Introduction

In the consciousness of post-communist societies and in political discourses, which affect this consciousness to the greatest extent, the concept of patriotism often takes a mythologized form. It includes new, deformed meanings and clearly valuing connotations, which are often subordinated to ideological and political preferences.Footnote 1 Consequently, the concept usually evokes emotions (positive or negative) and is used to categorize people (as ‘bad’ and ‘good’ patriots) rather than to diagnose and promote attitudes that might contribute to present and future challenges. It is rarely mentioned that patriotism can be a kind of orientation acquired in the process of socialization (Druckman, Reference Druckman1994, 43–68) and thus determine the views, ideas, and perceptions of reality shared by entire generations. Various visions of patriotism clash in the public space. While some stress the emotional attitude to the homeland, others focus on positivist civic activity and fulfilment of duties towards the state. According to Mouffe (Reference Mouffe2013, 43), we should accept the fact that national forms of attachment are unlikely to disappear, at least in the foreseeable future. It is worth looking at the category of patriotism in a more socially useful way, treating it as a factor that can play an important role in the process of building a civil society. The socially accepted meaning of the concept of patriotism also evolves along with a normative change, which is generally faster with every new generation (Inglehart Reference Inglehart1977; Karvonen et al., Reference Karvonen, Young, West and Rahkonen2012). Some approaches, referred to as civil (Straughn and Andriot, Reference Straughn and Andriot2011), constructive (Schatz et al., Reference Schatz, Staub and Lavine1999), and active (Bar-Tal, Reference Bar-Tal1993, 49) patriotism, can help to better understand the changing attitudes of society and also promote (e.g. through civic education programmes) the kind of behaviour in the public sphere that can significantly contribute to improving the quality of new democracies, both at the local and central levels.Footnote 2 Paraphrasing Vladimir Tismăneanu's words, it can be said that the functionality of civic attitudes in the countries of East-Central Europe is still at stake in the political game and ‘the main issue is the nature of the emerging political communities’ (Reference Tismăneanu1998, 5). In this part of the continent, the first generation of citizens brought up under the conditions of a democratic state, known as democratic natives, is beginning to speak (Marzęcki, Reference Marzęcki2017). Their historical experience and the social, economic, and cultural conditions in which they grew up (democracy, free market, European integration, globalization, and technological revolution) shape a new model of a citizen who – paradoxically – simultaneously becomes the ‘hero’ of two discourses on the future of democracy. On the one hand, they give hope for a better world in which values such as responsibility, solidarity, respect, trust, respect for the law, understanding, and cooperation play a central role. On the other hand, there are concerns that young people will turn away from democratic institutions and adapt the postmodern lifestyle, thus constituting a threat to the ‘democracy of tomorrow’ (Forbrig, Reference Forbrig and Forbrig2005; Marzęcki and Stach, Reference Marzęcki and Stach2016). Young people also have to face many modern economic risks (e.g. job insecurity), which also determine the level of their socio-political participation (Monticelli and Bassoli, Reference Monticelli and Bassoli2018). However, establishing a democratic political system is mainly based on encouraging the development of political culture. Though undoubtedly mentally anchored in the old system, the young generation brings a significant range of new, previously absent values to a social life. In this sense, it can become a catalyst for changes leading to a ‘more civil society’. Recognizing this historic moment (and the opportunity) should be a challenge for democratic institutions.

This paper has two main objectives. The descriptive objective is to describe a sense and understanding of patriotism among young people based on the empirical data collected and using the example of Polish students. The data are used to answer the question about the prevailing pattern of patriotic attitudes among students and their ideas about patriotism. Do students think that patriotism is limited only to the cognitive and emotional sphere, or does it also require social, political or civic engagement in a behavioural sense? Which activities, and to what extent, are seen as related to patriotism? Answers to these questions should help to better understand the criteria of patriotic self-identification: what minimum criteria should be met – according to students – in order to be considered a patriot? The explanatory objective of the paper is to answer the question of whether and to what extent the feeling of being a patriot and the way of understanding patriotism influences the odds of activity in the socio-political environment. The answer should shed light on the problem of the constructive potential of student patriotism. The general hypothesis adopted assumes that people who strongly identify themselves as patriots more often engage in local community activities. A statistical analysis is conducted to verify the correlations between detailed variables describing the contemporary student perception of patriotism and its impact on the level of social participation.

The following sections of this paper contain: (1) a review of theoretical concepts which define patriotism as a multi-dimensional phenomenon serving various (positive and negative) social functions; (2) a description of research methods applied; (3) characteristics of Polish students' patriotism in relation to data collected in a survey; (4) statistical analysis of correlations between variables describing students' sense and understanding of patriotism and civic activity (for local communities). Finally, the author outlines the main findings.

In search of a functional approach to patriotism

Attempts to define and thus better understand the word ‘patriotism’ usually boil down to the analysis of its dictionary definition and etymology (Brzozowska, Reference Brzozowska2014, 44–49), explanations based on a description of historically observed attitudes of individuals and social groups (Walicki, Reference Walicki1991), as well as – particularly in western European and American scientific literature – theoretical considerations and operationalization of the empirical construct (Conover and Feldman, Reference Conover and Feldman1987; Kosterman and Feshbach, Reference Kosterman and Feshbach1989; Karasawa, Reference Karasawa2002; Huddy and Khatib, Reference Huddy and Khatib2007).

Patriotism – to put it more clearly – has many dimensions (Abbott, Reference Abbott2007; Finell and Zogmaister, Reference Finell and Zogmaister2015) and is defined in many aspects (Ariely, Reference Ariely2018), yet a detailed analysis of the scientific interpretation of this concept indicates specific regularities and tendencies. Most contemporary definitions are descriptive and are about emphasizing an individual's emotional approach towards his or her country (more specifically his or her culture, values, territory, political system, history, national myths, government, politics, and society) (Theiss-Morse, Reference Theiss-Morse2009, 23). The affective aspect of the attitude towards one's country (attachment and loyalty) is often emphasized as a defining element of patriotism (Druckman, Reference Druckman1994). Patriotism is sometimes described as an important indicator of social identity that helps citizens to make self-categorizations. Hence, some definitions stress two elements which constitute – as Leonie Huddy and Nadia Khatib say – ‘broad agreement on the meaning of patriotism’ (Huddy and Khatib, Reference Huddy and Khatib2007, 63): (1) positive identification and (2) affective attachment to one's country (by feeling emotions such as love for the country and pride in the country's achievements). These are also expressed by emotional reactions to national symbols (Schatz et al., Reference Schatz, Staub and Lavine1999, 152; Gangl et al., Reference Gangl, Torgler and Kirchler2016, 868; Wolak and Dawkins, Reference Wolak and Dawkins2017, 392). In the context of the approach adopted in this paper, it is more valuable to examine the problem from an even broader perspective, which assumes that ‘patriotism is a psychological phenomenon that has cognitive, affective, and behavioural components’ (Bar-Tal and Staub Reference Bar-Tal, Staub, Bar-Tal and Staub1997, 6–7). In their concept of symbolic and instrumental involvement, Schatz and Lavine (Reference Schatz and Lavine2007) also point out these three forms of attitudes towards the nation (and their diversity).

Some approaches emphasize the unambiguously positive nature of patriotism, comparing it with clearly destructive attitudes from the social point of view: nationalism and chauvinism (Heaven et al., Reference Heaven, Rajab and Ray1985; Ray and Lovejoy, Reference Ray and Lovejoy1986), which ‘stand in the way of the development of a civil, democratic society’.Footnote 3 This is the perspective of Druckman (Reference Druckman1994), who writes that patriotism involves a specific commitment, that is, the readiness to sacrifice for one's own nation, while nationalism implies selective perception of the category of community and involves exclusion of those who do not meet the criteria of belonging to the nation. As such, it is based on hostility towards others (Druckman Reference Druckman1994, 47–48). Patriotism is defined most often as a psychological state of ‘love for’ and ‘pride’ in one's own country and society, in contrast with nationalism, which is based on the belief that one's own country should dominate and discriminate other countries and their nations (Federico et al., Reference Federico, Golec and Dial2005; Gangl et al., Reference Gangl, Torgler and Kirchler2016, 865). Literature contains dichotomous connotations referring to the concept of ‘healthy’ patriotism and ‘destructive’ nationalism (Schatz et al., Reference Schatz, Staub and Lavine1999), however – as Krzysztof Jaskułowski writes – we can also find a strongly moralistic distinction between a ‘good’ nationalism (civic nationalism), which is associated with the West, and a ‘bad’ nationalism (ethnic nationalism) typical for the non-Western world (Plamenatz, Reference Plamenatz and Kamenka1976; Jaskułowski, Reference Jaskułowski2010, 290).

Other authors emphasize the dual nature of patriotism by describing two of its versions: functional and dysfunctional. For example, Ariely (Reference Ariely2018) indicates that patriotism is perceived as crucial for the integration of minorities and strengthening social cohesion. Other researchers point to a series of positive social effects of patriotism, including the fact that it reduces social conflicts, promotes active citizenship (Müller Reference Müller2007; Soutphommasane Reference Soutphommasane2012), and political participation (Bar-Tal Reference Bar-Tal1993, 59), and even strengthens a sense of duty when it comes to paying taxes (Gangl et al., Reference Gangl, Torgler and Kirchler2016). Daniel Bar-Tal draws attention to the functions of patriotism in the life of individuals (it strengthens their sense of belonging and supports their social identity) and groups (it contributes to social integration, strengthens group cohesion, mobilizes members of the group to act on its behalf, encourages them to make efforts, and devote their time and money for the group) (Bar-Tal, Reference Bar-Tal1993, 55–58). In this sense, patriotism can be treated as a kind of social capital that contributes to pro-social behaviour (Rothstein, Reference Rothstein2003; Gangl et al., Reference Gangl, Torgler and Kirchler2016, 869). It is highlighted, however, that patriotism may give rise to fanaticism, chauvinism, and conflicts, and it may thus become a tool for marginalizing and excluding minorities from ‘our’ circle (Kateb, Reference Kateb2006). In addition to postulates which draw a clear division between patriotism and ethnocentrism (Bar-Tal, Reference Bar-Tal1993, 51–52), it is rightly stated that both phenomena can be closely related to and permeate one another. Patriotism (in the positive sense) can be monopolized by certain groups that use it instrumentally, subordinating it to a particular ideology, goals or means of action. This understanding of the concept of patriotism contradicts the one outlined earlier, whose social utility has been verified (empirically) mainly in American society. However, it seems to be less useful in describing European, particularly post-communist, societies. In countries such as Poland, patriotism sometimes functions in public awareness and public discourse as a factor strengthening negative behaviour and attitudes, such as intolerance, dislike for others, and exclusion. However, it is difficult to categorize them explicitly as nationalism, chauvinism or ethnocentrism. A useful solution to this dilemma – on theoretical and empirical grounds – may be the proposal to distinguish between, so-called, blind patriotism and constructive patriotism. This distinction was made by Staub (Reference Staub, Bar-Tal and Staub1997), who was the first to put two key questions: (1) Is patriotism connected with negative attitudes towards groups of others?; and (2) Is patriotism associated with uncritical loyalty to one's own people? Although both orientations have an analogous foundation (positive identification and affective attachment to one's own country/nation), they are characterized by a completely different perception of the surrounding world. Both models distinguish primarily between factors determining an individual's loyalty to his or her national community and country and the divergent ways of their valuation (or even hierarchization). Blind patriotism is characterized by ‘uncompromising attachment to one's country, which is expressed in unilaterally positive evaluations, faithful loyalty and intolerance of criticism’ (Schatz et al., Reference Schatz, Staub and Lavine1999, 153). In this case, a patriotic attitude is a kind of ‘sentimental attachment’ to the country (Kelman and Hamilton, Reference Kelman and Hamilton1989) and uncritical in-group loyalty is accompanied by negative beliefs about groups of ‘others’ (out-groups) (Finell and Zogmaister, Reference Finell and Zogmaister2015). Constructive patriotism implies the kind of tie with a country that is characterized by ‘critical loyalty’ which helps to oppose discrimination and supports the desire to implement positive changes (Schatz et al., Reference Schatz, Staub and Lavine1999, 153). This kind of ‘critical patriot’ shares the democratic belief that all practices of other people (compatriots) that violate fundamental national precepts or harm the long-term interests of the nation/country must be opposed (Schatz et al., Reference Schatz, Staub and Lavine1999, 153; see also the concept of distinction between authoritarian and democratic patriotism: Westheimer, Reference Westheimer2006). Patriotic activity is to promote the well-being of the entire nation (in the inclusive sense) and the common good of all citizens regardless of their ethnic origin or social status (Finell and Zogmaister, Reference Finell and Zogmaister2015, 189). In this sense, ‘constructive patriotism embodies important aspects of good citizenship’ (Sekerdej and Roccas, Reference Sekerdej and Roccas2016, 500).

Research methodology

The conclusions presented are based on data collected during a survey (a self-administered questionnaire) which was carried out on a sample of Polish students in 2015–16 (answers to the open question come from an analogous study carried out in 2018Footnote 4). Due to the research methodology applied in the study (e.g. sampling), the reference group is the environment of Polish students. It is worth noting that students are often investigated to test hypotheses related to the concept of patriotism, especially in American political science (Schatz et al., Reference Schatz, Staub and Lavine1999).

The author of this paper (as the principal investigator) has applied stratified sampling. The studied sample consisted of 810 students from nine different public universities in Poland. Universities were chosen on purpose in order to ensure a relatively highly diversified research sample. During the random stage, a multi-stage sampling was used. The first stage of random selection was among departments, the second stage was among institutes/chairs, the third among majors, and the fourth among classes. The average age of the respondents was 22. Ninety-seven per cent of the surveyed students were aged between 18 and 25. The most important socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents correspond to the characteristics of the student environment developed by the Central Statistical Office in Poland (as of November 2015).Footnote 5 Therefore, the conclusions presented can be considered representative of the population of students of public universities in Poland. It is worth emphasizing that the data may also give an incentive to formulate hypotheses explaining the behaviour of young people in Poland in general. In this sense, it is an incentive to initiate research aimed at explaining similar issues among other social groups.

Based on available theoretical findings and my own research results, I propose an operational definition of patriotism (multi-dimensional patriotic disposition). This kind of attitude binds the individual with the state and nation (own group) and contains three categories of components: (1) cognitive: patriotic self-identification; (2) affective: love for the homeland, a sense of pride; (3) behavioural: in the symbolic sphere, for example, displaying national symbolism and nurturing tradition, and also in everyday activities ‘that support democratic values and practices’ (Kahne and Middaugh, Reference Kahne and Middaugh2006, 606). From the perspective of the research problem, the most important thing is to determine the relationships between components 1, 2, and 3. Do cognitive and affective factors translate into pro-social and civic behaviours? Can/is experiencing patriotism be an important catalyst for the development of civil society, which is perceived to be very weak not only in Poland but also in other post-communist countries? According to conventional indicators of civic engagement, the position of Polish society is relatively unfavourable compared to other European countries. The European Values Study (EVS 2018) data show that the engagement of young Poles (18–25 years) in the activities of social organizations is rather low (18.3%) and similar to that in other post-communist countries (Slovenia is an exception; the low result of Spain is noteworthy; Table 1). Respondents were asked about both their membership and actual activity in various voluntary organizations: religious or church organizations; education, arts, music or cultural activities; trade unions; political parties or groups; conservation, the environment, ecology, animal rights; professional associations; sports or recreation; humanitarian or charitable organizations; consumer organizations; self-help groups; mutual aid groups, and other groups. Data on voluntary work in the last 6 months (in addition to the two exceptions mentioned) also show the gap between the so-called ‘old’ and ‘new’ European Union.

Table 1. The level of civic involvement in selected EU countries, in per cent

Source: EVS (2018). The table presents data for EU countries that participated in the EVS study.

At the same time, in the same group of countries surveyed in the EVS, young Poles declare the strongest sense of pride in being citizens of their country (Table 2). This shows that strong patriotic emotions do not translate into a higher probability of social work and civic activity (a definitely higher level of engagement is observed among young people who mostly declared moderate pride, that is, they responded ‘quite proud’: in Slovenia, the Netherlands, and Germany).

Table 2. A sense of pride in being a citizen in selected EU countries, in per cent

Source: EVS (2018).

Returning to the operational definition, I assume that a mature patriotic attitude also requires ‘devotion and loyalty, which imply possible action for the sake of the society and country’ (Bar-Tal, Reference Bar-Tal2000, 75). It is important for the definition of patriotism to take account of not only verbal declarations concerning activity and participation but also their actual manifestations. Civic activity is, therefore, a dependent variable. It can be defined as ‘participation aimed at achieving a public good, but usually through direct hands-on work in cooperation with others’ (Zukin et al., Reference Zukin, Keeter, Andolina, Jenkins and Delli Carpini2006, 51). The following question was used to measure this variable: ‘Have you been engaged in local community activities (district, municipality, village, parish, the nearest neighbourhood) over the last year?’. The aim of the analyses was to determine which factors describing student perception and expression of patriotism positively encourage students to take up civic activity. The results presented help to better understand the patriotic determinants of social activity up to a point. Therefore, similar research should be continued – primarily in post-communist societies – to assess the constructive potential of patriotism and to control its possible negative effects (its transformation into chauvinism, xenophobia, etc.). The construct of patriotic disposition proposed by the author may be considered too narrow, arbitrary or poorly justified. It cannot be ruled out that it should also be developed in the theoretical dimension. At the same time, the data and conclusions presented should be the starting point for similar analyses, extended by additional variables in the statistical model. This will allow formulating more detailed, practical recommendations for public institutions.

The patriotism of Polish students

The concept of patriotism in media debates in Poland sometimes has contradictory connotations. Arguments put forward often contain competitive meanings of the concept and the views of political opponents are usually rejected in advance due to antagonistic tendencies. Public debates are full of views that categorize patriotism as a negative phenomenon. However, the dominant attitude is the so-called romantic manifestation of patriotism, which has been shaped in a long historical and political process (the struggle for independence, two world wars, and the communist period after 1945) and determines a specific model of political culture. It involves a constant sense of threat to the state's sovereignty, which has not significantly decreased during the transformation period.Footnote 6 The agenda of contemporary public debate concerning patriotism and national identity is formed under the influence of patterns dominating in literature, art, and historiography, which frame the fatherland as a supreme value, sacralizing the national cause (Szeligowska, Reference Szeligowska2016). This valuable construct of patriotism is also rooted very strongly in educational programmes (e.g. history classes) addressed to young Poles which have become an instrument to develop attachment to the Polish nation among pupils (Jaskułowski et al., Reference Jaskułowski, Majewski and Surmiak2018; see also: Merry, Reference Merry2009). This broad socio-cultural background better explains the views of Polish students described in this paper.

It turns out that the concept of ‘patriotism’ mainly raises positive associations in respondents (a total of 89% of respondents) with almost half of them (49.3%) declaring that patriotism is a definitely positive phenomenon. It evokes negative connotations in less than four out of a hundred respondents (3.8%). Many different definitions of patriotism refer to the emotional ties that connect citizens with their home country or nation. This ‘interpretation’ is also dominant in the consciousness of students, who were asked how they understood this concept. Answers to this open questionFootnote 7 can be grouped into several categories describing different dimensions of the perception of patriotism:

a) emotional attachment to the country, which is expressed in the statement:

– an emotional relationship with the country (Poland)/nation (Poles) (examples of answers: love for the homeland, a strong feeling towards the homeland, for which our ancestors fought, the joy of being a Pole and celebrating important events in the country);

– a feeling of pride in being Polish (being proud of the country, being proud of the origin, pride in the country, ancestors, and history);

– respect for the country/nation and its heritage (respect for Polish history and tradition, for the country and for national symbols);

b) cognitive references: positive identification with the country/nation (being faithful to the country, identification with the country, a bond and a sense of unity, belonging to the nation).

Respondents rarely identify patriotism with an active – constructive – attitude in the public sphere, for example: striving for change for the better; undertaking activities for the benefit of the country; working for the homeland; undertaking activities for the sake of development (culture, economy); being responsible for the fate of the country; not only maintaining an emotional bond with the state but, above all, acting for its benefit; noticing mistakes; commitment, openness, tolerance. Occasionally, the associations had negative connotations, such as blind passion for the country and nationalism. A significant part of the answers concerned the past, history and the memory of people and events, for example, gratitude for what our ancestors did for the country, the memory of national heroes, and respect for national symbols. There were also answers indicating that patriotism is expressed in a proper representation of the country abroad, for example, caring for a good (real) image of Poland and Poles in dealing with foreigners; representing the country abroad in a decent manner. The last group of responses, which is worth mentioning due to the number of times they were repeated, are statements emphasizing readiness to defend the country in an emergency situation and to make sacrifices for the homeland, for example, showing respect for its symbols, defending the country when the need arises; fighting in defence of the homeland; declaring readiness to defend and sacrifice for the country; showing the ability to sacrifice for the country in the face of danger; declaring readiness to sacrifice, including the readiness to sacrifice one's life if needed, etc.

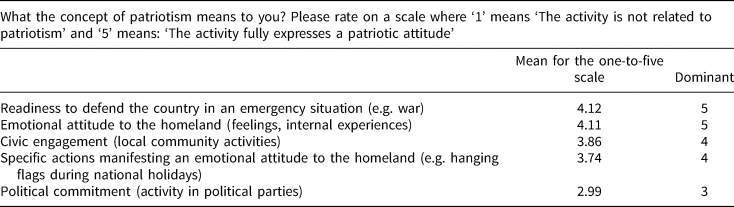

Student perception in this area is also confirmed and, at the same time, organized by the distribution of responses on the scale of understanding patriotism. This time, the respondents had the opportunity to determine the relationship between patriotism and particular civic activities. Table 3 summarizes the detailed results using the dominant and the arithmetic mean value calculated from the indications on the scale. It can be seen that patriotism is most often associated with the affective dimension of attitudes (an emotional attitude to the homeland: feelings, internal experiences) and a specific disposition for action, which, however, is purely declarative (readiness to defend the country in an emergency situation). In both cases, the mean value is more than 4.00 and the dominant is 5 (I definitely agree that the activity fully expresses a patriotic attitude). According to respondents, the patriotic attitude is often realized through civic involvement and symbolic activities (e.g. hanging flags during national holidays). Political activity, in turn, is more often treated as unrelated to patriotism.

Table 3. Patriotism and various aspects of citizens' activity

Source: Author's own study.

In order to estimate the scale of acceptance for the emotional dimension of the perception of patriotism (which was most frequently displayed in students' statements), a question regarding the emotional relationship with Poland (love for the country) was asked. The data collected indicate that 7 out of 10 respondents (71.9%) feel ‘love for their homeland’ but in most cases, this was not a definite feeling (46.6%). The lack of emotional ties with Poland is expressed by 16.2% of respondents, and extreme cases are rather marginal in this dimension (3.6%). It should also be noted that every tenth student has a problem formulating his or her own opinion on this issue.

Another important indicator of a patriotic attitude is a sense of pride in being a representative of a specific nation. Polish students almost unanimously (85.6%) admit that they are proud to be Polish. Only 5.3% of respondents are of the opposite opinion whereas 9% of the surveyed have no opinion on this matter. The survey questionnaire was designed to ensure identification of the sources of this pride during the analysis of respondents' answers. Students were asked to determine the degree to which they felt pride in a variety of situations on a 5-point scale. Table 4 presents the arithmetic means calculated from individual responses on the scaleFootnote 8 and the dominant suggesting the most frequently indicated answer. The statements given for assessment concerned two categories of situations:

(1) successes in sport and culture – which evoke a sense of pride to a much higher degree;

(2) important political events – which evoke a sense of pride to a much lower degree.

Students' attachment to national symbols is relatively strong. The survey shows that 72.4% of respondents feel proud at the sight of a Polish flag in a public place (with moderate grades prevailing: 39.4%), 14.8% of the surveyed have a different opinion and more than every tenth respondent (12.8%) has no opinion on this subject.

Table 4. A sense of pride in being Polish in certain situations

Source: Author's own study.

Another important indicator of a patriotic attitude is a sense of identification with a country or a nation (Table 5). Answers given by students generally confirm the well-known thesis about the so-called ‘sociological vacuum’Footnote 9 between the private sphere (family, friends) and the public sphere (state, nation).Footnote 10 The relationship with Poland is declared by 75.7% of the surveyed and with the nation by 73.2%. However, it must be suspected that these indications may be ritual to a certain extent as less than one-fifth of respondents declare a very strong identification in both cases. It is also worth noting that 20.4% of the surveyed students assess their relationship with Poland as weak. Moreover, 22.5% of respondents have similar views about their relationship with their nation.

Table 5. A sense of identification with various groups and social environments, in percent

Source: Author's own study.

To better understand student perception of patriotism – particularly in the light of the aforementioned theoretical concepts – it is worth asking how it is expressed in the activity of specific individuals (Table 6). Previous intuitions are also confirmed in this context: students more often associate patriotism with activities that do not require a strong cognitive and behavioural involvement. Nevertheless, the data collected can be used to describe a ‘good patriot’ according to the criteria given the highest priority by students. Thus, the image of a good patriot includes:

a) most often (mean >4.00, dominant = 5): knowledge of the national anthem, readiness to defend the country, knowledge of history, hanging flags during national holidays, attachment to national symbols, using correct Polish language, voting in elections;

b) less often (mean <4.00, dominant = 4): high personal culture in dealing with foreigners, supporting Polish national teams, undertaking local community activities and observing the law.

Participation in services during national holidays as a manifestation of patriotism evokes controversy among respondents (low mean, high dominant) while paying taxes is very rarely an expression of a patriotic attitude in the opinions of students (dominant = 1).

Table 6. Patriotism in everyday life

Source: Author's own study.

These data shed light on the problem of student understanding of the concept of patriotism. To make this picture complete, attention should be paid to the issue of students' patriotic self-identification. Do they and, if so, to what extent do they consider themselves patriots? Students are very willing to define themselves as patriots, although – as in many other cases – these are not very definite opinions. Generally, patriotic self-identification is declared by over three-quarters (76.9%) of respondents, and 11.8% of them do not see the ‘signs’ of patriotism in themselves.

It has already been mentioned that not many students associate patriotism with making a long-lasting effort. Their understanding of patriotism is more affective, symbolic, and takes the form of unverifiable assurances (e.g. the declared readiness to defend the country in case of war). Constructive forms of patriotism (identified with civic activity, local community activities) are less rooted in student consciousness. Since patriotism is more often referred to in the emotional and symbolic spheres, how does it – if at all – determine civic activity (e.g. local community activity, charity, volunteering or activity in student organizations)? A closer look at these dependencies should help to characterize the constructive potential of the student understanding of patriotism more accurately.

Patriotism as a determinant of student activity

The primary goal of the study is to find out if the way Polish students understand patriotism has practical implications, that is, whether or not patriotism can be considered an important motivating factor for activity in voluntary organizations. This approach seems to be useful in the context of the observation made by Kahne and Middaugh (Reference Kahne and Middaugh2006, 603–604). They argue that ‘many students fail to appreciate the importance of civic participation’, and ‘while both blind and constructive patriots love their country, neither type is necessarily actively engaged in civic or political life’. Therefore, instead of talking about blind or constructive patriots, we should rather distinguish between passive or active patriots. Obviously, the research results do not show the nature of the involvement of specific individuals: whether it is functional or dysfunctional, whether it serves a community or individual goals, or whether it is socially constructive or, rather, destructive. Obviously, this issue cannot be ignored and this paper is meant to provide a relevant foundation for this type of question. However, in the case of younger generations, particularly those in post-communist countries, we should assume that civic activity is a positive and desirable phenomenon. It must be remembered that young people – regardless of the geographical context – constitute the most depoliticized age group of citizens (Plutzer, Reference Plutzer2002; Furlong and Cartmel, Reference Furlong and Cartmel2007; Mitev and Kovacheva, Reference Mitev and Kovacheva2014, 136–152). Changes occurring in postmodern society have permanently reorganized human habits and ways of being in various fields of activity, including politics and public affairs. Postmodern attitudes are taking the form of indifference and apathy in politics, which is why they ‘are undermining the effectiveness of democratic institutions and weakening the traditional conceptions of citizenship’ (Dermody and Hanmer-Lloyd, Reference Dermody, Hanmer-Lloyd, Kane and Poweller2008, 155). In his Letters to a Young Contrarian, Hitchens (Reference Hitchens2001, 41) writes that citizens are tempted to remain passive and submissive. Such attitudes undermine civic engagement and may consequently lead to increased distrust towards politics, and a shift towards the so-called ‘private citizenship’ and the lack of commitment to community life (Terrén Reference Terrén2002, 174,). Eduardo Terrén believes, however, that there is always a chance to overcome these dysfunctional attitudes through appropriate ‘democratic education’. This ‘hope’ primarily concerns young people. As he claims, education is one of the most important areas enabling the renewal or establishment of ‘modern political culture’ (Terrén, Reference Terrén2002, 161) and the ‘programming’ of constructive citizenship (see also an interesting study on social functions of education: Lopes et al., Reference Lopes, Benton and Cleaver2009). In this context, the question posed by Westheimer and Kahne (Reference Westheimer and Kahne2004, 239): ‘What kind of citizen do we need to support an effective democratic society?’ seems to be important. The goal of education and youth policy should be to support the development of citizens who can ‘actively participate and take leadership positions within established systems and community structures’ (participatory citizens) or ‘question, debate, and change established systems and structures that reproduce patterns of injustice over time’ (justice-oriented citizens) (Westheimer and Kahne, Reference Westheimer and Kahne2004, 240). These citizens will become ‘increasingly resistant to authoritarian government, more interested in political life, and more likely to play an active role in politics’ (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart and Norris1999, 236). A number of studies show that the level of social capital determines political participation and even the quality of democracy. However, in this case, this is a self-propelled mechanism. Many researchers emphasize the functional role of participation in shaping pro-social, civic, and democratic habits. Activity generates activity, and young people learn what ‘good citizenship’ is in practice through various forms of civic engagement (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Lister, Middleton and Cox2005; Banaji, Reference Banaji2008). Participation consolidates democratic habits in young people, such as tolerance, understanding, self-expression, and cooperation (O'Donoghue et al., Reference O'Donoghue, Kirshner and McLaughlin2002, 18–19). Quintelier (Reference Quintelier2008) claims that voluntary activity in social engagement networks has at least three positive effects for a young generation. Firstly, young people learn to make political decisions. Secondly, they develop important attitudes (e.g. a sense of effectiveness, trust). Thirdly, they acquire useful skills (e.g. looking for a compromise, expressing one's own opinions) (McFarland and Thomas, Reference McFarland and Thomas2006, 402; Geijsel et al., Reference Geijsel, Ledoux, Reumerman and ten Dam2012).

Measures

Initially, seven potential predictors have been selected for the analysis, which collectively constitute an expression of a patriotic disposition (Table 7).

Table 7. Independent variables used to verify hypothesis

Source: Author's own study.

The rating scales used for variables pride_general, associations, self_identification, love_for_country and pride_flag allow the grouping of respondents into three categories: ‘declared patriots’, ‘moderate patriots’, and ‘non-patriots’ (relatively ‘indifferent patriots’). In turn, the variables pride_specific and patriotic_attitude required a reduction of multi-dimensionality due to the large number of items applied. To this end, principal components analysis (PCA) with oblique rotation was carried out. A scree plot was used to identify two factors that explained a total of 63.5% of the variance of results. Table 8 shows factor loads after rotation. Items correlating highly with individual components indicate that the first factor presents the level of pride in being Polish in situations of sporting successes of Polish representatives (pride_specific_sport), while the second factor reflects pride in important political events (pride_specific_politics).

Table 8. Summary of principal components analysis for pride_specific

Source: Author's own study.

As all variables falling within the scope of the question about the feeling of pride in certain situations were measured using the same five-level scale, the indicators were calculated by averaging items falling within the scope of individual factors. Item ‘i_3’ was excluded from the calculation because it correlated with both factors in a similar way. Thanks to the adoption of the averaging method, new indicators were characterized by the same range of acceptable results as the original scale of items <1; 5>. The table also presents internal consistency measures (Cronbach's Alpha) for both scales. In the case of the variable pride_specific_politics, the alpha coefficient is relatively low but should be accepted, considering the scale only consists of two items. In conclusion, both scales of pride in being Polish were characterized by acceptable reliability.

A similar analysis was carried out to reduce dimensionality for the 13 items falling within the scope of the question about activities that express a patriotic attitude (patriotic_attitude). As the result of the PCA with oblique rotation, it was decided to distinguish two factors that explained a total of 47% of the variance of results. Items correlating highly with individual components indicate that the first factor can be identified with the emotional component of the patriotic attitude (emotional_patriotic_attitude), while the second factor identifies with the cognitive component (cognitive_patriotic_attitude). Table 9 shows factor loads after rotation.

Table 9. Summary of principal components analysis for patriotic_attitude

Source: Author's own study.

The indicators were calculated by averaging items falling within the scope of individual factors. Item ‘i_8’ was excluded from the calculation because it correlated with both factors in a similar way. The table also presents internal consistency measures (Cronbach's alfa), which equalled 0.75 for both scales. In conclusion, both scales of the patriotic attitude were characterized by satisfactory reliability.

Study

Firstly, the relationship between perception of patriotism and readiness to undertake activities for local communities (civic activity) was tested. The sample consisted of a total of N = 793 students, of which n = 676 were randomly assigned to the training sample, and n = 117 to the testing sample. Parameters of the logit model were estimated based on the training sample, while the testing sample was used for additional model diagnostics. The persons involved accounted for 42% of the total number of respondents in the training and testing samples. The regression model was constructed using the backward stepwise method. The initial model contained only control variables: gender, political identification, cycle of study, and place of origin. Of the input set of nine predictors (pride_general, pride_specific_sport, pride_specific_politics, associations, self_identification, emotional_patriotic_attitude, cognitive_patriotic_attitude, love_for_country and pride_flag), the final model included three statistically significant variables: pride_flag, cognitive_patriotic_attitude and self_identification.Footnote 11 The final model was statistically significant: χ2 (df = 9) = 47.58; P < 0.001; R 2 = 0.07 (Hosmer-Lemeshow) and 0.09 (Nagelkerke). The model parameters are presented in Table 10.

Table 10. Parameters of the logit model of civic activity

Source: Author's own study.

The results indicate that all predictors were positive and had similar strength. Feeling proud at the sight of a Polish flag in a public place (pride_flag), the higher intensity of cognitive component of patriotism (cognitive_patriotic_attitude), and considering oneself a patriot (self_identification) were correlated with more frequent involvement in local community activities. The individual odds ratio (OR) was used to interpret the parameters in the logistic regression. This ratio indicates that all model elements explain the civic activity level in a similar way. Since the predictors pride_flag and self_identification are variables with more than two categories, it is more difficult to interpret the results using OR. The individual OR for pride_flag (OR = 1.36) and self_identification (OR = 1.40) means that the odds that students with a strong sense of patriotism in this area will undertake activity are 36% and 40% higher compared to moderately patriotic students. Similarly, the odds that moderately patriotic students will be active are 36% and 40% higher compared to non-patriotic students. In turn, the predictor cognitive_patriotic_attitude is a quantitative variable with the range of 1–5 and so the individual OR (OR = 1.34) informs that the odds of activity increase by 34% if the result on the ‘scale of patriotic emotions’ changes, for example, from 3 to 4.

The quality of the model fit was also evaluated using a classification matrix – separately for the training and testing samples (Table 11). The probability limit was assumed at 50%, meaning that the model classified individuals into active groups when the predicted probability of affiliation was more than 50%.

Table 11. Classification matrix for civic activity

Source: Author's own study.

The model correctly classified a total of 61% cases in the training sample and 56% in the testing sample. As the majority of respondents were inactive persons, the model was less effective in classifying active students.

Discussion and conclusions

The aim of the analysis was to determine to what extent the multi-dimensional patriotic disposition (or a set of views related to patriotism described by the nine variables) is constructive, that is, whether or not its individual elements constitute significant motivation for social activity. It was initially assumed that people who strongly identify themselves as patriots are more likely to engage in the activities in local communities. Based on the results of the analysis, it can be concluded that the general hypothesis has been confirmed. However, it should be emphasized that during the modelling process, only three out of nine independent variables describing patriotism (pride_flag, cognitive_patriotic_attitude, self_identification) were significantly affected. This observation leads to the conclusion that the concept of patriotism is a poor predictor of activity. It boils down to verbal declarations and experiencing certain emotional states, but its constructive potential is limited. Perhaps this is a derivative of the way in which this category is used in public and political debate in Poland. Namely, patriotism is more often associated with attachment to Polishness (identification) and love for the homeland. The debate less often concerns the practical implications and obligations of patriotism which should motivate people to undertake specific actions, for example, activities for the benefit of local communities or the environment in which people work or learn. Polish disputes over patriotism are part of the dominant political conflict that concerns identity rather than interests (Ost, Reference Ost2006, 186).

This is a well-known problem in the study of youth patriotism called ‘passive patriots’ (Kahne and Middaugh, Reference Kahne and Middaugh2006). In this context, the previously mentioned distinction between ‘blind’ and ‘constructive’ patriotisms may seem less useful. Regardless of what set of patriotic views is shared by the respondents, it is observed that both ‘blind’ and ‘constructive’ patriots – though they love their country – are not interested in activism in either a political or a civil sense. Therefore, instead of talking about blind and constructive patriotisms, we should rather distinguish between its passive variant (associated only with the cognitive-affective aspects of attachment to the country) and active variant (undertaking specific actions for the group and even sacrificing life in special cases) (Bar-Tal, Reference Bar-Tal1993, 49). This also corresponds to the distinction between two types of national involvement (Schatz and Lavine, Reference Schatz and Lavine2007). Its authors argue that attitudes towards the nation can be classified according to motivations (causes) and also cognitive, emotional, and behavioural consequences. In this sense, one can distinguish between (1) symbolic national involvement, focused on symbols and rituals, which ‘is rooted in intrapsychic needs related to the self-concept’ and (2) instrumental national involvement, which ‘is rooted in a utilitarian concern for the functionality of national institutions’. In the first case, people identify with the nation because it provides a positive identity and contributes to higher self-esteem. They are convinced of the high value of their nation and are more willing to defend the positive image of their own group; they also value the cohesion and homogeneity of the group. They are also characterized by a higher level of national pride. Their public activity, however, is most often limited to ritual and ceremonial behaviour (apart from periods of crisis, e.g. political crisis). Therefore, their cognitive and behavioural involvement is weaker (they know less and participate less frequently) than that of people with the instrumental attitude. The latter, in turn, are more interested in acquiring knowledge and undertaking actions aimed at positive changes because their motivation is to care for the effectiveness of social, political or economic institutions that should provide instrumental benefits to its citizens. Patriotic dispositions of Polish students correspond rather to the symbolic model of national involvement. This is clearly seen in the example of two scales of the patriotic attitude (variable patriotic_attitude): in the full model, the cognitive component was statistically significant (P = 0.026 and 0.017 in the final model) in contrast to the emotional component (P = 0.852).

The regression analysis shows that patriotic self-identification is the most important factor in stimulating civic activity. In practice, it boils down to a casual expression of identity, which is not necessarily an element of a clear and stable patriotic attitude. However, these correlations and the importance of self-identification show that the question of what it means to ‘be a patriot’ becomes important from the point of view of the quality of democracy. Does it only mean to feel, experience, and symbolically manifest patriotism, or also to act, get involved, participate, and perhaps even sacrifice oneself – one's own free time, resources, and cultural capital? This question is also a challenge for many democratic institutions that constantly affect the social awareness of young adults, shape their political culture and social capital, play an important role in the process of political socialization (Marzęcki, Reference Marzęcki2013) and thus implement specific civic education that ‘should help young people acquire and learn to use the skills, knowledge, and attitudes that will prepare them to be competent and responsible citizens throughout their lives’ (Carnegie, 2018). There is no doubt that patriotic disposition supports the readiness to take up civic activity. However, the results of the analysis lead to the conclusion that, although the odds of activity are greater in people who experience strong emotions in relation to their own country or national symbols, they do not necessarily understand patriotism as socially functional activity. The resolution of this dilemma certainly requires further research in this area.

The results obtained should lead to practical conclusions that may be useful for various social institutions which are interested in releasing the positive energy of citizens and orienting them to functional goals, that is, the education system (civic education programmes), as well as for political institutions that design and implement elements of the so-called youth policy. In sociological, political-science, pedagogical, or even philosophical literature, the arguments concerning the purposefulness of so-called ‘patriotic education’ have been constantly presented (Nussbaum, Reference Nussbaum and Cohen1996; Ben-Porath, Reference Ben-Porath2006; Miller, Reference Miller2007; Westheimer, Reference Westheimer2007; Zembylas, Reference Zembylas2014). Some researchers emphasize that teaching patriotism is difficult, and they also pay attention to the aspect discussed in this paper. Kahne and Middaugh (Reference Kahne and Middaugh2006, 607) write that ‘citizens do not instinctively or organically develop understandings of patriotism that align with democratic ideals’. Hand (Reference Hand2011, 331) argues that promoting patriotism in schools is a form of emotional education that may be either rational or non-rational. In the first case, we are dealing with ‘the attempt to offer pupils good reasons for moderating or changing their emotional responses, to help them see why the reasons are good and to equip them with techniques for bringing about such changes as they choose to make on the basis of those reasons’. In turn, non-rational emotional education means ‘the attempt to deploy methods of psychological manipulation to alter pupils’ emotional responses directly, without reference to their capacities for reason assessment and rational choice’. How to promote patriotism in schools? Hand (Reference Hand2011, 345) suggests teaching it as a controversial issue (‘acknowledge and explore various possible answers to a question without endorsing any of them’). Other authors state that ‘rather than ‘teaching’ students to love their country, teachers need to help students build an explicit connection between their ‘love of country’ and democratic ideals’ that are rational and include the role of informed analysis and critique, the importance of action, and pay attention to the danger of blind loyalty to the state (Kahne and Middaugh, Reference Kahne and Middaugh2006, 606).

Sensible patriotic education can be an institutional goal for the future. In practice, it is difficult to effectively ‘design or predict the outcome of the transformation, but no change is possible without any future oriented design’ (Federowicz, Reference Federowicz and Dobry2000, 91). Therefore, it seems legitimate to draw a normative conclusion that it is necessary to conduct a broad public, political, and educational debate to fill the notion of patriotism with new constructive content. This will allow young people to feel patriotic in an emotional and symbolic sense and also to identify being a patriot with being a ‘good citizen’ (Levinson, Reference Levinson, Sherrod, Torney-Purta and Flanagan2010). In the social awareness of students, there is a deficit of constructive references to the concept of patriotism (see the concept of ‘consuming patriotism’, Nowicka-Franczak Reference Nowicka-Franczak2018), although the category of patriotism plays a significant role in their life in the process of shaping identity and as a criterion for assessing political and social phenomena. We should, therefore, try to use this potential more constructively in order to multiply the resources that make up the social capital of the young generation.

Author ORCIDs

Radosław Marzęcki 0000-0002-2915-8878.

Acknowledgments

I thank Siyka Kovacheva (Plovdiv University, Bulgaria), Tom Junes (Belgium), Conor O'Dwyer (University of Florida, USA), and Grzegorz Foryś (Pedagogical University of Cracow, Poland), whose opinions, comments and suggestions were of inestimable value for my study.

Funding

The research has been funded by the National Science Centre, Poland (grant no. 2016/23/D/HS5/00902).

Data

The replication dataset is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp.