Introduction

Despite widespread recognition within the literature of the importance of early childhood experiences (Berry et al. Reference Berry, Barrowclough and Wearden2007), the impact of childhood experiences on adult psychopathology remains to be fully explored. Parental bonding, as conceptualised within an attachment theory framework, may provide a useful perspective to further our understanding of the complex relationship between childhood trauma and mental health outcomes.

In bipolar disorder (BD) studies childhood trauma rates are reportedly as high as 49% (Leverich et al. Reference Leverich, McElroy, Suppes, Keck, Denicoff, Nolen, Altshuler, Rush, Kupka, Frye, Autio and Post2002) and 51% (Garno et al. Reference Garno, Goldberg, Ramirez and Ritzler2005). A number of important reviews have been published in recent years (Varese et al. Reference Varese, Smeets, Drukker, Lieverse, Lataster, Viechtbauer, Read, van Os and Bentall2012), including two reviews of childhood trauma in BD (Etain et al. Reference Etain, Henry, Bellivier, Mathieu and Leboyer2008) and one review of the impact of child sexual abuse on the course of the disorder (Maniglio, Reference McIntyre, Soczynska, Mancini, Lam, Woldeyohannes, Moon, Konarski and Kennedy2013). Cotter et al. (Reference Cotter, Kaess and Yung2015) have demonstrated a negative impact of a history of childhood sexual abuse on adult outcomes in BD.

A few studies have explored the association between childhood trauma and outcomes in BD, concluding that a trauma history is associated with an earlier onset of illness (McIntyre et al. Reference Maguire, McCusker, Meenagh, Mulholland and Shannon2008), increased hospital admissions, higher levels of inter-episode depression (Maguire et al. Reference Maniglio2008; Mowlds et al. Reference Mowlds, Shannon, McCusker, Meenagh, Robinson, Wilson and Mulholland2010), faster cycling frequencies and an increased number of BD episodes (Nolen et al. Reference Nolen, Luckenbaugh, Altshuler, Suppes, McElroy, Frye, Kupka, Keck, Leverich and Post2004). Childhood trauma experiences have also been associated with increased rates of suicidal attempts (Brown et al. Reference Bowlby2005; McIntyre et al. Reference Maguire, McCusker, Meenagh, Mulholland and Shannon2008), auditory hallucinations (Hammersley et al. Reference Hammersley, Dias, Todd, Bowen-Jones, Reilly and Bentall2003), mania (Levitan et al. Reference Levitan, Parikh, Lesage, Hegadoren, Adams and Kennedy1998) and co-morbid alcohol and substance abuse (Leverich et al. Reference Leverich, McElroy, Suppes, Keck, Denicoff, Nolen, Altshuler, Rush, Kupka, Frye, Autio and Post2002; Brown et al. Reference Bowlby2005). Studies of individuals with depression have also shown similarly high rates of childhood trauma, namely physical and sexual abuse, and poorer parental relationships (Lizard et al. Reference Lizard, Klein, Ouimette, Riso, Anderson and Donaldson1995). Significant associations were found between a childhood trauma history and earlier onset (Kessler & Magee, Reference Klein1993) and increased depressive symptomology (Hammen, Reference Hammen1991). Despite this there is evidence that mental health services routinely neglect to enquire about traumatic experience (Shannon et al. Reference Shannon, Maguire, Anderson, Meenagh and Mulholland2011).

This study explores the impact of parental bonding [located within the attachment theoretical framework (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1969)] in an attempt to explore the underlying mechanisms which may account for an association between childhood trauma and poorer mental health outcomes. Bowlby (Reference Bowlby1979) proposed that attachments formed with primary caregivers in early childhood are of great importance throughout an individual’s life cycle. Based upon experiences of positive interactions with a primary caregiver, an individual will develop mental representations of the self in relation to others and form expectations of how others may behave within social relationships. These internal working models of relationships, developed as a result of early attachment experiences, can impact on an individual’s ability to form meaningful relationships in later adult life (Bowlby, Reference Brown, Mc Bride, Bauer and Willford1982). To date a limited number of studies have explored parental bonding experiences and mental health outcomes within adult psychopathology.

This study measures perceptions of parent–child interactions using the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) (Parker et al. Reference Parker1979). Studies which have explored parental bonding experiences using the PBI within a psychosis population found higher rates of poor parental bonding as shown by the ‘affectionless control’ category, when compared with non-clinical controls (Onstad et al. Reference Onstad, Skre, Torgersen and Kringlen1994; Winther Helgeland & Torgersen, Reference Winther Helgeland and Torgersen1997; Willinger et al. Reference Willinger, Heiden, Meszaros, Formann and Aschauer2002). Significant associations have also been found between the ‘affectionless control’ category and an earlier stage of initial hospitalisation, higher relapse rates (Parker et al. Reference Parker1982; Baker et al. Reference Baker, Helmes and Kazarian1984; Parker & Mater, Reference Parker, Fairley, Greenwood, Jurd and Silove1986) and poorer engagement with services (Tait et al. Reference Tait, Birchwood and Trower2004). There are few published studies in BD populations: Joyce (Reference Joyce1984) found higher rates of ‘affectionless control’ parenting style amongst females with BD and an association with an increase in hospital admissions. Poor parental bonding experiences have also been reported by depression population samples (Parker et al. Reference Parker1979; Parker, Reference Parker1983; Gotlib et al. Reference Goodman, Thompson, Weinfurt, Corl, Acker, Muser and Rosenberg1988). However, one study (Parker, Reference Parker1979) found no significant differences in parenting bonding experiences when comparing a BD, a depression and a control group. Studies to date have not included additional measures of childhood adversity, such as trauma, or have explored the impact on depressive symptomology and mental health outcomes.

This study aims to explore the relationship between childhood trauma, parental bonding, and the association with depressive symptomology and mental health outcomes, specifically interpersonal difficulties. Current depressive symptoms and interpersonal difficulties, that is, the ability to form close and meaningful relationships with others, are the most common complaints service users bring to therapy (Horowitz et al. Reference Horowitz, Rosenberg, Baer, Ureno and Villasenor1988). Research has shown that interpersonal problems can result in reduced coping strategies, reduced social supports and reduce the likelihood of recovery (Penn et al. Reference Penn, Corrigan, Bentall, Racenstein and Newman1997).

The following research hypotheses were proposed: (1) High prevalence rates of childhood trauma will present within the BD and depression groups. (2) Childhood trauma and poor parental bonding experiences will impact negatively on mental health outcomes on domains of (i) current inter-episode depressive mood and (ii) interpersonal functioning.

Methods

Participants

All patients with a confirmed diagnosis of BD or major depression living in a well-defined catchment area (population: 90 046) were considered for inclusion in the study. Inclusion criteria included a DSM-IV diagnosis of BD I or II, or Major Depression (American Psychiatric Association, Reference Ainsworth2000) by the agreement/consensus of two psychiatrists; aged 18 years or above and the ability to give informed consent. Exclusion criteria included: those patients currently judged to be too unwell to take part by the clinicians with whom they have regular contact; moderate-to-severe head injury; severe or poorly controlled medical conditions. Ethical approval for the current study was granted by a local research ethics committee. All participants gave written informed consent.

Individuals, who met the inclusion criteria were identified from the catchment area population through contact with a local outpatient service. Of those 99 individuals with BD invited to take part, 10 were excluded as they were experiencing a relapse of BD (hospitalised or under the care of a home treatment team) and judged to be to unwell to participate and 62 declined to take part. Data were thus collected from 27 participants; a recruitment rate of 27%. Of those 65 individuals with depression, 43 declined to take part, data were collected for 22 participants; a recruitment rate of 34%. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Participants (n=49) and non-participants (n=96) did not differ significantly in terms of age (t=0.23, df=143, p=0.818, n 2=0.001) or gender (χ 2 (1, n=145)=0.001, p=0.97, φ=0.003).

Measures

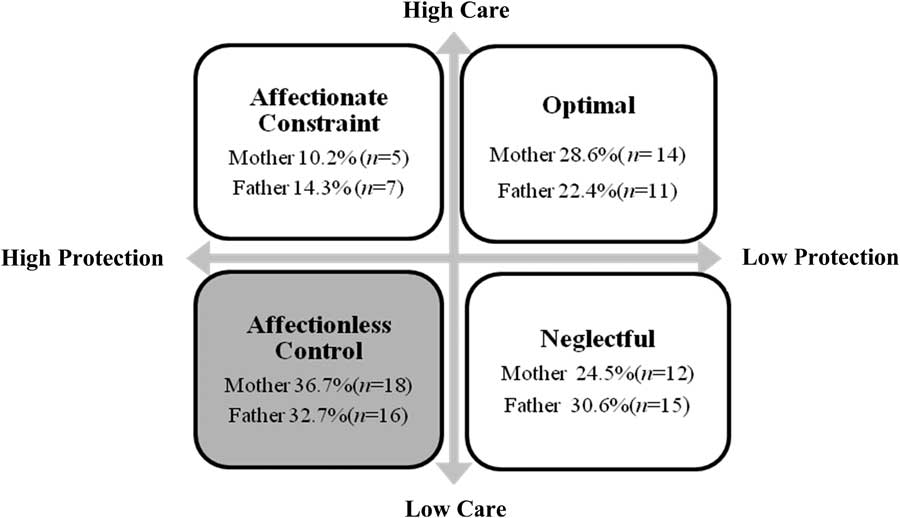

Demographic data were collected on age, gender, history of diagnosis and number of hospital admissions. The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) was administered (Bernstein & Fink, Reference Bernstein and Fink1998). The CTQ is a 28-item self-report measure of childhood abuse. Five clinical subscales include emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect and physical neglect each measured by five items. A further subscale measures minimisation and denial of trauma. Participants are asked to respond to the 28 statements on a five-point scale from ‘never true’ to ‘very often true’. Cut-off scores indicating none, mild, moderate or severe levels of abuse have been published (Bernstein et al. 1994). The CTQ has good internal consistency reliability coefficients and test-retest reliability coefficients range (Bernstein & Fink, Reference Bernstein and Fink1998). The PBI was utilised as a retrospective measure of perceptions of parent–child relationships, with both a mother and father caregiver, during the first 16 years of life (Parker et al. Reference Parker1979). The PBI measures levels of care and protection experienced. Dependent on participants’ scores on each of these two domains their parental bonding experience is assigned to one of four categories as follows: ‘affectionless control’, ‘affectionate constraint’, ‘optimal’ and ‘neglectful’. Psychometric studies have established that the PBI possesses adequate reliability and validity (Parker, Reference Parker and Mater1989, Reference Parker, Tupling and Brown1990).

Outcome measures

Current mood was assessed by using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck, 1996). The BDI is a 21-item self-report inventory measuring characteristics, attitudes and symptoms of depression. The measure has been extensively reviewed for its psychometric properties (Beck, 1996). Interpersonal functioning was assessed by administering the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems-32 (IIP-32) (Barkharm, Reference Barkharm1996). The IIP-32 has eight subscales: ‘domineering’, ‘vindictive’, ‘cold/distant’, ‘socially inhibited’, ‘non-assertive’, ‘overly accommodating’, ‘self-sacrificing’ and ‘intrusive/needy’. The internal consistency reliability co-efficient and test-retest reliability co-efficient are good (Barkharm, Reference Barkharm1996).

Statistical analysis

This was a quantitative study which used a cross-sectional retrospective design. Descriptive statistics were used to examine the prevalence of childhood trauma in the sample. Hierarchal multiple regression analyses were used to investigate the hypotheses that childhood trauma and parental bonding (predictor variables) were associated with poorer outcomes on current depressive mood and interpersonal difficulties (criterion variables). All independent variables which correlated with these outcome variables at a cut-off point of r=±0.25 were selected for inclusion in the subsequent hierarchal regression analyses. The order of entry of blocks of variables was

Step 1: group membership variable (diagnosis of BD or depression)

Step 2: childhood trauma history (CTQ) variables

Step 3: parental bonding (PBI) (mother/father) variables

Preliminary analyses were conducted to ensure no violation of normality, linearity, multicollinearity and homoscedasticity. There was no strong collinearity between predictors. In the models, the VIF values are all well below 10 and the tolerance statistics were all well above 0.2. Model fit for the multivariate analyses was assessed using the adjusted R 2 statistic.

Results

Demographic and psychiatric information

Table 1 contains demographic and psychiatric information for the BD and depression groups. In total, 31 participants (n=49) 63% of the total sample rated their current depressive mood on BDI within the ‘moderate-to-severe’ range.

Table 1 Demographic and psychiatric information for bipolar disorder and depression group

BDI, Beck Depression Inventory.

a Therapeutic support services included clinical psychology, counselling and cognitive behavioural therapy.

Childhood trauma prevalence rates

In total, 38 participants (77.4%) reported a history of childhood trauma. Childhood trauma experiences were compared using CTQ domains, individuals who had one or more scaled scores reaching moderate or severe levels on the CTQ are shown in Table 2. Of the total sample (n=49), 11 participants (22%) reported moderate or severe trauma levels in one category and 27 participants (55%) reported moderate or severe trauma in two or more categories. Individuals with BD or depression reported similarly high prevalence rates of childhood trauma across the different trauma subtypes.

Table 2 Childhood trauma prevalence rates across groups

BD, bipolar disorder; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire.

a CTQ overall percentages are based on endorsement of trauma in moderate-to-severe range on one or more of five subscales.

Parental bonding experiences

The following quadrant (Fig. 1) depicts the percentages of parental bonding styles reported by the group. ‘Affectionless Control’, characterised by ‘low’ care and ‘high’ protection (controlling) parenting style, was the most common parental bonding category for both mother and father caregivers.

Fig. 1 Parental bonding domains.

Impact of childhood trauma and parental bonding on depression symptomology and interpersonal functioning

Three significant hierarchal regression models are presented below. Additional regression analyses were completed but these models failed to reach significance; Cold/Distant subscale (R 2=0.219, adjusted R 2 0.107, df (6, 48); F=1.960, p=.093). Domineering/Controlling subscale (R 2=0.238, adjusted R 2 0.129, df (6, 48); F=2.182, p=0.064) and Self-Sacrificing subscale (R 2=0.297, adjusted R 2 0.196, df (6, 48); F=2.593, p=0.170).

Trauma, parental bonding and current inter-episode depressive mood

The final regression model accounted for 18% of the variance (adjusted R 2 0.187; step 3) in current inter-episode depressive mood (R 2=0.254, df (4, 48); F=3.758, p=0.010). Table 3 provides information for the predictor variables entered into the model. Regression analyses indicated that the diagnosis variable accounted for 0.1% of the variance in the current inter-episode depressive mood (step 1). Childhood trauma accounted for an additional 12% of the variance in the current inter-episode depressive symptoms (step 2). When the parental bonding (mother) category was added (step 3) the variance accounted for increased to 18%. The parental bonding (mother) category of ‘affectionless control’, was the strongest predictor variable (β 0.298, p=0.004) in the final model. Sexual abuse in childhood almost reached significance (β 0.262, p=0.067).

Table 3 Hierarchal regression analysis: childhood trauma, parental bonding and current inter-episode depressive symptoms

PBI, Parental Bonding Instrument.

***p<0.005.

Trauma, parental bonding and interpersonal problems: Socially Inhibited subscale

This final regression model accounted for 24% of the variance (adjusted R 2 0.244; step 3) in the Socially Inhibited subscale (R 2=0.338, df (6, 48); F=3.578, p=0.006). Table 4 provides information of the predictors variables entered into the model. Regression analyses indicated that the diagnosis variable accounted for 0.1% of the variance in the Socially Inhibited subscale (step 1). Childhood trauma accounted for an additional 10% of the variance in the Socially Inhibited subscale (step 2). When the parental bonding (mother) category was added (step 3) the variance accounted for increased to 24%. The strongest predictor variable within the model was the parental bonding (mother) category of ‘affectionless control’ (β 0.395, p=0.031).

Table 4 Hierarchal regression analysis: childhood trauma, parental bonding and Socially Inhibited subscale

PBI, Parental Bonding Instrument.

*p<0.05.

Trauma, parental bonding and interpersonal problems: Overly Accommodating subscale

This regression model (Table 5) accounted for 16% of the variance (adjusted R 2 0.169; step 3) in the Overly Accommodating subscale (R 2 0.255, df (5, 48); F=2.951, p=0.022). Table 5 provides information of the predictors variables entered into the model. Regression analyses indicated that the diagnosis variable accounted for 5% of the variance in the Overly Accommodating subscale (step 1). Childhood trauma (physical neglect) accounted for an additional 8% of the variance in the subscale (step 2). When the parental bonding (father) category was added (step 3) the variance accounted for increased to 16%. The parental bonding (father) category of ‘affectionless control’ was the strongest predictor in the final model and almost reached significance (β 0.375, p=0.07).

Table 5 Hierarchal regression analysis: childhood trauma, parental bonding and Overly Accommodating subscale

PBI, Parental Bonding Instrument.

Discussion

In summary, this study found high prevalence rates of childhood trauma amongst individuals with BD and depression. This is in keeping with previous research both in the same geographical area (Maguire et al. Reference Maniglio2008; Mowlds et al. Reference Mowlds, Shannon, McCusker, Meenagh, Robinson, Wilson and Mulholland2010) and elsewhere (Leverich et al. Reference Leverich, McElroy, Suppes, Keck, Denicoff, Nolen, Altshuler, Rush, Kupka, Frye, Autio and Post2002; Garno et al. Reference Garno, Goldberg, Ramirez and Ritzler2005; Moskvina et al. Reference Moskvina, Faremer, Swainson, O’Leary, Gunasinghe, Owen, Craddock, McGuffin and Korszun2007).

The parental bonding category of ‘affectionless control’, characterised by ‘low care and high protection’, was the most common parenting experience. The hypotheses that childhood trauma and poor parental bonding would negatively impact on mental health outcomes (as indexed by current depressive mood and interpersonal difficulties), was partially supported by the regression models (1–3). Parental bonding style of ‘affectionless control’ (from mother) was the strongest predictor of poorer outcomes for current depressive mood and interpersonal difficulties on the Socially Inhibited subscale of the PBI. The parental bonding style of ‘affectionless control’ (from father) was predictive of poorer outcomes on the Overly Accommodating subscale of the PBI. Although childhood trauma was an important contributory variable within the regression model, it was not as significant as parental bonding experiences when predicting poorer mental health outcomes.

Previous studies have demonstrated that individuals with a psychiatric diagnosis are more likely to categorise parent/child interactions within the ‘affectionless control’ domain (Parker et al. Reference Parker1979). Associations between poor parental bonding (affectionless control) and poorer mental health outcomes have been previously reported (Parker, Reference Parker1979; Parker et al. Reference Parker1982; Joyce, Reference Joyce1984). There are a number of theories which highlight the importance of early attachment relationships for later psychological development including attachment theory (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1979), object relations theories (Klein, Reference Kessler and Magee1952; Ainsworth, 1969) and cognitive theories (Beck, Reference Beck1967; Segal, Reference Segal1988).

This study found an association between poor parental bonding, childhood trauma and the later emergence of depressive symptomology. Cummings & Cicchetti (Reference Cummings and Cicchetti1990) suggest that for a child the experience of a parent who is psychologically unavailable is similar to experiencing the actual loss of a caregiver. Bowlby (Reference Bowlby1979, Reference Brown, Mc Bride, Bauer and Willford1982) suggests that feelings of inadequacy and hopelessness can develop, alongside a model of the self as a failure, following the perceived loss of a secure relationship in childhood. Additional adverse experiences, such as childhood trauma or subsequent loss, can reinforce this negative internal representation of the self. The lack of a secure emotional base for an individual may contribute to the development of an insecure attachment style, perceived vulnerability and a predisposition to depressive symptomology.

Childhood adversity experienced within close interpersonal relationships, may predispose an individual to developing beliefs about themselves as vulnerable and a view of the world as threatening. From a cognitive perspective, poor interactions with caregivers who are harsh, overly critical or neglectful, may contribute to the development of negative core schema and thus form the basis for later negative information processing regarding self and others, for example, perceiving others to be emotionally unavailable, hostile or rejecting (Segal, Reference Segal1988). This may account for the relationship found between poor parenting styles, trauma and high levels of current inter-episode mood reported in the current study.

Experiences of childhood trauma and poor parental bonding were also predictive of interpersonal difficulties shown on the Socially Inhibited and Overly Accommodating subscales. Interpersonal difficulties are often associated with high relapse rates and poor recovery rates through a negative impact on social relationships, support networks and coping strategies (Dilillo, Reference Dilillo2001; Platts et al. Reference Platts, Tyson and Mason2002; Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Hammen, Henry and Shannon2004). This may help to explain why childhood trauma survivors often experience poorer clinical outcomes and are at increased risk of relapse and reduced recovery from psychiatric illness. The Socially Inhibited subscale is characterised by a pervasive pattern of detachment from close or social relationships in adulthood. Poor parental relationships may create internal working models of self (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1979) as unlovable and of others as emotionally unavailable or overly critical. Individuals who are socially inhibited may choose to limit their social interactions with others, leading to reduced support and further isolation.

The findings of this study highlight the need for clinicians to routinely enquire about childhood trauma experiences, independent of psychiatric diagnosis. Read et al. (2007) found that amongst clinicians there is a reluctance to enquire about trauma due to fears of vicarious re-traumatisation, feelings of incompetence and anxiety regarding upsetting or distressing the client. Training for clinicians on the assessment of trauma and on evidence-based therapeutic interventions could help promote feelings of professional competency amongst clinicians (Read, Reference Read, Hammersley and Rudegeair2006).

These findings highlight the need to consider parental bonding, alongside childhood trauma experiences, when exploring childhood adversity within adult psychopathology. An individual’s parental bonding experience may impact on their willingness to engage in treatment or their capacity to form a working alliance or attachment with a therapist. Dozier (Reference Dozier1990) suggests individuals with a secure attachment style present as more comfortable-seeking therapy and able to commit to the process. Insecurely attached individuals may find it difficult to utilise therapy appropriately, experience feelings of denial or feelings neediness and dependency can emerge which may make it difficult for them to use the therapist productively (Dozier, Reference Dozier1990). A recent systematic review in psychosis populations examined the association between attachment styles and engagement with mental health services and trauma and demonstrates similar results (Gumley et al. Reference Gumley, Taylor, Schwannauer and MacBeth2014).

A psychological formulation can help normalise and conceptualise psychosocial experiences and later psychopathology within a developmental vulnerability framework. For those individuals having grown up within a dysfunctional family system, with poor parental bonding and trauma experiences, this can often result in inadequate exposure to effective parenting models (Dilillo et al. Reference Dilillo, Tremblay and Peterson2000). These experiences can directly or indirectly impact on an individual’s own parenting style or caregiving towards their own children. For clinicians, it is important to be mindful of wider systemic issues such as family and childcare, and liaise with appropriate early family intervention support services, thus helping to further prevent trans-generational patterns of poor parenting styles and trauma.

Limitations to the current study are apparent. First, adverse childhood experiences can be emotionally difficult to recall and often the disclosure of sensitive information is dependent on rapport building and the development of a therapeutic alliance with an interviewer. It is also likely that the depth of these childhood experiences cannot be fully assessed during one assessment interview. Self-report instruments (CTQ, PBI) were used to assess for the presence of childhood adversity. These are based on retrospective recall and can be subject to errors which can lead to an under reporting or over reporting of information. However, previous studies have demonstrated good self-report reliability with regards trauma histories amongst those with mental health difficulties (Goodman et al. Reference Gotlib, Mount, Cordy and Whiffen1999; Fisher & Hosang, Reference Fisher and Hosang2010). The sample size is relatively small, though sufficient to detect real differences (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988), and the fact that the recruitment process took place through an outpatient clinic may have introduced a sampling bias These individuals may have experienced more severe forms of childhood adversity, and be less well-adjusted interpersonally, than those in the general population who have been traumatised but have not come into contact with psychiatric services. In addition, the exclusion of individuals who were deemed to be clinically unstable means that the sample may have been biased against more severely ill individuals. The current findings are limited therefore to understanding the experiences of those with BD or depression, who are actively engaged with psychiatric services.

Conclusions

To conclude, this study extends upon the findings of previous research by exploring the complex relationship between childhood trauma and mental health outcomes, through the unique pathway of parental bonding experience. In this model, the poor parental bonding (mother) category of ‘affectionless control’ was an important contributing factor alongside childhood trauma, which predicted poorer outcomes within BD and depression. Overall, these findings help to contribute to an understanding of possible pathways to adult psychopathology theoretically informed by attachment theory.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of each participating institution. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.