Introduction

Recent archaeological investigations conducted by a number of survey projects in the core of the Assyrian Empire – covering part of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (Fig. 1) – have collected extensive evidence that during the Neo-Assyrian period, the ‘Assyrian Triangle’ became the arena of a pervasive top-down planned intervention of landscape engineering imposed by the Assyrian rulers and imperial elites, which profoundly transformed the Assyrian ruralscape (Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi, MacGinnis, Wicke and Greenfield2016, 2018a‒b; Ur Reference Ur and Frahm2017; Ur and Osborne Reference Ur, Osborne, MacGinnis, Wicke and Greenfield2016; Ur et al. Reference Ur, Babakr, Palermo, Creamer and Soroush2021). New policies of settlement intensification were implemented throughout the Assyrian core and Northern Mesopotamia through the progressive infilling of the landscape with scattered small towns, villages, and farmsteads. These settlements extended agriculture into previously uncultivated areas, thus introducing an agricultural strategy based on the expansion of rural production (Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi1996, Reference Bonacossi and Bunnens2000, 2018a: 63; Ur Reference Ur2010: 162‒163, 2017: 22; Ur and Osborne Reference Ur, Osborne, MacGinnis, Wicke and Greenfield2016: 168–171; Wilkinson and Tucker Reference Wilkinson and Tucker1995: 145‒147; Wilkinson et al. Reference Wilkinson, Wilkinson Barbanes, Ur and Altaweel2005: 40‒41). At the same time, the construction of grandiose regional irrigation canals, first launched during the Middle Assyrian period in the Ashur and Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta hinterlands and probably also in the Lower Khabur Valley (Bagg Reference Bagg2000; Kühne Reference Kühne and Kühne2018), became a systematic strategy of infrastructure creation pursued by many Neo-Assyrian kings in the ninth–seventh centuries B.C. (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Northern Iraq and the Kurdistan Region, with the Land of Nineveh Archaeological Project region and major Assyrian sites indicated (by Alberto Savioli).

Fig. 2. Main water systems in the Assyrian homeland (by Alberto Savioli, based on LoNAP data, Safar Reference Safar1946, Oates Reference Oates1968, Ergenzinger and Kühne Reference Ergenzinger, Kühne and Kühne1991, Dittmann Reference Dittmann, Finkbeiner, Dittmann and Hauptmann1995 and Ur et al. Reference Ur, de Jong, Giraud, Osborne and MacGinnis2013).

In past scholarship, emphasis has been placed on the ideological dimension of Assyrian canal building; hydraulic systems were understood essentially as a means to secure water supplies for the royal parks and gardens of Assyrian capital cities and to water the fields in their immediate surroundings (Oates Reference Oates1968: 47–52; Reade Reference Reade1978: 174). Their role as infrastructure providing the urban centres and their rural surrounds with water for irrigation and intensified agricultural production has often been rejected (Reade Reference Reade1978: 174) or downplayed (Masetti-Rouault 2018: 34 and n. 58; Oates Reference Oates1968: 47–49, 52; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2003: 130). However, fresh archaeological research in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq has now made it clear that Assyrian hydraulic networks, which ranged from the countryside around Ashur and Arbail between the Upper and Lower Zab rivers and the Neo-Assyrian capital cities and provincial centres in the northern part of the ‘Assyrian Triangle’ to the Khabur and Middle Euphrates valleys,Footnote 1 were primarily economic infrastructures with transformative effects on the landscape and staple food production. New evidence for this important and often neglected aspect comes from the excavation of the Faida canal and its rock reliefs in the Duhok Region of Kurdistan, carried out since 2019 by the Kurdish-Italian Faida Archaeological Project jointly conducted by the University of Udine and the Duhok Directorate of Antiquities.

Irrigation, staple-crop economy, and landscape commemoration: The Northern Assyrian Irrigation System

The health of the Assyrian Empire's economy depended greatly on the success of the harvest (Postgate 1979), and repeated droughts would have inflicted considerable damage on the growing imperial economy.Footnote 2 Especially during the eighth and seventh centuries B.C., the Assyrian core region underwent a population explosion, largely due to the massive forced resettlement by the Assyrian kings of conquered peoples within the ‘Assyrian Triangle’, as described in particular by royal inscriptions (Oded Reference Oded1979: 28), plus the establishment of new capital cities at Khorsabad and then Nineveh. Settlement patterns across the imperial core were dominated by dense scatters of small villages, which may archaeologically mirror the deliberate colonisation of the Assyrian countryside through forced resettlement of deportees (Morandi Bonacossi 2018a‒b; Ur Reference Ur and Frahm2017; Ur and Osborne Reference Ur, Osborne, MacGinnis, Wicke and Greenfield2016). Assyrian deportations in the southern Levant are convincingly documented by local written records (Na'aman Reference Na'aman, MacGinnis, Wicke and Greenfield2016; Na'aman and Zadok Reference Na'aman and Zadok2000) and evidence for decreased occupation and abandonment recorded in settlement patterns (Na'aman Reference Na'aman1993). Population growth and episodes of climatic variability – including at least one harsh drought event mentioned by a mid-seventh century B.C. sourceFootnote 3 and recently documented for the same century by isotope analysis of speleothems from the Kuna Ba cave in the Sulaymaniyah mountains of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (Sinha et al. Reference Sinha, Kathayat, Weiss, Li, Cheng, Reuter, Schneider, Berkelhammer, Adalı, Stott and Edward2019)Footnote 4 – may have been important causes of weakness and instability in the Assyrian economic and political systems. To curb the risk due to climatic and environmental factors and to expand agricultural productivity notwithstanding the vagaries of rainfall, the Assyrian rulers built massive and highly sophisticated hydraulic engineering networks. The creation of new waterscapes transformed the rural landscape of Assyria, creating a shift from extensive dry farming (the low productivity of which was compensated by the large swathes of land brought under cultivation in the rolling plains of Assyria) to an intensive, predictable and high-yield cultivation system based on irrigation, which allowed the Assyrian staple-crop economy to be protected from harvest failures determined by unusually low rainfall.Footnote 5

The Governorates of Duhok and Ninawa in Iraq host the uniquely highly branched and most monumental irrigation system ever built by the Assyrians in the core of their empire. Between 703 and c. 688 B.C., Sennacherib created a ramified network of canals in four stages (Fig. 3) to water Nineveh's extensive hinterland and to bring water to his ‘Palace without a Rival’ (Russell Reference Russell1991) and royal parks on the citadel of Nineveh (Bagg Reference Bagg2000).Footnote 6

Fig. 3. The Northern Assyrian Irrigation System (by Alberto Savioli).

Until a few years ago, the Northern Assyrian Irrigation System and the other hydraulic networks in the imperial coreFootnote 7 had been explored only anecdotally (Oates Reference Oates1968; Reade Reference Reade1978, Reference Reade, Al-Gailani Werr, Curtis, McMahon, Martin, Oates and Reade2002; Reade and Anderson Reference Reade and Anderson2013) or based on cuneiform inscriptions (Bagg Reference Bagg2000) or remotely sensed images (Ur Reference Ur2005). On-going field investigation of the Northern Assyrian Irrigation System in the Duhok region by Udine University's Land of Nineveh Archaeological Project (LoNAP) has made it possible to carry out a systematic geoarchaeological field study of what was probably the most ambitious hydraulic engineering project in the history of Assyria (Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi and Kühne2018b). For the first time the opportunity was available to study the 347 km-long network not only through aerial and satellite imagery, but also through archaeological field survey, test trenches across the canals, and UAV (drone) technology. This network consisted of canals and offtakes dug into the earth and hewn into the bedrock, canalised rivers and wadis, earthworks, weirs, and stone aqueducts. The LoNAP project provides insights into their construction techniques and the impact of the introduction of gravity irrigation on the Assyrian agricultural economy in the hinterlands of Khorsabad and Nineveh.

Detailed reconstructions of the Northern Assyrian hydraulic system and its building phases have been extensively discussed elsewhere (Bagg Reference Bagg2000: 169–224; Jacobsen and Lloyd Reference Jacobsen and Lloyd1935; Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi and Kühne2018b; Oates Reference Oates1968; Reade Reference Reade1978: 61–72, 157–170; Ur Reference Ur2005). However, new field research by the University of Udine team has not only enabled an innovative functional and chronological interpretation of the Northern Assyrian irrigation network – in particular, changing our view of its Stage 3 (Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi and Kühne2018b: 89–107) – but also has provided additional evidence of canal construction in the Duhok and Ba'dreh plains pertaining to Stages 3 and 4 of the water management system.

During the 2017 LoNAP field season, two new canals flowing roughly from north to south were identified on CORONA imagery (1039 Mission) and surveyed on the ground in the plain between the Rubar Dashqalan stream and the Assyrian site of Jerahiyeh to the west, and the course of the Rubar Ba'dreh to the east (Figs. 3–4). The westernmost canal originated from the Rubar Dashqalan at Jerahiyeh. Unfortunately, the modern village covering the site's lower town and its immediate surroundings made it impossible to locate the canal head. The Jerahiyeh canal ran for approximately 2.5 km in a SSE direction and flowed into a tributary wadi of the Dashqalan stream, thus watering the plain to the south of the mid-sized (10 ha) Assyrian centre of Jerahiyeh. A further branched canal system was located to the east of the former. An almost 4 km long N-S canal was derived from the tributary wadi of the Rubar Dashqalan, into which flowed the Jerahiyeh canal. From this canal, at least three secondary dendritic canals branched off, irrigating the plain between the main canal and the Rubar Ba'dreh to the east. At its southern end, by the Neo-Assyrian site of Piruzawa, the canal flowed into a wadi, which downstream joined the main wadi that collected the water of the Khinis canal, taking it to the River Khosr.

Fig. 4. The Jerahiyeh and Piruzawa canals (remote sensing and mapmaking by Alberto Savioli; CORONA 1039–2088DA033, 22 February 1967). White arrows indicate canal courses and black arrows the feeder channels.

A further canal was located to the east of the Jerahiyeh-Piruzawa canals (Figs. 3 and 5). This was approximately 5 km long and was derived from the Rubar Ba'dreh watercourse in the southern outskirts of the modern Yazidi town of Ba'dreh. The canal head is clearly visible on the ground. It received water from an eastward oriented river bend, which must have facilitated the water's diversion due to the presence of a weir, of which no remains are visible in the riverbed today. From this point, the canal started a curving course towards the SSE, following the contours of the low rolling piedmont ridges in order to maintain the altitude required to keep the water flowing. Canals with winding courses are characteristic of Neo-Assyrian hydraulic systems and are paralleled by the Faida and Khinis canals, and by the probably contemporary canals of the Bahrka area in the Erbil Plain (Ur et al. Reference Ur, de Jong, Giraud, Osborne and MacGinnis2013: 105–106, fig. 11). Today the canal is not visible on the ground because it has been infilled by slope deposits and can be traced only from satellite imagery. Its eastern terminal part, however, cannot be detected in the CORONA photographs, although it seems very probable that at the Assyrian site of Khazneh (no. 148) the canal flowed into the watercourse fed by the karst spring located at the foot of the Ba'dreh Ridge near the present-day village of Beristek. This flowed into the wadi that received the water from the Khinis canal about 2.5 km to the west of its ending point. The Ba'dreh canal, with its ESE course, made the intensive cultivation of the plain south of it possible. No potential offtakes are visible in the satellite images or on the ground, and yet small distributaries may have existed but were too small to appear on CORONA images.

Fig. 5. The Ba'dreh canal (remote sensing and mapmaking by Alberto Savioli; CORONA 1039–2088DA033, 22 February 1967). White arrows indicate canal course.

It seems very likely that the Jerahiyeh and Piruzawa canals between the Rubar Dashqalan and the Rubar Ba'dreh and the longer Ba'dreh canal were part of Sennacherib's irrigation system, since they all flowed into wadis that were tributaries either of the Rubar Dashqalan, which joined the River Khosr, or of the wadi that carried the water from the Khinis canal to the River Khosr, and thus to Nineveh (Fig. 3). Moreover, these features are similar in morphology and behaviour to other Assyrian canals (see above) and lie in a region that was densely occupied in the Neo-Assyrian period, when the area witnessed an infilling of the settlement landscape in comparison to the previous Middle Assyrian period. It seems plausible that the Jerahiyeh-Piruzawa and Ba'dreh canals were part of the list of eighteen canals mentioned by Sennacherib in the Bavian inscription (Grayson and Novotny Reference Grayson and Novotny2014: no. 223, 8–11a), dug by the king to capture the water sources (karst springs and permanent streams) in the Zagros piedmont region crossed by the Northern Assyrian canal network. The above-mentioned canals were probably used to irrigate fields, gardens and orchards in the rolling plains between Jerahiyeh and the modern town of Sheikhan, thus enabling the intensification of agricultural production through the creation of intensive cultivation enclaves.

The evidence provided by these newly discovered irrigation canals is remarkable and shows that the Assyrian engineers had a thorough knowledge not only of the region's topography, but also of its hydrogeology, and were able to capture the water of many karst springs and streams in the piedmont belt in order to feed the irrigation network built by Sennacherib (Fig. 3).Footnote 8 In this respect, it is noteworthy that in the region between Wadi Bandawai to the west and Rubar Dashqalan to the east no traces of minor canals could be recognized in satellite images or on the ground. At first this was puzzling. But a more careful study of the water resources provided by karst springs in this piedmont region, where springs rise at the foot of the hill ranges, showed that while karst springs were present in nearly all the valleys on the southern flank of the Ba'dreh Range,Footnote 9 in the Chiya Al-Qosh valleys almost no karst springs feeding permanent streams existed. The Bandawai, Al-Qosh, Bozan and Dashqalan springs near Jerahiyeh are the only exceptions. In other words, in the region between Bandawai and Ba'dreh, with the exception of those fed by the above-mentioned springs, there were no permanent streams whose water could be directed into local irrigation canals. This explains why no irrigation canals could be built in this area.Footnote 10

Finally, a further canal was found in the westernmost part of the LoNAP survey area. Here, an approximately 3 km-long canal can be traced on CORONA images (Mission 1102) and on the ground (Figs. 3 and 6). The canal followed a WSW direction and was fed by a permanent stream flowing immediately to the west of the present-day village of Gutba and a cluster of two small and one larger Neo-Assyrian villages (nos. 20 Qasr Yezidiyn, 21, and 22 Gutba). After approximately 2 km, the canal was intersected by a wadi and continued to the south-west to an area where a small village-sized Neo-Assyrian site was located (no. 1045). Here, the canal probably flowed into a wadi draining into the Tigris. The purpose of this canal must have been local irrigation. Its association with clusters of rural Neo-Assyrian sites, its morphology and behaviour suggest that it was an Assyrian construction. Its location quite far from the canals belonging to Sennacherib's stage 3 and 4 irrigation system, together with the possible attribution of the Maltai and Faida canals to Sargon (see below), suggest that the Gutba canal may also have been built during the reign of this king to intensify local agricultural production.

Fig. 6. The Gutba canal (remote sensing and mapmaking by Alberto Savioli; CORONA 1102–1025DF007, 09 December 1967). Black arrows indicate canal course.

Taken together, the new evidence provided by the Ba'dreh, Jerahiyeh, and Piruzawa canals indicates that, wherever hydrogeological conditions were suitable, Assyrian hydraulic engineers canalised the water of streams fed by karst springs that rose from the bedrock at the foot of the Chiya Dudarash and Ba'dreh hill ranges in order to water the rolling piedmont plains of Nineveh's hinterland. This permitted the agricultural colonisation of the piedmont belt that in the previous Middle Assyrian period had been less intensively settled. After crossing the piedmont plains, these irrigation canals flowed into small wadis that brought the water to a larger eastern tributary of the River Khosr, which also received the water from the stage 4 Khinis canal. The Gutba canal, on the other hand, seems more likely to have been excavated to water local orchards and gardens and did not form part of the wider irrigation network built by Sennacherib.

The evidence of local irrigation in the LoNAP region described above and the potential offtakes derived from the main canals throughout stages 3 and 4 identified in the field or from satellite imagery (Fig. 3) show that Assyrian regional irrigation systems were not only hydraulic works meant to secure water supplies for the imperial leisure parks and gardens in the capital cities, but also – and above all – strategic elements of a highly planned subsistence economy and imperial landscape.

However, even when the practical irrigation function and potential of the Assyrian hydraulic systems have been fully acknowledged (Bagg Reference Bagg2000: 284–286; Ur Reference Ur and Frahm2017: 25–26; Ur and Osborne Reference Ur, Osborne, MacGinnis, Wicke and Greenfield2016: 165), hitherto no attempt has been made to quantify the actual impact that the introduction of intensive irrigation-based local cultivation had on the Assyrian agricultural economy. Recent LoNAP fieldwork and computer simulations based on an ASTER digital elevation model of the study region (Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi and Kühne2018b: 103–107) have revealed (Fig. 7) that large, high-productivity irrigation basins were formed in particular by the Maltai and Faida canals (nearly 3,000 ha) and the canals of Sennacherib's stage 4 (Jerwan-Mubarak: 10,430 ha and Jerahiyeh-Piruzawa-Ba'dreh: 4,851 ha). An estimate of the overall surface area made available for intensive cultivation based on gravity irrigation in the entire Nineveh hinterland gives about 300 km2, to which approximately 4,000 km2 of dry-farming land in the wider northern part of the ‘Assyrian Triangle’ may be added (Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi and Kühne2018b: 106). Even if this figure should be halved – since Neo-Assyrian legal texts show that cereal cultivation was based on a fallow system in which at least 50% of the arable land was left fallow every year (Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi and Kühne2018b: n. 39) – an overall surface area of 2,150 km2 was potentially available for crops in the region, of which about 150 km2 could have been used for intensive irrigation agricultureFootnote 11 and the remaining land devoted to extensive dry-farming.Footnote 12

Fig. 7. Map of the natural hydrography of the northern part of the Assyrian Triangle showing canals in Nineveh's hinterland, Neo-Assyrian sites (size proportional to site extension), areas that could be irrigated by feeder channels (blue in online version) and land that could be cultivated by dry-farming (green in online version). Relief map and analysis by Alessandro Perego based on ASTER GDEM (Global Digital Elevation Model) V2.

In the centrally planned imperial landscape created by the Assyrian rulers of the ninth to seventh centuries B.C., canals (and rivers) may have also been used as waterways for the transportation of staple food items and other materials (Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi, Gaspa, Greco, Morandi Bonacossi, Ponchia and Rollinger2014; 2018b: 107–108; Ur and Reade Reference Ur and Reade2015). In a region such as Northern Mesopotamia, where transport occurred mainly overland by means of caravans of pack animals, the long-distance transfer of agricultural surpluses was by far too expensive to be a viable option for supplying distant regions, and the consumption of agricultural produce was essentially local (Düring Reference Düring2020: 22 with more references). The low-friction bulk transportation of goods via barges on rivers and canals would have been both cheaper and faster – and, making use of the Nineveh and Nimrud irrigation systems (Figs. 2 and 7), would have enabled the more effective transportation to the capital cities of the cereals produced in their hinterlands.

In summary, in the northern part of the ‘Assyrian Triangle’, corresponding to the hinterlands of the Assyrian capitals Nimrud, Khorsabad and Nineveh, an integrated and centrally planned landscape was imposed, based on the creation of massive irrigation infrastructures (the Northern Assyrian and the Nimrud irrigation systems) and the intensification of settlement. This branched network of canals had a twofold strategic role. On the one hand, it allowed for increased agricultural productivity in the countryside around the capitals and the establishment of a solid local economy based in their immediate environs. On the other hand, it determined the creation of an efficient network of mid-distance waterways for the low-cost transport to the capitals of bulk food items produced in their hinterlands, in the Duhok, Al-Qosh, Ba'dreh, Sheikhan and Navkur plains.

Lastly, the excavation of extensive irrigation systems across the Assyrian homeland was associated with the ideological marking of the new engineered landscapes by commemorative monuments such as impressive rock reliefs, rock steles, and royal inscriptions placed at symbolically charged locations (Harmanşah Reference Harmanşah2013: 73; Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi1988; 2018a: 56; Shafer Reference Shafer, Cheng and Feldman2007). Throughout the Northern Assyrian hydraulic system, massive rock reliefs were carved along the canals or at their heads in Maltai (Bachmann Reference Bachmann1927), Faida (Reade Reference Reade1978), Shiru Maliktha (Reade Reference Reade, Al-Gailani Werr, Curtis, McMahon, Martin, Oates and Reade2002), and Khinis (Bär Reference Bär2006; Jacobsen and Lloyd Reference Jacobsen and Lloyd1935; Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi2018c), while cuneiform celebratory inscriptions marked the Khinis canal head, the Jerwan aqueduct (Jacobsen and Lloyd Reference Jacobsen and Lloyd1935) and possibly also the other four aqueducts discovered by LoNAP along the Khinis canal (Fig. 3; Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi and Kühne2018b: 101–103). These monuments were part of a programme of ideological transformation and royal commemoration of the Assyrian landscape that was stamped like a signature by the rulers involved, profoundly modifying the space of the empire's core area, along with the mental and symbolic perception the people had of this newly built imperial landscape.

The Faida canal: The discovery of a seriously endangered archaeological site and the Kurdish-Italian Faida Archaeological Project

The Faida canal is part of the Northern Assyrian Irrigation System (Figs. 3 and 8), which stretches across the present-day Governorates of Duhok and Ninawa, straddling the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (Stages 3–4 of the system) and the northern Mosul plain (Stages 1–2). The canal is located along the Duhok-Mosul highway at the western foot of the E-W oriented Chiya Daka hill range, east of the village of Faida, about 12 km as the crow flies to the south of the western outskirts of Duhok.

Fig. 8. Map of the Faida canal with possible offtakes and feeder channels (remote sensing and mapmaking by Alberto Savioli).

Archaeologists have known of the Faida canal since April 1973, when the British archaeologist Julian Reade visited the site and recorded three rock reliefs carved along the canal's eastern bank (Reade Reference Reade1973: 203–204; 1978: 159–164).Footnote 13 The rectangular panels with sculpted bas-reliefs had been almost entirely buried by the deposits of soil and colluvial debris eroded from the side of Chiya Daka hill, at the base of which the canal was dug, immediately to the east of the village of Faida. Only the upper parts of the sculpted panels could be seen protruding from the debris that filled the canal.Footnote 14 Five years later, in April 1978, in the wake of Reade's first exploration, the site was visited again by Rainer M. Boehmer. During his short visit he also recorded the presence of the reliefs, which he described only briefly, providing additional photographs of the panels emerging from the canal fill and of the canal itself (Boehmer Reference Boehmer1997: 248–249, pls. 38–44). In those years of conflict between the Kurdish Peshmerga and the army of the Baathist regime, the region's political and military instability made thorough exploration and excavation of the site impossible.

The three known Faida reliefs were registered in the official Iraqi inventory of archaeological sites as no. 2269 on August 14, 1983. However, the full extent of the Assyrian sculptural programme along the Faida canal became clear only forty years after its first partial discovery. In August 2012, following in Reade's and Boehmer's footsteps, the LoNAP team visited Faida, surveyed all of the canal that was visible and identified six new reliefs carved along its east bank, for the most part buried by the fill of the canal (Fig. 8: nos. 1, 5–9), thus bringing the total number of known reliefs to nine.Footnote 15

The advent of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS or Daesh) in Mosul and the Nineveh Plain in June 2014 dramatically changed the situation in the Mosul region up to the area of Tell Uskof, south of Faida. The entire region soon became a target of ISIS expansionism (Warrick Reference Warrick2015); the archaeological site of Faida was located only about 20 km north of the front line between the Kurdish Peshmerga and the ISIS fighters. This scenario persisted until mid-2017, when ISIS was defeated in Mosul and the Nineveh Plain, resulting in the demise of the ‘Caliphate’, even though its enduring defeat has not yet been assured. The general situation of reduced security in the area of Faida during the years of the ‘Caliphate’ led to the postponement of the archaeological project involving excavation of the canal and the associated rock reliefs.

During this period, however, the archaeological complex became the target of increasing damage caused by the cement brick plants located along the canal course between Reliefs 4 and 7 and a poultry and cattle farm near Relief 9 (Fig. 8). In 2015, workers of one of the four plants removed the debris that filled a stretch of the Assyrian canal with a mini-excavator in order to reactivate the canal and one of its off-takes as drainage channels, to avoid the regular flooding of the plants’ working areas caused by surface runoff down the hillsides following winter rains. The expedient turned out to be effective but endangered the canal and its reliefs.

In 2017, the hitherto most severe damage was caused to the Faida sculpted panels. Relief no. 9, of which only the uppermost part was visible at the surface, was partially destroyed by bulldozing during preparatory work for the enlargement of a cattle shed belonging to one of the local farms. The upper half of this very well preserved relief was entirely removed when the bulldozer cut into the hillside to make space for the building's extension (Figs. 9 and 10a–b).

Fig. 9. Bulldozer damage in the area of Relief 9; the damaged relief is located underneath the person in the photograph.

Fig. 10. Relief 9 (a) before and (b) after the damage.

In 2018, the ancient canal was again damaged by the laying of the pipe of the new Faida Water Project, constructed in order to provide the village with water (Fig. 11). The route of the modern water pipe has not only damaged the ancient canal, but also barely avoided one of the reliefs (no. 4), which only narrowly escaped destruction. Finally, in the spring of 2019, illicit excavators partially brought to light the same relief, damaging the sculpted surface of the panel in the process (Fig. 12).

Fig. 11. The new Faida aqueduct (hilltop) cutting the Assyrian canal. The excavation in the centre, in the large trench dug for the aqueduct pipe, is an archaeological test trench in the Assyrian canal. Immediately to its left, a pile of earth marks the position of Relief 4.

Fig. 12. Damage (abrasion marks) to Relief 4 and the canal bed caused by illegal excavation.

The constant threat of damage to which the Faida reliefs are exposed is an example of the serious condition affecting the whole of the Duhok Governorate's vast patrimony of rock art. All of the sites with rock reliefs, dating from the middle of the third millennium B.C. to the first centuries A.D., have been seriously, and in some cases irremediably, damaged by vandalism, with the destruction of important parts or even entire monuments (Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi, Traviglia, Milano, Tonghini and Giovannelli2021). The pervasive increase in human presence and activity throughout the region, with its innumerable ramifications and consequences (urban sprawl, uncontrolled intensification of productive and extractive activities, vandalism, illicit excavation) constitutes a very serious threat to the survival of the region's rock art (and of archaeological sites in general).

Due to the increasing threats endangering the unique Faida rock art complex, in 2019 a rescue project was launched by the joint Kurdish-Italian initiative to salvage the Assyrian canal and its reliefs. For the first time, the Kurdish-Italian Faida Archaeological Project (KIFAP), co-directed by Hasan Ahmed Qasim and Daniele Morandi Bonacossi, provides an opportunity to study through reconnaissance and archaeological excavation one of the canals built by Assyrian rulers in this region and commemorated through the execution of bas-relief panels. These panels are threatened by weathering, karst phenomena, the expansion of local productive activities, vandalism and illegal excavation. The goal of the project is the comprehensive archaeological investigation of the canal and rock art complex and its recording with state-of-the-art methods and techniques, including laser scanning, remote sensing and UAV technology. Moreover, thanks to funding provided in 2020 by the ALIPH Foundation Emergency Relief Grant and the Gerda Henkel Stiftung, KIFAP will draft a project for the site's protection and safeguarding, for the monitoring and conservation of the reliefs, and finally for the creation of a Faida Archaeological Park that will permit the local population to enjoy all the cultural, spiritual and social benefits offered by this impressive archaeological site.Footnote 16

The canal's course and construction

Today the Faida canal can be clearly traced from satellite images and on the ground for 8.6 km (Figs. 8 and 13). Its course has been mapped on CORONA satellite imageryFootnote 17 and 1955 Hunting Aerial photographsFootnote 18 and confirmed in the field. The canal was hewn out of the limestone bedrock at the base of Chiya Daka. The cut is rectangular in section; where entire cross-sections are visible because of natural erosion or through excavation near the ten rock reliefs, it varies in width between 3 m and 3.80 m. In its upper course, in stretches where erosion has exposed canal cross-sections, its width can reach 4.20 m. The relative variability of the canal's width shows that Assyrian hydraulic engineers adjusted it according to the topography.

Fig. 13. The Faida canal (remote sensing and mapmaking by Alberto Savioli; CORONA 1039–2088DA032, 22 February 1967). White arrows indicate the canal course and black arrows the possible feeder channels.

Although in 2019 the exact location of the canal head on Chiya Daka's northern flank had not yet been identified on the ground, the survey of the Faida canal identified a series of karst springs and wells in this area that appear as irregular depressions in the ground and are located in several small wadis on the northern face of the hill range (Fig. 14). The easternmost cluster of karst features is located about 300 m east of the point where the canal can first be traced on the ground and from satellite imagery, so it is reasonable to assume that the water from them was redirected through the wadis to the canal head. When we surveyed these wadis in August 2012, at the peak of the Iraqi summer, we counted at least six karst springs/wells, all of them full of water (Fig. 15). As already argued by Julian Reade (Reference Reade1978: 159), it is very likely that the Assyrian canal was fed by these and other karst features located in the adjoining wadis of the Chiya Daka that could guarantee a constant water supply throughout the year to the Faida canal. Recent fieldwork, including a hydrogeological survey by karst phenomena specialists in summer-autumn 2021, permitted identification of the Faida canal head's location and a better understanding of the karst system feeding it, with a water supply drawn from multiple sources originating from the numerous springs and wells found along its course. Results of this recent fieldwork will be published in future. A similar situation has been observed along Sennacherib's Khinis canal (Fig. 3), which received water from at least 12 karst springs recorded by LoNAP along its course, particularly in the stretch between the Jerwan aqueduct and the site of Mahmudan to the south.

Fig. 14. Map of the Faida canal head area (remote sensing and mapmaking by Alberto Savioli).

Fig. 15. One of the karst springs in the Faida canal head area seen from the south (August 2012).

From the point where the canal starts to be visible on the ground it flowed westward, looping around the base of the Chiya Daka along a course dictated by natural contours and the need to maintain a constant slope. Along this stretch of the canal natural erosion has been very active, exposing the canal bed in several sectors (Fig. 14). Along the Chiya Daka's northern flank a palimpsest of canal traces and other linear anomalies has been traced via remote sensing (Figs. 14 and 16). Some of these pertain to recent trenches excavated by the Iraqi army.

Fig. 16. The Faida canal head area (remote sensing and mapmaking by Alberto Savioli; CORONA 1108–1025DA007–8_38n, 04 December 1969). White arrows indicate the canal course.

Beyond this area, the canal rounds the western spur of the hill range, reaching the area of Faida village, and then proceeds in a roughly ESE direction, in a line curving along the hillside. At various points along the canal, the satellite images show feeble linear anomalies departing from it. These features might indicate the presence of small offtakes feeding possible distribution channels extending downslope to irrigate the neighbouring fields (Figs. 8, 13–14, 16). For example, two possible feeder channels branch from the northern stretch of the main canal in the area of the canal head. Both channels join a wadi that crossed the plain east of Gir-e Pan and could have supplied the ancient fields with irrigation water. At least fifteen potential offtakes feeding as many feeder channels have been identified from satellite imagery and in the future will be verified on the ground by means of small trial trenches (Fig. 8). As mentioned, in 2015, the personnel of one of the nearby cement brick plants reactivated a stretch of the main canal and one of the possible offtakes located between rock reliefs 3 and 4 in order to alleviate the flooding of a brick drying area by seasonal rains. The offtake, which is about 1.20 m wide, proved to be very effective even as a drainage channel.

The main canal was equipped with several overflows, which allowed the draining of excess water caused by heavy rain during the winter-spring season. At least two have been identified so far. The northernmost one is associated with relief no. 3 and is a shallow feature (about 0.30 m deep) with a 1.10 m wide semi-circular cross-section. The bottom of the overflow, which was chiselled into the limestone bedrock, is located 0.55 m above the canal bed. This gives a clear indication of the possible normal water depth in the Faida canal, which cannot have exceeded this limit. Another feature characterising the canal in relation to the sculpted panels provides more information in this respect. When the Assyrian artists carved the reliefs into the limestone of the eastern canal bank, they cut back the bedrock face to get a smooth, even working surface. In doing this, they created steps or banquettes 0.20-0.40 m deep at the base of the panels. The upper surface of these steps is located between 0.30 and 0.50 m above the canal bed. It seems very plausible that the original water level did not cover the step. This evidence, taken together with the information provided by the Relief 3 overflow, suggests that the regular depth of water flowing in the canal over the year was probably not greater than 0.30-0.40 m. This figure also fits well with the data provided by the canal slope gradient, which is 0.063%, i.e. about 0.6 m per km, which is a relatively slight incline. This must have meant fairly slow movement of water in the canal and caused its gradual silting up due to the considerable quantity of mud and debris that would have eroded from the hillside and gradually filled the canal, making its periodic dredging necessary.

A second overflow identical to that described above has been identified at the surface along the western canal bank about 50 m SE of Relief 7. Another extremely interesting feature is located at the SE end of Panel 7. It is a channel less than 1 m wide hewn into the bedrock uphill of the main canal and perpendicular to it. It is possible that this inlet channel was used to convey the runoff water collected from Chiya Daka's western flank into the main canal. If this is correct, it may be imagined that there was a network of upslope channels that served to collect the runoff from the hillside and feed it into the main canal.

Significant evidence was also obtained regarding the construction phase of the main canal. Along the western canal bank, a series of post-holes placed at regular intervals of 2.40-2.60 m has been identified. The post-holes, with diameters of 0.25-0.30 m, were dug into the bedrock to a depth of 0.50-0.77 m; their bases do not reach the level of the canal bed. The excavation of the sculpted panels has shown that identical post-holes were also dug into the rock of the eastern canal bank. Here they are less numerous because the only stretches of the canal excavated to date correspond to the locations of the carved panels, where the holes would have been removed by the carving of the reliefs. In a few cases, however, post-holes were still present (e.g. next to Reliefs 5/10 and 7), indicating that the post-holes were originally paired on the opposite sides of the canal. At first, we interpreted this evidence as relating to posts driven into the bedrock by the workers who excavated the canal with the aim of cracking the limestone bedrock and thus facilitating its excavation. However, if that were the case, a pattern of radiating cracks should be visible at the holes’ bottoms. This evidence is lacking.Footnote 19 After also rejecting the less plausible hypotheses of a canal covered by linen sheeting to reduce water evapotranspiration during the summer or marked by standards, a further possibility was suggested by Cristina Tonghini, who proposed that posts could have been driven into the bedrock to trace the course of the canal on the ground before its excavation. This seems – at least for the moment – the most plausible interpretation of the available evidence, although the diameter of the post-holes might be rather large for this purpose. The continuation of fieldwork may unearth more information regarding this aspect of the canal's construction.

Finally, more fieldwork is also needed to bring into sharper focus the canal's termination. After Relief no. 9, the Faida canal followed a looping course around the Chiya Daka's southern base before feeding its water into a small natural wadi near the modern village of Daka, which overlies a small Neo-Assyrian rural site that might have been established to control the canal's endpoint (Figs. 8, 17–18). The canal's course can be clearly traced to a wadi that today cuts it, located about 850 m east of the easternmost known sculpted panel. From here its course can be followed discontinuously on remotely sensed images and on the ground to the northern outskirts of the Assyrian (and present-day) village, where it flows into a wadi which joins a wider drainage system that forms the Rubar Buqaq and flows into the Tigris south of Faida. No traces of continuation of the Faida canal to the east beyond this wadi could be detected on satellite or aerial imagery or on the ground. This evidence indicates that, contrary to Julian Reade's hypothesis (1978: 162–164), the Faida canal never joined the Bandawai canal, forming a single irrigation system eventually flowing into the River Khosr (Fig. 3; see also Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi and Kühne2018b: 92–93; Ur Reference Ur2005: 329 and, more in depth, below).

Fig. 17. Map of the Faida canal end (remote sensing and mapmaking by Alberto Savioli).

Fig. 18. The Faida canal end (remote sensing and mapmaking by Alberto Savioli; CORONA 1108–1025DA007–8_38n, 04 December 1969). Black arrows indicate the canal course.

Water, gods and kings: The canal's sculpted panels and their ideological and religious meaning

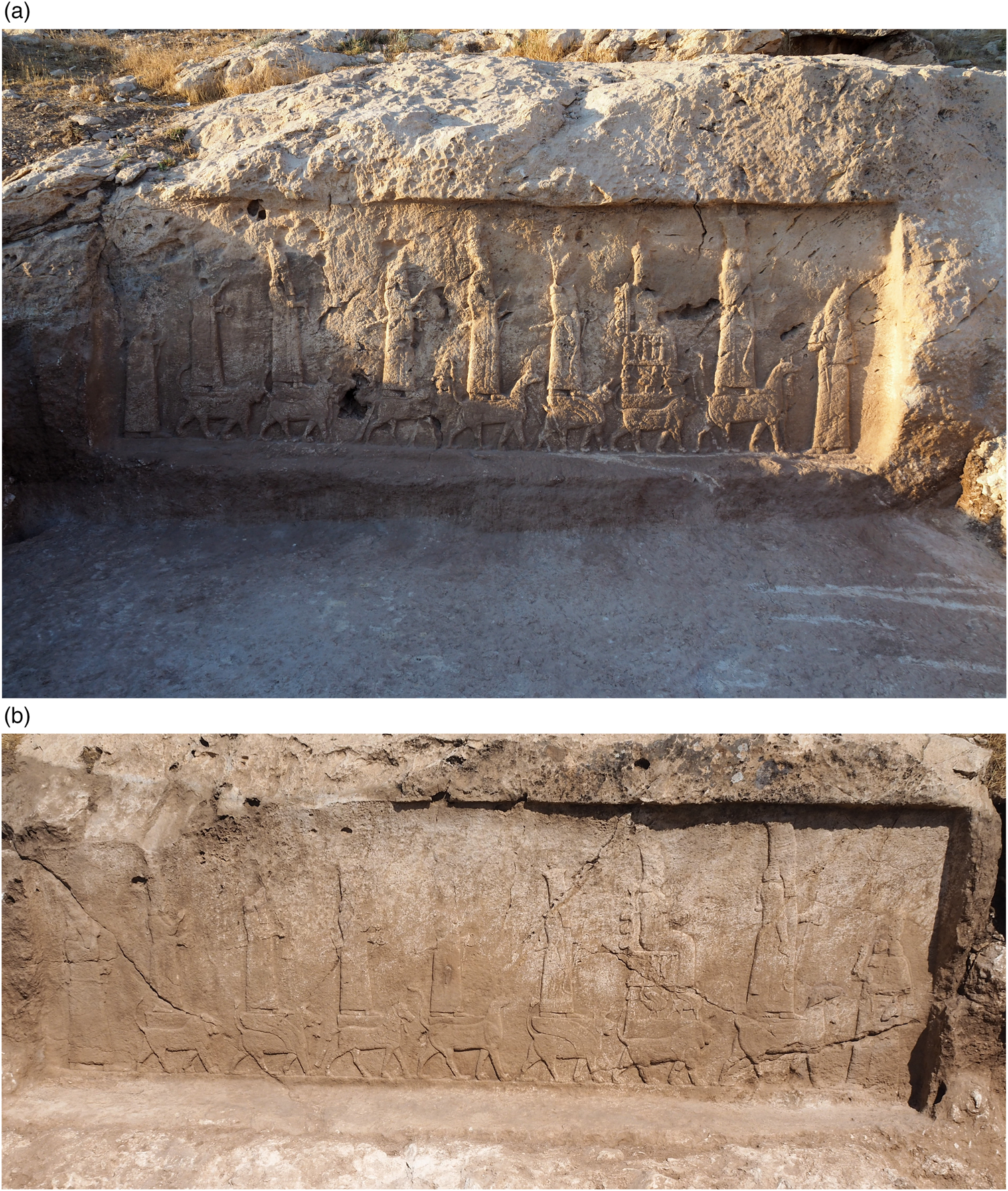

To date, excavation of the Faida canal has brought to light ten impressive sculpted panels that make the site of Faida an extraordinary and unique monumental complex without parallels in ancient Near Eastern rock art. The panels have slightly different dimensions; the frames surrounding them vary from 1.25 m to 1.62 m in height and from 4.30 m to 5 m in length.

The spatial distribution of the panels along the canal bank remains to be clarified (Fig. 8) since a segment of the canal long enough to be considered representative has not yet been systematically excavated. It has been argued that the rock reliefs were positioned at locations corresponding to possible offtakes distributing the canal water into feeder channels that irrigated the surrounding countryside (Ur Reference Ur2005: 337). This seems very plausible, and we hope that resumption of work at the site after the pandemic crisis will allow for the excavation of test trenches targeting all potential offtakes appearing in remotely sensed images (Figs. 8 and 13), in order to ascertain the presence of distributaries and their possible association with carved panels.

Some panels occur in pairs placed side by side (Fig. 19),Footnote 20 whilst others are isolated. The excavation of Relief no. 5 led to the discovery of a tenth panel adjacent to it (no. 10) that was not visible on the surface because it was entirely covered by debris that filled the canal. It is therefore highly probable that further, not yet identified, panels are still hidden along the canal's course.

Fig. 19. Reliefs 6 and 7 and canal bed from a drone (north is to the left; photo by Alberto Savioli).

Like the Maltai reliefs, the Faida panels were carved on regular surfaces delimited by purposely created frames, which protrude from the reliefs’ background by 0.10 m on average, thus protecting them from rainwater running down the panels’ sculpted surfaces.Footnote 21 In spite of this, their state of preservation is very variable. Reliefs 4–9 are rather well preserved in all their parts, although with some differences, while only the lower parts of Reliefs 1–3 and 10 are preserved. Generally, the sacred animals and the lower part of the king's body are well preserved, while the divine statues and the torso and head of the ruler have often not survived.Footnote 22 In spite of the fact that after its abandonment the Faida canal must have filled up rather quickly with earth and debris eroded from the Chiya Daka's hillside, during the period in which they were exposed the reliefs were damaged by rain and wind erosion, exposure to heat and cold, and the impact of direct solar radiation on the stone. After the infilling of the canal, the process of decay of the reliefs must have actively continued, due to water infiltrating into the upper part of the canal's fill, both from the surface (rainwater) and from the hillside (from the karst systems). This long and still ongoing process of deterioration accounts for the present state of preservation of the panels. While minero-petrographic and physical characterization of rock samples collected from Faida and mineralogical, chemical and biological analysis of the deterioration products and biodeteriogens have already been accomplished, as soon as the Covid-19 health crisis permits, a comprehensive analysis of the site will be conducted, to gather data on its hydrogeological situation and stability and the reliefs’ insolation levels and exposure to humidity and water. The data obtained will be used to design a comprehensive and sustainable strategy for the monitoring, protection and conservation of the reliefs. In the meantime, given the severe threats endangering the archaeological site,Footnote 23 in October 2019, after excavation and recording, the reliefs were provisionally protected from weathering and vandalism by laying of non-woven fabric sheets over the reliefs and backfilling with gravel and earth.Footnote 24

Like the four panels at Maltai (Bachmann Reference Bachmann1927; Justement Reference Justement, d'Alfonso, Calini, Hawley and Masetti-Rouaultin press; Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi and Kühne2018b; Reade Reference Reade1989; Thureau-Dangin Reference Thureau-Dangin1924), the Faida reliefs portray the Assyrian ruler represented twice, at both ends of each panel, in front of and behind the cult statues of seven divinities standing on pedestals in the shape of striding animals (Fig. 20a, b).Footnote 25 All reliefs therefore represent a worship scene of divine statues by a king, which conceptually is close to the famous wall painting from reception Room 12 of Residence K in Khorsabad, depicting King Sargon followed by an accompanying officer – probably crown prince Sennacherib – in front of the statue of the god Ashur on a dais (Albenda Reference Albenda2005: 86–89; Guralnik Reference Guralnik, Matthiae, Pinnock, Nigro and Marchetti2010: 791, fig. 10; Loud and Altman Reference Loud and Altman1938, 85, pls. 88–89).

Fig. 20. a) Relief 4; b) Relief 8 (photos by Alberto Savioli).

With the exception of the right-hand royal image, the figures are shown in profile facing to the spectator's right, or their own left, and thus look in the same direction as the current flowing in the channel. From right to left, the deities wearing horned tiaras can be identified as follows (Fig. 21). Ashur, the chief Assyrian god,Footnote 26 stands on a mušḫuššu-dragon and a bull or an abūbu-deluge monster.Footnote 27 Ashur is also represented standing on the dragon and abūbu mythological creatures in the ‘Large Panel’ and the canal head monolith at Khinis (Bachmann Reference Bachmann1927: 7–13; Bär Reference Bär2006; Justement Reference Justement, d'Alfonso, Calini, Hawley and Masetti-Rouaultin press; Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi2018c; Ornan Reference Ornan, Cheng and Feldman2007; Pongratz-Leisten Reference Pongratz-Leisten, Johannes Bach and Finkin press; Winter Reference Winter, Nissen and Renger1982: 367) and on Sennacherib's ‘Seal of Destinies’, the cylinder seal impression across the top of a tablet bearing the adê (loyalty oath) for Esarhaddon's succession to the Assyrian throne (Fales Reference Fales2012; Justement Reference Justement, d'Alfonso, Calini, Hawley and Masetti-Rouaultin press; Parpola and Watanabe Reference Parpola and Watanabe1988: no. 6). While in the Maltai reliefs Ashur is always standing on the mušḫuššu-dragon and the abūbu-deluge monsterFootnote 28, in the Faida panels where Ashur's figure is preserved (nos. 4–5 and 8–9) the god is represented on a mušḫuššu and a bull.

Fig. 21. Composite drawing of the Type A tableau (drawing by Elisa Girotto).

Like all other male deities, Ashur wears a sword on his left side. The god carries a rod and a ring with an inscribed miniature figure of the king in his left hand and a curved weapon identifiable as a sickle sword with the head of an abūbu-monster in his right. The miniature royal image inscribed in the ring and the curved weapon with an abūbu head also appear at Khinis on both the ‘Large Panel’ and on the canal head monolith. This evidence indicates that the abūbu was a specific attribute of Ashur, even though it is also present in the representations of the gods Sîn and Adad (see below).

Ashur is followed by his spouse Mullissu, represented the same size as Ashur, sitting on a decorated throne held up by a lion. The throne is carved with two registers of figures supporting it. In the lower register an abūbu, a girtablullu Footnote 29 and a royal figure sustain the goddess’ throne. In the upper register, three royal figures are depicted with two other apotropaic figures that can be identified either as uridimmus, creatures with a human head and torso and the lower body and tail of a lion (Nakamura Reference Nakamura, Petit and Morandi Bonacossi2017: 219–221; Wiggermann Reference Wiggermann1992: 172–173), or ‘scorpion-men’, scorpion-tailed, bird-footed figures with human head and torso and hands held high above the head with upturned palms, representing a wingless version of the girtablullu (Green Reference N1985).Footnote 30 The uridimmus derived from the creatures of Ti'amat (Frayne and Stuckey Reference Frayne and Stuckey2021: 358) and were servants of Marduk and Ashur, bringing well-being and prosperity. The scorpion-man was also a beneficent demon, protective against evil demons and sicknesses (Green Reference N1985: 76). Mullissu's elaborately decorated throne was therefore supported by cosmic and apotropaic figures pertaining to Ashur's and Shamash's sphere of power and by royal images. Moreover, the back of the goddess’ throne is equipped with five globes decorated with concentric circles. A similar set of elements appears on a Neo-Assyrian bronze amulet held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, representing on the reverse Ishtar (or Mullissu) enthroned, mounted on a lion-dragon and a worshipper (Braun-Holzinger Reference Braun-Holzinger1984: 288, pl. 55; Ornan Reference Ornan2005: 83, fig. 101). The goddess’ throne has six stars on the back. A Neo-Assyrian seal in the Israel Museum shows the healing goddess, Gula, standing above a dog (Ornan Reference Ornan2005: 100, fig. 125). The back of the throne is again equipped with six stars. Finally, the golden stamp seal of Queen Hama, wife of Shalmaneser IV, found in Tomb III underneath Room 57 in the Northwest Palace at Nimrud (Spurrier Reference Spurrier2017), has an engraved scene showing a female worshipper, most likely the queen herself, standing before an enthroned goddess resting on a crouching lion identifiable as Mullissu. The back of the throne is furnished with six globes as in the Faida and Maltai reliefs. Based on this iconographic evidence, it seems plausible to equate the globes on Mullissu's throne in Maltai and Faida and on Hama's golden seal with astral symbols, as seen on the amulet in the Metropolitan Museum and the Israel Museum seal.

In the Faida and Maltai reliefs, Mullissu (like Ashur and Ishtar) wears her hair in a thick braid resting on her back. This seems also to have been a royal fashion, since the same braid is shown on Queen Hama's seal and the relief of Queen Naqia, wife of Sennacherib and mother of Esarhaddon (Gansell Reference Gansell, Feldman and Brown2013: fig. 3). Lastly, like Ashur and all the other deities except Adad, Mullissu carries a ring with the king's figure inscribed in her left hand, while her right hand is raised, as in the cases of Nabû, Shamash and Ishtar.

The third divine figure is that of the moon god Sîn, identified by the lunar crescent topping his tiara, holding a rod and ring in his left hand and standing on an abūbu-lion. In his right hand, the moon god carries the same curved weapon with the abūbu head as Ashur.

The identification of the divine figure following Sîn and standing on a mušḫuššu-dragon has long been the subject of scholarly debate. Discussing the Maltai reliefs, where the figure appears in the same position after the moon god, Reade suggested identifying it with Anu or Enlil (1989: 321), but a more thorough analysis makes an identification with the god of wisdom, Nabû, more likely. First, the god stands on a mušḫuššu-dragon, which is the attribute of Ashur and his son Nabû. Moreover, an unprovenanced Neo-Assyrian copper plaque in the shape of an amulet kept in the British Museum (BM 118796) is engraved in its upper part with a scene representing four deities (Postgate Reference Postgate1987). Two gods on mušḫuššu-dragons alternate with two suppliant goddesses standing on brick daises. Each of the deities holds a ring in its left hand, except for the second male god on the mušḫuššu, who holds a wedge-shaped stylus. While the first god is presumably Marduk, who is mentioned in the dedication below the divine scene, the second male deity with the stylus is certainly Nabû, to whom the dedication is made by a certain Ashur-reṣua for his life. The British Museum plaque offers compelling evidence for interpreting the fourth divine figure in the Faida and Maltai reliefs as the god of wisdom, son of Marduk/Ashur. A brick with stamp impression from the Nabû temple at Nimrud bears the symbols of Marduk and Nabû, thus confirming the function in Assyria of the mušḫuššu-dragon, as the attribute of both divinities (Sass and Marzahn Reference Sass and Marzahn2010: fig. 2). In the Nabû temple at Khorsabad, a fragment of a bronze sheet decorated with a mušḫuššu supporting Nabû's stylus was found (Loud and Altman Reference Loud and Altman1938: 96, pl. 50: 22). Finally, another reason for identifying the god behind Sîn as Nabû is Nabû's high elevation in the pantheon of the Late Assyrian period (Pomponio Reference Pomponio1978; Pongratz-Leisten Reference Pongratz-Leisten1994: 104–105).

Nabû is followed by the sun god Shamash on a harnessed horse, the god's sacred animal (Frayne and Stuckey Reference Frayne and Stuckey2021: 321), probably an allusion to the chariot carrying the god on his daily journey across the sky. A winged disc tops Shamash's rod.Footnote 31

The storm and thunder god Adad, with a crown topped by a star and standing on an abūbu-lion symbolising the flood and a bull, follows the sun god. The god holds a bundle of thunderbolts in each hand. As the god responsible for rain, epithets of Adad are “irrigator” and “canal inspector of heaven and earth” (Frayne and Stuckey Reference Frayne and Stuckey2021: 4), which seem very appropriate appellations in the case of Adad's representation on the panels associated with the Faida and Maltai canals.

Finally, Ishtar, the goddess of love and war, standing on a lion and wearing a high horned crown with an eight-pointed star, closes the series of deities’ statues represented on their sacred animals or Mischwesen. According to MacGinnis (Reference MacGinnis, Finkel and Simpson2020: 160), the headdress topped by a star might be a distinctive feature distinguishing Ishtar of Arbela, as seen on the famous Louvre stela from Til-Barsip.

As in the four Maltai panels, two figures of the king, facing left and right, stand in front of and behind the divine statues. The rulers wear the distinctive long garment and high crown of Assyrian kingsFootnote 32 and are depicted worshipping the divine statues with a mace in their left hands and an object held up to the nose in their right hands, in the labān appi prayer gesture conveying humility in front of the gods.Footnote 33

With the exception only of Relief no. 8, which was carved in rather low relief (Fig. 20b), the figures in the Faida panels are engraved in marked relief and a graphic style that pays attention to detail, for example in the execution of the attributive animals of the deities and the throne of Mullissu. As in Maltai, the repetition of the same motifs in an endless series lends the Faida panels a certain monotonous character. However, the deep relief of the panels and the attention given to the execution of details, for example in the harness of Shamash's horse, reveal that the Maltai and Faida panels represent a serial production carved by skilled artists.

Overall, the Faida reliefs are so similar to the Maltai panels in terms of scenes depicted, iconography, style, and antiquarian elements such as the triple-armed earrings and bracelets with rosettes worn by kings and deities, that they can be considered replicas of one another. This suggests that the relief series belonged to one and the same sculptural and ideological programme and that the associated canal systems were conceived as part of the same irrigation project (see below for more details).

One of the most striking discoveries made in this impressive rock art complex is that two different versions of the divine worship scene had been carved along the Faida canal bank and – even more importantly – that one of them is unquestionably earlier in date than the other. We have dubbed them Type B and Type A tableaux, respectively. Panels 5 and 10 are a pair of reliefs placed side-by-side (Figs. 8 and 22). With the exception of the upper parts of the figures of Mullissu, Ashur and the image of the king on the right-hand side, Relief 5 – which is smaller in size – is rather well preserved, while the adjoining larger Relief 10 has been seriously damaged by erosion to the point that a large part of the tableau cannot be clearly perceived due to the loss of the sculpted surface. The overall scene, however, remains comprehensible and significant parts of it, especially to the right, still survive, albeit fragmentarily.

Fig. 22. Drone image showing the earlier Relief 10 and the later Relief 5 (photos by Alberto Savioli; editing by Francesca Simi).

Relief 10 was originally isolated. When Relief 5 was carved on the canal bank slightly upstream of it, the left edge of the earlier Relief 10 was cut away by the new panel, which was partly superimposed on it. The figures of Ashur and the king in the later Panel 5 have removed the shaft of a column, the double volute capital of which is still visible (see below), and most of the left royal figure in Panel 10 (Figs. 23–24). This clearly shows that the Faida canal reliefs were not all carved at the same time and that Type B tableauxFootnote 34 predate those of Type A.Footnote 35 In both Type B reliefs (Fig. 23), the figures of the Assyrian sovereign are much larger than the statues of the deities on their emblematic animals. The animals and mythological creatures supporting the deities walk on a surface that is higher than that on which the king's feet stand. In addition, the entire scene is depicted under a pavilion supported by two columns with circular basesFootnote 36 and double-volute proto-Aeolian capitals of the type represented in the famous Room 7 relief of Sargon's palace in Khorsabad (Botta and Flandin 1849–50, II, pl. 114; Reade Reference Reade2019: 88–94) and the Room H relief of Ashurbanipal's North Palace in Nineveh (Barnett Reference Barnett1976: pl. XXIII). The pavilion represented on the Type B tableau can be identified as a qersu, a portable shrine consisting of a wooden baldachin covered with linen. These shrines were often used by the Assyrian army on the march as a camp chapel and were associated with portable divine symbols (šurinnu or urigallu), shown revered during campaigns on the Balawat Gates and other imagery (May Reference May, Kogan, Koslova, Loesov and Tishchenko2010: 469–471).Footnote 37 From the period of Sargon II onwards, both written records and iconographic sources attest to the use of the qersu in ritual contexts as a portable sacred area where purification rites were performed in connection with the king. The qersu probably substituted for all the structures of the temple and temple precinct during ritual activities conducted in non-urban locations (May Reference May, Kogan, Koslova, Loesov and Tishchenko2010: 472), principally during military campaigns, but probably in other contexts as well.

Fig. 23. Drawing of the Type B tableau, Relief 10 (drawing by Elisa Girotto).

In contrast, in the more recent Type A tableau of Panel 5 (Fig. 24) and all other reliefs of this type, the figures of the sovereign and the divine statues are of similar size and the scene is not set under a colonnaded pavilion/qersu.

Fig. 24. Drawing of the Type A tableau, Relief 5 (drawing by Elisa Girotto).

Only parts of the images of the first four deities’ standing on their animals of the Tableau B composition of Panel 10 survive (Fig. 23). Between the figure of the fourth god from the right and the left-hand royal image, there is exactly the right space for three more divine statues standing on animals. We can therefore confidently conclude that, as in Tableau A, a series of seven gods and goddesses on their attributive animals were also depicted in the earlier Tableau B. The difference between the two tableaux lies in Tableau B's smaller size of the divine statues and animals with respect to the two royal figures and the fact that the entire scene is staged under an elaborate columned pavilion.

The visual analysis, examination and recording of all the Faida reliefs is still at an early stage, so the drawings presented here should be considered preliminary, and our reconstruction of the details of the sculpted panels has to be taken with some caution since it may be subject to changes in future, when resumption of work in Faida will allow a more thorough inspection of the reliefs, especially their poorly preserved parts. It does seem, however, that in Tableau B, as it appears in Relief 10, there is a significant difference in the order in which the divine statues appear when compared to Tableau A. In the later reliefs, the goddess Mullissu on the lion is followed by Sîn on the abūbu-deluge monster and Nabû on the mušḫuššu-dragon (Figs. 21 and 24). However, in the earlier Tableau B – which, since Panel 2 is very poorly preserved, is currently known only from Panel 10 (Fig. 23) – the fourth divine figure seems to stand on the back of an abūbu and not a mušḫuššu, since the fourth animal's head does not appear to be that of a dragon but rather that of a horned lion. In the Faida and Maltai reliefs, the only god standing on a striding abūbu is Sîn, since Ashur is represented on a mušḫuššu-dragon and a bull or an abūbu-monster and Adad is shown on an abūbu-monster and a bull. Furthermore, the head of the third animal is not yet entirely clear, but could be that of a dragon. What is certain is that its tail does not have the characteristic wedge-shape of the abūbu tail, but rather the form of a lion's tail (as attested in the lion and mušḫuššu figures). This might suggest that the third animal from the right in the sequence was not an abūbu, but perhaps a mušḫuššu. A more thorough analysis of Panel 10 and perhaps the recovery of other and better-preserved Tableau B specimens along the canal may shed light on this aspect. At this stage of research, however, we limit ourselves to noting the possibility that in the earlier Tableau B, Mullissu was followed by the god of wisdom Nabû on the mušḫuššu-dragon and then by the moon god Sîn on the abūbu-deluge monster. If this holds true, in the earlier version of the scene a sort of godly triad was represented at the beginning of the series of divine statues: Ashur, followed by his consort Mullissu and his son Nabû.Footnote 38 This sequence was then modified in the later Tableau A, where Sîn and then Nabû come after Mullissu. If confirmed by further investigation, this change might reflect some significant theological adjustment of perspective that shaped the Faida sculptural programme.

But what was the meaning of the scene depicted on the Faida canal rock reliefs in the wider context of Assyrian royal ideology and religion? The obsessive replication of the same scene of divine worship by the king in two successive schemes repeatedly carved on at least ten panels along the canal bank can be seen from a broader polysemic perspective. The reliefs were designed to evoke a scene comparable to cultic performances in the temples, where, as attested by letters of the time of Esarhaddon (Cole and Machinist Reference Cole and Machinist1998: nos. 34 and 178: 18–21), statues of the king were set up on the right and left sides of the deity to guarantee his perpetual adoration (Pongratz-Leisten Reference Pongratz-Leisten, Johannes Bach and Finkin press). The veneration scenes carved along the canal course were transported from the secluded temple environment into the open countryside with the aim of commemorating the construction of the new irrigation landscape created by the king in his role as mediator between heaven and earth and promoter of local fertility and abundance (Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi, Düring and Stek2018a: 56, 67–68; Pongratz-Leisten Reference Pongratz-Leisten, Johannes Bach and Finkin press). This is suggested by royal inscriptions, such as the Bavian monumental inscription that celebrates the construction of the Khinis canal of Stage 4 of Sennacherib's irrigation network: “Its (of Nineveh) fields, which had been turned into wastelands due to the lack of water, were woven over with spider webs. Moreover, its people did not know artificial irrigation, but had their eyes turned for rain (and) showers from the sky” (Grayson and Novotny Reference Grayson and Novotny2014: no. 223, 6–7). It is the king who, by command of the god Ashur, creates a new irrigated ruralscape: “Now I, Sennacherib,…thanks to the waters of the canals that I caused to be dug, [I could pl]ant around Nineveh gardens, vines, every type of fruit, […] …, products of every mountain, fruit trees from all over the world, (including) spi[ces] and [olive trees]…I provided irrigation annually for the cultivation of grain and sesame” (ibid. 18b–23a). The rock reliefs with the divine worship scene associated with the canal certified that the king's authority was divinely sanctioned and that he participated together with the gods in the establishment of the cosmic order as an extension of Ashur's agency (Pongratz-Leisten Reference Pongratz-Leisten2015: 414). At the same time, the sculpted panels in Faida, like the impressive rock reliefs in Maltai and Khinis, conveyed a strong ideological and propagandistic message. One aim of this was to foment and cement the loyalty of the people living in the area. As observed above, a large proportion of the local farmers may have been among the deportees of war forcibly resettled in the Assyrian heartland. They very likely formed part of the workforce for the excavation of the canals and later cultivated the land thus made available for intensive irrigation agriculture. These deported communities’ lack of ethnic and cultural connections to Assyria could well have prompted the Assyrian kings to disseminate mighty admonishments of their legitimacy and power throughout the newly created waterscapes in order to ensure the loyalty of all their citizens (Oded Reference Oded1979: 46–48; Ur Reference Ur and Frahm2017: 26).

The chronology of the Faida canal and rock reliefs

Who was the Assyrian ruler who ordered the digging of the Faida and nearby Maltai canals? Did the king who constructed the canals also execute the panels or were the Faida and Maltai sculptural programmes conceived and added to by one or more later ruler(s) after the canals’ construction? Was the carving of the panels along the Faida canal bank – and of the four Maltai panels that are nearly identical to those of Faida – indeed the work of the same king? Was there only one king involved in the carving of the Faida panels, or was more than one ruler responsible, as the succession of Type B and Type A tableaux might suggest? In the absence of written records from Maltai and Faida, no conclusive answer can yet be given to these questions. While it cannot be excluded that the resumption of excavations at Faida after the interruption imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic may lead to the discovery of a cuneiform inscription illuminating all these conundrums, some considerations and a preliminary conclusion can already be proposed.

As has been argued elsewhere, the construction of the Faida and Maltai canals might have been accomplished by Sennacherib's father, Sargon II (Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi and Kühne2018b: 92–94). Here, we will limit ourselves to briefly summarizing the arguments underlying this new dating hypothesis. It is well known that Sennacherib completed the construction of his hydraulic engineering projects in four stages over 15 years, from 703 to c. 688 B.C. The third and fourth stages of the system, which fall within the LoNAP research area (Fig. 3), are described in the so-called Bavian inscription of c. 688 B.C., which was carved in three versions with minor variants in three of the twelve rock steles on the cliff at Khinis (Grayson and Novotny Reference Grayson and Novotny2014: no. 223; on the twelve steles, see Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi2018c). Of the four stages of the hydraulic network, Stage 3, referred to as the Northern System, is definitely the least understood phase of Sennacherib's project (Bagg Reference Bagg2000: 207–211; Reade Reference Reade1978: 157–168; Ur Reference Ur2005: 325–335). Its reconstruction as a coherent and contemporary network of interconnected canals linking together the Maltai, Faida, Bandawai and Uskof canals is an artificial creation of modern scholarly research and has been challenged by new field investigations (Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi and Kühne2018b: 92–94). The LoNAP field survey has shown that the two parallel cross-watershed Maltai canals and the Faida canal were never joined and were not connected to the Bandawai and Uskof canals, as Julian Reade had originally proposed. Reade had suggested that these canals formed a single interconnected irrigation system built by Sennacherib (Reade Reference Reade1978: 157–168 and 2002: 309, fig. 1). Thus, Sennacherib's Northern System would seem to have been a smaller irrigation network than previously posited, limited to the linked Bandawai and Uskof canals flowing into the River Khosr and eventually into the Kisiri Canal of Stage 1. On the other hand, in the region located to the south of the modern city of Duhok there was a series of independent local irrigation channels watering the ruralscape to the south of the Rubar Duhok and east of the Rubar Faida basins, where the major site of Gir-e Pan, probably Assyrian Talmusu, is located.Footnote 39 The Maltai and Faida canals fed an agricultural basin covering about 30 km2, which could be irrigated and intensively cultivated (see Fig. 7) and which was clearly separate from the irrigation basin formed by the Bandawai and Uskof canals.

The new archaeological evidence provided by the LoNAP fieldwork raises questions concerning the layout and chronology of the Northern System's various stretches of canal, and which king(s) commissioned their construction. In the past this has always been ascribed to Sennacherib. This attribution relied upon the close association of the canals with the sculptured rock panels of Maltai and Faida, the Shiru Maliktha relief (Reade Reference Reade, Al-Gailani Werr, Curtis, McMahon, Martin, Oates and Reade2002), and the presence in the same region of Sennacherib's Khinis canal with its reliefs and the aqueduct at Jerwan. Notwithstanding the absence of inscriptions identifying the creators of the reliefs at Maltai, Faida and Shiru Maliktha, all the Northern System reliefs have nevertheless been attributed to Sennacherib in this way. However, the fact that the Maltai and Faida canals are not directly linked to the regional system of the interconnected Bandawai and Uskof canals shows that they were independent infrastructures that might have been constructed before Sennacherib's Northern System. One piece of written evidence might support this reconstruction. A fragmentary letter of the time of SargonFootnote 40 mentions the construction of a large canal by a master-builderFootnote 41 involving the work of a large number of men in the area of Talmusu – probably Gir-e Pan – which, as we have seen, was the major Late Assyrian urban centre in the area and located very close to the Maltai and Faida canals. Taken together, the archaeological and written evidence might suggest a connection between the construction of the large Talmusu canal during Sargon's reign and the Faida or Maltai canals; any of these canals could have originally been designed and excavated by Sargon. However, it should not be forgotten that, although very likely, the identification of Talmusu with Gir-e Pan has not yet been definitely proven.

In sum, both canals were part of a single local irrigation network built to irrigate the eastern Tigris plain to the south of the modern city of Duhok, which could have predated the later larger system of Sennacherib, who might have incorporated into his regional system a local irrigation network built by Sargon. On the other hand, it is also possible that Sargon had already begun excavating the channels of Maltai and Faida with a regional perspective – at least one objective of which must have been supplying water to his new capital at Khorsabad – but that his premature death in 705 B.C. temporarily interrupted his project.

This new dating hypothesis for one or both of the Duhok region canals brings us to the chronology of the related Maltai and Faida carved panels. A number of antiquarian, stylistic, conceptual, and symbolic elements might indeed suggest an early date for them, during the reign of Sargon. Here we briefly review the evidence, referring the reader to Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi and Kühne2018b (94–96, fig. 10) for a more exhaustive discussion. The triple-armed earrings worn by the Maltai and Faida kings and gods are highly distinctive of the periods that precede Sennacherib's reign, in particular the reign of Sargon.Footnote 42 The Maltai and Faida figures wear the simple type of bracelet adorned with rosettes without the lanceolate elements between the rosettes that appear during Sennacherib's reign.Footnote 43 These features, together with the characteristic stylization of the forearm musculature of the gods appearing in Maltai and Faida, might suggest an earlier date for the Maltai and Faida panels. Moreover, all these panels depict an Assyrian ruler in an attitude of worship represented at both the left and right ends of each panel, adoring the statues of seven of the main Assyrian deities standing on podia in the shape of striding animals. With regard to these (as mentioned above), the earliest occurrence of the iconographic scheme of a king followed by a high officer, possibly crown prince Sennacherib, venerating a divine statue standing on a dais appears during Sargon's reign in the famous wall painting of Residence K at Khorsabad. In contrast, the subject represented on Sennacherib's ‘Large Relief’ and sculptured canal head monolith at Khinis (Bachmann Reference Bachmann1927; Bär Reference Bär2006; Morandi Bonacossi Reference Bonacossi2018c; Ornan Reference Ornan, Cheng and Feldman2007; Reade and Anderson Reference Reade and Anderson2013), where Sennacherib is shown in an attitude of worship in front of Ashur and Mullissu, focusses on celebrating the exclusive relationship linking Sennacherib and the two highest deities of the Assyrian pantheon. As Ornan observes (2007: 167), as opposed to the Maltai and Faida panels “the reduced number of major deities here (in Khinis) implies the added importance of the king since his figure is one of only a select few to be represented and, furthermore, displayed in the company of Ashur and Ninlil, the supreme divine pair”. This tableau marks a conceptual and symbolic break in the composition and meaning of the scene of divine veneration by a ruler figure, separating the Maltai and Faida panels from the more personalistic royal programme attested to in Khinis.Footnote 44

On the other hand, it cannot be ignored that relevant iconographic elements on the Maltai and Faida panels suggest that they were carved later, during or even after Sennacherib's reign. The main element is represented by the king's labān appi hand gesture with a cylindrical object held to his nose. As shown by Reade (Reference Reade1977: 33–35), the labān appi gesture with the king holding an enigmatic object to his face, instead of extending and pointing his forefinger as in the ubāna tarāṣu gesture (Magen Reference Magen1986; Shafer Reference Shafer1998: 57–58), is clearly Babylonian in origin (Seidl Reference Seidl1968: 209) and seems to have been introduced to Assyria during the reign of Sennacherib, possibly to signify “the integration of Babylonian and Assyrian kingship, or Ashur's appropriation of many of Marduk's attributes” (Reade Reference Reade1977: 35). The same gesture continues to be seen during Esarhaddon's reign, for example on the Nahr el-Kelb rock-cut stele (Börker-Klähn Reference Börker-Klähn1982: fig. 216) and the Til-Barsip and Zincirli steles (ibid., figs. 217–219).

Another aspect of the iconography of the Maltai and Faida reliefs might be decisive for assessing their late chronology: in all panels, the god Ashur stands on the mušḫuššu-dragon, like Marduk. The transfer of Marduk's theology to Ashur by Sennacherib after his destruction of Babylon in 689 B.C., his reorganization of the cult of Ashur and his temple in Ashur, and the construction of the bīt akītu in the same city (Pongratz-Leisten Reference Pongratz-Leisten1994: 60–64 and 2015: 417–418) might represent a terminus post quem for dating the Faida and Maltai panels depicting Ashur and his son, Nabû, on the mušḫuššu.