Introduction

Fertility in Iran, after falling steadily for twenty-five years, started rising slightly between 2012 and 2016, before falling again at a faster pace. At first glance, this slight increase in fertility might appear to place Iran alongside Algeria (which rose from 2.2 children per woman in 2002 to 3.0 children in 2014)Footnote 1 and Egypt (from 3.1 children per woman in 2003–05 to 3.5 in 2012–14),Footnote 2 where, after falling for three decades—a drop viewed by these authors in all likelihood attributable to the rise in age at marriage—fertility started moving upwards. Especially as the large generations born in Iran in the 1980s have reached the age of marriage and procreation over the course of the past decade. However, Iran differs from these two countries in that, in 2010, the state reversed the neo-Malthusian policy it had introduced in December 1989, and opted for a new population policy which may be unhesitatingly described as populationist. Indeed, it was a matter of deploying all means possible to reverse changes in fertility, and especially to reach a target population of 150 million people,Footnote 3 though within an unspecified timeframe. The supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, gave his personal support to this policy, enjoining the authorities to reconsider the policy of birth control, and calling on the clergy, with the assistance of the media, to employ all means possible to alert public opinion to the importance of this matter. In May 2014, deciding it was time to shift up a gear, the supreme leader drew up a strategic program set out in a decree of fourteen articles, called “General Policies for the Population,” enacting the state’s new population policy, and instructed the three powers of the legislative, the executive, and the judiciary to implement it.

Despite all these measures, fertility, after increasing slightly for four consecutive years, has started to fall. So, what factors drove this short-lived uptick in fertility in Iran? In an attempt to provide some basis for responding to this question, this paper examines changes in fertility from 1967 to 2019. This analysis is supplemented by study of the main determinants of fertility to better pinpoint recent changes in fertility. To explain this trend, it then analyzes the Islamic Republic’s new population policy, the scale and singularity of the measures taken not only to drive up fertility, but above all to influence the growth, composition, and distribution of Iran’s population.

Changes in Fertility since 1967

Under the monarchy, the fertility of Iranian women was particularly high (Figure 1). According to our estimates based on adjusted birth data,Footnote 4 in 1967 each woman gave birth to 7.8 children on average.Footnote 5 This fertility rate then fell very slowly to a level of 6.8 in 1979. Thus, during the 1960s and 1970s, contrary to widespread opinion, demographic behaviors did not change rapidly.Footnote 6 The delayed socioeconomic development of the country had widely contributed to the preservation of traditional values. In accordance with the patriarchal traditions, the high level of fertility constituted a social norm, and women who had already been relegated to an inferior position because of their gender were at their spouses’ service, and had to bear several children in order to raise big families. Fertility, then, was a guarantee allowing a woman to prolong her conjugal life, just as procreation and raising her children, by and large, constituted the entirety of the role of a woman and the source of her identity, without which she would be marginalized. The influence of these traditions was so important that the first family planning program, implemented in 1967 (discussed later), despite substantial financial support and the involvement of several ministerial organizations, did not actually succeed.

Figure 1. Change in the number of births and total fertility rates (TFR) in Iran since 1967.

Sources: Iranian civil registry organization and decennial censuses from 1966 to 2016 (Statistical Center of Iran); TFR: estimation by Marie Ladier-Fouladi using indirect methods.

After the revolution, the Islamic Republic dropped its birth limitation campaigns and acted swiftly to abolish the law legalizing abortion.Footnote 7 The first of these steps was justified on political grounds, the second on religious grounds. Indeed, family planning was considered by the new rulers as a project by “imperialists” to curb the developing countries’ dynamism and thereby further their own interests. Nevertheless, the Islamic state did not forbid the use of contraceptives,Footnote 8 which were clearly authorized in a fatwa issued by Ayatollah Khomeini in September 1979.Footnote 9

In spite of the fact that there were no birth control campaigns, the total fertility rate, after a short period of stability between 1979 and 1985, took a very rapid downward course: dropping from 6.4 children per woman in 1986 to 5.3 in 1989 (a decline of 1.1 children in the space of only three years). However paradoxical this may seem, the fertility transition in Iran began under the Islamic Republic despite the political speeches and the gender-biased Sharia laws.

Let us pinpoint that the Iraq–Iran war (1980–88), contrary to what one might think, did not have a significant effect on the decline in fertility. First of all because the Islamic Republic did not issue a decree of general mobilization and only the young single people conscripted for military service (twenty-seven months for those carrying out military service in the combat zones and thirty months for the others) and volunteers of all ages (supervised by the Pasdaran)Footnote 10 were sent to the front. Moreover, married volunteers were given a 15-day leave every three monthsFootnote 11. Finally, the conflict affected the civilian population only marginally. The victims were mainly combatants aged 18-25, of urban and origin alike. Most of the fighting took place in the western and south-western border regions, which were deserted by the population.Footnote 12

In December 1989 the Islamic Republic altered its position and adopted an energetic population policy (discussed later). Given women’s motivation to control their fertility, the Iranian state’s second population policy was, unlike the first, very favorably received and accelerated the drop in fertility. The most spectacular decrease occurred between 1986 (6.4 children) and 2003 (2 children), amounting to a decrease of nearly 70% in the space of 17 years, making the Iranian demographic transition one of the most rapid in history. But it should immediately be pointed out that the fall in fertility started prior to the energetic resumption of family planning by the Islamic Republic. Thus, we should not make the mistake and assume that the fertility transition has its origin in the Family Planning of the Islamic Republic. Fertility had already dropped by 1.7 children between 1978 and 1989. In fact, the scale of the decrease in the 1990s was primarily attributable to women. The family planning means provided by the Islamic Republic merely made it easier to act on their choice. The theocratic state simply supported women in their plans. But by creating the conditions for their success, it undeniably accelerated this downward trend in fertility.

Iranian women’s motivation to control their fertility reflects a global change in society, working against a context that was highly favorable to reviving or maintaining the traditional values favored by the theocratic state, and charting a new course fundamentally redefining the situation for women. This was especially because women, by playing a massive part alongside men in the revolutionary events, had become aware of their true position in the private and public sphere. It may even be supposed that in controlling their fertility women continued their own revolution. Thus, between 2004 and 2012, fertility remained at a very low level (around 1.9 children per woman on average).

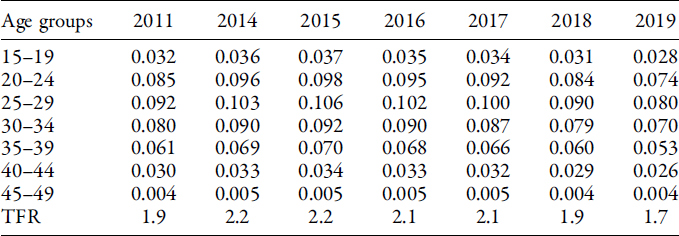

As of this latter date, the trend in fertility started going into reverse, rising from 1.9 children on average per woman in 2011 to 2.2 in 2015, and then falling back to 1.9 children in 2018 and to 1.7 in 2019 (Table 1). At first sight this rise might seem attributable to the arrival of the large generations born in the 1980s, who reached the age for marriage and procreation during this period. However, given the very serious economic crisis, structural problems in the Iranian economy based on extracting oil revenues, galloping inflation, difficulty in finding employment (especially for young graduates), and the high cost of accommodation in towns, it would have been logical for the generations to delay marriage and/or, at the very least, put off having their first child. This is confirmed by studies looking at the drop in fertility in Iran whose analysis is based on the synthetic parity progression ratio method.Footnote 13 The fairly low fertility rates of generations born between 1977 and 1991, aged between fifteen and twenty-nine in 2006, fit the forecasts of these three studies.

Table 1. Adjusted general fertility rates (whole country).

Sources: Iranian Civil Registry Organization and General Population Censuses from 1966 to 2016, Statistical Center of Iran; TFR: estimation by Marie Ladier-Fouladi using indirect methods.

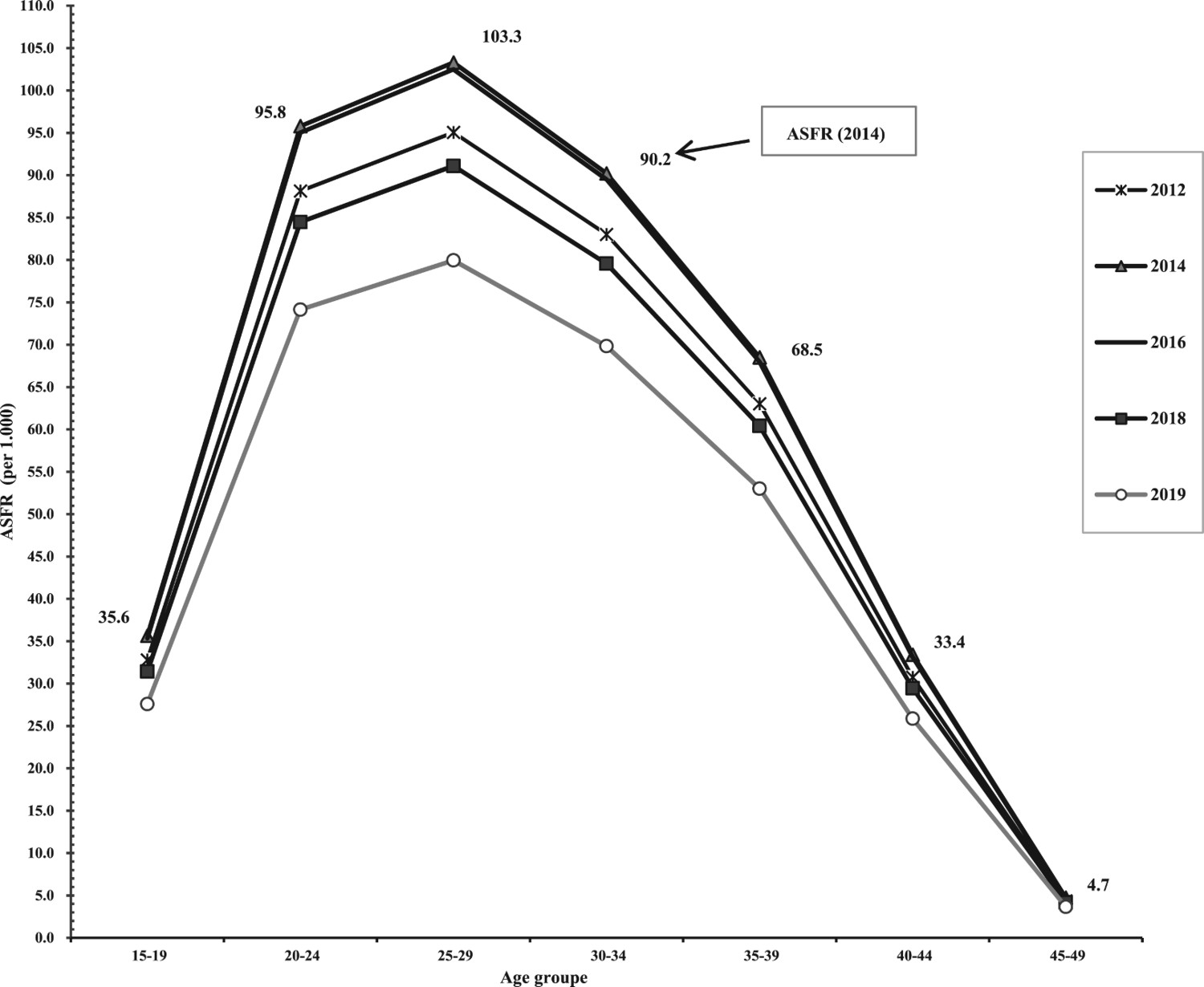

Furthermore, analysis of fertility rates by age group between 2011 and 2016 shows that fertility increased across all ages (Figure 2). Nevertheless, the increase in fertility among women aged 25–29 in 2016 (the generations born in 1987–91) would appear to be higher than among women of the same ages in 2012. And these generations were those driving sociocultural change in Iran during the 2000s.Footnote 14 In the same way, fertility declined across all ages, yet in 2019 the decrease in fertility is more significant among women aged 25–29, 30-–34, and 35–39.

Figure 2. Age-specific fertility rates (whole country).

Sources: Iranian civil registry organization and general population censuses from 1976 to 2016 (Statistical Center of Iran); ASFR: estimation by Marie Ladier-Fouladi using indirect methods.

So, what factors contributed to the rise and then fall in fertility? It is generally accepted that social, cultural, and economic progress indirectly influences fertility. In order to answer this question, it therefore seems important to examine fertility trends in Iran in the light of developments in these fields over the past forty years. To do so, a number of proximate determinants (age at first marriage, contraception, breastfeeding, abortion) can be analyzed, which are in turn dependent on more “remote” socioeconomic determinants (infant mortality, literacy, labor force participation, urbanization, etc.) Because of data restrictions, we shall consider here only the factors that are most meaningful in terms of fertility.

Women’s age at first marriage

Age at marriage is a factor that is particularly important in societies where fertility outside marriage is non-existent. In the absence of annual data about marriages by age, the only way to estimate mean age at marriage is based on the proportions of single women (having never married) by age, as counted during decennial censuses. While this provides indications about changes in age at first marriage, the data is not such as to allow sufficiently detailed examination to apprehend this trend. For this reason, this analysis is supplemented by analysis of changes in recorded marriages and divorces, focusing on the large generations born in the 1980s.

Although the Islamic Republic lowered the minimum legal age at which women may marry,Footnote 15 the mean age of women at first marriage kept rising, due to staying in education for longer and the modernization of family aspirations. It rose from 19.7 years in 1976 to 24.0 years in 2016 (Table 2). Being a national mean, the figure was in fact even higher in cities, where it exceeded twenty-five years of age. Especially as nowadays, primarily in Iranian great cities, a new category of couple is appearing, in which a young unmarried woman and a young unmarried man cohabit, as is widespread in the western world.Footnote 16

Table 2. Female proportions single and mean age at first marriage: urban and rural.

Sources: General Population and Housing Censuses of 1976, 1986, 1996, 2006 and 2016, Statistical Center of Iran.

However, we observe that the proportion of single women aged fifteen to twenty-four in urban sectors and aged fifteen to twenty-nine in rural sectors, after steadily rising for three decades, dropped from 2006 to 2016. This may be explained in part by the impact of state campaigns promoting marriage at very young ages (discussed later). In rural sectors, the mean age of women at first marriage fell by over a year, from 23.8 years in 2006 to 22.7 years in 2016. These young women may have been more receptive to these campaigns, especially as in 2006 the proportions of single women aged 25–29 peaked at a higher level in rural sectors, at 26.5 percent, than in urban sectors, at 22.7 percent.

To check the impact of state campaigns promoting marriage at very young ages, we now look at changes in marriages recorded in the civil registry. It should be stated that since the 1980s civil registers provide complete coverage of marriages and divorces.Footnote 17

The large generations born in the 1980s reached the age of marriage in the mid-2000s, and there is an observable slight increase in the marriage rate between 2005 and 2011 (Figure 3). Subsequently, the marriage rate started dropping rapidly, from 10.9per thousand persons in 2012 to 6.7per thousand persons in 2018. Conversely, the divorce rate started rising again as of 2006, from 12.1 per 100 marriages in 2006 to 31.9 per 100 marriages in 2018 (Figure 4). Due to a lack of appropriate statistical data, particularly regarding data about marriages by single year of age, it is not possible to go further in the analysis and check our hypothesis.

Figure 3. The crude marriage rate per 1,000 population (whole country).

Sources: General Population Censuses from 1976 to 2016. Statistical Center of Iran and Iranian Vital Registration Organization.Footnote 18

Figure 4. Number of divorces per 100 marriages (whole country).

Source: Iranian Vital Registration Organization.

Insofar as the change in marriages and divorces, particularly over the past ten years, contrasts with the upwards trend in fertility, it may be deduced that the rise in fertility is mainly for couples who are already married.

Contraceptive practices. For the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, contraceptive use can only be estimated from the Family Planning Service statistics. These do not include women using traditional methods of contraception and those who procure contraceptives on the open market. A family planning program was implemented by the government in April 1967, when an ad hoc department was created within the Health Ministry.Footnote 18 The government measures stipulated that several ministerial organizations, as well as a section of conscripts (sepahe behdasht, the health army), were to help this department achieve its principal goal: to reduce the number of births. However tradition held such sway at this time that the monarchical government’s family planning policy (1967–77) failed to meet its minimum targets.Footnote 19 It consisted in attracting at least 500,000 women between 1968 and 1972 to practice contraception on a regular basis. But in May 1970, the results of a new study on the demographic situation indicated an average number of seven children per woman, a birth rate of 48 per thousand people and a mortality rate of 16 per thousand population.Footnote 20 According to the same source, the vast majority of women did not consult for family planning until they already had a large family: thus they were stoppers rather than spacers. Moreover, the same source found that through unfamiliarity with modern contraceptives, ignorance, or fatalism women went beyond their preferred family size (which was three to five children depending on socioeconomic category). According to another survey conducted in 1971 in Isfahan, the mean age of acceptors was thirty-two and they had five children on average, while four was the preferred family size.Footnote 21 It should be stressed that in Iran (as other developing countries), the road to family planning has encountered many other obstacles: the lack of facilities and trained personnel, cultural traditions, etc. The legalization of abortion in 1976 in spite of the opposition of some religious leaders suggests, furthermore, that the first years of the operation of family planning were not satisfactory ones.Footnote 22 Regardless of these obstacles, the government opted for a proactive change in its population policy to bring the annual growth rate down to 1 percent within the space of twenty years.

Despite having considerable financial means (the budget allocated to family planning rose from $500,000 in 1968 to $15 million in 1974), only 11percent of married women between the ages of fifteen and forty-four followed a birth control program in 1977,Footnote 23 the last year the policy was in operation.Footnote 24 Under these conditions, fertility only dropped very slowly, and, on the eve of the 1979 revolution, each woman was still giving birth to seven children on average.Footnote 25

As mentioned earlier, after the Islamic Republic was established in 1979, birth limitation campaigns were halted, but dispensaries and health centers continued to distribute contraceptives free of charge,Footnote 26 even though the choice was limited due to the introduction of austerity measures in the wake of an economic embargo against Iran and the high cost of the Iraq–Iran war (1980–88). Contraceptives were also on sale in pharmacies at affordable prices. Additionally, the health centers (khaheh behdâsht) set up in rural areas as of 1982, one of whose missions was to look after the health of mothers and children, played a crucial role in distributing information and raising awareness about contraception.

In fact this period was notable for the lack of any coherent population policy. However, this did not prevent fertility dropping again. After briefly stabilizing (1979–85), the figure started going back into decline as of 1986, falling more rapidly than before. Within the space of three years, between 1986 and 1989, and despite the absence of any birth limitation campaign, the fertility rate dropped by 1.1 children.

According to family planning statistics, the number of requests for contraceptives received by dispensaries, often by women from a modest background, kept on rising.Footnote 27 No information is available about the age, motive, or number of children of mothers who contacted planning family centers. However, the upward trend in the number requesting contraceptives indicates that an increasing number of women were motivated to control their fertility.Footnote 28

At the end of the war (in August 1988), the Islamic Republic, which was supposedly pronatalist, committed itself to a policy overtly in favor of birth control.Footnote 29 On 7 November 1988, Ayatollah Khomeini in his “Charter of Brotherhood” spoke of the necessity of discussing “the stand to be taken relative to family planning: should family limitation be encouraged or only birth spacing?”Footnote 30 A media campaign was then launched to explain why the implementation of family planning was essential. Religious guides and experts were also questioned and the opinions of a number of them, in favor of or in opposition to birth control, were widely circulated in the newspapers.Footnote 31 Finally, on 14 December 1988, Hojjat-ol eslâm Moghtadaï, the spokesman for the High Judicial Council and a member of the Association of Teachers of Muslim Law at the theological school of Qom, solemnly announced that, from the point of view of Islam, there were no obstacles to family planning.Footnote 32 At the beginning of 1989, the Ministry of Health, Hygiene and Medical Education (MHHME) was invited to expand its Family Planning Department in order to steer the new population policy aimed at reducing the annual growth rate from 3.2 to 2.3 percent in the space of twenty years.Footnote 33

The MHHME requested the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) to help it meet its needs for maternal and child health services as well as family planning.Footnote 34 Before putting its program in place, in 1989 the Ministry of Health conducted a KAP (knowledge, attitude, and practice) survey on 9,000 married women aged 15–44. According to the results, 28 percent of women (31percent in the towns and 21percent in the countryside) used modern means of contraception (oral contraceptive, condom, Intra Uterine Device ‘IUD’) and 22 percent (31percent in cities and 10percent in villages) used a traditional contraceptive (rhythm or periodic abstinence, withdrawal, breastfeeding, postcoital douche); that is, 50percent of women (64percent in towns and 31percent in the countryside) were using either modern or traditional methods of contraception.Footnote 35 These percentages of contraceptive users during a period when there was no active family planning program (1980–89) reveal that the women were already motivated to control their fertility. Let us recall that the decline in fertility had started already in 1986, a full three years before the family planning program was adopted by the Islamic Republic in December 1989.

In 1991, two years after an extremely active family planning programs policy had been implemented, a new KAP survey, conducted once again by the Ministry of Health, showed that 45percent of these married women aged 15–44 were current users of a modern contraceptive method (pill, condom, tubal ligation, or IUD). This sharp rise is mainly due to rural women (42 percent) who have now drawn very close to urban users (47percent). So sharp a progression in the space of only three years highlights the motivation of women. The conditions that work in favor of birth control—social, cultural, and economic developments—existed before the government took its stand and officially supported family planning. The new policy merely fell into step with a movement that was already under way and, by smoothing the route, accelerated the decline in fertility.Footnote 36

According to the results of the IDHS survey, in 2000 nearly 74percent of married women aged 15–49 used a contraceptive, with 56percent using a modern contraceptive and 18percent a traditional contraceptive.Footnote 37 The IDHS survey for 2010 found the proportion of women using modern contraceptives unchanged at 56 percent.Footnote 38 Additionally, according to the results of this same 2010 survey, the use of contraceptives increased with age. The lowest contraceptive usage was found among married women under twenty while married women aged 20–29 were opting for reliable and reversible methods.

As of 2012, family planning centers started cutting back the contraceptives they offered, before withdrawing all contraceptives in 2013 (discussed later). Obviously, putting an end to the free distribution of contraceptives, especially by health centers in rural and peripheral zones, together with the closing of information programs, had a significant impact on women’s fertility. Admittedly, contraceptives were still available in pharmacies, particularly in towns, but given the serious economic crisis, the spiraling cost of all products, and the development of an informal market in medicines, it may be readily imagined that contraceptives were on sale at prices that far exceeded what poor families could afford. It is most likely that these circumstances have led to an increase in unintended pregnancies and hence to an increase in unwanted births, not to mention the health problems that women from disadvantaged classes encountered in controlling their fertility, especially as in Iran, it will be remembered, abortion is forbidden except in the event of therapeutic abortion on grounds certified by three doctors.

Women’s education

The social keystone of this important transformation was unquestionably the progress in young women’s schooling starting in the 1980s. As a result of the policy of the monarchic government that privileged the large cities at the expense of the rural and peripheral regions, an important part of the population, in particular women, could not gain access to education. According to the General Population and Housing Census, in 1966, among women of reproductive age (15–49) only 15 percent were literate (34 percent in urban and 2 percent in rural areas). Ten years later, in 1976, a large majority of women aged 15–49 remained illiterate.Footnote 39 The literacy rate of women aged 15–49 was 28 percent (50 percent in urban and 8 percent in rural areas). Given that an inverted relationship has frequently been observed between fertility and female literacy levels—i.e. the higher the latter, the lower the former— the low level of women’s education accounts for the high level of their fertility during 1960s and 1970s.

Following the revolution, despite shortcomings in the organization of schooling and literacy, especially in the early 1980s, the expansion of education was particularly beneficial to women, whose access to schools rose at an accelerated pace. Thus female literacy rates rose constantly, from 49percent of women aged 15–49 (65 percent in urban and 27 percent in rural areas) in 1986, to 87.4 percent (92.1 percent in urban and 76.5 percent in rural areas) in 2006 and finally up to 92.7 percent (95.4 percent in urban and 84.5 percent in rural areas) in 2016.Footnote 40

Most important is the significant increase in the educational achievement of women aged 15–49. In 1976, only 8.7percent of them had completed secondary education (16.7 percent in cities and 1percent in rural areas) and 1.5percent had succeeded in pursuing their studies at university level (2.9 percent in urban areas and 0.1 percent in rural areas). In 2016, 37.6 percent of women aged 15–49 had graduated from secondary school (39.5percent in the urban sector and 31.3percent in the rural sector), but more noticeable is that 28.9percent of them (33.8percent in cities and 11.5percent in rural area) earned a university degree.

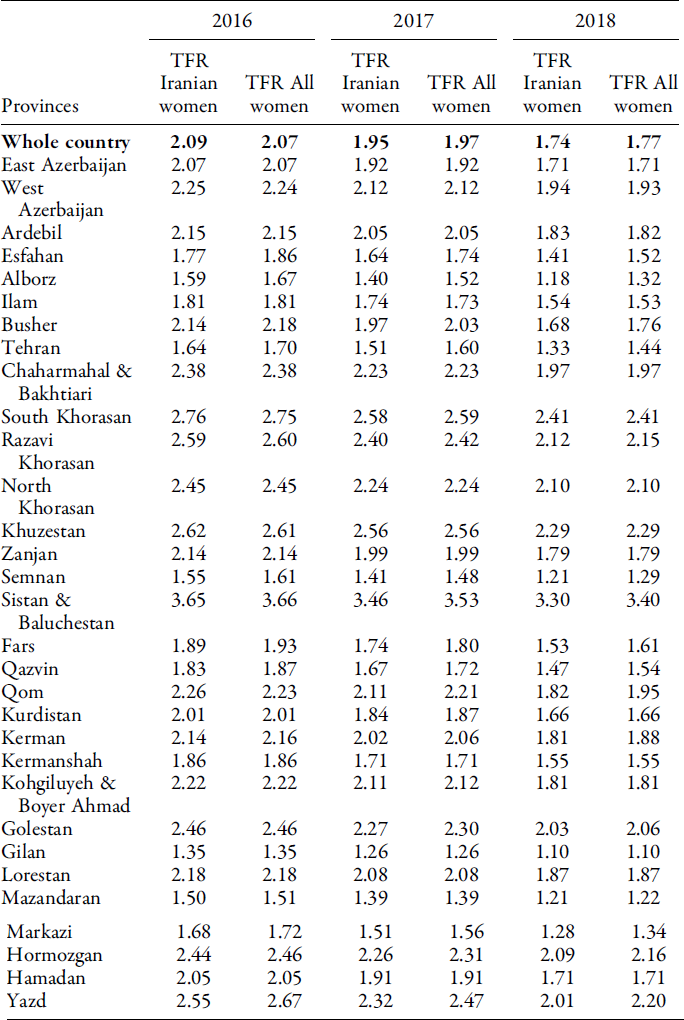

The indisputable progress of women’s schooling reveals the profound transformation of Iranian society. It is one of the main causes of demographic change, particularly regarding the increase in age at first marriage and the decline in fertility in recent decades.Footnote 41 The reversal of fertility trends is thus in contradiction with such a socio-cultural context where the predominant family model is that of the small nuclear family (one to three children) that now prevails among all social strata in all regions (Table 3).

Table 3. Total fertility rates in Iran: all women and Iranian women, by province

Source: Elham Fathi, Prospects for Fertility in Iran from 2016 to 2018 (Tchashm andazi bar barvari dar iran az sal-e 1395 ta 1398). Tehran: Statistical Center of Iran, 2019, p. 14.

TFR: estimation by Elham Fathi using direct methods.

Implementation of a Populationist Policy

The slight increase in fertility may thus be explained by the Islamic Republic’s ambitious new population policy, which we shall now examine. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (the president of Iran from 2005 to 2013) was the first to question the Islamic Republic’s neo-Malthusian policy, declaring to parliament in December 2006: “two children are not enough, Iran’s population needs to reach 120 million people.”Footnote 42 This declaration triggered lively public debate, including on television. Demographers and economists in particular were opposed to this policy, pointing out the socioeconomic consequences that might stem from rapid demographic growth. Faced with these criticisms, and in the absence of the supreme leader’s public support on this point, Ahmadinejad preferred not to insist, especially as he had to devote his energy to another issue, of equal importance for his populist policy and his regional ambitions, namely the resumption of the nuclear program.

After being controversially reelected in June 2009, with the firm backing of the supreme leader, he resumed his offensive against the birth control policy, and in April 2010 declared in a TV interview that “our country has the capacity to reach a population of 150 million people.”Footnote 43 Somewhat surprisingly, he did not hesitate to target clerics, indirectly criticizing their silence on the subject of birth limitations. Since it was Khomeini who gave his approval for the implementation of family planning, the clerics did not approve of Ahmadinejad’s position. It was not until the intervention of Khamene’i in 2011, who clearly gave the green light to adopt the new population policy in order to increase the number of births, that they finally accepted this turnaround.

In September 2009, Ahmadinejad had taken the specific measure of creating a savings plan (an investment account) called the “Fund for the Future of Our Children.” The government would pay 1 million touman (the equivalent of €559 in 2010) into each account opened for all newborns as of 21 March 2010 (the first day in the Iranian calendar). Payments into this fund were to continue up until the child’s eighteenth birthday, on the one hand by the government regularly contributing the equivalent of €67 per year, and on the other by the parents, who the government encouraged to pay in the equivalent of €13 monthly.Footnote 44 Admittedly, this project ran into opposition from MPs opposed to this expensive measure, who cut it from the 2011 government budget. But the point to note here is Ahmadinejad’s firm intention to deploy such means to reverse the trend in fertility. He was also behind other measures to counter the demographic policy in place.

Incentives

Encouraging Iranians to marry and start families very young

In autumn 2009, Ahmadinejad decided to take major steps to accelerate the application of a law called the “law to facilitate the marriage of young people,” passed at the beginning of his first term in 2005. While this law was intended to facilitate marriage for young people in general, he expressly recommended marriage at a young age during a November 2010 meeting in tribute to the “actors and benefactors of marriage,” declaring: “for me, the ideal age for women to marry is between 16 and 18, and for men between 19 and 21.”Footnote 45 Ahmadinejad went on to state that “we need to move towards simple marriage and support it. I believe a simple and dignified marriage has priority over employment and housing issues.”Footnote 46 The expression “simple marriage” was used by the head of government to mean a marriage celebrated by an inexpensive ceremony and a dowry of primarily symbolic value, for example fourteen gold coins in the name of the fourteen Shiite immaculates.Footnote 47

Ahmadinejad thus proposed launching an initiative to conduct propaganda for “simple” early marriage. To this end, the minister for the interior set up a foundation called the “National Foundation for Marriage” within the ministry’s department for women’s affairs.Footnote 48 This foundation was tasked with coordinating all state activities for the marriage of young people, supporting bodies whose activities consisted in facilitating marriage, and helping set up new structures to monitor these goals.

To assess the impact of this measure it is necessary to carry out a field survey, which is not possible under current conditions in Iran. Nevertheless, as mentioned earlier, it is legitimate to assume that this measure, at least at the beginning, when these financial incentives seemed significant, have encouraged young people from disadvantaged strata, particularly in rural sectors, to get married.

Direct redistribution of subsidies

The reform to the subsidy system introduced in December 2010, called “targeting subsidies,” may constitute an indirect incentive. It was a matter of removing energy subsidies (for petrol, diesel, kerosene, mains gas, and electricity) and offering these products at the international market price, while introducing compensatory measures to redistribute part of the revenue thus generated to the most disadvantaged households. Thus, as of December 2010, each household member, irrespective of age and gender, received 81,000 toman in compensation every two months (the equivalent of €54 in 2010).Footnote 49 By June 2011, 72 million Iranians (nearly 96percent of the total population) had signed up. By 2016, the figure had increased to a little over 77 million people (still nearly 96percent of the total population), with the subsidies now being monthly (45,000 toman, or €27).

In the absence of adequate data, it is not possible to analyze the correlation between this policy and the fertility trend. However, it appears clear that at the beginning of the 2010s, when the cost of living was not as high as in recent years, these subsidies seemed to constitute additional income, and for those who were unemployed they were a sort of unemployment benefit.Footnote 50 Hence, given that each Iranian citizen could receive this subsidy irrespective of age and gender, it may be considered an indirect incentive, particularly for the most disadvantaged, to have more children.

Coercive and aggressive measures

Halting the distribution of free contraceptives

In parallel to these incentives—and taking advantage of a speech by the supreme leader during a meeting with senior state policymakers in July 2012 in which he emphasized that “if the population control policy continues, the population will grow progressively older and the population will ultimately decline”Footnote 51—Ahmadinejad blocked the family planning budget for the purchase of contraceptives as of August 2012.Footnote 52 In 2013, following recommendations by the supreme leader, the family planning centers’ budget was drastically reduced. Consequently, these centers definitively halted the distribution of free contraceptives, and stopped offering vasectomies and tubal ligation as of 2013. As mentioned earlier, contraceptives were admittedly still on sale in pharmacies, but given the serious economic crisis and soaring inflation (which rose from 16percent in 2014 to 27 percent in 2018),Footnote 53 their price rose steadily, making them unaffordable for many people. Additionally, since this date, pro-government media (including newspapers, radio, television) together with clerics during Friday prayers have started a systematic offensive against contraceptives, alerting public opinion to the often very dangerous side effects for women’s health.

The suspension of free distribution of contraceptives affects in particular families from the disadvantaged and modest strata who until then could benefit from the various services of the family planning centers to control their fertility. Again, in the absence of appropriate data, we can merely assume that this aggressive measure has affected fertility and possibly caused unwanted births and resulted in a slight increase in the fertility of married couples.

Criminalization of vasectomy and tubal ligation

In July 2014, the Iranian parliament passed a law forbidding practices such as vasectomy for men and tubal ligation for women, laying down sanctions for any doctors infringing these provisions.Footnote 54 Additionally, it was henceforth forbidden to campaign in favor of contraceptive practices, and any person using state or public means to such an end was liable to a fine of between 2 and 5 million tomans, in accordance with article 19 of the Islamic criminal code.

While, according to the latest available data, in 2010 nearly a third of married women used tubal ligation—a frequency which we can assume has remained stable since—the criminalization of this practice is likely to have influenced fertility. In the absence of reliable figures it is impossible to confirm this hypothesis. However, it seems legitimate to formulate the hypothesis that, by depriving women of this radical contraceptive practice, the risk of unintended pregnancies has increased and, as a result, the number of births, also unwanted, tends to increase, since abortion is prohibited in Iran.

Employment priority given to married men with children

Among the fifty articles of a draft law called “Population and Transcendence of the Family,” parliament passed one which gives employment priority in both the public and private sector to married men with children, followed by married men without children, and lastly married women with children. In the absence of married applicants, it is possible to employ qualified unmarried individuals—men first, then women.Footnote 55 Given that the evolution of the main determinants of fertility in Iran is contributing to birth control, we assume that this discriminatory law targeting single people, especially women, has influenced the behavior of married couples and young singles.

Given the severity of the economic situation in Iran and the high rate of unemployment, young couples are likely to have changed their family plans and young men and women may have decided to marry in order to increase their chances of accessing stable employment. It is possible that couples in particular have reduced the interval between marriage and the first birth or between births if they had already a child. Of course, until now no data is available to prove this hypothesis. However, in the current state of knowledge of the social and economic situation of the country, it seems to be the most likely explanation of the slight increase in fertility between 2012 and 2016. Since then, the worsening economic conditions, mainly due to US sanctions, having significantly reduced the government’s ability to continue both its coercive and incentive measures, have led to a continued decline in marriages and, therefore, also in births and fertility.

The singular nature of the Islamic Republic’s new population policy

Unlike the first two population policies, the objective of the third one in place since May 2014 is not only to encourage population increase, on the pretext of the threat of an aging population due to birth control and the fall in fertility, but also to govern the population by recommending political measures to control it and to decide on its composition and distribution. As this was deemed a strategic plan for the Islamic Republic, the three powers—the legislative, the executive, and the judiciary—cannot modify it without the supreme leader’s agreement, and must additionally do all they can to carry it out.

The fourteen articles of this decree called “General Population Policies” are drawn up in equivocal terms which may give rise to different applications depending on the context. For example, the target of reaching a population of 150 million is not specifically stated, but the first article stipulates that it is necessary to “promote the dynamics, growth, and youthfulness of the population by an increase in fertility which should be above the replacement threshold,” without specifying the level of fertility targeted. According to certain policymakers, the figure is three children, while for others it is five to six children. Article 2, among others, insists on the need to remove obstacles to reducing age at marriage. Yet no practical indications are given. Several of the decree’s articles refer to the need to cover the costs associated with pregnancy and maternity, for infertility treatment for men and women, and for nutritional and health needs; to include lessons in public schooling about founding families and the merits of so doing; to develop a culture of respect for the elderly and create the requisite conditions for ensuring their health and their care by the family; and so on. While six articles seem to focus on demographic considerations, six others reveal the ideological tenor of the recommendations: promoting and institutionalizing the Islamic and Iranian way of life to counter undesirable aspects of western lifestyles; reinforcing the components of (Iranian, Islamic, and revolutionary) national identity; creating new settlement zones, particularly in the islands along the coasts of the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman; managing emigration and immigration in concert with general population policies; promoting consensus and social integration across the territory, in particular in the border zones and among Iranian expatriates; and encouraging Iranian expatriates to return and invest in the country and thereby benefit from their possibilities and capabilities.Footnote 56

Indeed, being well aware that the predominant family model in Iran is to marry late and have a small nuclear family, the Islamic Republic’s policymakers also know that the prospect of reaching a target population of 150 million Iranians in the near future is utopian. This, to my mind, is why the decree never explicitly mentions this target, while nevertheless hinting at the idea of peopling the entire territory by means other than raising the Iranian fertility rate.

The first means could be expatriate Iranians, estimated by the authorities at 1–2 million, as mentioned in article 12 of the decree. In this decree, the objective of the Islamic Republic is to encourage expatriates not only to return to their country but also to invest their capital. However, given that the majority of these expatriate Iranians oppose the Islamic regime, assuming they agree to return to Iran, they might instead end up causing political unrest. This is why it is unlikely that this policy will not be the priority of the regime.

While mention is made of managing immigration and emigration in compliance with general population policies (article 11)—without any practical indications on this matter—it may be supposed that the Islamic Republic could envisage including within the Iranian population the couple of million Afghans living in Iran as refugees and/or as “undocumented” migrants.Footnote 57 Especially as since 2014 Afghans enlisted by the Revolutionary Guards (Pasdaran) as militiamen (called Fatemiyoun) to fight alongside the Syrian army have received Iranian nationality for themselves and their families. It is likely that the government refers to these recently naturalized Afghans as Iranian expatriates. In this regard, let us remember that the naturalization procedure for Afghans and other combatants is paradoxically managed by the Foundation of Martyrs and Veterans Affairs, which was finally legalized by the parliament in the framework of the Sixth Development Plan on 16 January 2017. According to article 102 of the law, the granting of citizenship and residence to persons referred to in this article is in accordance with the rules of the law prepared by the state major general of the armed forces in cooperation with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of the Interior and approved by the Supreme Council of National Security within three months.Footnote 58 As confirmed by Hojatol eslam Sayed Mohammad-Ali Shahidi Mahalati, the Director of Foundation of Martyrs and Veterans Affairs, speaking of the naturalization of Afghans, in an interview with the daily newspaper Javan, he said that the Supreme Leader shared with him the following: “If tomorrow the defenders of the sanctuary head to Afghanistan and the Taliban learn that they went to Syria to fight, they will slaughter them all. It is our duty to protect them. For this reason it is imperative to grant them the Iranian nationality and that the Foundation takes care of them.”Footnote 59

This mass policy of taking in migrants and integrating them may also concern Shiite militia recruited by the Pâsdârân in Afghanistan and in Pakistan (called Zeynabiyoun) and fighting alongside the Revolutionary Guards in Syria. This practice seems fairly close to the spirit of the 2014 decree, and suggests that were immigrant populations included in the Iranian population, the prime beneficiaries would be Shiites. Furthermore, these recommendations are for border zones, peripheral regions peopled mainly by Sunnis. Insofar as these zones—particularly those bordering Afghanistan and Pakistan to the east and Iraq and Turkey to the west—seem porous, with intense, regular two-way circulation of populations from the same ethnic, linguistic, and religious groups, the state appears determined to curb these flows. In light of this, article 13 of the decree calling to “reinforce the components of (Iranian, Islamic, and revolutionary) national identity and promote consensus and social integration across the territory, in particular in the border zones and among Iranian expatriates” takes on its full meaning. The objective is above all to provide Iran with a large population, but additionally one that adheres to the values of the Islamic Republic defined as one of the components of national identity.

It is most likely that the Islamic Republic will follow this path, since coercive and incentive policies do not seem to have had a lasting or significant effect on the fertility trend. The economic crisis, worsened by the hardening of American sanctions, asphyxiating the country’s economy, prevents the Islamic regime getting close to its objective. For all these reasons, the new population policy of the Islamic Republic may be defined as populationist.

Conclusion

Changes in the main determinants of fertility tend towards controlling fertility; therefore, to my mind, the uptick in fertility is essentially attributable to couples who are already married. Since Iran’s leaders are well aware that the circumstances are not propitious and the socio-cultural context is not conducive to the idea of large families, they have repeatedly taken new steps to reverse the trend and obtain rapid, and tangible results. For example, in April 2019 the Iranian parliament passed articles 27 to 30 of the “Population and Transcendence Family” draft law, which were intended as incentives. Under these laws, the government is to grant parents additional allowances and financial assistance for each birth after their third child, and to introduce the mechanisms needed by young infertile couples to benefit from all pro-fertility treatments up to two years after marrying.Footnote 60 The passing of these laws at the time when the reimposition of US sanctions (in November 2018) meant the Iranian state was encountering insurmountable obstacles to sell oil, and thus found itself in serious financial straits, seems far from coherent.Footnote 61

The other—latent—objective of the new policy is to boost population growth to reach 150 million inhabitants. The idea, as formulated in the 2014 decree, of peopling border zones with Iranian expatriates, who may be recently naturalized Shiite Afghan and Pakistani militiamen, reveals the ambitious political and geostrategic objective—far removed from any purely demographic reasons—behind the country’s new population policy. With an Iran of 150 million inhabitants, the Islamic Republic hopes to acquire a “demographic weapon” to wield influence in the region. It would indeed be a crucial weapon for a regime engaged in structural disputes with its immediate neighbors and with the West, and one cannot fail to note a coherence between this populationist direction and Iran’s ambitions for regional hegemony.

Will it fulfill these objectives? It is still too early to say. Especially now that the COVID-19 pandemic has completely changed the situation. Thus we need to await more recent observations to assess the impact and capacity of the Islamic Republic’s new population policy to achieve its ambitious objective.