Introduction

The tablets published here come from a collection of objects deposited at the Iraq Museum (IM) after they were confiscated in 2004. These tablets originated mainly from illegal excavations hence their provenance and context are undocumented. One tablet was given the inventory number IM 183636 and the other IM 201688 in accordance with the decision of The State Board of Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH). The Directorate of the Iraq Museum kindly granted permission to Mohannad Khalaf Jamen Al-Shamari in 2017 to copy and publish these texts. The following article gives a brief overview of Babylonian marriage law and outlines the formulaic language used in these documents, with particular reference to the language found in the bilingual legal handbook Ana ittīšu (MSL 1), before presenting the texts in photograph, copy, transliteration and translation.

The Old Babylonian Period

The beginning of this period should in theory start after the fall of the Ur III empire with the sack of Ur in 2004 BC. However, there is no clear transition point to the successor dynasty at Isin, which continued the Neo-Sumerian traditions.Footnote 1 According to some, the reign of Lipit-Ishtar (1934-24 BC) marks the end of the Ur III cultural hegemony which prevailed at Isin.Footnote 2

Marriage Contracts in Ancient Iraq

There is some debate about exactly when and on what grounds a marriage relationship could be said to be legally constituted. A formal marriage contract was needed before a man and a woman could be regarded as married according to the Code of Hammurabi, CH §128: šumma awīlum aššatam īḫuzma riksātīša lā iškun sinništum šī ul aššat “If a man has taken (a woman to be) a wife and has not drawn up a contract for her, that woman is not a wife.”Footnote 3 It has been argued by Greengus (Reference Greengus1969) that a written contract is not necessary, his argument hinging on the interpretation of the word riksātum and whether it denotes a written document. He argued that marriage was enacted by means of the verba solemnia used in adoption, manumission and divorce cases, and that the marriage documents regulated “transactions which could affect the status and rights of husbands and wives” rather than documenting the fact of the marriage itself.Footnote 4 Marriage was a legal union between a man and a woman with the aim of producing children and building a familyFootnote 5 and the forging of social and economic ties, which will secure tangible results for the future.Footnote 6 Marriage enabled the woman to secure her rights as a wife and mother and to function as an effective participant in building Society.Footnote 7

W. Durant postulated in his seminal work that societies without marriage are rare but that there is enough evidence to indicate a pre-historic transition from non-marrying societies to marrying ones as a result of the rising institution of property.Footnote 8 Similarly, the idea of the Kaufehe, whereby the woman was deemed to be bought as property by the man, was developed by Koschaker, but found to be inadequate to explain the complexities of Babylonian marriage relationships by Westbrook.Footnote 9 More recently, Démare-Lafont postulates that marriage starts as a contract then becomes an institution once children are born.Footnote 10 The bearing of offspring was indeed a cornerstone in a successful marriage and it may have been one of the most important factors leading to marriage.Footnote 11 The choice of a future wife was probably mostly carried out through intermediaries at the behest of a man's parents.Footnote 12 Ancient Iraqi laws stipulated that no marriage was legal without the consent of a woman's parents even if she lived in the man's house as his wife for a whole year.Footnote 13 Betrothal was conducted between the groom and a representative of the bride-to-be.Footnote 14

After the parties agreed to the union, the engagement was proclaimed and the future husband presented the engagement present termed níg-dé-a in Sumerian and biblu(m) in Akkadian to the woman's family.Footnote 15 This is indicated in an Old Babylonian letter as follows: lama Nabrû illakūnimma bibla ubbalūnim “they will bring the engagement present before they go to the festival of Nabru.”Footnote 16 However, the giving of a biblum was not obligatory.

Rituals for the engagement included anointing the woman's head with oil and perfume together with suitable gifts presented to the bride's family as part of the traditional rites when the engagement was officially declared in the presence of family, relatives and friends.Footnote 17 The groom then presented the bridewealth, or terḫatum, to her father.Footnote 18 This was usually in the form of silver. A relevant text from another Old Babylonian letter states: 5 gín kù.babbar terḫassa PN abūša maḫir “PN her father received her bridewealth, 5 shekels of silver.”Footnote 19 In other cases the bridewealth may be received by the woman's mother: 5 gín kù.babbar PN ummaša maḫrat “PN her mother received her bridewealth, 5 shekels of silver.”Footnote 20

The father of the bride gave her a present termed šeriktum which was her share, zittum, of her inheritance. CH §138: kaspam mala terḫatīša inaddiššim u šeriktam ša ištu bīt abīša ublam ušallamšima izzibši “He shall give her silver as much as the bridewealth, and restore to her the dowry that she brought from her father's house and he shall divorce her.”Footnote 21 A further gift was given to the bride by the groom termed a nudunnûm (CH §171): ḫīrtum šeriktaša u nudunnâm ša mussa iddinūšim ina ṭuppim išṭurūšim ileqqēma ina šubat mutīša uššab adi balṭat ikkal “the first-ranking wife shall take her dowry and the marriage settlement which her husband awarded to her in writing, and she shall continue to reside in her husband's dwelling; as long as she is alive she shall enjoy the use of it.”Footnote 22 Furthermore, we read in the Code of Hammurabi (CH §172): šumma šinništum šī ana waṣêm panīša ištakan nudunnâm ša mussa iddinūšim ana mārīša izzib “If this woman intends to leave (i.e. to marry again), she may bequeath to her children the nudunnûm which her husband gave her.”Footnote 23 The language of CH seems to be idiosyncratic here, as the nudunnûm could also be given by the father to his daughter as a dowry, as attested in the following marriage document: mimma nudunnâm ša PN1 ana mārtīša iddinūma ana bīt PN2 ušēribūši “all the nudunnûm presents which PN1 gave to his daughter when she was brought into the home of PN2.”Footnote 24 The nudunnûm is also involved in cases where a man marries the class of woman referred to as a šugītum: mimma annîm nudunnê ša fPN šu.gi “All of this is the marital property belonging to fPN the šugītum.”Footnote 25 The šugītum is usually mentioned as a second wife in relation to a nadītum who may not have children.Footnote 26 The šugītum did not have the same status as the nadītum.Footnote 27 However, there is no evidence that she could not be a wife in her own right.

An engagement could be called off for specific reasons, although this seems to be a complicated matter.Footnote 28 Such a case was addressed in CH §159: šumma awīlum ša ana bīt emīšu biblam ušābilu terḫatam iddinu ana sinništim šanītim uptallisma ana emīšu māratka ul aḫḫaz iqtabi abi mārtim mimma ša ibbablūšum itabbal “If a man who has the ceremonial marriage prestation brought to the house of his father-in-law, and who gives the bridewealth, should have his attention diverted to another woman and declares to his father-in-law ‘I will not marry your daughter’ the father of the daughter shall take full legal possession of whatever had been brought to him.”Footnote 29 However, if the father of the daughter calls the engagement off then he has to pay all gifts back to the groom twofold according to CH §160.Footnote 30

Although also a complicated situation, if the woman dies before the wedding, then the man may choose one of her sisters to take for a wife or have all of the gifts he has given restored to him. But if the groom dies before the wedding then his father has the right to take the woman as a wife for one of his other sons.Footnote 31 Polygamy took place if the first wife was childless; the second wife was often a slave but she did not have the same rights as the free wife.Footnote 32 The slave was a wife to the husband but a slave to the first and main wife. R. Westbrook in his work titled “The Female Slave” examines the complex situation of slave women taken into marriage.Footnote 33 They are treated as property but also subject to family laws.

The relationship between the first and second wife can be illustrated in the following text, CT 2.44, 17-25: u Iltani šēpī Tarām-Sagila imessi gišgu.za-ša ana É iliša inašši zēni Tarām-Sagila Iltani izenni salāmīša isallim kunukkīša ul ipette 1(bán) zíd še iṭênma uṭeḫḫīši “and Iltani shall wash the feet of Tarām-Sagila and carry her chair to the temple of her god (and) Iltani will side with Tarām-Sagila whether she is on bad or good terms (with their husband). She (Tarām-Sagila) will not open her sealings and will grind 1 bán of fine flour and present it to her.”Footnote 34 The above was one of a trilogy of contracts involving the same two women who were in a state of sisterhood.

Sometimes a man may have relations with more than one woman, each of whom may bear children. He may also marry a woman who already has children from a previous marriage. They will then adopt these children in addition to their own.Footnote 35 The woman had the right to re-marry if her husband became absent but she is not penalised if her husband returns. If she had children in the meantime, then each child will belong to their biological father.Footnote 36

Verb used in marriage contracts

The verb used is aḫāzum with the basic meaning of to take hold of something or someone according to CAD and AHw but the meaning “to marry” is secondary. This verb is not used on its own but within a full legal formula. The groom as subject is said to perform the following action with relation to the bride as object: ana aššūtim u mutūtim ahāzum.Footnote 37 The contractual phraseology involved denotes the transfer of control over a woman from her parents or guardians to a man for the purpose of placing her and the man in a status of lawful marriage.Footnote 38 The Sumerian term used is: nam-dam-šè … tuku meaning “take for wifeship and husbandship.”

Penalty Clauses

Most contracts have clauses detailing applicable penalties should either party not comply with their obligations. This mainly concerns the repudiation such as a wife telling her husband “you are not my husband.” The penalty can amount to being thrown in the river: tukum-bi dam-e dam-na ḫul-ba-an-da-gig-a-ni dam-ĝu10 nu-me-en ba-an-na-an-du11 i7-da-šè ba-an-sum-mu “If a wife hates her husband and says to him ‘you are not my husband’ they will throw her in the river.”Footnote 39 In some contracts, the wife's punishment is to be thrown from a tower, as in the case of another penalty from the trilogy of documents mentioned above: Tarām-Sagila u Iltani ana Warad-Šamaš mutīšina ul mutī atta iqabbīma ištu dimtim inaddûniššināti “Should Tarām-Sagila and Iltani say to Warad-Šamaš, their husband, ‘You are not my husband’ they shall throw them from a tower.”Footnote 40 Or she can have her head shaved then be sold as slave: “Should she (Tarām-Sagila) say to Iltani, her sister, ‘You are not my sister’ and to the children of her sister, ‘You are not my children,’ he (Warad-Šamaš) shall shave her head and sell her.”Footnote 41 Note: both of the above contracts involve the same persons but they contain different penalty clauses according to whether the repudiation of the family relationship was directed at the husband or one of the wives.

Date Formulae

The system of dating was based on giving years the name of a notable event that took place during that year. This included things such as the accession of a king to the throne, a military campaign, the building of a temple or walls and the digging of a canal. It was necessary to inform all the towns in any kingdom of the adopted year name to enable proper record keeping throughout the land.Footnote 42 Should there be no agreed notable event in that year then they resorted to using the previous year name by writing “the year after the previous year”. The formula for this is mu-ús-sa meaning the year following the previous year.Footnote 43 The date formula for tablet IM 201688 reads:

mu dèr-ra-i-mi-ti lugal 4 urudu ur-maḫ-gal-gal é-AN-nir-ra mu-na-dím

“The year when king Erra-imittī fashioned 4 large copper lions for him on the Ziggurat.”Footnote 44

This is a new and previously unattested year name for Erra-Imittī, the ninth king of the first dynasty of Isin who ruled from 1868-1861 BC. The published date formulae are:Footnote 45

1. Year Erra-imittī became king.

a. Year (Erra-imittī) established justice (in the land).

b. Year in which (Erra-imittī) restored Nippur to its right place.

c. Year after the year in which (Erra-imittī) restored Nippur to its right place.

da. Year in which (Erra-imittī) seized Kisurra.

db. Year Kisurra was destroyed.

ea. Year after the year Erra-imittī seized Kisurra (month kin-dInanna)

eb. Year the city wall of Kazallu was destroyed.

f. Year (Erra-imittī) built the city wall of ‘gan-x-Erra-imittī’

We suggest this new year name might be inserted as an additional name to precede year names “da” to “eb” above as it seems reasonable that the king would make an offering of copper lions on the Ziggurat in preparation for military action. This calls for a re-examination of the years of his reign which according to the Middle Chronology was from 1868-1861 BC.

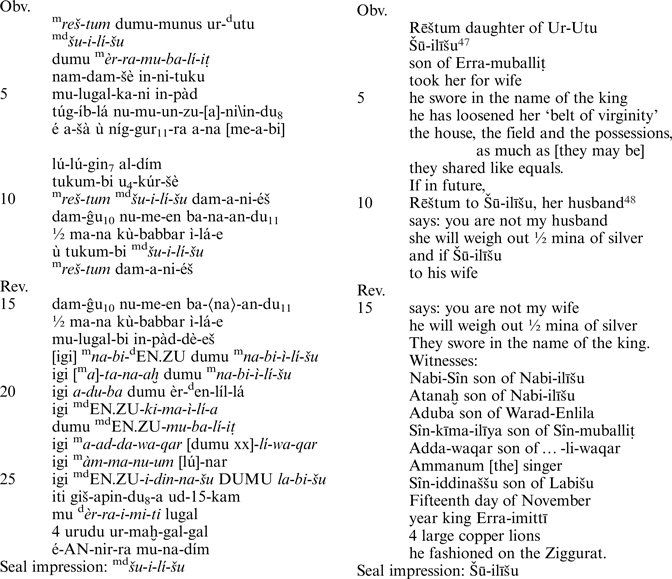

Tablet 1 Footnote 46

Fig. 1 Photographs and Hand-Copy of IM 201688 by Mohannad Kh. J. Al-Shamari.

Fig. 2 Side view of IM 201688.

Sumerian Legal Expressions

nam-dam-šè in-ni-tuku = ana aššūtim īḫuz meaning: “he took as wife.”Footnote 49

in-pàd = itma 3rd sg. G pret. of tamû meaning: “to swear.”Footnote 50

túg-íb-lá nu-mu-un-zu-[a]-ni literally “belt of unknowing.”Footnote 51 See TIM 4.48, 7 GIŠ.IGI.DÙ nu-mu-un-zu-na / in-du8 “he loosened the pin of her virginity,” as the content of the oath that the marriage has taken place, discussed by Landsberger (Reference Landsberger, Ankum, Feenstra and Leemans1968: 103–104), who also compared nam-mu-un-zu-a-ni at Ai 7 ii 20 (MSL 1, 96), although a parallel text is here vitiated by a transmission error, which has resulted in confusion with almanūtu “widowhood” (= nu-mu-su). The “pin” is also used in a related phrase at K4355+, obv. 19’-20’ in a description of ardat lilî (Landsberger Reference Landsberger, Ankum, Feenstra and Leemans1968: 44). The use of the “belt” rather than the “pin” is not attested elsewhere, but seems reasonable. See further Westbrook Reference Westbrook1988: 52.

níg-gàr-ra = makkūrum, “possessions,” for more regular níg-gur11-ra.Footnote 52

a-na me-a-bi = mala ibaššû, meaning: “as much as there may be.”Footnote 53

al-dím = 3rd sg. G pret. īpuš meaning: “he fashioned.”Footnote 54 The usage here with lú-lú-gin7 in the meaning of mitḫāriš is unparalleled.

u4-kúr-šè = ana warkat ūmim meaning: “in future.”Footnote 55

ba-na-an-du11 = iqtabi 3rd sg. G perf. meaning: “he said.”Footnote 56

ì-lá-e = išaqqal 3rd sg. G durative, meaning “he weighs, pays out.”Footnote 57

Tablet 2 Footnote 58

Fig. 3 Photos and Hand-Copy of IM 183636 by Mohannad Kh. J. Al-Shamari.

Fig. 4 Photo of Reverse right side of IM 183636.

Fig. 5 Photo of Lower Reverse of IM 183636.

Fig. 6 Photo of Reverse left side of IM 183636.

Sumerian Legal Expressions

munus-nita-dam = ḫīrtum meaning first wife or a wife of equal status to her husband. CAD gives the translation “wife of equal status” but also that of “first wife”. CAD quotes: šumma awīlum munus.nita.dam-šu īzib “If a man divorces his first wife.”Footnote 61

sag-gá-na meaning: “being at the disposal of someone,” Sumerian saĝ+an(i)+a, lit. “on her head.”

in-na-an-ku4 = ušērib 3rd sg. pret. Š form of the infinitive erēbum meaning: “to cause someone to enter.”Footnote 62

nam-ibila-šè = ana aplūtim meaning: “heirs.”Footnote 63

ḫé-íb-tuku = lirši “should he have, acquire” cf. VS 8.127, 9–12 (Sippar, OB): 10 ma-ri dbu-né-né-a-bi / ù hu-šu-tum li-ir-šu-ú-ma / mdutu-a-pí-li-ma / a-hu-šu-nu ra-bu-um, “Should Bunene-abī and Huššutum have ten sons, it is Šamaš-āpilī who is (still) their eldest brother.” An alternative translation “in future Sîn-abūšu will take 5 children” leaves more information to be supplied in order to explain the situation.

téš sè-ga-bi = mitḫāriš “equally.”Footnote 64

ì-ba-e = izuzzū 3rd pl. durative G form of zâzum meaning: “to divide up.”Footnote 65

ba-ra-e11-dè = ītelli Gt pres. of elûm, meaning “to forfeit,” usually expressed through Sumerian è.d cf. CAD E 125, but see also TMH 10 no. 6 for e11.

Summary Remarks on the Tablets

Of the two tablets it is text 2 which presents the more difficulties of understanding. Text 2 seems to illustrate the principle of CH §170, the legitimation of children born from a slave-woman by the father.Footnote 66 The first damaged 3 lines may have contained a number of PN's. The first wife, Ištar-rīšat, took a maid (whose name is lost) for her husband Sîn-abūšu together with Ikūn-pī-Ištar and Ištar-lamassī of slave status and they were attached to her as first wife. The husband will regard any future children as heirs to divide his estate equally between them, but will guarantee the heirship of Ikūn-pī-Ištar. If either party of the marriage denies the marriage, they lose the house, the field and all possessions and pay the other party 1/3 mina of silver. One of the witnesses is described as “a citizen of Isin,” although note that the sign SI was written incorrectly in line 33 on the reverse missing a second vertical wedge.

If we do not understand the verb in Tablet 2 obv. 13, ḫé-íb-tuku, as a precative being used in a conditional sense, it makes it more difficult to understand what is happening in the text. It would be necessary to posit that this contract was not the primary marriage contract between Sîn-abūšu and Ištar-rīšat. It would have to be second contract whereby Ištar-rīšat who probably could not have children provided her husband with a ready-made family of a slave with her 5 slave children to be adopted as heirs by the husband. It is also possible that the female slave given by Ištar-rīšat gave birth to 2 children who were counted by their father among his heirs. The 3 remaining children were maybe born to Ištar-rīšat, who, for some reason could no longer give birth. Alternatively, depending on the grammatical interpretation of the verb in obv. 13 in the manner of a conditional, a function also fulfilled by the Akkadian precative, the figure “five” is notional. It thus indicates any number of children that Sîn-abūšu might have (even as many as five), in comparison to whom the two children who are adopted as heirs in this document are to be treated equally when it comes to allocating inheritance. Problematic here, of course, is that five is not a particularly large number of children, which one might expect to be meant if the number was being used as an example of a potential that might not be fulfilled during Sîn-abūšu's life. However, this should not be seen as too great an obstacle to interpretation given the comparison with VS 8.127 mentioned above, where 10 children are mentioned as the notional figure.

Both tablets are from Isin. It is thus very interesting to note that both tablets give exactly equal treatment to the husband and wife in matters relating to the penalty imposed upon them in case either party decides to divorce the other. This is thus a very different arrangement in the city of Isin during the reign of Erra-Imittī to the one we saw above in CT 2.44, 6–11 (Sippar), where Tarām-Sagila and Iltani were having to pay with their lives or their freedom for terminating the relationship with Warad-Šamaš. Thus it seems that in ancient Iraq there were either different local customs for dealing with the legal consequences of marriage-relations, or there were different practices that were customary in different periods and circumstances. One cannot exclude, however, that the specific legal situation in each of the tablets resulted in the equality of the penalty. Indeed, the fact that the husband in Text 1 stipulates in obv. 6 that sexual intercourse has occurred is of great interest for the question of the criteria for considering that a marriage has taken place in the first place. Here the oath by the name of the king, the statement that the husband has deflowered a virgin woman, and the sharing of property all seem to belong to the conditions which validate the occurrence of marriage. It is, however, not clear that all these conditions needed to be satisfied in all cases of marriage.

Abbreviations

- Ai

Ana ittīšu = MSL 1

- BE

Babylonian Expedition of the University of Pennsylvania, Series A: Cuneiform Texts

- CAD

The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Pennsylvania

- CT

Cuneiform Texts from Babylonian Tablets in the British Museum.

- GAG

Grundriss der Akkadischen Grammatik = von Soden 1995.

- IM

Iraq Museum

- MSL

Materialien zum Sumerischen Lexikon

- TIM

Texts in the Iraq Museum

- TMH

Texte und Materialien der Frau Professor Hilprecht Collection

- UET

Ur Excavations, Texts

- YOS

Yale Oriental Series, Babylonian Texts.