The tablets and their archival context

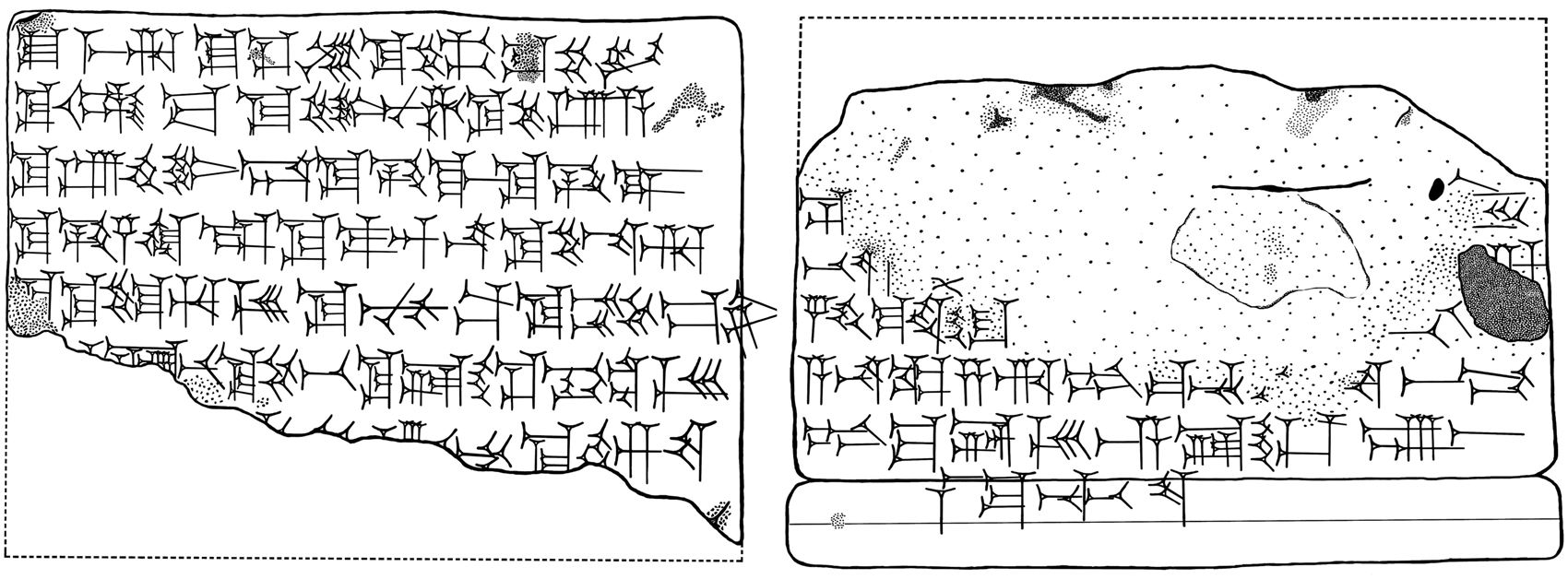

The two tablets presented in this paper are part of the British Museum's collections, accessioned under the museum numbers BM 30918 and BM 31071 (see figs. 1 and 4). Both tablets have a portrait format and are preserved in an excellent condition, with the exception of a few abrasions and cracks affecting mostly small areas of the surface near the edges, and in the corners.

Fig. 1 BM 30918 (British Museum), copy by K. Simkó.

Fig. 2 BM 66942 (British Museum), copy by K. Simkó

BM 30918, the larger of the two tablets, measures 7.6 centimetres in length and 5 centimetres in width. It contains two therapeutic prescriptions and a three-line-long scribal remark, with single horizontal rulings separating each text unit from the next. The other tablet, BM 31071, has smaller dimensions, measuring 4.6 centimetres in length and 2.3 centimetres in width. This tablet gives the description of a single therapy, followed by a colophon resembling the one on BM 30918. The two colophons are especially similar in that they both identify a certain Itti-Marduk-balāṭu as the owner of the tablets. Furthermore, both texts describe this person as a descendant of the Egibi family:

giṭṭi Itti-Marduk-balāṭu mār Egibi mašmašši Marduk-ēṭir išṭur

Long tablet of Itti-Marduk-balāṭu, descendant of Egibi, incantation priest. Marduk-ēṭir wrote it down.

Colophon 1

giṭṭi Itti-Marduk-balāṭu mār Egibi pālih Marduk [m]ādiš lišāqir

Long tablet of Itti-Marduk-balāṭu, descendant of Egibi. May the one who reveres Marduk value (this tablet) greatly.

Colophon 2

These colophons provide a possible link between the two tablets and the archive of the Egibi family. Equally important, the same archival context can be inferred from the acquisition history of the tablets. Registered as lot 645 and 798, respectively, both BM 30918 and BM 31071 entered the British Museum as part of the 76–11–17 collection, which George Smith acquired during his last journey to Baghdad in 1876. Originally, Smith bought 800 tablets from an antiques dealer named Michael Marini; and several weeks later he followed up with a second purchase of around 2,600 objects.Footnote 1 The exact provenance of the tablets is unknown, except that they were discovered by locals searching among the ruins of private houses somewhere in the vicinity of Babylon. The tablets were found in sealed jars, constituting an archive,Footnote 2 which has turned out to be the largest tablet collection from the Neo-Babylonian and early Achaemenid periods, recording the business activities of the Egibi family. Of the three to four thousand tablets that are said to have been found at the site after the first discovery of the sealed jars, 1,700 documents have been attributed with certainty to the archive of the Egibi family.Footnote 3 While Egibi tablets entered sporadically the collections of the British Museum as parts of various purchases, the bulk of the archive is still made up of the 76–11–17 collection, to which also the two medical tablets BM 30918 and BM 31071 belong.Footnote 4 Thus, even if the tablets do not provide concrete filiation, there seems to be some indirect evidence for the person mentioned in their colophons to be identified with Itti-Marduk-balāṭu, an important member and archive holder of the Egibi family.Footnote 5

Itti-Marduk-balāṭu of the Egibi family

As mentioned above, the archive of the Egibi family is the largest and most important private tablet collection from the Neo-Babylonian and early Achaemenid periods. It covers more than 100 years, with a sum total of around 1,700 identified documents, which record the business activities of five generations of family members.Footnote 6 The texts mainly reflect the activities of the eldest sons who took over the family business after their fathers’ death. Itti-Marduk-balāṭu was the chief actor of the third generation; he followed his father, Nabû-ahhē-iddin, who, in turn, took over from the head of the family of the first generation, Šulaja. While the administrative documents attest to several aspects of Itti-Marduk-balāṭu's business enterprise, his apparent occurrence in the colophon of the hitherto known two Egibi tablets with medical contentsFootnote 7 suggests that he may also have functioned in another capacity. In addition to being trained as a scribe, like his father, he probably became involved with cuneiform scholarship for a time, especially what constituted the craft of healing specialists.Footnote 8 In this respect, an important piece of information is provided by the colophon of BM 30918, portraying Itti-Marduk-balāṭu as an incantation priest (mašmaššu).

The reference to Itti-Marduk-balāṭu as an incantation priest in this medical context attests to the high esteem of this scholarly profession, which also granted a privileged status to the person with adequate training in the craft. More important than its social perception, such a designation also implied an educational background extending far beyond the conventional learning of a scribe; it meant specialised training and intimate knowledge of a set of traditional texts. Moreover, as the case of several Neo- and Late-Babylonian businessmen demonstrate, there were no sharp boundaries separating the field of business and entrepreneurship from someone's ability to become involved with temple activities in the capacity of an incantation priest. This is best illustrated by the examples of Bēl-rēmanni, Ninurta-ahhē-bulliṭ, and Iqîša, whose archives also contained a large amount of literature (e.g., therapeutic prescriptions, amulet stone lists, and ritual texts) reflecting their interests and specialised knowledge as incantation priests.Footnote 9

As for Itti-Marduk-balāṭu, there is no extensive literature that would reflect such a specialised interest or such a specific curricular context. However, an interesting piece of information is provided by a small sale document, which presumably portrays Itti-Marduk-balāṭu acquiring a writing board labelled gišDA (lē’u). As this administrative text seems to indicate, the purchased writing board represents a manuscript of the incantation series bīt rimki:

A writing board of the (incantation series) bīt rimki, which Iqīšaya, son of Būnnānu, descendant of Rab-banê, gave to Itti-Marduk-balāṭu, son of Nabû-ahhē-iddin, descendant of Egibi, for 2 kur of barley. Iqīšaya has been paid the (total of) 2 kur of barley from the hands of Itti-Marduk-balāṭu.

BM 30626 (Nbn. 289) 1–7Footnote 10

Alongside the two medical texts, this small administrative tablet also demonstrates Itti-Marduk-balāṭu's connection to the profession of incantation and healing specialists. In addition, there is indirect evidence that might indicate that Itti-Marduk-balāṭu received formal training as an incantation priest. One of the prescriptions in BM 30918 highlights his knowledge of the traditional therapeutic corpus, having been composed by reusing an earlier Neo-Assyrian version as its prototype. As will be argued, the recipe in question can be traced back to a Neo-Assyrian version known from two manuscripts, both of which belonged to the library of a family of incantation priests.Footnote 11 While the prescriptions are similar enough to be considered parallels,Footnote 12 BM 30918 seems to reflect an editorial process resulting in a new version of the prescription, which is considerably shorter than its Neo-Assyrian prototype, both in terms of the number of necessary drugs, as well as the instructions accompanying the drug list.

Itti-Marduk-balāṭu's apparent knowledge of the therapeutic corpus is an important link that ties him to the healing crafts. His name also appears to be associated with one of the core texts of incantation priests, featuring in the fragmentary colophon of a manuscript that represents the twelfth tablet of the medical-diagnostic series Sa-gig.Footnote 13 However, in the absence of filiation, it is difficult to decide, whether this Itti-Marduk-balāṭu, who must have been the scribe of this particular manuscript, is a namesake, or the actual member of the Egibi family. The matter is further complicated by the provenance of the tablet, since it does not come from the main Babylonian archive of the Egibis, but from Uruk, where the largest private archive in the late Neo-Babylonian and early Achaemenid periods belonged to a different branch of the Egibi family. It remains possible that the Sa-gig manuscript was transferred from Babylon to Uruk through a network connecting the archives of the two Egibi branches;Footnote 14 however, this assumption would also have to account for the discovery of the manuscript in the Eanna temple complex, with a larger collection of literary texts.Footnote 15 At the moment, it is not possible to establish a direct link between the Egibis and the Eanna temple complex, and therefore the question of authorship of the Sa-gig manuscript must remain open.

Even without the Sa-gig connection, there seems to be enough evidence to suggest that, at least for some time, Itti-Marduk-balāṭu of the Babylonian branch of the Egibi family was active as an incantation priest. In addition to purchasing scientific texts from the realm of these specialists, he is named as such in the colophon of the tablet BM 30918, which also attests to his knowledge of the traditional therapeutic corpus.

The prescriptions

Two prescriptions are recorded on BM 30918. There is no medical incipit in this text; nor is there any specific medical condition mentioned for which either of the two prescriptions might have been employed. In fact, the first prescription on the tablet highlights a long and quite unconventional procedure without making a single remark on the corresponding medical condition. Accordingly, a variety of healing substances were collected in amounts ranging from less than half a shekel to up to six shekels. The whole batch was crushed, sieved and consumed in small dosages weighing either a half or one shekel. No other information is given as to the preparation of the medicine, whereas a brief reference to liquids is made at the end, instructing the patient to drink beer or wine as the final step after the medicine has been taken.Footnote 16

The second text unit is congruent with the usual therapeutic prescriptions: a bandage is made to treat rather unspecific problems, such as stiffness, suppurations, fractures, and torn tendons affecting, most probably, the lower extremities.Footnote 17 The same prescription is also known from the unpublished Late Babylonian tablet BM 66942, which appears to be a complete duplicate, since it exhibits only small orthographic and grammatical differences, and a few additions and omissions of lesser importance. BM 66942 has a landscape format, and contains only this one prescription. The left edge of the tablet contains the illegible remnants of a three-line-long inscription, presumably a library filing notation. However, any attempt to read this inscription has been unsuccessful so far, and resulted only in some uncertain suggestions as to the reading of the passage.Footnote 18 Despite this lacuna in the text, so much is evident that the duplicate prescription ends on the reverse side of BM 66942, and it does not continue on its edge.

The prescription starts by listing 36 types of powder made of a great variety of healing substances. Cereals, legumes, different aromatics, and various trees, like cedar and cypress, are listed alongside more unconventional materials, including such rarely attested drugs as the powder of slag from a kiln or the powder of an old tree trunk. The drug list is followed by the summary section of the prescription and the description of the pertinent medical condition, enumerating a series of rather unspecific symptoms that probably affected the leg. Then, the text gives the necessary instructions with respect to the preparation of the medicine and its subsequent application: the different powders were kneaded either with old barley beer or with the juice of the plant called kasû, depending on the season the medicine was to be made. Finally, the paste or dough thus prepared had to be applied in the form of a bandage put, probably, on the legs.

As mentioned above, the second prescription in BM 30918 may have been composed by drawing on an earlier Neo-Assyrian version as its prototype. The Neo-Assyrian version is known from two manuscripts. Although they differ from one another in format, one being a single-column excerpt tablet (BAM 125), the other a compilation of recipes arranged in two columns (BAM 124), both manuscripts contain therapeutic material dealing with the diseases of the feet and legs. As already stated, the relevant passages in these two tablets run parallel enough to the corresponding part of BM 30918 and its duplicate, BM 66942. However, the Neo-Assyrian parallel also represents a considerably longer version of the prescription, so much so, that important remarks, such as the one about the outcome of the procedure, are missing from BM 30918.Footnote 19 Similarly, the instruction addressed to the healer to smear the dough with ghee (ina himēti tušalpat) is only attested in the Neo-Assyrian version. These omissions might attest to a kind of editorial process, which resulted in an abbreviated version of the prescription. The same process had an even greater impact on two other sections of the prescription, namely, the summary and the preceding drug list. The summary section of the late texts simply says “in total 36 (types of) flour”.Footnote 20 In comparison, the Neo-Assyrian tablets render the very same passage as “in total 46 (types of) flour, plants and aromatics, large (amount of) powder for a bandage (used both in) the medical and exorcistic lore”.Footnote 21

The apparent differences between the two versions of the drug list demonstrate the editorial process behind the abridged version of the prescription, as it is presented by the two Late Babylonian tablets BM 30918 and BM 66942. Table 1 outlines the structure of the two lists, pointing out that the overall composition of the drugs has not changed in these late texts. Several items have been removed from the late version of the prescription, but only one has been added without a corresponding Neo-Assyrian parallel. Although mostly plants and trees from the middle part of the list appear to have been deleted, it is yet to be determined exactly what principles played a role in the elimination process. At the same time, the relative order of drugs presents another difficulty, as it differs in the individual drug lists. In fact, compared to the earlier Neo-Assyrian version, more than half of the remaining content in the late texts seem to have been rearranged in one way or another. As indicated in Table 1, sometimes there is little deviation from one version to the other, as in the case of the ennēnu-barley, which is enumerated fifth in the Neo-Assyrian and sixth in the Late-Babylonian texts. On the other hand, there are examples of considerable divergencies, too, like the roasted sahlû-cress, which is seventeenth in the Neo-Assyrian and twenty-third in the Late Babylonian drug list. Consequently, any attempt at a more comprehensive understanding of the pertinent editorial process is hindered by the absence of any discernible patterns concerning both the selection of the drugs, as well as the ways in which they are represented in the individual drug lists. Even if these details must be left unexplained for the time being, the prescription in BM 30918 and BM 66942, along with the one that precedes it in the former tablet, has much to add to our knowledge of the Neo- and Late Babylonian therapeutic corpus (see below).

Table 1 Comparison of drug lists (the orthographic differences are in bold type)

Turning now to BM 31071, the only prescription presented by this small tablet has the same characteristics as the previously discussed text, including the complete absence of a medical incipit.Footnote 22 BM 31071 also starts with the drug list, and mentions rarely attested substances like the rather obscure tušru-plant. Then, the preparation of the medicine is described in an unusual detail. Accordingly, the drugs must be kept boiling in twelve litres of water until the volume of the mixture reduces to four litres; such a technical detail is otherwise rare in the more mainstream therapeutic corpus.Footnote 23 As the last step, pressed oil is to be poured over the mixture, after which a brief reference follows with the instruction to repeat the procedure.

BM 30918 and BM 31071: personalised therapies?

In recent years, a relatively large number of Neo- and Late Babylonian therapeutic tablets have been identified with very similar characteristic features. These tablets fall outside the scope of the more traditional or mainstream therapeutic corpus, exemplified by such compendia as the 45-tablet-long series from UrukFootnote 24 or the numbered extract tablets which usually collect material from several parts of standardised therapeutic texts.Footnote 25 The recently identified tablets seem to represent a separate category within the Neo- and Late Babylonian therapeutic corpus, displaying a series of formal and material features that have led researchers to consider them to be personalised therapies or the possible experiments conducted by innovative physicians within the confines of their own professional practices. As such, these prescriptions were not meant to be part of fixed and more conventional compendia.Footnote 26

Considering the formal characteristics first, all tablets in this category are relatively small. They are inscribed with one or only a few prescriptions, mostly in a landscape format, although the portrait format is by no means exceptional. The prescriptions are distinguished by a less common terminology, as they mention rare substances, and describe unusual healing practices, sometimes to the extent that interesting technical details hardly attested elsewhere in the corpus can be inferred from these texts. The regular use of detailed drug measurements is another typical trait.Footnote 27 Consequently, it is uncommon to find complete duplicates of these prescriptions, whereas distant parallels or variants do occur among the mainstream medical texts. In several cases, a brief colophon is also appended to the text, referring to the person who authored, owned or copied the tablet. As noted in this respect, “whenever a colophon of the type is crediting a physician with the authorship of the text, that person should be assumed to have had his floruit in or shortly prior to the time when the physical manuscript was produced”.Footnote 28

The two medical tablets BM 30918 and BM 31071 have very similar features in terms of format and content, which makes their attribution to the above-discussed category of therapeutic texts a highly reasonable assumption. They are of small dimensions and record only a few quite unusual medical procedures, while also using less common terminology. According to the tablets’ colophons, they may have belonged to the archive holder Itti-Marduk-balāṭu of the Babylonian branch of the Egibi family. Based on the accepted premise, it can be postulated that Itti-Marduk-balāṭu not only owned, but also authored these tablets.Footnote 29 He appears as an incantation priest in BM 30918 and, as illustrated by the above-discussed administrative tablet, he also seems to have collected incantation-related texts, which suggests him having some formal training in the craft of healing specialists.Footnote 30

As a person with such an educational background, Itti-Marduk-balāṭu must have been familiar with the more standardised therapeutic corpus, to the extent that he may even have used earlier prescriptions as prototypes for his medical experiments. According to the hypothesis presented above, the distant Neo-Assyrian parallels BAM 124 and BAM 125 might indicate such an editorial process that has resulted in an abridged version of an otherwise lengthy prescription. It is difficult to explain, on the other hand, how the apparent duplicate BM 66942 fits into this context, unless it is one of those pieces in the 82–9–18 collection which was purchased as coming from Babylon rather than Abu Habbah (Sippar).Footnote 31 In this case, it might be possible to argue, although not without a certain degree of speculation, that BM 66942 is a stray tablet from the archive of the Egibi familyFootnote 32 and that it represents another copy of the prescription otherwise known from BM 30918.

Conclusion

Recent research in Neo- and Late Babylonian medicine has already yielded some important preliminary findings regarding the ways in which therapeutic knowledge had been transmitted and reorganised after the end of the Neo-Assyrian era. Based on these new results, it was possible to argue that the two tablets BM 30918 and BM 31071 (and perhaps BM 66942) belong to a separate category of texts, containing what may be best described as personalised therapies or proof of experiments conducted by innovative physicians. It must be noted, however, that the study of the Neo- and Late Babylonian therapeutic corpus is in its early stages, and therefore the conclusions drawn in this paper must remain provisional. Facilitated by the systematic edition of the great number of unpublished tablets, a deeper understanding of therapy as it was exercised in these late periods could eventually lead to the revision of our hypotheses.

Text editionFootnote 33

Before proceeding with the edition of BM 30918 and BM 31071, it is worth taking a look at the orthographic and linguistic peculiarities of the texts, since they are typical of the Neo- and Late Babylonian medical corpus. In this respect, it is noticeable that case endings are used irregularly: drug names are mostly written in the nominative case, while sometimes the accusative case (e.g., úkur-ka-nam and úbiš-šá; BM 30918 obv. 2 and 5) or the genitive case (e.g., giššur-mi-ni; BM 31071 obv. 7) is used instead. Similarly, in a construct chain or with prepositions, where the genitive is expected, the case ending is nominative (e.g., ZÌ šesa-hi-in-du and ana ke-ši-ru; BM 30918 obv. 20 and rev. 32); the loss of the final case-marking vowel is also attested (e.g., úkam-kád; BM 30918 obv. 10). Another characteristic feature of these medical texts is the presence of unconventional orthography, such as MUN sal-lim instead of MUN eme-sal-lim (BM 31071 obv. 5), and qà-lap instead of qí-líp (BM 30918 obv. 10–11). Moreover, healing plants not known from the Neo-Assyrian therapeutic corpus also occur in these texts (e.g., the plants called zūpu and biššu; BM 30918 obv. 5).

A typical feature of the Neo- and Late Babylonian therapeutic texts is the use of exact drug measurements. In BM 30918 and BM 31071 the sequence of half, one, and two shekels were used, but the subdivision of the shekel into smaller units, such as 1/4 shekel (rebūtu), is also attested.

Text 1

Museum No. BM 30918Footnote 34

Accession No. 1876–11–17, 645

Measurements 7.6 × 5 cm

Provenance Babylon

Date 550-500 b.c.e.

Obverse

1. 1/2 GÍN útar-muš 1/2 GÍN úIGI-lim 4-ut ú⸢IGI.NIŠ⸣

2. 1 GÍN úkur-ka-nam šá KUR 1 GÍN úSI.SÁ

3. 1 GÍN úha-šá-nu 1 GÍN úšu-un-hu

4. 1 GÍN úbu-uṭ-na-nu 5 ⸢GÍN⸣ úqul-qul-la-nu

5. 5 GÍN úzu-pu 5 GÍN ú⸢biš⸣-šá

6. 5 GÍN úúr-né-e 5 GÍN ⸢úha⸣-še-e

7. ⸢5⸣ GÍN úKUR.RA 2 GÍN úGAMUNsar.GE6

8. ⸢2⸣ GÍN úGAMUNsar 2 GÍN úNU.LUH.HA

9. 2 GÍN úDÚR.NU.LUH.HA 2 GÍN ⸢NUMUN?⸣ x x

10. ⸢2⸣ GÍN úkam-kád 2 GÍN qà-lap x [x]

11. ⸢2⸣ GÍN qà-lap SUMsar 2 GÍN úx [x x]

12. 2 ⸢GÍN⸣ NUMUN úHUR.SAG šá KUR-i 2 GÍN ⸢NUMUN GAZI⸣sar

13. ⸢2⸣ GÍN na4gab-bu-ú 4-ut MUN KU.PAD

14. 2 ⸢GÍN⸣ MUN a-ma-nim 2 GÍN MUN <eme>-sal-lim

15. 6 GÍN ILLU NU.LUH.HA 2 NINDA ṭì-iṭ-ṭa !?

16. GAZ SIM 1/2 GÍN ⸢lu⸣-ú 1 GÍN a-na KA-šú

17. ŠUB.ŠUB-di KAŠ lu-ú GEŠTIN EGIR.MEŠ-šú NAG.MEŠ

18. ZÌ šib-ri ZÌ MUNU5 ZÌ ŠE.EŠTUB ZÌ ŠE.MUŠ5

19. ZÌ GIG.BA ZÌ šeIN.NU.HA ZÌ ŠE.SA.⸢A⸣

20. ⸢ZÌ šesa⸣-hi-in-du ZÌ GÚ.GAL ⸢ZÌ⸣ G[Ú.TUR]

Reverse

21. ⸢ZÌ⸣ GÚ.NÍG.ÀR.RA ZÌ ZÍZ.A.AN ZÌ ⸢pu⸣-[ud-ri]

22. ZÌ ŠE10 TUmušen.MEŠ ZÌ NUMUN GADA ZÌ DUH.ŠE.G[IŠ.Ì]

23. ⸢ZÌ⸣ GIS.ÙR SUMUN ZÌ ŠE.BAR SUMUN ZÌ ⸢GAZI⸣sar ⸢BÍL⸣

24. ZÌ ŠIKA NINDU SUMUN ZÌ ha-he !(še)-e šá UDUN ZÌ IM.BABBAR

25. ZÌ sah-lé-e BÍL-tú ZÌ gišEREN ZÌ ŠUR.MÌN

26. ⸢ZÌ⸣ gišdup-ra-nu ZÌ ⸢šim⸣GÚR.GÚR ZÌ šimLI

27. ⸢ZÌ šim⸣GAM.MA ZÌ ⸢šim⸣MAN.DU ZÌ šimŠEŠ

28. ZÌ šimGIG ZÌ šimGÍR ZÌ ŠIM.ŠAL

29. ZÌ šimMUG ZÌ GI DU10.GA PAP 36 ZÌ.MEŠ

30. ri-di a-na pu-uš-⸢šu⸣-hi šag-ga a-na

31. lu-ub-bu-ku sah-ri a-na ⸢su⸣-up-pu-hu

32. LUGUD a-na pa-ta-hu še-bir-tú ana ke-ši-ru

33. šá-hi-it-tú a-na tur-ru SA bat-qa a-na

34. ka-ṣa-ru šum4-ma EN.TE.NA ina KAŠ ŠE.BAR SUMUN

35. šum 4-ma AMA.MEŠ ina A GAZIsar SILA11-aš LÁ-id

36. imGÍD.DA mit-ti-d⸢ASAL⸣.LÚ.HI-ba-lá-ṭù

37. DUMU mE.GI7.BA.TI.LA lúMAŠ.MAŠ

38. ⸢m.d⸣ASAL.LÚ.HI-KAR-ir IN.SAR

Notes

2. kurkanû ša šadî: The plant called “mountain kurkanû” is rare in medical texts; the CAD lists only four attestations in the therapeutic corpus, to which another attestation was added from the pharmacological text Uruanna.Footnote 35 The plant name is spelled syllabically in the commentary text BRM 4 32, which also makes a distinction between two varieties, respectively labelled as coming “from the mountain” (ša šadî) and “from the land” (ša māti);Footnote 36 the difference between the wild and indigenous variety of the kurkanû-plant must have been meant this way.Footnote 37 While in BAM 92 iii 5–6 kurkanû was applied on its own in the form of a potion, BAM 311 obv. 17’ mentions it alongside cedar and mūṣu-stone as part of a phylactery. Moreover, kurkanû also served in BAM 7 38 i 17’–18’ together with several other plants as ingredient for fumigation.

3. šunhu: The healing plant šunhu (with its alternative spelling šun'u) is defined by the CAD as “a bulbous plant”. In therapeutic prescriptions this plant occurs frequently together with another “bulbous plant”, andahšu, which could be attributed to the alliteration of the consonants /š/ and /h/ in both words. The šunhu-plant was used mostly in potions for lung problems and kidney diseases.

5. zūpu, biššu: With respect to the two plants called zūpu and biššu, no other attestations could be found in any other therapeutic text. However, spelled biš-šú sar and zu-ú-pu sar, respectively, the same plant names are attested next to each other in the Late Babylonian tablet BM 46226, which is a list of plants that could be found in the royal garden of Marduk-appla-iddina.Footnote 38 The plant biššu is also mentioned in the broken tablet 83–1–18, 727 from Nineveh (bi-ši): although the passage is in a fragmentary condition, so much can be determined with confidence that biššu serves there as the equivalent of a now illegible term. Interestingly, the text was written in Babylonian script, without one of determinatives Ú or SAR being assigned to the name of the plant.Footnote 39

9–11. Due to the fragmentary condition of the passage, the words at the end of these lines remain obscure. Based on the available space, there appears to be two to three signs in each of these lines.

10–11. qalap, kamkad: The form qalap is interpreted here as an unusual spelling for the well-known term qilpu “rind, skin”; by the same token, kamkad may probably stand for the plant called kamkadu. Note, however, that no other example of either of these irregular forms is known to us.

14. ṭābat emesallim: The form MUN sal-lim, used instead of the more regular MUN eme-sal-lim, can also be found in BM 42272 obv. 6.Footnote 40 Other unusual spellings of this word are MUN me 5-sal-lim (BAM 18: 3Footnote 41 and BAM 548 i 12Footnote 42) and MUN mé-sil (BM 32277+ i 21). Note, furthermore, that in the commentary text BRM 4 32, the emesallu salt is explained as “salt from the river” (MUN eme-sal-lim : MUN šá lìb-bi ÍD).Footnote 43

15. ṭiṭṭu (!?): The reading ṭì-iṭ-ṭa !? for “clay” is hypothetical. Alternatively, the term could be understood as an incorrect rendering of tittu “fig”. It should be noted that clay, especially canal clay, occurs as a magical ingredient in the medical rituals against ummu kayyamānu “permanent fever”,Footnote 44 and that clay from both banks of a river was used in making an amulet against another feverish condition called “seizure of the mountain”.Footnote 45

21. pudru: The “dung cake” pudru occurs together with other types of dung (e.g., gazelle and dove) in medical texts,Footnote 46 and it can be connected especially to the dung of oxen with the help of a lexical passage.Footnote 47 The drug was used in namburbi rituals, as well as in Old-Babylonian rituals as an ingredient of a poultice for broken legs and dog-bite.Footnote 48

24. qēm hahê ša utūni: The ingredient called “slag powder from a kiln” is used as a drug in various therapeutic prescriptions.Footnote 49 It can be suggested that, similarly to the drug “sherd from an old oven”, the healing effects of these drugs were based on the magico-medical characteristics of the oven used to heat or macerate the remedies.Footnote 50

30. rīdi ana puššuhi: The translation “for undoing the expected action (of the illness)” is based on a somewhat specific meaning of the word rīdu, as it can be gathered from a short series describing the magico-medical properties of cylinder seals with respect to the raw materials of which they are made. Here, it is said that by wearing a carnelian seal, “common sense (or proper attitude) will not be released from the man's body”.Footnote 51 The meaning “proper attitude” or, in transferred meaning, “expected action” of an illness might also be meant in Ludlul III 86–87, where this word is connected to breathing problems and fever. For this passage, the following translation is suggested: “My nose whose breathing has become blocked due to the expected action of fever (ina rīdi ummi) – He soothed its affliction and now I breathe [freely]”.Footnote 52 Thus, in this context, rīdu may probably refer to the expected action or proper attitude of fever, that is, to make breathing difficult by attacking the respiratory system.Footnote 53

37. Egibi: For a collection of the various forms in which the name Egibi can be rendered, see Spar and von Dassow Reference Spar and von Dassow2000: LXXIII; Wunsch Reference Wunsch2000a: 290. For the writing mE.GI7.BA.TI.LA see especially Lambert Reference Lambert1957: 4; Wunsch Reference Wunsch2000a: 2 n. 5.

Text 1a

Museum No. BM 66942Footnote 54

Accession No. 1882–09–18, 6935

Measurements 2.86 × 5.08 cm

Provenance Sippar or Babylon

Date Late Babylonian

Obverse

1. ZÌ šib-ri ZÌ LAGAB MUNU5 ZÌ ŠE.EŠTUB ⸢ZÌ⸣ ŠE.MUŠ5

⇒ ZÌ šib-ri ZÌ 0 MUNU5 ZÌ ŠE.EŠTUB ZÌ ŠE.MUŠ5

2. ZÌ GIG.BA ZÌ šeIN.NU.HA ZÌ ŠE.SA.A

⇒ ZÌ GIG.BA ZÌ šeIN.NU.HA ZÌ ŠE.SA.⸢A⸣

3. ZÌ sa-hi-in-du ZÌ GÚ.GAL ZÌ GÚ.TUR

⇒ ⸢ZÌ šesa⸣-hi-in-du ZÌ GÚ.GAL ⸢ZÌ⸣ G[Ú.TUR]

4. ZÌ GÚ.NÍG.ÀR.RA ZÌ ZÍZ.AN.NA ZÌ pu-ud-ri

⇒ ⸢ZÌ⸣ GÚ.NÍG.ÀR.RA ZÌ ZÍZ.A.AN ZÌ ⸢pu⸣-[ud-ri]

5. ⸢ZÌ⸣ ŠE10 TUmušen.MEŠ ZÌ NUMUN GADA ZÌ DUH.ŠE.GIŠ.Ì

⇒ ZÌ ŠE10 TUmušen.MEŠ ZÌ NUMUN GADA ZÌ DUH.ŠE.G[IŠ.Ì]

6. [ZÌ GI]Š.⸢ÙR⸣ SUMUN ZÌ ŠE 0 SUMUN ZÌ GAZIsar BÍL.MEŠ

⇒ ⸢ZÌ⸣ GIS.ÙR SUMUN ZÌ ŠE.BAR SUMUN ZÌ ⸢GAZI⸣sar ⸢BÍL⸣ 0

7. […………………………………] ⸢ha-he-e šá UDUN ZÌ IM⸣.BABBAR

⇒ ZÌ ŠIKA NINDU SUMUN ZÌ ha-he !(še)-e šá UDUN ZÌ IM.BABBAR

8. […………………………………… ŠUR.MÌ]N?

⇒ ZÌ sah-lé-e BÍL-tú ZÌ gišEREN ZÌ ŠUR.MÌN

Reverse

(circa four lines missing)

13′. ša[g-ga ………………………………… su-up-p]u ?-hi ?

⇒ šag-ga a-na / lu-ub-bu-ku sah-ri a-na ⸢su⸣-up-pu-hu

14′. LUGUD ⸢a⸣-[na ……………………… ke-ši]-⸢ri⸣

⇒ LUGUD a-na pa-ta-hu še-bir-tú ana ke-ši-ru

15′. šá-hi-it-⸢tu⸣ [………………ba]t ?-q[a ?]

⇒ šá-hi-it-tú a-na tur-ru SA bat-qa

16′. a-na ka-ṣa-ri šum-⸢ma EN⸣.T[E.N]A ina KAŠ 0 0

⇒ a-na / ka-ṣa-ru šum 4-ma EN.TE.NA ina KAŠ ŠE.BAR SUMUN

17′. šum-ma AMA.MEŠ ina A GAZIsar SILA11-aš

⇒ šum 4-ma AMA.MEŠ ina A GAZIsar SILA11-aš

18′. LÁ-ma TI-uṭ

⇒ LÁ-id 0

Left edge

1. [………………..] gišNU.ÚR.MA

2. [………………..] x x x sa da nu?

3. [………………..] x ú? x di nu

Fig. 3 BM 66942, inscription on the left edge (© The Trustes of the British Museum).

Text 1b

Publication No. BAM 124 (A)

BAM 125 (B)

Provenance Assur (N4)

Date Neo-Assyrian

Aiii44 ZÌ šib-ri ZÌ LAGAB MUNU6 ZÌ ⸢LAGAB?⸣ ŠE.EŠTUB ZÌ ŠE.MUŠ5 ZÌ šeNU.HA

B1-2 [………] ZÌ LAGAB MUNU6 ⸢ZÌ⸣ [………………………] / [………….] ZÌ še[NU.HA]

Aiii45 ZÌ GIG ZÌ GÚ.GAL ZÌ GÚ.[TUR ZÌ G]Ú.NÍG.ÀR.RA ZÌ ŠE.SA.A

B2-4 [………] / [……………] ZÌ GÚ.[TUR ………………………] / [ZÌ Š]E.SA.A

Aiii 46 ZÌ šesa-hi-⸢in-di⸣ ZÌ ZÍZ.A.AN ⸢ZÌ⸣ pu-ud-ri ZÌ ŠE10 TUmušen

B4-5 ZÌ šesa-hi-i[n-di ………………] / [ZÌ] pu-ud-ri ZÌ ŠE10 TUmušen

Aiii 47 ZÌ NUMUN GADA ZÌ GAZIsar BÍL.MEŠ Z[Ì ZÀ.HI].LI BÍL-te ZÌ IM.BABAR

B5-7 […………………….] / [ZÌ] GAZIsar BÍL.MEŠ ZÌ Z[À?.HI.LI ………] / [ZÌ] IM.BABBAR

Aiii 48 ZÌ DUH.ŠE.GIŠ.Ì HÁD.DU-ti ZÌ GIŠ.[ÙR SUMUN Z]Ì GI gi-sal BÀD SUMUN

B7-8 ZÌ DUH.ŠE.GIŠ.Ì […………..] / [Z]Ì ÙR SUMUN ZÌ GI gi-sal BÀD SUMUN

Aiii 49 ZÌ ŠIKA IM.ŠU.RIN.NA SUMUN ZÌ M[UNU6 ZÌ] ha-he-e šá UDUN

B9-10 [ZÌ] ŠIKA IM.ŠU.RIN.NA SUMUN / [ZÌ] MUNU6 ZÌ ha-he-e šá UDUN

Aiii 50 ZÌ di-ik-me-ni šá dugUTUL7 ZÌ úṣa-⸢da⸣-[ni ZÌ gi]šsi-hi ZÌ ar-ga-ni

B11-13 [ZÌ] di-ik-me-en-ni šá dugUTUL7 / [ZÌ] úṣa-da-ni ZÌ gišsi-i-hi / [Z]Ì gišar-gá-ni

Aiii 51 ZÌ gišLUM.HA ZÌ úáp-ru-še úak-tam ZÌ ⸢A⸣.[GAR.GAR MAŠ.DÀ] ZÌ úṣa-ṣu-un-[te]

B13-15 ZÌ gišLUM.HA / [Z]Ì úáp-ru-še ZÌ úak-tam / [Z]Ì A.GAR.GAR MAŠ.DÀ ZÌ úṣa-ṣu-um-te

Aiii 52 ZÌ gišEREN ZÌ gišŠUR.MÌN ZÌ gišdup-ra-ni ZÌ š[im]GÚR.GÚR ZÌ šim⸢LI⸣

B16-18 [Z]Ì gišEREN ZÌ gišŠUR.MÌN / [Z]Ì gišdup-ra-ni ZÌ šimGÚR.GÚR / [ZÌ] ⸢šim⸣LI

Aiii 53 [Z]Ì šimGAM.MA ZÌ šimŠEŠ ZÌ šimGÍR ZÌ ŠIM.[SAL? ZÌ šim MUG? ZÌ ši]mGIG

B18-20 ZÌ šimGAM.MA / [ZÌ ši]mŠEŠ ZÌ šimGÍR / [ZÌ ŠIM.SAL? ZÌšimMUG?] ZÌ šimGIG

Aiii 54 [ZÌ] GI DU10.GA ZÌ gišMAN.DU PAP 46 ZÌ.DA.MEŠ [Ú.H]I?.A

B21-22 [ZÌ GI DU10.GA] ZÌ úMAN.DU / [PAP 46 Z]Ì.DA.ME[Š Ú.H]I?.⸢A⸣

B

Aiii 55 [u ŠI]M?.HI.A si-ku GAL-ú na-aṣ-[ma]-⸢ti⸣ A.⸢ZU-ti⸣

B22-23 u ŠIM.HI.A / […….] GAL-[ú ………………] MAŠ.MAŠ-ti A.ZU-ti

Aiii 56 [ri-di] ⸢ana⸣ šup-šu-hi áš-ṭa ana lu-ub-bu-ki sah-ra ⸢ana⸣ [nu ?-uh ?-hi]

B24-26 [ri-d]i ? a-na šup-šu-hi / [áš-ṭ]a ? a-na lu-ub-bu-ki / [sah-r]a a-na [nu ?-uh ?]-hi

Aiii 57 [LUGUD ana p]a-ta-hi še-bir-⸢te ana ke-še-ri⸣ šá-hi-it-⸢te ana⸣ [tur-ri]

B27-29 [………..] a-na pa-ta-hi / [………] a-na ke-še-ri / [………....] a-na t[ur]-ri

Aiii 58 [SAbat-q]a ⸢a⸣-[na ka]-ṣa-ri šum 4-ma EN.TE.NA ina KAŠ.[SAG]

B30-31 [……………] a-na ka-ṣa-ri / [………………………………] ina KAŠ.SAG

Aiii 59 [……………………………………. SILA11-a]š Ì.NUN TAG.TAG LÁL-id-m[a TI-uṭ]

B32-33 [………………….] ⸢A GAZI⸣sar SILA11-aš / [………] TAG.TAG [LÁL]-id-ma TI-uṭ

Text 2

Museum No. BM 31071Footnote 55

Accession No. 1876–11–17, 798

Measurements 4.6 × 2.3 cm

Provenance Babylon

Date 550-500 b.c.e.

Fig. 4 BM 31071 (British Museum), copy by A. Bácskay.

Obverse

1. 1 NINDA úA.ZAL.LÁ

2. 1/2 GÍN KA A.AB.BA

3. 4-ut úLAL

4. 1/2 GÍN útuš-rú

5. 1/2 GÍN MUN <eme>-sal-lim

6. 1 1/2 GÍN úha-šá-nu

7. 1 GÍN giššur-i-ni

8. 1/2 GÍN úKUR.KUR

9. 1/2 NINDA NAGA.SI

10. 1 GÍN gišEREN.SUMUN

11. 1/2 GÍN útar-muš

12. 1 GÍN Ú dUTU

Reverse

13. ⸢3⸣ NINDA šimLI

14. 1 GÍN GI DU10.GA

15. 1 (BÁN) 2 SÌLA A a-di

16. ana 4 SÌLA GUR ŠEG6-šal

17. Ì.GIŠ hal-ṣa a-na

18. IGI ŠUB 2-šú DÙ-su

19. imGÍD.DA

20. mKI-dAMAR.UTU-ba-la-ṭu

21. A me-gi-bi

22. pa-li-ih d⸢AMAR.UTU⸣

23. ⸢m⸣a-diš li-šá-qir

Notes

4. tušru: The tušru-plant is rarely mentioned in therapeutic texts, whereas in Uruana I 459 and in the medical commentary 11N–T4: 19 it is equated with another type of plant called ḫallappānu and ḫaltappānu.Footnote 56

5. ṭābat emesallim: See the notes to Text 1 l. 14.

15–16. Reducing the volume of liquids by boiling before their application must have been a usual praxis in Babylonian medicine. Probably the more concentrated liquids could be used in the form of ointments or lotions.Footnote 57 This method was understood by Finkel as a possible characteristic feature of asûtu in Late-Babylonian medicine.Footnote 58

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the valuable comments offered by the reviewer of our paper, JoAnn Scurlock. We are also indebted to Cornelia Wunsch, Mark Geller, Michael Jursa and Henry Stadhouders for their remarks on a draft version of this paper, as well as to Lee Beaudoen and Gabriella Juhász for their help in improving its English. Needless to say, we solely bear responsibility for any remaining errors and imperfections.