Introduction

Mental disorders are increasingly common among adults in both the developed and developing world and are predicted to be the leading cause of disease burden by 2030 by the WHO (Kang et al. Reference Kang, Kim, Bae, Kim, Shin, Yoon and Kim2015). These disorders are associated with increased morbidity and mortality and reduced quality of life for patients, along with escalating costs for healthcare systems (Uijen & van de Lisdonk, Reference Uijen and van de Lisdonk2008; Whiteford et al. Reference Whiteford, Degenhardt, Rehm, Baxter, Ferrari, Erskine, Charlson, Norman, Flaxman, Johns, Burstein, Murray and Vos2013; Chesney et al. Reference Chesney, Goodwin and Fazel2014; Penner-Goeke et al. Reference Penner-Goeke, Henriksen, Chateau, Latimer, Sareen and Katz2015). Multimorbidity among patients is rising substantially partly due to population ageing (Uijen & van de Lisdonk, Reference Uijen and van de Lisdonk2008; Van Oostrom et al. Reference Van Oostrom, Gijsen, Stirbu, Korevaar, Schellevis, Picavet and Hoeymans2016), including both mental and physical disorders (Kang et al. Reference Kang, Kim, Bae, Kim, Shin, Yoon and Kim2015), where the reduction in quality of life is the most significant among patients with mental and physical comorbidity (Camacho et al. Reference Camacho, Davies, Hann, Small, Bower, Chew-Graham, Baguely, Gask, Dickens, Lovell, Waheed, Gibbons and Coventry2018). While the main focus of this review is on common mental disorders, it is important to highlight the poor mortality rates in adults living with severe mental illness (SMI), with current evidence suggesting a 10–25 year reduced life expectancy in patients with severe mental health disorders such as psychosis, compared with their age-matched peers in the general population (De Hert et al. Reference De Hert, Cohen, Bobes, Cetkovich‐Bakmas, Leucht, Ndetei, Newcomer, Uwakwe, Asai, MÖLLER, Gautam, Detraux and Correll2011; Dillon et al. Reference Dillon, Hayes, Barclay and Fraser2018). This is primarily a result of the higher rates of cardiovascular, infectious and pulmonary diseases in this population (Dutta et al. Reference Dutta, Murray, Allardyce, Jones and Boydell2012).

It is recognised that many common physical conditions (including cardiovascular disease, diabetes and chronic respiratory conditions) are more common among people who also have a common mental disorder (Eaton, Reference Eaton2002; Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Edmondson and Kronish2015). For example, depression prevalence is approximately twice as high among patients with diabetes mellitus than among the general population (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Freedland, Clouse and Lustman2001). Numerous studies have also examined how common mental disorders often precede the development of chronic physical conditions. Patients with mental disorders are at an increased risk of developing diabetes mellitus compared to the general population, more likely to have established risk factors, for example, smoking (Knol et al. Reference Knol, Twisk, Beekman, Heine, Snoek and Pouwer2006; Mezuk et al. Reference Mezuk, Eaton, Albrecht and Golden2008); depression, anxiety and psychosocial stressors have been shown to increase the risk of developing subsequently cardiovascular disease (Rugulies, Reference Rugulies2002; Yusuf et al. Reference Yusuf, Hawken, ⓞunpuu, Dans, Avezum, Lanas, McQueen, Budaj, Pais, Varigos and Lisheng2004; Batelaan et al. Reference Batelaan, Seldenrijk, Bot, van Balkom and Penninx2016).

Outcomes of physical health problems are worse when comorbid with mental disorders. A number of risk factors have been attributed to this association, including reduced adherence to treatment and increased social risk factors among patients with mental disorders, for example, high rates of smoking, lower levels of physical activity and poorer dietary intake (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Edmondson and Kronish2015; Ducat et al. Reference Ducat, Philipson and Anderson2015), and among patients with SMI (Vancampfort et al. Reference Vancampfort, Stubbs, Mitchell, De Hert, Wampers, Ward, Rosenbaum and Correll2015). Patients with mental disorders are more likely to have potentially preventable hospitalisations for associated chronic physical conditions than the general population (Mai et al. Reference Mai, Holman, Sanfilippo and Emery2011). Severity of complications, along with earlier time of onset of such complications, is a feature of mental–physical comorbidity (Hermanns et al. Reference Hermanns, Caputo, Dzida, Khunti, Meneghini and Snoek2013). Life expectancy is reduced among people with a mental disorder and much of this can be attributed to increased risk of physical illness (Lawrence et al. Reference Lawrence, Hancock and Kisely2013).

Many studies have recommended targeting screening programmes, particularly in primary care, for those with diagnosed mental disorders in order to prevent the onset or reduce the progression of comorbid physical conditions (Whiteford et al. Reference Whiteford, Degenhardt, Rehm, Baxter, Ferrari, Erskine, Charlson, Norman, Flaxman, Johns, Burstein, Murray and Vos2013; Vancampfort et al. Reference Vancampfort, Correll, Galling, Probst, De Hert, Ward, Rosenbaum, Gaughran, Lally and Stubbs2016). The use of an integrated care model as an approach for this growing problem of physical and mental multimorbidity has also been advocated and is recommended by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for the treatment of depression (Kang et al. Reference Kang, Kim, Bae, Kim, Shin, Yoon and Kim2015). The benefits of integrated models of care are thought to include reduced admissions [for exacerbation and complications of chronic conditions, including diabetes mellitus, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)], reduced mortality and improved overall disease management and have additional benefits in terms of cost-effectiveness of service delivery (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Lier, Soprovich, Al Sayah, Qiu and Majumdar2016).

While studies have examined comorbidity of mental and physical health, those at primary care level and particularly in Ireland or Europe are limited (Nash et al. Reference Nash, Bracken-Scally, Smith, Higgins, Eustace-Cook, Monahan, Callaghan and Romanos2015). With primary care responsible for the management of approximately 95% of mental health problems (Klimas et al. Reference Klimas, Neary, McNicholas, Meagher and Cullen2014) and with holistic generalist care at the core of general practice delivered care, primary care and general practice are well situated to optimise identification and treatment of physical health problems among patients with mental disorders (WONCA, 2008). This scoping review aims to examine the current literature about the prevention, identification and treatment of physical problems among people with pre-existing mental health disorders in primary care in Europe and to examine interventions to address this challenge.

Methods

Scoping reviews are an increasingly popular method of reviewing research evidence allowing for examination of both the current breadth and depth of literature in addition to identifying research gaps. Furthermore, unlike systematic reviews, the quality of research is not assessed in scoping reviews, where the focus is on examination of broader topics, without limitations on the types of studies included. (Arksey & O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005; Levac et al. Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien2010). While such reviews are a relatively modern form of study without clearly defined parameters, many studies to date have utilised the methodological framework outlined by Arksey & O’Malley (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005). In this review, we adopted this five-stage framework as follows:

-

Identifying the research question

-

Identifying relevant studies

-

Selecting studies

-

Charting data

-

Collating, summarising and reporting the results.

Identifying the research question

Studies to date have examined the interplay of mental and physical health; however, to narrow the focus on the research question, this review examines physical health among patients with established mental disorders, specifically at primary care level. We were most interested in those studies that focused on patients living in the European Union and so refined the research question further to ‘Europe only’. From this focus, the following research question was formulated: ‘what is known from the existing literature about the identification and treatment of common physical problems in people with pre-existing common mental health disorders in primary care in Ireland and Europe and what can be done about this’?

Common mental disorders were defined as: depression, panic/anxiety disorder, alcohol/substance misuse, eating disorder and somatoform disorder, corresponding with those described by Spitzer et al. in ‘Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders’ (Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, Terluin, van Marwijk, van Mechelen and Stalman2009). The list of common physical disorders was generated from initial reading of the literature and includes cardiovascular disease, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, COPD and chronic pain.

Identifying relevant studies

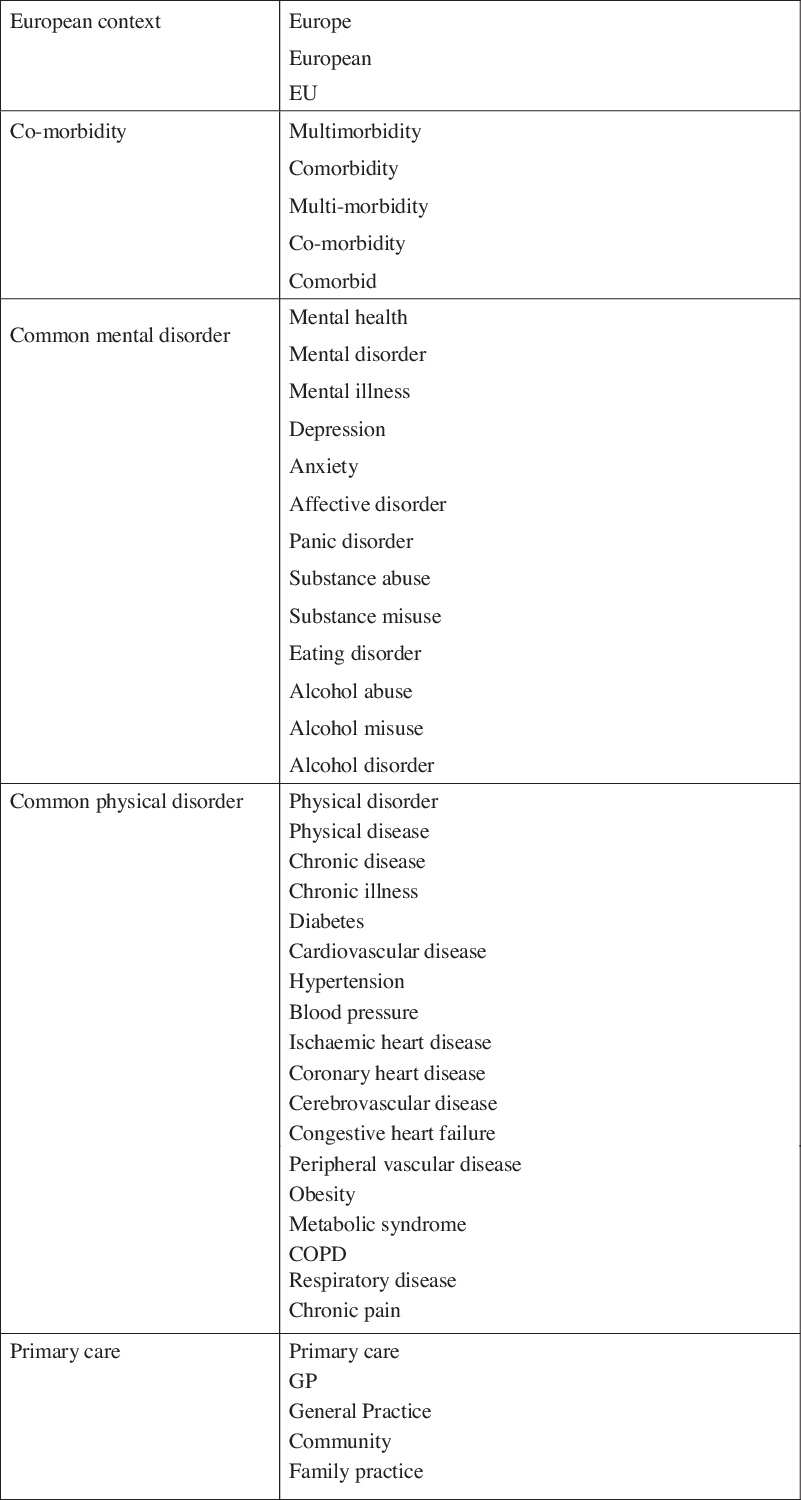

An initial reading list was generated from single or multiple search terms. From reviewing these studies, including noting of article keywords, a full list of search terms was generated. Search terms were grouped and results required mention of at least one term in each group, comprising ‘European context’, ‘co-morbidity’, ‘common mental disorder’, ‘common physical disorder’, and primary care (see Fig. 1). No time constraints were added in relation to publication date. Electronic database searches were performed on PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus and the Cochrane Library (see Fig. 2). Later, relevant peer-reviewed journals were hand-searched to identify relevant studies that were not picked up through electronic database searches.

Fig. 1. Search terms by group.

Fig. 2. Search strategy.

Selecting studies

The initial search identified 299 studies with a further 28 added from the hand-search (total n = 327). Sixty-four duplicates were removed, leaving n = 257 studies for further examination. Once the initial search was performed, studies were selected using the following inclusion criteria:

-

Based in primary care

-

Examine mental and physical comorbidity

-

Published in date range 2000–2018

-

Published in English language

-

Only European-based studies

-

Review papers

-

Examine either physical disorders in those with existing mental disorders or interventions for mental and physical comorbidity

Charting the data

Deciding on data to be charted was not a linear process and required some initial reading before the list of data to be extracted was defined. Data were charted in Microsoft Excel under the following initial headings: Authors; Year published; Name of study; Publication; Type of study; European countries examined; Instrument used in diagnosis; Mental disorder(s) examined; Physical disorder(s) examined; Intervention examined; Study Population; Rates of comorbidity (physical and mental); Instrument used for diagnosis; Major findings; Implications for research and clinical practice. Articles were read in full, annotated and recorded under each heading.

Collating, summarising, and reporting results

Data were collated to provide an overview of the breadth of the literature and to aid with presentation of findings. As is convention for a scoping review (Arksey & O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005), no assessment of quality of evidence was undertaken. The major themes identified were the types of instruments used for identifying mental disorders, the types of mental disorders and physical comorbidities examined, which interventions were used in the included studies and dropouts from studies/losses to follow-up. Metadata for each of the included studies was collated and is presented in Table 5.

Results

The database searches resulted in 299 studies with a further 28 added from a hand-search of references and following discussion with the research team, giving 327 studies for initial review. Following a title scan, where 64 studies were removed, and a title/abstract review, where a further 131 were removed, 132 studies remained for a full inclusion criteria review. All 19 studies remaining after the application of inclusion criteria were considered relevant and included for full analysis (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Identification of papers for inclusion.

Study characteristics

While no time restriction was applied to our search, studies included are all in the time range 2002–2018, reflecting comorbidity as an emerging field. Studies included were either country-based studies in any European country or part of international studies that included European countries, with the following geographical breakdown: UK (n = 5), Germany (n = 1), Ireland (n = 2), Latvia (n = 1), Czech Republic (n = 1) and International (n = 9). A broad range of methodologies was used in the selected studies, including cluster-randomised control trial (n = 2), two-armed randomised control trial (n = 1), randomised control trial (n = 1), secondary analysis of randomised control trial (n = 1), cross-sectional study (n = 3), meta-analysis (n = 5), qualitative study (n = 2), systematic review (n = 2), systematic review and meta-analysis (n = 1), and retrospective study (n = 1). Study populations included patients attending primary care, who were measured for rates of comorbidity of physical and mental health problems and/or the effects of various interventions for such comorbidity. Study populations ranged from small studies, for instance, n = 30 patients who had participated in a social prescribing intervention (Mezuk et al. Reference Mezuk, Eaton, Albrecht and Golden2008) to large international meta-analyses.

Instruments used

The use of a wide variety of mental disorder diagnostic instruments was reported, with many studies using multiple instruments (see Table 1). Primary Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Kroenke & Spitzer, Reference Kroenke and Spitzer2002), Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) (Andresen et al. Reference Andresen, Malmgren, Carter and Patrick1994) and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Spinhoven et al. Reference Spinhoven, Ormel, Sloekers, Kempen, Speckens and Van Hemert1997) were those most frequently used to diagnose depression.

Table 1. Mental health diagnostic instruments

SF-36, Short Form 36; ICD-10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision; GAD-7, General Anxiety Disorder-7; DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision.

Types of mental disorder and chronic physical conditions studied

While our search criteria allowed for studies on any common mental disorder, those that did not meet the inclusion criteria were those studies exclusively limited to depression, a combination of both depression and anxiety or any mental disorder. Depression was the mental health condition most commonly studied (n = 9 studies), followed by depression and anxiety (seven studies) and just three that examined any mental disorder. The most commonly studied comorbid physical disorder was diabetes mellitus (n = 8 studies), with three studies focusing exclusively on this condition. A number of studies examined cardiovascular-related comorbidity; three studies focused exclusively on coronary heart disease (CHD), with a further three including this disease; two examined only cardiovascular disease, while a further study included it; heart failure and hypertension were included in one study each. While many other physical disorders were included among our selected studies (see Table 2), the remaining studies focused on multimorbidity in general (n = 7) or multimorbidity with mental disorders specifically (n = 2).

Table 2. Comorbid physical disorders

Eleven studies examined the effects of various interventions in patients with physical and mental comorbidity (see Table 3). The most commonly studied intervention was collaborative care, a form of multidisciplinary approach to care, usually involving a non-medical case manager working with mental and physical healthcare teams (Coventry et al. Reference Coventry, Lovell, Dickens, Bower, Chew-Graham, McElvenny, Hann, Cherrington, Garrett, Gibbons, Baguley, Roughley, Adeyemi, Reeves, Waheed and Gask2015). Five studies compared collaborative care to usual care (Coventry et al. Reference Coventry, Lovell, Dickens, Bower, Chew-Graham, McElvenny, Hann, Cherrington, Garrett, Gibbons, Baguley, Roughley, Adeyemi, Reeves, Waheed and Gask2015; Knowles et al. Reference Knowles, Chew-Graham, Adeyemi, Coupe and Coventry2015; Panagioti et al. Reference Panagioti, Bower, Kontopantelis, Lovell, Gilbody, Waheed, Dickens, Archer, Simon, Ell, Huffman, Richards, van der Feltz-Cornelis, Adler, Bruce, Buszewicz, Cole, Davidson, de Jonge, Gensichen, Huijbregts, Menchetti, Patel, Rollman, Shaffer, Zijlstra-Vlasveld and Coventry2016; Camacho et al. Reference Camacho, Davies, Hann, Small, Bower, Chew-Graham, Baguely, Gask, Dickens, Lovell, Waheed, Gibbons and Coventry2018; van Eck van der Sluijs et al. Reference van Eck van der Sluijs, Castelijns, Eijsbroek, Rijnders, van Marwijk and van der Feltz-Cornelis2018) including one which was a qualitative study on staff and participants in a collaborative care programme. Other therapy interventions included occupational therapy (Garvey et al. Reference Garvey, Connolly, Boland and Smith2015), social prescribing (Moffatt et al. Reference Moffatt, Steer, Lawson, Penn and O’Brien2017) and a chronic disease self-management programme (Harrison et al. Reference Harrison, Reeves, Harkness, Valderas, Kennedy, Rogers, Hann and Bower2012). One study examined an Internet-based programme (Ebert et al. Reference Ebert, Nobis, Lehr, Baumeister, Riper, Auerbach, Snoek, Cuijpers and Berking2017) as a form of patient self-management and a systematic review considered both case management and self-management programmes (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Wallace, Dowd and Fortin2016). Finally, one study included any intervention at primary care level, including professional interventions (e.g. staff training) and patient interventions (e.g. self-management and peer support) (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Soubhi, Fortin, Hudon and O’Dowd2012). The remaining eight studies examined the effects of common mental disorders on physical health conditions (see Table 4).

Table 3. Types of intervention studied

Table 4. Studies examining associated morbidities

Retention rates in published studies

Some of the studies on interventions reported high loss to follow-up rates in the intervention arm of the study compared to those receiving usual care (Garvey et al. Reference Garvey, Connolly, Boland and Smith2015; Ebert et al. Reference Ebert, Nobis, Lehr, Baumeister, Riper, Auerbach, Snoek, Cuijpers and Berking2017; Camacho et al. Reference Camacho, Davies, Hann, Small, Bower, Chew-Graham, Baguely, Gask, Dickens, Lovell, Waheed, Gibbons and Coventry2018). One had a 38% rate of dropout from combined care versus 26% from usual care (Camacho et al. Reference Camacho, Davies, Hann, Small, Bower, Chew-Graham, Baguely, Gask, Dickens, Lovell, Waheed, Gibbons and Coventry2018); in another study, there was 15% rate of loss to follow-ups in the intervention group compared to 8% in the control group, with 76% in the intervention group attending at least half of the time and 13% with no attendance (Garvey et al. Reference Garvey, Connolly, Boland and Smith2015); a third study saw almost twice as many loss to follow-ups in the intervention group, with 38% also discontinuing the intervention during the trial. The higher rates of loss to follow-up in intervention cohorts need to be factored into future study design and when considering feasibility more generally.

Studies examining specific associations

Depression and diabetes mellitus: In two meta-analyses, depression was shown to increase the risk of subsequent development of type 2 diabetes mellitus compared to patients with no depression or low-depressive symptoms (Knol et al. Reference Knol, Twisk, Beekman, Heine, Snoek and Pouwer2006; Mezuk et al. Reference Mezuk, Eaton, Albrecht and Golden2008). While studies employed different methods of diagnosing both depression (for instance, self-reported or use of validated instruments such as CES-D) and diabetes [including glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) and self-reporting], results were consistent across studies (Knol et al. Reference Knol, Twisk, Beekman, Heine, Snoek and Pouwer2006). Risk was comparable to established risk factors, such as smoking and low levels of physical activity (Knol et al. Reference Knol, Twisk, Beekman, Heine, Snoek and Pouwer2006; Mezuk et al. Reference Mezuk, Eaton, Albrecht and Golden2008).

Depression and CHD: Studies on depression and CHD were among the oldest, published in 2002 and 2006 (Rugulies, Reference Rugulies2002; Nicholson et al. Reference Nicholson, Kuper and Hemingway2006). Both of these studies were meta-analyses examining baseline depression as a predictor of CHD. Depression was shown to be a strong predictor of developing CHD. Clinically measured depression was a stronger predictor of CHD than a reported low mood or where depression was measured using symptom scales. However, one study noted biased and incomplete reporting of adjustment for other conventional risk factors, therefore, leading to the conclusion that depression cannot be included as an independent risk factor for CHD based on current evidence (Nicholson et al. Reference Nicholson, Kuper and Hemingway2006).

Depression, anxiety and cardiovascular disease: Two country-based studies, in Ireland (Gallagher et al. Reference Gallagher, O’Regan, Savva, Cronin, Lawlor and Kenny2012) and Latvia (Ivanovs et al. Reference Ivanovs, Kivite, Ziedonis, Mintale, Vrublevska and Rancans2018), examined both depression and anxiety as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Both studies showed a statistically significant relationship between depression and cardiovascular disease. The Ireland-based study of adults over 50 years of age showed an 80% increased risk of cardiovascular disease, when adjusted for established risk factors, and that risk increased with the severity of depression. The study conducted in Latvia showed that both lifetime and current depression were associated with cardiovascular disease, but the causative direction of this relationship was not established. No relationship between anxiety and cardiovascular disease was found in this study; the Irish study showed that anxiety was associated with a 48% increased risk in cardiovascular disease, but comorbid anxiety with depression was not associated with an increased risk over depression alone.

Any mental disorder and any physical condition: One study considered any mental disorder as a risk factor for physical health conditions (Scott et al. Reference Scott, Lim, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Bruffaerts, Caldas-De-Almeida, Florescu, de Girolamo, Hu, de Jonge, Kawakami, Medina-Mora, Moskalewicz, Navarro-Mateu, O’Neill, Piazza, Posada-Villa, Torres and Kessler2016). A statistically significant relationship between most mental disorders and later onset of physical conditions was found, and depression, anxiety disorders and alcohol abuse were associated with subsequent diagnosis of a range of physical conditions. For instance, there is a 60% increased risk of developing arthritis in those with depression. Furthermore, the number of lifetime mental disorders was also shown to increase the risk of subsequent development of physical conditions.

Depression and anxiety comorbid with physical conditions: A study in the Czech Republic showed a high prevalence of comorbidity between depression and anxiety with other physical conditions; however, directionality was not established (Winkler et al. Reference Winkler, Horáček, Weissová, Šustr and Brunovský2015).

Interventions to address mental and physical comorbidity

Collaborative versus usual care: Collaborative care was the focus of five studies, three of which were based on the COINCIDE trial on collaborative care (Coventry et al. Reference Coventry, Lovell, Dickens, Bower, Chew-Graham, McElvenny, Hann, Cherrington, Garrett, Gibbons, Baguley, Roughley, Adeyemi, Reeves, Waheed and Gask2015; Knowles et al. Reference Knowles, Chew-Graham, Adeyemi, Coupe and Coventry2015; Camacho et al. Reference Camacho, Davies, Hann, Small, Bower, Chew-Graham, Baguely, Gask, Dickens, Lovell, Waheed, Gibbons and Coventry2018), where participants with baseline depression and heart disease and/or diabetes received brief psychological therapy by psychological well-being practitioners, who were employed as collaborative care case managers. These case managers also met with intervention arm participants’ General Practitioners (GPs) and practice nurses to discuss medications and patient progress. One study on this trial, a cluster-randomised trial, found greater improvement in depression scores (compared to baseline) at 24 months in the collaborative care arm [standardised mean difference of −0.35 (95% CI, −0.62 to −0.05)]. A study on the earlier 6-month follow-up found that in addition to lower mean depressive scores in the collaborative care arm, intervention arm participants also had fewer symptoms of anxiety [General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)], and significantly improved scores on core aspects of self-management [Health Education Impact Questionnaire (heiQ)] questionnaire (Coventry et al. Reference Coventry, Lovell, Dickens, Bower, Chew-Graham, McElvenny, Hann, Cherrington, Garrett, Gibbons, Baguley, Roughley, Adeyemi, Reeves, Waheed and Gask2015). A qualitative study (Knowles et al. Reference Knowles, Chew-Graham, Adeyemi, Coupe and Coventry2015) on a subset of participating patients and practitioners found two major contrasting themes of integration and contrast. The integration theme found that staff and patients valued the holistic approach that combining physical and mental health provided, whereas the division theme focused on the importance placed on the separation of physical and mental health. This highlights the need for a flexible approach to providing collaborative care.

A further two studies, one a meta-analysis (Panagioti et al. Reference Panagioti, Bower, Kontopantelis, Lovell, Gilbody, Waheed, Dickens, Archer, Simon, Ell, Huffman, Richards, van der Feltz-Cornelis, Adler, Bruce, Buszewicz, Cole, Davidson, de Jonge, Gensichen, Huijbregts, Menchetti, Patel, Rollman, Shaffer, Zijlstra-Vlasveld and Coventry2016) and another a meta-analysis and systemic review (van Eck van der Sluijs et al. Reference van Eck van der Sluijs, Castelijns, Eijsbroek, Rijnders, van Marwijk and van der Feltz-Cornelis2018), focused on collaborative care with depression. The former considered studies both with and without patients with physical comorbidities. Collaborative care was shown to have a small but significant effect on depression outcomes compared with usual care [standardised mean difference of −0.22 (95% CI −0.25 to −0.18)]. However, there was no significant difference between patients with or without chronic physical comorbidities or among different types of physical comorbidity. The second study also found moderately better outcomes for depression in combined care than in usual care. In contrast to the first study, there was a variety of outcomes for different mental–physical comorbidities. For example, the best physical outcomes in combined care were for hypertension, followed by HIV, COPD, multimorbid physical conditions, arthritis, cancer and acute coronary syndrome (van Eck van der Sluijs et al. Reference van Eck van der Sluijs, Castelijns, Eijsbroek, Rijnders, van Marwijk and van der Feltz-Cornelis2018).

Three other studies examined therapy-based interventions for multimorbidity in primary care (Harrison et al. Reference Harrison, Reeves, Harkness, Valderas, Kennedy, Rogers, Hann and Bower2012; Garvey et al. Reference Garvey, Connolly, Boland and Smith2015; Moffatt et al. Reference Moffatt, Steer, Lawson, Penn and O’Brien2017). In one, patients were randomised to a 6-week intervention programme, an occupational therapy-led programme involved various elements including self-management, diet and exercise, stress management and peer support, or to a control group who received usual care. There was a reduced rate of anxiety and depression at follow-up in the intervention group, with no change in the control group (Garvey et al. Reference Garvey, Connolly, Boland and Smith2015). The second study, a qualitative study, examined patients’ experiences of a social prescribing programme for multimorbidity. The programme was found to promote feelings of control and self-confidence, reduced social isolation and patients reported positive physical changes such as weight loss, increased activity and improve chronic disease management as well as mental health, resilience and coping strategies. Rapport and quality of relationship between participating patients and the social prescribing link worker were key to the successful linking of patients with relevant organisations (Moffatt et al. Reference Moffatt, Steer, Lawson, Penn and O’Brien2017). A third study examined a chronic disease self-management programme via secondary analysis of a randomised control trial. This intervention involved six 150-minute weekly group sessions. This study found that multimorbidity moderated the impact of the intervention in three areas including mental health, with the highest benefit in those patients with the highest burden of multimorbidity or with comorbid depression (Harrison et al. Reference Harrison, Reeves, Harkness, Valderas, Kennedy, Rogers, Hann and Bower2012).

One study explored a patient self-management intervention, where patients with depression and diabetes were randomised to receive an Internet-delivered self-help intervention or usual care. The potential benefits of this intervention programme include cost-effectiveness, attracting patients who do not wish to avail of traditional mental health services and avoiding the need for specific training on mental health for practitioners. This study found improvement in depression severity in both groups, with a significantly greater improvement in the intervention group (between-group effect side d = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.57 to 1.0). However, the intervention group did not have superior outcomes in terms of glycaemic control, diabetes self-management or diabetes acceptance (Ebert et al. Reference Ebert, Nobis, Lehr, Baumeister, Riper, Auerbach, Snoek, Cuijpers and Berking2017).

Finally, two systematic reviews examined interventions generally (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Soubhi, Fortin, Hudon and O’Dowd2012, Reference Smith, Wallace, Dowd and Fortin2016). The first found that organisational interventions targeting specific risk factors or areas where patients have difficulties seem more likely to be effective than broader interventions such as case management; however, it was stated that overall results are mixed and inconclusive (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Soubhi, Fortin, Hudon and O’Dowd2012). Finally, the second study found modest reductions in mean depression scores for the comorbidity studies that targeted participants with depression [standardised mean difference of −2.23 (95% CI −2.52 to −1.95)] (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Wallace, Dowd and Fortin2016).

The metadata for these studies can be found in Table 5.

Table 5. Metadata on included studies

SF-36, Short Form 36; ICD-10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision; GAD-7, General Anxiety Disorder-7; DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision; RCT, randomised controlled trial; HbA1C, glycosylated haemoglobin; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Discussion

Key findings

All 19 studies identified were in the time range 2002–2018, reflecting research on physical health among patients with mental health problems as an emerging field. Many instruments (most commonly PHQ9, CES-D and HADS) have been used to diagnose mental disorders. Loss to follow-up was a feature of many studies examining interventions to enhance the care of patients with physical and mental health problems. Such interventions include collaborative care, therapy-based interventions and self-management programmes.

In the studies identified, there is considerable focus on depression in terms of mental disorders and diabetes and cardiovascular disease as physical comorbidity. It has been highlighted how anxiety disorder is rarely studied as a comorbidity and usually features in the measurement of anxiety symptoms as an outcome (van Eck van der Sluijs et al. Reference van Eck van der Sluijs, Castelijns, Eijsbroek, Rijnders, van Marwijk and van der Feltz-Cornelis2018). We found no studies on anxiety as comorbidity that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Mental–physical comorbidity is a relatively recent area of research, with the oldest study included in this review from 2002, which may account for the limited research available; in particular, long-term data are scarce and we found no studies on the association between mental–physical comorbidity with a longitudinal or prospective design.

From research to date, evidence points towards a casual association between baseline depression and the development of certain chronic physical illness, particularly diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Mezuk et al. Reference Mezuk, Eaton, Albrecht and Golden2008; Foran et al. Reference Foran, Hannigan and Glynn2015; Toftegaard et al. Reference Toftegaard, Gustafsson, Uwakwe, Andersen, Becker, Bickel, Bork, Cordes, Frasch, Jacobsen, Kilian, Larsen, Lauber, Mogensen, Rössler, Tsuchiya and Munk-Jørgensen2015) (although this finding was not universal (Nicholson et al. Reference Nicholson, Kuper and Hemingway2006)), with comparable strength to traditional risk factors such as smoking and low physical activity (Toftegaard et al. Reference Toftegaard, Gustafsson, Uwakwe, Andersen, Becker, Bickel, Bork, Cordes, Frasch, Jacobsen, Kilian, Larsen, Lauber, Mogensen, Rössler, Tsuchiya and Munk-Jørgensen2015). Evidence for baseline anxiety as a risk factor for chronic illness was equivocal (Gallagher et al. Reference Gallagher, O’Regan, Savva, Cronin, Lawlor and Kenny2012; Ivanovs et al. Reference Ivanovs, Kivite, Ziedonis, Mintale, Vrublevska and Rancans2018) and one further study did provide evidence for any mental disorder increasing the risk for any chronic physical illness (Scott et al. Reference Scott, Lim, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Bruffaerts, Caldas-De-Almeida, Florescu, de Girolamo, Hu, de Jonge, Kawakami, Medina-Mora, Moskalewicz, Navarro-Mateu, O’Neill, Piazza, Posada-Villa, Torres and Kessler2016).

Limitations

While we attempted to include a comprehensive set of search terms, our scoping review was limited to key medical databases which resulted in possible omissions, and this was evident from the additional results that came from hand-searching of literature. A more comprehensive search along with searching further databases and the inclusion of grey literature could have increased the number of studies included. No assessment of the quality of studies was undertaken as part of this review, following the guidance of Arksey & O’Malley (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005). Non-English language articles were excluded to allow for authors’ understanding, which had the potential to remove relevant texts from the review; however, n = 0 papers were removed due to language.

Implications for research, practice and policy

This review paper highlights research on mental and physical health in Europe, which has practical implications for primary care. QRISK ®3-2018 introduced SMI and atypical antipsychotic medications as risk factors for cardiovascular disease (ClinRisk, 2018). By focusing on studies in Europe, the authors intend to use the findings from this review to inform the design of a European Union project examining this topic empirically. Limitations of research to date prevented one of the oldest studies included from recommending that depression is included as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, where methodological weaknesses such as biased and incomplete adjustments and reverse causality were highlighted (Nicholson et al. Reference Nicholson, Kuper and Hemingway2006); however, with growing evidence since then, this position should now be reconsidered. It has been suggested that cardiovascular disease screening in patients with depression should be adopted, along with enhanced training for mental health at primary care to improve outcomes in both mental and physical health and the use of interventions to prevent chronic physical conditions from occurring in these patients (Scott et al. Reference Scott, Lim, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Bruffaerts, Caldas-De-Almeida, Florescu, de Girolamo, Hu, de Jonge, Kawakami, Medina-Mora, Moskalewicz, Navarro-Mateu, O’Neill, Piazza, Posada-Villa, Torres and Kessler2016; Ivanovs et al. Reference Ivanovs, Kivite, Ziedonis, Mintale, Vrublevska and Rancans2018). Studies on collaborative care have shown improved outcomes for mental–physical comorbidity compared to usual care (Coventry et al. Reference Coventry, Lovell, Dickens, Bower, Chew-Graham, McElvenny, Hann, Cherrington, Garrett, Gibbons, Baguley, Roughley, Adeyemi, Reeves, Waheed and Gask2015; Knowles et al. Reference Knowles, Chew-Graham, Adeyemi, Coupe and Coventry2015; Panagioti et al. Reference Panagioti, Bower, Kontopantelis, Lovell, Gilbody, Waheed, Dickens, Archer, Simon, Ell, Huffman, Richards, van der Feltz-Cornelis, Adler, Bruce, Buszewicz, Cole, Davidson, de Jonge, Gensichen, Huijbregts, Menchetti, Patel, Rollman, Shaffer, Zijlstra-Vlasveld and Coventry2016; Camacho et al. Reference Camacho, Davies, Hann, Small, Bower, Chew-Graham, Baguely, Gask, Dickens, Lovell, Waheed, Gibbons and Coventry2018; van Eck van der Sluijs et al. Reference van Eck van der Sluijs, Castelijns, Eijsbroek, Rijnders, van Marwijk and van der Feltz-Cornelis2018) and can be implemented to manage the effect of mental–physical comorbidity (Camacho et al. Reference Camacho, Davies, Hann, Small, Bower, Chew-Graham, Baguely, Gask, Dickens, Lovell, Waheed, Gibbons and Coventry2018). Evidence was also promising for the use of other interventions, including both practitioner and self-help-based programmes (Harrison et al. Reference Harrison, Reeves, Harkness, Valderas, Kennedy, Rogers, Hann and Bower2012; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Soubhi, Fortin, Hudon and O’Dowd2012, Reference Smith, Wallace, Dowd and Fortin2016; Garvey et al. Reference Garvey, Connolly, Boland and Smith2015; Ebert et al. Reference Ebert, Nobis, Lehr, Baumeister, Riper, Auerbach, Snoek, Cuijpers and Berking2017; Moffatt et al. Reference Moffatt, Steer, Lawson, Penn and O’Brien2017).

Within the parameters of included studies, there is a lack of consensus on the use of an agreed instrument to diagnose mental disorders; however, one meta-analysis did show consistent results regardless of instrument used (Knol et al. Reference Knol, Twisk, Beekman, Heine, Snoek and Pouwer2006). It can therefore be surmised that the use of a validated diagnostic instrument rather than the choice is more important; however, further evidence on this is indicated.

Further research in this emerging field is essential in order to understand the potential pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the association between baseline mental disorders and chronic conditions (Knol et al. Reference Knol, Twisk, Beekman, Heine, Snoek and Pouwer2006; Gallagher et al. Reference Gallagher, O’Regan, Savva, Cronin, Lawlor and Kenny2012). There is a need for longitudinal prospective studies (Gallagher et al. Reference Gallagher, O’Regan, Savva, Cronin, Lawlor and Kenny2012; Foran et al. Reference Foran, Hannigan and Glynn2015; Scott et al. Reference Scott, Lim, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Bruffaerts, Caldas-De-Almeida, Florescu, de Girolamo, Hu, de Jonge, Kawakami, Medina-Mora, Moskalewicz, Navarro-Mateu, O’Neill, Piazza, Posada-Villa, Torres and Kessler2016) with larger sample sizes (Ivanovs et al. Reference Ivanovs, Kivite, Ziedonis, Mintale, Vrublevska and Rancans2018) to confirm findings to date, where confounding factors are controlled for (Knol et al. Reference Knol, Twisk, Beekman, Heine, Snoek and Pouwer2006; Mezuk et al. Reference Mezuk, Eaton, Albrecht and Golden2008) and the duration and severity of mental disorder are considered (Knol et al. Reference Knol, Twisk, Beekman, Heine, Snoek and Pouwer2006). In addition, data on the feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness of interventions which enhance the care of mental disorders can also enhance physical health-related outcomes more generally (Mezuk et al. Reference Mezuk, Eaton, Albrecht and Golden2008) and optimise the delivery of care (Panagioti et al. Reference Panagioti, Bower, Kontopantelis, Lovell, Gilbody, Waheed, Dickens, Archer, Simon, Ell, Huffman, Richards, van der Feltz-Cornelis, Adler, Bruce, Buszewicz, Cole, Davidson, de Jonge, Gensichen, Huijbregts, Menchetti, Patel, Rollman, Shaffer, Zijlstra-Vlasveld and Coventry2016), particularly when considering the lower rates of completion of programmes and higher losses to follow-up compared to usual care.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interests

Frank Fogarty has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Geoff McCombe has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Katherine Brown has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Therese Van Amelsvoort has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Mary Clarke has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Walter Cullen has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The authors assert that ethical approval for publication of this review article was not required by their local Ethics Committee.