Introduction

Political trust is an important indicator of political legitimacy. It contributes to its reinforcement, but ‘it should not be confused with legitimacy’ (Linz, quoted in Dogan, Reference Dogan1994: 305; Levi and Stoker, Reference Levi and Stoker2000). It reflects the stability of political systems (Easton, Reference Easton1965), and it represents an essential component of the civic culture (Almond and Verba, Reference Almond and Verba1963) and a reservoir of support when regime performance declines (Turper and Aarts, Reference Turper and Aarts2017).

The decline in political trust among advanced democracies is not new (Citrin Reference Citrin1974; Miller Reference Miller1974). It has been falling in consolidated democracies since the late 1960s (Dalton and Wattenberg, Reference Dalton and Wattenberg2000), while among areas where democracy is still in its infancy, its trend shows a clear contraction (Bratton and Gyimah-Boadi, Reference Bratton and Gyimah-Boadi2015). Citizens have become more inclined to express their dissatisfaction with the political system, tending to be critical of the core institutions of representative democracy (Norris, Reference Norris1999), and are responding more rationally and instrumentally to the institutional context (Norris, Reference Norris2011). In a word, public trust has eroded over the past generation (Dalton, Reference Dalton2004), coinciding with a diffuse growth in economic insecurity among the advanced economies (Wroe, Reference Wroe2016).

Since political trust ‘is not necessarily based on the actual performance of individual institutions, but rather reflects a kind of a general assessment of the prevailing political culture within a country’ (Hooghe and Zmerli, Reference Hooghe and Zmerli2011: 4), the scenario drawn above should be even more concerning if political trust is analysed among new democracies. This is because if growing levels of trust contribute to facilitating democratic consolidation, an opposite trend could produce a democratic breakdown and a return to an authoritarian political system (see Wong et al., Reference Wong, Wan and Hsiao2011). This is the case in Latin American countries, where the alternation of democratic and authoritarian regimes (Malloy, Reference Malloy1987) has made states increasingly fragile, as they demonstrate the lowest levels of political trust compared to other regions of the world (Segovia Arancibia, Reference Segovia Arancibia2008).

Since the negative economic performance associated with periods of economic crisis can negatively affect citizens’ support for key elements of democracy (Córdova and Seligson, Reference Córdova and Seligson2009), in this work, we estimate the effect of both citizens’ (personal and national) economic perceptions and objective economic measures on their trust in political institutions. This article contributes to the scholarly debate on the causes of political trust by offering a more specific focus on the role of both personal and national perceptions of the economy, as well as on national economic indicators. It is known that over the last decade, the economic performance of Latin American countries has been fluctuating. The global economic crisis has also affected these countries. According to some economic experts, in the 2016 Latin America and the Caribbean suffered its worst economic scenario since 2009 (see FocusEconomics, 2016). Thus, what effects can the economy have on political support, and specifically, on political trust?

To answer this question, we first turned to economic voting theory. As we know, the perception of the economy and the real economy often go hand in hand (Lewis-Beck, Reference Lewis-Beck2006), affecting support for the incumbent government. Although the ‘government is probably perceived more often as the performing institutions’ (Van der Meer and Dekker, Reference Van der Meer and Dekker2011: 111), the political relevance of the other political institutions is not secondary, and the effect of the economy on society is not insignificant. Since a vote for the incumbent government can also be seen as a trustee’s choice (see Hetherington, Reference Hetherington1999), we could expect that the economy also significantly affect the political trust towards other institutions. Regarding the different levels of political trust, Hooghe (Reference Hooghe2011) underlined that citizens usually tend to focus on the most visible actor or institution in daily politics and generalize this attitude to other institutions. Thus, citizens’ evaluation about government or parties could be attributed to other political institutions as well, and vice versa. Since, as Bovens and Wille (Reference Bovens and Wille2008) suggested, economic performance is the most likely explanation for political trust, in this paper, we verify whether the economy orients the assessment of citizens about political institutions. Specifically, when the economy performs well, and citizens’ perception of the economy is positive, they should support political institutions.

This work differs fundamentally from the others that have analysed democracy in Latin America, such as Both and Seligson (Reference Both and Seligson2009), in three specific aspects. First of all, an appreciable number of countries (17) are analysed from a longitudinal perspective.Footnote 1 The use of a diachronic view as applied to the study of the relationship between the economy and democracy is particularly appropriate because the two measurements are affected by significant changes over time. The longitudinal analysis then enables us to trace the dynamics and estimate the effects that can be distinguished by the temporal parameter. To our knowledge, very few studies have focussed on the relationship between the economy and political trust using a longitudinal perspective (see Seligson, Reference Seligson2008; Seligson et al., Reference Seligson, Smith and Zechmeister2012; Torcal and Bargsted, Reference Torcal and Bargsted2015; Castillo et al., Reference Castillo, Bargsted and Somma2017). Second, this study analyses information collected on both the individual and aggregate levels. To our knowledge, no study that analyses the relationship between the economy and democracy among the countries of Latin America has adopted both types of information. The adoption of multilevel analysis techniques allows a consideration of the existence of hierarchically structured information and avoids the methodological problems related to the analysis of the relationships between units and aggregates. The only exception is the cross-sectional study realized by Ergun and colleagues (Reference Ergun, Rivas and Rossi2016), which analyses 18 Latin American countries using information gathered by the Latinobarómetro Survey in 2010. Third, this study analyses the trend of political trust for a rather broad period during which, as previously mentioned, the American and European economic shocks conditioned both the public opinion and the choices of the governments of Latin America. In other words, in the wake of the work realized by Both and Seligson (Reference Both and Seligson2009), this study will help shed light on political support in a context in which democracy struggles to consolidate.

To do this, we adopt information gathered by the Latin American Barometer between 1996 and 2013,Footnote 2 as well as World Bank data, and through a multilevel model, we estimate the effect of the economy (perceived and real) on trust in political institutions.Footnote 3

This paper is structured in five parts. The first part analyses the main studies on political support in Latin America. In the second part, looking at the link between economics and democracy, we set out the working hypothesis, while in the third part, we discuss about political trust among Latin American countries. In the fourth, we report on the empirical findings, while in the fifth, we draw our conclusions. Estimating the combined effect produced by the perceptions that citizens have of the economy (personal or national) and the real economy on trust in political institutions, this work reveals that when citizens evaluate the economy from a sociotropic view, political trust increases.

Political support in Latin America: theoretical and empirical aspects

Institutional trust is vital for democracy (Berg and Hjerm, Reference Berg and Hjerm2010). In fact, as underlined by Marien and Hooghe (Reference Marien and Hooghe2011), trust reduces the costs related to the monitoring of the political process, allows citizens to delegate decision-making, and reduces the complexity of ruling, making it one of the most vital assets of democracies.

From a theoretical point of view, political trust may be defined as ‘a basic evaluative orientation toward the government founded on how well the government is operating according to people’s normative expectations’ (Hetherington, Reference Hetherington1998: 791). Citizens who have trust in political institutions tend to support the political choice of the elite because the latter are working for the collective well-being. Following the institutional explanations of political trust, trust is an extension of generalized trust, assimilated through the process of socialization and later transferred to the political system and its institutions. Since trust in institutions is ‘rationally based’ (Mishler and Rose, Reference Mishler and Rose2001: 31), the quality and performance of the institutions (Rothstein, Reference Rothstein2008, Reference Rothstein2011) are the elements through which the citizens assess their institutions. In this view, high political trust implies that institutions perform well, while low levels of political trust relate to performance failure (see Listhaug and Ringdal, Reference Listhaug and Ringdal2008; Choi and Woo, Reference Choi and Woo2016).

From an empirical point of view, political trust is a multifaceted concept. Although the variety of normative expectations that characterize democratic institutions have prompted some scholars to believe that the basis of trust in democratic institutions seems to be particularly ambiguous (Grönlund and Setälä, Reference Grönlund and Setälä2007: 402), recent studies have analysed it in theoretical and empirical terms. As Denters and colleagues (Reference Denters, Gabriel and Torcal2007) have underlined, in the wake of Gabriel et al. (Reference Gabriel, Kunz, Roßteutscher and van Deth2002), political trust can be conceptualized as a political orientation towards political actors as well as towards political institutions. At the same time, it is possible to distinguish among political institutions, differentiating those that characterize contemporary democracies (the Parliament, the National government), from representatives of a central decision-making agency (political party, politicians), and from institutions that represent the constitutional state (the Police and the Courts). Other scholars prefer to distinguish political institutions in terms of those that are partisan and those that are order/neutral (Rothstein and Stolle, Reference Rothstein and Stolle2008), while other researchers add the international classification to the aforementioned two (André, Reference André2014). However, there are studies in which political trust is represented as a one-dimensional concept (Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, van Heerde and Tucker2010; Hooghe, Reference Hooghe2011) – different levels of trust that citizens have in political institutions are synthesized in an index of political trust using factorial techniques or additive-type aggregation procedures (see Krauss et al., Reference Krauss, Nemoto, Pekkanen and Tanaka2016; Kroknes et al., Reference Kroknes, Jakobsen and Grønning2016; Pitlik and Rode, Reference Pitlik and Rode2016).

The studies that have analysed democratic support, even in light of the current economic crisis (see Armingeon and Guthmann, Reference Armingeon and Guthmann2014), outline a concerning scenario. At the end of the 20th century, the major industrialized democracies appeared to be in crisis (Kaase and Newton, Reference Kaase and Newton1995) and a sense of malaise characterized democratic citizens (Norris, Reference Norris1999); in the new millennium, the scenario does not seem to have changed. From one side of the globe to the other, an erosion of democratic support is evident (Dalton, Reference Dalton2004), and a sense of scepticism is increasing in the public, as well as a moving away from the political arena (Memoli, Reference Memoli2011; Karp and Milazzo, Reference Karp and Milazzo2015; Ezrow and Xezonakis, Reference Ezrow and Xezonakis2016). At the same time, the younger generations appear increasingly inclined not to promote democratic principles and practices, and do not seem to oppose an alternative that is antithetical to democracy (Denmark et al., Reference Denmark, Donovan and Niemi2014).

This trend appears to be even more evident in the countries of Latin America, where even at the beginning of the new millennium, the initial euphoria evoked by democratic change had passed, and in some countries, such as Brazil, Paraguay, Venezuela, and Columbia, democracy appeared to be in dire straits (Lagos Cruz-Coke, Reference Lagos Cruz-Coke2001: 137–138). Many scholars have concluded that in these countries, mass support for democracy is not particularly consistent (Seligson, Reference Seligson2008), and support for democratic performance does not seem to be affected by the economic crisis (Graham and Sukhtankar, Reference Graham and Sukhtankar2004). Although the progress recorded in the process of the assimilation of democratic values and principles (Diniz, Reference Diniz2011) confirms a clear optimism in public opinion, over time, there has been a contraction in the hope for change on the part of public opinion. As pointed out by Smith (Reference Smith2005), the cyclic economic crises, the economic adjustments of the neoliberal matrix, and the issues related to the political system, above all, in terms of cronyism and corruption, have decreased citizens’ expectations and have negatively affected democracy. Citizens are often disappointed with democracy and less inclined to support it (Sarsfield and Echegaray, Reference Sarsfield and Echegaray2006). In addition, episodes of political corruption have made political institutions and political leaders less credible and have lowered the level of support for democracy (Ergun et al., Reference Ergun, Rivas and Rossi2016). Citizens appear to be characterized by more aggressive political participation and less tolerance of abuses of power (Morris and Blake, Reference Morris and Blake2010); these factors, along with the consolidation of abuses from the security forces, have undermined and delegitimized the political system (Cruz, Reference Cruz2015). Observing the democratic process in Latin American from a longitudinal perspective, a clear weakness in the political and institutional conditions emerges, as well as the absence of effective strategies to strengthen them and ensure a stable democratic regime and its consolidation in the long run.

Economy and trust in political institutions

The economy is considered by many scholars as the driving force of democracy (see Lipset, Reference Lipset1959) and its consolidation (Diamond, Reference Diamond1999). According to Huntington (Reference Huntington1991), positive (negative) economic cycles increase (decrease) the chances of survival of democratic regimes, as well as changes in democratic support from the citizens (Dalton, Reference Dalton2004). The numerous theories that adopt a systemic perspective link democracy with the economy. However, not all scholars seem to agree on the causal direction binding them, feeding conflicting visions. Indeed, some scholars believe democracy and its duration are the main factors which contribute to economic growth (Carbone et al., Reference Carbone, Memoli and Quartapelle2016). Others show that economic growth fuels the democratic transition (Boix and Stokes, Reference Boix and Stokes2003) and subsequent democratic maintenance (Epstein et al., Reference Epstein, Bates, Goldstone, Kristensen and O’Halloran2006). This is found in both among the established democracies (Bellucci and Memoli, Reference Bellucci and Memoli2012) and in countries where democracy is still nascent (Quaranta and Memoli, Reference Quaranta and Memoli2016). Over the years, although the number of studies has grown, the empirical results reveal contradictory trends and a weak effect of the economy on democracy (Dalton, Reference Dalton2004).

Since the 1990s, there has been an increase in studies that have focussed on the links between the economy and democratic support (Dalton, Reference Dalton2004). The ‘democratic malaise’ highlighted by several comparative studies (see Norris, Reference Norris1999) summarizes the fear of delegitimization of the political system linked to economic trends, whose oscillations inevitably influence voters’ political decisions (Anderson, Reference Anderson1995), as well as their judgements on the government (Alesina and Wacziarg, Reference Alesina and Wacziarg2000) and on democratic support by citizens (Dalton, Reference Dalton2004).

The connection that combines the economy and the political system is well evidenced in terms of accountability and responsiveness (on this point, see Tavits, Reference Tavits2007), even within the debate on economic voting. In fact, citizens tend to renew their trust in the political institutions (in this case, the incumbent government) if its performance is positive; if it is not, the voters will move their political preferences elsewhere (see Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier, Reference Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier2000: 183).Footnote 4 With the economic crisis, citizens have voiced their dissatisfaction, protesting against governments to prompt them to address and resolve the crisis (van Gent et al., Reference van Gent, Mamadouh and van der Wusten2013). This aspect is not secondary, because the economic insecurity that could be generated from the negative institutional performance could affect the sense of trust in institutions (Hacker et al., Reference Hacker, Rehm and Schlesinger2013) and nourish nationalistic sentiments (Kage, Reference Kage2013).

The perception of any phenomenon by a citizen is a fundamental element in human decision-making (see Moreira, Reference Moreira2015). Considering that both the perceived and real economy are determinants for democratic support (see McAllister, Reference McAllister1999; Karp et al., Reference Karp, Banducci and Bowler2003; Neundorf, Reference Neundorf2010; Kotzian, Reference Kotzian2011; Quaranta and Martini, Reference Quaranta and Martini2016), it is possible to assume a conjoint effect of the economy (personal and national) on the levels of political trust expressed by citizens. This interaction could be considered using both measures of economic perception (personal and national) and measures that combine these latter with different measures of the real economy.

Following the economic voting theory, it has been shown that voters are influenced by their subjective views of the national economy, even though they are not much swayed by their personal economic standing (Kinder et al., Reference Kinder, Adams and Gronke1989). Thus, voters tend to respond to their beliefs about the state of the overall economy rather than to their personal pocketbooks. Since citizens seem capable of evaluating macroeconomic outcomes (Duch and Stevenson, Reference Duch and Stevenson2011), and considering that the evaluation of government is realized adopting a sociotropic view rather than an egocentric view, it is possible to assume that citizens’ political trust could also be affected by a sociotropic view of the economy. Since egocentric and sociotropic economic assessments are not independent, we consider it appropriate to look at the economy in terms of an egocentric view as well. That choice is supported by the fact that the studies of economic voting realized in Latin American countries show that both egocentric and sociotropic perceptions affect voting for the incumbent government (see Weyland, Reference Weyland2003; Singer and Carlin, Reference Singer and Carlin2013). Therefore, it is possible to hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1: In countries where citizens positively perceive the personal and national economy, the level of political trust grows.

Hypothesis 2: In countries where citizens positively perceive their personal economic well-being (egocentric view), the level of political trust grows as GDP per capita purchasing power parity (PPP) (t−1) increases.

Hypothesis 3: In countries where citizens positively perceive the national economic well-being (sociotropic view), the level of political trust grows as GDP (t−1) increases.

Political trust in Latin American countries

In the 1960s, the overload of the Latin American governments generated by the growing demand from citizens affected the economic development and state management, which was already fragile, leading to a return to authoritarian regimes (O’Donnell et al., Reference O’Donnell, Schmitter and Whitehead1986), as in the cases of Peru, Brazil, Bolivia, and Argentina. Through the 1980s, the democracy among the countries of Latin America has undoubtedly strengthened: first in Ecuador (1979) and followed by other countries,Footnote 5 the transition from authoritarianism produced rapid change on the continent. In the early 1980s, the external debt crisis did not lead to changes in economic institutions, and liberal reforms were implemented only at the end of the decade by rebalancing the relationship between the state and the market. In the 1990s, numerous countries in Latin America could be considered in transition to democracy because, after a long period of dictatorship, most political regimes were transforming into liberal or electoral democracies. However, the optimism of political analysts that was founded on greater democratic stability and a better socio-economic balance did not translate into a real democratic consolidation. Economic and technological dependence, along with socio-economic inequality and poverty, were the main factors that influenced both the problematic evolution of democratic regimes (see Offe, Reference Offe2009) and the fragility of the states in finding a balance between economic performance and social rights.

Following Easton (Reference Easton1965) and other scholars, using information gathered from the Latinbaròmetro, it is possible to trace the support for the political institutions from a longitudinal point of view.Footnote 6 To do this, we take into account the citizens’ trust in the following political institutions: the National Congress/Parliament, the Judiciary System, the Police, and Political Parties.Footnote 7

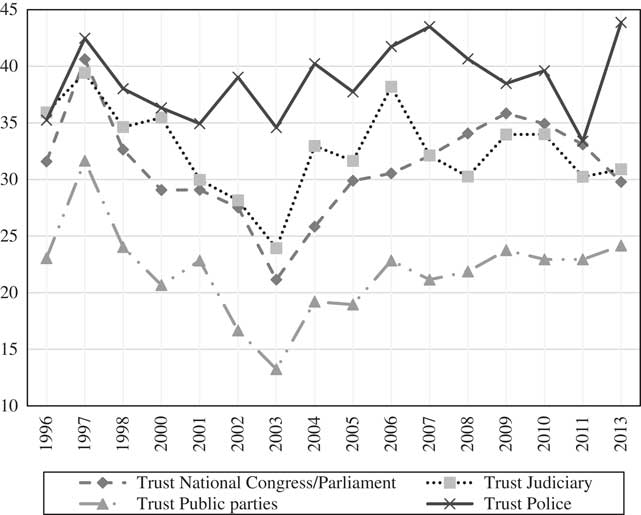

Figure 1 shows the percentage values of those who have expressed that they have much or sufficient trust in political institutions. From 1996 to 2013, the trend of trust has been swinging, and it has been significantly affected by the past years. In the early part of the 1990s, political trust continued to be conditioned by a shift between authoritarianism and democracy (Bargsted et al., Reference Bargsted, Castillo and Somma2017), making trust in public institutions uncertain. In the 1990s, both the contraction of poverty and inequality, as well as annual GDP growth (see Cano, Reference Cano1999), fuelled the idea of a clear economic improvement. The effects on citizens’ political trust are evident at least until 1997, when the globalized economy began to decline after the Asian, and later, the Russian, Brazilian, and Argentine crises. In a pricing/punishment logic, the trust that citizens placed in their political institutions, and especially political parties, declined significantly. From 1997 to 2003, although trust had never been particularly high, it declined by 18.2 percentage points. Only trust in the Police grew.

Figure 1 Trust in political institutions.

Since 2004, the sudden growth of Latin American economies has generated more public trust among citizens in the institutions. Economic growth has contributed to reducing the level of indigence (Economic Commission for Latin American and Carribean, 2012), driving among the citizens an increased propensity to trust in their political institutions. This trend characterizes all political institutions, including Political Parties, which remains at a lower level of trust despite the recordation of a growth in trust by 10 percentage points.

Using different information about trust in political institutions (National Congress/Parliament, Judiciary System, Police, and Political Parties) and applying a factor analysis,Footnote 8 we obtained factor scores as a synthesis of the analysed information. Through this index, it is possible to differentiate the countries of Latin America from the perspective of time (1996–2013; Table 1). Our results reveal that all four indicators are interconnected to one factorial dimension obtained by the method maximum likelihood factor and have values greater than or equal to 0.615. This value confirms that attitudes towards political institutions tend to be generalized to different levels of measurement (Bartlett’s test of sphericity = 0.000; Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin = 0.774).Footnote 9 All items positively contribute to the reliability of the factor (Cronbach’s α = 0.779).Footnote 10

Table 1 Factor analysis

Source: Latinobarómetro (1996–2013).

The substantial drop in political trust over time reveals a certain dissatisfaction that characterizes some countries (Table 2). This is especially evident in Honduras, Guatemala, Paraguay, Nicaragua, and Nicaragua, where democracy has slowly tried to take off, but also in Chile, where democracy is consolidated. On the other hand, in Venezuela, political trust had a positive peak with the coming to power of Chávez (1999–2013), and his redistributive social policies contributed to fostering greater trust among the citizens in the institutions until 2013, when his successor, Maduro, replaced the late President. The same trend is noted in Ecuador, where the increase in public spending and the resulting investments made Ecuador’s economy more and more dynamic at the end of the past decade, with obvious reflections on the collective welfare. Moreover, the establishment of a safety net for the neediest and unemployed, and contributions in favour of families reduced the rate of poverty, making the institutions more credible and worthy of support in public opinion.

Table 2 Trust in political institutions

The values are factor scores obtained from the factor analysis. Positive values express citizen’s positive evaluation of political institutions. By contrast, negative values synthesize an unfavourable assessment in the institutions.

Source: Latinobarómetro (1996–2013).

The explanatory model

We estimated the effects of citizens’ economic perceptions on political trust among Latin American countries through different multilevel regression models. The dependent variable is represented, as described above, by an index (factor scores), which summarizes the levels of trust that citizens have in political institutions.Footnote 11 The main explanatory independent variables at the individual level are the perceptions of the current state of the national economyFootnote 12 and the status of the personal economic situation.Footnote 13 At the aggregate level, GDP per capita PPP and GDP growth were used.Footnote 14 Because the information that characterizes our data set has been collected over an extensive period (1996–2013) and considering that there is a temporal gap between changes in the economic situation and people’s perceptions, the information related to the real economy (GDP per capita PPP and GDP growth) was collected in the year preceding each survey.

A variety of information related to the dependent variable, collected both individually (gender,Footnote 15 age,Footnote 16 education,Footnote 17 income,Footnote 18 trust in people,Footnote 19 and satisfaction with democracyFootnote 20) and at aggregate level (government approval,Footnote 21 Gini index,Footnote 22 economic crisis,Footnote 23 and level of corruptionFootnote 24), were used as control variables. Finally, to overcome any problems of heteroscedasticity, we used the cluster standard errors.

The effects the economy has on trust in political institutions account for the differences among the countries of Latin America. In the first model (Table 3), whose variance explained is equal to 14.1%, we shed light on citizens’ personal and national economic perceptions. What emerges appears to confirm that a public perception of economic wealth fosters trust in political institutions. In fact, when citizens perceive a sense of economic well-being on a personal level, it appears more likely that they will trust their political establishment, when the perception of the national economy increases (b = 0.025). The combined effect of the two indicators underlines how the economy plays an important role in explaining institutional trust, namely the pattern of trust between governed and governors.

Table 3 Perception economic and political trust in Latin America

*P<0.1; **P<0.05; ***P<0.01; ****P<0.001.

Source: Latinobarómetro (1996–2013); World Bank (1995–2012); The Executive Approval Project (1996–2013).

The economy of Latin American countries in the last decades has undoubtedly been fluctuating, alternating positive trends with negative trends. The economic experience in this continent has certainly influenced the citizens’ economic perceptions. Nevertheless, the economic evaluation of citizens does not appear to be different from what emerges from the real economy. In fact, as shown in model 2, when citizens appear satisfied with their economic well-being, they support their political institutions more when the real economy, estimated in terms of GDP per capita PPP, increases (b=0.033). Although adverse economic experiences often are negatively correlated to economic knowledge (Kalogeropoulos et al., Reference Kalogeropoulos, de Vreese, Albæk and Van Dalen2015), Latin American citizens undoubtedly appear sophisticated, perhaps even more than the data in our possession allow us to estimate. This is confirmed when we analyse the empirical findings reported in model 3, whose variance explained is 13.9%. In fact, the combined effect of citizens’ national economic perceptions and economic growth increases the willingness of citizens to trust their political institutions (b=0.006). From this perspective, even when the public evaluates the economy from a sociotropic view, relying on its knowledge, it tends to positively evaluate political institutions.

In order to clarify the primary factors that nurture political trust, in the fourth model, whose variance explained is 14.2%, we considered all the independent variables analysed previously. The perceptions that citizens have of the personal and national economy have a significant impact on political trust (b=0.022 – H1 confirmed). Specifically, when citizens perceive a sense of personal economic well-being and, at the same time, they positively evaluate the national economy, they tend to trust more in their political institutions (see also Figure 2).

Figure 2 Average marginal effects of personal economic perception with 90% CIs.

While GDP per capita PPP (log) shows a negative effect on trust in political institutions (b=−0.059), unlike what is expected, the combined effect of individual economic perceptions and GDP per capita PPP on the dependent variable is negative, and it is not statistically significant (b = −0.014, H2 not confirmed). As people have more available resources, they should be more likely to have trust in political institutions and eventually appreciate political outcomes. However, at least in the Latin American countries, this is not the case, probably because the fluctuating trends of the economy and political instability induce citizens to fear political and economic upheavals.

When citizens express a positive view regarding the national economy, even in the presence of a negative economic performance, they tend to assess their institutions positively (b = 0.006, H3 confirmed, see also Figure 3). This may be due to the fact that the evaluations of economic performance expressed by citizens may be affected, and then reflect, their political predispositions in terms of support for the government, as well as their personal financial experience (Duch et al., Reference Duch, Palmer and Anderson2000). However, as the economy improves, marking a positive trend, it strengthens the trust of the citizens in the institutions. The results appear to attenuate the idea that random variation associated with the data survey can make the association between the information collected at the aggregate level and the individual level inconsistent (on this point, see Page and Shapiro, Reference Page and Shapiro1992).

Figure 3 Average marginal effects of National economic perception with 95% CIs.

The empirical findings obtained using individual and structural variables confirm our results. Even if the economic crisis continues to affect the nexus between the citizens and the political institutions (b = −0.010), those with a satisfactory income to cope with their individual and family needs support and trust the political institutions (b = 0.059). In general, education presents a negative relationship with the political trust index. However, those who have a higher education level appear to be less critical towards their institutions (b = −0.014) than those with a lower level of education; in contrast, those who approve the choices of the government, appear satisfied with democracy, trust in others seem to be more inclined to support political institutions. Finally, although the economic crisis, despite the passing of time, continues to represent a burden for political trust, when corruption decreases, the level of trust that citizens place in their political institutions increases (b = 0.116).Footnote 25

These results undoubtedly require consideration, because the choices that governments have taken in recent years among Latin American countries have generated clear dissatisfaction, fuelling a reactionary attitude in citizens. The radical opposition of the right and the loss of public trust in progressive governments in Bolivia, Argentina, and especially in Venezuela and Brazil, confirm this trend;Footnote 26 in Brazil, it was manifested openly with the last election and the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff. Undoubtedly, this scenario is affected by the economic crisis among the countries of Latin America, which having undermined the perception that citizens have of the economy, has eroded public support for democracy (see Córdova and Seligson, Reference Còrdova and Seligson2010). Nowadays, the citizens continue to swing between Western-style democracy and the personal and authoritarian role of charismatic leaders. Nevertheless, when the economy is perceived positively, citizens, in line with the theory of economic voting, tend to support their political representatives and political institutions.

Conclusions

The ongoing political and social transformations that have characterized the Latin American countries in recent decades have influenced the public’s attitude towards democracy. In some countries, where democracy has prevailed over authoritarian rule, democracy has been able to take root, and with many difficulties, to consolidate over time. In other areas, democracy has lost ground compared to the past, and the shadows of authoritarianism get reflected on different political systems. This is not without consequences. The continuous swing between democracy and authoritarianism has led citizens to become disenchanted with the type of regime and with the political system in general, and to be much more critical of its institutions.

In this work, by analysing public opinion in 18 countries of Latin America from a longitudinal perspective (1996–2013), we have assessed the economic effects that the citizens’ economic perceptions (national and personal) and the real economy have on trust in political institutions. The combined effect that economic dimensions (macro and micro) have on the dependent variable reinforces the idea, in line with the current literature on the subject, that the economy is one of the main determinants of political trust.

The main findings reveal, in more than half of the countries concerned, a rather critical public opinion, which is not afraid to disapprove of the performance of institutions, even in those contexts where authoritarianism is more rooted. Indeed, citizens’ dissatisfaction cuts across most of the countries that have been analysed and is equally present in countries where democracy has tended to consolidate and countries where democratic roots still appear to be a pipedream.

When the performance of the personal and national economy is positively perceived, citizens tend to trust in their political institutions. From this point of view, the citizens do not need to know precise economic facts in order to have trust in their political institutions. However, when the perceived economic assessment is combined with the performance of the real economy, the macroeconomic factors play a very important role. The empirical findings reveal that citizens trust their political institutions according to the country’s pocketbook, not their own. From this point of view, among the Latin American countries, the citizens’ political trust appears to be significantly oriented by their sociotropic perception, which, when in line with the trend of the real economy, appears to orient them to support political institutions, as they are considered capable of producing economic well-being for the nation. In fact, in those contexts where the public opinion positively perceives both the national economic level and the level of GDP growth, there is more political trust.

Unlike the expectations, hypothesis H2Footnote 27 is not confirmed. However, the (negative) sign that connects the variables with the dependent variable is particularly interesting because it appears to suggest that the citizens’ perceived or real economic well-being could play a very important role in defining their levels of political trust. The data in our possession do not allow an in-depth examination of this trend or a further exploration of the causes that determine it. Future research could shed light on this aspect by clarifying the dynamics that push the citizens not to reward political institutions, even in the presence of tangible economic circumstances, namely when real personal economic well-being is appreciable.

In conclusion, Latin American citizens, even in times of crisis, do not seem to remain passive in the evaluation of their institutions, rewarding them when perceived and real economic performance are evident.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Financial Support

The research received no grants from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agency.

Data

The replication data set is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp