Background

Xenophon's Anabasis describes how in 401 b.c. Cyrus, younger brother of the Persian king Artaxerxes II, hoping to seize the throne, gathered an army in Ionia. It included Anatolian troops under the Persian Ariaios, and about 13,000 mercenaries, mostly heavy-armed Greeks under several generals. The army marched through Anatolia and down the Euphrates, heading for the great city of Babylon, but Cyrus was killed in the Battle of Cunaxa. The mercenary force was still intact, and proceeded through Babylonia and Assyria, first under truce, later under attack. Nearly 10,000 eventually reached Greek territory at Trebizond on the Black Sea. There is further information about some of these events from other historians, notably Diodorus (14.19–31) and Plutarch (Life of Artaxerxes); their independent sources included Ctesias, who had been a physician at the Persian court, and probably another of the surviving mercenaries.

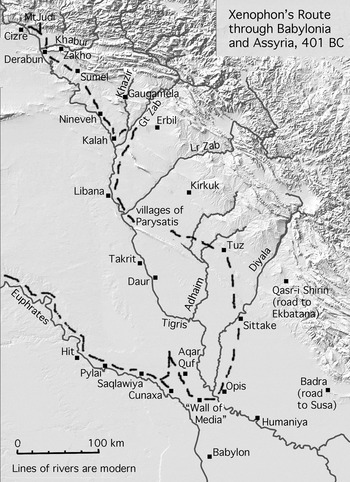

The Anabasis has been repeatedly studied from many angles. For this paper I have myself relied on the accessible Perseus and Loeb editions of the text. Further references can be found, for instance, through Tuplin (Reference Tuplin and Briant1999; 2003), Lane Fox (Reference Lane Fox2004), and Hobden and Tuplin (Reference Hobden and Tuplin2012). Modern editions still carry divergent maps of Xenophon's route, and my purpose here is to clarify the geographical issues in Babylonia and Assyria (Figs. 1–2). I have for convenience used the traditional date of 3rd September 401 b.c. for the Battle of Cunaxa, although the precise chronology is unsure (Tuplin Reference Tuplin and Briant1999: 356–57) and some scholars now advocate a date in the second half of November (Paradeisopoulos Reference Paradeisopoulos2014: 220–21, with further references). Certainly this part of the march happened in autumn or early winter, when the rivers were low, after the melt of the preceding winter's snow and before the worst rain and snow of 401–400 b.c., which the Greeks did encounter in Kurdistan and Armenia. Xenophon's account of the march includes a few names of rivers and towns, but he had limited opportunities to ascertain them (he does not even name Cunaxa), and some of those he does give are problematic. Otherwise determination of the route depends mainly on his descriptions of the countryside and his rate of progress, which he reckons by day-stages and parasangs, neither of which is amenable to absolute measurement.

Fig. 1 General map of Mesopotamia (Moberly Reference Moberly1927: pocket at end).

Fig. 2 Proposed route of Xenophon through Babylonia and Assyria. Topographical base-map courtesy of Jason Ur, with additions by J. E. Reade

The significance of Xenophon's parasangs has been the subject of an entire paper (Rood Reference Rood2010). As for their actual length, Lendle (Reference Lendle1986: 194), in a thorough study of part of the route, opted for 4 kilometres, but this is too low for general use. According to Layard (Reference Layard1853: 59–60):

… the parasang, like its representative the modern farsang or farsakh of Persia, was not a measure of distance very accurately determined, but rather indicated a certain amount of time employed in traversing a given space. Travellers are well aware that the Persian farsakh varies considerably according to the nature of the country, and the usual modes of conveyance adopted by its inhabitants. In the plains of Khorassan and central Persia, where mules and horses are chiefly used by caravans, it is equal to about four miles [6.4 kilometres], whilst in the mountainous regions of Western Persia, where the roads are difficult and precipitous, and in Mesopotamia and Arabia, where camels are the common beasts of burden, it scarcely amounts to three [4.8 kilometres]. The farsakh and the hour are almost invariably used as expressing the same distance. That Xenophon reckoned by the common mode of computation of the country is evident by his employing, almost always, the Persian “parasang” instead of the Greek stadium; and that the parasang was the same as the modern hour, we find by the distance between Larissa (Nimroud) and Mespila (Kouyunjik) being given as six parasangs [3.4.10], corresponding exactly with the number of hours assigned by the present inhabitants of the country, and by the authorities of the Turkish post, to the same road. The six hours in this instance are equal to about eighteen English miles [28.8 kilometres].

This gives a parasang of 4.8 kilometres, although the distance is more like 34 kilometres by air according to Google Earth, and more by land, at least 36 kilometres, giving a parasang of 6 kilometres or more on that occasion.

Additional well-informed estimates were collected by Lobdell (Reference Lobdell1857: 240–41).

Dr Perkins of Oroomiah [Urmia] reckons the fursakh (which all allow to be the parasang of the ancients) as equal to “four and a half or two-thirds miles” [7.2–7.5 kilometres]. Col. Rawlinson says: “the fursakh is a very uncertain measurement, but in Susiana may be valued at three and three-quarter miles [6 kilometres].” My own opinion is, that it varies with the mode of travel; though the mule is the standard, and is equal to three miles an hour [4.8 kilometres]. Post-horses in Persia go about four and a half miles an hour [7.2 kilometres]; in Turkey, not over four [6.4 kilometres]. A camel when urged will walk six miles an hour [9.7 kilometres], but the ordinary pace of a caravan of camels is not over three miles [4.8 kilometres]. An hour, in Turkey, is reckoned at three miles [4.8 kilometres], which, as I have said, should be reckoned the value of the parasang in Persia also—allowance being made for distance by the pace of the animal ridden. The Commissioners of the English and Russian governments, lately engaged in running the line between Turkey and Persia, also regard the fursakh, I have been told by the geologist attached to the Commission, as equal to three miles [4.8 kilometres].

What is clear is that the speed at which the Greeks moved was variable. It was affected by the nature of the terrain, natural obstacles and enemy attacks, whether or not the force was prepared for battle or was carrying many wounded soldiers, and whether there were other reasons to hurry or loiter. Also it is well known that, the smaller a force, the faster it can travel. In Babylonia the Greeks were accompanied by a Persian-Anatolian force, and had baggage with them. In contrast, on the Larissa-Mespila stage specified by Layard, they were alone, they had burned their baggage, and they were marching at full speed in order to escape their pursuers, but they had to maintain a defensive formation. Factors like this impose additional degrees of vagueness.

Xenophon's reliability is a different issue. Some scholars have agreed with Barnett (Reference Barnett1963: 1), that his account “must have been based on a regularly kept log or diary”. A commander of mercenaries needed to keep at least a tally of days, to ensure that his men were paid for their time (Tuplin Reference Tuplin and Briant1999: 342–47), and Xenophon could originally have been assigned this duty and have kept writing materials to hand, but Cawkwell (Reference Cawkwell2004: 51–59) questioned how practicable it would have been for him, in the circumstances of the long march, to maintain a written record at all. As a boy of good family in fifth-century Attica, Xenophon must have been trained to exercise his memory, and on the march he could at least have tried to memorise the elementary framework of distances, notable place-names, and associated episodes. The expedition ended in mid-399 b.c. He could have written an immediate aide-memoire, but is thought to have written the full final version of the Anabasis many years later, by which time he could have checked some details of his route by reference to other sources. His more elaborate passages plainly amalgamate memory and imagination.

Reliance on memory would explain many problems in the Anabasis. For comparison, I myself walked some 800 kilometres over thirty days in 2003 through an unfamiliar part of Spain; I kept a diary of a few words each day, and afterwards wrote an 18,500-word account of everything that seemed memorable. I then found, on comparing the diary with the longer account, that I had remembered two or three episodes in the wrong chronological order; there might be more mistakes if I tried to write it again now, in 2014. It would not be surprising if Xenophon, in describing what had happened during almost two years in his past, in dangerous and sometimes repetitive conditions, occasionally made mistakes. There are besides the technical possibilities of textual corruption and interpolation.

Some of Xenophon's information must be second- or third-hand, since he cannot have checked it. This famously affects his two references to the “so-called Wall of Media” or Median Wall: a trench which the army passed near the Euphrates is said to have reached 12 parasangs as far as the Wall (1.7.15), and the Wall is said to have been 20 parasangs long (2.4.12). He states that two canals which he crossed were derived from the Tigris (2.4.13); this is possible but arguable. Similarly the Greek general Clearchus is quoted as saying, the day after the battle of Cunaxa, that he now understood that the Persian king was on the far side of the Tigris (2.2.3); even if this had been so, which is improbable, Clearchus could not have known it for certain. Statements like these do not directly elucidate Xenophon's route.

An independent set of problems has been created by subsequent physical changes in the regions through which Xenophon travelled, especially in Babylonia. Even if we discount recent development and duplicated or incorrect place-names on modern maps, it is difficult to overstate the degree of confusion presented by this landscape, inhabited and cultivated since time immemorial, where gravel plains, and alluvial and aeolian deposits that can be many metres deep or severely abraded, are intersected by rivers that have repeatedly changed course and by irrigation canals in need of continual maintenance and replacement. On the other hand, we are blessed nowadays with resources like Google Earth, which few scholars who studied this theme in the past could ever have envisaged.

From the Gates to Cunaxa

The army of Cyrus, following the left bank of the Euphrates, entered Babylonia between modern Hit and Ramadi through Pylai, the “Gates”, on or about 27th August (1.5.5). The area was visited by Musil (Reference Musil1927: 222): “… the army marched to … where the Tertiary formation ends and the alluvial plain of Babylonia begins at a point marked on the right bank of the Euphrates by the rocky spur of al-'Okoba and on the left bank by the rocks of al-Aswad. We may therefore look for the Pylae of Xenophon at the pass at the eastern foot of the latter crag.” This is the strategic location of an Early Dynastic site, Tell Aswad (33° 31′ 14″ N, 43° 2′ 29″ E), which has produced several fine statues, presumably from a temple deposit (Wootton Reference Wootton1965; Munir Reference Munir1973). Field (Reference Field1940: 17) describes the same locality: “As far south as the Tell Aswad reach, the river bed is rocky, with numerous ledges and rapids, but beyond this point the bed of the river and both banks consist of alluvial soil.” Lendle (Reference Lendle1986: 196) collected slightly different suggestions for the location of the Gates, which have to be somewhere near here. Other names currently visible on Google Earth are Albu Nimr near Tell Aswad, and, on the right bank of this stretch of the river, Khan Abu Rayat.

After passing the Gates, the army continued down the left bank, finding that everything of possible use on their route had been destroyed by the king's cavalry (1.6.1). They advanced 3 stages, each of 4 parasangs (1.7.10), one stage of 3 parasangs during which they were in battle order and crossed a freshly dug trench (1.7.14–16), one stage of unspecified length (4 parasangs?), and a final stage of 4 parasangs (1.10.2) to a point near Cunaxa where they met the Persian army. It was Bewsher (Reference Bewsher1868: 166–70) who established the topography of this part of the route, building on previous work. He identified the trench as a canal-head near modern Saqlawiya, at the head of the Khur depression (which may be Kheir on some maps because, as Lamia Al-Gailani Werr tells me, Saddam desired to give it a more auspicious name). Xenophon describes the trench as having been dug as a defense; it is indeed possible that the king had intended to utilise an existing version of the Saqlawiya canal in this way, clearing it in order to flood it and trap Cyrus’ army without fresh supplies on the western side, but if so the work was not finished in time. So the next halt was near Fallujah, and Bewsher also discovered the fact, “almost too good to be true” but inescapable, that a mound named “Kuneeseh, or Kunaseh”, or Quneisa, was in the area already suggested on other grounds as the site of Cunaxa. The route is described in detail by Musil (Reference Musil1927: 223–24); Lendle (Reference Lendle1986: 196–98) mentions minor alternatives.

Barnett (Reference Barnett1963: 14–17) offered a different scheme, arguing that the major branch of the Euphrates, along which Xenophon was marching, then followed a course east rather than west of Falluja and Quneisa, probably corresponding to the line of the Saqlawiya canal through the Khur depression; this has been an old course of the river (Black et al. Reference Black, Hermann Gasche, Gautier, Killick, Nijs and Stoops1987: 40, fig. 16). Xenophon did not cross the Euphrates. According to this scheme, therefore, he cannot have passed through Falluja, he cannot have reached Quneisa, and Cunaxa must have been located much further east: Barnett proposed to put it at a site called Al Nasiffiyat. Much work remains to be done on the evolution of all the courses and names of the rivers and canals in this region; for instance Barnett proposed that the Saqlawiya canal at one stage acquired the name of the celebrated Nahr Malkha, which is better known further south. The Al Nasiffiyat proposal, however, was firmly dismissed by Lendle (Reference Lendle1986: 219–20), and the latest study of the topography by Gasche (Reference Gasche2010: Tav. IV) keeps Cunaxa where it was.

“Walls of Media”

Xenophon (1.7.15) states that the trench the army crossed, which must have been near Saqlawiya, extended across the plain for 12 parasangs to the “Wall of Media”. His unusual usage of the term “Media” to include the Assyrian heartland, in several contexts, has been analysed by Tuplin (Reference Tuplin, Lanfranchi, Roaf and Rollinger2003), and need not detain us here. This passage is one of two references by Xenophon to the “Wall of Media”, which has also been identified or associated with other ancient structures mentioned in several Classical and Akkadian documents (Black et al. Reference Black, Hermann Gasche, Gautier, Killick, Nijs and Stoops1987: 15–28). As there are at least seven structures involved, it may be helpful to list them all together (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Features sometimes associated with the “Wall of Media”. 1: Al-Mutabbaq. 2: Sidd Nimrud. 3: Umm Rus Wall. 4: Saqlawiya canal-head. 5: Serakha structure. 6: Baghdad, Karkh structure. 7: Habl al-Sakhr, identified as part of Nebuchadnezzar's “Wall of Media”. Detail of Fig. 1, with additions by J. E. Reade

1. Al-Mutabbaq (equally known as Sidd Nimrud, “Nimrod's dam”, or as Chali, but the latter name applies to so many dykes or ramparts that it is better not used for any specific example). The wall is made of mudbrick and gravel, with rounded turrets facing north-west (Figs. 4–6). It emerges from a knot of canal-banks above the right bank of the Tigris, south of Samarra, and runs in an almost straight line about 9 kilometres south-westward. It was briefly excavated and identified as Late Abbasid by Herzfeld (Reference Herzfeld1948: 81–84), and briefly studied by Tariq al-Nu'aimi and myself in 1964; I thought it might be Sasanian (Reade Reference Reade1964: 86–87). A rectangular mound (c. 200 by 130 metres), with an Imam al-Khidhr shrine and graveyard on top, is situated just east of the Tigris end of the wall but is not aligned with it (34° 2′ 15.5″ N, 44° 1′ 4.8″ E). Surface pottery (Fig. 7) found by the graves was mainly Islamic, including Late Abbasid jars with relief decoration (cf. Reitlinger Reference Reitlinger1951), but there were also characteristic impressed sherds of the Sasanian period (cf. Simpson Reference Simpson, Peruzzetto, Dorna Metzger and Dirvem2013), so the site may have originated as a Sasanian fort or barracks. A modern structure now covers the other low fort, 20–25 metres square, with corner turrets and possibly Parthian pottery, that adjoined the opposite, south-western, end of Al-Mutabbaq (33° 57′ 46″ N, 43° 58′ 21.5″ E).

Fig. 4 Al-Mutabbaq: schematic plan and section. Sketch by J. E. Reade (Reference Reade1964)

Fig. 5 Al-Mutabbaq: view east across Herzfeld's sounding beside Berlin-Baghdad railway, showing rounded turret with mudbrick skin and gravel filling. Photograph © J. E. Reade

Fig. 6 Al-Mutabbaq: view east across rampart, with rounded mudbrick turrets. Photograph © J. E. Reade

Fig. 7 Stamped Sasanian and high-relief Abbasid sherds from Imam al-Khidhr, beside Al-Mutabbaq. Photograph © J.E. Reade

Al-Mutabbaq has special status as the first “Wall of Media” to be discovered, and the most resilient. In 1834,

during the usual evening's palaver, I inquired whether they had ever heard of the Median Wall, or of anything like it - when, to my astonishment, they answered that every Bedwin child knew it - that it leaves the Dijlah between Istabilat and Harbah, runs in a straight well-defined single embankment, with round projections from it, across Jezirah to Felujah on the Euphrates, and is called Khali or Sedd Nimrud; and that ‘it is still so high that two horsemen, one on each side, cannot see each other’ (Ross Reference Ross1841: 130).

Many travellers have mentioned it. Jones (Reference Jones and Hughes Thomas1851: 260–63) calls it the “Chali Batikh” and describes it as “nothing more than a ramp or high dike composed of a hard pebbly soil thrown up on one side (the south only) from the excavated trench at its base,” but this is an uncharacteristic mistake by the great geographer, whose party could not inspect the north-western face of the rampart for fear of being observed and attacked by Anaiza or Shammar raiders. While in 400 b.c. Al-Mutabbaq had not yet been built, it was often included in nineteenth-century reconstructions of Xenophon's route, and it is still liable to influence maps illustrating the Anabasis.

2. Sidd Nimrud (equally Chali, see No. 1) is a canal, dyke, barrier or series of such features running south from the Tigris in the desert west of Samarra (Musil Reference Musil1927: 51, 142, 148; Herzfeld Reference Herzfeld1948: 84–6; Reade Reference Reade1964: 88–9). Their existence accounts for the belief that Al-Mutabbaq extended to the Euphrates, but the evidence for their course or courses is confusing. Reade wondered if part of this structure, close to the right bank of the Tigris, was the “Royal Dyke” mentioned by Polybius (5.51.3); an attacker from the north was liable to meet this dyke after a six-day march through deserted country, and it was defensible in 220 b.c. Polybius’ description makes sense, because hills and cliffs just south of Shergat would prevent an army from following the right bank of the river downstream and force it into the desert to the west. So the “Royal Dyke” began somewhere upstream of Samarra, and headed west, south-west or south from the Tigris into the desert. Its name implies that it was famous, and perhaps of considerable age and importance. It can have nothing to do with Xenophon, however, except that it may have been remotely linked in some way with Nos. 4–6, below.

3. Umm Rus Wall (equally Chali, see No. 1) is a partly turreted wall that runs from a 170 metre square fort by the village of Umm Rus, on the left bank of the Euphrates east of Ramadi, northwards into the desert for about 13 kilometres (Musil Reference Musil1927: 151–52; Barnett Reference Barnett1963: 7–8; Reade Reference Reade1964: 87–88). Barnett suggested a relationship with the trench mentioned by Xenophon as extending to the Wall of Media, but the Umm Rus Wall is too close to Pylai. Barnett could be right, however, in proposing that it is mentioned by Ammianus Marcellinus as Macepracta: the name suggests an Arabic feminine plural, perhaps related to a term such as maqbara, graveyard. Tariq and I inspected the Umm Rus Wall, but I am not confident that I see it now on Google Earth. In the same area a 30 × 40 metre rectangular enclosure is visible on Google Earth about 7 kilometres north of the river (33° 31′ 49″ N, 43° 23′ 43.5″ E); we failed to observe this on the ground in 1964.

4. Saqlawiya. Xenophon's statement (1.7.14–16) that the trench passed by the Greeks was linked to the “Wall of Media” may be wrong, but the possibility that the Saqlawiya canal itself or the southern edge of the Khur depression was at some stage utilized for a defensive function cannot be excluded (Reade Reference Reade, Baker, Robson and Zólyomi2010: 283). Since the Saqlawiya flowed through the Khur to the Aqar Quf area, there might also have been defensive structures, waterworks or outworks near Aqar Quf which were associated in antiquity, or were sometimes thought to be associated, like Nos. 5–6, with a “Wall of Media”. Jones (Reference Jones and Hughes Thomas1851: 265) indeed concluded that “the Median Wall was a mere local barrier of defense, running, perhaps, in a north and south direction between the meeting canals drawn from the Euphrates and Tigris.” However, no reference to a defensive wall in this vicinity has been recognised in the extant inscriptions of Nebuchadnezzar, the Babylonian king responsible for what is so far much the most satisfactory “Wall of Media” to be identified, i.e. No. 7 (Black et al. Reference Black, Hermann Gasche, Gautier, Killick, Nijs and Stoops1987: 17).

5. Serakha (Kadhimein). Ross (Reference Ross1839: 443–46) observed, while riding along a mainly dry north-south canal about an hour north of Kadhimein, “a large pool of water in its bed, from which were dug up, only last year, the remains of an ancient bridge, to build a house in Baghdad: the bridge was built of bricks, with cuneiform inscriptions, exactly similar to those of Babylon, and cemented with bitumen.” Jones (Reference Jones and Hughes Thomas1851: 226–27) visited what seems to be the same place. “A ruin of a very massive character, and certainly of great age, is seen on the east bank of the Serakha lake; the old canal that we have ridden along having been apparently led over it, for digging through its bed exposes the structure beneath, which is built of large kiln-burnt bricks imbedded in bitumen, and, indeed, is the only ruin in this country that I have seen which answers in its construction and material to the detailed description given by Xenophon of the Median Wall [see No. 7]. … If aught more is wanting to give it a claim to a high antiquity, we have, buried in the bed of the canal above it, in a straight line with its course, a nicely arranged and continuous tier of sepulchral urns, amounting to thirty-four in number … lined on the inside with a thin coating of bitumen… The bricks seen here are of the size and shape of the Babylonian period, though I could not discern any stamped characters” but “I have, indeed, heard from others that the cuneiform stamp had been seen on the bricks brought from hence. The number of shafts sunk in the soil attest, however, that a vast mine of material exists here and in the immediate vicinity, did not the caravans of asses passing to and fro between Baghdad and Serakha, laden with bricks of a large size show the extent of the city that once occupied the country contiguous to the Tigris and the canal… From the modern Baghdad, on the west side of the Tigris [i.e. No. 6], to Serakha and the ruins under consideration, may have been the extent of the city and its environs.” This, for Jones and indeed Henry Rawlinson (see below, No. 6), was the city (“Sittake”) near which Xenophon crossed the Tigris (2.4.13–24).

The sepulchral urns were “torpedo” jars (Fig. 8), of Parthian or later date, in which case the building underneath was part of at least one substantial earlier official structure. Adams, however, in his survey of the area, described the nearest site as having “limited Neo-Babylonian-Achaemenid” but “mainly Parthian” surface material (Gibson Reference Gibson1972: 191, Map 1B, no. 050). The discrepancy is explained by the depth of the brickwork recorded by Ross and Jones, which further implies a very significant depth for any other pre-Parthian remains in the vicinity, as with the prehistoric remains at Ra's al-Amiya further south (Stronach Reference Stronach1961: 101, fig. 4). The “cuneiform stamp” on the Serakha bricks was presumably but not certainly a Nebuchadnezzar stamp, as at No. 7 (Black et al. Reference Black, Hermann Gasche, Gautier, Killick, Nijs and Stoops1987: 39, figs 12–15).

Fig. 8 Parthian or later sepulchral urn at Serakha (Jones Reference Jones and Hughes Thomas1851: 226).

6. Baghdad (Karkh, including Khidhr Elias). At least one Neo-Babylonian structure with inscribed bricks has been seen at low water on the right bank of the Tigris in the Karkh quarter. It is described by Rawlinson in a letter of 18th March 1846 (British Library, Add Ms 38976: 324–28): “I find we have had under our very noses at Baghdad the most perfect and extensive ruin in all these parts without ever noticing it. You have no doubt remarked the great brick wall which lines the right bank of the river for some hundreds of yards opposite to the Pasha's Serai. This is a bona fide Babylonian work and in better preservation I think than the Birs [Borsippa] or the Kasar [Babylon]… I had always taken it for a work of the Caliphs, but on examination I have found full half the bricks to have the Babylonian stamp and there are other unmistakable marks of its Chaldaean origin… I am staggered, but such is the fact. I expect to get some 30 or 40 varieties of stamp from this mass of bricks. We may now also pretty confidently identify Baghdad with Sitace.” This must be, at least in part, the same structure as that described by Jones (Reference Jones1847: 302) as having emerged when the Tigris was exceptionally low. “The great extent of the ruins, the size of the bricks, the great depth at which they are found (24 feet [7.3 metres] below the surface of the soil) justify, in my opinion, Major Rawlinson's conclusions, and above all the cuneiform characters on each alternate layer of bricks point out clearly the pains taken in the construction of the buildings, rendering the supposition that they had been brought originally from Babylon highly improbable.” The significance of Baghdad as a Neo-Babylonian and probably therefore Achaemenid site may also be supported by the discovery there of a second-millennium Egyptian granite lion (now British Museum, EA 987). It was found “yesterday in removing the foundations of a house, only a few hundred yards from my door,” i.e. the door of the British Residency, at c. 33° 19′ 38″ N, 44° 24′ 29″ E (Rawlinson, 5 November 1852, British Museum Middle East Dept. Correspondence). Rawlinson reasonably conjectured that the lion “may have been brought back as a trophy by Cambyses, or any of the Achaemenian kings”. Part of the Karkh structure near the Khidhr Elias shrine, at c. 33° 20′ 29.5″ N, 44° 22′ 48″ E, has been excavated (Behnam Reference Behnam1976); the remains are substantial but difficult to understand. Although Black et al. (1987: 15) did not favour a connection between this structure and the outermost defenses of Babylon as represented by Nebuchadnezzar's “Wall of Media”, No. 7, the two were roughly contemporary, and both should be considered in any discussion of Neo-Babylonian defenses that incorporated water from the Tigris.

7. Habl al-Sakhr. This stretch of ancient wall, which is located about 20 kilometres south of Baghdad, was identified first by Bewsher (Reference Bewsher1868: 169) as the “so-called Wall of Media” through which the Greeks passed some weeks after the Battle of Cunaxa (2.4.12); Xenophon described it as 20 feet wide and 100 feet high, made of bricks laid in bitumen, with a reputed length of 20 parasangs. Parts of the surviving foundations of Habl al-Sakhr have been properly excavated and published (Black et al. Reference Black, Hermann Gasche, Gautier, Killick, Nijs and Stoops1987); the wall incorporates Nebuchadnezzar inscribed bricks, and was about 7 metres wide, with a road running alongside its inner face. It seems to correspond to the defensive wall described in Nebuchadnezzar's inscriptions as reaching, from the Euphrates, to the Tigris above the city of Upie (Akkadian), i.e. Opis (Greek). These inscriptions do not mention the Medes as a threat, merely a “murderous enemy” in general, but Herodotus had known of Babylonian defenses reputedly built against the Medes, which would account for the name “Wall of Media” provided by Xenophon (Black et al. Reference Black, Hermann Gasche, Gautier, Killick, Nijs and Stoops1987: 17, 24–25). The remains of Habl al-Sakhr were traced for 15 kilometres, but the junctions with the two rivers were not found. Black et al. (1987: 40, fig. 16) proposed that the wall continued eastward, from the excavated points, to join an ancient course of the Tigris at c. 33° 12′ N, 44° 36′ E; Gasche (Reference Gasche2010), in the light of further topographic analysis, suggested moving the junction south-eastward to c. 33° 3′ N, 44° 37′ E.

8. The Wall of Semiramis. This was probably a Greek name for the Tigris end of the wall of which Habl al-Sakhr was part (Black et al. Reference Black, Hermann Gasche, Gautier, Killick, Nijs and Stoops1987: 22). A dotted line, labelled “Wall of Semiramis”, is shown running across the desert, roughly between Samarra on the Tigris and Hit on the Euphrates, on the map accompanying the introduction to Lane Fox (Reference Lane Fox2004).

From Cunaxa to the Tigris

During the battle of Cunaxa, on or about 3rd September 401 b.c. (1.8.8–29, 1.9.1–19; Diodorus 14.23–24; Plutarch, Life of Artaxerxes 8–13), Artaxerxes was wounded, and the Greeks easily won their part of the battle, but Tissaphernes rallied the Persian army and Cyrus was killed. Ariaios and his Anatolian troops retreated to their previous night's camp, and were joined the next day by the Greeks. They set off together on 5th September on what was intended to be a rapid march back to Anatolia. They were marching with the sun on their right, i.e. north or east, and must therefore have been crossing the low bare ridge south of the Khur. Their first camp could have been around 20 kilometres to the east of Falluja, but Persian troops had already stripped the villages, and there was nothing to eat.

Meanwhile Artaxerxes, or rather Tissaphernes who appears as principal on the Persian side, faced a serious short-term problem. On 3rd September the Persians had discovered that none of their available troops could resist the Greeks. On 4th September the Greeks refused to surrender although Cyrus was dead, and the Persians must have feared that they would advance further, which was indeed one of the options that the Greeks discussed (2.1.2). On 5th September, the Persians learnt that the Greeks and Anatolians were retreating and so they pursued them, but on 6th September, after finding the Greeks still in good order on parade, they agreed a truce and guided the army to an area of rich agricultural villages with supplies of food (2.3.9; Diodorus 14.26.1).

The route taken on 6th September, after the truce, cannot have been along a main road, as the Greeks had to improvise bridges across several channels full of water, with the help of palm-tree trunks. Joannès (Reference Joannès and Briant1995: 190) has suggested that the area eventually reached was well to the south-east of Aqar Quf (“entre les environs de Sippar et l'actuel site de Baghdad”), but this would have been towards Babylon, not the direction in which to have guided dangerous enemy troops. Sippar was also close to Habl al-Sakhr, the presumed Wall of Media, which the army later took three days to reach (2.4.12). Jones (Reference Jones and Hughes Thomas1851: 265) located the “provision villages” north of Aqar Quf, where the Khur widens and there has sometimes been a marsh, in “the triangular tract of alluvium now embraced by the angle formed between the Tigris, the Saqlawiyeh, and the line of demarcation between the desert and cultivated soil.” Others have looked in much the same direction (e.g. Lendle Reference Lendle1986: 203, with further references). There is no adequate published evidence for the nature of ancient sites in this region before the Parthian period, although Aqar Quf had itself been the great Kassite city of Dur Kurigalzu. Some of the types of administrative text mentioned by Joannès (Reference Joannès and Briant1995: 193) probably allude to this area, which could have received water from the Euphrates (mostly through the Khur depression, via the Saqlawiya canal or related water-courses) and from the Tigris (early versions of the Dujeil). Many remains are deeply buried under alluvium (see above, “Walls of Media”, Nos. 5–6). As there were over 12,500 Greek soldiers and a large number of Anatolians, in addition to camp-followers, and as the army eventually stayed in this area for over three weeks, substantial supplies must have been available.

In parking the Greeks and Anatolians here, Tissaphernes knew that a fresh undefeated Persian army under Abrokomas was on its way from Phoenicia. This was coming (there is no alternative route in the circumstances) via the Great Royal Road, the long-established highway linking the east and west of western Asia, from Susa to Sardis. It was the principal artery of the Persian empire (Herodotus 5.52–53), although the precise route taken and the crossing-points of rivers may have been variable, affected by weather, water-levels and the provision of pontoons, and may have evolved over time. The Royal Road reappears periodically in our discussion below, because soon afterwards Xenophon was following the same road near the Tigris in the opposite direction.

Abrokomas, coming from Phoenicia, will have reached the Tigris at a river-crossing above Mosul. Presumably, because Xenophon reached the same point, this crossing was at Cizre (Jazirat ibn Omar). It is not known whether in this period the principal branch of the Royal Road then passed north of Jebel Maglub (where the Battle of Gaugamela was later fought) and so across the Greater Zab river to Erbil, or passed south of Jebel Maglub and across the river either to Erbil or to Shemamok nearby. In either case Abrokomas will have continued south-south-east alongside the Zagros foothills across the Lesser Zab to modern Kirkuk. He will have turned right somewhere near Miqdadiya on to the Ecbatana (Hamadan)-Babylon highway, the ancient equivalent of the Great Khorasan Road, and crossed the Tigris back from east to west near its confluence with the Diyala. He arrived about 7th–8th September, five days after the Battle of Cunaxa (1.7.12), which diminished the immediate threat. It was also handy for Tissaphernes’ plans that two additional Persian armies, commanded by Artaxerxes’ half-brother, were approaching from Ecbatana and Susa. Xenophon was to meet them near the Diyala, a month after the Battle of Cunaxa, when they too seemed to be marching towards Babylonia (2.4.25).

Persian and Greek plans and intentions over the next few weeks are arguable (e.g. Bassett Reference Bassett2002), but the simplest explanation for Tissaphernes’ actions is that suspected by the Greeks themselves (2.4.2–4) and specified by Diodorus (14.26.5), that he aimed to destroy or disperse them. For such a force to penetrate easily within striking distance of Babylon, and escape unscathed, would set a dangerous precedent. The Greeks valued themselves as soldiers, and many hoped to be re-employed by the Persians, but they were by no means the first mercenaries to appear in the Middle East, and Tissaphernes must have been aware that, as so many people have learnt to their cost throughout history, hired armies are unreliable and dangerous. Cyrus had experienced this in the immediate past (1.3.1, 1.4.4, 1.4.7, 1.4.13, 1.5.11–17, 1.8.12–13): some of his men were reluctant to advance beyond Anatolia; some were deserters from Abrokomas; some deserted or thought of deserting Cyrus; some demanded extra money to march on Babylon; some nearly began a battle among themselves on the march; and, at the Battle of Cunaxa itself, their leading general Clearchus refused to follow orders from Cyrus. It is even possible that, if Clearchus had taken the risk of attacking the Persian centre as instructed, the manoeuvre that Alexander the Great was to employ at Gaugamela, Cyrus would have won the battle.

Tissaphernes did not know all these details, but he knew that the Greeks had declined to surrender. They could yet have been useful to the Persians, in some faraway place like the Indian or Central Asian frontier, where centuries later the Parthians would send some of their prisoners from Carrhae, but they could not be trusted as a free-minded unit still under Greek command. In the event this same army, after escaping to the Black Sea, was to be employed by the Spartans to fight against Tissaphernes all over again, so, if he did wish to destroy them as soon as possible, he was right. Meanwhile, however, he agreed to escort them peacefully back to Ionia, but procrastinated for weeks. In the interval he set about what may have been the relatively straightforward task of persuading Ariaios and his supporters to accept a royal pardon and secretly prepare to change sides. He was probably also negotiating with one of the Greek generals, Menon, who was a Thessalian and a close friend of Ariaios; Xenophon distrusted and detested him (2.6.21–29). Otherwise the Greeks were suspicious but trapped, without reliable friends or even a map (2.4.2–7; Diodorus 14.26.5, 14.27.2).

Eventually the journey started, perhaps about 1st October. Tissaphernes with his own cavalry, an Armenian party and Ariaios’ men led the way, and each night the Greeks, who had their own guides, camped at a safe distance of a parasang or more away; the Persians arranged markets for the purchase of food by the Greeks. The other forces were perhaps supplied from royal storehouses on the route. An important factor emphasised by Barnett (Reference Barnett1963: 25) and Lendle (Reference Lendle1986: 203–04) is that the Persians were choosing where to go. One wonders how this worked. Presumably Tissaphernes sent messengers ahead, in order to prepare markets, and instructed the guides where to lead the Greeks each day, though they will also have seen the dust raised by the others a mile or two ahead. The Greeks must have noticed that they were initially going south, in what seemed to be the wrong direction, which Tissaphernes could have justified by reference to roads and river crossings, but it cannot have promoted confidence. He must have been anxious to get the Greeks away from vulnerable centres of population as soon as possible.

After 3 stages (2.4.12), the army reached the “so-called Wall of Media” (see above, No. 7, Habl al-Sakhr). Since the course of Habl al-Sakhr is crooked, and since we do not know exactly where the army began its march towards it, what obstacles it met on the way, and where it crossed the wall, the distance of 3 stages is reasonable but uninformative. A logical position for a gate through which the army could have passed would have been near the point where the wall changes direction, about 5 kilometres north of Sippar. The road identified by the excavations alongside the inner face of the wall could then have been part of the ancient equivalent of the Great Khorasan Road, by which Abrokomas had arrived a few weeks earlier. This will have linked Babylon with a crossing of the Tigris, and have then led via Qasr-i Shirin to the Zagros Gates and Ecbatana. Xenophon remarks that his “so-called Wall of Media” was “not far” from Babylon, a city which could well have been mentioned at this time, as it would have been natural to enquire where the road went; the distance from here to Babylon would actually have been about 65 kilometres, some three days’ journey. The army, however, having passed through the wall, must have turned left in the other direction, and the road could then, although Xenophon does not mention this detail, have continued close to the wall. During the next 2 stages, each of 4 parasangs, i.e. some 40 kilometres in all, the army crossed one fixed bridge and a 7-pontoon bridge across two canals said to derive from the Tigris. It then camped in a fine park near a city, given the name of Sittake, which is described as large and heavily populated and as lying 15 stadia (say 2 or 3 kilometres) from the Tigris itself, across which there was a 37-pontoon bridge (2.4.13–14). The information about the series of three bridges supports the supposition that the army was following a regular highway.

From the Tigris to the Diyala

Xenophon (2.4.25–6) records that next, after crossing the Tigris at Sittake, the Greeks marched a further 4 stages, each of 5 parasangs, to the Physkos river, which was one plethron wide (c. 30 metres), with a bridge which they presumably crossed. The name Physkos, rather than being the name of a river, may merely be derived from an Aramaic word for “crossing” (Barnett Reference Barnett1963: 25; Lendle Reference Lendle1986: 205). Nearby was a city, described as large and given the name of Opis. Here the Greeks met and passed a large Persian army, led by the king's half-brother, that had come from Ecbatana and Susa as if to support the king. It cannot have been reassuring for the Greeks to meet this new Persian force. Clearchus ingeniously arranged that his men should march in a special formation, perhaps while crossing the bridge, so as to appear more numerous and intimidating.

As observed by Black et al. (1987: 23), “those authors who make unequivocal statements about [Sittake's] location do not agree with each other, so that some of them, at least, must be wrong,” but it was certainly on the eastern side of Babylonia, on one of the ways to Susa. Opis (Upie) is the city above which Nebuchadnezzar's original defensive wall reached the Tigris. It is where an earlier Cyrus had defeated the Babylonian army in 539 b.c., and was presumably on or near a highway between Babylon and Iran. Often in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when Al-Mutabbaq was regarded as the Wall of Media, and more recently even (Manfredi Reference Manfredi1986: 152), Opis was liable to be located near the Tigris-Adhaim confluence (e.g. Ross Reference Ross1841). While it has still not been located with certainty (Lendle Reference Lendle1986: 221–22), a position at or close to the Tulul Mujeili’ or Mujeili'at group of mounds, not far from the present Tigris-Diyala confluence, has been widely accepted (Black et al. Reference Black, Hermann Gasche, Gautier, Killick, Nijs and Stoops1987: 18); Gasche (Reference Gasche2010) now prefers a location slightly further south, downstream of Seleucia. Identification of its location is hampered by intractable issues concerning the course or courses of the Tigris and Diyala in the first millennium BC, the location of the eastern end of the “Wall of Media”, and whether Opis was then on the left bank of the Tigris, or on the right bank, or in between two concurrent courses.

There are two principal ways of reconstructing this section of Xenophon's itinerary. If his account is accepted at face value, the Greeks, after passing the Wall of Media, marched south-east. Herzfeld (Reference Herzfeld and Walser1968: 10) accordingly proposed to locate Sittake on the Tigris at modern Aziziya, about 65 kilometres below the present Tigris-Diyala confluence. Barnett (Reference Barnett1963: 23–24, fig. 4) preferred the adjoining site of Humaniya, which is attested as “a place of some consequence” in the ninth century a.d. (Le Strange Reference Le Strange1905: 37). Barnett's prediction that Humaniya could also be Achaemenid was correct. When Tariq el-Nu'aimi and I made our brief survey of some sites related to the Wall of Media (Reade Reference Reade1964), we visited Humaniya, and saw at least two substantial mounds. Surface sherds (Fig. 9) included impressed wares of types regarded as typically Achaemenid by Adams (Reference Adams1965: 130, fig. 13.10A–B), which seems to be supported by the stratigraphy at Abu Qubur (Gasche et al. Reference Gasche, David Warburton, Amandry, Willem Van Zeist and Achilles Gautier1989), though they might have been Hellenistic too (cf. Oates and Oates Reference Oates and Oates1958: 128–29, pl. XXII). One belongs to a bowl of a very fine greenish egg-shell ware with an impressed pattern around the carination; two comparable sherds which we collected at the same time at Humaniya are in the British Museum and visible on its website (1996,1211.190–91).

Fig. 9a-b Exterior and interior of impressed Achaemenid or Hellenistic sherds from Humaniya. Photographs © J. E. Reade

According to this reconstruction, the Greeks, after crossing the Tigris at Sittake, marched back north-westward to Opis. This march and counter-march are difficult to reconcile with the recorded distances (two stages from the Wall of Media to the Tigris, four stages east of the Tigris), but the anomalies might have been imposed by water-courses or by Tissaphernes deliberately choosing time-consuming detours. If this kind of reconstruction of the itinerary is correct, there must have been a significant subsequent error or lacuna in Xenophon's text, as there are then far too few stages, or parasangs, to carry the Greeks satisfactorily clear of Babylonia on to their next adventures in Assyria. This reconstruction requires the existence, at least in dry seasons of the year, of a good highway with bridges which connected the region of Sippar or the Median Wall with the region of Aziziya; it also requires a decent highway upstream of Humaniya along the left bank of the Tigris. It is unclear what purpose such roads could normally have served.

An alternative scheme swaps Xenophon's references to Sittake and Opis: he has simply transposed the names, none of the other circumstantial details. The change was proposed by Musil (Reference Musil1927: 263–66); it was discussed in great detail and adopted by Lendle (Reference Lendle1986: 204–19); it would not have been Xenophon's only mistake of this nature. Basically, by this scheme, the army crossed the Wall of Media and marched 2 stages, each of 4 parasangs, along the main highway on the inside of the wall as far as Opis (whether Tulul Mujeili’, Seleucia or somewhere else nearby). The army crossed the Tigris and proceeded along the same highway for another 4 stages, each of 5 parasangs, to Sittake, which by this scheme was located in the neighbourhood of Sasanian Daskara, or modern Miqdadiya (Shahreban); Lendle (Reference Lendle1986: 210) proposed the site of Imam Sheikh Jabir, identified as an Achaemenid town by Adams (Reference Adams1965: 59, 137, no. 37). Opis and Sittake were then around 90–110 kilometres apart as the crow flies, so a parasang during this section of the march measured around 5 kilometres. It is a reasonable speed for a substantial army, or rather two separate armies, marching on a good road through flat cultivated country with ample water, accompanied by carts carrying baggage and so forth. It was at Sittake that the army came to the “Physkos” river, really the Diyala. The hypothesis that the names of Sittake and Opis should be transposed offers what seems to be so far the simplest interpretation of Xenophon's route.

Tuplin (Reference Tuplin, Sancisi-Weerdenburg and Willem Drijvers1991: 51–54) doubts whether this kind of location for Sittake is compatible with Arrian's statement, if correct, that Alexander the Great marched from Babylon to Susa via Sittake (say 550 kilometres) in only twenty days, with a pause on the way, but Alexander was famous for his speed and such a march is not impossible. It is a roundabout route according to the map, but is the only one which must always have had good roads and long-established way-stations. It also seems to have been the route used by the contingent of the Persian army coming in the other direction, from Susa towards Babylon, that Xenophon encountered near the Diyala (2.4.25). Any routes linking Babylon and Susa more directly, as the crow flies, would probably have had to cross or avoid extensive water-courses and marshes.

From the Diyala to the Villages of Parysatis

Beginning on or about 9th October, the Greeks next marched from the town on the Diyala to the villages of Parysatis, then to a point beside the Tigris river, and then to a point on the Greater Zab river near which it could be crossed, probably above its confluence with the Khazir (2.4.27–28). The time or distance given by Xenophon for this journey is 6 stages or 30 parasangs to the villages of Parysatis, and a further 4 stages or 20 parasangs to the Zab. If the Greeks were still proceeding at about 5 kilometres per parasang, this is a total of 250 kilometres. The distance in a straight line from Miqdadiya to the Zab-Khazir confluence, via a point on the Tigris, is about 300 kilometres. This leaves a gap of two days’ march in Xenophon's record, some 50 kilometres, but since the Greeks obviously did not march in straight lines, the gap is likely to be longer, three days or four.

The march began through deserted countryside. The adjective ἐρῆμος is often rendered as “desert”, which in modern English implies permanent desertion, but that cannot be what Xenophon meant. In March much of this land is green, with grass providing ample pasture for sheep and goats, and with cultivation where possible, but Xenophon saw it in late autumn or early winter, mostly parched. There was a sharp contrast with the palm groves and gardens of alluvial Babylonia through which the Greeks had been moving for the previous weeks. After six days on the march they reached villages belonging to Parysatis, the queen-mother; Cyrus had been her favourite son, and Tissaphernes was her enemy. He allowed them to plunder the villages, which contained an abundance of grain, animals and other goods.

An issue with this section of the march is that, at some moment, the Greeks left the main road. Near Miqdadiya they must have met the Great Royal Road. From Miqdadiya and the Diyala, the westward branch of this road went north and north-west, through modern Kirkuk. It was the route by which Abrokomas had arrived, and which the Greeks had to follow on their way back home. However, they were temporarily diverted to a point much lower down the Tigris. We are not told where the detour began.

Lendle (Reference Lendle1995: 120–23) proposed that they crossed directly from the Miqdadiya region to Daur, on the Tigris between Tekrit and Samarra. This then would be where the villages of Parysatis were located, an identification also supported by Barnett (Reference Barnett1963: 25–26) although the latter had not accepted the Opis/Sittake transposition. If this were correct, then a city which the Greeks passed later and which Xenophon names as Kainai (2.4.28), could be identified with Tekrit. This town was already known as Takritain in the seventh century b.c., which is its name in the Babylonian Chronicle, but that is not decisive. More importantly, the identification of Kainai with Tekrit would leave too short a distance between it and the Greeks’ destination on the Greater Zab; that distance according to Xenophon is a maximum of some 20 parasangs or 100 kilometres, whereas it is in reality 170 kilometres as the crow flies, so more like 200 kilometres in practice. Both Barnett and Lendle recognised that Kainai can only be identified with Tekrit if there was a significant lacuna at this point in Xenophon's record, caused for instance by confusion between the two Zabs. Joannès (Reference Joannès and Briant1995: 197) also looked to the Daur region for the villages of Parysatis, but the cuneiform texts cited by him, while highly relevant to the history of royal estates in the Tigris valley, do not restrict them to the area south of Tekrit; in fact he cites Ashur rather than Tekrit as a possible candidate for identification as Kainai.

Evidence for a lacuna in Xenophon's text has also been found in his failure to mention the Lesser Zab, which the Greeks (whatever their route) must have crossed somewhere near its confluence with the Tigris at Al-Sinn. This is not significant. The best description I have located of the Lesser Zab in this area is in the British Admiralty Handbook of Mesopotamia (Reference Admiralty1917: 77): “In low water, where the numerous shingles or rock ledges obstruct the channel, depths of only 2 ft., 18 in., or even 1 ft. are found; elsewhere the river has 4–6 ft. of water in the low season.” Xenophon's failure to mention an easy ford of this nature is unremarkable. He similarly omits the crossing of the Assyrian Khabur which the army reached a fortnight later. Between Miqdadiya and the Lesser Zab he fails too to mention the low but dramatic Jebel Hamrin range through which (whatever route they took) they must have passed.

There is another objection to the location of the villages of Parysatis at Daur, and indeed anywhere south of the point above Baiji where the Tigris breaks through Jebel Hamrin. The Greeks, to arrive there, had first to be persuaded to leave the Royal Road, which they must have easily recognised as a major highway. They would have been able to see what was ahead of them on this diversion—deserted countryside with steep hills to the right. Such a detour must have seemed suspiciously like a trap, especially if the Anatolian force was still in front of them. Also, long before they had marched for six days, Tissaphernes would have had difficulty providing adequate native markets with food for sale, and well-water would have been limited.

When the Greeks did reach the villages of Parysatis, Tissaphernes authorized plundering them, so some at least of the Persians were still accompanying the Greeks, but by then the mass of Anatolian troops seems to have been somewhere else. Xenophon says nothing about the two forces separating, but, if the villages were indeed in the narrow Tigris flood-plain between Baiji and Daur and if the Anatolians had just passed through in front of the Greeks, it is not credible that the villages of Parysatis were still as well stocked as Xenophon describes them. Similarly, if the Anatolians were now marching behind the Greeks, there would have been no supplies left for them.

An alternative is that the Greeks and Anatolians, instead of going to Daur, continued together from Miqdadiya, crossing Jebel Hamrin on the main highway north. Available crossing-points west of the Diyala itself (on the assumption that this was the Physkus) seem to be the old Kifri road across the Sakaltutan Pass, and the bed of the Adhaim River, probably dry at this time of year. Beyond Jebel Hamrin, in the area centring on Hawija south-west of Kirkuk, between the tributaries of the Adheim and the left bank of the Lesser Zab, there are numerous ancient settlements (Mühl Reference Mühl, Hofmann, Moetz and Müller2012: 80, fig. 1). Additionally, near the confluence of the Tigris and the Lesser Zab, there is ample excavated evidence for prosperous settlements of the third and second millennia b.c. (Mühl and Burhan Reference Mühl, Sulaiman, Miglus and Mühl2011); the medieval town of Al-Sinn, close to the confluence itself (Le Strange Reference Le Strange1905: 90–2), was probably the Neo-Assyrian town of Sinnu. I have not visited the vicinity, and have not met any reference to Achaemenid remains, but it was surely as prosperous then as it has been at other periods.

These are much more substantial areas than the strip of good land on the left bank of the Tigris below Baiji, and provide suitable alternative locations for royal estates such as the villages of Parysatis. After a few days on the road from Miqdadiya, perhaps soon after they had passed Tuz Khurmatlu, Tissaphernes could well have been able to persuade the Greeks to turn aside towards the rich Hawija region in order to plunder and collect supplies, and to proceed in this way to the Tigris. The Anatolians could have taken a parallel track, unless they continued on the main highway through Kirkuk. On this scenario, the Greeks spent three or four days collecting supplies as they worked their way forward through the rich villages. Towards the end of this interlude they crossed the Lesser Zab. Xenophon did not record the length of time they spent here, but this is not a lacuna. The missing parasangs are hidden in the villages of Parysatis.

From the villages of Parysatis to the Greater Zab

Four more stages of altogether 20 parasangs, again through deserted countryside, with the Tigris to the left, brought the Greeks on or about 22nd October to a point near the left bank of the Greater Zab, which they later crossed (2.4.25–2.5.1). Layard (Reference Layard1853: 225) proposed that the Persians at this time were camped near the prominent mound of “Abou Sheetha”. However, a map provided by Oates (Reference Oates1968: 43, fig. 3) places “Abu Sheetha” at c. 36° 7′ 39″ N, 43° 34′ 1″ E, south of the Khazir confluence; an alternative map provided by Layard (Reference Layard1853: map 2 at end), while including “Abou Sheeta”, misplaces the Khazir and is not reliable. The Greeks would have had to march past this mound northwards in order to reach the likely location of the ford or crossing point (discussed below), and the precise location of the Greek and Persian camps near the Zab cannot be determined at present.

During the Greeks’ first stage after the villages of Parysatis, or possibly at the first camp, there was a fine great city called Kainai on the opposite bank, from which the natives brought across bread, cheese and wine. Qal'a Shergat, the ancient city of Ashur, is appropriately situated, some 30 kilometres upstream of the confluence of the Tigris with the Lesser Zab. Little is known of Ashur between its destruction in the late seventh century b.c. and its revival as a Parthian centre, but there must always have been people farming the wide area of irrigable land below the city. There is no problem with Xenophon's description of the city as prosperous, since the Greeks may not have been close enough to judge its condition. A photograph taken in summer from the opposite bank (Fig. 10) still shows the ziggurrat as an impressive feature, and the place must have looked far more impressive 2400 years ago. The identity of Ashur and this city has had many advocates in the past (e.g. Layard Reference Layard1853: 226), and is surely now settled.

Fig. 10 View south-west across Tigris towards Ashur, with ziggurrat left of centre. Photograph © J. E. Reade

There remains, however, a problem with the place-name. The spoken name of Ashur appears in many Neo-Assyrian documents as Libbi Ali, which obviously evolved into the name of Libana by which, as Herzfeld (Reference Herzfeld1907: 231) may have been the first to observe, it was known in the Hellenistic period. So it should have been something like Libali or Libana when Xenophon passed, but he calls it Kainai. There is a comparable problem with the next city which the Greeks passed, beyond the Greater Zab. This is manifestly the site now known as Nimrud, which had been Neo-Assyrian Kalah. Yet Xenophon gives the name as Larisa. These anomalies have been discussed repeatedly, and Tuplin (Reference Tuplin, Lanfranchi, Roaf and Rollinger2003: 370–79) provides a comprehensive study of the status of the two cities in Xenophon's text, complete with proposed explanations and emendations of their names, none regarded as satisfactory.

Maybe the two names were transposed, like Opis and Sittake: Kainai was derived from Kalah, and Larisa from Libali/Libana, and the transposition has been concealed by Xenophon's tendency to garble and/or hellenize place-names. In fact, if the extant Anabasis manuscripts had called Kalah (Nimrud) by the name of Kainai, it would probably have been accepted long ago that this was merely a mistake: ΚΑΛΑΧ with a suffix (or however Xenophon would have written the last consonant, if he recognised it) is close to ΚΑΙΝΑΙ. Lobdell (Reference Lobdell1857: 236–37) indeed suggested that Kainai was identical with Biblical Calah (Kalah), and consequently that the latter was at Qal'a Shergat. The transformation of ΛΙΒΑΛΙ/ΛΙΒΑΝΑ into ΛΑΡΙΣΑ is less straightforward, but Β is not far from Ρ while Λ and Ν are not far from Σ. If the Anabasis manuscripts had attached the name of Larisa to Libana, someone would already have suggested the possibility of scribal error. This is not a question of commonplace corruption in the manuscript transmission. It is more a question of Xenophon's ability to remember foreign names, his habit of making them look Greek, and, if he did at any stage keep notes, his ability to read his own writing.

Since we do not know exactly where the Greeks left the villages of Parysatis, we do not know the starting-point of these 4 stages, and cannot be sure of the speed. The distance by air from the neighbourhood of Ashur to the possible locations of the camps by the Greater Zab is around 90 kilometres, so they may have been moving at slightly over 5 kilometres per parasang. Basically they marched for four days with the Tigris on their left through the Makhmur plain. Various routes are available. The road-system, itself deduced from the locations of known sites, that is offered by the Helsinki Atlas (Parpola and Porter Reference Parpola and Porter2001: maps 28, 30), suggests a route close to the river. An “ancient road system” deduced from satellite photography (Mühl Reference Mühl, Hofmann, Moetz and Müller2012: 83, fig. 5) draws attention rather to the tracks leading north-east from Ashur to Ibrahim Bayis.

On reaching the Zab, the army stopped for three days, or perhaps three nights (2.5.1). Meanwhile the army led by the king's half-brother was also marching north from Miqdadiya on the Royal Road; we know this because it appears a few days later north of Nineveh (3.4.13). So one reason for Tissaphernes’ halting with the Greeks at the Zab may be that he was still waiting for these reinforcements, but he also used the time constructively. He could now act without imperilling significant centres of population, and he arranged a meeting during which many of the Greek officers were captured or killed. The Greeks, ignoring proprieties of oriental despotism, chose substitute officers the same night, burned their baggage, and were on their way the next morning, crossing the Greater Zab, which was some 4 plethra or c. 120 metres wide (2.5.1), on or about 25th October (3.3.6).

Layard, who may be the only person interested in Xenophon to have inspected the terrain carefully by horse, offers two possibilities for the location of the crossing-point. “The ford, by which the Greeks crossed the Great Zab (Zabates) may, I think, be accurately determined. It is still the principal ford in this part of the river, and must, from the nature of the bed of the stream, have been so from the earliest periods. It is about twenty-five miles [40 kilometres] from the confluence of the Zab and Tigris” (Layard Reference Layard1853: 60). This ford was some way downstream of the “modern ferry, where there could never have been a ford” (i.e. Eski Kelek), and, after the crossing, “a march of twenty-five stadia, or nearly three miles [4.8 kilometres] would have brought” the Greeks from the ford to the Khazir. This description locates the ford by a village (c. 36° 15′ 58″ N, 43° 36′ 28″) whose name is given as Zeilan by Layard (Reference Layard1853: map 1 at end). The location fits well with the countryside traversed by the Greeks, according to Xenophon's description, during the next few days. It is also a suitable location as a crossing-point for a branch of the Royal Road passing south-west rather than north-east of Jebel Maglub, in which case there may even have been a pontoon bridge that Xenophon does not mention.

Layard (Reference Layard1853: 60) also offered an alternative: the Greeks might have crossed “below the junction of the Ghazir [Khazir]”. This is less easy to reconcile with Xenophon's account of subsequent movements, but not impossible (cf. Reade Reference Reade1978: 52). A very different crossing-point, immediately above the confluence of the Greater Zab with the Tigris, has been proposed by others (e.g. Boucher Reference Boucher1913: 153–55, map 15). It is doubtful whether there is a ford at this point, the river is far more than 120 metres wide, and it is unclear how the Greeks’ subsequent movements, as described by Xenophon, can be reconciled with the topography.

From the Greater Zab to the Assyrian Khabur

From here onwards, the Greeks and their camp-followers were proceeding alone. They were marching in an oblong formation, ready for battle. They knew that their general direction should be north or north-west, and that they needed regular access to food and water. In choosing the precise route, they had to rely on their own judgement of the terrain, the presence of existing roads or tracks, and guides and translators, whether volunteers or prisoners, who probably had Aramaic as the common language and would tell the truth to save their own or their families’ lives.

On the first day, the Greeks were severely harried from the rear by the Persians (3.3.6–11). They only proceeded about 25 stadia (4.5 kilometres), as far as some villages where they remained a day, reorganising their ranks to include cavalry and slingers. The principal village was presumably the ancient version of one now visible on Google Earth (36° 11′ 35″ N, 43° 33′ 33″ E), close to the left bank of the Khazir above its confluence with the Greater Zab. A mound just south-west of the village appears to be surrounded by a defensive wall, some 100 metres in diameter. Its name, to judge by Felix Jones’ rare map of Assyria (reproduced by Reade Reference Reade1978: 63, fig. 7) and by the Atlas of the Archaeological Sites of Iraq (Salman Reference Salman1976: map of Ninua governorate, between maps 123 and 124), is probably Tell al-Laban.

About 26th October, the Greeks rose early in order to cross a deep gully, ditch or channel (χαράδρα) where they reckoned they would be particularly vulnerable to attack (3.4.1–5). When the Persians did later arrive and cross behind them, some of the Greeks turned and drove them back, with the unusual detail that they even captured eighteen horsemen alive in the channel.

Layard (Reference Layard1853: 60) had little doubt that this dangerous feature was the Khazir river itself, though he did not entirely discount another “ravine worn by winter rains” that was located further south-west. Lobdell (Reference Lobdell1857: 238) remarks that “at its height, a horse can wade the Khazir, and in the autumn it is very low”, so the water itself was hardly an obstacle, but the steepness of the slopes may have been. Another feature in this landscape, however, is or was a system of canals that was created to supply irrigation water to the Assyrian capital of Kalah (Nimrud). In these systems, water was customarily diverted into rock-cut channels running alongside rivers. Part of the Kalah system can be seen above ground at Negub on the Greater Zab, supplemented by tunnels, and there was more of it further upstream (identified by Felix Jones, cf. Reade Reference Reade1978: 63, fig. 7; Davey Reference Davey1985: 51). Surviving traces visible on Google Earth include a straightish rock-cut channel running along the right banks of both the Khazir and the Zab near their confluence (from c. 36° 10′ 29″ N, 43° 32′ 41″ E, to 36° 8′ 52″ N, 43° 31′ 39 E″), and beyond to the south-west. If the original steep sides of this channel were still in reasonable condition, as can be seen from the remains of the same channel below Negub, now largely filled with earth (Fig. 11), they would have constituted a formidable obstacle, in all seasons of the year, to a force attempting to cross against opposition. One can also imagine how horsemen, attempting to escape, might have found themselves trapped in such a channel. This would then be another example of the word χαράδρα being used to describe a man-made rather than a natural feature (cf. Demosthenes 55, Against Kallikles: Ber Reference Ber2003: 84).

Fig. 11 View south-west from Negub along Assyrian channel above Greater Zab. Photograph © J. E. Reade

This day the Greeks could have followed an old Assyrian road for about 22 kilometres to their next halt (3.4.6–9), the large deserted city now universally recognised as the former Assyrian capital-city of Kalah, modern Nimrud (Xenophon's “Larisa” or “Kainai”, see above). They probably passed through the ruins of the outer town between the south-east and north gates, observing frightened natives on the ziggurrat to their left (Fig. 12). A sensible place to camp would have been in the Tigris flood-plain to the north-west. Xenophon repeats a legend about the history of the city, that he could have heard from guides, and gives the length of the 8-kilometre-long city-wall as 2 parasangs.

Fig. 12 View north-west toward Nimrud citadel, possibly the angle seen by Xenophon while passing through the outer town. Photograph © Ken Uprichard

About 27th October (3.4.10–12), the Greeks marched 6 parasangs, perhaps on this occasion 36 kilometres as discussed above, to the vicinity of another deserted city, Nineveh, the greatest Assyrian capital-city, to which Xenophon gives the unexplained name of Mespila (Tuplin Reference Tuplin, Lanfranchi, Roaf and Rollinger2003: 372). They will have been wearing armour and hurrying along an old Assyrian road, but were not attacked. They could have passed the walls of Nineveh and its principal mound of Kuyunjik, and camped a little further north, near the Monastery of Mar Gorgis where the Tigris turns abruptly westward on a loop towards Eski Mosul. Xenophon repeats another legend about local history, and gives the length of the 12-kilometre-long city-wall as 6 parasangs, a figure less silly than it looks because he will have seen the vast earthworks of Sennacherib's canals and moats receding into the distance.

The next day, about 28th October, the Greeks marched 4 parasangs, apparently 20–24 kilometres, before camping at some villages where they found ample supplies. They must have been following a route proposed by Ainsworth (Reference Ainsworth1844: 141). Layard (Reference Layard1853: 61) elaborates: they “probably halted near the modern village of Batnai, between Tel Kef and Tel Eskof, an ancient site exactly four hours, by the usual caravan road, from Kouyunjik. Many ancient mounds around Batnai mark the remains of those villages, from which … the Greeks obtained an abundant supply of provisions.” They had been well advised. This route was preferable to another slightly further west, Route 90a in the Admiralty Handbook (Reference Admiralty1917: 228–38), “over a rolling plain with gravelly undulations”, on the approximate line of the modern highway. That would have led them to the multi-period centre of Tell Jigan and a fertile plain beside the Tigris, so there must have been a direct track to it from Nineveh. The Handbook warns, however, that water is scarce in the first 29 miles from Mosul (i.e. c. 38 kilometres from Mar Gorgis).

This same day, during the march, Tissaphernes reappeared with an even larger force (3.4.13–18), including the army led by the king's brother, last seen by the Diyala. Renewed Persian attacks were repelled by long-distance shooting. Tissaphernes must have by-passed Nineveh and come direct from the Zab along the south-western foot of Jebel Maglub, past a fourth Assyrian capital-city, Khorsabad. This was a possible version of the Royal Road (see above). The Greeks must have joined the Royal Road during this day's march or the next, and stayed on it for a while, but Xenophon fails to mention it.

The Greeks spent a full day at these villages. The next day, about 30th October, they continued on their way, learning the need to adjust their defensive formations (3.4.19–23). Xenophon now ceases to give distances in parasangs, but this stage will have brought them to a point a little short of Faida; it was at this next stop that they presumably made the necessary adjustments, which are duly described. Xenophon then says that “in this way” (τούτῳ τῷ τρόπῳ) they proceeded another 4 stages. Layard (Reference Layard1853: 61) and others have assumed that the 4 stages included the march from Batnai to Faida. The alternative is that “in this way” refers to 4 marches made in the new formation, after Faida. In either case the march of 31st October will have brought them somewhere near Sumel, about 45 kilometres beyond Batnai, west of the modern city of Duhok. By now they could see the range of the Chia Spi or Jebel Abyadh (white hills) impinging from their right, and the ground was becoming more broken (Figs. 13–14).

Fig. 13 View north-west from rock-sculptures past Tell Maltai towards Sumel, along south-west face of Chia Spi hills. Photograph © J. E. Reade

Fig. 14 View south-east from encampment south-east of Derabun towards Sumel, along south-west face of Chia Spi hills. Photograph © J. E. Reade

They proceeded for another three or four days, about 1st–3rd or 1st–4th November, on the last of which (3.4.24–31) they saw a palace of some kind with many villages around it; the road to the place was through high ridges that ran down from the mountain below which the village was located. There is an inconsistency in the manuscript tradition here, with village or settlement (κώμη) appearing first in the plural and then in the singular, but both seem consistent with the existence of a palace surrounded by groups of smaller houses, on a hill with a higher mountain behind, approached by a switchback road. The Greeks were pleased to see the ridges, because the enemy were on horseback, but found other enemy soldiers waiting on the high ground. It seems possible that at this point Tissaphernes was hoping to defeat the Greeks by attacking from two directions at once. They were obliged to divide their forces as they fought their way past successive ridges, but eventually reached the villages. They had many casualties, and rested and recuperated there for three days, or possibly three nights, say about 5th–7th November. The palace turned out to be a government centre for the collection of local produce. Its position on a hill is confirmed by Xenophon's later statement that the Greeks descended from it into the plain (3.4.32), but its location is not certain.

Ainsworth (Reference Ainsworth1844: 143), Layard (Reference Layard1853: 61) and others have assumed that the palace was at Zakho, north of the Chia Spi range on a well-known caravan route corresponding to the modern road north from Sumel. This is consistent with a march of three days, about 1st–3rd November, from Sumel to the palace. Yet the Greeks could not have sighted Zakho before crossing the range. On the other hand Gertrude Bell (Reference Bell1911: 285–87), while remarking that “Xenophon's description is not exactly suited to Zakho”, noted that “the spurs of the Kurdish mountains are covered with fortress ruins”, so the Greeks could in theory have seen a palace almost anywhere. This is the kind of solution suggested by Boucher (Reference Boucher1913: 166), whose map suggests that the Greeks were fighting along the main spine of the mountains, and that their destination was on an elevation south of Zakho itself.

It is also possible, however, and perhaps more likely, that from Sumel the Royal Road headed directly towards the Tigris at Feshkhabur, a distance of some 50 kilometres by air, and that the Greeks followed this route. It would have been a reasonable three days’ march under attack, about 1st–3rd November, through a fertile area where there are numerous ancient sites. The Admiralty Handbook (Reference Admiralty1917: 238–39) says that “there is no satisfactory information as to the character of this route, which as far as Feishkhabur is frequently followed by caravans. … Near Feishkhabur the western end of the Jebel Abyadh has to be crossed; its slopes are here fairly easy.” A place corresponding to Xenophon's palace on a hill, which the Greeks would have reached about 4th November, could then be modern Derabun, on the shoulder of the range beside a plateau north-east of Feshkhabur, about 5 kilometres east of the point where the Assyrian Khabur river joins the Tigris. Google Earth shows the modern road to Derabun from the south-east (between 37° 1′ 50″ N, 42° 27′ 42″ E and 37° 4′ 51″ N, 42° 25′ 51″ E), crossing a series of ridges that run down from the main range to the north-east. Earlier roads will have taken other lines, but the topography seems to suits Xenophon's description. The “easy” slope mentioned in the Handbook could be further west, where the hills drop to the Tigris.

Layard (Reference Layard1853: 56) passed this way too: “Dereboun is a large Yezidi village … Numerous springs burst from the surrounding rocks, and irrigate extensive rice-grounds.” Near the village, according to the Handbook (1917: 242), is “a spring with a large stream called the Derebun, which forms a small, reedy marsh on the plateau. This has to be waded. The springs on the Derebun plateau are warm, and rather brackish.” The wet areas on the hill form a prominent green patch on Google Earth. A remarkably regular conical mound is visible (37° 5′ 14″ N, 42° 25′ 35″ E) beside the village. Derabun also appears in the official gazetteer of archaeological sites in Iraq (Salman Reference Salman1970: 269, files 516, 1334). It is said to have Khabur Ware (i.e. early second millennium b.c.), and occupation of the Late Assyrian, Seleucid and Islamic periods. The identifications in this book, mainly made from surface sherds, are not all reliable, but the importance of Derabun is confirmed by Fiey (Reference Fiey1965: II, 748–54), who explores its history as a Christian monastery and village. A naturally favoured site like this has probably been occupied at all dates.