Islamic legal discourse in the Islamic Republic of Iran which supports transsexuality and artistic assemblages of transsexual identities onstage and onscreen disrupts western stereotypes about gender identity and performance in public spaces in Iran. Investigating the intersections of transsexual bodies as assembled by jurists in Iranian Shiʿa jurisprudence and by artists on stage and screen reveals the ways in which the transsexual body is constructed in legal discourse and represented in narrative and bodily form in the public imaginary in Iran. Legal discourse embedded in the sovereignty of the state and religious bodies of knowledge, specifically fatwas, has helped create space for the construction of transsexual bodies, subjectivities, and fictional characters in Iran. While certified transsexuals are legally and religiously legible and legitimate in Iran, societal ignorance and intolerance remain a barrier to acceptance and understanding. In the wake of a string of sensationalist documentaries about transsexuality in Iran, Iranian theatre and film artists have crafted groundbreaking trans performances to educate audiences about transsexuality and creatively depict characters living non-heteronormative lives without the translating influence of queer theory or identity politics. In particular, performances of FtM (female-to-male) gender transitions in theatre and film have expanded the boundaries of how gender presentation is translated onto Iranian stages, into Tehran coffeehouses, and onto global screens.

While trans is a legible legal category in Iran according to state, religious, and medical authorities and the historicization of transsexuality in Iran has been well documented, trans activism and creative representations of trans bodies and lives in theatre and film have not been as thoroughly studied or centered. Though trans activism has been instrumental in the attainment of religious and legal protections in post-revolutionary Iran, trans activism “all too often falls out of this story”Footnote 1—so too does trans performance, even though performativity is at the heart of understandings and enactments of the “self” and “gender” in modern Iran. Scholarship on transsexuality in Iran has, until recently, resisted centering trans activismFootnote 2 save for the obligatory references to Maryam Molkārā’s groundbreaking efforts to ask Ayatollah Khomeini for formal recognition and permission to live as a woman instead of her assigned male gender at birth.

Post-revolutionary trans activism has benefitted from a variety of media platforms, such as the internet and documentaries. As Najmabadi observes, “the explosion of transsexuality into the printed and electronic media was significant in multiple ways for the emergence of a more visible group of trans activists,”Footnote 3 and trans activists and journalists alike criticized governmental bodies for neglecting this socially vulnerable population. However, little research has been done on how the media in Iran has affected public perceptions of transsexuality and how media may help in the formation of self-cognition for viewers who may identify as trans after viewing such programming. While trans activism “forms a part of the process of state-formation itself”,Footnote 4 it also aids in the formation of society’s knowledge about transsexuality and in the assemblage of trans people’s self-recognition, self-understanding, and self-cognition.

Gender transitions depicted in Iranian theatre and film feature trans subjectivities that have not been shaped by identity politics, queer activism, or critical theory. Trans activism in Iran, in contrast to the West, has not been influenced by or grounded in identity politics, rights discourse,Footnote 5 or queer theory; rather, transsexual activists have lobbied for “needs” as opposed to “rights.” Trans activists tend to focus on “welfare, justice, and vulnerability”Footnote 6 as opposed to “rights” for a particular fixed “identity” in their uncoordinated attempts to appeal to the Office of the President, the Office of the Supreme Leader, and occasionally the Majles.Footnote 7 Despite official legal and religious recognition, trans activists are still fighting for their full needs to be met, specifically better access to health care,Footnote 8 improvement in the quality of surgery provided, and greater public and medical education about transsexuality.

The development of how transsexuals are treated and represented today in legal discourse in the Islamic Republic of Iran is directly linked to local and historical processes and phases of modernization in Iran that set the terms and boundaries of gender, sexuality, and the soul in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century. Throughout its history, as Afsaneh Najmabadi has shown in her extensive scholarship on the subject, Persian culture has embraced gender androgyny and other activities and lifestyles that evaded or transcended male/female and hetero/homosexual binaries.Footnote 9 Contrary to Sunni jurisprudence,Footnote 10 Shiʿa jurisprudence in Iran does not view sexual reassignment surgery (SRS) as a manipulation of the work of God. Notions in Shiʿa jurisprudence such as the mutability of the body, the relationship between the body and soul, and the concept of the self’s authenticity have largely been shaped by an understanding of the body and its constructedness which is distinct from Sunni conceptions of the immutability of the body.Footnote 11 Ayatollah Khomeini and other jurists in Iran have supported transsexual surgery on the grounds that it is not explicitly banned in the Qur’an and re-gendering the body does not change the soul or transgress the work and authority of the Creator. In the short film Legacy of the Imam, the cleric Mohammad-Mahdi Kariminiā explains that transsexuality is permissible because it is not explicitly prohibited in the Quran or in the basic tenets of fiqh. In his work, he has also stressed the provision of iztirār—in this case, the “circumstantial necessity to prevent suicide.”Footnote 12 Correcting one’s sex is viewed as less harmful than committing suicide as a result of a mismatch of body and soul.

As far back as the early 1960s, Ayatollah Khomeini wrote that there was no religious prohibition on corrective surgery for intersexuals, as no religious verse banned it.Footnote 13 Ayatollah Khomeini also published a fatwa permitting sex change for transgendered people as early as 1967 while exiled in Iraq.Footnote 14 While two dozen surgical sex changes in Iran were performed in 1976 under the shah, the Medical Association of Iran (MAI) decided in that same year to allow surgery only for intersexuals and not transsexuals based on so-called ethical grounds. This ruling was not reversed until a decade later by Ayatollah Khomeini after the Iranian revolution. Due to his judicial acceptance of transsexuality and SRS, transsexuality is openly discussed in seminaries in Qom, the center of jurisprudential study and fatwa production in Iran.

Ayatollah Khomeini’s main fatwa on the matter was issued in response to requests by Maryam Khātun Molkārā (MtF), who wrote to Ayatollah Khomeini for guidance when Khomeini was in exile in Iraq. In the mid-1970s, Maryam was living under her male birth name Fereydun. In 1975, she asked Ayatollah Khomeini for religious permission to have sexual reassignment surgery. According to her, “I wrote that my mother had told me that even at the age of two, she had found me in front of the mirror putting chalk on my face the same way a woman puts on her make-up. He wrote back, saying that I should follow the Islamic obligations of being a woman.”Footnote 15 Thus, “the originating impetus for current religiously sanctioned medico-legal transition procedures”Footnote 16 was trans activism by this one individual whose efforts for recognition continued through the decades.Footnote 17 After the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the situation for transsexuals improved due to Ayatollah Khomeini’s stance on the matter and more legal recognition was given.Footnote 18 When Ayatollah Khomeini reissued his 1967 fatwa (which was originally written in Arabic) in Tahrir al-wasilah Footnote 19 in 1985 (this time in Persian), he enshrined state-sanctioned medico-legal procedures for transsexuality.

When Molkārā met with Ayatollah Khomeini in 1987, Molkārā left the house with a fatwa for sexual reassignment surgery. Thus, this fatwa “was obtained by trans-persons’ demand put on Iran’s supreme politico-religious authority.”Footnote 20 As a result, the Ministry of Justice declared SRS to be legal on 9 October 1987 for both intersexuals and transsexuals. Centered on a distinct split between the physical body and the soul, trans discourse in Iran argues that most people experience harmony between the two, but transgendered individuals suffer from a correctable mismatch. Notably, one does not have to take hormones or have surgery to be certified and accepted as a “transsexual” in religious and legal terms in Iran. Somatic changes do not determine one’s legal legibility or legitimacy. However, to be legally recognized as transgender, one must change their birth certificate and passport. Though a number of Iranian religious jurists today support SRS, the general public is generally not as tolerant or supportive of transgender and transsexual individuals; furthermore, more recent fatwas have tried to place limits on the permissibility of transsexuality with regard to surgery.

A discourse of functionality and authenticity has emerged in more recent fatwas on transsexuality. For instance, in 2010, Ayatollah Nāser Makārem Shirazi specified that new sexual organs must “work” for a sex change operation to be permissible.Footnote 21 The question posed to him on his website was about those who are homosexual, but who wish to undergo SRS to avoid suicide.Footnote 22 His response: “Sex change has two forms: it may be a mere formality that although it makes the opposite sexual organ appears, the organ does not really work. This is not allowed. But if the sex change is real and the real sex organ appears, this is allowed by Islamic law.” In his answer, Makārem Shirazi notes that the surgery cannot be done cosmetically to “pass” as transsexual. He notes that “sex change is not inherently against Islamic law and it is allowed.” This emphasis on utility, performativity, and functionality somewhat limits Khomeini’s original fatwa by narrowing the criteria for eligibility and legibility. Similarly, Grand Ayatollah Hossein-Ali Montazeri maintained that SRS is allowed “unless it involves a sinful act”Footnote 23—code, of course, for homosexuality. Nevertheless, as Najmabadi has pointed out, “the religio-legal framework of transsexuality has been productive of paradoxical and certainly unintended effects that at times benefit homosexuals.”Footnote 24 It should be noted that a number of Ayatollah Khomeini and Ayatollah Khamenei’s original fatwas such as on transsexuality and IVF have been considered too permissible by later jurists in Iran and Iraq who have placed more limits on their original opinions.

For decades, the Iranian government has extended financial assistance to those seeking hormonal and surgical interventions through charity foundations and insurance companies. While the Imam Khomeini Charity Foundation has long offered loans to help pay for SRS, the economics of transitioning are not that simple and some transgendered Iranians have expressed concern regarding the quality of surgery available. As trans (FtM) theatre and film artist Saman Arastou notes:

Men and women can be placed on a spectrum and we are born transgender on this spectrum. We can move up and down this range [of gender] with surgical procedures, if they are carried out properly, towards being a man or a woman. I say properly because there are surgeons in Iran who cut nerves that shouldn’t be cut, and this becomes problematic. We don’t have enough surgeons for this precise procedure in Iran. It is also very expensive.Footnote 25

There are, of course, other legal and bureaucratic hurdles which make transitioning difficult even though it is legally and religiously sanctioned.

While identity cards and birth certificates can be legally changed, the slow bureaucracy of doing so can create other related problems. As Arastou recounts, “It took me a year to get a new identity card after my gender reassignment surgery. Because I only had an ID that identified me as female, I ended up having to wear women’s clothes despite my operation. People made fun of me.”Footnote 26 Further, when a man applies for a job in Iran, he has to show that he completed his mandatory military service or produce official documents proving an exemption; this requirement often creates problems for transmen. Arastou further explains:

Transgender people are exempted from military service but, often, the army doesn’t know what to write on the forms. So some transgender people end up with things like “mental health issues” or “hormone imbalance” written on their files, which can cause them problems when they are seeking employment.Footnote 27

While transsexuals are supported by state laws and religious legal discourse, such acceptance and tolerance are not generally found in society at large.

The challenges faced by trans people come primarily from social and cultural norms. Many Iranians are ignorant of these permissive laws and fatwas, and equate transsexuality with homosexuality and bisexuality. Such misconceptions have been confronted in the theatre works of Arastou, who notes, “In my 42 years of life, I have heard people say a transgender [person] is a disaster of nature time and again. This is a common view … Instead of taking their children to a psychologist, most families throw them out … and people also face them with ignorance.”Footnote 28 The fact that Iranian clerics are more accepting of transsexuality than the general public disrupts western, Orientalist notions of Islam and theocracy. However, in the past several years, Iranian theatre and film artists have begun to challenge the narrow-minded views of society by featuring characters and even actors who are transgender on stage and on screen. Not only do biotechnology and state powers combine to assemble “suitable” bodies embedded in social and historical processes, but they also allow for the creation of non-conforming artistic bodies that can be read as “queer” in the western, theoretical sense of the word. These new artistic assemblages are being created by directors largely out of a desire to educate the public about transsexual identities, realities, and lives. As a result, these transsexual characters on stage and screen are broadening representations of gender in the performing and cinematic arts in Iran.

Female-to-male trans characters are more prevalent in Iranian theatre and film due to the fact that MtF trans people in Iran are often misread as homosexuals, and thus the social stigma towards them is greater than towards FtM trans people. As Najmabadi observes, “female trans/homosexuality was always been incidental,” as it is “perceived as less threatening to the larger legal-religious-cultural order of things” and “assumed to be a problem of a more marginal and numerically smaller scale.”Footnote 29 It is significant that the trans protagonists of the two award-winning feature films from Iran that discuss transsexuality (Facing Mirrors and Cold Breath) are FtM characters not MtF characters. Saman Arastou notes: “Yes, unfortunately in a patriarchal society like Iran, FtM transsexuals are more accepted than MtF transsexuals.”Footnote 30 As a result, significantly more dramatic and cinematic space has been carved out for FtM characters than MtF characters in Iran, as FtM gender performance is perceived as less transgressive and is thus less stigmatized.

Performing Trans: Enacting Gender in the Everyday and Art

The performative underpinnings of gender presentation in Iran lend themselves to artistic performances, reproductions, and representations in theatre and film. Performativity is, in a sense, at the heart of understandings of the “self” and “gender” in modern Iran. As Najmabadi notes, the “sense of self that informs modern subjectivities in today’s Iran, in many registers, is defined largely, though not hegemonically, by notions of conduct.”Footnote 31 In his work (Eʿlm al-nafs yā ravānshenāsi), Ali-Akbar Siāsi, whose views continue to inform understandings of the “self” in Iran, employed the language of performance to explain the psyche, suggesting that the “psyche is like someone who is both a singer and an audience, an actor and a spectator.”Footnote 32 Najmabadi maintains that gender in modern Iran is a “sense of being in the world that is centered on conduct—the situated, contingent, daily performances that depend not only on any sense of some essence about one’s body and psyche.”Footnote 33 For a number of historical reasons, which Najmabadi charts in her book, “normative gender/sex expectations have become formed around conduct rather than identities.”Footnote 34 Whereas understandings of gender in the West are currently preoccupied with bodily interventions, somatic changes, and the cultural genital imperative, gender assemblages in Iran are based more on conduct, performance, and lifestyles. As a result, notions of transsexuality in modern Iran have not been formed in relation to identity politics and profitable medicalization as in the West.

Documentaries like Just a Woman by documentary filmmaker Mitra Farahani (which garnered international attention at the 2002 Berlin Gay and Lesbian Film Festival) and others like it put a spotlight on transsexuals in Iran for audiences at home and abroad,Footnote 35 beginning in the first years of the new millennium. The increased media attention to transsexuality had an effect on journalistic discourse on the matter. For instance, in November 2003, Rayhaneh Qasim Rashidi, a column editor for the magazine Rāh-e zendegi argued against SRS and warned trans people against surgery, believing that being trans is akin to heart or kidney disease but in the soul or psyche; thus, the disease should be treated with therapy not surgery. However, over the next few years, thanks to a proliferation of documentaries, blogs, and other trans-run websites, the media tone in Iran towards trans people shifted to one that was more supportive and accepting. Some of the first documentaries on this topic include those by Sharareh Attari (2005), Zohreh Shayesteh (2005), Kouross Esmaeli (2006), Negin Kianfar and Daisy Mohr (2006), Tanaz-Eshaghian (2007), and Bahman Mo’tamedian (2008). Mohammad Ahmadi's short film Nature’s Humor (2006) was informed by several years of extensive research and explicitly crafted to promote social change. More recently, Bahman Moʿtamediān garnered attention at the Venice Film Festival for his part-fiction part-documentary film Sex My Life (2008).

Perhaps the most far-reaching documentary was Tanaz Eshaghian’s 2008 documentary Be Like Others which was broadcast by BBC2 with the title Transsexual in Iran. The edited version that was screened by the BBC was intensely problematic, as it framed transsexuality as a cure for homosexuality and “techniques such as directed questions, selective translation, lack of contextualization and the use of stereo-typical images” all served the “purpose of manipulation of the film’s message.”Footnote 36 Another critique from within the trans community has been that documentaries have turned them into objects of pity and scorn due to their sensationalist tone, focus on the negative, and misguided assumptions.

In the wake of Just a Woman, a number of articles began to appear in western media outlets like The Guardian, Independent,Footnote 37 and New York Times, and television documentaries on transsexuality in Iran began to appear in Sweden, France, Holland, and the United Kingdom.Footnote 38 Rooted in Orientalist assumptions and reductive understandings of Islam, these foreign documentaries tend to be marked by a tone of shock and self-congratulation in “discovering” and “outing” this so-called “queer” and “oppressed” minority in Iran. Even though these “othered” bodies—i.e. intersexual and transsexual bodies—have been present in the Iranian press for several decades and in Islamic legal discourse for many centuries, western media outlets tend to portray transsexuality in Iran as an entirely new phenomenon and incorrectly assume that SRS is being used in coercive ways to “cure” homosexuality.

The dramatic and cinematic arts are creative realms within which trans identities can be safely expressed and performed in the public sphere – in theatres, coffeehouses, and cinemas – to raise awareness about transsexual lives in Iran and expand representations of trans bodies in the public imagination. The arts have become a prime stage for trans bodies in the public realm to explore how gender and “selves are professed and performed proficiently.”Footnote 39 With the emergence of several notable theatrical and cinematic productions that center FtM lives, both real and imagined, gender transitions in the dramatic and cinematic arts have served as prime gestures of pathos, desire, and activism not usually evident in gender normative performances where born females must subscribe to restrained displays of emotion, affect, and decorum in heteronormative narratives. Trans theatre artists and activists like Arastou are acutely aware that “self-cognition, along with its more public recitation—that is, its narrative and bodily presentations”Footnote 40 is what makes a transsexual recognized by others. As Arastou explains:

In my performances, audiences are not just the audience, they should live with us in the moments. Also actors aren’t just actors. Sometimes, as an artistic team, we watch audiences. Even they can change the final [version] of my performances and determine the duration of a bitter dream. They have permission to change their life. Can I find these wonderful experiences in cinema?Footnote 41

Recognition comes through narrative and bodily representations; thus the audience is invited to participate in recognition of trans subjectivities while the theatre artist is in turn transformed through the process of self-narrativization and self-understanding.

Assembling Trans Bodies on Stage: Theatrical Performances of Transsexuality in Tehran

While transsexuality is sanctioned by the religious authorities and state, transsexuals until recently have rarely been depicted in Iran’s cultural, literary, and cinematic landscapes. Over the past decade, however, fictional transsexual bodies have been assembled and transgender actors represented on the stages of Tehran (Figure 1) and in the diaspora. For instance, a performance about SRS entitled Pinkish Blue (the literal translation of title: “Pink Inclined to the Blue”), was staged in January 2018 at the Paliz Theater for the 36th Fajr International Theater Festival in Tehran by a cast of nine actors (Figure 2). The play was directed by Sanaz Bayan, who became familiar with this issue thanks to an article her journalist mother wrote in the 1990s; thus, the genesis for this theatrical work was the media. Bayan is known for crafting daring work based on sensitive social issues.Footnote 42 In an interview with Mehr Agency, Bayan noted that the play is a well-researched social drama:

My recent play (Pinkish Blue) fits mostly in the category of social drama, but it is informed by extensive research … I cannot call it a documentary, as it is more of a research-oriented social drama.

Figure 1. Iranian actor Behnam Sharafi performs in Pinkish Blue by Sanaz Bayan.

Source: AP Photo/Vahid Salemi.

Figure 2. Cast of Pinkish Blue directed by Sanaz Bayan.

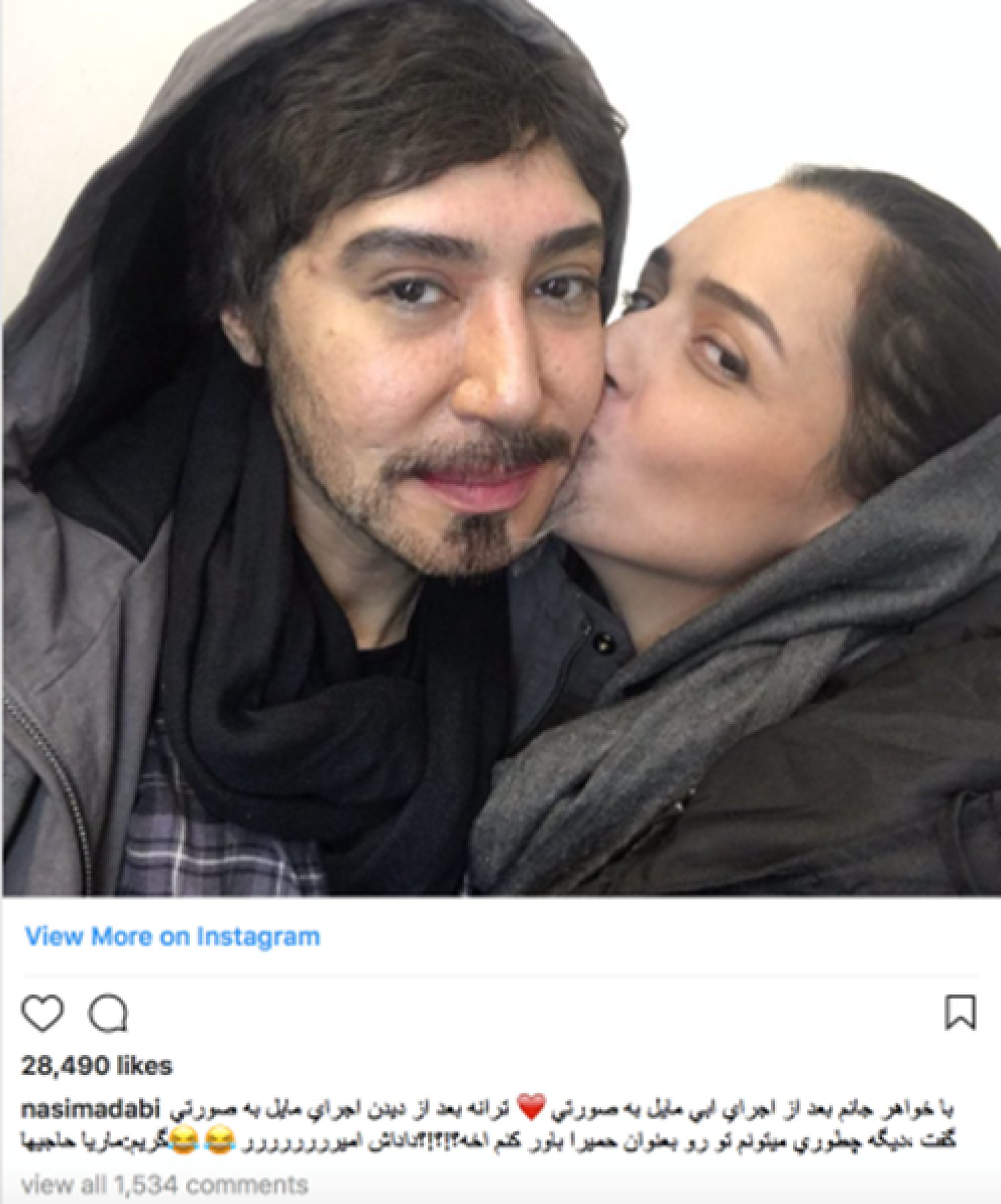

Posters for the play advised that it was not appropriate for individuals under sixteen years of age. Bayan’s synopsis for the play reads: “The words of man and woman are nothing but illusions. No man is completely a man and no woman is completely a woman, otherwise we all would turn into monsters.” This formulation of the issue places gender on a spectrum; the continuum is centered instead of “identity” or the gender binary (Figure 3). According to Bayan, “Talking about the trans issue is a cultural taboo,”Footnote 43 and a number of actors rejected invitations to participate in the project because they did not want to be branded with stigma or shame for being a part of it.” However, the play still featured well-known actors,Footnote 44 such as Nasim Adabi, who is known for her portrayal of Homeyrā, the sister of Shahrzad in the popular series Shahrzad. In this production, she played the part of a transman (FtM), Amir, with the help of make-up artist Maria Hājihā. Adabi published her photo of herself dressed as Amir on Instagram along with Tarāneh Alidousti (Figure 4). In fact, the Health Minister Hassan Qāzizadeh-Hāshemi attended the play and commended it for raising people’s awareness about transgender issues.

Figure 3. Pinkish Blue directed by Sanaz Bayan.

Figure 4. Nasim Adabi as Amir in Pinkish Blue.

Stepping Center-Stage for Social Change: Trans-Autobiography and Performance Art

No theatre artist has done more to push the boundaries of trans bodies and narratives on stage in Iran than Saman Arastou, a transgender (FtM) actor, director, playwright, performance artist, and theatre instructor, who has been active in the theatre and film scene in Tehran for more than three decades (Figure 5).Footnote 45 Even before his transition, Arastou was pushing the boundaries of gender representation in theatre and film. In the 2004 film The Command, directed by Masoud Kimiai, Arastou played the role of a bodyguard, a role that no woman had played in Iran before. Almost all of the film roles offered to him were written as if they were written for a man. At that time, he became a well-known actor in Iran’s cinema and television, and in theatre he staged successful plays as well. Arastou had sexual reassignment surgery in 2008 when he was forty-one years old; he also changed his name from Farzaneh to the male name Saman. Arastou believes that if artists are seeking truth, trying to raise awareness, and not being motivated by profit and fame, then artistic projects in both theatre and film can influence society; nevertheless, he believes that theatre has a distinct advantage. He explains: “theatre always can be more effective, because it involves the five senses of the audiences in the moment. And it shows bitter realities in front of their eyes. That’s why I don’t have a ‘Fourth Wall’ in my performances.”Footnote 46 In the past several years, he has penned and performed several plays about transsexuality in Iran and also put together small, informal performances about transgender issues in cafes across Tehran.

Figure 5. Saman Arastou in You All Know Me (Photo credit: Phillipo Menci).

In 2014, Arastou wrote the autobiographical play You All Know Me (Figure 6), which was the first play in Iranian theatre history to address the situation of transsexuals in Iran. The play highlights the difficulties of life both before and after SRS. In the play, Arastou centers transgender embodiment, exploring his life in both a pre-op female body and a post-op male body. For instance, after SRS, he was excluded from all cinema, television, and even theatrical projects due to stigma against transsexuals in the arts. However, he continued to pursue his own theatrical projects and dedicated himself to his own productions more than ever before. The play was originally conceived of as a monologue; however, after holding a number of acting workshops, he decided to select a number of his students to be in the play. He recounts:

It was really difficult and took a long time to get the permission from the government to perform it. After our public show, many directors used the story of transsexuals in their performances and films. But they only made a type, not a character. This caused society to pity transsexuals and put all of them in a same group, while all of us have unique characters with our own story.Footnote 47

After eight months of rehearsal, he and his students staged the play in 2015 at Fanous Theatre in Tehran where it ran for ninety nights.

Figure 6. You All Know Me by Saman Arastou (photo credit: Phillipo Menci).

The play invites audience participation; for instance, he invited families of transgendered individuals onstage to ask them to continue to raise awareness about transgender issues. Due to very favorable media coverage by Iranian news agencies, the play was performed for an additional thirty nights and then for two weeks at the City Theatre of Tehran, the most prominent theatre venue in Iran. In 2016, it was performed in the first international Iran-France performance festival in Tehran, and it was selected as the top performance out of the 100 shows produced in the festival. It was also chosen by the Goethe Institute to be produced as a theatrical work representative of Asian theatre (as a prime example of Iranian modernity), and it also performed in Paris in 2016.Footnote 48 Thus, this transgender-centered play has been shared on stages in both Iran and Europe, dismantling stereotypes at home and abroad.

Arastou believes that theatre can and should be used to raise awareness on social issues. He has cited Antonin Artaud and Augusto Boal as influences, and notes on his website that Be Who You’re Not was inspired by the Theatre of the Oppressed.Footnote 49 According to Arastou, Brecht’s plays and methods have also provided inspiration for all of his performances (Figure 7). Other influences include Paolo Pasolini, Michael Haneke, Bergman, and the realism of the Almodovar films.Footnote 50 For Arastou, theatre fills an absence in media discourse: “We have no media here to raise awareness on the physical and mental issues faced in such a situation but the theater.”Footnote 51 He notes that the situation in Iran is much better than it used to be, as “people are more aware of their situation and there are fewer odd looks.” One obstacle, however, is that there are “transgender translators, solicitors, and doctors in Iran who are too afraid of revealing their true selves. If they do so, society will also accept them.”Footnote 52 Theatre, however, allows for transgender narratives and voices to be witnessed and heard in order to encourage minds to open and change. According to Arastou, “There were many families who didn’t accept transsexuality and knew it as a disease but after watching the performance they told me, now we want to come on the stage and share our awareness with others.”Footnote 53 In this sense, it is theatre that is the medium that effectively gets the “message” out on transsexuality to the public, not the religious fatwas that permit it. Arastou is now creating a new video project about the role of the media in increasing awareness about transsexuality.

Figure 7. Saman Arastou in Be Who You're Not (Photo credit: Babak Haghi).

Arastou has faced obstacles in producing his bold and honest depictions of trans life in Iran due to the constraints of censorship. However, while censorship can be a barrier to creative expression, it can also be a portal to creativity. Arastou explains, “I use the obstacles and welcome them because they make challenges, then you must improve your creativity and be stronger … I learned the rules of their game after over 30 years.”Footnote 54 He does not feel that censorship breeds compromise; instead he embraces it for its creative potential. He argues: “you can make your choice, you will limit yourself and kill the reality and lose the truth or you improve your creative power for showing the reality.”Footnote 55 In his plays, Arastou also boldly critiques the state-regulated legal process of “filtering” that transsexuals must go through to be officially “certified” and legally recognized as transsexual. In particular, he critiques ignorance among professional psychologists and the frustrations of the medicalized bureaucracy, such as in the following scene from You All Know Me:

Psychologists: Tell me your problem.

FtM: We do not have any problems at all!

We’re not ill!

Look, this is a simple social definition

That is, we have two definitions for this

One is sex. The body we are born with

That is, the structure of our body

The other is gender.

The definition that society presumes for a woman or a man, is not compatible to the body I was born with!

My body is female

But my identity and everything that I have in my head is male.

I’m a male. I cannot stand this body any longer.

I have to go and change it.

I have to adapt to what I am.

Psychologist: We’ve not been informed about this new science you speak of.

We would offer it to her as soon as we were properly notified.

Arastou uses his plays to both educate the public and push for social change in the medical profession and governmental bureaucratic bodies and processes.

Arastou staged a play entitled The Idle Self-Employed with a completely transgender cast to complete his transgender trilogy (the other plays are Everyone Knows Me and Be Who You're Not).Footnote 56 Unlike films like Facing Mirrors and Cold Breath (profiled in the next section), Arastou’s theatrical projects incorporate real transmen and transwomen, putting forth their “authentic” trans bodies for public consumption and awareness in Tehran. His play Be Who You're Not,Footnote 57 an interactive theatre piece staged at the 36th Fadjr International Theater Festival in Iran (which has been performed eighty times on stage and a dozen times in cafes around Tehran), pulls heavily from Arastou’s own life and pain (Figure 8).Footnote 58 Arastou took three years to develop the piece. Specifically, the play features his “forced marriage” and he considers the piece a “resistance performance” (Figure 9). He explains: “Sixteen years before my SRS, I was forced to marry a man. Many audiences of Be Who You're Not came to the scene [onstage] and changed the final [scene] of my wedding night. They didn’t allow this marriage and saved me. It was the biggest victory for me and the next victims of unawareness.”Footnote 59 Like much of Arastou’s work, the play continued to evolve and transform as it was performed in different venues.Footnote 60

Figure 8. Saman Arastou in Be Who You’re Not (Photo credit: Amir Moa'yad Bavand).

Figure 9. Saman Arastou in Be Who You're Not (Photo credit: Babak Haghi).

Arastou’s 2018 play You Can Be Auto Footnote 61 is based on his experiences of trying to obtain permission from a psychologist and the government to get SRS. The play was inspired by drama therapy and the Theatre of the Oppressed, and it highlights the ignorance of psychologists, government officials, and society regarding trans issues in the 1990s and even today. The play touches upon violence against trans people, shock therapy (ECT) given to “fix” transsexuality, and the complex bureaucracy around SRS—such as when Arastou could not access his salary at the bank for a year because it took so long to make his new ID card. The dialogue is all derived from the words and memories of trans people in support groups, and real trans people are included in the play to share their personal experiences. The play also incorporates contemporary dance and mime techniques to convey its message. He explains:

I use contemporary dance and mime techniques in Be Who You Are Not and You Can Be Auto Footnote 62 because I think dance is a global language. If they want to close our mouths, we speak with our bodies. Audiences can make their own story when they see a dance piece and they can use their own thoughts. They can imagine rape, laughter, violence and any other feeling inside them. In this way, they make their own story … so they will never forget the story which they made in their internal worlds.Footnote 63

Arastou takes full advantage of the holistic nature of the theatre to provoke the audience to engage with the material not just through words but also through the observation and interpretation of movement and the body (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Saman Arastou in He is Not a Thief.

In You All Know Me, You Can Be Auto, and other performances, Arastou has crafted characters who are in straight and homosexual relationships. Arastou notes:

The FtM person in You All Know Me has a monologue about his partnership with women before surgery. Or there is an MtF who shares a story about her military service when a soldier raped her. Or she speaks about a guy who fell in love with her. It was never taboo for me to show the reality and use real stories and real characters in my plays.Footnote 64

However, in the films profiled in the following sections, the trans protagonists are not engaged in any romantic or sexual relationships. Further, Arastou includes MtF characters in his plays, which no Iranian film has yet dared to do (Figure 11). In one such scene in You All Know Me, when a brother of a transwoman (MtF) tells his father that his brother says he is a woman, the father responds:

Haji (Father): Oh, God have mercy on us … There is no god except Allah.

You go buy two plane tickets for the holy Mashhad,

I’ll pray for him.

You’ll either get cured,

Or stay there

Till you die.

Till you rot.

Get lost!!

I'll burn you!

God have mercy.

Figure 11. Autopsy performed at City Theater of Tehran.

Arastou confronts the roots of familial conflict regarding transsexuality, including religious beliefs, to educate audiences about societal ignorance and family attempts to cure trans family members through prayer, pilgrimage, and marriage. His latest production, Autopsy, is about women who have married (MtF) transsexuals. As Arastou explains: “Because of the unawareness of themselves, of psychologists, and of their family, they [MtF transwomen] marry. They think can forget their feelings this way, but after a few months they understand they will never change and when they tell that to their partner, the partner says: so who I am? What is my gender? And many other questions.”Footnote 65 The new performance piece focuses on the wives of these closeted transwomen whom Arastou sees as “victims” of societal ignorance.

Arastou has seen first-hand how his drama workshops and performances transform and enhance transsexual self-cognition. Mining his own FtM experiences for artistic fuel on the stage and in workshops with other transsexuals through the narrativizing self helps him to understand and explore his own sense of being in the world. Arastou observes:

We grow in the performances together. There were many transsexuals who were scared about being seen. Because society tries to hide them. But we helped them to rise and live their real character. After five years in our “Self-Cognition Workshop” they increased their confidence and succeeded to introduce themselves on the stage, without a mask.Footnote 66

Thus, his performances are as much about self-cognition and empowerment as they are about changing societal consciousness about transsexuality.

Another crucial difference between documentaries and theatricalized trans performances is that the latter put demands on the audience. Much of Arastou’s work invites audience participation; whether or not they choose to participate, however, is up to them. In the 2017 performance of Be What You Are Not at the Schaubühne Studio, Arastou handed a bandage to a member of the audience and took the other end to bind his own chest before being slapped and knocked to the ground by a cis-heterosexual man–who, to the audience, could have been an actor or fellow audience member. During one performance of the play, a blond woman from the audience at this point interjected herself and said, “No, I don’t like it,” as the man removed his belt to strike Arastou. Such audience participation was of course welcome; however, the other spectators were unable to determine who was part of the show and who was not.Footnote 67 In another performance of the play in a cafe, the performance began as if it was just a straight play, but then Arastou ran into the cafe screaming that he was running away from his brother who was trying to force him to marry a man. An actor portraying his brother stormed in and began hitting him, along with actresses portraying his sisters, who then tried to force him into a wedding dress and make-up. His favorite reaction was when, as he recalls, “twenty audience members stormed the stage and ripped off my wedding dress to keep the forced marriage from taking place.”Footnote 68 Creating room for audience participation in such dramatic, realistic scenes forces the audience to contemplate their own positionality; further, they are provided with a space within which they can rehearse or practice making interventions in real life.

Arastou’s impromptu performances in cafes around Tehran have also made transgender bodies visible in public spaces through the act of theatre. In one such scene, a video of which appears online,Footnote 69 Arastou sits in a chair while three women in black hijabs and white gloves hold him down to try and force a hijab on him and floss his teeth while he struggles to get free. Despite his attempts to fight back, they manage to put him in a hijab. When he reaches out his hands for help to the people watching in the cafe, no one helps him.Footnote 70 These cafe performances blend documentary and fiction; they give voice to the transgender experience and make transgender/transsexual bodies a site of resistance and spectacle in public space (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Saman Arastou in the Schaubühne Berlin Theatre Festival.

Iranian theatre artists in the diaspora have also drawn inspiration from the subject of transsexuality and attempted to explore it onstage. For example, transsexuality in Iran was the subject of Plastic, a play written by Mehrdad Seyf which was produced by 30 Bird Production at the 2008 Edinburgh Fringe Festival. The play, a dark comedy, may also be considered performance art, due to its non-linear structure and imagistic content. At the start of the play, the audience was segregated according to sex and greeted by actors dressed in white as if for surgery in the hall. To allude to sexual organs being removed, pickles and stiletto heels were displayed in pickle jars on the stage. An actor asked: “Will it hurt?” A woman had her bare chest wrapped in bandages. The piece, according to Seyf, was not intended to be received or interpreted as a journalistic piece, an attempt to tell a story, or social analysis. On the contrary, the “aim was to see how we can explore this reality between being a man and being a woman without going into any clichés whatsoever—which is not an easy thing to do … we leave the interpretation to them rather than tell them what it’s about.”Footnote 71 Whereas the explicit aim of Arastou’s theatrical work and the Pinkish Blue has been to educate audiences about trans issues in Iran, Seyf’s performance piece relies on symbolism to play with the theme of transsexuality without narrative, character, or resolution.

Facing Mirrors: Representing Transsexuality Onscreen

Films do what guerilla theatre in Tehran cannot—transmit narratives of transsexuality and embodied performances of gender non-conformity to Iranians in cities and villages outside of Tehran. Films have a greater reach than theatre due to both cinematic viewership and online distribution; thus, they have more power and potential to educate the public. Trans representations in theatre and film facilitate self-cognition, self-education, and self-de-stigmatization. Facing Mirrors (2011), the first Iranian feature film to feature a female-to-male transgender protagonist that was written, produced, and screened in Iran, carved out new cinematic space for trans representation and unconventional, non-heteronormative friendships (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Shayesteh Irani in Facing Mirrors.

The film was notably spearheaded by an all-female creative team. It was directed by Negar Azarbayjani, produced by Fereshteh Taerpour, and co-written by Helmer Azarbayjani. Before making the film, Taerpour said she did not know Ayatollah Khomeini’s permissive fatwa existed: “At the beginning, it was very strange for me to find out that sex-change operation is permitted in Iran. The authorities give loans and even issue new ID cards after the surgery, something that is not legal in many countries.”Footnote 72 To make this groundbreaking film, they assembled a highly accomplished cast, including Shayesteh Irani (who appeared in Offside by Jafar Panahi), Saber Abar (who appeared in About Elly by Asghar Farhadi), and legend Homayoun Eshradi (who starred in Taste of Cherry by Abbas Kiarostami). The film was inspired by a male-to-female transsexual who lived in the director’s neighborhood who was forced to move after transitioning due to societal ignorance and misconceptions. The director’s vivid memory of how painful that experience was for her neighbor and the intolerance of her immediate communityFootnote 73 informed the dramatic events in the film. Nevertheless, it is significant that in the film she featured an FtM character, even though the film was inspired by an MtF transwoman

The film is centered around the unlikely friendship between upper-class Adineh (who goes by the male name “Eddie”), a pre-op transman in Tehran, and Rana (Qazāl Shākeri), a devout, working class woman who secretly drives a taxi to pay off her imprisoned husband’s debts acquired as a result of the dubious business practices of his partner. Eddie then offers Rana one million tumāns to take him to Kojoor in northern Iran to avoid being forced to marry a cousin by his abusive and controlling father. Rana is overcome with shock and disgust when she catches Eddie using the male restroom at a rest-stop (Figure 14). Eddie begins to explain that his true gender is male, and he has been taking hormones to get SRS abroad; these plans are being thwarted by his father who wants to “cure” Eddie’s “affliction” through marriage. In one scene, Eddie’s father complains to her brother that being transgender is “her” latest way to embarrass him, but, “Once she gets married, she'll come to her senses.” After the brother refers to Ādineh as Eddie, their father screams back: “Never call your sister ‘Eddie’ again, you stupid [idiot]!” Eddie’s father refuses to acknowledge anything about Eddie’s transgender identity. Societal intolerance towards transsexuals is on full display when Eddie’s father declares: “I wish she was blind, dead, handicapped, but not disgraced.” In this hierarchy of shame, transsexuality is ranked lower than disability. The father also physically abuses Eddie to punish him for his gender and plans for SRS abroad.

Figure 14. Qazal Shakeri and Shayesteh Irani in Facing Mirrors.

In Rana’s attempt to get away from Eddie, she is injured and Eddie offers to help her to heal. Though Rana befriends Eddie in her convalescence, she is still invested in enforcing gender normativity in her own home (Figure 15). For instance, a heightened moment of tension and conflict arises when Rana’s young son comes down the stairs dressed as a girl. Rana reacts with rage and punishes him for this gender subversion; Eddie is distraught in seeing such anger unleashed upon a small child for playing make-believe. Later in the film, however, as Rana’s views begin to evolve, she and Eddie both laugh when Rana’s son is confused about whether to call Eddie “aunt” or “uncle.” Eventually, Rana journeys to Eddie’s house alone to confront Eddie’s father and brother with a plea for tolerance and acceptance. While Rana’s compelling sentiments fail to change Eddie’s father’s point of view, they do have an effect on Eddie’s brother, who eventually helps Eddie fly to freedom in Germany in the end of the film.Footnote 74

Figure 15. Shayesteh Irani and Qazal Shakeri in Facing Mirrors.

Although the film did not receive its official permit to be screened in Iranian movie theatres until almost a year-and-a-half after it was shown at international film festivals, Iranian film critics, journalists, and state-sponsored television channels and radio programs in Iran reported on the film’s success abroad positively without any negative consequences.Footnote 75 According to producer Tāherpur, the best reception of the film was in the holy city of Qom at Mofid University and the second best was at the LGBT Frameline Film Festival in San Francisco (otherwise known as the San Francisco International LGBTQ Film Festival). Tāherpur has also noted that at foreign festivals, organizers and audience members alike were surprised by Iran’s religious and legal acceptance of SRS, and shocked to learn that Iran issues new birth certificates for transgendered individuals. Acknowledging that her crew took the first cinematic step in bringing transsexuality into the public sphere in Iran through a feature film, Tāherpur hopes that Iranian public media, such as radio and television, will continue to produce further representations of transsexuality to educate the population about this issue.

During a panel discussion with the producers and actors of the film after a screening at Mofid University, seminary students and professors praised the movie for its realistic portrayal of trans people’s lives in Iran (Figure 16). Hojjat al-Islam Kariminiā, who has written two books on transsexuality, noted, “We must congratulate the creators of the film on the truth and reality they tried to present to society … they have produced a great work of art.”Footnote 76 Kariminiā also pointed out that Shiʿa jurisprudence and Iran’s legal code are very progressive when it comes to trans issues.Footnote 77 He noted,

We have no shortage [of support] in terms of jurisprudence and gender rights in Iran. It is true that in Facing Mirrors the trans character attempts to leave the country for an easier time, but it should be noted that the character is trying to leave Iran because of the problem that his family creates for him.

Thus, for Kariminiā, Eddie’s desire to flee Iran for transsexual surgery is not because of Islamic rules or state laws against it, as both are favorable to trans people; rather, it is the inability of Eddie’s family to support him in his transformation, as it is common for families, communities, and the media to reject transsexuality and incorrectly equate it with homosexuality and bisexuality.

Figure 16. Shayesteh Irani in Facing Mirrors.

Arastou is critical of the representation of transsexuality in Facing Mirrors. His critique of Facing Mirrors targets the family’s intolerance and the brother’s acceptance. He notes:

In Facing Mirrors we don’t see the reasons of this situation, the reasons for the unawareness of the main character’s family. The director stays on the surface of the reality. For example, when the main character’s brother understood the issue, he accepted easily. It seems he is also an “Other” but the director doesn’t show more, doesn’t analyze his character and leaves him, while he is a very important character.Footnote 78

Arastou believes that audiences should be given the roots and reasons for familial intolerance and ignorance. He thinks directors should investigate and show why a family would force a transsexual child to get married.

Arastou does not consider Facing Mirrors true “realism” because in his opinion it does not analyze the characters deeply. As he explains:

In my opinion “realism” is more complicated, more rough and more objective than what we saw in Facing Mirrors … we do not see the world of the transsexual character, his solitude and the people around him in this film. We do not see the process of getting the permission for SRS from legal medicine or the challenges during this process … Audiences just know he is a man in a woman’s body.Footnote 79

Furthermore, it should be noted that although certification papers are central to transsexual reality in Iran since such legal documents open doors to legibility, legitimacy, and surgery, they do not feature in Facing Mirrors or Cold Breath. Perhaps this is because bureaucracy does not lend itself to drama, or because these films are less about the practical realities of everyday trans life and more geared towards highlighting the drama between family members and friends as a result of a gender transition (Figure 17). According to Arastou, an example of a successful cinematic portrayal of transsexuality is All About My Mother by Pedro Almodovar, because “it speaks about this issue frankly and never pities anyone.”Footnote 80 Arastou also disagrees with the portrayal of Eddie from an acting standpoint, noting: “The other important thing is the acting of the main character; if a woman imitated a man’s behavior, it doesn’t mean she acted the role of an FtM transsexual well.” This critique raises the issue of non-trans actresses cast in trans roles.

Figure 17. Shayesteh Irani and Qazal Shakeri in Facing Mirrors.

Cold Breath: Decentering Transsexuality in Film

Like Facing Mirrors, Cold Breath (2018) by Abbas Raziji has an FtM character at its center. It is not surprising that both films have characters that are FtM not MtF; in Iran, families are generally more accepting of family members who transition from being women to men and not the reverse, since MtFs are viewed culturally as being “passive” sexual partners of other men, which is considered shameful. The plot of Cold Breath revolves around thirty-year-old Maryam, who was born a woman but now identifies as transgender (FtM). She struggles to transition while taking care of her daughter who requires cancer treatment that she cannot afford. As Maryam takes on multiple jobs to care for her two children alone, she keeps her transgender identity a secret, but eventually her complicated past and present are revealed when she tries to get help for her daughter from the wealthy family for whom she works. The film has participated in more than fifty international festivals and has won fifteen notable awards including best film, best director, and best actress (Figure 18).

Figure 18. Bita Badran in Cold Breath (Photo credit: Abbas Raziji).

What is distinctly unique and radical about this film is that while Maryam appears visually to be androgynous, her androgyny and transgender identity are not foregrounded nor are they explicitly central to the plot. On the contrary, her transgender struggle appears to be almost incidental to the plot. In fact, her transgender struggles are not revealed until the latter part of the film. As director Raziji explained to me in an interview, “We are not frank in Iranian cinema … and it has caused Cold Breath to become the most different LGBT movie … the main story is the life story of a female to male transsexual. But during the movie, issues relevant to transsexuals are discussed just for five minutes.”Footnote 81 This film is the first Iranian film to center a transgender character whose gender identity is not the main engine of the plot; rather, it is Maryam’s poverty and struggle to care for her young children that are placed center-stage.

Raziji is well aware of the increase in transsexuals in Iran and the rising interest in transsexual narratives. He notes, “The transsexual population has grown in Iran, I tried to make a movie about it in spite of all difficulties.”Footnote 82 Due to social perceptions of transsexuality that are in opposition to the religious and legal sanctioning of it, there are obstacles for filmmakers in crafting films with transsexual characters; however, the decentering of Maryam’s transgender identity produces a narrative that is uniquely innovative and bold in not directly foregrounding gender even when by appearances it is ever-present. What is also radical is that the other female character is jealous throughout the film of the attention that the man she is interested in gives Maryam instead of her; she does not understand why he would reject her and her feminine appearance in favor of spending time with masculine Maryam, who she does not know is trans.

While Eddie in Facing Mirrors comes from a very wealthy background, Maryam in Cold Breath is drowning in poverty and at the verge of total collapse. In one scene, she even tries to abandon her daughter in public but then regrets it. According to Raziji, “My kind of movies and especially Cold Breath which is an independent movie are often watched more by the upper class of society. So I think discussing problems of the poor part of society for an upper class audience is much more important and effective.”Footnote 83 In contrast to American films, Iranian films since the Islamic Revolution have regularly featured poor protagonists. However, Raziji is not solely concerned with the socioeconomic make-up of Iranian society or Iranian audiences in particular, noting, “If I make a movie in any part of the world, poverty is more interesting for me than wealth.”Footnote 84 When making the film, he was acutely aware of the social difficulties that transsexuals face in Iran. In his opinion, “It is because of social problems in my country that transsexuals don’t dare express their beliefs. In my movie, the main role was the same.”Footnote 85 Thus, Maryam does not express her identity until it is absolutely necessary out of fear of how her condition or positionality may be perceived due to the social difficulties transgendered people often face in Iran.

Keeping Maryam’s gender a floating question for almost the entire film is only possible and successful due to the riveting performance of Bita Badran. Badran rarely works even though she gets offered about fifty screenplays every year. She accepted Cold Breath without even asking for a contract. According to Raziji, he rehearsed with her for about two months to help her find the intended character through rigorous character exploration and research. Her androgynous characterization makes it difficult for the viewer at first to guess whether she is transitioning from female to male or male to female. For other characters in the film, however, her gender is not questioned, and no one comments directly upon her androgynous appearance (Figure 19). The centering of a transgender character whose gender struggle appears to be secondary to her struggles as a mother and provider carves out new space in Iranian film for transgendered characters who are not solely defined by their gender presentation and identity. Further, her diverse background as a poor, trans single mother of a sick child also makes her the first transgendered FtM character in Iranian cinema to struggle with multiple challenging circumstances: a gender transition, poverty, and disability.

Figure 19. Bita Badran in Cold Breath (Photo credit: Abbas Raziji).

The FtM characters in Facing Mirrors and Cold Breath have emotionally intense relationships with other characters but no physical intimacy occurs between them due to censorship rules on touching and certain Islamic legal parameters on transsexual sexual relationships. For instance, a transgendered man (FtM) in Iran who has not had a phalloplasty can live as a man but cannot get married and thus cannot be physically intimate. While trans people in Iran do not have to go through any hormonal or somatic changes to be legally legible, they do need surgical procedures if they want to be involved in an officially recognized sexual relationship, meaning marriage. Thus, because the FtM protagonists of these films have not yet had SRS, it would not be religiously appropriate to suggest such a physical relationship; thus, there are boundaries on transsexual representations in Iranian film with regard to enacted desire and sexuality.

Similar to Facing Mirrors, Cold Breath does not show the bureaucratic, hormonal, or surgical procedures involved in gender transitioning. Arastou contends that Facing Mirrors and Cold Breath reinforce a strict gender binary through their main trans characters. He explains: “In Facing Mirrors and Cold Breath, the directors didn’t consider that all of us are on the gender spectrum. There isn’t any absolute man or women in all around the world. But the directors just indicated the men and women in these films.”Footnote 86 Thus, the “transition” part of transitioning is only spoken about and not shown. Perhaps showing the transition would be too taboo on screen; no trans feature film from Iran has yet depicted the legal procedures, physical changes, and relationship shifts of transitioning.

Arastou critiques both Facing Mirrors and Cold Breath for, in his opinion, not going far enough into realistic detail or emotional depth regarding the experiences of the trans characters and for reinforcing the notion that trans people are to be pitied. Pity, for Arastou, is not conducive to change and understanding—it is momentary and not generative. He continues: “In my opinion, it can be destructive for LGBT [people] when society feels pity about them. It’s the same in Cold Breath. Unfortunately, directors just explain the situation. But is that what the society needs?”Footnote 87 For Arastou, appealing to the emotions and sentimentality of the audience is not enough—it is not transformative nor does it lead to lasting change. He explains:

They can’t persuade the minds of the audiences by exaggerated sentimentalism. Yes, maybe they cry a lot. It does not mean they think. After they cry, they pity the characters. But the LGBTQ community does not need this. They want to be accepted as a part of society.Footnote 88

Thus the question arises: is pity generated from art a necessary vehicle to help transsexuals be accepted in Iranian society, or does it create a distancing effect which makes full acceptance and integration impossible since it relies upon separation and difference?

Conclusion

In situating the assemblage of the transsexual body in Iran in jurisprudential discourse and performance studies instead of queer critical theory, we can venture beyond identity politics to consider more nuanced theoretical questions related to the mutability of the body, the relationship of the body and soul, and the boundaries of legibility and legitimacy. Focusing on how Islamic jurists in the Islamic Republic of Iran have adjudicated and assembled trans bodies in Islamic jurisprudence elucidates the contours of new fictive and real trans bodies and narratives that have recently emerged on stage and screen in Iran. While it is likely that these new representations of transsexuality in the arts are due to the public becoming more educated about transsexuality and transgender artists themselves feeling more emboldened to speak out, it is also possible that the recent turn in the arts towards realism is contributing to greater visibility of trans characters in theatre and film. A film critic present at the panel on Facing Mirrors at Mofid University described the film as a step forward in realism, stating: “The film moves in the right direction of realism”—a style which had receded in the past several decades.Footnote 89 Thus, this recent embrace of the “real” and particularly social realism correlates with the emergence of transsexual narratives on stage and in film.

While theatre and film can be prime vehicles for trans activism in Iran, there are a number of artistic and even ethical questions to consider. It is no accident that Facing Mirrors and Cold Breath feature FtM trans characters instead of MtF characters, as FtM trans people are less stigmatized than MtFs. While Iranian documentaries like Sometimes It Happens (2006) directed by Sharāreh ʿAttāriFootnote 90 and the theatrical performances of Arastou have profiled MtF trans people, Iranian feature (fictional) films have not yet presented a narrative with an MtF character. Theatrical productions like Pink Blue and Arastou’s performances have featured MtF characters because they have incorporated actual trans actors into their narratives. Thus, it is due to trans activism and self-assertion that MtF characters have been represented on stage and not yet in film. While Facing Mirrors and Cold Breath broke new cinematic ground in centering FtM characters, these roles were not performed by trans actors nor were the directors themselves trans. Thus, Arastou recommends introspection for cis artists creating transsexual narratives: “When you want to work on social issues, you should ask yourself: why do I want to work on this (for example LGBTQ)? How much I know them? How long did I live with them? How much do my actors know them? What can I add to the knowledge of transsexuality? In general, am I the right person to do it?”Footnote 91

Creative representations of transsexuality in the arts in the Islamic Republic of Iran highlight the role of the arts as a vehicle for social change, communal recognition, and self-cognition. In analyzing these groundbreaking theatrical and cinematic assemblages of transsexuality, it is imperative to consider the intersections of transsexuality, activism, and emotion, and to recognize the reoccurring theme of violence and abuse. As Arastou explains, “They say we broke the taboos, but is it enough? Audiences come to watch the film and after that say ‘Oh … It’s such a pity’ … and after two hours they forget the issue.”Footnote 92 Thus, he questions whether pity is an effective emotion to help educate and counter violence against transsexuals. In addition, he critiques FtM cinematic narratives for framing transsexuals as separate from society, stuck in a state of transition instead of integrated into family and sexual relationships, work structures, and community life. He notes: “They [the directors] make a wall between LGBTQ and themselves. They separate the transsexuals from other part of the society, while all of us live in the same society.”Footnote 93 The FtM protagonists in Facing Mirrors and Cold Breath are in a state of transition—they exist alone at the margins, not integrated into society, and certainly not happy or fulfilled. Nevertheless, these films do usher Iranian spectators into new forms of viewership and artistic consumption in their attempt to cinematically represent transsexual bodies and narratives to increase tolerance towards transsexuals in Iran; further, they have ignited a conversation among artists and activists about assemblages of transsexual bodies in artistic productions on stage and screen and the most effective narrative and emotional forms of catharsis to inspire change.

Special thanks to Amir Moa'yad Bavand for sharing and translating my questions with Saman Arastou, along with his responses.