Introduction

Throughout its lifetime of more than a millennium, Persian poetry has undergone many changes and seen numerous innovations in poetic style, content, and linguistic details. Yet an important element of this tradition—i.e. its metrical system—has survived to this day in the works of many Persian poets. From a purely metrical perspective, there is little difference between the tenth century epic poetry of Ferdowsi, the thirteenth century Sufi poetry of Rumi, the early twentieth century satire of Iraj Mirza, and even the contemporary post-modern ghazals of Fatemeh Ekhtesari. Under this meter-based approach, this vast and diverse body of literary works can be distinguished from parallel traditions such as nasr-e mosajjaʿ (rhymed prose), folk songs, nursery rhymes, pop lyrics, bahr-e tavil, sheʿr-e now (lit. “new poetry”) and sheʿr-e sepid (lit. “white poetry”), some of which are indeed metrical but differ substantially from it in the specifics of how meter is formed and how verses are identified and grouped together.

The metrical requirements of Persian poetry are exceptionally restrictive in comparison to other well-known metrical traditions (see below). A considerable part of the poet’s efforts is directed at finding the right words and arranging them in such a way that meets these requirements. This paper examines the solutions that have been deployed in Persian poetry for dealing with this issue, their linguistic roots, and most importantly how the trajectory of linguistic changes in Persian has had a negative effect on the relative ease of composing metrical poetry.

As a preamble to the main discussion, it is helpful to highlight the exceptionally restrictive nature of the Persian metrical system and examine how it affects Persian poetry. Metricality in Persian is determined by the weights of syllables, which is measured in terms of morae (singular: mora). Mora is an abstract unit of time measuring perceived length. The number of morae in a syllable is determined by the type of the vowel and the number of consonants that follow it (i.e. the coda consonants). In the most general case, a short vowel (a, e, o)Footnote 1 counts as one mora, a long vowel (ā, ū, ī) counts as two morae, and each coda consonant counts as one mora. Thus, “be” is a one-mora (light) syllable, “bar” and “bā” are two-mora (heavy) syllables, and “bord” and “bīm” are three-mora (superheavy) syllables.Footnote 2 There are various exceptions to this general pattern, which have been discussed thoroughly in the literature and are not repeated here.Footnote 3

The succession of different syllable weights in a Persian phrase creates a pattern. The metricality of a line of poetry is determined by the abstract pattern that it creates. For instance, the Persian phrase “tavānā bovad harke dānā bovad” is metrical by virtue of the fact that it matches the pattern “LHHLHHLHHLH” (where L denotes a light syllable and H denotes a heavy syllable), which is considered metrically well-formed in the Persian metrical system. This relationship is illustrated in example 1 (this and all other non-contemporary verse examples in the text are taken from Ganjoor Online Collection).

Factoring out a few poetic licenses, it can be said that all verses in a single poem must have the same syllable sequence. The verses of Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh and Saʿdi’s Bustān, for example, are entirely based on the syllable sequence shown in example 1. Roughly speaking, verses that have the same metrically valid syllable sequence are said to belong to the same “meter.” A meter in the Persian metrical system is commonly introduced as a sequence of L and H symbols. Superheavy syllables can always be treated as HL in verse-medial positions and as H in verse-final positions.

A survey of more than 45,000 poems by fifty-eight well-known Persian poets over a period of almost a thousand years by Parhizi shows that more than 95 percent of these poems are composed in one of the sixty-eight most common meters.Footnote 4 To give the reader a sense of what these patterns look like, the five most common Persian meters (according to Parhizi’s corpus study) are shown in the list below. For ease of reading, the patterns are broken into smaller blocks (in accordance with traditional meter fragmentation practices) with spaces.

(2)

-

a. HLHH HLHH HLHH HLH

-

b. bLHLH LLHH LHLH LLH

-

c. HHL HLHL LHHL HLH

-

d. LLHH LLHH LLHH LLH

-

e. LHHH LHHH LHHH LHHH

The question of what makes a particular syllable sequence metrical does not concern us here.Footnote 5 What is relevant to our discussion is the fact that these meters have very strict requirements. As an extreme example, consider the meters used in example 1 (“LHH LHH LHH LH”). It is impossible to use any Persian word with an LL syllable sequence in a poem in this meter. This immediately rules out all subjunctive and imperative verb forms of modern Persian whose conjugated present stems begin with L syllables (e.g. “beravad”: “that he goes”; “beshavam”: “that I become”; “nazanīd”: “that you do not hit”). Similarly, HHH sequences are not allowed in this meter, ruling out all present indicative verbs of modern Persian whose conjugated present stems begin with H syllables (e.g. “mībīnam”: “I see”; “mībandī”: “you close”; “mīgūyīm”: “we say”). This means that for each modern Persian verb, either the subjunctive and imperative forms or the present indicative forms are disallowed. All Persian meters impose such limitations on the poet, although the degrees of restrictiveness of the requirements vary depending on the precise form of the syllable sequence.

There are a few poetic licenses that slightly relax these metrical requirements, but unlike other metrical traditions, their scope of influence is extremely limited in Persian. These poetic licenses are as follows:Footnote 6

-

1. Contraction (Using H in place of LL): In Persian, contraction is common immediately before the last syllable of a verse (contraction in other positions is typically avoided).

-

2. Augmentation (The optional use of H in place of L): This is allowed only in verse-initial syllables in five of the sixty-eight common Persian meters.

-

3. Swapping (Using LH in place of HL): A few Persian meters allow certain instances of LHLH and HLLH to be used interchangeably.

To put the restrictiveness of the Persian metrical system in perspective, it is useful to look at a few other metrical traditions. The most similar metrical traditions to Persian are those that have a quantitative structure—i.e. traditions relying on syllable length for creating metrical patterns. The most well-studied quantitative metrical traditions include Arabic, Greek, Latin, Japanese, and Sanskrit, which are discussed below.

The metrical system of classical Arabic, which has long been in contact with that of Persian and is believed to have greatly influenced it (and perhaps contributed significantly to its very existence), uses a far more generous set of poetic licenses. In Arabic poetry, augmentation is allowed (and indeed very common) in several positions in most meters (e.g. the poet is allowed to use pairs such as LHL/LHH, LLHH/HLHH, and LHLH/HHLH interchangeably), contraction is abundant in several positions in two of the sixteen Arabic meter families (Wāfir and Kāmil), and swapping is allowed in two of the sixteen meter families (several positions in Rajaz and one position in Sarīʿ). Unlike Persian, these poetic licenses are used extensively in Arabic. In fact, two randomly chosen verses from a single Arabic poem most likely have different syllable sequences.Footnote 7

The case of classical Greek poetry is similar to that of Arabic. In any Greek meter, at least one of the aforementioned metrical licenses—swapping, contraction, and interchangeable use of L and H (augmentation)—is likely to be observed. In the dactylic hexameter, for example, any of the LL sequences in the pattern (“HLL HLL HLL HLL HLL HH”) can be realized as H. The situation is quite similar in Latin. In Indo-Aryan poetry, the syllable sequence can vary across verses.Footnote 8 Japanese poetry is the most flexible of them all; the syllable sequence of each verse can take almost any form as long as its overall mora count matches the required number.

In qualitative metrical traditions (i.e. those that are based on stress rather than syllable weight), even higher degrees of flexibility are typically found. As an example, consider English metrical poetry, where the metrical patterns most commonly in use are based on alternations of stressed and unstressed positions. There are three sources of flexibility in this tradition. First, unstressed syllables are normally allowed to occupy stressed positions when needed; it is only the opposite that is generally disallowed. Second, there are position-specific poetic licenses that even allow stressed syllables to occupy unstressed positions under certain conditions.Footnote 9 Third, and most importantly, English words naturally tend to exhibit alternating patterns of stressed and unstressed syllables, making it relatively easy to fit them inside these metrical patterns.

Given how relaxed these metrical systems are, one can ask why the Persian metrical system has developed such strict requirements and how poets have coped with it. It seems reasonable to assume that in the absence of competing factors, this level of near-perfect metrical similarity among verses is a favorable property from the viewpoint of rhythmic aesthetics. At least in Persian poetry, poetic licenses—which cause deviations from this rhythmic uniformity—are usually deemed unfavorable and avoided if possible. Part of what motivates the presence of poetic licenses in metrical systems is the poet’s needs arising from linguistic exigencies. In Persian poetry, I argue, this high degree of metrical rigidity is compensated for by a high degree of linguistic flexibility.Footnote 10 In other words, the language used in Persian poetry (especially in its earlier days) allows for the same sentence to be expressed in multiple ways, leaving the poet free in choosing the one that fits the metrical requirements of the poem. The factors contributing to this flexibility are discussed in the next section.

Elements of Linguistic Flexibility

The degree of linguistic flexibility varies across different varieties of Persian. Following what is probably a universal trend, at the synchronic level, the language of poetry seems to have always been considerably more flexible than that of prose throughout all periods in New Persian (examples of elements of flexibility that are mostly restricted to poetry are presented later in this section). The more unexpected result argued for here is that there is a strong diachronic effect too, with more recent varieties of Persian being less flexible.

I demonstrate this shift towards rigidity for the language used in poetry (more specifically, in poetic works that follow the general metrical structure of traditional Persian poetry). However, the arguments provided and the nature of some of the specific linguistic elements involved strongly suggest that this shift towards rigidity is not confined to the poetic language, but has affected the language of prose too, although seemingly to a lesser degree.

The version of Persian used in the majority of works of metrical Persian poetry (at least until recent times) is a semi-artificial register of the language developed during the early stages of the life of New Persian as a written language (the oldest extant New Persian documents belong to eighth century CE). In particular, this language is semi-artificial in that it allows for forms that are absent in the prose language of all genres and, as this paper argues, were incorporated into the poetic language as a byproduct of the poets’ collective effort to fit their words within the metrical limits. For instance, the optional use of “ze” instead of “az” for “from” and similarly “ar” instead of “agar” for “if” was extremely rare even in the earliest centuries of classical Persian prose and virtually non-existent afterwards (see below), but was quite common in Persian poetry since its earliest days and remained part of the poetic language until recent times. This is in contrast with the so-called “poetic” contractions in English such as “o’er” (for “over) and “oft” (for “often”), which at some point used to be part of standard English prose.Footnote 11

The linguistic elements that make the poetic language of classical Persian flexible have been developed for different historical reasons and take different forms. I refer to these points of linguistic variation as “linguistic licenses.” The use of this term is not intended to imply that some of these variants are necessarily non-canonical in any way or that they reflect innovations. These are simply linguistic items in both poetry and prose that are allowed to appear in more than one way, whatever the causes of this variation may be. I argue in this paper that the prevalence of these linguistic licenses has decreased over the centuries in Persian poetry, making the poetic language of Persian a more rigid one. The question of how and why this shift has occurred is discussed in the following two sections. In this section, I aim to introduce these linguistic licenses, focusing on the ones that are absent or less saliently present in modern Persian prose and poetry.

These linguistic licenses can be divided into three categories: (1) flexibility in word order, (2) phonological and lexical elements with more than one acceptable form, and (3) morpho-syntactic elements with more than one acceptable form. They are introduced in this section and are then used as the basis of a statistical analysis in the next section to examine diachronic changes in linguistic flexibility.

It is crucial to note that while the sources of flexibility discussed below are all present in the poetic language of classical Persian, any of them may also be present in classical prose, modern prose, or modern poetry too. A detailed discussion of the diachronic aspects of flexibility and the relationship between the language of prose and poetry in this regard is postponed to the following two sections.

Word order

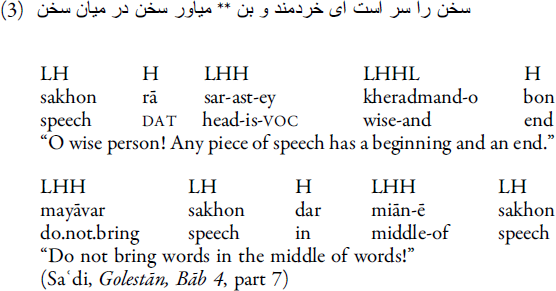

In both classical and modern New Persian, the default word order in prose is subject–object–verb.Footnote 12 However, the order of syntactic constituents can vary as a result of different factors such as topicalization, focus, and stylistic preferences. In general, this relatively free word order (often called “scrambling” in the linguistic literature) is most clearly visible in the spoken—rather than the written—language.Footnote 13 In poetic language, however, it is taken advantage of quite extensively for both stylistic and metrical purposes. Consider the verses in example 3 by Saʿdi. The meter is the same as the one used in example 1.

For the first sentence, the default word order is quite different from what we see in the verse. This is demonstrated below.

It is worth mentioning that one of the scrambled elements in this case (“o bon”: “and ending”) is not even a proper syntactic constituent but has moved in the sentence nevertheless. This significant degree of freedom contributes enormously to the flexibility of the poetic language.

The poet uses scrambling to overcome not only metrical restrictions, but also restrictions enforced by rhyming conventions. Since Persian is a verb-final language (in its default word-order) and the rhyme is placed at the end of the verse, in the absence of scrambling the poets have to either choose the verb itself as the rhyming word—e.g. rhyme the verb “gīrī” (“you get”) with “mīrī” (“you die”)—or use the verb as “radīf,” i.e. repeat the verb at the end of each verse and make the words preceding it across the verses rhyme with each other—e.g. use “āb gīrī” (“you get water”) in one verse and “javāb gīrī” (“you get an answer”) in the other.

Both of these options are extremely restrictive; in the former case the poet needs to find rhyming verbs among Persian’s exceptionally limited inventory of simple verbs (fewer than a hundred commonly used simple verbs in today’s Persian) and in the latter case the poet needs to form only sentences with the same verb, which is particularly problematic in genres such as ghazal where an entire poem is based on the same rhyme, meaning that the poet must create sentences using the same verb in every rhyming verse of the poem. Scrambling solves the issue by allowing the poet to move the verb around and use other words (e.g. a noun or adjective) as the rhyming word.

Morpho-syntactic elements

There is a wide range of morpho-syntactic linguistic licenses found in the poetic language of classical Persian. Most of these are present in classical Persian prose too, although their frequencies may differ. As discussed later, a large portion of them have disappeared in the standard prose of modern Persian and even their use in poetry has significantly decreased. Some of the most important items are listed below.

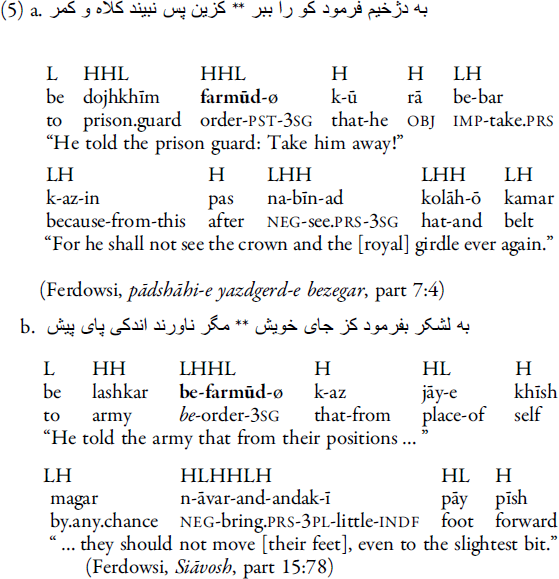

The verbal prefix be: This prefix is quite common in Persian and various verb tenses including the past simple, present simple, subjunctive, and the imperative can be preceded by it in both prose and poetry in classical Persian. The use of be- is not always mandatory in these verb forms, but this does not exactly mean that the forms with and without be-, e.g. raftam vs. beraftam (“I went”) and ravam vs. beravam (“I go”), are in free variation. As Lazard has shown, it tends to appear when the verb has semantic autonomy, i.e. has strength or emphasis.Footnote 14 One may interpret this to mean that this prefix indicates what is called “focus” by syntacticians. However, the distribution of this prefix is not entirely predictable. Many poets seem to use or omit this prefix freely when needed. Rumi, for instance, has sentences in his verses starting with each of bin ke and bebin ke for the imperative form “see that.” Taking the first 1,000 ghazals in his divan as our sample, we see five sentences starting with bin ke (46:4, 49:5, 708:8, 886:4, 1000:9) and five starting with bebin ke (224:8, 480:5, 485:7, 699:8, 701:3). As another example, consider the third person singular past simple form [be]-farmūd (“ordered”) in the pair of sample verses by Ferdowsi shown in example 5.

The syntactic and semantic properties of the verb farmūdan (“to order”) are the same in be dojhkhīm farmūd in example 5a and be lashkar be-farmūd in example 5b, yet the first one does not have the prefix be- while the second one does. The root of this difference seems to be the metrical requirements of the poems. While be dojhkhīm in the first example has the syllable sequence LHHL, be lashkar maps to LHH (note that khīm is a superheavy syllable and is therefore mapped to HL). The prefix be- in the verb befarmūd in the second example makes up for this metrical difference.

On some occasions, be- can even precede infinitives as an optional prefix (e.g. be-goftan and goftan for “to say”) and participles (e.g. be-baste and baste for “closed”). Extensive discussions of this prefix have been offered by Lazard, Natel Khanlari, and Lenepveu-Hotz.Footnote 15 Various examples from classical Persian poetry are given by Abolghasemi.Footnote 16

The morphemes mī and hamī in present tense verbs: Roughly speaking, the forms ravam, mī-ravam, and hamī ravam all mean “I go” in classical Persian. Much has been said about the potential subtle syntactic, dialectal, diachronic, and prosodic differences between these forms, but it seems clear that there are contexts where they can be used interchangeably in classical Persian poetry—e.g. see the discussion of the verb gūyad (“says”) by Lenepveu-Hotz.Footnote 17 As Lazard points out, the prefixes mī and hamī are durative prefixes but their absence does not mean that the verb is not durative.Footnote 18 Thus, leaving focus-related issues aside, these three forms are in free variation in durative verbs in the present tense. In other words, forms such as mī-ravam (with the prefix) necessarily means “I am going” whereas ravam (without the prefix) could mean “I go,” “I am going,” or “that I go” (subjunctive). The morphemes mī and hamī seem to function similarly.

What makes hamī particularly interesting with respect to linguistic flexibility is that it can move around in the sentence, at times even appearing after the verb. Thus, for “she eats bread,” in addition to nān khorad (without hamī) and nān hamī-khorad (with hamī), one could have hamī nān khorad and nān khorad hamī (the examples are synthesized and not necessarily attested in the exact given forms). The verses in example 6 show the use of hamī in three different positions with the verb āyad (“comes”) in verses by Saʿdi. The verb and the morpheme hamī are marked with bold font.

The forms bovad and bāshad: These two forms are both generally said to be subjunctive forms of the third person singular copula (roughly translated as “that she/he/it be”). Their actual usage pattern, however, is much more complicated. There is significant overlap between the scope of use of the indicative third person singular present copula ast and the two forms bovad and bāshad that are usually referred to as subjunctive. Thus, at least in some contexts, it appears that forms such as shīrin ast, shīrin bāshad, and shīrin bovad would all mean “is sweet,” with little to no semantic or syntactic difference. An extensive discussion of the use of these forms and their overlap is presented by Lenepveu-Hotz.Footnote 19 The prose examples shown here in example 7 are helpful in demonstrating the interchangeability of these forms (the transcriptions of the vowels are changed to match the format of the present paper). The sentences are identical in all of their syntactic and semantic properties, but one comes with ast and the other with bovad.

Genitive rā: The morpheme rā is known as an object marker in modern Persian. For instance, alī rā dīdam translates to “I saw Ali,” where rā marks the object ali. This marker is required to make the sentence grammatical and to indicate that “Ali” is the object. In classical Persian, this morpheme has another role too; it can mark possession, serving as an alternative to the ezafe construction. For instance, dast-e alī (“Ali’s hand”) can alternatively be expressed as alī rā dast (where the order is reversed, the ezafe morpheme e is removed, and the morpheme rā is added to mark the possessor). Both forms are quite common in classical Persian.

Dative rā: Many indirect objects that are expressed using prepositional phrases in modern Persian can optionally be expressed using rā in classical Persian. A remarkable example is the verb goftan (“to say,” “to tell”), for which the addressee can appear either followed by rā or preceded by the preposition be (“to”). Two examples of these two structures used by Saʿdi are presented in example 8.

In example 8a, the addressee, sarv (“cypress”), takes the preposition be while in example 8b the addressee, aql (“wisdom”), is followed by rā. It appears that the prepositional form has taken over the rā-based form over the centuries, but the availability of the two forms in parallel during the transition period has been taken advantage of by poets to create a more flexible language (more on the origins of these linguistic variations later).

Unfortunately, it is not easy to quantify the degree of contribution of the variations listed above to the flexibility of the classical language. None of these variations are instances of free variation in all contexts. For instance, given a sentence using the verb bovad, it is often difficult to claim with certainty whether the use of bovad in the given context is mandatory or is one of the cases where it overlaps with the scope of ast and/or bāshad. As a result, I refrain from including the above cases in the statistical analysis of the next section. The morpho-syntactic variations that are included in our statistical analysis are the ones that can be identified in each verse with more confidence. These are listed below.

Movement of clitics: Personal pronouns can appear as clitics in classical Persian, indicating possessors, objects and indirect objects (i.e. genitive, accusative, and dative cases). Example 9 shows all three uses for the second person singular personal pronoun -at.

The dative use of the clitics (as in example 9c) is not allowed in standard modern Persian. What makes these clitics relevant to the present discussion is that they have a highly variable position in the sentence. In the poetic language of classical Persian, this variability is considerably higher, as Abolghasemi and Lazard have pointed out.Footnote 21 For instance, as example 14 shows, the possessive clitic can optionally be attached to words other than the possessee (this is not possible in modern Persian).

The movement of the object clitic is shown in the verses in example 10, both by Ferdowsi. The sentences have very similar structures, but the third person singular clitic -(a)sh is attached to the verb in the first case and to a noun in the second one.

For direct and indirect objects, the two most common positions are immediately after the verb (as in example 10b) and in the second position in the sentence (as in example 10a) as noted by Mofidi,Footnote 22 of which the latter is more common according to Natel Khanlari.Footnote 23 Again, these clitics are found in other positions in the sentence too. For instance, they sometimes attach to a preposition or particle (a valid instance of this would be attaching to the initial ke in example 10). Example 11 demonstrates this.

To be as cautious as possible in counting linguistic licenses, I take the lower hand and treat both of the forms shown in example 10 as unmarked in the statistical analysis of the next section (because one may argue that the distribution between these two positions is at least partly governed by factors that are not yet known to us). However, sentences where the clitic appears in positions other than these (such as the one shown in example 11) are counted as cases where the poet has taken advantage of the flexibility of the language. In modern Persian, the position of the accusative enclitic pronoun is almost always fixed (attaching to the verb itself or to the non-verbal element if the verb is a compound verb).Footnote 24

Movement of the negation marker: The verbal negation marker na or ne—which is by default expected to immediately precede the verb—is sometimes separated from it. For instance, the verb bar na-khāst (“did not rise”), in which bar is a verbal particle usually denoting direction and khāst is the past stem of “to rise,” can appear as na bar khāst too (e.g. line 3 in Saʿdi’s ghazal 50). In some cases, the negation prefix moves forward, appearing between the durative prefix mī- and the verb stem, e.g. mī-na-konam instead of ne-mī-konam for “I do not do.” The negation marker can be separated from different forms of the verb “to be” too: the sentence chonin na-bāshad (“It is not so”) can alternatively appear as na chonin bāshad.

The morpheme mar: In earlier classical Persian texts, a noun phrase followed by rā is sometimes also preceded by the morpheme mar. The phrase shāh rā (roughly translated as “the king,” “of the king,” or “to the king”), for instance, may alternatively appear as mar shāh rā. This morpheme is relatively uncommon in most classical Persian poems especially after the twelfth century CE. However, some later poets, such as Rumi in the thirteenth century, do use it occasionally, possibly in part motivated by metrical demands (to give the reader a rough estimate of how common this morpheme is, it may be helpful to mention that it is used ten times in total in the first fifty ghazals of Rumi’s Divan).

Infinitives after modals: Modals such as khāstan (“to want”) and tavānestan (“to be able to”) are typically followed by a bare past stem of the verb they modify. However, an infinitive is also allowed to follow the modal. Instances of the two cases are shown in examples 12a and 12b respectively. The latter case is the less frequent form in the works of all of the poets examined in this study.

Adjectives preceding nouns: While the default position of the adjective in New Persian is after the noun (connected to it by an ezafe), the archaic Middle Persian formula of placing the adjective before the noun is occasionally used in New Persian. For instance, instead of yār-e bīvafā (“unfaithful friend”), one may see bīvafā yār (e.g. line 5 in Saʿdi’s ghazal 350).

Circumpositions: By default, New Persian relies primarily on prepositions (rather than postpositions and circumpositions). However, there are cases where the word dar (“in”) can follow a noun phrase that is already preceded by a prepositional morpheme, e.g. be daryā dar for “in the sea” instead of either dar daryā or be daryā (e.g. Saʿdi’s Golestān, 1:16).

An important point to note is that the flexibility of the poetic language is not caused only by the availability of multiple options in each case, but also by the shortness of some of these options. In some respects, composing metrical poetry is similar to arranging a set of blocks with different shapes next to each other to arrive at a specific larger shape. The smaller the pieces of the puzzle are, the easier it is to produce the desired final form. For instance, the long form of present tense verbs in modern Persian causes a problem in metrical poetry. In modern Persian prose, the use of the prefixes mī- and be- is mandatory for present indicative and subjunctive verbs respectively. In classical Persian, however, these verbs can appear without these prefixes. The extra word length caused by these prefixes makes a crucial difference. As an instance, consider the meter used in example 1. As discussed in the previous section, this meter is formed of repetitions of LHH and thereby disallows either the present indicative or the subjunctive form of any given verb in formal modern Persian. This problem does not occur in the classical poetic language since for any Persian verb the present indicative and subjunctive can both appear as either LH (e.g. “ravam”: “I go”) or HH (e.g. “gīram”) which are short enough to fit in almost any metrical pattern.

Phonological and lexical elements. Of the many lexical and phonological variations allowed in the classical poetic language, fifteen of the most important items are chosen for statistical analysis in this paper. Most of the alternatives presented here are exclusive to the poetic language and are absent not only in formal modern Persian, but also in mainstream prose of classical Persian (more on the origins and distribution of these alternative forms later). Some of these variations target specific words. For instance, as mentioned in the introduction, the preposition “az” can appear as “ze” in the poetic language. A list of these cases is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Lexical differences between the classical poetic language and formal modern Persian

In addition to these lexical variations (which may in fact be nothing but prominent instances of more general phonological variations), there are a number of cases of phonological free variations that apply to large groups of commonly used words. These cases are introduced below.

-

1. The long vowel ā can usually be replaced by a short vowel a before a morpheme-final h. This affects many high-frequency words in poetry.Footnote 25 Examples: mah (“moon”), shah (“king”), gah (“time,” “place”), rah (“way”), siah (“black”), kūtah (“short”), gonah (“sin”), āgah (“aware”).

-

2. In classical Persian, the letter vāv ( و ) could among other things denote either ū or ō. The two vowels were later merged into ū in most varieties of Iranian Persian (but not in other varieties). In many words, the long vowel ō (and even in some cases the long vowel ū) could be used interchangeably with the short vowel that is transcribed as o today. Examples of the shortened versions: bod (“was”), hosh (“consciousness,” “awareness”), andoh (“sorrow”), so-ye (“towards”), bīhode (“in vain”), koh (“mountain”), khāmosh (“silent”).

-

3. In many words (most of which were pronounced with an initial consonant cluster at some point in their history)Footnote 26 a vowel can optionally appear before or after the first consonant. Examples: oftādan/fetādan (“to fall”), estādan/setādan (“to stand up”), afkandan/fekandan (“to throw”), afzūdan/fozūdan (“to increase”), aknūn/konūn (“now”), espīd/sepīd (“white”), oshtor/shotor (“camel”), afsūn/fosūn (“spell,” “deception”), afsāne/fesāne (“tale”), eshkam/shekam (“stomach”).

-

4. In the personal pronoun clitics, the initial vowel may be deleted if the resulting form is not phonologically ill-formed. For instance, farmān-at (“your command”) may alternatively be pronounced as farmān-t. Similarly, jān-eshān (“their li[ves]”) can also appear as jān-shān. An instance of the third person singular clitic -ash appearing as -sh can be seen in example 10.

-

5. When a word ending with ī is followed by an ezafe, the addition of an epenthetic y is optional. For instance, the poet is allowed to use both māhi-e daryā Footnote 27 (the default form) and māhī-ye daryā for “the fish of the sea.” The syllable sequences of the two forms for this example are HLL HH and HHL HH respectively.

-

6. Vowel hiatus at stem boundaries in some verbs can optionally result in deletion of the first vowel or glide epenthesis, e.g. nay-āvarad/n-āvarad (“does not bring”), nay-āmad/n-āmad (“did not come”), may-andīsh/m-andīsh (“do not fear”). It is quite common for a single poet to use both forms. A pair of example verses by Ferdowsi using nay-āmad and nāmad (“did not come”) are presented in example 13.

Diachronic Analysis

Having provided our list of items that contribute to linguistic flexibility, we can now look at statistical data regarding their use in Persian poetry. The purpose of this statistical survey is to examine and demonstrate to what extent the linguistic flexibility of the language used in metrical Persian poetry has decreased over time.

To make a historical comparison, I focus on four periods of Persian poetry, as described below, and examine the works of six poets from each period. To make the samples more comparable, I only look at ghazals from these poets. Effort was made to make a balance between choosing the most well-known poets of each era who have produced ghazals and making a selection that is representative of the poetry of the era as much as possible in terms of geography and genre.

-

1. Classical Era: This period spans from the eleventh to fourteenth century CE. The six poets sampled from this period are as follows (dates in parentheses show birth years): Sanai (1080), Khaqani (1120), Anvari (1126), Rumi (1207), Saʿdi (1210), and Hafez (1315).

-

2. Safavid Era: The poets in this category spent at least part of their life in Safavid Iran or Mughal India between the sixteenth century CE and 1720 CE (the fall of the Safavid Empire). The six poets are Mohtasham Kashani (1500), Vahshi Bafqi (1532), Artimani (1571), Saeb Tabrizi (1592), Bidel Dehlavi (1642), and Hazin Lahiji (1692).

-

3. Modern Era: This category includes poets who were born in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century. Among them, two poets are from outside of Iran (Iqbal from British India and Khalili from Afghanistan). The six poets are Iqbal (1877), Shahriar (1907), Khalilollah Khalili (1907), Rahi Moayyeri (1909), Simin Behbahani (1927), and Houshang Ebtehaj (1928).

-

4. Post-1979: The poets in this category produced all of their major works after 1979 (the year of the Iranian revolution and the beginning of the Soviet–Afghan war in Afghanistan). Among them, Qahar Asi and Kazem Kazemi are from Afghanistan while the rest were born in Iran. The six poets are Qahar Asi (1956), Qeysar Aminpour (1959), Kazem Kazemi (1968), Fazel Nazari (1979), Hamed Askari (1982), and Fatemeh Ekhtesari (1986).

Fifteen poems were randomly selected from each poet, making sure that each poem contains at least sixty words (usually above 150 words; six pairs of verses, i.e. beyts). For each poem, I counted the number of times elements of linguistic variation as listed in the previous section were used. For each case of linguistic variation, one form is considered the default form and all occurrences of the alternative forms are counted as cases of exploiting linguistic flexibility.

For lexical and phonological alternations as well as word order, the default form is taken to be the one most commonly found in the prose of the era. For morpho-syntactic alternations, to be as cautious as possible, the default form is determined based on what is most common in the poetry of each poet. In practice, it was observed that default form is the same for all of them and matches the one introduced in the descriptions of the previous section. For scrambling, the number of movements required to reach the default word order are counted as instances of use of linguistic licenses. For instance, consider the verses in example 14.

The elements of linguistic variation exploited by the poet in these verses are listed below:

-

1. Two alternative forms of the word agar (“if”) are used (ar and gar).

-

2. An alternative form of the present simple tense of the verb “to do” is used: mīkonand instead of konand which is the more common form in both prose and poetry in classical Persian.

-

3. The possessive clitic is moved in the first verse. Instead of qasd-e halāk-am (“the intention of killing me”), the clitic -am appears after doshman (“enemy”). Similarly, for the enclitic pronoun of the second verse, if we assume it to be marking possession, we can argue that instead of attaching to the possessee—i.e. dūst-am (“my friend”)—the clitic -am follows gar (“if”). However, one may propose alternatively that -am is dative rather than possessive here (“you are a friend to me” rather than “you are my friend”), in which case its placement in the second position is unmarked. In the statistical analysis, I do not count such ambiguous cases as instances of linguistic licenses.

-

4. Three movements (besides that of the clitic) are needed to make the word order in these sentences match the default order. In particular, ar must move to the beginning of the first sentence, the verb mīkonand must move to the end of the first sentence, and the verb nadāram must move to the end of the second sentence.

In any poem that has a non-verbal rhyme word at the end, there will be many cases of verb movement (almost once per rhyme). To reduce the effect of rhyme selection in our count, I count non-canonical forms that appear as a result of rhyme placement only once for each rhyme. This means that 3–1=2 movements are counted for the above verses. In total, the two verses shown above exhibit 2+1+1+(3–1)=6 linguistic licenses according to our count.

Based on the fifteen sample poems examined in this study, on average Hafez takes advantage of the designated set of linguistic variations around 12.5 (±1.52) times per 100 words in his poetry. This is in fact a very large number. Each beyt (pair of verses normally written together in one line and used as units of rhyming) in a Persian ghazal is usually around fifteen words, meaning that Hafez uses these linguistic licenses about 1.9 times per beyt. Given that a large number of linguistic licenses are not considered in our count and considering that the effect of the availability of shorter linguistic units is not covered by this measure, it seems fair to suggest that linguistic flexibility plays a major role in allowing Hafez to compose metrical poetry with the level of perfection that we see.

Hafez is by no means an exception among classical poets. Figure 1 shows the use of linguistic licenses among the twenty-four poets whose works were examined in this paper. The poets are sorted chronologically from left to right based on year of birth. The error bars indicate two standard errors; 95.4 percent of random samples of the same size from a poet’s works are expected to show an average within the range shown by the error bar. The four periods are distinguished in the chart by alternate shading.

Figure 1. Number of linguistic licenses used per 100 words.

Rather than individual poets, what we are interested in is the overall changes of the poetic language throughout history. It is already clear from Figure 1 that the use of the designated variations in Persian poetry decreases over time. Figure 2 gives us a comparison of the four eras introduced earlier and divides them by type.

Figure 2. Average number of linguistic licenses used by the poets of each period.

The use of these linguistic licenses has generally been in decline throughout the four periods. It is particularly interesting that there is a sharp decrease from the “Modern” poets (mainly active during the late Qajar and Pahlavi periods) to the “Post-1979” poets even though the temporal distance between these periods is relatively small. In poems of the “Post-1979” category, the language is very close to that of prose. For instance, consider the verses by Fazel Nazari (b. 1979) shown in example 15. The gloss is simplified to make it easier to focus on the overall structure of the sentences.

The language used in the above verses is very similar to the language of contemporary prose. Perhaps the only deviation is that the word sorāgh in the first verse would appear right before the verb in prose. This degree of similarity to prose language is quite typical of contemporary Persian poetry. In contrast, it is quite difficult to find a poem in classical Persian literature with so much similarity to the prose language of its own era. The details of this change and its causes are discussed in the next section.

The Roots of the Change

In order to be able to conclude from the data in Figure 2 that linguistic flexibility in the poetic language has decreased over the years, we must answer one important question: Is the set of linguistic licenses examined in this study a cherry-picked selection biased towards items that are allowed in older varieties of Persian but disallowed in more recent varieties, or do they in fact reflect a general trend towards a more rigid poetic language? It seems that we can argue with a high degree of confidence that the latter is true. My argument in support of this answer and an account of why this change has taken place is presented later in this section. Before beginning the discussion, however, it is helpful to take a closer look at the historical trend and focus on the trajectory of each category of linguistic licenses, as presented in Table 2. The error values shown in parentheses indicate two standard errors (the 95.4 percent region).

Table 2. Average frequency of each category of linguistic licenses (per 100 words)

Note that what matters in these figures is the historical trend rather than a comparison between the three categories of linguistic licenses. For instance, the fact that lexicon and phonology have a larger share in our count in comparison to morpho-syntax is not necessarily meaningful. Had we chosen to take into account a larger number of morpho-syntactic licenses in our count, the results would be different.

The general historical trend is quite interesting, but as the error bars in Figure 2 suggest, the estimates are not very accurate and comparison between close numbers must be made with caution. To test the significance of the differences between the numbers, the one-way ANOVA method was used.Footnote 29 It was observed that the slight increase in the “word order” category from the classical period to the Safavid period is not statistically significant (p > 0.1). However, the decreases from “Safavid” to “Modern” and from “Modern” to “Post-1979” are indeed significant (p < 0.01 in both cases). For the “lexicon and phonology” category, except for the decrease from “Safavid” to “Modern,” the decreases between consecutive periods are statistically significant (p < 0.05). In the “Morpho-syntax” category, only the decrease from “Modern” to “Post-1979” is significant (p < 0.05).

In the following three subsections, I examine the causes of these changes, arguing that the drivers of change for these three categories of linguistic licenses, although related, are not exactly the same.

Changes in morpho-syntax.

Before answering the question of what gave rise to a high degree of flexibility in the morpho-syntax of early classical Persian and what led to its decline in later eras, we must make sure that our observation is not biased. Aren’t there similar morpho-syntactic linguistic licenses that are exclusive to more recent forms of Persian?

It is in fact quite difficult to find systematic linguistic licenses that exist in today’s formal Persian but are absent in the classical language. Let us review some of the most reasonable candidates one by one. All verb forms have exactly one standard method of conjugation in formal modern Persian. The only major exception is the present copula (“to be”), which has a stand-alone form and a clitic form (e.g. am and hastam for the first person singular). This variation, however, exists in the classical language too, along with at least one other form (bāsham).

Pronouns have a stand-alone form and a clitic form, just like classical Persian (although, as discussed earlier, they cannot move around in the sentence as freely). Adjectives necessarily follow the noun with an ezafe, and prepositions are the only available adpositions (assuming that the object marker rā does not count as an adposition).

Possibly the best example of a linguistic license exclusive to modern Persian is the placement of the object marker rā with respect to relative clauses starting with ke. For “I saw the man who left”, one can put the object marker after the relative clause, saying mard-ī ke raft rā dīdam, or alternatively put it before it: mard-ī rā ke raft dīdam. Only the latter is accepted in classical Persian and prescriptive grammarians such as Najafi still staunchly advise against the former form.Footnote 30 Another notable example is the third person singular form of the present perfect, in which the auxiliary ast is optional in formal modern Persian, i.e. both rafte and rafte ast are acceptable for “has gone.” Even though these count as valid examples, their scope of influence is too limited to compete with the morpho-syntactic flexibility of the classical language.

If we accept that the classical poetic language exhibits a considerably higher degree of linguistic flexibility in comparison to its modern counterpart, the question arising immediately is where this flexibility comes from and why it has for the most part disappeared in modern times. I argue that in the particular case of morpho-syntactic flexibility, the majority of the linguistic licenses discussed so far directly reflect the general linguistic properties of classical Persian (although they are presumably used at a higher rate in poetry compared to prose). In other words, as far as morpho-syntax is concerned, it is the written Persian language in general (in both poetry and prose) that had a flexible morpho-syntax initially and became more rigid over time. A brief overview of the history of New Persian can shed some light on the origins of this trend.

New Persian arose as a written language more than two centuries after the Arab conquest of Sassanian Persia in the seventh century CE. Like many other literary traditions, works in this tradition began to be written using slightly different phonological and morpho-syntactic standards by speakers of different dialects, and it took some time for them to converge towards a unified standard. The period of instability and standardization that continued until around 1500 (roughly the same time as the beginning of Safavid rule) was followed by centuries of linguistic stability.Footnote 31 Linguistic items that had multiple surface forms eventually converged towards one form throughout the history of New Persian.Footnote 32

As mentioned above, the dialectal diversity of early New Persian may have contributed to the availability of multiple forms for a single morpho-syntactic item.Footnote 33 Very little is known about the individual varieties of Persian spoken in different areas of the Persian-speaking world at the time. As a result, tracing the roots of different morpho-syntactic elements of this written language to different dialects is quite difficult, if not impossible. The extremely limited pieces of information that we have offer us at least one interesting example supporting our hypothesis. In a relatively famous commentary on the dialect of Persian spoken in Bukhara, the tenth century geographer Maqdisi mentions that there is a form of “repetition” in their tongue.Footnote 34 As an example, Maqdisi mentions the construction used in yek-ī mard-ī. As can be seen in example 16, this phrase uses three morphemes that indicate the number one or indefiniteness.

Even though Maqdisi finds this structure unusual and attributes it to the language of Bukhara, it seems that many poets, including Ferdowsi, Attar, and Rumi, have used this construction whenever metrical exigencies have obliged them to.Footnote 35 One may suggest that this is a case where a dialectal feature is used as a means of adding flexibility to the poetic language.

In addition to dialectal diversity, the prior history of the language may have had an effect too. A spoken language that is going through standardization as a written language can not only rely on constructions used in the everyday language of the people, but also on more archaic forms if they are still available to the community in some form. At the time when New Persian was being standardized, there were still people who were familiar with Middle Persian (many of the Middle Persian texts we have access to today were in fact written by members of the Zoroastrian community during the first few centuries after the Islamic conquest). Therefore, speakers may have been familiar with some Middle Persian morpho-syntactic structures, probably as marked linguistic forms.

A possible candidate for this category of linguistic forms is the placement of modifiers before nouns (e.g. bozorg mard for “great man”), which was the default practice in Middle Persian but was mostly superseded by the noun+ezafe+adj. construction in New Persian (e.g. mard-e bozorg). It seems reasonable to assume that this construction was considered more formal and archaic at the time and survived in the written standardized language as a marked variant, contributing to its flexibility.

To summarize, this period of instability and the presence of several competing dialects (possibly in combination with a residual influence of older written varieties of the language) may have been responsible for giving way to multiple variants of the same morpho-syntactic element in the standard written language. Under this scenario, the decrease in the use of alternative forms over time can be attributed to the gradual standardization process. Even in prose, as Lenepveu-Hotz has shown, the usage frequencies of the verbal prefixes be and mī underwent a long gradual shift, not reaching their current fixed forms until the fifteenth century.Footnote 36 Naturally, given the advantage these linguistic variations provide for the poet and the general tendency towards archaic language in poetry, they survived for a longer time in poetry, although they seem to be disappearing in modern times.

Changes in lexicon and phonology.

The flexibility of the classical poetic language is probably easier to observe in lexicon and phonology. A few of the lexical and phonological alternations directly reflect the alternations of the standard prose language of the era, similar to what we saw above with the morpho-syntactic alternations. For instance, the default form for the word “in” was initially andar in classical Persian prose and poetry, but dar soon took its place as the default form while andar too remained in use for a long time, especially in poetry. Similarly, for alternations such as that of shotor and oshtor (see above), in many cases both alternatives are found in mainstream prose of early New Persian.Footnote 37 Both forms of the third person singular pronoun (ū or vey) are also found in prose. In a comment that supports our earlier arguments, Lazard suggests that this variation originates from a dialectal difference.Footnote 38 For some items (omīd and ommīd for “hope”), directly learning about the default pronunciation in standard prose is difficult since the competing forms have identical spellings and therefore can be distinguished only in poetry where the meter of the poem reveals their pronunciations.

Unlike the items listed above, most of the lexical and phonological linguistic licenses—e.g. ze and z for az (“from”), gar and ar for agar (“if”), k for ke (“that”), etc.—are either absent in standard prose or have limited appearance and can be found almost exclusively in the earliest extant texts. Crucially, it is probable that none of these items must be viewed as “poetic contractions.” Evidence suggests that even the ones that are entirely absent from the standard prose of the era were indeed rooted in non-poetic language, as explained below.

The rise of the classical poetic language is simultaneous with the rise of New Persian as a written language. In fact, New Persian literature begins with poetry rather than prose.Footnote 39 Hence, the earliest examples of Persian poetry may reflect elements that are indeed closer to the non-standardized spoken versions of the language in comparison to prose. Some alternative pronunciations which were common at the time could find their way into the poetic language in the earliest days of New Persian poetry and stay there thanks to the metrically important purpose they served, but stopped short of entering the standard prose language.

For some of these items, we have independent historical evidence coming from early New Persian sources that do not belong to the mainstream body of Persian literature. One of the most important sources of this kind is the body of Judeo-Persian texts, which were written using the Hebrew script and often reflect dialectal features different from mainstream Persian texts of the era. Another valuable source is a translation of the Quran discovered in the 1960s in Mashhad, commonly referred to as Quran-e Qods. This translation, which is written in the Perso-Arabic script, shows dialectal features similar to the Judeo-Persian texts and quite different from other extant New Persian documents.

The preposition az (“from”) appears as z before vowels on many occasions in Quran-e Qods. Examples include z-īshān for “from them,” z-ān for “from it,” and z-īmā for “from us” (the free form of the first person plural pronoun is īmā in Quran-e Qods). It also occasionally appears as ze (written as the Persian letter “z,” ز) before consonants, e.g. ze kūh for “from the mountain.” The development of ze from az seems to have been a two-step natural phonological process.Footnote 40 Similarly, the word ke often appears as k when preceding the vowel-initial word īshān (“they”) in Quran-e Qods, i.e. k-īshān instead of ke īshān.

The use of ar instead of agar is abundant in Quran-e Qods, as Lazard has pointed out too.Footnote 41 Both alternative forms of this word (gar and ar) are occasionally observed in other early New Persian texts such as Tafsir-e Surābādi and Hidāyat-al Mutaʿallimīn as well.Footnote 42 Moreover, Lazard mentions examples in these texts where this word is connected to a preceding va (“and”), producing the contracted form var (see above).

Some of the phonological alternation patterns introduced above can be observed in these early works. Replacing ō (pronounced today as ū in Iranian Persian) with o (e.g. goroh) can be seen occasionally in the earliest works of mainstream New Persian prose,Footnote 43 as well as Quran-e Qods.Footnote 44

Replacing ā with a before h (e.g. gonah instead of gonāh for “sin”) has always been relatively common in mainstream Persian prose for certain morphemes such as negāh (“watch”) as well as in certain compound nouns (even in contemporary Persian), e.g. mahtāb (“moonlight”), tabahkār (“criminal”). However, its use in other contexts is quite rare in prose and almost limited to non-mainstream sources such as Quran-e Qods Footnote 45 and Judeo-Persian texts.Footnote 46 A few occurrences have also been reported from mainstream prose of early New Persian by Lazard.Footnote 47

The alternation between cho and chūn (“when,” “after”) is also rooted in non-poetic language. Even though the default form in prose is chūn, Lazard mentions many cases of the use of cho in early New Persian prose.Footnote 48

For the use of enclitic pronouns without a preceding vowel, (e.g. -tān instead of -etān) the Perso-Arabic script conceals the distinction, but in Judeo-Persian texts the vowel-less form (which is the less common form in Persian poetry) is in fact the default form for -mān, -tān, and -shān.Footnote 49

To summarize, these historical data suggest that the classical poetic language took advantage of the dialectal diversity of Persian before its standardization in prose and developed a language that was more flexible than the prose language and thus more suitable for metrical poetry. This puts the lexical and phonological linguistic licenses in contrast with the morpho-syntactic licenses, which, as explained earlier, existed in both prose and poetry.

As we saw in Table 2, the use of these linguistic licenses in Persian poetry has decreased over time. This could be attributed to two factors. First, it is likely that as time passes and the prose language becomes more widespread and established (note that, as mentioned earlier, in the early days of New Persian poetry was at least as important as prose but the situation changed as Persian gradually found de facto official status), the standard is determined by the prose language rather than the poetic language and consequently forms that have not found their way into the prose language are increasingly judged as marked by speakers. Moreover, speakers not only find these alternative forms marked, but associate them in particular with an elevated and archaic style that is only suitable for the narrow range of topics that are already common in classical poetry. As a result, to many speakers, these forms begin to sound disharmonious in the vicinity of more recent linguistic forms.

In today’s Persian, many words, collocations, and structures belonging to the contemporary language exclusively and (at least believed to be) non-existent in classical Persian do appear in contemporary poetry. In the first two verses of a ghazal by contemporary poet Fatemeh Ekhtesari, for example, we can see multiple such items: mesle (“like”), kāfe (“café”), vābastegī (“dependence”), botri (“bottle”), and kherkhere (“throat”).Footnote 50 It seems safe to say that speakers generally find it odd and even slightly absurd to see such words next to “archaic” forms such as ze, gar, degar, cho, etc. Thus, the association of these alternative forms with the archaic language results in them falling out of use in poems that use a more up-to-date language or revolve around more modern topics.

Changes in the occurrence of scrambling.

Unlike the two categories of linguistic licenses discussed so far, scrambling still has a strong presence in the poetic language of contemporary Persian in spite of its relative decline (see Table 2). Moreover, it is the only category for which the frequency does not decrease during the transition from classical poetry to Safavid poetry (in fact it shows a slight increase in our data, although the difference is not statistically significant).

Scrambling is not particularly common in mainstream Persian prose, be it modern or classical. In spoken language, on the other hand, scrambling is still quite frequent.Footnote 51 Moreover, as Lazard argues, it appears that scrambling was common in the earliest attested examples of Persian prose where the style is perceived as particularly archaic and highly influenced by Arabic.Footnote 52

If we take the prevalence of scrambling in the earliest instances of Persian prose seriously and interpret it as a reflection of the language of the era (rather than a limited artificial effect caused by the influence of Arabic in translated works), we may conclude that scrambling in poetry, similar to the lexical and phonological variations discussed earlier, was a characteristic of early New Persian which did not survive in standard prose but persisted in the poetic language presumably because of the convenience it offered in the production of metrical material. Under this scenario, the gradual decrease in the use of scrambling in poetry can be explained similarly to the other categories of linguistic flexibility: as the language evolved and became standardized, the use of these “archaic” forms became less acceptable.

On the other hand, if this is not the case, then the decrease in the occurrence of scrambling in Persian poetry in modern times is likely to have stylistic—rather than purely linguistic—reasons. It is difficult to pin down the factors that may have given rise to this change of attitude on the part of poets. One could hypothesize that it was due to a general tendency towards some notion of perfection which is also responsible for a decrease in the use of poetic licenses in Persian poetry over the centuries. I do not discuss this issue further in this paper as it falls outside the scope of linguistic change in its strict sense.

The Future of Metrical Persian Poetry

So far, it has been argued that the rigidity imposed by metrical requirements in classical Persian poetry was compensated for by linguistic flexibility. It was then shown that this linguistic flexibility has decreased during the more than ten centuries since the beginning of poetry in New Persian. As argued earlier, the role of this linguistic flexibility in the success of classical Persian poetry seems to have been substantial, as poets like Hafez and Saʿdi used at least 1.9 linguistic licenses per beyt in their poetry. Crucially, this number fails to cover many of the linguistic licenses and does not reflect the effect of the short length of some of the available alternative forms (e.g. ravad in place of mīravad and z in place of az) which has a considerable effect in facilitating metrical composition. In the light of these facts, one can argue that with a decrease in linguistic flexibility and the general absence of metrical flexibility, metrical Persian poetry (at least in its traditional form) may be facing a linguistic crisis. Composing poems that meet all metrical and linguistic standards seems more difficult than ever, suggesting that other sources of flexibility need to be sought.

Recent trends in Persian poetry have indeed sought such new sources of flexibility. Probably the most prominent example is sheʿr-e now, in which the metrical requirements are relaxed by giving the poet freedom in the number of metra used per verse.Footnote 53 In the works of some sheʿr-e now poets such as Forough Farrokhzad, the range of poetic licenses used is even broader.Footnote 54 One may also argue that the introduction of new meters in the works of contemporary poets such as Simin Behbahani contributes to the relaxation of metrical requirements. This might be true to some extent, but it must be noted that the main restrictive force of the Persian metrical system does not stem from the size of the metrical inventory (which is relatively large in any case, with over a hundred attested meters),Footnote 55 but from the limitations imposed within each individual meter.

Another recent literary trend that circumvents the problem to a great extent is using colloquial Persian as the language of metrical poetry. A new wave of professional poetry in colloquial Persian emerged in modern times. This tradition is distinct from the genre commonly known as “folk poetry” in that it is usually produced by professional poets, uses a more sophisticated language, and has recently started to target a broader range of topics. In its early days during the first half of the twentieth century, professional colloquial Persian poetry was mostly limited to political satire, e.g. the works of Ashrafeddin Hosseini—commonly known as Nasim-e shomāl—and Mohammad Ali Afrashteh. Later, with the spread of pop music and the emergence of professional lyricists such as Iraj Jannati Atayi, Shahyar Ghanbari, and (a few decades later) Maryam Heydarzadeh, metrical poetry in colloquial Persian became more diverse in topic and started to develop an increasingly complex and metaphorical language. At the same time, well-known poets from the world of formal Persian poetry composed influential works in colloquial Persian, most notably Pariā (“the fairies”) by Ahmad Shamlou and Be ali goft mādarash ruzi (“Once upon a time, Ali’s mother told him…”) by Forough Farrokhzad. Later, some lyricists started publishing their works as independent works of poetry. Many of these published poems are read but never actually sung in musical compositions.

Let us now briefly discuss what makes colloquial Persian poetry more flexible than its formal counterpart. On the metrical side, the correspondence between syllables and metrical patterns is laxer in this tradition as the traditionally “long” vowels are allowed to be treated as either short or long at any position.Footnote 56 On the linguistic side, the main advantage of the colloquial language (at least the Tehrani variety which is the focus of our attention) is the availability of shorter forms, especially for present simple verbs. The copula “is” is e rather than ast in colloquial Persian. The verb endings for third person singular and plural verbs in the present are -e and -an instead of formal Persian -ad and -and, and, more importantly, the present stems of most common verbs are considerably shorter than their formal variants, e.g. formal gu(y) vs. colloquial g (“to say”), formal row vs. colloquial r (“to go”), formal khāh vs. colloquial khā (“to want”), formal neshin vs. colloquial shin (“to sit”), formal dah vs. colloquial d (“to give”). Thus, for instance, the equivalent of the verb mīgūyad (“says”) in colloquial Persian is mīge. While the syllable sequence of the former is HHH (six morae), the latter is HL (three morae), which, under the metrical correspondence rules of colloquial Persian, can be treated as LL too (see above).

There are also other factors contributing to the linguistic flexibility of colloquial Persian. Probably because of its intermediate position between a spoken and a written language and its relatively high degree of susceptibility to influence from dialectal variation, several morpho-syntactic items have more than one possible realization in colloquial Persian. For instance, the use of a verb ending esh for third person singular verbs in the past is optional, e.g. raft and raftesh for “went”. Similarly, an object agreement clitic after the verb is optional in colloquial Persian, e.g. moʿallemā ro dīdam or moʿallemā ro dīdam-eshūn for “I saw the teachers.” As a third example, pronouns that follow prepositions can appear not only in their free form (as they do in formal Persian) but also as clitics, e.g. az to or azat for “from you.”

In addition to the cases introduced above, an important source of variation in colloquial Persian is that many morphemes are also allowed to appear in their formal form in colloquial contexts. For instance, in a colloquial Persian poem, the pluralizing suffix following a consonant can either be the purely colloquial -ā or the formal -hā for many (but not all) words, e.g. shabhā or shabā (“nights”). Similarly, the word meaning “also” can appear as either ham (the formal version) or am (the purely colloquial version) following a consonant in most cases. Many free morphemes allow similar variations. In the first twenty lines of Forough Farrokhzad’s colloquial poem Be ali goft mādarash ruzi, for instance, seven words out of the total eighty-five have more than one possible form in colloquial contexts (in each pair the first one is the one used in the actual poem): bune or bahune (“excuse”), cheshm or chesh (“eye”), das or dast (“hand”), ye or yek (“one”), ru or ruye (“on”), do-tā or dot-tā (“two”), hamchi or hamchin (“somewhat”).

The linguistic flexibility of colloquial Persian, which probably stems from its dynamic nature as a spoken and non-standardized language, is reminiscent of the situation of the formative years of classical Persian poetry. If the analyses presented in this paper are on the right track, one can argue that colloquial Persian is a more flexible language for almost the same reasons as those that once made classical New Persian a suitable language for metrical poetry.

Obviously, many factors other than linguistic flexibility are decisive in determining whether or not a language or dialect is selected for poetry. All that can be said in light of the above discussion is that to the extent that linguistic and metrical rigidity are serious problems for contemporary Persian poetry, shifting towards the colloquial register may be beneficial in this particular respect.

To summarize, Persian poetry seems to be confronted with three choices: continuing the classical tradition in spite of the ever-increasing rigidity of the formal poetic language, shifting towards more relaxed standards in meter and rhyme such as those of sheʿr-e now, and using a more dynamic and flexible variant of the language, i.e. colloquial Persian. As recent history has shown, all possibilities are naturally experimented with. Obviously, the answer to the question of which one eventually prevails is dependent on a large number of non-linguistic factors.