Introduction

The debate about the presidentialization of modern democracies has attracted considerable attention over the past decade. Until very recently, there were several ‘usual suspects’ that immediately came to mind whenever the debate focussed on a shift of power to the benefit of individual leaders and a concomitant weakening of collective actors like political parties or parliaments: Tony Blair, Gerhard Schröder, Göran Persson, and Silvio Berlusconi (see, e.g. Foley, Reference Foley1993; Calise, Reference Childs and Webb1994; Aylott, Reference Aylott2005). These are now names that belong to past political eras, and inevitably, this raises the question as to whether political analysts and political scientists were blinded by the light of striking individual performances that may have prevented them from clearly recognizing the lack of structural change. On the other hand, there are similar examples of strong leaders that date somewhat further back. Clearly, Margaret Thatcher is the most obvious example here, but other names also warrant mentioning, including Bettino Craxi and Helmut Schmidt (Fabbrini, Reference Fabbrini1994; Padgett, Reference Padgett1994a). Does this support the contention of those who argue that we are seeing a seminal shift in the working mode of modern democracies? Or are these examples evidence for the simple fact that political styles co-vary with the personalities of the incumbents? In The Presidentialization of Politics (Poguntke and Webb, Reference Poguntke and Webb2005), we argued that a wide array of evidence from a diverse range of democracies pointed to a long-term cross-national structural shift towards a more presidentialized model of politics. Indicators included the expansion of resources available to leaders, an increasing focus of electoral processes on leaders and the growing mutual autonomy of leaders and their parties. In this article, we seek to re-consider this argument in the light of recent developments in two countries that were central to our thesis, Germany and the United Kingdom. Within the limits of a democratic setting, this constitutes a most different systems design: consensus vs. majoritarian democracy, federal vs. unitary state, proportional electoral system vs. first-past-the-post, multi-party system vs. two-party system, codified vs. flexible constitution, and so on. As governing formulae have changed in both countries over time, the most different systems logic applies also over time. In fact, there are prima facie grounds for suspecting that recent political history might have eroded the presidentialization process in each country. Germany has moved from a highly asymmetric red–green coalition that provided a clear opportunity for Chancellor domination of the executive to a period of Grand Coalitions with almost equally strong coalition partners, in which such domination would seem less likely. As the Grand Coalition government was interrupted by another asymmetric Christian–Liberal coalition, we have a perfect longitudinal variation of coalition patterns. Similarly, the long history of single-party governments in the United Kingdom gave way to a rare experiment (for Westminster) in coalitional power sharing between two parties, circumstances that one would surely expect to limit prime ministerial power. More recently, there has been a reversion to single-party government. These developments notwithstanding, however, it is our contention that the presidentialization thesis retains its purchase in these two countries, which represent a hard test of our thesis. In the next section, we briefly remind readers of the main features of the thesis, before turning to a more detailed analysis of the implications for it of recent developments in Germany and the United Kingdom.

The concept of presidentialization

The concept of presidentialization was inspired by the observation that strong leaders play an increasingly prominent role in the politics of modern democracies. However, this impressionistic point of departure should not be mistaken for the analytic concept. Certainly, individual personalities and hence leadership styles cannot be ignored in any analysis of the nature and mechanisms of political leadership. Yet, the core of the concept of presidentialization focusses on the structural conditions that determine the constraints and opportunity structures under which leaders operate (Poguntke and Webb, Reference Poguntke and Webb2005). In short, we argue that the decline of stable political alignments has increased the proportion of citizens whose voting decisions are not constrained by long-standing party loyalties. At the same time, the changing structure of mass communication has increased the capacity of political leaders to bypass their party machines and appeal directly to voters, who are less loyal to a given party creed than in previous phases of democratic politics. The tendency for political leaders to become more pre-eminent within executives and more independent of their followers in parliament and party has been further amplified by the vastly expanded steering capacities of state machineries and the internationalization of decision-making (the ongoing process of European integration being a particularly pronounced example of this internationalization of politics). As a result, we expect three interrelated processes to occur in modern democracies that lead to a political process increasingly moulded by the inherent logic of presidentialism:

-

(a) increasing leadership power and autonomy within the political executive;

-

(b) increasing leadership power and autonomy within political parties; and

-

(c) increasingly leadership-centred electoral processes.

In a nutshell, the presidentialization of politics increasingly allows political leaders to act ‘past their parties’. Although it is inevitable that observers will draw parallels with the American presidency, it is vital to understand that the concept reaches beyond a mere analogy with the functioning of the political system of the United States; rather, it is based on an analysis of the inherent logic of presidential systems in general and abstract terms. This being so, it is even possible for the politics of the United States to ‘presidentialize’ by more fully realizing the presidential logic that is built into its political system (Fabbrini, Reference Fabbrini2007).

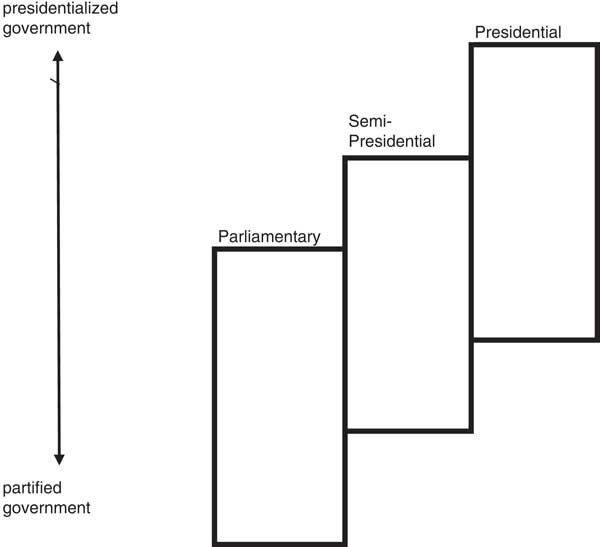

Essentially, the nature of the political process can shift (to varying degrees) from a more partified to a more presidentialized mode of government, as illustrated in Figure 1. How far an individual system can move towards the presidentialized end of the continuum is determined by a wide range of structural and contingent factors. The latter include the personal characteristics and skills of political leaders, and political contexts which determine their room for manoeuvre. Furthermore, it is constrained by the formal configuration of political institutions. This is shown in Figure 1 by the different endpoints for the three principal regime types. Clearly, there are formal institutional impediments that prevent parliamentary or semi-presidential regimes from moving all the way towards a presidentialized mode of government, whereas presidential systems can, of course, fully realize their potential. This is an important point because it means that we are not making the obvious Straw Man thesis that ‘presidentialization’ simply means there is no difference between parliamentary and presidential regimes now because party leaders in both settings are in identical positions. To the contrary, we accept that there will always be some significant differences.Footnote 1 We certainly acknowledge that the operating logic of a presidential system is essentially different to that of a parliamentary system; this is because a system based on the separation of powers and a popularly elected head of the executive carries with it particular institutional constraints and incentives, which leave the leader more autonomous of his legislative followers and executive colleagues than a prime minister. However, notwithstanding these very real constitutional differences between presidentialism and parliamentarism, we are struck by the way in which the operating logic of the former now seems to be coming increasingly to apply to all types of regime. Although a classic parliamentary party leader would gradually have to work his or her way up through the party, winning the support of a dominant faction, the ‘presidentialized’ leader emerges at the helm of a party in a modern parliamentary system (sometimes meteorically) principally by virtue of his or her capacity to attract the direct support of the electorate at large. This generates a sense of a personal mandate that enables leaders to feel that they can bypass the wishes of the party (if necessary) in setting the direction of the party and the government (when in power). However, this sense of autonomy cuts both ways: whereas the leader is more independent of party, the party in the legislature might also feel more independent of the leader, and therefore be more prepared to rebel. Moreover, although the ‘presidentialized’ leader can be very powerful at times of electoral and political advantage, s/he can also be more vulnerable at times of disadvantage, precisely because s/he lacks a real power base within the party; in traditional parliamentary parties, such power bases can offer some shelter from political storms.

Figure 1 Regime type (Poguntke and Webb, Reference Poguntke and Webb2005: 6).

The interaction of structural and contingent factors means that political systems can also move back towards the partified end of the continuum. Parties do not always generate strong leaders, and if a weak leader assumes office under unfavourable political circumstances parties and parliaments will certainly be able to claw back some of the power they have previously lost even though structural factors may pull in the opposite direction. In fact, the range of cases from Western Europe, Canada, and Israel that we examined in The Presidentialization of Politics revealed a broad long-term tendency towards the structural enhancing of the presidential logic in modern democracies. However, what are the implications of more recent developments in Germany and the United Kingdom?

Germany: presidentialized coalition government

By choosing Germany as one of our case studies, we can control for a variety of coalition formulae. More precisely, we cover almost two decades and all politically feasible coalitions in contemporary Germany on the national level, namely the SPD-Green Schröder government as well as the Christian–Liberal and two Grand Coalitions led by Chancellor Angela Merkel. As this includes both core parties as leading parties of government, we can therefore examine possible signs of presidentialization in government and opposition for both of them.Footnote 2 Clearly, this includes different strategic positions at the beginning of election campaigns, yet, as the following section on the electoral face will show, processes of leadership selection and campaigns have increasingly turned into presidentialized leadership contests.

The electoral face

Although the jury is still out when it comes to unequivocal empirical evidence on the personalization of election campaigns and the suggestion that the leadership effect on individual voting decisions has grown irrespective of the inevitable contingencies of political seasons (for recent overviews, see Karvonen, Reference Karvonen2010; Aarts et al., Reference Aarts, Blais and Schmitt2011; Kriesi, Reference Knoll2012), there is a growing literature that maintains that leaders have become more important for voting decisions (Bittner Reference Bittner2011; Costa-Lobo and Curtice, Reference Costa-Lobo and Curtice2014; Garzia, Reference Garzia2014; Mughan, Reference Müller-Rommel2015). A growing number of late deciders and unattached voters in Germany are but two factors that indicate that Germany is no exception (Schmitt-Beck et al., Reference Schmitt-Beck, Rattinger, Roßteutscher, Weßels and Wolf2014: 359). It seems therefore rational for campaign strategists to increasingly emphasize their leading personnel. To be sure, this depends on the electoral attractiveness of the candidate in question and Merkel’s popularity was certainly an asset for the Christian Democrats campaign of 2009 and 2013. The trend towards personalized election campaigns was epitomized in 2013 by a giant poster featuring nothing else but Merkel’s hands in their characteristic position. Furthermore, the strong focus of German parties on the electoral attractiveness of their Chancellor candidates is reflected by the corresponding media coverage, which has centred increasingly on the contest between the main candidates. TV debates between the main contenders are now a regular feature of German election campaigns (Maier and Faas, Reference Maier and Faas2011).

The party face: party leadership in changing coalitional contexts

Irrespective of about academic debates over the electoral effect of leaders, it has become evident that parties increasingly behave as if they have a significant effect. This means that parties select electoral leaders mainly on the basis of their perceived electoral appeal, whereas their anchorage in the party’s dominant coalition is of secondary importance. Gerhard Schröder set the stage when he single-handedly defined a Land election as a quasi-plebiscitary leadership contest and forced party chair Oskar Lafontaine to accept that he would be the more promising Chancellor candidate (Poguntke, Reference Poguntke2005b: 74). The selection of the SPD Chancellor candidate for the 2013 Bundestag elections exemplifies this further: Former Finance Minister Peer Steinbrück had held no significant party or parliamentary party office since the end of the Grand Coalition in 2008 and was clearly to the right of the party’s mainstream. Yet, he became a serious contender mainly because polls rated him neck and neck with Chancellor Merkel in summer 2011. Eventually, he ‘emerged’ as Chancellor candidate after two remaining potential candidates, the party chair and the chair of the parliamentary party, indicated that they did not intend to run. The vote at the special party congress was then a mere formality. It is worth recalling in this context that Angela Merkel rose to power as an outsider within the Christian Democratic Party as she lacked (and still lacks) an entrenched intra-party power base. She has no affiliation with any of the powerful internal collateral organizations and her own Land party controls only few votes at the national party congress. To be sure, her initial candidacy was the result of the early election of 2005, which made Angela Merkel in her capacity as party chair and leader of the parliamentary party the only plausible choice, but ever since she has remained unchallenged within the party despite her tenuous power base, and this is mainly owing to her ability to win (national) elections.

What does this mean for the power of German party leaders? Or, to put it more precisely, have major policy changes originated from the parties in government and, more importantly, from the Chancellor? The sheer magnitude of presidentialized party leadership can be illustrated by looking at the most important policy junctures since the beginning of the new millennium.

Let us begin with ‘Agenda 2010’, which represented a major policy shift imposed on the governing Social Democratic Party by Chancellor Schröder. There can be little doubt that the neo-liberal turn of the governmental policy agenda (and hence the SPD) was imposed largely unilaterally by Chancellor Schröder and his inner leadership circle. In fact, Agenda 2010 was heavily contested within the SPD and Schröder was confronted with a hostile membership referendum initiative, which could only be stalled by convening an extraordinary party congress (Poguntke, Reference Poguntke2005a). In the end, this policy shift led to the exodus of a substantial part of the trade union wing and culminated in the setting up of a new Left Party, which emerged from a merger of the mainly East German post-communist PDS and the mainly West German anti-Agenda movement, WASG (Hough et al., 2007). Similarly, the much more assertive role of Germany in foreign security, above all the Afghanistan mission, was imposed on the SPD (and equally on the Greens) from above, that is, from the government. The fact that Schröder, in the end, tied the 2001 Bundestag vote on the Afghanistan mission to a vote of confidence highlights how much pressure was needed to secure support from his own party (Poguntke, Reference Poguntke2002).

Just like Gerhard Schröder, Angela Merkel has successfully governed largely ‘past her party’ and pushed for a substantial number of policy changes (Clemens, Reference Coates and Elliott2011). Unlike her predecessor, however, she prefers leadership by stealth, which means that she rarely leads discussions but usually decides them once she has weighed the substantive and strategic arguments. This gives her additional room for manoeuvre, as she can always choose to distance herself from those who have stuck their necks out. Examples include a revision of family policies that are clearly at odds with some of the tenets of the Christian core of the party (Lorenz and Riese, Reference Lorenz and Riese2015: 510) or the decision to opt for a modified version of a minimum wage on the eve of the 2013 election campaign (Zolleis, Reference Zolleis2015: 83–84).

Whenever her low-key leadership style has been inappropriate, Chancellor Merkel has been able to assume an assertive role. Although the explicit support for the controversial Stuttgart railway station project Stuttgart 21 in September 2010 may have been supported by a considerable majority within the CDU, it was, nevertheless, an example of a typical ‘ex cathedra’ decision by the Chancellor. More importantly, this coincided with a major U-turn in nuclear energy policy that was explicitly framed as the return to a more conservative strategy. The decision to substantially extend the period of time until nuclear power generation should be phased out was met with considerable scepticism within the Chancellor’s own Christian Democratic Party. More significantly, the second U-turn almost immediately after the Fukushima meltdown exemplifies the extent to which major policy changes have become the prerogative of the Chancellor (Poguntke, Reference Poguntke2012). Clearly, two U-turns within barely 6 months are not the result of a political party revising its programme. It is simply the result of the party following executive leadership – willingly or grudgingly.

Finally, and in many ways most significantly, the ongoing sovereign debt crisis has elevated Chancellor Merkel to a position where she is increasingly (in conjunction with her closest aides and the Finance Minister) the pre-eminent decision-maker, whereas her party is reduced to ratifying decisions made elsewhere. It should be said that there are many other, politically less important examples – like tax policies, the debate over women’s quotas in board rooms, the controversy over early childcare – where the pattern is essentially the same: to the extent that there is an intra-party debate, the Chancellor, in the end, decides where the buck stops. This may be, in some cases, a slight exaggeration, not least because there is a coalition partner. However, the Christian–Liberal coalition was characterized by a truly remarkable unwillingness on the part of the Chancellor (and her party) to accommodate the Liberals. Furthermore, we have also seen a significant ruthlessness of the Chancellor vis-à-vis her own party. The decision to sack the leader of the largest Land party from a senior cabinet post after his defeat in the May 2012 North Rhine-Westphalian Land election without prior consultation with the power brokers within this Land party certainly marked a significant departure from decades of practice.

Similarly, her Vice-Chancellors from the SPD have repeatedly enforced policy U-turns against the dominant creed of their own party. Vice-Chancellor Franz Müntefering’s decision to raise the pension age at the beginning of the 2005–09 Grand Coalition government was certainly one of the most conspicuous cases. Similarly, Vice-Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel repeatedly imposed policy change upon his party during the Grand Coalition, which assumed office in 2013, including a controversial loosening of data protection and a supportive attitude of the SPD vis-á-vis the EU-US TTIP free trade negotiations. Above all, he forced his reluctant party into the Grand Coalition by conducting a postal ballot of the party membership on the coalition treaty, hence bypassing the party activists – a clear example of seeking a personal mandate within his party.

The executive face

Let us begin the review of the evidence by drawing attention to the institutional context under which German Chancellors operate. Even after the 2006 reform of federalism, which resulted in a somewhat clearer separation of competencies between the federation and the Länder, the core characteristic of the German political system has remained largely unaltered. Germany has been called a negotiation democracy, which gives the Chancellor (and his or her closest collaborators) a pivotal role as chief negotiator in the negotiations between the Federal and Land governments over legislation (Mayntz, Reference Mayntz1980; Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1985; Holtmann and Voelzkow, Reference Holtmann and Voelzkow2000). To a considerable degree, this protects the Chancellor from pressures of his own party (or coalition partner) because he or she can rightly claim that the preferences of crucial Land governments need to be taken into account. Moreover, the growing importance of European-level decision-making has introduced a structural ‘executive bias’ into the policy-making process of all EU member states. Comparative research has shown that the most important effect of Europeanization on national political parties has been the strengthening of party elites. This effect is particularly pronounced for party elites who simultaneously occupy core positions in national governments (Ladrech, Reference Ladrech2007; Poguntke, Reference Poguntke2007; Carter and Poguntke, Reference Clarke, Sanders, Stewart and Whiteley2010).

Clearly, not all relevant indicators can be covered in the limited context of this article. We will therefore concentrate on developments that strengthen the ability of the Chancellor to govern past his or her party and coalition partners. They include (a) the material resources available through the Chancellor’s office, (b) a partial change in the recruitment patterns to ministerial office, (c) the outsourcing of policy formulation, and (d) the impact of the financial crisis.

Resources at the disposal of the chief executive: the Chancellor’s office (Bundeskanzleramt) represents an important structural prerequisite for growing pre-eminence of the German Chancellor. Over the years, it has developed from a fairly rudimentary support unit into a formidable centre of executive power with sufficient manpower to screen and coordinate governmental policy (Smith, Reference Smith1991: 50; Müller-Rommel, Reference Mughan1994: 111; Müller-Rommel, Reference Müller-Rommel1997: 179, Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld2003: 365). The office had some 120 staff during Adenauer’s incumbency (1949–63), after which it began to grow at an average annual rate of 4.3% for the subsequent four decades, reaching about 500 staff by the late 1990s, which makes it one of the largest of its kind in Western Europe (Müller-Rommel, Reference Müller-Rommel2000; Knoll, Reference Kriesi2004: 412). Even though the early Brandt government’s enthusiasm for central planning did not lead to conspicuous success (Padgett, Reference Padgett1994b: 9), the Chancellor’s office acquired a pivotal role in executive decision-making, although this obviously varied with the individual leadership styles of incumbents (Niclauß, Reference Nelson1988; Padgett, Reference Padgett1994a; Helms, Reference Helms2002).

Changing patterns of ministerial recruitment: we have previously argued that one feature of the presidentialization of the executive is a growing tendency of chief executives to appoint non-party experts (Poguntke and Webb, Reference Poguntke and Webb2005: 19) or to rapidly promote politicians who lack a distinctive party power base, most notably a seat in the Bundestag parliamentary party and a strong anchorage in a regional party organization as a result of a sustained intra-party career. From our perspective, this concentrates more power in the hands of the Chancellor because such politicians lack an independent power base in the party. As such, appointing core members of the cabinet who have such a career trajectory may be instrumental in enhancing the control of the Chancellor over their portfolio. At the same time, such a recruitment strategy would substantially reduce the power of the party activists who might otherwise be capable of interfering with the strategic objectives of the Chancellor via ‘their’ minister.

Over the past two decades, German Chancellors have repeatedly appointed politicians as ministers who lacked a party-related career (even though they may have been party members). Both Helmut Kohl and Gerhard Schröder appointed a considerable number of cabinet ministers from outside the Bundestag parliamentary party. Even though it is somewhat premature to identify a sustained trend on the basis of a limited number of cases (Helms, Reference Helms2002: 155–156), this is an indication of the tendency of Chancellors to govern past the dominant coalition within their own parties. If anything, this trend has continued in recent years. Angela Merkel heavily (and unsuccessfully !) based her 2005 Bundestag election campaign on the nomination of an outsider for the office of Minister of Finance. Although the nomination of former constitutional judge and law professor Paul Kirchhof backfired by providing the Social Democrats with a welcome opportunity for criticizing the alleged neo-liberal agenda of the Christian Democrats, this did not discourage Angela Merkel from appointing outsiders to her cabinet (Niedermayer, Reference Niclauß2009). One of the most prominent cabinet members of the Grand Coalition was the Minister for Family Ursula von der Leyen who lacked an independent party career and has been instrumental in re-orienting Christian Democratic family policy.

Similarly, the 2009 SPD Chancellor candidate Frank-Walter Steinmeier nominated a self-made millionaire to his election team (‘Kompetenzteam’) who is clearly not a typical Social Democrat. Even though Harald Christ had a working-class background and an SPD membership card, his career in the finance sector was hardly what traditional Social Democrats would regard as a core qualification for a higher office in Social Democratic politics. Likewise, Chancellor candidate Peer Steinbrück included two female academics without significant intra-party careers in his election team.

The outsourcing of policy formulation: another strategy for governing past political parties is the ‘outsourcing’ of policy formulation to hand-picked commissions or to professional consultancy firms. It is a mechanism that corresponds to the appointment of outsiders to ministerial offices. By appointing special commissions for highly visible policy advice, the usual discussion process within political parties is largely bypassed. Through appropriate communication strategies, such commissions can be furnished with the allegedly higher legitimacy of a ‘neutral’ and pragmatic expertise ‘above party political quarrels’, thereby rendering it very difficult for the usual party political power centres to obstruct a government plan. It is true that the technical drafting of legislation has always been largely the prerogative of ministerial bureaucracies; however, the top echelons of ministries have always been under fairly strong party political influence. In any case, such commissions are not only used primarily for the drafting of detailed legislation but for initiating substantial policy change.

The frequent use of such commissions by Chancellor Schröder inspired a German scholar writing on the topic to use the ironic book title Die Berliner Räterepublik (The Berlin Soviet Republic) (Heinze, Reference Heinze2000). Even though Gerhard Schröder may have used this technique extensively in his struggle to overcome blockages to reform within his own party, the strong and publicly highly visible role of external advisors and advisory boards was not invented by him. In fact, it has become an increasingly strong element of the German policy process since the 1960s, when the ‘Council of Economic Advisors’ was first established (Patzelt, Reference Patzelt2004: 279–285; Siefken, Reference Siefken2006). The strategy of bypassing party politics was taken to its logical conclusion by the newly appointed CSU Minister for Economics Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg in 2009 who outsourced the complete drafting of a bill to a law firm.

The Europeanization of executive leadership: arguably, the financial crisis has not changed the quality of executive dominance over national parties (Carter et al., 2007). However, the sheer magnitude and imminence of the problems at stake have highlighted the structural imbalance in favour of the executive. The ongoing and accelerating sovereign debt crisis has repeatedly put Chancellor Merkel in a position where she has confronted her own party (and her coalition parties) with decisions that have been agreed by European summits. In some cases, Parliament has had little more than a few days to ratify rescue packages, which have been agreed between European heads of government. In this way, the European Stability Mechanism, which was agreed in early 2012 and finally launched in October 2012, committed a sum of almost two-thirds of the annual federal budget. Although there was growing unease among Christian Democratic ranks (and some dissenting votes), this was, nevertheless, passed without much parliamentary, let alone intra-party, debate. Significantly, the Chancellor twice needed votes from opposition parties to get parliamentary approval for Euro rescue packages during the Christian–Liberal coalition (Murswieck, Reference Murswieck2015: 178).

At the same time, the financial crisis has highlighted another feature of the inherent logic of European supranational decision-making: whereas Chancellor Merkel has succeeded in pushing through measures that were agreed between European executive leaders, it has become increasingly questionable as to whether these measures are always in line with her own preferences. After all, Chancellor Merkel has repeatedly re-adjusted (to put it mildly!) her position in the course of the crisis. Thus, the ability of the Chancellor to impose policies (or even policy change) upon his or her party and the executive may be greatly enhanced as a result of European integration, but these policies are not necessarily the independent choice of the Chancellor. He or she is as much a prisoner as an executor of supranational forces vis-à-vis national politics.

In sum, the review of the evidence on Germany clearly shows that patterns of presidentialization have persisted across a number of different coalitions. Party democracy is increasingly dominated by leaders, and this is particularly pronounced for parties in government.

The United Kingdom: from majoritarian to consensus-style presidentialization?

It is widely recognized that the roots of prime ministerial power in the United Kingdom lie in the ability of the Prime Minister to draw upon a series of institutional and personal resources that complement and advance his or her formal and informal powers (Bennister and Heffernan, Reference Bennister and Heffernan2012). The institutional resources available to the Prime Minister include: The ‘royal prerogative’ powers where formally the PM is in the position of being an adviser to the monarch, but in reality exercises for himself or herself the right to lead the government (e.g. in appointing and dismissing ministers, managing government business, and conferring honours); the ability to use his or her political prominence and PR advisors to set political agendas and influence interpretation of political information via management of the news media; the power to manage the Cabinet and its committee system (which in practice often means the ability to bypass Cabinet in taking key decisions); and the power to organize and control what is de facto a prime ministerial department, using the Prime Ministerial Office and the Cabinet Office to set policy agendas (Burch and Holliday, Reference Calise1999).

There is little doubt that two premiers worked particularly hard in recent British history to augment the institutional resources at their disposal: Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair. The latter, for instance, built his governing capacity by (a) increasing the size of the Prime Ministerial Office by 30% (to 150), and (b) creating a personal staff that was led by a presidential-style Chief of Staff and included a record number of special advisers (25, compared with the eight, which his predecessor John Major had). Although David Cameron initially vowed to reduce the number of Special Advisers working in government, the reality was that by 2014, he had 46 working for him at 10 Downing Street. In absolute terms, the number of advisers working for the Prime Minister has at the very least remained stable since Tony Blair’s day, and now accounts for 45% of all central government special advisers (Maer and Faulkner, Reference Maer and Faulkner2015). The development of the PMO and the Cabinet Office since 1970, and the growing connectedness between them, effectively means that there now exists ‘an increasingly integrated core which operates as the central point in the key policy networks of the British state’ (Burch and Holliday, Reference Calise1999: 43), and which serves to coordinate the various fragments of the executive.

In addition to the Prime Minister’s institutional resource factors, which we may regard as underlying structural bases of power, there are a number of more contingent personal resource factors available to British Prime Ministers that enhance their authority. These personal resources are the key to the ‘political capital’ that PMs accrue and which enable them to exercise authority over the party and within the executive. Such personal resources include: personal reputation and ability; association with actual and anticipated political success; public popularity; high standing in his or her party, parliamentary party and government; and parliamentary arithmetic (Heffernan, Reference Heffernan2003). Thus, it is obvious that, as Prime Minister with Commons majorities of well over 100, Tony Blair was going to be more powerful than John Major, a Prime Minister with a precarious (and sometimes non-existent) majority between 1992 and 1997. On the other hand, as he gradually lost public popularity (especially after the Iraq war in 2003) and the Labour Party’s electoral prospects came to look less certain, his standing among his own backbench MPs and Cabinet colleagues became less secure. His authority was, therefore unmistakably diminished by the mid-2000s, even though his formal powers and institutional resources were unchanged.

The personal resources at a Prime Minister’s disposal are essentially informal, contingent, and fluctuating, whereas the institutional resources are stable and enduring. However, it is the interaction of the two sets of factors together that determines a Prime Minister’s authority to govern at any given moment; in a famous simile, George Jones once argued that prime ministerial power was like an elastic band that could be stretched under circumstances propitious to the exercise of personal authority, but that when those circumstances were less positive the elastic band snapped back into place (Jones, Reference Jones1990); in other words, the real constraints of parliamentarism came into play as party and Cabinet restrict and maybe even replace an incumbent PM (as Thatcher and Blair eventually found out).

In The Presidentialization of Politics, Heffernan and Webb (Reference Heffernan and Webb2005) argued that, within the limits imposed by the institutional context of majoritarian parliamentarism, there had in some respects been a long-term structural shift in the direction of presidentialization in the United Kingdom. First, it was noted that election campaigns had become more candidate centred, with parties offering leaders greater prominence in their election campaigns and the media devoting greater attention to them; relatedly, leader effects on voting behaviour appear to have become more significant. Second, leaders in the United Kingdom and their parties have become more autonomous of each other. Third, the potential for prime ministerial power within the state’s political executive has been enhanced owing to the structural changes which have generated a larger and more integrated ‘executive office’ under his or her control since 1970.

None of this is to deny that these developments have occurred in the context of a traditionally highly partified form of parliamentarism. The impact of this institutional and historical structure continues to be felt. In particular, parliamentary parties and Cabinets can, under certain circumstances, strike back at individual leaders, and occasionally even knock them clean off their elevated political perch. It is certainly not the case that Prime Ministers have become completely indistinguishable from Presidents, but the changes that have occurred across a number of political dimensions are mutually consistent. These changes endow leaders with enhanced intra-party power resources and autonomy, provide Prime Ministers with greater structural resources within the political executive, and facilitate a more pronounced personalization of governmental and electoral processes. Taken together these changes mean that politics in Britain’s parliamentary democracy has come to operate according to a logic which in some respects more closely echoes presidential politics than was hitherto the case. However, what impact have political developments in recent years had on this conclusion?

Presidentialization in the context of multi-party politics

The extraordinary political success that Tony Blair enjoyed for approximately a decade from the time of his ascent to the Labour leadership in 1994 unquestionably cemented the notion that contemporary parties require modern, charismatic presidential-style leaders in order to be electorally successful. As for Blair, the rapid – in some cases meteoric – rise to the top of their parties by British politicians such as David Cameron (Conservative) in 2005 and Nick Clegg (Liberal Democrat) in 2007 is impossible to ignore. This type of leader is comparatively young (i.e. in their early 40s), has excellent skills as a public communicator, and has a public appeal (at least for a while) that enables him (or maybe her, though no woman in such a mould has yet ascended to the helm of a major British party) to bypass more venerable and experienced colleagues. Not every leader in recent British political history has fit this mould, but those found wanting in these terms – men such as Iain Duncan Smith (Conservative), Ming Campbell (Liberal Democrat), and Gordon Brown (Labour) – have not enjoyed long incumbencies as leader. In particular, the central role the news media plays in modern politics makes it essential that leaders can handle the media well; communication and media skills are now plainly indispensable for modern party leaders. There is no doubt that Cameron’s unexpected surge to victory in the party leadership contest of 2005 owed everything to his ability to convey these skills in an impressive performance before a televised party conference.

The electoral face

In view of this, it was no surprise that the Conservatives ran presidential-style election campaigns around Cameron in 2010 and 2015. In both years, he benefited from confronting Labour rivals who lacked public popularity (Gordon Brown and Ed Miliband, respectively), and the Tories therefore sought to contrast this with the appeal and qualities of their own leader. This was given special emphasis in the general election by the advent of televised debates held between the leaders of the main parties; in 2010 (the first time that such TV debates happened in the United Kingdom) the main party leaders (Brown, Cameron, and Clegg) faced each other in three debates that attracted large TV and radio audiences; in 2015, a variety of formats were deployed, which sought to take account, for the first time, of minor party leaders as well. At the first debate, the leaders of the big three parties were joined by those of the Scottish and Welsh Nationalists (SNP and PC), the UK Independence Party and the Greens. In addition, there were further TV debates involving only Opposition party leaders, and special leaders’ debates in the devolved areas of the United Kingdom (Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland) – all of which served to lend an unprecedented degree of exposure to and emphasis upon party leaders. Each debate was followed by extensive media interpretation and opinion polling seeking to understand who had ‘won’; those deemed to have done so (Clegg, twice and Cameron, once in 2010, whereas the SNP’s Nicola Sturgeon was widely regarded as having shone in 2015) were clearly advantaged over those who ‘lost’, something which enabled the successful performer to claim they had benefited their party’s electoral performance. Indeed, analysis of survey data revealed that Cameron was actually the only one of the major party leaders who was more popular than his party in 2010 (especially among female voters): in this sense, he was likely to have been the only leader who actually enhanced his party’s result in the election (Childs and Webb, Reference Clemens2012: 199, table 8.10).

At the time of writing, it is too soon to say with certainty how significant leader effects on voting behaviour were in 2015, but it seems extremely likely that they will prove highly significant. In general terms, there is a growing school of empirical analysis which is using increasingly sophisticated methods to uncover the full extent of leader effects (Bittner, Reference Bittner2011; Costa-Lobo and Curtice, Reference Costa-Lobo and Curtice2014; Garzia, Reference Garzia2014) and Britain has not been excluded from these trends (Clarke et al., Reference Burch and Holliday2004; Evans and Anderson, 2005). The early post-election analysis suggests that the relative attractions of David Cameron and Ed Miliband as Prime Minister most probably weighed very significantly in the balance. Interestingly, although Miliband’s personal ratings were consistently well below those of Cameron after 2010, he was widely held to have performed surprisingly well in the 2015 campaign; Labour’s focus on Miliband was remarkably high (other leading figures in the party, such as Shadow Finance Minister Ed Balls and Shadow Home Secretary Yvette Cooper were almost invisible by comparison in the national campaign), and his popularity with voters did show some evidence of improvement. Nevertheless, this was an improvement from a very low baseline, and when it came to the final vote on 7th May, the ‘Miliband factor’ seems to have weighed on the minds of many voters. A Greenberg-Quinlan-Rosler poll taken immediately after the election found that the belief David Cameron would make a better Prime Minister than Ed Miliband was the third most frequently cited reason for voting Conservative (Greenberg-Quinlan-Rosler, Reference Goetz2015), whereas an Ashcroft poll revealed that some 71% of those who voted Conservative thought Cameron would make the best Prime Minister, compared with just 39% of those who voted Labour feeling that Miliband would do so (Ashcroft, 2015). This suggests that those who supported Labour tended to do so in spite of the party leader, whereas those preferring the Conservatives often did so because of their party leader. In 2010 and 2015, at least, the Labour vote was primarily a party vote, whereas the Conservative vote was to a far greater extent a personal vote.

The party face

In respect of his relationship with the Conservative Party, Cameron has embraced the Thatcher–Blair model to the extent that he has sought wherever possible to demonstrate that he leads rather than follows. Indeed, this is where the concept of presidentialization becomes especially relevant, because it entails the stretching of autonomy between leader and followers. Indeed, it may even be deemed necessary for a leader to ‘take on’ his or her party at times, especially when it is considered important to show that the party is changing. Blair famously did this when leader of the Opposition in 1994 by confronting his party over the need to revise Clause IV of the party constitution, which had hitherto committed it to seeking the public ownership of the means of production, distribution, and exchange. Between 2005 and 2010, Cameron similarly challenged his party to re-establish a strategically essential position in the electoral centre ground of British politics. Cameron’s predecessors since 1997 had essentially followed the Thatcherite recipe for electoral success – a mix of populism (on law and order, on immigration, and on Europe) and neo-liberalism (a low-tax, lightly regulated, small-state economy). Any attempts to try anything different before Cameron came along were half-hearted and hardly noticed: neither William Hague nor Iain Duncan Smith (who both had to worry about leadership challenges) nor indeed Michael Howard (who did not), really believed in an alternative strategy or in their ability to sell one, choosing instead to fight elections on those few issues where they believed they had at least some small advantage over Labour. The results were disappointing, to say the least: surveys consistently showed that Conservative leaders were derided or distrusted or both, whereas the Party was seen by voters as not only out of touch but stranded way out on the right of the ideological spectrum; Labour enjoyed huge leads where it counted most (the economy, health, and education) and even those Tory policies that did appear to resonate with the electorate proved less popular once they had the Party’s label attached to them. That the Tories lost once again in 2005, then, came as no surprise (Norton, Reference Norton2005; Bale and Webb, Reference Bale and Webb2011). In the light of this, the challenge that David Cameron faced was the need to change the toxic ‘Nasty Party’ brand that the Conservatives had earned for themselves through their Thatcherite strategy. He sought to do this by shifting the policy emphasis of the party to more socially liberal but – initially – less economically liberal terrain, while changing the social profile of the parliamentary party. In many ways, sections of the parliamentary and grassroots party were often less comfortable with the various reforms that Cameron introduced to the process of candidate selection in order to get more women and ethnic minority MPs returned to the House of Commons, than they were with the embracing of substantive policy themes such as social justice or environmental concern (Childs and Webb, Reference Clemens2012). However, although he was afforded a wide degree of latitude by his followers because of their desperation to avoid a fourth successive general election defeat, it was also valuable to his wider public image that he could on occasion demonstrate his willingness to take ‘tough decisions’ in the face of criticism from (Thatcherite) sections of his own party that did not appreciate the new line. In similar vein, Cameron was not averse to revealing a capacity for ruthless management of wayward colleagues (Jones, Reference Jones2008: 112). Indeed, he sacked or threatened to sack a number of shadow ministers and MPs deemed to have stepped out of line or performed weakly (including former Party Chairs Francis Maude and Caroline Spelman), while also obliging several MPs implicated in the parliamentary expenses ‘scandals’ of 2009 to retire from the Commons at the 2010 election.

That said, the relative latitude Cameron was granted by his parliamentary followers before the 2010 election diminished afterwards. It became increasingly clear that the Prime Minister could not count on unquestioning party loyalty or policy agreement, nor assume that Conservative MPs would always follow the whip. His standing with the electorate did not prevent a decided tendency to rebel against the party line by Conservative backbenchers. He always had some internal party critics, of course – and some of these blamed Cameron for failing to deliver an overall parliamentary majority in the 2010 election. Many of these were on the Thatcherite right and inclined to the view that Cameron’s strategy that was ostensibly designed to enhance the party’s appeal to the electorate was fundamentally flawed. The new Chairman of the party’s parliamentary party selected in 2010 (the ‘1922 Committee’) was Graham Brady, a known critic of the coalition deal with the Liberal Democrats (as were his deputies). Such critics worried about the social liberalism they saw in the coalition’s policy, particularly on issues such as policing and prisons, as well as Europe and constitutional reform. The backbench tendency to complain about aspects of government policy was doubtless exacerbated by the frustrated career ambitions of those who failed to become ministers, or ceased to be ministers – especially when fed by a sense of grievance that they might only have been denied a place in government by the presence there of Liberal Democrats. It is therefore interesting to observe that the new government established an unwanted record for experiencing the most rebellious first session of any Parliament since 1945: there were rebellions by government backbenchers in 54% of Commons votes between May 2010 and November 2011, the only session in which such a majority has occurred. Fascinatingly, moreover, it was not just the Liberal Democrats who were inclined to vote against the line that the government whips wanted them to support: Conservative MPs broke ranks in 35% of whipped votes, Liberal Democrats in 28%. Overall, some 116 out of 306 Conservative MPs (38%) had rebelled by November 2011, 59% of whom were drawn from the ranks of those who were first elected to Parliament in May 2010 (Cowley and Stuart, Reference Crossman2011).

Looked at one way, this is of course all highly pertinent to the presidentialization thesis in so far as it attests to the growing mutual autonomy of leader and party. Indeed, the paradox of coalition government was that it actually served to enhance the Prime Minister’s ability to act independently of his own party, for even if some of Cameron’s own party colleagues chose to vote against the party line, he could generally be sure of retaining his parliamentary majority because of the additional support of Liberal Democrats. The latter could even act as a lightning conductor of sorts against criticism from his own backbenchers, as he was able to claim that he was reluctantly compelled to implement certain policies as the price of coalition. However, the result of the 2015 general election has altered the context, and may have made Cameron more vulnerable to dissent and rebellion from his own party. For one thing, now that his former Liberal Democrat partners have been consigned to Opposition once again, the government’s overall majority has been reduced from 76 to 12 votes in the House of Commons. Plainly, this gives dissidents within his party the potential to be much more disruptive – and there are most certainly issues on which they might prove inclined to challenge the governing majority, the EU membership referendum planned for 2016 or 2017 being the most obvious case in point. An early sign of this occurred in June 2015, when Cameron appeared to resile from a public demand that ministers should resign from the government if they wished to campaign against continued membership of the EU, even after new terms of membership had been negotiated. He was widely reported to have been forced into this climb-down by pressure from Tory backbenchers who argued that MPs and ministers should be allowed to ‘vote with their consciences’ on this issue, as party leaders had permitted them to do on the occasion of the first British referendum on EU (or rather, EEC) membership in 1975 (Coates and Elliott, Reference Cowley and Stuart2015).

Furthermore, there have been other interesting signs that the parliamentary party would be seeking to flex its political muscles to a greater extent than in the 2010–15 parliament. During the election campaign, when the opinion polls were unanimous (if incorrect) in pointing to a second consecutive Hung Parliament, it was reported that Cameron would be obliged to include the 1992 Committee Chair Graham Brady in any team charged with negotiating a new coalition deal (Boffey et al., Reference Boffey, Helm and Cowburn2015). Even after it was known that there would once again be a single-party Conservative administration, Cameron hinted that the 1922 officers would play a greater role in helping to shape policy (Watt, Reference Watt2015). This may or may not prove to be the actual case, but it does at least suggest that he is acutely aware of the precariousness of his parliamentary majority, and is accordingly prepared to acknowledge that he will have to cede more ground to his backbench critics. This all seems to be consistent with George Jones’ ‘elastic band’ of prime ministerial power tightening up once again to restrict the leader’s scope for independent action. This is where we run up against the inherent limits of the presidentialization phenomenon, and are reminded that the United Kingdom remains a parliamentary system in which parties can still limit the autonomy of their leaders. The irony is that Cameron may have been more ‘presidentialized’ in terms of the relationship he experienced with his party during the period of coalition government than when ostensibly in control of a small Tory majority administration.

Interestingly, Labour in opposition under Ed Miliband showed few if any signs of reversing the movement towards a more leader-centred way of operating that had become evident in the New Labour era. The fact that Miliband only won an extremely narrow victory over his older brother David in the party leadership election of 2010, and what is more, that he only did so because he was more strongly supported by affiliated trade unionists, but not by individual members or the party’s elected representatives, might have made his position seem somewhat tenuous. Under such circumstances, it would not have been surprising if he had proved to be less challenging towards his party, and more inclined to cautiously build consensus. Indeed, all the more so in view of the low esteem that the public as a whole seemed to hold him in, which meant that he had little sense of personal authority. However, this was not the spirit in which Ed Miliband sought to lead his party.

We have already noted how surprisingly leader-centred Labour’s general election campaign of 2015 proved to be – perhaps precisely because Miliband and his advisers were acutely conscious of the need to confront head-on the frequent Tory charge that he was a ‘weak’ leader, they went out of their way to present him to the public at every opportunity; to an extent this may have worked, for he won plaudits for being an able debater, and his public approval did improve during the campaign (although ultimately he remained well behind Cameron in the estimation of voters). However, more than this, it should be said that well before 2015 Miliband had already taken several notable initiatives designed to stamp his authority over, and scope for autonomy from, the party. First, on being elected leader, he was constrained by Labour’s traditional rule that, when in Opposition, members of the Shadow Cabinet had to be elected by the parliamentary party; however, he managed to persuade his fellow MPs of the need for a rule change that would permit the leader a free hand in selecting anyone he chose for these front-bench positions (Bale, Reference Bale and Webb2015: Ch.3). Moreover, Miliband proved every bit as inclined to handpick his own advisers and to locate his power within this tight circle, rather than in the party’s national headquarters, to which he was only an occasional visitor. Most significantly, the nearest he came to a Blair-like ‘Clause 4 moment’ concerned the re-writing of the party’s leadership election rules. Ironically, and in spite (or perhaps because?) of predictable allegations that he was especially beholden to the unions, which had secured his victory in the 2010 leadership contest, Ed Miliband decided to challenge the party (or, at least, part of it) by abolishing the ‘electoral college’ that gave the party’s MPs/MEPs, its individual members, and its affiliated union members one-third of the vote each in choosing leaders. The proximate cause of this reform was a row over union influence in the selection of a parliamentary candidate in the Scottish constituency of Falkirk in the summer of 2013; although candidate selection has no direct connection with the business of leadership election, Miliband seized on the opportunity to re-cast the party–union relationship in the boldest reforms for 20 years. Despite heavy criticism from some of the affiliated unions (especially the UNITE union that was at the heart of events in the Falkirk constituency), Miliband’s proposals gained the approval of a special party conference that was convened in March 2014. Henceforward, the leadership college will be replaced with a simple one-member, one-vote ballot of all members of the party. This will not only include all current individual members, but also those members of affiliated trade unions who actively choose to opt in to pay a political levy to Labour and to declare themselves ‘affiliated supporters’ of the party (the ‘double opt-in’). Quite apart from anything else, this reform plainly creates the potential for future Labour leaders to claim a personal mandate conferred by a popular plebiscite.

In summary, even under a ‘weak’ and unpopular leader like Ed Miliband, the Labour Party maintained the pattern of leadership by a group of close advisers and colleagues working with the Leader in such a way as to maximize autonomy from the rest of the party, whereas David Cameron was able to exploit the experience of coalition to enhance the autonomy he enjoyed within his own party. However, there was of course a reverse side to the latter equation, for coalition also represented a limit on the Prime Minister’s autonomy within the government.

The executive face

Cameron’s preference for working closely with a small coterie of confidants and advisers resembles Blair’s well-known taste for ‘sofa government’. Conservative policy formulation, campaign strategy and the management of the party before the 2010 election were largely the prerogatives of Cameron, George Osborne (Shadow Finance Minister), Steve Hilton (Chief Campaign Strategist), Andy Coulson (Communications Director), Ed Llewellyn (Cameron’s Chief of Staff), and James O’Shaughnessy (Head of Policy). Although a few trusted front-bench colleagues such as Michael Gove and William Hague were sometimes drawn into his inner circle, it was this personal staff of Cameron’s that really constituted his governing coterie in office, and indeed continues to do so after the 2015 election.Footnote 3 Osborne apart, the unelected officials only have influence through their relationship with David Cameron – not the Conservative Party – and their influence is certainly greater than that of most Cabinet politicians.

However, there is one major fact of political life that was very different for David Cameron in 2010 compared with previous British Prime Ministers: he was the leader of a coalition government rather than a single-party administration. As leader of a coalition, Cameron had to manage relations with the Liberal Democrats and especially their leader, the Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg. The relationship between the two-party leaders was especially critical to the stable and effective operation of this coalition – a fact which in itself tended to enhance the autonomy that both enjoyed vis-a-vis their respective parties, as has already been pointed out. Cameron and Clegg co-chaired the Coalition Committee, a body comprising an equal number of Tories and Liberal Democrats, which met each week to manage the government agenda (Cabinet Office, Reference Carter and Poguntke2010). Liberal Democrat ministers were either chair or deputy chair of each cabinet committee (indeed, Clegg himself chaired five out of nine cabinet committees), and policy disagreements were referred to the Coalition Committee for resolution. The realities of working in a coalition encouraged some observers to express the view that anything resembling a presidential style of managing the executive would become a thing of the past (Nelson, Reference Niedermayer2010).

This was almost certainly a distortion of the truth on two counts. First, it is far from accurate to describe the era before 1997 as some kind of Golden Age of cabinet government in the United Kingdom: after all, there were many lamentations of the decline of cabinet government as far back as the 1960s, at least (see, for instance, Crossman, Reference Evans and Andersen1985). Second, it is an equally wild exaggeration to claim that the country experienced a return to the pure practice of cabinet government between 2010 and 2015. For one thing, a modified form of ‘bilateralism’ still seems to persist. Cameron’s cabinet was not the key arena for decision-making. Committee deliberation continued to be shaped by prior bilateral negotiations between the Prime Minister and specific ministers, although he was obliged to take into account the ruminations of the Coalition Committee, something which no peacetime Prime Minister had to do since the National Government of the 1930s. For another, it is recognized that the core of the Cabinet was represented by ‘the Quad’ – that is, the four key ministers who set the direction and where necessary arbitrated on the details of domestic policy: Cameron and his Finance Minister (Chancellor of the Exchequer) George Osborne, Nick Clegg, and Osborne’s deputy (i.e. the Chief Secretary to the Treasury) Danny Alexander. That is, two Conservatives and two Liberal Democrats. Thus, the experience of coalition government, whereas enhancing the party leader’s autonomy from his party simultaneously served to restrict his scope for independent control within the executive. Nevertheless, although it cannot be said that David Cameron exerted the degree of control over the executive that a genuine president would, he has operated through a personal coterie of advisers who constitute a critically important resource and counterweight to the influence of other actors. He is unquestionably the predominant actor within the Cabinet: power remains highly asymmetric within the British government. According to Bennister and Heffernan (Reference Bennister and Heffernan2012: 778):

Cameron and Clegg both possess institutional and personal resources, but Cameron remains the predominant resource-rich actor, so at this stage in the coalition government we can observe that no formal, substantial change in the role of Prime Minister has been enacted. Cameron’s predominance, by leading a coalition, is partially constrained by Clegg, but he too constrains Clegg. This Prime Minister, then, can be predominant even when he is constrained in significant ways by the imperatives of coalition government. Cameron is presently no more constrained than a Prime Minister who is faced with a pre-eminent intra-party rival with a significant power base.

It might be added that it is hard to identify significant features of the coalition government’s programme that demonstrate the Liberal Democrats’ ability to win concessions from Cameron (Wright, Reference Wright2011); on the contrary, the overwhelming emphasis of the government on the economics of austerity was entirely consistent with the Conservatives’ electoral platform in 2010, but strikingly different to that on which the Liberal Democrats campaigned. In addition, there were several highly visible disappointments for the Liberal Democrats in terms of their legislative aspirations, especially in terms of their hopes for constitutional change (e.g. electoral reform, House of Lords reform), and their concerns over Tory plans to introduce major change in the National Health Service.

In summary, we can say that the major features of presidentialization remain pertinent in the United Kingdom, and in many ways did so even under circumstances of coalition government. Cameron only ascended as quickly as he did to the party leadership because of his electoral appeal, and this was central to the general election campaigns that the party ran in 2010 and 2015; although his position within the executive was more constrained by the experience of coalition government than would have been true of a presidentialized leader in Tony Blair’s position, most of the key actors were part of his own personal coterie, and he was still able to operate as a predominant prime minister; and while he continued to have the broad support of a majority of his parliamentary backbenchers, the level of dissent reached unprecedented levels. Taken together, we would maintain that these all speak to the growing mutual autonomy of the leader and his party, which seems to us to be the essence of the presidential idea: a model according to which the leader has greater power within the executive than one would expect of an ideal typical prime minister, while enjoying greater autonomy in the electoral arena and from the legislature. That said, the limits of the presidentialization phenomenon are likely to be demonstrated in the 2015–20 Parliament, as David Cameron will have to depend on a small Conservative majority, which includes a determined and vociferous band of backbench critics of the Prime Minister.

Conclusion

Even the experience of changing governing contexts does not seem to have substantially altered the processes of presidentialization of politics in these almost paradigmatic cases of consensus and majoritarian democracy. In Germany, the shift from a small red–green coalition to a Grand Coalition represents an interesting test case for the presidentialization thesis. After all, it might be argued that the red–green government provided a perfect political context for a Chancellor like Gerhard Schröder to assume strong leadership and try to govern very much past his own party and, above all, past his coalition partner. Bluntly, the Greens had no alternative coalition partner to turn to. In addition, they had to accept some very painful policies (like the Kosovo war) at the beginning of their governmental incumbency which made their future fairly dependent on governmental success. The extent of Schröder’s presidentialized leadership style was epitomized by his lonely decision to initiate the process leading to an early federal election.

Angela Merkel, on the contrary was forced into a Grand Coalition with an almost equally strong Social Democratic party after a very disappointing election result. After painstakingly long coalition negotiations some analysts expected that Angela Merkel would be little more than a chief negotiator who would be decidedly constrained by the will of the extra-parliamentary leaderships of the coalition partners SPD and CSU. Famously, CSU leader Edmund Stoiber remarked at the end of the talks that there was ‘no such thing’ as the ‘Richtlinienkompetenz’, that is, the constitutionally enshrined right of the German Chancellor to determine the guidelines of policy.

Yet, the experience of Grand Coalition government has proved the pundits wrong. Angela Merkel has clearly been able to assume a very elevated role in the German policy-making process. Although she differs in style from Gerhard Schröder’s assertive approach, it can safely be argued that Merkel’s control over policy was and is equally strong. This corroborates the argument that the presidentialization of executive leadership is not just the result of a specific leadership style of one particular incumbent. Rather, it points towards the presence of structural factors that tend to shift the mode of governing towards a more presidentialized logic. To be sure, Merkel’s acquisition of a dominant position within the Grand Coalition was aided to a certain degree by the dismal state of the Social Democrats throughout the four years of joint government. From the 2005 election until shortly after the 2009 Bundestag elections they had five party chairs (Müntefering, Platzeck, Beck, Müntefering, and Gabriel) and suffered from fairly severe internal battles over their future programmatic profile. However, in a situation where the coalition partner is comparatively weak, the Chancellor’s own party may become particularly assertive. All the evidence is to the contrary, though. The subsequent Christian–Liberal coalition did not necessarily provide Chancellor Merkel with better conditions to dominate the government and hence her own party. After all, a stronger opposition camp (SPD and Greens began to be increasingly successful in Land elections) confronted her with new potential veto players in the Bundesrat. Nevertheless, the structurally induced supremacy of the Chancellor continued and was, if anything, exacerbated by the financial crisis and continued into the next Grand Coalition.

The power and autonomy of British prime ministers have fluctuated over the same period of time, largely for contingent reasons. Tony Blair’s personal resources eventually dwindled from 2003 onwards as the unpopular war in Iraq took its political toll, whereas Gordon Brown never enjoyed remotely the level of personal standing with the electorate that Blair had before 2003: indeed, it should always be remembered that Gordon Brown never succeeded in leading his party to a general election victory and to that extent never earned the personal political ‘mandate’ that Blair won on three occasions between 1997 and 2005. Subsequently, David Cameron emerged as a new opposition leader in Blair’s presidential mould, and duly earned an electoral mandate in 2010. However, he found himself in the (for Britain) rare situation of leading a peacetime coalition government at Westminster. Although this constrained his intra-executive power to some extent, he still managed to predominate and to operate in a presidential style largely through a personal coterie of advisors. At the same time, he found himself, as presidential figures often do, beset by a fractious legislative following: it is evident that a leader who attempts to ‘govern past his party’ can find autonomy cuts both ways. Almost paradoxically, however, the very fact of being able to rely on his coalition partners seemed to enhance his ability to face down internal Tory criticism. Now that he finds himself in charge of a single-party administration this tactical advantage has disappeared, and given the smallness of his overall parliamentary majority, he may find himself more constrained by his party than was the case before 2015 – while enjoying greater predominance within the executive.

Clearly, the evidence assembled on these two European cases mixes structural aspects with developments that are highly contingent on circumstances, events and the agency of individual leaders. Yet, it is clear in both Germany and Britain that structural changes underpin the developments we have outlined, regardless of short-term contingencies. German Chancellors and British prime ministers have been increasingly able to mobilize power resources which allow them to govern more independently of their own parties and their coalition partners, and this seems to hold across a variety of circumstances. However, this does not necessarily lead to an enhanced steering capacity of the core executive. Even though the governance debate may have overstated its case and the central authority of the state may not have been ‘hollowed out’ to a great degree (Goetz, 2008), the ability of national governments to achieve desired goals is constrained by many factors, including the global economy and European integration. Yet, these growing constraints on the ability of governments to achieve desired outcomes often go hand in hand with the increasing autonomy of national leaders within executives and from their parties.

Acknowledgement

None.

Financial Support

The research received no grants from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agency.