Introduction

The World Federation for Medical Education (WFME), an international organisation linked to the World Health Organisation includes psychiatry as a core undergraduate speciality (Walton, Reference Walton1999; WFME, 2003), with the Medical Council (2008–2013) undergraduate standards based on these guidelines. Each of the six medical schools in Ireland; Trinity College Dublin (TCD), University College Dublin (UCD), the Royal College of Surgeons, Ireland (RCSI), University College Cork (UCC), the National University of Ireland, Galway (NUIG) and University of Limerick (UL) teach and assess psychiatry as an integral component of their medical curriculum. Although many similarities exist in relation to the delivery and assessment of psychiatry at undergraduate level in Ireland, several differences are also present (Karim et al. Reference Karim, Edwards, Dogra, Anderson, Davies, Lindsay, Ring and Cavendish2009) although these have to date not been examined in detail. The Medical Council has recognised and encouraged differences in delivery of undergraduate education as students can apply to medical schools they feel are more suitable to their expectations, preferences and learning styles. All medical schools, however, have the same goal of ‘producing graduates with the knowledge, skills and behaviours to enter internship and be equipped for lifelong learning’ (Medical Council, 2008–2013).

Recruitment into psychiatry has been an on-going problem with rates at around 4–5% of medical students choosing psychiatry noted in the United Kingdom although a slightly higher percentage of graduates from Northern Ireland and Scotland favoured a career in psychiatry (Goldacre et al. Reference Goldacre, Fazel, Smith and Lambert2013). Little variation in the rates of choosing psychiatry as a career in the United Kingdom has been noted over the last 35 years (Goldacre et al. Reference Goldacre, Fazel, Smith and Lambert2013).

An examination of the methods of delivery and assessment of psychiatry across various medical schools will inform educators in psychiatry of the differences and similarities that currently exist between universities and are a starting point for discussion regarding the areas where medical schools could jointly work for the benefit of students. Similar ventures have been undertaken in Scotland where liaison between universities in relation to psychiatric curricula and assessment methods have lead to closer collaboration between universities, although no uniform curriculum or assessment method is in place at present (Wilson & Eagles, Reference Wilson and Eagles2008).

The delivery of undergraduate education including psychiatry has significantly changed over the last 20 years with an increasing use of small group-based teaching techniques, the application of e-learning resources via learning management systems such as Blackboard and Moodle, and the use of varied assessment methods including continuous assessment.

In this study, we attempted to obtain information in relation to the organisation and delivery of the psychiatric curriculum, the integration of psychiatry across the entire medical curriculum and the means of assessment of psychiatry at undergraduate level across the six medical schools in Ireland. Consequently, our aims are to compare how psychiatry teaching is delivered and assessed across medical schools in Ireland.

Methods

A senior psychiatry faculty member was contacted in writing regarding this study and asked if they wished collaborate in writing this article. Each faculty member was asked to provide details of the organisation and delivery of their psychiatric curriculum and the various assessment methods employed in their medical school. Specific queries related to the organisation and delivery of the curriculum and included the use of lectures, tutorials; small group-based teaching methods including problem-based learning (PBL) sessions, the recording of attendance via logbooks and the use of e-learning resources. Faculty members were also asked to provide details of assessment procedures including continuous assessment measures, and summative assessments including multiple choice questions (MCQs), extending matching questions (EMQs), essay questions and clinical examinations such as Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs) and vivas.

Finally, faculty members were asked to evaluate the degree of integration of psychiatry in the entire medical course of their medical school. They were asked to use the 11-step integration ladder to evaluate this integration (Harden, Reference Harden, Stevenson, Downie and Wilson2000). Harden describes 11 discrete steps between discipline-specific teaching and integrated teaching. The steps are as follows: (1) isolation, (2) awareness, (3) harmonisation, (4) nesting, (5) temporal co-ordination, (6) sharing, (7) correlation, (8) complementary, (9) multidisciplinary, (10) interdisciplinary and (11) transdisciplinary. The higher the step on the ladder the more integrated the curriculum.

Information was collated and is presented in tabular format.

Results

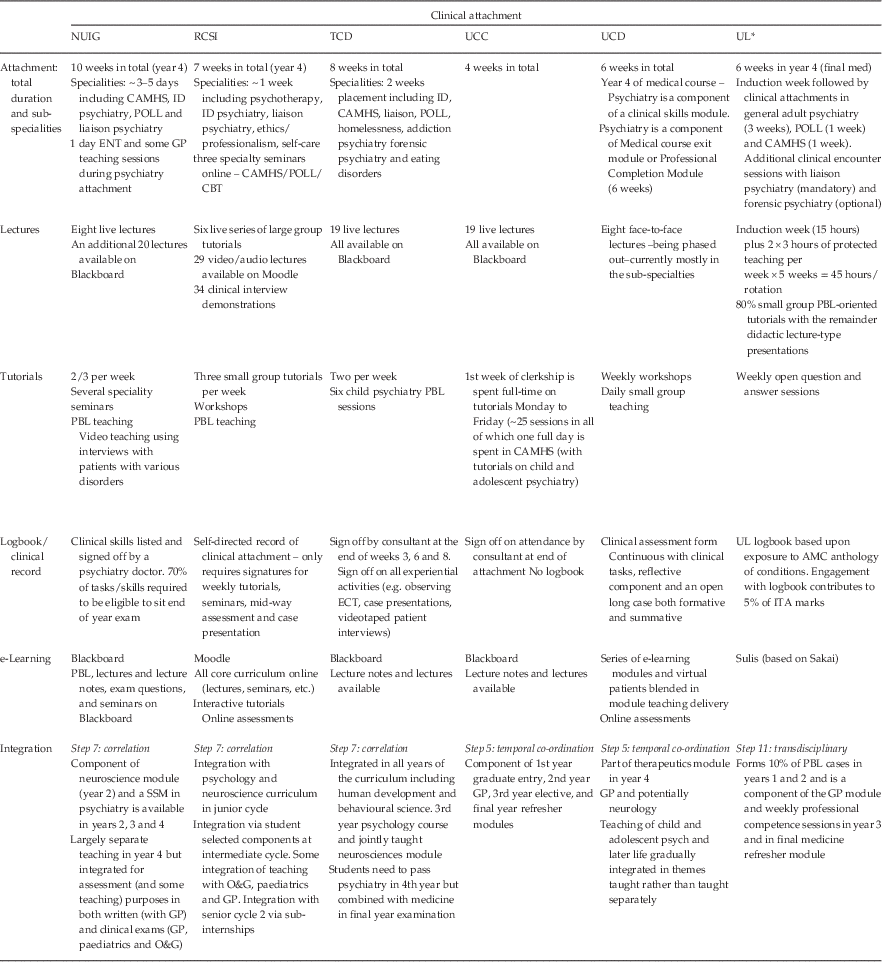

A senior faculty member from each of the six medical schools who offer undergraduate medical degrees in Ireland agreed to collaborate on this study. Information pertaining to the provision of lectures, the duration of attachment and clinical specialities offered, provision of tutorials, monitoring of attendance, e-learning resources and their employment and integration with the entire medical curriculum are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1 Delivery of psychiatry teaching

NUIG, National University of Ireland, Galway; RCSI, Royal College of Surgeons, Ireland; TCD, Trinity College Dublin; UCC, University College Cork; UCD, University College Dublin; UL, University of Limerick; CAMHS, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services; CBT, cognitive behaviour therapy; ID, intellectual disability; POLL, psychiatry of later life; ENT, ear, nose and throat; GP, General Practice; PBL, problem-based learning; ECT, electroconvulsive therapy; ITA, in-training assessment; AMC, Australian Medical Council; SSM, special student module; O&G, obstetrics and gynaecology.

* Attachment is in final year of 4-year medical degree course.

The duration of psychiatry clinical attachment ranged from 4 to 10 weeks and took place in the second last year of medicine in all medical schools except for UL where it was in the final year of a 4-year graduate entry medical programme. Speciality clinical attachments were available at all medical schools, with the longest period of speciality attachment available at TCD (2 weeks). Clinical attendance is monitored at each medical school, with a logbook utilised to record attendance at all sites except for UCC. The logbook requires signature by clinicians for a large variety of clinical activities at NUIG, UL and UCD, for weekly tutorials or seminars at RCSI and for experiential activities at TCD and on three occasions throughout the attachment by their assigned supervising consultant.

Lectures were provided in all medical schools, and these were delivered live in five medical schools (TCD, RCSI, UCC, UL, NUIG), although additionally recorded lectures were available at two sites (RCSI, NUIG). All sites also delivered small group-based tutorials to students throughout their clinical attachment, with components such as senior clinician delivered case presentations, PBL sessions and teaching with the aid of patient videos also utilised (NUIG and TCD).

e-Learning resources are available at all sites with four medical schools utilising Blackboard (UCD, TCD, UCC and NUIG), one medical school utilising Moodle (RCSI) and one medical school utilising Sulis, which is based on Sakai (UL). As presented in Table 1, a large variety of course materials, PBL sessions and assessments are provided via these platforms.

Psychiatry is integrated spirally and horizontally across the medical curriculum at all medical schools as presented in Table 1. However, such integration is implemented to quite varying degrees. UL provides the most integrated curriculum reaching step 11. This was followed by TCD and NUIG on step 7 with UCC, UCD and the RCSI on step 5.

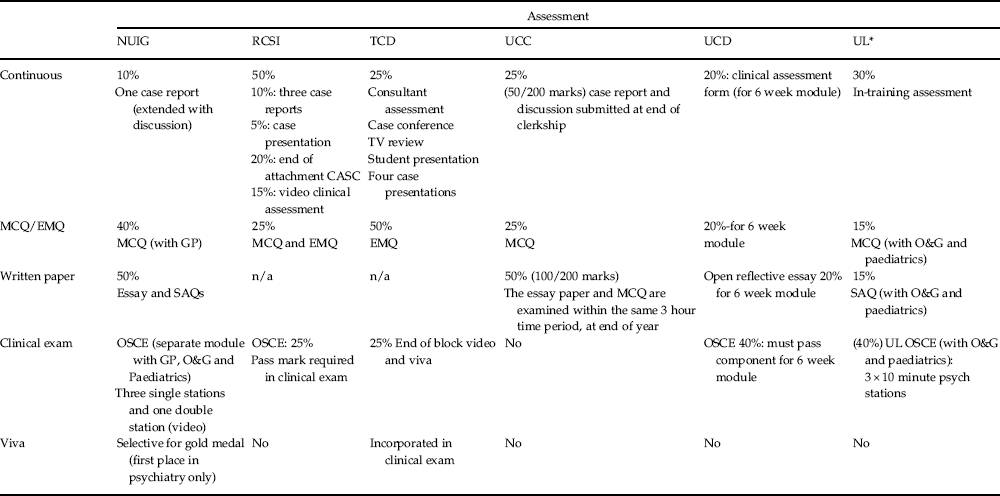

Continuous assessment and summative examinations are presented in Table 2. All medical schools utilise continuous assessment as a component of summative assessment, with the total marks ranging from 10% to 35% depending on the medical school. A range of components are included in this assessment across medical schools with only a case report(s) or presentation(s) standard across all medical schools. All medical schools except for TCD have an MCQ paper in psychiatry with TCD providing an EMQ paper. The weighting for these papers varies across medical schools with TCD having the highest weighting for this exam component (50%). TCD unlike the other medical schools do not set a written paper. Further variation exists within this exam component with three medical schools including an open reflective component (essay or reflective e-tivity) (UCD, NUIG, UL).

Table 2 Assessment of psychiatry

NUIG, National University of Ireland, Galway; RCSI, Royal College of Surgeons, Ireland; TCD, Trinity College Dublin; UCC, University College Cork; UCD, University College Dublin; UL, University of Limerick; CASC, clinical assessment of skills and competencies; MCQ, Multiple Choice Questions; EMQ, extended matching questions; GP, General Practice; O&G, obstetrics and gynaecology; SAQs, short answer questions; OSCE, Objective Structured Clinical Examinations.

* Attachment is in final year of 4-year medical degree course.

A clinical exam is present in all medical schools except for UCC. Within the clinical exam, differences exist including varying numbers of stations at the OSCE exam and the inclusion of video-based clips as a component of the OSCE (NUIG). A viva (viva voce) is held for all students at TCD but is selectively used for borderline grade students only at UCD, or to decide the gold medal awardee at NUIG. TCD requires students to pass psychiatry within the 4th year but the marks go forward to the final (5th) year where they form part of the joint final examination in medicine and psychiatry. This is a combined clinical examination with minor and major cases with ~20% of students being examined on patients with a psychiatric disorder or a combination of medical and psychiatric conditions. Psychiatrists examine along with their internal medicine colleagues for ~33% of students in this exam. A similar assessment process in the exit module course occurs in UCD, with psychiatric co-morbidities often present in major cases.

Discussion

Psychiatry is an important component of the medical curriculum in all medical schools in Ireland with access to both general adult psychiatry and varying sub-specialities, depending on availability. This is important as teaching of psychiatry at undergraduate level has been demonstrated to be a significant factor in doctors choosing psychiatry as a career (Dein et al. Reference Dein, Livingston and Bench2007). A review of the impact of undergraduate experiences on psychiatric recruitment suggests that students are highly positive about a career in psychiatry before entering medical school and this dissipates during the undergraduate years (Eagles et al. Reference Eagles, Wilson, Murdoch and Brown2007). These authors suggested that recruitment into psychiatry could be improved by teachers through promoting positive attitudes among students by encouraging early undergraduate exposure, identifying and encouraging students with an aptitude for psychiatry, ensuring students have busy clinical attachments in which they see patients who attain good responses to treatment, emphasising the evidence base in psychiatry treatments and highlighting the potential lifestyle benefits of a career in psychiatry (Eagles et al. Reference Eagles, Wilson, Murdoch and Brown2007). Undergraduate medical students’ attitudes to psychiatry in UCD were measured in 1994 and 2010 both before and after psychiatry teaching. Medical students’ attitudes were more positive towards psychiatry post psychiatry attachments and were significantly more positive in 2010 compared with their student counterparts in 1994 (O’Connor et al. Reference O’Connor, O’Loughlin, Somers, Wilson, Pillay, Brennan, Clarke, Guerandel, Casey, MAlone and Lane2012). Despite these improved attitudes to psychiatry, recruitment rates into psychiatry were not significantly different between 1994 and 2010. The authors suggested that innovative methods to translate these positive attitudes into careers in psychiatry were thus required (O’Connor et al. Reference O’Connor, O’Loughlin, Somers, Wilson, Pillay, Brennan, Clarke, Guerandel, Casey, MAlone and Lane2012). Indeed, psychiatry recently was added as one of the disciplines where graduating students can pursue an internship (Medical Council, 2008–2013).

Clinical attachment

A substantial variation in the duration of clinical attachment (4–10 weeks) was noted between the various medical schools, with structured teaching included in some cases. Clinical experience for students in addition to general adult psychiatry was provided by all medical schools, however, this varied in duration, largely depending on the resources of sub-specialities available to the medical school. The Dublin-based medical schools, for example, provide visits to the national forensic psychiatry service (Central Mental Hospital). Although the inclusion of psychiatry sub-specialities is a relatively small component of the entire clinical attachment, it is potentially beneficial in broadening clinical exposure for students. Indeed, early exposure to child and adolescent psychiatry has been demonstrated as an important factor in medical students subsequently choosing this sub-speciality as a career (Volpe et al. Reference Volpe, Boydell and Pignatiello2013).

Large group teaching

Traditional large group teaching sessions (lectures) employed widely in medical education has been replaced in many instances by smaller group teaching techniques (Cantillon, Reference Cantillon2003). However, large group teaching sessions remain the most efficient method of delivering core knowledge, explaining concepts and stimulating interest for students (Bligh, Reference Bligh1998). However, there are also several disadvantages with this teaching method including in particular passive learning on behalf of the student resulting in reduced attention levels. Strategies for promoting active student participation that can be employed include asking students questions during lectures, providing time within the lecture session for questions to be asked and using a problem-orientated approach (Brown & Manogue, Reference Brown and Manogue2001). Even in large groups teaching sessions, other methods such as the use of brainstorming and breaking a large group up into buzz groups can help facilitate learning (Cantillon, Reference Cantillon2003). Factors shown to be associated with medical students attending live lectures include being female, ‘visual lecture topics’ such as anatomy or histology and the perceived quality of the lecturer (Gupta & Saks, Reference Gupta and Saks2013).

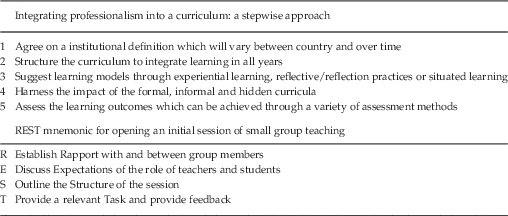

In recent years, with advances in technology, recorded lectures are available in many medical schools with two completely replacing their live lectures programme (UCD, RCSI) and three using recorded videos as a supplement to live lectures (TCD, UCC, NUIG). Recorded lectures have the advantage of being available 24 hours/day; can be viewed on multiple occasions, watched at a pace suitable to the student. In addition, the recorded lectures may have an important role in reinforcing knowledge and providing more flexibility for different learning styles and encouraging self-directed learning (Kerfoot et al. Reference Kerfoot, Baker, Jackson, Hulbert, Federman, Oates and DeWolf2006; Lovell & Plantegenest, Reference Lovell and Plantegenest2009; Schreiber et al. Reference Schreiber, Fukuta and Gordon2010; Franklin et al. Reference Franklin, Gibson, Samuel, Teeter and Clarkson2011; Subramanian et al. Reference Subramanian, Timberlake, Mittakanti, Lara and Brandt2012). A live lecture, however, allows students to have contact with the lecturer, and provides an opportunity for the learning of attitudes from an ‘inspiring lecturer’(Crosby, Reference Crosby2000). This forms part of the ‘hidden curriculum’, which has been identified as an often forgotten about but important aspect of the medical curriculum (Hafferty & Franks, Reference Hafferty and Franks1994). Senior faculty members and good role models can have a long-lasting effect on a students’ professionalism as noted in a recent Canadian study, which concluded this factor to be the single most important part of the medical undergraduate curriculum relating to professionalism (Byszewski et al. Reference Byszewski, Hendelman, McGuinty and Moineau2012). A recent review on the difficult task of integrating professionalism into a curriculum suggests following a five-point stepwise approach (see Table 3) (O’Sullivan et al. Reference O’Sullivan, Van Mook, Fewtrell and Wass2012).

Table 3 Effective small group teaching: Association for Medical Education in Europe guides

Small group teaching

Small group teaching sessions are employed to give the learner the opportunity to achieve a deep understanding of the material. This is achieved through actively interacting with others, developing their listening skills, formulating acquired knowledge and explaining their thinking clearly to others, and is optimally achieved when small group sessions are well planned and well structured (Brookfield & Preskill, Reference Brookfield and Preskill1999). The teacher using effective small group teaching methods should be merely a guide and not revert to being the ‘expert’ or the authority figure (King, Reference King1993). A suitable set of group tasks, which are clear to the students, with the teacher resisting the urge to answer questions, thus giving students the opportunity to attempt a response and reason aloud and appropriate group rules (i.e. not talking at the same time as other group members) are required. An Association for Medical Education in Europe guide on effective small group teaching suggests on opening the initial session of small group teaching to use the mnemonic REST (see Table 3) (Edmunds & Brown, Reference Edmunds and Brown2010). Different group structures can be employed depending on group dynamics and the learning outcomes one wishes to achieve. These structures include buzz groups, snowball groups, fishbowls, crossover groups, circular questioning and horseshoe groups (Jaques, Reference Jaques2003). In addition, the physical learning environment is also important with, for example, all members of the small group seated in a circle to enhance communication (Hutchinson, Reference Hutchinson2003).

All Irish medical schools provide two to five small group teaching sessions weekly in psychiatry. Students are recorded interviewing patients in NUIG and TCD and these interviews are later evaluated by tutors with students present in order to deliver feedback on their communication and interview skills.

e-Resources

All Irish medical schools utilise an e-learning platform for the teaching of psychiatry. These platforms have become an essential component for the organisation and delivery of teaching to students and have also been employed in some instances for student assessment. The need for these resources has particularly risen in recent years to facilitate learning for students allocated to clinical placements in smaller hospitals or primary care settings geographically distant from their teaching base. These platforms can be utilised to communicate with individuals, groups or an entire class of students, can provide students with timetables (both electronic and traditional), course materials (written documents, recorded lectures – visual and audio, internet-based material) and formal e-learning modules. In addition, they can be used for presentations as online discussions sites and to hold live online seminars. In relation to assessment, students can upload their assignments and receive grades, with examiners able to identify late submissions and utilise turnitin to identify possible plagiarism. MCQ and EMQ examinations can be undertaken through an e-learning platform (currently undertaken in RCSI and NUIG) with the instant production of results and associated metrics, which can be utilised to refine questions or inform assessors on whether questions are re-usable for future examinations. Indeed, the utilisation of e-platforms allows analysis regarding the entire examination and individual components within this examination.

All e-learning systems essentially have similar functions and are utilised for similar (albeit not identical) purposes with various advantages and disadvantages in relation to cost, accessibility and design. Moodle and Sakai are open source and consequently free to use. In addition, they are more customisable (the ability to modify according to individual requirements) but they can be difficult to setup and fine tune and therefore require IT specialists and a separate server. However, Blackboard although associated with a cost is ready ‘out of the box’ and support is provided by this organisation (Young, Reference Young2008). An increasing utilisation of e-learning resources to increase the teaching experience of students in psychiatry is anticipated and is commensurate with Medical Council (2008–2013) guidelines. For example, at NUIG, the Technology-Enhanced Teaching and Learning organisation facilitate e-learning resources by creating e-learning modules for use across the medical curriculum, including psychiatry. A similar support structure is provided at UCD and by the Centre for Academic Practice and eLearning at TCD.

Although newer technologies have been shown to be as effective as traditional-based teaching sessions, their use to date has largely been complimentary to existing teaching resources (Chumley-Jones et al. Reference Chumley-Jones, Dobbie and Alford2002). e-Learning can, however, allow students engage in self-directed active learning and be self-assessors of their own competence (Ruiz et al. Reference Ruiz, Mintzer and Leipzig2006). As opposed to lectures, computer-aided tutorials and web-based teaching cases could potentially be employed in the future with evidence suggesting that these techniques could aid longer term knowledge.

Integration

Neuroscience, social and psychological development and communication skills are usually delivered in the earlier years of medical curricula with psychiatry learning developed on a foundation of these topics [although early patient contact in years one and two of medical programmes in the Ireland is now a regular occurrence and is supported by the Medical Council (2008–2013)]. Psychiatry teaching has thus been integrated spirally into the medical curriculum. In clinical years, psychiatry is integrated to varying degrees across medical schools with this most evident in UL. Mental health and physical health difficulties are often co-morbidly present with either one affecting the other. Integrated teaching offers the student the opportunity to attain a greater insight into such co-morbidity and allows students observe multidisciplinary care that might be unattainable if the student’s teaching was entirely discipline based. Psychiatry teaching can also be delivered, for example, in a primary care setting. Observing patients with mental health difficulties across various medical disciplines such as General Practice can offer a more ‘person-centred’ approach, which can improve students attitudes to mental illness by reducing stereotyping and increasing empathy (Walters et al. Reference Walters, Raven, Rosenthal, Russell, Humphrey and Buszewicz2007). Neurology and psychiatry have been separated arbitrarily over the past century. There are many diseases and disorders that overlap and research within these areas believed by many to be converging (Martin, Reference Martin2002). Barriers between disciplines could potentially be broken down by a more integrated undergraduate curriculum beginning perhaps with the neurosciences. However, there are also advantages to having specific time dedicated to individual disciplines such as psychiatry. Psychiatry is a secondary care discipline with a distinct identity that is underlined by a separate modular status within the curriculum. Students encounter patients with acute severe mental illnesses and learn how to assess, communicate with and treat patients with florid conditions such as psychosis and mania. They also learn how to manage treatment-resistant schizophrenia and occasionally get to observe the delivery and benefits of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) first-hand. Students also learn how to assess risk and how to competently take a detailed psychiatric history and perform a proficient mental state examination, which is discipline specific.

Assessment of learning

Assessment of learning in individual medical schools reflects assessment methods, student numbers, staff resources and alignment with curriculum learning outcomes. A variety of written summative assessments are utilised across medical schools to examine psychiatry. It has been argued that no individual written assessment method or question is superior to other; rather they assess different aspects of knowledge and attitudes Schuwirth & Van Der Vleuten, Reference Schuwirth and Van Der Vleuten2004). Indeed as all methods have their strengths and weaknesses, the inclusion of a variety of written assessments are optimal to examine the intended learning objectives (Al-Wardy, Reference Al-Wardy2010).

Essay questions (open-reflective responses) typically assess a student’s ability to understand material, process it in a given context and formulate an articulate response, and thus potentially examine higher order learning. Students are expected to reach the top level of Blooms Taxonomy of educational objectives, of which there are six levels. These are (1) knowledge – merely remembering facts, (2) comprehension – understanding material, (3). application – using the knowledge to solve a problem, (4) analysis – analyse a problem, (5) synthesis – use facts to create new theories and (6) evaluation – assess information and come to a 1conclusion (Bloom, Reference Bloom1956). Students are expected to move up each level as their knowledge increases and they are ranked from lower order (1–4) to higher order learning (5, 6). Essay questions have their disadvantages, however. Most notably, they are time consuming to correct, and are associated with difficulties with examiner reliability, although examiner reliability can be resolved by all essay questions been assessed by one examiner, who also re-checks their scoring (Schuwirth & Van Der Vleuten, Reference Schuwirth and Van Der Vleuten2004; Brown et al. Reference Brown, Bull and Pendlebury2013). As opposed to essay questions, short answer questions (SAQs) are less time consuming to correct and test greater areas of knowledge with structured marking schemes possible which examiners (with support or mentoring) can adhere to. Although SAQs rarely examine higher order learning, they minimise cueing (recognising the correct option without reasoning) which can be problematic with MCQs (Schuwirth & Van Der Vleuten, Reference Schuwirth and Van Der Vleuten2004).

MCQs and EMQs assess a wider range of a syllabus compared with essays or SAQs in a relatively short time frame and allow for easy correction and standardisation particularly if the exams are computer based, which is available on the various e-platforms utilised in the Republic of Ireland medical schools. However, drafting questions rich in content, that test higher order learning, and that differentiate between weak and strong students are time consuming and difficult to write (Cohen & Wollack, Reference Cohen and Wollack2000). EMQs have the advantage over MCQs in that they can more easily test higher order learning (Blooms Taxonomy levels 5 and 6) (Wood, Reference Wood2003), although well-constructed MCQs also have this ability (Harper, Reference Harper2003). However, EMQs are potentially more difficult to devise and are beset with the other disadvantages associated with MCQs (Harper, Reference Harper2003).

Clinical examinations

The OSCE was introduced in the 1970s. Advantages of the OSCE over traditional clinical examinations relate to its reliability and validity in assessing clinical competencies (Harden et al. Reference Harden1975). The OSCE is now used worldwide throughout medical schools and deemed to be the ‘gold standard’ of clinical assessments (Hodges, Reference Hodges2003). Disadvantages with the OSCE include cost in terms of both time and finance. The OSCE is thought to be adequate for assessing undergraduate clinical psychiatry competencies but may not be suitable for more advanced psychiatric skills in postgraduate examinations (Benning & Broadhurst, Reference Benning and Broadhurst2007; Marwaha, Reference Marwaha2011).

The viva (viva voce) or clinical oral examination has been a traditional component of assessment in medical education in Europe (Weisse, Reference Weisse2002). It has fallen out of favour with medical educationalists due to poor reliability (Colton & Peterson, Reference Colton and Peterson1967; Foster et al. Reference Foster, Abrahamson, Lass, Girard and Garrís1969; Kelley et al. Reference Kelley, Matthews and Schumacher1971). Furthermore, the viva has also been demonstrated to induce stress for students which adversely impacts on their performance (Pokorny & Frazier, Reference Pokorny and Frazier1966; Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Mellsop, Callender, Crawshaw, Ellis, Hall, MacDonald and Silfverskiold1993). Advocates of the traditional oral examinations have suggested advantages such as assessing problem solving and reasoning, recognition of safe and competent clinicians and feedback on the curriculum, although there is little evidence to support these claims (Davis & Karunathilake, Reference Davis and Karunathilake2005). A number of factors have been found to improve the reliability of the viva (Davis & Karunathilake, Reference Davis and Karunathilake2005). These include structuring the viva on clinical scenarios to assess problem-solving ability (Anastakis et al. Reference Anastakis, Cohen and Reznick1991; Kearney et al. Reference Kearney, Puchalski, Yang and Skakun2002), undertaking more than one viva exam (Stillman et al. Reference Stillman, Lane, Beeth and Jaffe1983; Daelmans et al. Reference Daelmans, Scherpbier, Vleuten and Donker2001), using two or more examiners (Swanson, Reference Swanson1987; Wass et al. Reference Wass, Wakeford, Neighbour and Van der Vleuten2003), asking students similar questions (Amiel et al. Reference Amiel, Tann, Krausz, Bitterman and Cohen1997), using descriptors, rubrics or criteria for answers (Anastakis et al. Reference Anastakis, Cohen and Reznick1991) and examiner training (Des Marchais & Jean, Reference Des Marchais and Jean1993; Wakeford et al. Reference Wakeford, Southgate and Wass1995). The viva accounts for only a minor component of the overall assessment marks when used to examine undergraduate psychiatry in Ireland.

Conclusion

In Ireland, there are a wide variety of teaching and assessment methods employed in psychiatry to produce ‘graduates with the knowledge, skills and behaviours to enter internship and be equipped for lifelong learning’ as envisioned by the Irish Medical Council. Having a greater understanding of how psychiatry is delivered and assessed at different medical schools can enable educators provide additional teaching materials, including on e-learning platforms. Sharing of resources between medical schools could have significant benefits for both students and educators alike in relation to both the delivery of teaching and student assessment. Such resources could include e-learning modules and MCQ’s or EMQs associated with good validity, reliability and discrimination indices metrics. Consequently, we suggest on-going liaison between medical schools in relation to the delivery and assessment of psychiatry at undergraduate level and discussions in relation to the potential standardisation of some aspects of psychiatry curricula and assessment methods, within the confines of each individual medical schools’ broader curriculum.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the support of each of the six universities in providing information regarding the delivery and assessment of psychiatry.

Financial Support

None.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors are involved in the delivery and assessment of psychiatry at undergraduate level in a medical school in Ireland.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of each participating institution. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients.