Introduction

Emerging adulthood, usually spanning from 18 to 25 years, is a life stage that marks the transition from adolescence to adulthood and entails significant developmental milestones for young people. Some of these milestones include engaging in identity formation, balancing family and peer influences and establishing social competences and independence (Blatt et al. Reference Blatt, Feldman, Mahler, Shulman and Cohen2005). Young adults living with a chronic health condition (CHC), either physical or mental, face the same challenges and milestones as their healthy peers, but they also have to deal with the burden of living with a CHC. Research shows that living with a CHC may impair the achievement of these milestones and result in poor quality of life outcomes (Pinquart, Reference Pinquart2014). Symptoms associated with a CHC (e.g. pain, depressed mood) impose additional constraints to young adults’ lives such as absenteeism from their studies or workplace and limitations to social life. This has been associated with loneliness and elevated levels of stress (Herts et al. Reference Herts, Wallis and Maslow2014).

Social support is an important element in the lives of young adults living with CHC because it has been associated with better quality of life outcomes (Andrinopoulos et al. Reference Andrinopoulos, Clum, Harper, Perez, Xu, Cunningham and Ellen2011; Haase et al. Reference Haase, Kintner, Robb, Stump, Monahan, Phillips, Stegenga and Burns2017). Social support is a multi-dimensional construct defined as the emotional, informational or instrumental assistance provided to an individual by others (Brownell & Shumaker, Reference Brownell and Shumaker1984; Thoits, Reference Thoits2011). Social support can be categorised into perceived and received social support, which is an important distinction regarding the measurement of the construct (Haber et al. Reference Haber, Cohen, Lucas and Baltes2007). Received social support refers to the frequency with which any aspect of social assistance is received (Dour et al. Reference Dour, Wiley, Roy-Byrne, Stein, Sullivan, Sherbourne, Bystrisky, Rose and Craske2014), while perceived support refers to an individual’s perception of received and available assistance from support network members, created by numerous experiences of support over time (Thoits, Reference Thoits2011). Perceived support has been more commonly associated with positive health outcomes in young adults living with CHC (Wodka & Barakat, Reference Wodka and Barakat2007).

The Multi-Dimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Zimet et al. Reference Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet and Farley1988) is one of the most widely used self-report measures of social support because it is brief, easy to administer and has demonstrated satisfactory psychometric qualities: good to excellent internal consistency, good test–retest reliability and construct validity (Zimet et al. Reference Zimet, Powell, Farley, Werkman and Berkoff1990). The MSPSS assesses social support from three different sources: family, friends and a significant other. Evidence from several studies supports the three-factor structure of the MSPSS across diverse clinical (e.g. Park et al. Reference Park, Park and Nguyen2012; Wongpakaran et al. Reference Wongpakaran, Wongpakaran, Sirirak, Arunpongpaisal and Zimet2018) and non-clinical populations (Osman et al. Reference Osman, Lamis, Freedenthal, Gutierrez and McNaughton-Cassill2014), including youth (Bruwer et al. Reference Bruwer, Emsley, Kidd, Lochner and Seedat2008). The MSPSS has also demonstrated good validity and reliability in patients with CHC (e.g. Naseri & Taleghani, Reference Naseri and Taleghani2012).

While a substantial number of studies validated the MSPSS in young adults typically aged from 18 to 25 years, no studies have examined the psychometric properties of the tool in young adults living with CHC. Because characteristics such as clinical status can affect factor structure, it is important to examine the factor structure in each sample within a population (Wongpakaran et al. Reference Wongpakaran, Wongpakaran, Sirirak, Arunpongpaisal and Zimet2018). Indeed, there is research evidence showing that the MSPSS has different factorial structure in different youth populations. For example, Zhang and Norvilitis (Reference Zhang and Norvilitis2002) found that the tool has a two-factor solution in Chinese young adults and a one-factor solution in North American young adults. Bruwer et al. (Reference Bruwer, Emsley, Kidd, Lochner and Seedat2008) showed that a three-factor structure of MSPSS fits well data from South African youth. Although MSPSS has been validated in different clinical and non-clinical groups, it has never been examined in emerging adults with CHCs. It is important to examine the psychometric qualities of the tool in this cohort providing evidence of its reliability and validity in assessing perceived social support, which is an important psychosocial predictor of quality of life. Hence, the aim of the present study is to examine the factor structure of the MSPSS in young adults living with CHC.

Method

Participants

Participants of this study were young adults aged 18–25 years attending Colleges of Further Education (CFE) in the Republic of Ireland and living with CHC (physical, mental or both). This study is part of the larger study conducted in Irish students in CFE. The initial sample consisted of 285 students, but only those reported living with CHC were included in the sample of the present study (n = 123, 42.7%). The majority of participants were females (73.2%, n = 90), of White Irish origin (97.6%, n = 120), and had a mean age of 20.1 years (s.d. = 2.43). Most participants reported being diagnosed with a mental health condition (41.5%, n = 51), followed by those reporting a comorbid diagnosis of both physical and mental conditions (30.9%, n = 38) and a diagnosis of a physical health condition (27.6%, n = 34).

Procedure

Data were collected online between January 2016 and June 2018. The study was advertised online and through a wide range of media. Participants were presented with a detailed information sheet about the study and then they were asked to provide their informed consent electronically in order to participate in the study. Further details on the study demographics and procedure are presented elsewhere (Nearchou et al. Reference Nearchou, Campbel, Duffy, Miriam, Neo, Petroli, Ryan, Simcox, Softas-Nall and Hennessy2019). Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee-Humanities of the University College Dublin.

Measures

Chronic health conditions

Participants were initially presented with the following definition of CHC: ‘…can be defined as long-term persistent conditions that occur at any point across life. In most cases, they can be treated but not cured and can affect one’s quality of life’ (HSE, 2008). Then participants were presented with a table listing examples of the most frequently reported physical and mental CHCs and they were asked (i) whether they have been diagnosed with one or more CHCs (ii) to indicate which conditions were those. They could either choose from a list of conditions presented and/or had the option to type in a condition that was not listed.

Social support

The MSPSS (Zimet et al. Reference Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet and Farley1988) is a 12-item self-report questionnaire that includes three subscales consisting of four items each, relating to family, friends and a significant other. Items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’, with higher scores indicating higher levels of perceived social support. The scale produces a score of perceived social support by averaging the 12 items, which ranges from 1 to 7. It also yields three separate average scores assessing social support from friends, family and a significant other, which ranges from 1 to 7, respectively.

Quality of life

Using two subscales of the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) 36-item Short Form Health Survey (Ware & Sherbourne, Reference Ware and Sherbourne2006), two dimensions of quality of life were assessed: social functioning and emotional well-being. The MOS 36-item is a widely employed tool developed to measure quality of life in individuals living with CHC. Social functioning is assessed with two items, and emotional well-being is assessed with five items. Each item is scored on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from (1) ‘all the time’ to (6) ‘none of the time’. In accordance with developers’ guidelines, items were recoded, so that all scores range from 0 to 100. The total score of each subscale is calculated by adding up all items with higher scores indicating better quality of life. Reliability coefficients showed that both social functioning (α = 0.83) and emotional well-being (α = 0.80) demonstrated very good internal consistency for the present sample.

Data analysis overview

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using principal axis factoring as the extraction method was applied to determine the factor structure of the MSPSS in young adults living with CHC. Oblique rotation was used, thus allowing factors to be correlated. The criteria used to determine the optimal number of factors to be extracted were scree plots and eigenvalue >1. Parallel analysis was also applied to further confirm the number of factors to be retained. Correlations were applied to examine the convergent validity of the MSPSS. Drawing from the social support literature, we hypothesised that the total scale and the three subscales will be positively correlated with better quality of life outcomes. Data were analysed using the SPSS software v.24, Ireland. A complete dataset was used.

Results

Exploratory factor analysis

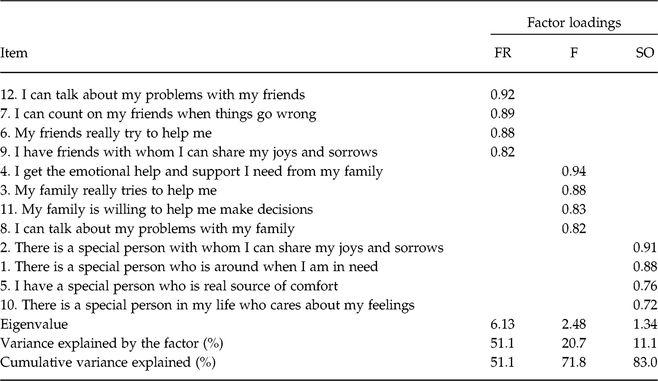

The EFA results revealed a three-factor solution of the MSPSS structure in young adults living with CHCs. The three factors explained 83% of the variance in MSPSS scores and had eigenvalues >1. The scree plot and the parallel analysis further confirmed the number of factors to be retained. All the items demonstrated high loadings on the three factors ranging from 0.72 to 0.94 (see Table 1). Means and s.d.s for all items are presented in 1 online Supplementary Material Table S1.

Table 1. Summary of the MSPSS exploratory factor analysis results (n = 123)

MSPSS, Multi-Dimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support; F, Family subscale; FR, Friends subscale; SO, Significant other subscale.

Reliability

The three subscales of the MSPSS and the total scale showed excellent internal consistency, while the corrected-item total correlations for the three subscales were >0.91 (see online Supplementary Material).

Validity

Table 2 presents the correlation matrix among all study variables as well as means and standard deviations. Significant positive correlations were evident among perceived social support from family, friends and a significant other (Table 2). Correlations revealed that MSPSS has good convergent validity. As expected, the MSPSS total scale and three subscales showed moderate positive significant correlations with social functioning and emotional well-being (Table 2).

Table 2. Means, standard deviations and bivariate correlations for all variables (n = 123)

Family, Family subscale; Friends, Friends subscale; SO, Significant other subscale; EWB, Emotional well-being subscale; SoF, Social functioning subscale; MSPSS, Multi-Dimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support.

*p < 0.001, **p < 0.01.

Discussion

The EFA findings supported the three-factor structure of the MSPSS in young adults living with CHC. All items had high loadings on the pre-defined factors indicating that the MSPSS can be used to measure perceived social support from three distinct sources in this cohort. The convergent validity of the tool was also established, as significant positive correlations were evident between the MSPSS and quality of life measures, that is, emotional well-being and social functioning. The total scale and the three subscales showed excellent internal consistency in the present sample. The findings of the present study indicate that the MSPSS is a valid and reliable tool for use in young adults living with CHC. Our study adds to a small body of research confirming the validity and reliability of the instrument with different community groups of young people (Canty-Mitchell & Zimet, Reference Canty-Mitchell and Zimet2000; Bruwer et al. Reference Bruwer, Emsley, Kidd, Lochner and Seedat2008). Consistent with some studies in youth from diverse contexts (e.g. Adamczyk, Reference Adamczyk2013), we found that MSPSS has a three-factor structure in young adults living with CHC. However, other studies in diverse cohorts of young adults showed that MSPSS has different factor solutions (e.g. Zhang & Norvilitis, Reference Zhang and Norvilitis2002). This highlights the importance of testing the factor structure of a psychometric tool across different cohorts within a population. Furthermore, because young adulthood is a significant transitional phase, marked by growing independence from family, it is imperative to be able to accurately measure social support, particularly among those with CHC for whom this transition may be more challenging.

Despite its contributions, this study has some limitations to consider. First, the sample size was relatively small based on suggestions to use large sample sizes (n > 200) in conducting factor analysis. However, MacCallum et al. (Reference MacCallum, Widaman, Zhang and Hong1999) suggested that smaller sample sizes can also be appropriate, especially when factor loadings are high. Yet, future studies can replicate our findings in larger cohorts of young adults living with CHC. Second, due to the restricted sample size, we did not test for measurement invariance regarding the type of the CHC, that is, physical or mental or both, which could have provided a greater insight on the factor structure of the tool. This can also be explored by future research.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Amelia Campbell, Katie Duffy, Miriam Fehily, Wei Lin Neo, Margareth Petroli, Holly Ryan, Sofia Softas-Nall and James Simcox for their contribution to this research.

Financial Support

This research was supported by the University College Dublin.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The study protocol was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee-Humanities of the University College Dublin.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2019.54