Introduction

The 2019 European election in the UK was significant in a number of respects. It was the election that was not supposed to take place, held at the last-minute after Theresa May was forced to request an extension to the Brexit process from the European Union (EU), and the very act of voting symbolised the travails of Britain's efforts to withdraw from the Union. It was also never going to be the most consequential election, since British Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) would not hold onto their seats for very long, meaning citizens were taking part in an election with rather insignificant consequences for their own lives. And the vote took place against the backdrop of major social and political upheaval in the UK, as the failed attempts to pass the withdrawal agreement highlighted the extent of Parliamentary deadlock as well as the continued salience of Brexit divisions among UK citizens, and led to a protracted period of crisis in the British state over how to proceed.

Unsurprisingly, Brexit dominated the election campaign, and the results indicated that parties with unambiguous positions on Brexit performed best. The Brexit Party, which favoured a no-deal Brexit, was the surprise winner of the popular vote and obtained the greatest number of MEPs, followed by the Liberal Democrats – who had campaigned on an anti-Brexit platform – in second place. The Conservatives and Labour, in contrast, were both punished by voters, and both mainstream parties saw their support decline precipitously. The Conservatives lost support among Leave supporters to the Brexit Party, many of whom had previously defected to UKIP in the 2014 European election, and lost support in affluent and Remain-supporting areas to the Liberal Democrats. Labour lost support among Remainers to both the Liberal Democrats and the Greens and from Leave-supporters to the Brexit Party. The election resulted in a decisive blow to the governing Conservatives, a significant increase in support for smaller parties with clear positions on Brexit, and a considerable decline overall in the proportion of votes going to the traditional main parties.

Both the results and the campaign in the UK suggest that European Parliament elections continue to fit the second-order contest model, which predicts that national votes lacking in salience and consequence will be marked by low turnout, declining support for the governing party, greater vote share for new and smaller parties and the dominance of national issues in the campaign. The 2019 European election exhibits all of these characteristics, with turnout systematically lower than in national elections, shrinking support for the governing Conservative party, a significant boost in the fortunes of small parties and new entrants (the Brexit Party and Liberal Democrats), and a focus on Brexit and the legitimacy of the EU rather than on European issues per se. While this follows a pattern established by the 2014 election, the salience of Brexit, the background condition of domestic political crisis and the fact British MEPs would not be sitting for long all reinforced the sense in which the 2019 election would end up looking like a proxy vote on a national issue.

The lessons for British politics from the 2019 European elections, such as they are, must be tempered by the fact that the vote accorded closely with the logic of second-order contests, although this does not mean the vote did not highlight important trends. Certainly, the victory of the Brexit Party and the Liberal Democrats does not signal any profound or long-lasting demise in the vote-share of the Conservative and Labour parties, which dominated the vote-share in the 2017 and 2019 general elections. And the Brexit Party's decline in the 2019 general election shows that the party struggles to break into Westminster and continues to rely on threatening the vote-share of other parties to influence the agenda. But the 2019 European election does exhibit well evolving trends in British politics, namely the changing politics of Brexit post-referendum – which look very different in mid-2019 than in mid-2017 – and the continuing process of political realignment which has seen Labour lose support in its industrial heartlands and the Conservatives lose support in wealthy areas in the southeast.

This article discusses these key aspects of the 2019 European elections, focusing in turn on the post-referendum context of the vote, the results of the main actors in British politics, whether the elections conform to the oft-cited second-order contest model, and the lessons that can be learned about the evolution of British politics after Brexit.

Post-referendum elections in the UK

In the few years since the June 2016 referendum in which the British electorate voted to leave the EU, UK citizens have taken part in three national-level votes: two general elections (June 2017 and December 2019) and the European Parliament elections in May 2019. Unsurprisingly, each of these votes has been heavily influenced by the result of the 2016 vote, even if indirectly. The then prime minister David Cameron had intended the referendum as a means of managing divisions on the Europe question within the Conservative party (Copsey and Haughton, Reference Copsey and Haughton2014). Following the victory of the Leave campaign, Cameron's replacement as leader, Theresa May, vowed that her government would act on the Brexit mandate and that the UK would indeed leave the EU as promised (Allen, Reference Allen2018: 107). Concerned, however, about conducting negotiations with the small parliamentary majority she had inherited from Cameron, and buoyed by poll ratings which showed her a popular leader, May called a general election on 8 June 2017. May hoped the election would increase her leverage vis-à-vis the EU as well as her domestic detractors, but instead the vote resulted – after a disastrous campaign – in the loss of the Conservatives' parliamentary majority. While both mainstream parties performed well relative to smaller parties, the anticipated Conservative vote failed to materialise, forcing May into a confidence-and-supply arrangement with the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), a small, territorially-based party from Northern Ireland which had supported Brexit and was associated with a socially conservative agenda and a desire to keep Northern Ireland in lock-step with the UK. The 2017 general election left its mark on May's tenure and her conduct of the Brexit negotiations. Without a parliamentary majority, the EU did not trust May could deliver the support at home for any agreement. Moreover, her reliance on the DUP pushed Brexit in a politically problematic direction, since the party would not countenance any special status for Northern Ireland. Defectors from within her own party, smelling blood, stepped up their criticism of the prime minister.

In the end, May's failure to pass the negotiated Withdrawal Agreement on two successive occasions in early 2019 (15 January and 12 March) forced the prime minister to request from the European Council an extension to the 2-year timeframe specified by Article 50 for negotiating an agreement on the terms of British withdrawal. The extension, offered up to 31 October 2019, was a compromise from Brussels and came at the price of British participation in the upcoming elections to the European Parliament, scheduled for May 2019. Thus, against the backdrop of a domestic crisis which occasioned the three-time failure of the Withdrawal Agreement, on 23 May British citizens took part in elections for the European Parliament. The election was symbolic in two respects. First, its effects would not last long, since British MEPs would lose their role upon the completion of Brexit. And second, the election was not supposed to have taken place, given May had promised to complete Brexit by 31 March 2019. To call the resulting Conservative performance disastrous would be an understatement: The party polled 8.8% of the popular vote – a historic low even by the standards of European Parliament elections – losing out to the newly-founded Brexit party and the pro-Remain Liberal Democrats. The Labour party performed poorly too, on 13.6% of the vote, just above the Greens. Not only did the results cast May in poor light as a leader, they also showed that the party was still highly vulnerable on the right, given the success of the Brexit Party and its programme of opposition to May's agreement. With last-minute efforts to reach across the parliamentary divide rebuffed, May was forced to concede that she was unable to deliver Brexit, and agreed to step down as leader once a successor had been chosen.

The incoming prime minister, Boris Johnson, had been widely tipped as future Conservative leader and had contributed in no small part to May's downfall through his opposition to the negotiated agreement. After seeing off contenders in a party leadership election, in which the candidates vied to portray themselves in as Eurosceptic a light as possible, Johnson set about renegotiating the terms of the Withdrawal Agreement. Johnson received few concessions from the EU, but did succeed in obtaining Brussels' support for revised customs arrangements for Northern Ireland, and unilaterally removed the ‘level playing field’ requirements from the appended Political Declaration. Whether because the deal was better, or because the Eurosceptic critics had been brought into the tent, Johnson succeeded in October 2019 in passing the Withdrawal Agreement but failed to obtain parliamentary support for his proposed timeframe (The Guardian, 2019b). Seeking to improve his situation in parliament, and capitalise on his approval ratings, Johnson called for a general election, which took place on 12 December 2019, with the Conservatives running on the slogan ‘Get Brexit Done’ and with Johnson having removed the whip from outspoken pro-Remain Conservative MPs (Alexandre-Collier, Reference Alexandre-Collier2020). The election resulted in a decisive win for the Conservative party, which obtained a majority of 80 seats, many of which it won from working-class Labour constituencies – the so-called ‘red wall’ – which had previously been considered safe (Curtice, Reference Curtice2020). Labour performed poorly compared to 2017, with critics blaming their disassociation from their working-class base and confusion surrounding their message on Brexit (Cutts et al., Reference Cutts, Goodwin, Heath and Surridge2020). Anticipated gains for the Liberal Democrats also failed to materialise, while the Brexit Party saw its support drain away to the Conservatives, though the party chose not to stand against defending Conservative MPs (Sloman, Reference Sloman2020: 35). Key to the Conservatives' victory was uniting the Leave vote, with three in four Leavers voting Conservative compared to the plurality of Remainers who opted for Labour (Curtice, Reference Curtice2020: 11). The vote paved the way for the relatively smooth passage of the Withdrawal Agreement in Parliament in December 2019 and for the UK to leave the EU on 31 January 2020.

The 2019 European parliament election in the UK

The European Parliament election cannot be understood outside of the immediate context of Brexit, which can explain why the UK was taking part, motivated the emergence of the Brexit Party, determined to a considerable extent the pattern of voting, and – in turn – went on to influence the outcome of the Brexit process. This section considers the results of the vote in more detail, with subsequent sections comparing the results to those of the two post-Brexit general elections and assessing the lessons for British politics which emerge in light of this comparison.

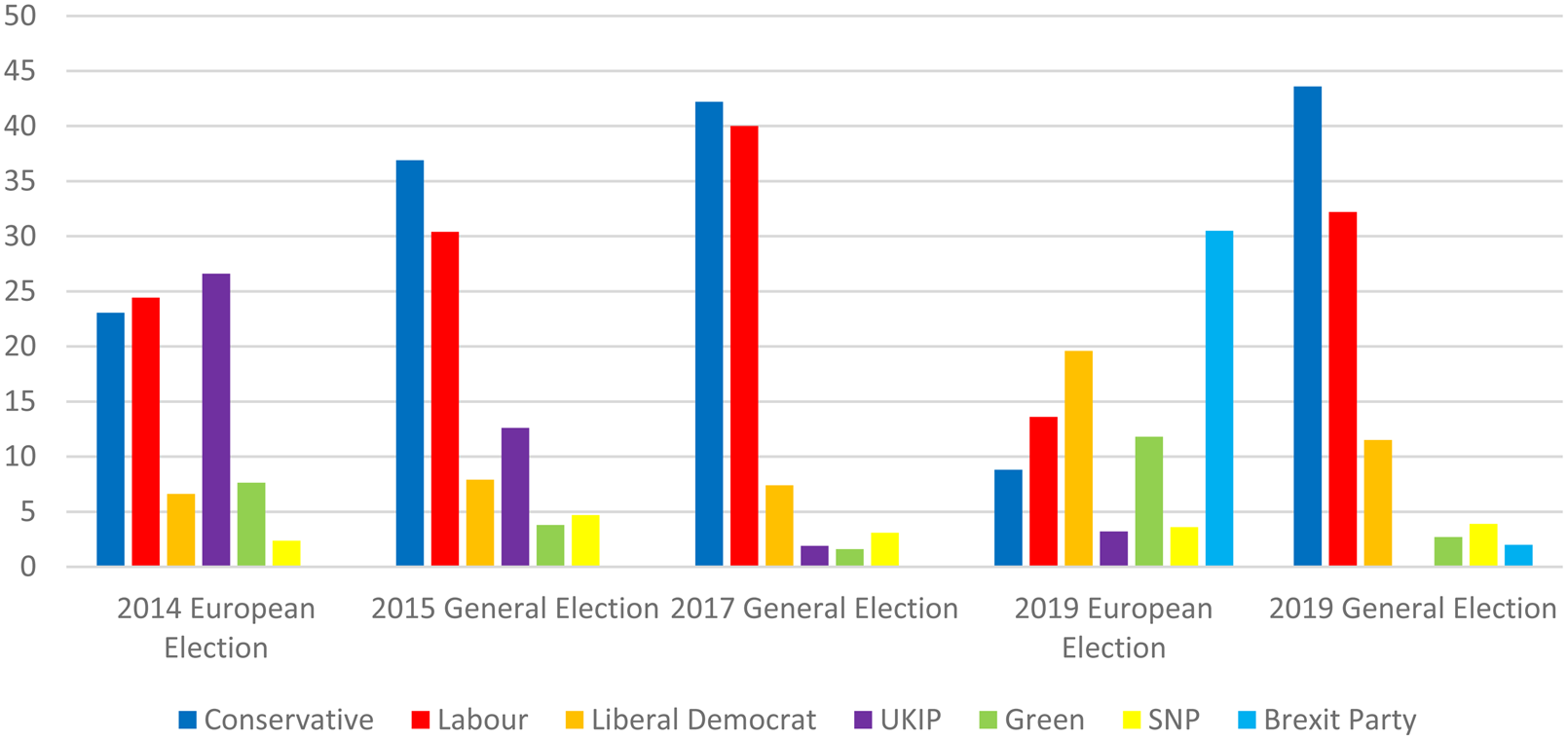

The results of the European Parliament election were a surprise for many, even at a time in British politics where seemingly long-held trends had been overturned with relative ease. The newly-founded Brexit Party received a plurality of the vote with 30.5%, followed by the Liberal Democrats on 19.6%, the opposition Labour Party with 13.6%, the Greens on 11.8%, and the governing Conservatives with 8.8% (Cutts et al., Reference Cutts, Goodwin, Heath and Milazzo2019: 497) (see Figure 1). By way of comparison with the previous European Parliament election, the Brexit Party performed somewhat better than UKIP had in 2014 (both served as similar vehicles for Eurosceptic protest) while both Labour and the Conservatives fared far worse. In 2014 UKIP had received 26.6% of the vote, whereas the Brexit Party in 2019 gained 30.5%. Meanwhile, Labour and the Conservatives had, between them, obtained 47.5% of the vote in 2014, with this figure reduced to 22.4% by 2019, a decline of over 50% of the 2014 vote. The Liberal Democrats (on 19.6%) and the Greens (on 11.8%) also performed well, especially relative to their vote-shares in previous elections, while the SNP (on 2.6%) obtained a similar share of the vote to its performance in 2017, down somewhat from the impressive performance at the 2015 general election (Agnew, Reference Agnew2018; Curtice, Reference Curtice2018).

Figure 1. Proportion of the popular vote received by parties in the UK in national and European elections, 2014-19 (Data from Electoral Commission (2019a, 2019b, 2019c) and Cutts et al. (Reference Cutts, Goodwin, Heath and Milazzo2019).

The Conservatives deliberately chose not to campaign whole-heartedly, aware that the election highlighted their failure to deliver Brexit as promised, and the party's vote share of 8.8% was the lowest it had ever polled in a national election (Curtice, Reference Curtice2019). According to polling by Ashcroft, Conservative support was fairly equally split between Leave and Remain supporters. The same study suggests that over half of voters (53%) in the European Parliament election who had voted for the Conservatives in June 2017 defected to the Brexit Party (Ashcroft, Reference Ashcroft2019). By early-2019 it had become clear to many Eurosceptics that May's vision for the UK's post-Brexit relationship with the EU – enshrined in her failed Withdrawal Agreement and the ‘Chequers Proposal’ – was not as strident as the prime minister's Eurosceptic rhetoric had made out (Brusenbauch Meislova, Reference Brusenbauch Meislova2019). Brexit Party supporters, who were by mid-2019 far more supportive of ‘no deal’ than previously (Kettell and Kerr, Reference Kettell and Kerrforthcoming) clearly did not find it an attractive proposition to support May's agreement, which had been negotiated with the EU under an intense asymmetry in bargaining power (Hix, Reference Hix2018; Martill and Staiger, Reference Martill and Staigerforthcoming). The party also lost a smaller proportion of their support (12%) to the Liberal Democrats. According to Cutts et al. (Reference Cutts, Goodwin, Heath and Milazzo2019: 513) it is the defection of Remain-supporting former Conservative voters to the Liberal Democrats, especially in affluent areas in the southeast, which decimated the Conservative vote-share compared to the 2014 European election since Eurosceptic Conservatives had already defected (to UKIP) in 2014. The Conservatives' poor showing resulted from the fact that having failed to convince former UKIP voters to support the party, they had alienated affluent pro-Remain supporters in the process, many of whom switched to the Liberal Democrats (Cutts et al., Reference Cutts, Goodwin, Heath and Milazzo2019: 513).

Labour also performed poorly in May 2019 relative to its vote-share in the 2017 general election and its performance in the 2014 European Parliament election, receiving just 13.6% of the vote, compared to 24.4% in 2014. The party's campaign focused on the need for greater public investment and effort to tackle inequalities and combat climate change (BBC News, 2019b) and it did its best to direct the discussion away from Brexit, on which the party was highly divided: At the end of April the conflict came to a head, and the party agreed to support a second referendum ‘with caveats’ (BBC News, 2019a), but deliberately avoided making this the cornerstone of their campaign. ‘Strategic ambiguity’ had arguably helped the party to achieve a substantial – if insufficient – the share of the vote in the 2017 general election, but by the time of the European elections the party was finding it more difficult to appease both sides of the debate (Cutts et al., Reference Cutts, Goodwin, Heath and Milazzo2019: 509). Squaring the Brexit circle was especially difficult for Labour since over two-thirds of their support came from Remainers (Ashcroft, Reference Ashcroft2019; Lynch and Whitaker, Reference Lynch and Whitaker2018) but a majority of seats they held were in areas which voted to Leave (estimated at 64% of the party's seats held prior to the 2017 general election) (Hanretty, Reference Hanretty2017: 477). The difficulties associated with Labour's Brexit position meant the party lost Leave-supporting voters to the Brexit Party, especially in areas where fewer voters held higher educational qualifications, but also that it failed to hold onto some of the gains it had made among younger voters in the 2017 general election, many of whom in Remain-supporting constituencies switched to the Liberal Democrats (Cutts et al., Reference Cutts, Goodwin, Heath and Milazzo2019: 509, 512). According to the Ashcroft poll, 22% of Labour voters in the 2017 general election opted for the Liberal Democrats in May 2019, 17% voted for the Greens, and 13% defected to the Brexit Party (Ashcroft, Reference Ashcroft2019).

Nigel Farage's Brexit Party was the greatest beneficiary of the elections, receiving a plurality of votes (30.5%), making them the winner by a considerable margin. The party had been formed only in November 2018 and so fresh was the outfit that it did not have a manifesto prepared in time for the elections, running instead on the promise of a Brexit on ‘WTO terms’ (that is, essentially, a ‘no deal’ scenario). The party aimed to capitalise on May's seeming inability to deliver Brexit, as well as hardening anti-EU sentiment among Leavers (Staiger et al., Reference Staiger, Pagel and Cooper2019), many of whom regarded Brussels as deploying bullying tactics in the negotiations. Indeed, polls showed that the party obtained over half (64%) of the Leave vote, whereas the Remain vote had been far more fragmented. Unsurprisingly, a significant majority of those voting for the party (91%) had voted Leave in the referendum (Ashcroft, Reference Ashcroft2019). The Brexit Party targeted regions where UKIP had been successful before, and according to district-level data performed strongly in areas where support for Brexit was high, including in eastern England, the East Midlands, and Wales, and performed poorly in London and Scotland, where it received on average under 20% of the vote (Cutts et al., Reference Cutts, Goodwin, Heath and Milazzo2019: 500–501). The party drew considerable support among Leavers away from both the Conservatives and Labour, although there was a strong correlation between those who had supported UKIP in 2014 and those who voted for the Brexit Party in 2019, meaning the party did not win over many Conservatives who had not previously defected (Cutts et al., Reference Cutts, Goodwin, Heath and Milazzo2019: 505). Of the total, 67% of Brexit Party voters in May 2019 indicated they had voted Conservative in the June 2017 general election, and 14% said they had voted Labour (Ashcroft, Reference Ashcroft2019).

The main loser on the right was UKIP, led by Gerard Batten, which obtained 3.3% of the vote, receiving no MEPs. Since the referendum vote, the party had lost much of its raison d'etre, as the single issue on which it was campaigning had been decided, its enigmatic leader had departed, and the Conservatives under May had adopted a more Eurosceptic cadence (Evans and Mellon, Reference Evans and Mellon2019: 84). The result was that ‘the decision to leave the EU had shot UKIP's fox’ (Cowley and Kavanagh, Reference Cowley, Kavanagh, Cowley and Kavanagh2018: 424). While subsequently, Farage's Brexit Party appeared well placed to capitalise on opposition to May's deal, by this point UKIP had become a more socially conservative and, according to some observers, anti-Islamic party. Interestingly, and perhaps because of this shift to the socially-conservative right, much of the UKIP vote in May 2019 was new, with the majority of UKIP voters from 2017 (68%) having defected to the Brexit Party, and only 32% of UKIP voters in May 2019 having voted for the same party in the 2017 general election (Ashcroft, Reference Ashcroft2019).

The second-largest number of MEPs was gained by the Liberal Democrats – ‘a party with a commitment to the EU in its DNA’ (Oliver, Reference Oliver2015: 414) – which campaigned on an explicitly anti-Brexit platform and supported a ‘People's Vote’ – a second referendum. The party obtained 19.6% of the popular vote, polling around two-thirds of the level of Brexit Party support, representing an increase of 13 percentage points on its performance in the previous European elections (6.61%) and around 12 percentage points on its performance in the last general election (7.4%). The vast majority of Liberal Democrat voters (88%) had voted to Remain in the 2016 referendum, and the party obtained the support of 36% of those who had voted Remain in 2016, although this vote was more fragmented than the Leave vote, with a considerable proportion also voting Labour (19%) and Green (19%) (Ashcroft, Reference Ashcroft2019). The party performed well in affluent areas of the southeast of England, where there was strong support for Remain in the referendum, including in the south-west of London (where the party had traditionally performed well), taking votes from the Conservatives in these areas in particular. Correspondingly, the party performed poorly in the West Midlands and eastern England, where support for Brexit was higher (Cutts et al., Reference Cutts, Goodwin, Heath and Milazzo2019: 501). The party's stance on Brexit drew in supporters from both Labour and the Conservatives who were disenchanted by the policies of these parties, which were both officially pro-Brexit and also much more ambiguous (Sloman, Reference Sloman2020: 39). The party also benefited from its pre-existing support in affluent pro-Remain areas, a tradition of strong grass-roots organisation, and by the fact it was no longer associated with the baggage of governing, as it had been in the 2015 general election.

The Greens – co-led by Jonathan Bartley and Sian Berry in the campaign – polled well (11.8%), especially in Remain-supporting areas (Cutts et al., Reference Cutts, Goodwin, Heath and Milazzo2019: 501), and increased their vote share by just over four percentage points, although the Liberal Democrats achieved almost double the Greens' vote share, in contrast to 2014 when the Greens had narrowly edged out the (then governing) Liberal Democrats. The Greens polled especially well in majority Remain-supporting areas in the south-west and performed poorly in Leave-supporting regions on the east coast (Cutts et al., Reference Cutts, Goodwin, Heath and Milazzo2019: 501). Almost half of the Greens' vote-share (48%) came from those who had voted Labour in June 2017, and a significant majority (78%) had voted Remain in 2016 (Ashcroft, Reference Ashcroft2019). The other party seeking to capitalise on the votes of Remain supporters, Change UK – founded by ten Labour and three Conservative party-refugees – performed poorly and received no seats. Among other reasons, the party suffered from poor branding and frequent changes of name even in the run-up to the election, the absence of a significant organisational basis, no history of prior identification with voters (which the Brexit Party lacked also, but Farage himself did not), numerous competitors for Remain votes with clearer Brexit positions, and the association of its key personalities with mainstream parties which also performed poorly.

Still a second-order national contest?

Placing the 2019 election in context and comparing the results with both the 2014 European Parliament election and the two most recent general elections (2017 and 2019) can help us to understand the place of European elections within the UK and, most importantly, whether they still fit the model of second-order national contests.

Second-order contest theory posits that sub-national and trans-national elections are often qualitatively different from national elections – which ‘decide who is in power and what policies are pursued’ – because there is less at stake for citizens in the vote (Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2005: 651), meaning voters tend to use such occasions to punish their governing parties on national issues (Reif and Schmitt, Reference Reif and Schmitt1980). Second-order contests are thus distinct in a number of respects: turnout tends to be far lower than at national elections, the governing party usually loses support relative to previous (and successive) national elections, contests tend to be fought on national issues rather than local or European ones, and larger parties generally lose out to smaller or newer competitors. Over the years successive studies have claimed that European Parliament elections fit the second-order contest model well (Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2005; Hix and Marsh, Reference Hix and Marsh2011), with low turnout, a missing link between the election and executive control, domestic issues dominating in the campaigns and evidence of anti-incumbent voting patterns offered as reasons (Corbett, Reference Corbett2014: 1194). Even as the Parliament has become a more significant institution within the Union, and as the set of EU competences has expanded, European Parliament elections still seem to accord with this model (Marsh, Reference Marsh1998; Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2005: 668), although there is some evidence this might be changing as the link between citizens and the EU becomes more politicised (e.g. Corbett, Reference Corbett2014; Galpin and Trenz, Reference Galpin and Trenz2019).

Do the results of the 2019 European election in the UK accord with the expectations of second-order contest theory? The question is an important one, since it helps us understand whether the election fits the pattern of prevailing European Parliament elections, whether these elections are themselves the subject of qualitative change – as some authors have argued – and, finally, how relevant the 2019 European election in the UK is as an indicator of change in British politics. The remainder of this section examines this claim in relation to the scholarly criteria used to establish whether an election can be considered a second-order contest. It suggests that, despite a few minor deviations from the mould, the 2019 European Parliament election fits the definition of a second-order contest reasonably accurately.

One key indicator of second-order status is that turnout tends to be lower than in national elections (Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2005: 651). Because the elections do not result in the formation of any government, they are considered less important than national elections (Hix and Marsh, Reference Hix and Marsh2011: 5). Certainly, this appears to have been the case with the 2019 European Parliament election. According to polling by Ipsos Mori (2019), while 86% of respondents surveyed prior to the 2017 general election said the result was either ‘very important’ or ‘fairly important’, only 61% of respondents said this was the case for the 2019 European election. Turnout was correspondingly low at 37%, though not unprecedentedly so. Indeed, this figure was similar to turnout in the 2014 European Parliament election (35.6%) but lower than in national elections held in 2015 (66.9%), 2017 (69.3%), and 2019 (67.3%). It was also far lower than the figure for the 2016 referendum which had witnessed such high turnout (72.2%) that much of the polling data were inaccurate as a result. As Figure 2 makes clear, turnout in European Parliament elections remains systematically lower than in national votes. This is in spite of the salience of Brexit in British politics at the time and widely-held claims that the vote would amount to a second referendum on the Brexit issue (The Guardian, 2019a). If this was to be a proxy referendum, it was not one being held on the same terms – or with the same electorate – as in 2016. Moreover, turnout was skewed towards Remain supporters, who, keen to have their say, voted in larger numbers than Leave-supporters, who felt disenchanted and were tired of voting repeatedly for the Brexit option (Cutts et al., Reference Cutts, Goodwin, Heath and Milazzo2019: 502–503).

Figure 2. Turnout (%) in national elections and referendums in the UK, 2014-19 (Data from Electoral Commission (2019b, 2019c) and Cutts et al. (Reference Cutts, Goodwin, Heath and Milazzo2019).

Another criterion of second-order contests is that governing parties tend to perform poorly, since ‘voters use [them] as a low-cost opportunity to voice their dissatisfaction with government parties’, meaning they are prone to decrease their support in the second-order contest but subsequently regain this in the subsequent first-order election (Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2005: 651). Instead, voters are more likely to ‘support opposition, small and new parties to the detriment of parties in national government’ when voting in second-order contests (Schakel, Reference Schakel2015: 636). Generally speaking, the results of the 2019 European election, especially in the context of the 2017 and 2019 general elections, support this hypothesis. The ruling Conservatives received a moderate share of the vote in June 2017, declined precipitously in May 2019 in the European election, and subsequently increased their vote share in December 2019, such that they could obtain a sizable majority in the latter election. Two caveats are worth noting here, however. The first is that the Conservatives fought the 2019 general election on a more Eurosceptic platform under Johnson than May had fought the previous election, suggesting the vote was not a like-for-like comparison. The second is that voters deserted both major parties in May 2019 and the Labour opposition did not accrue support from the voters' decision to punish the Conservatives. These caveats do not disprove the hypothesis that the governing party was punished, but suggest there was more to the result than simply a desire to punish the Conservatives for poor governance.

A related aspect of second-order contests – which may help explain this – is that larger parties tend to poll poorly relative to their size, and ‘small parties do relatively better compared to first-order election results’ (Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2005: 652). A related claim has it that new parties, rather than simply smaller ones, are likely to poll better (Schakel, Reference Schakel2015: 636).Footnote 1 In the UK case, this is reinforced by the significant divergence in proportionality between the First Past the Post (FPTP) electoral system used in elections to Westminster and the closed-list proportional system used in European Parliament elections, which encourages citizens to vote for smaller parties. The results of the 2019 European Parliament election would seem to support this claim. Both of the main beneficiaries of the vote were small parties relative to the number of seats they held in the British Parliament: Eight seats for the Liberal Democrats and no seats for the Brexit Party. The Greens also polled well for a party with only one MP in Westminster. While the Liberal Democrats are an established small party (with roots dating back to the Liberal Party of the 19th century) and while the Greens trace their history to the environmental movements of the 1970s, the Brexit Party had been in existence as a formal entity only since November 2018. Given the scale of the collapse in Labour's vote share in addition to the Conservatives, it is perhaps more plausible to see in the 2019 European election mainstream decline rather than punishment of the governing party per se.

Finally, it is claimed that European elections are second-order because they are fought on domestic issues, where ‘the situation in the first-order arena, that is, the national arena, determines EP elections’ (Adam and Maier, Reference Adam and Maier2011: 434). They are ‘fought in the shadow of the contest for the main (first-order) national election by the same parties as contest national elections, with a subsequent focus on the national arena rather than European level issues’ (Hix and Marsh, Reference Hix and Marsh2011: 5). Here the record is more complex, but generally still accords with sceptical accounts of the efficacy of European elections. The campaign in the UK was dominated by Brexit, although some parties – notably Labour – tried to steer the conversation towards other domestic issues where they felt more comfortable. While Brexit made the EU the subject of the election, however, this did not translate into any sustained discussion of the EU policy agenda, of the vision of the major political groupings at the EU level, or the future direction of the EU's political system. Whether the focus on the EU was derivative of domestic preoccupations with Brexit and the EU (e.g. De Vries et al., Reference De Vries, Van der Brug, Van Egmond and Van der Eijk2011: 17; Hix and Marsh, Reference Hix and Marsh2011: 5) or was part of a broader shift towards European Parliament elections as ‘first order polity elections’ where the EU's legitimacy is itself the subject (Galpin and Trenz, Reference Galpin and Trenz2019) is academic in the UK context since the root cause – British Euroscepticism and the Brexit vote – was essentially the same. Whether or not we regard the 2019 European election in the UK as a first-order contest over EU legitimacy or a second-order contest deriving from the salience of this question in British politics, we are forced to accept that the focus on ‘Europe’ as an issue does not equate to the emergence of genuine contestation over the direction of the EU agenda, but rather derives from the salience of the EU membership question in the UK.

In a number of respects, then, the 2019 European Parliament election results confirm the expectations of second-order contest theory; turnout remains lower than in national elections, the governing party received a significant (but temporary) decline in support, larger and more traditional parties lost out to smaller and newer competitors, and engagement with European issues was thin on the ground, even though the question of Britain's EU membership dominated the campaign. Of course, the correspondence between the 2019 European election and the assumptions of second-order contest theory leaves some questions unanswered. It is not clear, for instance, whether the Conservative party's significant losses were a product of desires to punish the governing party or whether they were part of the broader decline of the political mainstream. It is also unclear whether voters were seeking to punish established parties for their positions on Brexit (with a view to supporting them subsequently) or whether they simply preferred alternative parties from a programmatic point of view. And, as always with UK elections to the European Parliament, it is unclear how much of the variation in vote share between the major parties iwas a product of the second-order nature of the election or the use of an electoral system which produces such distinct results to that used for elections to Westminster.

The distinct circumstances surrounding the vote in 2019 likely reinforced the odds it would approximate a second-order contest. To begin with, there was far less at stake than usual, since elected British MEPs would not sit for the duration of the 2019–24 Parliament and would – it was believed at the time – be out in any case by October, prior to the inception of the new Commission. (In the end, British MEPs sat until 31 January 2020). Moreover, the election took place against the backdrop of a national crisis precipitated, in no small part, by the governing Conservative party, as May's efforts to pass her negotiated Withdrawal Agreement failed in the British Parliament – a record defeat – and it appeared there was no simple way out of the impasse. Then there was the symbolic content of the election for both Remain and Leave supporters. Many of the former had been agitating for a second referendum in order to voice their displeasure over the government's Brexit course, and the European elections provided an important avenue for this. Leave supporters, meanwhile, regarded the fact the election itself was having to take place as an affront, making a protest vote more likely. Finally, one might point to the clarity of positions on Brexit offered by small and challenger parties – in this case the Brexit Party and Liberal Democrat positions – when compared with the confusion of mainstream (Conservative and Labour) positions as a facilitating condition for mainstream decline. In short, the 2019 European elections were especially prone to being treated by voters as a second-order contest.

The European election and British politics

Understanding the 2019 European election in the UK as redolent of second-order election theory helps us to place the election in context and to understand its significance (or, to some extent, its non-significance) as a forebearer of future trends in British politics. Broadly speaking the lesson to be drawn from the largely second-order nature of this election is to moderate the implications for British politics that we can draw from this example, since many of the ostensibly surprising trends are entirely predictable according to the logic of second-order theory, and most of the observed changes did not outlast the subsequent first-order election in December 2019. Four supposed trends are worth revisiting in light of the 2019 European election and our knowledge of how the results differed from the general elections in June 2017 and December 2019: (a) the demise of multi-party politics, (b) the salience of Brexit, (c) the rise of populism, and (d) the change in political alignments.

Can the May 2019 election tell us anything about changes in the British party system? One discernible finding from the 2017 general election, according to a number of analysts, was a reversal of the trend towards a more diffuse party-system in the UK, given the strong performance of the Conservatives and Labour and the weaker polling of the SNP, UKIP and Liberal Democrats relative to previous elections (Curtice, Reference Curtice2017; Heath and Goodwin, Reference Heath and Goodwin2017; Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Manley, Pattie and Jones2018: 179; Prosser, Reference Prosser2018). Yet come the May 2019 European election the Liberal Democrats polled extraordinarily well, as indeed did the Brexit party, and both larger parties lost out, leading to some expectations among politicians that the mainstream parties might not fare as well as in 2019 as they had in 2017 (Sloman, Reference Sloman2020: 40). In line with the expectations of second-order theory, however, the December 2019 results proved a boon for the governing Conservative party, while Labour increased its vote share significantly relative to the May 2019 European Parliament election (though declined relative to the 2017 general election). The vote-share of the two main parties, at 75.8%, was not significantly below the 82.2% figure from 2017. The SNP also performed well within Scotland, but their vote share remains small and geographically concentrated on a number of marginal constituencies. Liberal Democrat gains were not forthcoming, and the party kept the same number of seats, though it did draw some support away from Labour (Curtice, Reference Curtice2020: 11).Footnote 2 Comparing the European election to the general elections suggests that the major parties appear to have, by and large, maintained their grip on the UK party system, even as their smaller competitors have sought to capitalise on the salience of Brexit and the difficulties the major parties have faced in articulating coherent positions. In short, the 2019 European election does not herald a return to multiparty politics but is better understood as a typical second-order protest vote.

Then there are the politics of Brexit. After the referendum, it was suggested that Brexit might fundamentally alter the fault-lines of British politics. The 2017 general election was billed as a Brexit election, but voting patterns, in the end, fell principally along socio-economic lines and parties running on pro/anti Brexit programmes fared poorly, confounding expectations (Hobolt, Reference Hobolt2018: 39).Footnote 3 Both the May 2019 and December 2019 elections saw campaigns that were far more obviously focused on Brexit than the 2017 general election, even though they were further from the referendum vote. The December 2019 general election was fought by the (victorious) Conservatives under the banner ‘Get Brexit Done’. How to explain the changing status of Brexit over time? A number of changes between 2017 and 2019 suggest themselves. First, the pursuit of Brexit had become a domestic crisis by 2019, creating space for a debate about the best way to proceed. May's interpretation of the Brexit mandate, and her strategy, were both delegitimised by early 2019. While anti-Brexit Conservatives used the 2017 election result to lobby for a softer Brexit (Cowley and Kavanagh, Reference Cowley, Kavanagh, Cowley and Kavanagh2018: 426), Leave-supporters drew the opposite lesson and augured for a tougher position under a more Eurosceptic leader. Second, preferences hardened on both sides relative to 2017; Remain-supporters called for a second referendum with increasing confidence (e.g. Bellamy, Reference Bellamy2019), while support for a ‘no deal’ Brexit gradually became the dominant position within the Leave camp (Kettell and Kerr, Reference Kettell and Kerrforthcoming; Staiger et al., Reference Staiger, Pagel and Cooper2019).Footnote 4 In the immediate aftermath of the referendum positions had, surprisingly, been more moderate: Many Leavers spoke about the benefits of the ‘Norway model’, while Remain supporters acted, on the whole, as ‘graceful losers’ (Nadeau et al., Reference Nadeau, Bélanger and Atikcanforthcoming) and Remain-mobilisation was initially low (Davidson, Reference Davidson2017). Third, political parties began to shift their own positions over the course of 2018–19: The Conservatives spoke more favourably of ‘no deal’ under Johnson, Labour flirted with the idea of a second referendum and eventually adopted it, the Brexit Party set out a harder stance than had UKIP – which had not supported a no deal Brexit – and the Liberal Democrats moved from promising a second referendum to promising a revocation of Article 50.

The 2019 European Parliament elections were also notable insofar as they signalled, for many analysts, the rise of populism as a (more) significant force in European politics (e.g. Napierala, Reference Napierala2019; Servent, Reference Servent2019; Treib, Reference Treibforthcoming). Did the ascendency of the Brexit Party in the 2019 European election in the UK herald such a rise in British politics? To be sure, within much of the pro-Brexit rhetoric could easily be found populist tropes: the construction of an undivided British ‘people’ and the identification of their ‘elitist’ enemies and external 'threats' (Freeden, Reference Freeden2016; Wilson, Reference Wilson2017). And certainly, there are linkages between Farage's brand of Euroscepticism and populism, what Tournier-Sol (Reference Tournier-Sol2015) had described as UKIP's ‘winning formula’. But the Brexit Party's success must be put into context. To begin with, the party's performance differs little from the situation in the 2009 European Parliament election in which UKIP capitalised on Eurosceptic sentiment to gain a plurality of popular support but failed to translate these gains into seats in the British Parliament. Most importantly, the Brexit Party did not keep their supporters, who voted in droves for the Conservative Party in the 2019 general election. Why they did so is overdetermined: Johnson's conservatives adopted much of their Brexit rhetoric, Farage stood down his candidates in Conservative-held seats, and the electoral system prevented the Brexit Party from translating votes into seats. Thus, the rise and fall of the Brexit Party tells us something about the surface resilience of the UK system to insurgent parties, as well as its subtler vulnerability. While these parties find it exceedingly difficult to break into Westminster, even with significant popular support, they are able to exert considerable influence by threatening the major parties' vote-share in marginal constituencies. The 2019 European election was not a turning point for populism in the UK but rather showed once again how such ideologies have gained a foothold in the system in recent years.

Finally, there is the question of political realignment in the UK, which has been a topic of sustained debate in British politics for a number of years, reflecting broader observations on the rise of new cleavages in European politics, notably between younger and older voters, and between the winners and losers from globalization (e.g. Azmanova, Reference Azmanova2011). The 2017 general election showed considerable evidence of political realignment, with the Conservative party gaining support in de-industrialised areas where Labour had previously polled well, and Labour picking up support in cosmopolitan areas ‘more strongly connected to global growth’ (Jennings and Stoker, Reference Jennings and Stoker2017: 359). Similar trends were evident in the 2019 European election, albeit occluded at times by the surge in support for the Brexit Party and the Liberal Democrats. Conservative support held up in deprived areas, but the party lost votes to the Liberal Democrats in more affluent constituencies, many Brexit Party supporters having already defected to vote UKIP (Cutts et al., Reference Cutts, Goodwin, Heath and Milazzo2019: 505–507). Labour lost support to the Brexit Party in deprived areas and among the white working class, and to other parties in areas with a younger vote (Cutts et al., Reference Cutts, Goodwin, Heath and Milazzo2019: 510). In the December 2019 general election the Conservatives managed to unite Leave voters who had voted for other parties in the European Parliament election, helping to secure their substantial victory, but again lost support to the Liberal Democrats in more affluent and Remain-supporting areas (Curtice, Reference Curtice2020: 11). The 2019 European election thus illustrates a broader pattern of realignment in which the Conservatives have occupied space in Labour's heartlands which the latter party had taken for granted for a number of years, albeit that this support mainly went to the Brexit Party in May 2019 before going over to the Conservatives in December 2019 (Cutts et al., Reference Cutts, Goodwin, Heath and Surridge2020: 8–10).

Conclusion

This article has examined the 2019 European Parliament election in the UK. The election was significant insofar as it symbolised the failure of the Brexit process to be secured by the stated deadline, saw British MEPs elected for a significantly truncated tenure, and took place against the backdrop of considerable political upheaval in the UK. The results showed that Brexit remained a key issue for voters and that mainstream parties could not be complacent: The front-runners were both parties with strong views on Brexit – the Brexit Party and the Liberal Democrats – while the Conservatives and Labour polled poorly even for a European election. The results suggest that European elections in the UK continue to fit the expectations of second-order contest theory, with low turnout, declining support for the governing Conservatives (which would later be regained), rising vote-share of smaller and newer parties, and a preoccupation with the national debate on Brexit rather than on issues at the EU level. We thus need to treat any lessons from the vote for British politics with due caution, given that the May 2019 result cannot be equated with a UK general election. While changes in the discourse surrounding Brexit and patterns of underlying political realignment are indeed suggestive of ongoing trends in British politics, the surge in support for the Brexit Party and the Liberal Democrats are better understood as products of a second-order contest rather than as decisive shifts in the UK party system.

Funding

The research received no grants from public, commercial or non-profit funding agency.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Mark Franklin, Luana Russo, Uta Staiger, the journal editors, and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments on the manuscript.