While trying to solve a murder in Chipping Cleghorn, one of Agatha Christie's characters made a throw-away remark: ‘After all, if he wanted to take a pot shot at Aunt Letty … He could have shot her from behind a hedge in the good old Irish fashion any day of the week, and probably got away with it.’Footnote 1 Without any elaboration Christie took for granted that the very many readers around the world of her 1950 novel, A murder is announced, knew exactly what killing in ‘the good old Irish fashion’ amounted to, that even after almost thirty years there was still no need to explain what she might have meant. But by 1950 Christie was simply drawing on a quite familiar trope. Her contemporary, Eric Ambler, gave one of his most sadistic characters, Captain Mailler, an Irish past as a Black and Tan so readers could be sure of what a brutal, callous sort he really was.Footnote 2 Across the Atlantic, Raymond Chandler conjured up ‘a big curly-headed Irishman from Clonmel’ in Rusty Regan, and though he made him ‘an adventurer who happened to get himself wrapped up in some velvet’, it was Tipperary not Los Angeles that had made him tough.Footnote 3 Although the patter was different, Chandler drew upon the same assumptions as his British counterparts: that the ‘Irish troubles’ were a sequence of dirty wars, and so familiar as such to his readers that he did not need to waste another sentence to explain. Although other authors may have been more subtle in their portrayals, the global reach of these writers is a crude measure of the type of ‘Irish troubles’ that resonated in the popular culture of the 1930s, 1940s and beyond. Ireland, it seems, had its own brand of ‘trouble’, recognisable for the traits and mannerisms of its violence, just as Chicago had its gun-toting gangsters and Corsica its vendettas and its knives.

Much of this reputation was a product of the period's own propaganda. The idea that there was an Irish type of violence and that it was inherently disreputable, unprincipled, and contrary to the rules of war, courses through the reports, the letters, the mixum-gatherum of memoirs and unguarded exchanges of many British administrators and politicians, and of more of the Crown forces who served in Ireland and left all sorts of disparate reminiscences behind. In precisely the same way British violence in Ireland took on equally pernicious characteristics for Irish republicans. British, or often just English, perfidy came in the shape of ‘drunken Tans’ and dastardly Auxiliaries, cold-hearted creatures jaded into villainy by the Great War, who did unspeakable wrongs to Irish patriots, who brutalised noble Irish women and terrorised the innocent in their beds with raids and reprisals of every appalling manner and sort. And the same characterisations came readily to hand in civil war. Black and Tans gave way to ‘Green and Tans’, and ‘murder gang’ could be as venomously said of opponents in 1923 as it ever was in 1921. Within a year of it all, by 1924, while P. S. O'Hegarty already rued that ‘we glorified ambushes and “stunts” and “jobs” and secret executions without trial’, Dan Breen recounted the revolution as a sequence of scrapes and escapades to make ‘a Wild West show … grow pale’.Footnote 4 And when one book reviewer in 1938 wrote with a giddy fondness for the heroics of what he termed the ‘.45 period in Ireland’ it was clear that, of the two, Breen had struck the more popular chord.Footnote 5 But for all this, for all the very different versions of the ‘fighting story’ since, even for all the restless worrying away at ‘who shot who in Cork’, relative to other parts of Europe, Ireland at war was not a very violent place.Footnote 6

I

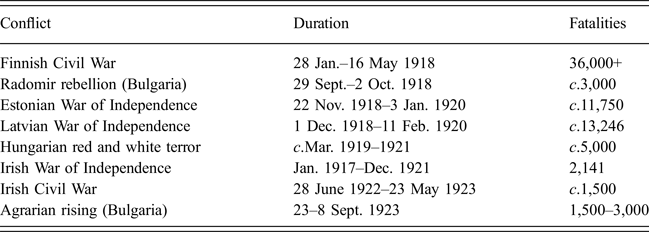

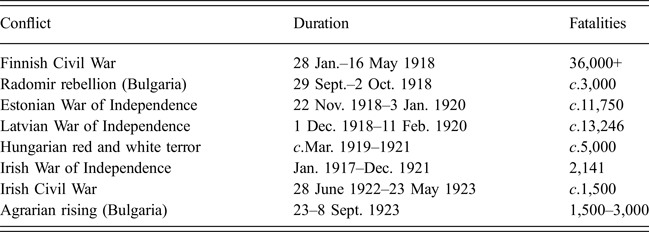

If violence in Ireland had acquired a reputation, it was because of its nature not because of its extent. Recent scholarship accepts that Ireland's wars were not as lethal as they might have been, that the numbers of displaced people north and south ‘may be trivial in comparison with the massive dislocation of peoples’ in continental Europe, and that so much of what happened in Ireland between 1919 and 1923 could have been infinitely worse.Footnote 7 Although fatalities escalated over 1921, although there were ‘local spirals of violence and counter-violence’, across a range of comparative studies, it has become clear that Ireland ‘was no Bosnia’, no Finland, no Upper Silesia.Footnote 9 And if levels of lethal violence are what have prompted these conclusions then a table of fatalities, such as this one, just drives home the point.

Table 1. Estimated fatalities in a sample of contemporary conflicts.Footnote 8

But such a table is a blunt and awkward instrument. Quite apart from the obvious caveats about how accurate the figures for fatalities might be, is lethal violence even the best measure to apply, particularly when, through most of the fighting in Ireland, what Stathis Kalyvas might call ‘successful terror’ actually ‘implie[d] low levels of violence’, and often needed few to be killed to have its message heeded as well as heard?Footnote 10 Does such a table reduce Ireland to some sort of revolutionary also-ran or does it tempt a kind of crowing condescension that maybe there was ‘something in us finer than, more spiritual than, anything in any other people’ after all when it came to the savagery of war?Footnote 11 Does it imply a hierarchy of loss when the loss of a son or daughter is as deeply felt in Tipperary as it is in Helsinki, when loss is simply loss regardless of the sum of death it ends up contributing to? There are, of course, other quandaries with a table such as this, not least because it prompts the obvious questions ahead of the harder ones. And while the obvious ones do need to be addressed – why was war in Ireland different, not so violent; what was it about its nature that sets it seemingly apart? – the harder ones might be more awkward but important to ask. Despite the disparities of scale what did Ireland's wars still share with other conflicts? Is violence, irrespective of numbers killed, fundamentally the same, or were Christie and Chandler right after their own lights – does the nature of violence shape our understanding of a conflict far more than a table like this one ever could?

II

Tackling these questions might be the work of many articles rather than one, and all sorts of other approaches may turn out to be more fruitful and more apt. Indeed, this type of table serves as a reminder that there is more work to be done at home as well as drawing on contrasts and comparisons from further afield. For example, studies of late nineteenth-century homicide, particularly Carolyn Conley's figures for 1866 to 1892, suggest Cork was the most lethal county in Ireland, so would comparisons back across the Land War, the Tithe War, 1798, moving diachronically rather than internationally, prove as rewarding as pointing out why Ireland and Finland are similar but very different all the same?Footnote 12 David Fitzpatrick's maps showing that ‘the distribution of agrarian outrages in the Land War is distinctly correlated with the pattern of revolutionary violence perpetrated by the I.R.A. in 1920–21’, suggests this might be so, and that there is more to be lost than gained from settling for 1912, 1916 or 1919 as some sort of distinct revolutionary ‘year 1’.Footnote 13

But for all that seems local about this point, there is nothing peculiarly Irish about it either. Ariane Chebel d'Appollonia, examining five centuries of political and religious violence in France, has traced out the patterns of inherited repertoires of violence, observed their capacity to survive and adapt to new demands and circumstance.Footnote 14 And there is nothing unique in this to France. Charles Tilly and Sidney Tarrow sought out the same lineages of ‘contentious politics’ from eighteenth-century England to twenty-first century Ukraine, so while each region, country or polity grapples with the specificities of its own inheritance, they all share the burden of the bequest.Footnote 15 Such studies across centuries show the limits of simply searching for similarity in the inter-war period alone, that there are benefits of moving far beyond the obvious places as suggested by period and scale that usually leave Ireland stuck rather awkwardly between Finland (too extreme) and Denmark (too sedate) with nowhere of equivalent size or population ‘just right’. And it was an impulse that even made sense in 1924. Nevil Macready, the General Officer Commanding in Ireland, compared Bloody Sunday morning's killings to 1572's St Bartholomew's Day massacre. While it is ludicrous in terms of scale, while he may have made the comparison solely for the shock of the association for his readers, it still makes a type of sense in terms of the nature and the context of the violence as Macready saw it.Footnote 16 Men dragged from their beds in front of their families was what brought St Bartholomew's Day to mind.

Macready's choice of sixteenth-century France may have been more perceptive than he could have imagined. The French wars of religion have prompted some of the most influential scholarship on the history of violence, but its resonance here is not just in terms of approach.Footnote 17 While it might feel strained to press Natalie Zemon Davis's reading of the river as ‘a kind of holy water’ to wash ‘so many Protestant corpses’ clean of their sins on the Longford Brigade's explanation for dumping the body of John McNamee in the Shannon so as to save his children the shame of their father's death as a spy, there is common ground in spite of the nearly four centuries in between.Footnote 18 Indeed, there is no reason why diachronic comparisons cannot range far and experimentally wide. For example, Zemon Davis found that killing certain people in the sixteenth century needed far less explanation than killing others.Footnote 19 Alain Corbin found the same suspicion of those on the ‘outside’ in a French village in 1870, just as Peter Hart found distrust of those on the margins in Cork.Footnote 20 When Maurice Lane discovered a body on the road he said ‘I shouted for assistance … but no one answered’. Lane was a stranger to Carrigtohill; he drove the Sunday mail car from Cork to Middleton, so he was not to know who was or was not isolated on the edges of that place.Footnote 21 ‘Vermin’, ‘devil’, ‘tinker’, ‘drunk’, ‘tramp’, ‘spy’: ‘one of “them” rather than one of “us”’ sounded much the same whether it was 1572 or 1921, whether it was France or Cork.Footnote 22

At the inquiry into William Charters's death the Reverend Henry Johnston of Ballinalee admitted he was afraid because murder had ‘been committed in the midst of his parish and it might be anyone's turn next’.Footnote 23 When the labelled body of Crosby Boyle was found on the ‘public road’ near Killusty, ‘much alarm prevailed’, ‘several people left their houses’.Footnote 24 From the I.R.A.'s perspective this was precisely how Reverend Johnston, how the people of Killusty were supposed to feel; this was what this violence was supposed to do. It reinforced divisions, it isolated communities, it bred the fear of being taken from your bed by men in the night to be found dead in a ditch with the mark of a spy. But for all that the history of the Irish Revolution has seen such killing as central to the violence that marked out the period since, there was nothing new in the use of violence to convey a message, to control. Kalyvas has traced this type of violence that at once punishes and deters from Nicaragua in the 1920s to Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Sierra Leone, to Vietnam where labels were pinned to the bodies of dead Vietcong, where two villagers might be shot for collaborating with the Americans to keep the rest of the village ‘right’.Footnote 25 But this was the same as Zemon Davis's ‘defined targets’, the same as the selection D. M. G. Sutherland found of ‘a single victim’ in the midst of the September Massacres of 1792, the same ‘post-mortem display’ of bodies, the same acts ‘calculated to degrade’, to make the family bear the ‘stigma’ of the dead man's shame.Footnote 26 When Frank Sullivan's labelled body was found in Rosscarbery in July 1921, his sister tore up the label pinned to her brother's coat; if it was never found, it never was, and neither he nor she had to bear the mark of it.Footnote 27 She understood what her brother's killers meant; she read the nature of his death for what it was, just as many others in many other places before and after her would.

III

If Ireland knew the same types of ‘selective violence’ of other periods and places, if it shared many other things, not least the same sense of impropriety about murder in ‘broad daylight’ Corbin found in nineteenth-century France, or the same dread of what might come in the night Richard Cobb discovered in revolutionary Paris a century before, it also shared the importance of the local that drives Kalyvas's ‘logic of violence’ not just in civil war Greece, but, as he argues, from the English Civil War to the war in Afghanistan.Footnote 28 While Zemon Davis concluded that perpetrators of violence acted according to ‘the roles and patterns of behaviour allowed by their culture’, Kalyvas argues for greater emphasis on the interaction between the political and the private, the local and the national, for more account to be taken of ‘private conflicts’ to understand why most wars bring their own equivalent of his villages Manesi and Gerbesi, just miles apart and similar ‘in every observable aspect’, but one complicit in the ‘vicious massacre of five village families’ and one not.Footnote 29 Whether it was ‘the persistence of local structures and rivalries’ throughout civil war in England,Footnote 30 or the ‘genocidaires’ in Rwanda who themselves emphasised ‘the significance of local, micro-dynamics for killings’ in the midst of so much death,Footnote 31 whether it is the Irish examples Kalyvas cites, the Manahanites against the Hanniganites in Limerick, the Sweeneys and the O'Donnells in Donegal, the Brennans and the Barretts in Clare, the same instincts emerge.Footnote 32 ‘Villagers did not simply have politics thrust upon them; rather they appropriated politics and used them for their own purposes’. This was written of civil war in Sri Lanka, but could arguably apply just as well to Limerick and Donegal and Clare.Footnote 33 If it is accepted that there were clear civil war elements throughout all the violence of 1919 to 1923, then Ireland in that period shares the same dynamics of violence that come from the tensions and interactions between the ‘local cleavage’ and the ‘central cleavage’, or in slightly more amenable terms, the very many unclear and layered-upon reasons why some people kill and others do not when the opportunity to fight comes so close to home.Footnote 34 In Omarska camp in Bosnia in the early 1990s ‘a Serb guard came in the night and insulted a prisoner who, as a judge, had fined him for a traffic offence in the late 1970s’.Footnote 35 In an ambush at Tourmakeady, one I.R.A. man took his opportunity to take his revenge. Standing over a prone and injured R.I.C. man, he reportedly sent that policeman to his death with ‘You summoned me for a light once, Regan’, and fired.Footnote 36 Ireland's wars came of the same mess of reasons found in every other place.

There are, of course, many other common things. The British soldiers who admitted a preference for ‘the War to civil duties in Ireland’ because ‘in war one does know roughly where the enemy is’ were no different to the U.S. marines in Nicaragua in 1927, who could not ‘distinguish between rebel sympathizers, supporters, and soldiers’ or the ‘blind giant’ of the American army ‘powerful enough to destroy the enemy, but unable to find him’ in the Philippines from 1899 to 1902.Footnote 37 Just as the ‘French destroy at random because they don't have the necessary information’ in Indochina, British violence could be indiscriminate: ‘our men don't know friends from enemies, there are no rules of warfare, consequently they take justice into their own hands’; ‘they seemed to make a habit of breaking out … and killing men they thought were suspect rebels’, lost in the same ways without a clear ‘frontier’.Footnote 38

And men got lost in the same ways afterwards too. Like those who brought their wars home with them, whether from Flanders or Anzio or Vietnam, Ireland's wars left the same scars. In 1937 James Norton submitted an assessment of his own health in his application for a disability pension. Describing himself in the third person, he wrote:

As a result of his experiences on active service, culminating in the events of Bloody Sunday 21st November 1920, in which applicant was personally responsible as one of the firing party for the shooting of three British Intelligence Officers, two of which were killed, & one seriously wounded in the presence of their screaming wives & children. The applicant's mental condition showed gradual deterioration during the months following until complete mental breakdown was reached in July 1921.Footnote 39

Two years later he reported: ‘I have been in and out of Grangegorman hospital very often since’, that ‘I was advised to go to England for a complete change’, where he suffered what he termed ‘a complete breakdown’ there.Footnote 40 The phrase ‘in and out of Grangegorman’ did poor justice to his claim.Footnote 41 He spent most of the rest of his life there, where he died in his seventies in December 1974.Footnote 42 While records such as these allow some of the effects of this type of war to be found, they draw attention to the hardest cases most of all. After every other war in every other place those who went home to whatever amounted to normality leave far less trace behind. It was the same for the veterans of Ireland's wars, with lives maybe lived with all sorts of traumas buried and well-hidden or lives simply lived with no trauma there at all.

When they did tell of their wars, Ireland's veterans told in much the same ways. Like the French veterans of Algeria who would only tell of their comrades’ violence not their own, Charles Dalton spoke of Liam Tobin's nerves, Harry Colley told of Dalton's drinking.Footnote 43 Similarly, the silences and the euphemisms were the same. Like the Israeli soldiers who struggled to tell the heroic stories so central ‘to the myth of creating a new nation’,Footnote 44 there was Con Kearney of the East Limerick Flying Column who became increasingly reticent because ‘I remember those times with a feeling of aversion and self-disgust which increases as the years go by’.Footnote 45 As elsewhere, there were others who spoke, but there were always certain words they would never bring themselves to say. As more military service pension applications emerge there is the same sense that Samuel Hynes found among the veterans of the Second World War, of Vietnam, that war meant ‘that for once he need not be simply a man mending shoes in Soho’, that after it was over life was never going to be ‘so simple … so exciting’ ever again.Footnote 46 Throughout Joe Dolan's pension application there is the same stunned sense that Hynes found among American soldiers that his youthful war might have been his best of times and that the cares and costs of getting by were as crushing and as mundane as if he had never been a colonel or a general by the age of twenty-three.Footnote 47 Having gone from a clerk working for Kennedy's Bakery to an officer in the I.R.A. well known enough by his reputation not to seemingly need a rank (as one referee wrote ‘It was not known what his rank was he was always known as Joe Dolan’ and that seemed enough), having been described as ‘one of the most trusted of the late Gen[eral] Collins’ intelligence staff’, he was, by 1924, just a temporary messenger in the Department of Local Government, having left the army in the mutiny's disgrace.Footnote 48 Years of moving round dingy addresses, there were long spells of unemployment and just odd and infrequent jobs.Footnote 49 And maybe as he delivered messages and as a porter opened doors for people who just passed him by, he may well have felt the same anger and frustration found by Hynes.

For all these and for the many other ways that Ireland's wars were similar, the disparity of scale becomes more striking still. It might be enough to look to the broader decline of violence in nineteenth-century Ireland, or the flourishing of a political culture, and a ‘more permissive’ one ‘than existed in contemporary continental Europe’, that continued to absorb many in the republican movement even when violence was at its most intense.Footnote 50 It could have been because there were many other ways to fight: with strikes, with protests inside and outside prisons, by giving money, by not paying rates, by contesting and disrupting as an end in itself. Equally, the Dáil courts might share the burden, intervening with some form of justice to temper the vengeance of new and old disputes. But in this there was nothing new. The Irish were seemingly slow to embrace ‘the secret society model of revolutionary organization, with the foundation of the I.R.B. coming “a full one or two generations”’ behind those in other European countries. Hart has argued that there was ‘comparatively little revolutionary violence in nineteenth-century Ireland: no tradition of communes, few urban revolutionary ghettoes, and above all no barricades’, and then, just as in the twentieth century, there were always other possible forms of protest short of violence.Footnote 51 The fact that ‘the violent elite was atypical of the “nation” as a whole’ might explain it, or maybe just the realisation of what was at stake as the numbers ‘shrank steadily’ when drilling turned to arms raids, when watching and warning turned to shooting and no going back.Footnote 52

Land might explain it too, or more accurately the changes in land ownership that had taken place across the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. A small farmer was able to speak in the mid-1920s of ‘what had been gained by the land-revolution – what had been gained by the political revolution had not yet come into his consciousness’, but he saw them as distinct and separate things nonetheless.Footnote 53 While an unsatisfied hunger for land may have moved some to fight or some to see independence in terms of grabbing back the land of their dispossessed relatives of generations before, this was a radicalism born of a rather modest ambition when seen in the context of land in contemporary Bulgarian politics.Footnote 54 Overthrown prime minister, Alexander Stambolijski, was not only murdered by his opponents in June 1923, but his severed head was then ‘sent back to Sofia in a large biscuit box’. An ‘agrarian rising’ by Stambolijski's supporters in response left between 1,500 and 3,000 dead in just six days.Footnote 55 Land may have mobilised individuals to kill for their own cause in Ireland, the ‘land for the people’ might have been promised and even believed by more, but too many had already got enough of what they wanted for land to have made Ireland a much more violent place.

IV

Of course, it may have been more abstract than that; Ireland was in a different ‘zone of violence’, not part of the ‘culture of defeat’ after the Great War, not marked out by the type of ethnic and religious tensions that ‘served as a catalyst for “ultra-violence”’ in other parts of Europe at the same time.Footnote 56 Although sectarianism when it arose both north and south saw some of the island's most extreme violence, partition did not bring the intense communal violence it could have. Partition left no ‘bleeding frontier’ as in Germany's east, did not incite ‘waves of violence’, did not leave the island ‘without order or clear state authority’ on the scale experienced by Europe's post-war ‘shatter zones’.Footnote 57 According to such classifications Britain belongs to the ‘cultures of victory’; the helpful ‘minus Ireland’ in parenthesis that sometimes follows Britain's inclusion gives some sense of how Ireland's violence was shocking if taken solely within a British context (or at least in a British Isles context for even extra parenthesis).Footnote 58 Although an Emergency Powers Act in 1920 had authorised the use of troops to protect food and fuel in Britain, although 85 million working days were lost to strikes in 1921, all this and Ireland happened against, what Pugh calls, ‘a strong tradition that regarded political violence as essentially alien to British society’.Footnote 59 British press coverage of Ireland, not least the mounting list of disorder of the Manchester Guardian’s ‘The week in Ireland’ column, brought details of individual lives lost where deaths were just broad numbers when it was India or Egypt or Mesopotamia.Footnote 60 Barriers erected in Downing Street, protective officers to guard the cabinet, the assassination of Sir Henry Wilson at Eaton Place, Ireland was home in ways that those faraway places were only ever empire.

If proximity was a tempering factor, the wider ‘British world’ mattered too.Footnote 61 Throughout Sir Henry Wilson's diaries the demands of that world dictated who went and who stayed in Ireland, what they did there and for how long. ‘England to look after, and Egypt and Mesopotamia and India and Constantinople’, and that was just the entry for 10 May 1920.Footnote 62 Throughout 1920–1 British soldiers inconsistently came and went. While many were veterans of some of the worst of the war, and while a case could be made for how this may well have contributed to their propensity to use violence in Ireland, account needs also to be taken of a much more complex make-up of the British army there than that. In January 1922 the India Office admitted ‘that the majority of the troops in Ireland are boys under 19 years of age, or with less than 6 months service and not therefore qualified to go to India’, so they were not all hardened, brutalised warriors worn down by war. Wilson referred to them as ‘wholly untrained raw children’.Footnote 63 Whether this inexperience made them more intent on making their mark or less inclined to fire a shot, they made up mixed and constantly moving groups of men who were further undermined as a coherent force by their use for policing duties alongside R.I.C. and Auxiliaries and Black and Tans. British troops in Ireland were on a war footing for the purposes of discipline and punishment, but they were on peacetime pay, privileges and allowances, because ‘you do not declare war against rebels’ as Lloyd George said.Footnote 64 Stretched further by the imposition of martial law across many counties in December 1920, the fervour for the fight might well have dimmed. And many felt themselves restrained by ‘the frocks’, by the government, by the fear of public opinion among the politicians who would not let them loose.Footnote 65 Bernard Law Montgomery, stationed in Cork, admitted ‘that to win a war of that sort you must be ruthless; Oliver Cromwell, or the Germans, would have settled it in a very short time. Now-a-days public opinion precludes such methods.’Footnote 66 One Black and Tan, Douglas V. Duff, insisted that

given a free hand we could have restored order in Ireland in a month, even if it had been Peace of a Roman style, the kind that required the making of a desolation. But egged on to be brutal and tyrannizing one day, imprisoned and dismissed the service the next if we dared to speak roughly to our enemies, it is no wonder that the heart was taken out of the men and that most of us merely soldiered for our pay.Footnote 67

While some echoed the commitment of Sir Henry Wilson to Ireland's part in the empire or that in fighting for Ireland he was ‘fighting New York and Cairo and Calcutta and Moscow’, that he was fighting anarchy and Bolshevism in Ireland just as he was fighting anarchy and Bolshevism on the Liverpool docks or in the Lancashire mines, more crown forces, it would seem from their testimony, believed in little more than serving their time, malingering or making the most of what was just another posting away from home.Footnote 68 The broader lack of an obvious ideological commitment on the part of many soldiers, Auxiliaries, and Black and Tans is in direct contrast to many of Europe's paramilitaries at the time. While the statement that ‘we were mercenary soldiers fighting for our pay, not patriots willing and anxious to die for our country; most of us had been that already in a far more important “scrap”, and had seen exactly how much that sort of thing was appreciated by the people at home’ may have summed up feelings particular to just one Black and Tan, that type of indifference and ideological incoherence set them apart from many on the continent.Footnote 69 Ireland lacked Europe's ‘white armies’ and ‘red terror’; there were too many like Ernest Lycette who just opted for the Auxiliaries over the Staffordshire pits.Footnote 70 Intense communal divisions may well explain why Belfast ‘was, in per capita terms, the most violent place in Ireland’; F. A. S. Clarke of the Essex Regiment remembered Belfast as worse than Cork, that ‘both sides were attacking us’, so ‘we soon started to fire back’. Equally offended by ‘Shinners’ and the ‘insults by “loyal” civilians”’, his chief priority was to leave ‘the slummy streets of Belfast’ far behind.Footnote 71 But while Clarke was entirely at odds with those around him, there were other British soldiers more troubled by all they shared. J. M. Rymer-Jones realised it in the middle of a raid when he found himself in the home of a man he went over the top with at Passchendaele.Footnote 72 For G. W. Albin the war was simpler than that: ‘all I know was that in 1915 I was soldiering with Irishmen’, and he had no desire to fight them in 1921 in Athenry.Footnote 73 There were all sorts of reasons why Ireland was never as lethal as it might have been.

C. H. Foulkes, who had soldiered with the British army in Sierra Leone, South Africa, Nigeria, and the Western Front, long before he came to Dublin as director of Irish propaganda in Dublin Castle in 1921, suggested at least two others in his handbill appealing ‘to members of the I.R.A.’. He spoke directly to a shared idea of soldierly propriety, and he did it through the prism of race. Telling young I.R.A. men that they needed to behave like proper soldiers, he explained what a real soldier was: ‘They must wear a distinctive sign or uniform RECOGNISABLE AT A DISTANCE. They must carry arms OPENLY. They must conduct their operations in accordance with the Laws and customs of war.’ To reinforce his already emphatic capitalised points, he reminded his readers that ‘these Laws and customs of war were not drawn up by England for the purpose of fighting the I.R.A. They were drawn up by all the great nations including America, in order that war between white men should be carried out in a sportsmanlike manner, and not like fights between savage tribes.’Footnote 74 While Foulkes's distinctions might say much about his own prejudices, his own time in Africa, they may also explain something of why Ireland saw nothing of the scale of Amritsar, was never bombed from the air by the British as Mesopotamia was. While comparisons with Indian nationalists have been sought and clearly found, while Breen's and Barry's memoirs may well have inspired rebellion in Burma and Bengal, the Irish War of Independence was arguably not so violent because it was not conceived by many who fought it on the British side as a colonial conflict, however much post-colonialists might wish it so.Footnote 75 Although the Morning Post and many British politicians went on to mention Ireland and Egypt and Mesopotamia in the same breath, Ireland was too close to home; it had its own M.P.s, was part of the kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, but it was also too white and too English-speaking to warrant a much more violent war. Plans, drawn up for the British government, which may have amounted to little more than possible approaches if the truce broke down, did involve schemes to round men up across the country, and to bomb Irish towns from the air.Footnote 76 General Sir Henry Rawlinson, Commander-in-Chief in India, admitted in August 1921 that if the fighting resumed ‘we shall have to do to Southern Ireland what we did to South Africa – barbed wire, blockhouses, drives, concentration camps, and the sweeping up of the population’. He contemplated sending I.R.A. men ‘to the Falkland islands or the “Ile de diable”’; it had clearly been conceived as a white man's war up to that point.Footnote 77

Even republican propaganda acknowledged it as such and saw a way to capitalise on this as early as 1919. Contrasting the use of aerial bombing in Egypt with British reticence ‘to drop bombs on the Irish villages’, one pamphlet concluded ‘the reason [is] that the Green Island is occupying the attention of the United States and has become an international problem’.Footnote 78 With the outside world looking on, the competition for the high moral ground prompted an economy of violence, particularly for the key peacemakers at Versailles. While some concerns were more parochial, such as ‘who is going to pay for all the acts of violence … presumably the ordinary English, Scotch & Welsh taxpayers!’, others looked at Ireland through this broader lens.Footnote 79 Perhaps conscious of the reach of republican propaganda, even the prospect of peace negotiations was enough for Lord Derby to ‘put ourselves right in the eyes of the whole world, and especially America’, and in 1921 that counted for an awful lot to a government saddled with such immense war debt.Footnote 80 As the months wore on even ‘a war between white men’ came at too high a cost.

But Foulkes's wider message about soldierly behaviour is a much broader and maybe more important one. While there were practical reasons why the I.R.A. was perhaps not as lethal as it might have been, with Micheál Ó Suilleabháin with a shotgun kept together with an elastic cord, or the ‘average man’ in one Monaghan company only ‘out two nights every week’, these and more have to be weighed against the very point on which Foulkes was trying to hold the I.R.A. to account.Footnote 81 For his accusations to resonate, for the words murderer and gunman to prod where prodding hurt, there was an implicit acknowledgement that there were rules, accepted ways and means to fight, and that there were types of victims, types of violence, that could not with good conscience be passed off as war. The insistence that guns had to be their weapon of war, even when stabbing or beating or bludgeoning to death might have been more pragmatic or easier to carry off, suggests just how much the influence of the wider culture of war had affected these men. The lines when crossed that made a murderer of a soldier or turned a policeman into a thug, implied that there were notions of propriety to uphold, and those lines were drawn as sharply in America or in Europe as they were in Tuam or in Tunbridge Wells. Indeed the starkness of those lines prompted de Valera's pleas home from the United States to stop shooting policemen coming out of mass, explained the insistence on the legitimacy of what was done, or why in old age Seamus Robinson objected so vehemently to the I.R.A. being called so benign a word as ‘group’ ‘as if we were a gang of hoodlums instead of a disciplined army’.Footnote 82 There was a transnational understanding of what it was to be a soldier, of how to fight, and those conventions shaped and troubled not just the conscience of Robinson years later, but many I.R.A. men at the time. While the Monaghan I.R.A. have acquired a reputation for some of the period's more contested killings, reticence was still there to be found. When a railway ticket checker was to be shot ‘the Scotshouse Co. were deputed to do the job, but only one of them turned up’; while the sight of a ‘pregnant wife’ on another night was enough to send some of them home.Footnote 83 It might be put down to poor training, a lack of discipline or whatever else, but there were things some men simply could not do, and when they could not do them was sometimes down to unpredictable circumstance. The night Thomas Byrne was shot in Drumlish his brother was meant to be killed as well, but looking at him lying in his bed, seeing what the Great War had done to him, the man who stood over him could not shoot. He left him be because ‘I have been through the mill myself’.Footnote 84 People did not die for all sorts of reasons in Ireland: the threatening letters often worked, many left and were not killed, or if they were, their solitary example in a small place was as instructive as a massacre.Footnote 85 But many other reasons for reticence remain well beyond our ken.

V

If, as Charles Townshend argues, ‘Ireland's violence was constrained by social mechanisms we do not yet fully understand’, it may take many different approaches to fathom them.Footnote 86 The history of emotions might tackle a history of guilt or the weight of conscience; it might take on the restraint exercised by all sorts of influences, whether familial or religious, whether the fear of fighting or the fear of getting caught. But constraint might require something even more imaginative than that: a history of what didn't happen and why. There might be obvious questions to ask: why were so few politicians, so few landlords killed? Why were there not more burnings of Cork or sackings of Balbriggan, more Loughnan brothers tortured and destroyed? Why were so few women killed? Why were there not more murders like the McMahons in Belfast? Why were more chapels, churches and meeting houses not vandalised and torched, more priests killed, more Dean Finlays left dead? How were the impetuses to rid, to eliminate kept in check? But, after the obvious, there are the things that tend to leave far fewer records behind: the ‘mundane amicable interactions’, the ‘everyday accommodations’ that were not sought out by the Bureau of Military History or Ernie O'Malley or the Imperial War Museum, the things that temper the instincts, that rub along with the insults and the warnings and the knocks on the door in the night, the things that maybe, when it came to it, kept quite a lot of people alive.Footnote 87 Sometimes in a history of violence ‘it is the restraint, rather than the disorder, which is remarkable’.Footnote 88 It might be time to give the history of restraint a try.