Introduction to the Sources

In 1912 Thureau-Dangin published the opening lines of a tablet that listed various food items that had been distributed to members of the royal family of Narām-Suen (Thureau-Dangin Reference Thureau-Dangin1912: 82).Footnote 1 At the time, Thureau-Dangin's purpose was to demonstrate that Sar-kali-sarrē was the son and successor of Narām-Suen. He accomplished this by showing that his name listed directly after the king and queen, and was amidst two others who were known to be children of Narām-Suen. Thereby, Thureau-Dangin established that Sar-kali-sarrē was in fact the son of Narām-Suen, and did not succeed Narām-Suen from another lineage.

Rather unfortunately, Thureau-Dangin did not provide a copy or edition of the entire tablet, but only supplied the first few names of the list, which confirmed his point. Footnote 2 In addition to the names of the royal children, Thureau-Dangin also gave the names of four individuals who appeared just after the royal family, but who were not royal offspring. Those names were elite members of the Akkadian court, and included: an unnamed šabra e2 “majordomo” (perhaps Šu'aš-takal, the only šabra e2 known to have served Narām-Suen (see RIME 2.1.4.2003; Foster Reference Foster1980: 29; Westenholz Reference Westenholz1995: 94), Yeṭīb-mer, Ba'lī-qarrād, and Šu-Mama.

Fast-forward several decades to 1980 when this tablet was brought up again by Benjamin Foster, who included it in a study of the royal journeys of the Akkadian kings, Narām-Suen and Sar-kali-sarrē (Foster Reference Foster1980). In his analysis Foster collected evidence from archives across southern Mesopotamia that listed provisions and gifts that had been given out to the royal families and their entourages. The majority of the evidence stemmed from Girsu, where over a dozen texts mentioned items such as fish, livestock, grain, and precious metals, that were distributed to the royal party. Foster highlighted that some of the elite officials listed in these archival documents from Girsu were the same as those previously listed in the document published by Thureau-Dangin, such as Yeṭīb-mer and Ba'lī-qarrād, and concluded that Thureau-Dangin's tablet probably belonged to the same group of tablets, and that all of them, therefore, belonged to the visit of Narām-Suen (Foster Reference Foster1980: 31).

Foster's investigation presented evidence for two royal journeys by the kings of Akkad into Sumer: one by Narām-Suen to Girsu and another by Sar-kali-sarrē to Sumer with the intent to travel to Nippur (Foster Reference Foster1980: 40). Concerning the journey of Sar-kali-sarrē, Foster (Reference Foster1980: 36) observed that a few texts were dated with both a mu-iti date as well as a mention of the king's journey to Sumer and to Nippur:

CT 50, 52: mu-iti date of year 1 month 2, and the subscript: lugal ki-en-gi-še3 i3-im-gen-na-a “(when) the king went to Sumer.”

MCS 9, 247: mu-iti date of year 1 month 6, and the subscript: lugal ki-en-gi-še3 i3-im-gen-na-a “(when) the king went to Sumer.”

BRM 3, 26: mu-iti date of year 1 month 7, and the subscript: lugal Nibruki im-gen-a “(when) the king went to Nippur”.

In addition to these texts, four others without mu-iti dates mention the royal journey: L 2940 (JNES 12, 42) mentions lugal ki-en-gi-še3 i3-gen-na “(when) the king went to Sumer”; MC 4, 27 sar-ga-li 2-LUGAL-ri 2 ki-en-gi-še3 ba-gen-na “(when) Sar-kali-sarrē went to Sumer”; and both NBC 6848 (JNES 12, 37) and L 1212 + 4672 (JNES 12, 41) mention a royal journey to Nippur: lugal Nibruki im-gen-(n)a “(when) the king went to Nippur”.Footnote 3

Foster equated these subscripts with the year name of Sar-kali-sarrē: mu Sar-ga-li 2-LUGAL-ri 2 ki:en:giki-še3 im-ta-e3-da [x]-sag-ga2 mu-us2-bi “year Sar-kali-sarrē went down to Sumer … year after” (PBS 5, 38; Foster Reference Foster1980: 39; for the year date and suggested restorations see Sallaberger and Schrakamp Reference Sallaberger, Schrakamp, Sallaberger and Schrakamp2015: 47). Moreover, he pointed out that because the journey to Nippur in BRM 3, 26 is dated to just one month after the journey to Sumer (in MCS 9, 247), these two events are very likely to be part of the same royal visit to southern Mesopotamia (Foster Reference Foster1980: 40).

Yet Sallaberger (Reference Sallaberger and Wilhelm1997: 150-151) was unconvinced by Foster's equation of the journey to Nippur and the journey to ki-en-gi. He argued that the verbal forms used to describe the journey, ba/i3-(im)-gen-na-a vs. im-DU-a, indicate a perfective and imperfective difference between when the journeys occurred. Furthermore, he asserted that ki-en-gi referred to the region around Uruk (in the south) and was an area distinct from Nippur. Thus, he considered the descriptions of the journey to Nippur as separate event from the king's journey to ki-en-gi. The argument, however, is not particularly convincing for a few reasons: 1) the observable differences between the verbal chains (i.e. the different prefixes and suffixes in ba/i3-gen-na-a vs. im-gen-a) is hardly evidence to suggest a perfective or imperfective reading of the verbal root; and 2) while ki-en-gi may have been a distinct region in documents dating to the Fara period, it is unclear if that distinction was still used for the same specific region in Sumer or if it was applied more broadly to encompass all of Sumer, in the Akkadian period. Moreover, the king's journey to ki-en-gi and the journey to Nippur are both dated to a single year, the first year of the ensi-ship of Mesag, and therefore there seems to be no reason to consider the trips as separate events, but all part of a single royal journey.

The mu-iti dates with these subscripts are exceptional because they indicate that the visit of Sar-kali-sarrē to Sumer was extensive – lasting at least six months, if not more. Furthermore, these dates indicate that this event occurred during the first year of the ensi-ship of Me-sag at Umma.Footnote 4 However, precisely in which year of the king's reign this trip occurred is not clear, but most scholars agree that it was likely to have been early, probably the first or second year (Sallaberger and Schrakamp Reference Sallaberger, Schrakamp, Sallaberger and Schrakamp2015: 47 and cited lit.).

It is also clear from the evidence that Sar-kali-sarrē made several stops on his visit to the south. One of those stops was at Umma. MCS 9, 247 and 232, record lavish goods (such as oil and fat, grain products, dates, raisins, fruit strings, and spices) that were doled out for a banquet “when the king came down to Sumer” (Foster Reference Foster1980: 36). Additionally, MC 4, 27 records that livestock, birds, foodstuffs, and spices, were given for the same occasion. Moreover, evidence from Zabala (CT 50, 52) lists metals, garments, animals, and other products that were given to the king and queen as offerings during the royal visit.Footnote 5

Another city with evidence for the royal visit, and perhaps the ultimate destination of the king, is Nippur. As several of the subscripts mentioned above demonstrate, the king's journey to Sumer included a journey to Nippur. Several documents from other cities, such as Isin, Umma, and Girsu, all record lavish goods being sent there (Foster Reference Foster1980: 37-39). Westenholz (Reference Westenholz1995: 92) has argued that several of the tablets from the Onion Archive may have been written in conjunction with the royal visit of the Akkadian king to Nippur.Footnote 6 Prosopographic ties from the administrative documents do support that it was indeed the case. For example, OSP 2, 138 names three high officials of the Akkadian court, Dāda, Ba'lī-qarrād, and Nahšum-šanat, as recipients of onions, turnips, and coriander. The same three individuals are also present in distribution lists from Girsu, which were probably written when the king visited that city on his visit to Sumer (see below).

The purpose of Sar-kali-sarrē’s trip is never specifically indicated, but it seems probable that the king wanted to cultivate good will and loyalty among his subjects (Sallaberger and Schrakamp Reference Sallaberger, Schrakamp, Sallaberger and Schrakamp2015: 39). The journey may have been done to prevent another mass rebellion in Sumer, such as the Great Rebellion that occurred during the reign of his predecessor, Narām-Suen. In order to accomplish this, the king must have made his way to several important cities in the south. The evidence from Umma, Nippur, and Girsu, all suggest that this was indeed the case. Interestingly, a list of onion disbursements from Nippur, OSP 2, 135, states that onions were given out: obv. 4. lugal igi-nim-ta / 5. i3-im-gen-na-a “when the king came from the upper land”, and obv. 6. lugal sig-ta / 7. i3-im-gen-na-a “when the king came from the lower land”. These two notes suggest the king's journey was a tour of sorts encompassing both northern and southern territories.

While some scholars have argued that the reason for the king's journey was a coronation at Nippur (Foster Reference Foster1980: 40; Foster Reference Foster2016: 22-23; and Westenholz Reference Westenholz1995: 27 and 89 n. 79), such an event in Nippur seems unlikely.Footnote 7 Why would the king of Akkad need to cement his kingship in Nippur when the political and religious capital of the empire was at Akkade? To be clear, Nippur was a city of great importance to the Akkadian kings: Sargon presented the defeated Lugalzagesi in shackles to the gods at Nippur (RIME 2.1.1.1), a year name commemorates that Narām-Suen received a heavenly weapon from Ekur (see Sallaberger and Schrakamp Reference Sallaberger, Schrakamp, Sallaberger and Schrakamp2015: 45), and Narām-Suen and Sar-kali-sarrē both invested in renovating the Ekur temple, as several year names and building inscriptions attest to (see Sallaberger and Schrakamp Reference Sallaberger, Schrakamp, Sallaberger and Schrakamp2015: 46-47; and e.g. RIME 2.1.4.15 and RIME 2.1.5.1). But the Akkadian kings did not view Nippur with the same centrality as their Sumerian neighbours; the kings of Akkad may have taken the title king of Kish, but no Akkadian king gave Nippur the same political or religious significance. Moreover, Narām-Suen made a powerful statement when he presented himself as a god in Akkade. The Bassetki inscription clearly states that his cult center was not erected at a Sumerian religious center such as Nippur, but at Akkade (see RIME 2.1.4.10). With this statement Narām-Suen elevated the dominance of Akkade even further, not only as the political capital of the empire, but now as a religious center too. Thus, the suggestion that Sar-kali-sarrē held a coronation ceremony at Nippur is a rather Sumero-centric notion, and if such an event did occur it could only have been a platitude for the people of Sumer and not a symbol that held significance to the citizens of Akkad.

Instead, Sar-kali-sarrē probably made a point of visiting Nippur specifically to begin his renovations to the Ekur temple. In addition to the building inscriptions that mention his building of the Ekur in Nippur (see RIME 2.1.5.1-3), at least three year names of Sar-kali-sarrē are concerned with the event, so it was clearly a project of great importance (for the year names see Sallaberger and Schrakamp Reference Sallaberger, Schrakamp, Sallaberger and Schrakamp2015: 47; FAOS 7 D-29, D-30 and D-31):

in 1 MU sar-ga-li 2-LUGAL-ri 2 [us 2]-⸢se 11⸣ E2 dEN.⸢LIL2⸣ [in] NIBRU[ki iš-ku-nu]

“Year Sar-kali-sarrē laid the foundations of the temple of Enlil in Nippur” (same year name occurs in Sumerian).

mu sar-ga-li 2-LUGAL-ri 2 puzur4-eš4-dar šagina(KIŠ.NITA) e2 den-lil2 du3-da bi2-gub-ba-a mu ab-us2-a

“Year following the year (when) Sar-kali-sarrē put in office the general Puzur-eshtar to build the temple of Enlil.”

in 1 MU sar-ga-li 2-LUGAL-ri 2 [DUL3]-su GAL / [u 3 NIG2].DE2.A KU3.SIG17 / [ba-b]i 2 E2 dEN.LIL2 [ip]-tu-qu 2

“Year Sar-kali-sarrē cast his great [statue and] the golden [mold of the gate] of the temple of Enlil.”Footnote 8

It stands to reason then that Sar-kali-sarrē may have kicked off the building works with a grand tour of the important city centers in Sumer, before he ultimately made his way to Nippur to begin the undertaking. Lavish goods were sent from cities throughout Sumer for the occasion, such as from Umma (BRM 3, 26), Isin (JNES 12, 37), and Girsu (JNES 12, 41-42). Processing through the land meant that the king could foster good relations with his subjects and hear oaths of loyalty. Likewise, a large-scale construction project at the most important religious site in Sumer was a further demonstration of Akkadian interests in the south.

Sumer had a history of rebellions under the Akkadian kings; from its initial conquest by Sargon until the end of Akkadian supremacy, nearly every king faced a revolt. In light of the massive uprising against Narām-Suen, Sar-kali-sarrē may have felt the need to quell any poten-tial future rebellions; perhaps he sought to achieved this with a sign of good will toward his subjects and a display of Akkadian might. The journey inspired awe and fear: awe at the lavish celebrations held throughout the land and the beginning of an impressive building project at an important religious site; and fear inspired by the spectacle of Akkadian military might as the administrative tablets from Girsu record that at least five of the people who traveled with the king held the title šagina, the highest military rank below the king.Footnote 9

The Visit to Girsu

In Foster's initial analysis of the tablets that attest to a royal visit at Girsu, he saw only one royal visit at the time, which he attributed to Narām-Suen (Foster Reference Foster1980: 29). Yet, while RA 9, 82 shows that Narām-Suen visited Girsu, there is reason to believe that not all of the documents attest to a single visit, but were records of two royal visits to Girsu (Visicato Reference Visicato, Melville and Slotsky2010: 435). The administrative tablets in question mention goods distributed to the royal family and their entourage, but there is a distinct difference that divides the tablets: one group mentions the king, queen, their children, and elite officials; and another group lists only the king, queen, and their elite entourage, without mention of any royal children. Such a conspicuous absence of royal children in so many of the documents is significant and suggests two separate occasions of royal visits.Footnote 10

To the first visit belongs the tablet published by Thureau-Dangin in RA 9, which specifically names the children of Narām-Suen, and MLC 114 (JNES 12, 30) that names Sar-kali-sarrē as a recipient of sheep. In addition, Foster (Reference Foster1980: 36) associates RTC 221-229 with this visit, which list a plethora of objects, such as golden thrones, footstools, and beds, among other lavish accoutrements, that were given to the royal family. Notably RTC 221-223 mention a lugal, nin, dumu lugal-me “sons of the king” and a dumu.munus lugal “daughter of the king” as recipients, which accords with the two sons and one daughter of Narām-Suen mentioned in RA 9, 82. Moreover, a certain Ur-ba-gara2 is named as a responsible person in most of these texts, which further supports the idea that RTC 221-229 belong to a single occasion (Foster Reference Foster1980: 36).

The association of RTC 221-229 to the visit of Narām-Suen has been disputed since Foster's initial analysis. Maeda (Reference Maeda1988), Carroué (Reference Carroué1994), and Visicato (Reference Visicato, Melville and Slotsky2010) all believe these tablets belong to a period at the end of Sargonic rule (at the earliest) or more likely a period subsequent to Sargonic rule at Girsu. Their reasoning is based on two factors: 1) the year name in RTC 221: mu e2 dnin-gir2-su-ka ba-du3-a “year when the temple of Ningirsu was built” and 2) the presence of certain officials as recipients/distributors in these texts, notably Ur-ba-gara2. Visicato (Reference Visicato, Melville and Slotsky2010: 446) argues that the career of Ur-ba-gara2 extends from late in the reign of Sar-kali-sarrē until the reign of Gudea of the Lagash II dynasty, and so RTC 221-229 probably belong to a royal visit subsequent to the Akkadian period. The prosopographic evidence he uses seems to favour this line of reasoning, but Sommerfeld (Reference Sommerfeld, Sallaberger and Schrakamp2015: 276-77) has pointed out several caveats to the analysis, and has shown that the Girsu official Ur-ba-gara2 attested in the Sargonic period tablets cannot satisfactorily be linked to the namesake individual from the Lagash II tablets.

That being the case, Carroué (Reference Carroué1994: 56) points out that RTC 221-223 include property for up to three royal children – the same number of children who accompanied Narām-Suen to Girsu. Still, because RTC 221-223 cannot be linked to any particular king without doubt, a later king who visited Girsu could have done so with their own family.Footnote 11 Furthermore, Visicato (Reference Visicato, Melville and Slotsky2010: 447) notes that RTC 221-229 were discovered in a cache of tablets that was separate from the other Akkadian texts, in a group that spans the post Akkadian to Ur III periods. Considering these points then, it cannot be said with certainty that RTC 221-229 refer to the visit of Narām-Suen.

The other group of texts from Girsu, those that mention only a king and queen, and no royal children, document a different royal visit to Girsu, probably by Sar-kali-sarrē (Visicato Reference Visicato, Melville and Slotsky2010: 435). To this group belong: CT 50, 172 (= CUSAS 26, 174); ITT 1, 1472; L 4699 (JNES 12, 40); L 9374 (JNES 12, 41); ITT 2, 4566; RTC 127, 134, and 135.Footnote 12 These texts list livestock, fish, eggs, various grain products, and precious metals that were distributed to the royal family and their retinue. The unnamed king on this second royal journey is probably Sar-kali-sarrē for prosopographic reasons, especially. Firstly, one of the Girsu texts attests to goods that were acquisitioned “when the king came down to Sumer” (L 2940), mentions a certain Sarru-ṭāb as a recipient. The same individual is also named among the highest officials from the second royal journey, such as CT 50, 172, just after the king and queen. But, he is not mentioned among the high officials who accompanied Narām-Suen in RA 9, 82.Footnote 13 Secondly, there are several prosopo-graphic links between the names listed in the texts from the second group and those from other archives that date to the reign of Sar-kali-sarrē. For example, one of the high officials from CT 50, 172 is Dāda the šabra, who is almost certainly the same as Dāda the šabra of the queen of Sar-kali-sarrē, whose seal impression was discovered on a bulla at Girsu (see RIME 2.1.5.2003).

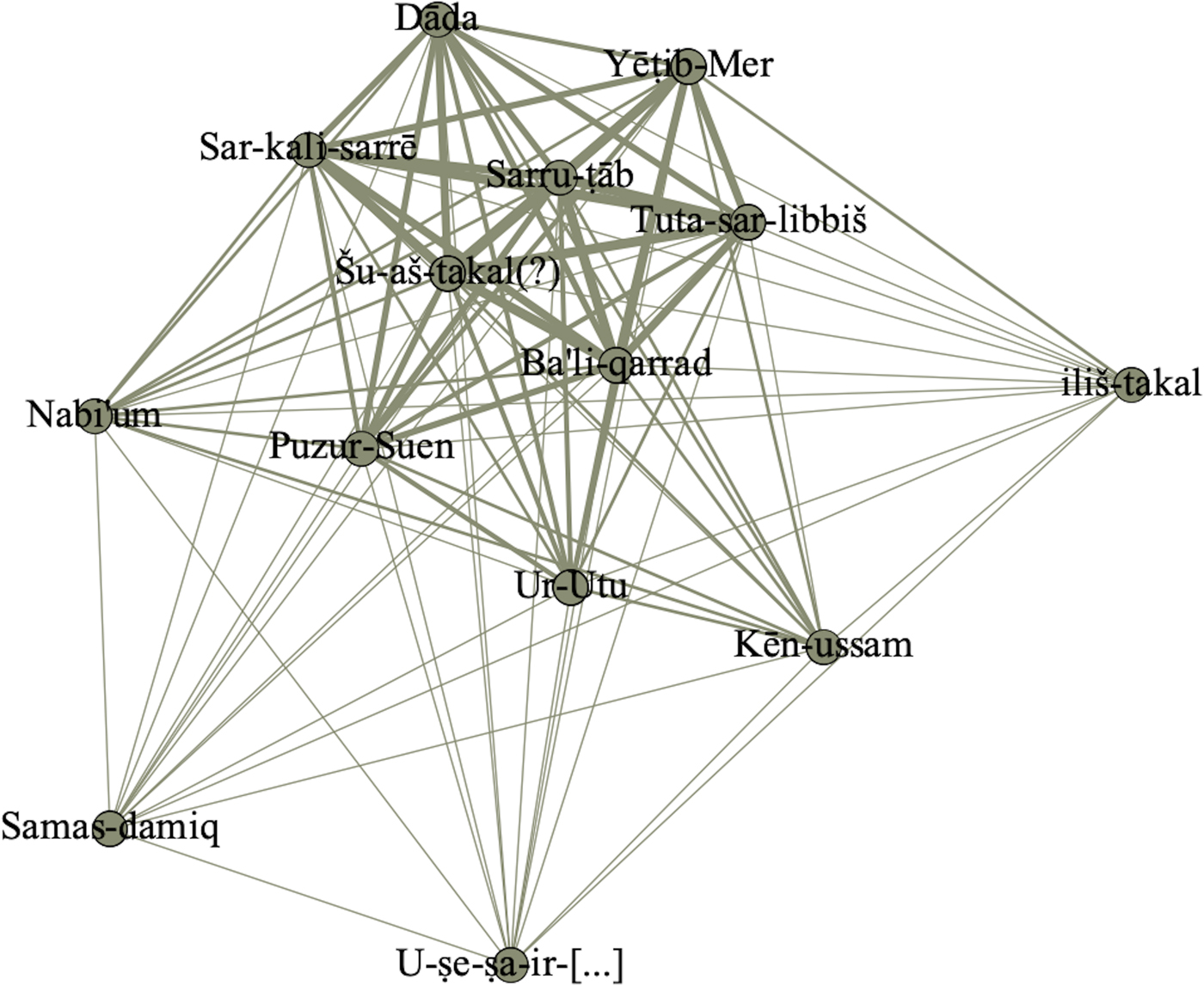

No tablet gives a complete list of all the individuals present for the royal visit, but the most comprehensive tablet is CT 50, 172 (= CUSAS 26, 174). Especially conspicuous is that none of the persons among the royal party were local ensis of Sumer. Instead, the highest officials who traveled with the king and queen were individuals for whom no title was given. That distinct lack of title implies their elite status did not derive from a professional designation, but from social class and wealth. Indeed, this party must have been quite grand, as there are at least five generals, šagina, who accompanied the king at the time. The royal party also included judges, a scribe, a doctor, an interpreter(?) (lu2-eme),Footnote 14 a constable, and even a cleaner, among others. Because no singular tablet attests to every person present with the party, only a core group of officials who appear several times can confidently be associated with the visit. Table 1 lists the individuals according to CT 50, 172, as it is the most intact tablet with the most names that appear on the tablets associated with the royal visit. The simultaneous presence of so many names in these documents, especially the elite, cannot be mere coincidence, so it is almost certain that they all attest to the same visit in Girsu. The same data are also represented in Fig. 1.Footnote 15

Table 1 Persons attested in the documents from the royal visit of Sar-kali-sarrē to Girsu listed as they appear in CT 50, 172 (with collations from CUSAS 26, 174).Footnote 15

1 Reference to tir-ku3 in ITT 1, 1472 is uncertain because the name is broken, but it would be an appropriate restoration given the other persons listed in the text who also occur in texts from the same visit.

Fig. 1 Depicted here is a Social Network Analysis model of CT 50, 172, with the royal family and the most important members of the Akkadian elite. The lines indicate the number of times two individuals are attested in the same tablet. Thus, the thicker the line appears, the more often the two individuals appear together in the tablets from Girsu.

The Akkadian Elite

The high ranking individuals found in the lists from the king's visit to Girsu are also attested elsewhere in Sargonic archives that date to the time of Narām-Suen and Sar-kali-sarrē. Their prosopographic associations are important markers that establish synchronisms between archives.Footnote 16 Furthermore, those links strengthen the argument that the visit to Girsu was by Sar-kali-sarrē, and that this same journey took him to Nippur too, because Yeṭīb-Mer, Ba'lī-qarrād, Puzur-Suen, Dāda šabra, Ilum-dān šu GAL5-LA2-um, and Nahšum-šanat all appear in documents from Nippur. What follows is a brief overview of these officials and their attestations elsewhere among records from the Sargonic period.

Yeṭīb-Mer

“Mer is good/sweet”. Spelling E 3-ṭib-me-er. Other attestations: CST 18; CUSAS 19, 78; CUSAS 13, 185; CUSAS 27, 202; CUSAS 26, 248; STTI 14, 127, 148, 181; USP 18.

The name of this individual is interpreted from parallels such as ni-wa-ar-me-er (Niwar-Mer) the šagina of Mari (RIME 2.3.4.1). Yeṭīb-Mer is a high ranking official attested under both Narām-Suen and Sar-kali-sarrē. He apparently held large tracts of land in both Umma and Lagash provinces, several times more than leading local religious and administrative officials (Foster Reference Foster2016: 71). Yeṭīb-Mer also appears in STTI 148 with the title šabra e2 “majordomo”, which he must have attained sometime during the reign of Sar-kali-sarrē.Footnote 17 Given the amount of land he held and his rank among the highest officials of the Akkadian court, he must have been a person of great importance. His subordinates are attested in the Onion Archive from Nippur in OSP 2, 124, and at Maškan-ili-Akkade in CUSAS 27, 202. The latter two attestations are important because they demonstrate the longevity of his career during the reign of Sar-kali-sarrē.

Puzur-Suen

“Secret/treasure of Suen.” Spelling PUZUR4-dEN.ZU Other attestations: HSS 10, 12 (= FAOS 19, Ga 9); OSP 2, 128, 131, 132.

Puzur-Suen is attested in archives dating to both Narām-Suen and Sar-kali-sarrē. This individual is attested in a letter found in the Gasur archive (alongside Kēn-ussam), and as a recipient of onions in the Nippur Onion Archive. He is not given any title in any of these mentions, but in each case he is named alongside other prominent individuals, so it is very likely to be the same person. There are a few other mentions of a namesake individual, such as in the Himrin archive or from Kiš (in MAD 5), but those persons are either untitled, given a patronymic, or appear in a context without prosopographic links that could connect to this high status person attested at Girsu.

Ba'lī-qarrād

“My lord is a hero.” Spelling BAD-li 2-UR.SAG. Other attestations: STTI 158; OSP 2, 138; CST 27.

This individual is attested at Girsu, Umma, and Nippur in texts dateable to the reigns of Narām-Suen and Sar-kali-sarrē. He accompanied Narām-Suen on his visit to Girsu, as he appears in RA 9, 82 alongside the king's children, Yeṭīb-Mer, and Šu-Mama. In one text from Girsu, STTI 158, an individual of the same name is given the title gal-sukkal “chief advisor(?)”, suggesting it is indeed the same high status individual. This may be designation used to describe the other persons who are clearly of importance but never seem to have any particular title, such as Yeṭīb-Mer, Puzur-Suen, and Sarru-ṭāb.

Sarru-ṭāb

“The king is good/sweet.” Spelling Sar-ru-DUG3. Other attestations: ITT 1, 1080 (= FAOS 19, Gir 8); L 2940 (= JNES 12, 42).

Sarru-ṭāb is among the highest officials, listed just after the king and queen in the above documents and without title. He is only attested outside of these documents in two instances: one being a letter asking Lugal-ušumgal, the ensi of Lagaš, for a significant quantity of grain rations and textiles (in ITT 1, 1080); and the other an administrative document from Girsu stating that Sarru-ṭāb was the recipient of some number of sheep (JNES 12, 42). That same document also mentions that some of those sheep were disbursed for the journey of the king to Sumer (lugal ki-en-gi-[še3] i3-gen-na).

Dāda

“Beloved/favourite.” Spelling Da-da. Other attestations: OSP 2, 138; ITT 1, 1077; JCS 55, 49; MAD 5, 67.

Dāda is documented as the šabra of the queen of Sar-kali-sarrē, whose seal appears on a bulla from Girsu (RIME 2.1.5.2003). Another appearance of the same Dāda is in OSP 2, 138, alongside other high-ranking members of the royal party who are mentioned in the Girsu lists above. Otherwise, Dāda ši NIN “of the queen,” who is very likely the same man, is attested on a document from Umm-el Jir, MAD 5, 67, which records that he holds a large area of land in that region.

An interesting administrative document ITT 1, 1077, names Šubur ensi, Dāda šabra, and Nabi'um dub-sar as recipients of fattened sheep and lamb. The coincidence of these names is important because the first man is attested as an ensi of Umma (RIME 2.11.11.2001 (seal) and TIMA 1, 116, 133, and 134). It has been suggested that Šubur was ensi of Umma after the reign of Sar-kali-sarrē (Cripps Reference Cripps2010: 10). But with the presence of Dāda šabra in ITT 1, 1077, that seems less likely because Dāda is attested at Girsu and Nippur at the time of the royal visit. Given that the royal journey probably happened early in the reign of Sar-kali-sarrē, Dāda is probably the first of the three known individuals who served as šabra of the queen.Footnote 18 Consequently, Šubur must have served as ensi of Umma at the same time that Dāda held the position of šabra, suggesting that Šubur was probably the predecessor of Me-sag at Umma.Footnote 19 A recently published letter addressed to Me-sag demonstrates that Me-sag was still ensi of Umma in the latter half of the reign of Sar-kali-sarrē when the Gutians threatened Akkadian supremacy (see Kraus Reference Kraus2018). Moreover, another Old Akkadian letter demonstrates that Yiškun-Dagan (another of the queen's šabras) was active when the Gutians were disrupting agricultural production in Sumer, in the latter half of the reign of Sar-kali-sarrē (see FAOS 19, Gir 9). That concordance of Mesag and Yiškun-Dagan further supports that Dāda served as šabra of the queen before Yiškun-Dagan, and thus it is more likely that Šubur was ensi of Umma before Me-sag, rather than after.

Iliš-takal

“Trust in the god.” Spelling I 3-li 2-iš-da-gal.

No person with this name is ever attested with the title šagina, as in the Girsu texts above. There are two known prominent officials with this name: 1) the servant of Tuṭṭanabšum, daughter of Narām-Suen and entu-priestess of Enlil in Nippur (e.g. attested in CUSAS 27, 206); and 2) the governor of Sippar who was defeated by Narām-Sin in the great rebellion (RIME 2.1.4.6). Given the number of officials in these Girsu texts who are also known from the reign of Sar-kali-sarrē, it is unlikely that the Iliš-takal mentioned here is the same person as the one who was defeated by Narām-Suen in the Great Rebellion. While it may be possible that he is the same person who serves as a servant of Tuṭṭanabšum, such a connection cannot be established with certainty.

There are other occurrences of the name throughout Sargonic archives, but never with title or context that would allow one to assume they are identical to the high official listed in these disbursement texts. One plausible connection is a letter of complaint (FAOS 19, Ad 8) written to the king by a certain Iliš-takal, wherein the man requests that the king send a chariot to him.

Kēn-ussam

“Make firm the foundation.” Spelling Gi-in-us 2-sa-am. Other attestations: HSS 10, 12 (= FAOS 19, Ga 9); OAIC 9 (?).

This individual is attested under both Narām-Suen and Sar-kali-sarrē. He appears in a letter concerning the ensi in the Gasur archive without any title and alongside Puzur-Suen; the appear-ance of both names is so unique that it can hardly be anyone else. His presence in that archive, which probably dates to the latter part of Narām-Suen's reign or the reign of Sar-kali-sarrē (Foster Reference Foster1982b: 39), shows that he remained in a powerful position spanning the reign of both kings. A servant of someone who is probably the same individual is attested in a sworn statement from Ešnunna, OAIC 9.

Samsum-damiq(?)

“Utu/Šamaš is good/beautiful.” Spelling dUTU-SA6. Other attestations: JCS 55, 49; ITT 2, 4690.

While this name is written with logograms only, it may in fact be an Akkadian name because the other šaginas in the king's retinue all have Akkadian names. This individual is attested only in texts dated to Sar-kali-sarrē. Of particular interest is the mention of this individual, with the title šagina, in a text from Adab (JCS 55, 49) that concerns bows and arrows given for a mašdaria. According to Civil (Reference Civil2003: 49), the text is datable to the reign of Sar-kali-sarrē or later, although in that same document a certain Dāda šabra is mentioned, suggesting that the tablet dates to the first part of Sar-kali-sarrē’s reign, rather than after it.

Nabi'um

“The one who is named.” Spelling: Na-bi-um.

There are numerous attestations of the name Nabi'um among the Sargonic archives, such as at Eshnunna, Adab, Susa, Umma, and Nippur. Yet, none of them bear the title šagina, and so the Nabi'um who traveled on the king's journey cannot reliably be identified as any of the others without further evidence.

Uṣe-ṣa'ir-[…]

“[His/her?] exalted one has come out.” Spelling: U-ze 2-za-ir 3-[…].

Westenholz (Reference Westenholz2014: 147) suggested to restore the name as U-ze 2-za-ir 3-[si-in], but the presumed horizontal wedges of the proposed SI might be a single vertical wedge belonging to IR3.Footnote 20 No individual bearing this name can be found within any of the Sargonic archives. Such an absence of evidence is either an accident of archaeology, or could suggest that his interests and assets lay outside of Sumer, possibly in the Akkadian heartland or northern Mesopotamia.

Ilum-dān

“The god is mighty.” Spelling DINGIR-dan. Other attestations: OSP 2, 128, 130, 132; CUSAS 13, 116, 118, 119; CUSAS 26, 194; CUSAS 27, 194.

This individual occurs with the title šu GAL5.LA2-um in Sargonic archives. The translations of this profession have included “constable” (Foster Reference Foster1980: 31) and “a draft or recruiting officer” (Westenholz Reference Westenholz1995: 94), or something of the sort.Footnote 21 In addition to the above Girsu texts, he appears at Adab, Nippur, Maškan-ili-Akkade, and the Lugal-ra archive. The latter two archives are especially interesting because they date to the reign of Sar-kali-sarrē, which further supports the idea that the unnamed king mentioned in these Girsu documents was indeed Sar-kali-sarrē.

Nahsum-sanat

“The year is plentiful.” Spelling Na-ah-sum-sa-na-at. Other attestations: RTC 127; OSP 2, 135, 137, and 138; CUSAS 27, 48 and 193.

This individual is mentioned in one of the Lagash texts mentioned above, RTC 127, with the title šabra e2 giš-kin-ti. I single him out here because, while he is not listed in CT 50, 172, the same name is found at Nippur in the Onion Archive and at Maškan-ili-Akkade in CUSAS 27, 48 and 193. The name stands out and occurs in such few places that it can hardly be any other person. His presence in both the Girsu and Nippur texts further supports the idea that these documents attest to the royal sojourn of Sar-kali-sarrē.

Ur-Utu

“Servant of Utu.” Spelling Ur-dUtu.

One of the names that is especially noteworthy is Ur-Utu. In the distribution lists above, this individual is given three separate titles. While one might assume that these are three different persons, because he is always attested among the same high ranking individuals, it is likely he is one and the same person and holds multiple titles.

It is not a common occurrence that a single individual can be shown to have multiple titles or that they can be traced through several administrative documents.Footnote 22 In this case, however, Ur-Utu stands out as an exceptional case. In three documents listing rations given out the royal party at Girsu, Ur-Utu is mentioned in close proximity to the elite just below the king and queen. In CT 50, 172, he is listed as a judge, but his name is first in that list, and he receives one basket of fish more than the other judges, the same number of baskets given to the šagina who precede him. Then, in ITT II, 4699, he appears with a different title and is called šu GAL5.LA2-um, a position that was also held by Ilum-dān in CT 50, 172:

L 4699 (JNES 12, 40)

Names in bold also occur in CT 50, 172.

Note that in this text Ur-Utu also receives the same number of rations as Puzur-Suen, who is an elite member of the royal entourage, appearing without title in CT 50, 172 above.

Subsequently, Ur-Utu appears in a list of eggs being distributed to the royal party. Here, Ur-Utu is attested among the ranks of persons designated as šagina. The identity of the two other individuals named alongside him, Kēn-ussam and Nabi'um, is assured given their attestations in CT 50, 172.

ITT 1, 1472

Names in bold also occur in CT 50, 172.

As these three tablets (CT 50, 172, L 4699, and ITT 1, 1472) show, a single person named Ur-Utu concurrently held three different titles. The prosopographic links between these tablets demonstrate that they are not three separate individuals.

In addition to this Ur-Utu, there are other individuals named Ur-Utu who appear with elite titles or in significant contexts:

1. Ur-Utu – title: ensi. A certain Ur-Utu is known to have been ensi of Ur during the reign of Narām-Suen, attested in the letter RTC 83 (=FAOS 19, Gir 26): 10. ur-dutu-ke4 / 11. [n]am-ensi2 uri5ki-ma / 12. dna-ra-am-[dEN.ZU-ra] / 13. i-na-ak-ka, “(when) Ur-Utu acted as ensi of Ur for Narām-Sin…”. Ur-Utu the ensi is named in an administrative document from the Me-sag Archive (Salgues Reference Salgues, Barjamovic, Dahl, Koch, Sommerfeld and Westenholz2011: 254 n. 8). Ur-Utu ensi, is named in ITT 5, 6689 (date uncertain). Although, it has been postulated that this reference is to an entirely different ensi of Lagash of the late Akkadian period (Cripps Reference Cripps2010: 10 and 110; Glassner Reference Glassner1986: 44).

2. Ur-Utu – title: šabra. In CST 27 (see Foster Reference Foster1982a: 353;Footnote 25 Umma C archive, Sar-kali-sarrē).

3. Ur-Utu – title: king of Uruk. SKL, 5th king of the Uruk IV dynasty (late/post Akkadian; see Sallaberger and Schrakamp Reference Sallaberger, Schrakamp, Sallaberger and Schrakamp2015: 19).

4. Ur-Utu – no title. In the letter FAOS 19, Um 5.Footnote 26 Notably, Ur-Utu states “Akkad is king” (or “there is a king in Akkade”) and that men of Akkad should not be killed, but sent to Ir3-gi4-gi4. The name Ir3-gi4-gi4 is uncommon enough that it is most likely a reference to the first king of Akkad who succeeded Sar-kali-sarrē in the period of confusion following his reign.

It seems fair to say that we may reconcile the initial two attestations of Ur-Utu ensi in group 1, since the timeline matches both of them. The identification of the third Ur-Utu ensi mentioned in the Girsu archive, however, is unclear, as the tablet could be Sargonic in date or perhaps from a later period (perhaps referring to the SKL ruler of Uruk?). The second Ur-Utu, the šabra at Umma, is only referred to in a document recording land holdings at Umma, and so is possibly the same individual as the one who traveled with the king on his sojourn to Sumer, but that link is entirely speculative. Furthermore, the Ur-Utu, ruler of Uruk, is unlikely to be identical with any of the same persons mentioned above, as such a link would require a significant reinterpretation of chronology. As for the last individual named Ur-Utu, in the letter from Umma, this person could plausibly be linked to either the Ur-Utu who traveled with the king on the sojourn to Sumer or Ur-Utu šabra. Because of the mention of Ir3-gi4-gi4, the successor of Sar-kali-sarrē, the dating of FAOS 19, Um 5 is quite specifically at the end of Sar-kali-sarrē’s reign or in the months immediately after. Thus, the Ur-Utu named therein must have been active during the reign of Sar-kali-sarrē, and the most likely candidates, therefore, are the Ur-Utu traveling with Sar-kali-sarrē or the Ur-Utu šabra attested at Umma.

To sum up, there is evidence demonstrating that the journey of Sar-kali-sarrē to Sumer stopped at several cities and lasted for at least half the year, if not more. The distribution lists from Girsu show that at least two royal visits were made to the city: the first by Narām-Suen, his family, and an entourage; and the second by Sar-kali-sarrē, his queen, and an entourage. With the king traveled some of the highest officials of the Akkadian court, many of whom can be traced across several archives, establishing chronological and prosopographic ties (see Fig. 2). Those ties are especially apparent between Nippur and Girsu, suggesting that both cities were part of the same sojourn, and reinforcing Foster's (Reference Foster1980: 40) proposition that the two visits are one and the same. The king's purpose for undertaking such a journey through southern Mesopotamia is never explicitly stated, but fostering good relations with his subjects and hearing oaths of loyalty are the most likely reasons. In addition, I suggest that Sar-kali-sarrē went to Nippur, not for a coronation, but to kick off his renovations to the Ekur temple, after which at least three years are named. The royal sojourn of Sar-kali-sarrē was a chance for the Akkadian king to demonstrate his interest in the land of Sumer and reinforce Akkadian sovereignty there. Knowing that his father and other predecessors had difficulty ruling Sumer, Sar-kali-sarrē must have wanted to begin his reign with a show of strength. Somewhat ironically, his reign was the beginning of the end of Akkadian supremacy in Mesopotamia.

Fig. 2 Illustrated in this graphic is a model of the above attestations of the Akkadian elite who appear in the tablets related to the royal journey. The lines show the archives to which an individual can be connected.