Introduction

The idea for the current study arose from observations within clinical practice of a general adult mental health team. A need was identified for an effective psychological treatment for complex presentations of personality disorders, a patient group that may be more difficult to treat because of the severity and persistence of their symptoms and the effects of the interpersonal difficulties on the therapeutic relationship (Bender et al. Reference Bender, Dolan, Skodol, Sanislow, Dyck, McGlashan, Shea, Zanarini, Oldham and Gunderson2001). This group comprises a significant proportion of service caseloads, as identified by an Irish study indicating that 40% of cases presenting with a mental health disorder also met the criteria for a co-morbid personality disorder (Carr et al. Reference Carr, Keenleyside, Fitzhenry, Harte, White, O’Hanrahan, Hayes, Cahill, Noonan, O’shea, McCullagh, McGuinness, Rodgers, Whelan, Sheppard and Browne2015). Individuals with personality disorders had higher rates of child maltreatment, poorer personal and family functioning, and a higher severity of presenting difficulties (Carr et al. Reference Carr, Keenleyside, Fitzhenry, Harte, White, O’Hanrahan, Hayes, Cahill, Noonan, O’shea, McCullagh, McGuinness, Rodgers, Whelan, Sheppard and Browne2015). This group also reported greater unmet service needs and higher motivation for psychotherapy. The authors pointed out the need for specialist evidence-based psychotherapy for individuals with personality disorders within public mental health services. Indeed, intensive psychotherapy based on a theoretical model that is structured and includes supervision for therapists is recommended as the treatment for individuals with personality disorders (NICE, 2009).

Mentalization-based treatment (MBT) is an intervention approach that has emerged from attachment and cognitive theory (Bateman & Fonagy, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2009). The treatment aims to help individuals to understand their own and other peoples’ mental states within attachment contexts and to address problems with affect, impulse regulation and interpersonal functioning (Bateman & Fonagy, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2009). In Ireland there are a small number of MBT-informed services in the Health Service Executive (HSE) West and the Irish Prison Service. The growing body of evidence for MBT mostly emanates from Europe with research from the UK, the Netherlands, Denmark, Norway and Germany comprising a recent systematic review of the literature (Vogt & Norman, Reference Vogt and Norman2018). The original studies supported the effectiveness of MBT as a treatment for adults with borderline personality disorder with gains maintained at an 18-month follow-up and 8-year follow-up (Bateman & Fonagy, Reference Bateman and Fonagy1999, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2001, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2008). Strikingly, only 14% of participants still met the diagnostic criteria for Borderline Personality Disorder, while 87% of individuals in the comparison group continued to meet criteria (Bateman & Fonagy Reference Bateman and Fonagy2008).

MBT has also been investigated in out-patient settings (Bateman & Fonagy, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2009; Jorgensen et al. Reference Jorgensen, Freudn, Boye, Jordet, Andersen and Kjolbye2012). When compared with structured clinical management, improvements in both groups across all outcome measures were seen; however, the MBT condition showed a steeper decline of difficulties (Bateman & Fonagy, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2009). Recent studies have compared the effectiveness of MBT with other psychotherapy treatments in both a day hospital setting (Bales et al. Reference Bales, Timman, Andrea, Busschbach, Verheul and Kamphuis2014), an out-patient setting (Jorgensen et al. Reference Jorgensen, Freudn, Boye, Jordet, Andersen and Kjolbye2012), and a mixture of day hospital and out-patient setting (Kvarstein et al. Reference Kvarstein, Pedersen, Urnes, Hummelen, Wilberg and Karterud2015). Bales et al. (Reference Bales, Timman, Andrea, Busschbach, Verheul and Kamphuis2014) directly compared MBT with a matched control group of patients receiving other specialized psychotherapeutic treatments. Individuals in both conditions improved across all outcome measures at 36 months, with the MBT group showing larger effect sizes. The possibility was noted that these differences could be explained by differing levels of treatment dosage; however, the authors also observed that the MBT group comprised of patients with higher levels of problem severity. In contrast to these results a recent study demonstrated MBT in a day hospital was not superior to specialist treatment as usual (S-TAU), tailored to the individual needs of patients and offered by an established treatment service (Laurenssen et al. Reference Laurenssen, Luyten, Kikkert, Westra, Peen, Soons, van Dam, van Broekhuyzen, Blankers, Busschbach and Dekker2018). There were however significantly higher early dropout rates in S-TAU, likely indicating MBT was a more acceptable treatment for patients.

A number of qualitative studies have been conducted, capturing service user perspectives of MBT. Themes arising from three lived experience researchers who benefited from MBT included the interaction between their inner world (mentalizing capacity) and outer world (social inclusion) (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Mutti, Springham and Xenophontes2016). Some service users highlighted that while MBT was helpful in terms of changing behaviour and emotional expression, they did not feel cured (Dyson & Brown, Reference Dyson and Brown2016). Other MBT participants perceived the group element of MBT as very challenging, viewed the development of trust as key and felt that MBT helped them to view the world more positively (O’ Lonargain et al. Reference O’Lonargain, Hodge and Line2017). Overall, it appears that service users see MBT treatment as beneficial, but also challenging and not a complete ‘cure’.

The quantitative outcome studies discussed above have all been implemented in personality disorder services with specialist teams. While Bales’ (Reference Bales, Timman, Andrea, Busschbach, Verheul and Kamphuis2014) study took place in regular clinical practice rather than under experimental conditions, it was within the context of a specialist personality disorder service. There can be difficulties with implementing an evidence-based treatment, generally generated under strict conditions, within real-world clinical conditions. This article aimed to address the feasibility of MBT for patients with personality disorder in a non-specialist setting by exploring the process of implementation from both therapist and participant perspectives.

The main objectives of this feasibility study (drawing on guidance by Orsmond & Cohn Reference Orsmond and Cohn2015) were to investigate the following questions: (1) Are service users likely to engage? (2) What are service users’ experiences of the programme? (3) What are therapists’ experiences of delivering the programme? (4) What are the direct and indirect benefits to individuals/the service?

Method

Research design

There were quantitative and qualitative components to the research design. Participants completed a battery of questionnaires upon starting the programme, at six monthly intervals throughout the programme, at the end of programme and a 9 month follow-up. Questionnaires included the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems-64, (IIP-64, Horowitz et al. Reference Horowitz, Alden, Wiggins and Pincus2000), the Work and Social Adjustment Scale, (WSAS, Mundt et al. Reference Mundt, Marks, Shear and Greist2002), the Symptom Checklist Revised – 90 (SCL-90-R, Derogatis, Reference Derogatis1994) and the Schwartz Outcome Scale-10 (SOS-10, Blais et al. Reference Blais, Lenderking, Baer, deLorell, Peets, Leahy and Burns1999). Patients also completed the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory III (MCMI-III, Millon et al. Reference Millon, Millon, Davis and Grossman2009) during the assessment and at the 9-month follow-up. In terms of qualitative data, participants completed feedback questionnaires at the end of the MBT Introductory (MBTi) Group and the end of the MBT Programme. All participants were invited to take part in a semi-structured interview at the end of the programme. Interviews were conducted by an independent psychologist in clinical training who was not involved in the programme. Thematic analysis was conducted by an external clinical psychologist, through identifying themes and sub-themes. We also aimed to capture therapist experiences of delivering the programme in order to assess its acceptability. Data were based on weekly discussions among the Consult Group between the years 2014 and 2018.

Development and implementation of the programme

An MBT Consult Group consisting of a consultant psychiatrist, principal clinical psychologist, three clinical psychologists, mental health social worker and three clinical nurse specialists met regularly to plan and guide the roll out of the MBT Programme. The process of development included establishing a reading group, securing funding for training and supervision, preparation of materials (information leaflets, etc.), recruitment, assessment, generating formulations, clinical/administrative issues and supervision (peer and external) as well as regular communication with the wider multidisciplinary team (MDT).

Referral process

Inclusion criteria were significant impairments in personality functioning as manifested by impairments in self and interpersonal functioning. Exclusion criteria were current alcohol/drug dependence, current psychotic symptoms, cognitive impairment, consistent refusal to engage with treatment care plans and risk of violence in a group situation. Patients were referred for assessment by two consultant psychiatrists within the sector. Patients were assessed using a clinical interview focusing on mentalizing capacity and the MCMI-III.

Description of programme

Service users initially attended a 12-session MBTi Group, a structured psycho-educational programme about the principles of mentalization. If appropriate, patients then went on to attend the full therapy programme, consisting of a group (75 minutes) and individual therapy (50 minutes) weekly. MBT functioned as an open, rolling group, allowing a second cohort to join the original group after 6 months (after completing an 8-week MBTi). The full programme was 27 months duration for the first cohort and 21 months duration for the second cohort. Patients were clinically reviewed by the group facilitators mid-way through and 9 months after the programme. Adherence to the MBT treatment model was monitored by videotaping sessions and reviewing them in expert, external supervision and by regular peer supervision guided by the adherence scale (Bateman & Fonagy, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2006). Patients remained part of the general adult mental health service and had access to regular psychiatric reviews, keyworker support and the acute day hospital as needed. Keyworkers were clinical nurse specialists, part of the wider MDT.

Sample

Recruitment

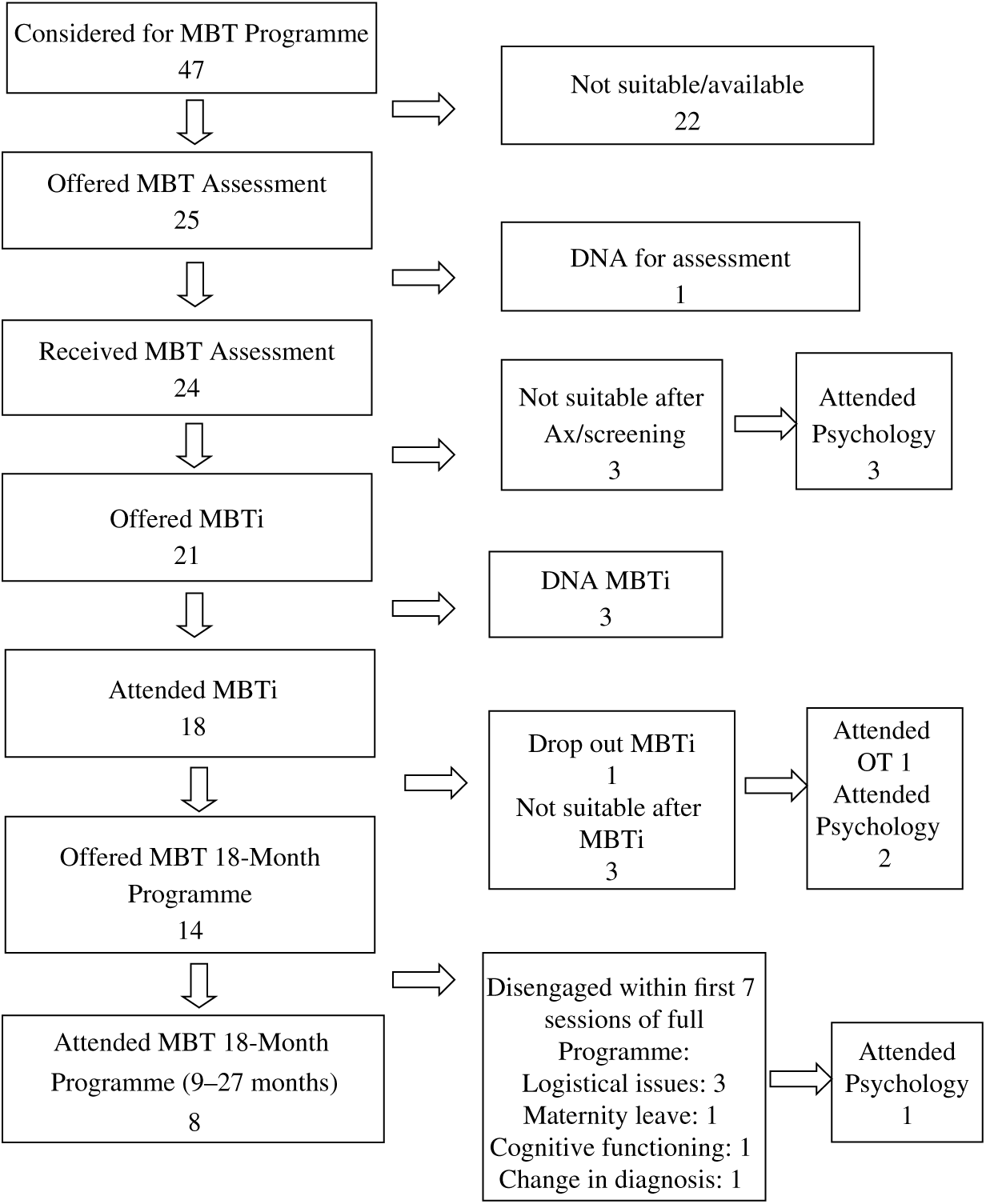

Forty-seven patients were considered for MBT, 25 were offered assessment and 24 attended for assessment (see Fig. 1). Of these 24 patients, 21 were offered a place on the MBTi and 18 attended the MBTi programme. One dropped out during MBTi due to psychological (personality) factors that interfered with their ability to use the group. Following completion of the MBTi, three patients were not offered the 18-month programme as a result of further clinical information emerging from observations in the MBTi group, that is, a change in diagnosis – severe Axis 1 disorder (1), (level of) cognitive functioning (1) and personality factors that interfered with capacity for group therapy (1). Of the 14 who started the programme, 6 disengaged within the first 7 sessions for the following reasons: being unable to commit to twice weekly sessions due to work (3), maternity leave (1) and psychological factors that interfered with ability to use group psychotherapy, that is, (level of) cognitive functioning (1) and change in diagnosis – Autism Spectrum Disorder (1). Eight participants completed at least 9 months of the full programme, with five participants completing between 21 and 27 months. Upon clinical review with the facilitators, a collaborative decision was made for three participants to finish earlier than 21 months due to a change in clinical priority (1) and not making further gains in the programme (2). For clinical reasons, there are not full data sets on these three participants.

Fig. 1. Recruitment flow diagram.

Patient characteristics

Participants were female (N = 8), with mean age of 42.25 (s.d. = 7.92; range 31–53). Six (75%) were in a relationship, and two (25%) were in employment. All participants were given a clinical diagnosis of personality dysfunction with a co-morbid disorder including anxiety/depressive disorder, PTSD and eating disorder. Seven participants (88%) had clinically significant interpersonal difficulties as assessed by the IIP-64 (Horowitz et al. Reference Horowitz, Alden, Wiggins and Pincus2000), reflected in three or more areas of difficulty, the scales most commonly endorsed being Non-Assertive (M = 75.63, s.d. = 11.01), Socially Inhibited (M = 74.50, s.d. = 12.58) and Self-Sacrificing (M = 68, s.d. = 12.64). Seven participants (88%) scored as having significant impairment on social/occupational functioning (WSAS, M = 22.88, s.d. = 10.58, range 5–35). Five (63%) met the criteria for a clinical ‘case’ on the SCL-90-R, indicating psychological symptoms and distress. Six (75%) scored within the severe distress range, with two (25%) in the moderate distress range on the SOS-10. On the MCMI-III all participants had a base rate (BR) score of >85 within at least one to five of the clinically elevated personality patterns, with the most commonly endorsed scales Dependent, Schizoid, Avoidant, Borderline, Masochistic and Depressive. All participants obtained clinically significant scores on the following clinical syndrome scales on the MCMI-III: Anxiety (M = 89.50, s.d. = 8.82), Dysthymia (M = 100.13, s.d. = 9.36) and Major Depression (M = 99, s.d. = 3.66).

Based on the group of eight participants who completed at least 9 months of the programme, the average attendance for individual therapy was 83% (ranging from 69% to 95%). Average attendance for group sessions was 81% (ranging from 61% to 97%). For the five participants who completed all time-points of research, average attendance for individual therapy was 84% (ranging from 69% to 95%). Average attendance for group sessions was 84% (ranging from 75% to 97%).

Results

Service user experiences of the intervention

We aimed to assess the acceptability of the intervention, based on evaluation of participant responses and reactions.

Quantitative data

While there were insufficient numbers in this feasibility study to run meaningful statistical analyses, the general trends showed reductions in symptomatology and interpersonal difficulties, which were maintained or continued to decrease in the 9-month follow-up period. The mean scores of programme completers (N = 5) showed trends in a positive direction in the areas of interpersonal difficulties, psychiatric symptomatology, psychological well-being, and work and social functioning (see Table 1). Figures 2–5 track the scores of each individual case across five time-points. All five participants had reductions in global level of distress (Global Severity Index, SCL-90) by the end of the programme or by follow-up (see Fig. 2). Figure 3 shows similar improvements in psychological well-being (SOS-10) by the end of the programme or by follow-up. Again, by follow-up, all were reporting better work and social functioning (WSAS, Fig. 4). By the end of MBT, three more participants were engaged in occupational activity (i.e. employment, voluntary work, college course). As illustrated in Fig. 5, all participants were reporting less interpersonal difficulties on the IIP-64 at follow-up.

Table 1. Mean scores of completers across three time-points

Time 1, start of MBT Programme; Time 2, end of MBT Programme; Time 3, 9-month follow-up; SCL90, symptom checklist 90; IIP, inventory of interpersonal problems; SOS-10, Schwartz outcome scale 10; WSAS, work and social adjustment scale.

Fig. 2. Scores (N = 5) across all five time-points on the Global Severity Index of the SCL-90. Time 1 = start of MBT Programme, Time 2 = 6 months, Time 3 = 12 months, Time 4 = end of programme (27 months for first cohort, 21 months for second cohort) and Time 5 = 9-month follow-up.

Fig. 3. Scores (N = 5) across all five time-points on the total scale of the SOS-10 (higher scores reflect higher levels of psychological well-being). Time 1 = start of MBT Programme, Time 2 = 6 months, Time 3 = 12 months, Time 4 = end of programme (27 months for first cohort, 21 months for second cohort) and Time 5 = 9-month follow-up.

Fig. 4. Scores (N = 5) across all five time-points on the WSAS. Time 1 = start of MBT Programme, Time 2 = 6 months, Time 3 = 12 months, Time 4 = end of programme (27 months for first cohort, 21 months for second cohort) and Time 5 = 9-month follow-up.

Fig. 5. Scores (N = 5) across all five time-points on the total scale of the IIP-64. Time 1 = start of MBT Programme, Time 2 = 6 months, Time 3 = 12 months, Time 4 = end of programme (27 months for first cohort, 21 months for second cohort) and Time 5 = 9-month follow-up.

Client satisfaction

Client Feedback Questionnaires were completed by participants to capture their perceptions of both the MBTi and the MBT Full Therapy Programme (n = 18). All rated the quality of the group as ‘Good’ or ‘Excellent’. All reported that they were either ‘Mostly Satisfied’ (n = 8) or ‘Very Satisfied’ (n = 10) with their MBT experience. Sixteen out of 18 (89%) said they would come back to MBT if they were seeking help again. See Table 2 for participant comments that capture particularly helpful aspects of MBTi/MBT. Suggestions for change included individual therapy to extend beyond the end of the group therapy, further review with the facilitators during the programme, the group to continue for a longer duration, and longer sessions with breaks to talk to group members informally.

Table 2. Selection of participant comments from Client Satisfaction Questionnaire

Qualitative interviews

Two of the participants agreed to take part in an individual semi-structured interview lasting approximately 60 minutes and designed to explore their therapeutic experiences. The numbers are too small to draw any strong conclusions; however, the data do help to give context to the quantitative findings. The themes related to mentalizing, treatment feedback/outcomes and group factors. One participant provided this description of mentalizing: ‘The mentalizing, it’s thinking what is the other person going through, and what is there and why might they be behaving, or saying what they are saying, rather than viewing it through my lens, and you know my filter, and that has brought, that has made an enormous difference’. Further quotes describing mentalizing of self and others are included in Table 3.

Table 3. Illustrative quotes describing participant perceptions of mentalizing and treatment feedback/outcomes

Subthemes identified within treatment feedback/outcomes were improved social functioning, improved sense of self, increased assertiveness, improved relationships, decreased loneliness, insight development and acceptance (see Table 3 for illustrative quotes). Under group factors, perceived challenges of group participation included: concern/worry about other group members, anxiety around feeling exposed by talking in front of others, the intensity of talking about raw emotions and the felt loss of the ending. Perceived helpful aspects of the group included: the meaning of the relationships as a source of support, a non-judgemental space, being on a collective journey, having similar feelings to others and the use of humour. In terms of the group facilitation a participant noted that in MBT ‘We were included, we were never treated like the patients and the facilitators, and our opinions and input was always sought’. One participant summarized their experience of mentalizing with the MBT group: ‘For me the big element was the fact of seeing other people, making the same mistakes, or demonstrating personality characteristics that were, that I would think was unreasonable (…) there would be things going through my head and I would think, how could you think that but yet I could be exactly the same and it was seeing that in people I knew were on my side (…) was the most powerful thing for me’.

Therapist experiences of the intervention

A number of observations and reflections were made by the Consult Group as detailed below:

-

Running a specialist psychotherapy service in a general adult mental health service proved challenging as it was difficult to ring-fence protected time to invest in the programme and divide the work equitably.

-

During the process of learning MBT as a new model, we noticed a natural inclination to drift back into using strategies based on our own discipline’s training or previous theoretical background when we were unsure of how to proceed in session. An awareness of this tendency and discussion of challenging events in therapy during supervision helped to maintain adherence to the MBT model.

-

Therapists and patients found the experience of being recorded strange and a little disconcerting initially with one patient preferring to sit with their back to the video; however, very quickly it became part of the routine with everyone less aware of its presence.

-

MBTi as an additional observational assessment in a group setting proved useful in making clinical decisions around suitability and readiness for intervention. It also gave participants a sense of the type of work and commitment involved.

-

It was important to maintain regular communication with the wider treating MDT in order to support patients during particular periods of challenge within their lives and within the programme.

-

We were met with the on-going challenge of recruiting sufficient numbers of suitable referrals within one sector for the sustainability of the programme. We considered the option of offering to take referrals from other teams within the area, but this raised the complex issues of clinical governance and managing extra channels of communication.

-

We identified a need for extra support for participants within their relationships with family and friends and felt that it would have been beneficial to have a component in the programme that offered support and education to significant others of the participants.

Discussion

This feasibility study documents our efforts to develop and implement an intensive specialist psychotherapy programme within the context of a general mental health service, demonstrating the real-world constraints and challenges.

Are individuals likely to engage?

Participants who disengaged from MBT did so within seven group sessions, before the individual therapy had commenced, with 50% leaving for work reasons. The prospect of starting individual therapy may have been an additional challenge. It is also possible that the individual therapy could have promoted active engagement and provided emotional containment in the initial stages, and the logistical issues could have been surmountable. Attendance rates (both individual and group) for completers of the programme reflected a very good level of engagement, suggesting that once participants settled into the programme, MBT was an acceptable intervention. Indeed Laurenssen et al. (Reference Laurenssen, Luyten, Kikkert, Westra, Peen, Soons, van Dam, van Broekhuyzen, Blankers, Busschbach and Dekker2018) found dropout rates were lower in MBT than in their comparison group receiving S-TAU.

What are service users’ experiences of the programme?

Patient satisfaction levels were found to be very high, indicating that MBT is an intervention that patients found helpful and wished to continue. However, the treatment was not without its challenges, for example, anxiety around feeling exposed at the beginning, and then the loss of the group at the end, suggesting that the start and ending of the programme are times when additional support is needed. Findings trending in a positive direction suggest that this is a beneficial treatment for patients, and that benefits were maintained 9 months after completion of the programme. Interestingly, the personal impact of MBT as perceived by participants in their qualitative accounts highlighted broader areas such as improved social functioning, sense of self, increased assertiveness, acceptance and insight, as opposed to reductions in symptomatology. Indeed the lack of emphasis on symptom amelioration is in line with the focus of recovery-based approaches which highlight the importance of connectedness, hope, identity, meaningful roles and empowerment (Mental Health Division, 2017) and meeting goals specific to the individual (Katsakou et al. Reference Katsakou, Marougka, Barnicot, Savill, White, Lockwood and Priebe2012).

What are therapists’ experiences of delivering the programme?

Overall, from the therapist perspective, MBT was a satisfying and acceptable intervention to deliver, with the majority of challenges related to systemic and organizational issues. This point needs attention, however, as the organizational context in which the programme runs has previously been found to significantly impact its outcomes. In an innovative multiple case study design, Bales et al. (Reference Bales, Timman, Luyten, Busschbach, Verheul and Hutsebaut2017) demonstrated that elements particularly at the organizational (i.e. organization support) and team (i.e. leadership) levels contributed to implementation outcome in seven programmes across the Netherlands. Treatment effect sizes greatly diminished during periods of major organizational change, with the same (adolescent) patient population in the same unit (Bales et al. Reference Bales, Verheul and Hutsebaut2017). The Netherlands is considered a well-resourced country in the management of personality disorders (Bales et al. Reference Bales, Verheul and Hutsebaut2017) and so this finding needs to be carefully considered in countries like Ireland where there is no specific strategy or specialized services for the treatment of personality disorders. Our Consult Group did grapple with organizational issues, including staff turnover and managing protected time. Although not investigated here, it is probable that these issues impacted outcomes in the programme, for example, unavailability of staff precluded starting individual therapy at the same time as group therapy. As discussed, this may have contributed to the dropout rate in the first 7 weeks of the programme.

Effective communication with the wider MDT was vital, particularly at significant transitions or developments in the group. This was also important in responding to risk disclosed within individual or group therapy and liaising with the treating consultant psychiatrist and keyworker, especially when they were not part of the MBT Consult Group.

What are the direct and indirect benefits to individuals/the service?

A useful consequence of the MBT Programme was the development of expertise within the group which led to in-depth clinical assessments and formulations being generated which informed individual care plans of patients, some of whom entered the MBT Programme and some who were offered a different therapeutic service within the MDT. The weekly discussion groups and regular supervision contributed to facilitating a mentalizing environment among Consult Group members. This impacted on interventions with patients who were part of the programme but also patients not involved in MBT highlighting an additional benefit to the wider patient group.

Implications for clinical practice

Therapist/team level

A need for very proactive efforts from therapists to help clients engage at the start and the importance of timing individual therapy to begin in conjunction with group therapy was highlighted. The programme should be well structured with patients having a clear idea of what they are committing to at the start of treatment. At the same time it needs to be flexible, adaptive and collaborative as different clinical needs or priorities can emerge for the patient. Regular individual reviews were helpful and are recommended in order to refine the formulation and refocus the treatment.

Learning a new model of therapy that differed from the prior training of each discipline meant that accessible and regular supervision was crucial. Building up confidence to make therapeutic challenges in adherence to the model was a gradual process, a task previously identified by O’Lonargain et al. (Reference O’Lonargain, Hodge and Line2017). Increased familiarity with the model helped us as a team to mentalize around our own emotional responses and complex clinical issues.

Organizational/service level

We considered what changes would be needed in the systemic/organizational context to fully integrate the programme. MBT proved to be time and resource intensive, particularly in the initial stages of development, and so support for protected time from management must be considered an essential prerequisite of running a programme. Access to suitable facilities is needed to provide a comfortable environment for therapy sessions, as well as IT and administrative support. Furthermore, timely access to a day hospital for additional support for participants was necessary, especially in the challenging early stages of treatment.

While there was a clear demand for the intervention, we encountered difficulties in recruiting sufficient numbers of individuals who would benefit from and were ready for the intervention within our sector. A solution to this would be to develop a specialized MBT service, which would accept referrals from all teams within the geographical sector. This would be in line with the Vision for Change recommendation that there should be a centralized service for individuals with personality disorder in each catchment area (Expert Group on Mental Health Policy, 2006).

Moreover, one core aspect of recovery-oriented services is that clients should have choice in accessing therapies (Mental Health Division, 2017), rather than access to a particular therapy being dependent on a person’s address. A centralized service would mean that all service users within the area have the option of accessing MBT along with other evidence-based treatments for personality disorders. Ultimately, a specialized service would enhance the quality of the treatment offered and increase confidence and competence for clinicians in working with patients struggling with complex and challenging psychological difficulties. It would be helpful to have a national strategy for the treatment of personality disorders that could guide the implementation of specialist services.

We also identified the need to develop a suite of specialist mentalization programmes, including supportive/psychoeducational interventions for family members/significant others, and MBT aimed specifically at vulnerable groups such as adolescents/young adults and parents. This would involve strengthening links with Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services.

On reflection the organizational and service-level issues which have emerged during the implementation of this MBT Programme, such as staffing, are likely common to any specialist intervention for personality disorder within a general adult mental health setting. On a therapist level, there are also particular challenges associated with implementing any new model of intensive psychological therapy within this population, requiring a determination to adhere to the specific treatment and not succumb to therapeutic drift. Specific to MBT, we as therapists had to learn to retain our own mentalizing stance not only in therapy sessions, but in our general approach to reflecting and making clinical decisions within the consult group.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include its small sample size; as this is a feasibility study, patient outcomes are not intended to be generalizable but are rather included to demonstrate outcome for a small number of patients. A significant limitation is the incomplete data sets on the three individuals who completed at least 9 months of the programme, as well as the lack of follow-up data from the three who disengaged due to logistical issues. One unresolved question is whether starting individual therapy earlier would have kept this group from dropping out or whether specific adaptations are needed to engage these individuals. In addition the evaluation was not conducted by researchers external to the programme due to time and resource constraints.

MBT aims to promote more effective mentalizing; this study lacked a measure that could accurately access this process. Future research could include the recently developed brief Reflective Functioning Questionnaire, that is, until a longer, multidimensional measure becomes available (Fonagy et al. Reference Fonagy, Luyten, Moulton-Perkins, Lee, Warren, Howard, Ghinai, Fearon and Lowyck2016). We would also recommend the inclusion of a recovery-focussed measure, so that service users can self-identify what they would view as a positive change following treatment. While service user feedback was sought throughout the process of our programme, we would envisage service users having a larger co-production role in any future programmes. A strength of the study is how it is situated within a general adult mental health setting allowing for an examination of providing specialist therapies within such a service.

Conclusion

MBT can be a challenging and yet valuable treatment for both service users and therapists. Prior to implementation of a programme, factors at the therapist, team and organizational level, as well as the wider policy and systemic context, need to be addressed to ensure there can be proper adherence to the model to achieve the positive outcomes demonstrated in the RCT studies.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to the participants, who generously took the time to share their experiences of the programme. Thank you to the other members of the Consult Group: Shirley Dolan Ruiz, Margot Ryan, Niamh Marrinan, Susan O’Brien and Patricia Ruttledge for their respective roles in implementing the MBT Programme and in supporting this research. We would like to thank Gerry Byrne for his valuable supervision and support. We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Lisa McGrath, Mairead Diviney and Philip Coey with the qualitative interviews and analysis. Thank you to the local area management team for funding the supervision.

Conflict of interest statement

Authors [DB, SM, SJ and AL] have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The authors assert that ethical approval for publication of this feasibility study has been provided by the local Hospital Ethics Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.