Introduction

When we talk about the sharing economy within the current public debate, we usually refer to those practices where citizens collaborate in producing or using the same goods or services. Different kinds of goods and services can be shared in these practices and various kinds of collaborations are connected with them, as some scholars have already highlighted (Botsman, Reference Botsman2013; Kostakis and Bauwens, Reference Kostakis and Bauwens2014; Arena and Iaione, Reference Arena and Iaione2015; Pais and Provasi, Reference Pais and Provasi2015; Arcidiacono et al., Reference Arcidiacono, Gandini and Pais2018). In this paper, we will focus on how local governments tackle and govern the emerging phenomenon of sharing practices, exploiting the concept of governance arrangement that is the continuous and guaranteed presence ‘of representatives of those collectivities that will be affected by the policy adopted’ (Schmitter, Reference Schmitter, Grote and Gbikpi2002: 56).

The main objective of this paper is to examine how institutions and private actors collaborate for specific kinds of policies – those related to the production and spread of sharing economy practices. This subject is of particular interest because it represents one of the rare cases of governance of a collaborative policy (Lewanski, Reference Lewanski2013; Ravazzi, Reference Ravazzi2017). However, the focus here is on the governance structure (the decision-making process) rather than on the output (the regulation of the sharing economy). The latter aspect is a rather specific collaborative policy content which is not questioned in this paper. Indeed, scholarly debate on the collaborative nature of the sharing economy is quite broad and out of the scope of this paper (Botsman, Reference Botsman2013; Belk, Reference Belk2014; Pais and Provasi, Reference Pais and Provasi2015).

By sharing practices, we mean practices such as co-working, co-housing or co-operation in the organizing of social activities where the production of common goods is detectable, and not those where citizens collaborate to produce the goods or services which are not clearly sharable with others (Botsman, Reference Botsman2013; Kostakis and Bauwens, Reference Kostakis and Bauwens2014; Arena and Iaione, Reference Arena and Iaione2015; Pais and Provasi, Reference Pais and Provasi2015; Manzo and Pais, Reference Manzo and Pais2017). We will focus on two case studies involving local governments which have implemented policies to promote sharing practices, focusing on the similarities, differences, and outcomes of these policies.

We begin by presenting several elements of the scholarly debate on the relationship between local government and civil society in the last 20 years, a debate which is central to the challenges faced by policy-makers in Italy and Europe at various institutional levels. In the first part, we will highlight the political role framed as an investment for the success (or failure) of local policy programmes. In the second part, after a presentation of our research design, we will explore the cases of Milan and Mantua, in particular from the perspective of how to manage the relationship between local government, civil society, and economic actors dealing with sharing practices. Finally, we will present considerations linked to the empirical analysis and a concluding comment will be made on the specific tools, resources, and intensity of the political investment at local level to regulate, foster, and govern sharing practices.

Political exchange, political investment, and sharing practicesFootnote 1

Despite not being collaborative in its nature, governance is per se a co-managed tool, blurring the boundaries between the private and public sectors (Bassoli, Reference Bassoli, Bassoli and Polizzi2011; Bassoli and Polizzi, Reference Bassoli and Polizzi2011). We consider a partnership to be a formalized co-operation mode among public and private actors that involves co-regulation processes, for example, the co-management of the policy-making process and the creation of one or more ad-hoc administrative structures, often in the form of ‘steering boards’ (Vesan and Sparano, Reference Vesan and Sparano2009a). Although an implicit governance of the sharing experiences may exist, the presence of a more or less formalized governance structure is rarer. It is, however, beneficial in the regulation of the societal and political processes (Vesan and Sparano, Reference Vesan and Sparano2009a). Indeed, scholars have dwelt at length on governance literature on the issue of partnering and its consolidation. Given the debate surrounding the term partnership (Teisman and Klijn, Reference Teisman and Klijn2002), we prefer the use of a more general term, network governance arrangements (NGAs) (Bassoli, Reference Bassoli2010, Reference Bassoli, Bassoli and Polizzi2011), where an administrative structure (as an independent legal entity) is not required but the presence of a formalized governance structure is implied. Indeed, NGAs are based upon mutual accommodation involving a more or less close and codified interaction between public and non-public actors, including social partners. According to Bassoli (Reference Bassoli2010), NGAs feature a focus on the output/product, a clear selection of (a few) stakeholders and an emphasis on negotiation. Overall, the structure is closed since the selection of participants is made ex-ante, although changes may occur at a later stage.

According to some scholars (Vesan and Sparano, Reference Vesan and Sparano2009b), one of the main aims of a partnership (as a specific form of an NGA) should be to produce the so-called local collective competition goods, namely those goods and services that may provide competitive advantages to a local community in terms of adequate infrastructure, business services or specialized know-how (Crouch et al., Reference Crouch, Le Galés, Trigilia and Voelzkow2001; Pacetti, Reference Pacetti2009; Polizzi et al., Reference Polizzi, Tajani and Vitale2013; Manzo and Ramella, Reference Manzo and Ramella2015). Sharing practices are de facto considered local competition goods triggering city competitiveness, as it is clear looking at the literature on Seoul Sharing City or related topics (Bernardi Reference Bernardi2018; Baslé, Reference Baslé2016). The basic assumption behind local competition goods, or partnership in general, is that without achieving a certain amount of material and immaterial resources through the participation of different local actors, the production of these goods would not be sufficient via independent and autonomous action. However, the creation and maintenance of an NGA also imply specific participation costs. In fact, the actors are called on to invest several resources in the co-operation, such as time and dedicated financial resources for the co-funding of programmes, and a partial delegation of some rights due to a sharing of responsibilities in resource use. It follows that active participation in an NGA will only be considered attractive if local stakeholders anticipate a gain. What therefore are the main advantages and the underlying rationale that could guarantee the support of such practices?

According to Vesan and Sparano (Reference Vesan and Sparano2009b), a partnership is a form of political exchange in which the actors invest some of their resources (material or immaterial) in order to obtain specific gains. They distinguish between two main groups of actors: public authorities and the representatives of socio-economic interests (and private actors at large). Regarding the role of local authorities in NGAs, it seems clear that their central interest in a partnership concerns its capacity to provide new opportunities to maintain and increase political consensus. In other words, the active involvement of public authorities in a public–private experience will be guaranteed if it is considered a politically profitable investment. In particular, three types of political advantages seem crucial to building, preserving, and increasing consensus, namely political visibility, problem-solving capacities, and economic resources availability.

The political visibility potential of the partnership is crucial to political actors reliant on an electoral mandate. A partnership may increase political attractiveness and therefore aid in maintaining the political role. Thus, if the existence and promotion of a co-operative framework supports the perception among local key actors, local media, and voters that public authorities are politically productive and successful, there will be strong incentives for NGAs to perpetuate. In line with this, local administrations can play on the certification mechanism (McAdam et al., Reference McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly2001) as a symbolic incentive in mobilizing strategic actors. This aspect becomes increasingly important when cities suffer from a lack of economic incentives for social actors, as seen in Italian municipalities in recent years where gross investments were cut by 35% between 2006 and 2016, falling to €18.5 billion. Honouring social actors with symbolic incentives becomes a form of political opportunity to legitimize the actors of the city's public spheres (Caruso, Reference Caruso2015; Vitale, Reference Vitale2015) because it acknowledges them as strategic actors in the local government's implementation of innovative policies.

The second possible advantage deals with the contribution that the partnership may make to the solution of specific problems of urban governance. Sharing practices may be perceived as a new challenge and a threat to the status quo. If the partnership arrangement is considered a strategic device to confront legal weaknesses and co-ordination problems, enhancing the institutional capacity of local administration, there will be a shared (i.e., public and private) interest in promoting and preserving it.

The third main political advantage is linked to the fact that a governance arrangement can serve as a useful tool for access to new funding opportunities. If a partnership proves to be a profitable strategy in obtaining a goal, it will be considered a politically profitable activity. Since building new and ad-hoc co-operative arrangements may involve high transaction costs, local authorities may have an interest in preserving an ongoing co-operation, especially when it is regarded as a suitable starting point for the collection of new resources. Moreover, when the co-operation is perceived by the local administrations and social actors involved as a symbolic certification process, the investment costs are considerably lower than those needed in a situation of economic incentives. It is thus clear that local authorities must weigh the cost of the political investment against the profit of the investment itself. This process is far from being publicly acknowledged by political actors or from being a fully conscious one. Nonetheless, both Vesan and Sparano (Reference Vesan and Sparano2009a, Reference Vesan and Sparano2009b) and Bassoli (Reference Bassoli2010) find evidence in the specific cases that they analyzed, territorial pacts in Turin and development agencies in Milan, that the underlying mechanism of public intervention is that of political exchange.

Apart from the potential ‘political profitability’ for local authorities, a second decisive aspect which characterizes the political exchange model and partnerships is the capacity of a partnership to provide particular ‘goods’ for the socio-economic actors involved. Assuming that a partnership needs to be supported by a sufficient amount of resources to deliver the expected services and projects, a crucial question is, why do socio-economic actors have an interest in an active participation in such a partnership? One of the most important incentives is probably due to its selective socio-economic profitability (Vesan and Sparano, Reference Vesan and Sparano2009a), the possibility that actors may affect decisions regarding the distribution of costs and benefits produced by the partnership itself. Choices related to, for example, the creation of a Fab Lab or a specific service for start-ups, or the distribution of financial support for local innovators, may be extremely significant for the local actors involved in co-operation practices.

The ideal-typical logic of political exchange forming the basis of partnership co-operation may, therefore, be considered as the first step towards a full understanding of the set-up of a network governance arrangement for sharing practices. On the one hand, public authorities provide time and administrative resources, financial support, and political impetus as well as a quota of their decisional power to the partnership in exchange for political advantages, for example, the acquisition or increase in political consensus. On the other hand, the socio-economic actors barter political support with local authorities and may also supply financial or logistical assets, with the purpose of achieving favourable decisions regarding the benefits connected to the implementation of partnership arrangements. Finally, a shared aspect relates to the ‘dispersion of responsibility’ (Vesan and Sparano, Reference Vesan and Sparano2009a): the partnership is publicly responsible for the implementation of the activities’ (Bassoli, Reference Bassoli2010: 501), shielding each partner from blame and direct responsibility (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The political exchange involved in partnership experiences. Source: Vesan and Sparano (Reference Vesan and Sparano2009a: 51) with adaptation.

Nevertheless, if considered per se, neither the political remuneration nor the selective socio-economic profitability resulting from a partnership can fully explain the success of the governance arrangements. Detecting specific interests in the emergence and preservation of the partnership experience is not sufficient to account for the institutionalization process since exogenous or endogenous pressures which may inhibit its reinforcement and hinder its duration can challenge such a co-operative experience. Several empirical research studies of Italian territorial pacts have shown that many partnerships find it difficult to offer selective incentives beyond the initial phase (Cersosimo and Wolleb, Reference Cersosimo and Wolleb2001; Piselli, Reference Piselli2005). This is understandable when we consider that consolidating a partnership experience relies upon a continuous process of consensus and coalition-building and the promotion of internal and external interest in its maintenance. According to Vesan and Sparano (Reference Vesan and Sparano2009b), four conditions should be considered for long-term sustainability: the availability of economic resources (Mackintosh Reference Mackintosh1992), the presence of a ‘policy entrepreneur’ (Cersosimo and Wolleb, Reference Cersosimo and Wolleb2001; Vangen and Huxam, Reference Vangen and Huxham2003; Purdue, Reference Purdue2005), the presence of a ‘technical unit’ and the ‘political homogeneity’ of the public administrations involved (for an alternative argument, see Barbera Reference Barbera2001; Magnatti et al., Reference Magnatti, Ramella, Trigilla and Viesti2005). These four conditions lose most of their predictive capacity whenever the specific mode of governance is not that of a partnership. As it is often the case, sharing practices are supported by public institutions in close co-operation with private actors not in the form of a clear partnership. Therefore, in more loose arrangements, these conditions may take different shapes. While the presence of policy entrepreneurs and economic resources are needed independently, a technical unit rarely is foreseen, although a governing body may be present. Finally, the presence of political homogeneity is meaningful only when the partnership features different elected political bodies.

Moving this framework of analysis to the recent wave of the (tentative) governance of sharing practices seems not only possible but also convenient. However, in this case it seems even more relevant to look at the political investment per se, not only as a political exchange (resources, time and dedication vs. visibility, consensus, and resources) but as a truly political act in which, with reference to David Easton (Reference Easton1965), the local authority exercises its power to provide a new (non-) authoritative allocation of resources. In the new wave, the political investment tends towards a political endorsement of the sharing practices. In fact, the ongoing political debate about the role of the sharing economy in our cities (USCF, 2013) is resolved at local level, where each public administration makes specific choices regarding which practices deserve to be promoted, which actors are to be included, etc.

Research design

Scholars have pointed out that the term ‘sharing economy’ is poorly defined (Pais and Provasi, Reference Pais and Provasi2015; Frenken and Schor, Reference Frenken and Schor2017). In line with Frenken and Schor (Reference Frenken and Schor2017), we consider the sharing economy to be ‘consumers granting each other temporary access to under-utilised physical assets (‘idle capacity’), possibly for money’, but we leave the field open to what public authorities consider the sharing economy to be when attempting to regulate the field. The reason for our choice lies both in the need to clearly identify a core number of practices (those sharing sharable goods) (Benkler, Reference Benkler2004), as well as the recognition that individual local administrations independently define the boundaries of the field in accordance with their own regulatory aims.

This choice allows us to include all those efforts put in place by local municipalities ‘(1) encouraging a better understanding of the sharing economy and its benefits to both the public and private sectors by creating more robust and standardised methods for measuring its impacts in cities, (2) creating local task forces to review and address regulations that may hinder participants in the sharing economy and proposing revisions that ensure public protection as well, and (3) playing an active role in making appropriate publicly owned assets available for maximum utilization by the general public through proven sharing mechanisms’ (USCF, 2013).

Given the wide variance in the competences local authorities have internationally, we decided to focus on a single country, allowing us to follow the development of the governance arrangements in more detail. Italy, the chosen country, features three important assets: the presence of cities which are members of the sharing cities network (Sharable, 2017) as well as important case studies (MIT, 2017), the presence of a wide public debate (Sharitaly, 2017) and a constant attention to the role cities may play (Iaione, Reference Iaione, Polizzi and Bassoli2016; Labsus, 2016). The latter aspect is of utmost importance for this paper and drives not only the selection of the country, but also the case selection within Italy. We chose a most-different system: Mantua, a small town with a pilot project supported by Labsus (an Italian think tank working on the concept of subsidiarity), and the major city of Milan, the Italian economic engine featured in all international comparisons (Gascó et al., Reference Gascó, Trivellato, Cavenago, Ramon Gil-Garcia and Pardo2015; MIT 2017) and in the scholarly literature (Vitale, Reference Vitale and Moulaert2010; Cavenago et al., Reference Cavenago, Trivellato, Gascò, de Lancer Julnes and Gibson2016; Armondi and Bruzzese, Reference Armondi and Bruzzese2017; Polizzi and Vitale, Reference Polizzi and Vitale2017). Milan is a well-known case where the municipality played an explicit governing role on these issues with no technical support from external agencies. Among the other cities supported by Labsus (2016), Mantua is the only one created by a public administration (Chamber of Commerce) and not by a municipality, suggesting a lower political investment by the latter institution. Both local administrations emphasize their interest in the field of sharing economy with the naming of an ad hoc councilperson. The principal difference between the two cases lies in the type of political investment the two administrations have invested in the policy field.

We looked at the governance arenas established by the cities and at the product of the governance process for an in-depth understanding of the governance structure. We relied on various resources and techniques for our analysis. The research referred to any available secondary data (both formal and informal documents) produced by the main actors (Co-Mantova, 2015a; Comune di Mantova, 2015; CCIAA, 2016a, 2016b; Comune di Milano, 2016; Pasqualini, Reference Pasqualini, Polizzi and Bidussa2017) and featured three batches of in-depth interviews. The first batch concerned the key national actors and regarded the sharing economy state of the art in Italy and the most interesting cases (Annex 1). Public and private actors directly involved in the governance arrangement in Mantua and Milan were subsequently interviewed (second and third batches). Their perception is what allowed us to detect their attitude towards the policy-making process. The fieldwork took place between March 2015 and July 2016 (Annex 1). In Milan, we also carried out participant observations of meetings between the mayor's delegate and the sharing economy actors. The municipality granted access to these meetings (February 2015 to November 2016) during the research project period.

The Milan case

The Milan case offers an interesting history of institutional action specifically orientated towards fostering sharing practices in many policy fields such as mobility, internet access, self-employment and digital craft workers, welfare and social activities, participatory budgeting and fundraising for social projects (Andreotti, Reference Andreotti2019).

Although the sharing economy is presented in Milan as an overarching concept (Int. SE1; SE2), the mayor had chosen a politically important councillor for labour and economic development who paid specific attention on social innovation policies. This choice publicly endorsed the councillor as the policy entrepreneur, but also streamlined the narrative of the sharing economy along the rhetoric of social innovation. Our analysis focused mainly on two core areas of Milanese sharing practices: labour policies and social innovation policies. In the area of labour policies, the municipality targeted youth issues by investing in the support of shared services for self-employed and digital craft workers. In particular, the municipality allocated funds for refurbishing spaces and workstations and created a voucher system to sustain the cost for co-workers to rent a location for their work (Int. MI3) (Mariotti et al., Reference Mariotti, Pacchi and Di Vita2017; Andreotti, Reference Andreotti and Nuvolati2018). This measure was granted to 49 co-working spaces and reached 364 co-workers in 30 months. The municipality has also promoted Open Care, a platform to develop prototypes of community-driven social and healthcare services, exploring both social implications and their scalability. Mutual support activities among neighbours have been fostered, and a pilot project was initiated to implement a system of care-giving services shared by citizens living in the same building (or block) in order to facilitate social interaction among neighbours, known as Social Streets (Pasqualini, Reference Pasqualini, Polizzi and Bidussa2017)Footnote 2 (Int. MI4). In the last years of Mayor Pisapia's mandate, between 2014 and 2016, the municipality politically endorsed these sharing economy actors and publicly acknowledged the whole process by opening it up to public debate through a series of public meetings. Other important events were held such as the Collaborative Week festival under the aegis of the municipality and the direct intervention of a considerable number of local sharing economy actors. The last act of this process was the opening of Co-Hub in March 2016, the first public space designed for the promotion of and training for the sharing economy. In all these measures we can detect an exchange dynamic: the Milan administration provided funding, visibility, and public endorsement to private actors of the sharing economy who reciprocated with services perceived as public goods of social impact.

Some of the most important policies in this field were preceded by a listening phase conducted through meetings and visits with experts and stakeholders. A participatory approach was adopted in the design of the Milan Sharing City document, the official guidelines for the sharing economy policies (Int. MI1). The process provided local actors with complete autonomy, given that the agents themselves define the rules of their actions (Maggi, Reference Maggi2003: 122). The draft of this municipal document was presented to operators and experts at a public event before being subjected to a collective review process by sharing it on a website for over a month, giving operators and experts the opportunity to comment and amend it. A questionnaire was made available, requesting an assessment of the process. The project reached more than 200 people (including operators of established companies or start-ups, researchers, community groups, shared service users, and citizens interested in the subject)Footnote 3. By using this tool, the administration gained three outcomes: it gave a symbolic acknowledgement to the sharing economy actors, it gained their relational trust (Int. MI1, MI4, MI3, Sennett, Reference Sennett2012) and it prevented critical voices from contesting the regulation process. At the same time, the private actors obtained: policy guidelines for the sharing economy sector tailored to their own needs, high public visibility, and a loose regulation that left them a large autonomy to develop their own activity.

Thereafter, the municipality created a register of operators and experts in Milan dealing with the sharing economy to ‘map, enhance, connect and adjust those territorial initiatives related to the economy of sharing and collaboration’ (Comune di Milano, 2017). This roster is a record of 104 actors divided into two types: economic stakeholders and sharing experts. Choosing to include a category of experts in the roster as well as sector stakeholders has made it possible to build not only an interest group but also a self-reflective group dealing with this phenomenon.

Another important element of the Milan case relates to the regulation approach taken by the municipality. The regulation of sharing economy practices is a controversial issue. Many operators requested the sector not be regulated, expressing concern that a complicated set of rules could reduce its innovative power. On the other hand, observers, experts, and many operators have underlined the risk that without regulation this sector may be dominated by the largest market players at the expense of small and locally based actors. The commercial success of companies such as Airbnb® and Uber® are increasingly identified as the most obvious examples (Int. SE1). This tension reflects a debate many scholars have contributed to in recent years (Scholz, Reference Scholz2014; Gorenflo, Reference Gorenflo2015). A complication is that in Italy the municipal level has rather limited legislative powers on this issue, compared to the national government.

Notably those tensions (big players vs. local players, regulation vs. non-regulation, participatory approach vs. hierarchy) have been tackled directly without leaving room for non-decisions. The city has adopted an approach primarily based upon the co-design of the rules, such as the one used to write the Milan Sharing City guidelines, rather than imposing new rules on the local stakeholders (Pais et al., Reference Pais, Polizzi, Vitale and Andreotti2019). This approach, together with the autonomy granted to the private sectors, produced the ‘dispersion of responsibility’ (Vesan and Sparano, Reference Vesan and Sparano2009a). Furthermore, its regulative policy was based upon incentives rather than on prohibitions, as in the case of co-workers and maker-spaces. The city chose not to rule out any actor, tending rather to use extreme caution in cases of very controversial actors such as Uber®. As in many other cities across the world, a decided animosity has developed in Milan in recent years between taxi drivers who accuse Uber® of operating an unfair competition based upon unskilled labour who are inadequately paid, and the supporters of Uber® who highlight its benefits for consumers in terms of the price of mobility and the efficiency of the service. The municipality of Milan chose to avoid these tensions by moving the dispute from the sharing city process and managing the controversy in a specific forum on mobility issues. The outcome of this process can be detected in the interviews among the actors involved and in other evidences. At the end of the political mandate of Mayor Pisapia, an overall consensus about its policy on sharing practices was visible among the sharing economy actors (SE2, SE3, SE4, SE5). The presence of the sharing policy among the issues put forward by the centre-left coalition during the 2016 municipal electoral campaign suggested that it was perceived as a political success. Moreover, some external public acknowledgments in the last few years confirmed indirectly the good level of consensus of Milan citizenship for the administration policies in issues connected with the sharing economyFootnote 4.

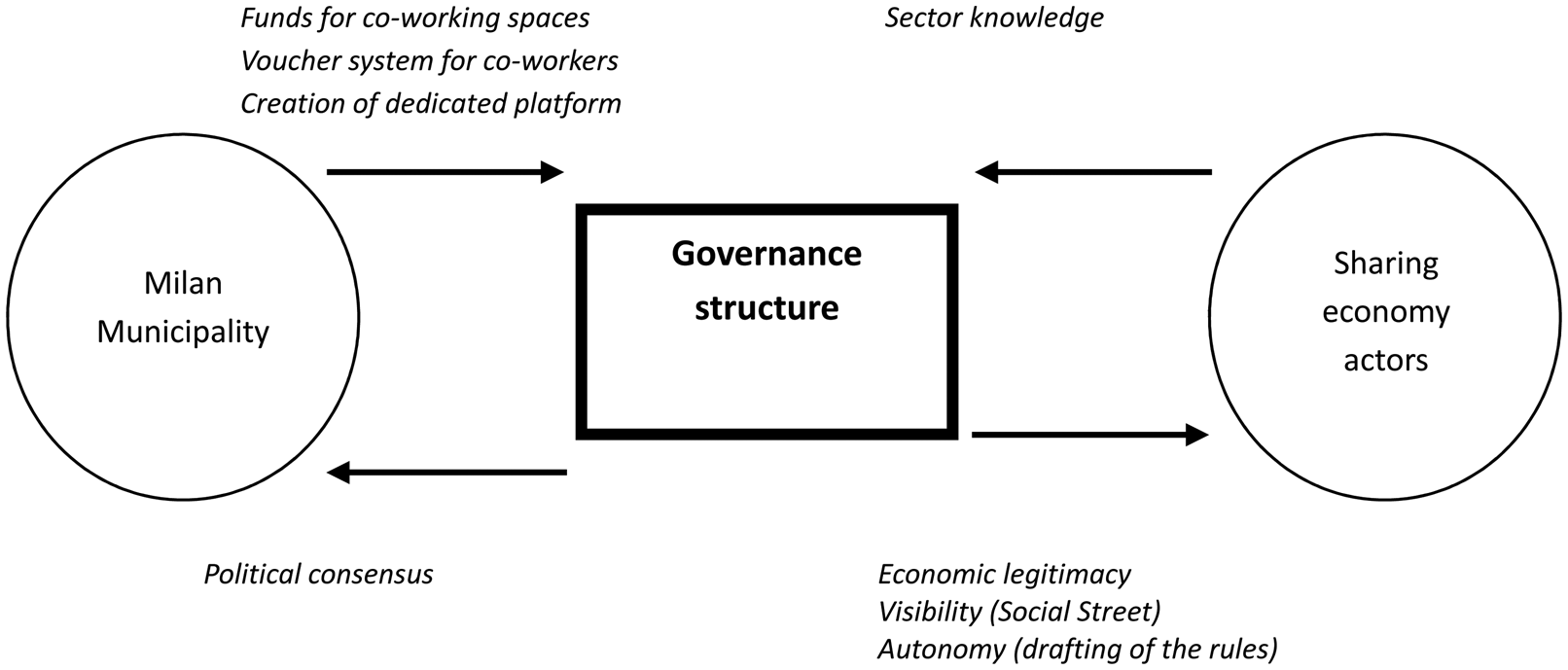

The Milanese case shows a specific political exchange dynamic created by the local administration: the municipality created an institutional environment able to empower the sharing economy actors and involve them in the regulatory process while receiving a political consensus and a clear recognition of its pivotal role. The private enterprises, on the other hand, were provided with autonomy and thus reassured by the non-invasive regulations; they also received public visibility and publicity in the roster. Thanks to the high visibility of the overall process, the remuneration of public support to the mayor was quite high, while the sharing economy sector was at the forefront of the public debate and thus gained visibility and public acknowledgement in its economic role. Overall the exchange dynamic is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The political exchange involved in the Milan partnership experience.

The Mantua case

The Mantua case is an interesting example of an institutional action specifically orientated towards the fostering of sharing practices at the crossroads between cultural policies and labour policies. Moreover, it features the Chamber of Commerce (CCIAA) as the political entrepreneur of the process, with a subsidiary role of the municipality and the province. This latter aspect is what makes the Mantua case peculiar among the increasingly numerous experiences of governance on sharing economy. Indeed, the specific nature of CCIAA changes the nature of the political exchange because political consensus is not remunerative for CCIAA, while it is crucial for the political administrations (municipality and province).

On a more practical level, the process was twofold: on the one hand, the governance of the experience was institutionalised under the label Co-Mantova, on the other, the promotion of specific sharing practices took the vast majority of the resources. The governance process was established in two years (2013–2015), with the Chamber of Commerce playing a leading role, while the sharing practices both precede and follow the political process. In the present phase (2016–2018), these practices are continuing on their own without clear political leadership but under the close co-ordination of the Chamber of Commerce. Among the most interesting results are the provincial registry of co-working places (CCIAA 2016a, 2016b), the continued activities presented under the Co-Mantova label (Co-Mantova, 2015a), the Fatti di Cultura festival (since, 2015), a fund-raising website (Co-Mantova, 2019) and a recognized trademark (Co-Mantova, 2018). An additional aspect of Co-Mantova is the specific narrative of the experience and the underlying framework of understanding that it provides. The Mantua Chamber of Commerce decided to promote the sharing economy with technical support from Labsus (2016). This technical support framed the activities according to specific lines of intervention and understanding.

‘Co-Mantova is a prototype of an institutionalising process to run cities as a collaborative commons […] and therefore as ‘co-cities’. Co-cities should be based on collaborative governance of the commons […] whereby urban, environmental, cultural, knowledge and digital commons are co-managed by the five actors of the collaborative governance – social innovators […], public authorities, businesses, civil society organizations, knowledge institutions (i.e. schools, universities, cultural academies, etc.) – through an institutionalised public/private-people/community partnership. This partnership will give birth to a local p2p physical, digital and institutional platform with three main aims: living together (collaborative services), growing together (co-ventures), making together (co-production).’ (Iaione, Reference Iaione2014)

As is clear from Iaione's brief description, Co-Mantova is innovative for several reasons, resembling the Bologna case (Comune di Bologna, 2014a) and evidently differing from the Milan case. Firstly, the regulative and triggering environment was developed by the Chamber of Commerce in close co-operation with a set of local actors, with the technical support of Labsus (2016). Secondly, while possessing grass-roots elements, it also features a strong institutional involvement, but the local municipality is not a pivotal player. Thirdly, the project deals mainly with cultural life in its diverse conceptualisation, involving co-working sites, tourism, events, etc. as different ingredients of its cultural promotion. In the Mantua case, the sharing economy therefore involves the conceptualisation of social and cultural innovation practices, rather than the implementation of employment policies as it was in Milan. Also, the promotion of co-working sites is framed as a social and cultural practice rather than as job opportunity or job support. Since the inception of the first co-working site (2015) the project has underlined that ‘co-workers are […] sharing the same vision: working together not only for their own promotion but for a redevelopment of the city through events and activities that shake the usual torpor of Mantua. In fact, the goal [was] to give life not only to a commercial venue but to an active and collaborative place not only internally but also towards the city through meetings, contaminations and events’ (Co-Mantova, 2015b).

In order to understand the scope and aim of the Co-Mantova project, we shall briefly describe its development, stressing the inclusive strategies adopted to build the network, along with the topics covered as time passes. The first seed of collaboration among local stakeholders blossomed within the Chamber of Commerce. The Mantua CCIAA established the so-called Civil Economy and Cooperation Working Group (CECWG) in 2005 as a meeting place to promote co-operation in the classic Rochdale meaning (Walton, Reference Walton2015). Co-operatives are part of the CCIAA, and are major, specific, economic players in Mantua.Footnote 5 The working group is an open space, although it also features permanent deputies, including representatives of the national associations of co-operatives, of the province, of the local social pact and of specific co-operatives. The working group foresaw an internal equilibrium between the political dimension (the province) and the economic dimension (co-operatives), as well as between the Catholic and the leftist political sub-cultures that remain strong in Italy (Bassoli and Theiss, Reference Bassoli, Theiss, Baglioni and Giugni2014; Bassoli, Reference Bassoli2016).

The CECWG faced legitimacy problems within the CCIAA because the rhetoric and language employed in the co-operative world (Int. MN1) differ profoundly from the standard approach of the SMEs which make up the bulk of the Mantua CCIAA members. Nonetheless, the CECWG was able to promote a series of important events and projects (CCIAA, 2016c) ranging from promoting shared corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices for local co-operatives to implementing a co-operation festival for a wider audience in the city of Mantua. The CECWG was very active and in 2013 promoted the idea of a Subsidiarity Laboratory: Enterprises and the Commons. The Subsidiarity Laboratory was organized in close co-operation with the association Labsus-Laboratorio per la Sussidiarietà (2016). The association, closely connected with the LABoratory for the GOVernance of Commons (LabGov, 2016), is directly connected to the University Luiss of Rome.

Labsus had stressed the importance of involving enterprises, lay citizens and public administrations in answering ‘the tragedy of the commons’ (Lloyd, Reference Lloyd1833). At the same time, the Subsidiarity Laboratory noted co-production practices already implemented in the city in previous projects (Il tempo dei giovani, Cittadino steward, Bottega di mestiere nel gusto mantovano), existing policies (Il distretto culturale Le regge dei Gonzaga) and local competences (Master in co-operative management, Master in valorization of the territorial assets, and cultural-touristic hospitality). Labsus proposed four general steps which were later adopted by CECWG: (1) validation of the approach, (2) assessment of the actors to be involved, (3) definition of the programme and (4) final presentation. According to the interviewees (Int. MN1, Int. MN2), the general aim was to promote an agreement on how to tackle the issue of urban commons, exploiting a shared and collaborative approach between public administration, civil society, citizens, and all possible stakeholders, something closer to the Bologna ‘Regulation for the Care and Regeneration of the Urban Commons’ (Comune di Bologna, 2014b; Bianchi, Reference Bianchi2018).

However, the process was developed along somewhat adjusted lines, based on previous experiences such as the ‘Culture as a Common Good’ call for ideas launched by the province of Mantova, the Cariplo Foundation and the Chamber of Commerce. As a result, the focus was placed upon three actions: the establishment of a FabLab for the shared production of cultural goods and activities, the elaboration and implementation of instruments to facilitate co-operative place-making of cultural spaces and a cultural enterprise incubator.

With this in mind, CECWG and Labsus co-organized the living laboratory as a co-design process pivoting around Labsus training held from June to November 2014. At the end of the workshop, the results were made public during the Festival of Cooperation (Labsus, 2014), which featured the presence of Michel Bauwens (P2P Foundation), Sheila Foster (Fordham University, LabGov), and Neal Gorenflo (Shareable) as keynote speakers.

These experiences, and above all the continuous development of shared projects, helped local actors in developing mutual compromises (regarding divergent objectives) and understandings (Int. MN1, MN2). According to key stakeholders, technical and management meetings were also crucial in establishing trust (Int. MN2). In concluding this lengthy process, local actors presented an agreement entitled CO-MANTOVA Patto di Governance Collaborativa per uno Sviluppo Economico Locale a partire dai Beni Comuni (Collaborative Governance Pact for Local Development from the Commons). The pact was released publicly in February 2015 to positive reactions. The pact was initiated by the Chamber of Commerce and promoted by two informal groups (RUM – Mantua Urban Regeneration and OURS 2.0), the province of Mantua, the municipality of Mantua, two consortia of co-operatives (Solco and Pantacon), a foundation promoting the local university (Fondazione Università di Mantova), and other associations (ARCI and CSVM). However, it never came into force as it remains unsigned. The timing of the pact was not fortuitous; the municipal administration was at the end of its mandate (May 2015), the province was on the verge of shutting down (Bussu and Galanti, Reference Bussu and Galanti2015) and local actors preferred to await the election of the new local administration. Notably, the new municipal administration decided against direct investment in the tool, which continued, however, to generate interest. The incoming mayor created a new councillor's office responsible for legality, local police, the digital agenda, smart city and civil protection. This created momentum for smart city-related affairs but not for issues concerning the sharing economy (Int. MN3). However, the choice implicitly blocked the ongoing Co-Mantova process, the (rather sectorial) projects dealing with the sharing economy then fell under the responsibility of a second councillor for welfare, the third sector, creativity and youth participation, and immigration. This latter position has the specific right to be involved in the Cultural Creative Hub, as noted in the formal announcement (Comune di Mantova, 2015). Despite this division, which provides further insights into the weak links between the sharing economy and smart cities (Sadoway and Shekhar, Reference Sadoway and Shekhar2014; Saunders and Baeck, Reference Saunders and Baeck2015), it is important to stress that Smart City Mantua mainly relates to the concept of mobility, inter-operational mobile app and the internalization of the data processing centre. By contrast, the Co-Mantova project deals with cultural life only, as is clear from the activities put forward and the documents produced (Co-Mantova, 2015a).

Overall, Mantua underlines the importance of political investment (Bassoli, Reference Bassoli2010). The absence of political will on the part of the municipality could not have been substituted by efforts by other public institutions (CCIAA and the province). The governance of the sharing practices was itself successful, but rather limited in its capacity. The limits of the political exchange were clearly shown. On the one hand, the public actor (CCIAA) and private actors co-drafted policy guidelines tailored to their own needs. The process also gave a symbolic acknowledgement to the sharing economy actors both as emerging economic actors and decision makers and it prevented critical voices from contesting the regulation process. On the other hand, without the political endorsement of the public authority (municipality) the agreement was useless. This directly affected the political exchange: while the CCIAA was recognized in its pivotal role, neither the municipality nor the province gained political consensus, given their marginal role in the whole process. The participatory approach in this case, did not produce any concrete results and its effects were limited to the formal co-ordination of existing practices. Notwithstanding these limitations, the private actors obtained public recognition of the sharing economy sector, public visibility, and autonomy. Moreover, all involved actors are constantly able to re-finance their activities thanks to dedicated public tenders. Overall the exchange dynamic is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The political exchange involved in the Mantua partnership experience.

The internal dynamics

The two cases presented above demonstrate the presence of dynamics valuable in understanding how the governance has been built in two cities which have been considered as frontrunners in Italy for the sharing economy. Therefore, we tried to detect similarities and differences between them and what kind of exchange has occurred between local administrations and private actors at the city level.

Similarities can be found in the creation of the government arrangement itself and in the mutual trust among the actors involved through the support and guidance of the pivotal public institution. Both the municipality in Milan and the Chamber of Commerce in Mantua invested time, funding and manpower resources in the participatory process, triggering a sense of belonging to the process – also for those with a limited role (Int. MI1, MI4, MI3, MN3, MN4) – and opened the process to contributions from private actors. In both cases, the political entrepreneurs were clearly identifiable and publicly visible in Milan only. In both cases, the majority of the actors in the field adopted a collaborative approach and felt confident about the reliability of one another, as confirmed by the absence of counter measures or hard bargaining approaches among them (Barbera, Reference Barbera2001). The public institution fostered co-operation by providing ad hoc working spaces (Co-Hub in Milan and FabLab in Mantua) and public events (Collaborative Week and Festival of Cooperation) and by implementing existing project experience such as that of the province's call for ideas (in Mantua). Consequently, local actors were able to meet and enhance their collaborative project without the burden of additional participatory efforts. Moreover, the fact that newly founded associations (such as RUM in Mantua) could enter the political arena on the same footing as well-established co-operative or pivotal actors indicates that the collaborative arena was very inclusive. In other words, as already noted elsewhere (Bassoli and Polizzi, Reference Bassoli and Polizzi2011), when a governing body organizes institutional arenas for co-operation it provides an opportunity for social actors to interact, reduces the costs of co-ordination between them and increases the capacity to co-operate with other actors.

On the other hand, the two cases are different as regards the political investment. The municipality of Milan gave a high visibility to the process and politically endorsed the whole sharing practices sector through its own mayor's delegate office by providing strong support and visibility to the private actors and a soft regulation approach to prevent political conflicts. We detected a profitable exchange between the political investment and the political consensus. In Mantua, the Chamber of Commerce, which is a public institution but not a political actor, fully supported the process by providing time and resources, technical support, and expertise thanks to Labsus. Trust flourished as a direct consequence of the truly open nature of the process. The participatory attitude was not only presented as a practice to be diffused but also as a working method. We detected a major role of experts in crafting a specific understanding of sharing practices as being deeply connected to those of commons (Arena and Iaione, Reference Arena and Iaione2015; Iaione, Reference Iaione, Polizzi and Bassoli2016). In this respect, the existing dynamics studied in the field of participatory governance arrangements (Cataldi, Reference Cataldi, Bassoli and Polizzi2011) can also be found in this new wave of societal activationFootnote 6. The Chamber of Commerce could not, however, provide the political endorsement and visibility that only local administrations can grant to NGAs (Bassoli, Reference Bassoli2010). Neither the old mayor nor the new one provided the required political investment. The governance of the sharing practices was not in the political agenda, as it is not now.

In conclusion, we must note that a single analysis of two case studies cannot allow us to understand relations among actors and regulation processes in the general phenomenon of the sharing economy practices. Only a larger and deeper spectrum of empirical research could lead us to more accurate conclusions on this point. Moreover, this sector has just begun to be tackled by public administrations and it is too early to have longitudinal research on this subject. For these reasons, our findings are still not robust enough. However, these cases allow us to provide an overdue framework of analysis to study these questions for the time being. The dynamics of sharing, trust and integration detected in our cases show the potential of sharing practices to contaminate the policy-makers in their own collaborative approach. The political investment in the Milan case is the activating ingredient for a new season of participation, not only for its concreteness but also for its capacity to create a narrative of sharing economy and a narrative for the under-developed potential of the city. However, the municipal role is insufficient without the presence of an active civil society and the presence of social innovators. Moreover, the Mantua experience demonstrates the difference between short-term investment and medium-range activities. It is probably not possible for sharing practices to blossom in a void and the presence of a rich ‘soil’ is important. However, sharing practices can survive in the absence of rather than with the retrenchment of public investment. What other factors are at play in this context?

The final set of reflections concerns the external and internal validity of the results issued by this paper. As in most qualitative research, the level of idiosyncrasy connected to the cases is quite large and thus caution should be employed in generalizing our findings to the overall practices in Italy. We believe that context plays a major role, as well as external factors and the specific moment at which we studied our cases. But at the same time, the fact that the framework of analysis used to study and understand local governance practices is also capable of providing coherent findings in this field is already a general result per se.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2019.12

Financial support

The research received no grants from public, commercial or non-profit funding agency.