father held an Indian passport. We lived in the internment camps for six months.Footnote 50

The national press, both in Portugal and Mozambique, underscoring the allegedly pacifist Portuguese stance in the conflict with India, claimed that there were humanitarian reasons for the internment order.Footnote 51 Hoping to conceal the strategic political dimension underlying such “detention,” colonial authorities also presented a similar version to the international press. They again emphasised the “humane treatment” of the internees confined to a new building near Lourenço Marques, even though they were “surrounded by barbed wire and guarded by a small contingent of armed soldiers”,Footnote 52 as vividly captured by Mozambican photographer Ricardo Rangel.Footnote 53 The internment of approximately one thousand children (whose fathers were of Indian nationality), most born on Mozambican soil, led colonial authorities to ensure that “nothing was lacking for mothers to conveniently take care of their children.”Footnote 54 The testimony of Himatlal Purushottan Modi, who was interned at the age of eight, is in part consistent with the existence of reasonable conditions in the internment camps; however, he also underlines how incarceration left a “profound mark”:

My parents had Indian passports and the whole family was sent to the internment camps, near what was called the Matadouro [Slaughterhouse]. We were given the basic conditions for survival, food, a health post. But we could not leave. We had schedules for everything. Later, the older boys, who were attending secondary school, were allowed to go to the Lyceum escorted by Portuguese soldiers. That left a profound mark on [me as] a child.Footnote 55

Diplomatic negotiations between India and Portugal were difficult; they began in early January and dragged on until May 1962, with Brazil acting as mediator. The Portuguese and Indian governments could not come to an agreement on the future of their respective detainees. India argued that its nationals interned in Mozambique should be released and allowed to remain in the territory. The Portuguese insisted on a different solution.Footnote 56 Salazar's political strategy was based on the expectation that the Indians arrested in Mozambique, driven by their wish to reclaim their assets and avoid deportation, would exert political pressure on New Delhi, leading Nehru's government to meet Portuguese demands, namely, the repatriation of Portuguese military personnel, the recognition of the Portuguese nationality for Goans who wished to obtain it, and the transfer of their movable assets and the value of their immovable property.Footnote 57 A compromise was eventually reached, whereby in May 1962, Indian citizens were released from the camps in Mozambique in exchange for the liberation of the Portuguese held in the former EPI.Footnote 58 However, in line with legislative decisions and several memoranda previously addressed to representatives of the Indian Republic, the Portuguese reiterated that the assets of Indian nationals were to be liquidated, since they had to leave Mozambique, along with their families, within a three-month timeframe.Footnote 59

The ambivalence of the Portuguese colonial state towards Indian citizens, supposedly granting them protection, yet using them as political weapons, was emphasised by several interviewees. The testimony of Govindji Purshutan stresses how the alleged “protection” was invoked to justify appropriation of their property and deportation.

My father told me that we were arrested because of some Portuguese extremists who wanted to attack us. The Governor said it was a protective measure for Indians. For Salazar, it was a way to guarantee the liberation of Portuguese soldiers. After that, they no longer needed Indian prisoners. They took our things and gave us a deadline to leave.Footnote 60

Beyond the Artificial Boundaries of Legal Citizenry: Ambivalent Alignments Towards the Multiracial Colonial State

Until Indian independence, all non-Portuguese Indians in Mozambique were considered British subjects and were issued documents accordingly. When India and Pakistan became independent, Indo-British subjects were encouraged to choose between obtaining documents as citizens of either state. Consequently, a significant percentage of Muslims acquired the Pakistani nationality, and most Hindus choose India. However, a number of them, especially among the large import/export operators and the official exchange agents of the regime, kept their British nationality while attending to their businesses in Mozambique. Moreover, a relatively high percentage of their children who were born in Mozambique were registered as Portuguese citizens, regardless of their parents’ nationality. For their part, many Sunni Muslims and Ismailis with Indian passports pursued naturalisation in Pakistan in the late 1950s, as well as immediately after the liberation/occupation of Portuguese India, since this was the only nationality that would enable them to obtain residence permits on Portuguese soil. The political alliance between Pakistan and Portugal, born of a common enmity against India, meant that Pakistani nationals settled in Mozambique were exempted from detention, confiscation of assets, and expulsion during the Goa crisis.Footnote 61

Holders of the British, Indian, Pakistani, or Portuguese nationalities, whether they belonged to the same or different religious communities, did not merely share cultural similarities, but also cross-generational daily interactions and exchanges in commerce and neighbourhood spheres, as well as interpersonal relationships fostered within the colonial school system in Mozambique. However, the Goan political crisis forced Indian Muslims to develop identity strategies of public visibility and instrumental affirmation of their distinct religious identity hand in hand with their newly obtained Pakistani nationality. Indeed, Sunni and Ismaili Muslims promptly displayed their political loyalty and solidarity towards Portugal. They also placed Pakistani flags outside their businesses and houses as well as posters saying “this is a Portuguese firm” or “Pakistan is grateful for Portuguese hospitality”Footnote 62 to stress the political identity boundary that distinguished Pakistanis from Indian nationals.Footnote 63

In interviews conducted with Pakistanis, ambivalence is discernible in remarks such as “they were not to blame” or “they were caught in a disagreement” or “many would have preferred that Portugal continued its rule,” when referring to Indian nationals. A leader of the local Muslim community even publicly declared his indignation at India's action against Portuguese India and Pakistan, as well as underlining his strong personal commitment to maintaining the ties between forcibly separated Indian family members and to helping them overcome difficulties related with their citizenship and identity documents. As his son recalls:

When there was a problem in the community and someone had to talk to the Governor, Amid went. My father helped many families who were detained in the internment camps. He was able to negotiate with the Governor so that there was contact between separated family members. Beyond that, he also helped internees with their documents. I remember it so well. We brought them food, clothes, medicine. We took young children to their parents. It was tragic, tragic. For a kid like me, Portuguese soldiers had arrested my best friends. Only later did I realise that it was for political reasons.Footnote 64

In contrast to Pakistanis and British Indians, the Indo-Portuguese did not publicly voice their political opinions with respect to “the loss” of Portuguese India, even though privately the majority “didn't want/were against the invasion” and continued to idealise the memories of Goa, Daman, and Diu “in the heyday of the Portuguese.” The integration strategies of Catholic Goans in Mozambique already involved the affirmation of the great similarities between their identity and that of the Portuguese—through language, clothing, and religious affiliation. Especially following the “invasion of Goa,” they sought to distance themselves from traits more easily identified as Indian.Footnote 65

Although the Portuguese colonial state tried to segregate Indian citizens in Mozambique, this isolation policy did not achieve the expected antagonistic effects. Rather, the Goa crisis fostered multiple solidarities between Hindus of Portuguese origin and Indian nationals (mainly of patel and lohana castes), which in this context mitigated the role of caste and class in shaping internal hierarchies in the Hindu community. As Lacxmi Premgi Bika recalls:

Every day, our patel neighbours cooked a little more to share with us. We were like a family. When that mess happened, they went to the internment camps. Their houses and shops were closed. But before that, they asked my father to bury all the precious things they had in our yard: gold, jewellery, money. He gave them everything back when they left. Our friendship was not forgotten. For many years, my mother poured milk and water over their pipero [sacred fig tree], praying for them and their ancestors.Footnote 66

The identification of Indian nationals as political “enemy aliens” did not prevent the emergence of feelings of anxiety in the colonial administration. Quite to the contrary, colonial anxiety was fuelled by “the suspicions about the identity and political allegiance of British and Pakistani passport holders.” The local government therefore also ordered that British and Pakistani citizens be “put under surveillance in case they revealed themselves to be ‘originally Indians’ by conducting prejudicial activities or favouring Indian interests.”Footnote 67

Regardless of their multinational citizenship, the families behind the large import/export Indian firms were protected and exempted from any restriction in their familial and economic lives, in spite of several disparaging comments expressed by smaller and medium-sized Portuguese traders. Accordingly, the descendants and former employees of these firms pointed out that the Goa crisis did not affect them. The deportation orders of Indian nationals who were managers and sub-managers of such firms were also deferred, since their departure would threaten Mozambique's economy.Footnote 68

To become a transnational trader or an importer/exporter/wholesaler engaged in money-lending and banking activities required Indians to identify with the historical project of Portuguese colonialism. At the same time, part of the governing classes were forced to recognise that Indian entrepreneurs were key political and economic partners in the development of the Mozambican colonial territory. Furthermore, as Hindu elites in Mozambique repeatedly emphasised in statements made on a national and international level, Portugal upheld the maxim of colonial “tolerance,” both in the “economic arena and in the cultural and religious sphere.”Footnote 69 Not unlike public discourses produced by other population segments in the Portuguese colonial context, such pronouncements colluded to foster Luso-tropicalism and Portugal's self-image as an equalitarian multiracial state that was allegedly a unique colonial power.Footnote 70

Kalyanji Bhagwangi Kakhoobhai, a prominent businessman in Mozambique and head of the Hindu community of Lourenço Marques, is an example of the ability to switch, by choice or constraint, between actively promoting the well-being of his familial and religious community and engagement in larger economic and political settings, though this was not without contradictions or ambiguities. In September 1961, at the height of the political crisis in Goa, he opened a ceremony at the Hindu community centre in Lourenço Marques to pay tribute to the Minister of the Overseas with the following words:

The Indian/Hindu community is not disinterested in what is happening. Even though racial harmony here is a fact, we are disturbed by certain biased statements issued by irresponsible individuals… There is a sentence in our Bhagavatam Guita that reads: “Truth in itself is victory.” And since reason and truth are on the side of Portugal, victory is guaranteed.Footnote 71

Addressing the Portuguese propaganda of “racial harmony” as a fact, Kakoobhai showcased the allegedly deeply pro-Portuguese stance of Mozambique's Hindu community in the conflict with India. Shortly after this statement, Portuguese colonial authorities bestowed upon him the important role of mediator in the non-official negotiations between India and Portugal on the future of Indian nationals in Mozambique and Portuguese prisoners in Goa.Footnote 72 Despite Kakoobhai's apparent commitment to the Portuguese colonial project, coercion was not absent in the recruitment process for such a hazardous mission. According to José Freire Antunes, Kakoobhai was recruited by Jorge Jardim, who confiscated alleged compromising documents that would incriminate him as a supporter of the invasion and occupation of the EPI, kidnapped his wife and son, and made Kakoobhai sign a letter of attorney, granting Jardim full possession of all his assets in Mozambique.Footnote 73

Kalyanji Bhagwangi Kakhoobhai's collaboration in the negotiations with India was therefore fostered by coercion. Moreover, he was also driven by community obligations, being often called upon by his peers when increasingly discriminatory Portuguese laws against Indian nationals were introduced in Mozambique. As Ranchordas Haridas notes:

I had Indian documents, my wife and children were all Portuguese citizens. It so happened that Hindustani managers were the last to receive the notification to leave [the colony]. As in my case. But in [19]62, a new law came into effect. Our Portuguese children were considered foreign aliens. My older sons left Mozambique with passports for illegal aliens. I was a rather privileged person to the extent that my wife's uncle worked for Kakoobhai, who had a lot of contacts among the embassies. Two years later, my older sons returned to Mozambique with Portuguese passports issued by the Brazilian embassy in New Delhi.Footnote 74

Colliding with the legal framework involving Portuguese nationality in which the jus solis principle prevailed, decree 44416, issued on 25 June 1962, withdrew the residence permits of all Indian citizens and revoked the nationality of their descendants born in the Portuguese territory.Footnote 75 From that point on, the children of Indian parents who held (previously obtained) Portuguese identity cards were suddenly considered aliens, and became effectively stateless subjects.Footnote 76 The revocation of the Portuguese nationality of children of Indian origin born on Mozambican soil brought to light how Portuguese colonialism ambivalently swayed between a rhetoric of integration and the segregation of its subjects.

Never Simply Complicit, Never Completely Opposed to the Coloniser: Male Indian Cross-Generational Narratives

In a speech before the Portuguese Parliament on 3 January 1962, Salazar stated that “the Goa case had its inception when the Indian Union became independent” and began “to regard itself as the true successor of England.” Furthermore, he added: “Nehru has plans for Africa, where he hopes that Indians may replace whites.”Footnote 77 The following section will explore the colonial construction of Indian nationalism as a threat to the Portuguese Empire in India and Africa by considering a number of Indian oral sources to yield significant insights.

Colonial sources often mention the Hindus’ unwillingness to interact with other communities and their reservations towards the Portuguese world. Conscious of their colonial resistance at the level of cultural practice, but also of the advantages that could accrue from their co-option as close collaborators of the regime, Hindus periodically gave the Portuguese state proof of their political subordination and respect for Portuguese institutions. What is more, contemporary colonial discourse defined them as detached from politics and lacking the impulse to exert religious influence over the native African population.Footnote 78 In the colonial mind, the Hindus’ adherence to their cultural and religious identity and refusal to be influenced or affected by others meant that they lacked an anti-colonial impulse to engage in attempts to convert Africans. Therefore, before the Goa crisis, Portuguese colonial authorities saw no reason for singling out Hindus for surveillance.

Although some authors underline East African Indians’ nationalist ideals and the relevance of their political participation, both before and after independence of the African colonies,Footnote 79 the available literature about Mozambique often emphasises their “community crystallisation” and predominantly “apolitical” stance.Footnote 80 Indeed, Indian oral sources describe the majority of Mozambican Hindus as “complying with the regime” or even totally extraneous to political issues; so much so that there is no “memory of any Hindu being arrested by PIDE.” According to these sources, the “refusal to get mixed up in politics” was the result of a higher investment in religious community, family life, and business, which was passed down through the generations. The following statement by Pradip Ratilal summarises these alleged attributes in a nutshell:

During colonial times, the typical Indian began by spending 4 or 5 years behind a counter, as a shop assistant, then started his own business, sometimes with the help of his boss. He sent his brothers and sons, to work with him. Indians were like that, they only trusted their relatives. Ten years old, and they were already employed in commerce. If they read at all, it was the front page of a newspaper. As a rule, they took no interest in politics. The few I met that did, two or three Goans, Aquino de Bragança, Óscar Monteiro and Sérgio Vieira… In Lisbon, I followed the student movements. The issue of the Colonial War was very important, and some already spoke of the independence of the colonies. This opened my horizons and set me apart from the Indians I knew in Mozambique… In 1973, I escaped to Sweden, and that was the first step towards engagement with Frelimo.Footnote 81

However, as hostility grew between Portugal and the Indian Union, this apparent “lack of interest” in politics became a problematic issue. The non-exteriorisation of the Indian way of thinking, associated with a notable ability to deceive the coloniser on any ideological level, fed “doubts” about the value of their political allegiances. “They appear to accept the opinion of the [Portuguese] interlocutor, even though they have one that is very well structured and absolutely contrary, leaving their interlocutor to doubt whether they really did adopt it with conviction or whether it was otherwise,” a Portuguese colonial officer stated in the late 1950s.Footnote 82

This (allegedly) Indian duplicitous performance generated “a crack in the certainty of colonial dominance,” as well as in its control of the Indian colonised mind. The menace did not necessarily lie in an actual conflicting political identity hidden behind a mask of compliance, but rather from the ambivalence induced in the colonial mind.Footnote 83 Hence, colonial authorities opted for horizontal surveillance, often using informants (including those of Indian origin) with whom they established relations of collaboration and exchange. As Gopaldas Mathuradas recalls:

There were infiltrators in all groups. Many Indians, mostly traders, were PIDE collaborators. Sudarji Carsane and Raviskankar, for example, had a good time with us. They provided information on what might be of interest or please PIDE in return for favours. The only Indian interest was business… Couto and Amorim, who worked in the colonial administration, often had lunch at our firm. We later discovered that they were PIDE informants. Their friendship and conviviality with us were false.Footnote 84

PIDE collaborators were ambivalently if not negatively represented, both by their handlers and the subjects targeted by surveillance. They played a significant role in the promotion of a persistent climate of mistrust, suspicion, and insecurity, which worked as a strategy of social control. Their “otherness” could be the target of political surveillance, or converted into a surveillance apparatus.Footnote 85 Haridas Bimji's testimony illustrates how the conflict between India and Portugal fostered a relational context between and within Indian communities as well as in the interethnic and interracial relations between Indians and Portuguese, which became highly ambiguous, making an assessment of the respective political alignments difficult.

My father was a person who had lived through a lot. He respected all races whatever their religion, but his intention was not to collaborate, nor to oppose the regime, it was a question of survival. Especially after the end of diplomatic relations [between India and Portugal], we had to be very cautious. It was hard to understand who was pro-Salazar and who was not, we could never trust [anybody].Footnote 86

Exposed to strong constraints, not unlike other colonial subjects, Indians simultaneously cooperated with and resisted Portuguese colonialism, even though their strategies may have only consisted in negotiating their survival in a limited field of options marked by repression and uncertainty. The following testimonies show how complicity and resistance could coexist in a fluctuating relation within Indian colonial subjects:

My father wanted the independence of the territories of so-called Portuguese India. He was persecuted by the colonial authorities [in Diu]. In 1952, he ran away to Vansoja near Una. My brothers and I, we studied in Diu, but we lived in ruins as refugees. In 1956, my father went to Lourenço Marques with the help of his older brother who was already there. My mother and we brothers arrived later… I finished commercial school there and went to work with my father in the tailoring business… I joined the Portuguese military service in [19]69. The day I swore allegiance to the Portuguese flag, my father was unable to hide his tears. I have never seen my father like that.Footnote 87

Navinchand described his father as being politically committed to independence for Diu, which is consistent with the prevalent memory that the origin of post-independence Indian nationalism lay mainly outside of Diu. Nonetheless, he insisted on his father's sense of responsibility towards family, stating that “having lost his right arm and only working with the left, he set up a tailor family business.” In addition, Navinchand's memories of his (almost impervious) father on the occasion of his swearing of the military oath seems to reveal the ambivalent mix of identification and opposition that often characterised the colonised subject: never simply complicit, never completely opposed to the coloniser.

My father was involved with the satyagraha, those nationalist followers of Gandhi who acted peacefully in the struggle for independence. So, to keep him from getting in trouble, my grandfather called him to work with him in the cashew business [in Mozambique]. In [19]61, my father did not say it openly, but he wished for the independence of Portuguese India. PIDE came to our house. They thought my father worked with military radars and acted as an informant [for India]. And yet, Toto [a PIDE agent] closed the store for 24 hours but then it reopened. PIDE was always trailing him because he was a régulo [a native chief] without being a régulo. Bambu, his African name, had the life he wanted. Mozambique was in his blood.Footnote 88

Lalichandra's testimony stresses his father's anti-colonial ideals towards British and Portuguese colonisers: “Goa, Daman, and Diu had been stolen from the Indians many years ago. The liberation was to give back to the owner what already belonged to him.” In his coherent description of his father, Lalichandra evokes his subsequent acts of resistance: “The Africans came to sit with him and he advised them [politically]; he wanted to free those people.” However, when questioned about his father's main identity, Lalichandra promptly says: “My father was proud to be Mozambican, indeed he gave much to his country, and at the same time he was also proud to be Portuguese, indeed more Portuguese than many others.” Lalichandra's description of his father's self-identity thus suggests that we should question the anticolonialist perception of resistance as the product of a binary, definitive, implacable identity in opposition to the coloniser.

Could the Subaltern Hindu Women Speak?Footnote 89

To what extent does the Goa crisis, as lived through and narrated by Hindu women settled in Mozambique, enrich our understanding of the power relations between Portuguese and Indians in the late Portuguese Empire? If we listen to their voices, it becomes clear that we are not dealing with anti-colonial female subjects who simultaneously resisted patriarchal community and family systems. Nevertheless, their testimonies raise interesting questions about suffering and survival in a context in which unequal power structures with regard to gender, race, and class were dominant both within their ethnoreligious communities and Mozambican colonial society. Hence, in line with Saba Mahmood, their testimonies will not be interpreted as examples of resistance to, subversion against, or reinterpretation of such power structures, but rather as a manifestation of their ability to express their voice, created and enabled by specific relations of subordination, which will be further analysed below.Footnote 90

Indian family relations, both in India and Mozambique, involved reciprocity and hierarchy. Parents invested in their children, trying to instil in them a perception of their moral responsibility to provide economic support for their parents in old age. Men had the task of guaranteeing material sustenance for their family; childcare, family relations, and religion were the primary responsibilities assigned to women. In each generation, all subjects were positioned as either hierarchically superior or inferior to other family members based on kinship and gender criteria. That said, the initial pattern of male migration (whereby wife and children remained in India) had provided a larger space within which women could expand their religious responsibilities. In Mozambique, due to the small number of Hindu temples and priests settled in the territory, many migrant women began to officiate, within their homes, at rituals that traditionally had been carried out by male priests. Apart from this ritual specialisation, they also recreated specific female traditions (linked to caste and lineage) for rites of passage and, independently of their caste and socioeconomic status, women opened direct paths of communication with the Hindu goddesses through rituals in which individuals were possessed by the spirits of goddesses. Their religious beliefs and performances thus emphasised the metamorphic and porous nature of all beings, as well as the mutable and reversible relations between them, thus renegotiating the distinction between the self and the other, which until then had been taken for granted.Footnote 91

Female testimonies regarding the political crisis of 1961 differ from those of male interviewees (of the same generation), both in the definition of the conjuncture itself as well as in the form and contents of the narratives. This difference is often explained by the statement that “Indian women didn't talk about business and politics,” which ascribes such domains to men. The testimony of Puriben Patel represents a typical female mode of narrating the past, in which family and religion constituted the sole basis around which they defined their identity and position:

After that mess [the Goa crisis], we returned to India only with the clothes on our backs. But we had God within us. What we did, he did it through us. At that time there was a movement of solidarity towards the Indians expelled from Mozambique. We were able to rent a house in Jamjotpur for 30 rupees. We often came to the mandir [the temple], we contributed as volunteers to the community, and then we solved our problems… In 1967, we returned to Mozambique. My eldest already owned a textile and clothing shop.Footnote 92

The separation and dispersal of the Indian extended family in the aftermath of the Goa crisis constitute a major narrative focus of female testimonies. As Lacxmi Popatbhai Radia explained: “Family unity was very important in the family business. People were doing everything for the family, to ensure that everyone got along.” Her narrative also exemplifies how expelled family members took residence in India or in other nuclei of the Hindu Gujarati diaspora in East Africa, thus stressing the importance of transnational family ties in times of crisis:

Our family was from Gujarat. My father began by opening a rural trading post, then a second one, until he became an importer/exporter. He always worked with his brothers. When that mess [the Goa crisis] happened, it was not our fault… My uncle Narendra fled to Tanzania because his wife had relatives there… The brother-in-law of my uncle Dipesh was a great trader in Nairobi and welcomed them. We went to the internment camps and after a few months we had to come back to Gujarat.Footnote 93

Especially from 1971 onwards, several expelled Indian citizens were granted permission to reunite with their Portuguese sons on Mozambican soil. By then, the PIDE/DGS branch in Mozambique acknowledged that the sons of Indian nationals had fulfilled their military duties by integrating the Portuguese Armed Forces and fighting in the colonial war, a circumstance that helped to expedite the authorisation of multiple family reunification processes.Footnote 94

According to the colonial construction of gender, the possible threat of support for insurgence was predominantly associated with men. Indeed, references to female Indian nationals are sparse in PIDE/DGS archival records on the Goa crisis. However, male Indian nationals, when interviewed by the Indian press on their arrival in Bombay, often cited examples of Hindu women as “victims” of Portuguese colonial governance, such as the detention “for thirty hours, of a woman whose baby had not been breastfeeding during this period” or the arrest of “an old widow with over thirty years of residence in Mozambique for not having left the Province.”Footnote 95

By contrast, other returnees reported that “individual Portuguese citizens did not forget the bonds of friendship developed over the years with Indians. They knew that Indian settlers were innocent and helped them in every way they could.”Footnote 96 Among the multiple examples of this claimed solidarity, one worth highlighting is the attempt made by a male (non-Indian) Portuguese national and a woman of Indian nationality to get married, so that the latter could acquire the Portuguese nationality. The woman was described as a widow who “had been living in Mozambique for many years, whose children had been born in the province, some of which had even completed military service,” and as “frail” and with no “relatives in India.” Authorisation for a civil marriage was denied, but the governor-general granted the woman annual permits, allowing her to stay in Mozambique.Footnote 97 Repeatedly featured in PIDE records, the civil marriage of female Indian nationals to Portuguese citizens of Indian origin also seems to have worked as an inter-family strategy to prevent women's expulsion from Mozambique.Footnote 98

Despite their invisibility within the Mozambican colonial context, the cultural and religious idioms through which our interviewees constructed their own selves and the alternative conceptions of the colonial world they passed down to the youngest generations reveal how Hindu women could speak:

Our mothers had a very sad life. Most men worked in Africa. They asked for loans from the Banyans who charged them high interest rates. Every two or three years, men returned to India, stayed for a maximum of six months or a year, got their wives pregnant and returned to Africa. Many men had African women. I know many Hindus with dark skin, including in my own family. In India, our women worked very hard and received only food as payment. They were enslaved, even sexually abused by the Banyans. Several women were also abused by Portuguese soldiers. I know children of those relationships. My mother told me that some ignorant soldiers even disrespected Shakti [the divine feminine creative power, also known as Devi]. They entered the Kankai Mata Mandir [near Diu] and removed the eyes of the Devi. When people went there and found that the eyes were missing and all that mess, they asked who had pierced the eyes of the Devi to a lady in whom Mataji descended. And she said: “The Portuguese soldiers did it.” She also said “the Devi was furious with the Portuguese and in a short time the independence of Goa, Daman, and Diu will come about.” And lo and behold it did, eight or nine months later.Footnote 99

Manorma's narrative suggests how performances of possession could be an outlet for vulnerable Hindu women to express their voice, as well as a scenario in which historical experiences of domination and/or violence could be addressed openly. As many other female interviewees recall, the cultural manifestations of suffering, protest, and resentment available to Hindu women were often expressed and understood in terms of their bodies, which were seen as particularly subordinate to the will of the Hindu goddesses. This turned possession performances into a privileged arena for the struggle against Indian women's vulnerability and subalternity: the possessed made demands and claims authorised by the female divine power itself.

The question of whether Hindu goddesses were anti-colonial or had any other potential for emancipation seems unproductive. What seems more meaningful is that female agency was enabled by a prevalent Hindu self-conception drawing on the instability of all beings, the porosity of their limits, and the illusion of hierarchical otherness, which provided the appropriate outlet through which female subaltern voices could be heard.Footnote 100

Repeatedly used by female interviewees to define the aftermath of the Goa crisis, the expression “that mess” alludes to the confusion and improvisation underlying the internment and expulsion process of Indian nationals. Although their main concern was the separation and dispersion of families, as well as material loss, the expression equally displays their difficulty in understanding the new categories of nationality, closely associated with religion, according to which Indian nationals were perceived as enemy aliens.

Targets of Reprisal: Asset Liquidation and Deportation of Indian Nationals

On 8 August 1962, a decree issued by the Governor-General of Mozambique stipulated that Indian citizens’ assets were to be liquidated and furthermore ordered Indian citizens and their descendants to be expelled from the colony.Footnote 101 Drawing on data from the Boletim Oficial de Moçambique (1962–1971), this section addresses the quantitative scope of the implementation of these two political measures.

Figure 1 provides an overview of this process. The blue and orange lines show the number of individuals who were ordered to liquidate their assets through official announcements and the actual liquidation operations over time, respectively, while the grey line brings residence permits issued in Mozambique to Indian descendants into the picture. These permits protected their bearers from state-sanctioned repression. Figure 1 also shows that, although the liquidation of Indian nationals’ assets continued until 1971, the majority of these measures were implemented between 1963 and 1964, in the aftermath of the Goa crisis.Footnote 102

Figure 1. The Reprisals: An Overview (1962–1971)

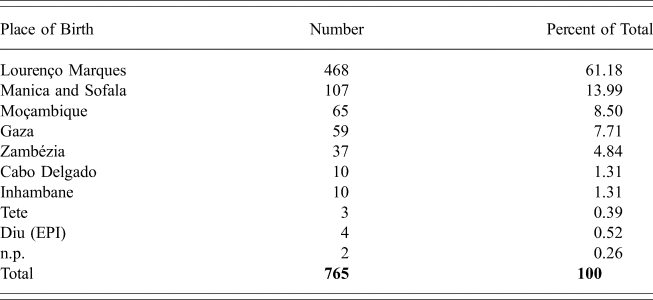

As well as individuals who owned and/or managed large import/export and money exchange firms, whose deportation was strategically postponed and/or annulled to protect Portuguese economic interests, those who were employed in public service or served in the Armed Forces were legally exempted from the policy measures under analysis.Footnote 103 In order to prevent the liquidation of their assets and deportation, however, the descendants of those Indian citizens who were potentially eligible to remain in Mozambique had to prove that they held Portuguese citizenship by undergoing a so-called “administrative justification” process. In other words, they were required to address a request to the Directorate of Civilian Administration Services of the General Government of Mozambique (Direcção dos Serviços de Administração Civil do Governo-Geral de Moçambique), along with evidence of Portuguese citizenship and a “certificate of good moral and civic behaviour” issued by administrative or police authorities.Footnote 104 Accordingly, between 1962 and 1971, 765 residence permits were issued to individuals by these services, granting them permanent residence in Mozambique and exempting them from the liquidation of their property (Table 1). Data analysis reveals that the overwhelming majority of these individuals were young males born in Mozambique (99.2%), especially in Lourenço Marques (61.18%) (Table 2).

Table 1. Residence Permits Issued (1961–1971)

Source:Boletim Oficial de Moçambique, series 2.

Table 2. Place of Birth of Recipients of Residence Permits

Source:Boletim Oficial de Moçambique, series 2.

The Coordinating Committee,Footnote 105 the institution in charge of managing the liquidations, administered eight sub-commissions, created between October and November 1962, with headquarters in the following districts: Zambezi, Mozambique (Nampula and António Enes), Gaza, Manica and Sofala, Tete, and Inhambane.Footnote 106 Our research shows that, from 1962 onwards, 1,446 asset liquidation announcements were issued by the commissions, for the most part during 1963–1964 (78.56%) (Table 3). Individual property was especially affected, with 84.02 percent of the announcements targeting personal assets, against 15.98 percent directed at collective entities, that is, stock companies owned by Indian citizen as shareholders (Table 4). At the same time, between 1963 and 1965, seventy-nine of these liquidation procedures were terminated prior to being completed. In some cases, the procedures were begun due to administrative error, as the individuals targeted were not Indian nationals. In other cases, the people in question had acquired Portuguese, Pakistani, or even South African passports in the meantime, which exempted them from the reprisals.Footnote 107

Table 3. Liquidation Announcements

Source:Boletim Oficial de Moçambique, series 2.

Table 4. Liquidation Announcements (per type of entity)

Source:Boletim Oficial de Moçambique, series 2.

Although the outcome of asset liquidation is a subject that calls for further investigation, our research allows for a synthetic overview. At the beginning of the process, besides the taxes due in connection with regular commercial and financial operations, the Portuguese state would collect an additional 5 percent of the patrimonial value of the assets, once their liquidation and sale had been completed. Only a part of the amount would revert to its previous owner, following the determinations of the Fundo Cambial (the colony's exchange fund commission). The remaining capital was to be deposited and frozen in the Banco Nacional Ultramarino (Overseas National Bank), to the order of the Mozambican government. Then, after three years, it would revert in favour of the Portuguese state.Footnote 108

Between 1962 and 1971, while the low value of some of the assets liquidated might have precluded their being published in the Boletim Oficial de Moçambique, about 543 liquidation operations were included in the data (Table 5).Footnote 109 The transfer of the assets of small- and medium-sized commercial firms constituted an overwhelming share of the liquidation operations (52.67%), followed by immovable property such as urban real estate and agricultural lands (40.70%, see Table 6).

Table 5. Asset Liquidation

Source:Boletim Oficial de Moçambique, series 2.

Table 6. The Assets

Source:Boletim Oficial de Moçambique, series 2.

Finally, the data analysed offers an overview of the Indian nationals most severely affected by the liquidation procedures (Table 7) and reveals that the buyers of such property were overwhelmingly Pakistani and Indo-Portuguese (Table 8). The data is consistent with oral testimonies, highlighting that the Indian citizens who were most affected by the liquidations were the great machambeiros (farmers) and import/exporters of the patel caste, such as Dhayabhai Jivanjee Patel, Govindji Kanji Gokal, and Mohanlal Popatlal. In turn, Anilkumar Govindjee, who was Hindu and a Portuguese citizen, as well as the Ismailis and Sunni Muslims of Indian origin, such as Kanji Gina, Suleman, and Abdul Mahomed Omar, who were Pakistani citizens, took advantage of the situation, buying the assets of their competitors for a modest price.

Table 7. Liquidations (ordered according to their value)

Source:Boletim Oficial de Moçambique, series 2.

Table 8. Buyers of the Liquidated Assets

Source:Boletim Oficial de Moçambique, series 2.

While the poorer strata of the Indian community were the first to be deprived of their possessions and expelled to India, affluent families bought many items before leaving the colony, especially cloves, silk, cotton textiles, and other luxury goods. Interviewees from both groups underline how their transnational networks and accumulated social capital in Mozambique offered them empowering resources. Indeed, some repatriated families started new migratory processes towards the UK and the Americas. Haribhai stressed how the structures of transnational Hinduism already operating across borders, such as the Swaminarayan community, enabled some patel and lohana families expelled from Mozambique to maintain generally successful migratory trajectories.Footnote 110

There were some suri patel Indians who had machambas in Manhiça and Marracuene. The great machambeiros, like us, produced rice, cashews, copra, sisal, citrus, and bananas. After the Goa crisis, we were all repatriated to India. We had lost property and business worth millions of rupees. In Gujarat, my family turned to Pramukh Swami. We had the Swaminarayan community… My family went to London before settling in Boston. But we still have cousins in Mombasa and Maputo.Footnote 111

Despite the colonial protection they received, large Indian firms increased their transnational economic paths in the 1960s, with investments in Goa and Gujarat, neighbouring African territories, and Europe, namely in the UK and Portugal, where they set up offices to facilitate imports and exports. The ambivalence of Portuguese colonial authorities towards Indians made the importance of transnational connections even clearer. Again, the mobilisation of affinity relations—established by aunts, spouses, sisters, and daughters—as well as caste connections or membership in the same religious communities, generated dynamic connections between “here” and “there.” The exchange of people, capital, and goods with India did not cease, though. Rather, it was pursued clandestinely, namely through safe conducts provided by the Indian embassy in Malawi.

We were travelling to Malawi. As our Portuguese passports were not valid to enter India, the embassy of India in Malawi issued us a safe conduct through which we travelled to India, and then we returned to Malawi. Officially, nobody went to India.Footnote 112

As previously mentioned, the Portuguese government allowed a number of Indian citizens to reunite their families in Mozambique from 1971 onwards. Until that year, Indian citizens who had remained in Mozambique but only had residence permits faced severe travel constraints, and numerous petitions made by Indian nationals and their relatives to return to the country were customarily rejected. According to PIDE/DGS, countless delicate situations were yet unresolved: “old men and women who by fatality were [expelled and] split from their sons who stayed in Mozambique, were living in the utmost misery and abandonment; children who did not know anything about war and politics; individuals who were Indian, but until their expulsion had never been to India.” Moreover, the sons of Indian nationals were engaged in colonial warfare, but their relatives were not allowed to return to the colony, which generated dissatisfaction amongst the “Indo-Pakistanis.” Therefore, considering that almost ten years had passed since the invasion and occupation of the EPI, and that the Portuguese overseas territories were already facing “enough problems,” PIDE/DGS suggested an easing of this policy: following a thorough investigation process, residence permits should be granted enabling familial reunification processes.Footnote 113

Concluding Remarks

While comparable in its fundamental dynamics to its European counterparts, Portuguese colonialism has been characterised as a relatively “weak” power, built on the mobility of different segments of the Portuguese population between colonies, defined by Pamila Gupta as its “uniquely itinerant quality.”Footnote 114 Moreover, even though the Portuguese government did not implement policies to attract migrants, it heavily depended on diasporic/emigrated groups, such as the several Indian communities established in Mozambique, to develop and maintain its empire.Footnote 115 From the nineteenth century until the late 1960s, mirroring and compensating this weakness, the imagining of Portuguese colonialism swayed between ambivalent representations of modernity and backwardness, idealised imperial designs and shameful self-images, powerful imaginaries on the Portuguese colonial exceptionalism cultivating a harmonious mixed-race society straining against its deeply repressive and racialised governance. This wavering between the perpetuation of a multiracial empire allegedly based on Portugal's cultural difference and its international self-debased political image eventually reflected on the duplicitous governance policies targeting Indian nationals settled in Mozambique in the aftermath of the Goa crisis.

As emphasised in this article, ambivalence characterised the way Portuguese colonial authorities publicly constructed the internment of Indian nationals as a humanitarian and protective measure, aiming to prevent reprisals towards their lives and assets. At the same time, the dispossession and repatriation of Indian nationals were displayed as harsh retaliatory political measures, which inflicted profound experiences of personal and family trauma, as well as material loss. Accordingly, the ambivalence inherent to all these processes was basically a denial operation that claimed, both internally and abroad, the exceptionalism of the Portuguese multiracial empire. Yet the revocation of Mozambique-born Indians’ Portuguese citizenship brought to light a policy that was at odds with the purported political and legal principles of Portuguese colonial governance, based as they were on Luso-tropicalism.

In addition, political measures against Indian citizens were far from being univocal and uncompromising. On the contrary, they were marred by innumerable exceptions, and therefore often perceived as a signal of political ambivalence. The Goa crisis indeed forced colonial authorities to officially admit their economic vulnerability and dependence on Indian subaltern elites. Against the wishes of certain sectors of Mozambican colonial society, large import/export Indian firms were not closed, despite the fact that some of their owners held Indian nationality. The expulsion orders of the Indian citizens who managed these companies were at first suspended and then annulled, since their departure would harm the economy of the colony. Furthermore, the fight between the Portuguese Armed Forces and Mozambican liberation movements, in which the sons of Indian nationals participated on the colonial power's side, forced the Portuguese government to reverse its policy, enabling multiple processes of family reunification.

By exploring the positioning of Indian individuals and their communities towards the Goa crisis, this article contributes to a more nuanced assessment of the vast spectrum of perceptions and responses vis à vis this historical event. Even though most Indians were concerned with practical consequences rather than political questions, the Goa crisis triggered a highly ambiguous and unsettling atmosphere within and amongst Indian communities, as much as it tainted their relationship with the Portuguese colonial state. A small number of Hindu male respondents evoked, in uncharacteristic memories, their fathers’ anti-colonial ideals towards Portuguese rule and described the complex and ambivalent mix of identification and opposition that often characterises the relationship between coloniser and colonised. While they do not account for historical events, Hindu female respondents share a specific way of recounting the Goa crisis, providing us with a narrative that emphasises its consequences on the familiar sphere. Moreover, the way they reworked and passed down these narratives across generations, particularly to their daughters, suggests their ability to voice their concerns, rendering them explicit through religious idioms with which their subaltern voices speak.

Shared memories of the Goa crisis still echo in the lives of Mozambican Indians. Hundreds of them, coming from the UK, the US, Mozambique, Kenya, and Tanzania, gathered in Lisbon in June 2018 for a celebration of fifty years of Indian film soundtracks performance in Lourenço Marques. During the event, the Goa crisis was referred to as a time that forced people of Indian origin to make identity statements and to engage in instrumental uses of legal citizenship in the face of Portuguese colonial authorities. Significantly, Portuguese colonial rule was also recalled as being marked by a structural ambivalence towards Indian Otherness. As shown, ambivalence still characterises the Goa crisis and its aftermath in Mozambique and beyond.